- 1International Ph.D. Program in Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 3Faculty of Public Health, Hai Phong University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hai Phong, Vietnam

- 4Department of Clinical Nutrition, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 5Department of Nutrition, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 6School of Public Health, College of Public Health, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

- 7President Office, Hai Phong University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hai Phong, Vietnam

- 8Institute of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 9Center for Assessment and Quality Assurance, Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 10Department of Infectious Diseases, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 11Division of Military Science, Military Hospital 103, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 12Faculty of Public Health, Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam

- 13Pham Ngoc Thach Clinic, Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam

- 14President Office, Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam

- 15Department of Psychiatry, Thai Nguyen University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam

- 16Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Can Tho, Vietnam

- 17Department of Pharmacy, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hospital, Can Tho, Vietnam

- 18President Office, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Can Tho, Vietnam

- 19Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Can Tho, Vietnam

- 20Institute for Community Health Research, University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hue University, Hue, Vietnam

- 21School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 22School of Nutrition and Health Sciences, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

Background: Medical students' health and wellbeing are highly concerned during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study examined the impacts of fear of COVID-19 (FCoV-19S), healthy eating behavior, and health-related behavior changes on anxiety and depression.

Methods: We conducted an online survey at 8 medical universities in Vietnam from 7th April to 31st May 2020. Data of 5,765 medical students were collected regarding demographic characteristics, FCoV-19S, health-related behaviors, healthy eating score (HES), anxiety, and depression. Logistic regression analyses were used to explore associations.

Results: A lower likelihood of anxiety and depression were found in students with a higher HES score (OR = 0.98; 95%CI = 0.96, 0.99; p = 0.042; OR = 0.98; 95%CI = 0.96, 0.99; p = 0.021), and in those unchanged or more physical activities during the pandemic (OR = 0.54; 95%CI = 0.44, 0.66; p < 0.001; OR = 0.44; 95%CI = 0.37, 0.52; p < 0.001) as compared to those with none/less physical activity, respectively. A higher likelihood of anxiety and depression were reported in students with a higher FCoV-19S score (OR = 1.09; 95%CI = 1.07, 1.12; p < 0.001; OR = 1.06; 95%CI = 1.04, 1.08; p < 0.001), and those smoked unchanged/more during the pandemic (OR = 6.67; 95%CI = 4.71, 9.43; p < 0.001; OR = 6.77; 95%CI = 4.89, 9.38; p < 0.001) as compared to those stopped/less smoke, respectively. In addition, male students had a lower likelihood of anxiety (OR = 0.79; 95%CI = 0.65, 0.98; p = 0.029) compared to female ones.

Conclusions: During the pandemic, FCoV-19S and cigarette smoking had adverse impacts on medical students' psychological health. Conversely, staying physically active and having healthy eating behaviors could potentially prevent medical students from anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been causing the ever-increasing number of confirmed cases and deaths worldwide (1), placing a huge burden on the healthcare system (2–4). Amidst the pandemic, healthcare workers (HCWs) have directly involved in providing care and treatment for COVID-19 patients. The HCWs have faced stressful challenges, including lack of experience, overwhelming workload, shortages of personal protective equipment, and fear of contagion for their loved ones (5–7). Besides, long working hours and under high-pressure situations make HCWs physically and mentally exhausted which may also increase the risk of infection. In addition to frontline HCWs, most medical staff, regardless of their profession, have experienced remarkable changes in their working conditions and time, and a lack of interaction with colleagues and patients (8). These factors may significantly contribute to the development of psychological burdens among healthcare staff. Recent scientific literature also showed that HCWs were at increased risk of developing psychological illnesses during the COVID-19 crisis (7, 9, 10). Medical students are the future health workforce for the medical system, they had significant roles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic (11–15), their mental health requires more attention and additional support.

Unlike students studying in other disciplines, medical students have been reported to have a greater risk of developing psychological disorders during the pandemic (16–18). Before the pandemic, factors influencing their mental health were documented, including heavy academic programs, rigorous exams, work-life imbalance, the difficulty in adapting to clinical environments and exposing to critically ill and dying patients (19, 20). During the pandemic, Vietnam has adopted various preventive measures to control the spread of COVID-19, including a nationwide lockdown from April 1–20, 2020 (21, 22). Since educational institutions had to be closed for a long time (23), education programs transitioned from the classroom learning to the online learning (24). Meanwhile, medical students have to perform practical training, online studying may affect their academic progress. Besides, prevention measures (e.g., lockdown, and home quarantine) could cause feelings of isolation, leading to harmful lifestyles (25–27). These factors may have negative impacts on their psychological health. Therefore, it is essential to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of medical students, thereby promoting appropriate strategies to help them reduce the risk of developing mental disorders during the pandemic.

The uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic can cause increased fear in the community. Previous studies indicated that there were high rates of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic (28–30). In addition, COVID-19-related fear was found to be positively associated with mental disorders (31, 32). Particularly, medical students have a better knowledge of the disease and its severity, making them more fearful and worried during the pandemic (33). Therefore, anxiety and depression in relation to the fear of COVID-19 should be investigated in medical students to assess their mental health.

Engaging in positive lifestyles (e.g., healthy diet, staying physically active, avoiding alcohol and smoking) were documented to have benefits for mental health (34, 35). However, when facing the unfamiliar situations that the COVID-19 pandemic and preventive measures (e.g., lockdown), people had an increased tendency to consume alcohol and smoke cigarettes as a coping method (36–38). In addition, a recent systematic review of 87 articles indicated that there were increased food and alcohol consumption, and increased sedentary hours during the COVID-19 pandemic (39, 40). Another research also showed that a higher intake of unhealthy foods was documented during the lockdown period (40). The changes of lifestyle may further affect people's psychological health. Therefore, health-related behaviors should be investigated as independent variables for medical student's mental health.

