- 1College of Textile and Clothing Engineering, Soochow University, Suzhou, China

- 2Shanghai Jing Rui Yang Industrial Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China

- 3Shanghai Nutri-woods Bio-Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China

- 4Shanghai Pechoin Daily Chemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China

- 5Shanghai Institute of Spacecraft Equipment, Shanghai, China

Background: Nanomaterials, widely applied in various fields, are reported to have toxic effects on human beings; thus, preventive or therapeutic measures are urgently needed. Given the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, supplementation with flavonoids that are abundant in the human diet has been suggested as a potential strategy to protect against nanomaterial-induced toxicities. However, the beneficial effects of flavonoids remain inconclusive. In the present study, we performed a meta-analysis to comprehensively explore the roles and mechanisms of flavonoids for animals intoxicated with nanomaterials.

Methods: A systematic literature search in PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases was performed up to April 2022. STATA 15.0 software was used for meta-analyses.

Results: A total of 26 studies were identified. The results showed that flavonoid supplementation could significantly increase the levels of antioxidative enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione-S-transferase), reduce the production of oxidative agents (malonaldehyde) and pro-inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, IL-1β, C-reactive protein, immunoglobulin G, nitric oxide, vascular endothelial growth factor, and myeloperoxidase), and alleviate cell apoptosis (manifested by decreases in the mRNA expression levels of pro-apoptotic factors, such as caspase-3, Fas cell surface death receptor, and Bax, and increases in the mRNA expression levels of Bcl2), DNA damage (reductions in tail length and tail DNA%), and nanomaterial-induced injuries of the liver (reduced alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase activities), kidney (reduced urea, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and uric acid concentration), testis (increased testosterone, sperm motility, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type, and reduced sperm abnormalities), and brain (enhanced acetylcholinesterase activities). Most of the results were not changed by subgroup analyses.

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that appropriate supplementation of flavonoids may be effective to prevent the occupational detriments resulting from nanomaterial exposure.

Introduction

The rapid advancement of nanotechnology has promoted the wide application of nanomaterials in many fields, such as the manufacturing industry, biomedicine, agriculture, water treatment, food additive, and cosmetics (1–5). The increased use makes nanomaterials unavoidably enter human bodies via various routes (including inhalation, skin absorption, ingestion, or injection) and then cause toxicities to different organs (e.g., lung, liver, kidney, brain, prostate, and testis) (6, 7). Therefore, it is urgently imperative to develop strategies to prevent and treat harmful effects of nanomaterials on human health.

Since pharmacological interventions are always prone to induce adverse side effects, nutrition modification has recently gained more attention as an important method for the prevention and treatment of diseases. Flavonoids that include six main subclasses [flavanones, flavones, flavonols, flavanols (monomer flavan-3-ols and polymer proanthocyanidins), anthocyanidins, and isoflavones] based on their molecular structures belong to a group of polyphenolic secondary metabolites in the plants (8, 9). Flavonoids can be ingested into the human diet by consuming fruits, vegetables, seeds, bark, roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and beverages (e.g., fruit juice, wine, beer, tea, coffee, and chocolate) (8, 9). Increasing evidence supports that flavonoid intake prevents the development and progression of diseases by exerting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (10–12). It is also well known that activations of oxidative stress and inflammation are crucial mechanisms associated with tissue injuries induced by nanomaterials (13, 14). Therefore, daily dietary supplementation of flavonoids may represent a potential approach for the prevention and treatment of nanomaterial-induced toxicities; this hypothesis had been demonstrated by numerous animal experiments (15–18). However, the negative effects of flavonoids were also reported in some preclinical animal studies: Ali et al. found that, compared with rats that only received nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiONPs), the levels of hepatic oxidant malonaldehyde (MDA), antioxidant glutathione (GSH), and renal superoxide dismutase (SOD) were not significantly changed in rats undergoing a combined administration of flavones (apigenin) for 7 days, which was accompanied by no effects on liver (aspartate aminotransferase, AST; alanine aminotransferase, ALT) and renal (creatinine, urea, and blood urea nitrogen) functional biomarkers (19). Shahin et al. observed that the co-administration of flavonols (morin) for 1 or 2 weeks could not significantly alleviate titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TIO2NPs)-induced lipid peroxidation (MDA) in the testicular tissues and sperm abnormalities (20). The study of Dora et al. showed that, compared with iron oxide nanoparticle (IONP)-exposed rats, the levels of GSH and serotonin were not significantly increased in the brain homogenates of rats that were orally supplemented with flavonols (quercetin) at the dosages of 25 and 50 mg/kg. The oral additional administration of flavonols (quercetin) was also proved not to significantly reduce the levels of serum cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) relative to the zinc oxide nanoparticle (ZnONP)-intoxicated group (21). Abdelkarem et al. even found that the level of pro-inflammatory mediator tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) was increased in the serum of the ZnONP-exposed rats after treatment with flavonols (quercetin) (22). Therefore, whether flavonoid supplementation exerts a protective role against nanomaterial-induced toxicities remains inconclusive.

In the present study, we performed a meta-analysis of all the available published preclinical studies to comprehensively explore the effects of flavonoid supplementation on oxidant stress-, inflammation-, and organ function-related indicators. Our study may provide a theoretical basis for clinical recommendation of flavonoid supplementation, especially for workers with occupational exposure to nanomaterials.

Materials and Methods

Literature Retrieval

This meta-analysis followed the guidelines of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA). Three databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library, were searched to compile relevant studies published up to April 2022. No limits were set on language. The search terms were designed by referring to the previous reports on flavonoids (23–25), including (“nanoparticle” OR “carbon nanotube” OR “graphene”) AND (“flavonoids” OR “flavonols” OR “flavanols” OR “flavan-3-ols” OR “flavanones” OR “flavones” OR “isoflavones” OR “isoflavanones” OR “anthocyanins” OR “proanthocyanidins” OR “anthocyanidin” OR “polyphenol” OR “cyanidin” OR “delphinidin” OR “malvidin” OR “pelargonidin” OR “catechins” OR “epicatechin” OR “epigallocatechin” OR “gallocatechin” OR “theaflavins” OR “thearubigins” OR “quercetin” OR “kaempferol” OR “myricetin” OR “myricitrin” OR “isorhamnetin” OR “galangin” OR “morin” OR “fisetin” OR “luteolin” OR “apigenin” OR “hesperetin” OR “naringenin” OR “naringin” OR “hesperidin” OR “isoflavonoid” OR “genistein” OR “daidzein” OR “baicalin” OR “silibinin” OR “taxifolin” OR “silymarin”) AND (animal). Additionally, the reference lists of the included studies and reviews were scanned to retrieve potential eligible studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) criteria were used to include the eligible studies: (1) participants (P): murine; (2) intervention (I): the experimental group was administrated with nanomaterials and any kind of flavonoids (the dosage of which should be clearly reported); (3) comparison (C): the control group was only given nanomaterials; (4) outcomes (O): oxidative stress-related (MDA, SOD, and GSH; glutathione peroxidase, GPx; catalase, CAT; glutathione-S-transferase, GST; glutathione reductase, GR; nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, Nrf2), inflammation-related (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β; C-reactive protein, CRP; immunoglobulin G, IgG; myeloperoxidase, MPO; nitric oxide, NO; vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF), global health issues-related (body weight), organ injury-related (liver function: AST and ALT; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; renal function: albumin, urea, creatinine, uric acid, blood urea nitrogen; testis function: sperm count, sperm motility, sperm abnormalities, live sperm, and testosterone; luteinizing hormone, LH; follicle-stimulating hormone, FSH; 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type, 17β-HSD; brain function: serotonin; acetylcholinesterase, AChE), apoptosis-related (TUNEL apoptotic index; mRNA expression levels of caspase-3; Fas cell surface death receptor, FAS; B-cell lymphoma-2, Bcl2; BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator, Bax), and DNA damage-related (tail length, tail DNA%) indicators; and (5) study design (S): controlled trials.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplicate articles; (2) non-original research, such as case reports, reviews, editorials, letters, comments, and expert opinion papers; (3) in vitro and non-murine in vivo experiments; (4) interventions with plant extracts in which flavonoids were included, but detailed concentrations and dosages were unclear; (5) data could not be obtained or combined with other publications; and (6) irrelevant to the study topic. Two authors independently screened the literature, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the following data from each eligible article: the first author, publication year, country of origin, animal species, sample size, type/dose of nanomaterials, type/dose/administration route/intervention duration of flavonoids, sample source for the analysis of outcomes, and data of outcomes of interest (mean ± standard deviation). The data presented in the bar graphs were estimated by using the digitizing software Engauge Digitizer 4.11. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Quality Assessment

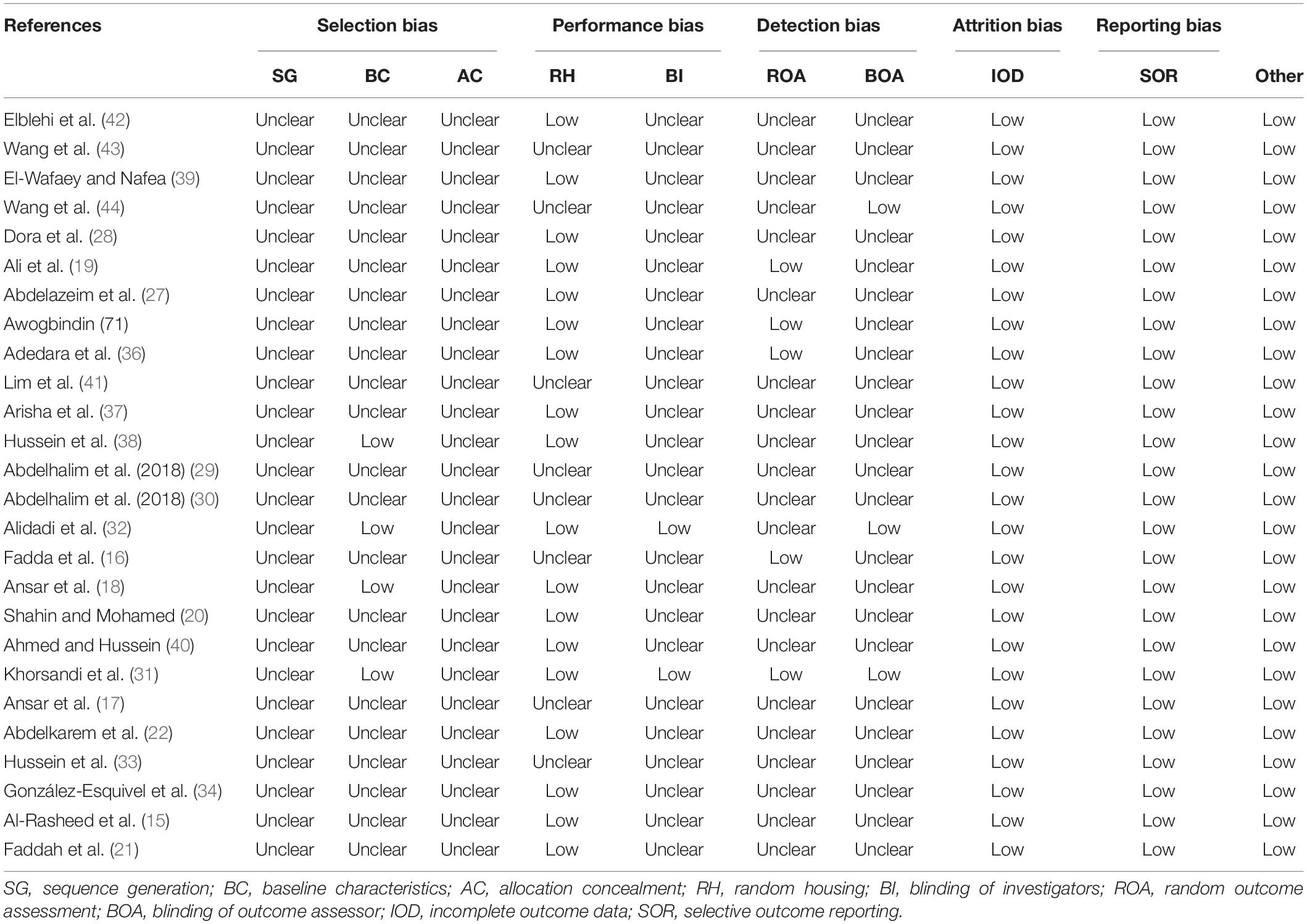

SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool was used to assess the quality of the included animal intervention studies (26). This tool consisted of 10 questions to reflect the source of bias from selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other aspects. The risk of bias was ranked as low, unclear, or high in each item when it was labeled as yes, no, or unknown to selected articles. The methodological quality was independently evaluated by two authors. Reviewers resolved discrepancies through discussion with a third reviewer.

