95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Nutr. , 20 November 2023

Sec. Sport and Exercise Nutrition

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1250567

This article is part of the Research Topic Nutritional Counseling for Lifestyle Modification View all 9 articles

Simona Fiorini1,2

Simona Fiorini1,2 Lenycia De Cassya Lopes Neri1

Lenycia De Cassya Lopes Neri1 Monica Guglielmetti1,2*

Monica Guglielmetti1,2* Elisa Pedrolini2

Elisa Pedrolini2 Anna Tagliabue1

Anna Tagliabue1 Paula A. Quatromoni3

Paula A. Quatromoni3 Cinzia Ferraris1,2

Cinzia Ferraris1,2Systematic review registration: Many studies report poor adherence to sports nutrition guidelines, but there is a lack of research on the effectiveness of nutrition education and behavior change interventions in athletes. Some studies among athletes demonstrate that nutrition education (NE), often wrongly confused with nutritional counseling (NC), alone is insufficient to result in behavior change. For this reason, a clear distinction between NC and NE is of paramount importance, both in terms of definition and application. NE is considered a formal process to improve a client’s knowledge about food and physical activity. NC is a supportive process delivered by a qualified professional who guides the client(s) to set priorities, establish goals, and create individualized action plans to facilitate behavior change. NC and NE can be delivered both to individuals and groups. To our knowledge, the efficacy of NC provided to athletes has not been comprehensively reviewed. The aim of this study was to investigate the current evidence on the use and efficacy of nutritional counseling within athletes. A systematic literature review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses method. The search was carried out in: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane Library between November 2022 and February 2023. Inclusion criteria: recreational and elite athletes; all ages; all genders; NC strategies. The risk of bias was assessed using the RoB 2.0 Cochrane tool. The quality of evidence checking was tested with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool system. From 2,438 records identified, 10 studies were included in this review, with athletes representing different levels of competition and type of sports. The most commonly applied behavior change theory was Cognitive Behavioral Theory. NC was delivered mainly by nutrition experts. The duration of the intervention ranged from 3 weeks to 5 years. Regarding the quality of the studies, the majority of articles reached more than 3 stars and lack of adequate randomization was the domain contributing to high risk of bias. NC interventions induced positive changes in nutrition knowledge and dietary intake consequently supporting individual performance. There is evidence of a positive behavioral impact when applying NC to athletes, with positive effects of NC also in athletes with eating disorders. Additional studies of sufficient rigor (i.e., randomized controlled trials) are needed to demonstrate the benefits of NC in athletes.

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42022374502.

Ensuring appropriate energy and nutrient intakes in athletes is critical in reaching and maintaining an optimal nutritional status, that supports peak performance and facilitates proper recovery after training and competition (1, 2). The nutritional requirements of athletes are influenced by numerous factors including gender, life stage, type of sport, training, phase of competition, environmental temperature, stress, high altitude exposure, physical injuries, phase of the menstrual cycle. For this reason, athletes’ dietary habits and diet composition should be customized according to their individual performance goals, preferences, and training phase (1). This work typically requires input from nutrition professionals known as registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) or accredited nutritionists, as terminology varies across the world.

Several authors report that many athletes do not meet their nutrition requirements (3) and do not have sufficient intakes of energy (4, 5), carbohydrates (6–8) and several micronutrients (5, 9). In contrast, some athletes seem to favor fat intake (8, 10, 11), which may be above the recommended levels (2), both considering the general sport requirements and the specific sport needs. The levels of inadequate intake are not surely known and can be influenced by the possible under-reporting (12–14) and are often based on the athletes’ limited nutrition knowledge (15–17). Moreover, athletes can adopt inappropriate and dysfunctional eating behaviors such as fasting, skipping meals, dieting, binge eating, vomiting, and use of laxatives and/or diet pills (18). Low sports nutrition knowledge and/or disordered eating behavior in the context of training and competing in sport can lead to the state of low energy availability (LEA) which is defined as the mismatch between energy intake and exercise energy expenditure (19). LEA in athletes may occur unintentionally (low awareness of the athletes’ nutritional needs), intentionally (attempts to optimize body composition for competition or to avoid weight gain during injury or illness), or compulsively (due to eating disorders [EDs] or disordered eating [DE] behavior) (20). One of the important health consequences of LEA is relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs), a syndrome characterized by a range of compromised physiological functions that negatively affect all body systems (i.e., metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, cardiovascular health, gastrointestinal function, and more) (21, 22). LEA and REDs undermine athletic performance and put the athlete’s physical and mental health at risk (23), making these conditions prime targets for prevention and intervention activities (24).

For all these reasons, the development and application of valid intervention strategies is necessary to support athletes and protect their health. Bentley and colleagues (25) conducted a systematic review of the main sport nutrition interventions (i.e., nutrition education, nutritional counseling, individual and group workshops, consultations) applied to athletes, reporting that the up-to-date evidence-based literature is limited in its ability to identify the most effective strategy for use with this population. In spite of this, several studies reported that nutritional counseling (NC) could represent an important strategy to modify dietary habits and behaviors of athletes (26–35) making this a worthwhile area of investigation.

NC is a supportive process, characterized by a collaborative relationship between the counselor and the client(s) to establish food, nutrition and physical activity priorities, goals, and action plans (36). It is included in the Nutrition Care Process (NCP) model as a specific nutrition intervention generally delivered by RDNs (36). NC may apply a variety of models belonging to behavior change theories. The more widely used, validated theories are cognitive behavioral theory (CBT), social cognitive theory (SCT), transtheoretical model (TM), health belief model (HBF), systemic therapy (ST), and Mindfulness. These tools and strategies may be applied by themselves or in combination with other theories (i.e., CBT and TM together) based on the patients’ goals, objectives, and personal skills (36, 37). NC can be delivered both to individuals and groups.

