94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 21 February 2024

Sec. Institutions and Collective Action

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2024.1355421

This article is part of the Research Topic The Socioeconomic Dynamics of Settling Down View all 8 articles

Indigenous peoples have occupied eastern North America for over 10,000 years; yet the earliest anthropomorphic figurines were only manufactured in the past several thousand years. This emergence of human figurine traditions in eastern North America is correlated with increased settlement permanence, and community size related to key demographic thresholds. In this study, I present an overview of two previously unreported figurine assemblages from the Middle Woodland period in Illinois and use these assemblages as a jumping-off point to examine the emergence of early human figurines in eastern North America. To illustrate the importance of the correlation between anthropomorphic figurines and settling down, I focus on what figurines do that encouraged the emergence of widespread traditions of figurine manufacture and use as the size of affiliative communities increased. This study involves examining early figurines and their broader context through the lens of a model of the socioeconomic dynamics of settling down in conjunction with an examination of the materiality of miniature 3-D anthropomorphic figurines. Key to this latter perspective is understanding not what figurines represent but what they do.

This study focuses on early anthropomorphic clay figurines in eastern North America and the timing of their appearance in relation to periods of important changes in settlement, community, and ceremonialism. I interrogate the nature of these correlations by asking what figurines do that encouraged the emergence of widespread traditions of figurine manufacture and use as people were settling down? Answering this question involves examining early figurines and their broader context through a model of the socioeconomic dynamics of settling down (Feinman and Neitzel, 2023) in conjunction with the materiality of miniature 3-D anthropomorphic figurines (i.e., Bailey, 2005). To build this argument, I present an overview of two previously unreported figurine assemblages from the Middle Woodland period in Illinois and use these as a jumping-off point to discuss the emergence of early human figurines in eastern North America. Overall, this example illustrates general patterns and important variations associated with alternative pathways to settling down and making anthropomorphic figurines.

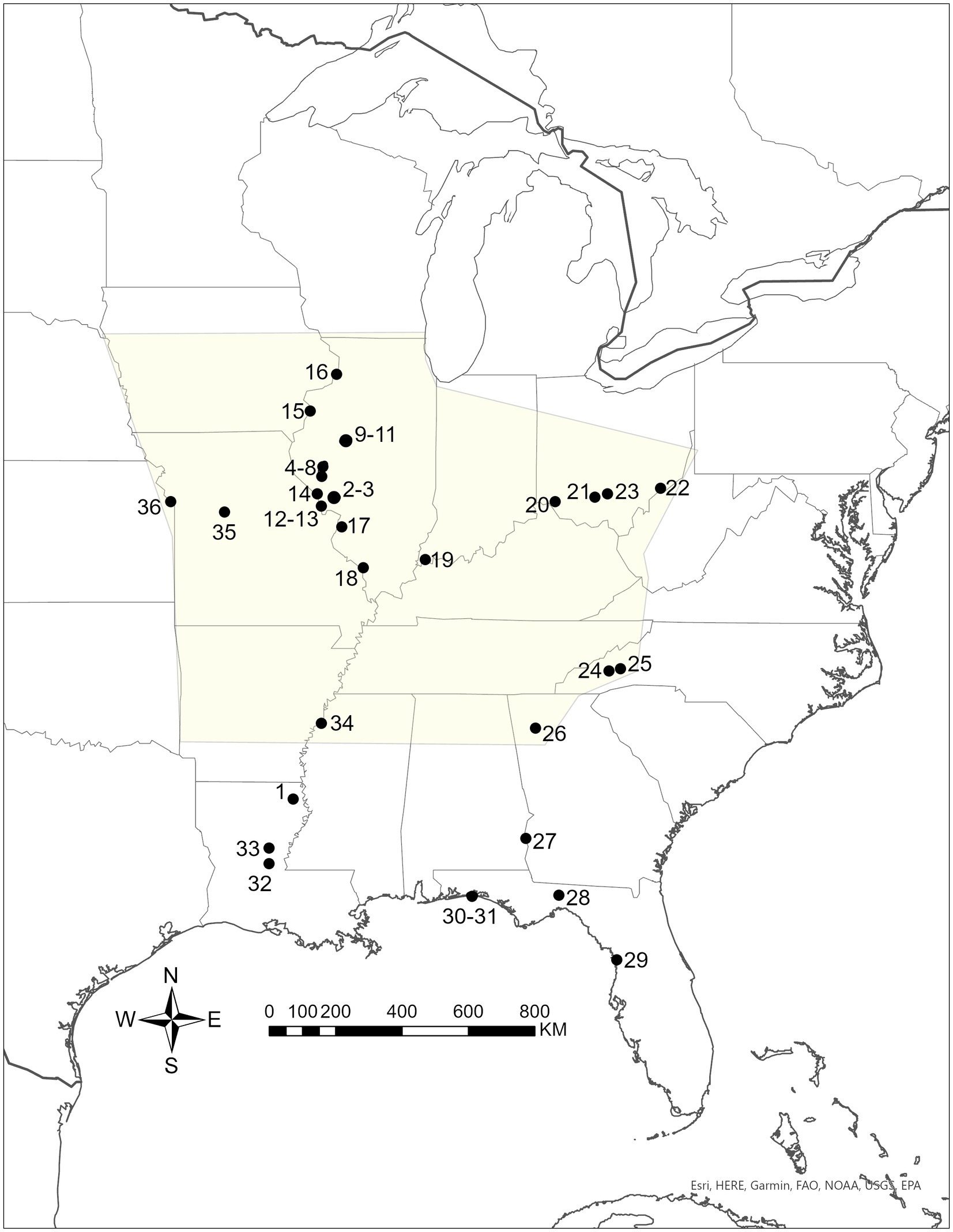

The first widespread anthropomorphic figurine tradition in the region occurs during the Middle Woodland period (circa 100 BCE–400 CE).1 These clay figurines have been recovered from dozens of settlements and mounds across eastern North America from Kansas to North Carolina and from Illinois to Florida (Figure 1). My focus here is on clay figurines as these are the most ubiquitous anthropomorphic objects while acknowledging that these are part of a larger pattern of human representation that emerges in the Middle Woodland.2

Figure 1. Map of sites with figurines mentioned in text. (1) Poverty Point; (2) Loy; (3) Crane; (4) Smiling Dan; (5) Pool; (6) Irving; (7) Baehr; (8) Blue Creek; (9) Clear Lake; (10) Weaver; (11) Whitnah; (12) Snyders; (13) Peisker; (14) Knight/Ansell; (15) Putney Landing; (16) Albany; (17) American Bottom; (18) Twenhafel; (19) Mann; (20) Turner; (21) Seip; (22) Marietta; (23) McGraw; (24) Garden Creek; (25) Biltmore; (26) Leake; (27) Mandeville; (28) Crystal River; (29) Block-Sterns; (30) Buck; (31) Bell; (32) Marksville; (33) Crooks; (34) Dickerson; (35) Mellor; (36) Trowbridge. Shaded area represents the extent of Eastern Agricultural Complex plant cultivation in the Middle Woodland based on Mueller et al. (2020, Figure 1) edited to include portions of North Carolina due to evidence for Middle Woodland cultivars/domesticates in the region (Kimball et al., 2010; Wright, 2020).

The Middle Woodland period of eastern North America is generally characterized as a time of fluorescence of burial ceremonialism, monumental earthen construction, and artistry, which is commonly referred to as Hopewell (Seeman, 2004, 2020; Charles and Buikstra, 2006; Abrams, 2009; Wright and Henry, 2013; Miller, 2021; Carr, 2022). Application of the Hopewell label over geographically widespread practices masks extensive diversity (see chapters in Brose, 1979). Concepts such as glocalization (Wright, 2020) and situations such as that described in the study of Henry and Miller (2020) highlight recent attempts to analyze Middle Woodland ceremonialism as variable, multi-scalar dialectic relationships between large scale processes and local developments. It is equally difficult to briefly summarize other aspects of life in this period, but generally Middle Woodland subsistence changes include the increased cultivation of indigenous seed crops to the point of low-level food production in the central interior of eastern North America but not near the coasts (Smith, 1992). Settlement is characterized by population concentration in river valleys perhaps concomitant with stabilization of these ecosystems after centuries of fluctuation (Charles, 2012).

