- College of Tourism & Landscape Architecture, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, China

In the food industry space, Netflix foods have exploded onto the Internet on the back of social media and many consumers are paying a premium for them. So what are the motives that may inspire consumers’ willingness to pay premium? In this paper, from the perspective of anchor, an external cue, a questionnaire survey was conducted with 275 respondents and analyzed using SPSS software. The results show that anchor characteristics (interactivity, professionalism and popularity) can influence consumers’ perceived value and increase their premium purchase intention. Perceived value mediates the relationship between anchor characteristics and willingness to pay a premium. Limited-time limited-quantity positively moderated the relationship between perceived value and premium purchase intention. The results reveal the key role of anchors in consumers’ decision-making process of buying Netflix food at a premium, and provide a theoretical basis for enterprises to select and cultivate anchors for product promotion.

1. Introduction

With the development of social media, the development pattern of the live broadcasting industry has gradually stabilized, and the integration of the netroots economy and social media has also shown strong resilience, and has been deeply integrated into the social production and life (1). In the field of food industry, Netflix food has become a newcomer in the food industry by relying on social media to explode all over the Internet (2). These foods often have unique packaging, ingredients and taste, and are welcomed and sought after by consumers. At the same time, along with the change of public consumption concepts and upgrading of consumer demand, consumers are willing to pay a premium for their favorite products (3). For Netflix food, even if the price is often higher than the actual value, it still attracts most consumers to pay for it (4). What makes consumers willing to pay a premium? Previous studies have found that consumers’ motivation to pay a premium is influenced by psychological factors (5). For example, consumers are willing to pay a premium for high-quality products due to product safety motives; consumers with a preference for place of origin are more likely to pay a premium for products with geographic landmarks (6). In addition, the external environment also influences consumers’ premium purchase decisions. For special products such as Netflix food, it is more difficult for consumers to understand their special product attributes through features such as product appearance, which prompts them to rely more on the live (external) environment to make purchasing judgments (7).

In the live shopping process, the anchor, as an opinion leader, plays the role of a bridge between the product and the consumer, which largely influences the consumer’s decision-making behavior (8). Therefore, enterprises pay more attention to the training of the anchor team, according to the target audience of the product or service to choose to match the different characteristics of the anchor to promote, in order to attract more attention from consumers (9). Take “EASTBUY” as an example, the agricultural products sold in this live broadcast are of good quality and higher price, and the anchor Dong Yuhui sold 320 million in 1 week with his own efforts. The anchor is extremely professional and knowledgeable, for the audience to create a “knowledge + entertainment + selling” of the new consumer experience and the high-priced agricultural products were purchased by consumers at a premium (10). Does the characteristics of the anchor affect consumers’ willingness to purchase food at a premium? Previous scholars have not focused on premium-priced products, although they have confirmed that anchor characteristics have an impact on consumers’ willingness to purchase (11). And, while previous studies have found that consumers are willing to pay a premium for foods with labels such as “green” and “organic,” or are influenced by personal factors (e.g., personal consumption preferences, personal consumption levels, etc.) to purchase high-priced foods (12), however, it has not focused on the role of the anchor as an external cue. Therefore, this paper attempts to explore the impact of anchor characteristics on consumers’ willingness to purchase food at a premium, starting with the external environment as a key factor influencing consumers’ willingness to pay at a premium. Furthermore, it has been suggested that e-commerce anchor characteristics influence consumers’ value perceptions first and then online purchase intentions (13). For food products, consumers rely on opinion leaders to make decisions, and when anchors are more interactive and professional, they enhance consumers’ trust and value perceptions of products. Meanwhile, product safety issues are frequent in the food sector, and buying products recommended by high-popularity anchors is more secure and affects consumers’ perceived value (14). Therefore, this paper will explore the mediating role of perceived value. Considering that companies often use limited-time limited-quantity marketing stimuli in product promotion, for example, the brand will set a specific time period for the sale of Netflix or limit the number of Netflix available to inspire a sense of urgency and scarcity among consumers. This sense of scarcity may have an impact on consumers’ perceived value (15), which in turn affects their purchasing decisions, so this paper introduces limited-time limited-quantity as a moderating variable.

Given the situational context of Netflix food in the social media era, it is necessary to investigate and fully understand consumer responses to Netflix food. And previous studies have not focused on the impact of the important role of the anchor, an external cue, on consumer premium payment in the online environment. Therefore, this study will explore the impact of anchor characteristics (interactivity, professionalism, and popularity) on consumers’ premium purchase intention, and further identify the intrinsic mechanism of action and boundary conditions of this process, so as to provide valuable insights for companies to choose the right anchors.

2. Literature review and research hypotheses

2.1. The SOR theory

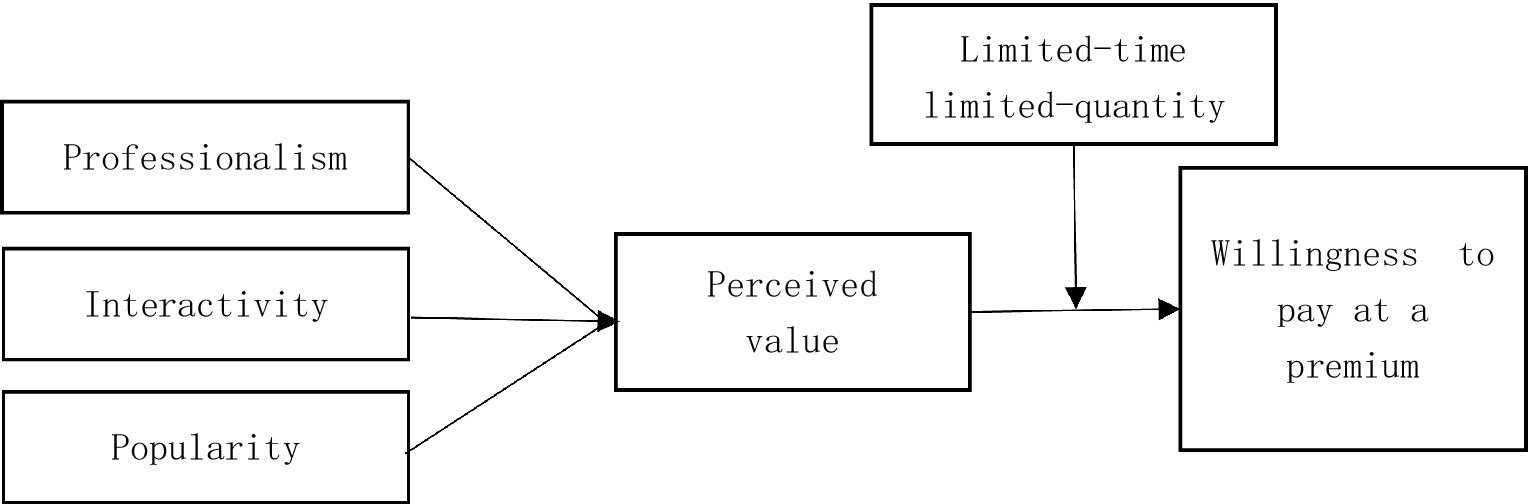

The “Stimulus-Organic-Response” (SOR) model in marketing suggests that various external stimuli influence consumers’ physiological and psychological behavior by affecting their purchase behavior (16). In recent years, this theory has been widely applied to the study of online consumer behavior, and many scholars have explored the factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention from different perspectives based on this theory. Using the SOR theory, some scholars point out that the interactivity, professionalism and charisma of e-commerce anchors significantly affect consumers’ purchase intention based on the characteristics of e-commerce anchors’ opinion leaders (5). Based on the SOR model, other scholars have analyzed the influence mechanism of Internet Word of Mouth (IWOM) on college students’ willingness to purchase online (17). Based on the SOR model, some scholars have explored the influence of online reviews on consumers’ impulse purchase decisions (18). Given the importance of the SOR model in explaining the relationship between external factors and consumer responses, this paper designs a research framework on how anchors influence consumers to make food premium purchase decisions, investigates anchor characteristics (interactivity, professionalism, and popularity) as external stimuli, reflects state changes in emotion and cognition through perceived value, and further extends the SOR model by adding the moderating variable of limited-time limited-quantity.