It is important to identify NC as an intervention that is distinct from nutrition education (NE). NE is a formal process to instruct or help a patient in a skill or to impart knowledge to help clients voluntarily manage or modify food, nutrition, and physical activity choices and behavior to maintain or improve health (36). Designed to improve nutrition knowledge, its aim is to support sound food choices at the level of the community or within a specific target population (38, 39). In contrast, NC is a dynamic, two-way interaction that actively involves the client, using their existing nutrition knowledge as a starting point to define and support key behavioral changes. NC typically occurs in the context of an ongoing professional relationship where the nutrition counselor works privately with the client through a series of individualized sessions. The role of the sport nutrition counselor is to help athletes identify, adopt, and sustain a customized fueling strategy that maximizes training, performance, recovery, and holistic well-being while applying resources that facilitate nutritionally adequate, balanced eating patterns and address potential obstacles and barriers that predispose athletes to LEA and REDs. There is a role for both NE and NC when working with athletes, but the most appropriate strategy is one that is individually selected by the nutrition professional informed by their appraisal of the nutritional assessment, nutrition-related diagnosis, client needs, abilities, and life circumstances (36).

The role of the sport nutrition counselor is to offer advice to people interested in solving various current problems that the client(s) may face, which comprehend, for example, the ones derived from the preparatory work for performance in sports (i.e., energy balance according to training duration, type and intensity), contests and competitions participation, to promote the personal image, proposing a new perspective that can lead to overcoming the perceived or objective difficulties (e.g., fear of gaining weight, inadequate nutritional intake, management of injuries, etc.) and to optimize sport performances (40).

To the best of our knowledge, no review articles evaluated the application of NC in athletes to date. This paper aims to systematically review the current evidence on the use of NC in athletes and to identify the specific outcomes investigated to characterize its impact.

This systematic review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method (41). The search was carried out in the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect and Cochrane Library. The languages allowed were English and Italian according to the capability of comprehension of the authors. No limits were considered according to the date of publication. Randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled observational studies, case study, case reports and case series, opinion articles, conference abstracts, theses, and dissertations were included. The study protocol was previously submitted on the PROSPERO platform and has its registration number CRD42022374502.

An electronic search was conducted with subject index terms “nutritional counseling” OR “nutrition counseling” OR “nutritional and eating education” OR “nutritional program” combined with the term “athletes” OR “sports” OR “performance” OR “athletic performance” OR “recreational athletes” OR “elite athletes.” Google Scholar was used to search gray literature and some references found in review articles were included manually. The populations of interest were recreational and elite athletes. We did not specify comparison conditions in our search because this was not included in the aim of the study which was simply to evaluate the use of NC, not necessarily compared to other strategies. The search strategy is illustrated in Table 1. Detailed criteria for study inclusion and exclusion are listed in Table 2.

The research and study selection was carried out by two authors (EP and LCLN) independently using the Rayyan software (42), following two steps. First, authors read the titles and abstracts; next, they evaluated the full articles selected in the previous stage, and included other relevant studies found in the reference lists of the selected articles. The decision to include an article was based on the PICOS strategy (Population (P): athletes; Intervention (I): nutritional counseling; Control (C): placebo, Outcome (O): adherence/compliance rates, nutrition knowledge, eating disorders, REDs, athlete triad, injuries, performance, body image, body dissatisfaction, low energy availability, osteopenia, amenorrhea, anemia and others; Study type (S): Randomized controlled trials, uncontrolled observational studies, case study, case reports and case series, opinion articles, conference abstracts, theses, and dissertations). When disagreement was found, a third author (SF) reviewed the full text articles to decide about inclusion.

Adherence, compliance rates, nutrition knowledge, eating disorders, REDs-S, athlete triad, injuries, performance, body image, body dissatisfaction, low energy availability, osteopenia, amenorrhea, anemia.

