- 1Department of Health Services and Hospital Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administration, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 2Health Economics Research Group, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 3Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, NSW, Australia

- 4Institute of Health Economics, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 5Geriatric Medicine Research, Nova Scotia Health Authority, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 6School of Health Administration, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Background: Saudi Arabia is the fifth largest consumer of calories from sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in the world. However, there is a knowledge gap to understand factors that could potentially impact SSB consumption in Saudi Arabia. This study is aimed to examine the determinants of SSBs in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: The participants of this study were from the Saudi Health Interview Survey (SHIS) of 2013, recruited from all regions of Saudi Arabia. Data of a total of 10,118 survey respondents were utilized in this study who were aged 15 years and older. Our study used two binary outcome variables: weekly SSB consumption (no vs. any amount) and daily SSB consumption (non-daily vs. daily). After adjusting for survey weights, multivariate logistic regression models were applied to assess the association of SSB consumption and study variables.

Results: About 71% of the respondents consumed SSB at least one time weekly. The higher likelihood of SSB consumption was reported among men, young age group (25–34 years), people with lower income (<3,000 SR), current smokers, frequent fast-food consumers, and individuals watching television for longer hours (≥4 h). Daily vegetable intake reduced the likelihood of SSB consumption by more than one-third.

Conclusions: Three out of four individuals aged 15 years and over in Saudi Arabia consume SSB at least one time weekly. A better understanding of the relationship between SSB consumption and demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors is necessary for the reduction of SSB consumption. The findings of this study have established essential population-based evidence to inform public health efforts to adopt effective strategies to reduce the consumption of SSB in Saudi Arabia. Interventions directed toward education on the adverse health effect associated with SSB intake are needed.

Introduction

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the most widely consumed caloric beverage (1–3). They contain a high amount of added sugar, calorie, and energy and are poor in nutritional value (3–5). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), SSB is defined as “all types of beverages containing free sugars, and these include carbonated or non-carbonated soft drinks, fruit/vegetable juices and drinks, liquid and powder concentrates, flavored water, energy, and sports drinks, ready-to-drink tea, ready-to-drink coffee, and flavored milk drinks” (6). Reducing SSB consumption is recommended by the WHO (7) and documented in the 2015–2020 dietary guidelines for people of the United States of America (USA) (8). SSBs are the largest source of added sugar and a key source of energy intake among both children and adults in the USA (9). Globally, excess sugar consumption has become an important public health concern (10).

SSB consumption levels among adults vary widely across countries. For instance, in the USA, a decreased trend in consumption of SSB was found between 1999 and 2010 in both youth and adults (11). In Australia, however, in 2011–12, national data indicated that 50% of Australians drank SSB on the day before the interview (12). SSB intake is particularly concerning among Saudi adults. According to Banajiba and Mahboub, Saudi Arabia is considered one of the biggest consumers of sugary drinks in the middle-eastern region (13). The country also has high prevalence rates of overweight, obesity, and diabetes. A growing amount of evidence from experimental trials and observational studies showed that regular SSB intake resulted in excess weight gain and might contribute to obesity and type 2 diabetes (9). Evidence also indicated that reducing the consumption of SSB will have a substantial impact on the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases, such as diabetes (9).

A number of studies explored determinants of high SSB consumption among adults. Those studies reported that gender, age, socioeconomic status, marital status, and educational level were positively associated with SSB consumption (14–17). The majority of prior research also showed that an unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., poor-quality diet, sedentary behaviors, and smoking) was associated with higher SSB consumption intake. A poor-quality diet, specifically, lower intake of fruits and vegetables, infrequent breakfast consumption, high intake of meat, fast and fried food consumption (16, 18–20), and sedentary behaviors, such as prolonged television watching and lack of physical activity, were linked to more SSB intake (14, 16, 21). Other determinants, such as inadequate household food supply, was also associated with higher SSB consumption (22).

Many studies assessing the association between SSB intake and overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, and depressive symptoms found a positive association, while other studies found none (2, 23–26). Thus, it is imperative to understand the determinants influencing the consumption of SSB to inform future intervention development. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the determinants of SSB in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) using national survey data. This study has two objectives: (1) to determine the prevalence of SSB consumption and (2) to examine the association between SSB consumption and an array of demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors. By understanding the determinants of SSB consumption, strategies aimed at curbing intake can be crafted to guide decisions effectively. This is of particular importance when designing strategies geared toward high-risk groups. The findings of this study can also help raise awareness about health problems that are linked to excessive consumption of added sugars in beverages, which might prompt behavioral intention toward reducing sugary drinks intake.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

This study obtained secondary data from the 2013 Saudi Health Interview Survey (SHIS) for empirical analysis. The SHIS was representative of the Saudi population aged 15 years and older in 2013 (27). The Saudi Ministry of Health (SMOH) implemented this survey across all the regions of Saudi Arabia between April and June 2013. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington provided technical support to the SMOH for conducting the SHIS. The Government of the KSA provided financial assistance to complete the data collection. This survey was designed following the USA's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The goal of the SHIS was to collect information about socioeconomic, demographic, health characteristics, the use of health services, and health-related behavior of the Saudi population. Trained interviewers collected data using a structured questionnaire in a face-to-face interview, and DatStat software was used in data collection (28). The reliability of data collection was ensured by giving real-time feedback to the interviewers and supervisors in the field.

