94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol., 07 April 2021

Sec. Microbiotechnology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.654058

This article is part of the Research TopicEngineering Corynebacterium glutamicum Chassis for Synthetic Biology, Biomanufacturing, and BioremediationView all 20 articles

Corynebacterium glutamicum has been considered a promising synthetic biological platform for biomanufacturing and bioremediation. However, there are still some challenges in genetic manipulation of C. glutamicum. Recently, more and more genetic parts or elements (replicons, promoters, reporter genes, and selectable markers) have been mined, characterized, and applied. In addition, continuous improvement of classic molecular genetic manipulation techniques, such as allelic exchange via single/double-crossover, nuclease-mediated site-specific recombination, RecT-mediated single-chain recombination, actinophages integrase-mediated integration, and transposition mutation, has accelerated the molecular study of C. glutamicum. More importantly, emerging gene editing tools based on the CRISPR/Cas system is revolutionarily rewriting the pattern of genetic manipulation technology development for C. glutamicum, which made gene reprogramming, such as insertion, deletion, replacement, and point mutation, much more efficient and simpler. This review summarized the recent progress in molecular genetic manipulation technology development of C. glutamicum and discussed the bottlenecks and perspectives for future research of C. glutamicum as a distinctive microbial chassis.

Corynebacterium glutamicum has been widely used in the food industry for amino acid production (Wendisch et al., 2016). It is also being considered as a promising general-purpose chassis strain for other high-value chemicals (Woo and Park, 2014; Heider and Wendisch, 2015; Becker et al., 2018), as well as an emerging heterologous protein expression host (Liu et al., 2016). However, there are some challenges in developing C. glutamicum as a synthetic biology platform (Woo and Park, 2014), especially in the aspect of genome editing tools, lagging far behind Escherichia coli.

The genetic modification of C. glutamicum can be traced back to 1984 (Ozaki et al., 1984), but the development and application of genetic manipulation technology are progressing slowly (Nesvera and Patek, 2011; Suzuki and Inui, 2013; Yang et al., 2020), which may be attributed to the fact that C. glutamicum is a type of Gram-positive actinomyces with high GC content in the genome (Ikeda and Nakagawa, 2003). Unusual cell wall together with deficient homologous recombination (HR) (for DNA repair) of C. glutamicum results in extremely low efficiency in shuttle plasmid transformation and subsequent gene editing (Nesvera and Patek, 2011; Ruan et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2020). In the post-genomic era of C. glutamicum (Kalinowski et al., 2003; Lv et al., 2011, 2012), genomics and transcriptomics have promoted the mining and characterization of synthetic biological elements (such as promoters, replicons, and selectable markers) to a certain extent (Tauch et al., 2003; Nesvera et al., 2012; Patek et al., 2013; Rytter et al., 2014; Shang et al., 2018). More and more genetic manipulation tools have been applied in C. glutamicum (Nesvera and Patek, 2011; Suzuki and Inui, 2013), including type strain ATCC 13032 and no-model industrial strains such as Brevibacterium flavum and Corynebacterium crenatum (Xu et al., 2010; Shu et al., 2018). Most importantly, the gene editing technology mediated by CRISPR/Cas system has been successfully developed in C. glutamicum, revolutionizing the study of genetic manipulation technology (Jiang et al., 2017).

Here, we reviewed recent advances in genome editing technology of C. glutamicum, as summarized in Table 1, with a special focus on the CRISPR/Cas system. Technical bottlenecks and future development trends are also discussed.

