95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Nutr. , 03 March 2022

Sec. Nutrition and Sustainable Diets

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.858475

This article is part of the Research Topic Innovation and Trends in the Global Food Systems, Dietary Patterns and Healthy Sustainable Lifestyle in the Digital Age View all 16 articles

Si Si Jia1*

Si Si Jia1* Alice A. Gibson2,3

Alice A. Gibson2,3 Ding Ding3,4

Ding Ding3,4 Margaret Allman-Farinelli3,5

Margaret Allman-Farinelli3,5 Philayrath Phongsavan3,4

Philayrath Phongsavan3,4 Julie Redfern1,6

Julie Redfern1,6 Stephanie R. Partridge1,3,4

Stephanie R. Partridge1,3,4Online food delivery usage has soared during the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic which has seen increased demand for home-delivery during government mandated stay-at-home periods. Resulting implications from COVID-19 may threaten decades of development gains. It is becoming increasingly more important for the global community to progress toward sustainable development and improve the wellbeing of people, economies, societies, and the planet. In this perspective article, we discuss how the rising use of these platform-to-consumer delivery operations may impede advances toward the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, online food delivery services may disrupt SDGs that address good health and wellbeing, responsible consumption and production, climate action and decent work and economic growth. To mitigate potential negative impacts of these meal delivery apps, we have proposed a research and policy agenda that is aligned with entry points within a systems approach identified by the World Health Organization. Food industry reforms, synergised public health messaging and continuous monitoring of the growing impact of online food delivery should be considered for further investigation by researchers, food industry, governments, and policy makers.

Unhealthy diets, non-communicable diseases, urbanization, and climate change are recognized as significant challenges to global health (1). The United Nations have urged countries to act on 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across economic, social and environmental dimensions to promote healthy lives and wellbeing and make cities inclusive, safe, and sustainable by 2030 (2). Online food delivery services (OFDS) are potentially impeding our progress toward the SDGs—impacting the way we eat, work, and care for the environment. Defined as “platform-to-consumer delivery operations” of ready-to-consume meals, OFDS offer delivery of a wide variety of takeout foods and beverages from kitchens to doorsteps (3).

The OFD industry is now widespread across the globe and big multinational corporations are dominating the market. Billion-dollar companies such as UberEats, DoorDash, and Just Eat operate in thousands of cities and show no sign of slowing down. Globally, OFDS market revenue increased by 27% in 2020, reaching $136.4 billion USD (4). These services are likely to proliferate further, as UberEats estimates that despite the return to dine-in restaurants, consumers are now spending three times more on OFDS compared to pre-pandemic levels (5). Furthermore, Just Eat or otherwise known as Menulog, reported a 79% increase in total orders between 2020 and 2021, across its 17 operating countries including UK, Germany, Canada, and Netherlands (6).

Considering the growing prevalence and market influence of OFDS, it is important to track the impact of OFDS on key public health challenges, such as increasing accessibility of unhealthy foods, promotion of excessive consumption, poor working conditions of delivery couriers in a gig economy and the environmental implications of takeout food packaging. This perspective piece will discuss how OFDS may disrupt progress toward SDGs that address good health and wellbeing, responsible consumption and production, climate action and decent work and economic growth.

OFDS may pose a considerable risk to the aim of SDG 3 to “Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages”. Research has shown that these OFDS have an abundant offering of menu items that are of poor nutritional quality. From an investigation of 680 popular food outlets on the market leading OFDS in Sydney, Australia, 37.6% (256/680) of popular outlets were classified as a “fast-food franchise” store, and out of the 2,463 most popular menu items identified, 2,358 (95.7%) were identified as “discretionary foods” (7), characterized as high in saturated fat, sodium and sugar, and not essential for health.