Statistical Analysis

STATA 15.0 software (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. The effect size for all outcomes was expressed as standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The heterogeneity between studies was assessed by using the Cochrane’s Q-square test and I2 statistic. A fixed-effects model was chosen to calculate the pooled results if obvious heterogeneity was present (p < 0.1 and I2 > 50%); otherwise, a random-effects model was selected. To explore the potential sources of between-study heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were performed based on nanomaterial types, subclasses, dosages, intervention durations, administration routes of flavonoids, sample sources, and animal species. Egger’s linear regression test was employed to investigate the publication bias. A trim-and-fill method was used to correct the pooled results in the presence of the publication bias (p < 0.05). The stability of the meta-analysis results was assessed by using a sensitivity analysis, which was based on the removal of one study at a time.

Results

Study Selection

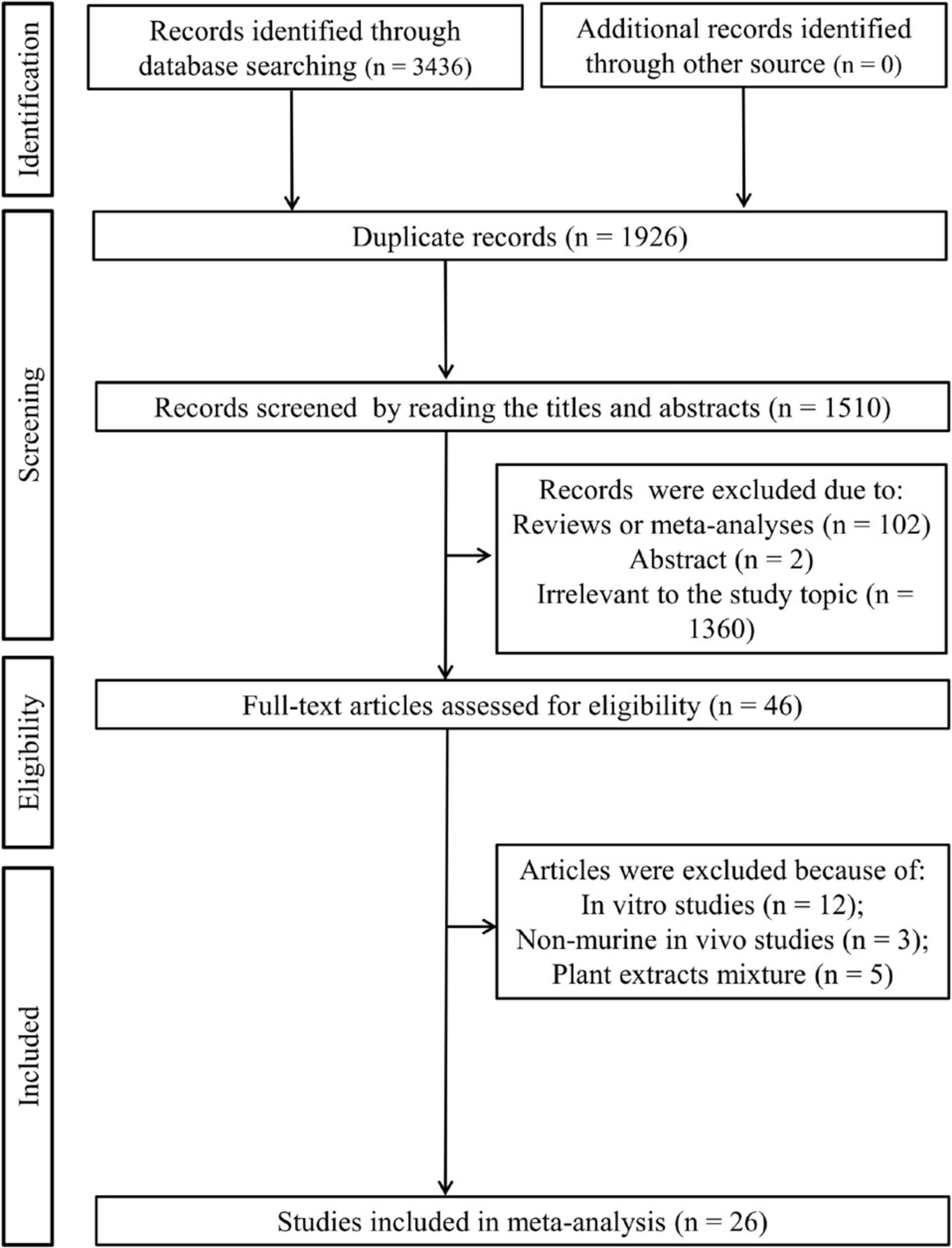

As shown in Figure 1, 3,436 articles were initially retrieved after a literature search in three electronic databases, of which 1,926 were duplicates. By browsing the titles and abstracts, 1,464 were excluded since 102 of them were reviews or meta-analyses, two of them were abstracts, and 1,360 studies were irrelevant to the study topic. The full text of the remaining 46 studies was downloaded and reviewed, after which 20 studies were removed because of the following reasons: in vitro studies (n = 12); non-murine in vivo experiments (n = 3); and plant extract mixture (n = 5). Finally, 26 studies were included in this meta-analysis (15–22, 27–44).

Study Characteristics

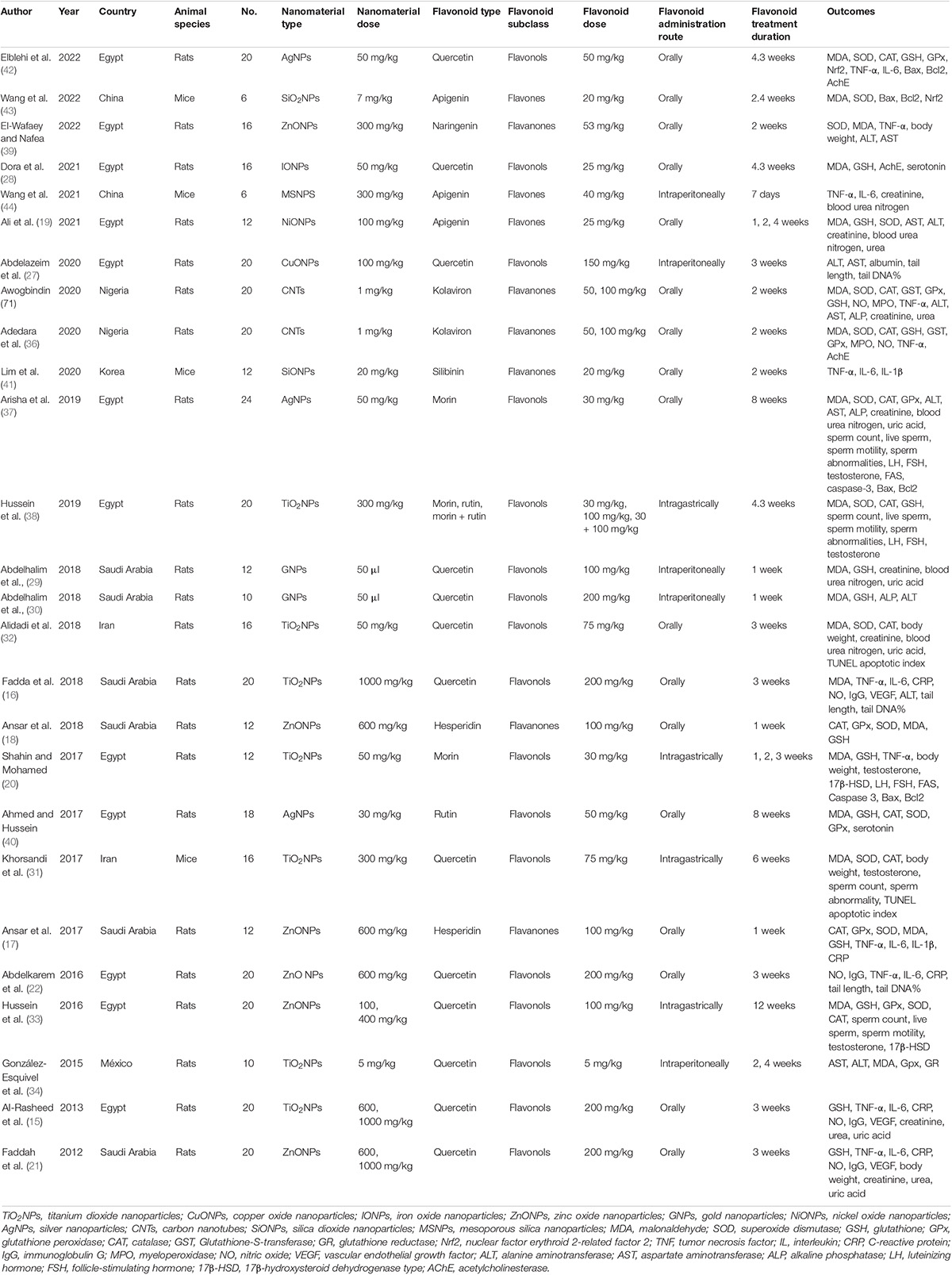

The basic characteristics of the included articles are presented in Table 1. These 26 studies were published between 2012 and 2022. They were conducted in seven countries, including 12 in Egypt; six in Saudi Arabia; two in Iran, Nigeria, and China; and one in Korea and México. Twenty-two preclinical studies were carried out in rats, and the other four were conducted in mice. Three flavonoid subclasses were assessed in these studies, including flavonols (quercetin, n = 13; rutin, n = 2; morin, n = 3), flavanones (naringenin, n = 1; kolaviron, n = 2; hesperidin, n = 2; silibinin, n = 1), and flavones (apigenin, n = 3). The dosage of quercetin ranged from 5 to 200 mg/kg daily; two supplementation dosages were designed for rutin and kolaviron (50 and 100 mg/kg); three were designed for apigenin (20, 25, and 40 mg/kg); and only one dosage regimen was set for other flavonoid types (morin, 100 mg/kg; naringenin, 53 mg/kg; hesperidin, 100 mg/kg; silibinin, 20 mg/kg). Supplementation with flavonoids was used to protect the injuries induced by TiO2NPs (n = 7), ZnONPs (n = 6), silver nanoparticles (AgNPs, n = 3), carbon nanotubes (CNTs, n = 2), copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs, n = 1), gold nanoparticles (GNPs, n = 1), IONPs (n = 1), NiONPs (n = 1), silica dioxide nanoparticles (SiONPs, n = 2), and mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs, n = 1). Flavonoids were administered orally (n = 17), intraperitoneally (n = 5), or intragastrically (n = 4). The duration of intervention ranged from 1 to 12 weeks. The risk of bias was unclear or low for domains of all studies, indicating that the quality of included studies was acceptable (Table 2).