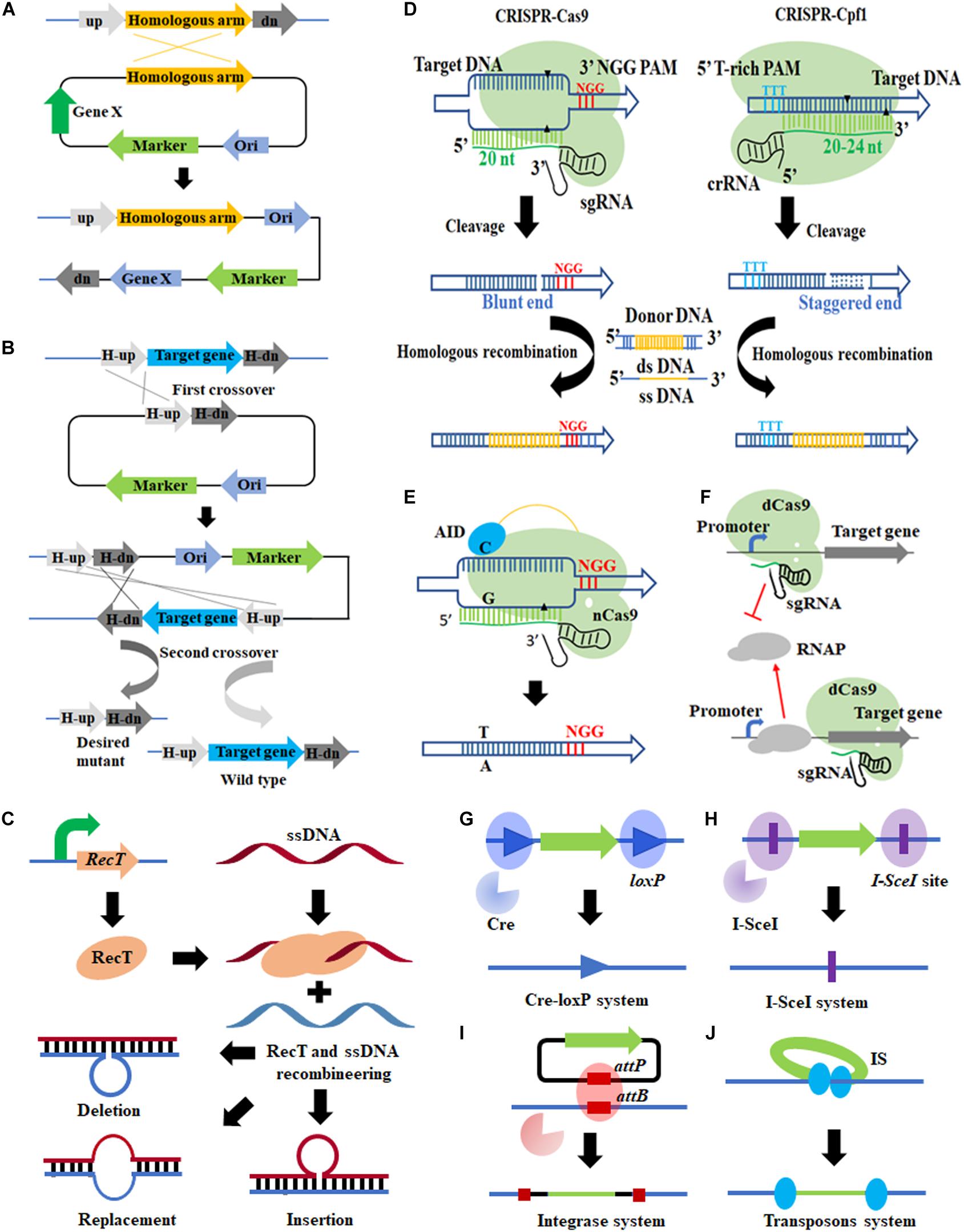

Since C. glutamicum can hardly repair DNA through Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), allelic exchange based on HR is the most commonly used genetic manipulation tool (Suzuki and Inui, 2013; Yang et al., 2020). In C. glutamicum, both suicide plasmid and replicable plasmid can be used for allelic exchange (Wang et al., 2019a; Wu et al., 2020). Allelic exchange could be achieved by single crossover and double crossover, the results of which vary dependent on the characteristic of homology arms (Figures 1A,B).

Figure 1. Genome editing tools applicable in Corynebacterium glutamicum. (A,B) Allelic exchange-based tools (single and double crossover); (C) RecT-ssDNA-mediated recombination; (D) CRISPR/Cas system; (E) CRISPR/Cas system-assisted base editing system; (F) CRISPR/Cas system-assisted transcription regulation; (G) Cre-loxP system; (H) I-SceI system; (I) integrase-mediated site-specific integration; (J) transposon.

In C. glutamicum, genetic tools based on allelic exchange can basically implement genetic manipulation such as insertion, substitution, deletion, and point mutation (Nesvera and Patek, 2011; Suzuki and Inui, 2013; Yang et al., 2020) and have been widely used in metabolic engineering and chassis development (Woo and Park, 2014). However, there are some drawbacks for allelic exchange. For example, it usually takes a long period (about 8 days) to complete one round of gene editing. Besides, the low efficiency of the second single crossover prevents the desired mutant to be obtained, even after a large number of colony PCR screening (Wen et al., 2020). To ensure the availability of desired mutant strains, counter-selectable markers and nuclease systems are introduced.

SacB gene encoding a levansucrase, which can convert sucrose into a toxic metabolite, is the most commonly used counter-selectable marker in C. glutamicum. Schäfer et al. (1994) successfully deleted the hom-thrB gene of C. glutamicum by SacB-assisted allelic exchange. In later studies, the streptomycin-sensitive gene rspl and 5-fluorouracil-lethal gene upp were also introduced as negative markers in C. glutamicum (Kim et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2015). Screening marker-mediated conditional lethality can help filter out strains that have not undergone the secondary crossover, because only strains that have lost the lethal gene through the second crossover can survive. Therefore, the screening workload is drastically reduced. However, it does not improve the efficiency of HR.

In C. glutamicum, nuclease systems such as Cre-loxP and I-SceI system (Yang et al., 2020) have been introduced to force the host to activate a second crossover (by specifically cutting DNA) to survive (Zhang et al., 2015). It not only filters out the transformants that have not undergone the second crossover but also stimulates recombination. However, low-efficiency DNA repair still hinders the acquisition of desired transformants. Therefore, the RecT recombinase system was employed. RecT is a single-stranded DNA annealing protein (SSAPs) (Zhang et al., 1998), which can mediate binding of template DNA strand and homologous DNA by annealing, to realize subsequent exchange and invasion. Accordingly, artificially synthesized ssDNA substrates can effectively achieve site-directed mutagenesis, insertion, and deletion, through recombination (Figure 1C).

RecT-mediated ssDNA single-stranded recombination does not rely on the RecA recombination system of the bacteria, but relies on the RecT recombination system encoded by the recT gene from the prophage Rac (Zhang et al., 1998). Compared with the natural recombination system in hosts, it is easier to operate and is not affected by DNA sequence and length, which can achieve high-efficiency recombination using even very short homologous DNA sequences as substrates (Murphy et al., 2000; Sawitzke et al., 2011). Binder et al. (2013) introduced RecT recombinase into C. glutamicum for the first time. In later studies, Krylov et al. (2014) and Wu et al. (2020) optimized the ssDNA chain length, concentration, base modification, and DNA strand tendency (leading or lagging strand), which further improved the recombination efficiency of ssDNA in C. glutamicum. The exonuclease–recombinase pair RecE + RecT (RecET) has also be adapted to promote dsDNA recombination. Recently, Huang et al. (2017) reported an effective and sequential deletion method based on RecET and Cre/loxP system, which has been successfully applied for L-leucine production in C. glutamicum (Luo et al., 2020).