In the central Illinois River valley, small, dispersed settlements and the use of crypt-ramp burial mounds appear by the last century BCE (Struever, 1965, 1968; Ruby et al., 2005). By approximately 50 BCE, settlement expanded south into the largely unoccupied lower Illinois river valley, as evidenced by the bluff-top mound groups that were constructed in a generally north to south chronological trend over several hundred years (Buikstra and Charles, 1999; Ruby et al., 2005; King et al., 2011; Herrmann et al., 2014; Farnsworth and Atwell, 2015, p. 199). In addition to burial ceremonialism, the mound groups were centers of feasting, exchange, and social interaction for communities who periodically gathered at these sites (Struever and Houart, 1972; Buikstra and Charles, 1999; Henry et al., 2021; Weiland et al., 2023). In the Illinois valley, ceremonial gatherings at the mound groups were integral to the formation and maintenance of communities where bluff-top mound groups generally served smaller communities than floodplain mound centers (e.g., Ruby et al., 2005, p. 136). Day-to-day occupation did not occur at mound centers but dispersed habitation sites, aka hamlets, throughout the Illinois and tributary valleys. Individual hamlets generally provided evidence of one to three contemporaneous households (Struever, 1968; Asch et al., 1979; Stafford and Sant, 1985; Ruby et al., 2005). In the intensively studied lower Illinois valley, individual habitations often “cluster in groups of two or three and upward to five, with 0.8 to 1.6 kilometers between hamlets in a cluster and much larger distances among clusters” (Ruby et al., 2005, p. 134).

My foray into figurines began with an examination of the figurine assemblage from Loy and Crane, two Middle Woodland settlements in a tributary valley of the lower Illinois River (Asch and Asch, 1985, p. 205–208; Carr, 1982; Miller and Farnsworth, 2023). The figurines from Loy and Crane are not particularly remarkable in terms of detail compared with other reported examples from the Middle Woodland period (e.g., McKern et al., 1945). Nevertheless, they are certainly valuable as additional data. Additionally, their lack of detail encouraged me to look beyond what they are representations of (sensu Bailey, 2005) for inspiration. Thus, I report these figurines here as a jumping-off point on early figurines in eastern North America.

