95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Nutr. , 04 July 2023

Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1185696

Neha R. Jhaveri1

Neha R. Jhaveri1 Natalia E. Poveda2,3

Natalia E. Poveda2,3 Shivani Kachwaha4

Shivani Kachwaha4 Dawn L. Comeau1

Dawn L. Comeau1 Phuong H. Nguyen5

Phuong H. Nguyen5 Melissa F. Young2,3*

Melissa F. Young2,3*Background: Maternal undernutrition during pregnancy remains a critical public health issue in India. While evidence-based interventions exist, poor program implementation and limited uptake of behavior change interventions make addressing undernutrition complex. To address this challenge, Alive & Thrive implemented interventions to strengthen interpersonal counseling, micronutrient supplement provision, and community mobilization through the government antenatal care (ANC) platform in Uttar Pradesh, India.

Objective: This qualitative study aimed to: (1) examine pregnant women’s experiences of key nutrition-related behaviors (ANC attendance, consuming a diverse diet, supplement intake, weight gain monitoring, and breastfeeding intentions); (2) examine the influence of family members on these behaviors; and (3) identify key facilitators and barriers that affect behavioral adoption.

Methods: We conducted a qualitative study with in-depth interviews with 24 pregnant women, 13 husbands, and 15 mothers-in-law (MIL). We analyzed data through a thematic approach using the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) framework.

Results: For ANC checkups and maternal weight gain monitoring, key facilitators were frontline worker home visits, convenient transportation, and family support, while the primary barrier was low motivation and lack understanding of the importance of ANC checkups. For dietary diversity, there was high reported capability (knowledge related to the key behavior) and most family members were aware of key recommendations; however, structural opportunity barriers (financial strain, lack of food availability and accessibility) prevented behavioral change. Opportunity ranked high for iron and folic acid supplement (IFA) intake, but was not consistently consumed due to side effects. Conversely, lack of supply was the largest barrier for calcium supplement intake. For breastfeeding, there was low overall capability and several participants described receiving inaccurate counseling messages.

Conclusion: Key drivers of maternal nutrition behavior adoption were indicator specific and varied across the capability-opportunity-motivation behavior change spectrum. Findings from this study can help to strengthen future program effectiveness by identifying specific areas of program improvement.

Maternal nutrition is a key contributor to maternal and child morbidity and mortality in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (1). Pregnant women with poor nutritional status are more likely to experience adverse outcomes such as difficult labor, post-partum hemorrhage, poor birth outcomes, and increased morbidity and mortality (1–3). Several evidence- based interventions exist to improve maternal nutrition; however, there remain stark disparities in receipt of maternal health services across the globe (3, 4). In India, malnutrition is the leading risk factor for disease burden, contributing to 68% of the child deaths in 2017; out of all the states, the malnutrition Disability Adjusted Life Years was highest in Uttar Pradesh (5). In Uttar Pradesh, only 42% of women had four or more antenatal care (ANC) visits compared to 58% for all of India, and only 22% of pregnant women consumed iron and folic acid (IFA) for the recommended period of 100 days compared to 44% national average (6). These disparities and gaps in the implementation of evidence-based programs represent a public health challenge in Uttar Pradesh. There is a need to better understand the complex determinants of maternal nutrition-related behaviors in order to inform program improvements.

A global systematic review identified numerous factors that inhibit improvement in maternal nutrition in LMICs, such as household food availability, financial limitations, limited knowledge related to weight gain and food intake, and inadequate dietary counseling (7). Consideration of the broader socio-contextual factors that contribute to behavioral adoption, as well as aspects that affect women’s dietary practices during pregnancy, must be reflected in interventions to address critical gaps. The cultural context is an important consideration to understanding food norms, key actors (i.e., pregnant women’s husbands and mothers-in-law), and their decision-making power related to food decisions (i.e., the food purchased and meals cooked in the house) (8, 9). While much of the literature has focused on maternal attitudes, beliefs, and practices, family members can also be a powerful influencer of behavior change (10). In Nepal, for example, the mother-in-law had both a direct and indirect influence on the daughter-in-law’s food consumption, such as food quantity, types of foods, and the frequency of consumption (11). There is need for further context-specific research to understand role of family members in maternal behavior adoption during pregnancy.

In order to address the high levels of maternal malnutrition and poor program implementation in Uttar Pradesh, Alive & Thrive collaborated with International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), IPE Global, and the Government of India to strengthen an integrated package of nutrition-intensified ANC services including maternal nutrition recommendations such as IFA and calcium supplementation, dietary diversity counseling, breastfeeding counseling, weight gain monitoring, and community mobilization (12). This study aimed to: (1) examine pregnant women’s experiences on key maternal nutrition-related behaviors during pregnancy (ANC checkup attendance, weight gain and monitoring, consuming a diverse diet, supplement intake) and breastfeeding intentions; (2) examine the influence of family members on these behaviors; and (3) identify key facilitators and barriers that affect behavioral adoption.

Our guiding theoretical framework for this study was the capabilities, opportunities, motivations, and behavior (COM-B) framework (13). The COM-B model of behavior is a valuable framework for identifying critical factors that need to be addressed in order for behavior change interventions to be effective. The COM-B model identifies three behavioral domains required to practice a specific behavior: (1) capability- the knowledge or skills needed to perform the behavior, (2) opportunity – the environment and/or social factors that make the behavior doable, and (3) motivation- aspects that can influence the intention and decision-making which drive a behavior. This framework has been widely used globally to examine complex human health behaviors including adherence to COVID-19 mitigation strategies, hand hygiene, and physical activity recommendations (14–19). In addition, the COM-B framework has been utilized to examine infant feeding practices and the associated beliefs to help inform and refine child nutrition interventions (20–22). Thus, the COM-B framework represents an ideal theoretical framework for providing novel insight on the complex components of maternal behavior change required for the successful implementation of the maternal nutrition program in Uttar Pradesh.

This qualitative study was embedded in a larger randomized-controlled impact evaluation of the Alive & Thrive interventions (12, 23). The larger study was conducted in the districts of Unnao and Kanpur- Dehat in Uttar Pradesh, and aimed to assess the delivery and impact of integrating a package of evidence-based recommendations (strengthening the provision of iron and calcium supplementation, counseling on dietary diversity, counseling on breastfeeding, and weight gain monitoring) within the existing government ANC services in 13 intervention blocks. One high-performing and one low-performing intervention block were selected after reviewing and analyzing the program data, which informed the sampling strategy for the interviews at the village level. In-depth interviews were conducted in 4 out of the 13 intervention blocks. Data was purposively collected in one high- and one low performing block in each of the intervention program districts in order to capture a range of program experiences. Twelve indicators were scored to determine whether a block was considered as “high-performing” or “low-performing” (14). For each block, one health subcenter (HSC), and 1–2 villages were selected (Supplementary Figure 1). For each village, 3 pregnant women within the 6 to 8- month of pregnancy from 1 to 2 households were randomly selected from the parent study registry list (24 pregnant women in total). Then, the pregnant women’s family members (13 husbands; 15 mothers in law- MILs) were identified for interviews to understand the family influence. The qualitative study was done to complement the parent study to obtain an in-depth understanding of program implementation and experiences.

Interviews took place from July 2019 through August 2019. In-depth interview guides were developed for pregnant women, MILs, and husbands in English, and later translated to Hindi (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). To ensure methodological rigor, during the development of the instruments, we received multiple rounds of feedback from our partners. The interview guides were pilot tested in Hindi in nearby blocks not associated with the study, which allowed for another round of modification before beginning data collection.

The interviews involved local research assistants who had a deep understanding of the local context. They assisted with interviews and reviewed the tools to verify that the original meaning of the questions was captured in Hindi. For quality control, the researchers randomly selected 10% of the transcripts and cross- checked them with the audio files to ensure accurate translation and quality transcription of the interviews. Between interviews, we debriefed with the research assistants as well as the other team researchers collecting interview data, and took time to reflect on field notes. At the time of analysis, we added memos to the interview transcription based on our observations, discussions during debriefs, and field notes. The guides covered several domains to help understand maternal nutrition behaviors and household dynamics and support, including daily activities, food habits, knowledge and attitudes toward the key indicators, experience with frontline workers (FLWs), and household dynamics.

