- 1Human Nutrition and Eating Disorder Research Center, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

- 2Laboratory of Food Education and Sport Nutrition, Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

Obesity is a chronic, complex, and multifactorial disease resulting from the interaction of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors. It is characterized by excessive fat accumulation in adipose tissue, which damages health and deteriorates the quality of life. Although dietary treatment can significantly improve health, high attrition is a common problem in weight loss interventions with serious consequences for weight loss management and frustration. The strategy used to improve compliance has been combining dietary prescriptions and recommendations for physical activity with cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for weight management. This systematic review determined the dropout rate and predictive factors associated with dropout from CBT for adults with overweight and obesity. The data from the 37 articles selected shows an overall dropout rate between 5 and 62%. The predictive factors associated with attrition can be distinguished by demographics (younger age, educational status, unemployed status, and ethnicity) and psychological variables (greater expected 1-year Body Mass Index loss, previous weight loss attempts, perceiving more stress with dieting, weight and shape concerns, body image dissatisfaction, higher stress, anxiety, and depression). Common reasons for dropping out were objective (i.e., long-term sickness, acute illness, and pregnancy), logistical, poor job conditions or job difficulties, low level of organization, dissatisfaction with the initial results, lack of motivation, and lack of adherence. According to the Mixed Methods Appraisal quality analysis, 13.5% of articles were classified as five stars, and none received the lowest quality grade (1 star). The majority of articles were classified as 4 stars (46%). At least 50% of the selected articles exhibited a high risk of bias. The domain characterized by a higher level of bias was that of randomization, with more than 60% of the articles having a high risk of bias. The high risk of bias in these articles can probably depend on the type of study design, which, in most cases, was observational and non-randomized. These findings demonstrate that CBT could be a promising approach for obesity treatment, achieving, in most cases, lower dropout rates than other non-behavioral interventions. However, more studies should be conducted to compare obesity treatment strategies, as there is heterogeneity in the dropout assessment and the population studied. Ultimately, gaining a deeper understanding of the comparative effectiveness of these treatment strategies is of great value to patients, clinicians, and healthcare policymakers.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022369995 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022369995.

Introduction

It is well known that obesity is a significant public health burden (1), affecting both physical and psychological status. According to the recently published evidence-based practice guide of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, obesity is recognized as excess adiposity. It is correlated with many adverse health outcomes, such as mortality risk, prediabetes, type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain types of cancer (2, 3). Dietary administration combined with physical activity is the most recommended treatment for weight loss (4).

Although dietary treatment can significantly improve health, dietary modifications are difficult to make on an individual basis, and obstacles to changing behavior may also be influenced by psychological factors in addition to biological ones. For this reason, high attrition is a common problem in weight loss interventions with serious consequences for weight loss management and frustration (5). Understanding the factors contributing to attrition could allow the identification of patients at the highest risk of dropout, supporting them during the intervention, or identifying more suitable intervention options.

Previous studies have associated high attrition rates with many variables, such as demographics (age, age at the onset of obesity, sex, occupational status, education) (6–9), anthropometrics (body-mass index BMI) (9), psychological aspects (high weight loss expectations, health status, self-esteem, perception of one’s body image, social or family support, anxiety, depression) (7, 9–13), behavior (eating habits and behavior, binge eating, physical activity level, alcohol consumption, lack of motivation, stress, and smoking) (9), and treatment-related factors (early nutritional interventions, previous dietary treatments, type of treatments, initial response, and expectation of weight loss) (8, 13–16). A consistent set of predictors has not yet been identified because of the large variety of study settings and methodologies used.

The initial response to treatment has emerged among the predictive factors related to treatment (16, 17). In fact, in most cases, the dropout percentage increases if the initial weight loss is unsatisfactory for the patient. Patients discontinue the program in the first weeks (early dropout) because of “failure to achieve the expected goal” and “feeling frustrated and disappointed.”

Regarding the psychological profile of patients before treatment, the dropout rate is higher when there is a greater state of anxiety and depression or, in general, a compromised state of mental health. These factors correlate with a lack of trust in healthcare personnel, lower motivation to undertake the path, or greater difficulty tolerating possible failure (10).

According to a different position statement from the Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (18) and from the Brazilian Association for the Study of Obesity and metabolic syndrome (ABESO), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) should be used for weight management in patients with overweight and obesity (class of recommendation I; level of evidence A) (18, 19). CBT is the oldest and most studied behavior change theory used in nutrition counseling. It provides a theoretical basis for most structured diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy programs. It is based on the premise of CBT theory that behavioral and emotional reactions are learned using cognitive and behavioral strategies. CBT focuses on external factors, such as environmental stimuli and reinforcement, and internal factors, such as thoughts and mood changes. CBT aims to help patients acquire specific cognitive and behavioral skills to increase adherence to the dietary and physical activity changes required for body weight management that can be used going forward to support their mental health and wellness.

Dietitians apply strategies on both factors to unlearn undesirable eating patterns and behaviors and replace them with more functional thoughts and actions (20, 21). CBT strategies include goal setting, self-monitoring, problem-solving, social support, stress management, stimulus control, cognitive restructuring, relapse prevention, rewards, and contingency management (20).

This study systematically reviewed the dropout rate and predictive factors of dropout in cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) in adult patients with overweight or obesity in order to provide a comprehensive assessment of the literature about this topic.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was performed based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method (22). The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. The language used was English. Only full-text articles published in the last 20 years and full-text articles available were included.

Clinical and observational trials, case reports, and case series were included to investigate the dropout rate and predictive factors associated with the dropout rate in adults living with overweight and obesity undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In-vitro and animal studies, guidelines, letters, editorials, comments, news articles, conference abstracts, theses, and dissertations were excluded.

The study protocol was registered on the PROSPERO platform (registration number: CRD42022369995).

Literature research strategy

An electronic search was conducted with subject index terms, including “patient dropouts,” “weight loss,” “diet reducing,” “weight loss therapy,” and “diet therapy.” Google Scholar was used to search for gray literature, and some references found in the review articles were included manually. The study population consisted of adults aged 18–65 years old with overweight or obesity (Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2). The intervention was cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and the comparison was standard dietary treatment. The research question, and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria based on PICOS strategy are presented in Table 1.

