95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol. , 30 March 2023

Sec. Microorganisms in Vertebrate Digestive Systems

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1153269

This article is part of the Research Topic Gastric Microbiota Dysbiosis and Gastric Diseases View all 9 articles

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is one of the most common causes of gastric disease. The persistent increase in antibiotic resistance worldwide has made H. pylori eradication challenging for clinicians. The stomach is unsterile and characterized by a unique niche. Communication among microorganisms in the stomach results in diverse microbial fitness, population dynamics, and functional capacities, which may be positive, negative, or neutral. Here, we review gastric microecology, its imbalance, and gastric diseases. Moreover, we summarize the relationship between H. pylori and gastric microecology, including non-H. pylori bacteria, fungi, and viruses and the possibility of facilitating H. pylori eradication by gastric microecology modulation, including probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, synbiotics, and microbiota transplantation.

The stomach was historically assumed to be a sterile organ due to its acidic pH and peristaltic movement. However, this assumption was corrected with the discovery of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), which is a gram-negative bacterium that mainly colonizes the human stomach (Marshall and Warren, 1984). Although the majority of H. pylori-infected individuals remain asymptomatic, chronic infections are strongly correlated with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer diseases, gastric cancer (GC), and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (Peek and Blaser, 2002; Tsai and Hsu, 2010; Wang et al., 2014). H. pylori infections are also associated with extragastrointestinal (GI) diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, iron-deficiency anemia, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (Santos et al., 2020). H. pylori colonization and pathogenesis are influenced by multiple factors, including urease, adhesins, outer membrane proteins, neutrophil-activating protein A, cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), vacuolar cytotoxin A (VacA), and the type IV secretion system (T4SS) (Kronsteiner et al., 2016). With the success of eradication regimens and improvements in sanitation, the prevalence of H. pylori is decreasing worldwide, especially in developed countries (Burucoa and Axon, 2017; Hooi et al., 2017). However, a substantial drop in H. pylori treatment efficacy has been noted due to increasing antibiotic resistance, making the development of new treatment strategies crucial (Megraud et al., 2021; Tshibangu-Kabamba and Yamaoka, 2021).

The microbiome is a complex microbial community comprising bacteria, fungi, and viruses residing in distinct human body habitats with strong niche specialization (Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012). Molecular technologies, such as whole genome 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing and metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics studies (Barra et al., 2021), have provided a better understanding of the gastric microenvironment. The gastric niche is modulated by various factors, including diet, antibiotics, histamine type 2 (H2) antagonists, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), probiotics, and H. pylori infection (Sterbini et al., 2016; Brawner et al., 2017). H. pylori and other microbial communities have complex interactions within the unique gastric microecological environment. This review focuses on the relationship between H. pylori and other microorganisms.

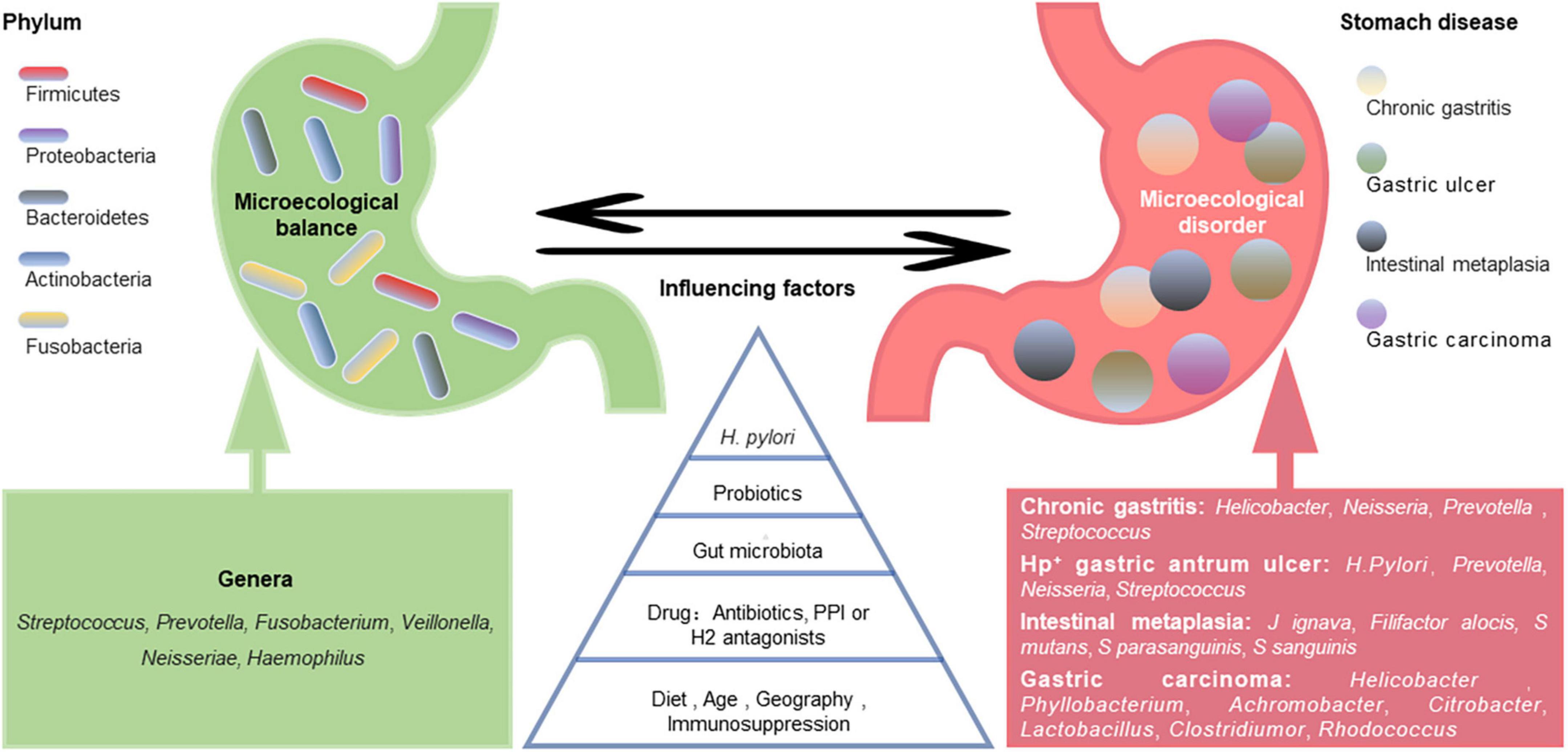

A healthy stomach is colonized by diverse microbiota. Large differences in gastric microbiota composition among individuals have been observed. Bacterial communities in healthy stomachs have not been extensively characterized. However, studies have found that Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Fusobacteria are the most prominent phyla in gastric mucosa (Bik et al., 2006), and Streptococcus, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Veillonella, Neisseria, and Haemophilus are the most prevalent genera (Bik et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009; Delgado et al., 2013; Engstrand and Lindberg, 2013; Ndegwa et al., 2020; Figure 1). Compared with those in the gastric mucosa, H. pylori and Proteobacteria levels were relatively decreased in gastric fluid, while Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes were increased (Sung et al., 2016). It should be noted that gastric fluid samples showed higher diversity than gastric mucosa samples. However, bacteria in gastric juice may be transient since the stomach is exposed to bacterial influx from the oral cavity and reflux via the duodenum (Nardone and Compare, 2015).

Figure 1. Gastric microecological imbalance and gastric diseases. Despite the differences among individuals, there are five dominant bacterial phyla in the healthy stomach, and their common dominant bacterial genera are summarized (green). The gastric microbiota is dynamically balanced and affected by many factors, such as Helicobacter pylori infection, probiotics, gut microbiota, drugs, diet, and age. Although the causal relationship between them is unclear, gastric microecological imbalances are associated with various gastric diseases (red), and some microorganism-related disorders are listed.

