- 1Curtin University Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

- 2Centre for Advanced Food Enginomics (CAFE), The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

This exploratory study of Gen Z consumers (n = 227) examines perceptions and opinions about cultured meat of young adults residing in Sydney, Australia. It uses an online survey and describes the findings quantitatively and through the words of the study participants. The results show that the majority (72%) of the participants are not ready to accept cultured meat; nonetheless, many think that it is a viable idea because of the need to transition to more sustainable food options and improve animal welfare. When faced with a choice between different alternatives to farmed meat, a third of the participants reject cultured meat and edible insects but accept plant-based substitutes finding them more natural. Concerns about masculinity and betraying Australia as a country of quality animal meat are also raised. A significant number of young people (28%) however are prepared to try cultured meat. Environmental and health concerns may influence a broader section of society to embrace this novelty. With its power as the emerging new consumers, Gen Z is putting the future of cultured meat under scrutiny.

Introduction

There is increasing awareness about the negative impacts of the current levels of meat consumption on the natural environment and the planet's ecosystems (1). For example, the disproportionately large appropriation of land for grazing and production of animal feed, is a major contributing factor for the highest rate of biodiversity loss and species extinction in human history (2). Further destructive consequences from excessive consumption of animal-based foods are manifested with the precarious increases in greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use, deforestation, land, and water pollution. In 2019, there have also been significant social unrest and protests across the globe by groups concerned about climate change as well as the exploitation of animals for human consumption (3, 4). This has resulted in confrontations between those who believe that meat is an essential component of the human diet equated with good nutritional qualities, strength and masculinity (5), and those who argue that the long period of dependence on livestock as food should be assigned to the past (6). The creation of cultured meat leading to cellular agriculture is the way of resolving these tensions emerging after 20 years of scientific research and recent investment waves (7).

Cultured Meat

Producing animal meat without livestock (8) is being described as a tissue-engineering technology which uses live cells taken painlessly from the animal's body to be proliferated and grown independently from its organism. This cultured meat, also referred to as in-vitro, cell-based, lab-grown, cell-cultured, fake and clean meat, is perceived to have animal welfare, environmental and health advantages over traditional meat. As cultured meat is still in its infancy, any claims about its energy or water efficiency are yet to be fully substantiated (9). An anticipatory life-cycle analysis (10) suggests that cultured meat would require smaller agricultural inputs and less land, however it would be more energy-intensive compared to livestock. Although the term meat continues to be used to indicate the animal origin of the product, it defines a new conceptual line of producing cruelty-free food. Van der Weele and Driessen (11) describe cultured meat as an ethical framework that allows people to continue to consume animal proteins while also having a meaningful relationship with farm animals.

Irrespective of the technological and production advances, a major factor for the adoption of cultured meat is its acceptance by the consumers. There is a large number of factors that shape consumer preferences ranging from sensory experiences to psychological predisposition, health considerations, environmental concerns and marketing influences (12). Age and gender also impact on people's food choices (13). In this study, we explore the attitudes of the young generation of Australians in relation to cultured meat by surveying Generation Z Sydney residents.

There have already been other studies investigating the acceptance of cultured meat in places, such as USA (14, 15) and the Netherlands (16); comparisons have been made between consumers in USA, China and India (17); the USA and the UK (18); and China, Ethiopia and the Netherlands (19). Systematic literature reviews highlight the demographic and geographic variations between consumers (20, 21) as well as the need for further research.

Generation Z

This is the first study to explore the acceptance of cultured meat amongst Australian youth with a specific focus on Generation Z living in Sydney, Australia. Sydney is Australia's best-known iconic city which has a distinctive dynamic and multicultural atmosphere with vibrant cultural and artistic life. It is also Australia's business hub with innovation, knowledge-based industries, services, health and medical care and tourism flourishing. Sydney is consistently being ranked as one of the most liveable cities in the world characterized with economic and population growth as well as numerous opportunities supported by its modern infrastructure and competitive advantages (22). This study explores a particular section of Sydney's population, Generation Z or Gen Z—a demographic cohort following the Millennials (23) and preceding the latest Generation Alpha (24).

Generation Z (born between 1995 and 2010) represents around 20% of the current Australian population or 5 million young people (24). Its share in the world is larger at almost 30% or 2 billion people in 2020 (24). This generation grew up with digital technologies, the Internet and social media. Some argue that Gen Z is defying the reputation of entitlement characteristic for the Millennials, is “prematurely mature” [(25), p. 59] and is already exhibiting qualities, such as social generosity and environmental responsibility (26).

There is a limited number of studies specifically examining the consumer attitudes of this newly emerging world power (23, 25, 27), and particularly around their relationship with meat alternatives and cultured meat (28, 29). Although yet to be properly understood, Gen Z is not only defined by technology but is also the future economic, decision-making, political and social change driving force. They are ready to intervene and break the status quo, charged with a mission of social and environmental responsibility. Most of the knowledge, concepts and ideas this highly technologically advanced and diverse digital generation grasps from the net, exploring the vast opportunities of Google, YouTube and other social media (30). Globally aware and no strangers to social activism, the technologically empowered Gen Z wants to make a difference and to leave a mark of significance.

Gen Z has already demonstrated their strong views about the world, their own future and the need for rethinking the relationships between people and with the planet through the voices of Malala Yousafzai—the Pakistani activist for women's rights, Greta Thunberg—the Swedish environmental activist and climate change campaigner, and Billie Eilish—the American vegan singer-songwriter. This generation wants its voices and opinions to be heard, to be actively engaged in political conversations, to become influencers, to be involved and bring positive changes. They are smart, challenging, adventurous, active decision-makers (25) who are not to be underestimated with their tech-savvy skills and expertise in easily finding information. This generation is armed with learning from humanity's previous missteps, environmentally aware and tends to rally spontaneously behind global causes that resonate with them.

Despite living in a wealthy country with a prosperous economy, Australia's Gen Z is apprehensive about the world and the many environmental problems they are inheriting, with climate change being their biggest concern (31). They however believe in the power of knowledge, research, science and technology with almost half of them (49%) trusting the university sector to deliver solutions for the world's urgent and pressing challenges—a much higher share than amongst their global counterparts (31). From this point of view, it is very interesting how the Australian Gen Z in particular responds to the emerging cultured meat. However, our 2019 survey covered only adult Gen Z representatives who in that year would have been at least 18 years of age as they are already economically independent and can make their own food-related decisions. Hence, the Gen Z sample covered in this research is of Sydney residents born between 1995 and 2001. None of the participants has tasted cultured meat and their responses are based only on perceptions and the information they have had prior to the survey.

Section Materials and Methods outlines the methodology of the study before we present and discuss the results from the qualitative survey carried out in Sydney in 2019. The final section closes the discussion by reflecting on the dynamically changing circumstances that may speed up consumers' decision about cultured meat. Theoretically, the process of cultured meat production could efficiently supply enough products to satisfy the global demand for meat; the reality however will depend on the existing institutional and international arrangements as well as the deployment and availability of infrastructure and the political and socio-economic environment (7). People's attitudes will play a major role in this and the paper provides insights from Sydney's Gen Z.

Materials and Methods

This exploratory survey of adult Gen Z is based on an online questionnaire containing some quantitative and some qualitative questions. We chose to conduct the survey online because of the target group's familiarity with using the internet. The survey offers an opportunity to explore the views of young people using inexpensive, completely voluntary, interactive, without data restrictions and open in nature method. Tailored to the main characteristics of the target population, the research aimed to develop a first-hand understanding about a specific group faced with a particular situation which we believed was worth exploring but about which there was no prior knowledge (32). With Gen Z being the first all-digital generation, we took an open-mind approach without any explicit expectations to try to understand what excites and affects them (33) in relation to cultured meat.

The quantitative part of the questionnaire requested demographic data about the participants while the qualitative components focused on collecting their opinions related to cultured meat. There were five sections in the questionnaire:

(1) Demographic data related to age, gender, employment status, profession, and income level;

(2) Dietary preferences based on frequency of meat consumption, ranging from daily to a few times per week, occasionally and never;

(3) Opinion about cultured meat and whether it is normal and necessary to accept and if available, consume cultured meat;

(4) Preference for different meat alternatives, namely insects, plant-based options and cultured meat;

(5) Factors and reasons which may influence people to embrace new meat alternatives.