Survey Design

The SHIS was a cross-sectional household survey, where participants were selected through a multistage stratified random sample technique for ensuring the representativeness of the Saudi population. Thirteen administrative regions of the KSA formulated the strata of this survey. Primary sampling units (PSUs) of the survey were selected based on enumeration household units or clusters (on average, each cluster has about 140 households) from the Census Bureau of Saudi Arabia (28). PSUs were randomly selected according to the probability proportional to size sampling approach. This process randomly selected 12,000 households from all these PSUs (14 households in each PSU). Further descriptions of the sampling methods and data collection procedures are available in prior publications (27, 29). Sample weights were integrated with the datasets for statistical analyses.

Study Sample

The response rate was about 90% in this survey (28), which led to interviewing 10,735 respondents aged ≥15 years. We limited our study to only participants with no missing data on SSB consumption. About 3.3% of the observations had no data on SSB consumption. We discarded observations with missing data on SSB consumption. This restriction gave us an analytic sample of 10,118 individuals. Out of 10,118 individuals, 5,028 (49.7%) participants were men and 5,090 (51.3%) participants were women.

Outcome Variables

To measure the consumption of SSB, respondents in the SHIS were asked the following questions: (1) In a typical week, how many days do you drink regular soda or pop that contains sugar, sweetened iced teas, sports drinks, or fruit drinks? (Do not include diet soda, sugar-free drinks, or 100% pure fruit juice) and (2) How many servings of SSBs did you drink on one of those days? A binary outcome variable was constructed based on these questions, which equals 1 if the study participants consume any SSB in a typical week and zero otherwise. Following the previous literature (30), a second outcome variable was constructed as regular/daily consumers of SSB reported consuming at least one SSB every day in the past week prior to the survey.