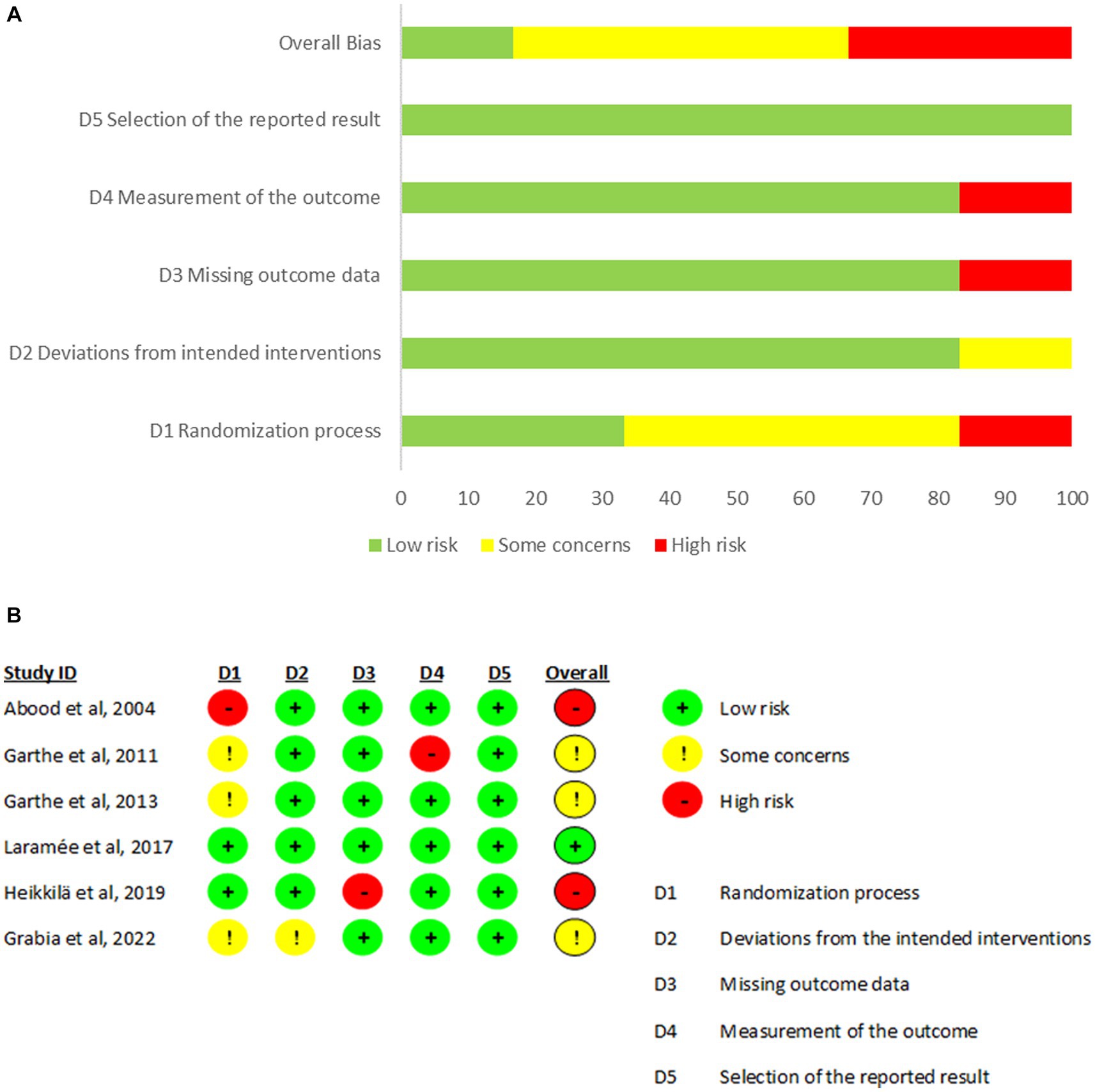

The risk of bias was also assessed by two authors, independently and blinded (EP and LCLN) using the RoB 2.0 Cochrane tool (43), checking 5 domains: (1) Randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome and (5) selection of the reported result. When disagreement was found, a third author (SF) decided. This tool was applied only to the clinical trials because of the adequacy of the instrument in this specific study design and the lack of control groups in the other reports.

The quality of evidence checking was tested for all articles with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool system (MMAT) (version 2018) (44) by two authors, independently and blinded (EP and LCLN). When disagreement was found, a third author (SF) decided. Data tables were constructed based on the articles’ details.

A total of 2,438 records were identified through database searches. After removal of duplicates, 2,280 articles remained. After first screening by title and abstract, 29 records were sought for retrieval. The indications for excluding 2,251 articles are shown in Figure 1. Eighteen articles were retrieved. Upon reading, eight articles were excluded because they did not use nutritional counseling strategies. Ten studies were included in this review (Figure 1).

The selected studies are summarized in Table 3. All were published between 2004 and 2022. Four studies were conducted in the United States (26, 33–35), two in Norway (27, 28), one in Poland (29), one in Algeria (32), one in Canada (31), and one in Finland (30).