Previous literature indicated that the prevalence of anxiety and depression varied across demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, income, education (41, 42). In the context of the pandemic, several health-related factors were reported to be important predictors of mental disorders, such as underlying health conditions, symptoms like COVID-19, or BMI (41–43). In addition, recent studies also showed that higher digital healthy diet literacy (DDL) and health literacy (HL) were associated with better mental health in different populations (e.g., healthcare workers, and outpatients) (43–45). Therefore, DDL and HL may have potential impacts on anxiety and depression among medical students during the pandemic.

This study was conducted to examine the associated factors of anxiety and depression among undergraduate medical students, in which impacts of fear of COVID-19, health-related behavior changes and healthy eating behaviors were emphasized.

Methods

Study design and sample

We conducted a cross-sectional study among medical students at 8 medical universities across Vietnam, including 5 universities in the Northern area, 1 university in the Central area, and 2 universities in the Southern area. An online questionnaire survey was carried out to collect data from 7th April to 31st May 2020. A sample of 5,765 students (out of 28,737 possible students) completed the online survey (46).

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Ethical Review Committee of Hanoi University of Public Health, Vietnam (IRB No. 133/2020/YTCC-HD3).

We used a convenience sampling method to recruit medical students. Researchers (university lecturers) informed and invited their students to participate in the survey. Next, the online survey link was sent to student leaders, who were responsible for sharing the link with other students in their class via email, Facebook messenger, or Zalo. Study purposes were informed to students before they signed the electronic consent forms. Students then completed all the survey questions. There was no missing data as marking required fields for all the questions. Students' data is kept confidential and used for research purposes only.

Measurements

Outcome variables

Anxiety and depression were assessed using the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire and the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), respectively. The original translated versions of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were used in this study and in the Vietnamese context (47–49). In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha values for the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 questionnaires were 0.94 and 0.91, respectively. These questionnaires investigate participants about the extent to which different symptoms of anxiety and depression bothered them in the last 2 weeks with four possible responses from “0 = not at all” to “3 = almost every day”. A sum GAD-7 score (a range of 0–21) of ≥ 8 was classified as anxiety (50). Similarly, a sum PHQ-9 score (a range of 0–27) of ≥ 10 was classified as depression (51).

Fear of COVID-19

We used the 7-item fear of COVID-19 scale (FCoV-19S) to evaluate fear. This instrument was validated and used in Vietnamese medical students in a previous study (52). Students were asked to rate their agreements with varying degrees of the COVID-19 related fear. The possible answers range from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”. The sum scores varied between 7 and 35, in which students with higher scores have greater degrees of FCoV-19S.

Healthy eating behavior

We used the healthy eating score (HES-5) questionnaire to evaluate healthy eating behavior (53, 54). This instrument consists of 5 food items, which investigate how often students consumed these foods in the last 30 days, including vegetables, fruits, fish, whole grains, and dairy products. The frequency of food consumption ranges from 0 (rarely or never) to 5 (three or more times every day). The sum score of HES is between 0 and 25, in which students with higher scores have healthier eating habits. This tool was validated and used for assessing a healthy diet in different Vietnamese populations (44, 47). The Cronbach's alpha for HES-5 in the current study was 0.73.

Health-related behavior changes

Students reported their health behaviors amidst the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic, including cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity with five choices (never, quitted/stopped, less, unchanged, and more); and eating habits with 3 choices (less healthy, unchanged, and healthier). It is recommended that people should maintain or make better positive behaviors (e.g., physical activity, healthy diet) to stay healthy during the pandemic. Inversely, harmful behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking) should be abandoned or reduced gradually (55). Therefore, we classified health-related behavior changes into two categories as follows: cigarette smoking (“none or smoke less” vs. “unchanged or smoke more”), alcohol drinking (“none or drink less” vs. “unchanged or drink more”), physical activity (“none or less active” vs. “unchanged or more active”) and eating habits (“unchanged or less healthy” vs. “healthier”).

Digital healthy diet literacy and health literacy

We used the 4-item digital healthy diet literacy questionnaire (DDL-4) and 12-item short-form health literacy questionnaire (HLS-SF12) to evaluate student's digital healthy diet literacy (DDL) and health literacy (HL). The DDL-4 was developed, validated, and used in previous studies during the pandemic (44, 46, 56), while the HLS-SF12 was commonly utilized for research in Asian nations (57) and Vietnam (58–62). The Cronbach's alpha for the DDL-4 and HLS-SF12 in our study were 0.87 and 0.89, respectively. Students rated their performance difficulty for each questionnaire item on four-level responses ranging from “1 = very difficult” to “4 = very easy”. We standardized the DDL and HL scores into unified metrics ranging from 0 to 50, in which students with higher DDL scores or higher HL scores have better DDL or HL. The standardized formula was represented in previous research (46, 57).

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Data related to student's characteristics were also collected, including age, sex (female vs. male), ability to pay for medical care (easy vs. difficult), and academic year (1–2 vs. 3–6). Bodyweight (kg) and height (cm) were self-reported by students, which were used to calculate body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). We used the Charlson Comorbidity Index items (63) to evaluate underlying health conditions (none vs. one or more). Students also reported Suspected COVID-19 symptoms (S-COVID-19-S) that they had at the time of the survey. These symptoms include fever, cough, difficult breathing, myalgia, fatigue, sputum production, confusion, headache, sore throat, rhinorrhea, chest pain, hemoptysis, diarrhea, and nausea (64). Students had S-COVID-19-S if they had at least one of S-COVID-19-S.

Data analysis

First, descriptive analyses were used to summarize the features of independent variables (IVs), including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. Second, we used the Chi-squared test to compare the distribution of anxiety and depression according to different groups of IVs. Third, simple and multiple logistic regression models were conducted to explore the associated predictors of anxiety and depression in medical students. We chose variables related to outcomes at p < 0.1 in bivariate models to perform multivariate models. The Spearman correlation test was utilized to test relationships between IVs to deal with multicollinearity. We found that age highly correlates with the academic year (rho = 0.82); cigarette smoking moderately correlates with alcohol drinking (rho = 0.49); health literacy moderately correlates with the DDL (rho = 0.63) (Supplementary Table S1). Thus, age, gender, cigarette smoking, health literacy, and other independent factors were included in the multiple logistic regression models. We set p-value < 0.05 as a significant level. All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States).