Moreover, the two leading OFDS (UberEats, Menulog) in Australia are partnered with the top 10 fast food franchise stores (Subway, McDonalds, Dominos, KFC, Hungry Jacks, Red Rooster, Nando's, Pizza Hut, Zambero, Oporto) (8). This signifies the dominance of fast-food franchise outlets on these platforms which are now another additional avenue for consumers to access their menu items. It is well-known that offerings from fast food franchise outlets are “energy-dense and nutrient poor” (9) and evidence has highlighted the strong association between high fast-food consumption and obesity (10). Furthermore, research has shown that diets high in inflammatory foods such as refined grains, sugary drinks, processed meats and other “junk foods”, have been associated with increased inflammation in the body and can elevate subsequent risk of heart disease by 46% and stroke by 28% (11). These highly inflammatory foods are widely available on these online food delivery platforms as shown in findings from a recent cross-sectional study (12). From over 196 independent takeaway food outlets available on UberEats in Sydney, Australia, discretionary cereal-based mixed meals was the largest category found within complete menus (42.3%, 5849/13,841). These include foods such as pizzas, burgers, pides, pasta, wraps, and sandwiches (12).

A Canadian study analyzed the full menus of retailers partnering with a large OFDS and similarly found low Healthy Eating Index-2015 scores—ranging from 19.95 to 50.78 out of 100 (with a score of 100 being the healthiest) (13). This study also found a mean delivery distance of 3.7 km or 2.3 miles measuring from postal codes in Ontario to online food retailers (13). Australian research has likewise, demonstrated that the mean delivery distance from food outlet to suburbs was 3 km, and around 90% of delivery distances were greater than 1 km (7)—a distance that typically defines the neighborhood food environment. The neighborhood food environment reflects the spatial extent of an individual's typical shopping behavior which could be reasonably walked by an adult in 15–20 min (14). As such, these platform-to-consumer services may be expanding local neighborhood food environments.

Altogether, findings suggest OFDS are expanding the traditional definition of the neighborhood food environment, increasing the accessibility of food outlets which mostly offer items with poor nutritional quality.

In addition to increasing accessibility of food outlets, OFDS further encourage excessive consumption with aggressive marketing and promotion tactics. Macromarketing researchers are wary of the current marketing systems which promote an era of excess as business models choose to “create” rather than “address” consumer needs, without consideration of the waste generated from overall consumption (15). OFDS may add further burden to unsustainable practices of mass consumerism which threaten progress toward SDG 12: “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns”.

UberEats and Menulog frequently distribute promotional vouchers that offer free meals, discounts, and free delivery (16, 17). These are often disseminated through emails to past customers signed up to the OFD platform (18) or handed-out in person at high-traffic locations such as train stations (19). Moreover, there is evidence that OFD companies “COVID-wash” their social media promotions—a practice where companies align themselves with social or health issues of COVID-19 to enhance their own image (20). In a content analysis of Instagram posts from leading OFDS in 2020 during the pandemic, the most used COVID-19 marketing strategy was related to “combatting the pandemic” (76/123, 62%) (21). This theme helped brands position themselves to be “in this together” and encourage consumers to “support their local businesses”. These findings were echoed in another content analysis study conducted in New Zealand. The most used theme in 36% of all COVID-19 related social media posts intended to generate feelings of community support during the challenging time. Fast-food brands were also found to be the largest proponents of COVID-washing, accounting for 46% of all COVID-19 posts (20).

Furthermore, during the pandemic, an increase in social media posts promoting “junk foods” from leading OFD brands was observed. In a recent study, we found junk foods accounted for 69.1% of all food and beverage items featured, compared to 58.3% in 2019 (21). Similarly, a study from Brazil indicated widespread presence of unhealthy food advertising as ultra-processed beverages such as soft drinks were among the most shown in advertisements for OFDS throughout COVID-19. Free delivery also prevailed in advertisements of junk food items such as ice cream, candy, high sodium snacks, and pizza (22). More research found that menus offering unhealthy meals had more photos and discounts compared to meals offering unprocessed and/or minimally processed foods (23). Taken together, OFDS continue to facilitate fast-food delivery at heavily discounted prices and excess promotions, perpetuating the culture of excessive consumption.

Plastic waste is a key global environmental concern with annual plastic consumption currently at over 300 million tons, which is expected to double in the next 20 years (24). High volumes of online food delivery consumption exacerbates plastic waste and adds to the increasing contamination of natural environments such as the ocean, freshwater systems, and terrestrial areas (25). Subsequently, OFDS may have a huge climate cost and are another impediment to SDG 13: “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”.