The gastric microbiota composition is highly dynamic, as it changes with H. pylori infection, antibiotic exposure, probiotic consumption, PPI or H2 antagonist use, dietary habits, age, vitamin supplementation (especially D3), immunosuppression, and potentially geography and gut microbiota (Espinoza et al., 2018; Figure 1). A long-term follow-up study of H. pylori-negative individuals without atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia (IM) showed that microbial diversity and Firmicutes and Fusobacteria abundances decreased while Proteobacteria phylum abundance increased with age (Shin et al., 2020). However, another study showed that age and sex did not significantly affect the bacterial composition of the stomach (Li et al., 2017). Some ethnicities have specific microbiota profiles. For example, Micrococcus luteus and Sphingomonas yabuuchiae were significantly associated with the Timor and Papuan ethnicities, respectively, (Miftahussurur et al., 2020). A cross-sectional study focusing on minority ethnic groups in Vietnam showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in Nung living in Daklak than in Lao Cai (Binh et al., 2018). Das et al. (2017) found that while the microflora of samples from the USA and Colombia were similar, those from India and China appeared closer. The differences in gastric flora among individuals of different ethnicities or regions may be partly related to their dietary habits. China is a country with high salt intake, which is twice the value recommended by the WHO (Zhang et al., 2020). A high-salt diet primarily changes the composition of the gastric microbiota by reducing the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria at the phylum level and decreasing the relative abundances of Unclassified_S24-7 and Lactobacillus at the genus level (Li Y. et al., 2020).

The establishment and stability of the gastric microecology is attributed to the mucus barrier, biological barrier and immune system. The mucus layer establishes a pH gradient, with a pH of 1–2 in the gastric lumen and 6–7 at the mucosal surface (Bhaskar et al., 1992). The gastric juice-derived bacteria and their DNA develop a barrier to weaken most bacterial colonization, while the bacteria adhering to the mucosa create a more hospitable environment for colonization (Hunt et al., 2015). The gastric innate and adaptive immune responses maintain microbial balance through the immune homeostasis mechanism. Recent evidence has shown that the reciprocal interaction between the type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) and commensal microbiota of the stomach maintains the homeostasis of the microbial environment (Satoh-Takayama et al., 2020).

Altered gastric microbiota composition and function are considered gastric ecological disorders and can be induced by various environmental factors. Microecological disorders can cause gastric immune dysfunction, decrease dominant bacteria, and increase the abundance and virulence of pathogenic microorganisms, leading to pathogenic bacterial invasion and related diseases (Figure 1). Compared with H. pylori-infected germ-free (GF) INS-GAS mice, H. pylori-infected specific pathogen-free (SPF) INS-GAS mice developed more severe gastric lesions and earlier GI intraepithelial neoplasia (Lofgren et al., 2011). This finding supports the view that the gastric microbiota may contribute to gastric disease following H. pylori infection.

Hypochlorhydria patients have many urease-positive bacteria other than H. pylori, such as Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, Haemophilus, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus (Brandi et al., 2006). Lactobacillus and Enterococcus are commensal bacteria in healthy stomachs, with abundances up to 30 and 51%, respectively. However, exceeding these limits is thought to be a risk for GC (Gantuya et al., 2020).

The predominant bacterial phyla in H. pylori-positive gastric antrum ulcers were Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes. H. pylori was dominant at the genus level, followed by Prevotella, Neisseria, and Streptococcus (Chen et al., 2018). Johnsonella ignava and Filifactor alocis were enriched in patients with gastric IM compared with healthy control individuals, and Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus parasanguinis, and Streptococcus sanguinis were depleted. The sugar degradation pathways of gut microbiota were also depleted in IM patients, while the lipopolysaccharide and ubiquinol biosynthesis pathways were more abundant (Wu et al., 2022).

Ferreira et al. (2018) found that Helicobacter, Neisseria, Prevotella, and Streptococcus were more abundant in patients with chronic gastritis. There was a significant decrease in Helicobacter in gastric carcinoma, while the Phyllobacterium, Achromobacter, Citrobacter, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, and Rhodococcus genera were more abundant (Ferreira et al., 2018). Changes in bacterial diversity during GC progression are inconsistent across studies. Some studies have shown a progressive decline in microbial diversity from gastritis to cancer (Aviles-Jimenez et al., 2014), while others have found increases in bacterial diversity during this process (Eun et al., 2014). These differences potentially reflect the different microbiota characterization platforms and study populations used across studies. The pathogenic mechanisms of gastric microorganisms, including H. pylori, may include inducing the inflammatory response, influencing the function of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, and producing harmful metabolites, such as N-nitroso compounds (Li and Yu, 2020).

Gastric microecology is also affected by drug use. For example, vancomycin reduced the abundance of Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla (Satoh-Takayama et al., 2020). In addition, PPI-treated patients had more Streptococcus than patients with normal gastric mucosa (Parsons et al., 2017) and dyspeptic patients without PPI treatment (Sterbini et al., 2016).

Helicobacter pylori infection has been reported to modulate gastric microbe diversity (Das et al., 2017). H. pylori+/CagA+ samples showed lower gastric microflora diversity and Roseburia abundance but higher Helicobacter and Haemophilus genera abundances than healthy or H. pylori+/CagA– samples (Zhao et al., 2019). The relative abundances of phyla, including Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, and Verrucomicrobia, were significantly decreased in H. pylori+ children compared to H. pylori– children. Nine genera differed in abundance between H. pylori+ and H. pylori– children, including Helicobacter, Achromobacter, Devosia, Halomonas, Mycobacterium, Pseudomonas, Serratia, Sphingopyxis, and Stenotrophomonas (Zheng et al., 2021).

Helicobacter pylori acts to produce urease, which transforms urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia to neutralize the acidic environment of the stomach to facilitate its colonization (Weeks et al., 2000). Acute infection can lead to hypochlorhydria, while chronic infection at different anatomical sites can result in hypo- or hyperchlorhydria. Changes in acid secretion caused by H. pylori may allow ingested microorganisms to survive transit through the stomach (Smolka and Schubert, 2017). There has been a hypothesis that while reduced gastric pH during acute H. pylori infection leads to colonization, elevated gastric pH during chronic H. pylori infection leads to a microbial bloom that further inhibits H. pylori growth (Das et al., 2017).

The varied host responses to H. pylori infection may be attributed to gastric microbe diversity and abundance (Table 1). A family-level analysis of bacterial abundance showed apparent differences between the C57BL/6 mice from Jackson Laboratory (Jax) and the C57BL/6 mice from Taconic Sciences (Tac), accompanied by different responses to H. pylori infection. H. pylori-infected Jax mice had higher H. pylori colonization levels and gastric IL-1β and IL-17A transcription, while H. pylori-infected Tac mice had more severe metaplasia of the gastric mucosa and a stronger Th1-associated IgG2c response to H. pylori. In addition, the energy metabolism, amino acid, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways were upregulated in the microbiota that resided in the stomach of Jax mice. In contrast, lipid, cofactor, vitamin metabolism and xenobiotic biodegradation were elevated in the stomach of Tac mice. The difference in gastric bacterial community structures could potentially regulate distinct pathways, which could affect stomach physiology and lead to different H. pylori infection responses (Ge et al., 2018).

Helicobacter pylori infection modulates the host immune system in profound ways, including suppression of T helper 17 (Th17) cells and induction of regulatory T (Treg) cells (Lehours and Ferrero, 2019). Commensal gastric microbes or their metabolites influence the capability of H. pylori to colonize the stomach and its pathogenic and carcinogenic potential by modulating host immune responses (Espinoza et al., 2018). The presence of non-H. pylori bacteria might persistently act as an antigenic stimulus or establish a partnership with H. pylori to enhance subsequent inflammation (Rook et al., 2017). Stomach-derived urease-positive Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus salivarius were independently inoculated into GF INS-GAS mice with H. pylori. The gastric pathology of the latter was significantly higher than in mice only infected with H. pylori. In contrast, the proinflammatory cytokine responses (IL-1β, IL-22, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) of the former were significantly lower than those in mice only infected with H. pylori (Shen et al., 2022). Studies have found that the IL-17A to FOXP3 mRNA ratio was inversely correlated with H. pylori abundance in infected children. Moreover, gastric microbial communities significantly upregulated their alpha-linolenic acid and arachidonic acid metabolism. Therefore, Zheng et al. (2021) hypothesized that the balance between Treg and Th17 cells might be biased toward Treg cells, which is beneficial to bacterial persistence, and the gastric microbiota might generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and small molecules to modulate mucosal Treg responses in H. pylori-infected children. In addition, Satoh-Takayama et al. (2020) showed that ILC2s, regulated by local commensal communities through IL-7 and IL-33 induction, are the predominant ILC subset in the stomach and protect against H. pylori infection through B-cell activation and IgA production.

