95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Nutr. , 06 February 2023

Sec. Food Chemistry

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.962312

This article is part of the Research Topic Selenium and Human Health View all 11 articles

Selenium (Se) is an essential element for maintaining human health. The biological effects and toxicity of Se compounds in humans are related to their chemical forms and consumption doses. In general, organic Se species, including selenoamino acids such as selenomethionine (SeMet), selenocystine (SeCys2), and Se-methylselenocysteine (MSC), could provide greater bioactivities with less toxicity compared to those inorganics including selenite (Se IV) and selenate (Se VI). Plants are vital sources of organic Se because they can accumulate inorganic Se or metabolites and store them as organic Se forms. Therefore, Se-enriched plants could be applied as human food to reduce deficiency problems and deliver health benefits. This review describes the recent studies on the enrichment of Se-containing plants in particular Se accumulation and speciation, their functional properties related to human health, and future perspectives for developing Se-enriched foods. Generally, Se’s concentration and chemical forms in plants are determined by the accumulation ability of plant species. Brassica family and cereal grains have excessive accumulation capacity and store major organic Se compounds in their cells compared to other plants. The biological properties of Se-enriched plants, including antioxidant, anti-diabetes, and anticancer activities, have significantly presented in both in vitro cell culture models and in vivo animal assays. Comparatively, fewer human clinical trials are available. Scientific investigations on the functional health properties of Se-enriched edible plants in humans are essential to achieve in-depth information supporting the value of Se-enriched food to humans.

Selenium is an essential trace element for human health. According to the World Health Organization (1), a recommended consumption level of Se is 55-70 μg day–1 for adults, with 400 μg day–1 as a toxic concentration. Selenium deficiency situation has transpired in some parts of the world, including China (about 72% of the area), Europe (e.g., France and Norway) and New Zealand (2). Selenium is associated with the normal function of glutathione protein (GSH) and its family of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) and other selenoproteins (3). The lack of Se can severely affect the human immune system (4, 5), leading to a cardiomyopathy disorder called “Keshan disease” and the bone and joint connection syndrome called “Kashin-Beck disease” (6, 7). Keshan disease occurs when vascular endothelial cells are damaged from oxidative stress due to non-functional antioxidant proteins (8). This disease also causes some serious health problems such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, myocardial necrosis and congestive heart failure (9). Kashin-Beck disease is an endemic osteoarthropathy, causing severe symptoms to joints and bone, including joint pain, elbows flexion and extension disturbances, enlarged inter-phalangeal joints, and limited joint motion (10, 11). Moreover, Se deficiency also increases the risk of arthritis, cancers, and neurodegenerative disorders regarding immune and inflammatory infections (12, 13).

In contrast to Se deficiency, there are a few high soil Se regions globally. The prominent one being the Enshi Province in China, where the soil Se content can rise to 11.4 mg Se kg–1 in the high Se area (14). People live in the high Se soil area can suffer from selenosis symptoms and abnormal growth conditions due to excessive Se consumption of foods produced from the area (6, 15). The Se intake of Enshi people was reported to reach 833 μg per day (15), with serum Se concentrations of up to 41.6 μmol L–1, approximately 20 times higher than the proposed intake (16). Chronic selenosis is a group of diseases associated with a wide range of symptoms from hair loss, bone and joint problems, and cellular damage from reactive oxygen species which increase the high risk of cancers (17, 18).

In general, toxicity associated with Se intake occurs in a few isolated areas, and food science and technology innovation can help lower Se imbalance intake in the diet. Selenium is present in plant foods in different chemical forms, including the organic Se-containing amino acids, i.e., selenomethionine (SeMet), Se-methylselenocysteine (MeSeCys), and γ-glutamyl-Se-methylselenocysteine (γ-GluMeSeCys), and the inorganic Se, i.e., selenite and selenate (19). Advanced analytical techniques are applied for identifying Se compounds in plant food samples nowadays, contributing to the knowledge of Se chemical forms present in plant foods, their content, and the safe concentration for human consumption. In developing Se-enriched food products, the aim should be focused on providing functional food products to benefit human health and enhance the quality of life. Identification of the Se chemical form and content is essential to justify the use of Se-enriched plant foods for achieving health benefits and overcoming the deficiency issues associated with this essential trace mineral. The objectives of this review are to examine the Se’s accumulation ability and speciation in a wide range of Se-enriched plant foods, to inspect Se and Se compounds’ biological effects on human health, and to explore the prospects of developing Se-enriched plant foods for health purposes.

Over the past few decades, Se-enriched plants have been developed to demote deficiency problems for those living in low Se regions who cannot maintain the recommended intake level (18). One of the most simple and robust techniques to increase Se content in plants is by growing plants in high Se soil and applying Se fertilizers. This enrichment method relates to plant species’ absorption, transformation, and accommodation ability of minerals (6). The Se accumulation ability of plants can be classified into three levels: hyper-accumulators, secondary accumulators and non-accumulators. The hyper-accumulators (e.g., Stanleya, Astragalus, Conopsis, Neptunia, Xylorhiza) can accumulate more than 1,000 mg Se kg–1 while the secondary accumulators (e.g., Brassica juncea, Brassica napus, Broccoli, Helianthus, Aster, Camelina, Medicago sativa) can accumulate between 100-1,000 mg Se kg–1. The non-accumulators only accumulate less than 100 mg Se kg–1 and most of the angiosperm species are included in this category (20–22).

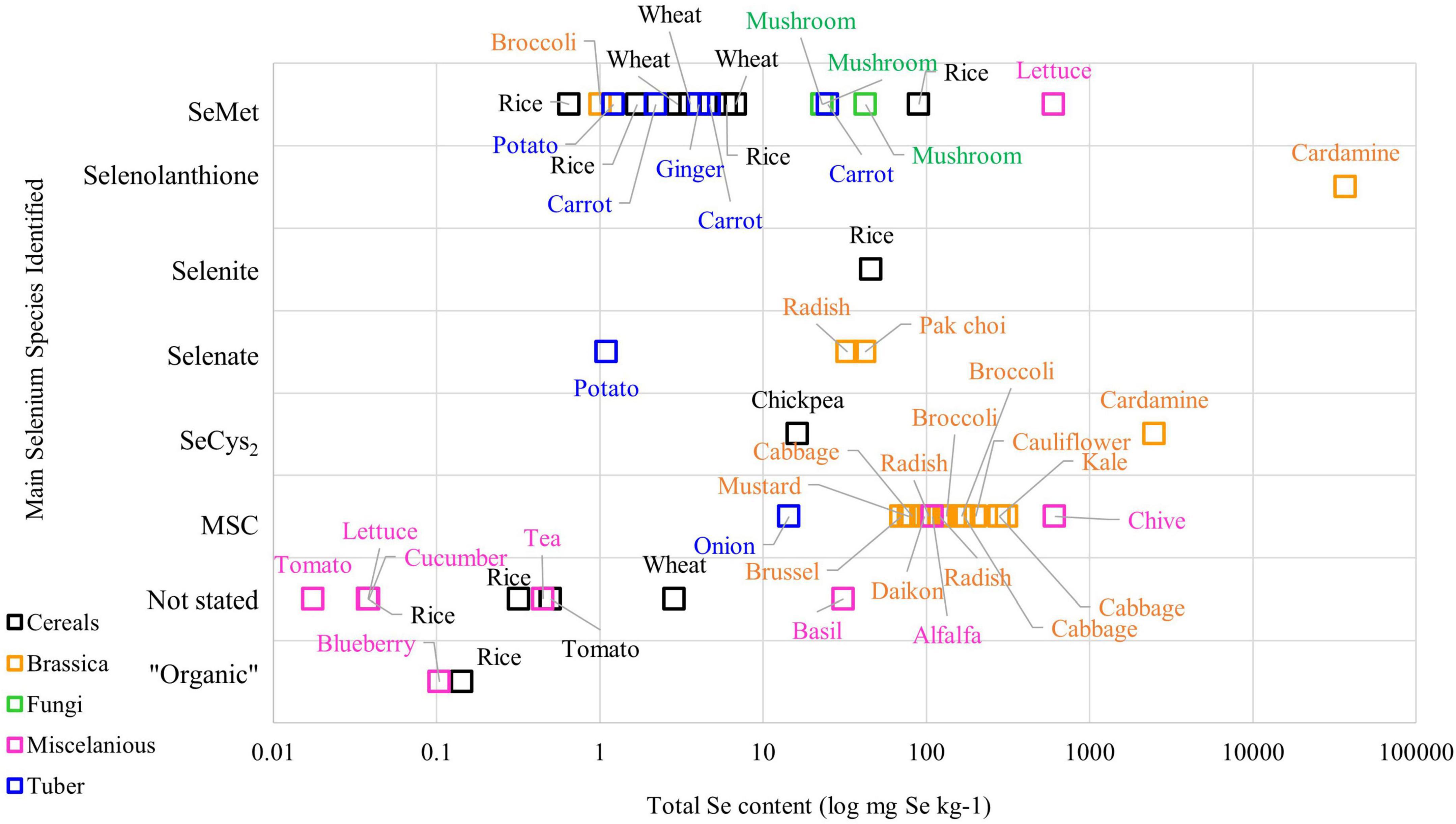

The metabolism of Se in plant species varies among plants, meaning that different plant varieties can produce different Se chemical forms in various concentrations. Figure 1 demonstrates the complexity of Se chemical forms in different plant species. Literature on Se speciation revealed that the Brassica family, such as broccoli, cabbage, and radish, have MSC as the main Se compound stored in their cells, while SeMet is the main Se chemical form found in cereals grains and tuber crops such as ginger, wheat, and carrot (23–25). On the other hand, selenolanthionine is a major water-soluble Se compound found in Cardamine violifolia (26).

Figure 1. The Se content and chemical species in plant-based foods from the literature (Please refer to Supplementary Table 1 for the original data from the literature).

