- Department of Anthropology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, United States

During the Middle Preclassic period (c. 1000–350 BCE), the people of the Maya lowlands transitioned from a mobile horticulturalist to sedentary farming lifestyle, exemplified by permanent houses arranged around patios and rebuilt over generations. Early evidence of this change has been found in northern Belize, in the Belize Valley, and at Ceibal, Guatemala. At Cuello and other sites in northern Belize, mortuary rituals tied to ancestor veneration created inequality from the beginning of sedentary life. There, relatively dense populations facilitated the emergence of competitive sociopolitical strategies. However, Maya communities in different regions adopted different aspects of sedentism at different times and employed different power strategies. Unlike Cuello, Ceibal was founded as a ceremonial center by semi-mobile people. Middle Preclassic ritual practices at Ceibal and in the Belize Valley were associated with more collective leadership. At the end of this period, increased population densities contributed to a shift to more exclusionary rituals and political strategies throughout the lowlands.

Introduction

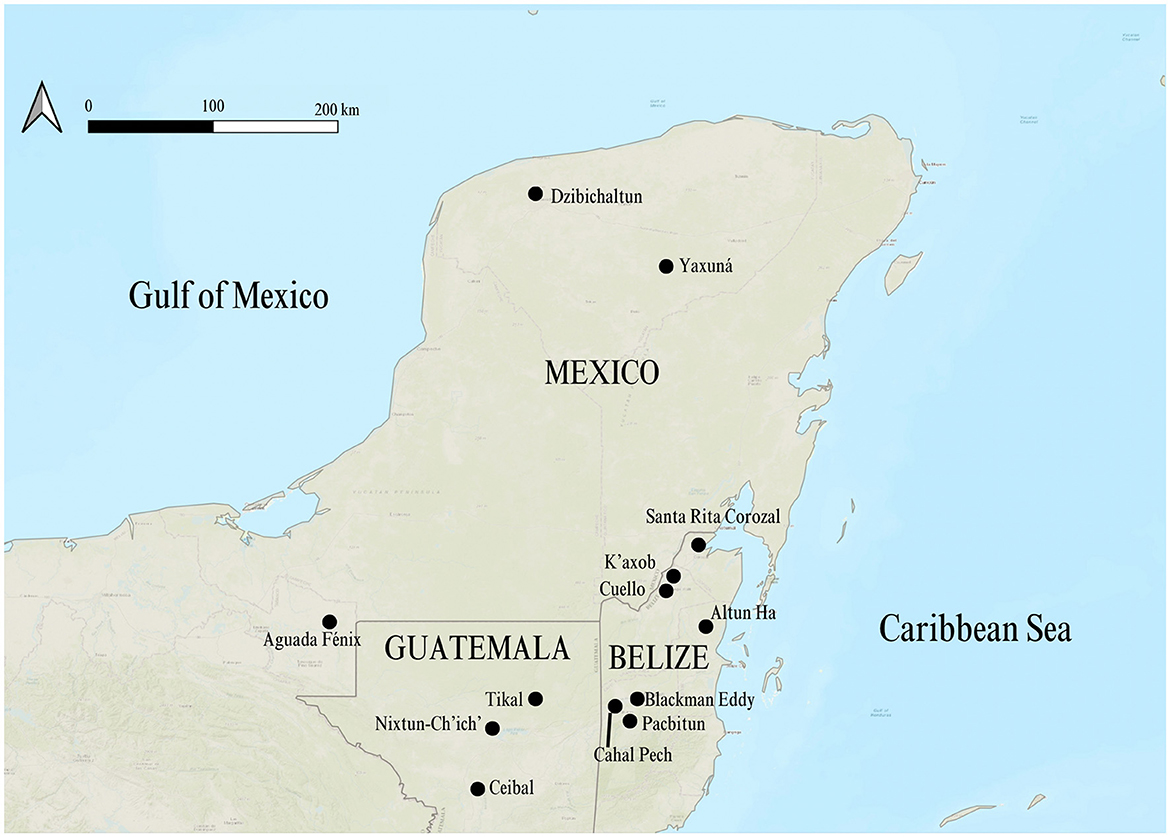

Compared to other parts of Mesoamerica, the transition from a mobile horticulturalist lifestyle to a sedentary agriculturalist lifestyle occurred relatively late in the Maya area. While the lowland Maya had been cultivating domesticated maize and other plants for centuries, they maintained a mobile, pottery-free, Archaic-style lifestyle until c. 1000 BCE (Lohse, 2010) – possibly as early as 1200 BCE in a few locations (Sullivan et al., 2018; Inomata et al., 2020). Around 1000 BCE, much of Mesoamerica became dependent on maize agriculture, thanks to the intensification of agricultural practices, the spread of more productive maize plants, or both (Rosenswig et al., 2015). The new reliance on agriculture was part of the gradual, heterogenous process through which the Maya settled down. During the Middle Preclassic period (c. 1000–350 BCE), the Maya began to build permanent dwellings around open patios that were occupied and remodeled over generations. Archaeologically, we identify the earliest permanent Maya sites based on the presence of early (pre-Mamom phase) Maya ceramics (Inomata, 2017a; Andrews et al., 2018; Sullivan et al., 2018; Walker, 2023) and their locations below later Maya architecture. Clear evidence of the transition to sedentary life, including ceramics, architecture, and radiocarbon dates, has been found in Yucatan; northern Belize; the Belize Valley region; Aguada Fénix, in Tabasco; and Ceibal, in Guatemala (Figure 1).

The people who settled the Maya lowlands were in contact with complex Mesoamerican societies, such as the Gulf Coast Olmec, that had long been sedentary and included centralized rulership (Rosenswig, 2010). Although the early Maya participated in some of the same practices as those societies, including building monumental ceremonial centers and depositing caches of greenstone objects (Clark and Hansen, 2001; Inomata et al., 2013, 2021), the earliest clear evidence of Maya rulers dates to around 100 BCE (Coe, 1965; Saturno, 2009; Inomata et al., 2014). As others have argued, it is important to examine Middle Preclassic social complexity on its own terms, rather than as a prelude to the city-states and divine kings of the Classic period (Canuto, 2016; Pugh, 2021). Complexity is not the same as hierarchy (Crumley, 1987, 1995, 2003), and Middle Preclassic society was made up many different but overlapping communities without being strongly hierarchical (MacLellan and Castillo, 2022).

Rather than simply stating that the Preclassic Maya were less hierarchical than the Olmec, it is useful to consider how power relationships were created among Preclassic Maya people. Blanton et al. (1996) identified two political strategies in ancient Mesoamerica: exclusionary/network and corporate/collective/cooperative. During the Formative Period, the Gulf Coast Olmec exhibited the “network” strategy, through which competitive individuals gained elite status based on long-distance connections and control of prestige goods. This strategy is evidenced by portraits of individual rulers and a widespread, “international” style of art. In contrast, Early Classic Teotihuacan shows evidence of the “corporate” strategy, in which power was more spread out through society, the population willingly collaborated on public works, and individual leaders were not memorialized. Teotihuacan invested in public spaces and apartment complexes, rather than palaces, and the artwork of Teotihuacan is focused on mythology and nature, rather than a ruling elite. These are simplified examples, and exclusionary and collective strategies can exist in the same society, just as hierarchical and non-hierarchical sociopolitical relationships coexist in every society (Crumley, 1995). The balance of exclusionary vs. collective strategies and hierarchical vs. non-hierarchical relationships within a society can also change over time.

Blanton and others continue to investigate cooperation and collective action in Mesoamerican societies, especially in Central Mexico (Blanton and Fargher, 2008; Carballo, 2013; Carballo et al., 2014; Blanton, 2016; DeMarrais and Earle, 2017). These scholars point out that cooperation, in which individual agents sacrifice power or incur risks for the sake of the group, is not a matter of being duped by elites, but is instead an often-rewarding strategy. Using a collective action framework, Feinman and Carballo (2018, p. 11) place “much of the Maya Preclassic” on the “more collective” (more collaborative, less competitive) end of a spectrum for Mesoamerican urban societies, presumably based on low socioeconomic differentiation, lack of identifiable rulers, and investment in communal architecture over palaces and other exclusive spaces. In a review of recent studies of Middle Preclassic complexity, Pugh similarly argues that the early Maya used cooperative strategies and collective organization to build monumental public works at Nixtun-Ch'ich' and Aguada Fénix (Inomata et al., 2020; Pugh, 2021).