All participants were recruited randomly, electronically from a pool of 30,000+ names registered in a database established by the researchers. They used a checkbox on the questionnaire to indicate their informed consent to take part voluntarily in the survey. An ethics approval was obtained from Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. The response rate to the survey was 75% which is relatively high. Such a response rate is considered good to eliminate potential bias from young people who have responded and those who have chosen not to respond (34).

The data gathered from the qualitative sections were in the form of free verbatim comments and direct quotations. As with most qualitative studies, we continued collecting additional data until a saturation of results was achieved, meaning the data no longer provided any further clarity or insights related to the explored topic (35). The collected data were analyzed both manually using researcher discretion and with the help of the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software NVivo11 (36). Frequently occurring expressions and themes were coded to produce manageable categories related to the topic of cultured meat.

Results

Conducted in 2019, this exploratory study of adult Gen Z in Sydney, Australia covered 227 (n = 227) participants born between 1995 and 2001. Below we present the demographic and dietary description of the sample followed by the respondents' opinions about cultured meat.

Description of the Sample

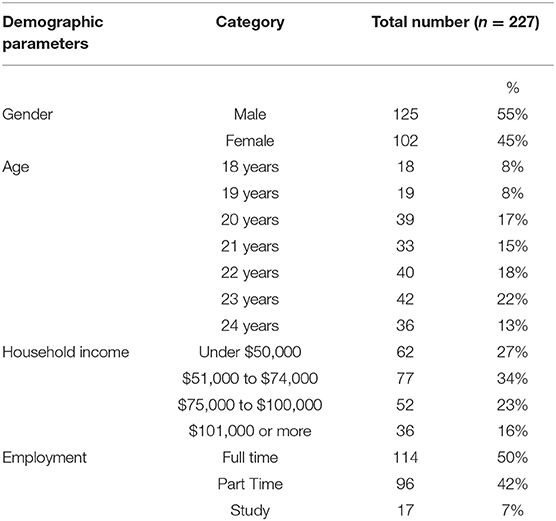

In total, 227 representatives of Sydney adult Gen Z participated in the study through voluntary self-selection (see Table 1). The share of male participants (55% or 125 men) was higher than that of female respondents (45% or 102 women). This gender difference in favor of male participants is relatively small and although it was not deliberate, it was important to capture sufficiently men's views as previous research shows that they more frequently opt for meat options (5). There were no major differences in the opinions presented by the male and female participant groups and therefore, the analysis to follow does not apply a gender lens.

The sample is statistically representative at a 95% confidence level with an acceptable margin of error within 5.2%. Table 1 shows the break-down of the participants by age. The average age of the sample is 21.4 while the median age is slightly higher at 22.

Overall, the sample consists of relatively young adults, the majority of whom have transitioned to being economically independent with 50% being in full-time employment, 42% working part-time and only 7% studying (see Table 1). The average household income of the Sydney adult Gen Z sample is estimated at around $71,000 per annum.

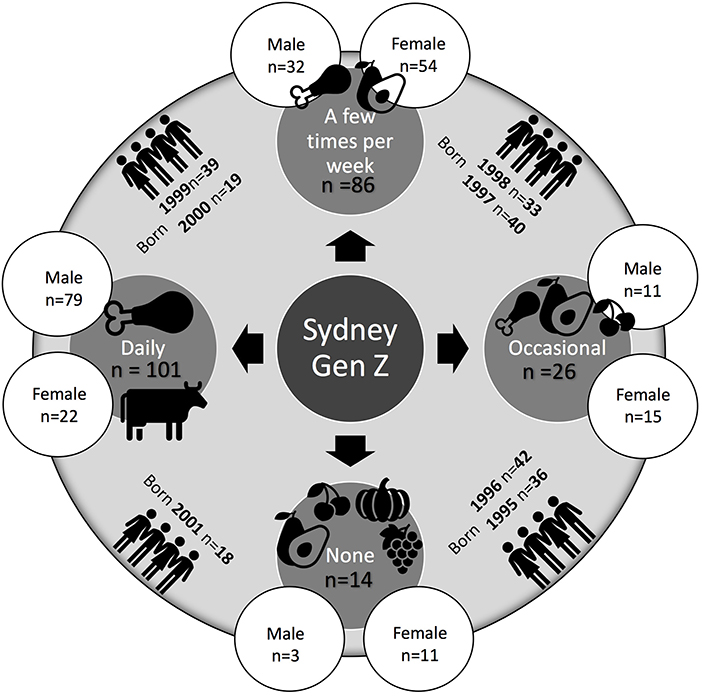

The levels of meat consumption varied significantly amongst the study's participants (see Figure 1). However, there was explicit preference for meat in line with the general trends in Australia which has one of the highest per capita meat consumptions in the world (37). The majority of the respondents, namely 44%, consume meat on a daily basis, followed by those who eat meat a few times per week−38%, occasionally−10%, and never−6%. A 2019 study of the Australian population shows that the food of 12.1% of Australians (or 2.5 million) is all, or almost all, vegetarian (38). Our sample shows a lower percentage of strict vegetarians (6%) but the share of those who eat meat occasionally or have excluded meat completely from their diets, is higher at 16%. Previous research shows that vegetarianism is also constructed as a social category with some vegetarians occasionally consuming meat (39). Hence, a possible explanation for the lower rate of full vegetarianism in our sample is the fact that we asked about frequency of meat consumption rather than how people self-identify. These considerations allow us to conclude that the survey sample is not that different from the overall food trends in Australia.

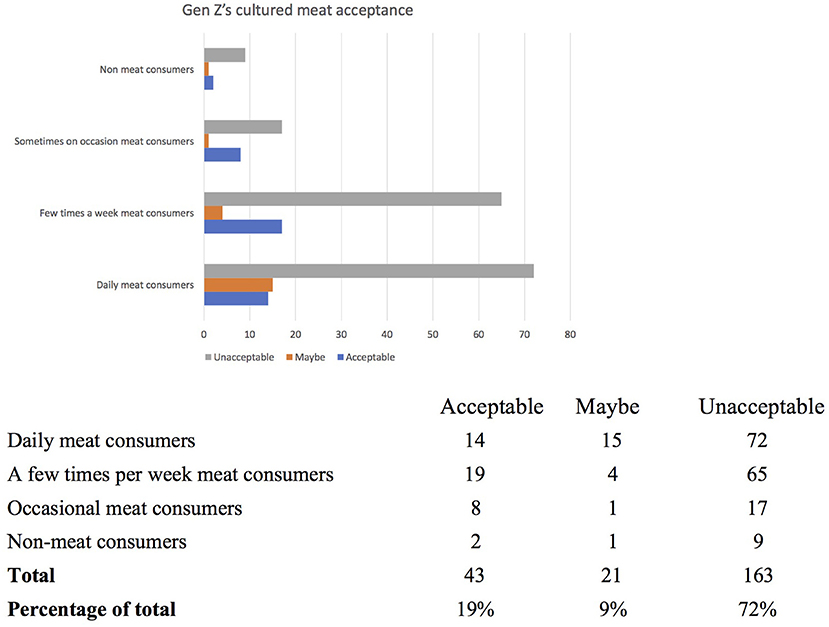

Only 97 participants (or 43% of the sample) believed that there is a need to replace traditional meat with other food alternatives, including plant-based options and cultured meat. This shows a relatively low level of awareness amongst Australian youth about the negative environmental and other impacts of livestock. Furthermore, cultured meat is not seen as an attractive alternative with only 19% (or 43 participants) accepting it as a food option and a further 9% (or 21 people) being hesitant. The remaining 72% (or 163 participants) were categorically of the opinion that cultured meat is not acceptable to them (see Figure 2). What are reasons for these low levels of acceptance of cultured meat are discussed in the qualitative analysis below.

Attitudes Toward Cultured Meat

Concerns dominated Gen Z's attitudes toward cultured meat. They included personal concerns, related to anticipated taste, health and safety, as well as societal considerations related to whether we need to accept the need to consume cultured meat and whether it is more sustainable. Socio-cultural impacts, such as perceptions about masculinity and animal meat being an Australian pride, were also raised. Some were concerned about the animals themselves. Finally, there were those who saw cultured meat as a conspiracy orchestrated by the rich and powerful and were determined not to be convinced to consume it.

This wide range of opinions is discussed below using excerpts verbatim from the survey respondents. It appears that there were overwhelming negative attitudes although some were prepared to give cultured meat a try.

Personal Concerns

Gen Z expressed many personal concerns related to cultured meat. They included disgust about the anticipated taste and eating experience as well as health and safety concerns.