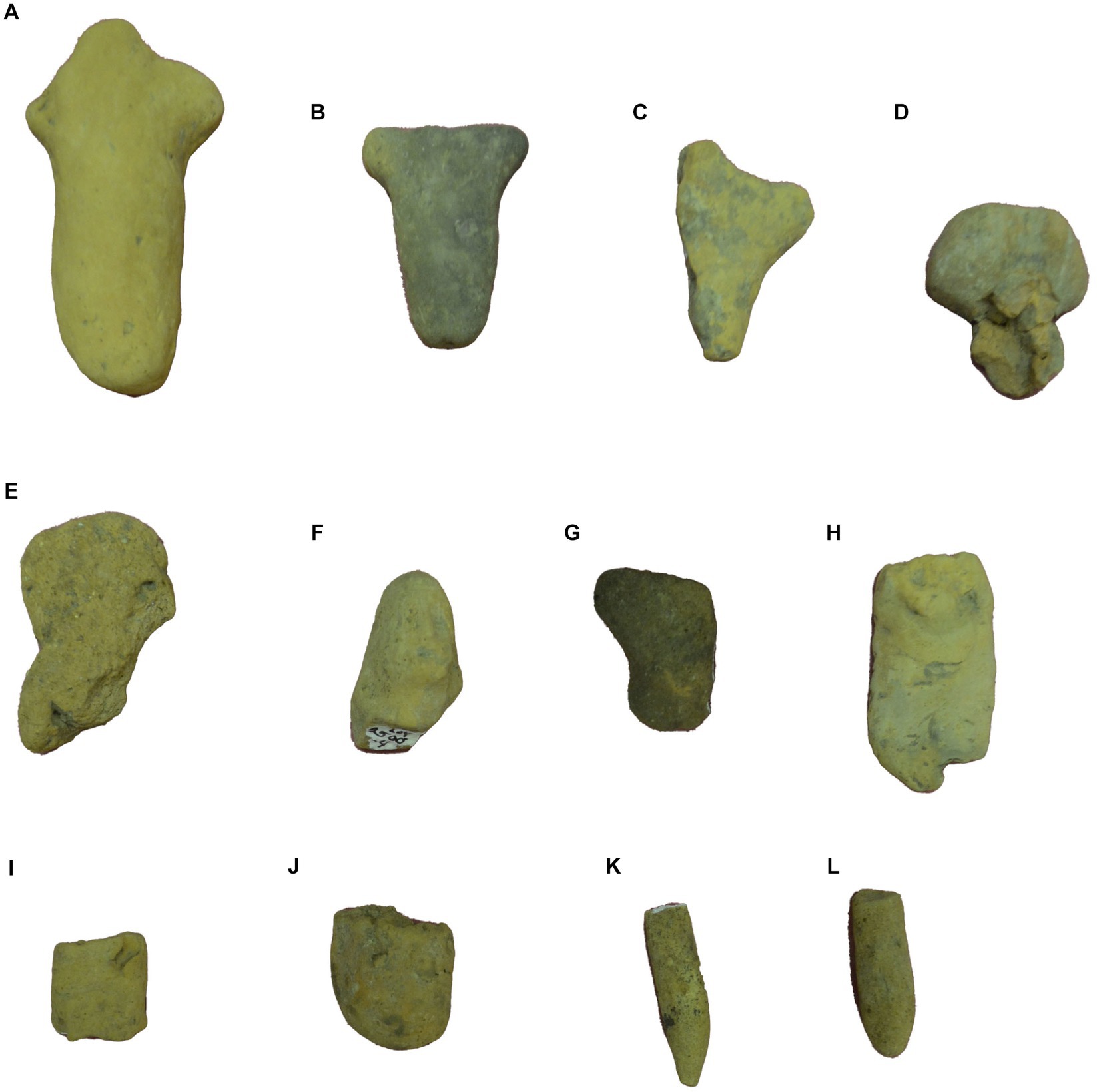

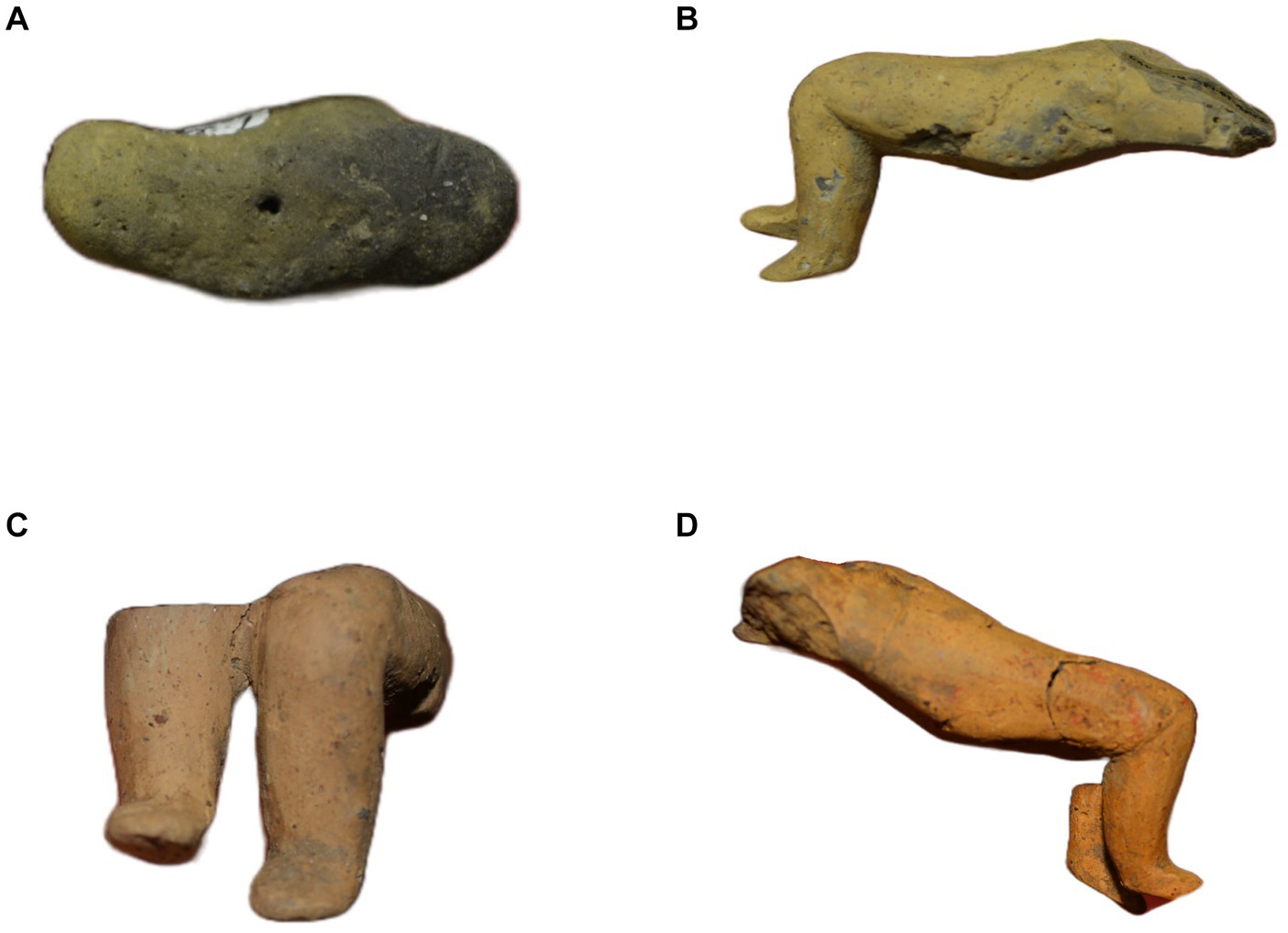

Loy and Crane were investigated via surface collection and excavation, both of random test units and larger excavation blocks, by crews from the Center for American Archeology, under the direction of Ken Farnsworth, in the early to mid-1970s. The absence of mounds or ancestor burials, the high proportion of Havana as opposed to Hopewell series ceramics, and the preponderance of pits, posts, and habitation debris all indicate that Loy and Crane were the loci of everyday settlements as opposed to mortuary centers or ritual camps (Asch and Asch, 1985, p. 205–208; Carr, 1982; Miller and Farnsworth, 2023). Over two dozen total figurine fragments were recovered, but no complete figurines were present in either assemblage (Figures 2, 3). Figurines were recovered across each site from surface, plowzone, and pit feature contexts. However, only one feature contained more than one figurine fragment, and there is no evidence to suggest that any figurines were deposited in caches or other formal deposits that differed from other materials.

Figure 2. Figurines from Loy. Each specimen assigned a sequential letter (A–L) starting top left to bottom right for identification in text.

Figure 3. Figurines from Crane. Each specimen assigned a sequential letter (A–O) starting top left to bottom right for identification in text.

Most figurines have little detail beyond the general shape of a torso, shoulders, nubs for arms, and a relatively featureless lower body, giving rise to the local moniker of “Casper the Ghost” style (Struever and Houart, 1972, p. 73) due to the similarity to the eponymous pop culture character (Figures 2A–D,F, 3B,D,I,J,K,M). One figurine head/face was recovered from each site (Figures 2F, 3C, 4). The head from Loy was excavated in the plowzone of a test unit. The right ride of the face had been eroded away but the left eye and mouth are indicated by impressed slits while the clay was pinched to form a small protuberance of a nose and chin (Figure 4, top). No other detail is present, but the general shape of the head may indicate a longer hair style with hair expanding to the jawline. The head from Crane was recovered from a surface collection square. Similar to the figurine found at Loy, the eyes and mouth are indicated by impressed slits while a small protuberance of a nose was pinched from the clay (Figure 4, bottom). The Crane head is more rounded than the elongated head from Loy. There is no evidence of hair or other features, and the surface is not smoothed or polished.

Aside from the figurine head, only one figurine from Loy contains much detail beyond the Casper the Ghost representation of the general human body. This fragment was recovered from a pit feature that also contained a dog burial (Cantwell, 1980), though it was from a different fill layer. It lacks a head, although no clear break is visible between the shoulders (Figure 2D). It is broken below the chest which contains two projections that could represent breasts. One figurine from Loy appears to be unbroken yet lacks a head (Figure 2B). There is a small pin-sized hole between the shoulders of this figurine, which may be where a head was attached with a perishable item such as a sliver of wood (Figure 5A). Other objects in the Loy figurine assemblage are small tubular fragments that may represent portions of limbs (Figures 2J,K).

Figure 5. Detail images of figurines from Loy (top left) and Crane. Saturation enhanced on the bottom right to highlight a potential red pigment. Each specimen assigned a sequential letter (A–D) starting top left to bottom right for identification in text.

The largest figurine from Crane (approximately 6 cm) is a figure with legs bent at the knee and slightly offset with the right leg further forward than the left and feet indicated by thin terminations of pinched clay (Figures 3A, 5B–D). The lack of any anatomical detail on the legs above the knee may indicate clothing such as a skirt or loin cloth. Red coloring on the potential clothing may be remnants of paint or pigment (Figure 5B). This figurine is broken at the chest, but based on similar figurines, it can be assumed that the head was up in the same direction as the feet and may have been supported by arms (e.g., Griffin et al., 1970, Figures 84, 86). The backside has a bulge where the buttocks should be and the curve of the back is clearly modeled. Another figurine fragment from Crane looks similar to this figurine but with less detail (Figures 3F, 6, top). Legs are bent at the knee, and there is an indication of feet via small indentations toward the bottom of the legs. The legs were not formed individually but indicated by an incised line along the front and back. The back line extends to a point that could be representative of buttocks, but there is no corresponding detail on the front legs much above the knee. The back is also entirely flat with no protrusion of the buttocks or curve of the back (Figure 6, top). Several other lower body fragments from Crane give the indication of legs, buttocks, or the pubic triangle with impressed or incised lines (Figures 3B,E,G,H). For example, the detail on one side is essentially a cross shape produced by two impressed perpendicular lines (Figure 3G). Another figurine fragment appears to have an incised representation of the pubic triangle on one side (Figure 6, bottom). Legs are indicated by a single line down the midpoint, but the overall outline is the rounded, amorphous Ghost style. The opposite side is harder to interpret but may have a line indicating the left and right legs below a triangular protuberance that is broadly reminiscent of the hair or bustle other Middle Woodland figurines (compared Figure 3E with McKern et al., 1945, Plate XXIV). One exceedingly small (<2 cm) figurine mostly consists of a body with the head and feet/legs broken off (Figure 3B). As such, it currently resembles a Casper the Ghost style but may have had individually formed legs/feet prior to breakage.

Figurines have been recovered from numerous other settlements in the lower Illinois Valley, most notably the Smiling Dan site (Stafford, 1985). Twelve figurines, or fragments thereof, were recovered from Smiling Dan (Stafford, 1985, p. 179) with the majority (n = 7) falling into the relatively undetailed Casper the Ghost style (Stafford, 1985, Plate 11.5). Several of the heads from Smiling Dan are reminiscent of the Loy and Crane heads with small slits for eyes and mouths with pinched noses and no indications of hair or ears. More detailed figurines from Smiling Dan include the midsection of a presumably male figure with chest definition, a breechcloth, buttocks, straight arms, and semi flexed legs (Stafford, 1985, Plate 11.3, Figure 11.1). A miniature seated figurine has legs tucked to the chest wrapped up by arms that form a continuous circle with no indications of hands (Stafford, 1985, Figure 11.2, Plate 11.4). Buttocks are indicated by a shallow slit. Eye indentations and a nose projection are present along with a probable topknot of hair on top of the head.

Other examples from Illinois valley settlements include figurine fragments at Pool, which include a head with outlined eyes, a mouth with formed lips and a chin, and molded nose and earplugs, as well as a female torso/waist with a pubic triangle indicated and legs with incised lines in kind of sitting position (McGregor, 1958, p. 60–61, Figures 18 and 32). At the nearby Irving site, a single seemingly male upper torso with shoulders/upper arms that were broken off at the neck and below the chest was recovered (McGregor, 1958, p. 71, Figure 34). Gregory Perino recovered an upper torso with roughly molded folded arms at Snyders (Perino, 2006, p. 78–179). Cole and Deuel (1937, Plate XXXIV) provide photographs of a complete figurine from Whitnah. The outline of the Whitnah figurine conforms to the Casper the Ghost style, but legs are indicated with roughly incised lines along with lumps for buttocks and breasts and basic details of the face. Wray and Mac Neish (1961, Figure 11) recovered the upper portion of a figurine from the “Hopewell house” at Weaver. The figurine has the indications of breasts and some details of the face but no arms. The “Y shaped” fired clay object reported by Schoenbeck (1941, p. 65) from the Clear Lake village certainly has the appearance of an upper torso of a Casper the Ghost style figurine. Multiple surface collections indicate that the Blue Creek site (11PK249) is a probable Middle Woodland habitation from which a figurine was recovered with head and legs missing and nubs for arms with pronounced stomach and breasts (Farnsworth and Atwell, 2015, Figure 2.11).

Staab (1984, p. 169) recovered 10 figurines and figurine fragments from Peisker. “Two of the figurine fragments appear to be hands or paws and three are indeterminate body portions. Two fragments are from rather life like human figures. One includes a right hand on which the thumb and fingers were clearly delineated. The other fragment is a carefully modeled, apparently male torso, with a long plait of hair depicted on the back. The other three figurines are crude, stylized human representation” (Staab, 1984, p. 169). Struever (1968) originally described Peisker as a mortuary camp due to the presence of mounds, but Staab’s subsequent excavations in the submound midden revealed a wider range of “subsistence and maintenance tasks” than expected for a mortuary camp (Staab, 1984, p. 2). Another collection of figurines from the Illinois Valley is the group of nine figurines and two heads from a “Hopewellian village site” in Schuyler Counter that were recovered in association with a plow disturbed human burial (Griffin et al., 1970, p. 82). The Schuyler County figurines have substantial detail representing the face, hair, anatomical features of the body, earspools, clothing, and potentially a headdress (Griffin et al., 1970, Plate 83–85; Koldehoff, 2006, p. 190).