Evidence for economic stratification among the early Maya is sparse. Certain Middle Preclassic households likely had a higher status, based on the elevation of their dwellings on monumental platforms, constructed with the labor of a larger community (Awe, 1992, p. 112–137; Triadan et al., 2017). However, as at the Early Formative site of Paso de la Amada in the Pacific Coast region, this elevation does not necessarily equate with material wealth (Lesure and Blake, 2002). All Middle Preclassic households seem to have had fairly equal access to goods (King, 2016). Diets varied greatly across regions, but trended toward greater maize consumption over time (King, 2016, p. 432–434; Pugh, 2021, p. 552–553). Individual households produced their own food and many crafts, including obsidian tools and shell ornaments (Aoyama et al., 2017; Hohmann et al., 2018; Sharpe and Aoyama, 2023). Long-distance trade of exotic materials like obsidian, greenstone, and marine shell must have been controlled, or at least organized, by specialists (Aoyama, 2017; Sharpe, 2019). For example, Aoyama et al. (2017, p. 411) observe that Middle Preclassic Ceibal probably distributed obsidian to the smaller sites in its periphery. Hohmann et al. (2018, p. 139) argue that a Middle Preclassic marine shell workshop in a residential context at Pacbitun, in the Belize Valley, represents craft specialists engaged in ornament production for exchange. The control of long-distance trade and prestige goods is one way that Preclassic Maya leaders engaged in “less collective” or “exclusionary” power strategies (Blanton et al., 1996; Feinman and Carballo, 2018, p. 11). Nevertheless, obsidian and marine shell artifacts were widespread and accessible across the lowlands.

Perhaps due to the paucity of observable differences in economic status, many archaeologists focus on rituals, including mortuary practices, when discussing early Maya social complexity. Ritual plays a key role in the development of social complexity, because it brings people together while simultaneously facilitating differentiation (Turner, 1969, 1974; Hill and Clark, 2001). Access to certain materials, spaces, and knowledge is limited to specialists, who have particular obligations. Those specialists may or may not gain higher status, but sociopolitical relationships are created through their activities (Bell, 1992, p. 197). These relationships result in communities with shared interests and ideologies (Bell, 1992, p. 125; Yaeger and Canuto, 2000, p. 5–9). For the Preclassic and Classic Maya, gatherings for ritual performances in public plazas were key to the creation of such communities (Inomata, 2006; Estrada-Belli, 2011; Inomata and Tsukamoto, 2014; Inomata et al., 2015a; Brown et al., 2018).

Mortuary rituals have long been used by archaeologists as a proxy for inequality (Saxe, 1970; Binford, 1971; Parker Pearson, 1999, p. 72–94), based on the assumption that the way people are treated after death reflects their lived positions in their communities. This assumption can be misleading, as many factors influence burial practices (Parker Pearson, 1999, p. 83–86; Brück, 2004). Nevertheless, well-documented and securely dated patterns in mortuary practices can convincingly demonstrate social differentiation. According to Blanton et al. (1996), differentiation in burial practices and grave goods is characteristic of less collective, more exclusionary socioeconomic organizations (Feinman and Carballo, 2018, p. 11). Burial locations may relate to inequality, especially after the transition to sedentism, as prominent places in the landscape may become resting places for high-status individuals (Joyce, 2004). Special treatment of select ancestors may also legitimate a group's land rights (Goldstein, 1981; Morris, 1991).

Based on evidence from K'axob, in northern Belize, McAnany argues that the earliest sedentary Maya farmers established heritable land rights by interring their dead within their dwellings, by constructing successive house platforms in the same location over generations, and by curating the bones of selected ancestors for use in rituals (McAnany, 1995). Lineages with claims to the best land gained social and political status over time, and the resting places of their most important ancestors became shrines and temples. Mortuary evidence for this practice includes: (1) placement of burials within houses; (2) individuals prepared in relatively complex positions; (3) multiple individuals in one burial – often several secondary (disarticulated, curated, incomplete) interments surrounding a primary individual; (4) presence of secondary burials, particularly bundles that include long bones, maxillae, and mandibles; and (5) differences in grave goods (McAnany et al., 1999). This ancestor veneration model, which describes an exclusionary political strategy, has been very influential in Maya archaeology.

Here, I review the transition to sedentary life in the Maya lowlands through a comparison of two early Maya sites, Cuello and Ceibal, located in different regions. This comparison is possible thanks to the careful stratigraphic control and detailed publications of the Cuello project. I discuss the construction histories of the earliest residences and the associated domestic rituals, including burials. I argue that a focus on the mortuary records of northern Belize gives an image of the Middle Preclassic period as a time of gradually increasing inequality and competitive political strategies. A wider view shows that more collective strategies were common elsewhere in the Maya lowlands until the end of the Middle Preclassic, when increasing populations may have necessitated exclusionary strategies that led to greater inequality.

Case studies: Cuello and Ceibal

The best known and most complete record of an early Maya village comes from Cuello, which was excavated under the direction of Hammond (1991). For good reasons, data from Cuello and the later village of K'axob (McAnany, 2004), both in northern Belize, have had a major influence on our understanding of the Middle Preclassic (c. 1000–350 BCE) Maya and the origins of sociopolitical complexity in the lowlands. However, great variation existed across the Maya area during this period. The earliest Maya were heterogeneous and spread over different environmental zones. Northern Belize is unusual for its wealth of Archaic period material, indicating a relatively high population density around the transition to sedentary life (Rosenswig, 2021; Valdez et al., 2021). Communities in other regions emerged under different conditions.

Excavations at Ceibal, directed by Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan, provide new insights into the transition to sedentism. Unlike Cuello, which began with small domestic structures, Ceibal was founded by semi-mobile people as a ceremonial center, with a monumental plaza and formal public rituals (Inomata et al., 2013, 2015b). Preclassic household architecture and rituals at Ceibal differ greatly from those documented in northern Belize. By contrasting the archaeological records of two well documented sites, one sees diversity in the social processes out of which lowland Maya society emerged.

Cuello

Cuello is located in the Orange Walk district of Belize, between the Rio Hondo and the New River (Figure 1). Between 1975 and 2002, Hammond directed 11 seasons of fieldwork, focusing on the Preclassic period at Platform 34 (Hammond, 1991, 2005). Through extensive, meticulous excavations and radiocarbon dating, Hammond and colleagues documented a Middle Preclassic residential area founded at the transition to sedentism.

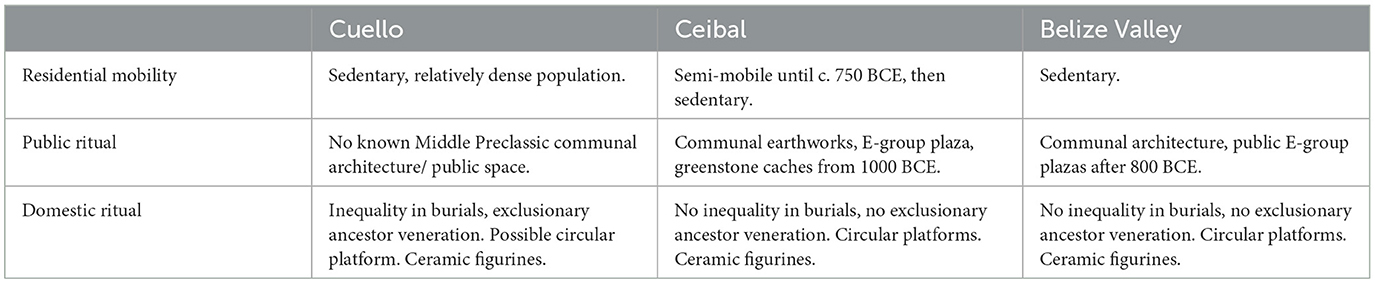

The earliest permanent occupation, corresponding to the Swasey ceramic phase, was originally dated to before 2000 BCE, but Hammond moved the estimate to 1200 BCE based on a reassessment of the radiocarbon results (Kosakowsky, 1987; Hammond, 2005). Meanwhile, Andrews favored a date after 1000 BCE based on more recent radiocarbon dates and stylistic analyses (Andrews and Hammond, 1990). Further consideration of the contexts of carbon samples, comparisons to ceramic collections from other sites and a Bayesian statistical analysis of the dates lead both John Lohse and Takeshi Inomata to argue that sedentary life and ceramic use at Cuello began around 1000 BCE (Lohse, 2010; Inomata, 2017a). The Swasey phase corresponds to the Real 1 phase at Ceibal and Cunil phase in the Belize Valley (Table 1). The beginning date for the Cunil phase is supported by Lohse's review of recent radiocarbon dates (Lohse, 2023). Cuello's Bladen ceramic phase dates to around 800–600 BCE, covering the transition from the Early Middle Preclassic to the Late Middle Preclassic period. The Bladen phase corresponds to Real 2, Real 3, and Escoba 1 at Ceibal and Early Jenney Creek in the Belize Valley.

Table 1. Preclassic ceramic chronologies of Cuello, Ceibal, and Belize Valley, with approximate date ranges (after Inomata, 2017a).

Early Middle Preclassic: Swasey phase

The earliest architecture at Cuello consists of post holes in the natural, sterile soil and bedrock surface, associated with Swasey phase ceramics (Gerhardt, 1988; Hammond et al., 1991b). Soon after, the first house platforms were constructed. These are low, apsidal in shape, and plastered. Post holes show that the platforms supported perishable dwellings. During the second part of the Swasey ceramic phase, house platforms were arranged around the first patio, which was covered by a plaster floor. Similar domestic patio groups were constructed at Blackman Eddy, in the Belize Valley region, as early as 1000 BCE (Brown and Garber, 2005).