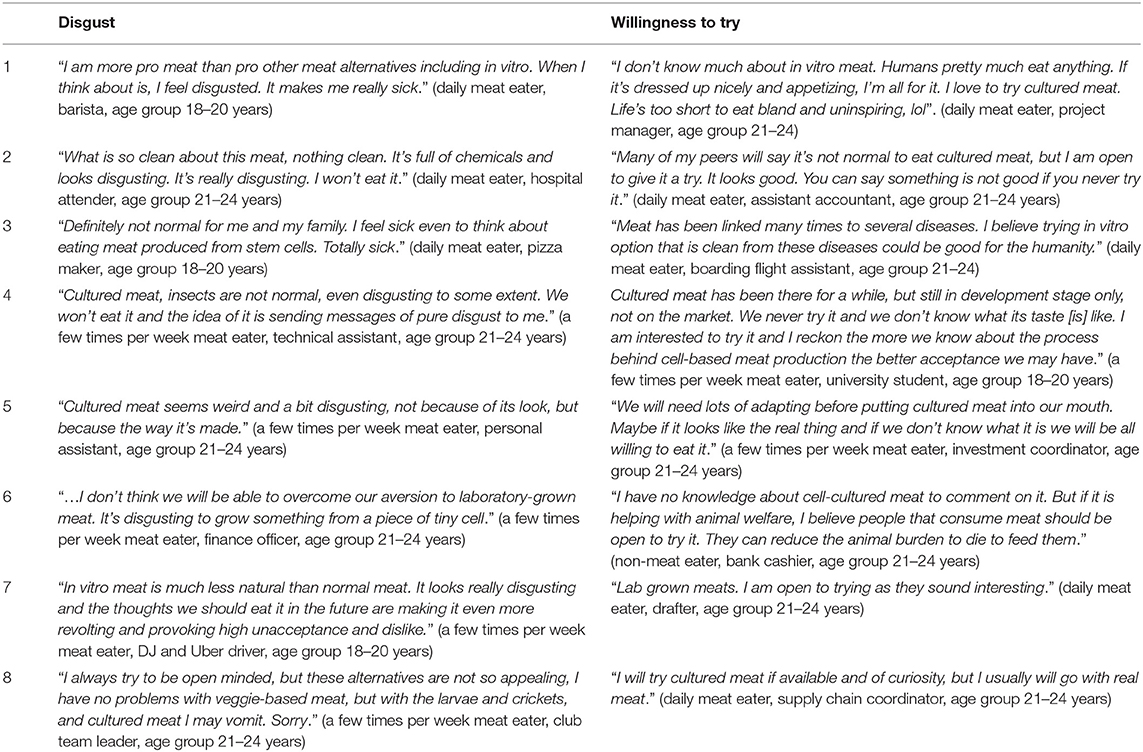

Disgust

When it comes to food, and novel food in particular, people's first reaction is related to the anticipated taste. The study's participants were divided in their reaction. A large majority of the Sydney Gen Z respondents (n = 163, 72%) associate cultured meat with a feeling of uneasiness and discomfort. This is expressed with statements, such as: “It makes me really sick,” “it's really disgusting,” and “I may vomit. Sorry” (see Table 2). Some (n = 64, 28%), however are more intrigued: “I am open to try it,” “if it's dressed up nicely and appetizing” and “the more we know about the process behind cell-based meat production the better acceptance we may have” (see Table 2).

Health and safety

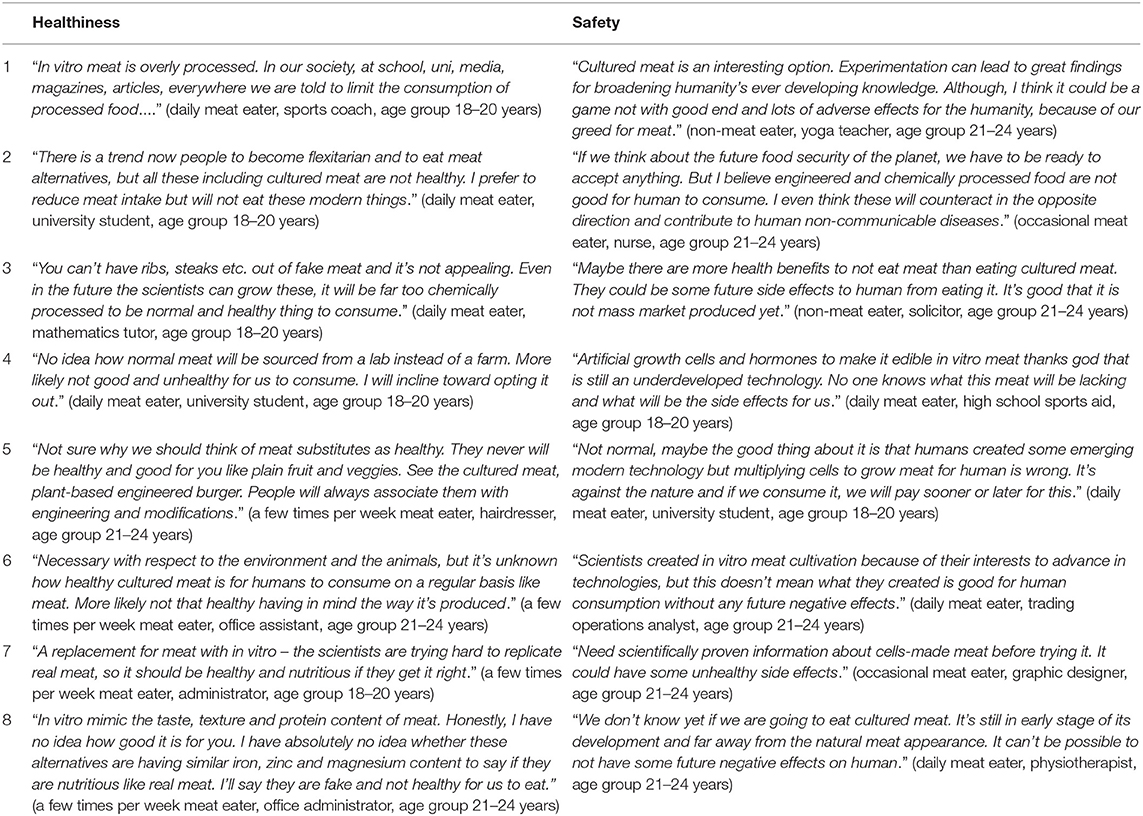

Gen Z is very much nutritionally aware and these young people are committed to healthy eating and wellness (40) while open to exploring new food choices which often were not available to previous generations in Australia. It is not surprising then that the Sydney Gen Z is casting doubts whether cultured meat is a healthy and nutritional dietary option with a third of them (n = 73, 32%) believing this not to be the case. They described cultured meat as being “far too chemically processed,” associated with “engineering and modifications.” Others, however, are of the opinion that “it should be healthy and nutritious if they get it right.” There are also those who frankly admit: “I have absolutely no idea… whether these alternatives… are nutritious like real meat” (see Table 3).

Although sometimes it is difficult to strictly draw the boundary between food quality and food safety, the latter refers to the way the products we consume are being handled and whether there are any negative health consequences from consuming them. Technically, cultured meat is expected to be produced within a clean, sterile and highly controlled environment to prevent any food-related risks. Nevertheless, Gen Z are not convinced that it will be safe for consumers. A major worry for them are the possible unknown “adverse,” “negative,” “hidden side effects” of cultured meat (see Table 3). This resembles some of the concerns expressed in relation to the consumption of insects in our previous study (29).

Societal Concerns

There are two broader societal themes that emerged in the respondents' answers. One is related to food availability and the other to the environmental impacts of the current meat production. This comes against a background where only a third (n = 74, 33%) of the Gen Z participants are willing to change their meat-related behavior, with that share amongst daily meat consumers being much lower (n = 18, 18% of the group of daily meat eaters).