Candida albicans is one of the most common fungi in the human body. In Karczewska et al. (2009) reported the coexistence of H. pylori with Candida in patients with gastric ulcers, suggesting their synergy in disease pathogenesis. H. pylori is a facultative intracellular bacterium that may protect itself against environmental stress by entering C. albicans cells, allowing the invading H. pylori to be transmitted to subsequent C. albicans generations (Siavoshi and Saniee, 2014; Siavoshi et al., 2019). Siavoshi et al. (2019) found that the yeast vacuole served as a sophisticated niche for H. pylori, with sequestration inside the vacuole potentially enhancing bacterial survival. It should be noted that the proportion of yeast cells harboring bacteria in an acidic environment was nearly twice that in a neutral environment. However, when the pH is < 4, the number of bacteria-invaded yeast cells decreases sharply (Sanchez-Alonzo et al., 2020). In addition, temperature, anaerobic environment, nutritional condition, and drugs (e.g., amphotericin B) might affect the entry or exit of H. pylori in Candida cells (Sanchez-Alonzo et al., 2021a,c, 2022; Tavakolian et al., 2018). H. pylori has been reported to invade vaginal yeast cells, causing vertical transmission during birth (Sanchez-Alonzo et al., 2021b). In addition, C. albicans harboring H. pylori is also abundant in honeybees, honey, flowers, and natural fruits (Siavoshi et al., 2018). These results suggest that we can reduce or prevent H. pylori transmission through fungal interventions.

Helicobacter pylori and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) have been reported to cooperate to induce more severe gastritis than each alone. Their combined infection promotes host expression of the oncogenic protein gankyrin and the oncogenic properties of human gastric adenocarcinoma cells (AGS) (Cárdenas-Mondragón et al., 2013; Kashyap et al., 2021). Higher expression of latent EBV nuclear antigen 1 and 3C (ebna1 and ebna3c) genes was observed at 12 and 24 h in samples coinfected with H. pylori and EBV compared with EBV alone. Similarly, the expression levels of the H. pylori-associated genes 16S rRNA, CagA, and blood-group antigen-binding adhesin (babA) were higher in coinfected cells than in cells infected with H. pylori alone (Kashyap et al., 2021). Pandey et al. (2018) showed that the CagA protein of H. pylori promoted EBV-mediated proliferation of coinfected cells. EBV enhanced H. pylori CagA activity by downregulating one of its host antagonists, Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (Saju et al., 2016).

Radical H. pylori treatment regimens involve PPI triple therapy, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, modified regimens (modified bismuth-containing quadruple regimen, high-dose dual therapy, and vonoprazan-containing regimens), concomitant therapy, hybrid therapy, and sequential therapy (Liu et al., 2021). While the eradication of H. pylori affects gastric microbial composition and function, whether H. pylori eradication restores the gastric microbiota to an uninfected status remains controversial (Guo et al., 2022). Predictable factors affecting gastric microecological recovery after H. pylori eradication might include atrophy/metaplasia in the basal state, higher neutrophil infiltration at the corpus, lower pepsinogen (PG) I/II ratio, and higher relative Acinetobacter abundance (Shin et al., 2020). A recent meta-analysis showed that the gastric microbial composition changed significantly after quadruple or triple therapy, with relative H. pylori-related taxa abundance (Proteobacteria phylum and Helicobacter genus) decreasing to different degrees. In contrast, typically dominant gastric commensals (e.g., Firmicutes, Bacteroides, and Actinobacteria) were enriched after H. pylori eradication (Guo et al., 2022). Studies exploring changes in gastric microbiota functions after H. pylori eradication found that bacterial reproduction-related pathways, such as flagellar assembly, chemotaxis, and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor signaling, were downregulated in gastric microbiota. In contrast, normal gastric function-related pathways, such as gastric acid secretion, protein digestion and absorption, and amino acid metabolism, were upregulated (He et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2020; Sung et al., 2020).

Antibiotic treatment leads to the widespread destruction of bacterial community structures. Human microbiome reconstitution after antibiotic treatment is usually slow and incomplete (Suez et al., 2018). With increasing antibiotic resistance, guidelines recommend bismuth quadruple therapy as the first-line treatment (Fallone et al., 2019). There is evidence that the effectiveness of bismuth-containing quadruple H. pylori eradication therapy depends on gastric microbiota, as high H. pylori eradication rates are associated with Lactobacillus, Rhodococcus, and Sphingomonas (Niu et al., 2021).

Probiotics are living microorganisms that benefit the host when administered in adequate amounts (Hill et al., 2014). They have been shown to reduce H. pylori-induced gastric pathology in mice, with reduced inflammatory infiltration and precancerous lesion incidence (He et al., 2022). They also enhance H. pylori eradication rates and reduce side effects in humans (Zhang et al., 2015; McFarland et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2019; Viazis et al., 2022). Yuan et al. (2021) explored the effect of probiotic-supplemented quadruple therapy on gastric microecology. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus were enriched in the gastric mucosa and juice, respectively, of the probiotic-supplemented group compared to the quadruple therapy group. In contrast, the levels of potentially pathogenic bacteria, including Fusobacterium and Campylobacter, were decreased. Microbial diversity was closer to that of H. pylori-negative subjects after probiotic-supplemented eradication treatment (Yuan et al., 2021).

Currently, probiotics with potential activity against H. pylori infection belong to the Firmicutes (Enterococcus and Lactobacillus) and Actinobacteria (Bifidobacterium genus) phyla and Saccharomyces boulardii (Keikha and Karbalaei, 2021). The most commonly proposed mechanisms underlying the probiotic effects include inhibiting pathogens, producing useful metabolites or enzymes, and modulating immunity. In addition, quorum sensing is considered to be one of the mechanisms of probiotics regulating the restoration of the gastric microbiota. Probiotics may exert beneficial effects through one or more of these pathways (Table 2).

Lactobacillus reuteri inhibits H. pylori attachment by competitively binding to gastric epithelial gangliotetraosylceramide (asialo-GM1) and sulfatide (Mukai et al., 2002). S. boulardii produces neuraminidase selective for α (2–3)-linked sialic acid to remove H. pylori adhesin ligands, inhibiting H. pylori adherence to host cells (Sakarya and Gunay, 2014). Do et al. (2021a,b) used a cell model to show that Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB3 (LR-JB3) reduced H. pylori VacA, sialic acid-binding adhesin (SabA), and fucosyltransferases (FucT) and decreased Lewis (Le)x antigen, toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and α5β1 integrin expression in AGS cells. Therefore, it further suppressed lipid raft clustering and attenuated Lewis antigen-dependent adherence, T4SS-mediated cell contact, and lipid-raft-mediated VacA entry into host cells (Do et al., 2021a,b).

Probiotic-derived metabolites have been extensively studied in H. pylori eradication. Cell-free lactic acid bacterial culture supernatants reduced H. pylori growth, urease activity, flagella-mediated motility, and H. pylori-induced host IL-8 secretion (Whiteside et al., 2021). The probiotics produced bacteriocins, such as Lacticins A164 and BH5, that could antagonize the proliferation of H. pylori (Kim et al., 2003). Lactobacillus brevis BK11 and Enterococcus faecalis BK61 reduced H. pylori urease activity and adhesion to cultured human gastric adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (Lim, 2015). In addition, Boyanova et al. (2017) found that bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains could kill antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant H. pylori.

Probiotics can reshape the gastric microbiota structure. Probiotic administration enhanced the proportion of beneficial SCFA-producing bacteria, including Bacteroides, Alloprevotella, Oscellibacter, in the stomachs of H. pylori-infected mice (He et al., 2022). Sodium butyrate, one of the representative SCFAs, not only inhibited H. pylori growth and CagA and VacA expression, but also inhibited the host NF-κB pathway by reducing toll-like receptor expression in host cells to decrease TNF-α and IL-8 production (Huang et al., 2021). However, another bacterial metabolite, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), increased H. pylori viability and virulence and exacerbated H. pylori-induced inflammation (Wu et al., 2020). The synergistic effects of H. pylori and TMAO enhanced inflammation-related gene expression, including IL-6, C-X-C motif chemokine ligands 1 and 2 (CXCL1, CXCL2), FOS, and complement C3 in the gastric epithelium (Wu et al., 2017). Trimethylamine (TMA) is the TMAO precursor. It is mainly produced by Firmicutes (e.g., Staphylococcus) and relatively rare in Bacteroidetes (Fennema et al., 2016). Overall, probiotics may increase the proportion of beneficial metabolite-producing bacteria and/or reduce the proportion of harmful metabolite-producing bacteria.