Study selection

Two authors (LCLN and FM) independently performed the research and study selection. The articles found in the electronic database were organized using the Mendeley reference manager and Rayyan software (23), following two steps: (1) reading the titles and abstracts, and (2) evaluation of the complete articles selected in the previous stage and inclusion of other studies present in the references of the selected articles. The decision to include the articles was based on the PICOS strategy: population (P) – adult (18–65 years) patients with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2); intervention (I) – cognitive behavioral treatment; control (C) – standard dietary treatment; outcome (O) – attrition rate and weight loss; and study type (S) – clinical and observational trials, case reports, and case series. These inclusion criteria were used to identify potentially relevant abstracts, and if abstracts were coherent with them, full papers were obtained and assessed. In cases of disagreement, a third author (CF) reviewed the full-text articles to make a decision. Studies meeting the specified inclusion criteria were included in the qualitative analysis. Additionally, relevant articles were manually added to the search. Study sample characteristics, design, intervention, dropout rate, results, and quality were extracted. The risk of bias was assessed using the RoB 2.0 Cochrane tool (24), and the quality of evidence was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal (MMAT) system (25).

Results

After searching the databases using search strings, 5,509 articles were identified. Figure 1 describes the selection phase and the retained articles in each phase. After selection, 37 articles that used the CBT approach in weight loss interventions addressed the dropout rate and associated predictive factors. The details of each selected article are listed in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, the articles were categorized based on their origin, as follows: 20 studies were from Italy (54%), 6 from the USA, 2 from Germany, 2 from Sweden, 2 from Switzerland, 2 from Spain, 2 from the Netherlands, and the other countries with one article each (Denmark, Japan, Portugal, Lebanon, Bahrain). The selected sample, according to the inclusion criteria, comprised adult patients (aged 18–65 years) with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2). During the analysis, it emerged that the predominant gender was female. The samples included in the various studies did not exhibit any other associated pathologies, except in some specific studies. For example, some studies have included breast cancer survivors (34), patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (25), patients diagnosed with T2DM (34), and patients with binge eating disorder (BED) (31, 39, 54).

Overall, dropout rates were between 5 to 62%. Dropout results were associated with several predictive factors, including demographic and psychological variables. In terms of demographic variables, some studies showed that younger age (35, 61), educational status (38), unemployed status (55), and ethnicity (38) could influence the dropout rate. Regarding psychological factors, attrition has been correlated with a higher expectation of 1-year BMI loss (28), weight and shape concerns (43, 55), body image dissatisfaction (58), higher stress (51), anxiety (58) and depression (43, 58). Other studies have associated an increased dropout rate with an increasing number of previous weight loss attempts (27), age at first diet attempt (52) and perceived stress with dieting (44). In the study by Sasdelli et al. (58), the dropout rate decreased with an increase in concern for present health, motivation, and consciousness about the importance of physical activity. The most frequent predictive factors are age and baseline BMI/weight referred to in 31 and 19% studies, respectively. Table 3 presents all the reported predictive factors analyzed in the selected studies.

Table 3. Reported predictive factors to dropout in the selected articles with CBT in patients with overweight or obesity.