Explanatory Variables

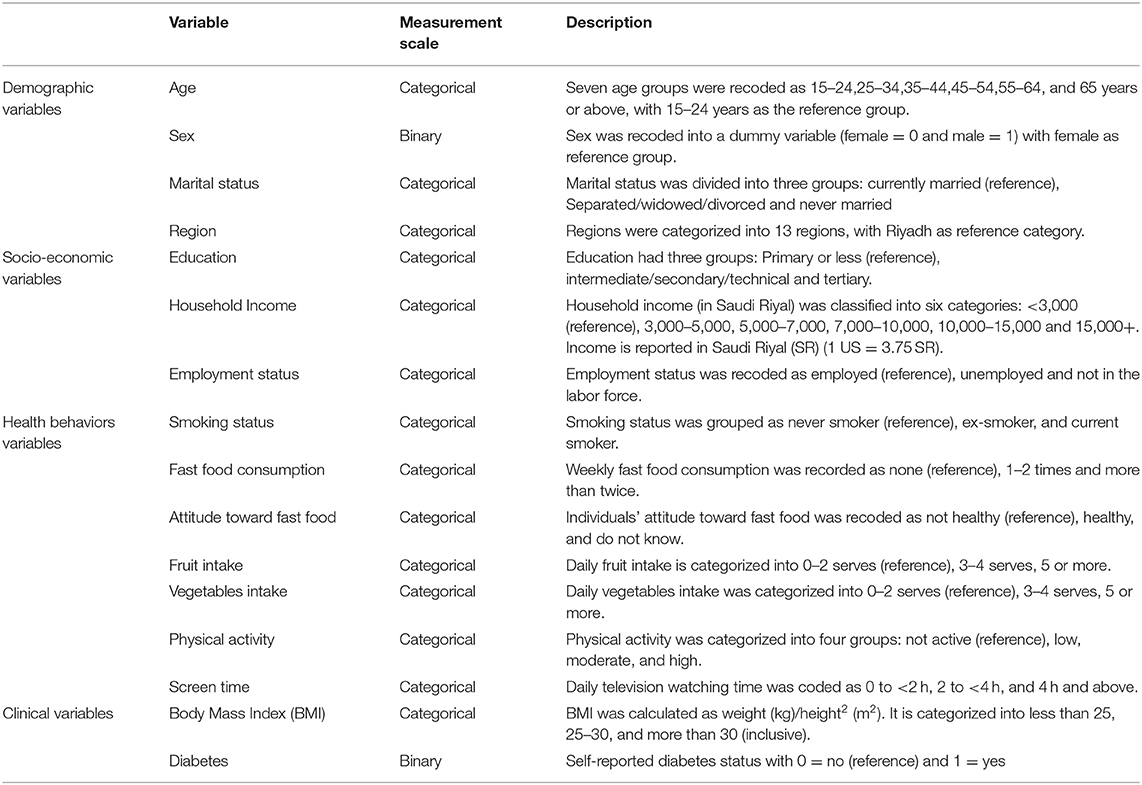

Previous studies in different contexts found a wide range of variables that could be correlated with the consumption of SSB (17, 31, 32). This study followed previous literature to select the predictors of SSB consumption (17, 31, 32). These included i) demographic factors, such as sex and age, ii) socioeconomic factors, such as household income and education, iii) behavioral risk factors, such as physical activity, fast food consumption, smoking status, and iv) clinical factors, such as body mass index (BMI), diabetes, and co-morbidities. Table 1 provides details on the description and construction of the variables. Age was categorized into seven groups following the SHIS (33). Education was classified into three groups. Daily fruit and vegetable intake was categorized into three groups: 0–2 serves, 3–4 serves, and 5 or more serves (22). Smoking status was categorized into three groups: never smoker, ex-smoker, and current smoker (17). Physical activity was assessed by asking the respondents about the time he or she spent doing different types of activities in a typical week. These activities included vigorous-intensity activity (large increases in breathing or heart rate), moderate-intensity activity (small increases in breathing or heart rate), walking to work and other places, and recreational activities (e.g., sports and fitness training). Physical activity was categorized into four groups: not active, low, moderate, and high (30, 33). A total of fewer than 150, 150–450, and more than 450 min of moderate to intense activity each week were considered low, moderate, and high levels of physical activity, respectively (33). BMI was categorized by following the WHO guideline (34).

Statistical Methods

This study used Stata version 16.1 for Windows (Stata Corp. 2017, Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX, USA: Stata Corp LLC) to implement all the statistical analyses. A total number of people who consumed any SSB (in a typical week) was divided by the total sample size to estimate the prevalence of SSB consumption. Descriptive analyses were undertaken to investigate the association between the prevalence of SSB consumption and respondents' characteristics. This association was measured using Pearson's chi-square test (35). We examined the same relationships through multivariate regression analysis, controlling for the effect of other variables. Logistic regression models were used in the multivariate analysis. The findings were presented using adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% Confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values.

We also conducted a subgroup (male vs. female and 15–24 years age group vs. 25+ years age group) analysis. Data were weighted by the inverse of the person's probability of selection and the response rate in the regions of the KSA. We used the “svy” prefix command of the Stata software to account for the statistical design of the survey (weighting, clustering, and stratification). Multiple imputation method was implemented using “mi” command in Stata to impute missing data on independent variables. A significance level of p <0.05 was applied to measure the association in the multivariate models.

Ethics Statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the SMOH reviewed and granted ethics approval for the SHIS (36). Informed consent was obtained from the participants to be included in the survey. Data were fully anonymized by the SMOH. The authors received de-identified data for this study after complying with the regulations of secondary analysis. There was no possibility to identify people using the current data. Therefore, separate ethics approval was not required for the current study.