2.2. Food premium payment

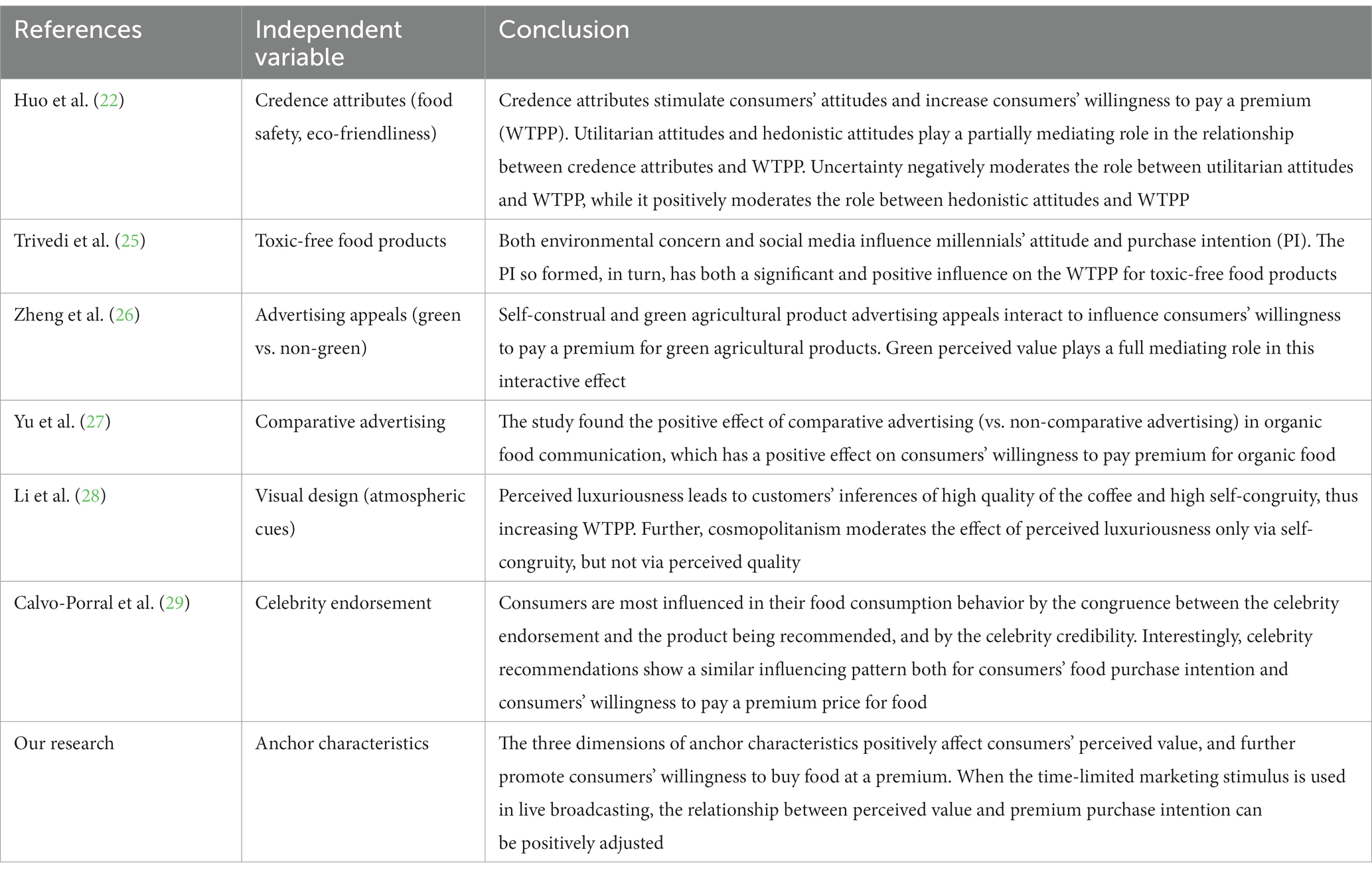

The issue of consumers’ willingness to pay has become a hot topic of academic attention in recent years. A review of previous studies reveals that most scholars have explored the motivations and reasons for paying a food premium from the perspective of the food itself or consumers’ personal preferences. Lang and Rodrigues (19) suggest that consumers are willing to pay a premium for quality food from an environmental and health perspective. Consumers are willing to pay a premium for foods with labels such as “organic” and “green” than for non-certified foods (20). At the same time, as environmental issues become more prominent and the concept of green and low-carbon is strengthened, the public is also willing to pay a premium for food products with a lower carbon footprint (21). In addition, some external factors may also influence consumers’ willingness to pay a premium. Huo et al. (22) found through an empirical study that credibility attributes stimulate consumer attitudes and increase consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for food products. Consumers prefer to pay a premium for packaged products over unpackaged product (23). It has also been noted that consumers have different attitudes toward paying a premium depending on the marketing channel (24). Table 1 summarizes articles that use external cues as a research perspective on how external factors affect consumers’ willingness to pay premiums.

Table 1. Studies of the effect of external factors on consumers’ willingness to purchase at premium prices.

And anchors, as opinion leaders in social media, can have a significant impact on consumer decision-making. When anchors recommend a certain product or service in social media, consumers tend to pay high attention to their promotions. Influenced by social recognition and group effect, consumers are willing to pay a higher price for the products recommended by anchors. Therefore, as an important external cue for users to make decisions in the social media environment, the influence of anchors on consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for food cannot be ignored, and this study focuses on anchors as an external influencing factor.

2.3. Anchor characteristics and willingness to pay a premium

Live streaming has the characteristics of immediacy, interactivity, and authenticity, and consumers cannot make purchase decisions simply through the display of product appearance when buying food online, making their decision making behavior more dependent on online anchors (30). In the live shopping scenario, the anchors actively interact with consumers by showing the products, introducing their functions, ingredients, and effects, and then contribute to their purchase behavior (31). Different anchors will show different characteristics in the process of live-streaming with products, reflecting the professional ability and social attributes of the anchors, which have a guiding effect on consumers’ purchasing decision behavior (32). Combining the characteristics of marketing models in the food industry, this paper summarizes three main characteristics of anchors, which are interactivity, professionalism, and popularity. Interactivity is a key factor that influences the willingness to purchase in the food product line (33). Good interaction can motivate potential customers to buy (34). Especially for some high-priced food products, which are often of higher quality in terms of raw materials, production process and nutritional value, and such information is not easily understood by consumers, when there is good interaction between anchors and consumers, it can reduce information asymmetry, enhance consumers’ shopping experience and increase the willingness to purchase at a premium (35). Professionalism refers to the familiarity of the anchor with the product and the information related to it. The more professional the anchor is, the more consumers trust the efficacy and value of the products he or she introduces (36). Wang et al. (37) who suggest that consumers tend to make purchase decisions through the recommendations of opinion leaders, and when the anchor is able to explain clearly the reason for the premium price of the food product, it will lead to consumers’ purchase behavior. Popularity refers to how well known the anchor is to the public. Anchors with higher visibility tend to have higher influence and credibility in the industry (38). In a time when product quality and safety are prominent issues, consumers expect to purchase products that are guaranteed, and anchors with higher popularity are generally able to provide better guarantees. In addition, consumers’ food consumption behavior is influenced by celebrity endorsement, and consumers are more willing to pay a premium for food recommended by celebrities. Highly popularity anchors have a celebrity effect, and their recommended products can receive attention and elicit a premium purchase desire (39). Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: anchor characteristics positively influence consumers' willingness to pay a premium for food;

H1a: the professionalism of anchors positively influences consumers' willingness to pay at a premium;

H1b: the interactivity of anchors positively influences consumers' willingness to pay at a premium;

H1c: the popularity of anchors positively influences consumers' willingness to pay at a premium.