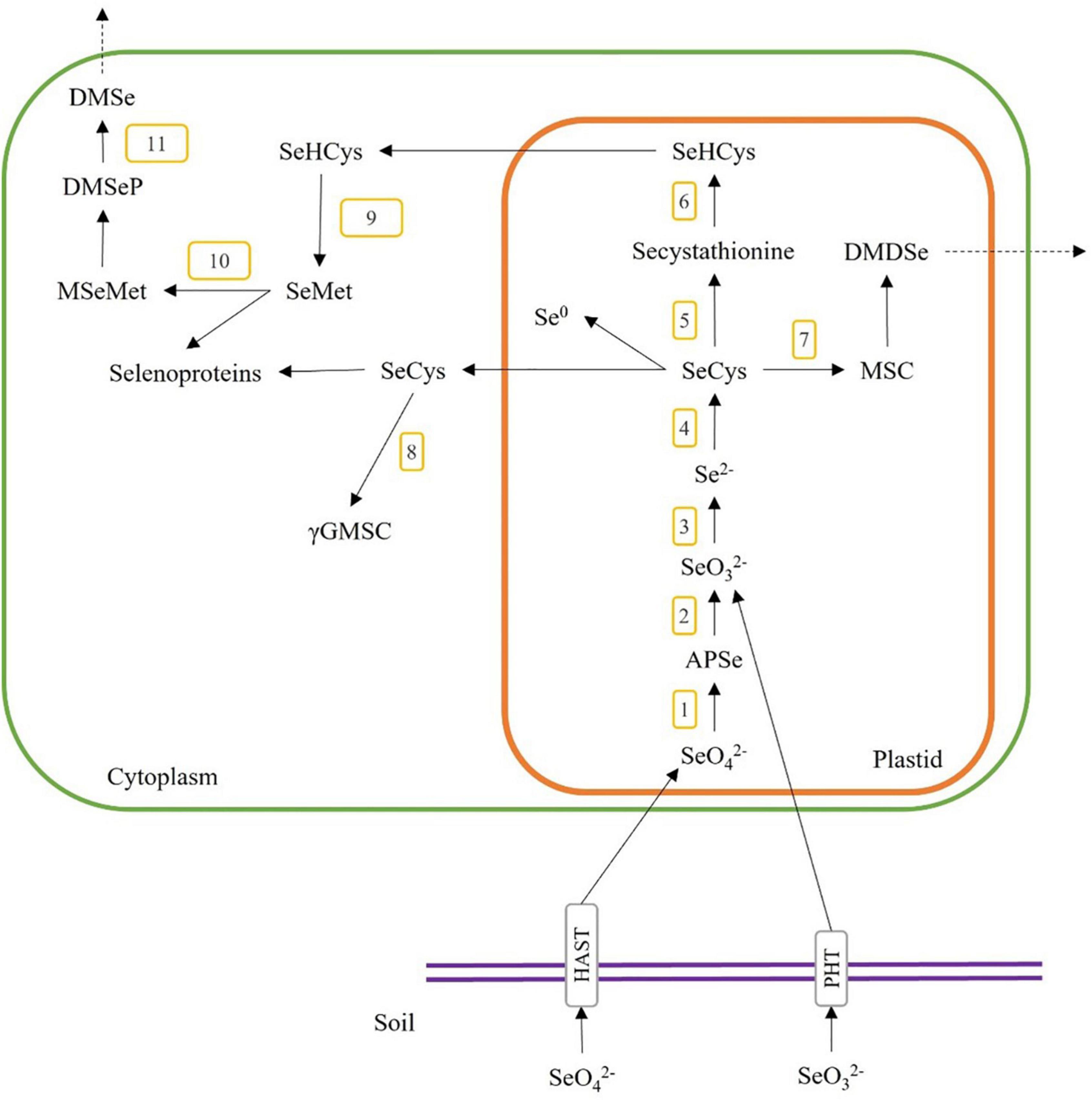

As the Se content and chemical form in plant materials are specific to the plant species and their metabolism pathways, we need to understand the Se accumulation mechanisms in the plant when selecting plant species for producing Se-enriched plant foods and food ingredients for human diets. The accumulation pathways of Se content start with the inorganic Se (i.e., selenite and selenate) in soil, which plants could uptake and transform into organic forms (i.e., selenocystine (SeCys2), selenomethionine (SeMet), selenohomocysteine, selenolanthionine Se-methylselenocysteine (MSC) and γ-glutamyl-methylselenocysteine (γGMSC)) through the metabolic pathways as shown in Figure 2. Briefly, selenate and selenite are taken through the plant root via high-affinity sulphate transporter (HAST) and high-affinity phosphate transporter (PHT). Selenate is converted to adenosine 5’-phosphoselenate (APSe) via ATP sulfurylase (Figure 2, step 1), then changed to selenite through adenosine phosphosulfate reductase (Figure 2, step 2). Selenite is reduced to selenide (Se2–) by sulphite reductase (Figure 2, step 3), and then it is transformed to selenocysteine (SeCys) by O-acetylserine thiol-lyase (Figure 2, step 4). SeCys could also be transformed to Se-cystathionine via cysthathionine-γ-synthase (Figure 2, step 5), MSC via selenocysteine-lyase (Figure 2, step 7), or elemental selenium (Se0). Secystathionine could then be changed into selenohomocysteine (SeHCys) via cysthathionine-β-lyase (Figure 2, step 6). MSC could be converted to dimethyldiselenide (DMDSe), a volatile compound and released from plant cells. SeCys is transported to the cytoplasm and is reacted with glutamic acid to form γ-glutamyl-Se-methylselenocysteine (γGMSC) by γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase (Figure 2, step 8). SeHCys can also be transported to the cytoplasm and synthesized to form selenomethionine (SeMet) by methionine synthase (Figure 2, step 9). SeMet could also be converted to methyl-selenomethionine (MSeMet) by methionine methyltransferase (Figure 2, step 10), then changed to the volatile dimethylselenoproprionate (DMSeP) and released as dimethyl-selenide (DMSe) via dimethylselenoproprionate-lyase (Figure 2, step 11) (27–29).

Figure 2. A general overview of Se uptake, metabolism, and incorporation in higher plants. The numbers 1–12 indicate the possible enzymatic steps involved in the conversion of selenite and selenate. 1, ATP sulfurylase; 2, adenosine phosphosulfate reductase; 3, sulfite reductase; 4, O-acetylserine thiol-lyase; 5, cystathionine-γ-synthase; 6, cystathionine-β-lyase; 7, selenocysteine-lyase; 8, γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase; 9, methionine synthase; 10, methionine methyltransferase; 11, dimethyl selenoproprionate-lyase; SeO, selenate; SeO, selenite; APSe, adenosine 5′-phosphoselenate; SeCys, selenocysteine; MSC, Se-methylselenocysteine; DMDSe, dimethyldiselenide; SeHCys, selenohomocysteine; Se0, elemental selenium; γGMSC, γ-glutamyl-methylselenocysteine; SeMet, selenomethionine; MSeMet, methyl-selenomethionine; DMSeP, dimethylselenoproprionate; DMSe, dimethyl selenide.

During the accumulation process, selenite tends to provide higher bioavailability than selenate, and it is commonly used as Se fertilizer for producing Se enriched plants (30, 31). Hu et al. (24) showed that using selenite as the foliar fertilizer on rice grain increased the Se concentrations in glutelin and albumin proteins as SeCys2 and SeMet. Selenite could cause significant phytotoxicity from a generation of superoxide in plant cells during a non-enzymatic reduction reaction to produce selenide (25, 32, 33). In another study, Ramkissoon et al. (34) applied sodium selenate to wheat as foliar fertilizer and found an increased Se concentration and the highly bioavailable SeMet fraction in wheat grain. However, Se can cause cytotoxicity in plants and humans when accumulated or consumed excessively. At high concentrations, Se shows cytotoxicity by either generating reactive oxygen species or malformed selenoprotein (20). Generally, inorganic Se, either selenite or selenate, generates toxicity via the activation of ROS, which inhibits the growth rate and causes lipid oxidation related to malondialdehyde formation in plant tissue (35, 36).

In contrast, organic Se, such as SeMet and SeCys, cause toxicity to plant cells by forming malformed selenoproteins due to the replacement of Cys/Met with SeCys and SeMet in the peptide chain. Changing between Cys and SeCys changes cellular protein’s structure by changing disulfide bond to diselenide bond to 60 mg Se kg–1, which affects the peptide chain’s redox potential. Moreover, SeCys is more reactive than Cys, which could increase enzyme activity and the metal binding co-factor activity of malform selenoproteins (27). Literature has shown that organic Se’s toxicity level is far less than inorganic ones because they can be capped with proteins and polysaccharides (37). Moreover, the organic Se compounds display a higher bioavailability than the inorganic Se (38). The organic Se involves in the upregulation of enzymatic antioxidant capacity which play a key role in Se tolerance (39). As the Se chemical forms significantly affect the biological activities of Se-enriched plants, it is essential to perform chemical speciation of Se compounds to gain scientific insight into the relationship between chemical forms and the functional properties of Se-enriched plant foods.

Speciation of Se compounds in Se-enriched plant foods has been studied to relate to and explain the biological activity of the products. Se can accumulate in plant organelle, stay either in free molecules form, or bound with a larger and more complex structure such as polypeptides or polysaccharides. Most inorganic Se compounds and small selenoamino acids such as selenolanthionine, γGMSC, MSC, SeCys2 and SeMet are water-soluble molecules, therefore water extraction is a common method applied to separate these small molecules from the sources. Proven in some previous studies, extraction efficiencies in hot water ranged between 47 and 91% Se in different mushroom species (40); 40% for Se-enriched mycelium (Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegl.) (41), 85% for Se-enriched garlic (42) and 60% for Cardamine violifolia (26). Multiple sample preparation steps have been used to release Se bind to some larger components in plant cell walls. For example, hydrolysis of polysaccharides using an enzyme such as cellulase, hemicellulose, β-glucanase and pectinase, has been applied to hydrolyze plant cell walls, followed by protease enzymes to release selenoamino acids (43, 44).

Selenium compounds extracted from the plants could be separated by the High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) technique, commonly used in the chemical compound analysis. Various types of chromatography resin can be used to separate the specific Se compounds in plants. For example, ion-exchange chromatography is used in the scouting period, which can classify Se chemical compounds according to their electron charge binding to ion exchange resins, either in a negatively charged resin (cation exchanger) or a positively charged resin (anion exchanger) (45, 46). Thus, ion-exchange chromatography is the technique that separates Se molecules by the positively or negatively charged groups retained on a stationary phase in equilibrium with free counter ions in the mobile phase (47). Generally, when the pH of the eluent buffer is higher than the pKa of the molecule, the compound shows a negative charge and binds to the positive charge anion exchanger (46, 48). Anion exchange liquid chromatography has a positively charged stationary phase to interact with the negatively charged Se compounds, such as selenate (pKa = 1.92), selenite (pKa = 2.46) or SeMet (pKa1 = 2.19 and pKa2 = 9.05) in the deprotonated state which can be strongly retained on anion exchange resin at pH around 5. In contrast, Se compounds with higher pKa values, such as SeCys2 (pKa ∼ 8.07 and 8.94), will be in protonating state and retained very little on anion column chromatography at pH around 5 in the mobile phase (49, 50). In contrast, cation exchange chromatography works similarly to anion exchange, except that the stationary phase is negatively charged, which could interact with the positively charged Se compounds (51, 52). Furthermore, some other types of chromatography could be applied for Se compound separation. For example, size exclusion chromatography is used to separate compounds based on their particle size; reversed phase and hydrophilic interaction chromatography could be applied to separate Se compounds based on the polarity of their molecules (51). These types of chromatography can be applied simultaneously to identify different Se compounds in plant extracts.