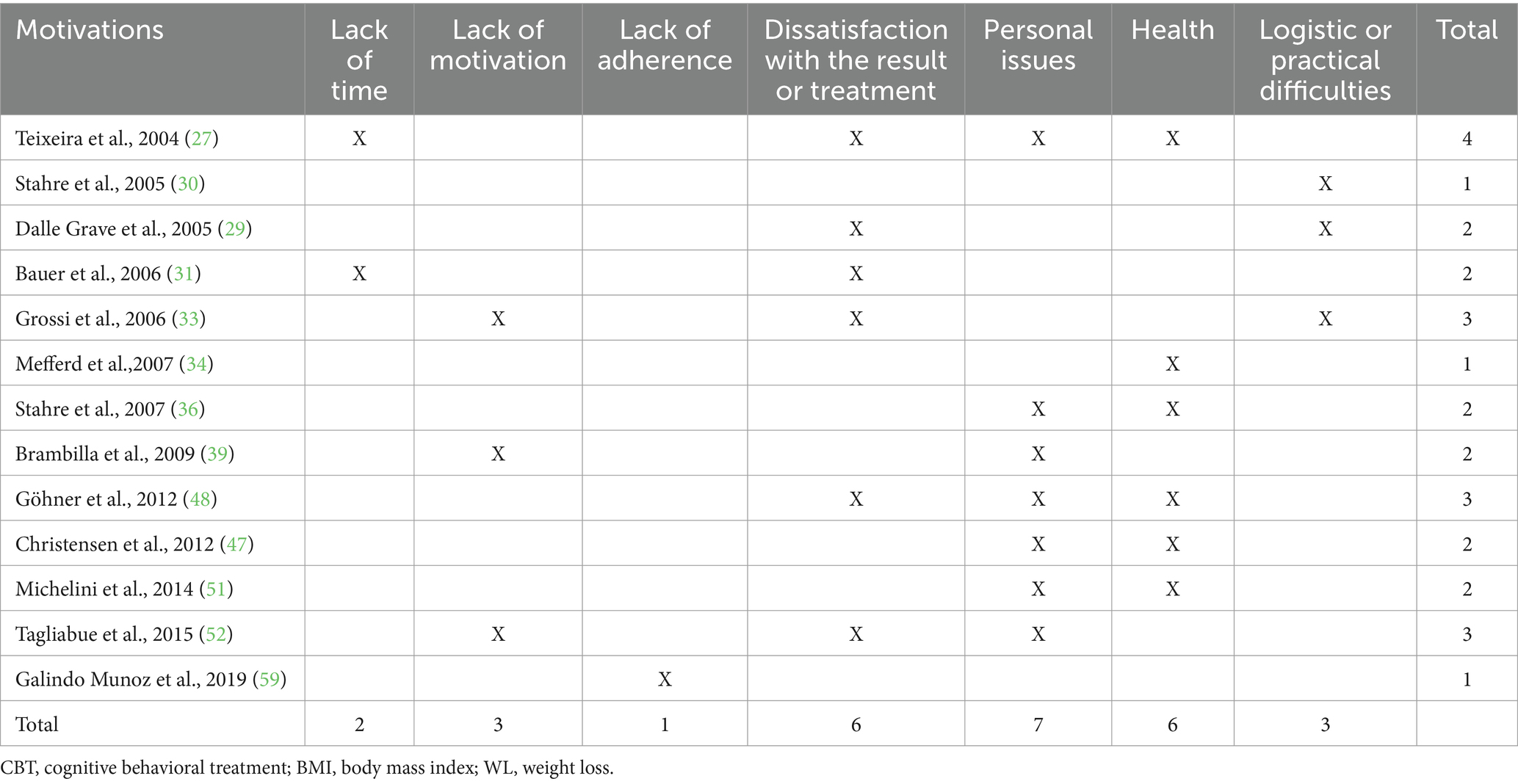

Common reasons for dropping out are reported in Table 4. Generally, the articles reported objective reasons (27, 36, 48, 51), such as long-term sickness, acute illness, pregnancy, logistics (28, 30), poor job conditions or job difficulties (36, 51, 55), low level of organization (55), dissatisfaction with initial results (27, 28, 31, 48, 52), lack of motivation (28, 39, 48, 52) and lack of adherence (59).

Table 4. Motivations to dropout in CBT patients with overweight or obesity, according to selected articles reporting this aspect.

Twenty-three of the included studies used CBT as the only approach (27–29, 32, 33, 35, 37–40, 44–46, 49–51, 53–56, 58, 60–62), three as a control group (31, 57, 59), and eleven as an intervention group (30, 34, 36, 41–43, 47, 48, 51, 52, 63, 64). Different strategies were used for the intervention group (IG) in trials where CBT was the control group. In the study by Muñoz et al. (59) IG was characterized by a Cognitive Training Intervention, which consisted of a hypocaloric diet and 12 cognitive training sessions via Brain Exercise (59), while in other studies by Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy (LSG) (57) or sibutramine administration (31). Most trials were conducted by dietitians or certified nutritionists, often CBT experts. Other professionals often involved included physicians, psychologists, and physical therapists.

In addition to analyzing dropout rate and weight loss, biochemical parameters (32, 34, 42, 59, 60, 62), such as glycaemic and lipid profiles, or cognitive and psychological variables, were assessed using specific questionnaires, such as the Goals and Relative Weights Questionnaire (GRWQ), Body Uneasiness Test (BUT), Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) and Binge Eating Scale (BES) (31, 35, 39, 40, 48, 49, 52, 54, 57, 59, 60, 62, 63).