Takeout meals ordered from OFDS can come with extensive quantities of plastic material, namely food containers, cutlery, napkins, and plastic bags among others (26). These materials are often single-use, requiring large quantities of energy and raw materials to produce, transport, and be disposed (27). A study on the environmental impacts of takeout food containers revealed that single-use polypropylene containers are the worst packaging material for takeout food, with many negative impacts on the environment (26). In China, researchers found that the total amount of packaging waste from food delivery surged from 0.2 million metric tons in 2015 to 1.5 million metric tons in 2017 (28). Plastic containers made from polypropylene and polystyrene foam accounted for approximately 75% of the total food delivery packaging waste in weight. COVID-19 lockdowns further aggravated China's plastic waste dilemma: during the lockdown in Wuhan, an average of 130,000 takeout orders were made per day, which totaled to more than 279,500 m of lunchboxes over a 6-week period (29).

Excessive energy consumption and carbon emissions are associated with the waste produced from food delivery. Based on annual online food delivery data of 179.2 million active users, a 2016 Chinese study found an average ordering frequency of 2 times/week and average delivery distances of 25 km (30), which resulted in an estimated Green House Gas (GHG) emission of 73.89 Gigatonnes (Gt) carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions (CO2eq) (30). In Australia, COVID-19 lockdowns led to a 20% increase in household solid wastes, partly due to a surge in food deliveries which contributed sizeable amounts of paper, plastic packaging waste and single-use waste (31). Another study found in 2018, the disposal of single use packaging from online food orders in Australia led to 5,600 tons of CO2eq (32). With online food orders expected to increase to 65 million in 2024, researchers project a 132% rise in carbon emissions to 13,200 tons of CO2eq (32). As such, the environmental threat of OFDS is progressively evident and needs to be considered as governments globally move toward carbon emission reduction targets.

Instead of steering toward the SDG 8: “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”, OFDS stimulate the gig economy and may veer away from sustainable economic growth that will create quality jobs. While OFDS have facilitated new job opportunities and increased flexibility of work, the quality of these jobs is questionable with little-to-no employment rights and poor work health and safety conditions (33).

Advances in online technology have fuelled the rise of the “gig economy”—a free market system in which mobile apps or websites connect consumers with individual workers providing services. Gigs are denoted by short-term, one-off employment contracts mediated by online platforms which include online food delivery. Although spending on gig economy in Australia declined severely during the period of early COVID-19 lockdown restrictions in March 2020, it increased to 40% above pre-lockdown levels. This growth was almost entirely driven by the online food delivery sector, which itself increased by more than 100% between August and October 2020 (34). Indeed, UberEats Australia, a leading OFDS, has reported providing 59,000 work opportunities during 2020 which is an eight-fold increase since 2016 (5).

In a report on digital platform work in Australia, it has been revealed that food delivery workers choose to work with OFDS for flexibility and to supplement existing income streams (35). However, food delivery workers are more dependent on income generated from meal delivery compared to gig workers on other digital platforms (35). This report also suggests food delivery workers were more likely to work longer hours in a week and were more likely to say the income was essential for meeting basic needs (35). Moreover, food delivery platforms may vary in their contractual agreements where workers may be independent contractors rather than employees. This places workers at risk of insecure income, no insurance, personal or paid leave, no workers compensation, superannuation or certain taxes. Over a long term, gig work as a food delivery worker may be financially untenable. A gig worker who spends 5–10 years in the gig economy full time, could potentially be $40,000–$100,000 AUD worse off in accumulated superannuation at retirement compared to a minimum wage earner (34). Major reforms of OFD work in the gig economy are required to increase the quality of these jobs, improve the livelihood of workers and be sustainable in the long term.

Existing reports shows achieving the 2030 UN SDGs will require tremendous efforts ahead by governments and industries globally given the considerable setback induced by the COVID-19 pandemic (36). A systems approach to the complexities of public health issues has been proposed by notable researchers—as outlined in the 2011 and 2015 Lancet Series on Obesity (37, 38) and has been a developing research area to inform the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on obesity prevention (39). The synergising of goals and targets within and between systems affecting health including manufacturing, financial, transportation, and food, may be essential to meaningful progress. The EAT-Lancet commission on Food, Planet, and Health is an example which shows the power of goal alignment (40). This report has outlined the role of diet with human health and environmental sustainability—addressing both the rise in unhealthy diets, the targets of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement. As research on the impacts of OFDS is still in its infancy, robust solutions to resolving the issues outlined in this perspective have yet to be developed. However, using a similar systems-based approach, the following calls to action identify areas for existing systems to merge.