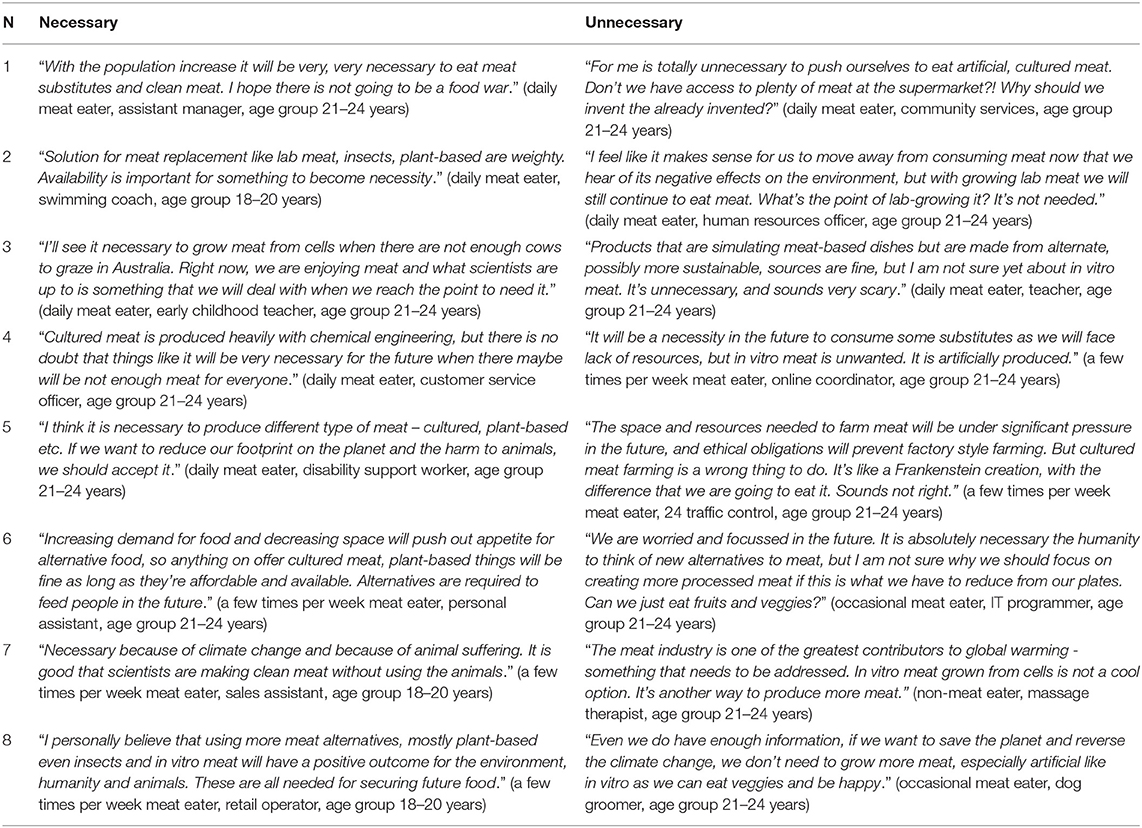

Food availability

When it comes to the question about food availability, opinions within the survey sample were divided. Many (n = 57, 25%) saw the need to accept cultured meat because of population growth or inability to produce enough livestock-based meat. Expressions, such as “not enough meat for everyone” and avoid “a food war” (see Table 4) were used. On the other hand, there were many voices which similarly recognized the need to look at human diet but did not see cultured meat as an option to feed the world or reduce the food's impact on the environment. Examples include: “in-vitro meat is unwanted,” “it's like a Frankenstein creation” and “can we just eat fruits and veggies?” (see Table 4).

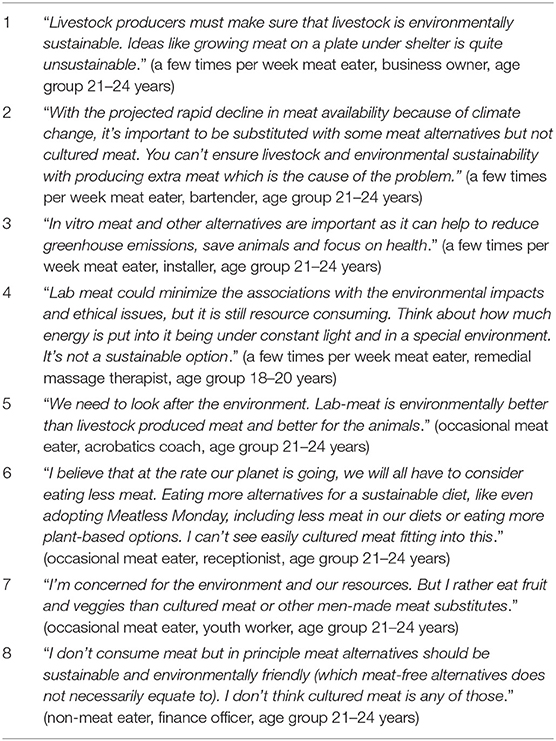

Environmental impacts

The need for switching to meat alternatives and more sustainable food choices was highlighted by a large number of study participants (n = 93, 41%). They were however unsure whether cultured meat is better and was described as “resource consuming” and not being “environmentally friendly” (see Table 5). It is also interesting to note that these concerns were not raised by those who consume meat on a daily basis.

Socio-Cultural Concerns

Two main socio-cultural considerations emerged from the survey. The first is related to the perceptions about masculinity and that meat is the men's choice, while the second is about Australia priding itself as a producer of quality animal-based foods, such as beef.

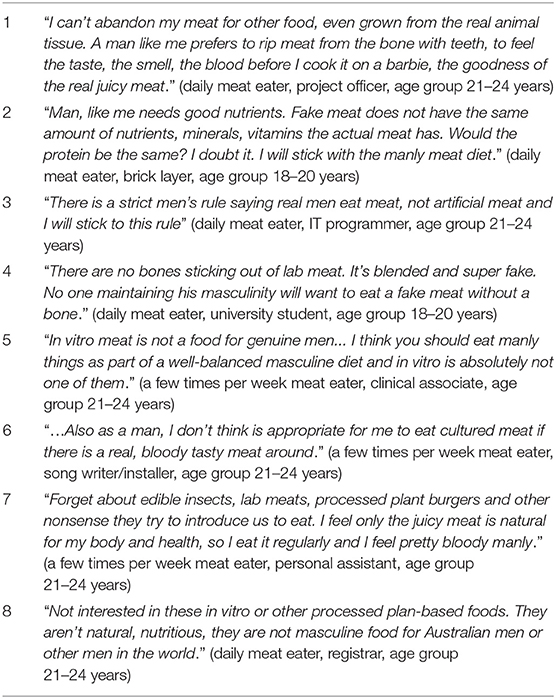

Masculinity

The majority of the male daily and a few times per week meat consumers (n = 58, 52% and n = 58, 26% of the sample) found cultured meat threatening to their manly traits. Similar concerns have been expressed in previous studies (28, 29), indicating that many men are not ready and unwilling to contemplate changing their dietary preferences (5, 41). Table 6 shows the expressions such men use, e.g., “rip meat from the bone,” “real men eat meat,” and “I don't think is appropriate for me to eat cultured meat if there is a real, bloody tasty meat around.”

Australian pride

Pride in Australia being a producer of “superb quality” and “best in the world” meat (see Table 7) where it is widely available and affordable was expressed by some participants (n = 29, 13%). Many stress that “meat is plentiful in Australia” and “we produce lots of good meat the nation is proud of” (see Table 7). These participants see cultured meat as a disloyalty to Australian meat and betrayal of their country.

Concerns About Livestock Animals

Concerns about animal welfare and dignity were expressed by some of the participants in the Sydney study. They saw cultured meat as a way to avoid animal suffering but others also raised concerns that using animal cells for growing meat in a lab is unethical from the point of view of the animal.

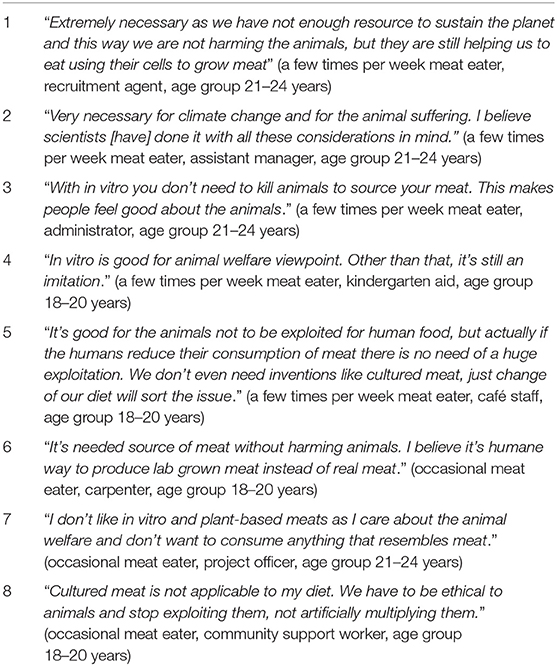

Animal welfare

Improved animal welfare because of a switch to cultured meat was seen as an advantage by some participants (n = 37, 16%). They described this as “this way we are not harming the animals,” “stop exploiting them” (see Table 8). Such voices were raised mainly by those who consume meat less frequently.