Meta-Analysis

Since multiple dosages, intervention durations, and tissue samples were collected for some studies, the number of datasets in our meta-analysis was larger than the actual number of included studies. The detailed data that were extracted for each variable are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

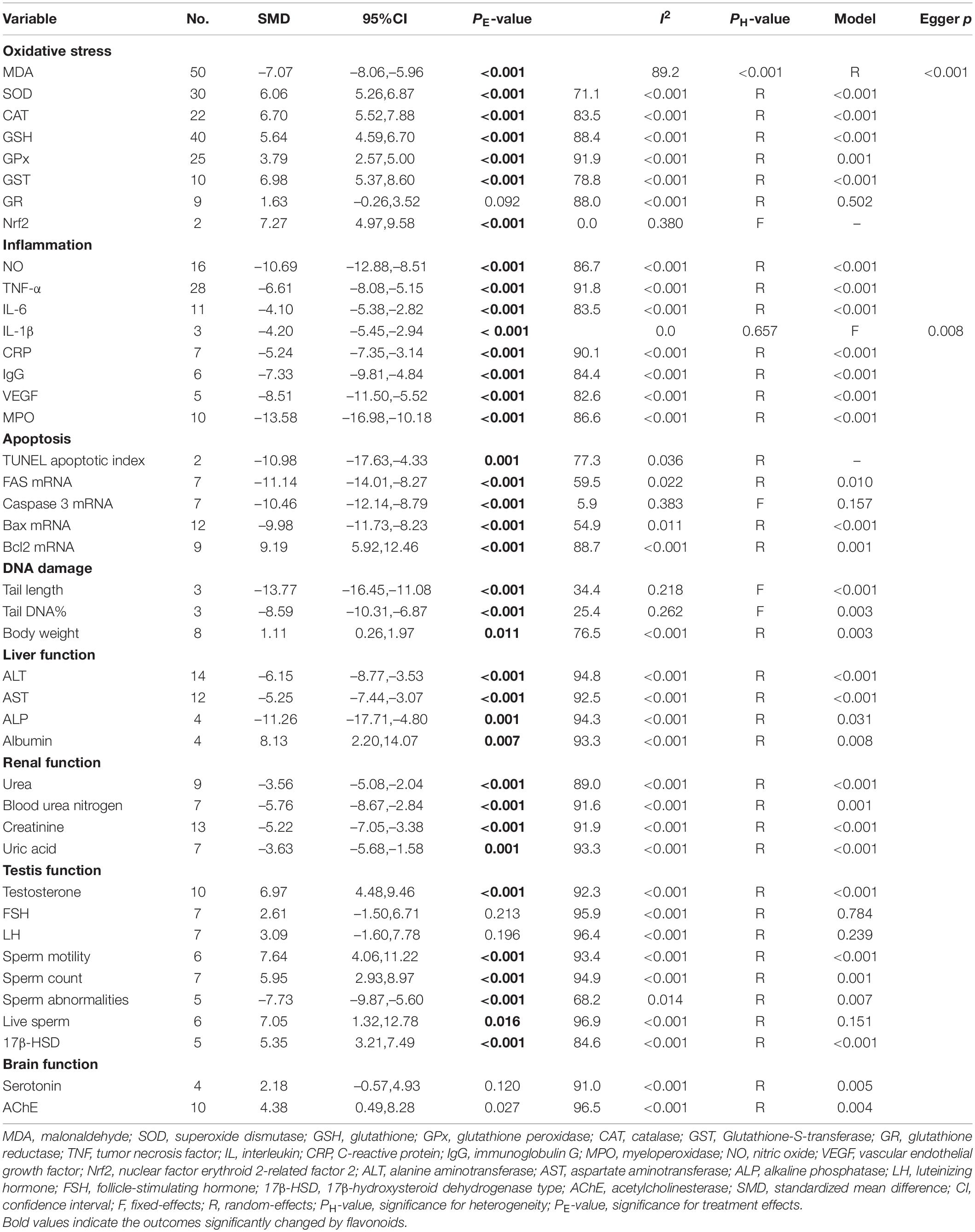

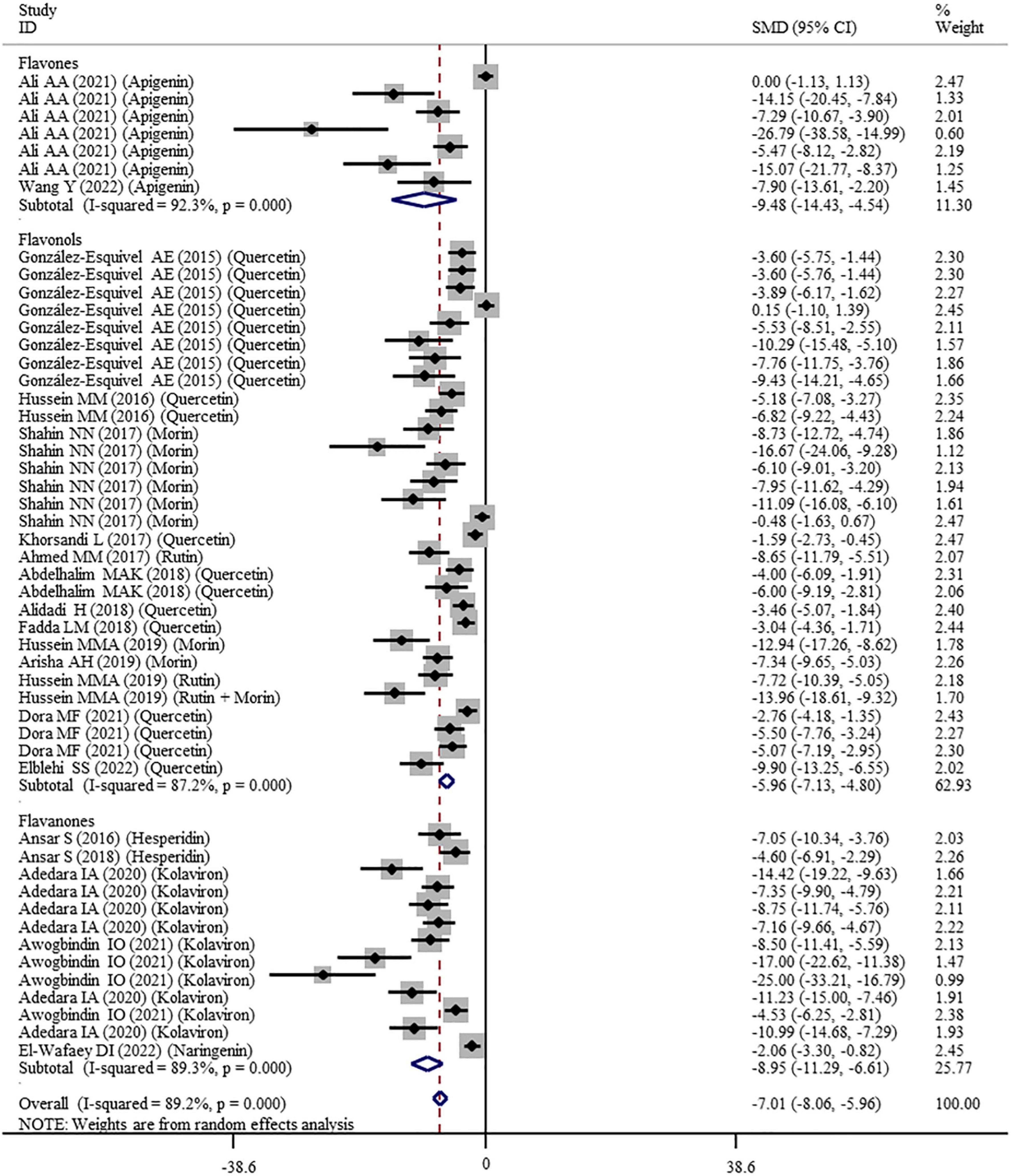

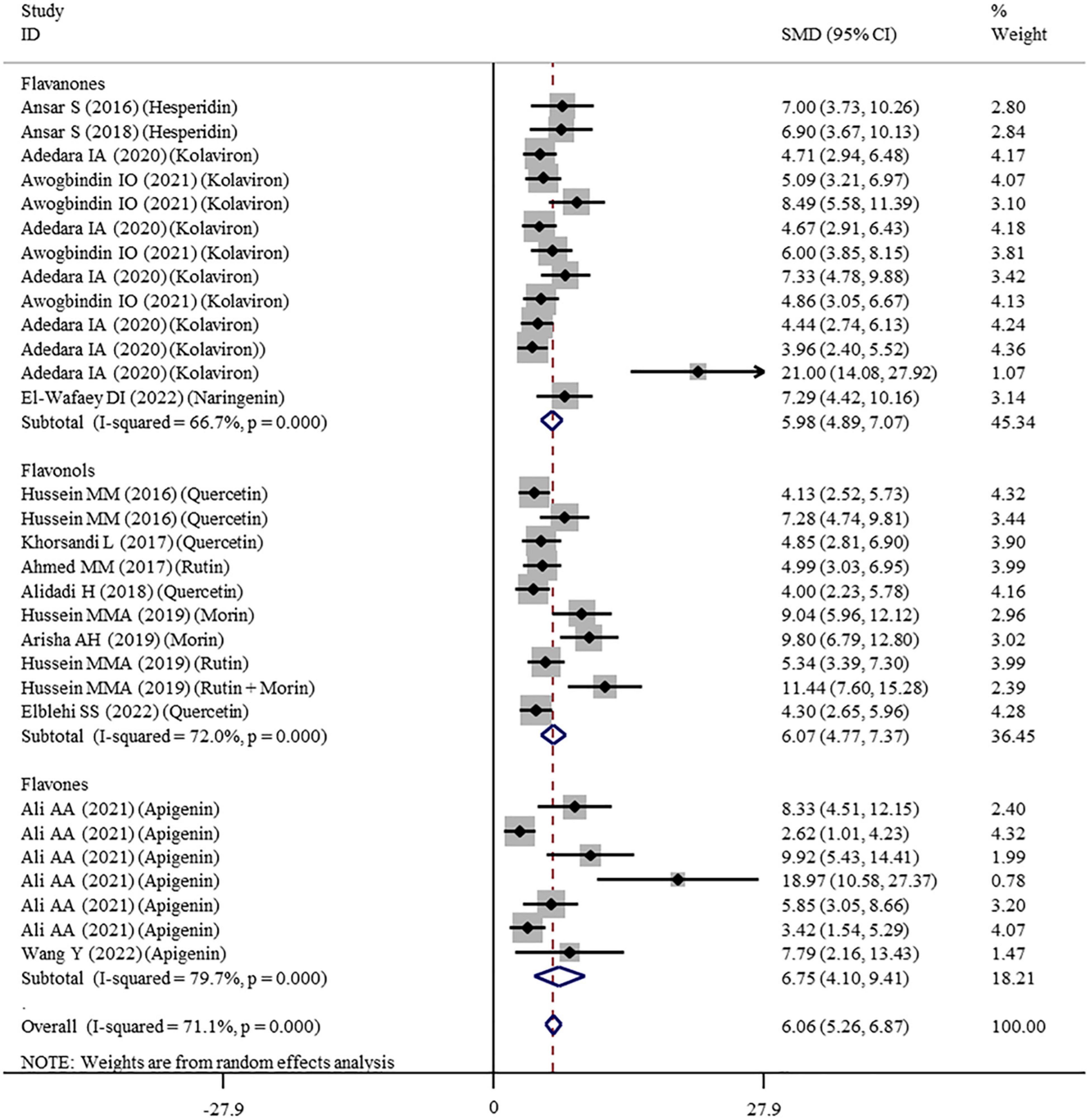

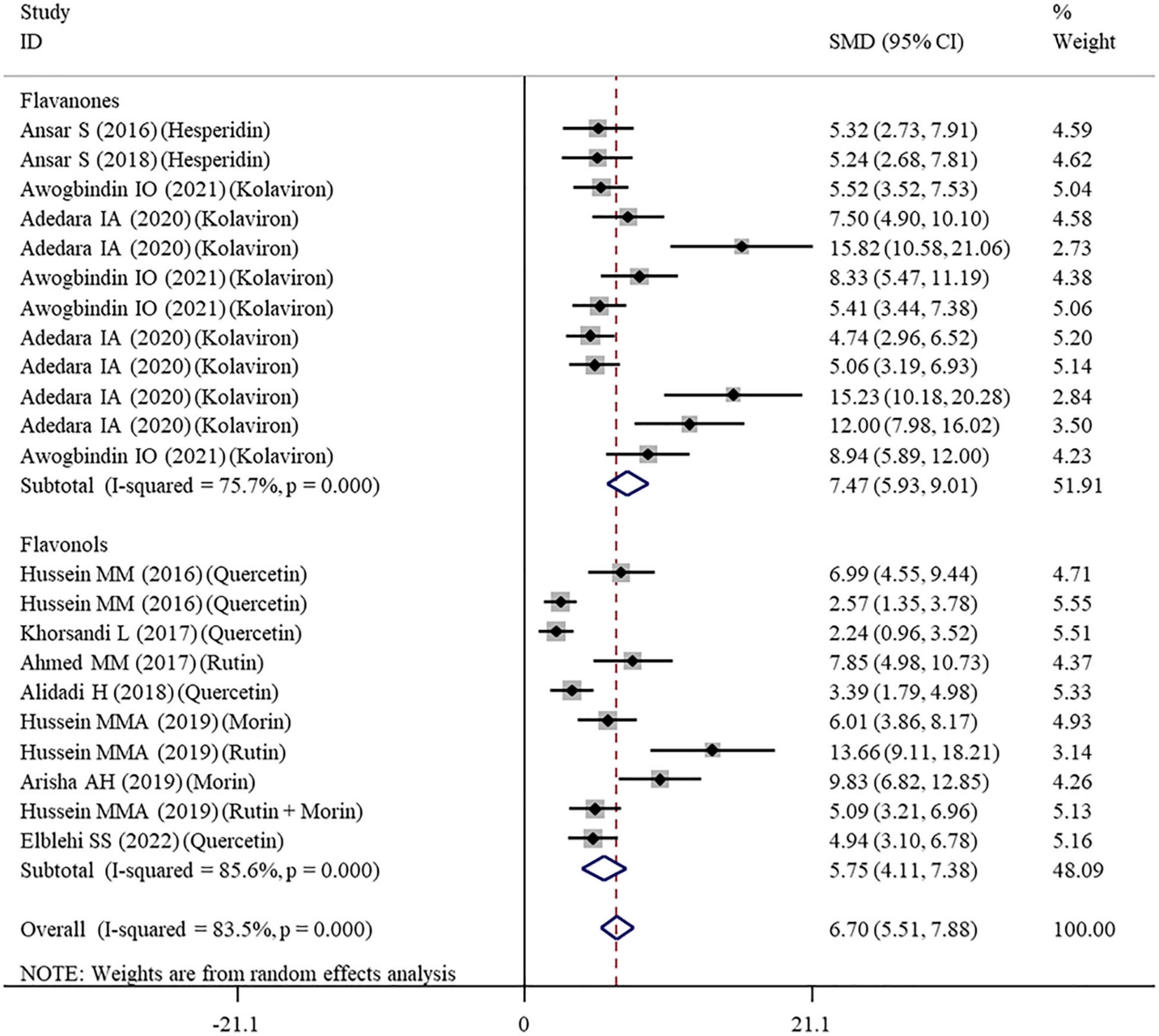

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Oxidative Stress

The effects of flavonoid supplementation on MDA, SOD, CAT, GSH, GPx, GST, GR, and Nrf2 were reported in 50, 30, 22, 40, 25, 10, 9, and 2 datasets, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The overall meta-analysis results showed that, compared with the nanomaterial-exposed group, nutritional interventions with flavonoids could significantly reduce the levels of pro-oxidant MDA (SMD = − 7.07; 95%CI, −8.06 to −5.96; p < 0.001; Figure 2) but increase the levels of antioxidant SOD (SMD = 6.06; 95%CI, 5.26 – 6.87; p < 0.001; Figure 3), CAT (SMD = 6.70; 95%CI, 5.52 – 7.88; p < 0.001; Figure 4), GSH (SMD = 5.64; 95%CI, 4.59 – 6.70; p < 0.001), GPx (SMD = 3.79; 95%CI, 2.57 – 5.00; p < 0.001), GST (SMD = 6.98; 95%CI, 5.37 – 8.60; p < 0.001), and Nrf2 (SMD = 7.27; 95%CI, 4.97 – 9.58; p < 0.001) (Table 3). The level of GR was not significantly different between two groups (p = 0.092) (Table 3).

Figure 2. Forest plots to show the effects of flavonoid supplementation on MDA levels compared with the nanomaterial exposure group. MDA, malonaldehyde; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3. Forest plots to show the effects of flavonoid supplementation on SOD levels compared with the nanomaterial exposure group. SOD, superoxide dismutase; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4. Forest plots to show the effects of flavonoid supplementation on CAT levels compared with the nanomaterial exposure group. CAT, catalase; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

As shown in Table 3, a random-effects model was selected for the meta-analyses because there was evidence of heterogeneity in the analysis of all oxidative stress-related indicators. Therefore, subgroup analyses were performed for them. The pooled results showed that the significant beneficial effects of flavonoid supplementation on MDA (Figure 2), SOD (Figure 3), and CAT (Figure 4) were still found in all subgroups regardless of nanomaterial types, subclasses, dosages, intervention durations, administration routes of flavonoids, sample sources, and animal species (Supplementary Table 2). Although supplementation with all three flavonoid subclasses at various dosages and durations was found to reverse the decrease in GSH induced by nanomaterials (except for GNPs), the beneficial effects for brain, liver, kidney, and prostate tissues (except of testis) were mainly exerted by oral or intragastrical administration of quercetin, rutin, kolaviron, and apigenin but not morin (p = 0.377) and hesperidin (p = 0.176) (Supplementary Table 2). The significant effects on GPx of brain, liver, and testis tissues (not kidney) were only found in the subgroups with oral or intragastrical supplementation of flavanone (not flavonols) and flavonoid interventions for more than 2 weeks (Supplementary Table 2). Flavanone (kolaviron) supplementation was shown to significantly increase the levels of GST in brain, liver, and kidney tissues regardless of the used dosages (Supplementary Table 2). Flavanone (hesperidin) supplementation was found to increase the level of GR (SMD = 3.68; 95%CI, 1.71 – 5.65; p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2), but only one study reported this result, and thus, further confirmation was still needed.

