95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Nutr. , 05 March 2024

Sec. Food Chemistry

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1338482

This article is part of the Research Topic Nutritional Components in Woody Oil Crops View all 5 articles

Ismail Mahdi1

Ismail Mahdi1 Paola Imbimbo2

Paola Imbimbo2 Hassan Annaz1

Hassan Annaz1 Widad Ben Bakrim1

Widad Ben Bakrim1 Nihad Sahri1,3

Nihad Sahri1,3 Asmae Alaoui3

Asmae Alaoui3 Daria Maria Monti2

Daria Maria Monti2 Mansour Sobeh1*

Mansour Sobeh1*Petroselinum sativum, known as parsley, is a fragrant herb that possesses a rich heritage of utilization in traditional medicinal practices. In this study, we annotated the phytocontents of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of P. sativum and investigated their antioxidant, cytoprotective, antiaging, wound healing, and antibacterial activities. LC–MS/MS analysis of both extracts revealed the presence of 47 compounds belonging to diverse groups including organic acids, phenolic acids, and flavonoids. By MTT assay, the extracts were fully biocompatible on immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) while they inhibited intracellular ROS formation (DCFDA assay) and prevented GSH depletion (DTNB assay) upon UVA exposure. In addition, the extracts were potent in inhibiting the in vitro activities of skin-related enzymes mainly elastase, tyrosinase, collagenase and hyaluronidase. Using the scratch assay, P. sativum aqueous extract significantly enhanced wound closure when compared to untreated HaCaT cells. Moreover, both extracts inhibited Pseudomonas aeruginosa’s growth, reduced biofilm formation, and impaired the swimming and swarming motilities. Also, the aqueous extract was able to inhibit the production of bacterial pigments on plates. These findings strongly suggest the usefulness of P. sativum as a source of phytochemicals suitable for dermo-cosmeceutical applications.

Aging is an inevitable process featured by impaired functions at the molecular, cellular, tissue and organ scales. It is the major risk factor for the development and progression of several diseases, especially in elderly subjects. Many diseases have been related to aging susceptibility such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer (1).

Over the past decades, many assumptions have been proposed to unveil aging process mechanisms. For instance, in vitro dysregulation of the apoptotic pathway was proven to be involved in some aging processes. Additionally, epigenomic changes greatly affect cellular function and profoundly contribute to aging progression (1). Also, scientific evidence has indicated the free radical reactions that occur within the cells and tissues, representing the major contributor to the aging process (2, 3). Indeed, understanding the underpinning mechanisms is critical for developing effective strategies against age-related diseases.

The cosmetic market is highly growing. In 2019, it generated estimated revenues of 380.2 billion USD and is expected to reach up to 463.5 billion USD by 2027 with a relative annual growth going from 5.3 to 7% between 2021 and 2027 (4). Consequently, bioactive compounds extracted from natural sources as cosmetic ingredients are gaining attractiveness. For instance, phytochemicals with antioxidant activities, modulatory effects on molecular cell receptors and/or gene expression, and inhibitory effects on enzymatic activity have demonstrated their usefulness in counteracting cell aging (5).

In this context, many functional foods and dietary compounds were found to have anti-aging properties and health beneficial effects via regulation of numerous pathways, such as nutrition sensing and stress signaling, modulation of cellular metabolism, stress resistance, energy homeostasis, genome maintenance, and mitochondrial biogenesis. Notwithstanding this evidence, many of these natural compounds are yet to be explored for their potential in preventing or delaying aging related disorders (6).

Parsley (Petroselinum sativum) is a biennial aromatic plant from the Apiaceae family. It contains flavonoids and other phenolic compounds such as furanocoumarins, carotenoids, polyacetylenes, and its leaves are a great source of minerals as calcium, thiamin, riboflavin, potassium and iron and vitamins such as A, C, and niacin (7). It harbors essential oil in all parts, with phenylpropane and terpene compounds as major constituents. P. sativum also contains proteins (2–22%), fats (4%), sugars, among others (8). Compounds such myristicin, apiol, 1-allyl-2,3,4,5-tetramethoxybenzene, β-phellandrene, 1,3,8-p-menthatriene, β-pinene, terpinolene, apiin, oxypeucedanin and falcarinol are mostly isolated from P. sativum (9). However, this composition depends on several factors, such as plant tissue, variety, climate, and sampling method (10).

For hundreds of years, Mediterranean population used P. sativum as a medicinal plant. Traditionally, it is used to manage arterial hypertension, diabetes, renal diseases, and cardiovascular diseases in different countries (11–13). Indeed, recent in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that P. sativum elicits several biological and pharmacological activities such as diuretic, anti-urolithiasis, hypouricemic, hypolipidemic, hypotensive, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiplatelet effects (9). It also exhibits antimicrobial, laxative, anti-anemic, anti-otitis, menorrhagic, antihyperlipidemic, cytoprotective, antihepatotoxic, carminative, estrogenic and hyperuricemia activities (11).

Although P. sativum has been explored for a wide range of biological activities, its cosmeceutical potential has not been sufficiently studied so far. Thereby, herein, we annotated the chemical composition of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of P. sativum using LC–MS/MS and investigated their anti-aging potential, wound healing ability, as well as antioxidant activity using in vitro, enzymatic, and cell-based approaches. Moreover, the antibacterial, anti-biofilm and inhibitory effect on microbial mobilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa were assessed. The choice of studying this bacterium resides in its multi-resistance to conventional antibiotics and its ability to cause skin infection (14). The overall aim of this study is to provide valuable information on the potential of P. sativum as a source of dermo-cosmeceutical agents, addressing critical aspects of skin care and dermatological health mainly anti-aging properties, protection against induced skin-oxidative stress, wound healing capabilities, and anti-infectious attributes.

Fresh P. sativum plants were obtained from a local market in Ben Guerir, Morocco, in December 2021. The aerial parts of the plants were shade-dried, milled into a fine powder, and then subjected to ultrasound-assisted extraction using water and/or ethanol (15 g × 400 mL) for 20 min, employing the following conditions: 20 Hz, 5°C, 30% sound wave amplification, and a 10-s pulse duration. Next, the extracts were filtered through glass-wool and the filtrates were centrifuged for 10 min at 6000xg to remove impurities. Next, the supernatants were evaporated using a rotavapor (BUCHI R-300, Flawil, Switzerland), frozen at −80°C and lyophilized (Labconco™, Strasbourg, France) to obtain completely dried fine powders. Extraction yields of the aqueous and ethanolic extract attained 1.71 g (11.4%) and 1.2 g (8%), respectively.

Total polyphenol (TPC) and flavonoids contents (TFC) were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu and Aluminum chloride methods, respectively, as previously described (15). The LC–MS/MS analysis was conducted using a SHIMADZU LC MS 8050 coupled with a triple quadrupole spectrometer equipped with an ESI source (16). A C18 reversed-phase column (Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a gradient of water and acetonitrile (ACN) with 0.1% formic acid was employed for separation over 60 min. The autosampler (SIL-40C xs) facilitated automatic injection of 20 μL of the sample. Shimadzu’s LC solution software controlled the entire process, and the MS operated in the negative ion mode with an m/z range of 100 to 1,500. Compound identification relied on molecular weights, mass fragmentation patterns, and elution order compared to literature data from the plant and genus, as well as in-house standards.

The antioxidant activity of the extracts was estimated using the colorimetric methods, i.e., DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) assays (17, 18). In the DPPH assay, 100 μL of the extract and 100 μL of the DPPH solution (0.2 mM) were combined in individual wells of a 96-well microplate and placed in darkness at room temperature for 30 min. The optical density (OD) was then measured at 517 nm. Quercetin served as the standard compound (ranging from 1 to 1,000 μg/mL). Each sample was tested in triplicate. The scavenging capacity was calculated as follows:

The FRAP assay was also carried out in a 96-well plate. Briefly, 180 μL of the FRAP solution was mixed with 30 μL of the samples, shaken well, and kept in the dark at 37°C for 20 min. The distilled water served as the blank control and quercetin as the standard antioxidant. Ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) at the concentrations (500–7.81 μg/mL) was selected to draw a standard curve. All experiments were performed in triplicate. An intense navy-blue color was noticed upon reduction, which was monitored at OD595 nm using a microplate reader. The results were expressed as mM FeSO4/g sample.