After the chromatographic separation, the mass of Se molecules can be detected by techniques such as the Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). These techniques detect Se molecules based on their transition ions which provide high accuracy detection, low detection limit (part per trillion), and less matrix interference (53, 54). The HPLC-ICP-MS has been considered a robust workflow and is widely used for Se determination in Se-containing plants and foods. A study by Ogra et al. (55) successfully applied size-excursion chromatography incorporated with ICP-MS to identify the Se metabolic pathway of ginger and Indian mustard using selenate or SeMet as Se fertilizers. The study found that γ-Glutamyl-Se-methylselenocysteine and MSC were the common metabolites of selenate and SeMet in garlic and Indian mustard.

As mentioned earlier, the Se compounds accumulated and stored differ by plant genus/species, and some Se can be bound to highly complex structure. In addition to the methods described above, other technique can be applied to identify the Se compounds started with compound purification by ion-exchange chromatography, followed by identification of the molecular mass by Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) (26, 56, 57). The ESI-MS is a technique that ionizes chemical compounds by electrospray ionization, and a mass analyzer then detects the ionized molecules according to their mass/charge (m/z) ratio (58). This high sensitivity mass spectroscopy technique can provide effective approaches to the speciation of Se bound in complex structures such as selenosugars and selenoproteins (59, 60). Some novel analysis methods have also been used to specify Se compounds in food materials. For example, Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) is a solvent free analytical technique used to analyze Se compound in solid sample and it can provide greater accuracy results compared to traditional liquid chromatography (61). Moreover, the X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) technique was used to identify Se compounds in biological sample with less sample preparation step to prevent the degradation of Se compound from chemical reaction during sample preparation (62). These analytical techniques can be valuable to identify any specific and new-found Se compounds in plants that could then be studied to understand their biological activity in the Se-enriched plant food products.

Generally, literature shows that organic Se species tend to have higher bioactivities, bio-accessibility and lower toxicity than inorganic Se species. Research in human immortalized keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells showed that SeMet had a lower cytotoxicity effect on HaCaT cells than sodium selenite, where the IC50 of SeMet was 55.4 μM, much higher than 2.3 μM from sodium selenite (63). The lower cytotoxicity might be related to the antioxidant activity of organic Se compounds to prevent toxicity and cellular damage by increasing selenoamino acid and selenoproteins, which could enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and thyroxine reductase (19, 64). For example, SeMet had increased GPx activity in rat skin cells at a higher dose than inorganic Se (selenite), which caused a toxic effect at 1μM (Hazane-Puch et al. (63). Moreover, SeMet increased the GPx activity and total antioxidant content while lower MDA formation in broiler chicken tissue compared to the sodium selenite-treated subjects (65).

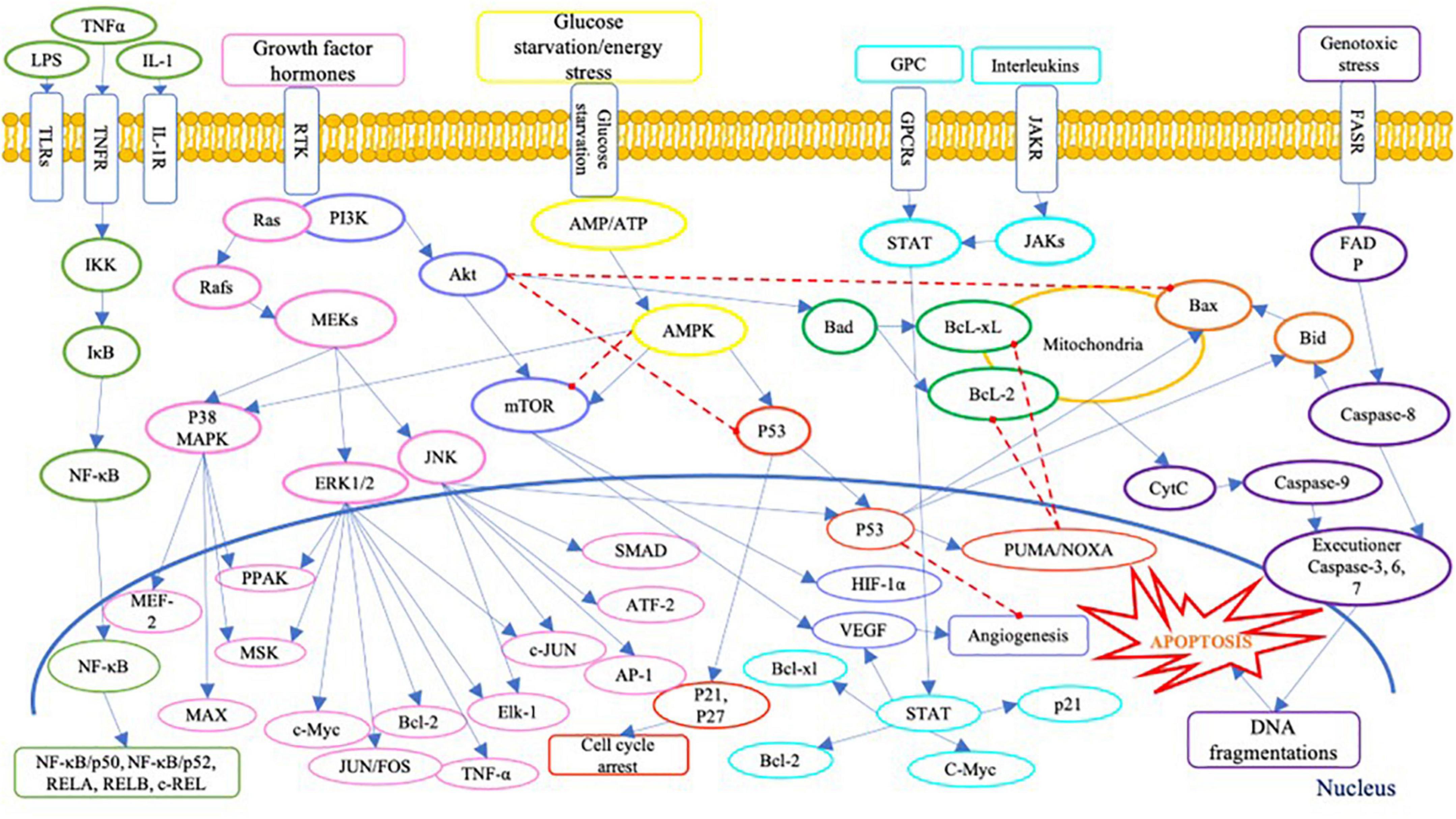

On the other hand, the presence of Se compound in high concentration could generate cytotoxicity in human cells. Literature has identified several cytotoxic pathways of Se compounds across various human cancer cell lines (Table 1). Inorganic Se species, i.e., sodium selenite, was widely studied, especially on prostate cancer cells. The cellular toxicity mechanism of sodium selenite against human prostate cancer cells has been identified as below: generation of anti-proliferation effect via the expression of mRNA of the SELV, SELW, and TGR selenoproteins (66); promotion of GLS1 protein degradation and APC/C-CDH1 apoptosis pathways (67); induction of cell apoptosis via activation of caspase-8 protein (68); and activation of p53 protein (69). Moreover, the anti-proliferation activity of inorganic Se, including sodium selenite, has been reported in human lung cancer cell lines; it has involved inhibiting the Trx1 expression (70). Several signaling pathways are involved in cell anti-proliferation and apoptosis in human cells, as shown in Figure 3. Briefly, Se could cause cell death via apoptosis pathways by activating the executioner caspase-3, 6, 7, and 9, and promoting pro-apoptosis genes Bax and Bid on mitochondria and producing cytochrome C (CytC). The toxic effect of Se compounds could also mediate DNA repair and cell angiogenesis by promoting pro-apoptosis genes, including Bax and Bid (71).

Figure 3. A schematic of apoptosis signaling pathways. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor alpha; IL-1, interleukin-1; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptors; IL-1R, interleukin-1 receptor; GPC, G protein complex; GPCRs, G protein-coupled receptor; JAKR, Janus kinase receptor; FASR, Fas receptor; IKK, IκB kinase; IκB, inhibitor of NF-κB; NF-κB, nuclear factor (NF)-κB; REL, REL protein; Ras, Ras protein; Rafs, Raf kinases; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEKs, MAPK/ERK kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; MEF-2, myocyte enhancer factor-2; PPAK, family of p21-activated protein kinases; MSK, mitogen and stress activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAX, MAX protein; c-Myc, c-Myc protein; JUNFOS, Fos and Jun families of DNA binding proteins; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; ELK-1, ETS transcription factor ELK1; AP-1, activator protein 1; ATF-2, activating transcription factor 2; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinases; Akt, serine/threonine-protein kinases; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; AMP, adenosine monophosphate activated protein; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; p53, protein p53; PUMA, p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis; NOXA, (PMAP1) – phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1; Bcl-xl, B-cell lymphoma-extra large; Bad, Bcl-2 associated death promoter; Bax, Bcl-2 associated protein x; Bid, BH3 interacting domain death agonist; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; JAKs, Janus kinases; FADP, flavin adenine dinucleotide; cytc, cytochrome complex (187–192).

A high concentration of Se compounds also performs a redox-active act as prooxidants, generating ROS in reaction (72). The redox action of Se compounds that generate ROS in the human cell could be the primary focus when using Se as an anticancer agent against human cancer cells. According to some studies (Table 1), SeMet could inhibit cell proliferation by inducing ROS generation and activating apoptosis cellular proteins, including the caspase family and p53 (73, 74). The ability to generate ROS could meditate the toxicity of Se due to the production of oxidative stress involved in cell cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction (75, 76). Moreover, MSC can induce cancer cell apoptosis via an interface of cell proliferation PI3K/Akt pathway (73), while SeCys2 downregulated Bcl-2 survival genes in lung cancer cell lines (77). A study by Hui et al. (78) also showed that selenite induced cell apoptosis by upregulate cell death protein p38 MAPK and inhibition of the PKD1/CREB/Bcl-2 survival pathway.

The current research on Se compounds focuses on both sides of the spectrum: the protective effect against cell damage or the anti-proliferation effect against cancer cell lines. Se compounds’ bioactive information could impact the functional properties of Se-enriched plant foods, not only the concentration of Se in the sample but also the chemical form of Se accumulated. Besides, the bioactive compounds such as polyphenol, polypeptides and polysaccharides in plant foods could also significantly affect the uniqueness of bioactivities and functional properties of Se enriched plants.