While many detailed figurines have been recovered from habitation sites in the Illinois Valley, none reach the level of detail of the figurines from the Knight Mounds (McKern et al., 1945). Knight is just outside of the Illinois Valley on bluffs overlooking the Mississippi, but it is only a few miles from Snyders (Griffin et al., 1970). The six figurines from Knight are all complete or largely so (e.g., missing a portion of one arm). Five of the six figurines from Knight have highly detailed faces, hands, feet, hairstyles, earspools, clothing, accessories, and accompaniments such as children (n = 2) and an atlatl (n = 1). In addition to the details formed in clay, these figurines were painted in shades of red, white, and black. The one exception to the pattern of highly detailed figurines from Knight is a Casper the Ghost style figurine with no particular details, except on the face with outlined eyes and formed mouth, chin, and nose (Griffin et al., 1970, Plate 79). A figurine recovered from the nearby Ansell-Knight habitation site depicts a head with two detailed hair knots (Deuel, 1952, Plate 94). Two figurines were also recovered in association with burials from the Baehr mound in Brown County, Illinois (Griffin et al., 1970, Plate 80–81). One was recovered from a fiber bag and is well modeled as a complete body but with relatively few details of the hands, feet, and other post-cranial anatomy. Legs and arms are clearly formed but completely attached to the rest of the body. The other Baehr figurine is missing the head and lower portion of the left arm. Legs are separately molded while arms are not but have details of the hands, and the figure is wearing a breech cloth.

Outside of the Illinois Valley, figurines with varying levels of detail have been recovered from settlement sites in the American Bottom (Koldehoff, 2006; Maher, 1989, p. 266–268; Zimmermann et al., 2018, p. 108–110) and further north along the Mississippi River at Putney Landing (Markman, 1988, p. 273, Plate 11.5) and near the Albany Mound group (Farnsworth and Atwell, 2015, p. 96, Figure 4.31) in addition to further south in the Mississippi valley at sites such as Twenhafel (Keller and Carr, 2005, Table 11.1). The largest assemblage of figurines from any particular Middle Woodland site is from Mann in southern Indiana near the confluence of the Wabash and Ohio rivers with figurines largely collected from the habitation areas adjacent to mounds and earthworks (Swartz, 2001b). Much like the overall picture of Middle Woodland figurines, the examples from Mann exhibit a wide range of both types and an in-depth level of detail. Furthermore, the most widely cited examples from Ohio Middle Woodland contexts are the group of highly fragmented figurines from the altar of the Turner mound. While these figurines have less detail than those from Knight and do not appear to have additions such as paint, they are highly detailed and clearly not Ghost style figurines. Small numbers of figurines were recovered from other Ohio mounds or enclosures, such as Marietta and Seip. Fewer settlements have been investigated in Ohio as compared with the Illinois valley but relatively amorphous figurine appendage fragments are reported from the McGraw midden (Prufer, 1965, p. 99–100, Figure 6.1).

Figurines are also found at sites in the southeast such as Garden Creek Mound 2 (Keel, 1976, p. 120–122) and Biltmore Mound (Kimball et al., 2010) in North Carolina, Leake and Mandeville in Georgia (Keith, 2013, p. 150; Kellar et al., 1962), Crystal River, Block–Sterns, Bell, and Buck Mound in Florida (Brose, 1979, p. 147; Lazarus, 1960), Marksville, Crooks, and Dickerson in Louisiana and Mississippi (Toth, 1988, p. 52), sites in Alabama (Walthall John, 1975, p. 125) as well as further to the west at Mellor in central Missouri (Kay and Johnson, 1977, p. 202), and Trowbridge near Kansas City, Kansas (Johnson, 1979, p. 9).

In comparison to some other parts of the world, clay figurines form eastern North America have garnered insufficient scholarly attention. Previous research has been largely descriptive, focusing on identifying the figurines as representations of individuals in relation to categories such as social status or gender (e.g., Swartz, 2001a,b). For example, Griffin et al. (1970) and McKern et al. (1945) presented classic descriptions of the detailed and painted figurines from Knight mound and offered the interpretation that these were representations of the deceased who were buried in the mound due to a correlation between the perceived gender of the figurines and the sex of individuals buried at Knight. Others used figurines as one line of evidence to reconstruct the appearance and dress of Middle Woodland peoples (e.g., Deuel, 1952). More recently, Keller and Carr (2005) examined a large sample of Middle Woodland figurines from three different regions in search of how these figurines were representations of gender roles in relation to participation in domestic and mortuary rituals. Keller and Carr ultimately argue that figurines were primarily produced by women for use largely in domestic rituals, while many figurines also depict women in community leadership roles. Similarly, Koldehoff (2006) reports figurines from the American Bottom largely as a descriptive exercise but with a goal of identifying representations of religious or political leaders through an insignia of rank such as headdresses and shamanic costumes. Other reports have focused on technical descriptions of manufacture and assignments of gender and identification of other decorative features (Swartz, 2001a,b; Greenan and Mangold, 2016).3

All of these studies are based on the empirical analysis of figurines and add to our understanding of what these figurines may be representations of. There are, however, two neglected topics to which I call attention here. One place to expand is examining the emergence of figurines as novel material culture in the long-term historical processes in eastern North America in the way that other archeological scholars have studied the emergence of artistic traditions, including figurines, in deep time (e.g., Robb, 2015; Fowles, 2017). For example, little has since been done to expand this line of reasoning since Griffin et al. (1970, p. 87) argued for local development of the figurine tradition in opposition to diffusionist explanations, in that “representations of humans… had a strong development for the first time in the Eastern United States in Hopewellian art.” In other words, why do figurines emerge when and where they do? Why are figurines made by inhabitants of Poverty Point and then seemingly not again until the Middle Woodland?

Second, there is a paucity of research on the agency and materiality of Middle Woodland figurines and what they do as opposed to what they represent (sensu Bailey, 2005, 2007, 2014; Fowles, 2017; Marcus, 2019, p. 29–30; Robb, 2015). Some authors have touched on this topic by offering suggestions such as Keller and Carr’s (2005, p. 442) argument that figurines in domestic contexts may relate to fertility rituals, or Koldehoff’s (2006, p. 191) reasoning, following Griffin et al. (1970), that these were related to ancestor veneration. However, to paraphrase a great deal of scholarship, objects make people as much as people make objects (e.g., Dyke and Ruth, 2015), and the active role of figurines has been underexplored. Furthermore, the focus on figurines as representations of particular individuals has led to an overemphasis on analysis of detailed figurines at the expense of those with less detail. My own descriptions above are guilty of this. As another example, according to McKern et al. (1945, p. 295), a seven-page report of the figurines from Knight only included one sentence on the less detailed Casper the Ghost style figurine. Certainly, more than just the detailed figurines have utility in our understanding. The multitude of Ghost style figurines may not be representations of much detail, but they surely have some purpose. In the following sections, I elaborate upon these two points to highlight important findings about the timing of the emergence of figurines and the materiality of making and using figurines.

Feinman and Neitzel (2023) have recently outlined a detailed model that disentangles subsistence and settlement to highlight the socioeconomic processes associated with increasing residential permanence, aka settling down. These authors separate subsistence and settlement by demonstrating how sedentary settlements are documented among numerous forager societies, how residential mobility and sedentism are not mutually exclusive categories, and how scholars have identified numerous examples to blur the lines between food producing vs. foraging societies. They also highlight the importance of the social aspects entangled with settled life. In their words (Feinman and Neitzel, 2023, p. 11):

People are both inherently social and selfish and are capable of making decisions but are constrained by cognitive limits on their ability to process information. These cognitive limits must be accommodated if larger, more durable communities are to endure. At the same time, to meet key social and environmental challenges, people must cooperate, often in sustained ways. When due to cooperative advantages past community sizes reached critical demographic thresholds, such accommodations involved the forging of new interpersonal arrangements and social institutions whose forms and combinations varied, depending on how these emergent formations were funded. This endeavor has affirmed that the mobile to sedentary transition was truly a dynamic process that took myriad paths with divergent outcomes.

