95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Nutr. , 02 February 2022

Sec. Clinical Nutrition

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.800990

Ravindran Vini1

Ravindran Vini1 Juberiya M. Azeez1

Juberiya M. Azeez1 Viji Remadevi1

Viji Remadevi1 T. R. Susmi1

T. R. Susmi1 R. S. Ayswarya1

R. S. Ayswarya1 Anjana Sasikumar Sujatha1

Anjana Sasikumar Sujatha1 Parvathy Muraleedharan2

Parvathy Muraleedharan2 Lakshmi Mohan Lathika1

Lakshmi Mohan Lathika1 Sreeja Sreeharshan1*

Sreeja Sreeharshan1*Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) have been used in hormone related disorders, and their role in clinical medicine is evolving. Tamoxifen and raloxifen are the most commonly used synthetic SERMs, and their long-term use are known to create side effects. Hence, efforts have been directed to identify molecules which could retain the beneficial effects of estrogen, at the same time produce minimal side effects. Urolithins, the products of colon microbiota from ellagitannin rich foodstuff, have immense health benefits and have been demonstrated to bind to estrogen receptors. This class of compounds holds promise as therapeutic and nutritional supplement in cardiovascular disorders, osteoporosis, muscle health, neurological disorders, and cancers of breast, endometrium, and prostate, or, in essence, most of the hormone/endocrine-dependent diseases. One of our findings from the past decade of research on SERMs and estrogen modulators, showed that pomegranate, one of the indirect but major sources of urolithins, can act as SERM. The prospect of urolithins to act as agonist, antagonist, or SERM will depend on its structure; the estrogen receptor conformational change, availability and abundance of co-activators/co-repressors in the target tissues, and also the presence of other estrogen receptor ligands. Given that, urolithins need to be carefully studied for its SERM activity considering the pleotropic action of estrogen receptors and its numerous roles in physiological systems. In this review, we unveil the possibility of urolithins as a potent SERM, which we are currently investigating, in the hormone dependent tissues.

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are non-steroidal compounds that bind to estrogen receptors and can act like estrogen or be a partial agonist or antagonist with mixed activity depending on the tissue it acts. Tamoxifen and raloxifen are the most commonly used SERMs in treating breast cancer, which is often observed to exert side effects in hormone dependent-tissues. Tamoxifen, for instance, though osteoprotective like estrogen (1, 2), is reported to increase the uterine weight, endometrial cancer, stroke, and pulmonary embolism (3). A drug that has protective effects in estrogen-dependent tissues and prevents its deleterious effects would serve as an ideal SERM (4). Overcoming the side effects of synthetic SERMs is highly coveted for treating ER-positive breast cancer and other hormone related disorders. Hence, there has been an extensive search for alternatives from plant-based molecules with structural and functional resemblance to estrogens such as phytoestrogens. These are present in soy, grains, vegetables, and berries and are often metabolized by microbiota to form compounds, with or without having an estrogen-like activity (5). Many times, these phytoestrogens are metabolized by gut microbiota, which often have a stronger activity attributed to their higher lipophilicity, leading to a better absorption, and a higher affinity with estrogen receptors (6). These metabolites can, in turn, modulate the gut microbiota rendering a bidirectional relationship (7, 8). For instance, S-equol derived from daidzein by an intestinal bacterial metabolism also displays a profile like that of the daidzein's, and is of clinical importance (6, 9). Notably, many of the phytoestrogens like genistein, coumestrol, and liquiritigenin display more affinity toward estrogen receptor β (ERβ) than to estrogen receptor α (ERα), but the implications and underpinnings of these differences remain elusive (10). It is probable that those tissues where ERβ is critical, such as ovary, prostate, lung, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems (CNSs) (11), might be more influenced by these compounds.

Pomegranate has been known to have extensive medicinal properties which have been attributed to its constituents, working individually or in combination (12, 13). We have also demonstrated that pomegranate can act as SERM (4). Pomegranate is rich in ellagitannins and ellagic acid, which is further metabolized to urolithins by a specific colon microbiota. Ellagitannins and ellagic acid are also found in certain berries and nuts like walnuts and pecans. However, there is lot of inter-individual variability in the presence and abundance of ellagic acid and urolithins in plasma, urine, and feces of the individuals consuming ellagitannin-rich food, which could be primarily due to the presence, absence, or abundance of some specific microbiota (14). Urolithin family, characterized by a chemical structure containing α-benzo-coumarin scaffold, majorly include Urolithin A (UA),Urolithin B (UB), Urolithin C (UC), Iso-Urolithin A (Iso-UA), the recently discovered Urolithin M7R, Urolithin CR, and Urolithin AR (15). The main metabolites found in plasma, tissues, and excreted in urine and feces include UA, UB, and Iso-UA, which are subsequently absorbed and metabolized into their corresponding phase II conjugates (glucuronides or sulfates) and can persist in the bloodstream up to 3–4 days after the intake (13). Urolithins are understood to be actively glucuronidated in the large intestinal enterocytes before entering the bloodstream. Their maximal concentrations in the plasma can reach up to 35 μM for glucuronide and 8-O-glucuronide, 0.745 μM for Iso-UA 3-O-glucuronide, and 7.3 μM for and urolithin B 3-O-glucuronide (16). Repeated consumption of ellagitannin-containing food products can significantly increase the concentration of these conjugates in urine (16). Among the urolithins, UA and its conjugates are found at the highest concentrations in human plasma ranging from 0.024 to 35 μM. Urolithins are detected in high concentrations in the colon and can also reach the systemic tissues such as the prostate and mammary gland (13). Direct supplementation with UA significantly increases plasma levels and provides more than six-fold exposure to UA vs. pomegranate juice (17).

Accumulating evidence suggests urolithins have extensive health benefits (18). It has been shown that urolithins have estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity (19) via competitive binding assays, proliferation assays (20), and transactivation assays (21), and is predicted to bind to ERα in a similar orientation as that of the estrogen (21). However, the conjugates of urolithins, which reach the breast tissue after the ellagitannin intake, apparently lack estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activity (22). The ellagic acid from which urolithins are derived have also been reported to exhibit estrogenic activity at low concentrations (10−7 to 10−9 M), via ERα, whereas it was a complete estrogen antagonist via ERβ (23), though another investigation demonstrates absence of any estrogenicity or antiestrogenic activity in ellagic acid (21). Notably, UA and UB have been known to inhibit aromatase (24) and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (25), which are the enzymes critical for estradiol synthesis. All these pointedly illustrate the ability of urolithins to have estrogenic/anti-estrogenic or SERM-like profile. Briefly, estrogenic chemicals are those that can directly activate or inhibit estrogen action or can indirectly modulate its action. These can act as endocrine disruptors, which are defined as “an exogenous agent that interferes with the production, release, transport, metabolism, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones in the body responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis and the regulation of developmental processes” (26). The SERMs are cornerstone strategy to treat breast cancers, infertility problems, postmenopausal problems like hot flashes, osteoporosis, and for hormone replacement therapy. Hence, this implies that it is highly beneficial if urolithins can be employed as SERMS or as estrogenic compounds, with minimum side effects. Of note, urolithins are considered safe according to toxicity studies (27, 28), and, most importantly, UA has been recently recognized by food drug administration (FDA, USA) as GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) for its use as an ingredient. In this review, we explore the prospect of urolithins to act as endocrine modulators/disruptors by consolidating and connecting the existing body of evidence that underpins the health benefits of urolithins in hormone-dependent tissues and propose that it can act as an estrogen agonist, or antagonist or as SERMs, and detail its potential to modulate the hormone related pathways. The following sections unfold the benefits of urolithins in tissues where estrogen has a remarkable role. This includes its anti-inflammatory potential, cardiovascular benefits, breast, endometrial and prostate cancer protection, bone, muscle, and cognitive health where estrogen receptors are abundant and play a pivotal role.

Right from the mode of delivery to the kind of feeding pattern, the environment and the dietary pattern mold the gut microbiota. The response to diet depends on the type of bacteria that inhabits the gut and also interaction of the host microbe. This process is cyclic and inter-dependent (29). Similarly, the nutritional availability and, hence, therapeutic, or preventive effect of a diet can vary with microbiome features and their abundance. The inter-individual variability in the presence and abundance of ellagitannins/urolithins in plasma and urine samples after consumption of ellagitannin rich food was suggestive of their microbial origin in colon. Speculations were put to rest when results from Cerda et al. (30) confirmed that urolithins and its types correlated with the type of the fecal bacteria. This affirmed the microbial origin of urolithins in humans and explains the difference in the therapeutic and nutritional effects of pomegranate and berries that have similar rich composition of ellagitannins. This discovery led to the active research in identification of the microorganisms which can convert ellagitannins/ellagic acid to different types of urolithins. Selma et al. identified intestinal bacterial species from human feces, namely, Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens and Gordonibacter pamelaeae (31), belonging to the family Eggerthellaceae, which transformed the ellagic acid into UC, and another strain CEBAS 4A4, belonging to a new genus from the same family, could produce Iso-UA (32) under anaerobic condition leading to the categorizing of individuals into three metabotypes, according to the gut microbiota composition (33). After ingestion of ellagitannin-rich food products, individuals without urolithins production belonged to metabotype 0, with UA production as the unique final product that fits into metabotype A, and UB and/or Iso-UA belongs to metabotype B (14, 18). Thus, this difference in microbiota composition would further influence the health benefits associated with ellagitannin-rich food (34). Notably, urolithins have been found in breast milk of mothers, who consume ellagitannin rich walnut, and it resembles Urolilithin metabotypes of the mothers as well (35). Investigations on how these bacteria can improve the metabolism of an ellagitannin-rich food, how would it further bring about health benefits, and an examination of its safety aspects are vital before considering them as a potential probiotic.