The World Health Organization (WHO) (41) has now acknowledged the growing impact of online food environments on people's diet choices. In a recently published report, WHO Europe has proposed the use of a systems approach to make informed decisions on potential interventions and/or regulation of these OFDS or otherwise known as “Meal Delivery Apps” (MDA). Taking a systems approach, several entry points to change were identified. These include Nutrition, Physical Activity, Alcohol consumption, Labor, Road Safety, Food Safety which are key elements that use existing mechanisms to solve complex issues (41). The entry points align with the SDGs discussed in this perspective and may benefit from collective action by food industry, governments, policy makers and researchers.

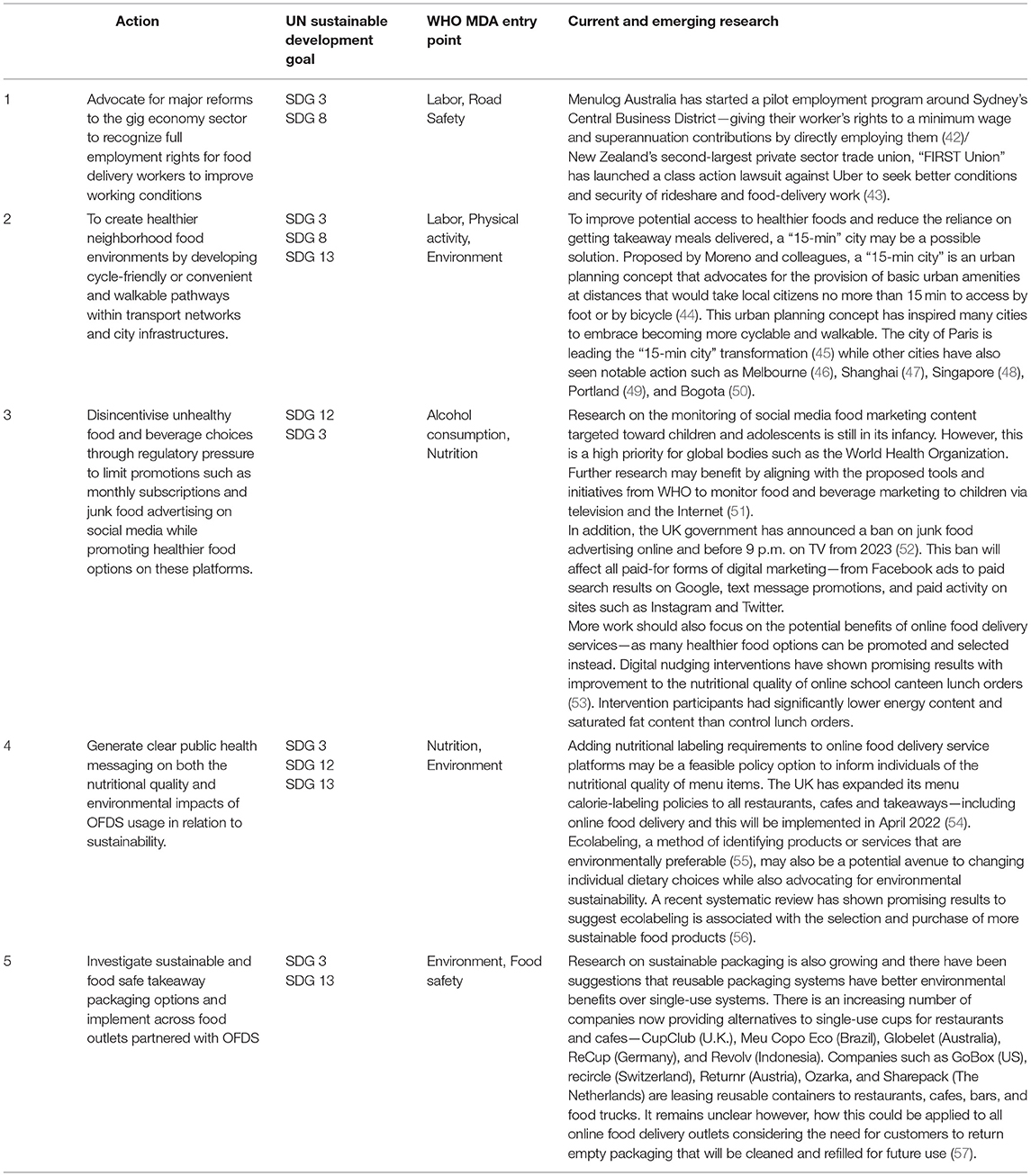

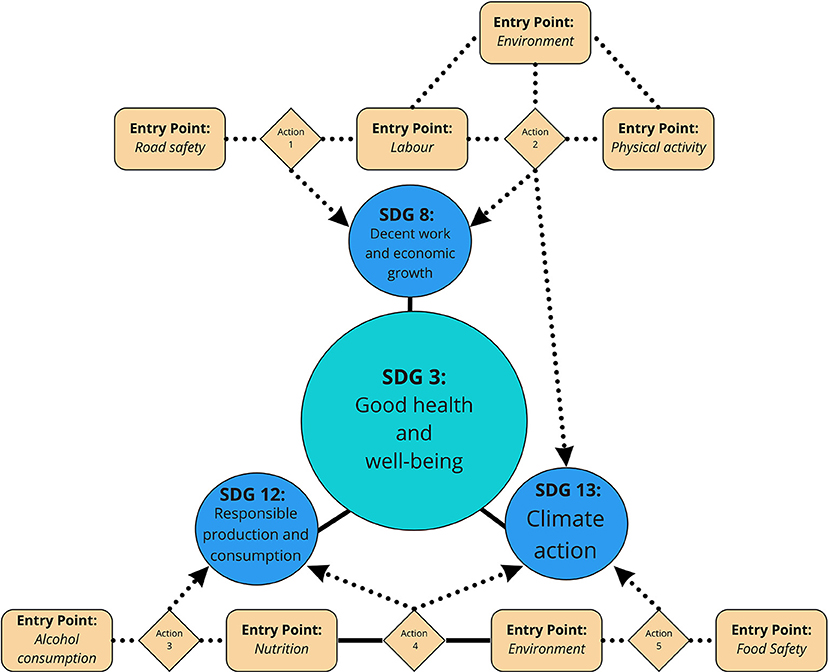

In Table 1, we propose a research and policy agenda with action points that address SDGs and entry points from the WHO report. We have also illustrated examples of current and emerging research across these action points. Figure 1 was designed to demonstrate how these action points can work together to strive toward SDG 3: “Good Health and Wellbeing” for the benefit of public health. The proposed action points may also later converge with recommendations outlined from WHO Europe's commentary piece (58).

Table 1. Proposed action points to mitigate negative impacts of online food delivery services and address the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals and entry points identified in the WHO Meal Delivery Apps Report.

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram identifying areas for entry points and Sustainable Development Goals relating to online food delivery services to merge, forming action points to ultimately address SDG 3 Good Health and Wellbeing. Actions are defined and described in detail in Table 1.

As research on the impact of OFDS continues to grow, ongoing monitoring and evaluation is critical to the development of policy options for regulating the digital food environment. Dashboards are considered as useful tools to help users visualize and understand complex information in a snapshot. They have been developed to monitor global food systems (59) and food environments (60) and may also be essential to tracking progress of online food delivery services. We therefore also propose the inclusion of online food settings within existing monitoring and evaluation frameworks of food systems and food environments (60).

In a world now grappling with ongoing repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting societal and environmental changes exacerbated by COVID may further derail the trajectory toward meeting the SDGs set by the United Nations. OFDS are likely to proliferate, providing valued convenience in an increasingly fast-paced modern society. However, the potential disruption to our health and the environment is substantial, interfering with overarching SDGs. Food industry reforms synergised public health messaging and continuous monitoring of the growing impact of OFDS may be part of the solution to collectively address the issues of sustainability, environmental health, decent work and economic growth and nutrition. Multidisciplinary action and research are urgently needed to further investigate such solutions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