Results

Student's characteristics

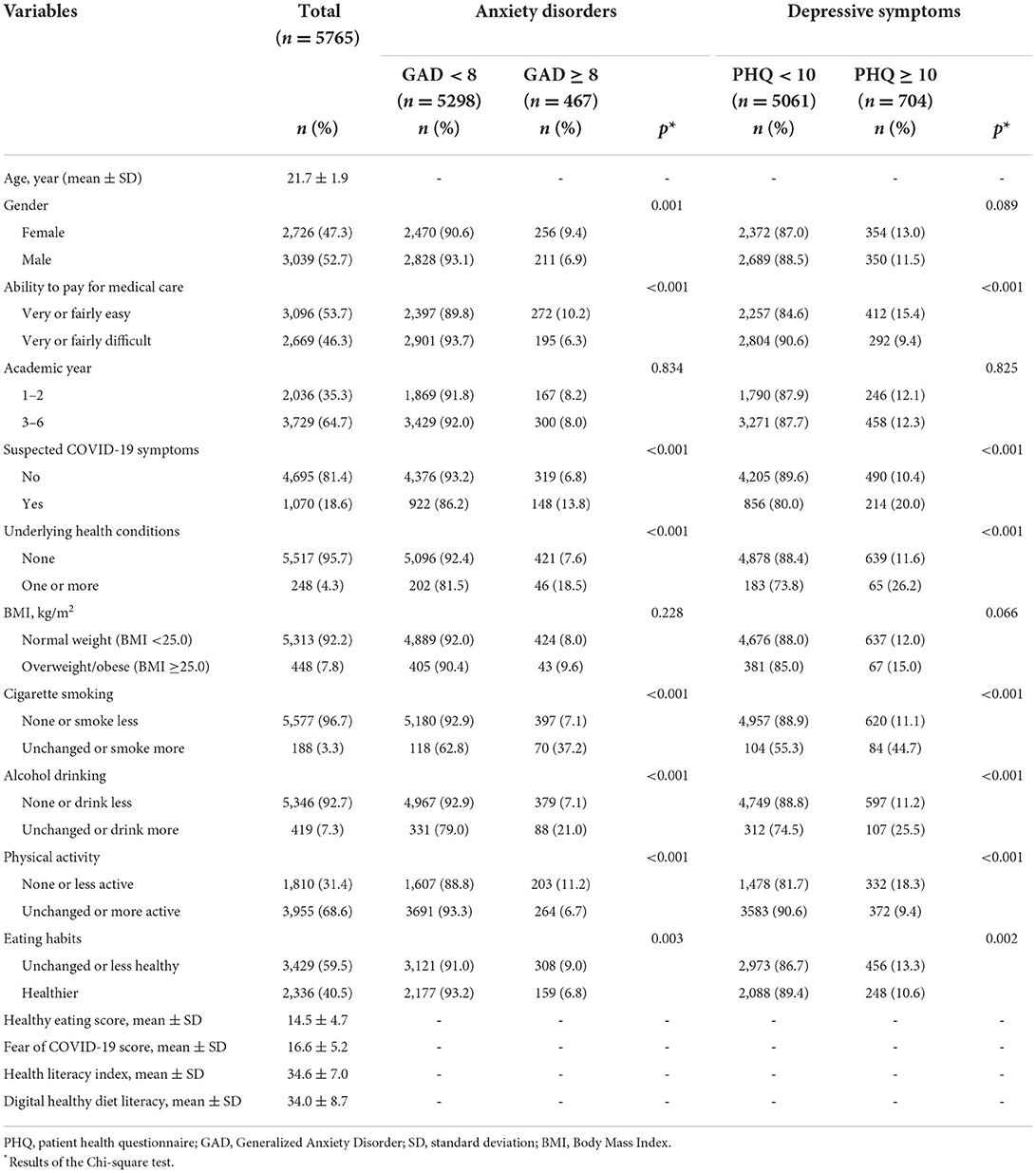

The average age of the sample was 21.7 ± 1.9. Out of all participants, 47.3% were female, 46.3% responded to difficult payment for medical care, and 35.3% were first-year or second-year students. The mean score of FCoV-19S was 16.6 ± 5.2. The prevalence of anxiety and depression was 8.1 and 12.2%, respectively. The proportion of anxiety varied by different groups of gender, ability to pay for medical care, S-COVID-19-S, underlying health conditions, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and eating habits. The proportion of depression varied by different groups of ability to pay for medical care, S-COVID-19-S, underlying health conditions, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and eating habits (Table 1).