Ellagitannins and urolithins have antioxidant (36), anti-inflammatory (37–41), and immunomodulatory properties (42). Urolithins inhibit NF-kb in colon fibroblast (43), in osteoarthiritic models (44), and in rat primary chondrocytes (45), but whether they act via estrogen receptors or membrane receptors like estrogen do, is not studied estrogens (46) is not studied. The UA and its metabolites have been shown to be protective in cardiac health (47, 48). In vivo studies with streptozotocin-induced type-1 diabetes rats demonstrated that urolithins administration reduced the myocardial expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine fractalkine, thus, improving the cardiac performance (49). Furthermore, urolithin B-glucuronide (UB-glu) could counteract trimethylamine-N-oxide-induced cardiomyocyte damage (48). Direct consumption of pomegranate has also shown the beneficial effects in the cardiovascular health (50–53). In our earlier study, we found a reduction in low density lipopolysaccharide (LDL) in the Swiss-albino mice after consumption of methanolic extract of pomegranate (PME), which was induced upon ovariectomy when compared to sham control (4).

Estrogens exert anti-inflammatory activity via the receptors like ERα, ERβ, and GPR-30 that are present on cardiac cells encompassing cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, vascular endothelial, and smooth muscle cells (54), thus, being beneficial in cardiovascular diseases such as coronary heart disease, ventricular hypertrophy, atherosclerosis, etc., via nuclear or non-nuclear pathways (55, 56). The ERβ appears to have a substantial cardioprotective effect (54). However, whether the protective effects of the pomegranate components or of urolithins are caused by these receptors are not investigated. It would be worthwhile to unravel whether they show similar or varying profile and benefits in different categories such as in pre-, peri- and post-menopausal women, and whether pomegranate benefits correlate their metabotype and different hormonal phases in women.

Our previous research showed that methanolic extract of a pomegranate peel reduced breast cancer proliferation by binding to estrogen receptor without affecting uterine weight, unlike estradiol or tamoxifen (4). A plethora of evidence points to preventive possibilities of pomegranate in breast cancer at its various stages and processes of cell survival (12). We had also reported that the PME can inhibit the proliferation induced by endogenous SERM 27 hydroxycholesterol (57). From the findings so far, urolithins are active molecules, but its availability and type are dependent on the gut microbiota and, hence, the extract may have limitations in its applicability. For the first time, Larossa et al. demonstrated in 2005 that UA and UB can act as “enterophytoestrogens,” exhibiting estrogenic activity in a dose-dependent manner without antiproliferative or toxic effects. Urolithins in combination with estrogen showed antiproliferative activity and anti-estrogenic activity and thwarted the proliferative activity of estrogen in the cell line models of human breast. The competitive binding assay showed that UA had much higher affinity to both ERα and ERβ than UB. The UA had a slightly higher affinity toward ERα than ERβ, with half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values being at 0.40 and 0.75 μM. Skledar et al. (21) reported a comparatively higher half maximal effective concentration (EC50) value for ERα, i.e., 5.60 μM. However, the conjugated metabolites of urolithins lacked these activities (22, 58). Hence, it is speculated that the potential antiproliferative/cytotoxic, as well as estrogenic/antiestrogenic activities, in breast tissues would primarily depend on the metabolite formed in the specific tissues. It is also suggested that though conjugation may hinder the direct antiproliferative activity, there is a probability of a long-term tumor-senescent chemoprevention (22).

Urolithins have been documented to inhibit aromatase and proliferation of breast cancer cells stimulated by testosterone (24). Strikingly, UA and UB inhibit 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (17β-HSD1) (25), an enzyme involved in dihydrotestosterone (DHT) inactivation and in the conversion of inactive estrone (E1) to estradiol (E2), and, hence, critical for estradiol synthesis. Of note, high 17β-HSD1 mRNA expression in patients with breast cancer correlates with a weak prognosis for breast cancer, thus, enhancing the breast cancer proliferation and invasion (59). Additionally, urolithins inhibit androgen receptor (60). These results point to its ability to act as anti-estrogenic in breast cancer. The UA also suppresses hyper-activated transglutaminase TGM2 which is one of the novel gene signatures expressed in metastatic cells that have undergone induction and reversion of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and have induced metastasis (61). Also, urolithins can cross blood brain barrier and, hence, its potential in preventing breast to brain metastasis is worth investigating, since there is very less information on anti-estrogens or aromatase inhibitors that can cross blood brain barrier, which is a potential endocrine tissue (62, 63).

Endometrial cancer is the sixth most commonly occurring cancer in women (64). In premenopausal women, endometrial proliferation is driven by estrogen, whilst after menopause, peripheral tissues like adipose tissue takes over estrogen synthesis, which implies that obesity increases likelihood of endometrial cancer in the postmenopausal uterus (65). In this context, it is worthwhile to mention that the pomegranate and urolithins have been shown to have preventive roles in obesity (4, 66–68). Urolithins are found to inhibit human endometrial cancer cells in an in vitro study (20). It also modulated the expression of ERα-dependent genes like ERβ, PGR, pS2, and GREB1. The UA and UB exhibited antiproliferative activity in the human primary endometriotic cells and reduced the invasion and expression of Matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) and matrix adhesion receptor. Both UA and UB were found to decrease the viability and integrity of endometriosis spheroids (69). These studies are indicative of the ability of urolithin to have protective effects on the endometrium. Endometrial cancers are mostly hormone driven via estrogen receptors (70) and, hence, are often a side effect of SERMs like tamoxifen (71). Therefore, SERMs which do not activate endometrial proliferation is much desired in the present clinical context.If urolithins are further explored for their activities in hormone-dependent tissue, they can be exploited for their SERM activity. Hitherto, there are only in vitro evidence. It is important to consider that, within the body, the urolithins undergoes the phase-II conjugation (72) and reaches the systemic tissues. These conjugates have not been studied for antiproliferative activity in the endometrial cancer. Interestingly, the tissue level of the deconjugation of urolithin glucuronides has also been reported (72). Indeed, more concrete studies and evidence are needed to understand and to prove the real protective capacity of these compounds and their distribution with respect to endometrium and their combinatorial behavior with other synthetic SERMs.

In 2020, prostate cancer was the second most commonly occurring cancer in men, as well as the fifth leading cause of death among men (64). It is noteworthy to mention that prostate cancer has been reported to be driven by ERα, AR, and non-genomic estrogen signaling pathways mediated by orphan receptors like GPR30 and ERRα and, hence, phytoestrogens have been shown to have a beneficial role in prostate cancer (73, 74). Pomegranate and its metabolites, ellagic acid and urolithins, found concentrated in mouse prostate, colon, and intestinal tissues (75), prevent proliferation of prostate cancer (60, 76–79). Interestingly, it has been reported that the beneficial effects of pomegranate juice against prostate cancer may be exerted by urolithin glucuronides and dimethyl ellagic acid (38). Combinatorial treatment with urolithins and bicalutamide, a clinically used non-steroidal anti-androgen, used to treat prostate cancer (80), also showed antiproliferative effects on human prostate cancer cells. Antiproliferative effects of urolithins were more conspicuous in androgen-independent than in androgen dependent cells. Antiproliferative activity of urolithins was mediated by AR through AKT signaling pathway (81) and P53-MDM2 pathway (82). Although the possible role of estrogen receptor has been proposed in other studies (80), there is still no clear evidence. Apart from this, urolithins can strengthen muscles (83), which is an added advantage while treating prostate cancer by androgen deprivation, given that this therapy can cause muscle weakness (84). If this study proves or extends its applicability in humans, urolthins could be helpful in general wellness of prostate, as an SERM, an adjuvant, or for muscle strengthening. Pomegranate and its constituents, including its colonic metabolite, have shown propitious results in prostate cancer. These findings provide very interesting leads and points to the ability of the pomegranate metabolites for the prevention of prostate cancer recurrence (85). The chemopreventive potential of pomegranate ellagitannins, coupled with the finding that urolithin metabolites accumulate in prostate, suggests that pomegranate may be a prospective therapeutic formulation in prostate cancer. Major urolithin that accumulates in the prostate after ellagitannin consumption is UA and its metabolite Urolithin A glucuronide (UA-glu). However, the concentration of these are very low, that is, in the range of ng/g albeit urolithins reach micromolar level concentrations in the bloodstream (38). Hence, the in vitro evidence using supraphysiological concentrations of urolithins or unconjugated urolithins might not give a realistic data on whether these metabolites can be protective in prostate cancer. Studies should be undertaken to understand the physiological levels of urolithin, or its conjugates, that can accumulate in the prostate upon consumption of urolithins at its safe doses, and how is it beneficial in prostate cancer at these doses.