Three burials (Burials 62, 159 + 167, and 179 + 180) may date to the Swasey phase, but their chronologies are unclear (Robin, 1989; Hammond et al., 1991b, p. 31, 32, 1992; Hammond, 1999). These burials are not associated with Swasey period constructions and do not contain grave goods. Burials 159+167 and 179+180 were found near Bladen-phase burials and structures, while Burial 62 was found in a depression in the bedrock. Radiocarbon dates from bones of Burials 62 and 179 suggest these individuals died before 1000 BCE, but the contamination of Burial 62 with conservation chemicals made its initial dating uncertain (Hammond et al., 1991a, p. 31, 32). A radiocarbon date measured after removing contaminants gives a calibrated date around 1000 BCE (Law et al., 1991), so Burial 62 may belong to the Swasey phase. Based on the stratigraphy, it is likely that Burials 179+180 and 159+167 belong to the Bladen period, and the radiocarbon date from 179 is unreliable (Inomata, 2017a, p. 334, 335). Alternatively, Lohse argues that all three early burials may actually represent a pre-ceramic, Archaic era population (Lohse, 2010).

Early Middle Preclassic: Bladen phase

The practice of building apsidal, plastered house platforms and perishable superstructures around an open patio continued throughout the Bladen phase (Gerhardt, 1988; Hammond et al., 1991b). House platforms grew taller and more elaborate as they were rebuilt over Swasey phase predecessors and renovated multiple times. The earliest known sweat bath in the Maya lowlands was constructed in the domestic group during this period (Hammond and Bauer, 2001; Hammond et al., 2002; Hammond, 2005).

During Bladen times, the residents began to deposit burials in house platforms. At least 17 burials belong to this phase (Robin, 1989; Hammond et al., 1991a,b, 1992, 1995, 2000; Hammond, 1999). Seven individuals are children. The graves contain many highly varied grave goods, including ceramic vessels, jade beads, two Olmec-style jade pendants (one in the burial of a female adult and the other in the burial of a child), stone tools, shell jewelry, marine shells, one ocarina, and cylinder seals. Adults of both sexes and children received burial offerings. The individuals in Burial 2 and Burial 9 show signs of being de-fleshed before burial, and Burial 2 was disarticulated. Burial 9 was interred in an unusual, seated position and is also the only Bladen burial found in the patio rather than a house platform.

Late Middle Preclassic

At the transition to the Late Middle Preclassic period, or Lopez-Mamom ceramic phase (c. 600–350 BCE), the low domestic platforms around the patio were renovated and rebuilt. During the subsequent construction phase, Structures 315 and 314 became the earliest rectangular platforms in the group (Gerhardt, 1988; Hammond et al., 1991b, 2002; Hammond, 2005). These structures were also the first to support stone superstructures. Structure 315, on the north side of the patio, was only 8 meters long and 5 meters wide, and may have been a ritual rather than residential building (Hammond, 2005).

At least 30 Late Middle Preclassic burials were excavated at Platform 34 (Robin, 1989; Hammond et al., 1991a,b, 1992, 2002; Hammond, 1999). Six additional burials (Burials 173–175 and 182–184) may date to either the Bladen or Lopez phase (Hammond et al., 1995, 2000). All but two of the burials were deposited in house platforms. Hammond (1999) sees social differentiation in the burial offerings from this time period. Ceramic vessels and shell jewelry were common grave goods for adults of both sexes and for children. Jade beads were found only in six burials sexed as male. Cuello Burial 160, of an adult male, contained an unusual wealth of offerings: three ceramic vessels, a perforated snail shell, three shell beads, three jade beads, part of a turtle carapace, four carved bone tubes, and a pendant made from a human skull and decorated with an anthropomorphic face (Hammond et al., 1992; Hammond, 1999). Three of the individuals (Burials 1, 6, and 152) were missing skulls, but it is not clear whether the skulls were removed before or after deposition.

Late Preclassic

The beginning of the Late Preclassic (c. 350 BCE) was a time of drastic change at Cuello (Gerhardt, 1988; Hammond et al., 1991b, p. 41–43). The patio group at Platform 34 was destroyed, leaving evidence of extensive burning. An offering of jade beads was left in the patio at the termination. Mass Burial 1, containing at least 32 individuals, was created during the process of filling in the patio group with rubble. All the interred were adults and most were male. Most were interpreted as sacrificed or dismembered. Cocos-Chicanel ceramic vessels and carved bone tubes were included in the burial. Two decapitated young adults were also buried in the fill layers, and an infant burial was left in a retaining wall. After the domestic group was filled in, Platform 34 became an open, plastered plaza (Gerhardt, 1988; Hammond et al., 1991b, p. 43, 44). Next, Platform 34 was expanded to the north to construct Structure 312. This is a long structure with a front terrace, facing south, into the patio. Several burials are associated with Structure 312. Fire pits and post holes in the floor outside Structure 312 could indicate domestic activities, but the structure itself may not be residential. Structure 312 and its terrace resemble contemporaneous architecture at the Karinel Group, discussed below.

The foundation of Ceibal

Ceibal is a large Maya site on the Pasion River in southwest Peten, Guatemala (Figure 1). The site was investigated by Harvard University's Seibal Archaeological Project, directed by Gordon Willey, from 1964 to 1968 (Willey et al., 1975). The Harvard project documented an Early Middle Preclassic occupation associated with the Real-Xe ceramic phase (Sabloff, 1975). Cache 7, a cruciform pit in the Central Plaza, contained five Real ceramic vessels, six greenstone axes, and a greenstone bloodletter (Smith, 1982, p. 118, 242–245). This cache was compared to cruciform caches and greenstone artifacts from the Olmec center of La Venta.

In 2005, Inomata and Triadan began the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project to explore the Early Middle Preclassic origins of lowland Maya society, building on the work of the Harvard project. Inomata has refined Sabloff's original chronology (Inomata, 2017a; Inomata et al., 2017b). We have learned that Ceibal's earliest plaza was carved out of the bedrock around 950 BCE, and we suggest that lowland Maya society grew out of multidirectional, interregional interactions during the Middle Preclassic period (Inomata et al., 2013; Inomata, 2017a). The plaza and associated platforms make up one of the earliest securely dated “E-group” ceremonial complexes in Mesoamerica (Inomata, 2017b). Early E-groups were aligned with the solar calendar. Beginning at Ceibal's foundation, caches containing greenstone axes were repeatedly deposited along the centerline of the E-group plaza (Inomata and Triadan, 2015; Inomata et al., 2017a). The E-group layout and caches show connections to sites in Chiapas and the Olmec Gulf Coast (Clark and Hansen, 2001; Inomata et al., 2013). These activities were organized by specialists, but the people of Middle Preclassic Ceibal emphasized public architecture and cosmological symbolism over the aggrandizement of individual leaders.

Despite extensive excavations, there is little evidence for domestic architecture at Ceibal during the first part of the Early Middle Preclassic. In contrast with Cuello and Blackman Eddy, the earliest clear house platforms date to the Real 3 phase, c. 750–700 BCE (Table 1). This does not mean there were definitely no permanent dwellings during the Real 1 and 2 phases. For example, it is not clear whether Platform Sulul, a 1.3 m tall structure built near the Central Plaza around 950 BCE, functioned as a residential complex (Inomata et al., 2013; Triadan et al., 2017). At Caobal, a satellite site of Ceibal, post holes in the bedrock represent a perishable structure dated to the Real 2 (c. 850–750 BCE) or Real 3 phase (Munson and Pinzón, 2017). In the core of Ceibal, Structure Fernando, a small platform carved out of the natural marl soil, is probably a Real 3 house platform (Inomata et al., 2015b; Triadan et al., 2017). Later during the Real 3 phase, Structure Fernando was replaced by Platform K'at, which was 1.6 m−1.9 m tall and may have supported a patio group for a high-status household.

It is conceivable that some people did live in permanent dwellings at Ceibal before the Real 3 phase, and we have not recognized them in the archaeological record. However, a substantial population created and used the early public plaza. We argue that a large part of this population continued a more mobile lifestyle – moving seasonally and living in perishable structures – for some time after the plaza foundation, rather than building and renovating permanent dwellings (Inomata et al., 2015a,b). The same pattern is seen at Yaxuná, in Yucatan, where the E-group dates to the Early Middle Preclassic but no contemporary residences have been identified (Stanton et al., 2022, p. 60–66). Archaeological investigations from around the world have shown that similarly mobile, non-hierarchical groups are capable of monumental constructions for communal rituals (Brück, 1999; Marcus and Flannery, 2004; Saunders et al., 2005; Gibson, 2006; Schmidt, 2010; Burger and Rosenswig, 2012; Dietrich et al., 2013; Ortmann and Kidder, 2013). At Ceibal, the transition to sedentism was gradual and piecemeal, and a formal public space preceded the adoption of formal domestic spaces by most of the population.

Early burials at Ceibal

While a few possible Swasey burials and at least 17 Bladen phase burials were excavated at Cuello, only a handful of burials from Ceibal may date to the Real phase. None were encountered by the Harvard project. Burial 110 was deposited at Platform Sulul during the Real 2 or Escoba 1 (700–600 BCE) phase (Triadan et al., 2017, p. 241). The burial contained a juvenile who died at about 11 years old (according to bioarchaeologist Juan Manuel Palomo) and a spouted ceramic vessel. Burial 136, of a female adult (erroneously reported as male elsewhere), was interred near but not inside the Real 3-era E-group (Inomata et al., 2017a, p. 215). The burial contained four complete Real 3 phase ceramic vessels. Real-phase Burial 132 and Burial 160 (not to be confused with Cuello Burial 160) were excavated in the Karinel Group and will be discussed below. Burial 128 may date to the Real 3 or Escoba phase and was also excavated at the Karinel Group.