Results

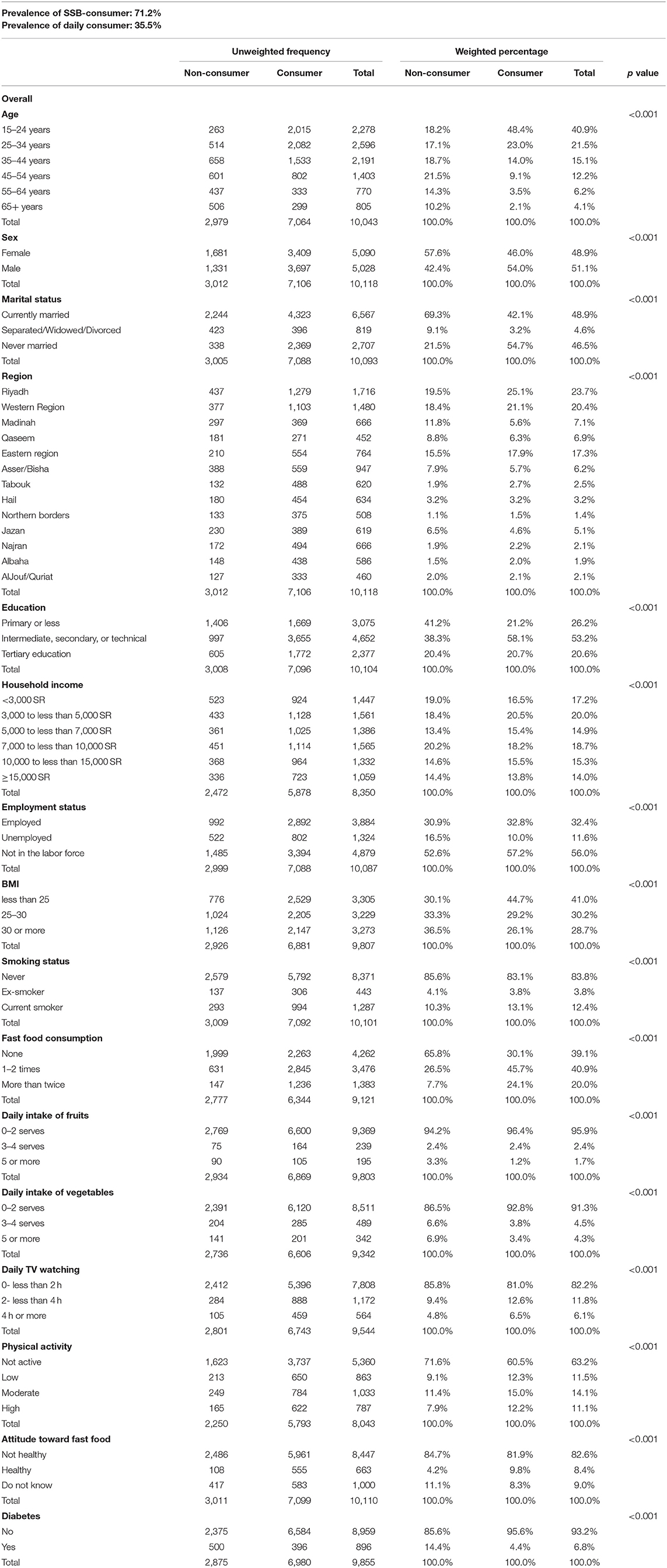

Table 2 presents demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and lifestyle risk factors and attitude and knowledge characteristics of the study participants by SSB consumption status. About 71% of respondents consumed SSB at least once in a typical week. The prevalence of daily consumption (i.e., regular consumer) of SSB was about 36% among the consumers. Overall, the study sample was almost equally distributed between men (51.1%) and women (48.9%). SSB consumption was significantly correlated with all the variables shown in Table 2. About 54% of the consumers (consume SSB at least once a week) were men.

A linear trend was observed for age with each categorical decrease in consumption. The highest percentage (48.4%) of the SSB consumer belonged to the age group 15–24 years, whereas the proportion was the lowest (2.1%) for the age group 65 years and above. The consumers of SSB mostly resided in Riyadh (25.1%), followed by the Western Region (21.1%) and the Eastern Region (17.9%). Among the SSB consumers, about 58% of respondents had an education level of intermediate, secondary, or technical, while about 21% of the consumers had tertiary education. The highest proportion (20.5%) of consumers belonged to the income group of 3,000–5,000 Saudi Riyal (SR). SSB consumption was highly prevalent among participants who were not in the labor force (57.2%).

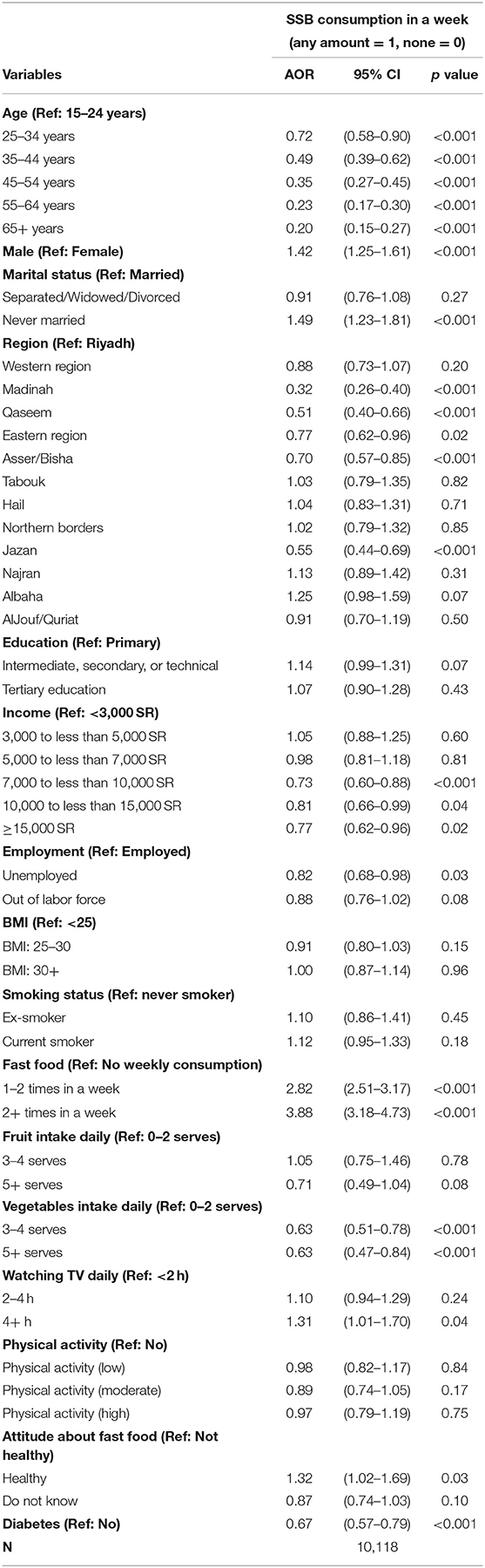

Table 3 shows the association of weekly SSB consumption with study variables in terms of AORs. The likelihood of consuming SSB per week was decreased as the respondent's age increased. For example, the odd of weekly SSB intake was about 80% lower among the oldest group (65 years and above) than the youngest groups (15–24 years). The likelihood of weekly SSB consumption was significantly higher among men (AOR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.25–1.61). Compared with residents of the Riyadh region, respondents living in other regions (except Al Bahah) had significantly lower odds of SSB consumption per week. Among the socioeconomic variables, income and employment status were significantly associated with the probability of weekly consumption of SSB. The likelihood of weekly SSB consumption was lower (AOR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.62–0.96) among individuals earning more than 15,000 SR compared to individuals earning an income of less than 3,000 SR.