Our earlier studies have shown that pomegranate has a protective role in osteoporosis (86) using MC3T3-E1 cells and ovariectomised Swiss–albino mice. The results indicated that the PME (80 μg/ml) has significantly increased the ALP (Alkaline Phosphatase) activity, in agreement with the findings of Spilmont (87), suggesting its role in modulating osteoblastic cell differentiation. This connotes its potential as a promising nutritional supplement in management of osteoporosis associated with menopause. The UA has been shown ameliorate intervertebral disc degeneration, a common cause of back pain (88) in a needle-puncture rat tail model via c-JUN and PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathways. The UA inhibited the inflammatory molecules and debilitated the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) induced by IL-1β. Both in vitro and in vivo evidence support its protective role in osteoarthritis (44). The question whether urolithins can act via estrogen receptors like estrogen (89) in these cells have not yet been explored. Evidence points to the potential of urolithins in promoting bone health, giving it an edge to be an ideal SERM.

A plethora of studies using different models have adduced that estrogens play a vital part in protecting women against stroke and neurodegenerative diseases, though the mechanisms have not been fully elucidated. All the neural cells express estrogen receptors and the neuroprotective properties are, in part, attributed to the receptor activation in multiple cell types. Microglial cells, the major immune cells that inhabit the CNS, are regulated by estrogen, which, in turn, protects the neuronal functions and prevents neurodegeneration (90). This offers the prospect of selectively targeting estrogen receptors in the treatment of neurodegenerative conditions that comes with aging and menopause. Interestingly, PE is demonstrated to act against Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease in many studies (91–95). Presence of urolithins in brain after consumption of pomegranate has also been reported (95). Urolithins were the only compounds, among 21 others, that is isolated from the extract that met the criteria required for the penetration of blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability (94). The β-amyloid fibrillation was averted by urolithins in an in vitro study. In Alzheimer's model, UA imparts cognitive protection by protecting neurons from cell death, and by triggering neurogenesis via anti-inflammatory signaling. In addition, it inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO) (96), an enzyme that inactivates monoamine neurotransmitters in neurological disorders, such as depression and Parkinson's disease (97). Although the neuroprotective effects of urolithins are reported, evidence is still weak, partly due to the lack of physiologically relevant studies using the circulating conjugated urolithins that might reach brain tissues, in a nutritional context. In 2017, González-Sarrías et al. (98) demonstrated that UA and Iso-UA, but not UB-glu, showed a slight attenuation of the H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in human-derived neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Another study showed that media from lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-BV-2 murine microglial cells co-culture cell model, treated with urolithins, preserve the SH-SY5Y cell viability (99), and protect neuroinflammation, although, methylated urolithins have not been detected in circulation in humans, so far. Thus, to date, only limited studies were performed with conjugated urolithins in the context of neuronal protection. Notably, SERMs like tamoxifen and raloxifene are known to regulate the functions of astrocytes, neurons, and microglia via ERα and the ERβ and G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPR30) (100). Hence, it would be interesting to unveil the potential of the urolithins to act as estrogen receptor modulators in the neuroimmune axes.

Ryu et al. (83) found that feeding of C. elegans during entire lifetime, i.e., from eggs until death with 50 μM of UA, UB, UC, and Urolithin D (UD), has extended the lifespan by 45.4, 36.6, 36, and 19.0%, respectively, and was dose dependent. However, the treatment with ellagic acid had no effect. Mitophagy induced by urolithins in mammalian cells, C. elegans, and rodents culminated in the improvement of the overall health. The short duration of urolithin administration in young worms and mammalian cells reduced the mitochondrial content without affecting the maximal respiratory capacity. This proved that despite the decrease in the mitochondrial pool after UA treatment, the remaining mitochondria are robust and meet the energy requirement. A long-term UA administration in rodents induced mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy in the muscles of both young and old animals. The UA, at a dose of 50 mg/kg daily in aged mice which is equivalent to 4 mg/kg in humans, improved the age-related muscle decline, as well as the muscle strength suggesting its potential for treating an impaired muscle functionality. This dosing is within standard dosing regimens used for both nutrition and pharmaceutical active ingredients. Urolithins may also have different mechanisms which regulate the mitochondrial biogenesis or mitophagy, since they are known to have an estrogen receptor binding affinity. Both UA and UB regulate skeletal muscle mass also by enhancing synthesis of protein and inhibiting the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (101). The UB can produce muscle hypertrophy and reduce muscle atrophy in mice with sciatic nerve denervation. Both urolithins, UA, and UB in different models have shown their capacity to enhance the muscle strength by different mechanisms, thus, implying its therapeutic and preventive potential in enhancing muscle strength in various pathological and age-related maladies. Given these, the ability of these molecules to act via estrogen receptors or how different is its action in females can be examined since estrogen deprivation, or its reduction with menopause (102) or ovarian failure, results in weakness of the skeletal muscle. Evidence points that estrogen improves the mitochondrial membrane microviscosity and the bioenergetic function in skeletal muscle (103) and in muscle proteostasis. It also increases the collagen content of tendons and ligaments. Nevertheless, it must be noted that these benefits come at the cost of a decreased connective tissue stiffness (104). It would be intriguing to know whether urolithins can take over the function of estrogen in its absence.