Settling down provides opportunities for new social affiliations, but when these new affiliations push group size past key thresholds, people must address the concomitant scalar stress in new ways. As community size increases up to or beyond the largest threshold of approximately 200 individuals, one way people adapted was through “the advent of more regularly scheduled, routinized, and larger-scale ritual activities” aimed, among other things, at encouraging cooperation among members of dispersed social networks (Feinman and Neitzel, 2023, p. 5). These social affiliations were also associated with new or reorganized institutions that formed overlapping, heterarchical, affiliative identities. Since people are both social and self-interested agents, these interactions with larger communities encourage people to examine the relationship between the individual and the collective in new ways. Furthermore, communities are social and affiliative groupings of individuals and are not equivalent to particular archeological sites or settlements. Communities are multi scalar, must be continually maintained, and are relational assemblages of people, objects, and places (e.g., Harris, 2014). Thus, residential site size does not always determine community size, as initially argued with the distinction between natural and imagined communities. Communities may be spread over many settlements, as in translocal or multi-sited village communities (Bernbeck, 2008; Wallis and Pluckhahn, 2023), especially as group size reaches key demographic thresholds associated with semi-settled communities.

It is an intriguing correlation that figurines in eastern North America were made independently among the residents of Poverty Point and then again beginning in the Middle Woodland as both are associated with settling down, monumental integrative ritual facilities, and new institutional arrangements. The resident population size at Poverty Point was unprecedented up to that point in the history of eastern North America. The preponderance of material remains from far off places and labor estimates for earthen monument construction that far exceed local populations demonstrate that the community at Poverty Point encompassed thousands of individuals (e.g., Ortmann and Kidder, 2013). In the Middle Woodland period, large-scale integrative facilities such as monumental enclosures and mounds greatly exceed the size and, therefore, the associated cooperative labor investments of monuments from previous temporal periods, signaling concomitant expansion of social networks (Buikstra and Charles, 1999; Abrams, 2009; Miller, 2021). Most Middle Woodland settlements were generally not large, typically consisting of one to several households (e.g., Stafford and Sant, 1985). Settlements tended to be geographically clustered; however, there is much evidence for connections between these smaller settlements (e.g., Struever, 1965, p. 220; Ruby et al., 2005; Fie, 2006). Ruby et al. (2005) outlined how landscapes of settlements and monuments reflect expanded communities that were organized through interconnected and overlapping scales of the residential, local symbolic, regional symbolic, and sustainable communities. These communities are not necessarily bounded distinct entities but ways to partition our thoughts about the social processes at work behind individual’s affiliative decisions. These communities can be traced geographically, as evidenced by the location of spatial clusters of settlements and different types of mounded spaces. In the lower Illinois valley, the size of the burial populations at excavated blufftop mound groups range from 25 to 170 individuals, while the distance between floodplain mound groups corresponds well with what “would have been necessary to accommodate 11 bluff-top mound communities and a sustainable community of 500 persons” (Ruby et al., 2005, p. 136–137). The nested scales of community identified in Illinois and elsewhere are consistent with Feinman and Neitzel’s model for how people respond to scalar stress, expanding social networks cross culturally.

For anthropomorphic figurines to have a meaningful connection to settling down and affiliating with larger communities, they must have played a social role. Teasing this out begins with viewing figurines as art and recognizing how—following Gell’s (1998) anthropological theory of art—“art exerts an agency on people by affecting them in particular ways. It is material culture designed to do relational tasks” (Robb, 2015, p. 636). In other words, Gell’s (1998) analysis of art “places its emphasis on the social relations arising around objects that have been designed to be viewed” (Fowles, 2017, p. 680). The materiality and agency of art are keys in this process. To summarize the “materiality turn” in one phrase, things are “active players in human life rather than simply passive symbols” (Dyke and Ruth, 2015, p. 20). This perspective shifts the line of questioning from what do figurines mean? Or what are they representations of? to what do figurines do? (sensu Robb, 2015, p. 636). The question of what figurines do relates to their agency as active “theatrical” objects that “directly address or make overt demands upon the viewer” via their agentive qualities (Fowles, 2017, p. 683). Additionally, Bailey (2005, p. 166) argues that anthropomorphic figurines were one way that people “negotiated and contested individual and group identities through a corporeal means” (see also Marcus, 2019, p. 29–30). “Definition, redefinition, and, critically, the stimuli to think about one’s relationship to others emerge equally from representations” of the body, often at a subconscious level (Bailey, 2005, p. 166). With this background in mind, the following focuses on the agentive power of figurines as miniature three dimensional representations of the human form (Bailey, 2005, 2007, 2014; see also Elsner, 2020 for a similar approach).

Miniatures are abstract representations that do not include all of the detail of the real thing. Thus, certain details can be highlighted to focus attention while others can be suppressed to encourage the viewer to fill in the blanks (Bailey, 2005; Elsner, 2020, p. 4–5; Marcus, 2019, p. 2). As one example, all of the Middle Woodland figurines that include a head have some representation of eyes even those Casper-the-Ghost style figurines that contain few to no other features. Following Gell (1998, p. 12), one reason to highlight the eyes of a miniature is because “eye-contact prompts self-awareness of how one appears to the other, at which point one sees oneself ‘from the outside’ as if one were, oneself, an object.” Additionally, psychological research indicates that interactions with miniatures can transport the viewer to “another mental place, a place where the most rational elements of our existence (such as a perception of time) may be stretched out of shape or compressed” (Bailey, 2005, p. 36). Furthermore, miniaturization changes the relative scale of the viewer, giving the viewer power, comfort, and a sense of control (Bailey, 2005, p. 33; Elsner, 2020, p. 5–6). Elsner (2020, p. 6) argues that the “small worlds” one enters while interacting with miniatures keep their power in the realm of “what if scenarios,” further perpetuating the sense of control or “handleability.”

Miniatures that occur in three dimensions magnify the above qualities for several reasons (Bailey, 2005, p. 38). Miniature 3-D objects can, and should, be handled at a close distance, inviting other senses such as touch into the fold (Bailey, 2005, p. 38, Bailey, 2014; Elsner, 2020, p. 6). Miniature 3-D objects cannot be viewed in toto at one time. Instead, they must be moved in the hand and played with even. There is more agency involved among both the viewer and object in 3-D miniatures than 2-D ones that have a more simplified viewing angle (Bailey, 2005, p. 39; Elsner, 2020, p. 7). The “viewer as handler” interaction that occurs with 3-D miniatures encourages the handler to enter into the world of the figurine where “representations of past and future (including within the mortuary realm of the dead) [or] kinds of social questioning (that may be both supportive and subversive of normative culture)” can be explored (Elsner, 2020, p. 7).

Miniature 3-D anthropomorphic figurines are both body and object, person, and thing (Bailey, 2005; Marcus, 2019, p. 29–30). Figurines are materialized expressions of cultural norms about the body, but they are created by individuals who have the agency of creative expression. These figurines are the “structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures” of the body and therefore play a major role in habitus (Bourdieu, 2005, p. 72). As such, objects cannot be understood solely as the work of individuals but instead as part of “art production systems” composed of social units that both make the system while simultaneously being enabled by it (Gell, 1998; Robb, 2015, p. 637). From this social perspective, creation, interaction, and/or play with miniature 3-D anthropomorphic figurines encourages people “to play out narratives of the self and the other” (Bailey, 2005, p. 72; see also Elsner, 2020, p. 6). Furthermore, when many people connected through multi scalar communities interact with figurines, these objects become “one of many mechanisms through which communities interwove their shared (and contested) senses of how individuals were related to one another, indeed of who people were (and were not)” (Bailey, 2005, p. 159).

At this point, the correlation between figurines and settling down within larger communities comes into sharper focus. People do not just make figurines, but figurines mold human perceptions of the individual and their relationship with the larger collective as active, agentive, and theatrical objects (Fowles, 2017). The characteristics of figurines outlined in this section are particularly important because, for one, they demonstrate that people who interact with figurines are thinking about the individual and the collective through multi-scalar relationships. Additionally, figurines contain marks of the individual(s) who created them and the community ideals, art production systems, and other social entities in which they were entangled. Interactions with figurines reinforced and reconstructed aspects of identity as individuals examined their own body in relation to that of figurines (Bailey, 2005, p. 159; Fowles, 2017, p. 684–686).

In this study, I explored the correlation between periods of community expansion and the corresponding increased settlement permanence with the materiality of figurines. Increased community size and scalar stress from settling down resulted in new opportunities and obstacles to cooperation when human cognitive networks reached key thresholds. As community size increased past key thresholds, “the actual physical diversity among the living, breathing, flesh, and blood individuals was the greatest risk to community cohesion.” (Bailey, 2005, p. 200). Figurines’ power to encourage people to think through themselves in an increasingly complex social context would have been one materialization of working through issues of the individual, larger communities, and scalar stress. Other more conspicuous practices such as earthen monument construction, feasting, ceremonialism, day-to-day interactions, and emerging institutions were certainly a part of the process (Ruby et al., 2005; Ortmann and Kidder, 2013; Henry and Miller, 2020; Miller, 2021). However, “figurines worked in much subtler and, thus, much more powerful ways, and made people think more deeply (without conscious recognition that they were thinking at all) and absorb the ways in which each person fitted into the larger social group” (Bailey, 2005, p. 201).