Increasing evidence has suggested the role of probiotics in immune modulation in H. pylori-infected animal models. The combined administration of probiotic Lactobacillus salivarius and Lactobacillus rhamnosus attenuated inflammatory pathways, such as NF-κB, IL-17, and TNF-α, in H. pylori-infected mice (He et al., 2022). Several Lactobacillus spp. isolates have been reported to reduce IL-8 secretion by H. pylori-infected AGS cells. These include decreasing Cag secretory system function (Ryan et al., 2009), inactivating the SMAD family member 7 (Smad7) and NF-κB pathways (Yang et al., 2012), and suppressing c-Jun activation (Thiraworawong et al., 2014). The L. salivarius strain B37 produced a polysaccharide as an immunomodulatory factor of IL-8 production in the gastric epithelium. In addition, the mixture of polysaccharides, lipids and proteins secreted by L. salivarius strain B60 was involved in mediating IL-8 production (Panpetch et al., 2016). Moreover, animals receiving Lactobacillus fermentum P2, Lactobacillus casei L21, LR-JB3, or their combination had decreased H. pylori-specific IgA and IgM levels in the stomach, and IFN-γ and IL-1β levels in the serum (Lin et al., 2020).

The quorum sensing (QS) system is a molecular signaling mechanism for interbacterial communications to control their behavior, such as growth, virulence, and pathogenicity (Wu et al., 2021). The protein encoded by the S-ribosylhomocysteine lyase (LuxS) gene of H. pylori synthesizes autoinducer 2 (AI-2), which is a major molecule of QS (Forsyth and Cover, 2000). AI-2 has been reported to regulate H. pylori activity, including biofilm formation (Anderson et al., 2015) and motility (Rader et al., 2007). It has also been reported to reduce CagA expression and bacterial adhesion to attenuate the H. pylori-induced inflammatory response in gastric epithelial cells (Wen et al., 2021). In addition, AI-2 induces urease expression in H. pylori by downregulating the orphan response regulator HP1021, potentially enhancing acid acclimation when bacterial density increases (Yang et al., 2022).

QS is involved in the balance between the gut microbiota and the host. Many studies have gradually focused on QS-mediated interactions between different bacterial populations (Wu et al., 2021). Recently, Do et al. (2021a) found that LR-JB3 inhibited LuxS expression in H. pylori. An unknown bioactive signal secreted by LR-JB3 acts as an AI-2 signal antagonist, attenuating the effect of AI-2 and affecting the binding ability of H. pylori to AGS cells (Do et al., 2021a).

Synbiotics are mixtures of living microorganisms (Swanson et al., 2020). Prebiotics are substrates selectively used by host health-promoting microorganisms (Gibson et al., 2017). Postbiotics are inanimate microorganisms and their components that confer a health benefit on the host (Salminen et al., 2021). The most widely documented dietary prebiotics in humans are the non-digestible oligosaccharides fructans and galactans (Gibson et al., 2017). Current postbiotic microorganism components include cell-free supernatants, bacterial lysates, cell wall fragments, exopolysaccharides, enzymes, and metabolites (SCFAs, vitamins, phenolic-derived metabolites, and aromatic amino acids) (Zolkiewicz et al., 2020).

A maternal-infant cohort study showed that dominant breastfeeding might prevent early H. pylori colonization (Shah et al., 2022). Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) unique to human milk were found to be prebiotic bifidus factors that promote colonization by Bifidobacteria members (Hill et al., 2021) and support cross-feeding among Bifidobacteria and other genera, such as butyrogenic Anaerostipes caccae (Chia et al., 2021). Postbiotic molecules, such as lactic acid (Arena et al., 2016) and bacteriocins (Kim et al., 2003), might have direct antimicrobial activity. However, postbiotics might also indirectly modulate the microbiota by carrying QS and quorum-quenching molecules (Grandclément et al., 2016). A meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials suggested that synbiotics might improve H. pylori eradication rates and reduce adverse effects (Ustundag et al., 2017).

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been used to effectively restore the GI microbiota to treat GI diseases, such as Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease (Allegretti et al., 2019). Washing microflora transfer (WMT) is a modified FMT method that uses washed preparations. WMT application via the stomach, jejunum, or right hemicolon delivery routes caused an overall H. pylori eradication of 40.6% in a cohort of 32 H. pylori-infected patients, which was significantly associated with an increased pre-WMT PG ratio. It should be noted that the relationship between the curative effect, sex, and delivery route (upper, middle, and lower GI tract) requires further investigation (Ye et al., 2020).

In healthy adults, the bacterial community differs not only in individuals but also in different GI regions of the same individual. Therefore, the fecal microbiome is not representative of the mucosal microbiome (Vasapolli et al., 2019). A recent study found that GF mice fed gastric mucosal tissue and juice from patients with IM or GC were colonized by specific human gastric microorganisms. Moreover, they recapitulated the major histopathological features of premalignant changes (Kwon et al., 2022). The total number of ILC2s in the stomach was lower in GF mice than in SPF mice. However, ILC2 numbers and IL-5 levels were elevated after stomach microbiota transfer by gavage of stomach contents and mucosal scraping from SPF mice to GF mice, correlating with the increased relative abundance of Bacteroidales family S24-7 (Satoh-Takayama et al., 2020). Although research on gastric microbiota transplantation (GMT) in H. pylori eradication is lacking, it appears to have broad prospects.