Although RecT/ssDNA- or RecET/dsDNA-mediated recombineering simplifies the operation of genome editing, only one gene can be edited at one round in C. glutamicum. By contrast, in E. coli, oligonucleotide-mediated multiple-site editing of the genome has been successfully applied for over 10 years (Wang et al., 2009; Isaacs et al., 2011). It implied that ssDNA/dsDNA electroporation efficiency and the expression level of the RecT/RecET in C. glutamicum need to be further optimized.

The CRISPR/Cas system has achieved great success in various prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms and is regarded as a revolutionary gene manipulation technology (Jinek et al., 2012; Cong et al., 2013). A lot of effort has been paid to introduce the CRISPR/Cas system into C. glutamicum, but progress was not smooth initially, because C. glutamicum cannot tolerate the toxicity of Cas9 expression (Cho et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2017). This explains why CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) mediated by CRISPR/dCas9 [dead Cas9, harboring D10A and H840A mutations in Cas9, no nuclease activity (Bikard et al., 2013)], but not CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing, was first applied to C. glutamicum (Cleto et al., 2016).

CRISPRi can be used to regulate the transcriptional level of any given gene by steric hindrance effect (Figure 1F) and is especially suitable to down-regulate essential genes because they cannot be inactivated directly (Wen et al., 2017). In C. glutamicum, CRISPR/dCas9-mediated single-gene transcriptional repression (Cleto et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Yoon and Woo, 2018; Gauttam et al., 2019) and CRISPR-dCpf1-mediated down-regulation of multiple genes have been achieved (Liu et al., 2019; Li M. et al., 2020), but hardly no study about transcriptional activation has been reported.

As for genome editing, after observing lethality of Cas9 expression to C. glutamicum, Jiang et al. (2017) developed a gene editing tool based on Francisella novicida (Fn) CRISPR/Cpf1 (Figure 1D), in which DSB created by Cpf1 (a staggered end) can be repaired by DNA templates. When ssDNA and RecT recombination systems were introduced, more types of gene editing including gene deletion/insertion/point mutation were realized (Jiang et al., 2017). It represented a milestone in gene editing tools development of C. glutamicum and was successfully applied in six other industrial Corynebacterium strains.

Immediately after this work, breakthroughs in CRISPR/Cas9 system development were achieved. Cho et al. (2017) found that the codon optimization of the Cas9 gene reduced the toxicity of Cas9 expression; in addition, when RecT and ssDNA recombineering were employed to further facilitate recombination at the target loci, genome editing based on the CRISPR/Cas9 system in C. glutamicum was realized for the first time. In parallel studies, controlling the expression of Cas9 under an inducible promoter also achieved the goal of reducing toxicity (Liu et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2017).

The CRISPR/Cas system was subsequently optimized in the aspects of Cas9 expression stability (Wang B. et al., 2018), the convenience of curing Cas9 plasmids (Cho et al., 2017), transformation efficiency of Cas9 plasmids (Coates et al., 2019), crRNA delivery vector design (Krumbach et al., 2019), protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence, the length of the spacer sequence, and the type of repair template (Wang et al., 2019c; Zhang et al., 2019), among others. Moreover, counter-selectable markers (Zhang J. et al., 2020) and ssDNA-RecT recombination engineering (Liu et al., 2018; Wang B. et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020) have also been introduced to further optimize the gene editing system. The application of the CRISPR/Cas system has been expanded from single gene editing to multiplex gene editing and large DNA fragment deletion (Liu et al., 2017; Wang B. et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). However, it is still conditioned to the inefficient HR of C. glutamicum.

Base editing can create a missense mutation or null mutation in a gene via base substitution without introducing a DSB (Komor et al., 2016; Nishida et al., 2016), which is especially suitable for strains with inefficient HR (like C. glutamicum), and has attracted increasing attention (Wen et al., 2020). Wang Y. et al. (2018) developed a cytosine base editor (CBE) applicable in C. glutamicum based on activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Figure 1E), which can efficiently achieve C–T conversion with efficiencies up to 100%, 87.2%, and 23.3% for single-, double-, and triple-locus editing, respectively. In subsequent work, they fused tRNA adenosine deaminase from E. coli (TadA) with different Cas9 variants to construct different adenine base editors (ABEs), which can convert specific A⋅T nucleotide base pairs in the CRISPR-Cas9 targeting window sequence to G⋅C (Wang et al., 2019c). By combining the above CBE and ABE tools in one system, Deng et al. (2020) developed a bi-directional base conversion tool TadA-dCas9-AID, which achieved the base conversion of C–T, C–G, and A–G in the editing window. Most recently, Huang et al. developed a BE3 Cytidine Base Editor by fusing the cytidine deaminase (rat Apobec1), nCas9, and uracil DNA glycosylase inhibitor (UGI). It can convert C to T with a conversion efficiency up to 90% (Huang et al., 2020), which provided more tools for base editing.

Parallel to base editing tools development to explore different base transition capability, the system optimization has also made progress. Wang et al. found that some Cas9 variants can accept different PAM sequences, which increased their genome-targeting scope for base editing. Besides, base editing window was expanded from 5 to 7 bp when truncated or extended guide RNAs were adapted (Wang et al., 2019c). They also provided an online tool (gBIG1) for designing guide RNAs for base editing-mediated inactivation (Wang et al., 2019c). It is particularly exciting that an integrated robotic system-assisted automation base editing platform based on MACBETH was constructed (Wang Y. et al., 2018), which represented a new trend in future studies.