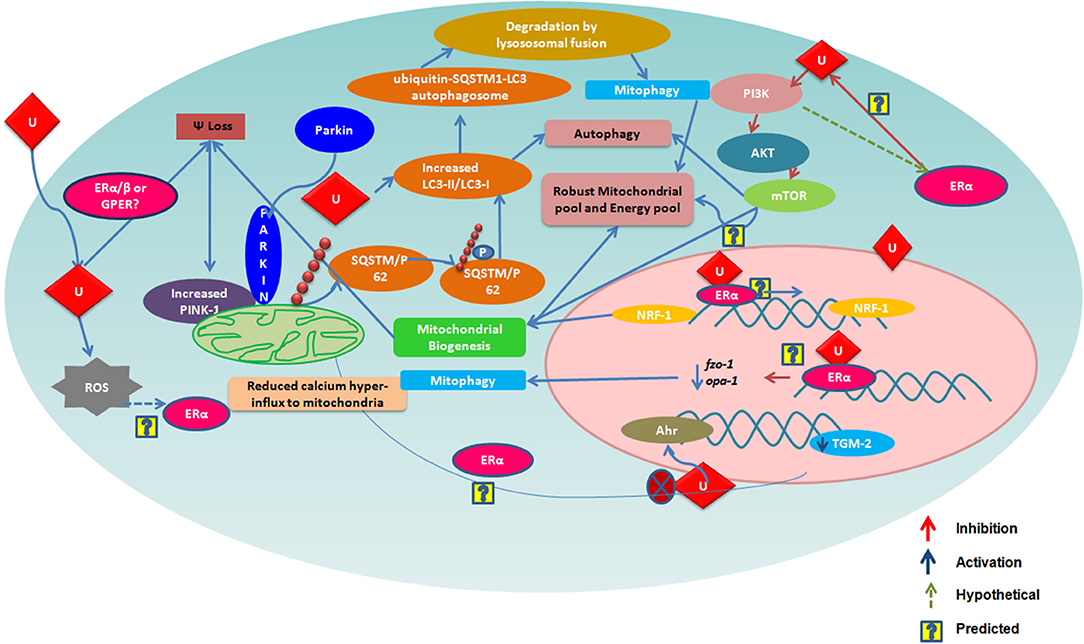

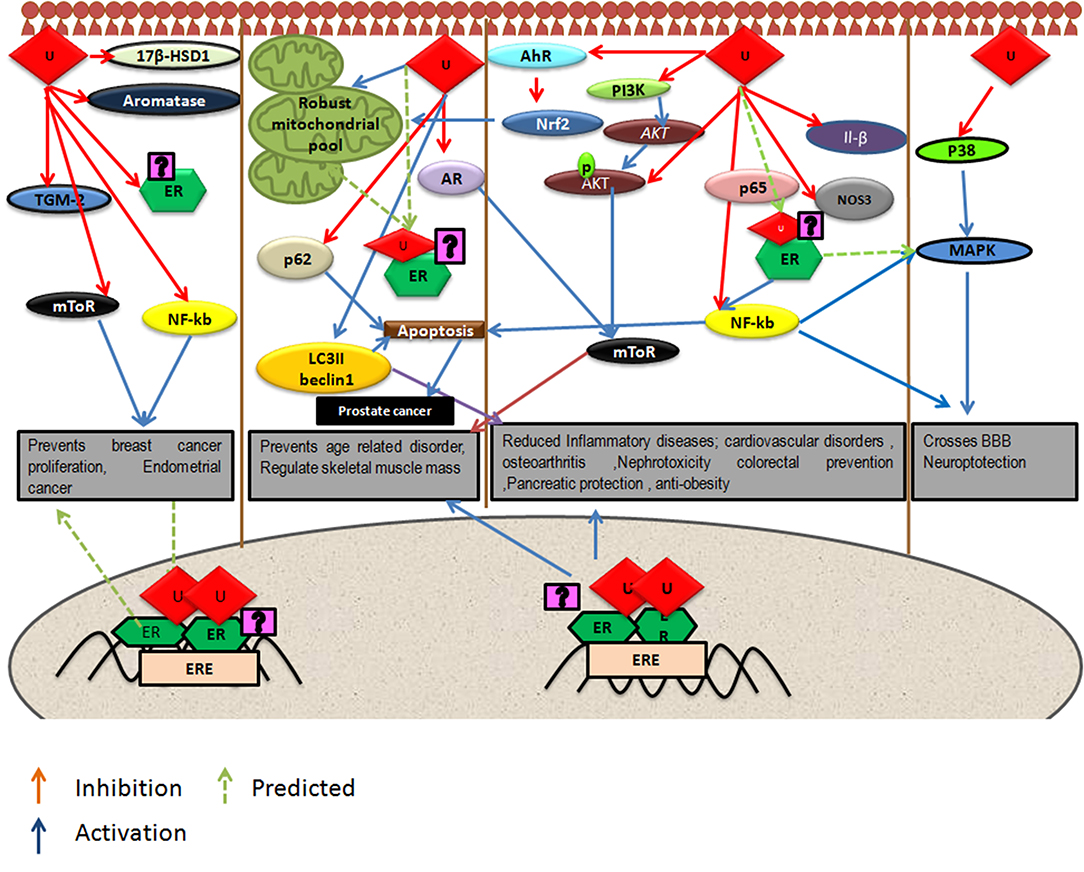

Urolithins can induce mitophagy (83) and mitochondrial biogenesis in aged animals; the final consequence being the improvement of organismal phenotype and maintenance of maximum respiratory capacity emphasizing potential of urolithins having a dual role to maintain healthy mitochondria. The role of estrogen receptors in mediating this effect has not been investigated. The UA was found to induce PINK-1 and has increased the biomarkers for autophagy and mitophagy with ubiquitination of p62/SQSTM. Cells have developed sophisticated and elaborate mechanisms to adapt to stress conditions and alterations in metabolic demands, by regulating mitochondrial number and function by the generation of new mitochondria and by the removal of damaged or unwanted mitochondria for the maintenance of mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis (105). This implicates that urolithins could help in preventing many pathological conditions resulting in or caused from damaged mitochondria or failed mitochondrial metabolism. It has been reported that UA exert gut barrier functions through activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent pathways to upregulate epithelial tight junction proteins (40). The UA inhibits transglutaminase type 2 (TGM2)-mediated mitochondrial calcium influx, which alleviates high glucose-stimulated amyloidogenesis and neuronal degeneration (106), thus, regulating mitochondrial and calcium homeostasis. Tamoxifen, a SERM, is also known to target mitochondria by ER-dependent and independent pathways. Further, the tamoxifen-resistant cells are known to display altered mitochondrial pathways with increased mitochondrial content like many other cancer drugs (107). It has been seen that drug resistance can be overcome by modulating estrogen–estrogen receptor-mitochondrial pathway. Estrogen (108) via ERs is involved in the life cycle of mitochondria and controls the mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial quality control, and mitophagy (108, 109). Examining whether urolithins can modulate mitochondrial pathways via estrogen receptors can help better understand its potential. The Figure 1 consolidates the estrogen mediated mitochondrial pathways and how urolithins, through ERs could or by other mechanisms, can possibly act in a similar way. Thus, urolithins by different molecular pathways exert beneficial effects in multiple tissues, but whether these effects involve estrogen receptors remain elusive. Figure 2 shows the different pathways via which urolithins act and how estrogen receptor could be part of these mechanisms.

Figure 1. The figure depicts various mechanisms by which Urolithin A (UA) is reported to regulate mitochondrial function. Many of these are also known to be modulated via Estrogen Receptor α (ER α). Here, we illustarate pathways that could be mediated by urolithins via ER α and, hence, produce a robust mitochondrial pool maintaining a healthy pool of cells.

Figure 2. Depicts pathways by which urolithins, mainly Urolithin A and Urolithin B, can act in different tissues were U represents either UA or UB. Some of these beneficial effects might be mediated by Estrogen Receptor α (ER α) since these pathways have known to be modulated by Estrogen receptors.

Clomiphene and toremifene SERMs are reported to have potent inhibitory activity in filovirus infections like EBOLA infection (110), while raloxifene hydrochloride and quinestrol inhibit flaviviruses such as Zika virus in ER-independent pathways (111). Use of SERMs in the cytokine storm and in the inflammation associated with COVID-19 is suggested as a promising pharmacological option (112). One of the main reasons that the COVID-19 is a threat to global health is due to the lack of targeted therapeutic agents. Out of the several coronavirus proteins proposed as druggable targets, 3-chymotrypsin-like protease or main protease (Mpro), a non-structural protein that breaks down the viral polyproteins to generate other non-structural proteins, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and helicase, is considered pivotal (113). Given this, it is interesting to note that urolithin metabolites can exert a mild anti-SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition (113) at physiological relevant concentrations (2–50 μM), detectable in human colon tissues after consumption of hydrolyzable tannin-rich foods, as per clinical studies (114). Also, the pomegranate peel extract, punicalin, punicalagin, and UA have the potential to block the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein receptor-binding domain (RBD)-ACE2 receptor on host cells contact, which is one of the first steps of virus infection (115). Additionally, it has been understood that SARS-Cov-2 can activate pro-inflammatory chemokines in the early stage, and this can lead to the development of either a protective immune response or an exacerbated inflammatory response (116). The latter one may lead to cytokine storm, which is clinically manifested by acute respiratory distress syndrome and systemic consequences like intravascular coagulation (116). As said in the earlier section of this review, UA exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in various tissues (39, 45, 117–119) by modulating proteins like NF-kb (44, 45), and other pro-inflammatory molecules like cytokine fractalkine (49, 120). Thus, UA manifests a natural immune-suppressant profile (121). It also protects C. jejuni infection in mice and protects other organs including lungs from inflammatory response (122). Furthermore, a recent study illustrated tissue deconjugation of UA-glu to UA in endotoxemia, thus, increasing free UA in systemic tissues, reaching relevant concentrations, and, hence, probably imparting a higher anti-inflammatory potential (72). In the light of these findings, urolithins with its immune modulatory and anti-inflammatory activity could be exploited to reduce such exacerbated inflammatory response as well.