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Inflammation

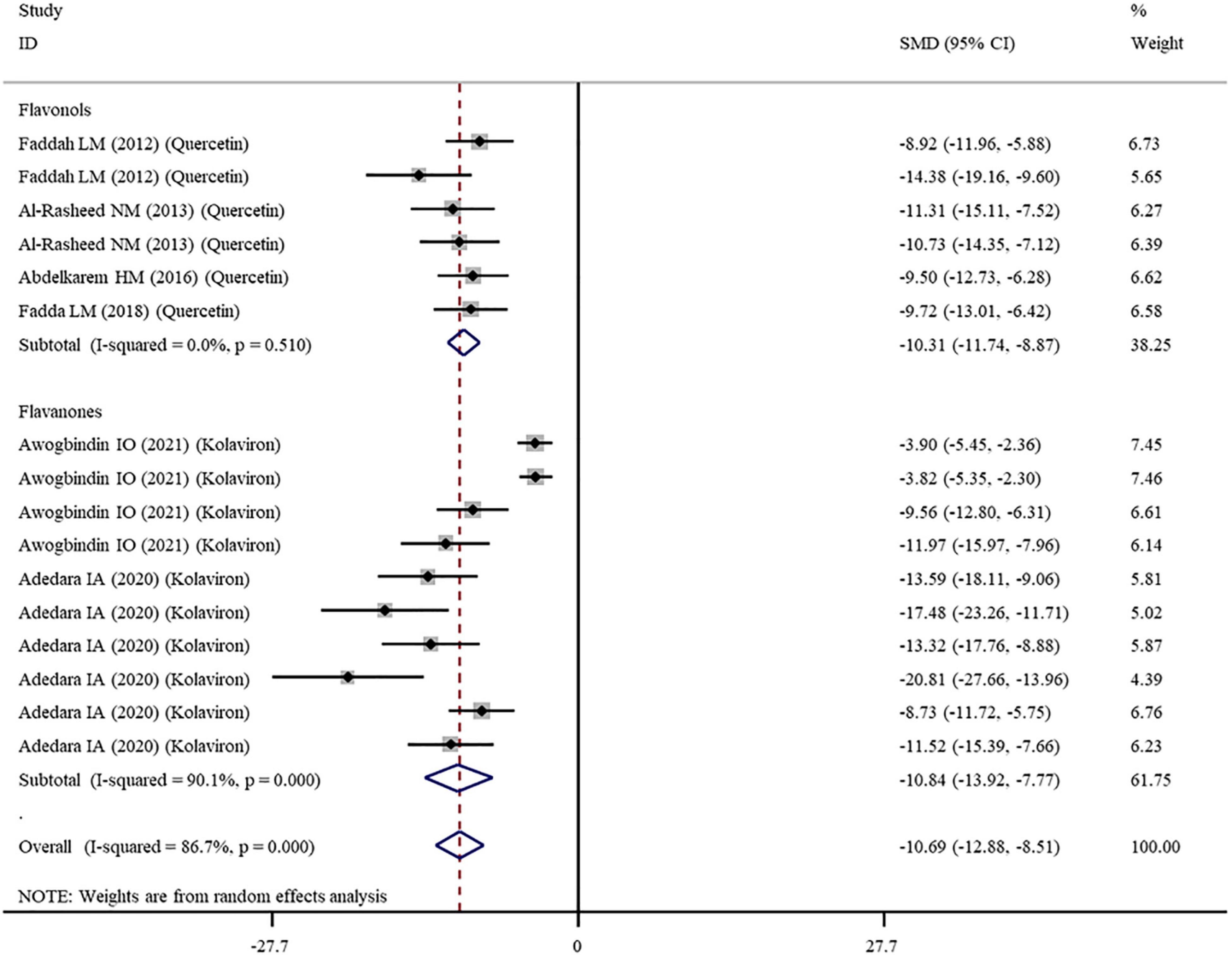

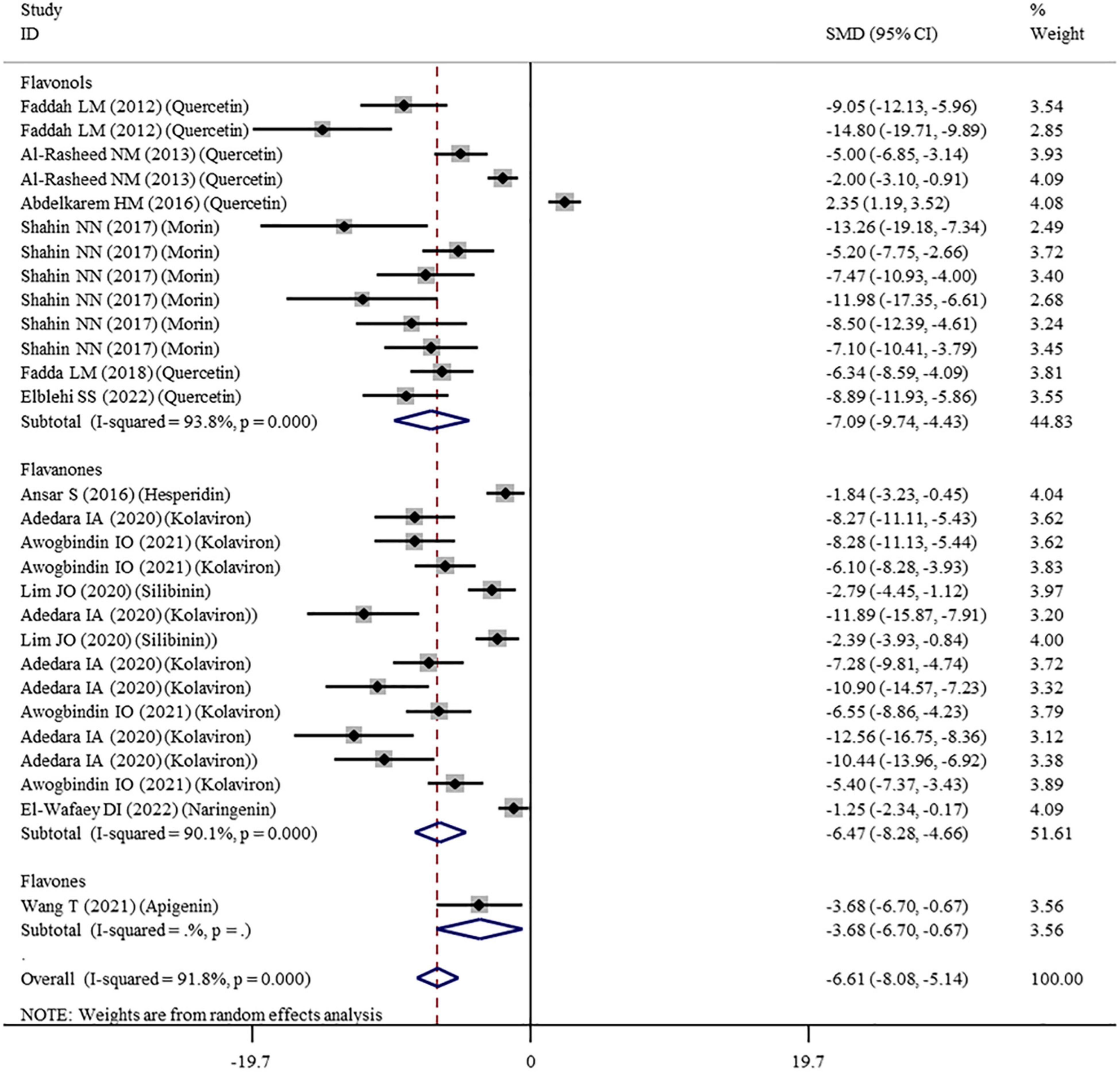

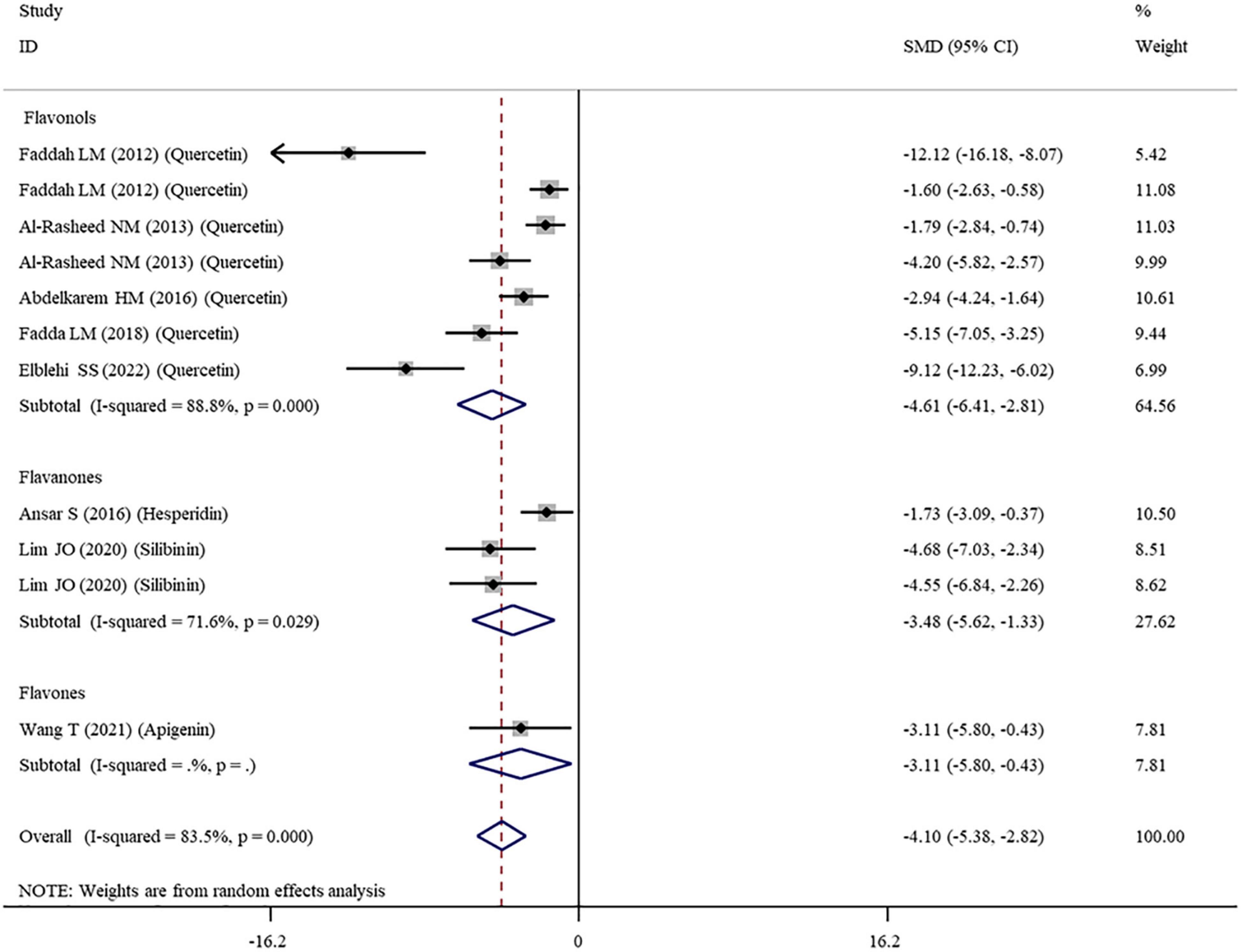

The levels of NO, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, CRP, IgG, VEGF, and MPO were measured in 16, 28, 11, 3, 7, 6, 5, and 10 datasets, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The overall meta-analysis results indicated that co-administration of flavonoids to animals intoxicated with nanomaterials significantly ameliorated the elevation in the levels of pro-inflammatory NO (SMD = − 10.69; 95%CI, − 12.88 to − 8.51; p < 0.001; Figure 5), TNF-α (SMD = − 6.61; 95%CI, −8.08 to −5.15; p < 0.001; Figure 6), IL-6 (SMD = − 4.10; 95%CI, −5.38 to − 2.82; p < 0.001; Figure 7), IL-1β (SMD = −4.20; 95%CI, −5.45 to −2.94; p < 0.001), CRP (SMD = −5.24; 95%CI, −7.35 to − 3.14; p < 0.001), IgG (SMD = − 7.33; 95%CI, −9.81 to −4.84; p < 0.001), VEGF (SMD = −8.51; 95%CI, −11.50 to −5.52; p < 0.001), and MPO (SMD = − 13.58; 95%CI, −16.98 to −10.18; p < 0.001) compared with their levels in nanomaterial-treated animals (Table 3).

Figure 5. Forest plots to show the effects of flavonoid supplementation on NO levels compared with the nanomaterial exposure group. NO, nitric oxide; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 6. Forest plots to show the effects of flavonoid supplementation on TNF-α levels compared with the nanomaterial exposure group. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 7. Forest plots to show the effects of flavonoid supplementation on IL-6 levels compared with the nanomaterial exposure group. IL, interleukin; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Except for IL-1β which was analyzed with a fixed-effects model, other outcomes were analyzed with a random-effects model because of the presence of significant heterogeneity. Thus, subgroup analyses were performed for them. The pooled results showed that, compared with controls, all these pro-inflammatory mediators were still significantly reduced after the administration of flavonoids regardless of which subgroups they belonged to (Supplementary Table 3 and Figures 5–7).

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Apoptosis

TUNEL apoptotic index and the mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-related genes (FAS, caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl2) were measured in 2, 7, 7, 12, and 9 datasets, respectively. The pooled analysis of these indicators showed that flavonoid (morin or morin + rutin) supplementation decreased the TUNEL apoptotic index (SMD = − 10.98; 95%CI, −17.63 to –4.33; p = 0.001), downregulated the mRNA expression levels of pro-apoptotic factors, such as FAS (SMD = −11.14; 95%CI, −14.01 to −8.27; p < 0.001), caspase-3 (SMD = − 10.46; 95%CI, −12.14 to −8.79; p < 0.001), and Bax (SMD = − 9.98; 95%CI, −11.73 to −8.23; p < 0.001), and upregulated the mRNA expression level of anti-apoptotic Bcl2 (SMD = 9.19; 95%CI, 5.92 – 12.46; p < 0.001) compared with the nanomaterial-exposed groups (Table 3). These results of FAS, caspase-3, and Bax indicators were not changed by subgroup factors. The mRNA expression level of Bcl2 seemed to be only significantly increased by quercetin and morin but not by apigenin (Supplementary Table 4).

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on DNA Damage

Comet assay was performed to evaluate the DNA damage in two studies with three datasets, after which the data about tail DNA content and tail length were obtained. The pooled analysis of these data found that flavonoid (quercetin) supplementation led to significant decreases in the tail length (SMD = −13.77; 95%CI, −16.45 to −11.08; p < 0.001) and the tail DNA% (SMD = −8.59; 95%CI, −10.31 to −6.87; p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Body Weight