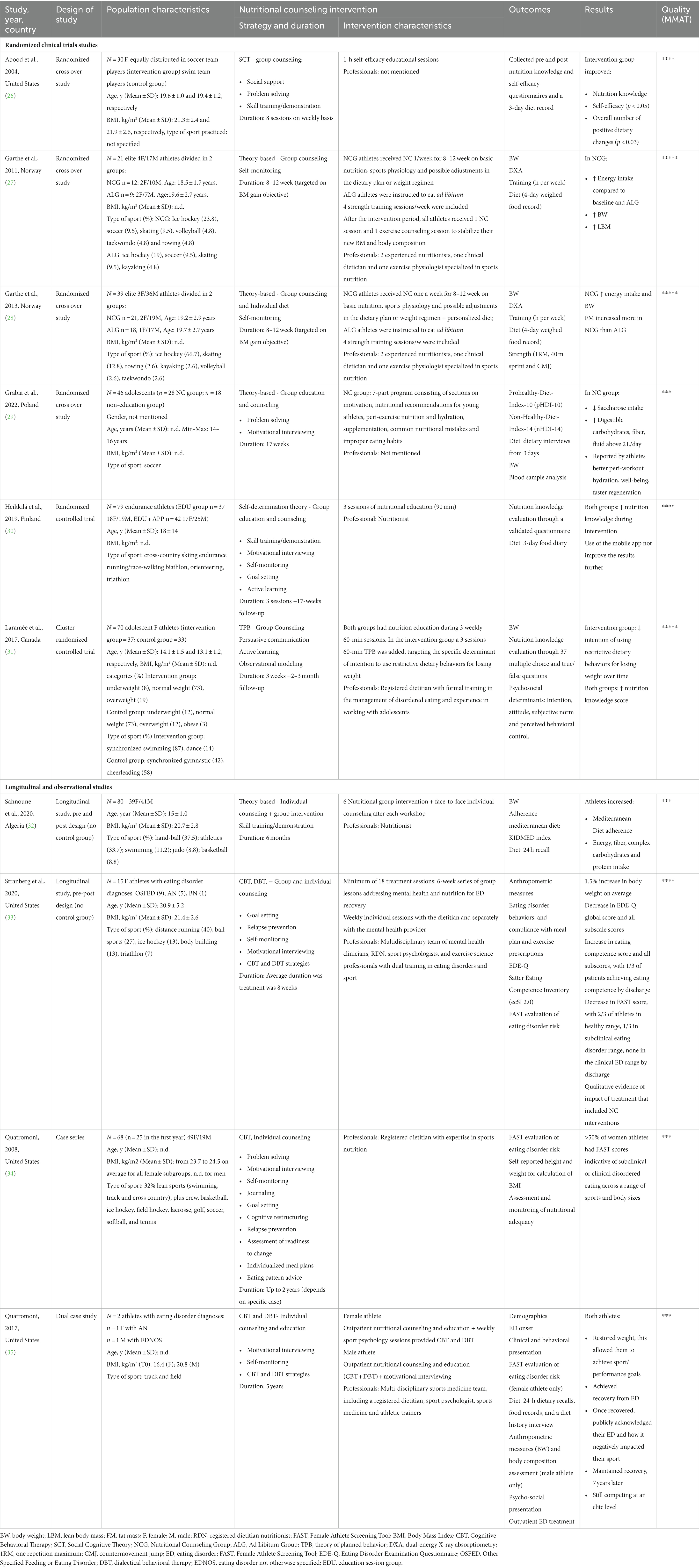

Table 3. Details of included articles: population characteristics, type of intervention, results and quality of evidence (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool system [MMAT]).

A variety of study designs are represented in this sample. There were four randomized cross-over studies (26–29), one randomized controlled trial (30), one cluster randomized controlled trial (31), two longitudinal studies (32, 33), one case series (34), and one dual case study (35). No studies from grey literature were included.

The studies reported on a combined total of 450 participants, mainly females (60.9%). One article did not report the athletes’ gender. Sample sizes ranged from two (35) to 80 participants (32). Three studies (34–36) involved athletes with eating disorders.

Participants were adolescent athletes, college students, elite athletes (qualified for national teams or members of a recruiting squad), and national or international level athletes. The sports represented in the study samples included: soccer, swimming, track and cross country, crew, basketball, ice hockey, field hockey, lacrosse, tennis, golf, rowing, volleyball, softball, taekwondo, skating, kayaking, synchronized swimming, gymnastics, dance, cheerleading, cross-country skiing, endurance running/race-walking, biathlon, orienteering, triathlon, bodybuilding, athletics, judo.

Six studies (26–31) delivered group counseling, one study employed both group and individual counseling (33), and three studies used only individual counseling (32, 34, 35). The type of NC delivered was specified only in 6 articles, with three of them using multiple strategies (33–35). The most commonly used was CBT (33–35), combined with Dialectical Behavioral Therapy in two studies (33, 35). Abood et al. delivered nutritional counseling based on social cognitive theory using self-efficacy educational sessions (26). Laramée et al. focused on behavior change using the theory of planned behaviour targeting the specific determinant of intention to use restrictive dietary behaviors for losing weight (31). Grabia et al. dedicated one session of the program to motivation (29).

More specifically, 15 different strategies were applied across the interventions, described in Table 3. The most frequent strategies used were ‘motivational interviewing’ (29, 30, 33–35) and “self-monitoring” (27, 28, 30, 33–35), followed by “problem-solving” (26, 29, 34), “goal setting” (30, 33, 34) and “skills training” (26, 30, 32). Quatromoni used a combination of ten different strategies across a sample of athletes (34).

Eight studies reported the topics of intervention, such as caloric intake and energy expenditure, carbohydrates, fats and proteins, fluids, calcium, iron, and zinc (n = 6), dietary challenges such as eating on the road (n = 4), restrictive dietary behaviors and disordered eating (n = 4), supplement use (n = 2), Mediterranean Diet pyramid, typical athlete meal, healthy food recipes (n = 1), nutritional recommendations for young athletes (n = 1), peri-exercise nutrition and hydration (n = 2), sports physiology and possible adjustments in the dietary plan for weight regimen (n = 2), fueling for sport and for life, eating competence, body esteem, recovery skills, resilience (n = 1). Some topics were common in the different studies, so some themes are repeated in the count.

The duration of the intervention and/or follow-up was highly varied. The most brief intervention lasted 3 weeks (31) and the longest had a duration of 5 years (35). Only three studies reported the duration of each session. In the studies by Abood et al. (26) and Laramée et al. (31), the sessions were 60 min long, and in the study by Heikkilä et al. (30), workshops duration was 90 min.

In the reviewed studies, nutritional counseling was delivered by a RDN (31, 34), a multidisciplinary team in which an RDN was involved (33, 35), a nutritionist (30, 32), or two experienced nutritionists (one clinical dietitian and one exercise physiologist specialized in sports nutrition) (27, 28). Two studies did not report the qualifications or discipline of the facilitator (26, 29).

The possible outcomes were categorized into Questionnaires results and Nutritional Counseling Efficacy, which is more specifically divided in (1) nutrition knowledge, (2) dietary intake and (3) remission from eating disorders.

Three studies (26, 30, 31) administered nutrition knowledge questionnaires to evaluate differences between pre- and post-intervention scores. Three studies (33–35) administered the Female Athlete Screening Tool (FAST) that screens for athlete-specific eating disorder risk (45). Stranberg et al. (33) also used the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) that evaluates the frequency and severity of eating disorder behavior (46) and the Satter Eating Competence Inventory (ecSI 2.0) that assesses eating competence, which includes rebuilding a healthy relationship with food, developing skills for meal planning and reliably feeding oneself and applying informed intuitive eating (47). Abood et al. (26) used a self-efficacy questionnaire and Laramée et al. (31) used a questionnaire of psychosocial determinants of intention to use restrictive dietary behaviors for losing weight. Anthropometric data were collected in all 10 studies. Body composition was assessed in three studies (27, 28, 34).