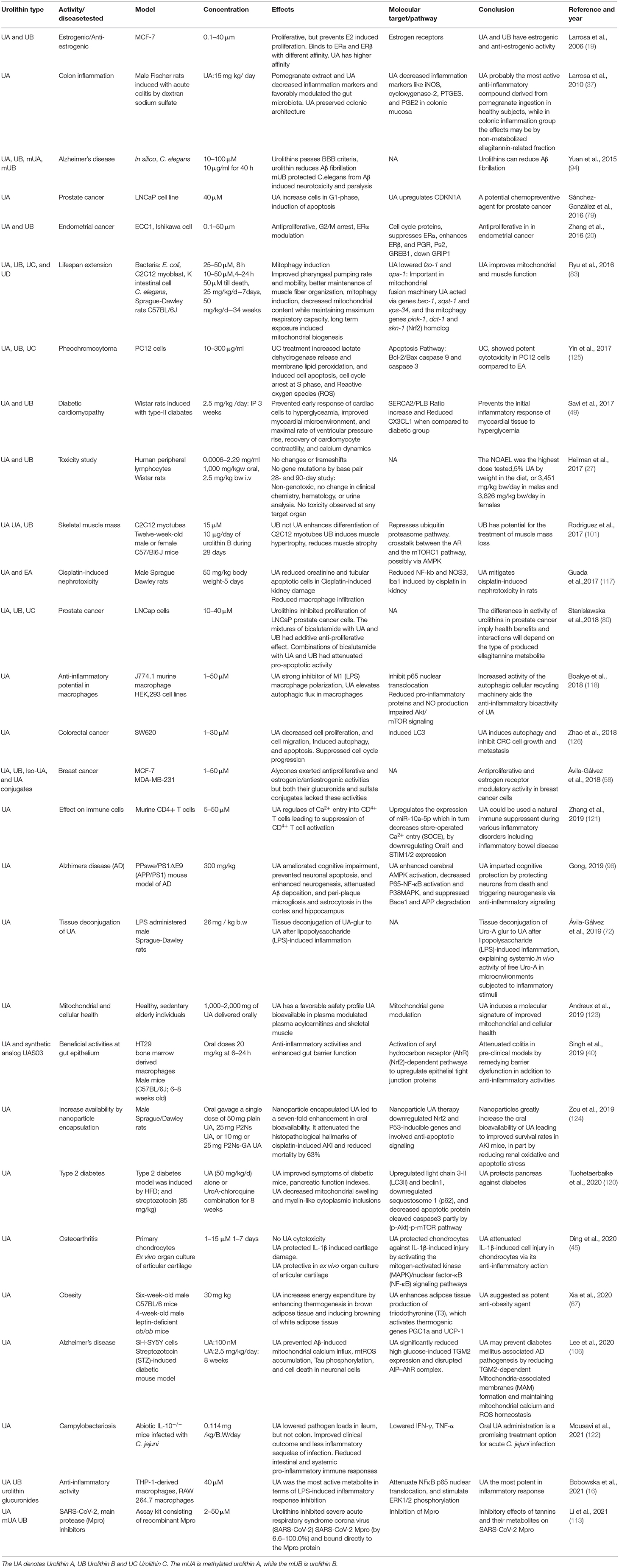

Oral administration of UA has been studied at both preclinical (27, 37, 121) and clinical level (123). Both oral and intravenous administration of urolithins showed a higher prevalence of the conjugated forms of urolithins, namely glucuronidated and sulfonated forms (27). Urolithins did not induce genotoxicity in the in vitro assays. The no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) was the highest dose tested, and UA was given as 5% of the diet, or 3,451 mg/kg bw/day in males and 3,826 mg/kg bw/day in females, in the 90-day oral study. In the in vivo studies, the clinical parameters, blood test, or hematology did not point to any toxicity. Human randomized (123), study on the safety profile of UA in the elderly and sedentary human subjects did not show adverse effects on UA consumption in any of the oral dosing regimens. Its presence was seen in plasma and skeletal muscles. The biomarkers of mitochondrial function in the skeletal muscle and plasma metabolomics were also recorded in the study. Efforts are also being made to make urolithins more bioavailable (28, 123, 124). As mentioned earlier, the UA has also been recently recognized as GRAS for its use as an ingredient by FDA, USA. The major studies performed using urolithins has been consolidated in Table 1.

Table 1. The table consolidates the relevant studies related to Urolithins and their significant outcome.

To summarize what has been discussed, so far, we propose that urolithins could be beneficial in general wellness and health. Its relevance seems more pronounced in the hormone-dependent tissues, which connote its potential in hormone or endocrine-related pathogenesis. A plethora of evidence pointedly illustrate the health benefits of urolithins in cardiovascular health, muscle strengthening, bone health, breast and endometrial cancer, aging, brain related diseases, and pathologies stemming from an inflammatory response or its consequence like in the case of COVID-19 infection. Many of these may involve the hormone receptor estrogen receptors along with the other pathways. The mechanism of action of urolithins, mediated via estrogen receptors, is very sparsely studied. Competitive binding studies and transactivation assays point to its ability to act as an estrogen agonist. However, it is known that estrogen receptors exhibit a complex and dynamic activity depending on the different conformation it attains according to the ligand structure and binding. It depends on the tissue it acts since the co-factors available and recruited by estrogen receptors vary between the cell types. Albeit estrogen receptor agonists, antagonists and SERMS can activate or repress unique genes, they can also trigger or repress similar subset of genes. Ergo, urolithins need to be examined for its responses in different hormone responsive tissues; its potential as estrogenic and endocrine disruptors, and whether the known health benefits involve an ER-mediated action. Urolithins, or its source, which include ellagitannin-rich food like pomegranate and the bacteria responsible for its production, could also serve as supplement as probiotics. Also, studies can be undertaken to illustrate the potential of urolithins at a clinical level on how these molecules would act in combination with an already known synthetic SERM. Nonetheless, due to pleotropic nature of estrogen receptors, it is important to consider the potential long-term merits and the adverse effects of urolithins in the estrogen receptor-dependent tissues. Taking together the recent research on urolithins, we propose this could serve as an endocrine modulator and that further investigations in this direction need attention.

RV and SS conceived the idea of the article. RV and VR screened and retrieved the data and prepared diagrams. RV prepared the manuscript draft. RV, AS, TS, RA, PM, and LL tabulated various studies. SS reviewed and corrected the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

RV and VR acknowledge Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for Senior Research Fellowship (SRF). The study was supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology (SERB-DST) (No. EMR/2016/000557).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We acknowledge the Director, RGCB for constant encouragement and support. We also acknowledge the RGCB core facility.

1. Yang TL, Wu TC, Huang CC, Huang PH, Chung CM, Lin SJ, et al. Association of tamoxifen use and reduced cardiovascular events among Asian females with breast cancer. Circ J. (2014) 78:135–40. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0266

2. Yu M, Jiang M, Chen Y, Zhang S, Zhang W, Yang X, et al. Inhibition of macrophage CD36 expression and cellular oxLDL accumulation by tamoxifen: a PPARγ dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. (2016) 291:16977–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.740092

3. Korkmazer E, Solak N, Tokgöz VY. Assessment of thickened endometrium in tamoxifen therapy. Turk J Obstetr Gynecol. (2014) 11:215. doi: 10.4274/tjod.82621

4. Sreeja S, Kumar TRS, Lakshmi BS, Sreeja S. Pomegranate extract demonstrate a selective estrogen receptor modulator profile in human tumor cell lines and in vivo models of estrogen deprivation. J Nutr Biochem. (2012) 23:725–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.03.015

5. Basu P, Maier C. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer: in vitro anticancer activities of isoflavones, lignans, coumestans, stilbenes and their analogs and derivatives. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 107:1648–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.100

6. Stojanov S, Kreft S. Gut microbiota and the metabolism of phytoestrogens. Rev Brasil Farmacog. (2020) 30:145–54. doi: 10.1007/s43450-020-00049-x

7. Hameed ASS, Rawat PS, Meng X, Liu W. Biotransformation of dietary phytoestrogens by gut microbes: a review on bidirectional interaction between phytoestrogen metabolism and gut microbiota. Biotechnol Adv. (2020) 43:107576. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107576

8. Rosenfeld CS. Xenoestrogen effects on the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. (2021) 19:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coemr.2021.05.006

9. Rosenfeld CS. Effects of phytoestrogens on the developing brain, gut microbiota, and risk for neurobehavioral disorders. Front Nutr. (2019) 6:142. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00142

10. Fuentes N, Silveyra P. Estrogen receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. (2019) 116:135–70. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.01.001

11. Yaşar P, Ayaz G, User SD, Güpür G, Muyan M. Molecular mechanism of estrogen–estrogen receptor signaling. Reprod Med Biol. (2017) 16:4–20. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12006

12. Vini R, Sreeja S. Punica granatum and its therapeutic implications on breast carcinogenesis: a review. Biofactors. (2015) 41:78–89. doi: 10.1002/biof.1206

13. Giménez-Bastida JA, Ávila-Gálvez MÁ, Espín JC, González-Sarrías A. Evidence for health properties of pomegranate juices and extracts beyond nutrition: a critical systematic review of human studies. Trends Food Sci Technol. (2021) 114:410. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.06.014

14. González-Sarrías A, Núñez-Sánchez MÁ, Tomás-Barberán FA, Espín JC. Neuroprotective effects of bioavailable polyphenol-derived metabolites against oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J Agric Food Chem. (2017) 65:752–8. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04538

15. García-Villalba R, Selma MV, Espín JC, Tomás-Barberán FA. Identification of novel urolithin metabolites in human feces and urine after the intake of a pomegranate extract. J Agric Food Chem. (2019) 67:11099–107. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b04435

16. Bobowska A, Granica S, Filipek A, Melzig MF, Moeslinger T, Zentek J, et al. Comparative studies of urolithins and their phase II metabolites on macrophage and neutrophil functions. Eur J Nutr. (2021) 60:1957–72. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02386-y

17. Singh A, D'Amico D, Andreux PA, Dunngalvin G, Kern T, Blanco-Bose W, et al. Direct supplementation with Urolithin A overcomes limitations of dietary exposure and gut microbiome variability in healthy adults to achieve consistent levels across the population. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2021) 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-00950-1

18. Tomás-Barberán FA, González-Sarrías A, García-Villalba R, Núñez-Sánchez MA, Selma MV, García-Conesa MT, et al. Urolithins, the rescue of “old” metabolites to understand a “new” concept: metabotypes as a nexus among phenolic metabolism, microbiota dysbiosis, and host health status. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2017) 61:1500901. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500901

19. Larrosa M, González-Sarrías A, García-Conesa MT, Tomás-Barberán FA, Espín JC. Urolithins, ellagic acid-derived metabolites produced by human colonic microflora, exhibit estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities. J Agric Food Chem. (2006) 54:1611–20. doi: 10.1021/jf0527403