Interviews were conducted in the participant’s residence. The interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in Hindi, varying in length from 25 to 60 minutes. Audio files were translated and transcribed verbatim into English.

Data was analyzed on MAXQDA2020 using a thematic analysis approach. The lead author was involved in directly conducting interviews as well as data analysis as part of her MPH thesis in Behavioral Sciences and Health Education. The lead author is fluent in English, understands Hindi, and has knowledge of many of the Indian cultural influences from her previous work experience, travel to India, and her own upbringing. Regular debriefing meetings were held with the research team and mentors to facilitate reflexivity, reduce potential bias and ensure analysis and conclusions were grounded in the data transcripts. The lead and co-author independently coded a select number of the family member interviews to develop a draft codebook, and then came to together to finalize the codebook before coding the remaining interviews, ensuring intercoder reliability and minimizing assumptions that could bias the data analysis. After the transcripts were coded, themes were categorized within the appropriate dimension of the COM-B conceptual framework (13). Figure 1 shows the three core components of COM-B (capability, opportunity, and motivation) as defined in the context of this study. Components that contribute to each indicator’s COM were then identified as either a facilitator or barrier. The lead and co-author then reviewed the balance of facilitators and barriers for each key behavior, and developed a summary of the data. Different interpretation of data between the researchers were discussed until consensus was reached about the meaning of the themes. The researchers also developed an overall subjective summary assessment of the level of intensity of facilitators and barriers for the capability, opportunity, and motivation components, which was informed by their assessment of how critical factors were to the behavior change of focus, as well as the prevalence of the facilitators and barriers for the behavior across the interviews (Supplementary Table 3). Based on the consensus of research and program team members, a qualitative summary was developed to denote low-, mid-, or high- level of facilitators or barriers for each component or to identify areas where there was insufficient data.

The Emory Institutional Review Board (IRB00111064) in USA and Suraksha Independent Ethics Committee (SIEC) in India approved study protocols. Oral informed consent was obtained before every interview. The study purpose, voluntary participation, and the effort to maintain confidentiality was stated in Hindi. Additionally, participants were told that they could skip questions or leave the interview at any point. Permission was also obtained before recording the interviews, and participants were informed that the recordings would be deleted after the completion of data analysis.

We examined key factors that influence women’s capability, opportunity, and motivation for each of the six maternal nutrition related behaviors (ANC checkup attendance, consuming a diverse diet, weight gain/weight monitoring, IFA supplement intake, calcium supplement intake, and breastfeeding intentions).