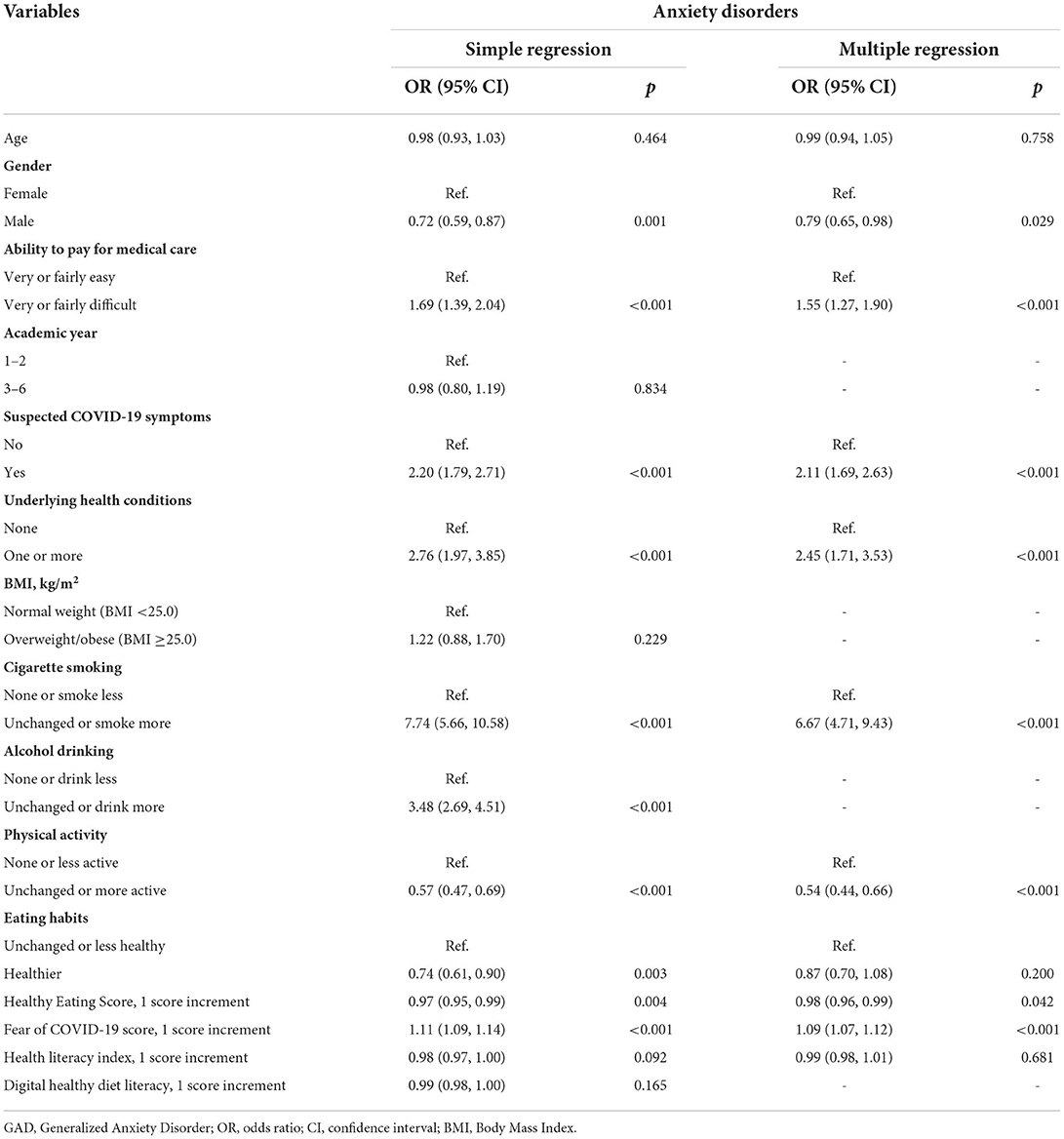

Associated factors of anxiety among medical students

The multiple logistic regression models show that medical students had a lower likelihood of anxiety were male (odds ratio, OR: 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 95% CI: 0.65, 0.98; p = 0.029), those with higher healthy eating scores (OR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96, 0.99; p = 0.042) and those with unchanged or more physical activity (OR: 0.54; 95%CI: 0.44, 0.66; p < 0.001) as compared to those with none or less physical activity during the pandemic. Whereas, medical students had a higher likelihood of anxiety were those who found it difficult to pay for medical care (OR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.27, 1.90; p < 0.001), those with symptoms like COVID-19 (OR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.69, 2.63; p < 0.001), those with one one more underlying health conditions (OR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.71, 3.53; p < 0.001), those with unchanged or more smoking during the pandemic (OR: 6.67; 95% CI: 4.71, 9.43; p < 0.001), and those with higher fear of COVID-19 scores (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.12; p < 0.001), as compared to their counterparts (Table 2).