2.4. Mediating role of perceived value

Perceived value is a subjective judgment and measurement of the actual value of a product or service based on consumers’ own feelings (40). As the opinion leader in the live broadcast, the anchor’s own characteristics are an important factor to attract consumers. Special products such as food are difficult to make purchase decisions through factors such as simple physical characteristics, and professional anchors can convey information about the efficacy and value of the products to consumers, increasing their knowledge of the products, reducing uncertainty in the shopping process, and enhancing consumers’ perceived value (41). Highly popularity anchors are admired and sought after by the public because of their image appeal and social influence, and consumers can achieve a homogeneous identity with the anchors by purchasing the products they recommend (42). At the same time, high prices often signal economic superiority and high social status, and premium-priced foods recommended by high- popularity anchors can enhance consumers’ perceived social value (43). Some scholars found through empirical studies that higher interactivity is associated with higher consumer satisfaction and perceived value (44). Consumers are able to obtain more information about the food and enhance their perception by interacting with the anchor in real time while watching the live broadcast.

Before making a purchase decision, consumers integrate a range of information about a product to make a judgment about its value. In general, the higher the perceived value, the stronger the purchase motivation (45). When consumers are able to have a strong perception of the value of the recommended food, they will pay more attention to the quality and effectiveness of the food or service and will not be overly concerned about the financial gain or loss, resulting in a premium purchase behavior (7). Previous studies have also pointed out that in the process of live shopping, when consumers receive the stimulus of the anchor and the product, they form cognitive and emotional responses, and ultimately produce impulse consumption-like behaviors such as premium purchases (46). The cognitive and emotional components of perceived value can play a mediating role in external stimuli and consumer behavioral responses, which rationally explains the psychological mechanism that causes the relationship between anchors and purchase intention (47). According to the halo effect, when consumers have a better experience during the live broadcast of the anchor, they will build some confidence in the food they recommend, which will influence their perceived attitude and thus purchase intention (48). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Consumer perceived value has a positive effect on willingness to pay at a premium.

H3: Perceived value mediates the relationship between anchor characteristics and willingness to pay at a premium;

H3a: perceived value mediates the relationship between anchor professionalism and willingness to pay at a premium;

H3b: perceived value mediates the relationship between anchor interactivity and willingness to pay at a premium;

H3c: perceived value mediates the relationship between anchor popularity and willingness to pay at a premium.

2.5. Moderating effect of limited-time limited-quantity marketing stimulus

Limited-time limited-quantity is the provision of a product or service within a specific time period or limited quantity. It has been transformed from the early limited sale due to the scarcity of raw materials and the inability to mass produce due to seasonal and geographical constraints to a marketing-oriented marketing stimulus with additional content and meanings, which is an important tool for corporate marketing activities (49). When consumers are confronted with such marketing stimuli, they develop a nervousness and scarcity mentality, a process that accelerates the search for and identification of information, at which point they rely more on the power of online opinion leaders, i.e., they rely more on anchors to make purchasing judgments (50). While companies mostly use limited-time limited-quantity as a promotional strategy to achieve revenue, this paper focuses on a sense of scarcity it creates, emphasizing restricted purchase to attract target consumers. Under the marketing stimulus of limited-time limited-quantity, consumers tend to disregard long-term benefits and will make irrational purchases in pursuit of immediate pleasure (51). The perceived value of a product is related to product availability, and the lower the product availability, the higher the perceived value of the consumer (52). For certain food products, which may be in short supply in a particular season due to factors such as weather, consumers’ perceived value of the food product and thus their willingness to purchase it at a premium will be enhanced when they are faced with a limited-time limited-quantity event of the food product introduced during the live broadcast. In addition, products with limited-time limited-quantity labels often symbolize uniqueness, stimulate consumers’ perceived value, and stimulate the desire to purchase when purchase is limited, resulting in purchase behavior (53). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: The limited time limit positively moderates the relationship between perceived value and willingness to purchase at a premium.

Based on the above hypotheses, the theoretical model of this paper is shown in Figure 1.

3. Research design

3.1. Sample source and questionnaire design

This paper uses an online survey tool, Questionnaire Star, to distribute questionnaires and collect data. The survey was conducted from April to May 2023, and the sample was mainly selected from consumers who use social media. Participants used a “snowball” approach to share the questionnaire among their acquaintance networks, and those who could give positive feedback were rewarded with money. Two hundred and seventy-five valid questionnaires were returned.

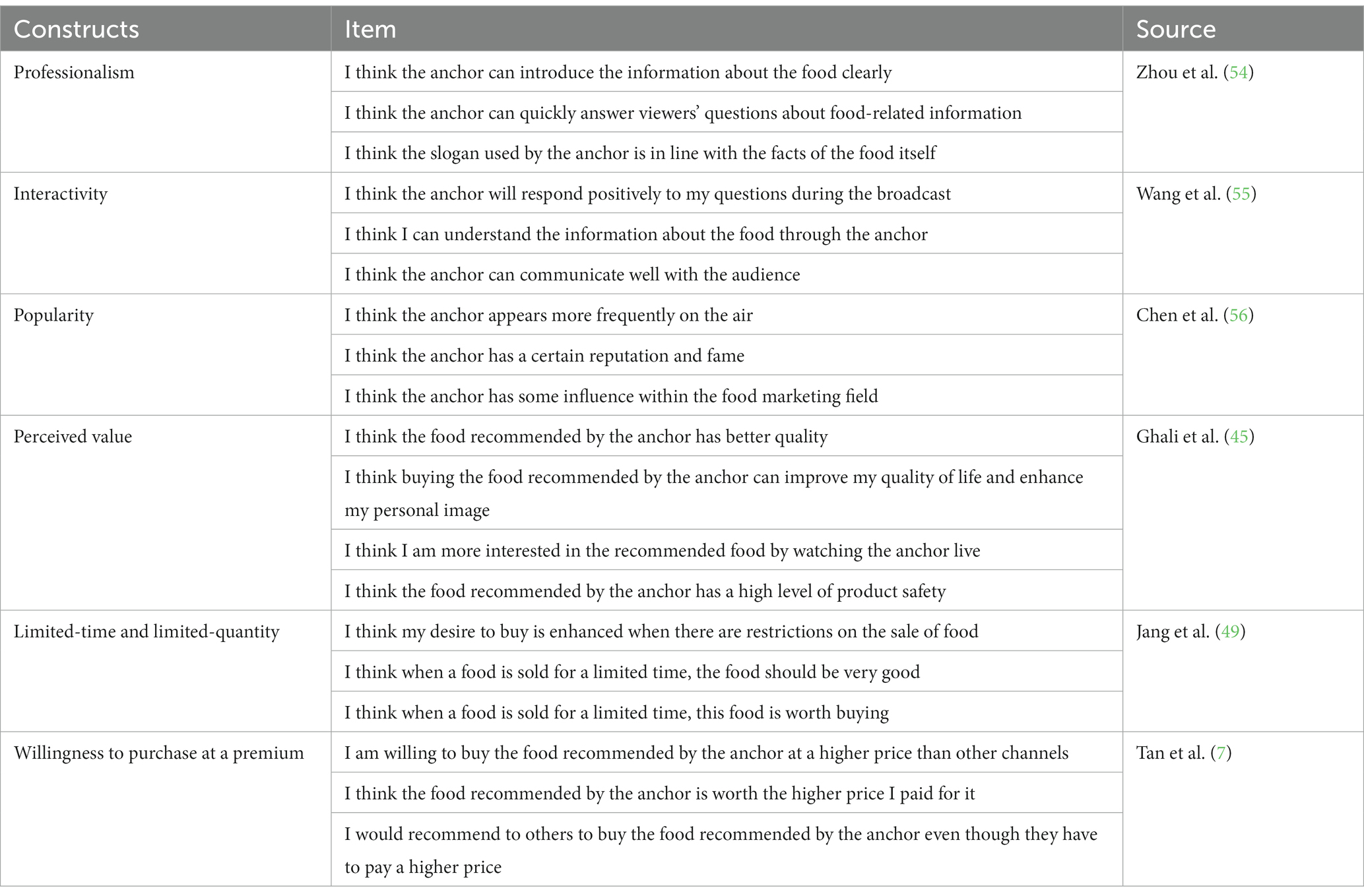

In this paper, based on relevant studies, we designed a questionnaire on the influence of anchor characteristics on consumers’ willingness to purchase food products at a premium, taking into account the behavioral characteristics of food consumers. A five-level Likert scale was used to measure each variable. Among them, the measurement of anchor characteristics (professionalism, interactivity, and popularity) was mainly referred to Zhou et al.’s study; the measurement of perceived value was mainly referred to Ghali’s study; limited-time limited-quantity was measured by designing three questions according to Jang et al.’s study; and the willingness to purchase at a premium was measured by three question items from Tan et al. The specific measurement questions for each variable are shown in Table 2.