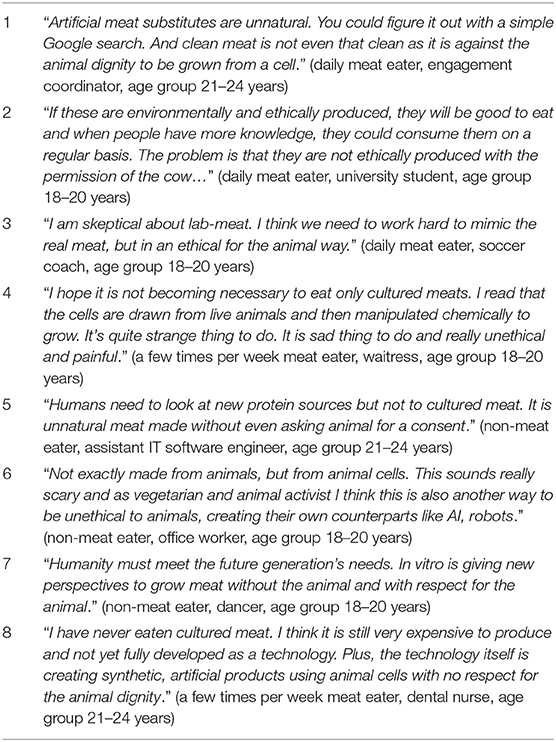

Animal dignity

Another interesting nuance of the ethical use of animals for food production was the issue about animal dignity raised by some participants (n = 26, 11%). These participants represented different dietary practices and they spoke about “the permission of the cow” to use its cells, being “really unethical and painful” (see Table 9).

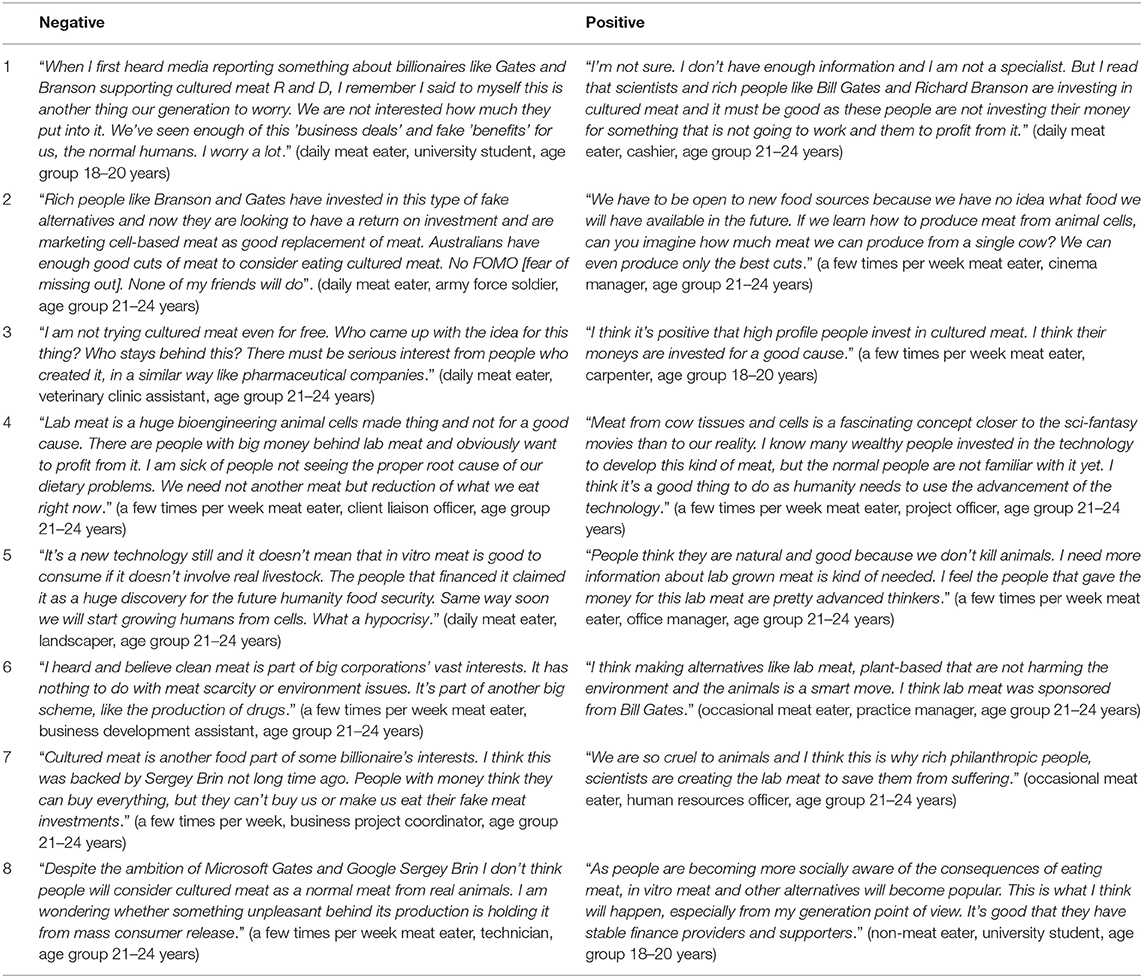

Conspiracy Concerns

Concerns were raised by Gen Z whether cultured meat is part of some hidden agenda, including those who have funded its development wanting to see return on their investment. The participants were divided in two groups—pro and against the sponsors of cultured meat (see Table 10). Those who are against the development of cultured meat describe this as “another thing our generation to worry” and explain that “there must be serious interest from people who created it.” By comparison, those who support this innovation describe it as “money… invested for a good cause,” “a smart move” by people who are “pretty advanced thinkers.”

The Future of Cultured Meat

The respondents were also asked their opinion about the future place of cultured meat in human diets through three different perspectives: first, how they see its future; second, in relation to other meat alternatives; and third, what would make them accept alternatives to traditional animal meat. Their answers are presented in turn below.