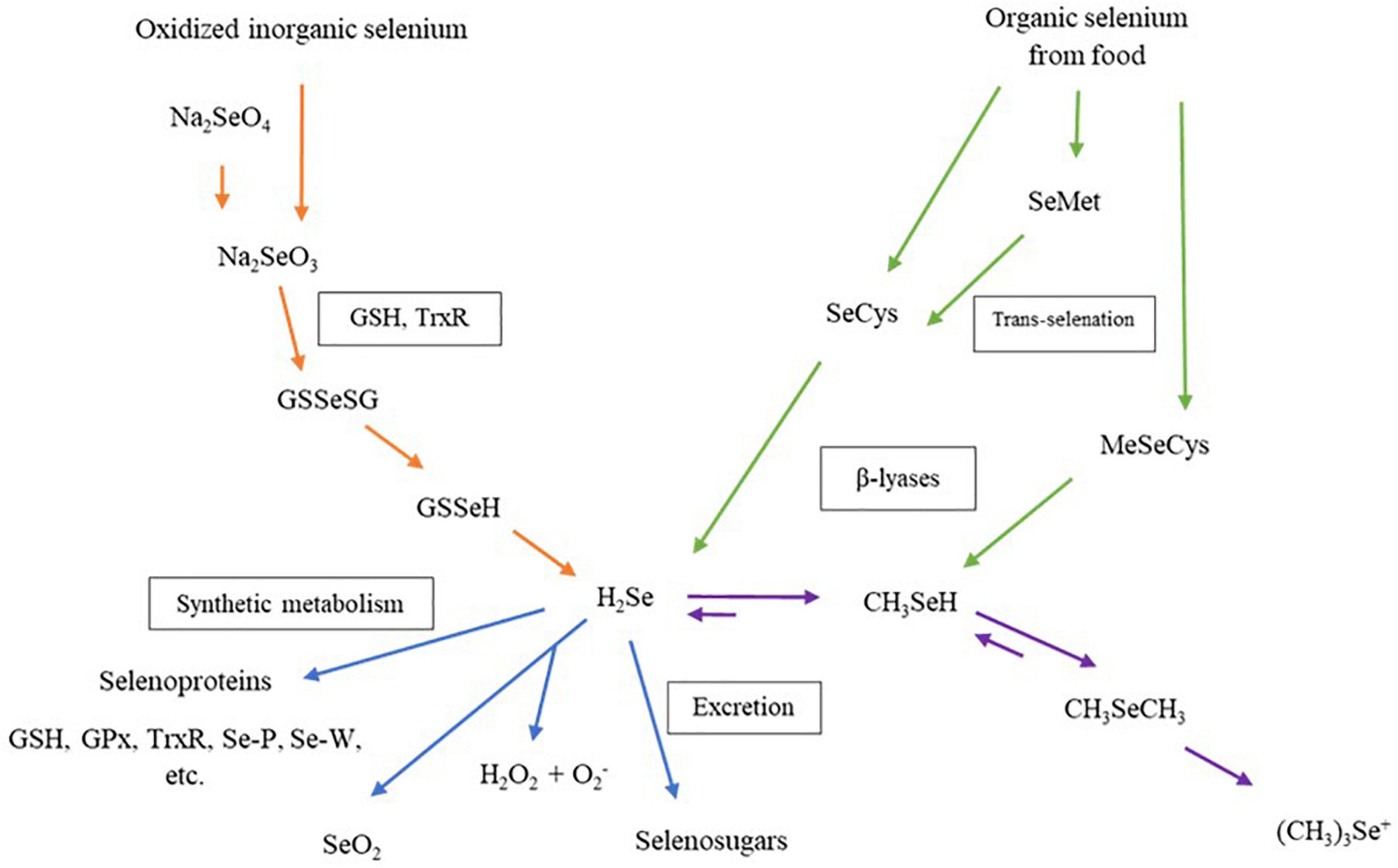

The biological properties of Se-enriched plant foods have received more interest from researchers in the past two decades. Figure 4 shows that the Se compound in Se-enriched plant foods induces biological activities through different metabolism pathways in human cells. Metabolism pathways of Se compounds begin with a reduction of inorganic or organic Se compounds from food supplements to hydrogen selenide (H2Se). This H2Se will be metabolized and synthesized into several selenoproteins, then transported and stored in human organs (79, 80). More than 25 selenoproteins have been identified in human cells, and some are considered antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase (GPxs), iodothyronine deiodinases, thioredoxin reductases (TrxR). These individual selenoproteins perform biological properties, including balancing plasma glucose levels and insulin sensitivities, anti-inflammatory and enhancing cell proliferation (4).

Figure 4. Metabolism of dietary selenium compounds in human cells. Na2SeO4, sodium selenate; Na2SeO3, sodium selenite; GSH, glutathione; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase; GSSeGS, selenodiglutathione; GSSeH, glutathioselenol; H2Se, hydrogen selenide; GPx, glutathione peroxidase family; Se-P, selenoprotein P; Se-W, selenoprotein W; SeO2, selenium dioxide; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; SeCys, selenocysteine; SeMet, selenomethionine; MeSeCys, methylselenocysteine; CH3SeH, selenol; CH3SeCH3, dimethylselenide, (CH3)3Se+, trimethylselenonium ion.

At their non-toxic concentration, Se-enriched plants could protect against cellular damage from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) stress and enhance antioxidant enzymes in normal human cells. Table 2 shows a compilation of research on the health effects of Se-enriched plants using in vitro human cells models. The antioxidant effect of Se-enriched food products has prevented oxidative stress induced by H2O2 in human cell lines. For example, Se-enriched polysaccharides extracted from Pleurotus ostreatus and Se-enriched rice grass extract showed a protective effect against cellular oxidative stress from H2O2-induction in human muscle and human kidney cells (81, 82). Moreover, Se-enriched soybean peptide increased the activities of cellular antioxidant enzymes, including GPx, SOD, and CAT, in human colon cells (83, 84).

In contrast, Se-enriched plants could generate cellular ROS and influence cell death via the apoptosis mechanism at their toxic concentrations. For example, with human cancer cell lines, Se-konjac glucomannan performed anti-proliferation properties against human lung cancer cells (A549) and human breast cancer cells (HCC1937) by activating mitochondria pro-apoptosis protein caspase-3 (85). Furthermore, Se-enriched hawthorn fruit induced cellular apoptosis on human liver cancer (HepG2) cells by upregulation of pro-apoptosis protein caspase-9, downregulation of anti-apoptosis protein Blc-2, and increasing intracellular ROS level (86). These findings indicated that Se-enriched plant foods could perform both proliferation and anti-proliferation on either cancer or non-cancer cell lines and the effects depend on Se’s dose and chemical forms in the diets.

Table 3 shows positive results on the biological properties of Se-enriched plants and some food ingredients (microalgae, probiotics bacteria and milk casein) in the in vivo animal models compared with Se-enriched yeast, an alternative source of SeMet (around 60-84%) with a lower toxic effect (87, 88). Various bioactive effects have been reported from Se-enriched plants, including increasing Se content in animal serum and tissue, enhancing antioxidant enzymes, lowering lipid oxidation in liver-stress animals, upregulation of cellular proliferation proteins, and downregulation of pro-inflammation and apoptosis cellular proteins. Some food products, for example, Se-enriched Auricularia auricular mushroom and Se-enriched radish sprouts, showed similar effects on improving antioxidant activities such as GPx and catalase, lower malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, and protecting liver damages in high-fat diet mice (89, 90). Se-polysaccharide from Astragalus also has anti-inflammatory effects on diabetic mice by lower serum inflammation-related proteins, including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) (91, 92). Moreover, Se-polysaccharide purified from Pyracantha fortuneana, and Se-enriched sweet potato inhibited tumor growth via apoptosis pathway and decreased IL-2, TNF-α, and VEGF in mice xenograft with human cancer tumor (93, 94).

In comparison, Se-enriched yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) provides antioxidant and antitumor activities in animal studies with a lower affecting dose than Se-containing plants (95, 96). Se-enriched yeast could protect from oxidative stress and increase anti-inflammation by downregulating inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-a and NF-kB in aluminum-stress mice livers (97). The bioactivity of Se-enriched yeast could be due to the presence of SeMet as the main Se compound, where its biological properties have been widely studied. Compared to Se-enriched yeast, the bioactivity of Se-enriched plants is harder to explain and conclude. Not only because of the uniqueness of Se concentration and chemical forms in different plants, but the complexity of the food matrix also plays a significant role when studying the biological properties of Se-containing plant foods (4, 98). Food matrices, including protein and carbohydrates, can incorporate with Se via biosynthesis metabolism to form complex Se structures such as selenoprotein and selenopolysaccharide. The synthesized Se molecules can play a key role in the biological activity and bioavailability of Se-enriched food in humans (99). For instance, long-chain selenopeptide synthesized in soybean showed higher resistance in gastrointestinal digestion and lower toxicity risk compared with short-chain selenopeptide (100).

Some beneficial properties of Se-enriched plant foods have been confirmed in in vitro cell models and in vivo animal studies. According to this evidence, there have been some human clinical trials performed to gain a robust understanding of the bioactivity of Se-enriched plant foods through the human metabolic system. Table 4 presents a compilation of biological properties of Se-enriched plant foods and yeast as reported in human clinical trials. Improving the activity of antioxidant enzymes in human blood systems has been discovered as the primary biological activity of Se-containing plant materials. For example, Se-containing Brazil nuts have been found to enhance GPx activities and selenoprotein P and lowering total cholesterol and LDL in older adults (101–103). Similarly, Se-enriched rice has been found to improve the total Se content and GPx activity in serum (104). Moreover, Se-enriched green onion and broccoli also showed beneficial effects in human clinical trials (105, 106). On the other hand, Se-enriched yeast has been applied as an effective and less toxic Se supplement to provide significant health properties. Se-enriched yeast could lower blood glucose, enhance insulin sensitivity, and lower the total cholesterol and LDL (107–109).

From these findings, Se-enriched plant foods at their non-toxic concentration can deliver health benefits by increasing antioxidant activity in human serum. Daily intake of Se for humans is about 55-70 μg Se per day, with the toxic level at 400 μg Se per day. From the data in Table 4, the dose of Se-enriched plant food and Se-enriched yeast in the range of 200-300 μg Se per day could provide health benefits without showing toxic side effects (110). The information from this review suggested that Se-enriched plant foods should be a safer choice for increasing dietary Se consumption due to a moderate concentration of Se in the plant investigated, and the organic Se compounds are significantly identified in plant food materials.

Overall, not many Se-enriched plants have successfully demonstrated a significant beneficial effect in human clinical trials (111–113) compared to the amount of investigations conducted in cell-based and animal models. Many factors can affect the results of clinical trials, including genetics, age, gender, ethnicity, personal behaviors, medical conditions, etc. (114, 115), and they need to be taken into account when designing a trial. It is essential to identify the bioactive compounds present in the plant materials, study how they can influence the bioactivity of the Se-enriched plant foods and verify the bioactivity and toxicity effects of the Se-enriched plant foods from the in vitro human cell lines and in vivo animal testing. All of these will provide information on the samples’ biological properties, the corrective consumption level, and the toxicity dose of each Se-enriched plant food for human clinical trials.

The biological properties of Se-containing plant foods are closely associated with the chemical forms and concentrations of Se content in the products. The studies on Se accumulation and speciation of Se compounds could provide helpful insight into the mechanism of Se-enriched plant foods’ bioactivities. These beneficial bioactivities, including antioxidant, and anticancer properties of Se-enriched plant foods, have been positively demonstrated via in vitro human cell lines and in vivo animal studies. There is still a need for more human trials to relate the effect of Se-enriched foods and their health effects. Human clinical trials are critical to obtaining information regarding the consumption of Se-enriched food plants, considering different factors, including human genetic and age groups, and the effect of the food matrix.