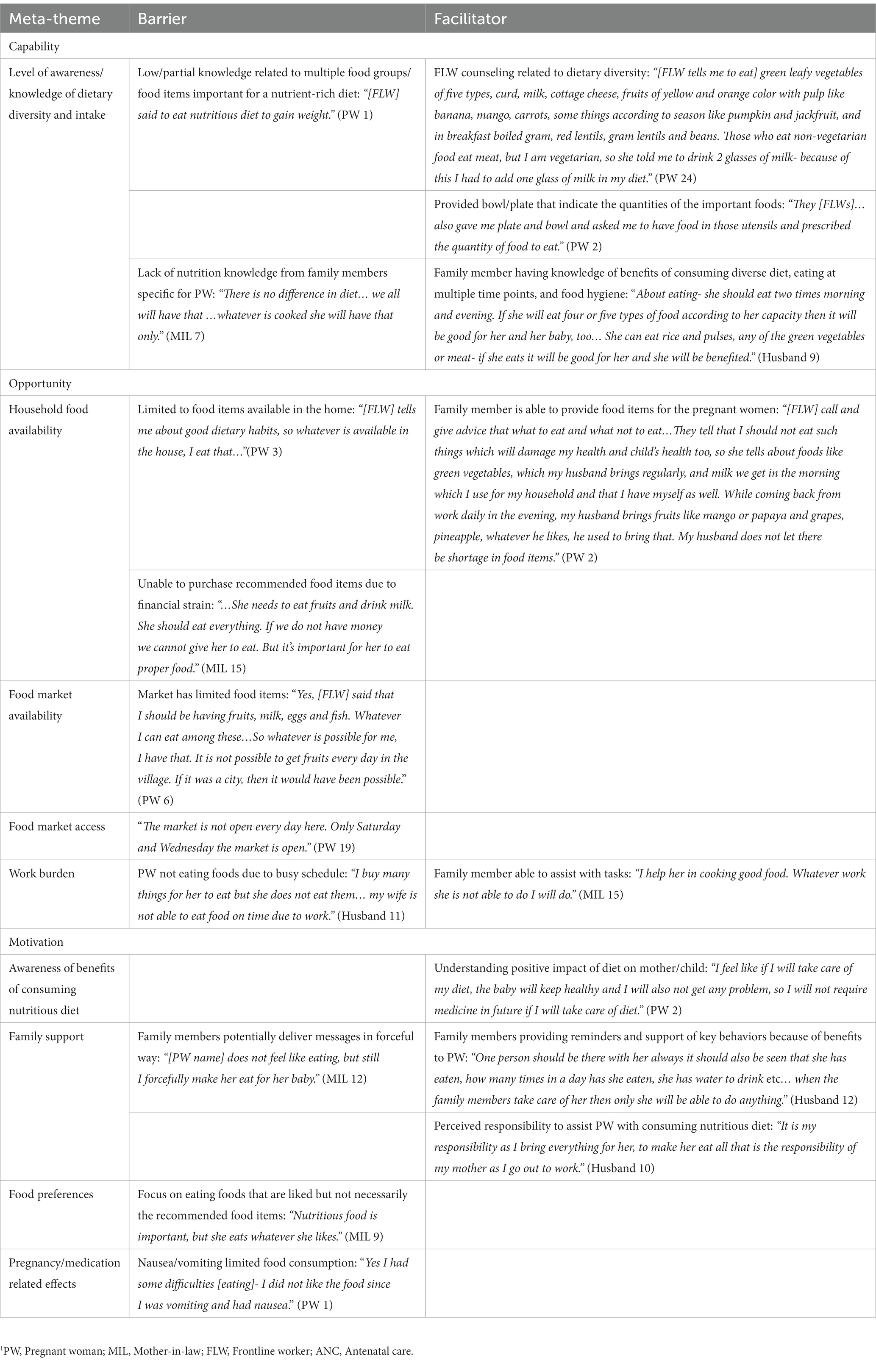

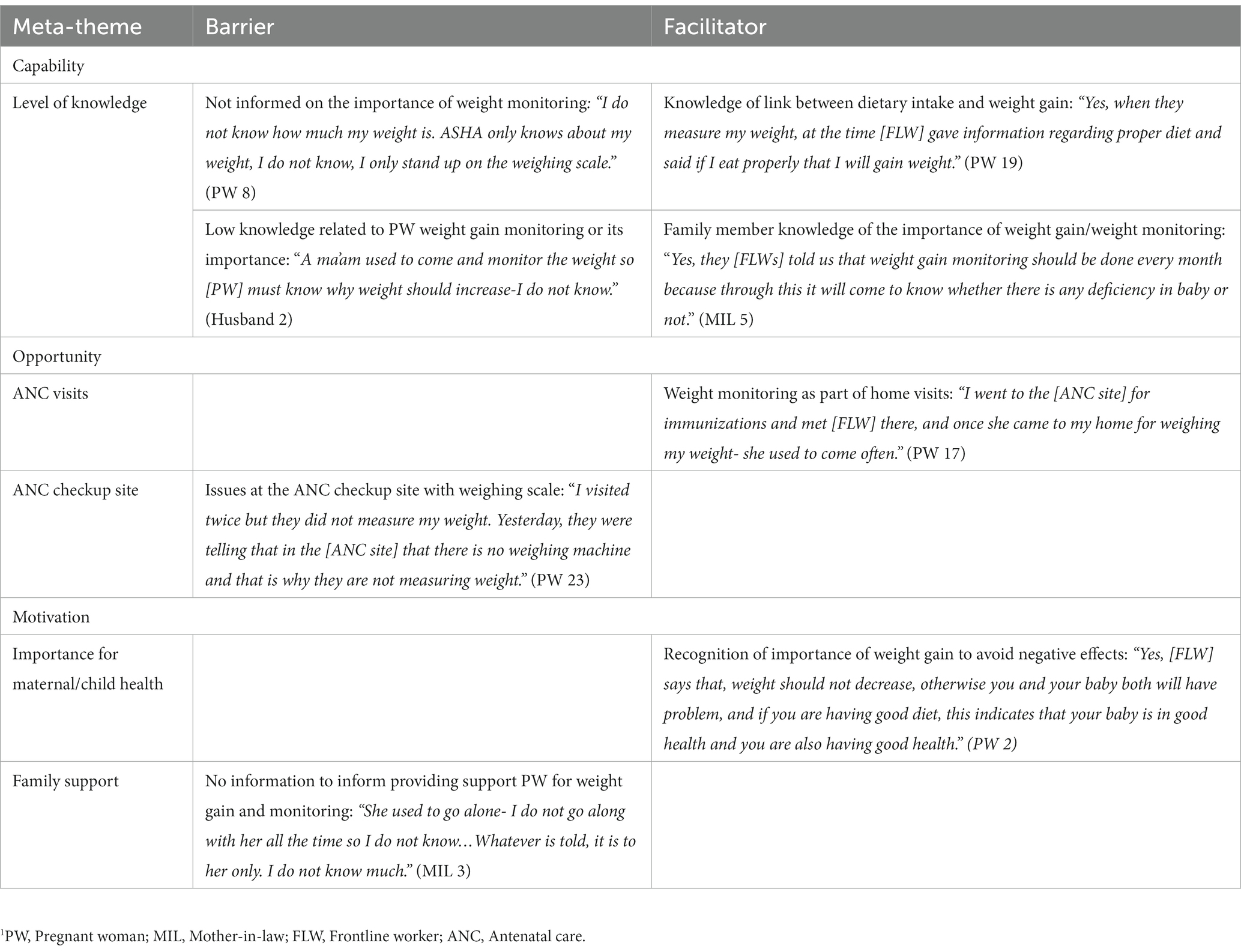

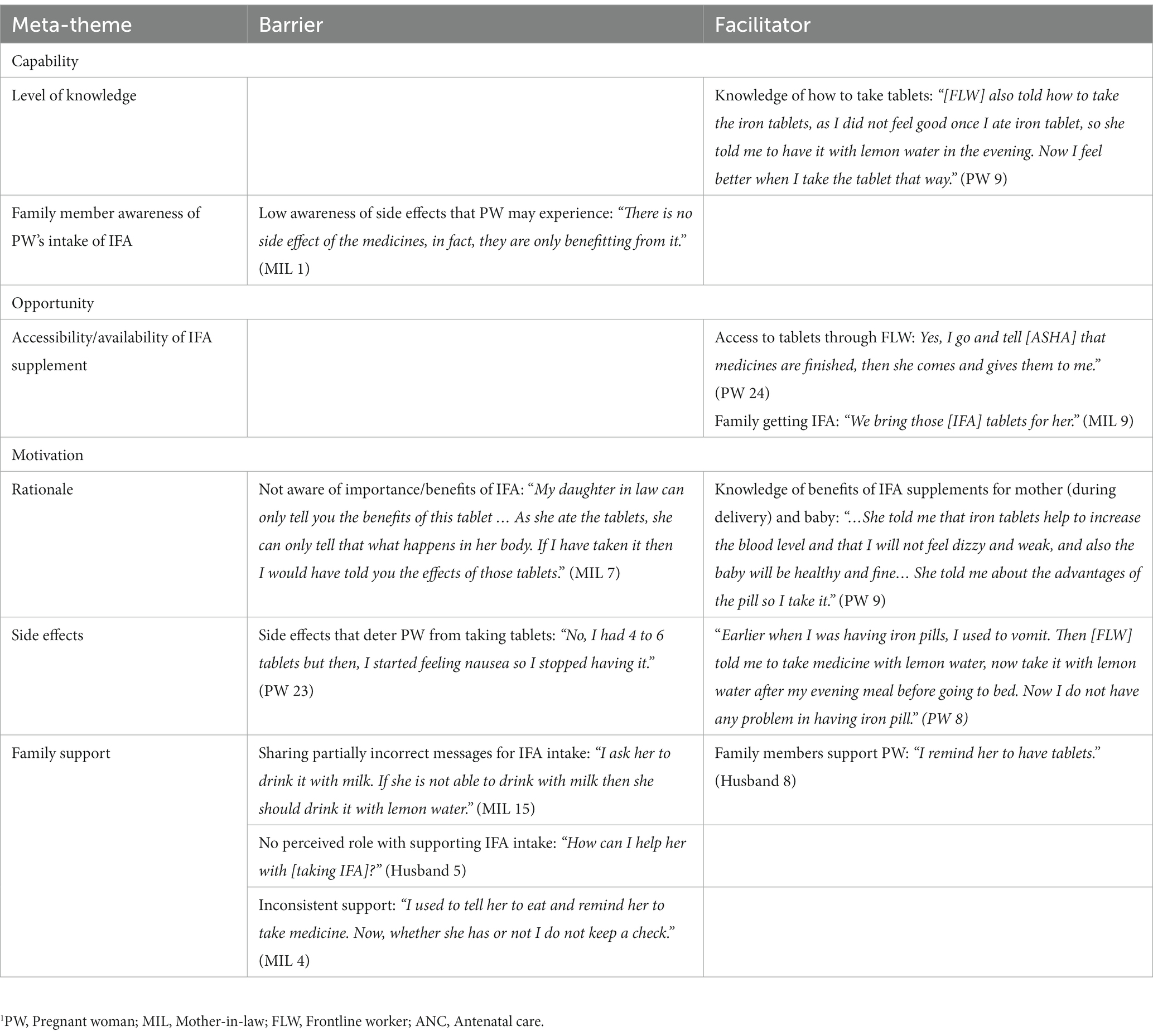

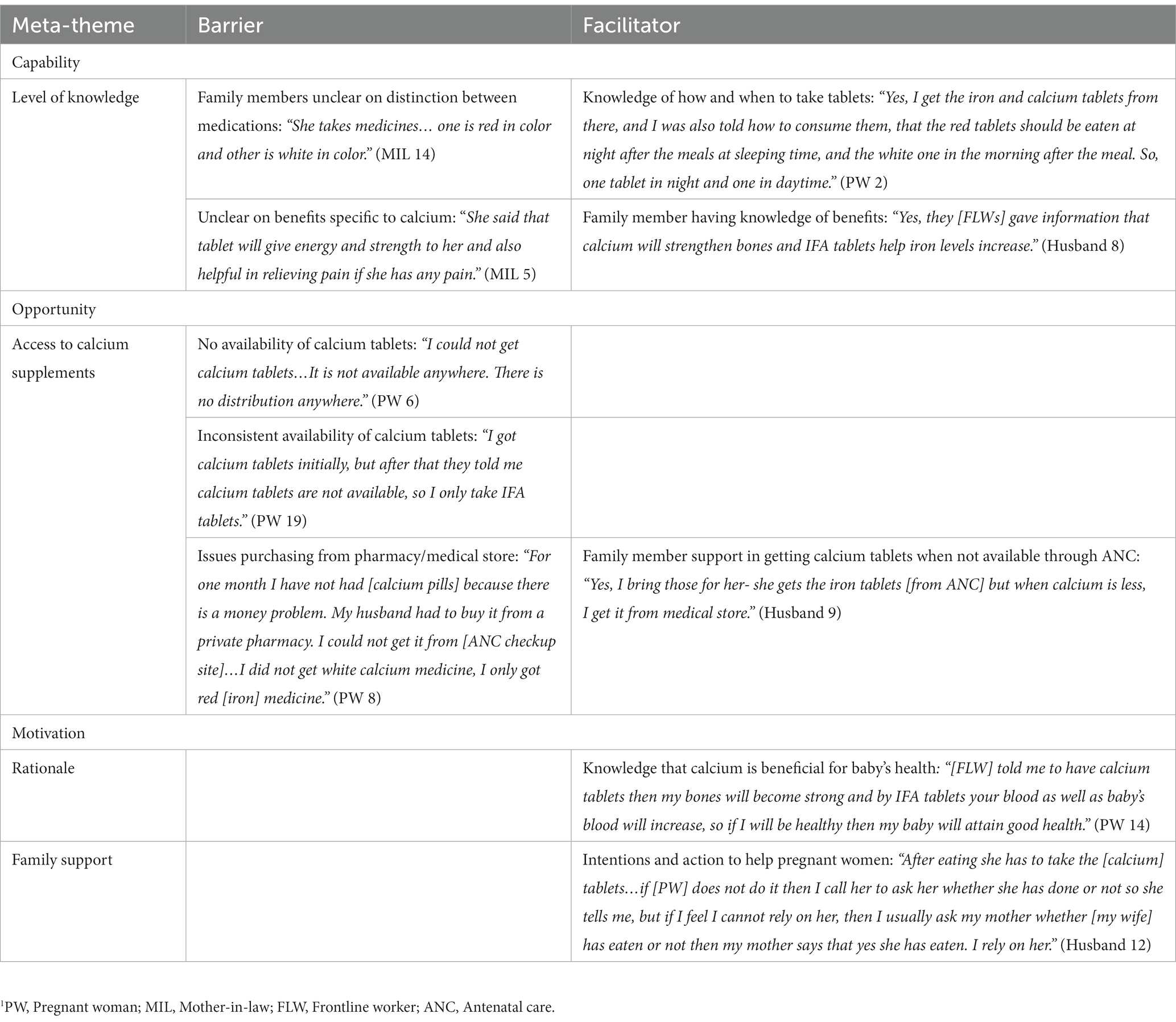

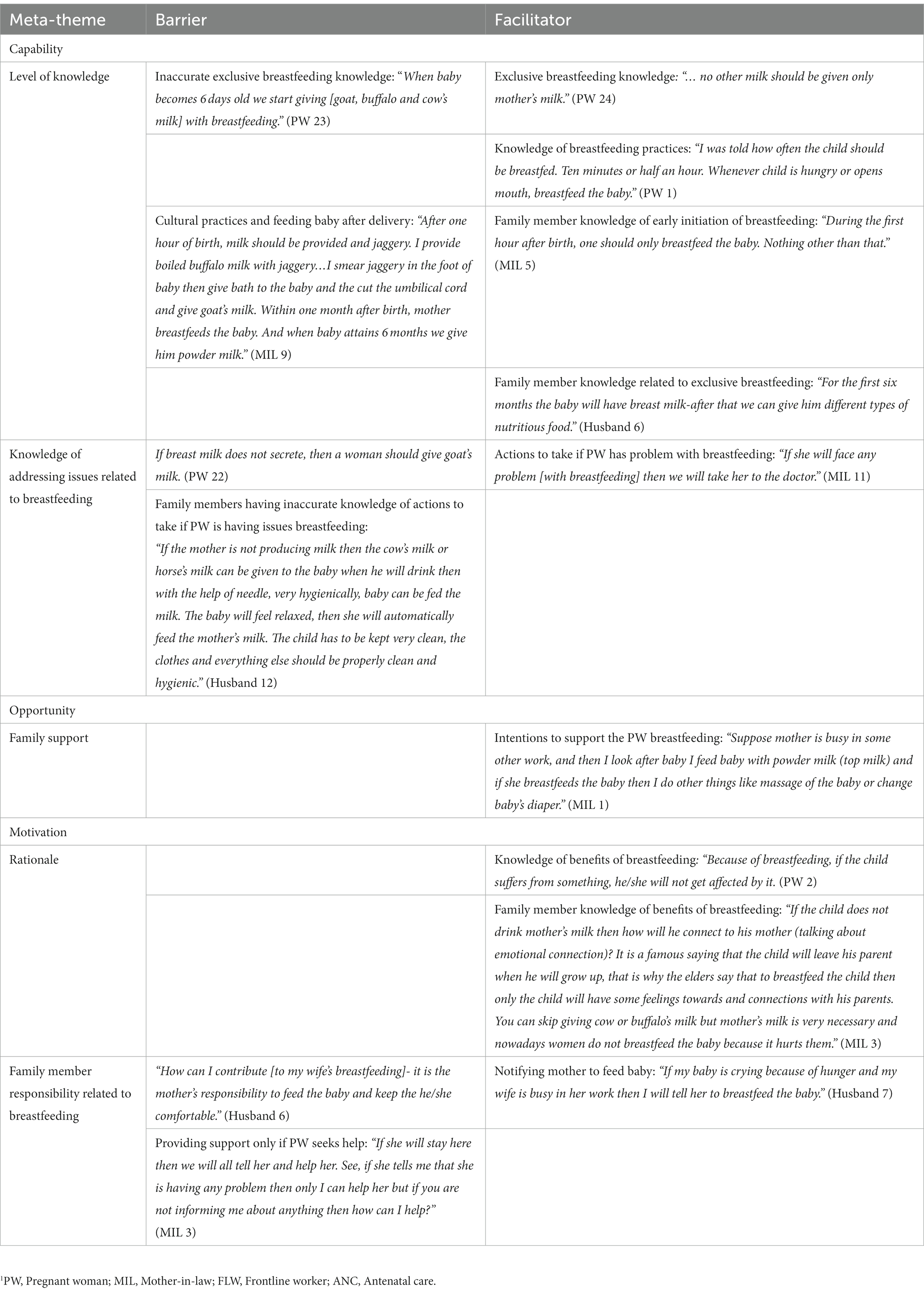

The COM components for each indicator are described in detail below, with overarching themes highlighted in italics. For each maternal nutrition behavior, key themes and supportive quotes for the identified facilitators and barriers within each indicator are summarized in Tables 1–6. There were no notable differences in factors influencing behavior change across high vs. low- performing blocks, so results were not divided by block type. In addition, Supplementary Table 3 provides an overall subjective summary assessment of the highly variable level of intensity of facilitators and barriers for the capability, opportunity, and motivation components to help to prioritize future program improvements.

Table 1. Facilitators and barriers for antenatal care (ANC) checkup attendance1.

Table 2. Facilitators and barriers for consuming a diverse diet1.

Table 3. Facilitators and barriers for weight gain and monitoring1.

Table 4. Meta-themes and facilitators and barriers for iron folic acid supplement intake1.

Table 5. Facilitators and barriers for calcium supplement intake1.

Table 6. Facilitators and barriers for breastfeeding intentions1.

Despite women having some level of awareness and knowledge of ANC checkups, most pregnant women and family members did not report knowing the importance of early and frequent health visits during pregnancy, and instead were more likely to go for an ANC visit only if they were experiencing a health issue (Table 1). Women were aware of the ANC services offered and/or received during their past visits, including blood and urine tests, sonograms, and supplements as well as dietary and hygiene information. The family members who attended ANC checkups with their wife/ daughter-in-law were also able to recall FLW advice on key behaviors and the importance of services offered during ANC visits. Conversely, capability was lower among family members who did not accompany pregnant women to the ANC check up.