20. Zhang W, Chen JH, Aguilera Barrantes I, Shiau CW, Sheng X, Wang LS, et al. Urolithin A suppresses the proliferation of endometrial cancer cells by mediating estrogen receptor α dependent gene expression. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2016) 60:2387–95. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600048

21. Skledar DG, Tomašič T, Dolenc MS, Mašič LP, Zega A. Evaluation of endocrine activities of ellagic acid and urolithins using reporter gene assays. Chemosphere. (2019) 220:706–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.185

22. Ávila-Gálvez MÁ, García-Villalba R, Martínez-Díaz F, Ocaña-Castillo B, Monedero-Saiz T, Torrecillas-Sánchez A, et al. Metabolic profiling of dietary polyphenols and methylxanthines in normal and malignant mammary tissues from breast cancer patients. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2019) 63:e1801239. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801239

23. Papoutsi Z, Kassi E, Tsiapara A, Fokialakis N, Chrousos GP, Moutsatsou P. Evaluation of estrogenic/antiestrogenic activity of ellagic acid via the estrogen receptor subtypes ERα and ERβ. J Agric Food Chem. (2005) 53:7715–20. doi: 10.1021/jf0510539

24. Adams LS, Zhang Y, Seeram NP, Heber D, Chen S. Pomegranate ellagitannin–derived compounds exhibit antiproliferative and antiaromatase activity in breast cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Prevent Res. (2010) 3:108–13. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0225

25. Dellafiora L, Milioli M, Falco A, Interlandi M, Mohamed A, Frotscher M, et al. A hybrid in silico/in vitro target fishing study to mine novel targets of urolithin A and B: a step towards a better comprehension of their estrogenicity. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2020) 64:2000289. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202000289

26. Kiyama R, Wada-Kiyama Y. Estrogenic endocrine disruptors: molecular mechanisms of action. Environ Int. (2015) 83:11–40. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.05.012

27. Heilman J, Andreux P, Tran N, Rinsch C, Blanco-Bose W. Safety assessment of Urolithin A a metabolite produced by the human gut microbiota upon dietary intake of plant derived ellagitannins and ellagic acid. Food Chem Toxicol. (2017) 108:289–97. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.07.050

28. Singh A, Andreux P, Blanco-Bose W, Aebischer P, Auwerx J, Rinsch C. Translating urolithin a benefits on muscle mitochondria to humans. Innov Aging. (2018) 2:92. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy023.351

29. Kolodziejczyk AA, Zheng D, Elinav E. Diet–microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2019) 17:742–53. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0256-8

30. Cerdá B, Periago P, Espín JC, Tomás-Barberán FA. Identification of urolithin A as a metabolite produced by human colon microflora from ellagic acid and related compounds. J Agric Food Chem. (2005) 53:5571–6. doi: 10.1021/jf050384i

31. Selma MV, Tomas-Barberan FA, Beltran D, García-Villalba R, Espín JC. Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens sp. nov., a urolithin-producing bacterium isolated from the human gut. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. (2014) 64:2346–52. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.055095-0

32. Selma MV, Beltrán D, Luna MC, Romo-Vaquero M, García-Villalba R, Mira A, et al. Isolation of human intestinal bacteria capable of producing the bioactive metabolite isourolithin A from ellagic acid. Front Microbiol. (2017) 8:1521. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01521

33. Selma MV, Beltrán D, García-Villalba R, Espín JC, Tomás-Barberán FA. Description of urolithin production capacity from ellagic acid of two humans intestinal Gordonibacter species. Food Funct. (2014) 5:1779–84. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00092G

34. Iglesias-Aguirre CE, Cortés-Martín A, Ávila-Gálvez MÁ, Giménez-Bastida JA, Selma MV, González-Sarrías A, et al. Main drivers of (poly)phenol effects on human health: metabolite production and/or gut microbiota-associated metabotypes? Food Funct. (2021) 12:10324–55. doi: 10.1039/D1FO02033A

35. Cortés-Martín A, García-Villalba R, García-Mantrana I, Rodríguez-Varela A, Romo-Vaquero M, Collado MC, et al. Urolithins in human breast milk after walnut intake and kinetics of gordonibacter colonization in newly born: the role of mothers' urolithin metabotypes. J Agric Food Chem. (2020) 68:12606–16. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04821

36. Bialonska D, Kasimsetty SG, Khan SI, Ferreira D. Urolithins, intestinal microbial metabolites of pomegranate ellagitannins, exhibit potent antioxidant activity in a cell-based assay. J Agric Food Chem. (2009) 57:10181–6. doi: 10.1021/jf9025794

37. Larrosa M, González-Sarrías A, Yáñez-Gascón MJ, Selma MV, Azorín-Ortuño M, Toti S, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of a pomegranate extract and its metabolite urolithin-A in a colitis rat model and the effect of colon inflammation on phenolic metabolism. J Nutr Biochem. (2010) 21:717725. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.04.012

38. González-Sarrías A, Larrosa M, Tomás-Barberán FA, Dolara P, Espín JC. NF-κB-dependent anti-inflammatory activity of urolithins, gut microbiota ellagic acid-derived metabolites, in human colonic fibroblasts. Brit J Nutr. (2010) 104:503–12. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000826

39. Sala R, Mena P, Savi M, Brighenti F, Crozier A, Miragoli M, et al. Urolithins at physiological concentrations affect the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factor in cultured cardiac cells in hyperglucidic conditions. J Funct Foods. (2015) 15:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.03.019

40. Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Bodduluri SR, Baby BV, Hegde B, Kotla NG., et al. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07859-7

41. Jing T, Liao J, Shen K, Chen X, Xu Z, Tian W, et al. Protective effect of urolithin a on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice via modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress. Food Chem Toxicol. (2019) 129:108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.04.031

42. Toney AM, Fox D, Chaidez V, Ramer-Tait AE, Chung S. Immunomodulatory role of urolithin A on metabolic diseases. Biomedicines. (2021) 9:192. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020192

43. González-Sarrías A, Giménez-Bastida JA, García-Conesa MT, Gómez-Sánchez MB, García-Talavera NV, Gil-Izquierdo A et al. Occurrence of urolithins, gut microbiota ellagic acid metabolites and proliferation markers expression response in the human prostate gland upon consumption of walnuts and pomegranate juice. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2010) 54:311–22. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900152

44. Fu X, Gong LF, Wu YF, Lin Z, Jiang BJ, Wu L, et al. Urolithin A targets the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathways and prevents IL-1β-induced inflammatory response in human osteoarthritis: in vitro and in vivo studies. Food Funct. (2019) 10:6135–46. doi: 10.1039/C9FO01332F

45. Ding SL, Pang ZY, Chen XM, Li Z, Liu XX, Zhai QL, et al. Urolithin a attenuates IL-1β-induced inflammatory responses and cartilage degradation via inhibiting the MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in rat articular chondrocytes. J Inflamm. (2020) 17:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12950-020-00242-8

46. Villa A, Rizzi N, Vegeto E, Ciana P, Maggi A. Estrogen accelerates the resolution of inflammation in macrophagic cells. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep15224

47. Giménez-Bastida JA, González-Sarrías A, Larrosa M, Tomás-Barberán F, Espín JC, García-Conesa MT. Ellagitannin metabolites, urolithin A glucuronide and its aglycone urolithin A, ameliorate TNF-α-induced inflammation and associated molecular markers in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2012) 56:784–96. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100677

48. Savi M, Bocchi L, Bresciani L, Falco A, Quaini F, Mena P, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-induced impairment of cardiomyocyte function and the protective role of urolithin B-glucuronide. Molecules. (2018) 23:549. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030549

49. Savi M, Bocchi L, Mena P, Dall'Asta M, Crozier A, Brighenti F, et al. In vivo administration of urolithin A and B prevents the occurrence of cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2017) 16:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0561-3

50. Wang D, Özen C, Abu-Reidah IM, Chigurupati S, Patra JK, Horbanczuk JO, et al. Vasculoprotective effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Front Pharmacol. (2018). 9:544. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00544

51. Shema-Didi L, Kristal B, Sela S, Geron R, Ore L. Does pomegranate intake attenuate cardiovascular risk factors in hemodialysis patients? Nutr J. (2014) 13:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-18

52. Neyrinck AM, Catry E, Taminiau B, Cani PD, Bindels LB, Daube G, et al. Chitin–glucan and pomegranate polyphenols improve endothelial dysfunction. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50700-4

53. Sahebkar A, Ferri C, Giorgini P, Bo S, Nachtigal P, Grassi D. Effects of pomegranate juice on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res. (2017) 115:149–61. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.018

54. Ueda K, Adachi Y, Liu P, Fukuma N, Takimoto E. Regulatory actions of estrogen receptor signaling in the cardiovascular system. Front Endocrinol. (2020) 10:909. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00909

55. Lastra G, Harbuz-Miller I, Sowers JR, Manrique CM. Estrogen receptor signaling and cardiovascular function. In: LaMarca B, Alexander BT, editors. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Physiology and Pathophysiology. New York, NY: Academic Press. (2019) p. 13–22. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-813197-8.00002-6