In recent years, Melissa Burham has overseen the excavation of a cluster of several possibly preceramic burials at the Amoch Group of Ceibal (Burham, 2022, p. 269, 270). At least two of these burials have been radiocarbon dated to about 1000 BCE or earlier. None are associated with artifacts or architecture. These burials raise the possibility of an Archaic, seasonal occupation at Ceibal that contributed to the foundation of the ceremonial center. If Lohse is correct that the earliest burials at Cuello are preceramic (Lohse, 2010), the Amoch group cemetery could be an important comparative sample. The results of Burham's ongoing investigations should clarify the situation. In this paper, I focus on the Middle Preclassic-era processes in the transition to sedentary life.

The Karinel Group

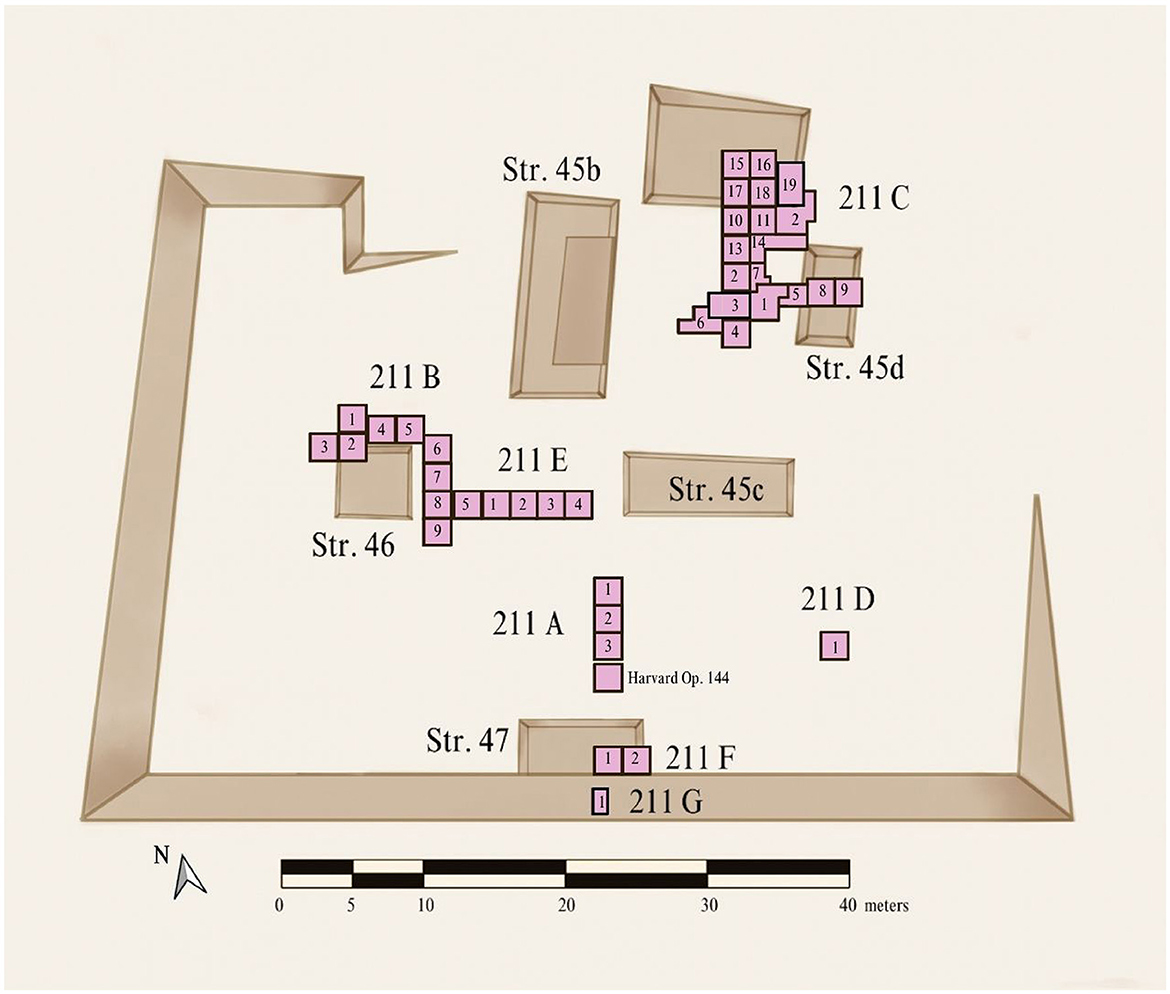

The Karinel Group (Unit 47) is a residential area 160 m west of the Central Plaza (Smith, 1982, p. 4). The group was investigated by Gair Tourtellot during his survey of the periphery (Tourtellot, 1988, p. 171–174). Based on Tourtellot's test pit, the area was occupied during Real times and the bedrock was relatively close to the ground surface, making it a promising location at which to expose large areas of Early Middle Preclassic domestic architecture and deposits. I oversaw four seasons of excavation from 2012 to 2015 (MacLellan, 2019a,b) (Figure 2). The main objective was to understand the role of household ritual practices in the development of sociopolitical complexity (Burham and MacLellan, 2014; MacLellan, 2019c; MacLellan and Castillo, 2022).

Figure 2. Karinel group with excavation units: Suboperations 211A-G and Harvard Op. 144 (after Smith, 1982). Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

Early Middle Preclassic

The earliest ceramics at the Karinel Group are found in deposits on the bedrock (Subops. 211A and 211D) and dated to the Real 2 phase (c. 850–750 BCE). One alignment of small stones and one possible post hole in the bedrock, near the southern edge of the group, may also date to this period. However, no other post holes have been found in the bedrock and there are no clearly defined structures until Real 3 (c. 750–700 BCE) times. Some evidence of the earliest occupation was doubtless erased by the residents cleaning and living on the bedrock surface throughout the Early Middle Preclassic. While some areas were smoothed, others were left rough. At some point, the northern edge of the basal platform was defined by carving the bedrock (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sterile bedrock carved during the Early Middle Preclassic (Units 10 and 13, Subop. 211C). Photo: MacLellan. Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

At the western side of the platform (Subop. 211B, Units 1 and 2, near Str. 46), Burial 132 was placed in a globular chamber in the bedrock (Burham and MacLellan, 2014). There is no other evidence of Real period occupation in the western part of the Karinel Group. Burial 132 contained the skeletons of two adults, seven Real 3 phase ceramic vessels, and an infant of 1–2 months inside one of those vessels. According to Palomo, one of the adults is male and aged 35–50 years. The other is probably female and of the same age range. Three radiocarbon dates from human bone and teeth (PLD-28785: 2482 ± 20 = 767–524 BCE, 2-sigma cal.; PSU-3472: 2520 ± 20 = 779–549 BCE, 2-sigma cal.; PSU-3473: 2482 ± 20 = 767–542 BCE, 2-sigma cal.) overlap with the Real 3 phase [In this paper, Ceibal radiocarbon dates are calibrated in OxCal 4.4 using the IntCal-20 curve (Bronk Ramsey, 1995; Reimer et al., 2020).]

Two other burials at the Karinel Group have been radiocarbon dated to the Early Middle Preclassic. These burials contained no grave goods, and neither was deposited in a house platform. Ceibal Burial 160, the primary burial of an adult sexed as male, was found on the bedrock, in the area of the Terminal Classic patio group (Subop. 211C, Unit 3). After deposition, Burial 160 was cut along the skeleton's medial axis, and the right side of the body and whole skull were removed. This cut may indicate that the orientation of Burial 160 related to a construction project. Two teeth were left behind. Bone from Burial 160 was radiocarbon dated to the Real 2 or Real 3 phase (PSU-5950: 2640 ± 20 = 826–789 BCE, 2-sigma cal.). Burial 128 was also found on the bedrock, in the area of Str. 46, not far from Burial 132. This burial of an adult male was missing the skull; the left arm, scapula, and hand; both tibiae, but not the fibulae; and the right femur. As with Burial 160, two teeth were found in the area of the missing head. Since the remaining bones were articulated, the burial is primary. It is more likely that selected skeletal elements were removed upon disturbance or reentry than that the bones (e.g., tibiae but not fibulae) were surgically removed while fleshed. Human bone from Burial 128 was radiocarbon dated to the Real 3, Escoba 1, or Escoba 2 phase (PSU-5949: 2510 ± 20 = 776–545 BCE, 2-sigma cal.). Since a large amount of construction activity occurred near the bedrock at the Karinel Group, over a long time period, bones from Burial 128 and Burial 160 may have been removed opportunistically for use in rituals or unknown activities.