CRISPR/Cas system-based genome and base editing tools have brought the development of genetic manipulation technology into a new era due to its multiple functions, higher efficiency, shorter cycle, and more sophisticated modification over the traditional allelic exchange (Cho et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2017; Wang Y. et al., 2018). Currently, the CRISPR/Cas system is generally preferred and increasingly applied in strain breeding (Bott and Eggeling, 2017), including rapid identification of unknown genes (Lee et al., 2018), complicated metabolic engineering (Zhang J. et al., 2020), and rational genome evolution (Zhao et al., 2020).

There are some HR-independent genome editing tools applicable in C. glutamicum, such as the aforementioned Cre-loxP and I-SceI systems. Nuclease Cre mediates intramolecular recombination of two loxP sites (Figure 1G), so that the DNA sequence between the loxP sites is deleted or rearranged, leaving a loxP site in chromosome (Suzuki et al., 2005a,d). Suzuki et al. (2005c; 2005d) realized large fragment deletion and genome rearrangement in C. glutamicum using the Cre-loxP system. A total of 11 distinct genomic regions (up to 250 kb, 7.5% of the genome) were successfully deleted. A putative problem is that the loxP sites remaining in chromosome may interfere with subsequent rounds of Cre/loxP recombination (Suzuki et al., 2005a). To avoid that, a pair of mutant lox sites (lox66 and lox71) was introduced to replace the loxP site. The lox72 site, generated from Cre, caused site-specific recombination of lox66 and lox71 and cannot be recognized by Cre, which facilitated continuous Cre-lox recombination (Suzuki et al., 2005a; Hu et al., 2014).

As for the I-SceI system (Figure 1H), it consists of a homing endonuclease I-SceI and an 18-bp specific sequence (5′-TAGGGATAACAGGGTAAT-3′) (Zhang et al., 2015). The system has been adapted in C. glutamicum for genes knock-out and knock-in (Suzuki et al., 2005b; Ma et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2020). In addition, it is often used in conjunction with counter-selectable markers such as SacB, Upp, and the Cre-loxP system (Suzuki et al., 2005d; Ma et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2020).

It should be noted that the specific recognition sequence of the nuclease is difficult to customize, and the recognition site of the recombinase must be introduced into the chromosome in advance (Nesvera and Patek, 2011; Suzuki and Inui, 2013; Yang et al., 2020). It explained why site-specific recombination tools are usually used in combination with allelic exchange-based tools.

Different from Cre-loxP and I-SceI systems, transposon is a simple tool that can perform genome editing independently (Figure 1J). It can cause interruption or inactivation of some genes by random transposon insertion (Alain et al., 1994). Many transposable elements have been identified and used in C. glutamicum, such as IS31831 (Vertes et al., 1994), miniTn31831 (Alain et al., 1994), Tn14751 (Inui et al., 2005), IS1249 (Tauch et al., 1995), Tn5 (Suzuki et al., 2006), and mini-Mu (Gorshkova et al., 2018). These transposons have different transposition efficiency, sequence preference (AT-rich regions or GC-rich regions preference), and cargo delivery capacity. The combined application of different transposable elements can make up for each other’s deficiencies, thereby identifying more genes with unknown functions. For example, a combination of the miniTn31831 and Tn5 transposome systems successfully constructed a pool of 13,000 transposon mutants, equal to a library of 2300 different single-gene disruptant mutants, covering 75% of genes in C. glutamicum (Suzuki et al., 2006).

Transposon can be used not only for random knockout of single gene but also for random deletion of chromosome fragments when it is combined with nuclease systems (Goryshin et al., 2003; Tsuge et al., 2007). Random segment deletion based on IS31831 and Cre/loxP excision system has been applied for genome reduction of C. glutamicum by random deletion of DNA fragments (Tsuge et al., 2007). Compared with conventional strategies (genomic analysis combined with precise deletion) (Baumgart et al., 2013, 2016, 2018; Unthan et al., 2015), this strategy has been considered as a faster way to create a minimum bacterial genome (Suzuki and Inui, 2013).

Unfortunately, transposons are rarely used for random integration of heterogenous genes, because the length of cargo fragments is usually limited (Gorshkova et al., 2018). By contrast, integrase-mediated site-directed integration of heterologous genes can integrate fragments up to tens of kb (Figure 1I) (Huang et al., 2019). Shen et al. (2017) employed a phage integrase TP901-1-mediated chromosomal integration method in C. glutamicum, which realized the integration of two reporter genes, implying good application potential. In another study, Marques et al. (2020) developed two markerless integrative systems, respectively, based on actinophage ϕC31 and ϕBT1 for stable inheritance of the introduced genetic traits. Similar to the Cre-loxP and I-SceI system, the prerequisite for integrase-mediated site-directed integration is that the attB site has been integrated into the chromosome by allelic exchange in advance (Shen et al., 2017; Marques et al., 2020). To realize one-step site-directed integration, Strecker et al. (2019) and Klompe et al. (2019), respectively, developed CRISPR-associated transposon-mediated RNA-guided programmable DNA integration methods in E. coli. These methods do not rely on HR and have achieved multi-site and multi-copy integration of heterologous genes in E. coli and Tatumella citrea (Vo et al., 2020; Zhang Y. et al., 2020). It is expected to be introduced into C. glutamicum for high-efficiency, multiplexed chromosome integration.

Table 1 summarizes and compares the principles, effects, advantages, and putative drawbacks of various genetic manipulation tools in C. glutamicum. According to the table, the CRISPR/Cas system has obvious advantages over other methods but is far from perfect. Classic tools such as counter-selectable markers, ssDNA-RecT recombineering, transposons, and nuclease could be employed in the CRISPR/Cas system to further improve efficiency and expand functions. The combination of different genetic manipulation tools to achieve new editing purposes has become a trend (Suzuki and Inui, 2013; Yang et al., 2020). Besides, many efforts have been paid to overcome barriers to introduce these tools to non-model Corynebacterium strains (Jiang et al., 2017; Coates et al., 2019).