Anti-elastase, anti-tyrosinase, anti-collagenase and anti-hyaluronidase assays were performed as previously described (15). In brief, kojic acid and quercetin were used as positive controls, while solutions without samples were used as negative controls. Each measurement was performed in triplicate and the percentage of enzyme inhibition (%) was calculated according to the following formula:

Asample: OD of the enzymatic activity from the extracts or positive control.

Acontrol: OD of the enzymatic activity from the negative control.

Immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT, Innoprot, Spain) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (EuroClone), supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (HyClone), 2 mM L-glutamine and antibiotics (EuroClone) in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. HaCaT cells were cultured following the protocol described by Ferraro et al. (19).

Cells were seeded at a cell density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2. After 24 h, increasing concentrations of each extract (from 0.1 to 100 μg/mL) were added to the cells for 48 h (20). Then, cell viability was evaluated by the MTT assay and results were expressed as cell viability rate (%) as described by Ferraro et al. (19).

Cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/cm2. After 24 h, cells were incubated for 2 h in the presence of 50 μg/mL of each extract and then exposed to UVA light (365 nm) for 10 min (100 J/cm2). A commercial UVA lamp was used as source of oxidative stress as described by Sobeh et al. (21).

The antioxidant effect of both aqueous and ethanolic extract was evaluated by measuring the intracellular ROS levels using DCFDA assay as described by Del Giudice et al. (22). Additionally, DTNB assay was used to analyze intracellular glutathione levels by following the method described by Petruk et al. (20). Commercial GSH was used as a standard to obtain a calibration curve.

The wound healing potential was determined utilizing a scratch assay. HaCaT cells were seeded at a cell density of 3 × 104 cells/well and left for 24 h to reach 95% confluency. The cells were then washed using PBS, scratched manually using a 200 μL pipet tip, and incubated with 50 μg/mL of each extract. The healing progress of the scratch was observed at 0 h and 24 h via capturing images using an optical microscopy (Zeiss LSM 710, Zeiss, Germany) at 10x magnification. The wound’s width was assessed using Zen Lite 2.3 software. The findings are expressed as a measure of area reduction (fold change) compared to untreated cells.

The antibacterial activity of P. sativum extracts was evaluated by the broth microdilution assay using a sterile 96-well microplate (23–27). A stock solution of each plant sample was suspended in Mueller Hinton (MH) broth, filtered through 0.22 μm sterile syringe filters, and two-fold serially diluted (100, 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.25 mg/mL). Subsequently, the diluted samples were dispensed into the wells of a microplate in triplicate (200 μL per well). Next, 2 μL of an 18-h-old bacterial culture of P. aeruginosa adjusted to OD600nm = 1 were inoculated into each well and incubated at 37°C under 150 rpm shaking for 24 h. The lowest concentration that inhibited the visible microbial growth was considered as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The inhibition percentage of bacterial viability was calculated based on the OD value of the extracts treated media group against the extract free media.

The antibiofilm potential of the extracts was evaluated using a colorimetric assay (25–27). Firstly, the plant extracts with concentration of 12.5 mg/mL (1/8 maximum concentration) and 25 mg/mL (1/4 maximum concentration) were prepared in MH and then filtered using 0.22 μm sterile syringe filters. Filtered extracts were inoculated and incubated as described above. Media without bacterial cells addition were established as negative controls. Following 24 h incubation, culture media were removed, and wells were gently washed with PSB to remove planktonic bacterial cells. Then, the biofilm was stained with a crystal violet (CV) solution at 1% and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Afterwards, a vigorous washing with sterile distilled water was performed to remove the excess of CV. The produced biofilm was dissolved by adding 95% ethanol to each well and the OD was read at 595 nm using a multimode plate reader (Costar, 96). The biofilm attachment was observed by using a microscope before and after solubilization by ethanol at 10x magnification.

P. sativum extracts were tested for their effect on the swimming and swarming motilities of P. aeruginosa on agar plates. The swimming (1% tryptone, 0.5% sodium chloride, and 0.3% agar) and swarming (semisolid LB medium, 0.6%) media (28) were aseptically supplemented with 12.5 mg/mL and 25 mg/mL of each extract. Then, 5 μL of a fresh overnight culture of P. aeruginosa (OD600nm = 1) was deposited at the center of each plate and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The swimming and swarming zones diameters were measured in cm (15, 26). Fresh media were used as negative controls.

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software, involving one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc examination using Tukey’s test. Significance levels were considered at p < 0.05. Values are the mean of three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate, and the outcomes are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

The LC–MS/MS analysis of P. sativum aqueous and ethanolic extracts revealed a total of 46 phytocompounds with a variation in their content (Table 1; Figure 1). The aqueous extract contains 41 compounds, whereas 39 compounds were detected in the ethanolic extract. Notably, the aqueous extract contained the largest number and highest amounts of annotated compounds. These secondary metabolites belong to diverse groups, namely organic and phenolic acids, and flavonoids. Five signals, representing organic acids, were detected with high amount in both extracts, including oxoadipic, citric, maleic, malic, and succinic acids. In addition, the most abundant phenolic acid was coumaric acid, detected in its aglycon, glycosidic and acetylated conjugations.

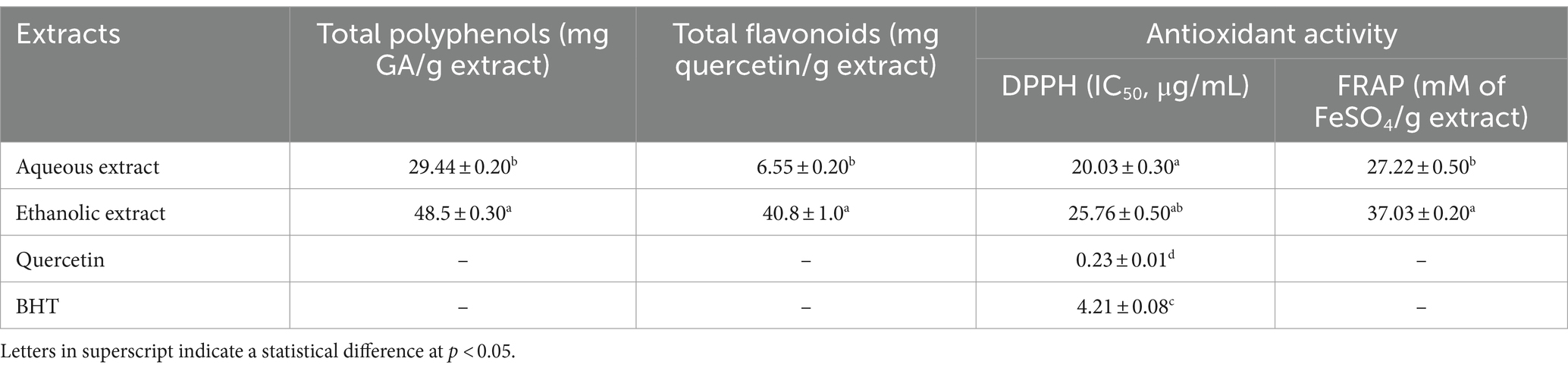

The analysis of polyphenol and flavonoid content revealed significant differences between the aqueous and ethanolic extracts. The ethanolic extract contained notably higher levels of both polyphenols (48.5 mg GA/g extract) and flavonoids (40.8 mg Quercetin/g extract) compared to the aqueous extract, which contained 29.44 mg GA/g extract of polyphenols and 6.55 mg Quercetin/g extract of flavonoids (Table 2). These findings suggest that the ethanol extraction method is more effective in extracting these bioactive compounds from the source material.