Humans in different age groups (e.g., children, adults, elderly), gender, and health and physiological status (e.g., pregnancy and lactation) have different dietary requirements. Therefore, supplementing dietary Se to different groups of the population can be challenging as many factors need to be considered to ensure the supplementation deliver its intended health benefits. Due to the narrow gap between benefits and toxicity, precautions must be taken when considering Se enrichment in foods. The first thing to consider is the Se species present in the plant used for producing Se-enrichment foods. Since organic Se has far less toxicity, it is more suitable to be incorporated into food products. For safety reasons, it is essential to use Se-enriched plants that accumulate organic Se than those that accumulate a high inorganic Se content. Se-enriched plant foods with a moderate level of organic Se can be a more decent choice as a Se-supplement for all groups of people. Secondly, contamination from other metals, such as Cd and As, during Se accumulation can cause toxic stress in the plant and human health. Metal contamination in plants is mainly associated with the quality of soil and fertilizer applied during the enrichment stage. Soil quality and composition of Se fertilizer should be carefully monitored to avoid metal contamination of Se-enriched plants (116). Thirdly, limiting the consumption dose of Se-enriched food to a non-toxic level could prevent the harmful effect of Se toxicity. Regulations can be set and enforced to limit the level or serving size of Se-enriched foods to suit different groups of people. Furthermore, there is a need to establish suitable analytical methods to study Se speciation of various Se-enriched plant foods and perform more research to gather clinical information on bioactivity and toxicity when supplying Se-enriched plant food to different groups of the population. All these efforts are essential to protect from the negative effect of Se overdose, ensure safety and deliver the optimum benefit of Se-enriched foods to humans.

Future studies should cover the full spectrum of the research area, including identifying Se content and their chemical forms, in particular putting more effort on Se speciation of Se-enriched plant materials; screening their biological effects via in vitro assays or in vivo animal studies; and validating the findings in the human clinical trials. The evidence and knowledge from the above research could serve as a powerful motivation for the food industry to produce Se-enriched plant foods to combat Se deficiency and enhance life quality for the world population.

PT, JX, and SQ generated the presented idea in this manuscript. PT and SQ developed the theory, scope and performed the computation of the data. PT, PS, and SQ versified, analyzed, and discussed the collected data. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.962312/full#supplementary-material

2. Zhou X, Li Y, Lai F. Effects of different water management on absorption and accumulation of selenium in rice. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2018) 25:1178–82. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.10.017

3. Zhang X, He H, Xiang J, Yin H, Hou T. Selenium-containing proteins/peptides from plants: a review on the structures and function. J Agric Food Chem. (2020) 68:15061–73. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05594

5. Deng H, Liu H, Yang Z, Bao M, Lin X, Han J, et al. Progress of selenium deficiency in the pathogenesis of arthropathies and selenium supplement for their treatment. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2021) 200:4238–49.

6. Fordyce FM. Selenium deficiency and toxicity in the environment. In: O Selinus editor. Essentials of Medical Geology. Dordrecht: Springer (2013). p. 375–416.

7. Zhang S, Li B, Luo K. Differences of selenium and other trace elements abundances between the Kaschin-Beck disease area and nearby non-Kaschin-Beck disease area, Shaanxi Province, China. Food Chem. (2022) 373:131481. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131481

8. Loscalzo J. Keshan disease, selenium deficiency, and the selenoproteome. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370:1756–60.

9. Jia Y, Wang R, Su S, Qi L, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. A county-level spatial study of serum selenoprotein P and keshan disease. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:827093. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.827093

10. Cao J, Li S, Shi Z, Yue Y, Sun J, Chen J, et al. Articular cartilage metabolism in patients with Kashin–beck disease: an endemic osteoarthropathy in China. Osteoarthr Cartil. (2008) 16:680–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.09.002

11. Zhang X, He H, Xiang J, Hou T. Screening and bioavailability evaluation of anti-oxidative selenium-containing peptides from soybeans based on specific structures. Food Funct. (2022) 13:5252–61. doi: 10.1039/d2fo00113f

12. Bellinger FP, Raman AV, Reeves MA, Berry MJ. Regulation and function of selenoproteins in human disease. Biochem J. (2009) 422:11–22. doi: 10.1042/bj20090219

13. Hoffmann PR. Mechanisms by which selenium influences immune responses. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. (2007) 55:289.

14. Chang C, Yin R, Wang X, Shao S, Chen C, Zhang H. Selenium translocation in the soil-rice system in the Enshi seleniferous area, Central China. Sci Total Environ. (2019) 669:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.451

15. Huang Y, Wang Q, Gao J, Lin Z, Bañuelos GS, Yuan L, et al. Daily dietary selenium intake in a high selenium area of Enshi, China. Nutrients. (2013) 5:700–10. doi: 10.3390/nu5030700

16. Qin H-B, Zhu J-M, Liang L, Wang M-S, Su H. The bioavailability of selenium and risk assessment for human selenium poisoning in high-Se areas, China. Environ Int. (2013) 52:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.12.003

17. Fairweather-Tait SJ, Bao Y, Broadley MR, Collings R, Ford D, Hesketh JE, et al. Selenium in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2011) 14:1337–83.

18. Navarro-Alarcon M, Cabrera-Vique C. Selenium in food and the human body: a review. Sci Total Environ. (2008) 400:115–41. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.024

19. Gandin V, Khalkar P, Braude J, Fernandes AP. Organic selenium compounds as potential chemotherapeutic agents for improved cancer treatment. Free Radic Biol Med. (2018) 127:80–97.

20. Gupta M, Gupta S. An overview of selenium uptake, metabolism, and toxicity in plants. Front Plant Sci. (2017) 7:2074. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.02074

22. Terry N, Zayed A, De Souza M, Tarun A. Selenium in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. (2000) 51:401–32.

23. Bañuelos GS, Arroyo IS, Dangi SR, Zambrano MC. Continued selenium biofortification of carrots and broccoli grown in soils once amended with Se-enriched S. pinnata. Front Plant Sci. (2016) 7:1251. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01251

24. Hu Z, Cheng Y, Suzuki N, Guo X, Xiong H, Ogra Y. Speciation of selenium in brown rice fertilized with selenite and effects of selenium fertilization on rice proteins. Int J Mol Sci. (2018) 19:3494. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113494

25. Jiang Y, El Mehdawi AF, Lima LW, Stonehouse G, Fakra SC, Hu Y, et al. Characterization of selenium accumulation, localization and speciation in buckwheat–implications for biofortification. Front Plant Sci. (2018) 9:1583. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01583

26. Both EB, Shao S, Xiang J, Jókai Z, Yin H, Liu Y, et al. Selenolanthionine is the major water-soluble selenium compound in the selenium tolerant plant Cardamine violifolia. Biophys Acta Gen Subj. (2018) 1862:2354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.460919

27. Kolbert Z, Molnár Á, Feigl G, Van Hoewyk D. Plant selenium toxicity: proteome in the crosshairs. J Plant Physiol. (2019) 232:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.11.003

28. White PJ. Selenium metabolism in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. (2018) 1862:2333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.05.006

29. Winkel LH, Vriens B, Jones GD, Schneider LS, Pilon-Smits E, Bañuelos GS. Selenium cycling across soil-plant-atmosphere interfaces: a critical review. Nutrients. (2015) 7:4199–239. doi: 10.3390/nu7064199

30. Lidon FC, Oliveira K, Galhano C, Guerra M, Ribeiro MM, Pelica J, et al. Selenium biofortification of rice through foliar application with selenite and selenate Exp Agric. (2019) 55:528–42. doi: 10.1017/S0014479718000157

31. Zhang H, Zhao Z, Zhang X, Zhang W, Huang L, Zhang Z, et al. Effects of foliar application of selenate and selenite at different growth stages on Selenium accumulation and speciation in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Food Chem. (2019) 286:550–6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.185

32. Wang M, Peng Q, Zhou F, Yang W, Dinh QT, Liang D. Uptake kinetics and interaction of selenium species in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seedlings. Environ Sci Pollut Res. (2019) 26:9730–8. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04182-6

33. Chen JJ, Boylan LM, Wu CK, Spallholz JE. Oxidation of glutathione and superoxide generation by inorganic and organic selenium compounds. BioFactors. (2007) 31:55–66.

34. Ramkissoon C, Degryse F, da Silva RC, Baird R, Young SD, Bailey EH, et al. Improving the efficacy of selenium fertilizers for wheat biofortification. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:19520.

35. da Cruz Ferreira RL, de Mello Prado R, de Souza Junior JP, Gratão PL, Tezotto T, Cruz FJR. Oxidative stress, nutritional disorders, and gas exchange in lettuce plants subjected to two selenium sources. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. (2020) 20:1215–28. doi: 10.1007/s42729-020-00206-0

36. Lanza MGDB, Reis ARD. Roles of selenium in mineral plant nutrition: ROS scavenging responses against abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol Biochem. (2021) 164:27–43. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.04.0261

37. Xu C, Qiao L, Guo Y, Ma L, Cheng Y. Preparation, characteristics and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides and proteins-capped selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. Carbohydr Polym. (2018) 195:576–85. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.110

38. Rohn I, Marschall TA, Kroepfl N, Jensen KB, Aschner M, Tuck S, et al. Selenium species-dependent toxicity, bioavailability and metabolic transformations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Metallomics. (2018) 10:818–27. doi: 10.1039/c8mt00066b

39. Hasanuzzaman M, Bhuyan MB, Raza A, Hawrylak-Nowak B, Matraszek-Gawron R, Nahar K, et al. Selenium toxicity in plants and environment: biogeochemistry and remediation possibilities. Plants. (2020) 9:1711. doi: 10.3390/plants9121711

40. Huerta VD, Sánchez MLF, Sanz-Medel A. Qualitative and quantitative speciation analysis of water soluble selenium in three edible wild mushrooms species by liquid chromatography using post-column isotope dilution ICP–MS. Anal Chim Acta. (2005) 538:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.02.033

41. Turło J, Gutkowska B, Herold F. Effect of selenium enrichment on antioxidant activities and chemical composition of Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegl. mycelial extracts. Food Chem Toxicol. (2010) 48:1085–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.01.030

43. Dernovics M, Stefánka Z, Fodor P. Improving selenium extraction by sequential enzymatic processes for Se-speciation of selenium-enriched Agaricus bisporus. Anal Bioanal Chem. (2002) 372:473–80. doi: 10.1007/s00216-001-1215-5

44. Pauly M, Keegstra K. Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource for biofuels. Plant J. (2008) 54:559–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03463.x

45. Xu T. Ion exchange membranes: state of their development and perspective. J Memb Sci. (2005) 263:1–29. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2005.05.002

46. Barbaro P, Liguori F. Ion exchange resins: catalyst recovery and recycle. Chem Rev. (2009) 109:515–29. doi: 10.1021/cr800404j

47. Acikara ÖB. Ion exchange chromatography and its applications. Column Chromatogr. (2013) 10:55744.

48. Zbacnik TJ, Holcomb RE, Katayama DS, Murphy BM, Payne RW, Coccaro RC, et al. Role of buffers in protein formulations. J Pharm Sci. (2017) 106:713–33. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.11.014

49. Larsen EH, Hansen M, Fan T, Vahl M. Speciation of selenoamino acids, selenonium ions and inorganic selenium by ion exchange HPLC with mass spectrometric detection and its application to yeast and algae. J Anal Spectrom. (2001) 16:1403–8.