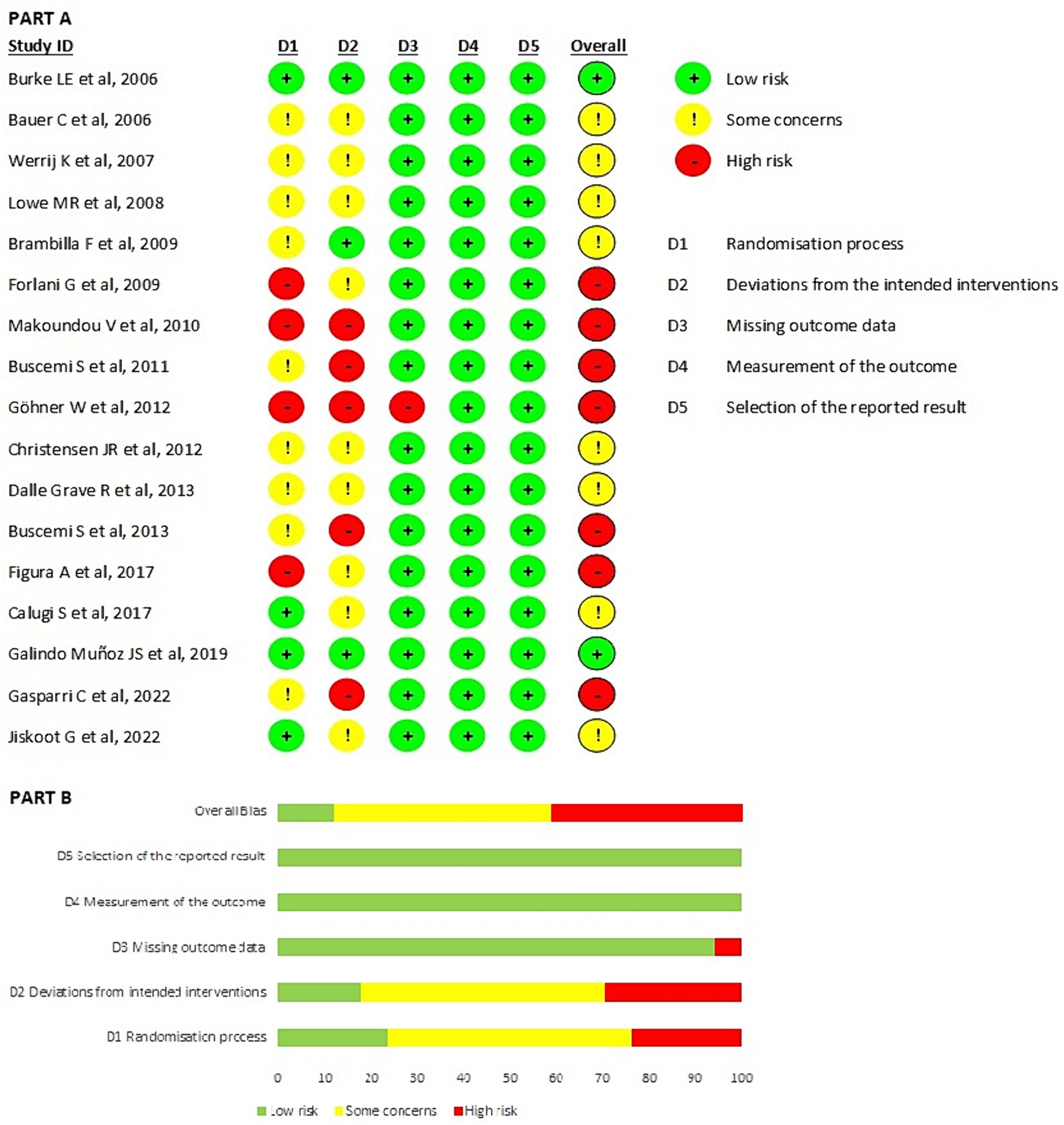

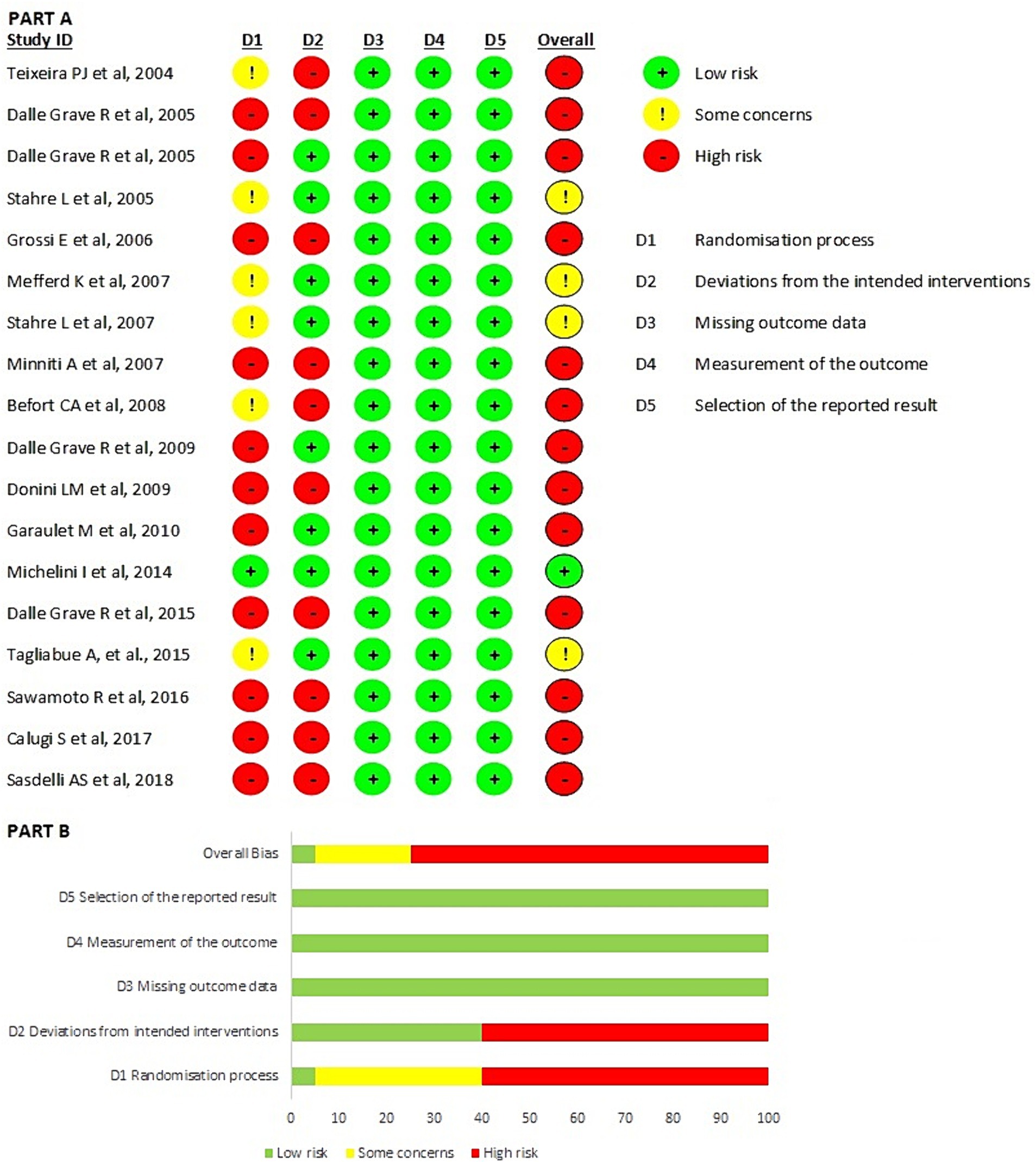

According to the MMAT quality analysis, 13.5% of articles were classified as 5 stars, and none received the lowest quality grade (1 star). The majority of articles were classified as 4 stars (46%). Seventeen studies were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (Figure 2), and 20 studies were included in the per-protocol analysis (Figure 3). The highest domains with risk of bias in both the intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis were domain 1, which pertained to the randomization process, and domain 2, which addressed deviations from the intended interventions. All other domains (D5: selection of the reported result, D4: measurement of the outcome; and D3: missing outcome data) had a low risk of bias. The overall valuation in the intention-to-treat analysis revealed 7 articles at high risk of bias (40%), while in the per-protocol analysis, there were 15 articles (75%). Also, in the intention-to-treat analysis, two articles (11.8%) were at low risk of bias, while in the per-protocol, there was one. In summary, more than half of the selected articles had a high risk of bias. The domain characterized by a higher level of bias was randomization, which was caused by the type of study design.

Figure 2. Results of risk of bias analysis of intention-to-treat studies (24). (A) Risk of Bias by article included on each domain. (B) Overall risk of Bias percentage on each domain. From Sterne et al. (65).

Figure 3. Results of risk of bias analysis of per protocol studies (24). (A) Risk of Bias by article included on each domain. (B) Overall risk of Bias percentage on each domain. From Sterne et al. (65).

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed the dropout rate and predictive factors associated with dropout from cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) in adult patients with overweight or obesity. The review demonstrated that the dropout rate ranges between 5 and 62%. As indicated in the results, some demographic and psychological factors could be the predictors.