High household work burden was a barrier to attending ANC checkups. In some cases, women had family members who would help with household tasks, which mitigated this barrier to ANC checkup attendance. However, women who did not have family member support would often not go for their ANC checkups on their own. Family members who provided low levels of support placed the responsibility to support solely on the FLW. A few MILs expressed they did not accompany pregnant women to their ANC checkups either because the FLWs asked them to stay at home or the pregnant women did not directly request their support. Many husbands reported not being at home or in the village during the times when women go for the checkup. Another factor that affected opportunity for ANC checkup attendance was women’s perceptions on accessibility of ANC checkup site. Women cited that hot weather and distance from the community or primary health centers made going for checkups challenging. However, accessibility barriers were overcome for some women who shared that the FLWs provided a van or ambulance to take them to and from the health center. FLW support through home visits also emerged as an important facilitator as it allowed for pregnant women to continue with their daily work routine and responsibilities and prevented them from discomfort typically experienced en route to the ANC site.

Overall, there was low reported motivation for attending ANC checkups among pregnant women. Women shared they were likely to go for a checkup if they were facing a health issue that they felt required immediate attention, or if a FLW instructed them to go that day and offered to either accompany them or provide the transportation for them to do so. Another key facilitator included home visits from FLWs, as they reminded women to attend their checkups. In contrast, infrequent FLW visits resulted in missed checkups during pregnancy.

A key contributing factor to the rationale- or reason that facilitated the ANC checkup attendance- included pregnant women and/or their family members having awareness of the need and importance of ANC visits. For women who had been to the ANC site before, their past experience with ANC checkups also influenced the motivation to attend visits. Women expressed that long waiting times and crowding during checkups, lack of respect from health care professionals, and commute discomfort all decreased their motivation for attending future checkups.

Among the participants there was a high overall awareness and knowledge of dietary diversity recommendations during pregnancy (Table 2). Both pregnant women and family members acknowledged the importance of a nutritious diet for the health of the mother and child. The majority were able to note specific food items that should be consumed during pregnancy, but only a few mentioned multiple food groups such as dark green leafy vegetables, grains, pulses, etc. However, a challenge women faced in meeting these recommendations was lack of knowledge surrounding substitute or alternative foods of similar nutritional value that could be consumed when they cannot eat the recommended items due to seasonal availability, dietary restrictions (i.e., do not consume any meat or eggs), or cost. Additionally, some of the women reported not knowing the quantity of food they should consume, unless they received the bowl or plate for measuring while they were learning about dietary intake.

The opportunity for pregnant women consume a diverse diet during pregnancy was influenced by household food availability, and local food market affordability, availability, and access. Women and family members frequently reported that financial constraints restricted their ability to purchase certain foods. A key complaint that some women had was that their markets had limited food items or that the market was difficult to access (not open every day; travel limitations for women). Women reported that family members, in particular husbands, were primarily responsible for purchasing foods from the market, and if husbands were aware of the nutritious food items, they would buy foods consistent with the FLW dietary recommendations. Women also discussed that high work burden- particularly taking care of household responsibilities and caring for children- prevented them from eating properly or missing meals.

Motivation to consume a nutritious diet was primarily driven by perceptions of the benefits of consuming a nutritious diet and belief that eating a proper diet will have a positive impact on the mother and child. Family support was also a strong motivator where family members provided reminders and encouragement for the pregnant woman to eat the recommended foods when they felt the behavior would have a positive impact on the child. There were mixed perceptions on roles and responsibilities within household on maternal diet; in some households the burden was placed solely on the pregnant woman, while in other households the husband and MIL felt the responsibility for ensuring a healthy diet. However, in some cases, the family member’s concern for the health of the mother and baby was conveyed negatively through scolding and reprimanding. In addition, individual barriers such as food preferences (likes and dislikes) and nausea were barriers to women meeting dietary recommendations.

There were mixed levels of knowledge reported on weight gain during pregnancy (Table 3). Few women knew their current weight and how much weight they should gain during pregnancy. Women typically shared that FLWs informed them on how often they should get their weight checked. Some women were told they should be gaining weight, but did not know why this is important or how to meet weight gain recommendations through diet. One misperception that pregnant women expressed was that there were potential negative implications of her weight gain on the child’s health because additional weight would put pressure on the baby.

Most family members reported not knowing why weight should be monitored during pregnancy. However, the family members who accompanied women to ANC checkups were aware of recommendations and were able to share the importance of increased food consumption and diversity to gain weight during pregnancy.

Some women were weighed at the ANC checkup sites while others were weighed during home visits which mitigated any issues related to getting to the ANC site. However, weight monitoring was intermittent as women did not go frequently for their checkups, or there was inconsistency with the function of the site’s weighing scale during their ANC visits. Weight monitoring was often a missed opportunity to talk about nutrition-related topics as most women who were weighed reported simply having their weight taken without any further discussion.

Data related to the motivation toward weight gain/weight monitoring was not salient. Although there were a few pregnant women, husbands, and MILs who recognized the importance of weight gain for maternal/child health, it was not clear whether it was a driving factor that influenced their attention toward weight gain through the pregnancy period. Family support was limited as family members did not discuss any role or responsibility to help pregnant women to gain and monitor their weight.

Pregnant women’s capability level related to IFA supplements (Table 4) was high overall with their knowledge surrounding intake, specifically the time of day for taking the tablets, how to consume them to minimize side effects, and the importance of IFA for her own health as well as for her child. However, only a few women were able to share the specific benefits of taking IFA supplements during pregnancy. Some family members – particularly MILs- had an understanding that consuming IFA was important and were generally aware of whether or not the pregnant woman was taking IFA, so they were more likely to provide support for her IFA consumption. Husbands’ awareness involved knowing where the tablets were distributed, and that the doctor or FLW was the person who held the knowledge related to consumption. However, husbands did not see themselves having any role with supporting women to take IFA. Only a few family members had knowledge related to the tablets themselves and the associated side effects, so majority believed women were not experiencing any issues with consumption. Additionally, there was conflicting knowledge related to the best practices advised by family members versus FLWs. For instance, some family members said to take tablets with milk instead of with lemon water, as recommended.

Since all pregnant women were provided the tablets either through home visits or during their visit to the ANC checkup site, there were no noted barriers to IFA access or availability for opportunity. Supply and access to the tablets were not an issue with IFA among participants.

Knowledge of anemia and its effects, as well as the benefits of consuming IFA for the body and her baby facilitated and motivated pregnant women to consume IFA. However, physical discomfort associated with taking the tablets negatively affected motivation for some women to take IFA. Women who took the supplements reported that feeling nauseated or flushed around the time of taking the tablets interrupted the consistency of their consumption. Reminding the pregnant woman to take the tablets, as well as bringing her a beverage to help consume the tablets, were examples of how family members provided support. However, not all family members were noted playing a role in her IFA intake regularly or accurately.

While there was some accurate knowledge shared in interviews when discussing calcium intake, the overall level of knowledge was not consistent amongst participants (Table 5). While most pregnant women were able to recall aspects like timing of day for consumption, how to take the tablets, or the importance of taking these tablets, this was not the case for family members. Family members had limited awareness of calcium supplements and pregnant women’s intake of these tablets. Often, husbands and MILs had difficulties in differentiating between iron and calcium tablets. When some family members were asked about calcium, they would refer to consumption of other medicines or the supplement, which made it unclear whether their information applied to calcium supplement or other tablets.

Opportunity emerged as a key determinant of calcium intake due to inconsistent availability and provision of calcium tablets in health care facilities, which resulted in the need for women or family members to purchase them from pharmacies or medical stores. Since calcium tablets were not provided at the time of the ANC visit, not having financial means to buy the tablets emerged as a barrier for calcium supplement access and therefore calcium intake.

Women who had a general understanding of the importance of calcium intake to benefit her and her baby reported consuming the tablets when they had access to them. Family support was low as their was limited understanding of the importance of consuming calcium supplements. Although two husbands with high involvement shared that they tried to remain involved in monitoring their wives’ frequency of intake, this was not noted in any of the other interviews. The support that MILs mentioned providing was general encouragement to take supplements, but this was not specific to calcium.