50. Goessler W, Kuehnelt D, Schlagenhaufen C, Kalcher K, Abegaz M, Irgolic KJ. Retention behavior of inorganic and organic selenium compounds on a silica-based strong-cation-exchange column with an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer as selenium-specific detector. J Chromatogr A. (1997) 789:233–45.

51. Reid MS, Hoy KS, Schofield JR, Uppal JS, Lin Y, Lu X, et al. Arsenic speciation analysis: a review with an emphasis on chromatographic separations. Trends Anal Chem. (2020) 123:115770.

52. Zhu D, Zheng W, Chang H, Xie H. A theoretical study on the pKa values of selenium compounds in aqueous solution. N J. Chem. (2020) 44:8325–36.

53. Vale G, Rodrigues A, Rocha A, Rial R, Mota AM, Gonçalves ML, et al. Ultrasonic assisted enzymatic digestion (USAED) coupled with high performance liquid chromatography and electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry as a powerful tool for total selenium and selenium species control in Se-enriched food supplements. Food Chem. (2010) 121:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.084

54. Gajdosechova Z, Mester Z, Feldmann J, Krupp EM. The role of selenium in mercury toxicity – Current analytical techniques and future trends in analysis of selenium and mercury interactions in biological matrices. Trends Anal Chem. (2018) 104:95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2017.12.005

55. Ogra Y, Ogihara Y, Anan Y. Comparison of the metabolism of inorganic and organic selenium species between two selenium accumulator plants, garlic and Indian mustard. Metallomics. (2017) 9:61–8. doi: 10.1039/c6mt00128a

56. Dernovics M, Lobinski R. Speciation analysis of selenium metabolites in yeast-based food supplements by ICPMS- assisted hydrophilic interaction HPLC- hybrid linear ion trap/orbitrap MS n. Anal Chem. (2008) 80:3975–84. doi: 10.1021/ac8002038

57. Shao S, Mi X, Ouerdane L, Lobinski R, García-Reyes JF, Molina-Díaz A, et al. Quantification of Se-methylselenocysteine and its γ-Glutamyl derivative from naturally Se-enriched green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris vulgaris) after HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS and orbitrap MSn-based identification. Food Anal Methods. (2014) 7:1147–57. doi: 10.1007/s12161-013-9728-z

58. Ho CS, Lam CWK, Chan MHM, Cheung RCK, Law LK, Lit LCW, et al. Electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry: principles and clinical applications. Clin Biochem Rev. (2003) 24:3–12.

59. Arias-Borrego A, Callejón-Leblic B, Rodríguez-Moro G, Velasco I, Gómez-Ariza J, García-Barrera T. A novel HPLC column switching method coupled to ICP-MS/QTOF for the first determination of selenoprotein P (SELENOP) in human breast milk. Food Chem. (2020) 321:126692. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126692

60. Lu Y, Rumpler A, Francesconi KA, Pergantis SA. Quantitative selenium speciation in human urine by using liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. (2012) 731:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.04.016

61. Papaslioti EM, Parviainen A, Román Alpiste MJ, Marchesi C, Garrido CJ. Quantification of potentially toxic elements in food material by laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) via pressed pellets. Food Chem. (2019) 274:726–32. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.118

62. Bissardon C, Isaure MP, Lesuisse E, Rovezzi M, Lahera E, Proux O, et al. Biological Samples preparation for speciation at cryogenic temperature using high-resolution x-ray absorption spectroscopy. J Vis Exp. (2022) 183:e60849. doi: 10.3791/60849

63. Hazane-Puch F, Champelovier P, Arnaud J, Garrel C, Ballester B, Faure P, et al. Long-term selenium supplementation in HaCaT cells: importance of chemical form for antagonist (Protective Versus Toxic) activities. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2013) 154:288–98. doi: 10.1007/s12011-013-9709-5

64. Jonklaas J, Danielsen M, Wang H. A pilot study of serum selenium, vitamin D, and thyrotropin concentrations in patients with thyroid cancer. Thyroid. (2013) 23:1079–86. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0548

65. Bakhshalinejad R, Akbari Moghaddam Kakhki R, Zoidis E. Effects of different dietary sources and levels of selenium supplements on growth performance, antioxidant status and immune parameters in Ross 308 broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci. (2018) 59:81–91.

66. Varlamova E, Goltyaev M, Kuznetsova J. Effect of sodium selenite on gene expression of SELF, SELW, and TGR selenoproteins in adenocarcinoma cells of the human prostate. Mol Biol Rep. (2018) 52:446–52. doi: 10.7868/S0026898418030151

67. Zhao J, Zhou R, Hui K, Yang Y, Zhang Q, Ci Y, et al. Selenite inhibits glutamine metabolism and induces apoptosis by regulating GLS1 protein degradation via APC/C-CDH1 pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:18832. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13600

68. Chen P, Wang L, Li N, Liu Q, Ni J. Comparative proteomics analysis of sodium selenite-induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Metallomics. (2013) 5:541–50. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00002h

69. Sarveswaran S, Liroff J, Zhou Z, Nikitin AY, Ghosh J. Selenite triggers rapid transcriptional activation of p53, and p53-mediated apoptosis in prostate cancer cells: implication for the treatment of early-stage prostate cancer. Int J Oncol. (2010) 36:1419–28. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000627

70. Zheng X, Xu W, Sun R, Yin H, Dong C, Zeng H. Synergism between thioredoxin reductase inhibitor ethaselen and sodium selenite in inhibiting proliferation and inducing death of human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact. (2017) 275:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.07.020

71. He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. (2007) 447:1130–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05939

72. Kuršvietienė L, Mongirdienė A, Bernatonienė J, Šulinskienė J, Stanevičienė I. Selenium anticancer properties and impact on cellular redox status. Antioxidants. (2020) 9:80. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010080

73. Suzuki M, Endo M, Shinohara F, Echigo S, Rikiishi H. Differential apoptotic response of human cancer cells to organoselenium compounds. Chemother Pharmacol. (2010) 66:475–84. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1183-6

74. Weekley CM, Aitken JB, Vogt S, Finney LA, Paterson DJ, de Jonge MD, et al. Uptake, distribution, and speciation of selenoamino acids by human cancer cells: X-ray absorption and fluorescence methods. Biochemistry. (2011) 50:1641–50. doi: 10.1021/bi101678a

75. Weekley CM, Jeong G, Tierney ME, Hossain F, Maw AM, Shanu A, et al. Selenite-mediated production of superoxide radical anions in A549 cancer cells is accompanied by a selective increase in SOD1 concentration, enhanced apoptosis and Se–Cu bonding. J Biol Inorg Chem. (2014) 19:813–28.

76. Xiang N, Zhao R, Zhong WX. Sodium selenite induces apoptosis by generation of superoxide via the mitochondrial-dependent pathway in human prostate cancer cells. Chemother Pharmacol. (2009) 63:351–62. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0745-3

77. Fan C, Zheng W, Fu X, Li X, Wong YS, Chen T. Enhancement of auranofin-induced lung cancer cell apoptosis by selenocystine, a natural inhibitor of TrxR1 in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. (2014) 5:132. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.132

78. Hui K, Yang Y, Shi K, Luo H, Duan J, An J, et al. The p38 MAPK-regulated PKD1/CREB/Bcl-2 pathway contributes to selenite-induced colorectal cancer cell apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. (2014) 354:189–99. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.009

80. Weekley C, Aitken J, Finney L, Vogt S, Witting P, Harris H. Selenium metabolism in cancer cells: the combined application of XAS and XFM techniques to the problem of selenium speciation in biological systems. Nutrients. (2013) 5:1734. doi: 10.3390/nu5051734

81. Chomchan R, Puttarak P, Brantner A, Siripongvutikorn S. Selenium-rich ricegrass juice improves antioxidant properties and nitric oxide inhibition in macrophage cells. Antioxidants. (2018) 7:57. doi: 10.3390/antiox7040057

82. Ma L, Zhao Y, Yu J, Ji H, Liu A. Characterization of Se-enriched Pleurotus ostreatus polysaccharides and their antioxidant effects in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. (2018) 111:421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.152

83. Chen J, Feng T, Wang B, He R, Xu Y, Gao P, et al. Enhancing organic selenium content and antioxidant activities of soy sauce using nano-selenium during soybean soaking. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:970206. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.970206

84. Ye Q, Wu X, Zhang X, Wang S. Organic selenium derived from chelation of soybean peptide-selenium and its functional properties in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. (2019) 10:4761–70. doi: 10.1039/c9fo00729f

85. Li Q, Liu M, Hou J, Jiang C, Li S, Wang T. The prevalence of Keshan disease in China. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168:1121–6.

86. Cui D, Liang T, Sun L, Meng L, Yang C, Wang L, et al. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles with extract of hawthorn fruit induced HepG2 cells apoptosis. Pharm Biol. (2018) 56:528–34. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2018.1510974

87. Rayman MP. Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and mechanism of action. Proc Nutr Soc. (2005) 64:527–42.

88. Fairweather-Tait SJ, Collings R, Hurst R. Selenium bioavailability: current knowledge and future research requirements. Am J Clin Nutr. (2010) 91:1484–91S.