Eight datasets recorded the body weight of the animals treated with nanomaterials alone or co-administered with flavonoids (Supplementary Table 1). The meta-analysis of these eight datasets under a random-effects model revealed that, relative to nanomaterial-intoxicated animals, flavonoid supplementation significantly increased the body weight of the animals (SMD = 1.11; 95%CI, 0.26–1.97; p = 0.011) (Table 3). The subgroup analysis indicated that only morin (p = 0.019) and naringenin (p = 0.008; this conclusion needed further confirmation because only one study was included) were effective interventions for improving the body weight of animals, but not quercetin (p = 0.397). Also, the improvement effect on the body weight was only limited to the subgroups with TiO2NP exposure, with flavonoid supplementation for less than 2 weeks and with an intervention dosage of ≤ 100 mg/kg (Supplementary Table 5).

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Liver Function

Alanine aminotransferase, AST, ALP, and albumin were determined in our included studies (involving 14, 12, 4, and 4 datasets, respectively) to explore whether flavonoid supplementation could protect against nanomaterial-induced liver injuries (Supplementary Table 1). As shown in Table 3, the levels of ALT (SMD = − 6.15; 95%CI, −8.77 to −3.53; p < 0.001), AST (SMD = −5.25; 95%CI, −7.44 to −3.07; p < 0.001), and ALP (SMD = −11.26; 95%CI, −17.71 to −4.80; p = 0.001) were found to be significantly decreased; the level of albumin (SMD = 8.13; 95%CI, 2.20 – 14.07; p = 0.007) was significantly increased in the animals that received flavonoids in addition to nanomaterials.

Subgroup analyses demonstrated that the effects on ALT, AST, and albumin were particularly significant in the subgroups treated with flavonol and flavanone subclasses at a high dosage (>100 mg/kg) or a low dosage (≤50 mg/kg) and undergoing flavonoid treatment for more than 2 weeks. The level of ALP seemed not to be significantly improved in the subgroups stratified by flavonoid subclasses (Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, flavonoid supplementation prevented ZnONP-, AgNP-, CuONP-, CNT-, and TiO2NP-induced increases in the levels of ALT and/or AST and a NiONP-induced increase in the level of albumin (Supplementary Table 6).

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Renal Function

Renal function biomarkers (urea, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and uric acid) were, respectively, detected in 9, 7, 13, and 7 datasets (Supplementary Table 1). The combined results from a random-effects model indicated that supplementation with flavonoids to the nanomaterial-exposed animals resulted in significant decreases in the levels of urea (SMD = −3.56; 95%CI, −5.08 to −2.04; p < 0.001), blood urea nitrogen (SMD = − 5.76; 95%CI, −8.67 to −2.84; p < 0.001), creatinine (SMD = −5.22; 95%CI, −7.05 to −3.38; p < 0.001), and uric acid (SMD = − 3.63; 95%CI, − 5.68 to −1.58; p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Subgroup analyses demonstrated that supplementation with all these three flavonoid subclasses (without dosage requisition) provided statistically significant effects on four renal function biomarkers, especially when the interventions were performed for more than 2 weeks. Additionally, flavonoid supplementation only prevented TiO2NP- and AgNP-induced increases in the level of uric acid; the beneficial effects of flavonoids on the levels of urea and blood urea nitrogen were applicable to all studied nanomaterials; MSNP-induced creatinine was not significantly improved by flavonoids (Supplementary Table 7).

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Testis Function

Sex hormones (testosterone, FSH, and LH), semen profile (sperm motility, sperm cell count, sperm abnormalities, and live sperm), and steroidogenesis pathway gene (17β-HSD) were reported in 10, 7, 7, 6, 7, 5, 6, and 5 datasets, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, we found that the intake of flavonoids could trigger marked increases in the serum testosterone level (SMD = 6.97; 95%CI, 4.48 – 9.46; p < 0.001), sperm motility (SMD = 7.64; 95%CI, 4.06 – 11.22; p < 0.001), cell count (SMD = 5.95; 95%CI, 2.93 – 8.97; p < 0.001), live percentage (SMD = 7.05; 95%CI, 1.32 – 12.78; p = 0.016), and 17β-HSD expression levels (SMD = 5.35; 95%CI, 3.21 – 7.49; p < 0.001) but induce a decrease in the percentage of abnormal sperms (SMD = − 7.73; 95%CI, −9.87 to −5.60; p < 0.001) compared with the nanomaterial-exposed group (Table 3). The FSH and LH levels were not significantly changed by flavonoids.