Table 2. Total polyphenol and flavonoids contents and in vitro antioxidant activities of P. sativum extracts.

In addition, the aqueous extract showed better DPPH scavenging activity with an IC50 of 20.03 μg/mL, while the ethanolic extract had a higher IC50 (25.76 μg/mL). However, in the FRAP assay, the ethanolic extract exhibited stronger ferric-reducing antioxidant power with a value of 37.03 mM of FeSO4/g extract compared to 27.22 mM of FeSO4/g extract for the aqueous extract. Reference compounds, quercetin and BHT, were significantly more active in DPPH scavenging activity compared to both extracts (Table 2).

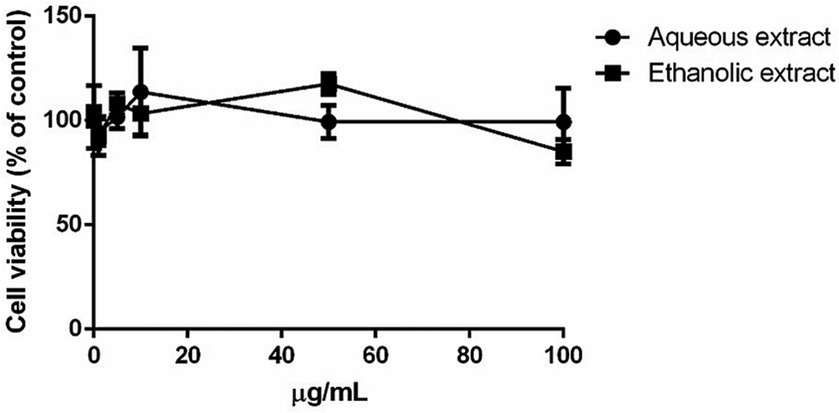

The possible toxic effect of P. sativum extracts was evaluated on eukaryotic cells. HaCaT cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of each extract (0.1–100 μg/mL) for 48 h and then cell viability was evaluated utilizing MTT assay. Interestingly, no significant toxic effect on cell viability was observed in the presence of either extract. In particular, a complete biocompatibility was observed independently from the concentration tested (up to 100 μg/mL), suggesting that both extracts could be used safely on HaCaT cells (Figure 2). Starting from this encouraging result, the concentration of 50 μg/mL was used to study the protective activity of the extracts against UVA-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 2. Dose–response curve of immortalized human keratinocyte (HaCaT) after 48 h incubation with increasing concentrations of P. sativum aqueous (black circles) and ethanolic (black squares) extract (0.1–100 μg/mL). Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay, and the percentage of surviving cells when exposed to test extracts, relative to control cells (those without extracts), was used to express cell survival. The data is presented as the mean values with standard deviation (S.D.), and three separate measurements were conducted.

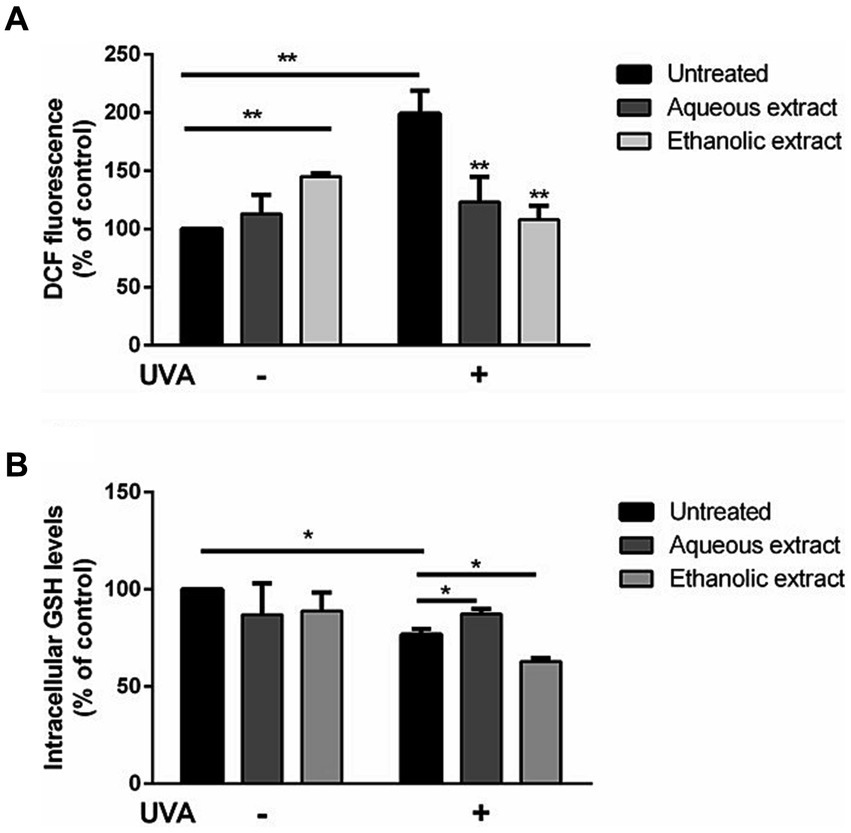

As shown in Figure 3A, ROS production was significantly increased after exposure to UVA irradiation (black bars, p < 0.01). Incubation of cells with the ethanolic extract (light grey bars) induced a significant increase in ROS production (p < 0.01) in the absence of oxidative stress. Interestingly, a significant inhibition of the intracellular ROS levels (p < 0.01) was observed when cells were pre-incubated with each extract.

Figure 3. Antioxidant effect of P. sativum extracts on HaCaT cells stressed with UVA. Cells were pretreated with presence of 50 μg/mL of aqueous extract (dark grey bars) and ethanolic extract (light grey bars) for 2 h before UVA irradiation (100 J/cm2). Cells were cultured with extracts either without (−) or with (+) exposure to UVA. Black bars refer to untreated cells. (A) Determination of intracellular ROS levels utilizing DCFDA assay. (B) GSH levels measurement utilizing DTNB assay. The data are presented as percentages relative to untreated cells. The results represent the mean values with standard deviation (S.D.) from three independent experiments. * denotes significance at p < 0.05, while ** indicates significance at p < 0.01.

As shown in Figure 3B, a slight but significant decrease in intracellular GSH levels was observed upon UVA irradiation (black bars). Interestingly, when cells pretreated with the aqueous extract before UVA exposure, GSH depletion was inhibited (up to 16.8% increase in GSH level), whereas a different behavior was observed when cells were pretreated with the ethanolic extract, as a significant depletion in GSH levels (up to 15% decrease in GSH level) were observed (p < 0.05).