Synthetic biology is profoundly rewriting the development pattern of genetic modification of C. glutamicum. Artificial intelligence-assisted massive omics data mining may greatly enrich the genetic element library of C. glutamicum; advanced models or algorithms could rationally guide chassis cells design; coupled with a new generation of high-throughput, automated biological casting platform, they should enable the future development of more effective C. glutamicum.

QW, XS, and ZW conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion, revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21706133, 21825804, 31670094, and 31971343), the Funds for Creative Research Groups of China (31921006), and the Key Laboratory of Biomass Chemical Engineering of Ministry of Education, Zhejiang University (2018BCE003).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alain, A. V., Asai, Y., Inui, M., Kobayashi, M., Kurusu, Y., and Yukawa, H. (1994). Transposon mutagenesis of coryneform bacteria. Mol. Gen. Genet. 245, 397–405.

Baumgart, M., Unthan, S., Kloss, R., Radek, A., Polen, T., Tenhaef, N., et al. (2018). Corynebacterium glutamicum chassis C1∗: building and testing a novel platform host for synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology. Acs Synth. Biol. 7, 132–144. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00261

Baumgart, M., Unthan, S., Radek, A., Herbst, M., Siebert, D., Bruehl, N., et al. (2016). Chassis organism from Corynebacterium glutamicum–Genome reduction as a tool toward improved strains for synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology. N. Biotechnol. 33, S25–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2016.06.814

Baumgart, M., Unthan, S., Rueckert, C., Sivalingam, J., Gruenberger, A., Kalinowski, J., et al. (2013). Construction of a prophage-free variant of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 for use as a platform strain for basic research and industrial biotechnology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6006–6015. doi: 10.1128/aem.01634-13

Becker, J., Rohles, C. M., and Wittmann, C. (2018). Metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum for bio-based production of chemicals, fuels, materials, and healthcare products. Metab. Eng. 50, 122–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.07.008

Bikard, D., Jiang, W. Y., Samai, P., Hochschild, A., Zhang, F., and Marraffini, L. A. (2013). Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 7429–7437.

Binder, S., Siedler, S., Marienhagen, J., Bott, M., and Eggeling, L. (2013). Recombineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum combined with optical nanosensors: a general strategy for fast producer strain generation. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 6360–6369. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt312

Bott, M., and Eggeling, L. (2017). “Novel technologies for optimal strain breeding,” in Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology: Amino Acid Fermentation, eds A. Yokota and M. Ikeda (Tokyo: Springer Japan), 227–254. doi: 10.1007/10_2016_33

Cho, J. S., Choi, K. R., Prabowo, C. P. S., Shin, J. H., Yang, D., Jang, J., et al. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-coupled recombineering for metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab. Eng. 42, 157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.06.010

Cleto, S., Jensen, J. V. K., Wendisch, V. F., and Lu, T. K. (2016). Corynebacterium glutamicum metabolic engineering with CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 375–385. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00216

Coates, R. C., Blaskowski, S., Szyjka, S., van Rossum, H. M., Vallandingham, J., Patel, K., et al. (2019). Systematic investigation of CRISPR-Cas9 configurations for flexible and efficient genome editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum NRRL-B11474. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 46, 187–201. doi: 10.1007/s10295-018-2112-7

Cong, L., Ran, F. A., Cox, D., Lin, S., Barretto, R., Habib, N., et al. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/cas systems. Science 339, 819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143

Deng, C., Lv, X., Li, J., Liu, Y., Du, G., and Liu, L. (2020). Development of a DNA double-strand break-free base editing tool in Corynebacterium glutamicum for genome editing and metabolic engineering. Metab. Eng. Commun. 11:e00135. doi: 10.1016/j.mec.2020.e00135

Dong, J., Kan, B., Liu, H., Zhan, M., Wang, S., Xu, G., et al. (2020). CRISPR-Cpf1-assisted engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum SNK118 for enhanced l-ornithine production by NADP-Dependent Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase and NADH-Dependent Glutamate Dehydrogenase. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 191, 955–967. doi: 10.1007/s12010-020-03231-y

Gauttam, R., Seibold, G. M., Mueller, P., Weil, T., Weiss, T., Handrick, R., et al. (2019). A simple dual-inducible CRISPR interference system for multiple gene targeting in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Plasmid 103, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2019.04.001

Gorshkova, N. V., Lobanova, J. S., Tokmakova, I. L., Smirnov, S. V., Akhverdyan, V. Z., Krylov, A. A., et al. (2018). Mu-driven transposition of recombinant mini-Mu unit DNA in the Corynebacterium glutamicum chromosome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 2867–2884. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8767-1

Goryshin, I. Y., Naumann, T. A., Apodaca, J., and Reznikoff, W. S. (2003). Chromosomal deletion formation system based on Tn5 double transposition: use for making minimal genomes and essential gene analysis. Genome Res. 13, 644–653.

Heider, S. A. E., and Wendisch, V. F. (2015). Engineering microbial cell factories: metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum with a focus on non-natural products. Biotechnol. J. 10, 1170–1184. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400590

Hu, J., Li, Y., Zhang, H., Tan, Y., and Wang, X. (2014). Construction of a novel expression system for use in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Plasmid 75, 18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2014.07.005

Huang, H., Bai, L., Liu, Y., Li, J., Wang, M., and Hua, E. (2020). Development and application of BE3 cytidine base editor in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol. Bull. 36, 95–101.