Table 3 also illustrates that the likelihood of SSB consumption in a typical week is about four times higher among participants who reported consuming fast food two times or more in a week. Participants who had more than three serves of vegetables daily were 37% less likely to consume SSB. Watching television for more than 4 h every day was associated with a higher likelihood of SSB consumption (AOR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.01–1.70). Stratification of the sample between men and women and different age groups did not significantly change the results on the correlates of weekly SSB consumption (Supplementary Tables S1, S2).

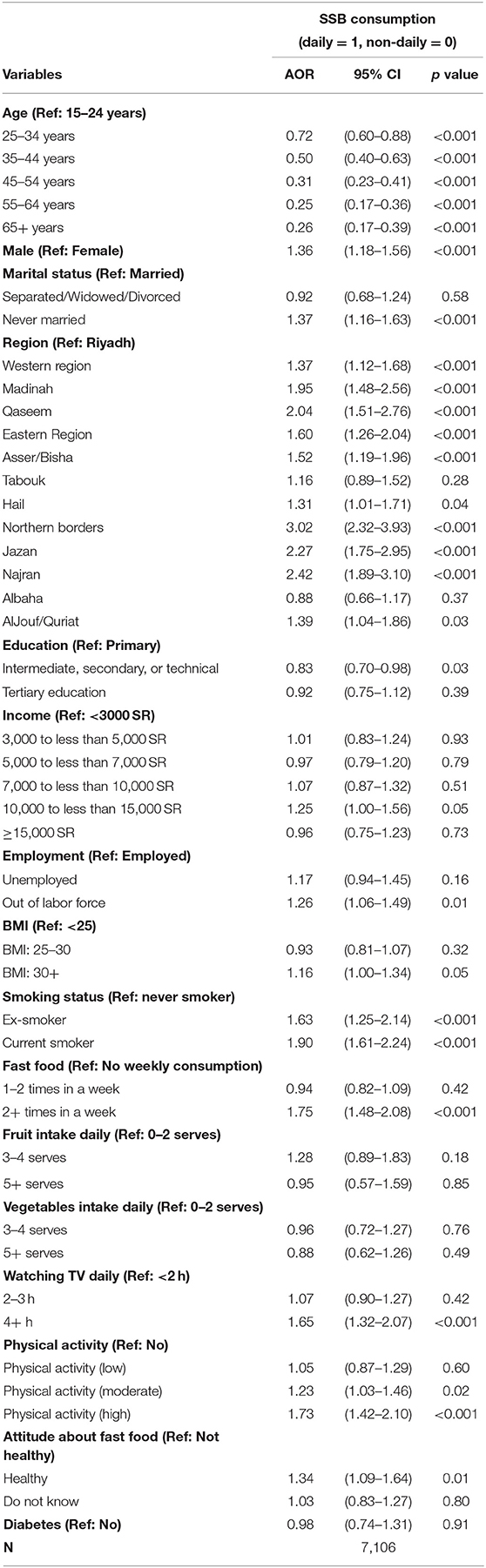

Associations of daily SSB consumption and study factors among SSB consumers are presented in Table 4. Our results showed that the odds of daily SSB consumption were decreased with age. Men were more likely to consume SSB daily than women (AOR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.18–1.56). Individuals living in different regions (except Al Bahah) of KSA had significantly lower odds of daily SSB consumption compared to people living in Riyadh. Respondents with intermediate, secondary, or technical education levels had a lower likelihood of consuming SSB daily than those with a primary level education (AOR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.70–0.98). Individuals with an income of 10,000 to <15,000 SR had a higher likelihood of consuming SSB daily than individuals with an income of less than 3,000 SR (AOR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.00–1.56). Respondents who were out of the labor force had higher odds of consuming SSB daily compared to employed respondents (AOR: 1.26 95% CI: 1.06–1.49).

Table 4. Association of daily vs. non-daily sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) consumption and study variables among SSB consumers.

We found that individuals with BMI over 30 were more likely to drink SSB daily compared to those with BMI less than 30 (AOR: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.00–1.34). Compared to individuals who never smoked, both previous and current smokers were more likely to consume SSB daily (AOR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.25–2.14 and AOR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.61–2.24). Individuals who consumed fast food more than two times a week were 75% more likely to report daily SSB consumption. Watching television for 4 h or more was significantly associated with a higher intake of SSB daily (AOR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.32–2.07).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to highlight the determinants of SSB consumption in the KSA using data from nationally representative survey. The main strength of our study is to include a wide range of explanatory variables in the analysis. Our findings demonstrate that sedentary behaviors, such as frequently watching television and fast food consumption, were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of SSB intake. On the other hand, healthy eating behaviors decreased the likelihood of SSB consumption. We also found that younger groups were the most vulnerable among all age groups for SSB consumption. In addition, richer people had a lower likelihood of SSB consumption. However, there was no significant association between education and physical activity with a greater likelihood of SSB consumption.