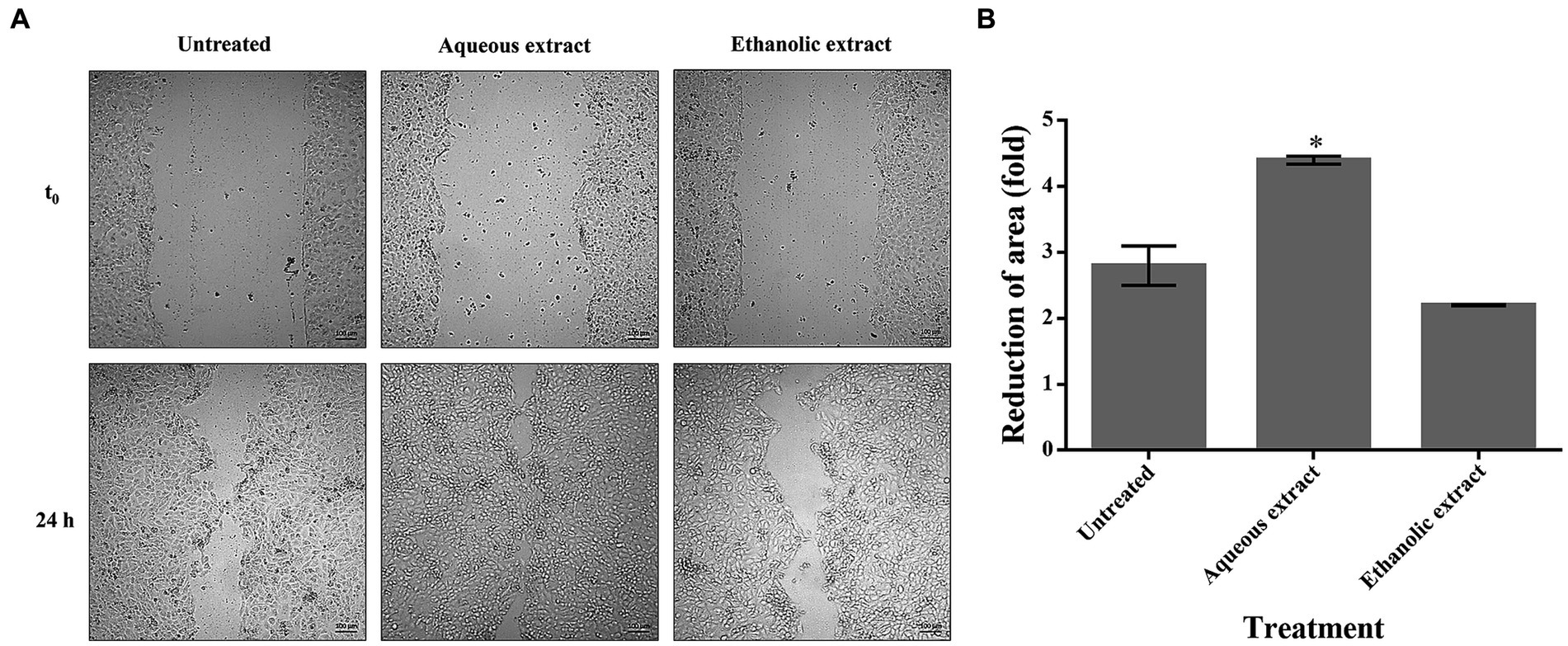

To verify if P. sativum extracts could promote cell migration in wound repairing, a scratch assay was conducted on HaCaT cells. In untreated cells, a spontaneous re-epithelialization was observed. Interestingly, the aqueous extract significantly enhanced the wound closure after 24 h of treatment (4.40-fold reduction) when compared to untreated cells (2.80-fold reduction). On the contrary, the ethanolic extract showed no positive effect, as wound closure was similar to untreated cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The effect of P. sativum extracts on wound healing. (A) Confluent HaCaT cells were scratched and treated with 50 μg/mL of either aqueous or ethanolic extract. At time 0 and after 24 h, optical microscopy images were acquired at 10x magnification and at different locations. (B) Reduction of area (fold) of wound closure upon 24 h incubation with aqueous or ethanolic extracts. The data are expressed as fold change relative to the control, which refers to untreated cells. The values represent the mean with standard deviation (S.D.) from three independent experiments. (*) signifies statistical significance at p < 0.05.

The enzymatic activities of both extracts were assessed against four the enzymes involved in cell aging namely elastase, tyrosinase, collagenase and hyaluronidase. The ethanolic extract (IC50 = 10.75 – 20.12 μg/mL) was more active in inhibiting the enzymatic activities than the aqueous extract (IC50 = 2.03 – 10.18 μg/mL). However, both extracts showed a higher inhibition of elastase and tyrosinase, compared to collagenase and hyaluronidase. Notably, the ethanolic extract exhibited pronounced inhibitory effect against the four enzymes, with respect to the reference compounds, i.e., Kojic acid and quercetin (IC50 = 9.00 – 24.83 μg/mL) (Table 3).

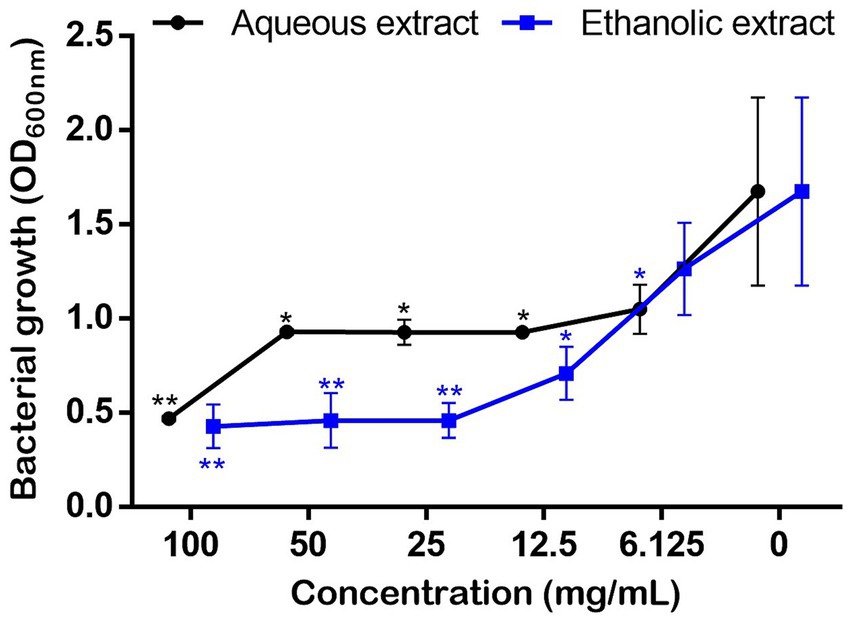

Bacterial growth monitoring showed that the P. sativum extracts significantly and dose dependently inhibited P. aeruginosa growth starting from 6.125 mg/mL of the aqueous extract, and 12.5 mg/mL using the ethanolic extract. Nevertheless, even both extracts at 100 mg/mL decreased bacterial growth by 72.45 and 74.85%, respectively, total inhibition of bacterial growth did not occur (Figure 5). This means that the MIC is higher than 100 mg/mL.

Figure 5. Effect of P. sativum extracts on the growth of P. aeruginosa using concentration rage 0–100 mg/mL in MH broth. Asterisks (*) indicate the statistical difference compared to the control media (p < 0.05).

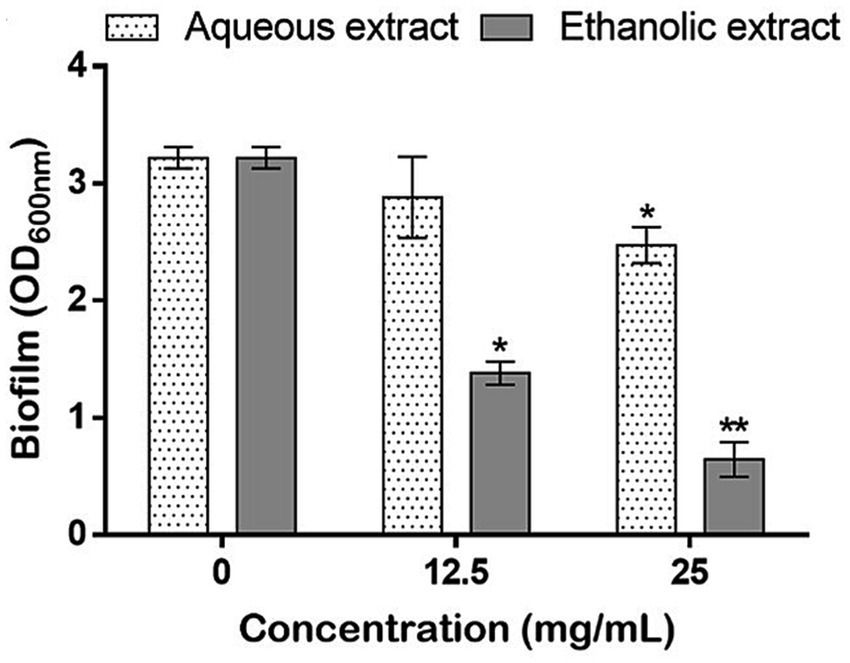

To investigate the antibiofilm potential, the sub-doses of 12.5 and 25 mg/mL referring to 1/8 and 1/4 of the highest tested concentration (100 mg/mL), respectively, were utilized to estimate the amount of biofilm produced by P. aeruginosa. For both extracts, results showed a dose-dependent inhibition of the biofilm production, however the aqueous extract showed a slight, but significant, inhibition (23.05%) only at 25 mg/mL. On the other hand, the ethanol extract allowed a considerably inhibition in the biofilm formation at both tested concentrations (57% and 80%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effects of P. sativum extracts on the biofilm production by P. aeruginosa using the sub-doses of 12.5, and 25 mg/mL. Asterisks (*) indicate the statistical difference compared to the control media (untreated bacteria, 0 mg/mL) at p < 0.05.