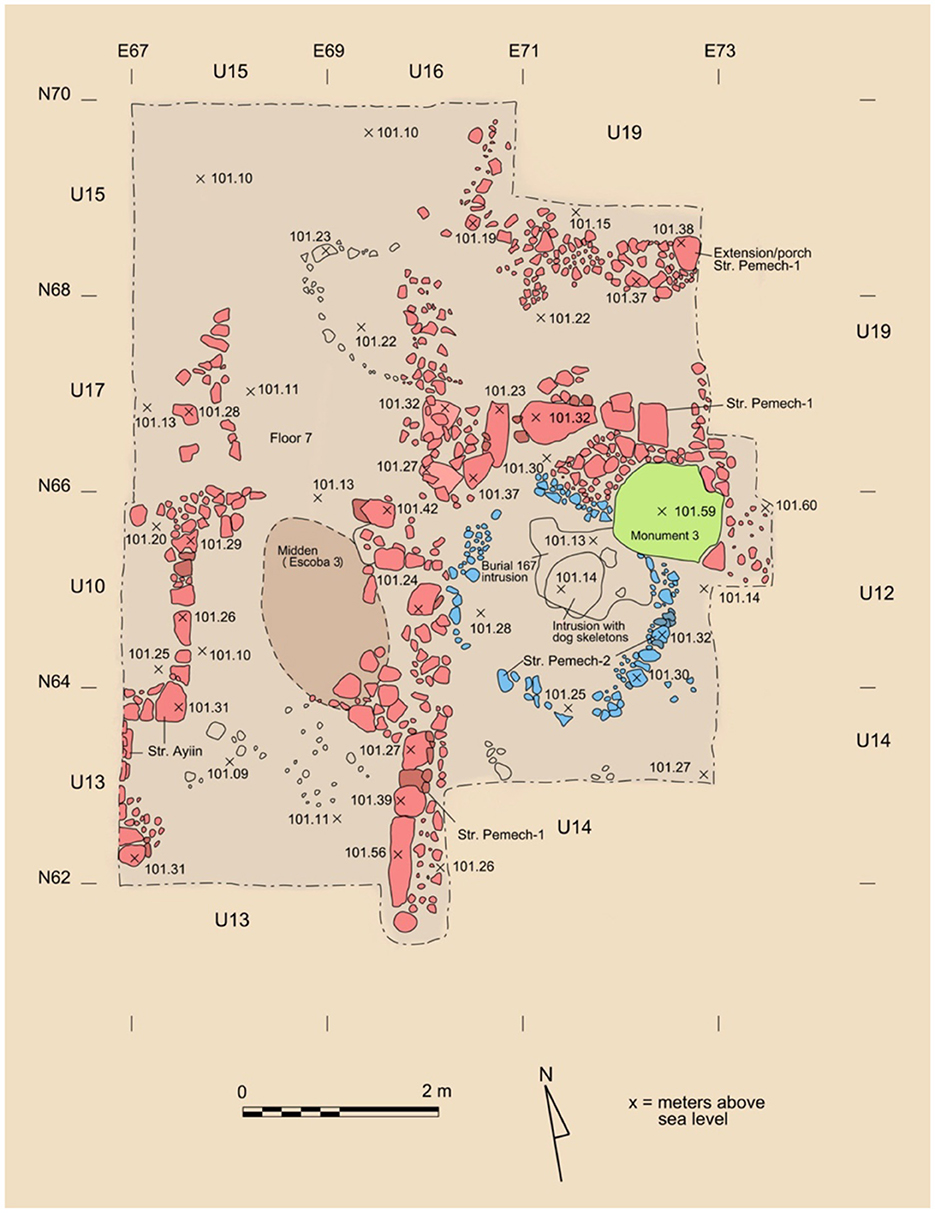

During the Real 3 phase, residents of the Karinel Group expanded the basal platform to the north. Early Middle Preclassic platforms in this part of the group are poorly preserved, but middens indicate a residential function. A low circular platform with a diameter of 2.8 m, Structure Pemech-2, was built at this time (Figure 4) (MacLellan, 2019a, p. 416, 417). Around the transition from the Real phase to the Escoba phase (c. 700 BCE), Ceibal Monument 3 was placed above the circular platform. This monument is a limestone boulder, roughly modified and about 1 m3 in size. Structure Pemech-2 and then Monument 3 may have served as an altar. Monument 3 remained exposed throughout the entire Preclassic period and was incorporated into later structures.

Figure 4. Locations of Str. Pemech-2 (blue) and Monument 3 (green), with Late Middle Preclassic Strs. Pemech-1 and Ayiin (pink). Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

Many fragments of Middle Preclassic (Real and Escoba) ceramic figurines were recovered from the Karinel Group. Their locations in middens and construction fills provide little information about their use. However, these figurines may have been part of domestic rituals (Cyphers Guillén, 1993; Marcus, 1998; Grove and Gillespie, 2002; Love and Guernsey, 2007).

Late Middle Preclassic

As indicated by domestic middens, the Karinel Group remained residential throughout the Late Middle Preclassic period. The earliest clear patio was created at the beginning of the Escoba-Mamom phase, when an area of natural marl soil was leveled and cleaned (Subop. 211C). A thin marl platform, Structure Saqb'in-4, was constructed at the east side of this leveled area and later rebuilt as Saqb'in-3. Each of the two successive surfaces was only a few centimeters thick. The earlier version was white, while Saqb'in-3 was mottled red and white (Figure 5). One exposed post hole indicates that this platform supported a superstructure. The extent of the structure could not be determined, but it was rectangular or apsidal. This structure resembles Real 3 phase house platforms excavated by Triadan in the site core (Triadan et al., 2017, p. 248–251, 257, 258).

Figure 5. Patio floor and edge of Str. Saqb'in-3 from above (Unit 5, Subop. 211C). Post hole above north arrow. Photo: MacLellan. Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

During the Escoba 2 phase (c. 600–450 BCE), the Karinel residents began to build taller house platforms with walls made of rough limestone blocks, including Structures Saqb'in-2 and Saqb'in-1 on the eastern side of the patio (Figure 6). They also built circular platform Structure Sutsu in the patio (MacLellan, 2019a). This round structure is about 0.40 m tall, with a diameter of 5 m. Like other Middle Preclassic round platforms across the Maya lowlands, Structure Sutsu did not have a superstructure and was likely used for performances, such as dances (Aimers et al., 2000; Hendon, 2000; MacLellan and Castillo, 2022).

Figure 6. Locations of Str. Sutsu and Str. Saqb'in-1 (purple). Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

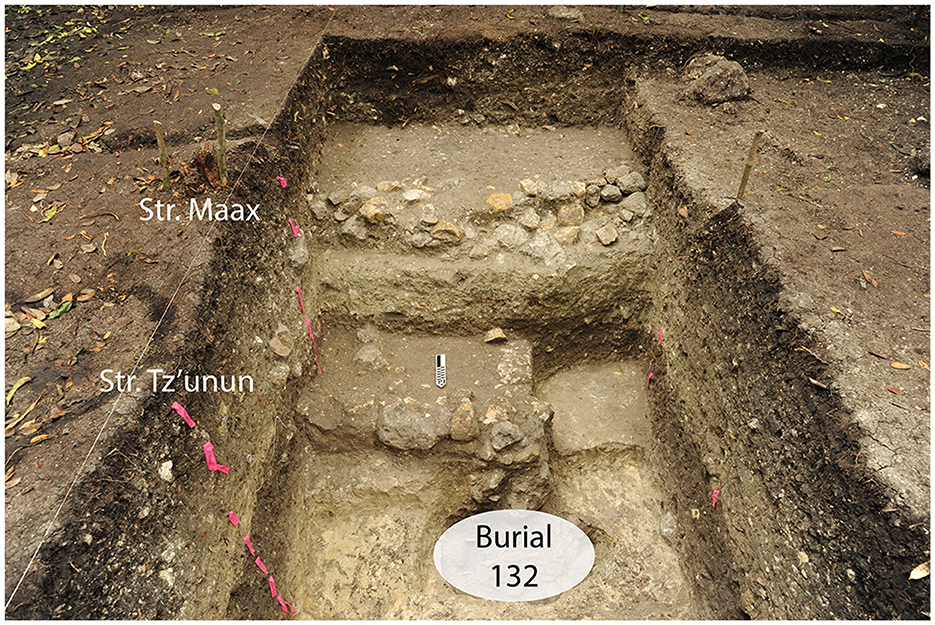

At the western side of the Karinel Group (Subop. 211B), the basal platform was extended by the addition of rectangular Structure Tz'unun, one corner of which was located precisely above Burial 132 (Figure 7). Household crafting activities in this area included obsidian blade manufacture, as evidenced by a knapper's midden (Aoyama et al., 2017; Sharpe and Aoyama, 2023).

Figure 7. Str. Tz'unun above Burial 132 (Subop. 211B). Photo: MacLellan. Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

Below Structure 47, a small temple at the southern edge of the group (Tourtellot, 1988, p. 171–174), we encountered another circular platform, contemporaneous with Sutsu (MacLellan and Castillo, 2022, p. 7, 8). Structure 47-Sub-3 has a diameter of about 6 m and is about 0.2 m tall. While Structure Sutsu has an outer wall of rough limestone blocks, the wall of 47-Sub-3 is made up blocks of soft, white limestone. Unlike the rest of the Karinel Group, the area around 47-Sub-3 was resurfaced with several successive, thin, plaster floors.