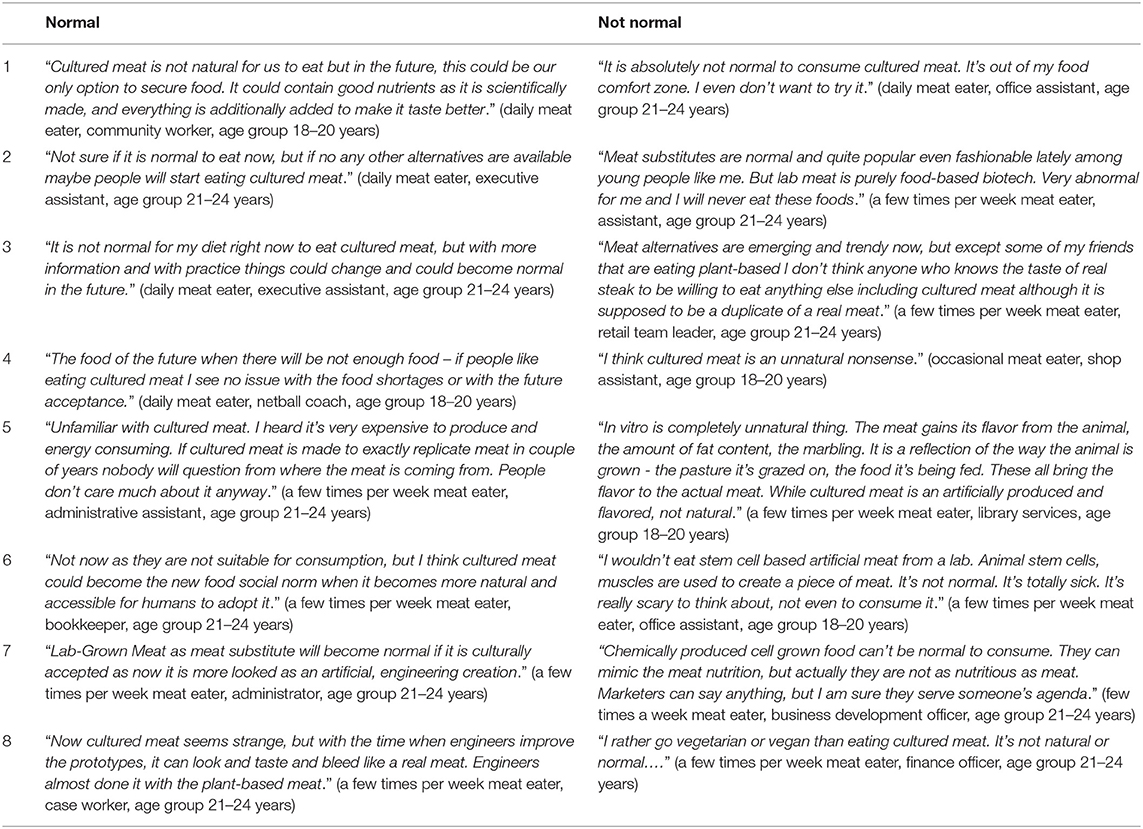

Prospects for Cultured Meat

Lack of information about the way cultured meat is created, the substrates and the processes used combined with it not being yet available in Australia, was making it an undesirable food option for many of the respondents (n = 103, 45%). This was an interesting observation given the fact that Gen Z is accustomed to be using the web for communication and thrives in the social media. A further large group (n = 88, 39%) was indecisive about the future of cultured meat. The remaining participants (n = 36, 16%) saw a good value in cultured meat, believing that if it is done right it could work and become one of the “future food trends.” Table 11 presents some examples of the way the participants described cultured meat becoming a normal food choice or continuing to be perceived as abnormal, unnatural and “produced against nature.”

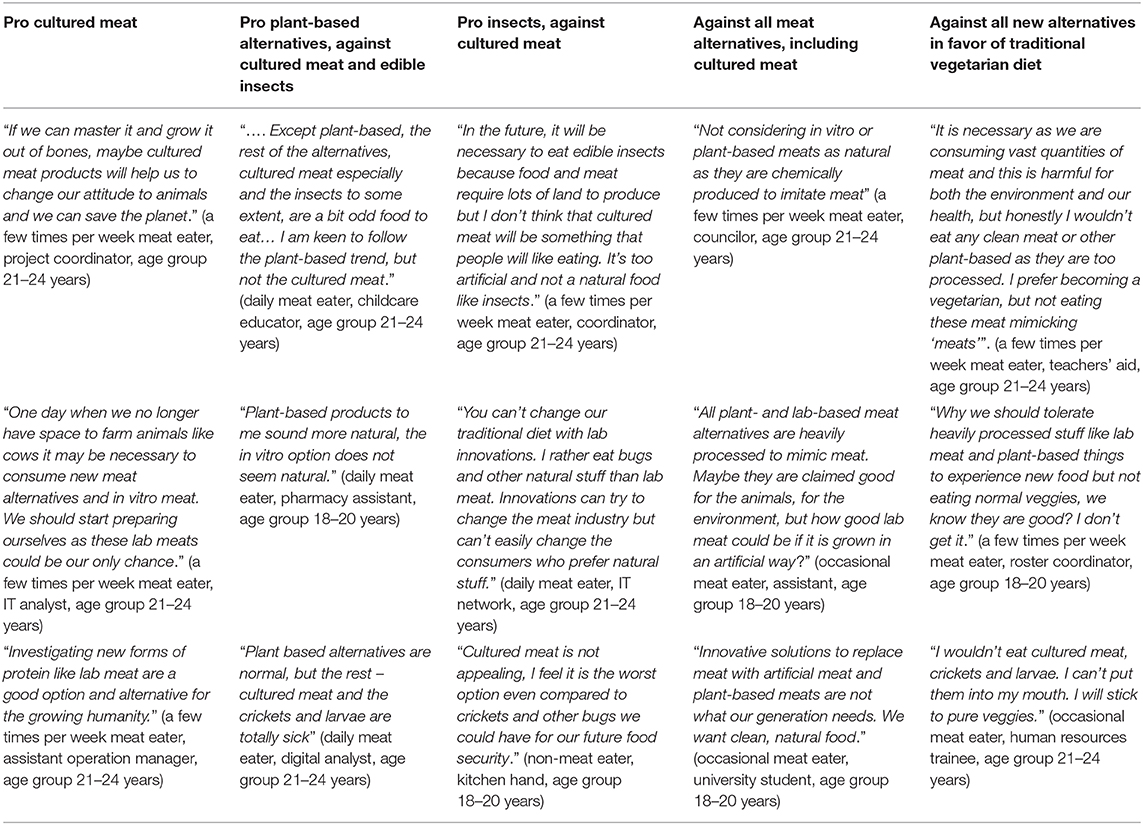

Cultured Meat vs. Other Alternatives

When asked to express their opinion about different alternatives to livestock-based meat, namely edible insects, plant-based meat and cultured meat, according to their acceptance and preferences, the Gen Z participants were divided into five groups (see Table 12). One of the groups (n = 38, 17%) rejected all alternatives, including cultured meat. They were seen as “chemically produced,” “heavily processed,” and “not what our generation needs.” Another group (n = 25, 11%) rejected all alternatives in favor of increased consumption of fruit and vegetables: “I will stick to pure veggies” and “why… not eating normal veggies, we know they are good.” A larger group (n = 79, 35%) rejected cultured meat and edible insects but accepted plant-based alternatives because they “sound more natural” and are “normal.” Cultured meat was acceptable or possibly acceptable to the fourth group (n = 64, 28%) “if we can master it” as this will be “new forms of protein.” The fifth group (n = 21, 9%) accepted edible insects but rejected cultured meat because “it's too artificial and not a natural food like insects” and “innovations can try to change the meat industry but can't easily change the consumers who prefer natural stuff.”

Embracing Meat Alternatives

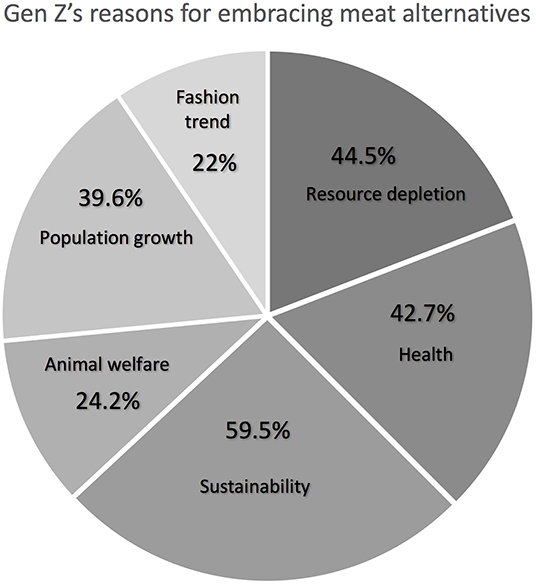

What could make Gen Z embrace alternatives to traditional animal meat, including cultured meat, is an important question related to the future of food. The question allowed multiple choices and Figure 3 presents the frequencies for each indicated answer. Broader sustainability concerns, including environmental impacts and contribution to climate change, was the most preferred answer (59%, n = 135), followed by specifically resource depletion (44%, n = 101). Other reasons are: health concerns (43%, n = 97), population growth (40%, n = 90), animal welfare (24%, n = 55), and fashion trend (22%, n = 50). These results confirm that Gen Z is concerned about the natural environment and is likely to adopt an eco-friendlier lifestyle (42).

Discussion

Some of the findings from this exploratory study of adult Sydney Gen Z were expected and in line with previous research while others are unexpected. They all offer insights into this new generation and potential consumers of novel foods.

Sydney Gen Z's attitudes are very similar to the consumers' concerns in the West summarized by Bryant and Barnett (20) when it comes to the unnaturalness, safety, healthiness, anticipated taste and appearance of cultured meat. The residents of the largest Australian multicultural metropolis are used to a diversity of food options but the artificial and technology-based nature of cultured meat is making it difficult for the majority of them to accept this as a future choice in their diets. Some of their objections are grounded in the lack of sufficient information, but also in the almost instinctive feeling of disgust—a food-related emotion which plays a major role in building cognitive-affective linkages that guide behavior (43).

A 2020 study conducted in USA (44) shows a much higher acceptance of cultured meat amongst general consumers than what Sydney Gen Z indicates. Assuming that the price of cultured meat is the same as animal-based meat, 53% of the American consumers are prepared to make the substitution. Price considerations do not appear to be of any concern to Sydney's young adults but still only 28% of them consider cultured meat acceptable. Furthermore, 56% of the American consumers are prepared to substitute farmed meat for plant-based alternatives (44), while this percentage is lower at 35% for Sydney's Gen Z. These comparisons however should be treated with caution as the surveys conducted in the US and Australia use different descriptions of cultured meat, as well as different question formats, which can affect the responses.