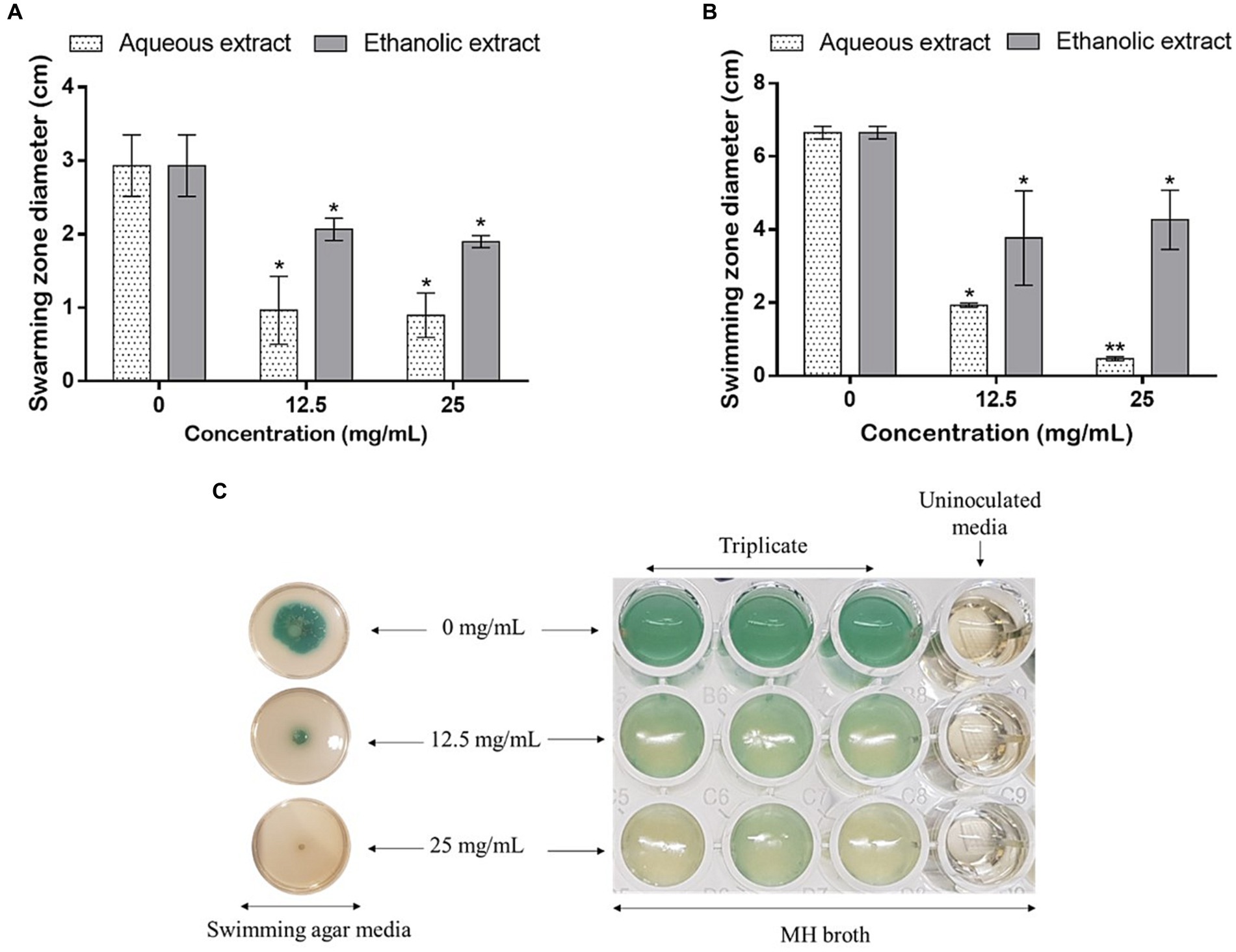

Using the same concentrations, the effect of the extracts was tested on the mobility and bacterial pigment production on plates. As shown in Figure 7, the swarming (Figure 7A) and swimming (Figures 7B,C) mobilities were inhibited, as the concentrations of the extracts increased. Noteworthy, the water extract was more potent in hindering P. aeruginosa mobilities comparatively to the ethanolic one. Finally, the aqueous extract, at 25 mg/mL, completely inhibited the production of the bacterial pigments (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Effect of P. sativum extracts on (A) swarming and (B,C) swimming mobility of P. aeruginosa using the sub-doses 12.5 and 25 mg/mL. Asterisks (*) indicate the statistical difference compared to the control media (0 mg/mL) (p < 0.05).

P. sativum is widely used as culinary herb, but it also boasts an array of potential health benefits that have been acknowledged over centuries. In this study, LC–MS/MS analysis of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of P. sativum unveiled 47 secondary metabolites belonging to various classes of organic acids (e.g., oxoadipic acid, citric acid, maleic acid, malic acid, and succinic acid), phenolic acids (e.g., coumaric acid) and flavonoids (e.g., apigenin) (27, 29, 30). Similar findings were recently reported by Mallmann et al. (31) who identified 19 phenolic compounds in the methanolic extract (80%) of fresh P. sativum plants. The study showed that P. sativum is also rich in flavones, especially apigenin and its derivatives (31). Comparatively, the extracts obtained in the present study are rich in other phenolic acids, such as hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid and shikimic acid. Moreover, other aglycons were characterized along with their glycosidic and acetylated conjugations, such as isorhamnetin, diosmetin, quercetin, and kaempferol. In contrast, different types of polyphenols, mainly oleuropein, arbutin, myricetin, and naringin were recently revealed in the P. sativum hydro-ethanolic extract (32). The differences in the phytochemical composition are due to many factors, such as the geographical location, climate, soil type, growth stage, cultivation practices, and processing methods. These factors collectively shape the presence and concentration of the bioactive compounds, thus impacting therapeutic properties of the plant and its potential applications (10).

To the best of our knowledge, the cosmeceutical potential of P. sativum has not been sufficiently investigated. Thus, here we explored the beneficial effects of P. sativum aqueous and ethanolic extracts on skin aging process, wound healing, oxidative stress, and skin bacterial infections. Notably, the assessment of the extracts’ effect on HaCaT viability demonstrated a full biocompatibility for dermatological applications up to 100 μg/mL. More importantly, both extracts showed a strong in vitro antioxidant activity by DPPH and FRAP methods. These results were corroborated by antioxidant activity tested on a cell-based model, to evaluate the effects of P. sativum extracts on UVA stressed HaCaT cells where cell treatment with both extracts prior to UVA exposure resulted in a significant inhibition in intracellular ROS levels. The antioxidant activity of the aqueous extract was further confirmed by the inhibition of GSH depletion upon UVA radiation. Indeed, GSH is well known to be involved in the antioxidant defense system of the cells. However, a different behavior was observed for the ethanolic extract, as no protective effect was observed when cells were treated with the ethanolic extract and then irradiated by UVA radiations. Increased capacity of the aqueous P. sativum extract to prevent ROS and GSH depletion in UVA-irradiated HaCaT cells is probably due to the free radical scavenger activity of the plant phytochemicals (20). For instance, many preclinical investigations have provided evidence that apigenin, present in both extracts as a major compound, elicits positive impacts against UV-induced skin, dermatitis, vitiligo, wounds, skin aging, and skin cancer. This flavonoid primarily operates by impeding inflammation through the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and internal inflammatory agents, alongside its antioxidative qualities that enhance the body’s natural defense mechanisms against oxidative stress (33).