However, if figurines have inherent agentive qualities that encourage introspection about the self in relation to others and people have always affiliated with others in communities of varying sizes, why do figurines emerge relatively late in the deep history of eastern North America (and elsewhere for that matter)? Again, there must be a tipping point associated with large affiliative groupings where the agency of figurines is enacted to play a role in mediating emergent scalar stress. Scholars around the world have pointed to a correlation between the emergence of anthropomorphic clay figurine traditions and the rise of the Neolithic (Bailey, 2005; Robb, 2015; Fowles, 2017; Marcus, 2019). However, evidence demonstrates that the core aspects of the Neolithic –large sedentary villages dependent on food production— do not always co-occur as complete packages, especially in eastern North America (i.e., Feinman and Neitzel, 2023). Eastern North America, where anthropomorphic clay figurines first occur at Poverty Point and not again until over 1,000 years later at Middle Woodland sites, provides an opportunity to examine each of these subsistence and settlement factors independently for correlations with the emergence of figurine traditions. The foragers at Poverty Point and coastal foragers in the Middle Woodland do not fit into the category of Neolithic food producers (Figure 1). Moreover, the small, dispersed hamlets characteristic of settlements across much of the region during the Middle Woodland are a far cry from Neolithic villages, suggesting that the emergence of figurines cannot be tied to village life. While many of the Middle Woodland examples are not from large individual settlements, they are associated with evidence for relatively large but dispersed communities and social networks associated with ceremonial monumentality broadly similar to that observed at Poverty Point. In summary, rather than an association with food production or village life, the strongest correlation exists between figurines and the demographic community thresholds associated with settling down. In addition to disentangling subsistence and settlement, Feinman and Neitzel’s (2023) model of the socioeconomic dynamics of settling down also provides specific affiliative thresholds at which scalar stress can be expected as opposed to reference to more vague thresholds, such as the emergence of village societies, agriculture, or the Neolithic utilized in other discussions of early figurines.

In the lower Illinois River Valley, there is evidence for the emergence of geographic territories inhabited by interrelated groups of individual households during the Middle Woodland (Ruby et al., 2005). However, individuals, families, and larger communities were not economically or socially self-sufficient. Hence, the creation, maintenance, and expansion of alliances and other connections and the material evidence occur at mound centers and settlements. However, these larger communities also created new tensions across the micro, meso, and macro scales of the social landscape. Figurines were one materialization of connections through shared practices and attempts at alleviating tensions of individuals and groups.

The examples from the Middle Woodland do not represent a singular, monolithic figurine tradition as there was a wide range of variation in Middle Woodland ceramic figurines across eastern North America. However, considering the incredible plasticity of clay as a medium, the variation is relatively restricted in Middle Woodland figurines and in many early figurine traditions (Bailey, 2005, p. 146). The recognition of similar themes and styles across wide regions must signal shared ideas and practices (e.g., Griffin et al., 1970, p. 87; Keller and Carr, 2005, Table 11.1, 440; McKern et al., 1945, p. 300). Despite claims for their role in exchange (e.g., Struever and Houart, 1972, p. 77), the predominance of evidence suggests that these figurines were non-circulating items for personal use (Griffin et al., 1970, p. 87; Keller and Carr, 2005, p. 440). For example, the paste of figurines from any particular site is always similar to local pottery (Johnson, 1979, p. 91; Keel, 1976, p. 122; Kellar et al., 1962, p. 344, 351; Walthall John, 1975, p. 127; Koldehoff, 2006, p. 188). These broad similarities among extensive local variation in the absence of widespread exchange of figurines suggest the presence of local communities of practice and broader constellations of practice, which signal another way figurines played a role in community formation and maintenance during the Middle Woodland period.

Examining the community aspect of what figurines do provide insights into all figurines, regardless of a variation in detail, artisan skill level, or time invested in manufacture. It is reasonable to contend that figurines which lack detail (e.g., Casper the Ghost style) may have been made by individuals of different ages and/or skill levels than the finely detailed figurines that have garnered the most scholarly attention. For example, childhood development research provides evidence to support the intuitively satisfying assumption that detail and technical execution in anthropomorphic clay figurines increase with age and experience (Brown, 1975, 1984). Admittedly, it is also possible that the level of detail could be attributed to factors related to lack of time investment by a skilled artisan. However, the inclusion of a Casper-the-Ghost figurine among the detailed and painted figurines in Knight suggests that the former was made by an artist with less skill (Griffin et al., 1970). If less detailed figurines were made by novices, the preponderance of undetailed figurines across a wide range of sites is evidence that many individuals, not just specialized artisans, were engaging with miniature 3-D anthropomorphic figurines. That said, many figurines from Middle Woodland mounds or burial contexts (e.g., Knight, Schuyler County, and Turner but not Baehr) demonstrate a comparatively high level of execution and detail, perhaps suggesting a connection with ritual craft specialists (Spielmann, 1998). The wide range of detail, or lack thereof, in figurines from settlements (e.g., Crane, Loy, Smiling Dan, Mann) is what would be expected if individuals of many different skill levels were producing figurines at these sites. This conclusion is not surprising when viewing figurines as agents for stimulating thought about the self and social relationships. This interpretation also assigns agency to people of different skill levels by recognizing what figurines do for children or novices. It also allows scholars to extract information from all figurines, even those that are not obvious representations of particular physical features.

The wide diversity of figurines from ancient eastern North America most certainly had a multiplicity of meanings and uses (Bailey, 2005, p. 84). Perhaps some were representations of political leaders, ancestors, or deities, whereas perhaps figurines deposited in mounds were involved in institutional rituals, but the recovery of figurines in domestic refuse could also logically be interpreted as evidence for their use as toys (Zimmermann et al., 2018, p. 108) as there is no independent evidence of ritual activity such as caching or arranging in elaborately staged scenes at settlements (see Bailey, 2005, p. 26–27; Kamp, 2001, p. 236; Marcus, 2019, p. 21). Most importantly, “each of these anecdotal equivalences is not an interpretation; each is merely a suggestion that fails to engage the real essences of figurines as active visual culture” (Bailey, 2005, p. 84). In this vein, there is abundant evidence to show the social agency of figurines was enacted independently in divergent pathways to settled life. Figurines emerged during times when communities were expanding to key demographic thresholds and were likely key components in making communities. The correlation between periods of semi-settled life, larger communities, widespread ceremonial practices, monumental architecture, and the emergence of miniature 3-D anthropomorphic clay figurines in eastern North America speaks to the importance of the latter in the navigation of new affiliative decisions.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: Illinois State Museum.

GLM: Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author thanks Gary Feinman and Victor Thompson for the opportunity to contribute to this research collection and Ken Farnsworth for providing essential background on Loy and Crane as well as for always sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of the Middle Woodland in the Illinois valley. The Illinois State Museum provided access to the Loy and Crane site collections and field records. Two reviewers provided feedback to improve the content and clarity of the manuscript.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The earliest human figurines in eastern North America (the region from the Mississippi River Valley to the Atlantic) have been recovered from Poverty Point (Connolly, 2008, p. 103). The monumental earthen mounds and embankments at Poverty Point were a center for settlement, pilgrimage, and ceremony circa 3,700–3,100 years ago (Gibson, 2001; Connolly, 2008). While the mounds of Poverty Point are not the oldest earthen monuments in eastern North America, there is nothing from this period that approaches their size, scale, and concentration. In fact, Mound A at Poverty Point is the second largest ancient earthen construction in North America and would not be surpassed in size until the construction of Monks Mound at Cahokia over 4,000 years later (Ortmann and Kidder, 2013). While the number of inhabitants at Poverty Point likely swelled during large gatherings, there was a sizeable permanent resident population at the site. Most figurines were recovered from the ridges, which are hypothesized to be habitation areas of the site. Despite early claims of uniformity (Ford and Webb, 1956, p. 49–50), the figurines from Poverty Point “exhibit considerable variation with many unique or rare styles and forms including belts, necklaces, folded arms, and clothing” (Connolly, 2008, p. 103). Some of the figurines have pronounced stomachs and what appear to be breasts, leading to the interpretation that these represent pregnant women. However, many other figurines are highly ambiguous when it comes to representing anything other than a general human form (Gibson, 2001, p. 151–153). The Poverty Point example is anomalous in comparison to the Middle Woodland tradition as figurines seem to be restricted to the Poverty Point site and have not been recovered from other Poverty Point Culture sites. The Poverty Point figurine tradition comes to an end with the cessation of occupation at Poverty Point and associated sites around 3,000 years ago (Kidder et al., 2018). Over the next several centuries, there appears to be a widespread population reduction across large swaths of eastern North America coincident with larger climactic changes (Kidder, 2006).