3.2. Data collection

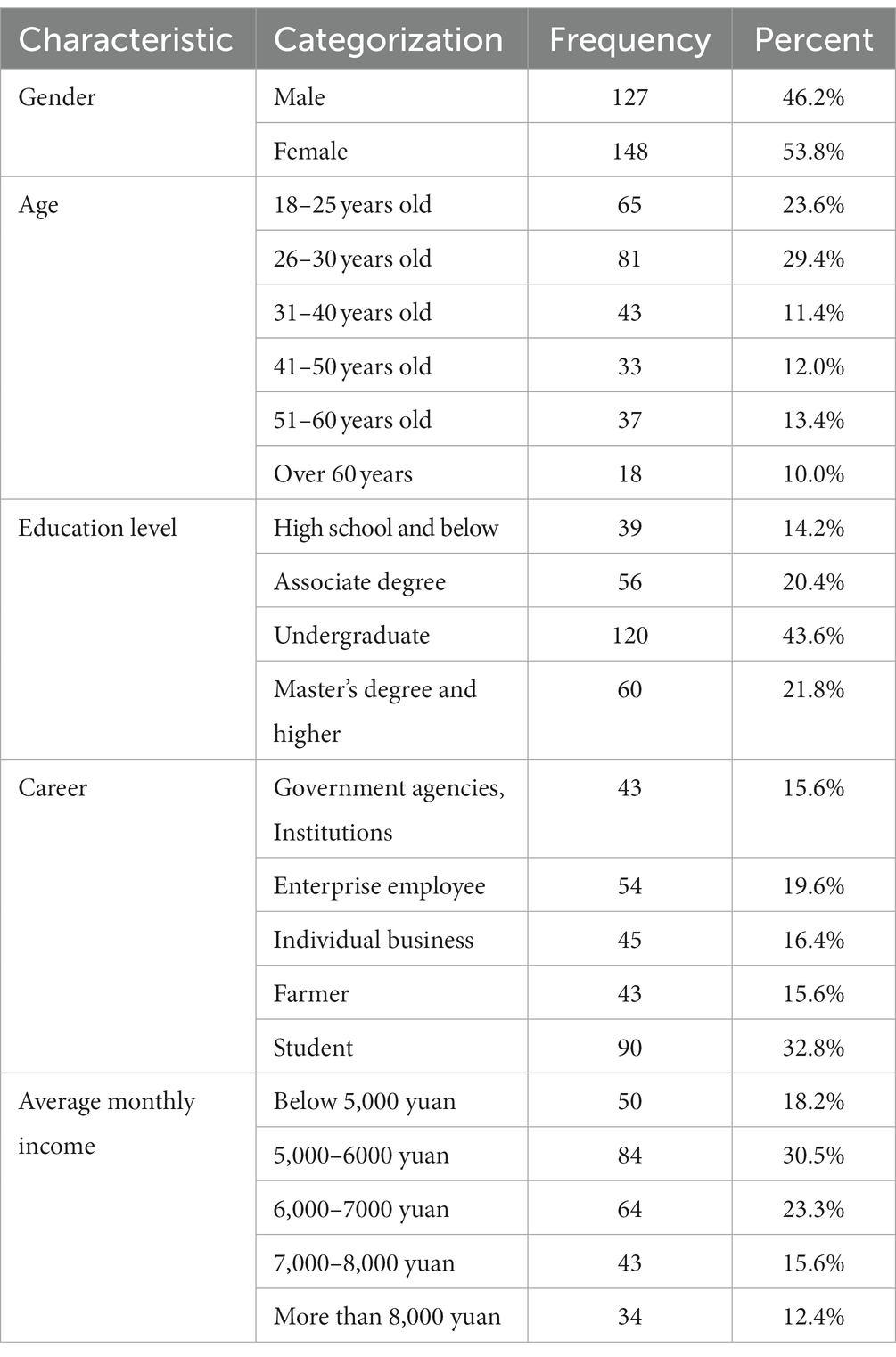

Table 3 shows the basic information of the sample of this survey. The results show that the gender composition of the valid sample is relatively balanced. In terms of the age composition of the sample, the majority of consumers are between 18 and 30 years old, and this age group is also the most used group of social media. In terms of education and income, the largest percentages are undergraduate and $5,000 to $6,000, respectively. This indicates that respondents have a relatively high level of education and income. Overall, the sample is well representative.

4. Empirical analyses

4.1. Reliability and validity analysis

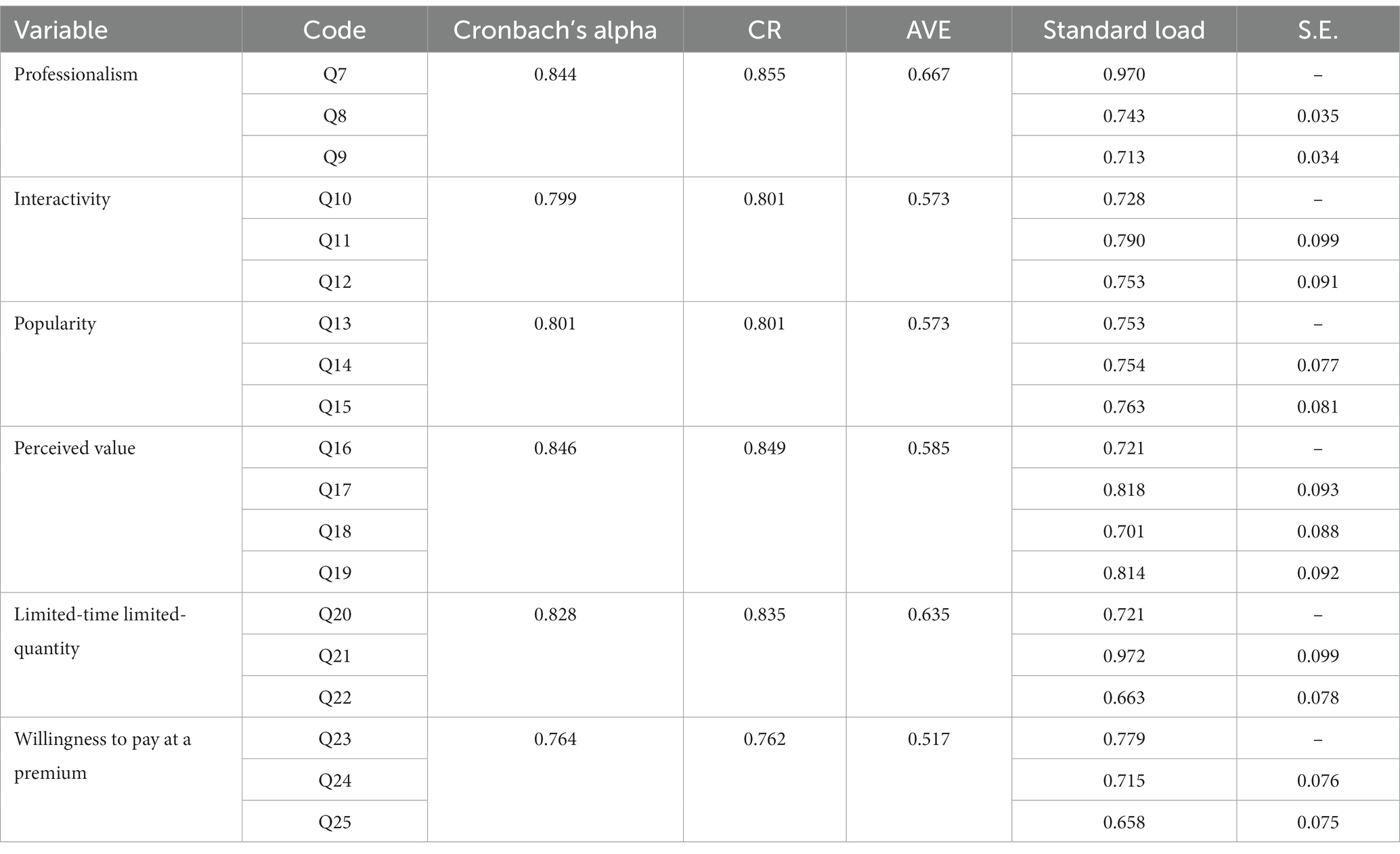

In this paper, SPSS and AMOS software were used to conduct validation factor analysis to test the reliability and validity of the sample data measuring anchor characteristics (professionalism, interactivity, and popularity), perceived value, limited-time limited-quantity, and willingness to pay at a premium, and the results of the analysis are shown in Tables 4, 5.