Our findings demonstrated that demographic, socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical factors were associated with SSB consumption. Approximately 71% of adults had consumed SSB in any given week, with 35.5% of adults consuming these drinks regularly, on a daily basis. Our findings followed the results from several earlier population-based studies in Saudi Arabia and Australia, showing that SSB consumption was higher among young adults, men, and low-income households (17, 37, 38). Although our study did not observe any association between SSB intake and adult educational attainment, existing evidence indicated that health literacy (i.e., individual capacity to comprehend basic health information required to make conscious health decisions) was linked to lower SSB intake (39). Women had significantly higher health literacy scores than men (21). Thus, low levels of health literacy could partially explain the positive relation between SSB intake among men in this study. This underscores the need to increase health literacy and provide clear and understandable health information among this population (17). The reason that lower-income individuals in this study were more likely to consume SSB was not clear and warranted further investigation.

Our findings indicate a linkage between behavioral factors and SSB consumption. In line with other studies, eating fast food was positively associated with SSB consumption (22, 38, 40, 41). Adults who had consumed fast food one time or two times a week had nearly three times the odds of being SSB consumers, and more frequent fast-food consumers (more than two times a week) had nearly four times the odds. This is particularly important given that several studies in Saudi Arabia indicated that Saudi children, adolescents, and adults are great consumers of fast food (42–45). The association between consuming fast food and takeaway meals and higher consumption of SSB have been well documented (17, 41). In this study, fast food was perceived as a “healthy food option” among this study population, implying that these adults might perceive SSB as somewhat “healthy.” This finding is critical given that adults with such perceptions are 30% more likely to be consumers of SSB in any given week or day. According to Miller et al. (17), Australian adults perceive SSB drinks as normal due to the availability, affordability, and promotion of these drinks. Taken together, strategies aimed at shaping adults' perception of fast food and SSB are needed. Evidence showed that on-pack health warning labels (46, 47) helped to promote an understanding of the potential risks of consuming SSB and decrease SSB sales (48).

Lack of knowledge as well about the content of SSB drinks might contribute to higher SSB intake (17). A recent study in Saudi Arabia showed that adults' awareness of the calorie content of SSB was related to lower SSB intake (49). Therefore, increasing awareness of the potential risks of fast food and SSB is imperative and could be the first step toward curbing both intakes (38). Although our analysis did not find a significant association between consumption of SSB and daily consumption of fruits, daily consumption of vegetables was positively associated. SSB consumption was higher among adults who consumed less than one serving per day of vegetables compared with those who consumed three or more serves per day. Our results showed that there was a specific eating behavior that correlated with SSB intake. A less healthy eating pattern is associated with an unhealthy beverage pattern (40). For instance, consumers of SSB are less likely to adhere to a prudent dietary pattern and are more likely to adhere to a fast food pattern (50).

In this study, we also observed that sedentary behavior, such as television viewing for long hours (more than 4 h a day), was associated with a greater likelihood of SSB consumption. Similar findings were found among both children and adolescents in other studies (14, 51, 52). The association between smoking and SSB intake among Saudi adults found in this study was in line with other studies (53). For example, a study in China demonstrated a positive association between smoking and higher consumption of SSB (54).

Despite the findings that SSB cluster with poor dietary behavior, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle, assessed clinical factors, such as BMI, were not related to SSB consumption in this study. This is in contrast with other studies, indicating that SSB intake could lead to weight gain (2). It has been proposed that being obese or overweight could make an individual more receptive to health promotion messages on dietary behaviors (30). This could also be valid among adults with diabetes. In the present study, people with diabetes were less likely to consume SSB compared to their non-diabetic counterparts. A USA study on the consumption of SSB among adults with type 2 diabetes found that 45% of adults with diabetes consumed SSB, consuming 202 calories and 47 g of sugar. However, adults with undiagnosed diabetes were significantly greater to have a higher SSB intake than adults with diabetes (1).

Further research is needed to assess changes in socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical determinates of SSB intake among Saudi adults, following the implementation of the 50% excise tax on carbonated beverages in the country (55). Since the excise tax was promoted as an effective strategy for reducing the consumption of SSB, identifying determinants could be useful in the provision of customized population-based health interventions aimed at discouraging the consumption of SSB. Future studies should also monitor patterns of consumption among Saudi young, men, and lower-income individuals.

The analysis of this study has some limitations. The design of the study was cross-sectional. Therefore, it was not possible to draw causal conclusions from the observed significant relationships between outcome measures and their predictors. Another limitation was the use of self-reported consumption measure, which counted on the remembrance of participants without supplementary signaling to help recall. This problem might lead to an underestimated SSB consumption compared to an evaluation applying 24 h recall interview approach. Furthermore, this study could not compare the prevalence of SSB consumption between respondents and non-respondents. Due to the lack of data, this study could not consider energy intake while assessing the BMI and SSB consumption association.

Conclusions

The results of nationally representative data demonstrated that socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical factors are strong determinants of consumption of SSB among Saudi adults. The findings of this study have established essential population-based evidence to inform public health efforts to adopt effective strategies to reduce the consumption of SSB in the country. Interventions directed toward education on the adverse health effects of these drinks are needed to reduce SSB intake of adults.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy, confidentiality and other restrictions. Access to data can be gained through the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia.