2. ^Other media that include human images are stone figurines and pipes, fossil ivory, copper and mica cutouts, chipped chert lamellar blades, carved human bone, and clay funerary masks (Cook and Farnsworth, 1981; Keller and Carr, 2005, p. 460; Markman, 1988, p. 284; Swartz, 2001a). One further point of clarification involves human representations in Adena contexts such as some stone tablets and the Adena Man pipe. While traditional culture historical schemes placed Adena squarely in the Early Woodland period in an ancestor–descendant relationship with Middle Woodland/Hopewell, radiocarbon dates reveal substantial temporal overlap (Lepper et al., 2014; Henry and Miller, 2020; Henry et al., 2020, 2021). For example, the Adena Mound, from which the Adena Man pipe was recovered, dates to the first century AD concurrent with the construction and use of some of the large geometric Hopewell enclosures in the region (Lepper et al., 2014, Figure 6). Most Adena tablets were recovered from undocumented or undated contexts but the Wright Mound tablet dates back to approximately 200 AD (Henry and Barrier, 2016, Table 1; Rafferty, 2005, p. 168) and is the sole dated tablet depicting a human form. Thus, in spite of some taxonomic ambiguity, all depictions of the human form date to the Middle Woodland period.

3. ^A similar focus on interpreting figurines as representations of individuals has characterized figurine studies at Poverty Point (See overview in Connolly, 2008, p. 103–105).

Abrams, E. M. (2009). Hopewell archaeology: a view from the northern woodlands. J. Archaeol. Res. 17, 169–204. doi: 10.1007/s10814-008-9028-0

Asch, D. L., and Asch, N. B. (1985). “Archaeobotany” in Massey and Archie. eds. K. Farnsworth and A. Koski (Kampsville: Center for American Archaeology), 162–220.

Asch, D. L., Farnsworth, K. B., and Asch, N. B. (1979). “Middle woodland subsistence and settlement in west Central Illinois” in Hopewell archaeology. eds. D. Brose and N. Greber (Kent: Kent State University Press), 80–85.

Bailey, D. (2005). Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and corporeality in the Neolithic. New York: Routledge.

Bailey, D. (2007). “The anti-rhetorical power of representational absence: incomplete Figurines from the Balkan Neolithic” in Image and imagination: A global prehistory of figurative representation. eds. C. Renfrew and I. Morley (Cambridge: McDonald Institute of Archeological Research, University of Cambridge), 117–126.

Bailey, D. (2014). “Touch and the Cheirotic apprehension of prehistoric Figurines” in Sculpture and touch. ed. P. Dent (Furnham: Ashgate), 27–43.

Bernbeck, R. (2008). “An archaeology of multi-sited communities” in The archaeology of mobility: Old World and New World nomadism. eds. H. Barnard and W. Wendrich (Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology UCLA), 43–77.

Bourdieu, P.. (2005). Outline of a theory of practice. Translated by

Brose, D. S. (1979). “An interpretation of Hopewellian traits in Florida” in Hopewell archaeology. eds. D. Brose and N. Greber (Kent: Kent State University Press), 141–149.

Brown, E. V. (1975). Developmental characteristics of clay figures made by children from age three through age eleven. Stud. Art Educ. 16, 45–53. doi: 10.2307/1320125

Brown, E. V. (1984). Developmental characteristics of clay figures made by children: 1970 to 1981. Stud. Art Educ. 26, 56–60. doi: 10.2307/1320801

Buikstra, J. E., and Charles, D. K. (1999). “Centering the ancestors: cemeteries, mounds, and sacred landscapes of the ancient north American midcontinent” in Archaeologies of landscape. eds. W. Ashmore and A. Bernard Knapp (Malden: Blackwell), 201–228.

Cantwell, A.-M. (1980). Middle woodland dog ceremonialism in Illinois. Wisconsin Archaeolt 61, 480–496.

Carr, C. (1982). Handbook on soil resistivity surveying. Center for American Archaeology Press, Kampsville.

Carr, C. (2022). Being Scioto Hopewell: Ritual Drama and personhood in cross-cultural perspective. Springer Nature, Boston.

Charles, D. K. (2012). “Origins of the Hopewell phenomenon” in The Oxford handbook of north American archaeology. ed. T. Pauketat (New York: Oxford University Press), 471–482.

Charles, D. K., and Buikstra, J. (2006). Recreating Hopewell: New perspectives on middle woodland in eastern North America, University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Cole, F. C., and Deuel, T.. (1937). Rediscovering Illinois: Archaeological explorations in and around Fulton County. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Connolly, R. P. (2008). Scratching the surface: the role of surface collections in solving the “mystery” of poverty point. Louisiana Archaeol 35, 79–115.

Cook, D. C., and Farnsworth, K. B. (1981). Clay funerary masks in Illinois Hopewell. Midcont. J. Archaeol. 6, 3–15.

Deuel, T. (1952). “Hopewellian dress in Illinois” in Archaeology of eastern United States. ed. J. B. Griffin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 165–175.

Dyke, V., and Ruth, M. (2015). Materiality in practice: an introduction. In Practicing materiality, edited by R. DykeVan, pp. 3–32. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Elsner, J. (2020). “Introduction” in Figurines: Figuration and the sense of scale (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–10.

Farnsworth, K. B., and Atwell, K. A. (2015). Excavations at the Blue Island and Naples-Russell mounds and related Hopewellian sites in the lower Illinois Valley ; Urbana-Champaign: Illinois State Archaeological Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Feinman, G. M., and Neitzel, J. E. (2023). The social dynamics of settling down. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 69:101468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101468

Fie, S. M. (2006). “Visiting in the interaction sphere: ceramic exchange and interaction in the lower Illinois Valley” in Recreating Hopewell. eds. D. Charles and J. Buikstra (Tallahasee: University of Florida Press), 427–445.

Ford, J. A., and Webb, C. H.. (1956). Poverty point, a late archaic site in Louisiana. In: Anthropological papers of the American Museum of Natural History 46(1) New York.

Fowles, S. (2017). Absorption, theatricality and the image in deep time. Camb. Archaeol. J. 27, 679–689. doi: 10.1017/S0959774317000701

Gibson, J. L. (2001). The ancient mounds of poverty point: Place of rings. University Press of Florida, Tuscaloosa.

Greenan, M., and Mangold, W. L. (2016). Evidence for figurine manufacturing techniques employed by Mann site artists. Indiana Archaeol 11, 9–25.

Griffin, J. B., Flanders, R. E., and Titterington, P. F. (1970). The burial complexes of the knight and Norton mounds in Illinois and Michigan. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, Ann Arbor.

Harris, O. J. T. (2014). (re) assembling communities. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 21, 76–97. doi: 10.1007/s10816-012-9138-3

Henry, E. R., and Barrier, C. R. (2016). The organization of dissonance in Adena-Hopewell societies of eastern North America. World Archaeology, 48:87–109.

Henry, E. R., Mickelson, A. M., and Mickelson, M. E. (2020). Documenting ceremonial situations and institutional change at Middle Woodland geometric enclosures in central Kentucky. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 45:203–225.

Henry, E. R., and Miller, G. L. (2020). Toward a situational approach to understanding middle woodland societies in the north American midcontinent. Midcont. J. Archaeol. 45, 187–202. doi: 10.2307/26989076

Henry, E. R., Mueller, N. G., and Jones, M. B. (2021). Ritual dispositions, enclosures, and the passing of time: a biographical perspective on the Winchester farm earthwork in Central Kentucky, USA. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 62:101294. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101294

Herrmann, J. T., King, J. L., and Buikstra, J. E. (2014). Mapping the internal structure of Hopewell tumuli in the lower Illinois River valley through archaeological geophysics. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2, 164–179. doi: 10.7183/2326-3768.2.3.164

Johnson, A. E. (1979). “Kansas City Hopewell” in Hopewell archaeology: The Chillicothe conference. eds. D. Brose and N. Greber (Kent: Kent State University Press), 86–93.

Kamp, K. A. (2001). Prehistoric children working and playing: a southwestern Case study in learning ceramics. J. Anthropol. Res. 57, 427–450. doi: 10.1086/jar.57.4.3631354

Kay, M., and Johnson, A. E. (1977). Havana tradition chronology of Central Missouri. Midcont. J. Archaeol. 2, 195–217.

Keith, S. (2013). “The woodland period cultural landscape of the Leake site complex” in Early and middle woodland landscapes of the southeast. eds. A. P. Wright and E. R. Henry (Gainesville: University Press of Florida), 138–152.

Kellar, J. H., Kelly, A. R., and McMichael, E. V. (1962). The Mandeville site in Southwest Georgia. Am. Antiq. 27, 336–355. doi: 10.2307/277800

Keller, C., and Carr, C. (2005). “Gender, role, prestige, and ritual interaction across the Ohio, Mann, and Havana Hopewellian regions, as evidenced by ceramic Figurines” in Gathering Hopewell: Society, ritual, and ritual interaction. eds. C. Carr and D. Troy Case (Boston: Springer), 428–460.