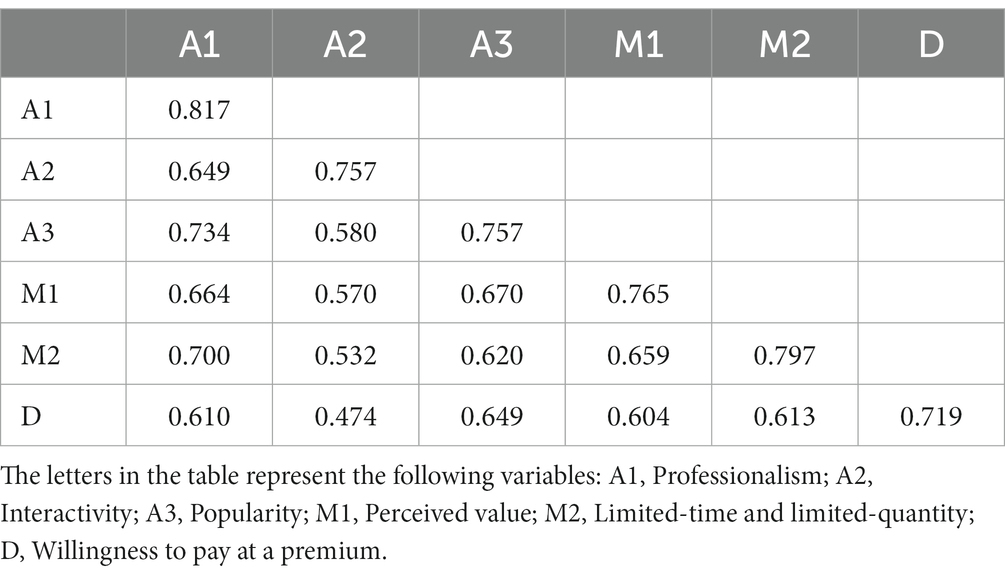

From the results measured in Tables 4, 5, it can be seen that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all variables in this paper exceed 0.7, and the combined reliability (CR) is greater than 0.7, indicating that the scales used in this study have good reliability. In addition, the standardized loadings coefficients in this study ranged from 0.658 to 0.972, the AVE were all greater than 0.5, and the square root of AVE were greater than the correlation coefficients between them and other constructs, indicating that the scale has good convergent validity and discriminant validity, and the reliability test passed (57).

4.2. Hypothesis testing

4.2.1. Correlation analysis

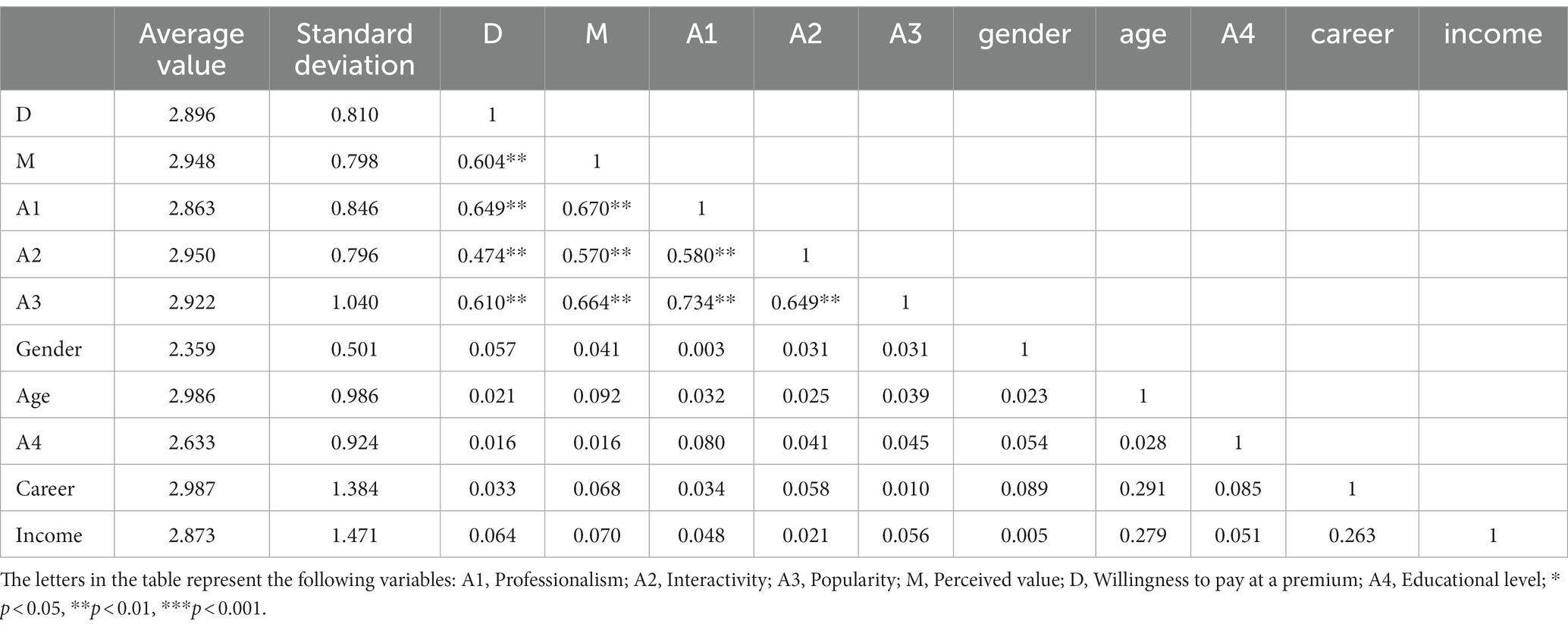

In this paper, we first analyze the relationship between the variables using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The mean, standard deviation and correlation coefficient of each variable are shown in Table 6. It was found that there were significant positive correlations between anchor characteristics (professionalism, interactivity and popularity), perceived value and willingness to pay at a premium. In addition, there was no significant correlation between the other demographic variables and the study variables, ruling out the effect of demographic variables, which provided a basis for further analysis.

4.2.2. Regression analysis

In this paper, we first regress the professionalism, interactivity and popularity of anchor characteristics as independent variables and the willingness to pay at a premium as dependent variables, and the results are shown in Table 7. The results show that professionalism (t = 6.327, p = 0.000) and popularity (t = 3.620, p = 0.000) have a positive effect on the willingness to pay at a premium, and H1a, H1c are confirmed, while interactivity (t = 1.008, p = 0.314) does not have an effect on the willingness to purchase at a premium.

Next, the regression analysis of perceived value on willingness to pay at a premium was conducted, and it was found that perceived value (t = 12.531, p = 0.000) positively influences willingness to pay at a premium, and H2 was confirmed.

4.2.3. Mediation effect test

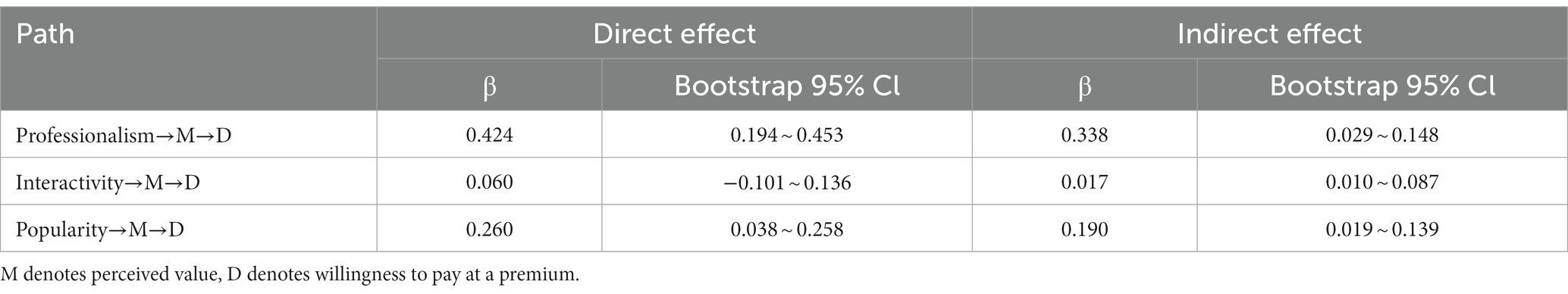

In this paper, we use model 4 in the process plug-in of SPSS to test for mediating effects (58), We chose the Bootstrap test and set the number of repetitions to 5,000 and the confidence interval to 95% for testing. The results of the study are shown in Table 8.

The bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for both the indirect effect [0.029, 0.148] and the direct effect [0.194, 0.453] of perceived value in path 1 do not contain 0, suggesting that perceived value partially mediates the relationship between anchor professionalism and willingness to pay at a premium. The bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect [0.010, 0.087] and the direct effect [−0.101, 0.136] of perceived value in path 2 contain 0, indicating that perceived value fully mediates the relationship between anchor interactivity and willingness to pay at a premium. The bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for both the indirect effect [0.019, 0.139] and the direct effect [0.038, 0.258] of perceived value in path 3 do not contain 0, indicating that perceived value partially mediates the relationship between anchor popularity and willingness to pay at a premium. Therefore, all hypotheses of H3 hold.

4.2.4. Moderating effect test

In this paper, we base on the model 14 proposed by Hayes (59) for the moderated mediation test. The tests for mediating effects with moderation are shown in Table 9. When the independent variable is anchor professionalism, the mediating effect of perceived value is insignificant at the low limited-time limited-quantity level (indirect effect = 0.041, Boot CI = [−0.018, 0.107]), while the mediating effect of perceived value is significant at the high limited-time limited-quantity level (indirect effect = 0.072, Boot CI = [0.014, 0.109]). The results indicate that there is a significant difference between the low and high limited-time limited-quantity groups in terms of whether premium purchase intentions are influenced through perceived value, with the mediating effect of perceived value being moderated by the limited-time limited-quantity marketing stimulus. Similarly, when the independent variable was anchor popularity/interactivity, the limited-time limited-quantity also strengthened the mediating effect of perceived value between anchor popularity/interactivity and willingness to pay at a premium, and hypothesis H4 was confirmed.

4.3. Summary

In this study, each hypothesis was tested by regression analysis, mediating effect test, and moderating effect test, and all the hypotheses held except hypothesis H1b. This indicates that in the social media era, anchors as opinion leaders largely influence consumers’ decision-making behavior. For premium food such as Netflix food, the professionalism and popularity of the anchor play an important role in influencing consumers’ premium purchase intention. Professional anchors can clearly convey all kinds of product attributes to consumers, and well satisfy consumers’ information demand. The higher the popularity of the anchor, the greater the stickiness of its fans, which can better form a group effect, and then stimulate the consumer’s willingness to buy at a premium. The anchor interactivity does not have a direct impact on consumers’ premium purchase intention. This may be due to the fact that for food products, consumers do not have high personalized demands and do not rely on highly interactive anchors to give targeted recommendations. In addition, perceived value plays a mediating role in the influence of anchor characteristics on consumers’ premium purchase intention. At the same time, the marketing stimulus of creating a sense of scarcity at the same time can stimulate consumers’ desire to buy and facilitate the sales of premium products.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical significance

This paper focuses on the influence of anchors, an external factor, on consumers’ willingness to purchase food at a premium, broadening the scope of research in food-related fields. In the era of social media, anchors, as opinion leaders, largely influence consumers’ decision-making behavior. Although a large number of studies have emphasized the role of anchors in consumers’ purchasing behavior, they have not addressed the study of food products (60). And it is worth exploring whether the external cue of anchors plays a role in food and beverage as a popular area in live streaming (61). This paper confirms through empirical research that the professionalism and popularity of anchors can have an impact on consumers’ willingness to purchase food products at a premium. And the professionalism of the anchor has the greatest impact on consumers’ willingness to pay at a premium, which means that consumers pay more attention to the professional output of the anchor when purchasing premium food products (62). This process can effectively reduce the information gap, so that consumers can understand the source of the premium “label” and enhance their perceived value. The results of this study provide a new theoretical basis for companies to develop marketing strategies for premium foods and select appropriate anchors for promotion.

Second, this paper reveals the intrinsic psychological mechanisms of consumers in the process of purchasing premium foods and promotes the explanation of the relationship between anchor characteristics and willingness to pay at a premium. Although existing studies have emphasized the mediating role of perceived value between anchor characteristics and product purchase intentions without focusing on premium-priced products (63). At the same time, some scholars have also pointed out that the psychological factor of consumers’ perceived value will have an effect on premium purchase intention, but it has not been considered from the perspective of anchor characteristics (64). In conclusion, premium foods require consumers to pay higher prices compared to similar foods, and it has not been confirmed by scholars whether the mediating variable of perceived value also plays a role in the effect of anchor characteristics on consumers’ willingness to purchase at a premium (31). This study found that perceived value still plays a role in the effect of anchor characteristics on premium food purchases, which enriches the scope of research on perceived value as a mediating variable.

Finally, this paper enhances the explanatory power of the SOR model by adding limited time limit as a moderating variable of the model. The model explains that consumers’ willingness to pay premium prices for online food is driven and constrained by anchor characteristics, perceived value, and limited-time limited-quantity. The empirical study identifies the moderating role of the marketing stimulus of limited-time limited-quantity in the relationship between perceived value and willingness to pay premium, and refines the paths through which different characteristics of anchors influence consumers’ premium purchase behavior through perceived value (65). While most scholars have previously studied this marketing stimulus as a promotional strategy, for example, this paper focuses on the sense of scarcity created by limited-time limited-quantity (66). Product scarcity creates a positive impact that can increase the pleasure of consuming a product and promote consumers’ perceived value of that product. The current study finds that limited time limits strengthen the mediating role of perceived value between anchor characteristics and premium purchase intentions, expanding the boundaries of existing research on premium food purchases.

5.2. Management significance

First, companies need to develop a reasonable marketing strategy and choose the right anchor for product promotion. Specifically, the most critical thing is to consider the professionalism of the anchor. Due to the special nature of food products, the professional introduction of the anchor is needed to make consumers understand more clearly the relevant product attributes and characteristics and other information (67). In addition, try to choose high-profile anchors to promote related products. Netflix food is often popular among the public, and high-profile anchors who “match” them are often better able to play a good publicity effect, thus increasing consumers’ willingness to buy food at a premium.

Secondly, when promoting food products to consumers, companies should pay attention to the perceived value of consumers. For example, you can consider the design of eye-catching, beautiful, unique product packaging, incorporating trendy elements, highlighting the visual effects and other ways to enhance consumer perception of entertainment value. Nowadays, selling “emotion” has become one of the selling points of “Netflix” food, and actively creating a unique brand style can enhance consumers’ emotional value perception (68). In addition, food safety accidents are frequent, and companies should strengthen their brand image to ensure food safety and show that they attach great importance to food quality and safety, so as to enhance consumers’ perception of safety value.

Finally, companies should take appropriate marketing stimuli to increase consumers’ willingness to buy at a premium. Food products are often affected by seasonal and other factors only launched in a specific season, for this type of food, companies can adopt a limited-time limited-quantity marketing strategy to stimulate consumers’ desire to buy. Companies can also reduce the production of food products to make them in short supply, so as to achieve the purpose of maintaining high popularity means (69). In addition, if companies want to increase consumer stickiness to gain more profits, they can increase the restrictions on consumer status and other restrictions to improve consumer loyalty to the brand, and how to make the Netflix food long red is a problem worth thinking about for companies.