Huang, H., Chai, C., Yang, S., Jiang, W., and Gu, Y. (2019). Phage serine integrase-mediated genome engineering for efficient expression of chemical biosynthetic pathway in gas-fermenting Clostridium ljungdahlii. Metab. Eng. 52, 293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.01.005

Huang, Y., Li, L., Xie, S., Zhao, N., Han, S., Lin, Y., et al. (2017). Recombineering using RecET in Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC14067 via a self-excisable cassette. Sci. Rep. 7:7916. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08352-9

Ikeda, M., and Nakagawa, S. (2003). The Corynebacterium glutamicum genome: features and impacts on biotechnological processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 62, 99–109. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1328-1

Inui, M., Tsuge, Y., Suzuki, N., Vertes, A. A., and Yukawa, H. (2005). Isolation and characterization of a native composite transposon, Tn14751, carrying 17.4 kilobases of Corynebacterium glutamicum chromosomal DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 407–416. doi: 10.1128/aem.71.1.407-416.2005

Isaacs, F. J., Carr, P. A., Wang, H. H., Lajoie, M. J., Sterling, B., Kraal, L., et al. (2011). Precise manipulation of chromosomes in vivo enables genome-wide codon replacement. Science 333, 348–353.

Jiang, Y., Qian, F., Yang, J., Liu, Y., Dong, F., Xu, C., et al. (2017). CRISPR-Cpf1 assisted genome editing of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Nat. Commun. 8:15179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15179

Jinek, M., Chylinski, K., Fonfara, I., Hauer, M., Doudna, J. A., and Charpentier, E. (2012). A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829

Kalinowski, J., Bathe, B., Bartels, D., Bischoff, N., Bott, M., Burkovski, A., et al. (2003). The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of L-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J. Biotechnol. 104, 5–25. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(03)00154-8

Kim, I. K., Jeong, W. K., Lim, S. H., Hwang, I. K., and Kim, Y. H. (2011). The small ribosomal protein S12P gene rpsL as an efficient positive selection marker in allelic exchange mutation systems for Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Microbiol. Methods 84, 128–130. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.10.007

Klompe, S. E., Vo, P. L. H., Halpin-Healy, T. S., and Sternberg, S. H. (2019). Transposon-encoded CRISPR-Cas systems direct RNA-guided DNA integration. Nature 571, 219–225. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1323-z

Komor, A. C., Kim, Y. B., Packer, M. S., Zuris, J. A., and Liu, D. R. (2016). Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424.

Krumbach, K., Sonntag, C. K., Eggeling, L., and Marienhagen, J. (2019). CRISPR/Cas12a mediated genome editing to introduce amino acid substitutions into the mechanosensitive channel MscCG of Corynebacterium glutamicum. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 2726–2734. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00361

Krylov, A. A., Kolontaevsky, E. E., and Mashko, S. V. (2014). Oligonucleotide recombination in corynebacteria without the expression of exogenous recombinases. J. Microbiol. Methods 105, 109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.07.028

Lee, S. S., Shin, H., Jo, S., Lee, S.-M., Um, Y., and Woo, H. M. (2018). Rapid identification of unknown carboxyl esterase activity in Corynebacterium glutamicum using RNA-guided CRISPR interference. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 114, 63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2018.04.004

Li, J., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, P., Zheng, P., and Wang, M. (2020). Optimization of base editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 36, 143–151. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.190192

Li, M., Chen, J., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Huang, J., Chen, N., et al. (2020). Efficient multiplex gene repression by CRISPR-dCpf1 in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:357. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00357

Liu, J., Wang, Y., Lu, Y., Zheng, P., Sun, J., and Ma, Y. (2017). Development of a CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing toolbox for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Cell Fact. 16:205. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0815-5

Liu, J., Wang, Y., Zheng, P., and Sun, J. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated ssDNA Recombineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Bio Protoc. 8:e3038. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3038

Liu, W., Tang, D., Wang, H., Lian, J., Huang, L., and Xu, Z. (2019). Combined genome editing and transcriptional repression for metabolic pathway engineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum using a catalytically active Cas12a. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 8911–8922. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10118-4

Liu, X., Yang, Y., Zhang, W., Sun, Y., Peng, F., Jeffrey, L., et al. (2016). Expression of recombinant protein using Corynebacterium Glutamicum: progress, challenges and applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 36, 652–664. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2015.1004519

Luo, G., Zhao, N., Jiang, S., and Zheng, S. (2020). Application of RecET-Cre/loxPsystem in Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC14067 forl-leucine production. Biotechnol. Lett 43, 297–306. doi: 10.1007/s10529-020-03000-1

Lv, Y., Liao, J., Wu, Z., Han, S., Lin, Y., and Zheng, S. (2012). Genome Sequence of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 14067, which provides insight into amino acid biosynthesis in coryneform bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 194, 742–743. doi: 10.1128/jb.06514-11

Lv, Y., Wu, Z., Han, S., Lin, Y., and Zheng, S. (2011). Genome sequence of Corynebacterium glutamicum S9114, a strain for industrial production of glutamate. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6096–6097. doi: 10.1128/jb.06074-11

Ma, W., Wang, X., Mao, Y., Wang, Z., Chen, T., and Zhao, X. (2015). Development of a markerless gene replacement system in Corynebacterium glutamicum using upp as a counter-selection marker. Biotechnol. Lett. 37, 609–617. doi: 10.1007/s10529-014-1718-8

Marques, F., Luzhetskyy, A., and Mendes, M. V. (2020). Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum with a comprehensive genomic library and phage-based vectors. Metab. Eng. 62, 221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.08.007

Murphy, K. C., Campellone, K. G., and Poteete, A. R. (2000). PCR-mediated gene replacement in Escherichia coli. Gene 246, 321–330.