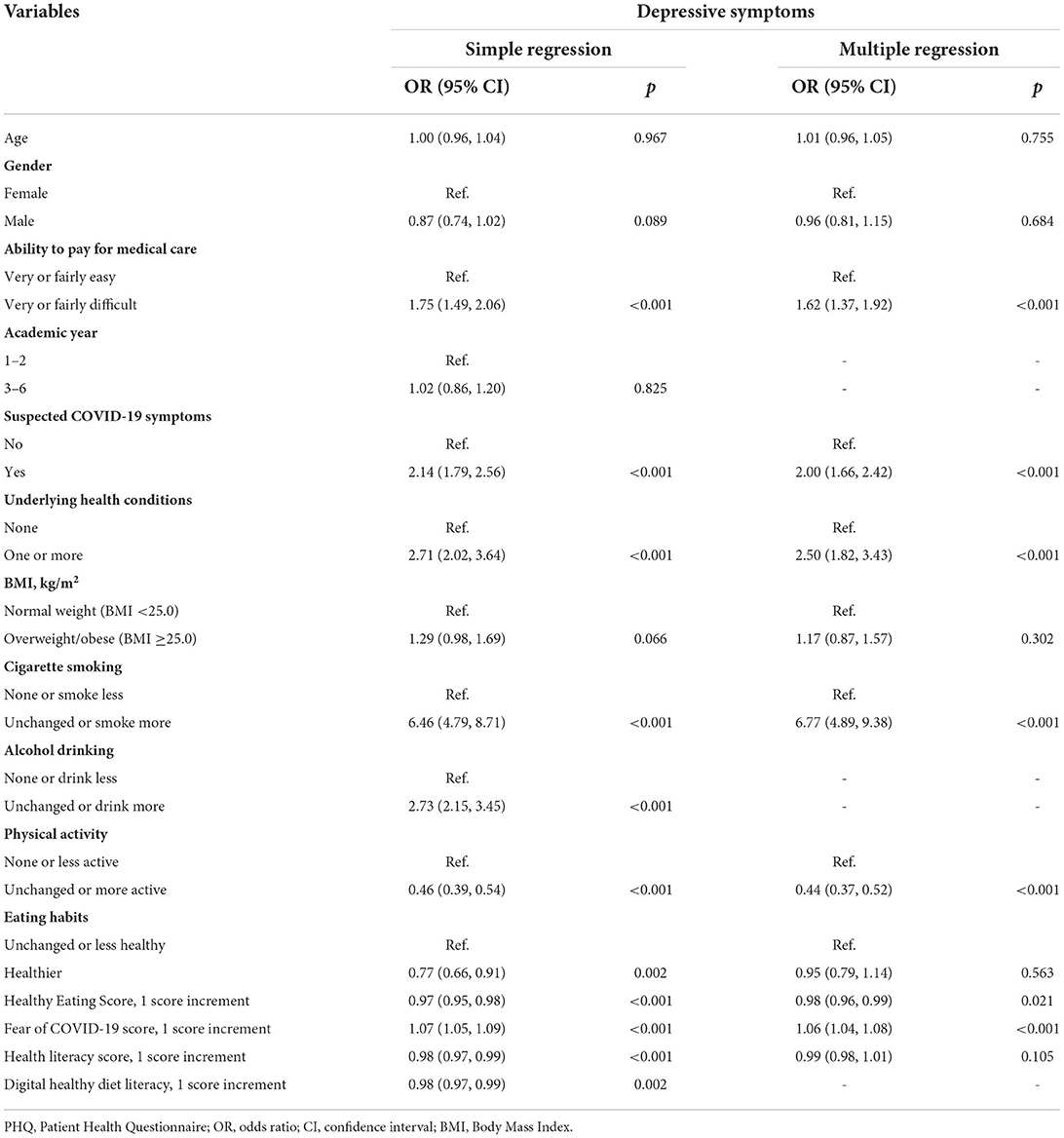

Associated factors of depression among medical students

The multiple logistic regression models indicate that medical students had lower odds of depression were those with higher healthy eating scores (OR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96, 0.99; p = 0.021), those with unchanged or more physical activity (OR: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.52; p < 0.001) as compared to those with none or less physical activity during the pandemic. Whereas, medical students had higher odds of depression were those who found it difficult to pay for medical care (OR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.37, 1.92; p < 0.001), those with COVID-19-like symptoms (OR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.66, 2.42; p < 0.001), those with one one more underlying health conditions (OR: 2.50; 95% CI: 1.82, 3.43; p < 0.001), those with unchanged or more smoking during the pandemic (OR: 6.77; 95% CI: 4.89, 9.38; p < 0.001), those with higher fear of COVID-19 scores (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.08; p < 0.001), as compared to their counterparts (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, our results indicate that medical students with higher fear of COVID-19 were more likely to have mental disorders. Our finding was consistent with recent literature conducted in China, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates among university students (65–67). It is understandable that medical students have a better knowledge of the disease, making them more aware of the severity and danger of the virus. Especially, students in clinical training years are required to work in teaching hospitals and emergency units, which are high-risk environments. Therefore, students may feel more anxious and depressed because they are at higher risk of getting infected and may pass the virus on to loved ones. This explanation also partially elucidates the result of this study that students with symptoms resembling COVID-19 were prone to be anxious and depressed. Previous studies conducted on different populations, such as outpatients, HCWs also reported similar results (41, 43, 48). In addition, we found that underlying health conditions were positively associated with anxiety and depression, which was in line with the findings of recent studies (42, 48, 68). The explanation for this association is that medical students have a better understanding of the disease. Therefore, they know that underlying medical conditions may worsen health outcomes after COVID-19 infections (69), making students with comorbidities more anxious and depressed during the period of the pandemic. Thus, psychological supports that mitigate the fear and enhance mental resilience could be essential to prevent medical students from developing anxiety or depressive symptoms.

The result of this study shows that medical students who smoked unchanged or more during the pandemic were more likely to be anxious and depressed. Our result was in line with previous studies conducted during the pandemic (49, 70). It is reported that smoking is quite common among medical students, especially among male students (71, 72). Although, smoking could help to relieve stress and pressure when facing uncomfortable events, especially in hospital settings. However, the long-term effects of smoking on the development of later anxiety and depression have been demonstrated in various studies (73). In addition, the present study found that maintaining physical activity unchanged or more active during the pandemic could help to prevent medical students from mental disorders. Similar findings were found in other studies carried out in Australia, North America, Brazil, and China among different populations during the pandemic (70, 74–76). Furthermore, physical activity was highly recommended for depression treatment (77). Regular exercise could help to enhance immune function (78–80), which prevents the body from pathogens, improving physical and mental health during the pandemic. This study also highlights the role of healthy eating behaviors in protecting medical students against the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The beneficial effect of a healthy diet on psychological health was reported in recent literature (35, 47, 48). Recent research on college students carried out during a home-confinement period in Italy indicated that healthy dietary behaviors were negatively linked with poorer mental states (81). However, restrictions to outdoor activities and daily lives caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to weight gain, and adversely influence eating habits, and sleeping patterns, thereby increasing eating disorder risk and symptoms (82, 83). In addition, due to precaution measures applied during the pandemic, people were more likely to engage in harmful lifestyles (e.g., increased screen time and sedentary behaviors, or increased alcohol consumption) (25, 39, 40). Therefore, our findings related to health-related behaviors provide timely evidence that helps to encourage medical school students to engage in positive lifestyle habits, reducing the likelihood of mental disorders during the pandemic.

Moreover, we found that male medical students had a lower likelihood of developing anxiety than their female colleagues. This result is similar to previous studies conducted in the United States, Bangladeshi among medical students (84, 85). Our study also indicated that medical students who responded to payment difficulty for medical care had higher odds of anxiety and depressive symptoms than their counterparts, which is comparable to the findings of other studies conducted on outpatients and HCWs during the pandemic (47, 49). The difficult affordability of healthcare may lead to delays in examinations and treatments, which negatively affect students' physical and mental health. It may also partially reflex the financial constraints (86). Particularly, the unemployment rate was higher during the pandemic, affecting the household income (87, 88), making medical students more worried and stressed about the cost of living, rent, and education. Therefore, medical universities should consider strategies to assess and support the psychological health of vulnerable demographic groups, including medical students who are female and who find it difficult to pay for healthcare.