Most included studies considered psychological variables, revealing a significant association with the dropout rate. These findings support the hypothesis that analyzing the psychological profile of patients with overweight or obesity through specific questionnaires can help identify individuals at higher dropout risk. Furthermore, such assessments can assist in providing appropriate support during the intervention or determining suitable intervention.

There were common reasons among these studies for patients to discontinue treatment. Some of these issues, such as organization and logistics, can be resolved by providing practical tools to address the barriers to successful treatment. Others, such as dissatisfaction with initial results and lack of motivation, could be managed by helping patients to understand that an improvement in general health is already obtained with a weight loss of 5–10% of the initial weight, thereby reducing their weight loss expectations and weight loss targets. According to Dalle Grave et al., regardless of the degree of weight loss, people with obesity have a high prevalence of body dissatisfaction, which improves at the 6-month follow-up following treatment (66).

With this in mind, it is important to resize the patient’s expectations about weight loss (often overestimated with respect to the real therapeutic goal) through better communication by the healthcare professional or the multidisciplinary team and to pay more attention during the initial phase of treatment.

Moreover, this review revealed that most of the included articles showed that CBT led to significant improvements in psychological variables and BED episodes. In 2016, Calugi et al. (54) concluded that although the BED group maintained higher psychological impairment than the group without BED at 6 months, more than half of the BED patients were no longer diagnosable at 5 years follow-up.

In studies where CBT was used as the only approach, the dropout rate ranged between 10 and 62%. Not all studies considered the same follow-up period, and in studies with longer follow-up periods, the dispersion increased exponentially. Nevertheless, in the study by Brambilla et al. (39) where CBT was used in both the intervention and control groups, the dropout rate was low (16%). Since CBT was the only therapy common to all three interventions, it is probably effective in preventing dropout independently of the results obtained, as shown by the authors.

Furthermore, there were several studies where CBT was used in the intervention group, and the dropout rate was higher than or equal to the control group. In the study by Mefferd et al. (34) dropouts (10.6%) were assigned to the intervention group. However, considering that the control group consisted of a wait-list, it is difficult to conclude the effectiveness of CBT. In a study by Stahre et al. (36) there were no significant differences between the two groups. Although, the percentage of completers was very high in both cases (87% in the intervention group with CBT and 80% in the control group). Donini et al. (41), instead, showed higher treatment duration in Nutritional Psycho-Physical Reconditioning (NPPR) and a significantly lower dropout rate (5.5% vs. 54.4% in standard diet intervention). In addition, weight loss and fat mass reduction were higher in NPPR. The authors of this study hypothesized that the low dropout rate could be ascribed to the multidisciplinary and cognitive-behavioral approach, which provides effective tools to address barriers that usually hinder compliance (e.g., establishing acceptable goals) and increase patients’ motivation to adhere to the procedure. They also affirmed that the improvement in anxiety and depression in the NPPR group allowed one to maintain an adequate lifestyle and sustain the achieved results.

The data from this review have clinical implications as they could help clinicians identify those at a higher risk of dropping out by investigating specific factors as best as possible. In fact, the importance of motivation in the failure of weight loss treatment makes the assessment of motivation a core procedure for all patients with obesity and overweight, both before and during treatment. It has been recently suggested that the importance of motivation in the failure of weight loss programs makes the assessment of motivation a core procedure for all patients living with obesity, both before and during treatment. Armstrong et al. suggested that a motivational interview (a directive, patient-centered counseling approach focused on exploring and resolving ambivalence) appears to enhance weight loss in people with overweight or obesity (67). Moreover, the motivational interview could be used as a separate intervention throughout the course of treatment, when the motivation of obese patients decreases (68). Furthermore, the dissatisfaction with the initial results of the treatment association with dropouts indicates that intensive treatment in the first part of the program might be useful. For example, increasing the number of sessions, offering them closer together, or even offering intermediate telephone contacts could be a potentially effective way to increase the initial weight loss rate and consequently reduce the dropout rate.

This study has several limitations. Most of the studies included, especially those added manually, had an observational and non-randomized design, which resulted in a high risk of bias, as shown in Figure 3. This data could probably be because of the decision to add several articles published by the same research group (28, 29, 33, 40, 50, 53, 54, 56, 60, 61), notwithstanding that this is a leading expert team and permitted a better understanding of the advantages and considerations of CBT. Despite the high risk of bias, the observational design allows clinicians to analyze and comprehend the complex phenomenon of obesity and evaluate numerous variables. Another limitation may be derived from the search strategy because the acronym CBT can be used for both “cognitive behavioural therapy” and “cognitive behavioural treatment” or “cognitive behavioural theory.” Moreover, most of the time, these terms are also reported with “-” divisors. Furthermore, it’s not possible to define the exact approach used in the selected studies; in particular, if the authors used generic forms of CBT or specific form of CBT for obesity management. Indeed, a specific form of CBT, called personalized CBT for obesity (CBT-OB), has been developed and widely studied in recent decades. The main goals of CBT-OB are to help patients to (i) reach, accept and maintain a healthy amount of weight loss (i.e., 5–10% of their starting body weight); (ii) adopt and maintain a lifestyle conducive to weight control; and (iii) develop a stable “weight-control mind-set.” Specific integrations enable the treatment to be personalized, and help patients address with specific strategies and procedures the processes that could be, respectively, associated with drop-out, the amount of weight lost, and maintaining a lower weight in the long term treatment. CBT-OB therapists adopt a therapeutic style designed to develop and nurture a collaborative working relationship (the therapist and patient(s) work together as a team) (69, 70). Given the prevalence of long lasting eating disorders (ED) and their association with high attrition from weight management programs, the search strategy could have included specific terms and amplified the results, this could be addressed in future studies. The strength of the search lies in being systemic and in including all articles concerning CBT in treating obesity, regardless of other correlated pathologies.

Future research with well-designed randomized clinical trials involving different behavioral approaches could focus on answering how it could affect the adherence to the treatment and prevent the dropping out of adults living with overweight and obesity.