Furthermore, P. sativum extracts were assessed for their capacity to inhibit skin aging-related enzymes. Skin aging is a complex process influenced by various factors, including enzymes like elastase, collagenase, hyaluronidase, and tyrosinase. Elastase and collagenase contribute to the breakdown of elastin and collagen fibers, crucial components necessary to maintain skin firmness and elasticity. Hyaluronidase degrades hyaluronic acid, a key molecule responsible for skin hydration and volume. Tyrosinase plays a role in melanin production, influencing pigmentation changes and age spots. The overactivity of these enzymes, coupled with natural reduction of repair mechanisms, results in an acceleration of skin aging by diminishing structural integrity, moisture retention, and even skin tone (34). Here, we showed that both extracts were potent for inhibiting in vitro enzymes’ activities to different extents. Interestingly, the ethanolic extract exhibited pronounced inhibitory effect (IC50 = 2.03–12.54 μg/mL) against the four enzymes comparatively the reference compounds, namely Kojic acid and quercetin (IC50 = 9.00–24.83 μg/mL). This could be explained by the synergistic action of the plant’s compounds to effectively imped the functioning of skin aging enzymes. Indeed, many of the identified phytoconstituents such as kaempferol, isorhamnetin, quercetin, and their analogous compounds have been previously shown to combat skin aging by exhibiting inhibitory effects against the aforementioned enzymes (34–37). The inhibitory impact of P. sativum extracts on skin enzymes is likely the result of multiple mechanisms. For instance, it has been shown that the essential zinc ion situated within the collagenase’s active site is pivotal for its operation, facilitating interaction with the inhibitor (38). Furthermore, the hydroxyl groups within polyphenols can engage with collagenase’s backbone or other functional side groups. Additionally, the hydrophobic interaction between the benzene ring in the polyphenolic compound’s structure and collagenase can induce conformational alterations, rendering the enzyme nonfunctional (39). Elsewhere, it was demonstrated that the application of P. sativum extract (50 μg/mL) to Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDF) induced a significant decrease (up to 37.0%) in the protein expression levels of p-ERK and p-JNK, both known to be related to MMP1 gene expression by UVB exposure. These findings indicate that P. sativum extract potentially enhances wrinkle improvement by curbing the expression of the MMP1 gene, responsible for collagen breakdown. This effect is achieved through the hindrance of UVB-induced JNK phosphorylation (40).

Besides, a clinical trial provided evidence that the topical application of P. sativum resulted in a substantial reduction in the severity of epidermal melasma with comparable inhibitory effect to that of hydroquinone (41). Additionally, P. sativum leaf extract powder prepared at 4% was also reported to be effective in in vivo controlling of sebum. This effect was proposed to be attributed to the plant’s high vitamins content (C, A, B, E, K, and β-carotene) and minerals (magnesium, iron, phosphorus, manganese, sodium, potassium, sulfur, and calcium) (42, 43).

In this study, the effect of P. sativum extracts on HaCaT cells migration (in vitro) using the scratch assay was monitored and the aqueous extract significantly enhanced the wound closure (4.40-fold reduction), while no significant effect was observed with the ethanolic extract. Notably, this is the first study to demonstrate the in vitro wound healing effect of P. sativum. However, a recent study demonstrated that both the hydro-ethanolic and polyphenolic extracts of P. sativum resulted in substantial wound contraction in rats. After 25 days post-treatment period, the hydro-ethanolic extract exhibited the most pronounced healing effect, achieving up to 97% (32). This was attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds that facilitate repairing lesions and expediting cellular regeneration in impaired tissues. In fact, many medicinal plants (e.g., Curcuma longa, Centella asiatica, and Paeonia suffruticosa), along with their phytochemicals, are effectiveness in promoting wound healing. For instance, apigenin has been reported for its role in enhancing the wound healing process (44, 45). Furthermore, it has been reported that malic acid-enriched fractions from Sempervivum tectorum L. leaves promote cell proliferation and migration (46, 47). Therefore, it is plausible that the malic acid present in the P. sativum extracts may contribute to the wound healing process.

In addition to the skin aging and wound healing experiments, the antibacterial effects of P. sativum extracts against P. aeruginosa were investigated. The bacterium is an opportunistic pathogen that often displays multi-resistance to conventional antibiotics and is commonly associated to wound infections. In fact, when pathogens infiltrate a wound, they trigger an inflammatory response that can disrupt the orderly sequence of tissue repair. This leads to increased inflammation, delayed cell migration, impaired collagen synthesis, and compromised blood supply, all of which collectively hinder wound closure and tissue regeneration. Additionally, the presence of an infection can prolong the inflammatory phase, preventing the transition to subsequent healing stages (48, 49). Here, P. sativum extracts significantly and dose dependently inhibited P. aeruginosa growth. Precisely, the aqueous and ethanolic extracts at 100 mg/mL decreased bacterial growth by 72 and 75%, respectively. In addition, as P. aeruginosa can create robust biofilms, which sustain chronic infections, disrupt wound healing, and escalate the emergence of antibiotic resistance (50), the anti-biofilm capacity of the extracts was assessed and results revealed that the aqueous extract at 25 mg/mL significantly inhibited the biofilm up to 23% as well as the ethanol extract at 12.5 and 25 mg/mL which significantly decreased the biofilm by 57 and 80%, respectively. These results suggest that P. sativum phytocomponents hold potential for effectively contrasting P. aeruginosa’s biofilm formation during infections and thus impeding the adherence of bacterial communities to biological surfaces, in this case, the site of infection. In addition to biofilms, bacterial mobility assumes a crucial role in dictating the course of infection development. Bacteria employ various mechanisms such as flagella-driven twitching, swimming, or swarming to navigate the wound environment. These mobilities allow bacteria to colonize different wound surfaces and penetrate tissues (51, 52). The intricate interplay between bacterial mobility and the wound environment significantly impacts the severity, persistence, and treatment responsiveness of wound infections (53). Therefore, the effect of the extracts was assessed on the swarming and swimming mobilities of the bacterium on plates. Noteworthy, the aqueous extract was more potent in hindering P. aeruginosa mobilities comparatively to the ethanolic extract. At 25 mg/mL of the aqueous extract, the production of the bacterial pigment, pyocyanin, was completely inhibited. It is well established that P. aeruginosa only produces pyocyanin, therefore this is a diagnostic property of this bacterium. Pyocyanin, a redox-active phenazine compound, is a blue secondary metabolite found in sputum from P. aeruginosa infected tissues (54). This study demonstrated that P. sativum phytochemicals could target bacterial genes involved in biofilm formation and virulence factors production. Quercetin, a prominent constituent identified in the tested extracts, has previously demonstrated its efficacy in decreasing the expression levels of various quorum sensing genes namely lasR, lasI, rhlI, and rhlR exhibiting reductions of 68, 34, 57, and 50%, respectively (55). In the light of these findings, the potential of P. sativum phytoconstituents to counteract P. aeruginosa infections through its anti-quorum sensing effects holds promise through reducing bacterial growth rate, hindering biofilm formation and toxin production, and impeding bacterial colonization and infection within wound tissues.