Another study conducted in the USA shows that younger people in particular are more inclined to try cultured meat with 51% of those aged between 18 and 29 willing to do so (45). This share is again much lower at 28% amongst the Sydney Gen Z. A study in Germany (46) shows that children and adolescents are more willing to consume a burger made of cultured meat than of insects but it also confirmed the negative influence of neophobia. Similar attitudes were also manifested among the participants in our survey; however the feeling of disgust was quite pronounced in Australia whilst missing in Germany.

Cultural dimensions related to perceptions about masculinity and Australia's pride in producing high-quality animal meat products, are adding additional weight to the objections Gen Z has against alternatives to farmed meat. Although they do not explicitly express any considerations specifically about farmers (20, 47) or concerns about how farmed meat is produced (48), the way others have done previously, Gen Z seems to value Australia's reputation about being a supplier of quality livestock-based meat.

In 2019, many Gen Z students and young people actively participated in the climate strikes in Sydney raising their voices against greenhouse gas emissions, continuing deforestation and biodiversity loss. The issue about meat consumption was not part of the activists' agenda despite ample scientific evidence about the livestock's high environmental footprint. It seems that Gen Z has not been exposed enough to reliable information about farming practices in Australia, such as the use of antibiotics in poultry farms and the ecological footprint of the Australian beef. Only 41% express environmental concerns associated with the way meat is being currently produced. It is therefore important to educate young people about the environmental impact of farmed meat production.

If cultured meat is to replace livestock-based proteins, it will have to emotionally and intellectually appeal to the Gen Z consumers. It may be through its physical appearance, but what seems to be more important is transparency about its environmental and other benefits.

This generation has vast information at its fingertips, but is still concerned that they will be left with the legacy of exploitative capitalism that benefits only a few at the expense of many. They have witnessed such behavior resulting in climate change and are now afraid that a similar scenario may develop in relation to food, particularly as investors are pursuing broader adoption (48). The conspiracy theory identified as a major concern in relation to edible insects (29), also rings alarm bells in the case of cultured meat. Conspiratorial ideation related to rejection of cultured meat was also identified in the study by Wilks et al. (49).

With the exception of 19% (n = 43), the remaining participants did not share proper conceptual knowledge about the way cultured meat is made. As explained by Madden (30, p. 193), this characteristic is a result of Gen Z being “brokers of information rather than knowers of content.” They value the opportunity to access current information when needed, but not memorizing the content for future use. In this sense, it is likely that when cultured meat becomes available at the Australian market, Gen Z will start looking for answers in order to understand the “why” behind the “what” (30).

Devoted to their true technological nature some of the participants find fascinating the technological advancement of humanity to create in-vitro meat. They also see this as an opportunity to prevent further animal suffering and reduce the environmental impacts of livestock production. This generation appears to be opening the door to the miracles of technology for the achievement of broader societal benefits with 28% (n = 64) already accepting cultured meat. Focussing on the benefits of the final product, not the way it is produced (50), may increase acceptance.

Shaped with increased global awareness, Gen Z is particularly cautious about the impact of their product choices. What matters the most is the ethical side of production (30) and this was demonstrated through their concerns about animal dignity in the process of cultured meat. If the produced outcomes are environmentally and ethically good, it will be worth considering.

The participants indicated that they do not have a “fear of missing out” (30) when it comes to cultured meat. They do not prioritize concerns about establishing competitive advantages, the anticipated price of cultured meat or whether the process will be properly regulated and controlled. Living in a prosperous and stable economic environment with ample food availability, Sydney Gen Z values higher its freedom of choice, be it to opt for the traditional fruit and vegetables, than being the early innovators.

These young adults have also been exposed to the Covid-19 pandemic which is challenging human relationships with food from different angles (51). Large sections of natural habitat have been destroyed for the purpose of producing meat and growing animal feed, threatening further the survival chances of thousands of species. As our respondents indicated, many people are likely to seriously consider the environmental impacts of their food choices and opt for better options. Ironically, during the spread of the pandemic many abattoirs, meat and poultry plants in Australia and around the world became clusters for coronavirus cases (52). Cultured meat may soon be perceived as safer and not posing health risks, because it is produced in a virus-free sterile environment where no antibiotics are used. When faced with such choices, people may soon find the cultured meat decision more attractive.

While the future of cultured meat is still hanging in the balance, Gen Z consumers are similarly in the waiting. They are also open to be convinced. Being an exploratory qualitative study, it provides new insights about a demographic population that has not been studied previously and opens up opportunities for further statistically significant explorations.

Conclusion

According to Stephens et al. (7), whether cultured meat would really become clean, ethical and with a low environmental impact will depend on the efficiency of the production processes and the motivations of the companies and their funders. For the time being, Gen Z is not ready to embrace cultured meat with 72% finding it not acceptable. Emotional feelings of disgust dominate their individual attitudes toward the anticipated taste of cultured meat. Many are prepared to opt for plant-based meat alternatives and even the traditional fruit and vegetables instead. Australia's Gen Z is not concerned about the price, regulations or controls surrounding cultured meat, however some doubt the motivation behind investing in these technological developments. A major concern for Gen Z are the healthiness of cultured meat and its unnaturalness with 32% being of the opinion that it is not a healthy option.

Nevertheless, 28% of Gen Z are prepared to try cultured meat and some (25%) find it an option which can help with population growth. As 41% already acknowledge the need to switch to more sustainable food choices, further information related to the environmental implications, animal welfare and health impacts of farming livestock may sway these young people's opinion. Any persuasion however should be logical, with a clear purpose and no hidden messages as Gen Z are independent thinkers, conscientious about their food choices and prefer to find the answers themselves. Being digitally savvy and highly connected, they will also have to address the challenges the previous generations have thrown at them, including climate change, environmental health and new emerging zoonotic diseases.

It is not surprising that Gen Z's value system is penetrating its food choices. As each generation makes its mark on the world, it may well be that Gen Z is the one putting cultured meat to the test and deciding its future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Curtin University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

DB and DM conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and contributed equally to all the sections in the article. DB conducted the survey. All authors made substantial contributions throughout all sections, read, and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 227 participants in the survey who gave up their time and expressed their thoughts on a voluntary basis without any monetary compensation. The comments from the reviewers helped us improve the quality of the manuscript for which we are very thankful.

References

1. Raphaely T, Marinova D. Flexitarianism: a more moral dietary option. Int J Sustain Soc. (2014) 6:189–211. doi: 10.1504/IJSSOC.2014.057846

2. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In: Díaz S, Settele J, Brondízio ES, Ngo HT, Guèze M, Agard J, et al., editors. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat (2019).

3. Albeck-Ripka L. Protests in Australia pit vegans against farmers. New York Times. (2019) Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/10/world/australia/vegans-protest-farms.html (accessed May 31, 2020).

4. Cave D, Albeck-Ripka L. Why is Australia trying to shut down climate activism? New York Times. (2019) Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/06/world/australia/australia-climate-protests-coal.html (accessed May 31, 2020).

5. Bogueva D, Marinova D. Reconciling not eating meat and masculinity in the marketing discourse for new food alternatives. In: Bogueva D, Marinova D, Raphaely T, Schmidinger K, editors. Environmental, Health and Business Opportunities in the New Meat Alternatives Market. Hershey, PA: IGI Global (2019). p. 260–82.

6. Phillips CJC, Wilks M. Is there a future for cattle farming? In: Bogueva D, Marinova D, Raphaely T, Schmidinger K, editors. Environmental, Health and Business Opportunities in the New Meat Alternatives Market. Hershey, PA: IGI Global (2019). p. 239–59.

7. Stephens N, Sexton AE, Driessen C. Making sense of making meat: key moments in the first 20 years of tissue engineering muscle to make food. Front Sustain Food Syst. (2019) 3:45. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00045

8. Schmidinger K, Bogueva D, Marinova D. New meat without livestock. In. Bogueva D, Marinova D, Raphaely T, editors. Handbook of Research on Social Marketing and Its Influence on Animal Origin Food Product Consumption. Hershey, PA: IGI Global (2018). p. 344–61.