Seven studies assessed dietary intake and nutritional adequacy, using either a 3-day food record (26, 30, 31), a 4-day weighed food record (27, 28), a 24-h dietary recall (32), a combination of tools for dietary assessment and monitoring (34, 35), or a questionnaire that informed the calculation of the ProHealthy-Diet-Index-10 (pHDI-10) and the Non-Healthy-Diet-Index-14 (nHDI-14) (29). An individualized meal plan was part of the intervention in five studies (27, 28, 33–35).

Three studies (26, 30, 31) showed an improvement in nutrition knowledge in athletes to whom nutritional counseling was delivered. Laramée et al. (31) highlighted an improvement in nutrition knowledge in both control and intervention groups, but only in the intervention group was there a decrease in the intention of using restrictive dietary behaviors for losing weight.

Results of three studies (26, 29, 32) showed some measurable changes in dietary intake. Athletes increased adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and energy, fiber, carbohydrate and protein intake (32), increased fluid intake above 2 L/day, and decreased sugar intake (29). In the study by Abood et al. (26), the nutritional counseling group significantly improved self-efficacy (p < 0.05) and achieved an overall higher number of positive dietary changes (p < 0.03) compared to those in the control group who did not receive any treatment. Two studies (27, 28) showed an increased energy intake and consequently, increased body weight, in the Nutritional Counseling Group (NCG) compared to baseline and compared to the Ad Libitum Group (ALG) that received no nutritional counseling intervention. In both studies, athletes in the NCG increased fat mass and lean body mass to a greater extent than athletes in the ALG.

From a longitudinal observational study of 15 college female athletes who underwent nutritional counseling in the setting of an intensive outpatient program for the treatment of eating disorders in sport, Stranberg et al. (33) reported a decrease in the FAST score where two thirds of athletes scored in the healthy range and only one-third scored in the subclinical eating disorder range at discharge. This was in contrast to only 32% in the healthy range, 26% subclinical, and 42% screening positive for a clinical ED on admission. Further evidence of remission from the eating disorder and achieving normalized eating patterns was provided by this study where a measurable decrease in EDE-Q scores and an increase in eating competence scores was shown as a consequence of the intervention. While only 10% of athletes were competent eaters on admission, 33% were on discharge. More than half of admissions resulted in weight gain (58%). The dual case study that applied NC to athletes with eating disorders in the outpatient setting (35) reported the achievement of weight restoration (evidence of nutritional adequacy) and recovery from the eating disorder, with recovery maintained 7 years later after treatment by a multidisciplinary team that included a registered dietitian.

The quality of evidence checking was tested using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool system (MMAT) (version 2018) (44). The results are reported in Table 3. Four studies reached three stars (29, 32, 34, 36), three studies (26, 30, 33) were evaluated with four stars, and three studies earned the maximum five stars (27, 28, 31).

The risk of bias was assessed using the RoB 2.0 Cochrane tool (Figure 2) (43) according to the study procedures for six studies (26–31). Overall results showed one study at low risk of bias (31), three studies with some concern (27–29), and two studies at high risk of bias (26, 30). The randomization process was the domain at higher risk of bias. For overall studies, the domain ‘selection of the reported results’ was at low risk of bias. Domains 2, 3, and 4 (deviations from the intended intervention, missing outcome data, measurements of the outcome) obtained a low-to-moderate risk of bias score for all studies except for Garthe et al. (27) and Heikkila et al. (30) for domains 4 and 3, respectively, where the risk was high.

Figure 2. Results of risk of bias analysis. (A) Percentage of risk of bias of each domain in all included studies. (B) Description of each domain of bias according to studies included (43).

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that evaluates the delivery of nutritional counseling to athletes and summarizes its potential effectiveness. Each of the ten studies reviewed reported some beneficial changes in the diets or eating behaviors of athletes as a consequence of nutritional counseling interventions. The main results showed that NC interventions induced positive changes in nutrition knowledge, dietary intake (quality and/or adequacy) consequently affecting athletic performance, and recovery from eating disorders. While more research is needed on this topic, these initial observations support the inclusion of nutrition professionals in sport environments to make NC interventions accessible and impactful.

Across the ten studies included in this review, there was a substantial amount of heterogeneity in key areas that affect the interpretation of this evidence. Authors used a variety of NC strategies grounded in different behavioral change theories. The duration of the counseling interactions ranged from weeks to years, and in some instances was determined by individualized needs such as treatment for REDs or an eating disorder. Most of the intervention plans delivered group counseling, some combined group and individual counseling strategies, and others only involved individual counseling. Finally, population characteristics varied widely. Samples more often included females, but some studies did include males and they involved athletes of different ages and levels of competition, and the types of sports practiced were quite varied. While this gives some sense of comprehensive diversity and inclusion, it is somewhat challenging to draw definitive conclusions.

In spite of the heterogeneity in this literature, all of the studies reported outcomes that can be interpreted as desirable in terms of athlete nutritional status and well-being. In particular, the case report by Quatromoni et al. (35) described in detail the outpatient treatment of two collegiate track athletes with diagnosed eating disorders. During the NC sessions, the dietitian used strategies based on CBT, DBT, and MI. Both athletes achieved weight restoration and recovered from anorexia and ED reaching sport performance goals, and maintaining recovery years out from treatment. Stranberg et al. (33) reported similar results in a sample of 15 female athletes with eating disorder diagnoses. This latter paper (33) is the first one that documents the low level of eating competence in athletes treated for EDs, and shows how NC interventions that target personal feeding skills and eating behaviors are relevant, effective, and aligned with ED recovery. Similarly, the study conducted by Laramée et al. (31) demonstrated a decrease in restrictive eating behavior in the group of athletes exposed to NC.