5.3. Limitations and prospects

First, in terms of research perspective, this paper only explores the impact of different anchor characteristics on consumers’ willingness to pay at a premium, while the interaction of different types of anchors, anchor types and product types often also has different effects on consumer behavior (70). Second, although this paper focuses on the moderating role of limited-time limited-quantity, it does not make a strict distinction between such marketing stimuli (71). And although both limited-time or limited-quantity scarcity marketing stimuli can have an impact on consumers’ purchase intentions, there may be differences in the degree of impact between these two stimuli (72), future research could focus on this difference for a deeper exploration. Finally, factors such as consumers’ personal preferences may affect the willingness to purchase at a premium, and future research could explore the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions of consumers’ premium purchasing behavior more fully and rationally.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Guangxi science and technology plan project (guikeAB23026053), Guangxi University Young and middle-aged teachers’ basic scientific research ability improvement project (2021KY1675), Guilin science and technology research and development project (20180102-2).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bozkurt, S, Gligor, DM, and Babin, BJ. The role of perceived firm social media interactivity in facilitating customer engagement behaviors. Eur J Mark. (2021) 55:995–1022. doi: 10.1108/EJM-07-2019-0613

2. Zhou, Y, Li, Y-Q, Ruan, W-Q, and Zhang, S-N. Owned media or earned media? The influence of social media types on impulse buying intention in internet celebrity restaurants. Int J Hosp Manag. (2023) 111:103487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2023.103487

3. Bulsara, HP, and Trivedi, M. Exploring the role of availability and willingness to pay premium in influencing Smart City Customers' purchase intentions for green food products. Ecol Food Nutr. (2023) 62:107–29. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2023.2200942

4. Marozzo, V, Costa, A, Crupi, A, and Abbate, T. Decoding Asian consumers' willingness to pay for organic food product: a configurational-based approach. Eur J Innov Manag. (2023) 26:353–84. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-10-2022-0591

5. Nagano, M, Ijima, Y, and Hiroya, S. Perceived emotional states mediate willingness to buy from advertising speech. Front Psychol. (2023) 13:1014921. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1014921

6. Lin, C. An empirical study on decision factors affecting fresh e-commerce purchasing geographical indications agricultural products. Acta Agricult Scand B Soil Plant Sci. (2021) 71:541–51. doi: 10.1080/09064710.2020.1834610

7. Tan, L, Li, H, Chang, Y-W, Chen, J, and Liou, J-W. How to motivate consumers' impulse buying and repeat buying? The role of marketing stimuli, situational factors and personality. Curr Psychol. (2023). 3:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-04230-4

8. Ma, X, Zou, X, and Lv, J. Why do consumers hesitate to purchase in live streaming? A perspective of interaction between participants. Electron Commer Res Appl. (2022) 55:101193. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2022.101193

9. Ma, ER, Liu, JJ, and Li, K. Exploring the mechanism of live streaming e-commerce anchors' language appeals on users' purchase intention. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1109092

10. Xu, XY, Huang, D, and Shang, XY. Social presence or physical presence? Determinants of purchasing behaviour in tourism live-streamed shopping. Tour Manag Perspect. (2021) 40:100917. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100917

11. Zheng, S, Lyu, X, Wang, J, and Wachenheim, C. Enhancing sales of green agricultural products through live streaming in China: what affects purchase intention? Sustainability. (2023) 15:5858. doi: 10.3390/su15075858

12. Marescotti, ME, Amato, M, Demartini, E, La Barbera, F, Verneau, F, and Gaviglio, A. The effect of verbal and iconic messages in the promotion of high-Quality Mountain cheese: a non-hypothetical BDM approach. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3063. doi: 10.3390/nu13093063

13. Kung, ML, Wang, JH, and Liang, CY. Impact of purchase preference, perceived value, and marketing mix on purchase intention and willingness to pay for pork. Foods. (2021) 10:2396. doi: 10.3390/foods10102396

14. Berger, J. Signaling can increase consumers' willingness to pay for green products. Theoretical model and experimental evidence. J Consum Behav. (2019) 18:233–46. doi: 10.1002/cb.1760

15. Wang, TT, Liang, SY, and Sun, YX. So curious that I want to buy it: the positive effect of queue wait on consumers' purchase intentions. J Consum Behav. (2023) 22:848–66. doi: 10.1002/cb.2169

16. Guo, J, Li, Y, Xu, YJ, and Zeng, K. How live streaming features impact Consumers' purchase intention in the context of cross-border E-commerce? A research based on SOR theory. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:767876. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.767876

17. Chen, M, and Chen, J D, editors. Effects of internet word-of-mouth of a tourism destination on consumer purchase intention: based on temporal distance and social distance. 11th Annual International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management (ICMSEM); 2017 Jul 28–31, Kanazawa, (2018).

18. Huang, LT. Flow and social capital theory in online impulse buying. J Bus Res. (2016) 69:2277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.042

19. Lang, M, and Rodrigues, AC. A comparison of organic-certified versus non-certified natural foods: perceptions and motives and their influence on purchase behaviors. Appetite. (2022) 168:105698. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105698

20. Bryla, P. Selected predictors of the importance attached to salt content information on the food packaging (a study among polish consumers). Nutrients. (2020) 12:293. doi: 10.3390/nu12020293

21. Mahasuweerachai, P, and Suttikun, C. The effect of green self-identity on perceived image, warm glow and willingness to purchase: a new Generation's perspective towards eco-friendly restaurants. Sustainability. (2022) 14:10539. doi: 10.3390/su141710539

22. Huo, H, Jiang, XY, Han, CJ, Wei, S, Yu, DY, and Tong, Y. The effect of credence attributes on willingness to pay a premium for organic food: a moderated mediation model of attitudes and uncertainty. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1087324. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1087324

23. Wilson, L, and Lusk, JL. Consumer willingness to pay for redundant food labels. Food Policy. (2020) 97:101938. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101938

24. Witzling, L, and Shaw, BR. Lifestyle segmentation and political ideology: toward understanding beliefs and behavior about local food. Appetite. (2019) 132:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.10.003

25. Trivedi, M, Bulsara, HP, and Shukla, Y. Why millennials of smart city are willing to pay premium for toxic-free food products: social media perspective. Br Food J. (2023). 9:1–15. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-07-2022-0649

26. Zheng, MH, Tang, DC, Chen, JH, Zheng, QJ, and Xu, AX. How different advertising appeals (green vs. non-green) impact consumers' willingness to pay a premium for green agricultural products. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:991525. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.991525

27. Yu, WP, Han, XY, and Cui, FS. Increase consumers' willingness to pay a premium for organic food in restaurants: explore the role of comparative advertising. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:982311. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.982311

28. Li, R, Laroche, M, Richard, MO, and Cui, XY. More than a mere cup of coffee: when perceived luxuriousness triggers Chinese customers' perceptions of quality and self-congruity. J Retail Consum Serv. (2022) 64:102759. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102759

29. Calvo-Porral, C, Rivaroli, S, and Orosa-Gonzalez, J. The influence of celebrity endorsement on food consumption behavior. Foods. (2021) 10:2224. doi: 10.3390/foods10092224

30. He, W, and Jin, CY. A study on the influence of the characteristics of key opinion leaders on consumers' purchase intention in live streaming commerce: based on dual-systems theory. Electron Commer Res. (2022). 12:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10660-022-09651-8

31. Song, ZJ, Liu, C, and Shi, R. How do fresh live broadcast impact Consumers' purchase intention? Based on the SOR theory. Sustainability. (2022) 14:14382. doi: 10.3390/su142114382

32. Kyoung, PK. The influence of show host characteristics on consumers’ responses to agricultural products: focusing on the moderating role of purchasing experience through live streaming commerce. J Market Manag Res. (2022) 27:71–94. doi: 10.37202/KMMR.2022.27.2.71

33. Sun, JY, and Min, LT. The effects of interactivity on purchase intention in live commerce environments: focused on the moderating role of show host expertise and product type. e-Business Stud. (2022) 23:133–57. doi: 10.20462/tebs.2022.11.23.6.133

34. Zheng, SY, Chen, JD, Liao, JY, and Hu, HL. What motivates users? Viewing and purchasing behavior motivations in live streaming: a stream-streamer-viewer perspective. J Retail Consum Serv. (2023) 72:103240. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103240

35. Zhan, JT, Ma, YB, Deng, PC, Li, YQ, Xu, M, and Xiong, H. Designing enhanced labeling information to increase consumer willingness to pay for genetically modified foods. Br Food J. (2021) 123:405–18. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-08-2019-0637

36. Li, GM, Jiang, Y, and Chang, LT. The influence mechanism of interaction quality in live streaming shopping on Consumers' impulsive purchase intention. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:918196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.918196

37. Wang, J L, Ding, K Z, Zhu, Z W, Zhang, Y, and Caverlee, J, Acm, editors. Key opinion leaders in recommendation systems: opinion elicitation and diffusion. 13th Annual ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM); 2020 Feb 03–07, Houston, TX. (2020).