9. Alexander P, Brown C, Arneth A, Dias C, Finningan J, Moran D, et al. Could consumption of insects, cultured meat or imitation meat reduce global agricultural land use? Global Food Secur. (2017) 15:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.04.001

10. Mattick CS, Landis AE, Allenby BR, Genovese NJ. Anticipatory life cycle analysis of in vitro biomass cultivation for cultured meat production in the United States, Environ. Sci Technol. (2015) 49:119411–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01614

11. Van der Weele C, Driessen C. Emerging profiles for cultured meat; ethics through and as design. Animals. (2013) 3:647–62. doi: 10.3390/ani3030647

12. Marinova D, Bogueva D. Planetary health and reduction in meat consumption. Sustain Earth. (2019) 2:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s42055-019-0010-0

13. Westenhoefer J. Age and gender dependent profile of food choice. Forum Nutr. (2005) 57:44–51. doi: 10.1159/000083753

14. Wilks M, Phillips C. Attitudes to in vitro meat: a survey of potential consumers in the United States. PLOS ONE. (2017) 12:e0171904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171904

15. Bryant C, Dillard C. The impact of framing on acceptance of cultured meat. Front Nutr. (2019) 6:103. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00103

16. Rolland NCM, Markus CR, Post MJ. The effect of information content on acceptance of cultured meat in a tasting context. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0231176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231176

17. Bryant C, Szejda K, Parekh N, Desphande V, Tse B. A survey of consumer perceptions of plant-based and clean meat in the USA, India, and China. Front Sustain Food Syst. (2019) 3:11. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2019.00011

18. Surveygoo. Nearly One in Three Consumers Willing to Eat Lab-Grown Meat, According to New Research. (2018) Available online at: https://www.datasmoothie.com/@surveygoo/nearly-one-in-three-consumers-willing-to-eat-lab-g/ (accessed May 31, 2020).

19. Bekker GA, Toby H, Fischer ARH. Meet meat: An explorative study on meat and cultured meat as seen by Chinese, Ethiopians and Dutch. Appetite. (2017) 114:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.009

20. Bryant C, Barnett J. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: a systematic review. Meat Sci. (2018) 143:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.04.008

21. Animal Charity Evaluators. A Systematic Review of Cell-Cultured Meat Acceptance. (2020) Available online at: https://animalcharityevaluators.org/research/other-topics/a-systematic-review-of-cell-cultured-meat-acceptance/#full-report (accessed May 31, 2020).

22. Sydney Business Chamber. Priorities. (2017) Available online at: https://www.thechamber.com.au/Advocacy/Priorities (accessed June 1, 2020).

23. Dimock M. Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins. Pew Research Centre (2019). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ (accessed June 1, 2020).

24. Mccrindle. Characteristics of the Emerging Generations. (2020) Available online at: https://mccrindle.com.au/insights/blogarchive/gen-z-and-gen-alpha-infographic-update/ (accessed June 1, 2020).

25. Singh A. Challenges and issues of Generation Z, IOSR J. Bus Manag. (2014) 16:59–63. doi: 10.9790/487X-16715963

26. The Atlantic. Getting Gen Z Primed to Save the World. (2019) Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/allstate/getting-gen-z-primed-to-save-the-world/747/ (accessed June 1, 2020).

27. Madden C. Hello Gen Z: Engaging the Generation of the Post-Millennials. Revised ed. Sydney, NSW: Hello Clarity (2019).

28. Bogueva D, Schmidinger K. Normality, naturalness, necessity and nutritiousness of the new meat alternatives. In: Bogueva D, Marinova D, Raphaely T, Schmidinger K, editors. Environmental, Health and Business Opportunities in the New Meat Alternatives Market. Hershey, PA: IGI Global (2019). p. 20–37.

29. Sogari G, Bogueva D, Marinova D. Australian consumers' response to insects as food. Agriculture. (2019) 9:108. doi: 10.3390/agriculture9050108

30. Madden C. Hello Gen Z: Engaging the Generation of Post-Millennials. Sydney, NSW: Hello Clarity (2017).

31. Deloitte. Generation MillZ: What Australian Millennials and Gen Z Are Really Thinking. (2019) Available online at: https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/media-releases/articles/generation-millz-australian-millennials-gen-z-thinking-200519.html (accessed June 1, 2020).

33. Schutt RK. Investigating the Social World, The Process and Practice of Research, 7th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2012).

35. Faulkner SL, Trotter SP. Data Saturation. (2017) Available online at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0060 (accessed June 1, 2020).

36. NVivo11. Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 11, QSR International Pty Ltd. Melbourne, VIC (2017).

37. OECD Data. Meat Consumption. (2020) Available online at: https://data.oecd.org/agroutput/meat-consumption.htm (accessed June 2, 2020).

38. Roy Morgan. Rise in Vegetarianism Not Halting the March of Obesity. (2019) Available online at: http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7944-vegetarianism-in-2018-april-2018-201904120608 (accessed June 2, 2020).

39. Rosenfeld DL, Tomiyama AJ. When vegetarians eat meat: why vegetarians violate their diets and how they feel about doing so. Appetite. (2019) 143:104417. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104417

40. Carter CM. The Business of Feeding Health-Conscious Gen Z and Alpha Children. (2017) Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinecarter/2017/10/29/the-business-of-feeding-health-conscious-gen-z-and-alpha-children/#3d36bba26b28 (accessed June 5, 2020).

41. Bogueva D, Marinova D. What is more important – perception of masculinity or personal health and the environment? In: Bogueva D, Marinova D, Raphaely T, editors. Handbook of Research on Social Marketing and Its Influence on Animal Origin Food Product Consumption. Hershey, PA: IGI Global (2018). p. 148–62.

42. Robbins R. Engaging gen zers through academic advising. Academic Advising Today. (2020) 43. Available online at: https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Engaging-Gen-Zers-Through-Academic-Advising.aspx (accessed August 15, 2020).

43. Rozin P, Fallon AE. A perspective on disgust. Psychol Rev. (1987) 94:23–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.1.23

44. Sentience Institute. Survey of US Attitudes Towards Animal Farming and Animal-Free Food. (2020) Available online at: https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/animal-farming-attitudes-survey-2017 (accessed June 6, 2020).

45. Johnson W, Maynard A, Kirshenbaum S. Consumers Aren't Necessarily Sold on ‘Cultured Meat'. The Conversation (2018). Available online at: https://theconversation.com/would-you-eat-meat-from-a-lab-consumers-arent-necessarily-sold-on-cultured-meat-100933 (accessed June 5, 2020).

46. Dupont J, Fiebelkorn F. Attitudes and acceptance of young people toward the consumption of insects and cultured meat in Germany. Food Qual Prefer. (2020) 85:103983. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103983

47. Shaw E, Iomaire MMC. A comparative analysis of the attitudes of rural and urban consumers towards cultured meat. Br Food J. (2019) 121:1782–800. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-07-2018-0433

48. Wilks M. Cultured Meat Seems Gross? It's Much Better Than Animal Agriculture. The Conversation (2019). Available online at: https://theconversation.com/cultured-meat-seems-gross-its-much-better-than-animal-agriculture-109706 (accessed June 6, 2020).

49. Wilks M, Phillips CJ, Fielding K, Hornsey MJ. Testing potential psychological predictors of attitudes towards cultured meat. Appetite. (2019) 136:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.01.027

50. Siegrist M, Sütterlin B, Hartmann C. Perceived naturalness and evoked disgust influence acceptance of cultured meat. Meat Sci. (2018) 139:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.02.007

51. Bogueva D, Marinova D. Influencing dietary changes in a zoonotic disease crisis. Mov Nutr Health Dis. (2020) 4:70–2. doi: 10.5283/mnhd.27

52. Clean Meat News Australia. Alternative Meat is Having a Moment. Real Meat May Be Done Sooner Thank You Think. (2020) Available online at: https://www.cleanmeats.com.au/2020/05/11/alternative-meat-is-having-a-moment-real-meat-may-be-done-sooner-thank-you-think/ (accessed May 31, 2020).

Keywords: cultured meat, disgust, environmental, Gen Z, masculinity, meat alternatives, sustainability, Sydney

Citation: Bogueva D and Marinova D (2020) Cultured Meat and Australia's Generation Z. Front. Nutr. 7:148. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00148

Received: 06 June 2020; Accepted: 23 July 2020;

Published: 08 September 2020.

Edited by:

Johannes le Coutre, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Christopher John Bryant, University of Bath, United KingdomJavier Carballo, University of Vigo, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Bogueva and Marinova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diana Bogueva, ZGlhbmEuYm9ndWV2YUBzeWRuZXkuZWR1LmF1

Diana Bogueva

Diana Bogueva Dora Marinova

Dora Marinova