Other studies documented important positive modifications in terms of nutrition knowledge and dietary intake among athletes provided NC from nutrition professionals (27). It is well established that a balanced and adequate diet plays an important role in maintaining health, allowing athletes to perform at a high level, and recover from the stress of training and competition more efficiently (1, 48). To apply the principles of sports nutrition, basic knowledge and understanding of nutrition are necessary; however, knowledge does not necessarily translate to behavior and it may not be sufficient to allow athletes to thrive and reach their full potential. The literature on NE is growing (49–51), intending to support optimal eating patterns within the community or a specific target population such as athletes. The addition of NC on top of NE appears essential. In fact, recent research has shown that NE programs may be less effective at inducing positive dietary changes (17). Otherwise NC combines information with strategies to achieve a behavior change based on individual characteristics, beliefs, and goals, setting it apart as its own worthy intervention approach.

Moreover, the sports environment often influences athletes’ eating behaviors in ways that undermine nutritional adequacy and sabotage well-being and performance (obtaining a sport-specific body type, academic stress, team culture, coach and family expectations, and social perceptions or norms) (52, 53). Some types of sport have been shown to be more related to the development of disordered eating and ED, specifically track, cross-country, cycling, swimming, gymnastics, dance, figure skating, and judo (18), whereas other literature (54, 55) suggests that ED in sport are more widespread, do not discriminate by sport, gender or body type, and after quite under-reported, under-diagnosed and under-treated. Pressure from athletes’ teammates or training groups may also play an integral role in the development and maintenance of athletes’ eating/exercise psychopathology with both direct comments about weight and body shape noted as contributing factors, and indirect influences from peer modeling and social media content playing a role (54, 55).

For all of these reasons, an effective approach is needed to support athletes’ nutritional well-being given its important interrelationship with physical health, mental health, and sports performance. Evidenced by the studies included in this review, nutritional counseling could represent a functional strategy in this pursuit. From our review it can be seen that CBT has been the most widely used NC theory. Furthermore, the most used strategies were motivational interviewing and self-monitoring, although the importance of a combination of different strategies has emerged. There were some limitations in this systematic review. Aside from the heterogeneity of the athlete samples and study designs used, there was a lack of specification of the type of NC techniques used in some studies. These factors prevent us from addressing a more detailed hypothesis on whether (and which) specific NC theories or strategies could be more suitable or impactful, in general or for a specific group of athletes. Moreover, nutritional counseling was not a keyword recognized in MESH terminology. This may contribute to a possible under-estimation of the actual number of studies to be evaluated if some were missed for this reason. Some reports constitute observations from clinical practice and, while more detailed in nature and certainly important to guide practice when research on a topic is limited, these reports lack the rigor of randomized controlled trials designed specifically to test hypotheses about treatment outcomes from interventions like NC. The four studies that were not clinical trials were of moderate quality, and they are naturally subject to more potential risk of bias than the RCTs. Although each of the six RCTs had a low risk of bias in the majority of the domains considered, only one trial had an overall low risk of bias.

This review is also supported by some strengths. First, scientific literature on the topic of NC in athletes is scarce, so this article provides the opportunity for critical thinking on this topic and a roadmap for future research. Second, this line of research strictly differentiates nutritional counseling from food education interventions, demonstrating the added value and the unique role that nutrition professionals bring to the sports environment. Actually, RDNs who specialize in sports and human performance nutrition (i.e., sports RDNs) are the preferred providers of NC interventions because of their extensive and varied training experiences that include clinical nutrition and medical nutrition therapy (MNT), education and behavioral counseling, food service and culinary nutrition, exercise physiology, and evidence-based nutrition guidance for physical performance (56). Advanced training that allows the RDN to engage in screening, assessment, treatment, and prevention of REDs and eating disorders in sport is evidenced in this review. Considering the small yet emerging literature on this topic, almost half of the studies reviewed had a minimum quality rating of four stars using the MMAT method.

Nutritional counseling induces positive, measurable behavioral effects in athletes, improving nutrition knowledge, fostering the adoption of adequate eating patterns, and supporting recovery from REDs and ED in sport. There is, however, a lack of homogeneous research, in terms of design, population and methods, involving nutritional counseling provided to athletes which makes it difficult to make evidence-based conclusions about its efficacy to improve dietary intake, eating behavior, and nutritional risk in this specific population. More studies are needed to better understand the importance of nutritional counseling in athletes given the unique risks and consequences associated with imbalanced nutrition and nutrition misinformation affecting eating behaviors. Randomized controlled trials of sufficient size and heterogeneity, including all genders and a variety of sports are needed. As well, future NC interventions should investigate theory-based counseling methods tailored according to factors such as type of sport, level of competition, and age.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

PQ and CF: conceptualization. SF, PQ, EP, LDCLN, CF, and MG: methodology. SF, EP, LDCLN, MG, and CF: investigation. SF, EP, and LDCLN: data curation. SF, MG, and CF: writing – original draft preparation. SF, EP, LDCLN, PQ, MG, CF, and AT: writing – review and editing. CF: supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Project funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), mission 4 component 2 investment 1.3 - call for tender no. 341 of 15 March 2022 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU; award number: project code PE00000003, concession decree no. 1550 of 11 October 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP F13C22001210007, project title “ON Foods - Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, Safety and Security – Working ON Foods.”

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Thomas, DT, Erdman, KA, and Burke, LM. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics, dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2016) 116:501–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.006

2. Kerksick, CM, Wilborn, CD, Roberts, MD, Smith-Ryan, A, Kleiner, SM, Jäger, R, et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2018) 15:38. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y

3. García-Rovés, PM, García-Zapico, P, Patterson, AM, and Iglesias-Gutiérrez, E. Nutrient intake and food habits of soccer players: analyzing the correlates of eating practice. Nutrients. 6:2697–717. doi: 10.3390/nu6072697

4. Baranauskas, M, Stukas, R, Tubelis, L, Žagminas, K, Šurkienė, G, Švedas, E, et al. Nutritional habits among high-performance endurance athletes. Medicina (Kaunas). (2015) 51:351–62. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2015.11.004

5. Jenner, SL, Trakman, G, Coutts, A, Kempton, T, Ryan, S, Forsyth, A, et al. Dietary intake of professional Australian football athletes surrounding body composition assessment. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2018) 15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0248-5

6. Martin, L, Lambeth, A, and Scott, D. Nutritional practices of national female soccer players: analysis and recommendations. J Sports Sci Med. (2006) 5:130–7.