Our study was strengthened by its large sample size collected from 8 medical universities across Vietnam. It is also the first study to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on mental health among medical students in Vietnam. Therefore, this pilot study could provide timely evidence for future research and practices to protect mental health against the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some limitations need to be acknowledged in this paper. First, the causality of the associations could not be inferred in the study with a cross-sectional design. Second, as students recruited in the survey were not randomly selected, the generalization of these results should be applied cautiously to medical school students. Final, several factors, which may affect outcomes, were not investigated in this study, such as the changes in teaching methods, financial problems, history of mental disorders, relationships with friends and family, and academic workload. Future studies should take these variables into consideration in assessments.

Conclusions

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, medical students with higher fear scores were more likely to have anxiety and depression. Students who smoked had a higher likelihood of having anxiety and depression. Fortunately, staying physically active and having healthy eating behavior were found to be protective factors of mental health among medical students. Medical universities should develop strategic programs to encourage students to actively engage in physical activity, healthy diet, and avoid smoking, which could prevent medical students from psychological disorders during the pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Committee of Hanoi University of Public Health, Vietnam (IRB No. 133/2020/YTCC-HD3). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MHN, TXD, ThTN, MDP, TTMP, KMP, GBK, BND, HTN, N-MN, HTBD, YHN, KTN, TTPN, TrTN, and TVD: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, and writing-review and editing draft. MHN, TD, and TD: formal analysis and writing-original draft. MHN, TTMP, and TTPN: project administration. TD: funding acquisition, supervision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Taipei Medical University and Military Hospital 103 (108-6202-008-112; 108-3805-022-400).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all experts and research assistants who helped with data collection. We also appreciate and acknowledge the participation of medical students from eight medical universities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.938769/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organisation. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. (2021). Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed May 15, 2022).

2. Miller IF, Becker AD, Grenfell BT, Metcalf CJE. Disease and healthcare burden of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1212–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0952-y

3. World Health Organisation Attacks on health care in the context of COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/attacks-on-health-care-in-the-context-of-covid-19 (accessed June 15, 2021).

4. Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR. Covid-19 - implications for the health care system. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:1483–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2021088

5. Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. (2020) 368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211

6. Walton M, Murray E, Christian MD. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. (2020) 9:241–7. doi: 10.1177/2048872620922795

7. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

8. Greenberg N. Mental health of health-care workers in the COVID-19 era. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2020) 16:425–6. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0314-5

9. Asnakew S, Amha H, Kassew T. Mental Health Adverse Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in north west ethiopia: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:1375–84. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S306300

10. Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LLL, et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:317–20. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083

11. Bauchner H, Sharfstein J. A Bold Response to the COVID-19 pandemic: medical students, national service, and public health. JAMA. (2020) 323:1790–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6166

12. Representatives Representatives of the Starsurg Collaborative EC, Collaborative T. Medical student involvement in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. (2020) 395:1254. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30795-9

13. Klasen JM, Meienberg A, Nickel C, Bingisser R. SWAB team instead of SWAT team: Medical students as a frontline force during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Educ. (2020) 54:860. doi: 10.1111/medu.14224

14. Rasmussen S, Sperling P, Poulsen MS, Emmersen J, Andersen S. Medical students for health-care staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. (2020) 395:e79–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30923-5

15. Gallagher TH, Schleyer AM. “We Signed Up for This!” - Student and Trainee Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:e96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005234

16. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR. Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. (2006) 81:354–73. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009

17. Mousa OY, Dhamoon MS, Lander S, Dhamoon AS. The MD Blues: Under-Recognized Depression and Anxiety in Medical Trainees. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0156554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156554

18. Quek TT, Tam WW, Tran BX, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Ho CS, et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2735. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152735

19. Hill MR, Goicochea S, Merlo LJ. In their own words: stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med Educ Online. (2018) 23:1530558. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1530558

20. Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, Wang X, et al. systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:327. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2

21. Prime Minister of Vietnam PM orders strict nationwide social distancing rules starting April 1. (2020). Available online at: https://vietnamlawmagazine.vn/pm-orders-strict-nationwide-social-distancing-rules-starting-april-1–27108.html (accessed March 31, 2020).

22. Prime Minister of Vietnam Gov't extends social distancing for at least one week in 28 localities. (2020). Available online at: http://news.chinhphu.vn/Home/Govt-extends-social-distancing-for-at-least-one-week-in-28-localities/20204/39735.vgp (accessed April 20, 2020).

23. Vietnam News COVID-19 caused university students untimely graduation. (2022). Available online at: https://vietnamnews.vn/society/1116137/covid-19-caused-university-students-untimely-graduation.html (accessed January 17, 2022).

24. Sahu P. Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus. (2020) 12:e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541

25. Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients. (2020) 12:1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583

26. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing: The Need for Prevention and Early Intervention. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:817–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

27. Giallonardo V, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Albert U, Carmassi C, et al. The Impact of Quarantine and Physical Distancing Following COVID-19 on Mental Health: Study Protocol of a Multicentric Italian Population Trial. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:533. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00533

28. Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

29. Necho M, Tsehay M, Birkie M, Biset G, Tadesse E. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 67:892–906. doi: 10.1177/00207640211003121

30. Di Blasi M, Gullo S, Mancinelli E, Freda MF, Esposito G, Gelo OCG, et al. Psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 lockdown: A two-wave network analysis. J Affect Disord. (2021) 284:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.016

31. Lo Coco G, Gentile A, Bosnar K, Milovanović I, Bianco A, Drid P, et al. A Cross-Country Examination on the Fear of COVID-19 and the Sense of Loneliness during the First Wave of COVID-19 Outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:2586. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052586

32. Bakioglu F, Korkmaz O, Ercan H. Fear of COVID-19 and Positivity: Mediating Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 19:2369–82. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y

33. Liu J, Zhu Q, Fan W, Makamure J, Zheng C, Wang J. Online Mental Health Survey in a Medical College in China During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00459