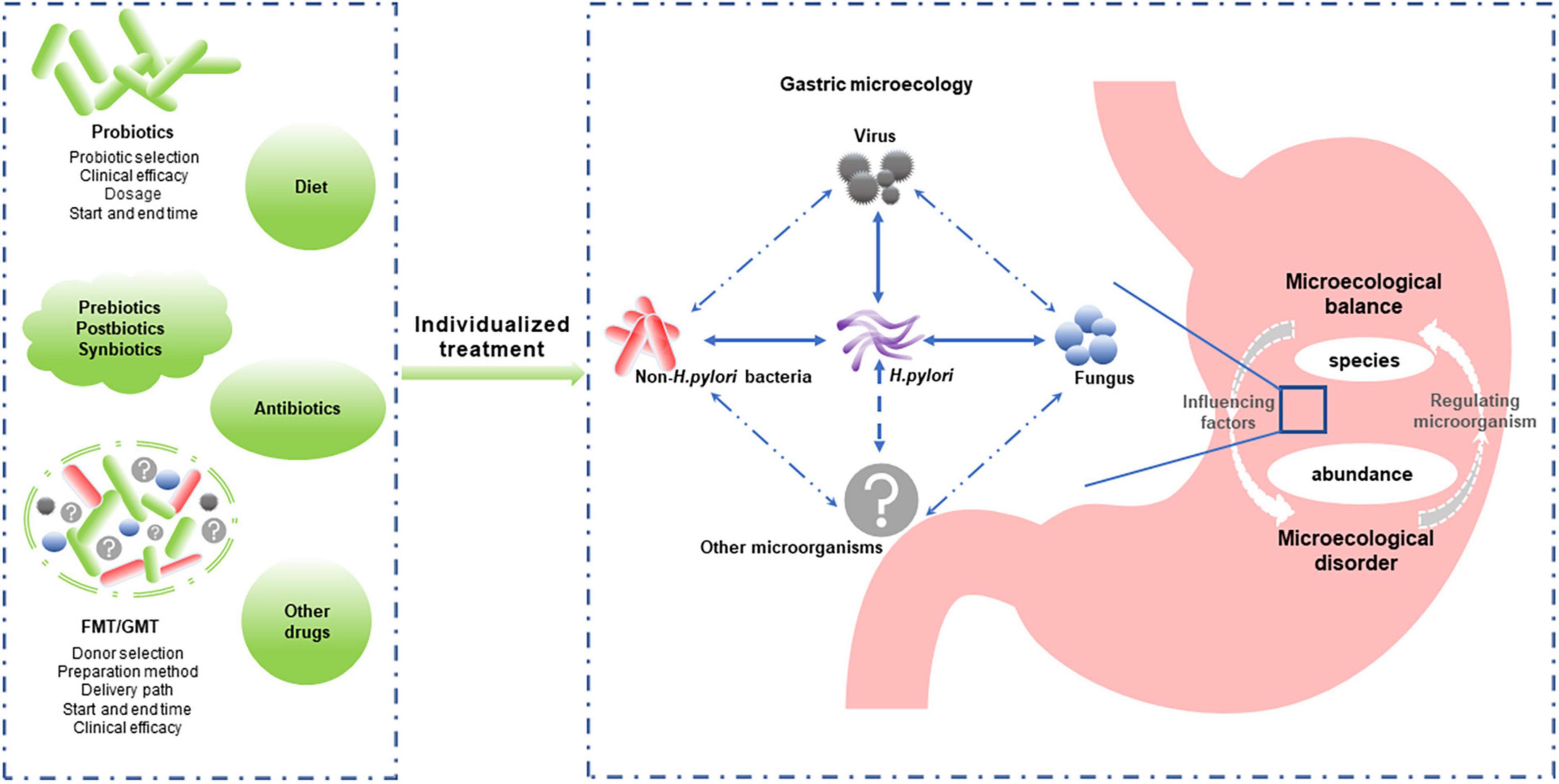

While the importance of non-H. pylori bacteria in gastric diseases has been highlighted by in-depth gastric microecology studies, the role of H. pylori cannot be ignored. Some scholars believe that the potential protective effects of H. pylori for some diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (Engler et al., 2015), need to be taken seriously, and H. pylori should even be considered a commensal organism, not just an opportunistic pathogen (Reshetnyak et al., 2021). Similarly, many Lactobacillus species used as probiotics play a role in preventing pathogen infection, reducing inflammation, and modulating the microbiota. However, Lactobacillus was also able to induce inflammatory damage to epithelial cells and was associated with GC (Vinasco et al., 2019). Whether the balance between its beneficial and detrimental effects is related to specific bacterial species or abundance is worthy of further study. Considering the balance of the gastric microecology (e.g., bacteria, fungi, and viruses) rather than the role of specific bacteria may provide us with new approaches for preventing and treating gastric diseases (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Individualized reconstruction of the healthy gastric microbiota is a promising strategy for managing microecology dysbiosis-associated gastric diseases. Gastric microbiota composition and abundance and the interaction between gastric microbiomes (including Helicobacter pylori and non-H. pylori bacteria, fungi, and viruses) play important roles in gastric microecological homeostasis. Modulating the microbiota (probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, synbiotics, and FMT/GMT) is expected to improve and restore the gastric microflora balance. However, individualized treatment options, such as the bacteria type or donor selection, delivery path, and start and end times, require further study. FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; GMT, gastric microbiota transplantation.

Regulating gastric microecology might play an important role in H. pylori eradication. Oral microbe administration always leads to a substantial loss of viability due to the highly acidic environment of the stomach (Li S. et al., 2020). Host factors influencing probiotic colonization and efficacy include diet, age, antibiotic use, underlying medical conditions, and baseline microbiome composition and function (Suez et al., 2020). In addition, studies have found that probiotic colonization resistance is partly due to the indigenous gut microbiome (Zmora et al., 2018). Antibiotic therapy in healthy individuals can partially overcome probiotic colonization resistance due to the homeostatic microbiome, improving probiotic colonization in the depleted gut mucosal layer (Suez et al., 2018). Therefore, the clinical efficacy of probiotics against H. pylori requires larger samples and more extended observation, and individualized treatment plans need to be further developed (Figure 2).

Furthermore, microbiome transplantation induced a rapid and nearly complete reconstitution of the gut microbiome after antibiotic treatment. Therefore, it appears to provide rapid postantibiotic protection during the nadir period of the intestinal mucosal microbiome compared to structurally single probiotics (Suez et al., 2018). GMT is a promising strategy for restoring normal gastric microbiota that requires further investigation (Figure 2).

LZ drafted the preliminary manuscript. MZ and XF refined and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81972315) granted to XF.

We thank the members of XF’s laboratory for their helpful advice and discussion.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allegretti, J. R., Mullish, B. H., Kelly, C., and Fischer, M. (2019). The evolution of the use of faecal microbiota transplantation and emerging therapeutic indications. Lancet 394, 420–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31266-8

Anderson, J., Huang, J., Wreden, C., Sweeney, E., Goers, J., Remington, S., et al. (2015). Chemorepulsion from the quorum signal autoinducer-2 promotes Helicobacter pylori biofilm dispersal. mBio 6:e00379. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00379-15

Arena, M. P., Silvain, A., Normanno, G., Grieco, F., Drider, D., Spano, G., et al. (2016). Use of Lactobacillus plantarum strains as a bio-control strategy against food-borne pathogenic microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 7:464. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00464

Aviles-Jimenez, F., Vazquez-Jimenez, F., Medrano-Guzman, R., Mantilla, A., and Torres, J. (2014). Stomach microbiota composition varies between patients with non-atrophic gastritis and patients with intestinal type of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 4:4202. doi: 10.1038/srep04202

Barra, W. F., Sarquis, D. P., Khayat, A. S., Khayat, B. C., Demachki, S., Anaissi, A. K., et al. (2021). Gastric cancer microbiome. Pathobiology 88, 156–169. doi: 10.1159/000512833

Bhaskar, K. R., Garik, P., Turner, B. S., Bradley, J. D., Bansil, R., Stanley, H. E., et al. (1992). Viscous fingering of HCl through gastric mucin. Nature 360, 458–461. doi: 10.1038/360458a0

Bik, E. M., Eckburg, P. B., Gill, S. R., Nelson, K. E., Purdom, E. A., Francois, F., et al. (2006). Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 732–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103

Binh, T., Tuan, V., Dung, H., Dung, H., Tung, P., Tri, T., et al. (2018). Molecular epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in a minor ethnic group of Vietnam: A multiethnic, population-based study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:708. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030708

Boyanova, L., Gergova, G., Markovska, R., Yordanov, D., and Mitov, I. (2017). Bacteriocin-like inhibitory activities of seven Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains against antibiotic susceptible and resistant Helicobacter pylori strains. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 65, 469–474. doi: 10.1111/lam.12807

Brandi, G., Biavati, B., Calabrese, C., Granata, M., Nannetti, A., Mattarelli, P., et al. (2006). Urease-positive bacteria other than Helicobacter pylori in human gastric juice and mucosa. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101, 1756–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00698.x

Brawner, K. M., Kumar, R., Serrano, C. A., Ptacek, T., Lefkowitz, E., Morrow, C. D., et al. (2017). Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an altered gastric microbiota in children. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 1169–1177. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.131

Burucoa, C., and Axon, A. (2017). Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 22(Suppl 1):e12403. doi: 10.1111/hel.12403

Cárdenas-Mondragón, M. G., Carreón-Talavera, R., Camorlinga-Ponce, M., Gomez-Delgado, A., Torres, J., and Fuentes-Panan, E. M. (2013). Epstein Barr virus and Helicobacter pylori co-infection are positively associated with severe gastritis in pediatric patients. PLoS One 8:e62850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062850

Chen, X., Xia, C., Li, Q., Jin, L., Zheng, L., and Wu, Z. (2018). comparisons between bacterial communities in mucosa in patients with gastric antrum ulcer and a duodenal ulcer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8:126. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00126

Chia, L. W., Mank, M., Blijenberg, B., Bongers, R. S., Limpt, K v, Wopereis, H., et al. (2021). Cross-feeding between Bifidobacterium infantis and Anaerostipes caccae on lactose and human milk oligosaccharides. Benef. Microbes 12, 69–83. doi: 10.3920/BM2020.0005

Das, A., Pereira, V., Saxena, S., Ghosh, T. S., Anbumani, D., Bag, S., et al. (2017). Gastric microbiome of Indian patients with Helicobacter pylori infection, and their interaction networks. Sci. Rep. 7:15438. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15510-6

Delgado, S., Cabrera-Rubio, R., Mira, A., Suárez, A., and Mayo, B. (2013). Microbiological survey of the human gastric ecosystem using culturing and pyrosequencing methods. Microb. Ecol. 65, 763–772. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0192-5

Do, A., Chang, C., Su, C., and Hsu, Y. (2021a). Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB3 inhibits Helicobacter pylori infection through multiple molecular actions. Helicobacter 26:e12806. doi: 10.1111/hel.12806

Do, A., Su, C., and Hsu, Y. (2021b). Antagonistic activities of Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB3 against Helicobacter pylori infection through lipid raft formation. Front. Immunol. 12:796177. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.796177