SJ and SP contributed to the conceptualization of the manuscript. SJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and designed all tables and figures included in submission. SP provided primary supervision of SJ, reviewing the first draft of the manuscript. AAG, DD, PP, MA-F, and JR edited and reviewed the manuscript drafts. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

SJ was supported by the Australian Government's Research Training Program Stipend Scholarship, AAG receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, NSW Health and Diabetes Australia, JR receives fellowship and research grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council, NSW Health, and Medical Research Future Fund, DD receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and NSW Health, MA-F receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, NSW Health and Cancer Council NSW, PP receives funding from NSW Health, SP receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, National Heart Foundation, NSW Health and the Medical Research Future Fund.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Giles-Corti B, Vernez-Moudon A, Reis R, Turrell G, Dannenberg AL, Badland H, et al. City planning and population health: a global challenge. Lancet. (2016) 388:2912–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30066-6

2. United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: United Nations. (2015). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed January 10, 2022).

3. Statista. Online Food Delivery: Statista. (2021). Available online at https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/eservices/online-food-delivery/australia (accessed January 10, 2022).

4. AJOT. Online Food Delivery Market to Hit $151.5B in Revenue and 1.6B Users in 2021 A 10% Jump in a Year. (2021). Available online at: https://ajot.com/news/online-food-delivery-market-to-hit-151.5b-in-revenue-and-1.6b-users-in-2021-a-10-jump-in-a-year (accessed January 10, 2022).

7. Partridge SR, Gibson AA, Roy R, Malloy JA, Raeside R, Jia SS, et al. Junk food on demand: a cross-sectional analysis of the nutritional quality of popular online food delivery outlets in Australia and New Zealand. Nutrients. (2020) 12:3107. doi: 10.3390/nu12103107

8. Franchise Buyer. The 10 Biggest Fast Food Franchises in the Australian Market. (2020). Available online at: https://www.franchisebuyer.com.au/articles/the-10-biggest-fast-food-franchises-in-the-australian-market (accessed October 18, 2021).

9. Kirkpatrick SI, Reedy J, Kahle LL, Harris JL, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Krebs-Smith SM. Fast-food menu offerings vary in dietary quality, but are consistently poor. Public Health Nutr. (2014) 17:924–31. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005563

10. Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev. (2008) 9:535–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00477.x

11. Li J, Lee DH, Hu J, Tabung FK, Li Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of cardiovascular disease among men and women in the U.S. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2181–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.535

12. Wang C, Korai A, Jia SS, Allman-Farinelli M, Chan V, Roy R, et al. Hunger for home delivery: cross-sectional analysis of the nutritional quality of complete menus on an online food delivery platform in Australia. Nutrients. (2021) 13:905. doi: 10.3390/nu13030905

13. Brar K, Minaker LM. Geographic reach and nutritional quality of foods available from mobile online food delivery service applications: novel opportunities for retail food environment surveillance. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:458. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10489-2

14. Smith G, Gidlow C, Davey R, Foster C. What is my walking neighbourhood? A pilot study of English adults' definitions of their local walking neighbourhoods. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2010) 7:34. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-34

15. Wooliscroft B, Ganglmair-Wooliscroft A. Growth, excess and opportunities:marketing systems' contributions to society. J Macromarket. (2018) 38:355–63. doi: 10.1177/0276146718805804

16. Mott B. 10 takeaway and delivery food tips. In: Berry L, editor. Money Saving Expert (2021). Available online at: https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/deals/deals-hunter/2021/01/takeaway-and-delivery-food-tips/ (accessed June 21, 2021).

17. Business Insider. Londoners Are Gaming UberEats to Get Free Food. (2016). Available online at: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/how-to-get-free-ubereats-vouchers-promotions-food-hundreds-pounds-london-2016-9?r=US&IR=T (accessed September 20, 2021).

18. Sun T. Uber Annoying Angry Uber Eats Customers Left Hungry After Discount Code Doesn't Work 'Everything Is Unavailable'. (2019). Available online at: https://www.thesun.co.uk/money/10627147/uber-eats-discount-code-doesnt-work-everything-unavailable/ (accessed September 20, 2021).

19. Wongm Rail Gallery. Handing Out Uber Eats Vouchers on the Main Concourse at Southern Cross Station. Melbourne, VIC (2018). Available online at: https://railgallery.wongm.com/commercialising-commuters/F129_5537.jpg.html (accessed September 14, 2021).