34. Molendijk M, Molero P, Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño F, Van der Does W, Angel Martínez-González M. Diet quality and depression risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. (2018) 226:346–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022

35. Li Y, Lv MR, Wei YJ, Sun L, Zhang JX, Zhang HG, et al. Dietary patterns and depression risk: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 253:373–82. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.020

36. Sun Y, Li Y, Bao Y, Meng S, Sun Y, Schumann G, et al. Brief Report: Increased Addictive Internet and Substance Use Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Am J Addict. (2020) 29:268–70. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13066

37. Kosendiak A, Król M, Sciskalska M, Kepinska M. The Changes in Stress Coping, Alcohol Use, Cigarette Smoking and Physical Activity during COVID-19 Related Lockdown in Medical Students in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 19:302. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010302

38. Martínez-Cao C, de la Fuente-Tomás L, Menéndez-Miranda I, Velasco Á, Zurrón-Madera P, García-Álvarez L, et al. Factors associated with alcohol and tobacco consumption as a coping strategy to deal with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown in Spain. Addict Behav. (2021) 121:107003. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107003

39. Daniels NF, Burrin C, Chan T, Fusco F. A systematic review of the impact of the first year of COVID-19 on obesity risk factors: a pandemic fueling a pandemic? Curr Dev Nutr. (2022) 6:nzac011. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac011

40. Mignogna C, Costanzo S, Ghulam A, Cerletti C, Donati MB, de Gaetano G, et al. Impact of nationwide lockdowns resulting from the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on food intake, eating behaviours and diet quality: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. (2021) 13:388–423. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab130

41. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing MX, Goh YH, Ngiam NJH, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

42. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

43. Nguyen HC, Nguyen MH, Do BN, Tran CQ, Nguyen TTP, Pham KM, et al. People with suspected COVID-19 symptoms were more likely depressed and had lower health-related quality of life: the potential benefit of health literacy. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:965. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040965

44. Vu DN, Phan DT, Nguyen HC, Le LT, Nguyen HC, Ha TH, et al. Impacts of digital healthy diet literacy and healthy eating behavior on fear of COVID-19, changes in mental health, and health-related quality of life among front-line health care workers. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2656. doi: 10.3390/nu13082656

45. Zlotnick C, Dryjanska L, Suckerman S. Health literacy, resilience and perceived stress of migrants in Israel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Health. (2021) 37:1076–92. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2021.1921177

46. Duong TV, Pham KM, Do BN, Kim GB, Dam HTB, Le VT, et al. Digital Healthy Diet Literacy and Self-Perceived Eating Behavior Change during COVID-19 Pandemic among Undergraduate Nursing and Medical Students: A Rapid Online Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7185. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197185

47. Pham KM, Pham LV, Phan DT, Tran TV, Nguyen HC, Nguyen MH, et al. Healthy dietary intake behavior potentially modifies the negative effect of COVID-19 lockdown on depression: a hospital and health center survey. Front Nutr. (2020) 7:581043. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.581043

48. Nguyen MH, Pham TTM, Pham LV, Phan DT, Tran TV, Nguyen HC, et al. Associations of underlying health conditions with anxiety and depression among outpatients: modification effects of suspected COVID-19 symptoms, health-related and preventive behaviors. Int J Public Health. (2021) 66:634904. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.634904

49. Tran TV, Nguyen HC, Pham LV, Nguyen MH, Nguyen HC, Ha TH, et al. Impacts and interactions of COVID-19 response involvement, health-related behaviours, health literacy on anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e041394. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041394

50. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. (2007) 146:317–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

51. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

52. Nguyen HT, Do BN, Pham KM, Kim GB, Dam HTB, Nguyen TT, et al. Fear of COVID-19 Scale-Associations of Its Scores with Health Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors among Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:164.. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114164

53. Shams-White MM, Chui K, Deuster PA, McKeown NM, Must A. Investigating items to improve the validity of the five-item healthy eating score compared with the 2015 healthy eating index in a military population. Nutrients. (2019) 11:251. doi: 10.3390/nu11020251

54. Purvis DL, Lentino CV, Jackson TK, Murphy KJ, Deuster PA. Nutrition as a component of the performance triad: how healthy eating behaviors contribute to soldier performance and military readiness. US Army Med Dep J. (2013) 66–78. [Epub ahead of print].

55. World Health Organisation Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed May 10, 2020).

56. Nguyen MH, Pham TTM, Nguyen KT, Nguyen YH, Tran TV, Do BN, et al. Negative Impact of Fear of COVID-19 on health-related quality of life was modified by health literacy, ehealth literacy, and digital healthy diet literacy: a multi-hospital survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:4929. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094929

57. Duong TV, Aringazina A, Kayupova G, Nurjanah TV, Pham KM, et al. Development and validation of a new short-form health literacy instrument (HLS-SF12) for the general public in six asian countries health. Lit Res Pract. (2019) 3:e91–e102. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20190225-01

58. Duong TV, Nguyen TTP, Pham KM, Nguyen KT, Giap MH, Tran TDX, et al. Validation of the Short-Form Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLS-SF12) and Its Determinants among People Living in Rural Areas in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3346. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16183346

59. Van Hoa H, Giang HT, Vu PT, Van Tuyen D, Khue PM. Factors Associated with Health Literacy among the Elderly People in Vietnam. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:3490635. doi: 10.1155/2020/3490635

60. Do BN, Nguyen PA, Pham KM, Nguyen HC, Nguyen MH, Tran CQ, et al. Determinants of Health Literacy and Its Associations With Health-Related Behaviors, Depression Among the Older People With and Without Suspected COVID-19 Symptoms: A Multi-Institutional Study. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:581746. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.581746

61. Do BN, Tran TV, Phan DT, Nguyen HC, Nguyen TTP, Nguyen HC, et al. Health Literacy, eHealth Literacy, Adherence to Infection Prevention and Control Procedures, Lifestyle Changes, and Suspected COVID-19 Symptoms Among Health Care Workers During Lockdown: Online Survey. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e22894. doi: 10.2196/22894

62. Nguyen TT, Le NT, Nguyen MH, Pham LV, Do BN, Nguyen HC, et al. Health Literacy and Preventive Behaviors Modify the Association between Pre-Existing Health Conditions and Suspected COVID-19 Symptoms: A Multi-Institutional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:8598. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228598

63. Quan HD Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and Validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Score for Risk Adjustment in Hospital Discharge Abstracts Using Data From 6 Countries. Am J Epidemiol. (2011) 173:676–82. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433

64. BMJ Editorial Team Overview of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). (2020). BMJ Best Practice. Available online at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000165 (accessed March 10, 2020).