Nesvera, J., Holatko, J., and Patek, M. (2012). Analysis of Corynebacterium glutamicum promoters and their applications. Subcell. Biochem. 64, 203–221. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5055-5_10

Nesvera, J., and Patek, M. (2011). Tools for genetic manipulations in Corynebacterium glutamicum and their applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 90, 1641–1654. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3272-9

Niebisch, A., and Bott, M. (2001). Molecular analysis of the cytochrome bc1-aa3 branch of the Corynebacterium glutamicum respiratory chain containing an unusual diheme cytochrome c1. Arch. Microbiol. 175, 282–294. doi: 10.1007/s002030100262

Nishida, K., Arazoe, T., Yachie, N., Banno, S., Kakimoto, M., Tabata, M., et al. (2016). Targeted nucleotide editing using hybrid prokaryotic and vertebrate adaptive immune systems. Science 353:aaf8729.

Ozaki, A., Katsumata, R., Oka, T., and Furuya, A. (1984). Functional expression of the genes of Escherichia coli in gram-positive Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 196, 175–178. doi: 10.1007/bf00334113

Patek, M., Holatko, J., Busche, T., Kalinowski, J., and Nesvera, J. (2013). Corynebacterium glutamicum promoters: a practical approach. Microb. Biotechnol. 6, 103–117. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12019

Peng, F., Wang, X., Sun, Y., Dong, G., Yang, Y., Liu, X., et al. (2017). Efficient gene editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Microb. Cell Fact. 16:201. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0814-6

Ruan, Y., Zhu, L., and Li, Q. (2015). Improving the electro-transformation efficiency of Corynebacterium glutamicum by weakening its cell wall and increasing the cytoplasmic membrane fluidity. Biotechnol. Lett. 37, 2445–2452. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1934-x

Rytter, J. V., Helmark, S., Chen, J., Lezyk, M. J., Solem, C., and Jensen, P. R. (2014). Synthetic promoter libraries for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 2617–2623. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5481-x

Sawitzke, J. A., Costantino, N., Li, X. T., Thomason, L. C., Bubunenko, M., Court, C., et al. (2011). Probing cellular processes with oligo-mediated recombination and using the knowledge gained to optimize recombineering. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 45–59.

Schafer, A., Tauch, A., Jager, W., Kalinowski, J., Thierbach, G., and Puhler, A. (1994). Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7

Shang, X., Chai, X., Lu, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, G., et al. (2018). Native promoters of Corynebacterium glutamicum and its application in l-lysine production. Biotechnol. Lett. 40, 383–391. doi: 10.1007/s10529-017-2479-y

Shen, J., Chen, J., Jensen, P. R., and Solem, C. (2017). A novel genetic tool for metabolic optimization of Corynebacterium glutamicum: efficient and repetitive chromosomal integration of synthetic promoter-driven expression libraries. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 4737–4746. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8222-8

Shu, Q., Xu, M., Li, J., Yang, T., Zhang, X., Xu, Z., et al. (2018). Improved l-ornithine production in Corynebacterium crenatum by introducing an artificial linear transacetylation pathway. J. Indust. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 45, 393–404. doi: 10.1007/s10295-018-2037-1

Strecker, J., Ladha, A., Gardner, Z., Schmid-Burgk, J. L., Makarova, K. S., Koonin, E. V., et al. (2019). RNA-guided DNA insertion with CRISPR-associated transposases. Science 365, 48–53. doi: 10.1126/science.aax9181

Su, T., Jin, H., Zheng, Y., Zhao, Q., Chang, Y., Wang, Q., et al. (2018). Improved ssDNA recombineering for rapid and efficient pathway engineering in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93, 3535–3542. doi: 10.1002/jctb.5726

Suzuki, N., and Inui, M. (2013). Genome Engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Berlin: Springer.

Suzuki, N., Nonaka, H., Tsuge, Y., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2005a). New multiple-deletion method for the Corynebacterium glutamicum genome, using a mutant lox sequence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8472–8480. doi: 10.1128/aem.71.12.8472-8480.2005

Suzuki, N., Nonaka, H., Tsuge, Y., Okayama, S., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2005b). Multiple large segment deletion method for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69, 151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1976-4

Suzuki, N., Okai, N., Nonaka, H., Tsuge, Y., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2006). High-throughput transposon mutagenesis of Corynebacterium glutamicum and construction of a single-gene disruptant mutant library. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3750–3755. doi: 10.1128/aem.72.5.3750-3755.2006

Suzuki, N., Okayama, S., Nonaka, H., Tsuge, Y., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2005c). Large-scale engineering of the Corynebacterium glutamicum genome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3369–3372. doi: 10.1128/aem.71.6.3369-3372.2005

Suzuki, N., Tsuge, Y., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2005d). Cre/loxP-mediated deletion system for large genome rearrangements in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67, 225–233. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1772-6

Tauch, A., Kassing, F., Kalinowski, J. R., and Alfred, P. (1995). The erythromycin resistance gene of the Corynebacterium xerosis R-plasmid pTP10 also carrying chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and tetracycline resistances is capable of transposition in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Plasmid 33, 168–179.