56. Nită AR, Knock GA, Heads RJ. Signalling mechanisms in the cardiovascular protective effects of estrogen: with a focus on rapid/membrane signalling. Curr Res Physiol. 4:103–118. doi: 10.1016/j.crphys.2021.03.003

57. Vini R, Juberiya AM, Sreeja S. Evidence of pomegranate methanolic extract in antagonizing the endogenous SERM, 27-hydroxycholesterol. IUBMB Life. (2016) 68:116–21. doi: 10.1002/iub.1465

58. Ávila-Gálvez MÁ, Espín JC, González-Sarrías A. Physiological relevance of the antiproliferative and estrogenic effects of dietary polyphenol aglycones versus their phase-II metabolites on breast cancer cells: a call of caution. J Agric Food Chem. (2018) 66:8547–55. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b03100

59. Aka JA, Zerradi M, Houle F, Huot J, Lin SX. 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 modulates breast cancer protein profile and impacts cell migration. Breast Cancer Res. (2012) 14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/bcr3207

60. Sánchez-González C, Noé V, Izquierdo-Pulido M. Walnut polyphenol metabolites, urolithins A and B, inhibit the expression of the prostate-specific antigen and the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Food Funct. (2014) 5:2922–30. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00542B

61. Shinde A, Paez JS, Libring S, Hopkins K, Solorio L, Wendt MK. Transglutaminase-2 facilitates extracellular vesicle-mediated establishment of the metastatic niche. Oncogenesis. (2020) 9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41389-020-0204-5

62. Banks WA. The blood–brain barrier as an endocrine tissue. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:444–55. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0213-7

63. McDonnell DP, Wardell SE, Norris JD. Oral selective estrogen receptor downregulators (SERDs), a breakthrough endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J Med Chem. (2015) 58:4883–7. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00760

64. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

65. Onstad MA, Schmandt RE, Lu KH. Addressing the role of obesity in endometrial cancer risk, prevention, and treatment. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:4225. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.4638

66. Raffaele M, Licari M, Amin S, Alex R, Shen HH, Singh SP, et al. Cold press pomegranate seed oil attenuates dietary-obesity induced hepatic steatosis and fibrosis through antioxidant and mitochondrial pathways in obese mice. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:5469. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155469

67. Xia B, Shi XC, Xie BC, Zhu MQ, Chen Y, Chu XY, et al. Urolithin A exerts antiobesity effects through enhancing adipose tissue thermogenesis in mice. PLoS Biol. (2020) 18:e3000688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000688

68. Abdulrahman AO, Alzubaidi MY, Nadeem MS, Khan JA, Rather IA, Khan MI. Effects of urolithins on obesity-associated gut dysbiosis in rats fed on a high-fat diet. Int J Food Sci Nutr. (2021) 72:923–34. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2021.1886255

69. Mc Cormack B, Maenhoudt N, Fincke V, Stejskalova A, Greve B, Kiesel L, et al. The ellagic acid metabolites urolithin A and B differentially affect growth, adhesion, motility, and invasion of endometriotic cells in vitro. Hum Reprod. (2021). 36:1501–19. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab053

70. Vahrenkamp JM, Yang CH, Rodriguez AC, Almomen A, Berrett KC, Trujillo AN, et al. Clinical and genomic crosstalk between glucocorticoid receptor and estrogen receptor α in endometrial cancer. Cell Rep. (2018) 22:2995–3005. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.076

71. Droog M, Nevedomskaya E, Kim Y, Severson T, Flach KD, Opdam M, et al. Comparative cistromics reveals genomic cross-talk between FOXA1 and ERα in tamoxifen-associated endometrial carcinomas. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:3773–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1813

72. Ávila-Gálvez MA, Giménez-Bastida JA, González-Sarrías A, Espín JC. Tissue deconjugation of urolithin A glucuronide to free urolithin A in systemic inflammation. Food Funct. (2019) 10:3135–41. doi: 10.1039/C9FO00298G

73. Bonkhoff H. Estrogen receptor signaling in prostate cancer: Implications for carcinogenesis and tumor progression. Prostate. (2018) 78:2–10. doi: 10.1002/pros.23446

74. Di Zazzo E, Galasso G, Giovannelli P, Di Donato M, Castoria G. Estrogens and their receptors in prostate cancer: therapeutic implications. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:2. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00002

75. Seeram NP, Aronson WJ, Zhang Y, Henning SM, Moro A, Lee RP, et al. Pomegranate ellagitannin-derived metabolites inhibit prostate cancer growth and localize to the mouse prostate gland. J Agric Food Chem. (2007) 55:7732–7. doi: 10.1021/jf071303g

76. Vicinanza R, Zhang Y, Henning SM, Li Z, Heber D. Urolithin A and ellagic acid inhibit prostate cancer through different molecular mechanisms: implications of gut microbiome metabolism for cancer prevention. Faseb J. (2011) 235–4. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.25.1_supplement.235.4

77. Vicinanza R, Zhang Y, Henning SM, Heber D. Pomegranate juice metabolites, ellagic acid and urolithin a, synergistically inhibit androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth via distinct effects on cell cycle control and apoptosis. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. (2013) 2013:247504. doi: 10.1155/2013/247504

78. Stolarczyk M, Piwowarski JP, Granica S, Stefańska J, Naruszewicz M, Kiss AK. Extracts from Epilobium sp. herbs, their components and gut microbiota metabolites of Epilobium ellagitannins, urolithins, inhibit hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells (LNCaP) proliferation and PSA secretion. Phytother Res. (2013) 27:1842–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4941

79. Sánchez-González C, Izquierdo-Pulido M, Noé V. Urolithin A causes p21 up-regulation in prostate cancer cells. Eur J Nutr. (2016) 55:1099–112. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0924-z

80. Stanisławska IJ, Piwowarski JP, Granica S, Kiss AK. The effects of urolithins on the response of prostate cancer cells to non-steroidal antiandrogen bicalutamide. Phytomedicine. (2018) 46:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.054

81. Dahiya NR, Chandrasekaran B, Kolluru V, Ankem M, Damodaran C, Vadhanam MV. A natural molecule, urolithin A, downregulates androgen receptor activation and suppresses growth of prostate cancer. Mol Carcinog. (2018) 57:1332–41. doi: 10.1002/mc.22848

82. Saleem YIM, Albassam H, Selim M. Urolithin A induces prostate cancer cell death in p53-dependent and in p53-independent manner. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 59:1607–18. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2019-2971

83. Ryu D, Mouchiroud L, Andreux PA, Katsyuba E, Moullan N, Nicolet-dit-Félix AA, et al. Urolithin A induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nat Med. (2016) 22:879. doi: 10.1038/nm.4132

84. Newton RU, Galvão DA, Spry N, Joseph D, Chambers SK, Gardiner RA, et al. Timing of exercise for muscle strength and physical function in men initiating ADT for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. (2020) 23:457–64. doi: 10.1038/s41391-019-0200-z

85. Sharma P, McClees SF, Afaq F. Pomegranate for prevention and treatment of cancer: an update. Molecules. (2017) 22:177. doi: 10.3390/molecules22010177

86. Sreekumar S, Sithul H, Muraleedharan P, Azeez JM, Sreeharshan S. Pomegranate fruit as a rich source of biologically active compounds. Biomed Res Int. (2014). 2014:686921. doi: 10.1155/2014/686921

87. Spilmont M, Léotoing L, Davicco MJ, Lebecque P, Mercier S, Miot-Noirault E, et al. Pomegranate and its derivatives can improve bone health through decreased inflammation and oxidative stress in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Eur J Nutr. (2014) 53:1155–64. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0615-6

88. Liu H, Kang H, Song C, Lei Z, Li L, Guo J, et al. Urolithin A inhibits the catabolic effect of TNFα on nucleus pulposus cell and alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration in vivo. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:1043. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01043

89. Khalid AB, Krum SA. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta in bone. Bone. (2016) 87:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.03.016

90. Villa A, Vegeto E, Poletti A, Maggi A. Estrogens, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration. Endocr Rev. (2016) 37:72–402. doi: 10.1210/er.2016-1007

91. Rojanathammanee L, Puig KL, Combs CK. Pomegranate polyphenols and extract inhibit nuclear factor ofactivated T-cell activity and microglial activation in vitro and in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Nutr. (2013) 143:597–605. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.169516

92. Ahmed AH, Subaiea GM, Eid A, Li L, Seeram NP, Zawia NH. Pomegranate extract modulates processing of amyloid-β precursor protein in an aged Alzheimer's disease animal model. Curr Alzheimer Res. (2014) 11:834–43. doi: 10.2174/1567205011666141001115348

93. Subash S, Essa MM, Al-Asmi A, Al-Adawi S, Vaishnav R, Braidy N, et al. Pomegranate from Oman alleviates the brain oxidative damage in transgenic mousemodel of Alzheimer's disease. J Tradit Complement Med. (2014) 4:232–8. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.139107