Ethics Statement

This paper does not require ethical approval because we used a secondary data. Furthermore, the data is de-identified. The outcomes of the analysis does not allow re-identification and the use of data cannot result in any damage or distress.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Grant Number G: 863-120-1441. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge, with thank, the DSR for its technical and financial support.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.744116/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bleich SN, Wang YC. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. (2011) 34:551–5. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1687

2. Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. (2013) 98:1084–102. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362

3. Hu FB, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol Behav. (2010) 100:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.036

4. Bermudez OI, Gao X. Greater consumption of sweetened beverages and added sugars is associated with obesity among US young adults. Ann Nutr Metab. (2010) 57:211–8. doi: 10.1159/000321542

5. Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. (2006) 84:274–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.2.274

6. World Health Organization. Taxes on sugary drinks: Why do it? (2017). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260253 (accessed December 10, 2021).

7. World Health Organization. Reducing free sugars intake in children and adults (2021). Available online at: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/guidance_summaries/sugars_intake/en/ (accessed December 10, 2021).

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. (2015). Available online at: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guideline (accessed December 10, 2021)

9. Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. (2013) 14:606–19. doi: 10.1111/obr.12040

10. World Health Organization. Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. (2015). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549028 (accessed December 05, 2021).

11. Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, Ogden CL. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am J Clin Nutr. (2013) 98:180–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.057943

12. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results–Foods and Nutrients, 2011-12. (2014). Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-nutrition-first-results-foods-and-nutrients/latest-release. (accessed December 10, 2021).

13. Benajiba N, Mahboub SM. Consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks among saudi adults: assessing patterns and identifying influencing factors using principal component analysis. Pakistan J Nutr. (2019) 18:401–7. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2019.401.407

14. Rehm CD, Matte TD, Van Wye G, Young C, Frieden TR. Demographic and behavioral factors associated with daily sugar-sweetened soda consumption in New York City adults. J Urban Health. (2008) 85:375–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9269-8

15. Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988–1994 to 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. (2008) 89:372–81. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883

16. Mathur MR, Nagrath D, Malhotra J, Mishra VK. Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among indian adults: findings from the National Family Health Survey-4. Indian J Community Med. (2020) 45:60. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_349_19

17. Miller C, Wakefield M, Braunack-Mayer A, Roder D, O'Dea K, Ettridge K, et al. Who drinks sugar sweetened beverages and juice? An Australian population study of behaviour, awareness and attitudes. BMC Obesity. (2019) 6:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40608-018-0224-2

18. Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. (2005) 365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0

19. French SA, Harnack L, Jeffery RW. Fast food restaurant use among women in the Pound of Prevention study: dietary, behavioral and demographic correlates. Int J Obes. (2000) 24:1353–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801429

20. French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes. (2001) 25:1823–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820

21. Mendy VL, Vargas R, Payton M, Cannon-Smith G. Association between consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and sociodemographic characteristics among mississippi Adults. Prev Chronic Dis. (2017) 14. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.170268

22. Sharkey J, Johnson C, Dean W. Less-healthy eating behaviors have a greater association with a high level of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among rural adults than among urban adults. Food Nutr Res. (2011) 55:5819. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v55i0.5819

23. Forshee RA, Anderson PA, Storey ML. Sugar-sweetened beverages and body mass index in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. (2008) 87:1662–71. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1662

24. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. (2010) 121:1356–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185

25. Yu B, He H, Zhang Q, Wu H, Du H, Liu L, et al. Soft drink consumption is associated with depressive symptoms among adults in China. J Affect Disord. (2015) 172:422–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.026

26. Keller A, Heitmann BL, Olsen N. Sugar-sweetened beverages, vascular risk factors and events: a systematic literature review. Public Health Nutr. (2015) 18:1145–54. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002122

27. El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, Kravitz H, AlMazroa MA, Al Saeedi M, et al. Access and barriers to healthcare in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013: findings from a national multistage survey. BMJ Open. (2015) 5. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007801

28. Ministry of Health Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation University University of Washington. Saudi Health Interview Survey Results (2013). Available online at: https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/Projects/KSA/Saudi-Health-Interview-Survey-Results.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020)

29. Al-Sumaih I, Johnston B, Donnelly M, O'Neill C. The relationship between obesity, diabetes, hypertension and vitamin D deficiency among Saudi Arabians aged 15 and over: results from the Saudi health interview survey. BMC Endocr Disord. (2020) 20:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12902-020-00562-z

30. Mullie P, Aerenhouts D, Clarys P. Demographic, socioeconomic and nutritional determinants of daily versus non-daily sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverage consumption. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2012) 66:150–5. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.138

31. Tasevska N, DeLia D, Lorts C, Yedidia M, Ohri-Vachaspati P. Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among low-income children: are there differences by race/ethnicity, age, and sex? J Acad Nutr Diet. (2017) 117:1900–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.03.013

32. Thurber KA, Bagheri N, Banwell C. Social determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the longitudinal study of indigenous children. Family Matters. (2014) 95:51. doi: 10.3316/ielapa.837561874196294

33. Ministry of Health Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Health Interview Survey Results. (2013). Available online at: http://www.healthdata.org/ksa/projects/saudi-health-interview-survey (accessed June 05, 2021).

34. World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. (2000). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42330 (accessed December 05, 2021).