Herein, P. sativum has been shown to be endowed with a wide range of cosmeceutical and dermatological properties. The phytochemical profiling of both extracts revealed the presence of a total of 47 phytocompounds belonging to diverse groups, namely organic and phenolic acids, and flavonoids. The plant was shown to be exempt of any cell toxicity, exhibited potent in vitro antioxidant activity, counteracted UVA-oxidative stress and GSH depletion in human keratinocytes, inhibited skin aging-related enzymes, enhanced wound healing process, inhibited the bacterial growth of P. aeruginosa, impaired biofilm formation, bacterial swimming and swarming, and the bacterial pigment (pyocyanin) production. These beneficial and protective effects are most likely due to the richness of the extracts in antioxidant compounds that enhance skin integrity, support collagen production, combat pathogens, and enhance the skin’s defense against oxidative stress. Nonetheless, additional investigations are imperative to uncover the complete capabilities of P. sativum, comprehend its modes of action and potential adverse effects on the skin, and develop efficient compositions to address diverse dermatological ailments.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used. Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

IM: Investigation, Writing – original draft. PI: Investigation, Writing – original draft. HA: Investigation, Writing – original draft. WB: Investigation, Writing – original draft. NS: Investigation, Writing – original draft. AA: Writing – review & editing. DM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that a financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article from the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Booth, LN , and Brunet, A . The aging epigenome. Mol Cell. (2016) 62:728–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.013

2. Harman, D . The aging process. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (1981) 78:7124–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7124

3. Mustafa, YF . Harmful free radicals in aging: a narrative review of their detrimental effects on health. Indian J Clin Biochem. (2023) 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12291-023-01147-y

4. Allied Market Research . (2021). Global Cosmetic Market by 2027. Available at: www.globenewswire.com

5. Hernandez, DF , Cervantes, EL , Luna-Vital, DA , and Mojica, L . Food-derived bioactive compounds with anti-aging potential for nutricosmetic and cosmeceutical products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2021) 61:3740–55. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1805407

6. Pan, M-H , Lai, C-S , Tsai, M-L , Wu, J-C , and Ho, C-T . Molecular mechanisms for anti-aging by natural dietary compounds. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2012) 56:88–115. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100509

7. Charles, D. J. (2012). 24—Parsley. In K. V. Peter (Éd.), Handbook of herbs and spices (second edition) (p. 430–451). Woodhead Publishing

8. Leung, AY , and Foster, S . Encyclopedia of common natural ingredients used in food, drugs, and cosmetics. (NAL QD415.L4 F and N B-2685) Numéro Ed. 2nd US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (1996).

9. Punoševac, M , Radović, J , Leković, A , and Kundaković-Vasović, T . A review of botanical characteristics, chemical composition, pharmacological activity and use of parsley. Arch Pharm. (2021) 71:207–23. doi: 10.5937/arhfarm71-31544

10. Mahdi, I , Bakrim, WB , Bitchagno, GTM , Annaz, H , Mahmoud, MF , and Sobeh, M . Unraveling the Phytochemistry, traditional uses, and biological and pharmacological activities of Thymus algeriensis Boiss. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2022) 2022:6487430. doi: 10.1155/2022/6487430

11. Farzaei, MH , Abbasabadi, Z , Ardekani, MRS , Rahimi, R , and Farzaei, F . Parsley: a review of ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and biological activities. J Tradit Chin Med. (2013) 33:815–26. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(14)60018-2

12. Mahmood, S , Hussain, S , and Malik, F . Accentuating the prodigious significance of Eclipta alba—an inestimable medicinal plant. Pak J Pharm Sci. (2013) 26:1259–66.

13. Slighoua, M , Mahdi, I , Di Cristo, F , Amaghnouje, A , Grafov, A , Boucetta, N, et al. Assessment of in vivo estrogenic and anti-inflammatory activities of the hydro-ethanolic extract and polyphenolic fraction of parsley (Petroselinum sativum Hoffm.). J Ethnopharmacol. (2021) 265:113290. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113290

14. Spernovasilis, N , Psichogiou, M , and Poulakou, G . Skin manifestations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. (2021) 34:72–9. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000717

15. Bakrim, WB , Nurcahyanti, ADR , Dmirieh, M , Mahdi, I , Elgamal, AM , El Raey, MA, et al. Phytochemical profiling of the leaf extract of Ximenia americana var. Caffra and its antioxidant, antibacterial, and antiaging activities in vitro and in Caenorhabditis elegans: a cosmeceutical and dermatological approach. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2022) 2022:3486257. doi: 10.1155/2022/3486257

16. Tawfeek, N , Fikry, E , Mahdi, I , Ochieng, MA , Bakrim, WB , Taarji, N, et al. Cupressus arizonica Greene: phytochemical profile and cosmeceutical and dermatological properties of its leaf extracts. Molecules. (2023) 28:1036. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031036

17. Gulcin, I . Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: an updated overview. Arch Toxicol. (2020) 94:651–715. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02689-3

18. Taslimi, P , and Gulçin, İ . Antioxidant and anticholinergic properties of olivetol. J Food Biochem. (2018) 42:e12516. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12516

19. Ferraro, G , Petruk, G , Maiore, L , Pane, F , Amoresano, A , Cinellu, MA, et al. Caged noble metals: encapsulation of a cytotoxic platinum(II)-gold(I) compound within the ferritin nanocage. Int J Biol Macromol. (2018) 115:1116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.142

20. Petruk, G , Raiola, A , Del Giudice, R , Barone, A , Frusciante, L , Rigano, MM, et al. An ascorbic acid-enriched tomato genotype to fight UVA-induced oxidative stress in normal human keratinocytes. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. (2016) 163:284–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.08.047

21. Sobeh, M , Youssef, FS , Esmat, A , Petruk, G , El-Khatib, AH , Monti, DM, et al. High resolution UPLC-MS/MS profiling of polyphenolics in the methanol extract of Syzygium samarangense leaves and its hepatoprotective activity in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic damage. Food Chem Toxicol. (2018) 113:145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.01.031

22. Del Giudice, R , Petruk, G , Raiola, A , Barone, A , Monti, DM , and Rigano, MM . Carotenoids in fresh and processed tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits protect cells from oxidative stress injury. J Sci Food Agric. (2017) 97:1616–23. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7910

23. Abbas, HA , Elsherbini, AM , and Shaldam, MA . Repurposing metformin as a quorum sensing inhibitor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Afr Health Sci. (2017) 17:808–19. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v17i3.24

24. Eruygur, N , Koçyiğit, UM , Taslimi, P , Ataş, M , Tekin, M , and Gülçin, İ . Screening the in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticholinesterase, antidiabetic activities of endemic Achillea cucullata (Asteraceae) ethanol extract. South African J. Bot. (2019) 120:141–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2018.04.001

25. Mahdi, I , Fahsi, N , Hafidi, M , Benjelloun, S , Allaoui, A , and Biskri, L . Rhizospheric phosphate solubilizing Bacillus atrophaeus GQJK17 S8 increases quinoa seedling, withstands heavy metals, and mitigates salt stress. Sustain For. (2021) 13:3307. doi: 10.3390/su13063307

26. Mostafa, I , Abbas, HA , Ashour, ML , Yasri, A , El-Shazly, AM , Wink, M, et al. Polyphenols from Salix tetrasperma impair virulence and inhibit quorum sensing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Molecules. (2020) 25:1341. doi: 10.3390/molecules25061341

27. Musthafa, KS , Ravi, AV , Annapoorani, A , Packiavathy, ISV , and Pandian, SK . Evaluation of anti-quorum-sensing activity of edible plants and fruits through inhibition of the N-acyl-homoserine lactone system in Chromobacterium violaceum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chemotherapy. (2010) 56:333–9. doi: 10.1159/000320185

28. Yeung Amy, TY , Torfs Ellen, CW , Farzad, J , Manjeet, B , Irith, W , Hancock Robert, EW, et al. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is controlled by a broad Spectrum of transcriptional regulators, including MetR. J Bacteriol. (2009) 191:5592–602. doi: 10.1128/JB.00157-09