94. Yuan T, Ma H, Liu W, Niesen DB, Shah N, Crews R, et al. Pomegranate's neuroprotective effects against Alzheimer's disease are mediated by urolithins, its ellagitannin-gut microbial derived metabolites. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2015) 7:26–33. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00260

95. Kujawska M, Jourdes M, Kurpik M, Szulc M, Szaefer H, Chmielarz P, et al. Neuroprotective effects of pomegranate juice against Parkinson's disease and presence of ellagitannins-derived metabolite—Urolithin A—In the brain. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:202. doi: 10.3390/ijms21010202

96. Gong Z, Huang J, Xu B, Ou Z, Zhang L, Lin X, et al. Urolithin A attenuates memory impairment and neuroinflammation in APP/PS1 mice. J Neuroinflammation. (2019) 16:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1450-3

97. Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Vemula PK, Haribabu B, Jala VR. Microbial metabolite urolithin B inhibits recombinant human monoamine oxidase A enzyme. Metabolites. (2020) 10:258. doi: 10.3390/metabo10060258

98. González-Sarrías A, García Villalba R, Romo Vaquero M, Alasalvar C, Örem A, Zafrilla P, et al. (2017). Clustering according to urolithin metabotype explains the interindividual variability in the improvement of cardiovascular risk biomarkers in overweight-obese individuals consuming pomegranate: a randomized clinical trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 61:1600830. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600830

99. DaSilva NA, Nahar PP, Ma H, Eid A, Wei Z, Meschwitz S, et al. Pomegranate ellagitannin-gut microbial-derived metabolites, urolithins, inhibit neuroinflammation in vitro. Nutr Neurosci. (2019) 22:185–95. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1360558

100. Baez-Jurado E, Rincón-Benavides MA, Hidalgo-Lanussa O, Guio-Vega G, Ashraf GM, Sahebkar A, et al. Molecular mechanisms involved in the protective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators in brain cells. Front Neuroendocrinol. (2019) 52:44–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.09.001

101. Rodriguez J, Pierre N, Naslain D, Bontemps F, Ferreira D, Priem F, Laakkonen EK et al. Urolithin B a newly identified regulator of skeletal muscle mass. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. (2017) 8:583–97. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12190

102. Sipilä S, Törmäkangas T, Sillanpää E, Aukee P, Kujala UMKovanen V, et al. Muscle and bone mass in middle aged women: role of menopausal status and physical activity. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. (2020) 11:698–709. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12547

103. Torres MJ, Kew KA, Ryan TE, Pennington ER, Lin CT, Buddo KA, et al. 17β-Estradiol directly lowers mitochondrial membrane microviscosity and improves bioenergetic function in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. (2018) 27:167–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.003

104. Chidi-Ogbolu N, Baar K. Effect of estrogen on musculoskeletal performance and injury risk. Front Physiol. (2019) 9:1834. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01834

105. Ploumi C, Daskalaki I, Tavernarakis N. Mitochondrial biogenesis and clearance: a balancing act. FEBS J. (2017) 284:183–95. doi: 10.1111/febs.13820

106. Lee HJ, Jung YH, Choi GE, Kim JS, Chae CW, Lim JR, et al. Urolithin A suppresses high glucose-induced neuronal amyloidogenesis by modulating TGM2-dependent ER-mitochondria contacts and calcium homeostasis. Cell Death Differ. (2021) 28:184–202. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-0593-1

107. Tomková V, Sandoval-Acuña C, Torrealba N, Truksa J. Mitochondrial fragmentation, elevated mitochondrial superoxide and respiratory supercomplexes disassembly is connected with the tamoxifen-resistant phenotype of breast cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. (2019) 143:510–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.09.004

108. Klinge CM. Estrogenic control of mitochondrial function. Redox Biol. (2020) 31:101435. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101435

109. Ventura-Clapier R, Piquereau J, Veksler V, Garnier A. Estrogens, estrogen receptors effects on cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria. Front Endocrinol. (2019) 10:557. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00557

110. Johansen LM, Brannan JM, Delos SE, Shoemaker CJ, Stossel A, Lear C, et al. FDA-approved selective estrogen receptor modulators inhibit Ebola virus infection. Sci Transl Med. (2013) 5: 190ra79. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005471

111. Eyre NS, Kirby EN, Anfiteatro DR, Bracho G, Russo AG, White PA, et al. Identification of estrogen receptor modulators as inhibitors of flavivirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2020) 64:e00289–20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00289-20

112. Calderone A, Menichetti F, Santini F, Colangelo L, Lucenteforte E, Calderone V. Selective estrogen receptor modulators in covid-19: a possible therapeutic option? Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:1085. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01085

113. Li H, Xu F, Liu C, Cai A, Dain JA, Li D, et al. Inhibitory effects and surface plasmon resonance-based binding affinities of dietary hydrolyzable tannins and their gut microbial metabolites on SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J Agric Food Chem. (2021) 69:12197–208. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03521

114. Nuñez-Sánchez MA, García-Villalba R, Monedero-Saiz T, García-Talavera NV, Gómez-Sánchez MB, Sánchez-Álvarez C, et al. Targeted metabolic profiling of pomegranate polyphenols and urolithins in plasma, urine and colon tissues from colorectal cancer patients. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2014) 58:1199–211. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300931

115. Suručić R, Travar M, Petković M, Tubić B, Stojiljković MP, GrabeŽ M, et al. Pomegranate peel extract polyphenols attenuate the SARS-CoV-2 S-glycoprotein binding ability to ACE2 receptor: in silico and in vitro studies. Bioorg Chem. (2021) 114:105145. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105145

116. García LF. Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1441. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01441

117. Guada M, Ganugula R, Vadhanam M, Kumar MNR. Urolithin A mitigates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibiting renal inflammation and apoptosis in an experimental rat model. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. (2017) 363:58–65. doi: 10.1124/jpet,0.117.242420

118. Boakye YD, Groyer L, Heiss EH. An increased autophagic flux contributes to the anti-inflammatory potential of urolithin A in macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. (2018) 1862:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.10.006

119. Li Q, Li K, Chen Z, Zhou B. Anti-renal fibrosis and anti-inflammation effect of urolithin B, ellagitannin-gut microbial-derived metabolites in unilateral ureteral obstruction rats. J Funct Foods. (2020) 65:103748. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103748

120. Tuohetaerbaike B, Zhang Y, Tian Y, nan Zhang N, Kang J, Mao X, et al. Pancreas protective effects of Urolithin A on type 2 diabetic mice induced by high fat and streptozotocin via regulating autophagy and AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2020) 250:112479. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112479

121. Zhang S, Al-Maghout T, Cao I, Pelzl L, Salker M, Veldhoen M et al. Gut bacterial metabolite Urolithin A (UA) mitigates Ca2+ entry in T cells by regulating miR-10a-5p. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1737. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01737

122. Mousavi S, Weschka D, Bereswill S, Heimesaat MM. Preclinical evaluation of oral urolithin-a for the treatment of acute Campylobacteriosis in Campylobacter jejuni infected microbiota-depleted IL-10−/− mice. Pathogens. (2021) 10:7. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10010007

123. Andreux PA, Blanco-Bose W, Ryu D, Burdet F, Ibberson M, Aebischer P, et al. The mitophagy activator urolithin A is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans. Nat Metab. (2019) 1:595–603. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0073-4

124. Zou D, Ganugula R, Arora M, Nabity MB, Sheikh-Hamad D, Kumar MR. Oral delivery of nanoparticle urolithin A normalizes cellular stress and improves survival in mouse model of cisplatin-induced AKI. Amer J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2019) 317:F1255–64. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00346.2019

125. Yin P, Zhang J, Yan L, Yang L, Sun L, Shi L, et al. Urolithin C a gut metabolite of ellagic acid, induces apoptosis in PC12 cells through a mitochondria-mediated pathway. RSC Adv. (2017) 7:17254–63. doi: 10.1039/C7RA01548H

Keywords: urolithin, estrogen receptor, selective estrogen receptor modulators, pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), PhytoSERM

Citation: Vini R, Azeez JM, Remadevi V, Susmi TR, Ayswarya RS, Sujatha AS, Muraleedharan P, Lathika LM and Sreeharshan S (2022) Urolithins: The Colon Microbiota Metabolites as Endocrine Modulators: Prospects and Perspectives. Front. Nutr. 8:800990. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.800990

Received: 24 October 2021; Accepted: 10 December 2021;

Published: 02 February 2022.

Edited by:

Michele Barone, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyReviewed by:

Antonio González-Sarrías, Center for Edaphology and Applied Biology of Segura, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), SpainCopyright © 2022 Vini, Azeez, Remadevi, Susmi, Ayswarya, Sujatha, Muraleedharan, Lathika and Sreeharshan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sreeja Sreeharshan, c3NyZWVqYUByZ2NiLnJlcy5pbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.