During the Escoba 3 phase (c. 450–350 BCE), rectangular house platforms (Strs. Pemech-1, Ayiin) were constructed around the patio (Figure 4). A large midden in an intrusion in the patio may be evidence of a communal feast (MacLellan and Castillo, 2022, p. 6–8). On the western side of the Karinel Group (Subop. 211B), an extension of the basal platform, called Structure Maax, was built over Structure Tz'unun (Figure 7), and a human scapula was left in one of the retaining walls.

Late Middle Preclassic-Late Preclassic transition

As at Cuello, the transition to the Late Preclassic period, around 350 BCE, was a time of major changes at the Karinel Group. At that point, ritual activity in Ceibal's residential groups became similar to rituals conducted in the public center and probably focused on emergent elites (Burham and MacLellan, 2014; MacLellan, 2019c). Semi-public spaces were constructed in outlying groups (Burham et al., 2020; Burham, 2022). Ritual caching was undertaken in residential areas. Ceramic figurines became rare. Circular Structures Sutsu and 47-Sub-3 were buried.

The Late Middle Preclassic patio group at the Karinel Group was filled in, creating an open space. Residents created the first cache of a complete ceramic vessel (Cache 175) and deposited a human ilium above the buried dwellings (MacLellan, 2019c).

Late Preclassic

During the Cantutse-Chicanel 1 phase (c. 350–300 BCE), circular Structure 47-Sub-3 was replaced by a rectilinear structure. As during the Escoba-Mamom phase, several successive, thin, plaster and burned clay floors covered the area of Str. 47. Meanwhile, Structure 45a-Sub-1 was built above the buried Middle Preclassic patio group. This long platform with a front terrace faced south, toward a yellow plaster floor (Figure 8). This building resembles the contemporaneous Structure 312 at Cuello. At least one superstructure stood on the platform, but it is unclear whether this was residential. This part of the group may have become a semi-public space during the Cantutse phase. Although the architecture was dramatically transformed, the top of Monument 3 was still visible.

Figure 8. Late Preclassic Str. 45a-Sub-1 (Subop. 211C). Photo: MacLellan. Courtesy of Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project.

Unlike many outlying residential groups at Ceibal and Platform 34 at Cuello, the Karinel Group never featured a temple pyramid. This might be due to the group's proximity to the Central Plaza. Structure 47 may have served as a special ritual space for the household, judging by its unusual architecture. During the early part of the Terminal Preclassic (Protoclassic) period (c. 50 BCE – 150 CE), a cache of 18 ceramic vessels (Cache 159) was placed in front of Structure 47 (Subop. 211A) and resembled contemporaneous caches in the Central Plaza (Burham and MacLellan, 2014; MacLellan, 2019c).

Discussion

During the Preclassic period, the lowland Maya went from mobile horticulturalists to sedentary farmers, living atop permanent house platforms that were rebuilt many times. This transition was not uniform across the lowlands. Communities in different regions adopted different aspects of sedentism at different times. The social processes and political strategies involved in the development of complex Maya society also varied geographically (Table 2). A comparison of the early architecture and mortuary practices of Cuello and Ceibal highlights that variation.

At Ceibal, early public ceremonial architecture and caches point to important interactions with groups in Chiapas and the Gulf Coast area. Although we do not dismiss the possibility that earlier durable domestic architecture existed, the lack of unequivocal evidence for such constructions before 750 BCE suggests that a significant portion of the population around Ceibal maintained some level of residential mobility for a few generations after the plaza's foundation (Inomata et al., 2015a,b). Households did not constantly occupy and renovate domestic structures. Instead, they may have relocated seasonally or every few years. In this way, Ceibal resembles Yaxuná and differs from sites in northern Belize and the Belize Valley, where permanent house platforms and formal patio groups were built around 1000 BCE. By the Late Middle Preclassic, however, the people of Ceibal were also occupying and rebuilding patio groups over generations.

Comparing the mortuary practices of northern Belize to those of the rest of the lowlands reveals major differences in social processes. The region is unusual in its high quantity of Middle Preclassic burials. Few Early Middle Preclassic burials are known from elsewhere in the lowlands, and even Late Middle Preclassic burials are relatively uncommon (Ringle, 1985, p. 288–313; Awe, 1992, p. 334, 335; Wrobel et al., 2021). The practice of burying the dead in house platforms began very early at Cuello, around 800 BCE. Other probable pre-Mamom examples can be seen at K'axob (Storey, 2004), Altun Ha (Pendergast, 1982, p. 170–204), and Santa Rita Corozal (Chase et al., 2018), also in northern Belize. Burials in house platforms became common much later elsewhere in the lowlands. Several burials at Dzibilchaltun, in northern Yucatan, suggest the custom began there during the Late Middle Preclassic (Andrews and Andrews, 1980, p. 21–41). The few Late Middle Preclassic burials found at Cahal Pech do not seem to be inside dwellings (Awe, 1992; Lee and Awe, 1995). At Ceibal and its satellite site Caobal, Burial 11 (Tourtellot, 1990) and Burial AN4 (Munson, 2012) were placed in house platforms at the end of the Late Middle Preclassic, during the Escoba 3 phase. The few Middle Preclassic burials at the Karinel Group were not located within houses.

The Bladen and Lopez phase burials at Cuello are more richly furnished than contemporaneous burials outside northern Belize. Based on the large sample of grave goods, Hammond (1999) sees an increase in social differentiation during the Lopez phase. Cuello Burial 160 included ornaments made from jade imported over a long distance and a human skull pendant that might represent a trophy head and individual success in battle – hinting at an “exclusionary” political strategy (sensu Blanton et al., 1996).

At K'axob, near Cuello, McAnany found a similarly complex Preclassic burial record, beginning c. 800–600 BCE. Although burials beneath houses date to the foundation of K'axob (Storey, 2004, p. 110–112), elaborate ancestor veneration practices (including bundled secondary burials) did not appear until the Late Preclassic period. As others have noted, descriptions and drawings of Late and Terminal Preclassic K'axob burials used to argue for ancestor veneration are very similar to burials interpreted as human sacrifices at Cuello, including Mass Burial 1 described above (Hammond, 1991; McAnany, 2004; Hageman, 2016). Hammond (1999, p. 55) points out that some children are buried in house platforms with grave goods, and that children do not fit the literal definition of ancestors. Nevertheless, Hammond's (1999) analysis of the emergence of inequality at Cuello through mortuary data mirrors McAnany's study of ancestor veneration at K'axob.

The ancestor veneration model developed by McAnany has been very influential throughout the lowlands but does not fit data from every region. For example, Brown and Robin interpret Middle Preclassic burials in public plazas at Xunantunich and Chan, both in the Belize Valley, as examples of ancestor veneration (Robin et al., 2012, p. 126–128; Brown, 2017; Robin, 2017; Brown et al., 2018, p. 108–110). Like Ceibal Burials 128 and 160, these burials were disturbed in antiquity, when elements were removed, probably for ritual use. Like Ceibal Burials 128 and 160 and unlike the K'axob cases, there were no associated grave goods – making it hard to argue for high status. Importantly, McAnany argues that Preclassic ancestor veneration was undertaken by a lineage within a residence, and not by an entire community in a public space. Even if the burials at Xunantunich and Chan are of high-status individuals, there is no evidence that the status was inherited or associated with land rights, which are key elements of McAnany's model. If the burials at Xunantunich and Chan were of venerated leaders, they present a more collective view of ancestors – and a more “corporate” political strategy (sensu Blanton et al., 1996). In addition, interpretations of Preclassic round platforms in the Belize Valley as ancestor shrines are based on unlikely interpretations of stratigraphy (MacLellan and Castillo, 2022, p. 3). DeLance and Awe argue that Middle Preclassic figurines at Cahal Pech represent ancestor veneration, but their evidence comes from the reuse of these figurines in Classic period contexts (DeLance and Awe, 2022). Inverting McAnany's model, they see ancestor veneration as a less hierarchical, cooperative practice that was replaced at the beginning of the Late Preclassic by a more hierarchical, competitive system.

Domestic architecture at Ceibal does not show increasing inequality related to burials in house floors, as seen at Cuello and K'axob. While Karinel Group house platforms were rebuilt multiple times, neither the houses nor Structure 47 was built over an ancestral burial. Late Middle Preclassic Structure Tz'unun was intentionally built above Early Middle Preclassic Burial 132, suggesting early burials might have tied Ceibal residents to places during the transition to fully sedentary life. However, there was no subsequent social differentiation in Late Middle Preclassic burials. The rituals carried out on circular structures at Ceibal, Cahal Pech, and elsewhere probably created unranked, rather than hierarchical, relationships among households (MacLellan and Castillo, 2022). At Ceibal, the proximity of Platform K'at (and potentially the earlier Platform Sulul) to the Central Plaza hints that Middle Preclassic status was tied to public rituals and cosmological symbols, rather than land rights. The same pattern is seen at Plaza B of Cahal Pech (Awe, 1992, p. 112–137).