29. Güven, L , Erturk, A , Miloğlu, FD , Alwasel, S , and Gulcin, İ . Screening of Antiglaucoma, antidiabetic, anti-Alzheimer, and antioxidant activities of Astragalus alopecurus pall—analysis of Phenolics profiles by LC-MS/MS. Pharmaceuticals. (2023) 16:659. doi: 10.3390/ph16050659

30. Karagecili, H , Yılmaz, MA , Ertürk, A , Kiziltas, H , Güven, L , Alwasel, SH, et al. Comprehensive metabolite profiling of Berdav Propolis using LC-MS/MS: determination of antioxidant, anticholinergic, Antiglaucoma, and antidiabetic effects. Molecules. (2023) 28:1739. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041739

31. Mallmann, LP , Rios, O , and Rodrigues, E . MS-FINDER and SIRIUS for phenolic compound identification from high-resolution mass spectrometry data. Food Res Int. (2023) 163:112315. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112315

32. Slighoua, M , Mahdi, I , Moussaid, FZ , Kamaly, OA , Amrati, FE , Conte, R, et al. LC-MS/MS and GC/MS profiling of Petroselinum sativum Hoffm. And its topical application on burn wound healing and related analgesic potential in rats. Meta. (2023) 13:260. doi: 10.3390/metabo13020260

33. Majma Sanaye, P , Mojaveri, MR , Ahmadian, R , Sabet Jahromi, M , and Bahramsoltani, R . Apigenin and its dermatological applications: a comprehensive review. Phytochemistry. (2022) 203:113390. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2022.113390

34. Jiratchayamaethasakul, C , Ding, Y , Hwang, O , Im, S-T , Jang, Y , Myung, S-W, et al. In vitro screening of elastase, collagenase, hyaluronidase, and tyrosinase inhibitory and antioxidant activities of 22 halophyte plant extracts for novel cosmeceuticals. Fish Aquat Sci. (2020) 23:6. doi: 10.1186/s41240-020-00149-8

35. Elgamal, AM , El Raey, MA , Gaara, A , Abdelfattah, MAO , and Sobeh, M . Phytochemical profiling and anti-aging activities of Euphorbia retusa extract: in silico and in vitro studies. Arab J Chem. (2021) 14:103159. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103159

36. Salem, MA , Radwan, RA , Mostafa, ES , Alseekh, S , Fernie, AR , and Ezzat, SM . Using an UPLC/MS-based untargeted metabolomics approach for assessing the antioxidant capacity and anti-aging potential of selected herbs. RSC Adv. (2020) 10:31511–24. doi: 10.1039/D0RA06047J

37. Szewczyk, K , Pietrzak, W , Klimek, K , Miazga-Karska, M , Firlej, A , Flisiński, M, et al. Flavonoid and phenolic acids content and in vitro study of the potential anti-aging properties of Eutrema japonicum (Miq.) Koidz cultivated in wasabi farm Poland. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6219. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126219

38. McDonald, M , Mila, I , and Scalbert, A . Precipitation of metal ions by plant polyphenols: optimal conditions and origin of precipitation. J Agric Food Chem. (1996) 44:599–606. doi: 10.1021/jf950459q

39. Malešev, D , and Kuntić, V . Investigation of metal-flavonoid chelates and the determination of flavonoids via metal-flavonoid complexing reactions. J Serb Chem Soc. (2007) 72:921–39. doi: 10.2298/JSC0710921M

40. Choi, J-E , and Moon, J-S . Physiological activities of parsley extracts as an ingredient of functional cosmetics. Asian J Beauty Cosmetol. (2017) 15:501–11. doi: 10.20402/ajbc.2017.0168

41. Khosravan, S , Alami, A , Mohammadzadeh-Moghadam, H , and Ramezani, V . The effect of topical use of Petroselinum Crispum (parsley) versus that of hydroquinone cream on reduction of epidermal Melasma: a randomized clinical trial. Holist Nurs Pract. (2017) 31:16–20. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000186

42. Eliseeva, T , and Shelestun, A . Parsley juice 6 scientifically proven benefits for the body. J Healthy Nutr Diet. (2023) 2:37–41.

43. Sahasrabuddhe, S . Parsley LEAF extract as an oil controller INPEEL off mask. Int J Pharm Chem Biol Sci. (2015) 5.

44. Motealleh, B , Zahedi, P , Rezaeian, I , Moghimi, M , Abdolghaffari, AH , and Zarandi, MA . Morphology, drug release, antibacterial, cell proliferation, and histology studies of chamomile-loaded wound dressing mats based on electrospun nanofibrous poly(ɛ-caprolactone)/polystyrene blends. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. (2014) 102:977–87. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33078

45. Shedoeva, A , Leavesley, D , Upton, Z , and Fan, C . Wound healing and the use of medicinal plants. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2019) 2019:2684108–30. doi: 10.1155/2019/2684108

46. Caruelle, J-P , Barritault, D , Jeanbat-Mimaud, V , Cammas-Marion, S , Langlois, V , Guerin, P, et al. Bioactive functionalized polymer of malic acid for bone repair and muscle regeneration. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. (2000) 11:979–91. doi: 10.1163/156856200744147

47. Jeanbat-Mimaud, V. , Barbaud, C. , Caruelle, J.-P. , Barritault, D. , Langlois, Valérie , Cammas-Marion, S., et al. (2002). Functionalized polymers of malic acid stimulate tissue repair presumably by regulating heparin growth factors bioavailability. In E. Chiellini, J. Sunamoto, C. Migliaresi, R. M. Ottenbrite, and D. Cohn (Éds.), Biomedical polymers and polymer therapeutics (p. 243–251). Springer US

48. Bowler, PG . Wound pathophysiology, infection and therapeutic options. Ann Med. (2002) 34:419–27. doi: 10.1080/078538902321012360

49. Robson, MC . WOUND INFECTION: a failure of wound healing caused by an imbalance of Bacteria. Surg Clin N Am. (1997) 77:637–50. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70572-7

50. Serra, R , Grande, R , Butrico, L , Rossi, A , Settimio, UF , Caroleo, B, et al. Chronic wound infections: the role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. (2015) 13:605–13. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1023291

51. Silva, LN , Zimmer, KR , Macedo, AJ , and Trentin, DS . Plant natural products targeting bacterial virulence factors. Chem Rev. (2016) 116:9162–236. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00184

52. Vattem, DA , Mihalik, K , Crixell, SH , and McLean, RJC . Dietary phytochemicals as quorum sensing inhibitors. Fitoterapia. (2007) 78:302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.03.009

53. Rahim, K , Saleha, S , Zhu, X , Huo, L , Basit, A , and Franco, OL . Bacterial contribution in chronicity of wounds. Microb Ecol. (2017) 73:710–21. doi: 10.1007/s00248-016-0867-9

54. Lau, GW , Hassett, DJ , Ran, H , and Kong, F . The role of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Trends Mol Med. (2004) 10:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.002

Keywords: parsley, skin aging, oxidative stress, enzymatic activities, antibacterial activities, Petroselinum sativum

Citation: Mahdi I, Imbimbo P, Annaz H, Bakrim WB, Sahri N, Alaoui A, Monti DM and Sobeh M (2024) Profiling of Petroselinum sativum (mill.) fuss phytoconstituents and assessment of their biocompatibility, antioxidant, anti-aging, wound healing, and antibacterial activities. Front. Nutr. 11:1338482. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1338482

Received: 14 November 2023; Accepted: 21 February 2024;

Published: 05 March 2024.

Edited by:

Mustafa Abdullah Yilmaz, Dicle University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Abdulahad Doğan, Yüzüncü Yıl University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2024 Mahdi, Imbimbo, Annaz, Bakrim, Sahri, Alaoui, Monti and Sobeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mansour Sobeh, bWFuc291ci5zb2JlaEB1bTZwLm1h

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.