Only the flavonol subclass was investigated in the included studies; thus, the overall meta-analysis results of flavonoid supplementation represented the effects of flavonols on the testis function. Quercetin, rutin, and morin were all shown to significantly improve the testosterone levels, the percentage of abnormal sperms, and the expression levels of 17β-HSD; sperm motility, count, and the percentage of live sperm seemed to be only enhanced by rutin and morin but not by quercetin (Supplementary Table 8). Flavonoid dosage, intervention duration, and route factors did not influence the meta-analysis results (except for live sperm which was only significantly increased when flavonoids were given at a dosage of > 100 mg/kg). Although supplementation with rutin and rutin + morin was shown to increase the FSH and LH levels in the subgroup analyses, there was only one study to demonstrate this conclusion (Supplementary Table 8), and thus, further confirmation was still needed.

Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Brain Function

Serotonin and AchE were two biomarkers to reflect the nanomaterial-induced neurotoxicity in the brain and the effects of flavonoid supplementation. They were reported in four and ten datasets, respectively. The overall meta-analysis results showed that dietary supplementation with flavonoids was not significantly associated with alterations in the serotonin level (p = 0.120). The AChE activity was significantly enhanced by flavonoids (p = 0.027) (Table 3), and this significance was amplified in the flavanone (kolaviron) subgroup (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 9).

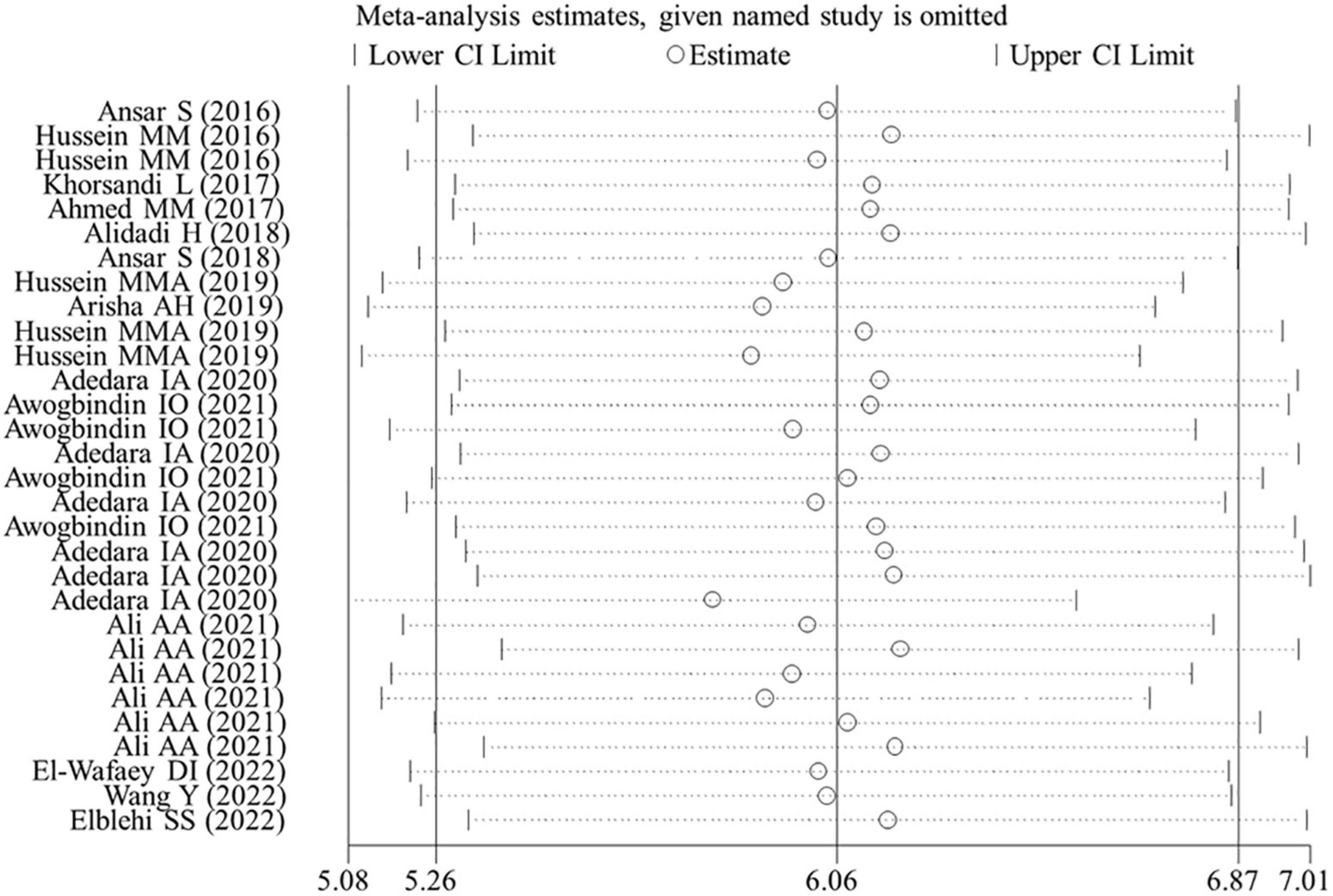

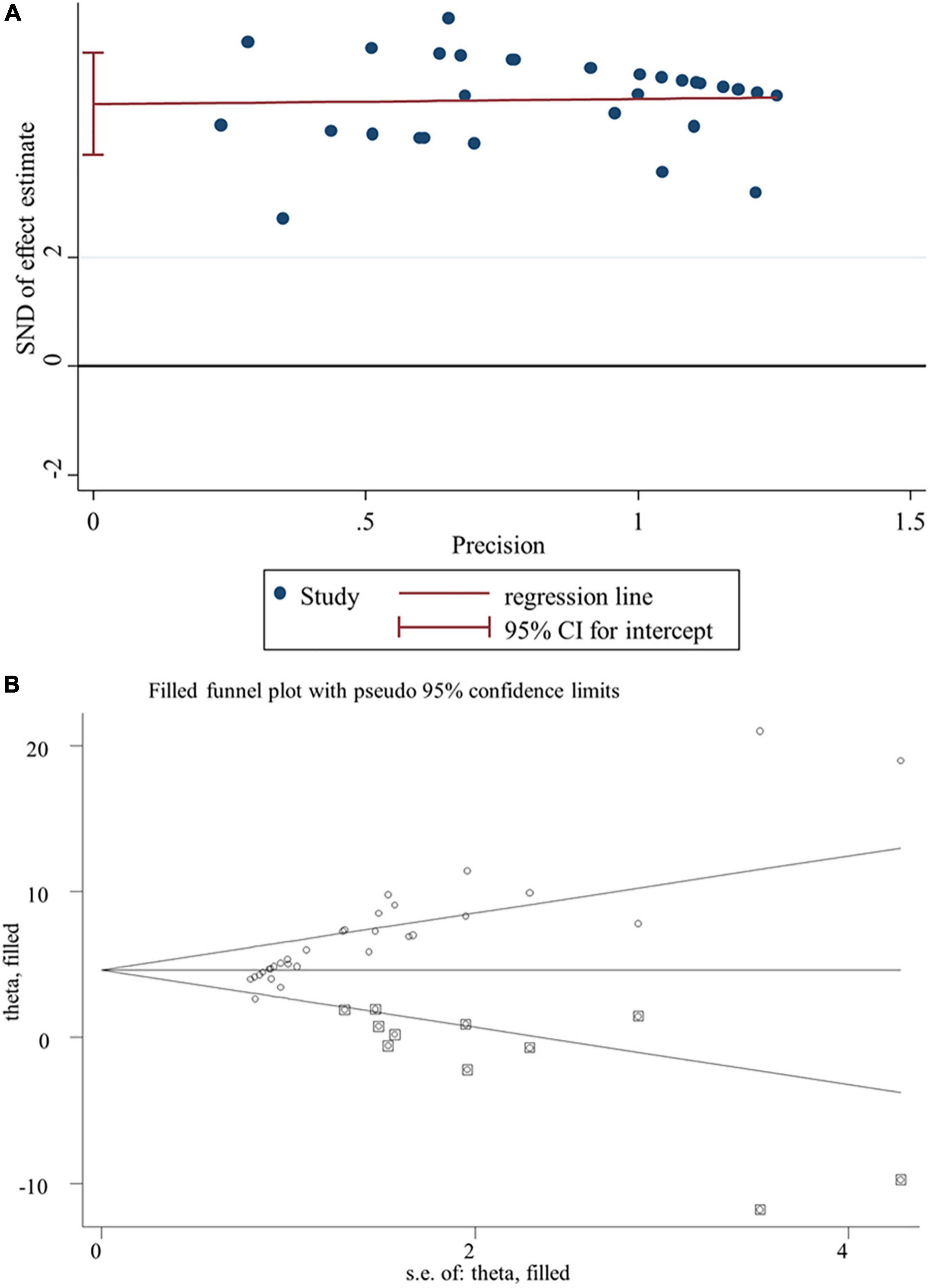

Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

Egger’s linear regression test revealed the presence of the publication bias for the analysis of several indicators (except of GR, p = 0.502; FSH, p = 0.784; LH, p = 0.239; live sperm, p = 0.151; caspase-3, p = 0.157) (Table 3). Thus, a trim-and-fill method was applied to adjust the effects of the publication bias for these indicators. As a result, beneficial effects of flavonoid supplementation on MDA, NO, TNF-a, IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, IgG, VEGF, MPO, ALT, ALP, AST, urea, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, uric acid, FAS, Bax mRNA, sperm abnormalities, tail length, and tail DNA% were found not to be altered after correction; significant results were still obtained for SOD (SMD = 4.77; 95%CI, 3.86 – 5.67; p < 0.001; Figure 8), CAT (SMD = 4.41; 95%CI, 3.20 – 5.76; p < 0.001), GSH (SMD = 3.66; 95%CI, 2.53 – 4.79; p < 0.001), GPx (SMD = 1.91; 95%CI, 0.64 – 3.19; p < 0.001), GST (SMD = 5.23; 95%CI, 3.53 – 6.94; p < 0.001), Bcl2 (SMD = 4.07; 95%CI, 0.77 – 7.37; p = 0.016), testosterone (SMD = 2.88; 95%CI, 0.26 – 5.49; p = 0.031), sperm motility (SMD = 3.60; 95%CI, 0.17 – 7.03; p = 0.04), and 17β-HSD (SMD = 3.58; 95%CI, 1.28 – 5.87; p = 0.002); the results of the body weight (SMD = 1.93; 95%CI, 0.77 – 4.86; p = 0.160), albumin (SMD = −15.51; 95%CI, −2.85 to 8.34; p = 0.337), sperm count (SMD = 2.09; 95%CI, −0.96 to 5.14; p = 0.180), live sperm (SMD = 0.83; 95%CI, −4.51 to 6.16; p = 0.304), and AChE (SMD = −0.55; 95%CI, −4.42 to 3.31; p = 0.780) were no longer significant after correction. The sensitivity analysis results also showed that the exclusion of any single study did not affect the synthesized results (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Publication bias analysis for SOD. (A) Egger’s publication bias plot; (B) the trim-and-fill analysis to adjust estimates. SND, standard normal deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the effects of flavonoid supplementation on nanomaterial-induced toxicities and potential mechanisms. Our meta-analysis of data from 26 preclinical animal studies showed that flavonoid supplementation could significantly increase the levels of anti-oxidative enzymes (SOD, CAT, GSH, GPx, and GST), reduce the production of oxidative agents (MDA) and pro-inflammatory mediators (NO, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, CRP, IgG, VEGF, and MPO), and alleviate cell apoptosis (manifested by decreases in the mRNA expression levels of pro-apoptotic factors, such as caspase-3, FAS, and Bax, and increases in the mRNA expression levels of Bcl2), DNA damage (reductions in tail length and tail DNA%), and nanomaterial-induced injuries of the liver (reduced ALT and AST activities), kidney (reduced urea, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and uric acid concentration), testis (increased testosterone, sperm motility, 17β-HSD, and reduced sperm abnormalities), and brain (enhanced AChE activities). Our conclusions were in line with previous meta-analyses that reported the protective roles of flavonoids on other oxidative stress- and inflammation-related diseases (11, 45). These findings suggest that appropriate supplementation of flavonoids may be a potential measure to prevent occupational detriments resulting from nanomaterial exposure.