Kidder, T. R. (2006). Climate change and the archaic to woodland transition (3000–2500 Cal BP) in the Mississippi River basin. Am. Antiq. 71, 195–231. doi: 10.2307/40035903

Kidder, T. R., Henry, E. R., and Arco, L. J. (2018). Rapid climate change-induced collapse of hunter-gatherer societies in the lower Mississippi River valley between ca. 3300 and 2780 cal yr BP. Sci. China Earth Sci. 61, 178–189. doi: 10.1007/s11430-017-9128-8

Kimball, L. R., Whyte, T. R., and Crites, G. D. (2010). The Biltmore mound and Hopewellian mound use in the southern Appalachians. Southeast. Archaeol. 29, 44–58. doi: 10.1179/sea.2010.29.1.004

King, J. L., Buikstra, J. E., and Charles, D. K. (2011). Time and archaeological traditions in the lower Illinois Valley. Am. Antiq. 76, 500–528. doi: 10.7183/0002-7316.76.3.500

Koldehoff, B. (2006). Hopewellian figurines from the southern American Bottom. Illinois Archaeology 18:185–193

Lazarus, W. C. (1960). Human Figurines from the coast of Northwest Florida. Florida Anthropol 8, 61–70.

Lepper, B. T., Leone, K. L., Jakes, K. A., Pansing, L. L., and Pickard, W. H. (2014). Radiocarbon dates on textile and bark samples from the central grave of the Adena mound (33RO1), Chillicothe, Ohio. Midcont. J. Archaeol. 39, 201–221. doi: 10.1179/2327427113Y.0000000008

Maher, T. O. (1989). “The middle woodland ceramic assemblage. In the holding site” in American bottom archaeology, FAI-270 site reports. eds. A. Fortier, T. Maher, J. A. Williams, M. C. Meinkoth, K. E. Parker, and L. S. Kelly, vol. 19 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 125–318.

Markman, C. (1988). “Hopewell interaction sphere artifacts” in Putney landing: Archaeological investigations at a Havana Hopewell settlement on the Mississippi River west-Central Illinois. ed. C. Markman (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Department of Anthropology), 270–290.

McGregor, J. C. (1958). The Pool and Irving villages: A study of Hopewell occupation in the Illinois River valley. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

McKern, W. C., Titterington, P. F., and Griffin, J. B. (1945). Painted pottery Figurines from Illinois. Am. Antiq. 10, 295–302. doi: 10.2307/275132

Miller, G. L. (2021). Ritual, labor mobilization, and monumental construction in small-scale societies: the Case of Adena and Hopewell in the middle Ohio River valley. Curr. Anthropol. 62, 164–197. doi: 10.1086/713764

Miller, G. L., and Farnsworth, K. B. (2023). Crane and Loy: middle woodland settlements on Macoupin Creek, Greene County, Illinois. In: Paper presented at the Midwest archaeological conference, Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Mueller, N. G., Spengler III, R. N., Glenn, A., and Lama, K. (2020). Bison, anthropogenic fire, and the origins of agriculture in eastern North America. Anthropocene Rev 8, 141–158. doi: 10.1177/2053019620961119

Ortmann, A. L., and Kidder, T. R. (2013). Building mound a at poverty point, Louisiana: monumental public architecture, ritual practice, and implications for hunter-gatherer complexity. Geoarchaeology 28, 66–86. doi: 10.1002/gea.21430

Perino, G. (2006). The 1955 Snyders Village site excavations, Calhoun County, Illinois. In Illinois Hopewell and late woodland mounds, by

Prufer, O. H. (1965). “Miscellaneous artifacts” in The McGraw site: A study in Hopewellian dynamics. ed. O. H. Prufer (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Natural History), 98–103.

Rafferty, S. (2005). “The Many Messages of Death: Mortuary Practices in the Ohio Valley and Northeast,” in Woodland Period Systematics in the Middle Oiho Valley, edited by D. Applegate and R. C. Mainfort Jr., 150–67. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Robb, J. (2015). Prehistoric art in Europe: a deep-time social history. Am. Antiq. 80, 635–654. doi: 10.7183/0002-7316.80.4.635

Ruby, B. J., Carr, C., and Charles, D. K. (2005). “Community organizations in the Scioto, Mann, and Havana Hopewellian regions: a comparative perspective” in Gathering Hopewell: Society, ritual, and ritual interaction. eds. C. Carr and D. Troy Case (Boston: Springer), 119–176.

Schoenbeck, E. (1941). Cultural objects of clear Lake Village site. Trans Illinois State Acad Sci 34:65.

Seeman, M. F. (2004). “Hopewell art in Hopewell places” in Hero, hawk, and open hand: American Indian art of the ancient Midwest and south. ed. R. F. Townsend (New Haven: Yale University Press), 57–71.

Seeman, M. F. (2020). “Twenty-first century Hopewell” in Encountering Hopewell in the twenty-first century, Ohio and beyond. eds. B. G. Redmond, B. J. Ruby, and J. Burks, vol. 2 (Akron: University of Akron Press), 313–342.

Smith, B. D. (1992). “Hopewellian farmers of eastern North America” in Rivers of change. ed. B. Smith (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press), 201–248.

Spielmann, K. A. (1998). Ritual craft specialists in middle range societies. Archeol Papers Am Anthropol Assoc 8, 153–159. doi: 10.1525/ap3a.1998.8.1.153

Staab, M. L. (1984). Peisker: An examination of middle woodland site function in the lower Illinois Valley. PhD Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, The University of Iowa.

Stafford, B. D. (1985). “Overview of material remains” in Smiling Dan: Structure and function at a middle woodland settlement in the Illinois Valley. eds. B. Stafford and M. Sant (Kampsville: Center for American Archaeology), 166–182.

Stafford, B. D., and Sant, M. B. (1985). Smiling Dan: Structure and function at a middle woodland settlement in the Illinois Valley. Center for American Archaeology Research: Kampsville.

Struever, S. (1965). Middle woodland culture history in the Great Lakes riverine area. Am. Antiq. 31, 211–223. doi: 10.2307/2693986

Struever, S. (1968). “Woodland subsistence-settlement Systems in the Lower Illinois Valley” in Archeology in cultural systems. ed. L. R. Binford, Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co. 285–312.

Struever, S., and Houart, G. L. (1972). “An analysis of the Hopewell interaction sphere” in Social exchange and interaction. ed. E. Wilmsen (Ann Arbor: Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan), 47–147.

Swartz, B. K. (2001a). “A survey of Adena-Hopewell (Scioto) anthropomorphic portraiture” in The New World figurine project. eds. T. Stocker and C. L. Otis, vol. 2 (Provo: Research Press, Brigham Young University), 225–252.

Swartz, B. K. (2001b). “Middle woodland Figurines from the Mann site, Southwest Indiana” in The New World figurine project. eds. T. Stocker and C. L. Otis, vol. 2 (Provo: Research Press, Brigham Young University), 253–270.

Toth, E. A. (1988). Early Marksville phases in the lower Mississippi Valley: A study of culture contact dynamics. Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson.

Wallis, N. J., and Pluckhahn, T. J. (2023). Understanding multi-sited early village communities of the American southeast through categorical identities and relational connections. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 71:101527. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2023.101527

Walthall John, A. (1975). Ceramic Figurines, Porter Hopewell, and Middle Woodland Interaction. Florida Anthropol 28, 125–140.

Weiland, A. W., Crawford, L. J., Ruby, B. J., and Purtill, M. P. (2023). Feasting at a world center shrine: Paleoethnobotanical and micromorphological investigations of a Woodhenge earth oven. J. Archaeol. Method Theory. doi: 10.1007/s10816-023-09620-x

Wray, D., and Mac Neish, R. S. (1961). The Hopewellian and weaver occupations of the weaver site, Fulton County, Illinois. Springfield: Illinois State Museum, Springfield.

Wright, A. P. (2020). Garden Creek; the archaeology of interaction in middle woodland Appalachia. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Wright, A. P., and Henry, E. R. (2013). Early and middle woodland landscapes of the southeast. University Press of Florida, Tallahassee.

Keywords: figurines, middle woodland, Hopewell, socioeconomic dynamics, materiality

Citation: Miller GL (2024) Settling down with anthropomorphic clay figurines in eastern North America. Front. Hum. Dyn. 6:1355421. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2024.1355421

Received: 13 December 2023; Accepted: 01 February 2024;

Published: 21 February 2024.

Edited by:

Victor D. Thompson, University of Georgia, United StatesReviewed by:

Neill Wallis, University of Florida, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Miller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: G. Logan Miller, glmill1@illinoisstate.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.