Although scholars working across the Maya area reference ancestor veneration, the process described by McAnany differs from the mortuary evidence seen at Ceibal or in the Belize Valley. Archaeologists should be explicit about what specific social processes we refer to when we invoke a concept like “ancestor veneration.” The continuum of cooperative to competitive strategies, developed by Blanton et al. (1996), is one lens through which to differentiate such processes. For example, one might describe the northern Belize mortuary practices as exclusionary ancestor veneration and the Chan and Xunantunich plaza examples as collective ancestor veneration. Ceibal Burial 136, in a public space, would also fall on the collective side. In contrast, the construction of Str. Tz'unun over Burial 132 at the Karinel Group might represent a more exclusionary effort, connecting a particular household across generations. However, most of the evidence for exclusionary ancestor veneration cited in northern Belize was absent at Ceibal throughout the Middle Preclassic.

Why did exclusionary rituals related to land rights emerge so early in northern Belize? There is probably no simple answer, but the relatively dense population, beginning in the Archaic period (Rosenswig, 2021; Valdez et al., 2021), must have played a role. Feinman and Neitzel use ethnographic and archaeological evidence from around the world to argue that societies undergo reorganizations at key demographic thresholds, due to increased social stresses caused by human cognitive limitations (Feinman and Neitzel, 2023). If these societies do not fission into smaller groups, then “institutions” – groups with shared objectives and regularized practices (Holland-Lulewicz et al., 2020) – are necessary to socially bind them together. This model is about interpersonal relationships, rather than subsistence or carrying capacity. However, institutions require labor and other resources, and Feinman and Neitzel argue that if those resources, such as land rights, are heritable and monopolizable, political strategies will be exclusionary and will increase inequality. The founders of Ceibal lived in small, dispersed, semi-mobile groups and exploited many wild resources in addition to planting maize. Meanwhile, the founders of Cuello may have been overwhelmed by social tensions and in greater competition for resources. The ancestor veneration identified by McAnany may represent the institutionalized leadership that the larger communities of northern Belize required for social aggregation. Although ancestor veneration held communities together, it also created hierarchies, with some lineages monopolizing the best farmland and rising in social status (McAnany, 1995).

In terms of chronology, mortuary data from Cuello and K'axob suggest a gradual increase in inequality over the course of the Preclassic. At Ceibal and in other parts of the lowlands, that social change seems more abrupt. Around 350 BCE (the transition to the Chicanel ceramic phase and Late Preclassic period), Ceibal and Cuello were part of a lowlands-wide shift in ideology that included changes in spatial organization and ritual practices at residential groups. Generations-old patio groups at Cuello, Ceibal, Cahal Pech, Dzibilchaltun, and elsewhere were buried to create more open spaces. Temple pyramids were created in peripheral, residential complexes (Ringle, 1999; Munson and Pinzón, 2017; Burham et al., 2020; Burham, 2022). At Ceibal, domestic and public rituals became much more similar (Burham and MacLellan, 2014; MacLellan, 2019c). The earliest clear ritual caches (intrusive deposits of items like whole ceramic vessels) in residential areas are dated to the Middle Preclassic-Late Preclassic transition (MacLellan, 2019c). Ceramic figurines, likely used in Middle Preclassic household rituals, fell out of favor (Guernsey, 2020; DeLance and Awe, 2022). The more homogenous ritual practices of the Late Preclassic seem to be focused on emergent elites, as certain kin groups were – socially and economically – able to build their own pyramids and create their own ritual caches away from communal public plazas. There were doubtless multiple historically contingent causes of this change, but a major increase in population across the lowlands is one important factor. Maya communities may have crossed a demographic threshold that favored the development of exclusionary political strategies, and resources like farmland and trade routes may have become easier to monopolize (Feinman and Neitzel, 2023, p. 9). By the end of the Late Preclassic (c. 100 BCE), the earliest royal families had emerged.

Conclusion

Variation in the archaeological records of Cuello and Ceibal shows that the Middle Preclassic Maya cannot be simply labeled as “collective” or “not collective”. The relatively dense population of northern Belize facilitated the early development of heritable inequality and competitive sociopolitical strategies, including ancestor veneration. Meanwhile, at Ceibal and in the Belize Valley (and probably also at Aguada Fénix, throughout Petén, and in Yucatán), Middle Preclassic ritual practices and leadership were more collective, despite the rebuilding of patio groups over generations. By focusing on specific political strategies and employing Blanton and colleagues' continuum of collective to exclusionary, one gains a more nuanced understanding of relationships among residential mobility, ritual, leadership, and inequality. This analysis has implications beyond the Maya area, as archaeologists increasingly recognize that the transition to sedentary life is a complex set of processes that occurred in different combinations at different rates around the globe and throughout history.

Author contributions

JM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research at the Karinel Group was funded by the National Science Foundation (BCS-1518794) and the Alphawood Foundation of Chicago (grant to Inomata and Triadan). Additional financial support was provided by Dumbarton Oaks and the University of Arizona (School of Anthropology, Graduate and Professional Student Council, Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Institute). A URECA-x grant from Wake Forest University was used to hire a student to prepare some of the figures in this article. Publication fees were covered by Wake Forest University's Open Access Publishing Fund.

Acknowledgments

This article relies heavily on publications of the Cuello Archaeological Project (1975–2002), directed by Norman Hammond. It began as part of a symposium in honor of Hammond at the 79th annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (2014): “Preclassic Maya Civilization is No Longer a Contradiction in Terms,” organized by Francisco Estrada-Belli and Astrid Runggaldier. Harvard University's Seibal Archaeological Project (1964–1968) provided the foundation for the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project. I am grateful to Takeshi Inomata, Daniela Triadan, Melissa Burham, Flory Pinzón, and all my Ceibal colleagues. Permits were granted by the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, Ministry of Culture and Sports, Guatemala. Alejandra Cordero and Evelyn Mejía helped supervise Karinel Group excavations. Juan Manuel Palomo analyzed human remains from Ceibal. Inomata provided comments on an early version of this manuscript. Undergraduate student Elaine Lu prepared some of the figures. I am grateful to three peer reviewers for their time and constructive feedback. Finally, thank you to Gary Feinman and Victor Thompson for the invitation to contribute to this collection.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aimers, J. J., Powis, T. G., and Awe, J. J. (2000). Preclassic round structures of the upper belize river valley. Latin Am. Antiq. 11, 71–86. doi: 10.2307/1571671

Andrews, E. W., and Andrews, V. E. W. (1980). Excavations at Dzibilchaltun, Yucatan, Mexico, Middle American Research Institute Publications. New Orleans: Tulane University.

Andrews, E. W., Bey, V. G. J., and Gunn, C. M. (2018). “The Earliest Ceramics of the Northern Maya Lowlands,” in Pathways to Complexity: A View from the Maya Lowlands, eds M. K. Brown, G. J. Bey (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 49–86.

Andrews, E. W., and Hammond, V. N. (1990). Redefinition of the Swasey phase at Cuello, Belize. Am. Antiq. 55, 570–584. doi: 10.2307/281287

Aoyama, K. (2017). Ancient Maya economy: lithic production and exchange around Ceibal, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoamerica 28, 279–303. doi: 10.1017/S0956536116000183

Aoyama, K., Inomata, T., Triadan, D., Pinzón, F., Palomo, J. M., MacLellan, J., et al. (2017). Early Maya ritual practices and craft production: late middle preclassic ritual deposits containing obsidian artifacts at Ceibal, Guatemala. J. Field Archaeol. 42, 408–422. doi: 10.1080/00934690.2017.1355769

Awe, J. J. (1992). Dawn in the Land Between the Rivers: Formative Occupation at Cahal Pech, Belize, and its Implications for Preclassic Development in the Maya Lowlands (Ph.D.). London: University of London.

Binford, L. R. (1971). “Mortuary practices: their study and potential,” in Approaches to the Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices, Memoir, ed J. A. (Washington, DC: Brown Society for American Archaeology), 6–29.

Blanton, R. E. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CL: University Press of Colorado.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. New York, NY: Springer.

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Peregrine, P. N. (1996). A dual-processual theory for the evolution of mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1086/204471

Bronk Ramsey, C. (1995). Radiocarbon calibration and analysis of stratigraphy: the oxcal program. Radiocarbon 37, 425–430. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200030903

Brown, M. K. (2017). “E groups and ancestors: the sunrise of complexity at xunantunich, belize,” in Maya E Groups: Calendars, Astronomy, and Urbanism in the Early Lowlands, eds D. A. Freidel, A. F. Chase, A. S. Dowd (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 386–411.

Brown, M. K., Awe, J. J., and Garber, J. F. (2018). “The Role of Ideology, Religion, and Ritual in the Foundation of Social Complexity in the Belize River Valley,” in Pathways to Complexity: A View from the Maya Lowlands, eds M. K. Brown, G. J. Bey (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 87–116.

Brown, M. K., and Garber, J. F. (2005). “The development of middle formative architecture in the Maya lowlands: the blackman eddy, belize, example,” in New Perspectives on Formative Mesoamerican Cultures, ed T. G. Powis (Oxford: Archaeopress), 39–49.

Brück, J. (1999). “What's in a settlement? Domestic practice and residential mobility in early bronze age southern England,” in Making Places in the Prehistoric World, eds J. Brück, M. Goodman (London: Routledge), 52–75.