Conclusion

High attrition is a common problem in weight loss interventions and seriously affects weight loss management and frustration. The purpose of this current systematic review was to determine the predictive factors of dropout in treatment of people with overweight and obesity. The main predictive factors are younger age and baseline BMI/weight; and the common motivations of dropping out are dissatisfaction with the result or treatment, personal issues and health problems. Moreover, this review provides additional evidence with respect to CBT leading to significant improvements in psychological variables. These findings have important clinical implications as they could help clinicians identify those at a higher risk of dropping out, support them during the intervention, or find more suitable intervention options.

However, this review highlights the need for more rigorous and well-designed clinical trials to provide more definitive evidence. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of the comparative effectiveness of these treatment strategies is of great value to patients, clinicians, and healthcare policymakers.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CF and FM: conceptualization. LN, CF, and AT: methodology. LN, MG, CF, and FM: investigation and writing – original draft preparation. LN, CF, FM, MG, SF, and AT: data curation and writing—review and editing. AT and CF: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the present version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Riccardo Dalle Grave for the precious contributors for the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Afshin, A, Forouzanfar, MH, Reitsma, MB, Sur, P, Estep, K, Lee, A, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362

2. Jensen, MD, Ryan, DH, Apovian, CM, Ard, JD, Comuzzie, AG, Donato, KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 63:2985–3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004

3. Morgan-Bathke, M, Raynor, HA, Baxter, SD, Halliday, TM, Lynch, A, Malik, N, et al. Medical nutrition therapy interventions provided by dietitians for adult overweight and obesity management: an academy of nutrition and dietetics evidence-based practice guideline. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2023) 123:520–545.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.11.014

4. Wharton, S, Lau, DCW, Vallis, M, Sharma, AM, Biertho, L, Campbell-Scherer, D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. (2020) 192:E875–91. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191707

5. Miller, BML, and Brennan, L. Measuring and reporting attrition from obesity treatment programs: a call to action! Obes Res Clin Pract. (2015) 9:187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.08.007

6. Honas, JJ, Early, JL, Frederickson, DD, and O’Brien, MS. Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obes Res. (2003) 11:888–94. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.122

7. Jiandani, D, Wharton, S, Rotondi, MA, Ardern, CI, and Kuk, JL. Predictors of early attrition and successful weight loss in patients attending an obesity management program. BMC Obes. (2016) 3:14. doi: 10.1186/s40608-016-0098-0

8. Fabricatore, AN, Wadden, TA, Moore, RH, Butryn, ML, Heymsfield, SB, and Nguyen, AM. Predictors of attrition and weight loss success: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. (2009) 47:685–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.004

9. Dalle Grave, R, Suppini, A, Calugi, S, and Marchesini, G. Factors associated with attrition in weight loss programs. Int J Behav Consult Ther. (2006) 2:341–53. doi: 10.1037/h0100788

10. McLean, RC, Morrison, DS, Shearer, R, Boyle, S, and Logue, J. Attrition and weight loss outcomes for patients with complex obesity, anxiety and depression attending a weight management programme with targeted psychological treatment. Clin Obes. (2016) 6:133–42. doi: 10.1111/cob.12136

11. Clark, MM, Niaura, R, King, TK, and Pera, V. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav. (1996) 21:509–13. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00081-x

12. Ponzo, V, Scumaci, E, Goitre, I, Beccuti, G, Benso, A, Belcastro, S, et al. Predictors of attrition from a weight loss program. A study of adult patients with obesity in a community setting. Eat Weight Disord. (2021) 26:1729–36. doi: 10.1007/s40519-020-00990-9

13. Colombo, O, Ferretti, VV, Ferraris, C, Trentani, C, Vinai, P, Villani, S, et al. Is drop-out from obesity treatment a predictable and preventable event? Nutr J. (2014) 13:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-13

14. Fowler, JL, Follick, MJ, Abrams, DB, and Rickard-Figueroa, K. Participant characteristics as predictors of attrition in worksite weight loss. Addict Behav. (1985) 10:445–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(85)90044-9

15. Batterham, M, Tapsell, LC, and Charlton, KE. Predicting dropout in dietary weight loss trials using demographic and early weight change characteristics: implications for trial design. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2016) 10:189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.05.005

16. Hadžiabdić, MO, Mucalo, I, Hrabač, P, Matić, T, Rahelić, D, and Božikov, V. Factors predictive of drop-out and weight loss success in weight management of obese patients. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2015) 28:24–32. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12270

17. Perna, S, Spadaccini, D, Riva, A, Allegrini, P, Edera, C, Faliva, MA, et al. A path model analysis on predictors of dropout (at 6 and 12 months) during the weight loss interventions in endocrinology outpatient division. Endocrine. (2018) 61:447–61. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1563-y

18. Yumuk, V, Tsigos, C, Fried, M, Schindler, K, Busetto, L, Micic, D, et al. Obesity management task force of the European Association for the Study of obesity. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts. (2015) 8:402–24. doi: 10.1159/000442721

19. Pepe, RB, Lottenberg, AM, Fujiwara, CTH, Beyruti, M, Cintra, DE, Machado, RM, et al. Position statement on nutrition therapy for overweight and obesity: nutrition department of the Brazilian association for the study of obesity and metabolic syndrome (ABESO-2022). Diabetol Metab Syndr. (2023) 15:124. doi: 10.1186/s13098-023-01037-6

20. Swan, WI, Vivanti, A, Hakel-Smith, NA, Hotson, B, Orrevall, Y, Trostler, N, et al. Nutrition care process and model update: toward realizing people-centered care and outcomes management. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2017) 117:2003–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.07.015

21. Spahn, JM, Reeves, RS, Keim, KS, Laquatra, I, Kellogg, M, Jortberg, B, et al. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. (2010) 110:879–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.021

22. Liberati, A, Altman, DG, Tetzlaff, J, Mulrow, C, Gøtzsche, PC, Ioannidis, JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. (2009) 62:1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

23. Ouzzani, M, Hammady, H, Fedorowicz, Z, and Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

24. Sterne, JAC, Savović, J, Page, MJ, Elbers, RG, Blencowe, NS, Boutron, I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

25. Hong, QN, Fàbregues, S, Bartlett, G, Boardman, F, Cargo, M, Dagenais, P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. EFI. (2018) 34:285–91. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

26. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

27. Teixeira, PJ, Going, SB, Houtkooper, LB, Cussler, EC, Metcalfe, LL, Blew, RM, et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. (2004) 28:1124–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802727

28. Dalle Grave, R, Melchionda, N, Calugi, S, Centis, E, Tufano, A, Fatati, G, et al. Continuous care in the treatment of obesity: an observational multicentre study. J Intern Med. (2005) 258:265–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01524.x

29. Dalle Grave, R, Calugi, S, Molinari, E, Petroni, ML, Bondi, M, Compare, A, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res. (2005) 13:1961–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.241

30. Stahre, L, and Hällström, T. A short-term cognitive group treatment program gives substantial weight reduction up to 18 months from the end of treatment. A randomized controlled trial. Eat Weight Disord. (2005) 10:51–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03353419

31. Bauer, C, Fischer, A, and Keller, U. Effect of sibutramine and of cognitive-behavioural weight loss therapy in obesity and subclinical binge eating disorder. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2006) 8:289–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2005.00504.x

32. Burke, LE, Choo, J, Music, E, Warziski, M, Styn, MA, Kim, Y, et al. PREFER study: a randomized clinical trial testing treatment preference and two dietary options in behavioral weight management--rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. (2006) 27:34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.08.002

33. Grossi, E, Dalle Grave, R, Mannucci, E, Molinari, E, Compare, A, Cuzzolaro, M, et al. Complexity of attrition in the treatment of obesity: clues from a structured telephone interview. Int J Obes. (2006) 30:1132–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803244

34. Mefferd, K, Nichols, JF, Pakiz, B, and Rock, CL. A cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote weight loss improves body composition and blood lipid profiles among overweight breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2007) 104:145–52. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9410-x

35. Minniti, A, Bissoli, L, Di Francesco, V, Fantin, F, Mandragona, R, Olivieri, M, et al. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: comparison of dropout rate and treatment outcome. Eat Weight Disord. (2007) 12:161–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03327593

36. Stahre, L, Tärnell, B, Håkanson, C-E, and Hällström, T. A randomized controlled trial of two weight-reducing short-term group treatment programs for obesity with an 18-month follow-up. Int J Behav Med. (2007) 14:48–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02999227

37. Befort, CA, Nollen, N, Ellerbeck, EF, Sullivan, DK, Thomas, JL, and Ahluwalia, JS. Motivational interviewing fails to improve outcomes of a behavioral weight loss program for obese African American women: a pilot randomized trial. J Behav Med. (2008) 31:367–77. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9161-8

38. Lowe, MR, Tappe, KA, Annunziato, RA, Riddell, LJ, Coletta, MC, Crerand, CE, et al. The effect of training in reduced energy density eating and food self-monitoring accuracy on weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2008) 16:2016–23. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.270

39. Brambilla, F, Samek, L, Company, M, Lovo, F, Cioni, L, and Mellado, C. Multivariate therapeutic approach to binge-eating disorder: combined nutritional, psychological and pharmacological treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2009) 24:312–7. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832ac828

40. Dalle Grave, R, Calugi, S, Corica, F, Di Domizio, S, and Marchesini, GQUOVADIS Study Group. Psychological variables associated with weight loss in obese patients seeking treatment at medical centers. J Am Diet Assoc. (2009) 109:2010–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.09.011

41. Donini, LM, Savina, C, Castellaneta, E, Coletti, C, Paolini, M, Scavone, L, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to obesity. Eat Weight Disord. (2009) 14:23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03327791

42. Forlani, G, Lorusso, C, Moscatiello, S, Ridolfi, V, Melchionda, N, Di Domizio, S, et al. Are behavioural approaches feasible and effective in the treatment of type 2 diabetes? A propensity score analysis vs. prescriptive diet. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2009) 19:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.06.004

43. Werrij, MQ, Jansen, A, Mulkens, S, Elgersma, HJ, Ament, AJHA, and Hospers, HJ. Adding cognitive therapy to dietetic treatment is associated with less relapse in obesity. J Psychosom Res. (2009) 67:315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.011

44. Garaulet, M, Corbalán-Tutau, MD, Madrid, JA, Baraza, JC, Parnell, LD, Lee, Y-C, et al. PERIOD2 variants are associated with abdominal obesity, psycho-behavioral factors, and attrition in the dietary treatment of obesity. J Am Diet Assoc. (2010) 110:917–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.017

45. Makoundou, V, Bobbioni-Harsch, E, Gachoud, JP, Habicht, F, Pataky, Z, and Golay, A. A 2-year multifactor approach of weight loss maintenance. Eat Weight Disord. (2010) 15:e9–e14. doi: 10.1007/BF03325275

46. Buscemi, S, Batsis, JA, Verga, S, Carciola, T, Mattina, A, Citarda, S, et al. Long-term effects of a multidisciplinary treatment of uncomplicated obesity on carotid intima-media thickness. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2011) 19:1187–92. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.313

47. Christensen, JR, Overgaard, K, Carneiro, IG, Holtermann, A, and Søgaard, K. Weight loss among female health care workers--a 1-year workplace based randomized controlled trial in the FINALE-health study. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:625. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-625

48. Göhner, W, Schlatterer, M, Seelig, H, Frey, I, Berg, A, and Fuchs, R. Two-year follow-up of an interdisciplinary cognitive-behavioral intervention program for obese adults. J Psychol. (2012) 146:371–91. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.642023

49. Buscemi, S, Castellini, G, Batsis, JA, Ricca, V, Sprini, D, Galvano, F, et al. Psychological and behavioural factors associated with long-term weight maintenance after a multidisciplinary treatment of uncomplicated obesity. Eat Weight Disord. (2013) 18:351–8. doi: 10.1007/s40519-013-0059-2

50. Dalle Grave, R, Calugi, S, Gavasso, I, El Ghoch, M, and Marchesini, G. A randomized trial of energy-restricted high-protein versus high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in morbid obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2013) 21:1774–81. doi: 10.1002/oby.20320

51. Michelini, I, Falchi, AG, Muggia, C, Grecchi, I, Montagna, E, De Silvestri, A, et al. Early dropout predictive factors in obesity treatment. Nutr Res Pract. (2014) 8:94–102. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2014.8.1.94

52. Tagliabue, A, Repossi, I, Trentani, C, Ferraris, C, Martinelli, V, and Vinai, P. Cognitive-behavioral treatment reduces attrition in treatment-resistant obese women: results from a 6-month nested case-control study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2015) 36:368–73.