The timing of messages related to breastfeeding practices was a key determinant of breastfeeding capability (Table 6). Although women were in the 7th or 8th month of pregnancy, one-third of women had low level of knowledge as they did not receive any breastfeeding counseling. Women’s knowledge primarily consisted of time intervals for feeding and frequency of breastfeeding. While most women knew exclusive breastfeeding should continue for 6 months after birth, a few women mentioned that babies could have water, other types of milk, and foods during that period. Similarly, family members mentioned offering the baby cow’s (or another animal’s) milk, jaggery (sweetener derived from sugar cane), honey, and other liquids or foods early on after the baby’s birth, which are culturally informed practices but interfere with exclusive breastfeeding. Additionally, some women and family members felt that other forms of milk were acceptable as an alternative to breastmilk if the pregnant woman was having issues breastfeeding. Level of knowledge about early initiation of breastfeeding varied among husbands and MILs. Some family members had knowledge of the time frame for exclusive breastfeeding and mentioned the benefits breastfeeding has for both the baby and the mother. Family members also expressed confusion when asked about how the baby should be fed when he or she becomes sick. Women who had given birth in the past shared that they received information related to early initiation of breastfeeding at the community health center, revealing that institutional delivery was also a point of time to receive accurate information on breastfeeding. Related to knowledge of providing support while the mother is breastfeeding, a few family members mentioned they would help to improve the woman’s diet as they accurately associated quality of diet as a way to provide support related to breastfeeding.

Information related to breastfeeding opportunity was limited given that women and their family members were interviewed during the pregnancy period and not after delivery when breastfeeding would begin, so responses highlighted potential aspects of opportunity. While most husbands’ interviews did not reveal information on how they could provide support his wife while she is breastfeeding, MILs anticipated difficulties and were able to identify various reasons where the mother may have problems, such as the baby excessively crying, painful breasts, and other issues that may require treatment. Although most husbands and MILs said that the mother is primarily responsible for breastfeeding, a few MILs and one husband mentioned they would help the pregnant woman with tasks to give her time to breastfeed.

The benefits of breastfeeding (i.e., improving the baby’s development) were mentioned by some women, husbands, and MILs. Husbands had limited knowledge of breastfeeding, and most did not perceive any role to support their wives, viewing this practice as solely a women’s role. However, few husbands and MILs mentioned waking the mother up if she is asleep and letting her know that the baby is crying as ways to support breastfeeding.

Our qualitative study explored the facilitators and barriers that contribute to the capability, opportunity, and motivation to adopt key maternal nutrition behaviors, including: diet diversity, ANC checkup attendance, weight gain and weight gain monitoring, IFA supplement intake, and calcium supplement intake, as well as the intention to breastfeed after delivery in Uttar Pradesh. The level of capability, opportunity, and motivation present varied across the six promoted maternal nutrition behaviors. Overall, the findings demonstrated the following: ANC checkup attendance was low in motivation due to the lack of understanding of the importance for going to checkups routinely during pregnancy. Participants described key drivers that make it more favorable for pregnant women to adopt the recommended nutrition behaviors, such as having an ambulance take women for their ANC visit to counter transportation and accessibility issues, FLWs conducting home visits that allow for women to continue with daily responsibilities and still receive health advice, and family members providing encouragement and logistical support necessary for her to follow FLW advice. While capability did not appear to be a limiting factor for dietary diversity/ intake, many structural issues (financial strain, high food costs, limited food availability in markets, and accessibility) affected opportunity and inhibited behavioral change. Both facilitator and barriers were present in capability and opportunity for weight gain/ weight monitoring, but motivation was lacking. While there were no reported issues with getting IFA tablets, lack of opportunity was the largest barrier for calcium supplement intake due to supplement shortages. Breastfeeding capability was a key limiting factor with many women reporting inaccurate messages and misperceptions. This research provides insight into the overall key maternal nutrition intervention results and suboptimal practices previously reported in this population (12, 23).

The COM-B model has been widely used to identify where attention and efforts are necessary within a behavior intervention to improve implementation and effectiveness (13, 15, 20, 21, 24). The Health Belief Model (25), the Transtheoretical Model (26), and the Theory of Planned Behavior Model (27) are also commonly cited health behavioral change models to used explain underlying determinants of behavioral adoption, decision-making, and outcomes. The Health Belief Model looks at an individual’s perceived susceptibility of a health risk or illness, and the perceived benefits and barriers of practicing a health behavior, but it overlooks the influence of an individual’s environment and operates on the assumption that individuals have the same information to move forward with a behavior. While the Transtheoretical Model is able to capture the stages of decision-making to ultimately create behavior change, it is designed with the assumption that the thought process is linear, and is also unable to reflect the role that contextual factors (such as socioeconomic status) have in the ability for individuals to follow through on the behavior of focus. The Theory of Planned Behavior takes beliefs, intentions, and an individual’s ability into consideration, as well as the influence of social norms, on completing a behavior, but it does not take into account an individual’s opportunity or if they have the necessary resources to do so. As the COM-B framework (13) encompasses the contextual factors, contributors to decision-making, and notes the interactive components that play a role in behaviors, it was a valuable tool to help identify factors that contribute to maternal nutrition practices through the three distinct dimensions of behavior change: capability, opportunity, and motivation. Defining the facilitators and barriers for each behavior within the three dimensions deepened our understanding of important individual, interpersonal, and contextual considerations essential to maternal nutrition practices during pregnancy and for guiding future improvements in program implementation.

Capability was a critical first step for enabling maternal nutrition behavior change. Among the key behaviors, capability was particularly notable for both pregnant women and family members in relation to consuming a diverse diet. Women and family members shared their knowledge of food items that are beneficial for the mother to consume during pregnancy, which is important for informing decision-making related to daily dietary intake (28). Customization of messages by FLWs to ensure guidance both met nutritional needs and considered what was locally available at the market or in season was important. Similarly, women had shared accurate knowledge when discussing IFA supplement intake and did not have difficulty reporting the importance of taking the supplement, the time of day to take it, and ways to reduce side effects; these are key aspects that underlie the consistent IFA intake that are necessary for its effectiveness (29). Capability around breastfeeding was low among participants in this study compared to the other behaviors. Interviews were conducted during pregnancy and many women had not yet received breastfeeding counseling. Receiving counseling messages at or close to birth rather than during the ANC period is a missed opportunity and many studies have demonstrated the importance of both time periods for effective behavior change (3, 30). Late ANC checkups result in less than four ANC checkups during the pregnancy period, and have implications on other key behaviors; women not only miss counseling related to key behaviors, but are also unable to take IFA for at least 180 days as recommended by the World Health Organization. Studies conducted in Uttar Pradesh as well as other parts of India suggest that maternal knowledge contributes to higher self-efficacy and increased likelihood of breastfeeding, but cultural practices that are believed to benefit the infant (i.e., feeding jaggery within hours of birth) are contradictory to correct practices and are encouraged by MILs (10, 31). As MILs tend to be the authoritative female in the house with say in nutritional practices and decision-making, it is essential for them to be actively engaged when these practices are discussed (11).

However, capability did not guarantee that all pregnant women adopted these behaviors, as seen when examining the opportunity dimension. When looking at opportunity of consuming a diverse diet, the level of knowledge shared for consuming a diverse diet was only a facilitator when women had the ability to obtain those foods. Participants mentioned that seasonality, food availability in the market, and food affordability were barriers they encountered when trying to follow the dietary advice provided. These key barriers are consistent with other states within India and various LMICs, and limit the likelihood of women meeting minimum diet diversity (32–35). Men primarily made purchases and money-related decisions and some husbands mentioned how they used their nutrition knowledge to purchase foods that benefitted the wife’s health during pregnancy when finances allowed. Most women in this study understood the importance of IFA and did not report issues in obtaining IFA, which contrasts with findings in prior literature in Africa and Southeast Asia that has reported limited knowledge on the importance of taking IFA supplements, supply chain issues, and lack of receipt of IFA during pregnancy (36, 37). Conversely, in this study, calcium supplement intake was significantly hindered due to limited access to calcium tablets and required more steps (i.e., going to the medical store to purchase tablets) that further decreased likelihood of consumption, resulting in disruption or inability of consistent intake. Early and frequent ANC visits provided a critical opportunity for counseling and receipt of services for several of the maternal nutrition indicators (receiving advice on nutritious foods and diverse diet important for the baby, having weight checked, obtaining supplements, etc.) all of which have the potential to impact birth outcomes (38). The opportunity to attend ANC checkups was dependent on family support and has been reported in prior literature (39).