7. Clark, M, Reed, DB, Crouse, SF, and Armstrong, RB. Pre- and post-season dietary intake, body composition, and performance indices of NCAA division I female soccer players. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2003) 13:303–19. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.13.3.303

8. Abbey, EL, Wright, CJ, and Kirkpatrick, CM. Nutrition practices and knowledge among NCAA division III football players. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2017) 19:13. doi: 10.1186/s12970-017-0170-2

9. Keith, RE, O’Keeffe, KA, Alt, LA, and Young, KL. Dietary status of trained female cyclists. J Am Diet Assoc. (1989) 89:1620–3.

10. Iglesias-Gutiérrez, E, García, A, García-Zapico, P, Pérez-Landaluce, J, Patterson, AM, and García-Rovés, PM. Is there a relationship between the playing position of soccer players and their food and macronutrient intake? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2012) 37:225–32. doi: 10.1139/h11-152

11. Ruiz, F, Irazusta, A, Gil, S, Irazusta, J, Casis, L, and Gil, J. Nutritional intake in soccer players of different ages. J Sports Sci. (2005) 23:235–42. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001730160

12. Ferraris, C, Guglielmetti, M, Trentani, C, and Tagliabue, A. Assessment of dietary under-reporting in Italian college team sport athletes. Nutrients. (2019) 11:1391. doi: 10.3390/nu11061391

13. Kobe, H, Kržišnik, C, and Mis, NF. Under- and over-reporting of energy intake in slovenian adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2012) 44:574–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.02.015

14. Ouellette, CD, Yang, M, Wang, Y, Yu, C, Fernandez, ML, Rodriguez, NR, et al. Assessment of nutrient adequacy with supplement use in a sample of healthy college students. J Am Coll Nutr. (2012) 31:301–10. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2012.10720424

15. Argôlo, D, Borges, J, Cavalcante, A, Silva, G, Maia, S, Moraes, A, et al. Poor dietary intake and low nutritional knowledge in adolescent and adult competitive athletes: a warning to table tennis players. Nutr Hosp. (2018) 35:1124–30. doi: 10.20960/nh.1793

16. Condo, D, Lohman, R, Kelly, M, and Carr, A. Nutritional intake, sports nutrition knowledge and energy availability in female Australian rules football players. Nutrients. (2019) 11:971. doi: 10.3390/nu11050971

17. Spronk, I, Kullen, C, Burdon, C, and O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br J Nutr. (2014) 111:1713–26. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514000087

18. Mancine, RP, Gusfa, DW, Moshrefi, A, and Kennedy, SF. Prevalence of disordered eating in athletes categorized by emphasis on leanness and activity type – a systematic review. J Eat Disord. (2020) 29:47. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00323-2

19. Williams, NI, Statuta, SM, and Austin, A. Female athlete triad: future directions for energy availability and eating disorder research and practice. Clin Sports Med. (2017) 36:671–86. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2017.05.003

20. Melin, AK, Heikura, IA, Tenforde, A, and Mountjoy, M. Energy availability in athletics: health, performance, and physique. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2019) 29:152–64. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0201

21. Mountjoy, M, Sundgot-Borgen, J, Burke, L, Carter, S, Constantini, N, Lebrun, C, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the female athlete triad--relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med. (2014) 48:491. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502

22. Mountjoy, M, Ackerman, KE, Bailey, DM, Burke, LM, Constantini, N, Hackney, AC, et al. 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs). Br J Sports Med. (2023) 57:1073–97. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994

23. Mountjoy, M, Sundgot-Borgen, JK, Burke, LM, Ackerman, KE, Blauwet, C, Constantini, N, et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med. (2018) 52:687–97. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099193

24. Torstveit, MK, Ackerman, KE, Constantini, N, Holtzman, B, Koehler, K, Mountjoy, ML, et al. Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs): a narrative review by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on REDs. Br J Sports Med. (2023) 57:1119–26. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2023-106932

25. Bentley, MRN, Mitchell, N, and Backhouse, SH. Sports nutrition interventions: a systematic review of behavioural strategies used to promote dietary behaviour change in athletes. Appetite. (2020) 1:104645. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104645

26. Abood, DA, Black, DR, and Birnbaum, RD. Nutrition education intervention for college female athletes. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2004) 36:135–9. doi: 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60150-4

27. Garthe, I, Raastad, T, and Sundgot-Borgen, J. Long-term effect of nutritional counselling on desired gain in body mass and lean body mass in elite athletes. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:547–54. doi: 10.1139/h11-051

28. Garthe, I, Raastad, T, Refsnes, PE, and Sundgot-Borgen, J. Effect of nutritional intervention on body composition and performance in elite athletes. Eur J Sport Sci. (2013) 13:295–303. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2011.643923

29. Grabia, M, Markiewicz-Żukowska, R, Bielecka, J, Puścion-Jakubik, A, and Socha, K. Effects of dietary intervention and education on selected biochemical parameters and nutritional habits of young soccer players. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3681. doi: 10.3390/nu14183681

30. Heikkilä, M, Lehtovirta, M, Autio, O, Fogelholm, M, and Valve, R. The impact of nutrition education intervention with and without a Mobile phone application on nutrition knowledge among Young endurance athletes. Nutrients. (2019) 11:2249. doi: 10.3390/nu11092249