Eight flavonoid types belonging to three subclasses [flavonols (quercetin, rutin, and morin), flavanones (naringenin, kolaviron, hesperidin, and silibinin), and flavones (apigenin)] were contained in our included studies. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, all these flavonoids possess phenolic hydroxyl groups structurally. Thus, they can scavenge free radicals directly by donating hydrogen or electron (46) and then inhibit lipid peroxidation to prevent the formation of the end products of lipid peroxidation (MDA) (47). This conclusion was confirmed in our subgroup analyses (i.e., the level of MDA induced by nanomaterials was significantly reduced by flavonoids regardless of flavonoid types, durations, and dosages). Furthermore, flavonoids [e.g., grape seed procyanidin extract (48), apigenin (43), and quercetin (42)] were reported to enhance the expression level of Nrf2, which could subsequently bind with the antioxidant response element to stimulate the transcription of antioxidant enzymes. In accordance with this theory, we found that the levels of SOD, CAT, GSH, GPx, and GST were significantly increased (accompanied by upregulation of Nrf2) after supplementation with overall flavonoids in nanomaterial-intoxicated animals. However, interestingly, subgroup analyses showed that the levels of SOD and CAT changed by various nanomaterials could be influenced by all flavonoid types; morin and hesperidin had no effects on the level of GSH; quercetin did not significantly induce the increase in the level of GPx. These results may be explained by the following reasons: (1) the sample size (especially hesperidin with only two data analyzed) was small, which may cause deviation in the results; (2) SOD and CAT are the first-line enzymes of cellular defense against oxidative injuries, and they can be rapidly induced to decompose O2 and H2O2 to prevent the formation of more reactive hydroxyl radicals (49); and (3) oral quercetin supplementation was found to be superior to intraperitoneal administration (the main route for studies with GPx analyzed, as given in Supplementary Table 1) in the protection against the oxidative stress (50).

There was evidence that nanomaterials caused an inflammatory response (increases in the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) by triggering the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which then activated mitogen-activated protein kinase–nuclear factor kappa B/activator protein-1 pathways (41, 51–53). Thus, blocking the production of ROS may be a potential reason to explain the anti-inflammatory roles of flavonoid supplementation, which was demonstrated by the study of Lim et al. (41). ChIP-seq analysis identified that Nrf2 directly bound to the upstream regions of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes (IL-6 and IL-1) to inhibit their expressions in M1-type macrophages, which was independent of the redox conditions (54). Therefore, upregulation of Nrf2 expression may be another potential mechanism of flavonoids to alleviate nanomaterial-induced inflammation as demonstrated by Elblehi et al. (42). Moreover, epigenetic regulation was considered to be important for nanomaterial-mediated toxicities (55). Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase, was found to suppress the transcription of high-mobility group box 1 by direct deacetylation regulation (56, 57), which then inhibited cells to release pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, and IgG) by binding to toll-like receptor 4 (57–59). Hereby, the activation of SIRT1 signaling pathways also could protect against nanomaterial-induced inflammation (60). In line with these studies, we found that the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, CRP, and IgG were significantly reduced by flavonoids compared with the nanomaterial-exposed group, and these results were not influenced by subgroup factors.

It had been widely accepted that ROS accumulation induced DNA damage (61) and activated mitochondria-dependent apoptotic signaling pathways (including increasing the expression levels of caspase-3 and Bax and decreasing the expression levels of Bcl2) (62). The addition of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β was demonstrated to increase the Fas expression and Fas-mediated caspase activation and apoptosis (63, 64). Theoretically, the alleviation of oxidative stress and inflammation by flavonoids may correspondingly suppress cell apoptosis and DNA damage. As expected, we found that, compared with the nanomaterial-intoxicated animals, the tail length, tail DNA%, and the mRNA expression levels of caspase-3, Bax, and FAS, as well as the TUNEL apoptotic index, were decreased, and the mRNA expression level of Bcl2 was increased after supplementation with flavonoids. Also, these results on apoptotic indicators were almost not changed by subgroup factors. In addition to apoptosis and DNA damage, previous studies showed that high amounts of NO (65), VEGF (66), and MPO (67) could be synthesized and released in cells in response to ROS and inflammation stimuli. All the enhanced NO (68), VEGF (69), and MPO (70) could mediate an increase in the permeability of vascular endothelium, which may result in the leakage of plasma albumin to tissues and cause hypoxia and edema of organs, ultimately triggering the function dysfunction and exacerbating the disease progression. Thus, NO, VEGF, and MPO were also therapeutic targets to prevent and treat nanomaterial-induced organ injuries. This hypothesis was confirmed by our study which showed that the levels of NO, VEGF, and MPO were significantly reduced by flavonoids. All these alterations in the oxidative stress, inflammation, cell apoptosis, DNA damage, and endothelial dysfunction via supplementation with flavonoids may ultimately lead to the attenuation of organ injuries and function failure consequences. As anticipated, our meta-analysis results showed that some liver, kidney, testis, and brain functional biomarkers were significantly improved by flavonoids.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The first was a limited number of included studies, which led to fewer data available to evaluate the influence on some indicators (e.g., Nrf2, IL-1β, etc.) and no data obtainable to determine the effects of other flavonoid types (except for three subclasses we studied) and other organ injuries. Second, the design was variable for included studies, with different nanomaterial types, subclasses, dosages, intervention durations, routes of flavonoids, sample sources, and animal species, all of which contributed to the presence of considerably high heterogeneity among studies and thus may weaken the robustness of our conclusions. Third, unlike clinical trials where randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding of outcome assessment were mandatory, these details were rarely mentioned in our included animal experiments, resulting in an unclear risk of bias present in the quality assessment. Fourth, some data were extracted from the bar graphs, which may be slightly different from the real data. Accordingly, more experiments and evidence-based studies are needed to confirm the effects of flavonoids on nanomaterial-induced toxicities.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests that supplementation with flavonoids may be an effective measure to prevent nanomaterial-induced organ injuries by attenuation of oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, DNA damage, and endothelial dysfunction.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

DX, JH, and XL conceived the idea and designed the study. DX and JH collected the data and performed the statistical analysis. DX wrote the manuscript. TW, WX, QM, and KC contributed to the interpretation of the results. XL revised the manuscript and was the guarantor of the overall content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0204600) and the Project funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M621322 and 2018T110324) is greatly acknowledged.

Conflict of Interest

TW was employed by Shanghai Jing Rui Yang Industrial Co., Ltd. WX was employed by Shanghai Nutri-woods Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. QM was employed by Shanghai Pechoin Daily Chemical Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.929343/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | The structure of each flavonoid.

Abbreviations

NiONPs, nickel oxide nanoparticles; MDA, malonaldehyde; GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TIO2NPs, titanium dioxide nanoparticles; IONP, iron oxide nanoparticle; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; ZnONP, zinc oxide nanoparticle; PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis; PICOS, participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; CAT, catalase; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; GR, glutathione reductase; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; CRP, C-reactive protein; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NO, nitric oxide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; 17β-HSD, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type; AChE, acetylcholinesterase; FAS, Fas cell surface death receptor; Bcl2, B-cell lymphoma-2; Bax, BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval; AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; CNTs, carbon nanotubes; CuONPs, copper oxide nanoparticles; GNPs, gold nanoparticles; SiONPs, silica dioxide nanoparticles; MSNPs, mesoporous silica nanoparticles; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SIRT1, sirtuin 1.

Footnotes

References

1. Mabrouk M, Das DB, Salem ZA, Beherei HH. Nanomaterials for biomedical applications: production, characterisations, recent trends and difficulties. Molecules. (2021) 26:1077. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041077

2. Ranjha M, Shafique B, Rehman A, Mehmood A, Ali A, Zahra SM, et al. Biocompatible nanomaterials in food science, technology, and nutrient drug delivery: recent developments and applications. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:778155. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.778155

3. Fytianos G, Rahdar A, Kyzas GZ. Nanomaterials in cosmetics: recent updates. Nanomaterials. (2020) 10:979. doi: 10.3390/nano10050979

4. Khraisheh M, Elhenawy S, AlMomani F, Al-Ghouti M, Hassan MK, Hameed BH. Recent progress on nanomaterial-based membranes for water treatment. Membranes. (2021) 11:995. doi: 10.3390/membranes11120995

5. An C, Sun C, Li N, Huang B, Jiang J, Shen Y, et al. Nanomaterials and nanotechnology for the delivery of agrochemicals: strategies towards sustainable agriculture. J Nanobiotechnol. (2022) 20:11.

6. De Matteis V. Exposure to inorganic nanoparticles: routes of entry, immune response, biodistribution and in vitro/in vivo toxicity evaluation. Toxics. (2017) 5:29. doi: 10.3390/toxics5040029

7. Labouta HI, Asgarian N, Rinker K, Cramb DT. Meta-analysis of nanoparticle cytotoxicity via data-mining the literature. ACS Nano. (2019) 13:1583–94. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07562

8. Mutha RE, Tatiya AU, Surana SJ. Flavonoids as natural phenolic compounds and their role in therapeutics: an overview. Futur J Pharm Sci. (2021) 7:25. doi: 10.1186/s43094-020-00161-8

10. Ożarowski M, Mikołajczak PL, Kujawski R, Wielgus K, Klejewski A, Wolski H, et al. Pharmacological effect of quercetin in hypertension and its potential application in pregnancy-induced hypertension: review of in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2018) 2018:7421489. doi: 10.1155/2018/7421489

11. Yao J, Zhang Y, Wang XZ, Zhao J, Yang ZJ, Lin YP, et al. Flavonoids for treating viral acute respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 randomized controlled trials. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:814669. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.814669

12. Zhang XW, Chen JY, Ouyang D, Lu JH. Quercetin in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of preclinical studies. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:493. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020493

13. An H, Ling C, Xu M, Hu M, Wang H, Liu J, et al. Oxidative damage induced by nano-titanium dioxide in rats and mice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2020) 194:184–202. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01761-z

14. Vilas-Boas V, Vinken M. Hepatotoxicity induced by nanomaterials: mechanisms and in vitro models. Arch Toxicol. (2021) 95:27–52. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02940-x

15. Al-Rasheed NM, Faddah LM, Mohamed AM, Abdel Baky NA, Al-Rasheed NM, Mohammad RA. Potential impact of quercetin and idebenone against immuno-inflammatory and oxidative renal damage induced in rats by titanium dioxide nanoparticles toxicity. J Oleo Sci. (2013) 62:961–71. doi: 10.5650/jos.62.961

16. Fadda LM, Hagar H, Mohamed AM, Ali HM. Quercetin and idebenone ameliorate oxidative stress, inflammation, DNA damage, and apoptosis induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in rat liver. Dose Response. (2018) 16:1559325818812188. doi: 10.1177/1559325818812188

17. Ansar S, Abudawood M, Hamed SS, Aleem MM. Exposure to Zinc Oxide nanoparticles induces neurotoxicity and proinflammatory response: amelioration by hesperidin. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2017) 175:360–6. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0770-8

18. Ansar S, Abudawood M, Alaraj ASA, Hamed SS. Hesperidin alleviates zinc oxide nanoparticle induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. (2018) 19:65. doi: 10.1186/s40360-018-0256-8

19. Ali AA, Mansour AB, Attia SA. The potential protective role of apigenin against oxidative damage induced by nickel oxide nanoparticles in liver and kidney of male Wistar rat, Rattus norvegicus. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2021) 28:27577–92. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12632-3

20. Shahin NN, Mohamed MM. Nano-sized titanium dioxide toxicity in rat prostate and testis: possible ameliorative effect of morin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. (2017) 334:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.08.014

21. Faddah LM, Abdel Baky NA, Al-Rasheed NM, Al-Rasheed NM, Fatani AJ, Atteya M. Role of quercetin and arginine in ameliorating nano zinc oxide-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2012) 12:60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-60