89. Wei C, Wang J, Duan C, Fan H, Liu X. Aqueous extracts of Se-enriched Auricularia auricular exhibits antioxidant capacity and attenuate liver damage in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. J Med Food. (2020) 23:153–60. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2019.4416

90. Jia L, Wang T, Sun Y, Zhang M, Tian J, Chen H, et al. Protective effect of selenium-enriched red radish sprouts on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury in mice. J Food Sci. (2019) 84:3027–36. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14727

91. Yuan H, Wang W, Chen D, Zhu X, Meng L. Effects of a treatment with Se-rich rice flour high in resistant starch on enteric dysbiosis and chronic inflammation in diabetic ICR mice. J Sci Food Agric. (2017) 97:2068–74. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8011

92. Hamid M, Liu D, Abdulrahim Y, Liu Y, Qian G, Khan A, et al. Amelioration of CCl4-induced liver injury in rats by selenizing Astragalus polysaccharides: role of proinflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress and hepatic stellate cells. Res Vet Sci. (2017) 114:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.05.002

93. Yuan B, Yang X-Q, Kou M, Lu C-Y, Wang Y-Y, Peng J, et al. Selenylation of polysaccharide from the sweet potato and evaluation of antioxidant, antitumor, and antidiabetic activities. J Agric Food Chem. (2017) 65:605–17. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04788

94. Sun Q, Dong M, Wang Z, Wang C, Sheng D, Li Z, et al. Selenium-enriched polysaccharides from Pyracantha fortuneana (Se-PFPs) inhibit the growth and invasive potential of ovarian cancer cells through inhibiting β -catenin signaling. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:28369–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8619

95. Guo C-H, Hsia S, Hsiung D-Y, Chen P-C. Supplementation with Selenium yeast on the prooxidant–antioxidant activities and anti-tumor effects in breast tumor xenograft-bearing mice. J Nutr Biochem. (2015) 26:1568–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.07.028

96. Yuan D, Zhan XA, Wang YX. Effect of selenium sources on the expression of cellular glutathione peroxidase and cytoplasmic thioredoxin reductase in the liver and kidney of broiler breeders and their offspring. Poult Sci. (2012) 91:936–42. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01921

97. Luo J, Li X, Li X, He Y, Zhang M, Cao C, et al. Selenium-Rich Yeast protects against aluminum-induced peroxidation of lipide and inflammation in mice liver. BioMetals. (2018) 31:1051–9. doi: 10.1007/s10534-018-0150-2

98. Rayman MP. Food-chain selenium and human health: emphasis on intake. Br J Nutr. (2008) 100:254–68.

99. Xu M, Zhu S, Li Y, Xu S, Shi G, Ding Z. Effect of selenium on mushroom growth and metabolism: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. (2021) 118:328–40.

100. Zhang Y, Liu Y, Gong Y, Huang L, Liu H, Hu M, et al. The status of selenium and zinc in the urine of children from endemic areas of Kashin-beck disease over three consecutive years. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:862639. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.862639

101. Hu Y, McIntosh GH, Le Leu RK, Somashekar R, Meng XQ, Gopalsamy G, et al. Supplementation with Brazil nuts and green tea extract regulates targeted biomarkers related to colorectal cancer risk in humans. Br J Nutr. (2016) 116:1901–11. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516003937

102. Huguenin GV, Oliveira GM, Moreira AS, Saint’Pierre TD, Gonçalves RA, Pinheiro-Mulder AR, et al. Improvement of antioxidant status after Brazil nut intake in hypertensive and dyslipidemic subjects. Nutr J. (2015) 14:54. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0043-y

103. Stockler-Pinto M, Mafra D, Farage N, Boaventura G, Cozzolino S. Effect of Brazil nut supplementation on the blood levels of selenium and glutathione peroxidase in hemodialysis patients. Nutrition. (2010) 26:1065–9.

104. Giacosa A, Faliva MA, Perna S, Minoia C, Ronchi A, Rondanelli M. Selenium fortification of an Italian rice cultivar via foliar fertilization with sodium selenate and its effects on human serum selenium levels and on erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase activity. Nutrients. (2014) 6:1251–61. doi: 10.3390/nu6031251

105. Ivory K, Prieto E, Spinks C, Armah CN, Goldson AJ, Dainty JR, et al. Selenium supplementation has beneficial and detrimental effects on immunity to influenza vaccine in older adults. Clin Nutr. (2017) 36:407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.12.003

106. Bentley-Hewitt KL, Chen RKY, Lill RE, Hedderley D I, Herath TD, Matich AJ, et al. Consumption of selenium-enriched broccoli increases cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated ex vivo, a preliminary human intervention study. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2014) 58:2350–7. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400438

107. Stranges S, Rayman MP, Winther KH, Guallar E, Cold S, Pastor-Barriuso R. Effect of selenium supplementation on changes in HbA1c: results from a multiple-dose, randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2019) 21:541–9. doi: 10.1111/dom.13549

108. Raygan F, Behnejad M, Ostadmohammadi V, Bahmani F, Mansournia MA, Karamali F, et al. Selenium supplementation lowers insulin resistance and markers of cardio-metabolic risk in patients with congestive heart failure: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Nutr. (2018) 120:33–40. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001253

109. Karamali M, Nourgostar S, Zamani A, Vahedpoor Z, Asemi Z. The favourable effects of long-term selenium supplementation on regression of cervical tissues and metabolic profiles of patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Nutr. (2015) 114:2039–45. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515003852

110. Baj J, Flieger W, Teresiński G, Buszewicz G, Sitarz R, Forma A, et al. Magnesium, calcium, potassium, sodium, phosphorus, selenium, zinc, and chromium levels in alcohol use disorder: a review. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1901. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061901

111. Jacobs ET, Lance P, Mandarino LJ, Ellis NA, Chow HHS, Foote J, et al. Selenium supplementation and insulin resistance in a randomized, clinical trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. (2019) 7:e000613. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000613

112. Cold F, Winther KH, Pastor-Barriuso R, Rayman MP, Guallar E, Nybo M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of the effect of long-term selenium supplementation on plasma cholesterol in an elderly Danish population. Br J Nutr. (2015) 114:1807–18. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515003499

113. Ravn-Haren G, Bügel S, Krath BN, Hoac T, Stagsted J, Jørgensen K, et al. A short-term intervention trial with selenate, selenium-enriched yeast and selenium-enriched milk: effects on oxidative defence regulation. Br J Nutr. (2008) 99:883–92. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507825153

114. Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. (1997) 278:1349–56.

115. Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley III JL. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. (2009) 10:447–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001

116. Riaz M, Kamran M, Rizwan M, Ali S, Parveen A, Malik Z, et al. Cadmium uptake and translocation: selenium and silicon roles in Cd detoxification for the production of low Cd crops: a critical review. Chemosphere. (2021) 273:129690. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129690

117. Suzuki M, Endo M, Shinohara F, Echigo S, Rikiishi H. Rapamycin suppresses ROS-dependent apoptosis caused by selenomethionine in A549 lung carcinoma cells. Chemother Pharmacol. (2011) 67:1129–36. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1417-7

118. Li T, Xiang W, Li F, Xu H. Self-assembly regulated anticancer activity of platinum coordinated selenomethionine. Biomaterials. (2018) 157:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.12.001

119. Poerschke RL, Moos PJ. Thioredoxin reductase 1 knockdown enhances selenazolidine cytotoxicity in human lung cancer cells via mitochondrial dysfunction. Biochem Pharmacol. (2011) 81:211–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.09.024

120. Tarrado-Castellarnau M, Cortés R, Zanuy M, Tarragó-Celada J, Polat IH, Hill R, et al. Methylseleninic acid promotes antitumour effects via nuclear FOXO3a translocation through Akt inhibition. Pharmacol Res. (2015) 102:218–34. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.09.009

121. Wu H, Zhu H, Li X, Liu Z, Zheng W, Chen T, et al. Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells by surface-capping selenium nanoparticles: an effect enhanced by polysaccharide–protein complexes from Polyporus rhinocerus. J Agric Food Chem. (2013) 61:9859–66. doi: 10.1021/jf403564s

122. Liu C, Liu H, Li Y, Wu Z, Zhu Y, Wang T, et al. Intracellular glutathione content influences the sensitivity of lung cancer cell lines to methylseleninic acid. Mol Carcinog. (2012) 51:303–14. doi: 10.1002/mc.20781

123. Pons DG, Moran C, Alorda-Clara M, Oliver J, Roca P, Sastre-Serra J. Micronutrients selenomethionine and selenocysteine modulate the redox status of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Nutrients. (2020) 12:865. doi: 10.3390/nu12030865

124. Chen TF, Wong YS. Selenocystine induces reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in human cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. (2009) 63:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.03.009

125. de Miranda JX, Andrade FDO, Conti AD, Dagli MLZ, Moreno FS, Ong TP. Effects of selenium compounds on proliferation and epigenetic marks of breast cancer cells. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2014) 28:486–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.06.017

126. Redman C, Scott JA, Baines AT, Basye JL, Clark LC, Calley C, et al. Inhibitory effect of selenomethionine on the growth of three selected human tumor cell lines. Cancer Lett. (1998) 125:103–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00497-7

127. Long MJ, Wu JK, Hao JW, Liu W, Tang Y, Li X, et al. Selenocystine-induced cell apoptosis and S-phase arrest inhibit human triple-negative breast cancer cell proliferation in vitro cell. Dev Biol A. (2015) 51:1077–84. doi: 10.1007/s11626-015-9937-4

128. Baines A, Taylor-Parker M, Goulet AC, Renaud C, Gerner EW, Nelson MA. Selenomethionine inhibits growth and suppresses cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) protein expression in human colon cancer cell lines. Cancer Biol Ther. (2002) 1:370–4.

129. Chigbrow M, Nelson M. Inhibition of mitotic cyclin B and cdc2 kinase activity by selenomethionine in synchronized colon cancer cells. Anti Cancer Drugs. (2001) 12:43–50. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200101000-00006

130. Pinto JT, Sinha R, Papp K, Facompre ND, Desai D, El-Bayoumy K. Differential effects of naturally occurring and synthetic organoselenium compounds on biomarkers in androgen responsive and androgen independent human prostate carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. (2007) 120:1410–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22500

131. Menter DG, Sabichi AL, Lippman SM. Selenium effects on prostate cell growth. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. (2000) 9:1171–82.

132. Gundimeda U, Schiffman JE, Chhabra D, Wong J, Wu A, Gopalakrishna R. Locally generated methylseleninic acid induces specific inactivation of protein kinase C isoenzymes: relevance to selenium-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. (2008) 283:34519–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807007200

133. Hinrichsen S, Planer-Friedrich B. Cytotoxic activity of selenosulfate versus selenite in tumor cells depends on cell line and presence of amino acids. Environ Sci Pollut Res. (2016) 23:8349–57. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5960-y

134. Wang W, Meng FB, Wang ZX, Li X, Zhou DS. Selenocysteine inhibits human osteosarcoma cells growth through triggering mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS-mediated p53 phosphorylation. Cell Biol Int. (2018) 42:580–8. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10934

135. Rooprai HK, Kyriazis I, Nuttall RK, Edwards DR, Zicha D, Aubyn D, et al. Inhibition of invasion and induction of apoptosis by selenium in human malignant brain tumour cells in vitro. Int J Oncol. (2007) 30:1263–71.