35. Pearson K. X. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. London, Edinbur Dublin Philosoph Mag J Sci. (1900) 50:157–75. doi: 10.1080/14786440009463897

36. Al-Hanawi MK, Hashmi R, Almubark S, Qattan A, Pulok MH. Socioeconomic inequalities in uptake of breast cancer screening among saudi women: a cross-sectional analysis of a national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2056. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062056

37. Moradi-Lakeh M, El Bcheraoui C, Afshin A, Daoud F, AlMazroa MA, Al Saeedi M, et al. Diet in Saudi Arabia: findings from a nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:1075–81. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016003141

38. Pollard CM, Meng X, Hendrie GA, Hendrie D, Sullivan D, Pratt IS, et al. Obesity, socio-demographic and attitudinal factors associated with sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: Australian evidence. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2016) 40:71–7. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12482

39. Zoellner J, You W, Connell C, Smith-Ray RL, Allen K, Tucker KL, et al. Health literacy is associated with healthy eating index scores and sugar-sweetened beverage intake: findings from the rural Lower Mississippi Delta. J Am Diet Assoc. (2011) 111:1012–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.010

40. Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Adults with healthier dietary patterns have healthier beverage patterns. J Nutr. (2006) 136:2901–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.11.2901

41. Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Laska MN, Story M. Young adults and eating away from home: associations with dietary intake patterns and weight status differ by choice of restaurant. J Am Diet Assoc. (2011) 111:1696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.007

42. Abou Zeid A, Hifnawy T, Abdel Fattah M. Health habits and behaviour of adolescent schoolchildren, Taif, Saudi Arabia. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health J. (2009) 15:1525–34. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/117793

43. Washi SA, Ageib MB. Poor diet quality and food habits are related to impaired nutritional status in 13-to 18-year-old adolescents in Jeddah. Nutr Res. (2010) 30:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2010.07.002

44. Ibrahim NK, Mahnashi M, Al-Dhaheri A, Al-Zahrani B, Al-Wadie E, Aljabri M, et al. Risk factors of coronary heart disease among medical students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:411. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-411

45. Al-Rethaiaa AS, Fahmy A-EA, Al-Shwaiyat NM. Obesity and eating habits among college students in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Nutr J. (2010) 9:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-39

46. Acton RB, Hammond D. The impact of price and nutrition labelling on sugary drink purchases: results from an experimental marketplace study. Appetite. (2018) 121:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.089

47. VanEpps EM, Roberto CA. The influence of sugar-sweetened beverage warnings: a randomized trial of adolescents' choices and beliefs. Am J Prev Med. (2016) 51:664–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.010

48. Farley TA, Halper HS, Carlin AM, Emmerson KM, Foster KN, Fertig AR. Mass media campaign to reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in a rural area of the United States. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:989–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303750

49. Al Otaibi HH. Sugar Sweetened Beverages Consumption Behavior and Knowledge among University Students in Saudi Arabia. J Econ Bus Manage. (2017) 5:173–6. doi: 10.18178/joebm.2017.5.4.507

50. Piernas C, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Gordon-Larsen P, Popkin BM. Low-calorie-and calorie-sweetened beverages: diet quality, food intake, and purchase patterns of US household consumers. Am J Clin Nutr. (2014) 99:567–77. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.072132

51. Grimm GC, Harnack L, Story M. Factors associated with soft drink consumption in school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. (2004) 104:1244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.05.206

52. Scully M, Morley B, Niven P, Crawford D, Pratt IS, Wakefield M. Factors associated with high consumption of soft drinks among Australian secondary-school students. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:2340–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000118

53. Lana A, Lopez-Garcia E, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Consumption of soft drinks and health-related quality of life in the adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2015) 69:1226–32. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.103

54. Ko G, So W, Chow C, Wong P, Tong S, Hui S, et al. Risk associations of obesity with sugar-sweetened beverages and lifestyle factors in Chinese: the ‘Better Health for Better Hong Kong' health promotion campaign. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2010) 64:1386–92. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.181

Keywords: adults, Saudi Arabia (KSA), sugar-sweetened beverage, calories, fast food

Citation: Al-Hanawi MK, Ahmed MU, Alshareef N, Qattan AMN and Pulok MH (2022) Determinants of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Among the Saudi Adults: Findings From a Nationally Representative Survey. Front. Nutr. 9:744116. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.744116

Received: 21 September 2021; Accepted: 28 January 2022;

Published: 22 March 2022.

Edited by:

Giuseppe Grosso, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Emmanouella Magriplis, Agricultural University of Athens, GreeceVittorio Calabrese, University of Catania, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Al-Hanawi, Ahmed, Alshareef, Qattan and Pulok. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed Khaled Al-Hanawi, bWthbGhhbmF3aUBrYXUuZWR1LnNh

Mohammed Khaled Al-Hanawi

Mohammed Khaled Al-Hanawi Moin Uddin Ahmed

Moin Uddin Ahmed Noor Alshareef

Noor Alshareef Ameerah Mohammad Nour Qattan

Ameerah Mohammad Nour Qattan Mohammad Habibullah Pulok

Mohammad Habibullah Pulok