31. Laramée, C, Drapeau, V, Valois, P, Goulet, C, Jacob, R, Provencher, V, et al. Evaluation of a theory-based intervention aimed at reducing intention to use restrictive dietary behaviors among adolescent female athletes. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2017) 49:497–504.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.03.009

32. Sahnoune, R, and Bouchenak, M. Nutritional intervention promoting Mediterranean diet improves dietary intake and enhances score adherence in adolescent athletes. Med J Nutrition Metab. (2020) 13:237–53. doi: 10.3233/MNM-200414

33. Stranberg, M, Slager, E, Spital, D, Coia, C, and Quatromoni, PA. Athlete-specific treatment for eating disorders: initial findings from the Walden GOALS program. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2020) 120:183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.07.019

34. Quatromoni, PA . Clinical observations from nutrition services in college athletics. J Am Diet Assoc. (2008) 108:689–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.008

35. Quatromoni, PA . A tale of two runners: a case report of athletes’ experiences with eating disorders in college. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2017) 117:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.032

36. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Eat Right . Nutrition terminology: reference manual. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2022)

37. Spahn, JM, Reeves, RS, Keim, KS, Laquatra, I, Kellogg, M, Jortberg, B, et al. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. (2010) 110:879–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.021

38. Morgan, PJ, Warren, JM, Lubans, DR, Saunders, KL, Quick, GI, and Collins, CE. The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutr. (2010) 13:1931–40. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000959

39. Heaney, S, O’Connor, H, Michael, S, Gifford, J, and Naughton, G. Nutrition knowledge in athletes: a systematic review. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2011) 21:248–61. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.21.3.248

40. Bădău, D . Sport Counseling – A New Approach to Improve the Performances Annals of Dunarea de Jos University of Galati Fascicle (2014).

41. Page, MJ, JE, MK, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 371:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

42. Ouzzani, M, Hammady, H, Fedorowicz, Z, and Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

43. Sterne, JAC, Savović, J, Page, MJ, Elbers, RG, Blencowe, NS, Boutron, I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 28:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

44. Hong, QN, Fàbregues, S, Bartlett, G, Boardman, F, Cargo, M, Dagenais, P, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. EFI. (2018) 34:285–91. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

45. McNulty, KY, Adams, CH, Anderson, JM, and Affenito, SG. Development and validation of a screening tool to identify eating disorders in female athletes. J Am Diet Assoc. (2001) 101:886–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00218-8

46. Mond, JM, Hay, PJ, Rodgers, B, Owen, C, and Beumont, PJV. Validity of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther. (2004) 42:551–67. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X

47. Lohse, B, Satter, E, Horacek, T, Gebreselassie, T, and Oakland, MJ. Measuring eating competence: psychometric properties and validity of the ecSatter inventory. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2007) 39:S154–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.371

48. Burke, L, Deakin, V, and Minehan, M. Clinical Sports Nutrition. 6th ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill Education (2021).

49. Sánchez-Díaz, S, Yanci, J, Castillo, D, Scanlan, AT, and Raya-González, J. Effects of nutrition education interventions in team sport players. A systematic review. Nutrients. (2020) 12. doi: 10.3390/nu12123664

50. Scazzocchio, B, Varì, R, d’Amore, A, Chiarotti, F, Del Papa, S, Silenzi, A, et al. Promoting health and food literacy through nutrition education at schools: the Italian experience with MaestraNatura program. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1547. doi: 10.3390/nu13051547

51. Aguilo, A, Lozano, L, Tauler, P, Nafría, M, Colom, M, and Martínez, S. Nutritional status and implementation of a nutritional education program in young female artistic gymnasts. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1399. doi: 10.3390/nu13051399

52. Arthur-Cameselle, J, Sossin, K, and Quatromoni, P. A qualitative analysis of factors related to eating disorder onset in female collegiate athletes and non-athletes. Eat Disord. (2017) 25:199–215. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2016.1258940

53. Quinn, MA, and Robinson, S. College athletes under pressure: eating disorders among female track and field athletes. Am Econ. (2020) 65:232–43. doi: 10.1177/0569434520938709

54. Scott, CL, Haycraft, E, and Plateau, CR. The influence of social networks within sports teams on athletes’ eating and exercise psychopathology: a longitudinal study. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2020) 52:101786. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101786

55. Scott, CL, Haycraft, E, and Plateau, CR. The impact of critical comments from teammates on athletes’ eating and exercise psychopathology. Body Image. (2022) 43:170–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.08.013

56. Lambert, V, Carbuhn, A, Culp, A, Ketterly, J, Twombley, B, and White, D. Interassociation consensus statement on sports nutrition models for the provision of nutrition services from registered dietitian nutritionists in collegiate athletics. J Athl Train. (2022) 57:717–32. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0157.22

Keywords: nutritional counseling, athletes, nutrition knowledge, sport nutrition, nutritional strategies

Citation: Fiorini S, Neri LDCL, Guglielmetti M, Pedrolini E, Tagliabue A, Quatromoni PA and Ferraris C (2023) Nutritional counseling in athletes: a systematic review. Front. Nutr. 10:1250567. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1250567

Received: 30 June 2023; Accepted: 06 November 2023;

Published: 20 November 2023.

Edited by:

Edurne Simón, University of the Basque Country, SpainReviewed by:

Débora Ribeiro Orlando, Universidade Federal de Lavras, BrazilCopyright © 2023 Fiorini, Neri, Guglielmetti, Pedrolini, Tagliabue, Quatromoni and Ferraris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Monica Guglielmetti, bW9uaWNhLmd1Z2xpZWxtZXR0aUB1bmlwdi5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.