20. Gerritsen S, Sing F, Lin K, Martino F, Backholer K, Culpin A, et al. The timing, nature and extent of social media marketing by unhealthy food and drinks brands during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:65. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.645349

21. Jia SS, Raeside R, Redfern J, Gibson AA, Singleton A, Partridge SR. #SupportLocal: how online food delivery services leveraged the COVID-19 pandemic to promote food and beverages on Instagram. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 24:4812–22. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021002731

22. Horta PM, Matos JdP, Mendes LL. Digital food environment during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Brazil: an analysis of food advertising in an online food delivery platform. Brit J Nutr. (2020) 126:767–72. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520004560

23. Horta PM, Souza JPM, Rocha LL, Mendes LL. Digital food environment of a Brazilian metropolis: food availability and marketing strategies used by delivery apps. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 24:544–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020003171

25. Barnes DK, Galgani F, Thompson RC, Barlaz M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. (2009) 364:1985–98. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0205

26. Gallego-Schmid A, Mendoza JMF, Azapagic A. Environmental impacts of takeaway food containers. J Clean Product. (2019) 211:417–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.220

27. Yi Y, Wang Z, Wennersten R, Sun Q. Life cycle assessment of delivery packages in China. Energy Proc. (2017) 105:3711–9. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.860

28. Song G, Zhang H, Duan H, Xu M. Packaging waste from food delivery in China's mega cities. Resour Conserv Recycl. (2018) 130:226–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.12.007

29. Liu J, Vethaak AD, An L, Liu Q, Yang Y, Ding J. An environmental dilemma for china during the COVID-19 pandemic: the explosion of disposable plastic wastes. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. (2021) 106:237–40. doi: 10.1007/s00128-021-03121-x

30. Jia X-x, Klemeš J, Varbanov P, Wan Alwi SR. Energy-emission-waste nexus of food deliveries in China. Chem Eng Trans. (2018) 70:661–6. doi: 10.3303/CET1870111

31. Infrastructure Australia. Infrastructure Beyond COVID-19: A National Study on the Impacts of the Pandemic on Australia. Australian Government (2020).

32. Arunan I, Crawford RH. Greenhouse gas emissions associated with food packaging for online food delivery services in Australia. Resour Conserv Recycl. (2021) 168:105299. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105299

33. Sprint Law. The Gig Economy Australian Law: What's Next? (2021). Available online at: https://sprintlaw.com.au/gig-economy-in-australia/ (accessed September 14, 2021).

34. Actuaries Institute. The Rise of the Gig Economy its Impact on the Australian Workforce. (2020). Available online at: https://www.actuaries.digital/2020/12/16/the-rise-of-the-gig-economy-and-its-impact-on-the-australian-workforce/

35. McDonald P, Williams P, Stewart A, Oliver D, Mayes R. Digital Platform Work in Australia: Preliminary Findings from a National Survey. Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet (2019).

36. Hughes BB, Hanna T, McNeil K, Bohl DK, Moyer J.D. Pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals in a World Reshaped by COVID-19. Denver, CO; New York, NY: Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures and United Nations Development Programme (2021).

38. Kleinert S, Horton R. Rethinking and reframing obesity. Lancet. (2015) 385:2326–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60163-5

39. Garside R, Pearson M, Hunt H, Moxham T, Anderson R. Identifying the Key Elements and Interactions of a Whole System Approach to Obesity Prevention. Exeter: Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG) (2010).

40. Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. (2019) 393:447–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

41. World Health Organisation Europe. Digital Food Environments: Factsheet 2021. (2021). Available online at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/publications/2021/digital-food-environments-factsheet-2021

42. Bonyhardy NW, Shane E. The Right Thing To Do: Menulog's Move to Employ Couriers Ups Pressure on Gig Economy. Sydney Morning Herald (2021).

43. Corlett E. New Zealand Uber Drivers Launch Class Action Against Ride Share Company. Wellington: The Guardian (2021).

44. Moreno C, Allam Z, Chabaud D, Gall C, Pratlong F. Introducing the “15-minute city”: sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities. (2021) 4:93–111. doi: 10.3390/smartcities4010006

45. Willsher K. Paris Mayor Unveils '15-Minute City' Plan in Re-election Campaign. Paris: The Guardian. (2020).

46. Grodach C, Kamruzzaman L, Harper L. 20-Minute Neighbourhood - Living Locally Research. Melbourne, VIC: Monash University (2019).