22. Abdelkarem HM, Fadda LM, Kaml OR. Alleviation of bone markers in rats induced nano-zinc oxide by qurecetin and α-lipolic acid. Toxicol Mech Methods. (2016) 26:692–9. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2016.1236424

23. Akhlaghi M, Ghobadi S, Mohammad Hosseini M, Gholami Z, Mohammadian F. Flavanols are potential anti-obesity agents, a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2018) 28:675–90. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.04.001

24. Ali S, Corbi G, Maes M, Scapagnini G, Davinelli S. Exploring the impact of flavonoids on symptoms of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antioxidants. (2021) 10:1644. doi: 10.3390/antiox10111644

25. Davinelli S, Ali S, Scapagnini G, Costagliola C. Effects of flavonoid supplementation on common eye disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:651441. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.651441

26. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2014) 14:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-43

27. Abdelazeim SA, Shehata NI, Aly HF, Shams SGE. Amelioration of oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis in copper oxide nanoparticles-induced liver injury in rats by potent antioxidants. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10812. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67784-y

28. Dora MF, Taha NM, Lebda MA, Hashem AE, Elfeky MS, El-Sayed YS, et al. Quercetin attenuates brain oxidative alterations induced by iron oxide nanoparticles in rats. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:3829. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083829

29. Abdelhalim MAK, Qaid HA, Al-Mohy Y, Al-Ayed MS. Effects of quercetin and arginine on the nephrotoxicity and lipid peroxidation induced by gold nanoparticles in vivo. Int J Nanomed. (2018) 13:7765–70. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S183281

30. Abdelhalim MAK, Moussa SAA, Qaid HAY. The protective role of quercetin and arginine on gold nanoparticles induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Int J Nanomed. (2018) 13:2821–5. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S160995

31. Khorsandi L, Orazizadeh M, Moradi-Gharibvand N, Hemadi M, Mansouri E. Beneficial effects of quercetin on titanium dioxide nanoparticles induced spermatogenesis defects in mice. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2017) 24:5595–606. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8325-2

32. Alidadi H, Khorsandi L, Shirani M. Effects of quercetin on tubular cell apoptosis and kidney damage in rats induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Malays J Med Sci. (2018) 25:72–81. doi: 10.21315/mjms2018.25.2.8

33. Hussein MM, Ali HA, Saadeldin IM, Ahmed MM. Querectin alleviates zinc oxide nanoreprotoxicity in male albino rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. (2016) 30:489–96. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21812

34. González-Esquivel AE, Charles-Niño CL, Pacheco-Moisés FP, Ortiz GG, Jaramillo-Juárez F, Rincón-Sánchez AR. Beneficial effects of quercetin on oxidative stress in liver and kidney induced by titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in rats. Toxicol Mech Methods. (2015) 25:166–75. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2015.1006491

35. Awogbindin IO, Maduako IC, Adedara IA, Owumi SE, Ajeleti AO, Owoeye O, et al. Kolaviron ameliorates hepatic and renal dysfunction associated with multiwalled carbon nanotubes in rats. Environ Toxicol. (2021) 36:67–76. doi: 10.1002/tox.23011

36. Adedara IA, Awogbindin IO, Owoeye O, Maduako IC, Ajeleti AO, Owumi SE, et al. Kolaviron via anti-inflammatory and redox regulatory mechanisms abates multi-walled carbon nanotubes-induced neurobehavioral deficits in rats. Psychopharmacology. (2020) 237:1027–40.

37. Arisha AH, Ahmed MM, Kamel MA, Attia YA, Hussein MMA. Morin ameliorates the testicular apoptosis, oxidative stress, and impact on blood-testis barrier induced by photo-extracellularly synthesized silver nanoparticles. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2019) 26:28749–62. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06066-1

38. Hussein MMA, Gad E, Ahmed MM, Arisha AH, Mahdy HF, Swelum AA, et al. Amelioration of titanium dioxide nanoparticle reprotoxicity by the antioxidants morin and rutin. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2019) 26:29074–84. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06091-0

39. El-Wafaey DI, Nafea OE. Naringenin alleviates hepatic injury in zinc oxide nanoparticles exposed rats: impact on oxido-inflammatory stress and apoptotic cell death. Toxicol Mech Methods. (2022) 32:58–66. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2021.1965275

40. Ahmed MM, Hussein MMA. Neurotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles and the protective role of rutin. Biomed Pharmacother. (2017) 90:731–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.026

41. Lim JO, Shin NR, Seo YS, Nam HH, Ko JW, Jung TY, et al. Silibinin attenuates silica dioxide nanoparticles-induced inflammation by suppressing TXNIP/MAPKs/AP-1 signaling. Cells. (2020) 9:678. doi: 10.3390/cells9030678

42. Elblehi SS, Abd El-Maksoud EM, Aldhahrani A, Alotaibi SS, Ghamry HI, Elgendy SA, et al. Quercetin abrogates oxidative neurotoxicity induced by silver nanoparticles in wistar rats. Life (Basel). (2022) 12:578. doi: 10.3390/life12040578

43. Wang Y, Chang W, Li X, Jiang Z, Zhou D, Feng Y, et al. Apigenin exerts chemopreventive effects on lung injury induced by SiO(2) nanoparticles through the activation of Nrf2. J Nat Med. (2022) 76:119–31. doi: 10.1007/s11418-021-01561-7

44. Wang T, Zhang Z, Xie M, Li S, Zhang J, Zhou J. Apigenin attenuates mesoporous silica nanoparticles-induced nephrotoxicity by activating FOXO3a. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2021) 200:2793–806. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02871-3

45. Viswanatha GL, Shylaja H, Moolemath Y. The beneficial role of Naringin- a citrus bioflavonoid, against oxidative stress-induced neurobehavioral disorders and cognitive dysfunction in rodents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Pharmacother. (2017) 94:909–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.072

46. Treml J, Šmejkal K. Flavonoids as potent scavengers of hydroxyl radicals. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. (2016) 15:720–38. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12204

47. Zeinvand-Lorestani M, Karimi S, Khorsandi L. Quercetin ameliorates cytotoxic effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on sertoli cells by enhancing autophagy and suppressing oxidative stress. Andrologia. (2021) 53:e13988. doi: 10.1111/and.13988

48. Niu L, Shao M, Liu Y, Hu J, Li R, Xie H, et al. Reduction of oxidative damages induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles correlates with induction of the Nrf2 pathway by GSPE supplementation in mice. Chem Biol Interact. (2017) 275:133–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.07.025

49. He L, He T, Farrar S, Ji L, Liu T, Ma X. Antioxidants maintain cellular redox homeostasis by elimination of reactive oxygen species. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2017) 44:532–53. doi: 10.1159/000485089

50. Galindo P, González-Manzano S, Zarzuelo MJ, Gómez-Guzmán M, Quintela AM, González-Paramás A, et al. Different cardiovascular protective effects of quercetin administered orally or intraperitoneally in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Funct. (2012) 3:643–50. doi: 10.1039/c2fo10268d

51. Chen S, Chen Y, Chen Y, Yao Z. InP/ZnS quantum dots cause inflammatory response in macrophages through endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress. Int J Nanomed. (2019) 14:9577–86. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S218748

52. Jeong SH, Kim HJ, Ryu HJ, Ryu WI, Park YH, Bae HC, et al. ZnO nanoparticles induce TNF-α expression via ROS-ERK-Egr-1 pathway in human keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci. (2013) 72:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.08.002

53. Gu Y, Wang Y, Zhou Q, Bowman L, Mao G, Zou B, et al. Inhibition of nickel nanoparticles-induced toxicity by Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate in JB6 cells may be through down-regulation of the MAPK signaling pathways. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0150954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150954

54. Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Hayashi M, Sekine H, et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:11624. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11624

55. Zhao X, Wu Y, Li J, Li D, Jin Y, Zhu P, et al. JNK activation-mediated nuclear SIRT1 protein suppression contributes to silica nanoparticle-induced pulmonary damage via p53 acetylation and cytoplasmic localisation. Toxicology. (2019) 423:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2019.05.003

56. Li Y, Liu T, Li Y, Han D, Hong J, Yang N, et al. Baicalin ameliorates cognitive impairment and protects microglia from LPS-Induced neuroinflammation via the SIRT1/HMGB1 pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2020) 2020:4751349. doi: 10.1155/2020/4751349

57. Shen P, Lin W, Ba X, Huang Y, Chen Z, Han L, et al. Quercetin-mediated SIRT1 activation attenuates collagen-induced mice arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol. (2021) 279:114213. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114213

58. Yang H, Wang H, Andersson U. Targeting inflammation driven by HMGB1. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:484. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00484

59. Shi H, Huang X, Yan Z, Yang Q, Wang P, Li S, et al. Effect of clostridium perfringens type C on TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in piglet small intestines. Microb Pathog. (2019) 135:103567. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103567

60. Deng Z, Jin J, Wang Z, Wang Y, Gao Q, Zhao J. The metal nanoparticle-induced inflammatory response is regulated by SIRT1 through NF-κB deacetylation in aseptic loosening. Int J Nanomed. (2017) 12:3617–36. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S124661

61. Han B, Pei Z, Shi L, Wang Q, Li C, Zhang B, et al. TiO2 nanoparticles caused DNA damage in lung and extra-pulmonary organs through ROS-Activated FOXO3a signaling pathway after intratracheal administration in rats. Int J Nanomed. (2020) 15:6279–94. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S254969

62. Ali D, Tripathi A, Al Ali H, Shahi Y, Mishra KK, Alarifi S, et al. ROS-dependent Bax/Bcl2 and caspase 3 pathway-mediated apoptosis induced by zineb in human keratinocyte cells. Onco Targets Ther. (2018) 11:489–97. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S140358

63. Tsuboi M, Kawakami A, Nakashima T, Matsuoka N, Urayama S, Kawabe Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta increase the Fas-mediated apoptosis of human osteoblasts. J Lab Clin Med. (1999) 134:222–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90201-9

64. Faletti L, Peintner L, Neumann S, Sandler S, Grabinger T, Mac Nelly S, et al. TNFα sensitizes hepatocytes to FasL-induced apoptosis by NFκB-mediated Fas upregulation. Cell Death Dis. (2018) 9:909.

65. Wieroñska JM, Cieślik P, Kalinowski L. Nitric oxide-dependent pathways as critical factors in the consequences and recovery after brain ischemic hypoxia. Biomolecules. (2021) 11:1097. doi: 10.3390/biom11081097

66. Tseng CY, Wang JS, Chao MW. Causation by diesel exhaust particles of endothelial dysfunctions in cytotoxicity, pro-inflammation, permeability, and apoptosis induced by ROS generation. Cardiovasc Toxicol. (2017) 17:384–92. doi: 10.1007/s12012-016-9364-0

67. Ndrepepa G. Myeloperoxidase - A bridge linking inflammation and oxidative stress with cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta. (2019) 493:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.02.022

68. Stark RJ, Koch SR, Choi H, Mace EH, Dikalov SI, Sherwood ER, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase modulates Toll-like receptor 4-mediated IL-6 production and permeability via nitric oxide-independent signaling. FASEB J. (2018) 32:945–56. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700410R

69. Wang L, Astone M, Alam SK, Zhu Z, Pei W, Frank DA, et al. Suppressing STAT3 activity protects the endothelial barrier from VEGF-mediated vascular permeability. Dis Model Mech. (2021) 14:dmm049029.

Keywords: nanomaterials, oxidative stress, inflammation, flavonoids, meta-analysis

Citation: Xie D, Hu J, Wu T, Xu W, Meng Q, Cao K and Luo X (2022) Effects of Flavonoid Supplementation on Nanomaterial-Induced Toxicity: A Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Animal Studies. Front. Nutr. 9:929343. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.929343

Received: 27 April 2022; Accepted: 19 May 2022;

Published: 14 June 2022.

Edited by:

Dongmin Liu, Virginia Tech, United StatesReviewed by:

Fatma Mohamady El-Demerdash, Alexandria University, EgyptHongwei Si, Tennessee State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Xie, Hu, Wu, Xu, Meng, Cao and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaogang Luo, eGdsdW9Ac3VkYS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Dongli Xie1†

Dongli Xie1† Xiaogang Luo

Xiaogang Luo