38. Huang, QQ, Qu, HJ, and Li, P. The influence of virtual idol characteristics on Consumers' clothing purchase intention. Sustainability. (2022) 14:8964. doi: 10.3390/su14148964

39. Wang, W, Huang, MX, Zheng, SY, Lin, LT, and Wang, L. The impact of broadcasters on Consumer's intention to follow livestream Brand Community. Front Psychol. (2022) 12:810883. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810883

40. Aw, ECX, Basha, NK, Ng, SI, and Sambasivan, M. To grab or not to grab? The role of trust and perceived value in on-demand ridesharing services. Asia Pac J Mark Logist. (2019) 31:1442–65. doi: 10.1108/APJML-09-2018-0368

41. Chen, CF, and Zhang, DP. Understanding consumers' live-streaming shopping from a benefit-risk perspective. J Serv Mark. (2023). 23:1–13. doi: 10.1108/JSM-04-2022-0143

42. Guo, YY, Zhang, KX, and Wang, CY. Way to success: understanding top streamer's popularity and influence from the perspective of source characteristics. J Retail Consum Serv. (2022) 64:102786. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102786

43. Kim, HJ. Diverging influences of money priming on choice: the moderating effect of consumption situation. Psychol Rep. (2017) 120:695–706. doi: 10.1177/0033294117701905

44. Li, XC, Liao, QY, Luo, X, and Wang, YY. Juxtaposing impacts of social media interaction experiences on e-commerce reputation. J Electron Commer Res. (2020) 21:75–95. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v14i08.10404

45. Ghali, ZZ. Effect of utilitarian and hedonic values on consumer willingness to buy and to pay for organic olive oil in Tunisia. Br Food J. (2020) 122:1013–26. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-06-2019-0414

46. Sestino, A, Rossi, MV, Giraldi, L, and Faggioni, F. Innovative food and sustainable consumption behaviour: the role of communication focus and consumer-related characteristics in lab-grown meat (LGM) consumption. Br Food J. (2023) 125:2884–901. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-09-2022-0751

47. Zhang, B, Li, J, Feng, YT, and Liu, DN. Factors analysis of Consumers' purchasing intention under the background of live E-commerce shopping. J Internet Technol. (2023) 24:809–15. doi: 10.53106/160792642023052403023

48. Zhong, X, and Yan, J. Marketer generated content on social media: how to support corporate online distribution. J Distribut Sci. (2022) 20:33–43. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v17i17.34031

49. Jang, W, Ko, YJ, Morris, JD, and Chang, YW. Scarcity message effects on consumption behavior: limited edition product considerations. Psychol Mark. (2015) 32:989–1001. doi: 10.1002/mar.20836

50. Ishihara, M, Kwon, M, and Mizuno, M. An empirical study of scarcity marketing strategies: limited-time products with umbrella branding in the beer market. J Acad Mark Sci. (2022). 3:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11747-022-00899-y

51. Li, J, Yang, RR, Cui, JJ, and Guo, YY. Imagination matters when you shop online: the moderating role of mental simulation between materialism and online impulsive buying. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2019) 12:1071–9. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S227403

52. Wu, L, and Lee, C. Limited edition for me and best seller for you: the impact of scarcity versus popularity cues on self versus other-purchase behavior. J Retail. (2016) 92:486–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2016.08.001

53. Chae, H, Kim, S, Lee, J, and Park, K. Impact of product characteristics of limited edition shoes on perceived value, brand trust, and purchase intention; focused on the scarcity message frequency. J Bus Res. (2020) 120:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.040

54. Zhou, Y, and Huang, WM. The influence of network anchor traits on shopping intentions in a live streaming marketing context: the mediating role of value perception and the moderating role of consumer involvement. Econ Anal Policy. (2023) 78:332–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2023.02.005

55. Wang, L, Wang, ZH, Wang, XY, and Zhao, Y. Assessing word-of-mouth reputation of influencers on B2C live streaming platforms: the role of the characteristics of information source. Asia Pac J Mark Logist. (2022) 34:1544–70. doi: 10.1108/APJML-03-2021-0197

56. Chen, ML, Xie, ZH, Zhang, J, and Li, YY. Internet Celebrities' impact on luxury fashion impulse buying. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res. (2021) 16:2470–89. doi: 10.3390/jtaer16060136

57. Biasutti, M, and Frate, S. A validity and reliability study of the attitudes toward sustainable development scale. Environ Educ Res. (2017) 23:214–30. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2016.1146660

58. Hayes, AF, and Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychol Sci. (2013) 24:1918–27. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187

59. Hayes, AF. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun Monogr. (2018) 85:4–40. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

60. Bradford, H, McKernan, C, Elliott, C, and Dean, M. Consumers' perceptions and willingness to purchase pork labelled 'raised without antibiotics. Appetite. (2022) 171:105900. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105900

61. Dean, D, Rombach, M, de Koning, W, Vriesekoop, F, Satyajaya, W, Yuliandari, P, et al. Understanding key factors influencing Consumers' willingness to try, buy, and pay a Price premium for Mycoproteins. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3292. doi: 10.3390/nu14163292

62. Kumar, S, Gupta, K, Kumar, A, Singh, A, and Singh, RK. Applying the theory of reasoned action to examine consumers' attitude and willingness to purchase organic foods. Int J Consum Stud. (2023) 47:118–35. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12812

63. Ma, L, Li, Z, and Zheng, D. Analysis of Chinese consumers' willingness and behavioral change to purchase green Agri-food product online. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0265887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265887

64. Ouyang, J, Jia, Y, and Guo, Z. The effects of a dividing line in a product assortment on perceived quantity, willingness to buy, and choice satisfaction. Psychol Mark. (2022) 39:1511–28. doi: 10.1002/mar.21669

65. Thanki, H, Shah, S, Oza, A, Vizureanu, P, and Burduhos-Nergis, DD. Sustainable consumption: will they buy it again? Factors influencing the intention to repurchase organic food grain. Foods. (2022) 11:11. doi: 10.3390/foods11193046

66. Feng, N, Zhang, A, van Klinken, RD, and Cui, L. An integrative model to understand consumers' trust and willingness to buy imported fresh fruit in urban China. Br Food J. (2021) 123:2216–34. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-07-2020-0575

67. Nagano, M, Ijima, Y, and Hiroya, S, (Eds) Impact of emotional state on estimation of willingness to buy from advertising speech. Interspeech Conference; 2021 2021 Aug 30-Sep 03, Brno. (2021).

68. de Amorim, IP, Guerreiro, J, Eloy, S, and Correia Loureiro, SM. How augmented reality media richness influences consumer behaviour. Int J Consum Stud. (2022) 46:2351–66. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12790

69. Jose, H, and Kuriakose, V. Emotional or logical: reason for consumers to buy organic food products. Br Food J. (2021) 123:3999–4016. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-10-2020-0916

70. Song, M, Zhao, Y, Li, X, and Meng, L. The influence exerted by time frames on Consumers' willingness to buy nearly expired food. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:790727. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790727

71. Suci, A, Maryanti, S, Hardi, H, and Sudiar, N. Willingness to pay for traditional ready-to-eat food packaging: examining the interplay between shape, font and slogan. Asia Pac J Mark Logist. (2022) 34:1614–33. doi: 10.1108/APJML-04-2021-0233

Keywords: anchor characteristics, perceived value, premium purchase, limited-time, limited-quantity

Citation: Maojie Z (2023) The impact of anchor characteristics on consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for food—an empirical study. Front. Nutr. 10:1240503. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1240503

Edited by:

Shah Fahad, Leshan Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Muhammad Waqas Akbar, Shenzhen University, ChinaFahad Khalid, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, China

Rizwan Ali, Lahore Garrison University, Pakistan

Copyright © 2023 Maojie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhou Maojie, emhvdW1hb2ppZTIwMjNAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Zhou Maojie

Zhou Maojie