47. Weng M, Ding N, Li J, Jin X, Xiao H, Zhi-ming H, et al. The 15-minute walkable neighborhoods: measurement, social inequalities and implications for building healthy communities in urban China. J Transport Health. (2019) 13:259–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2019.05.005

48. Land Transport Authority Singapore. Land Transport Master Plan 2040. Singapore: Land Transport Authority (2020).

49. City of Portland. 20-Minute Neighbourhoods Portland, United States of America. (2021). Available online at: https://www.portlandonline.com/portlandplan/index.cfm?a=288098&c=52256

50. Guzman LA, Arellana J, Oviedo D, Moncada Aristizábal CA. COVID-19, activity and mobility patterns in Bogotá. Are we ready for a '15-minute city'? Travel Behav Soc. (2021) 24:245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tbs.2021.04.008

51. World Health Organisation. Monitoring Food and Beverage Marketing to Children via Television and the Internet. A Proposed Tool for the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2016).

52. Sweney M. UK to Ban Junk Food Advertising Online and Before 9pm on TV from 2023. London: The Guardian (2021).

53. Wyse R, Delaney T, Stacey F, Zoetemeyer R, Lecathelinais C, Lamont H, et al. Effectiveness of a multistrategy behavioral intervention to increase the nutritional quality of primary school students' web-based canteen lunch orders (click & crunch): cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e26054. doi: 10.2196/26054

54. Coles J. Calorie-Labelled Menus Set for Cafes, Restaurants and Takeaways in England. Available online at: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/calorie-labelled-menus-set-cafs-24095206 (accessed May 12, 2021).

55. Global Ecolabelling Network. What is Ecolabelling? (2021). Available online at: https://globalecolabelling.net/what-is-eco-labelling/#:~:text=Ecolabelling%20is%20a%20voluntary%20method,preferable%20within%20a%20specific%20category

56. Potter C, Bastounis A, Hartmann-Boyce J, Stewart C, Frie K, Tudor K, et al. The effects of environmental sustainability labels on selection, purchase, and consumption of food and drink products: a systematic review. Environ Behav. (2021) 53:891–925. doi: 10.1177/0013916521995473

57. Coelho PM, Corona B, ten Klooster R, Worrell E. Sustainability of reusable packaging-Current situation and trends. Resour Conserv Recycl X. (2020) 6:100037. doi: 10.1016/j.rcrx.2020.100037

58. Halloran A, Faiz M, Chatterjee S, Clough I, Rippin H, Farrand C, et al. The cost of convenience: potential linkages between noncommunicable diseases and meal delivery apps. Lancet Region Health Eur. (2022) 12:100293. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100293

59. Fanzo J, Haddad L, McLaren R, Marshall Q, Davis C, Herforth A, et al. The Food Systems Dashboard is a new tool to inform better food policy. Nature Food. (2020) 1:243–6. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0077-y

60. INFORMAS G, Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University. The The University of Queensland, University of Wollongong. The The University of Newcastle, The The George Institute for Global Health, Obesity Policy Coalition, VicHealth. Australia's Food Environment Dashboard. (2021). Available online at: https://foodenvironmentdashboard.com.au/

Keywords: online food delivery, sustainable development goals, global health, public health, systems approach

Citation: Jia SS, Gibson AA, Ding D, Allman-Farinelli M, Phongsavan P, Redfern J and Partridge SR (2022) Perspective: Are Online Food Delivery Services Emerging as Another Obstacle to Achieving the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals? Front. Nutr. 9:858475. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.858475

Received: 20 January 2022; Accepted: 07 February 2022;

Published: 03 March 2022.

Edited by:

Maha Hoteit, Lebanese University, LebanonReviewed by:

Jana Jabbour, Modern University for Business and Science, LebanonCopyright © 2022 Jia, Gibson, Ding, Allman-Farinelli, Phongsavan, Redfern and Partridge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Si Si Jia, c2lzaS5qaWFAc3lkbmV5LmVkdS5hdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.