Engler, D. B., Leonardi, I., Hartung, M. L., Kyburz, A., Spath, S., Becher, B., et al. (2015). Helicobacter pylori-specific protection against inflammatory bowel disease requires the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-18. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21, 854–861. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000318

Engstrand, L., and Lindberg, M. (2013). Helicobacter pylori and the gastric microbiota. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 27, 39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.03.016

Espinoza, J. L., Matsumoto, A., Tanaka, H., and Matsumura, I. (2018). Gastric microbiota: An emerging player in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric malignancies. Cancer Lett. 414, 147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.11.009

Eun, C. S., Kim, B. K., Han, D. S., Kim, S. Y., Kim, K. M., Choi, B. Y., et al. (2014). Differences in gastric mucosal microbiota profiling in patients with chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric cancer using pyrosequencing methods. Helicobacter 19, 407–416. doi: 10.1111/hel.12145

Fallone, C., Moss, S., and Malfertheiner, P. (2019). Reconciliation of recent Helicobacter pylori treatment guidelines in a time of increasing resistance to antibiotics. Gastroenterology 157, 44–53. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.04.011

Fang, H., Zhang, G., Cheng, J., and Li, Z. (2019). Efficacy of Lactobacillus-supplemented triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in children: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pediatr. 178, 7–16. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3282-z

Fennema, D., Phillips, I., and Shephard, E. (2016). Trimethylamine and Trimethylamine N-oxide, a flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3)-mediated host-microbiome metabolic axis implicated in health and disease. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44, 1839–1850. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.070615

Ferreira, R. M., Pereira-Marques, J., Pinto-Ribeiro, I., Costa, J. L., Carneiro, F., Machado, J. C., et al. (2018). Gastric microbial community profiling reveals a dysbiotic cancer-associated microbiota. Gut 67, 226–236. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314205

Forsyth, M., and Cover, T. (2000). Intercellular communication in Helicobacter pylori: luxS is essential for the production of an extracellular signaling molecule. Infect. Immun. 68, 3193–3199. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3193-3199.2000

Gantuya, B., Serag, H. B., Matsumoto, T., Ajami, N. J., Uchida, T., Oyuntsetseg, K., et al. (2020). Gastric mucosal microbiota in a Mongolian population with gastric cancer and precursor conditions. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 51, 770–780. doi: 10.1111/apt.15675

Ge, Z., Sheh, A., Feng, Y., Muthupalani, S., Ge, L., Wang, C., et al. (2018). Helicobacter pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice with different gastrointestinal microbiota have contrasting gastric pathology, microbial and host immune responses. Sci. Rep. 8:8014. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25927-2

Gibson, G. R., Hutkins, R., Sanders, M. E., Prescott, S. L., Reimer, R. A., Salminen, S. J., et al. (2017). Expert consensus document: The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 491–502. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75

Grandclément, C., Tannières, M., Moréra, S., Dessaux, Y., and Faure, D. (2016). Quorum quenching: Role in nature and applied developments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 86–116. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv038

Guo, Y., Cao, X., Guo, G., Zhou, M., and Yu, B. (2022). Effect of Helicobacter Pylori eradication on human gastric microbiota: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12:899248. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.899248

Guo, Y., Zhang, Y., Gerhard, M., Gao, J., Mejias-Luque, R., Zhang, L., et al. (2020). Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastrointestinal microbiota: A population-based study in Linqu, a high-risk area of gastric cancer. Gut 69, 1598–1607. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319696

He, C., Peng, C., Wang, H., Ouyang, Y., Zhu, Z., Shu, X., et al. (2019). The eradication of Helicobacter pylori restores rather than disturbs the gastrointestinal microbiota in asymptomatic young adults. Helicobacter 24:e12590. doi: 10.1111/hel.12590

He, C., Peng, C., Xu, X., Li, N., Ouyang, Y., Zhu, Y., et al. (2022). Probiotics mitigate Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and premalignant lesions in INS-GAS mice with the modulation of gastrointestinal microbiota. Helicobacter 27:e12898. doi: 10.1111/hel.12898

Hill, C., Guarner, F., Reid, G., Gibson, G. R., Merenstein, D. J., Pot, B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document. The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

Hill, D., Chow, J., and Buck, R. (2021). Multifunctional benefits of prevalent HMOs: Implications for infant health. Nutrients 13:3364. doi: 10.3390/nu13103364

Hooi, J. K., Lai, W. Y., Ng, W. K., Suen, M. M., Underwood, F. E., Tanyingoh, D., et al. (2017). Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 153, 420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022

Huang, Y., Ding, Y., Xu, H., Shen, C., Chen, X., and Li, C. (2021). Effects of sodium butyrate supplementation on inflammation, gut microbiota, and short-chain fatty acids in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Helicobacter 26:e12785. doi: 10.1111/hel.12785

Human Microbiome Project Consortium (2012). Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234

Hunt, R. H., Camilleri, M., Crowe, S. E., El-Omar, E. M., Fox, J. G., Kuipers, E. J., et al. (2015). The stomach in health and disease. Gut 64, 1650–1668. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307595

Karczewska, E., Wojtas, I., Sito, E., Trojanowska, D., Budak, A., Zwolinska-Wcislo, M., et al. (2009). Assessment of co-existence of Helicobacter pylori and Candida fungi in diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 60(Suppl. 6), 33–39.

Kashyap, D., Baral, B., Jakhmola, S., Singh, A., and Jha, H. (2021). Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus coinfection stimulates aggressiveness in gastric cancer through the regulation of gankyrin. mSphere 6:e0075121. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00751-21

Keikha, M., and Karbalaei, M. (2021). Probiotics as the live microscopic fighters against Helicobacter pylori gastric infections. BMC Gastroenterol. 21:388. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01977-1

Kim, T., Hur, J., Yu, M., Cheigh, C., Kim, K., Hwang, J., et al. (2003). Antagonism of Helicobacter pylori by bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. J. Food Prot. 66, 3–12. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-66.1.3

Kronsteiner, B., Bassaganya-Riera, J., Philipson, C., Viladomiu, M., Carbo, A., Abedi, V., et al. (2016). Systems-wide analyses of mucosal immune responses to Helicobacter pylori at the interface between pathogenicity and symbiosis. Gut Microbes 7, 3–21. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1116673

Kwon, S., Park, J. C., Kim, K. H., Yoon, J., Cho, Y., Lee, B., et al. (2022). Human gastric microbiota transplantation recapitulates premalignant lesions in germ-free mice. Gut 71, 1266–1276. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324489

Lehours, P., and Ferrero, R. (2019). Review: Helicobacter: Inflammation, immunology, and vaccines. Helicobacter 24(Suppl. 1):e12644. doi: 10.1111/hel.12644

Li, Q., and Yu, H. (2020). The role of non-H. pylori bacteria in the development of gastric cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 10, 2271–2281.

Li, Y., Li, W., Wang, X., Ding, C., Liu, J., Li, Y., et al. (2020). High-salt diet-induced gastritis in C57BL/6 mice is associated with microbial dysbiosis and alleviated by a buckwheat diet. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 64:e1900965. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900965

Li, S., Jiang, W., Zheng, C., Shao, D., Liu, Y., Huang, S., et al. (2020). Oral delivery of bacteria: Basic principles and biomedical applications. J. Control Release 327, 801–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.09.011

Li, T. H., Qin, Y., Sham, P. C., Lau, K. S., Chu, K., and Leung, W. K. (2017). Alterations in gastric microbiota after H. Pylori eradication and in different histological stages of gastric carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 7:44935. doi: 10.1038/srep44935

Li, X., Wong, G., To, K., Wong, V., Lai, L., Chow, D., et al. (2009). Bacterial microbiota profiling in gastritis without Helicobacter pylori infection or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. PLoS One 4:e7985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007985

Lim, E. (2015). Purification and characterization of two bacteriocins from Lactobacillus brevis BK11 and Enterococcus faecalis BK61 showing anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 58, 703–714. doi: 10.1007/s13765-015-0094-y

Lin, C., Huang, W., Su, C., Lin, W., Wu, W., Yu, B., et al. (2020). Effects of multi-strain probiotics on immune responses and metabolic balance in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Nutrients 12:2476. doi: 10.3390/nu12082476