Motivation was a limiting factor across maternal nutrition indicators. Overall, both individual and family member capability were influential on motivation for behavior change. Specifically, motivation was found to be an important component with supplement intake, and knowledge of the benefits to the mother and child of taking the supplements contributed to their intentions to take the tablets. The knowledge of benefits to the mother and child, as well as prevention of anemia, were key drivers for IFA supplement intake, so having FLWs emphasize those aspects during counseling is crucial (40). Family members who provided reminders for women to take tablets contributed to supplement consumption, as noted in other studies (41). Limited motivation related to weight gain may have been related to inconsistencies in understanding the importance of weight gain over the pregnancy period and to the quality (or lack) of counseling (42).

One strength of this study was the analysis of the data through the COM-B framework alongside the involvement of different family members, which allowed for holistic understanding the family dynamic influence and the important contextual factors that surround each of the maternal nutrition indicators. Additionally, the qualitative analysis process involved two researchers coding independently initially before coming together to develop the codebook and ensured intercoder consistency. The interview guides also covered a variety of topics, which provided specific insights on numerous aspects of the household level. However, this also restricted the ability to ask multiple questions about one or two indicators in order to avoid participant fatigue. In exploring the capability aspect, the nature of the questions regarding key messages from FLWs was partially dependent on the level of recall by each pregnant woman and family members. In turn, the information shared may not be an accurate representation of the information provided during the visits. When researchers asked questions about their interactions with the FLWs, and whether or not they were told or instructed to help them with the performance of key behaviors, many women could have been worried about implications of giving an honest response, i.e., getting the FLWs in trouble, which may have resulted in sharing limited details when responding to the questions about their interactions with them. Additionally, social desirability bias was a potential limitation. Since the interviews were conducted in the pregnant women’s household, potential for others to overhear what the participant was sharing, or have a family member walk in during the interview also may have been a concern when talking about herself and her family.

In order to get a clearer picture of all factors that influence and underlie the adoption of behaviors, it is essential to combine insights from the pregnant woman, husband, MIL, and/or other key actors who play a role in the process. For example, previous studies have shown that looking at FLWs and pregnant women perspective side by side can reveal inconsistencies that can clarify some of the barriers reported among the pregnant women (43). Thus, considering a holistic analysis can reveal the significance and the weight of the facilitators and barriers that emerged during the interviews with the pregnant women, and inform how the household unit acts on recommendations of key behaviors.

This study focused only on the husband and MIL, but some of the pregnant women responded that other family members, like the sister-in-law, provided important support that differed from the husband and MIL, since she was often of the same or similar age, and in some households, also pregnant. Involving more family members can enhance the behavioral adoption process for the pregnant women, and also shift the way in which support is provided within the household. Future research can also be done to understand how programs similar to this have a direct influence on family member’s behaviors and practices. Since husbands and MILs are socially viewed as authoritative figures, considering the influence from an equivalent peer could be explored further. Using a behavior change theory during programmatic development and analysis can allow for an in-depth understanding of the reasons behind decision-making, and the role of socio-contextual components during the behavior adoption period (44). This study only applied a portion of the framework developed by Michie et al. (13) but next steps could include understanding all the factors that are included in the behavior wheel such as policy level influence.

Our qualitative study, using the components of the COM-B framework, provided novel insight into the key facilitators and barriers that affect the practice of key maternal nutrition behaviors: diet diversity, ANC checkup attendance, weight gain monitoring, and IFA and calcium supplement intake within the context of a large ongoing maternal nutrition intervention in Uttar Pradesh. Our family centric approach provides a unique and more complete look at the household level. Information will contribute to implementing targeted and comprehensive programmatic actions to improve the implementation of maternal nutrition interventions in the region.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The Emory Institutional Review Board (IRB00111064) in USA and Suraksha Independent Ethics Committee (SIEC) in India approved study protocols. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

MY, NJ, NP, SK, and PN designed the research, under the mentorship of PN, MY, DC, and SK. NJ led the interviews with the pregnant women and their husbands and had primary responsibility for the final content. NP led the interviews with the mothers-in-law. NJ and NP analyzed the data. MY, NJ, NP, SK, DC, and PN aided in interpretation of data and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (through Alive & Thrive, managed by FHI Solutions) and Emory University.

We are grateful for all the participants in this study for taking time to share their thoughts and experiences. Additionally, we thank Pravesh Dwivedi, and the local research assistant team: Sandhya Kukreti, Aparna Pandey, and Akansha Tripathi, for their support in data collection, transcribing, and translating the interviews, as well as the field workers and staff that assisted us throughout the process. We appreciate the support from International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Alive & Thrive, IPE Global, and the Government of India.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1185696/full#supplementary-material

ANC, Antenatal care; COM-B, Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behavior framework; FLW, Frontline worker; IFA, Iron and folic Acid; MIL, Mother in-law.

1. Victora, CG, Christian, P, Vidaletti, LP, Gatica-Domínguez, G, Menon, P, and Black, RE. Revisiting maternal and child undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries: variable progress towards an unfinished agenda. Lancet. (2021) 397:1388–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00394-9

2. Young, MF, Oaks, BM, Tandon, S, Martorell, R, Dewey, KG, and Wendt, AS. Maternal hemoglobin concentrations across pregnancy and maternal and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2019) 1450:47–68. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14093

3. Keats, EC, Das, JK, Salam, RA, Lassi, ZS, Imdad, A, Black, RE, et al. Effective interventions to address maternal and child malnutrition: an update of the evidence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2021) 5:367–84. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30274-1

4. Nguyen, PH, Avula, R, Tran, LM, Sethi, V, Kumar, A, Baswal, D, et al. Missed opportunities for delivering nutrition interventions in first 1000 days of life in India: insights from the National Family Health Survey, 2006 and 2016. BMJ Health. (2021) 6:e003717. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003717

5. India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Malnutrition Collaborators. The burden of child and maternal malnutrition and trends in its indicators in the states of India: the global burden of disease study 1990-2017. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2019) 3:855–70. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30273-1

6. International Institute for Population Sciences, ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India. Mumbai, India: IIPS (2021).

7. Kavle, JA, and Landry, M. Addressing barriers to maternal nutrition in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence and programme implications. Matern Child Nutr. (2018) 14:e12508. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12508

8. Simkhada, B, Porter, MA, and van Teijlingen, ER. The role of mothers-in-law in antenatal care decision-making in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2010) 10:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-34

9. Jejeebhoy, SJ. Convergence and divergence in spouses' perspectives on women's autonomy in rural India. Stud Fam Plan. (2002) 33:299–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00299.x

10. Sultania, P, Agrawal, NR, Rani, A, Dharel, D, Charles, R, and Dudani, R. Breastfeeding knowledge and behavior among women visiting a tertiary care center in India: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Glob Health. (2019) 85:64. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2093

11. Negin, J, Coffman, J, Vizintin, P, and Raynes-Greenow, C. The influence of grandmothers on breastfeeding rates: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:91. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0880-5

12. Nguyen, PH, Kachwaha, S, Tran, LM, Avula, R, Young, MF, Ghosh, S, et al. Strengthening nutrition interventions in antenatal care services affects dietary intake, micronutrient intake, gestational weight gain, and breastfeeding in Uttar Pradesh, India: results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation. J Nutr. (2021) 151:2282–95. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab131

13. Michie, S, van Stralen, MM, and West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. (2011) 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

14. Knighton, SC, Richmond, M, Zabarsky, T, Dolansky, M, Rai, H, and Donskey, CJ. Patients' capability, opportunity, motivation, and perception of inpatient hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. (2020) 48:157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.09.001