Tauch, A., Puhler, A., Kalinowski, J., and Thierbach, G. (2003). Plasmids in Corynebacterium glutamicum and their molecular classification by comparative genomics. J. Biotechnol. 104, 27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(03)00157-3

Tsuge, Y., Suzuki, N., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2007). Random segment deletion excision system in based on IS31831 and Cre/loxP Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74, 1333–1341. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0788-5

Unthan, S., Baumgart, M., Radek, A., Herbst, M., Siebert, D., Bruehl, N., et al. (2015). Chassis organism from Corynebacterium glutamicum–a top-down approach to identify and delete irrelevant gene clusters. Biotechnol. J. 10, 290–301. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400041

Vertes, A. A., Inui, M., Kobayashi, M., Kurusu, Y., and Yukawa, H. (1994). Isolation and characterization of IS31831, a transposable element from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol. Microbiol. 11, 739–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00351.x

Vo, P. L. H., Ronda, C., Klompe, S. E., Chen, E. E., Acree, C., Wang, H. H., et al. (2020). CRISPR RNA-guided integrases for high-efficiency, multiplexed bacterial genome engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-00745-y

Wang, B., Hu, Q., Zhang, Y., Shi, R., Chai, X., Liu, Z., et al. (2018). A RecET-assisted CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Cell Fact. 17:63. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0910-2

Wang, H. H., Isaacs, F. J., Carr, P. A., Sun, Z. Z., Xu, G., Forest, C. R., et al. (2009). Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. Nature 460, 894–898.

Wang, T., Li, Y., Li, J., Zhang, D., Cai, N., Zhao, G., et al. (2019a). An update of the suicide plasmid-mediated genome editing system in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Biotechnol. 12, 907–919. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13444

Wang, T., Ma, H., Zhao, G., Cai, N., Zhang, D., and Chen, N. (2019b). Optimization of a CRISPR-Cpf1/ssDNA genome editing system for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Food Ferment. Ind. 45, 1–7.

Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Li, J., Yang, Y., Ni, X., Cheng, H., et al. (2019c). Expanding targeting scope, editing window, and base transition capability of base editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116, 3016–3029. doi: 10.1002/bit.27121

Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, J., Guo, Y., Fan, L., Ni, X., et al. (2018). MACBETH: multiplex automated Corynebacterium glutamicum base editing method. Metab. Eng. 47, 200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.02.016

Wen, Z., Lu, M., Ledesma-Amaro, R., Li, Q., Jin, M., and Yang, S. (2020). TargeTron technology applicable in Solventogenic Clostridia: revisiting 12 years’. Adv. Biotechnol. J. 15:e1900284. doi: 10.1002/biot.201900284

Wen, Z., Minton, N. P., Zhang, Y., Li, Q., Liu, J., Jiang, Y., et al. (2017). Enhanced solvent production by metabolic engineering of a twin-clostridial consortium. Metab. Eng. 39, 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.10.013

Wendisch, V. F., Jorge, J. M. P., Perez-Garcia, F., and Sgobba, E. (2016). Updates on industrial production of amino acids using Corynebacterium glutamicum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32:105. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2060-1

Woo, H. M., and Park, J. B. (2014). Recent progress in development of synthetic biology platforms and metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 180, 43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.03.003

Wu, M., Xu, Y., Yang, J., and Shang, G. (2020). Homing endonuclease I-SceI-mediated Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 3597–3609. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10517-y

Xu, D., Tan, Y., Huan, X., Hu, X., and Wang, X. (2010). Construction of a novel shuttle vector for use in Brevibacterium flavum, an industrial amino acid producer. J. Microbiol. Methods 80, 86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.11.003

Yang, J., Ma, X., Wang, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, S., Qin, H., et al. (2020). Advances in gene editing of Corynebacterium glutamate. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 36, 820–828. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.190403

Yoon, J., and Woo, H. M. (2018). CRISPR interference-mediated metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for homo-butyrate production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 115, 2067–2074. doi: 10.1002/bit.26720

Zhan, M., Kan, B., Zhang, H., Dong, J., Xu, G., Han, R., et al. (2019). Comparison of CRISPR-Cpf1 with Cre/loxP for gene knockout in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiol. China 46, 278–291. doi: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.180225

Zhang, J., Qian, F., Dong, F., Wang, Q., Yang, J., Jiang, Y., et al. (2020). De novo engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-proline production. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 1897–1906. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00249

Zhang, J., Yang, F., Yang, Y., Jiang, Y., and Huo, Y.-X. (2019). Optimizing a CRISPR-Cpf1-based genome engineering system for Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microb. Cell Fact. 18:60. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1109-x

Zhang, N., Shao, L., Jiang, Y., Gu, Y., Li, Q., Liu, J., et al. (2015). I-SceI-mediated scarless gene modification via allelic exchange in Clostridium. J. Microbiol. Methods 108, 49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.11.004

Zhang, Y., Buchholz, F., Muyrers, J. P., and Stewart, F. A. (1998). A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Genet. 20, 123–128. doi: 10.1038/2417

Zhang, Y., Sun, X., Wang, Q., Xu, J., Dong, F., Yang, S., et al. (2020). Multicopy chromosomal integration using CRISPR-associated transposases. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 1998–2008. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00073

Keywords: Corynebacterium, molecular genetic modification, CRISPR/Cas system, genome editing, toolbox

Citation: Wang Q, Zhang J, Al Makishah NH, Sun X, Wen Z, Jiang Y and Yang S (2021) Advances and Perspectives for Genome Editing Tools of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front. Microbiol. 12:654058. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.654058

Received: 15 January 2021; Accepted: 01 March 2021;

Published: 07 April 2021.

Edited by:

Yu Wang, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaReviewed by:

Suiping Zheng, South China University of Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Wang, Zhang, Al Makishah, Sun, Wen, Jiang and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhiqiang Wen, enF3ZW5AbmpudS5lZHUuY24=; enF3ZW5Abmp1c3QuZWR1LmNu; Xiaoman Sun, eGlhb21hbnN1bkBuam51LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.