53. Dalle Grave, R, Calugi, S, Compare, A, El Ghoch, M, Petroni, ML, Tomasi, F, et al. Weight loss expectations and attrition in treatment-seeking obese women. Obes Facts. (2015) 8:311–8. doi: 10.1159/000441366

54. Calugi, S, Ruocco, A, El Ghoch, M, Andrea, C, Geccherle, E, Sartori, F, et al. Residential cognitive-behavioral weight-loss intervention for obesity with and without binge-eating disorder: a prospective case-control study with five-year follow-up. Int J Eat Disord. (2016) 49:723–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.22549

55. Sawamoto, R, Nozaki, T, Furukawa, T, Tanahashi, T, Morita, C, Hata, T, et al. Predictors of dropout by female obese patients treated with a group cognitive behavioral therapy to promote weight loss. Obes Facts. (2016) 9:29–38. doi: 10.1159/000442761

56. Calugi, S, Marchesini, G, El Ghoch, M, Gavasso, I, and Dalle, GR. The influence of weight-loss expectations on weight loss and of weight-loss satisfaction on weight maintenance in severe obesity. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2017) 117:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.001

57. Figura, A, Rose, M, Ordemann, J, Klapp, BF, and Ahnis, A. Changes in self-reported eating patterns after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a pre-post analysis and comparison with conservatively treated patients with obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. (2017) 13:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.003

58. Sasdelli, AS, Petroni, ML, Delli Paoli, A, Collini, G, Calugi, S, Dalle Grave, R, et al. Expected benefits and motivation to weight loss in relation to treatment outcomes in group-based cognitive-behavior therapy of obesity. Eat Weight Disord. (2018) 23:205–14. doi: 10.1007/s40519-017-0475-9

59. Galindo Muñoz, JS, Morillas-Ruiz, JM, Gómez Gallego, M, Díaz Soler, I, Barberá Ortega, MDC, Martínez, CM, et al. Cognitive training therapy improves the effect of hypocaloric treatment on subjects with overweight/obesity: a randomised clinical trial. Nutrients. (2019) 11:925. doi: 10.3390/nu11040925

60. Dalle Grave, R, Calugi, S, Bosco, G, Valerio, L, Valenti, C, El Ghoch, M, et al. Personalized group cognitive behavioural therapy for obesity: a longitudinal study in a real-world clinical setting. Eat Weight Disord. (2020) 25:337–46. doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0593-z

61. Calugi, S, Andreoli, B, Dametti, L, Dalle Grave, A, Morandini, N, and Dalle, GR. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on patients with obesity after intensive cognitive behavioral therapy-a case-control study. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2021. doi: 10.3390/nu13062021

62. Gasparri, C, Perna, S, Peroni, G, Riva, A, Petrangolini, G, Faliva, MA, et al. Multidisciplinary residential program for the treatment of obesity: how body composition assessed by DXA and blood chemistry parameters change during hospitalization and which variations in body composition occur from discharge up to 1-year follow-up. Eat Weight Disord. (2022) 27:2701–11. doi: 10.1007/s40519-022-01412-8

63. Jiskoot, G, Dietz de Loos, A, Timman, R, Beerthuizen, A, Laven, J, and Busschbach, J. Lifestyle treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: predictors of weight loss and dropout. Brain Behav. (2022) 12:e2621. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2621

64. Buscemi, J, Rybak, TM, Berlin, KS, Murphy, JG, and Raynor, HA. Impact of food craving and calorie intake on body mass index (BMI) changes during an 18-month behavioral weight loss trial. J Behav Med. (2017) 40:565–73. doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9824-4

65. Sterne, JAC, Savović, J, Page, MJ, Elbers, RG, Blencowe, NS, Boutron, I, et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 28:l4898.

66. Dalle Grave, R, Cuzzolaro, M, Calugi, S, Tomasi, F, Temperilli, F, Marchesini, G, et al. The effect of obesity management on body image in patients seeking treatment at medical centers. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2007) 15:2320–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.275

67. Armstrong, MJ, Mottershead, TA, Ronksley, PE, Sigal, RJ, Campbell, TS, and Hemmelgarn, BR. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. (2011) 12:709–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00892.x

68. Wilson, GT, and Schlam, TR. The transtheoretical model and motivational interviewing in the treatment of eating and weight disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. (2004) 24:361–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.003

69. Dalle Grave, R, Sartirana, M, and Calugi, S. Personalized cognitive-behavioural therapy for obesity (CBT-OB): theory, strategies and procedures. Biopsychosoc Med. (2020) 14:5. doi: 10.1186/s13030-020-00177-9

Keywords: dropout, predictive factors, cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive behavioral treatment, nutritional counseling, attrition, overweight, systematic review

Citation: Neri LdCL, Mariotti F, Guglielmetti M, Fiorini S, Tagliabue A and Ferraris C (2024) Dropout in cognitive behavioral treatment in adults living with overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Front. Nutr. 11:1250683. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1250683

Edited by:

Andrew Scholey, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jayanthi Raman, University of Technology Sydney, AustraliaAmy Harrison, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Neri, Mariotti, Guglielmetti, Fiorini, Tagliabue and Ferraris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cinzia Ferraris, Y2luemlhLmZlcnJhcmlzQHVuaXB2Lml0

†These authors share first authorship

Lenycia de Cassya Lopes Neri

Lenycia de Cassya Lopes Neri Francesca Mariotti2†

Francesca Mariotti2† Monica Guglielmetti

Monica Guglielmetti Simona Fiorini

Simona Fiorini Anna Tagliabue

Anna Tagliabue Cinzia Ferraris

Cinzia Ferraris