65. Saravanan C, Mahmoud I, Elshami W, Taha MH. Knowledge, Anxiety, Fear, and Psychological Distress About COVID-19 Among University Students in the United Arab Emirates. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:582189. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.582189

66. Tang W, Hu T, Hu B, Jin C, Wang G, Xie C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009

67. Perz CA, Lang BA, Harrington R. Validation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in a US College Sample. In: International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. (2020). p. 1–11.

68. Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, et al. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165

69. Jain V, Yuan JM. Predictive symptoms and comorbidities for severe COVID-19 and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. (2020) 65:533–46. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01390-7

70. Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, et al. Depression, Anxiety and Stress during COVID-19: Associations with Changes in Physical Activity, Sleep, Tobacco and Alcohol Use in Australian Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4065. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114065

71. Tamaki T, Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Yokoyama E, Osaki Y, Kanda H, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with smoking among Japanese medical students. J Epidemiol. (2010) 20:339–45. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090127

72. Vakeflliu Y, Argjiri D, Peposhi I, Agron S, Melani AS. Tobacco smoking habits, beliefs, and attitudes among medical students in Tirana, Albania. Prev Med. (2002) 34:370–3. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0994

73. Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafo MR. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. (2017) 19:3–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140

74. Xiang MQ, Tan XM, Sun J, Yang HY, Zhao XP, Liu L, et al. Relationship of physical activity with anxiety and depression symptoms in chinese college students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:582436. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582436

75. Callow DD, Arnold-Nedimala NA, Jordan LS, Pena GS, Won J, Woodard JL, et al. The mental health benefits of physical activity in older adults survive the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:1046–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.024

76. Schuch FB, Bulzing RA, Meyer J, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Stubbs B, et al. Associations of moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior with depressive and anxiety symptoms in self-isolating people during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in Brazil. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 292:113339. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113339

77. Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2016) 202:67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063

78. Laddu DR, Lavie CJ, Phillips SA, Arena R. Physical activity for immunity protection: Inoculating populations with healthy living medicine in preparation for the next pandemic. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2021) 64:102–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.006

79. Davison G, Kehaya C, Wyn Jones A. Nutritional and Physical Activity Interventions to Improve Immunity. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2016) 10:152–69. doi: 10.1177/1559827614557773

80. Ranasinghe C, Ozemek C, Arena R. Exercise and well-being during COVID 19 - time to boost your immunity. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2020) 18:1195–200. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1794818

81. Amatori S, Donati Zeppa S, Preti A, Gervasi M, Gobbi E, Ferrini F, et al. Dietary Habits and Psychological States during COVID-19 Home Isolation in Italian College Students: The Role of Physical Exercise. Nutrients. (2020) 12:3660. doi: 10.3390/nu12123660

82. Rodgers RF, Lombardo C, Cerolini S, Franko DL, Omori M, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1166–70. doi: 10.1002/eat.23318

83. Sideli L, Lo Coco G, Bonfanti RC, Borsarini B, Fortunato L, Sechi C, et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on eating disorders and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2021) 29:826–41. doi: 10.1002/erv.2861

84. Safa F, Anjum A, Hossain S, Trisa TI, Alam SF, Abdur Rafi M, et al. Immediate psychological responses during the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi medical students. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2021) 122:105912. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105912

85. Halperin SJ, Henderson MN, Prenner S, Grauer JN. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Among Medical Students During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Educ Curric Dev. (2021) 8:2382120521991150. doi: 10.1177/2382120521991150

86. Russell S. Ability to pay for health care: concepts and evidence. Health Policy Plan. (1996) 11:219–37. doi: 10.1093/heapol/11.3.219

88. World Health Organisation Impact of COVID-19 on people's livelihoods their health our food systems. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/13–10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people%27s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems (accessed June 15 2021).

Keywords: fear, COVID-19, smoking, physical activity, healthy eating behavior, anxiety, depression, medical students

Citation: Nguyen MH, Do TX, Nguyen TT, Pham MD, Pham TTM, Pham KM, Kim GB, Do BN, Nguyen HT, Nguyen N-M, Dam HTB, Nguyen YH, Nguyen KT, Nguyen TTP, Nguyen TT and Duong TV (2022) Fear of COVID-19, healthy eating behaviors, and health-related behavior changes as associated with anxiety and depression among medical students: An online survey. Front. Nutr. 9:938769. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.938769

Received: 08 May 2022; Accepted: 22 August 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Mauro Serafini, University of Teramo, ItalyReviewed by:

Gianluca Lo Coco, University of Palermo, ItalySyeda Mehpara Farhat, National University of Medical Sciences (NUMS), Pakistan

Copyright © 2022 Nguyen, Do, Nguyen, Pham, Pham, Pham, Kim, Do, Nguyen, Nguyen, Dam, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Duong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tuyen Van Duong, dHZkdW9uZ0B0bXUuZWR1LnR3

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Minh H. Nguyen

Minh H. Nguyen Tinh X. Do2†

Tinh X. Do2† Tham T. Nguyen

Tham T. Nguyen Thu T. M. Pham

Thu T. M. Pham Khue M. Pham

Khue M. Pham Giang B. Kim

Giang B. Kim Binh N. Do

Binh N. Do Yen H. Nguyen

Yen H. Nguyen Thao T. P. Nguyen

Thao T. P. Nguyen Tuyen Van Duong

Tuyen Van Duong