Liu, C., Wang, Y., Shi, J., Zhang, C., Nie, J., Li, S., et al. (2021). The status and progress of first-line treatment against Helicobacter pylori infection: A review. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 14:1756284821989177. doi: 10.1177/1756284821989177

Lofgren, J. L., Whary, M. T., Ge, Z., Muthupalani, S., Taylor, N. S., Mobley, M., et al. (2011). Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 140, 210–220. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.048

Marshall, B., and Warren, J. (1984). Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1, 1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6

McFarland, L. V., Huang, Y., Wang, L., and Malfertheiner, P. (2016). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Multi-strain probiotics as adjunct therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication and prevention of adverse events. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 4, 546–561. doi: 10.1177/2050640615617358

Megraud, F., Bruyndonckx, R., Coenen, S., Wittkop, L., Huang, T., Hoebeke, M., et al. (2021). Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe in 2018 and its relationship to antibiotic consumption in the community. Gut 70, 1815–1822. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324032

Miftahussurur, M., Waskito, L. A., El-Serag, H. B., Ajami, N. J., Nusi, I. A., Syam, A. F., et al. (2020). Gastric microbiota and Helicobacter pylori in Indonesian population. Helicobacter 25:e12695. doi: 10.1111/hel.12695

Mukai, T., Asasaka, T., Sato, E., Mori, K., Matsumoto, M., and Ohori, H. (2002). Inhibition of binding of Helicobacter pylori to the glycolipid receptors by probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 32, 105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00541.x

Nardone, G., and Compare, D. (2015). The human gastric microbiota: Is it time to rethink the pathogenesis of stomach diseases? United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 3, 255–260. doi: 10.1177/2050640614566846

Ndegwa, N., Ploner, A., Andersson, A. F., Zagai, U., Andreasson, A., Vieth, M., et al. (2020). Gastric microbiota in a low-Helicobacter pylori prevalence general population and their associations with gastric lesions. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 11:e00191. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000191

Niu, Z., Li, S., Shi, Y., and Xue, Y. (2021). Effect of gastric microbiota on quadruple Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy containing bismuth. World J. Gastroenterol. 27, 3913–3924. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3913

Pandey, S., Jha, H., Shukla, S., Shirley, M., and Robertson, E. (2018). Epigenetic regulation of tumor suppressors by Helicobacter pylori enhances EBV-induced proliferation of gastric epithelial cells. mBio 9:e00649-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00649-18

Panpetch, W., Spinler, J. K., Versalovic, J., and Tumwasorn, S. (2016). Characterization of Lactobacillus salivarius strains B37 and B60 capable of inhibiting IL-8 production in Helicobacter pylori-stimulated gastric epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 16:242. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0861-x

Parsons, B. N., Ijaz, U. Z., Amore, R., Burkitt, M. D., Eccles, R., Lenzi, L., et al. (2017). Comparison of the human gastric microbiota in hypochlorhydric states arising as a result of Helicobacter pylori-induced atrophic gastritis, autoimmune atrophic gastritis and proton pump inhibitor use. PLoS Pathog. 13:e1006653. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006653

Peek, R., and Blaser, M. (2002). Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703

Rader, B. A., Campagna, S. R., Semmelhack, M. F., Bassler, B. L., and Guillemin, K. (2007). The quorum-sensing molecule autoinducer 2 regulates motility and flagellar morphogenesis in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6109–6117. doi: 10.1128/JB.00246-07

Reshetnyak, V., Burmistrov, A., and Maev, I. (2021). Helicobacter pylori: Commensal, symbiont or pathogen? World J. Gastroenterol. 27, 545–560. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i7.545

Rook, G., Bäckhed, F., Levin, B. R., McFall-Ngai, M. J., and McLean, A. R. (2017). Evolution, human-microbe interactions, and life history plasticity. Lancet 390, 521–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30566-4

Ryan, K. A., Hara, A. M., Pijkeren, J v, Douillard, F. P., and Toole, P. W. (2009). Lactobacillus salivarius modulates cytokine induction and virulence factor gene expression in Helicobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 996–1005. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.009407-0

Saju, P., Murata-Kamiya, N., Hayashi, T., Senda, Y., Nagase, L., Noda, S., et al. (2016). Host SHP1 phosphatase antagonizes Helicobacter pylori CagA and can be downregulated by Epstein-Barr virus. Nat. Microbiol. 1:16026. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.26

Sakarya, S., and Gunay, N. (2014). Saccharomyces boulardii expresses neuraminidase activity selective for alpha2,3-linked sialic acid that decreases Helicobacter pylori adhesion to host cells. APMIS 122, 941–950. doi: 10.1111/apm.12237

Salminen, S., Collado, M. C., Endo, A., Hill, C., Lebeer, S., Quigley, E. M., et al. (2021). The International scientific association of probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 649–667. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00440-6

Sanchez-Alonzo, K., Arellano-Arriagada, L., Bernasconi, H., Parra-Sepúlveda, C., Campos, V., Silva-Mieres, F., et al. (2022). An anaerobic environment drives the harboring of Helicobacter pylori within Candida yeast cells. Biology (Basel) 11:738. doi: 10.3390/biology11050738

Sanchez-Alonzo, K., Arellano-Arriagada, L., Castro-Seriche, S., Parra-Sepúlveda, C., Bernasconi, H., Benavidez-Hernández, H., et al. (2021a). Temperatures outside the optimal range for Helicobacter pylori increase its harboring within candida yeast cells. Biology (Basel) 10:915. doi: 10.3390/biology10090915

Sanchez-Alonzo, K., Silva-Mieres, F., Arellano-Arriagada, L., Parra-Sepúlveda, C., Bernasconi, H., Smith, C., et al. (2021c). Nutrient deficiency promotes the entry of Helicobacter pylori cells into candida yeast cells. Biology (Basel) 10:426. doi: 10.3390/biology10050426

Sanchez-Alonzo, K., Matamala-Valdes, L., Parra-Sepulveda, C., Bernasconi, H., Campos, V., Smith, C., et al. (2021b). Intracellular presence of Helicobacter pylori and its virulence-associated genotypes within the vaginal yeast of term pregnant women. Microorganisms 9:131. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010131

Sanchez-Alonzo, K., Parra-Sepulveda, C., Vega, S., Bernasconi, H., Campos, V., Smith, C., et al. (2020). In vitro incorporation of Helicobacter pylori into Candida albicans caused by acidic pH stress. Pathogens 9:489. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060489

Santos, M. L., Brito, B. B., Silva, F. A., Sampaio, M. M., Marques, H. S., Silva, N. O., et al. (2020). Helicobacter pylori infection: Beyond gastric manifestations. World J. Gastroenterol. 26, 4076–4093. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i28.4076

Satoh-Takayama, N., Kato, T., Motomura, Y., Kageyama, T., Taguchi-Atarashi, N., Kinoshita-Daitoku, R., et al. (2020). Bacteria-induced group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the stomach provide immune protection through induction of IgA. Immunity 52, 635–649.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.002

Shah, S., Tarassishin, L., Eisele, C., Rendon, A., Debebe, A., Hawkins, K., et al. (2022). Breastfeeding is associated with lower likelihood of Helicobacter pylori colonization in babies, based on a prospective USA maternal-infant cohort. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67, 5149–5157. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07371-x

Shen, Z., Dzink-Fox, J., Feng, Y., Muthupalani, S., Mannion, A., Sheh, A., et al. (2022). Gastric Non-Helicobacter pylori urease-positive Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus salivarius isolated from humans have contrasting effects on H. pylori-associated gastric pathology and host immune responses in a murine model of gastric cancer. mSphere 7:e0077221. doi: 10.1128/msphere.00772-21

Shin, C. M., Kim, N., Park, J. H., and Lee, D. H. (2020). Changes in gastric corpus microbiota with age and after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A long-term follow-up study. Front. Microbiol. 11:621879. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.621879

Siavoshi, F., and Saniee, P. (2014). Vacuoles of Candida yeast as a specialized niche for Helicobacter pylori. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 5263–5273. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5263

Siavoshi, F., Heydari, S., Shafiee, M., Ahmadi, S., Saniee, P., Sarrafnejad, A., et al. (2019). Sequestration inside the yeast vacuole may enhance Helicobacter pylori survival against stressful condition. Infect. Genet. Evol. 69, 127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.01.029