136. Chen T, Wong YS. Selenocystine induces apoptosis of A375 human melanoma cells by activating ROS-mediated mitochondrial pathway and p53 phosphorylation. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2008) 65:2763–75. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8329-2

137. De Felice B, Garbi C, Wilson RR, Santoriello M, Nacca M. Effect of selenocystine on gene expression profiles in human keloid fibroblasts. Genomics. (2011) 97:265–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.02.009

138. Wallenberg M, Misra S, Wasik AM, Marzano C, Björnstedt M, Gandin V, et al. Selenium induces a multi-targeted cell death process in addition to ROS formation. J Cell Mol Med. (2014) 18:671–84. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12214

139. Zagrodzki P, Paśko P, Galanty A, Tyszka-Czochara M, Wietecha-Posłuszny R, Rubió PS, et al. Does selenium fortification of kale and kohlrabi sprouts change significantly their biochemical and cytotoxic properties? J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2020) 59:126466. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126466

140. Li K, Qi H, Liu Q, Li T, Chen W, Li S, et al. Preparation and antitumor activity of selenium-modified glucomannan oligosaccharides. J Funct Foods. (2020) 65:103731. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103731

141. Fan Z, Wang Y, Yang M, Cao J, Khan A, Cheng G. UHPLC-ESI-HRMS/MS analysis on phenolic compositions of different E Se tea extracts and their antioxidant and cytoprotective activities. Food Chem. (2020) 318:126512. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126512

142. Gao P, Bian J, Xu S, Liu C, Sun Y, Zhang G, et al. Structural features, selenization modification, antioxidant and anti-tumor effects of polysaccharides from alfalfa roots. Int J Biol Macromol. (2020) 149:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.239

143. Tran TTT, Tran VH, Bui VTU, Giang KL. Selenyl derivatives of polysaccharide from Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsley) A gray and their cytotoxicity. J Biol Act Prod Nat. (2019) 9:97–107. doi: 10.1080/22311866.2019.1607555

144. Abdulah R, Faried A, Kobayashi K, Yamazaki C, Suradji EW, Ito K, et al. Selenium enrichment of broccoli sprout extract increases chemosensitivity and apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. (2009) 9:414. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-414

145. Kim SY, Park J-E, Kim EO, Lim SJ, Nam EJ, Yun JH, et al. Exposure of kale root to NaCl and Na2SeO3 increases isothiocyanate levels and Nrf2 signalling without reducing plant root growth. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:3999. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22411-9

146. Meng Y, Zhang Y, Jia N, Qiao H, Zhu M, Meng Q, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of a novel water-soluble high Se-enriched Astragalus polysaccharide nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. (2018) 118:1438–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.153

147. Sun H, Zhu Z, Tang Y, Ren Y, Song Q, Tang Y, et al. Structural characterization and antitumor activity of a novel Se-polysaccharide from selenium-enriched Cordyceps gunnii. Food Funct. (2018) 9:2744–54. doi: 10.1039/c8fo00027a

148. Liu X, Gao Y, Li D, Liu C, Jin M, Bian J, et al. The neuroprotective and antioxidant profiles of selenium-containing polysaccharides from the fruit of Rosa laevigata. Food Funct. (2018) 9:1800–8. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01725A

149. Chen D, Sun S, Cai D, Kong G. Induction of mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in T24 cells by a selenium (Se)-containing polysaccharide from Ginkgo biloba L. leaves. Int J Biol Macromol. (2017) 101:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.033

150. Yuan C, Wang C, Wang J, Kumar V, Anwar F, Xiao F, et al. Inhibition on the growth of human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in vitro and tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model by Se-containing polysaccharides from Pyracantha fortuneana. Nutr Res. (2016) 36:1243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.09.012

151. Bachiega P, Salgado JM, de Carvalho JE, Ruiz ALTG, Schwarz K, Tezotto T, et al. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities in different maturation stages of broccoli (Brassica oleracea) biofortified with selenium. Food Chem. (2016) 190:771–6. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.024

152. Oancea A, Craciunescu O, Gaspar A, Moldovan L, Seciu A-M, Utoiu E, et al. Chemopreventive Functional Food Through Selenium Biofortification Of Cauliflower Plants. Romania: Arad (2016).

153. Li W, He N, Tian L, Shi X, Yang X. Inhibitory effects of polyphenol-enriched extract from Ziyang tea against human breast cancer MCF-7 cells through reactive oxygen species-dependent mitochondria molecular mechanism. J Food Drug Anal. (2016) 24:527–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.01.005

154. Mattioli S, Dal Bosco A, Duarte JMM, D’Amato R, Castellini C, Beone GM, et al. Use of Selenium-enriched olive leaves in the feed of growing rabbits: effect on oxidative status, mineral profile and Selenium speciation of Longissimus dorsi meat. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2019) 51:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2018.10.004

155. Seo TC, Spallholz JE, Yun HK, Kim SW. Selenium-enriched garlic and cabbage as a dietary selenium source for broilers. J Med Food. (2008) 11:687–92. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.0053

156. Gao Z, Liu K, Tian W, Wang H, Liu Z, Li Y, et al. Effects of selenizing angelica polysaccharide and selenizing garlic polysaccharide on immune function of murine peritoneal macrophage. Int Immunopharmacol. (2015) 27:104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.04.052

157. Hama H, Yamanoshita O, Chiba M, Takeda I, Nakajima T. Selenium-enriched Japanese radish sprouts influence glutathione peroxidase and glutathione S-transferase in an organ-specific manner in rats. J Occup Health. (2008) 50:147–54. doi: 10.1539/joh.L7130

158. Chantiratikul A, Pakmaruek P, Chinrasri O, Aengwanich W, Chookhampaeng S, Maneetong S, et al. Efficacy of Selenium from Hydroponically Produced Selenium-Enriched Kale Sprout (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra L.) in Broilers. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2015) 165:96–102. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0227-5

159. Zeng Z, Xu Y, Zhang B. Antidiabetic activity of a lotus leaf selenium (Se)-polysaccharide in rats with gestational diabetes mellitus. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2017) 176:321–7. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0829-6

160. Shao C, Song J, Zhao S, Jiang H, Wang B, Chi A. Therapeutic effect and metabolic mechanism of a selenium-polysaccharide from ziyang green tea on chronic fatigue syndrome. Polymers. (2018) 10:1269. doi: 10.3390/polym10111269

161. Haug A, Eich-Greatorex S, Bernhoft A, Hetland H, Sogn T. Selenium bioavailability in chicken fed selenium-fertilized wheat. Acta Agric Scand A Anim Sci. (2008) 58:65–70.

162. Liu W, Hou T, Shi W, Guo D, He H. Hepatoprotective effects of selenium-biofortified soybean peptides on liver fibrosis induced by tetrachloromethane. J Funct Foods. (2018) 50:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.09.034

163. Yan L, Johnson LK. Selenium bioavailability from naturally produced high-selenium peas and oats in selenium-deficient rats. J Agric Food Chem. (2011) 59:6305–11. doi: 10.1021/jf201053s

164. Yan L, Reeves PG, Johnson LK. Assessment of selenium bioavailability from naturally produced high-selenium soy foods in selenium-deficient rats. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2010) 24:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2010.04.002

165. Li Q, Chen G, Chen H, Zhang W, Ding Y, Yu P, et al. Se-enriched G. frondosa polysaccharide protects against immunosuppression in cyclophosphamide-induced mice via MAPKs signal transduction pathway. Carbohydr Polym. (2018) 196:445–56. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.05.046

166. Liu M, Meng G, Zhang J, Zhao H, Jia L. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities of mycelia selenium polysaccharide by hypsizigus marmoreus SK-02. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2016) 172:437–48. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0613-z

167. Yuan C, Li Z, Yi M, Wang X, Peng F, Xiao F, et al. Effects of polysaccharides from selenium-enriched Pyracantha fortuneana on mice liver injury. Med Chem. (2015) 11:780–8. doi: 10.2174/1573406411666150602153357

168. Liu Y, Li C, Luo X, Han G, Xu S, Niu F, et al. Characterization of selenium-enriched mycelia of Catathelasma ventricosum and their antihyperglycemic and antioxidant properties. J Agric Food Chem. (2015) 63:562–8. doi: 10.1021/jf5050316

169. Maseko T, Howell K, Dunshea FR, Ng K. Selenium-enriched Agaricus bisporus increases expression and activity of glutathione peroxidase-1 and expression of glutathione peroxidase-2 in rat colon. Food Chem. (2014) 146:327–33. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.074

170. da Silva MCS, Naozuka J, Oliveira PV, Vanetti MCD, Bazzolli DMS, Costa NMB, et al. In vivo bioavailability of selenium in enriched Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms. Metallomics. (2010) 2:162–6. doi: 10.1039/B915780H

171. Kouba A, Velíšek J, Stará A, Masojídek J, Kozák P. Supplementation with sodium selenite and selenium-enriched microalgae biomass show varying effects on blood enzymes activities, antioxidant response, and accumulation in common barbel (Barbus barbus). Biomed Res. Int. (2014) 2014:408270. doi: 10.1155/2014/408270

172. Yang B, Wang D, Wei G, Liu Z, Ge X. Selenium-enriched Candida utilis: efficient preparation with l-methionine and antioxidant capacity in rats. J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2013) 27:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.06.001

173. Nido SA, Shituleni SA, Mengistu BM, Liu Y, Khan AZ, Gan F, et al. Effects of selenium-enriched probiotics on lipid metabolism, antioxidative status, histopathological lesions, and related gene expression in mice fed a high-fat diet. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2016) 171:399–409. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0552-8

174. Gan F, Chen X, Liao SF, Lv C, Ren F, Ye G, et al. Selenium-enriched probiotics improve antioxidant status, immune function, and selenoprotein gene expression of piglets raised under high ambient temperature. J Agric Food Chem. (2014) 62:4502. doi: 10.1021/jf501065d

175. Liu Y, Liu Q, Ye G, Khan A, Liu J, Gan F, et al. Protective effects of selenium-enriched probiotics on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats. J Agric Food Chem. (2015) 63:242–9. doi: 10.1021/jf5039184

176. Warrington JM, Kim JJM, Stahel P, Cieslar SRL, Moorehead RA, Coomber BL, et al. Selenized milk casein in the diet of BALB/c nude mice reduces growth of intramammary MCF-7 tumors. BMC Cancer. (2013) 13:492. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-492

177. Hu Y, McIntosh GH, Le Leu RK, Young GP. Selenium-enriched milk proteins and selenium yeast affect selenoprotein activity and expression differently in mouse colon. Br J Nutr. (2010) 104:17–23. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000309

178. Li K, Cao Z, Guo Y, Tong C, Yang S, Long M, et al. Selenium yeast alleviates ochratoxin a-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress via modulation of the PI3K/AKT and Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathways in the kidneys of chickens. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2020) 2020:4048706. doi: 10.1155/2020/4048706

179. Tong C, Li P, Yu L-H, Li L, Li K, Chen Y, et al. Selenium-rich yeast attenuates ochratoxin A-induced small intestinal injury in broiler chickens by activating the Nrf2 pathway and inhibiting NF-KB activation. J Funct Foods. (2020) 66:103784. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103784

180. Porto BAA, Monteiro CF, Souza ÉLS, Leocádio PCL, Alvarez-Leite J I, Generoso SV, et al. Treatment with selenium-enriched Saccharomyces cerevisiae UFMG A-905 partially ameliorates mucositis induced by 5-fluorouracil in mice. Chemother Pharmacol. (2019) 84:117–26. doi: 10.1007/s00280-019-03865-8