15. Gibson Miller, J, Hartman, TK, Levita, L, Martinez, AP, Mason, L, McBride, O, et al. Capability, opportunity, and motivation to enact hygienic practices in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United Kingdom. Br J Health Psychol. (2020) 25:856–64. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12426

16. Malliaras, P, Merolli, M, Williams, CM, Caneiro, JP, Haines, T, and Barton, C. 'It's not hands-on therapy, so it's very limited': telehealth use and views among allied health clinicians during the coronavirus pandemic. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. (2021) 52:102340. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102340

17. West, R, Michie, S, Rubin, GJ, and Amlôt, R. Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nat Hum Behav. (2020) 4:451–9. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9

18. Olander, EK, Darwin, ZJ, Atkinson, L, Smith, DM, and Gardner, B. Beyond the 'teachable moment' - a conceptual analysis of women's perinatal behaviour change. Women Birth. (2016) 29:e67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.11.005

19. Rosenkranz, RR, Ridley, K, Guagliano, JM, and Rosenkranz, SK. Physical activity capability, opportunity, motivation and behavior in youth settings: theoretical framework to guide physical activity leader interventions. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. (2021):1–25. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2021.1904434

20. McClintic, EE, Ellis, A, Ogutu, EA, Caruso, BA, Ventura, SG, Arriola, KRJ, et al. Application of the capabilities, opportunities, motivations, and behavior (COM-B) change model to formative research for child nutrition in Western Kenya. Curr Dev Nutr. (2022) 6:nzac104. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac104

21. Russell, CG, Taki, S, Azadi, L, Campbell, KJ, Laws, R, Elliott, R, et al. A qualitative study of the infant feeding beliefs and behaviours of mothers with low educational attainment. BMC Pediatr. (2016) 16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0601-2

22. Webb Girard, A, Waugh, E, Sawyer, S, Golding, L, and Ramakrishnan, U. A scoping review of social-behaviour change techniques applied in complementary feeding interventions. Matern Child Nutr. (2020) 16:e12882. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12882

23. Kachwaha, S, Nguyen, PH, Tran, LM, Avula, R, Young, MF, Ghosh, S, et al. Specificity matters: unpacking impact pathways of individual interventions within bundled packages helps interpret the limited impacts of a maternal nutrition intervention in India. J Nutr. (2022) 152:612–29. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab390

24. Willmott, TJ, Pang, B, and Rundle-Thiele, S. Capability, opportunity, and motivation: an across contexts empirical examination of the COM-B model. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1014. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11019-w

25. Rosenstock, IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. (1974) 2:354–86. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200405

26. Prochaska, JO, and Velicer, WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. (1997) 12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

27. Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

28. Nguyen, PH, Kachwaha, S, Avula, R, Young, M, Tran, LM, Ghosh, S, et al. Maternal nutrition practices in Uttar Pradesh, India: role of key influential demand and supply factors. Matern Child Nutr. (2019) 15:e12839. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12839

29. Fite, MB, Roba, KT, Oljira, L, Tura, AK, and Yadeta, TA. Compliance with iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) and associated factors among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0249789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249789

30. Rollins, NC, Bhandari, N, Hajeebhoy, N, Horton, S, Lutter, CK, Martines, JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. (2016) 387:491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2

31. Young, MF, Nguyen, P, Kachwaha, S, Tran Mai, L, Ghosh, S, Agrawal, R, et al. It takes a village: an empirical analysis of how husbands, mothers-in-law, health workers, and mothers influence breastfeeding practices in Uttar Pradesh, India. Matern Child Nutr. (2020) 16:e12892. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12892

32. Stevens, B, Watt, K, Brimbecombe, J, Clough, A, Judd, J, and Lindsay, D. The role of seasonality on the diet and household food security of pregnant women living in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:121–9. doi: 10.1017/S136898001600183X

33. Saaka, M, Mutaru, S, and Osman, SM. Determinants of dietary diversity and its relationship with the nutritional status of pregnant women. J Nutr Sci. (2021) 10:e14. doi: 10.1017/jns.2021.6

34. Kehoe, SH, Dhurde, V, Bhaise, S, Kale, R, Kumaran, K, Gelli, A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to fruit and vegetable consumption among rural Indian women of reproductive age. Food Nutr Bull. (2019) 40:87–98. doi: 10.1177/0379572118816459

35. Girard, AW, Dzingina, C, Akogun, O, Mason, JB, and McFarland, DA. Public health interventions, barriers, and opportunities for improving maternal nutrition in Northeast Nigeria. Food Nutr Bull. (2012) 33:S51–70. doi: 10.1177/15648265120332S104

36. Lyoba, WB, Mwakatoga, JD, Festo, C, Mrema, J, and Elisaria, E. Adherence to iron-folic acid supplementation and associated factors among pregnant women in Kasulu communities in North-Western Tanzania. Int J Reprod Med. (2020) 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2020/3127245

37. Siekmans, K, Roche, M, Kung'u, JK, Desrochers, RE, and De-Regil, LM. Barriers and enablers for iron folic acid (IFA) supplementation in pregnant women. Matern Child Nutr. (2018) 14:e12532. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12532

38. Sanghvi, T, Nguyen, PH, Tharaney, M, Ghosh, S, Escobar-Alegria, J, Mahmud, Z, et al. Gaps in the implementation and uptake of maternal nutrition interventions in antenatal care services in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia and India. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13293. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13293

39. Upadhyay, P, Liabsuetrakul, T, Shrestha, AB, and Pradhan, N. Influence of family members on utilization of maternal health care services among teen and adult pregnant women in Kathmandu, Nepal: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. (2014) 11:92. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-92

40. Bianchi, CM, Huneau, JF, Le Goff, G, Verger, EO, Mariotti, F, and Gurviez, P. Concerns, attitudes, beliefs and information seeking practices with respect to nutrition-related issues: a qualitative study in French pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:306. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1078-6

41. Nguyen, PH, Sanghvi, T, Kim, SS, Tran, LM, Afsana, K, Mahmud, Z, et al. Factors influencing maternal nutrition practices in a large scale maternal, newborn and child health program in Bangladesh. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0179873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179873

42. Whitaker, KM, Wilcox, S, Liu, J, Blair, SN, and Pate, RR. Patient and provider perceptions of weight gain, physical activity, and nutrition counseling during pregnancy: a qualitative study. Womens Health Issues. (2016) 26:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.10.007

43. Martin, SL, Wawire, V, Ombunda, H, Li, T, Sklar, K, Tzehaie, H, et al. Integrating calcium supplementation into facility-based antenatal care services in Western Kenya: a qualitative process evaluation to identify implementation barriers and facilitators. Curr Dev Nutr. (2018) 2:nzy068. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzy068

44. Zongrone, AA, Menon, P, Pelto, GH, Habicht, JP, Rasmussen, KM, Constas, MA, et al. The pathways from a behavior change communication intervention to infant and young child feeding in Bangladesh are mediated and potentiated by maternal self-efficacy. J Nutr. (2018) 148:259–66. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxx048

Keywords: antenatal care checkup, breastfeeding, calcium supplement intake, maternal nutrition, diet diversity, iron and folic acid supplement intake, weight monitoring, COM-B

Citation: Jhaveri NR, Poveda NE, Kachwaha S, Comeau DL, Nguyen PH and Young MF (2023) Opportunities and barriers for maternal nutrition behavior change: an in-depth qualitative analysis of pregnant women and their families in Uttar Pradesh, India. Front. Nutr. 10:1185696. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1185696

Received: 13 March 2023; Accepted: 15 June 2023;

Published: 04 July 2023.

Edited by:

Jai Das, Aga Khan University, PakistanReviewed by:

Rehana Salam, The University of Sydney, AustraliaCopyright © 2023 Jhaveri, Poveda, Kachwaha, Comeau, Nguyen and Young. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melissa F. Young, bWVsaXNzYS55b3VuZ0BlbW9yeS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.