Siavoshi, F., Sahraee, M., Ebrahimi, H., Sarrafnejad, A., and Saniee, P. (2018). Natural fruits, flowers, honey, and honeybees harbor Helicobacter pylori-positive yeasts. Helicobacter 23:e12471. doi: 10.1111/hel.12471

Smolka, A., and Schubert, M. (2017). Helicobacter pylori-induced changes in gastric acid secretion and upper gastrointestinal disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 400, 227–252. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50520-6_10

Sterbini, F. P., Palladini, A., Masucci, L., Cannistraci, C. V., Pastorino, R., Ianiro, G., et al. (2016). Effects of proton pump inhibitors on the gastric mucosa-associated microbiota in dyspeptic patients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 6633–6644. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01437-16

Suez, J., Zmora, N., and Elinav, E. (2020). Probiotics in the next-generation sequencing era. Gut Microbes 11, 77–93. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2019.1586039

Suez, J., Zmora, N., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Mor, U., Dori-Bachash, M., Bashiardes, S., et al. (2018). Post-antibiotic gut mucosal microbiome reconstitution is impaired by probiotics and improved by autologous FMT. Cell 174, 1406–1423.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.047

Sung, J. J., Coker, O. O., Chu, E., Szeto, C. H., Luk, S. T., Lau, H. C., et al. (2020). Gastric microbes associated with gastric inflammation, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia 1 year after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut 69, 1572–1580. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319826

Sung, J., Kim, N., Kim, J., Jo, H. J., Park, J. H., Nam, R. H., et al. (2016). Comparison of gastric microbiota between gastric juice and mucosa by next generation sequencing method. J. Cancer Prev. 21, 60–65. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2016.21.1.60

Swanson, K. S., Gibson, G. R., Hutkins, R., Reimer, R. A., Reid, G., Verbeke, K., et al. (2020). The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 687–701. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0344-2

Tavakolian, A., Siavoshi, F., and Eftekhar, F. (2018). Candida albicans release intracellular bacteria when treated with amphotericin B. Arch. Iran. Med. 21, 191–198.

Thiraworawong, T., Spinler, J. K., Werawatganon, D., Klaikeaw, N., Venable, S. F., Versalovic, J., et al. (2014). Anti-inflammatory properties of gastric-derived Lactobacillus plantarum XB7 in the context of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 19, 144–155. doi: 10.1111/hel.12105

Tsai, H., and Hsu, P. (2010). Interplay between Helicobacter pylori and immune cells in immune pathogenesis of gastric inflammation and mucosal pathology. Cell Mol. Immunol. 7, 255–259. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.2

Tshibangu-Kabamba, E., and Yamaoka, Y. (2021). Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance–from biology to clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 613–629. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00449-x

Ustundag, G. H., Altuntas, H., Soysal, Y. D., and Kokturk, F. (2017). The effects of synbiotic “Bifidobacterium lactis B94 plus inulin” addition on standard triple therapy of Helicobacter pylori eradication in children. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017:8130596. doi: 10.1155/2017/8130596

Vasapolli, R., Schütte, K., Schulz, C., Vital, M., Schomburg, D., Pieper, D. H., et al. (2019). Analysis of transcriptionally active bacteria throughout the gastrointestinal tract of healthy individuals. Gastroenterology 157, 1081–1092.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.068

Viazis, N., Argyriou, K., Kotzampassi, K., Christodoulou, D., Apostolopoulos, P., Georgopoulos, S., et al. (2022). A four-probiotics regimen combined with a standard Helicobacter pylori-eradication treatment reduces side effects and increases eradication rates. Nutrients 14:632. doi: 10.3390/nu14030632

Vinasco, K., Mitchell, H. M., Kaakoush, N. O., and Castaño-Rodríguez, N. (2019). Microbial carcinogenesis: Lactic acid bacteria in gastric cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1872:188309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.07.004

Wang, F., Meng, W., Wang, B., and Qiao, L. (2014). Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 345, 196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.016

Weeks, D. L., Eskandari, S., Scott, D. R., and Sachs, G. (2000). A H+-gated urea channel: The link between Helicobacter pylori urease and gastric colonization. Science 287, 482–485. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.482

Wen, Y., Huang, H., Tang, T., Yang, H., Wang, X., Huang, X., et al. (2021). AI-2 represses CagA expression and bacterial adhesion, attenuating the Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammatory response of gastric epithelial cells. Helicobacter 26:e12778. doi: 10.1111/hel.12778

Whiteside, S., Mohiuddin, M., Shlimon, S., Chahal, J., MacPherson, C., Jass, J., et al. (2021). In vitro framework to assess the anti-Helicobacter pylori potential of lactic acid bacteria secretions as alternatives to antibiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:5650. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115650

Wu, D., Cao, M., Li, N., Zhang, A., Yu, Z., Cheng, J., et al. (2020). Effect of trimethylamine N-oxide on inflammation and the gut microbiota in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 81:106026. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106026

Wu, D., Cao, M., Peng, J., Li, N., Yi, S., Song, L., et al. (2017). The effect of trimethylamine N-oxide on Helicobacter pylori-induced changes of immunoinflammatory genes expression in gastric epithelial cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 43, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.11.032

Wu, F., Yang, L., Hao, Y., Zhou, B., Hu, J., Yang, Y., et al. (2022). Oral and gastric microbiome in relation to gastric intestinal metaplasia. Int. J. Cancer 150, 928–940. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33848

Wu, S., Xu, C., Liu, J., Liu, C., and Qiao, J. (2021). Vertical and horizontal quorum-sensing-based multicellular communications. Trends Microbiol. 29, 1130–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.04.006

Yang, H., Huang, X., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Xu, X., She, F., et al. (2022). AI-2 induces urease expression through downregulation of orphan response regulator HP1021 in Helicobacter pylori. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9:790994. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.790994

Yang, Y., Chuang, C., Yang, H., Lu, C., and Sheu, B. (2012). Lactobacillus acidophilus ameliorates H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation by inactivating the Smad7 and NFkappaB pathways. BMC Microbiol. 12:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-38

Ye, Z., Xia, H. H., Zhang, R., Li, L., Wu, L., Liu, X., et al. (2020). The efficacy of washed microbiota transplantation on Helicobacter pylori eradication: A pilot study. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2020:8825189. doi: 10.1155/2020/8825189

Yuan, Z., Xiao, S., Li, S., Suo, B., Wang, Y., Meng, L., et al. (2021). The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection, eradication therapy, and probiotics intervention on gastric microbiota in young adults. Helicobacter 26:e12848. doi: 10.1111/hel.12848

Zhang, M., Qian, W., Qin, Y., He, J., and Zhou, Y. (2015). Probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 4345–4357. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4345

Zhang, P., He, F. J., Li, Y., Li, C., Wu, J., Ma, J., et al. (2020). Reducing salt intake in China with “action on salt China” (ASC): Protocol for campaigns and randomized controlled trials. JMIR Res. Protoc. 9:e15933. doi: 10.2196/15933

Zhao, Y., Gao, X., Guo, J., Yu, D., Xiao, Y., Wang, H., et al. (2019). Helicobacter pylori infection alters gastric and tongue coating microbial communities. Helicobacter 24:e12567. doi: 10.1111/hel.12567

Zheng, W., Miao, J., Luo, L., Long, G., Chen, B., Shu, X., et al. (2021). The effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on microbiota associated with gastric mucosa and immune factors in children. Front. Immunol. 12:625586. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.625586

Zmora, N., Zilberman-Schapira, G., Suez, J., Mor, U., Dori-Bachash, M., Bashiardes, S., et al. (2018). Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to empiric probiotics is associated with unique host and microbiome features. Cell 174, 1388–1405.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.041

Keywords: gastric microecology, gastric diseases, H. pylori eradication, bacterial interaction, microbiota transplant

Citation: Zhang L, Zhao M and Fu X (2023) Gastric microbiota dysbiosis and Helicobacter pylori infection. Front. Microbiol. 14:1153269. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1153269

Received: 29 January 2023; Accepted: 14 March 2023;

Published: 30 March 2023.

Edited by:

Ozan Gundogdu, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Norma Velazquez-Guadarrama, Federico Gómez Children’s Hospital of México, MexicoCopyright © 2023 Zhang, Zhao and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ming Zhao, emhhb21pbmcyNEAxMjYuY29t; Xiangsheng Fu, ZHJmdXhzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.