Brück, J. (2004). Material Metaphors: the relational construction of identity in early bronze age burials in Ireland and Britain. J. Soc. Archaeol. 4, 307–333. doi: 10.1177/1469605304046417

Burger, R. L., and Rosenswig, R. M. (2012). Early New World Monumentality. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Burham, M. (2022). Sacred sites for suburbanites: organic urban growth and neighborhood formation at preclassic Ceibal, Guatemala. J. Field Archaeol. 47, 262–283. doi: 10.1080/00934690.2022.2052583

Burham, M., Inomata, T., Triadan, D., and MacLellan, J. (2020). “Ritual practice, urbanization, and sociopolitical organization at preclassic Ceibal,” in Approaches to Monumental Landscapes of the Ancient Maya, eds Houk, B.A., Arroyo, B., Powis, T.G. (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 61–84.

Burham, M., and MacLellan, J. (2014). Thinking outside the plaza: ritual practices in preclassic Maya residential groups at Ceibal, Guatemala. Antiq. Proj. Gallery 88, 1–4. Available online at: https://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/burham340

Canuto, M. A. (2016). “Middle Preclassic Maya Society: Tilting at Windmills or Giants of Civilization?” in The Origins of Maya States, eds L. P. Traxler, and R. J. Sharer (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press), 461–506.

Carballo, D., Roscoe, P., and Feinman, G. M. (2014). Cooperation and collective action in the cultural evolution of complex societies. J. Archaeol. Method Theor. 21, 98–133. doi: 10.1007/s10816-012-9147-2

Carballo, D. M. (2013). Cooperation and Collective Action: Archaeological Perspectives. Boulder, CL: University Press of Colorado.

Chase, A. S. Z., Chase, D. Z., and Chase, A. F. (2018). Situating Preclassic Interments and Fire-Pits at Santa Rita Corozal (No. 15), Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology. Belize: Institute of Archaeology.

Clark, J. E., and Hansen, R. D. (2001). “The Architecture of Early Kingship: Comparative Perspectives on the Origins of the Maya Royal Court,” in Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya: Volume 2, Data and Case Studies, Vol. 2 (Boulder, CL: Westview Press), 1–45.

Coe, W. R. (1965). Tikal, Guatemala, and emergent civilization. Science 147, 1401–1419. doi: 10.1126/science.147.3664.1401

Crumley, C. L. (1987). “A dialectical critique of hierarchy,” in Power Relations and State Formation, eds T. C. Patterson, C. W. Gailey (Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association), 155–169.

Crumley, C. L. (1995). Heterarchy and the analysis of complex societies. Archaeol. Papers Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 6, 1–5. doi: 10.1525/ap3a.1995.6.1.1

Crumley, C. L. (2003). “Alternative forms of social order,” in Heterarchy, Political Economy, and the Ancient Maya: The Three Rivers Region of the East-Central Yucatán Peninsula, eds V. L. Scarborough, F. Valdez, N. Dunning (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press), 136–145.

Cyphers Guillén, A. (1993). Women, rituals, and social dynamics at ancient chalcatzingo. Latin Am. Antiq. 4, 209–224. doi: 10.2307/971789

DeLance, L., and Awe, J. J. (2022). “The complexity of figurines: ancestor veneration at cahal pech, Cayo, Belize,” in Framing Complexity in Formative Mesoamerica, eds L. DeLance, G. M. Feinman (Boulder, CL: University Press of Colorado), 226–250.

DeMarrais, E., and Earle, T. (2017). Collective action theory and the dynamics of complex societies. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 46, 183–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041409

Dietrich, O., Köksal-Schmidt, Ç., Notroff, J., and Schmidt, K. (2013). Establishing a radiocarbon sequence for göbekli tepe: state of research and new data. Neo-Lithics Newsletter Southwest Asian Neolithic Res. 15, 36–41. Available online at: https://www.exoriente.org/repository/NEO-LITHICS/NEO-LITHICS_2013_1.pdf

Estrada-Belli, F. (2011). The First Maya Civilization: Ritual and Power Before the Classic Period. New York, NY: Routledge.

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2018). Collaborative and competitive strategies in the variability and resiliency of large-scale societies in mesoamerica. Economic Anthropol. 5, 7–19. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12098

Feinman, G. M., and Neitzel, J. E. (2023). The social dynamics of settling down. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 69, 101468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101468

Gerhardt, J. C. (1988). Preclassic Maya Architecture at Cuello, Belize, BAR International Series. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Gibson, J. L. (2006). Navels of the earth: Sedentism in early mound-building cultures in the lower MIssissippi valley. World Archaeol. 38, 311–329. doi: 10.1080/00438240600694081

Goldstein, L. (1981). “One-dimensional archaeology and multi-dimensional people: spatial organisation and mortuary analysis,” in The Archaeology of Death, eds R. Chapman, L. Kinnes, K. Randsborg (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 53–69.

Grove, D. C., and Gillespie, S. D. (2002). “Formative domestic ritual at chalcatzingo, morelos,” in Domestic Ritual in Ancient Mesoamerica, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Monograph, eds P. Plunket (Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California), 11–19.

Guernsey, J. (2020). Human Figuration and Fragmentation in Preclassic Mesoamerica: From Figurines to Sculpture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hageman, J. B. (2016). “Where the Ancestors Live: Shrines and Their Meaning among the Classic Maya,” in The Archaeology of Ancestors: Death, Memory, and Veneration, eds E. Hill, J. B. Hageman (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 213–248. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvx076wp.13

Hammond, N. (1991). Cuello: An Early Maya Community in Belize. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hammond, N. (1999). “The genesis of hierarchy: mortuary and offertory ritual in the pre-classic at cuello, Belize,” in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, eds D. C. Grove, R. A. Joyce (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks), 49–66.

Hammond, N. (2005). The dawn and the dusk: beginning and ending a long-term research program at the preclassic Maya site of Cuello, Belize. Anthropol. Notebooks 11, 45–60.

Hammond, N., Bauer, J., and Hay, S. (2000). Preclassic Maya architectural ritual at cuello, Belize. Antiquity 74, 265–266. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00059172

Hammond, N., and Bauer, J. R. (2001). A preclassic Maya sweatbath at Cuello, Belize. Antiquity 75, 684–684. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00089158

Hammond, N., Bauer, J. R., and Morris, J. (2002). Squaring off: late middle preclassic architectural innovation at cuello, Belize. Antiquity 76, 327–328. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00090359

Hammond, N., Clarke, A., and Estrada-Belli, F. (1992). Middle preclassic Maya buildings and burials at cuello, Belize. Antiquity 66, 955–964. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00044884

Hammond, N., Clarke, A., and Estrada-Belli, F. (1995). The long goodbye: middle preclassic Maya archaeology at cuello, Belize. Latin Am. Antiq. 6, 120–128. doi: 10.2307/972147

Hammond, N., Clarke, A., and Robin, C. (1991a). Middle preclassic buildings and burials at cuello, belize: 1990 investigations. Latin Am. Antiq. 2, 352–363. doi: 10.2307/971783

Hammond, N., Gerhardt, J. C., and Donaghey, S. (1991b). “Stratigraphy and chronology in the reconstruction of preclassic developments at cuello,” in Cuello: An Early Maya Community in Belize, ed N. Hammond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 23–69.

Hendon, J. A. (2000). Round structures, household identity, and public performance in preclassic Maya society. Latin Am. Antiq. 11, 299–301. doi: 10.2307/972180

Hill, W. D., and Clark, J. E. (2001). Sports, gambling, and government: america's First social compact? Am. Anthropol. 103, 331–345. doi: 10.1525/aa.2001.103.2.331

Hohmann, B., Powis, T. G., and Healy, P. F. (2018). “Middle preclassic shell ornament production: implications for the development of complexity at pacbitun, belize,” in Pathways to Complexity: A View from the Maya Lowlands, eds M. K. Brown, and G. H. Bey (Gainesville,FL: University Press of Florida), 117–146.

Holland-Lulewicz, J., Conger, M. A., Birch, J., Kowalewski, S. A., and Jones, T. W. (2020). An institutional approach for archaeology. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 58, 101163. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101163

Inomata, T. (2006). Plazas, performers, and spectators: political theaters of the classic Maya. Curr. Anthropol. 47, 805–842. doi: 10.1086/506279

Inomata, T. (2017a). The emergence of standardized spatial plans in southern mesoamerica: chronology and interregional interactions viewed from Ceibal, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoamerica 28, 329–355. doi: 10.1017/S0956536117000049

Inomata, T. (2017b). “The Isthmian Origins of the E Group and Its Adoption in the Maya Lowlands,” in Maya E Groups: Calendars, Astronomy, and Urbanism in the Early Lowlands, eds D. A. Freidel, A. F. Chase, A. S. Dowd, J. Murdock (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 215–252.

Inomata, T., Fernandez-Diaz, J. C., Triadan, D., García Mollinedo, M., Pinzón, F., García Hernández, M., et al. (2021). Origins and spread of formal ceremonial complexes in the Olmec and Maya regions revealed by airborne lidar. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1487–1501. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01218-1

Inomata, T., MacLellan, J., and Burham, M. (2015a). The construction of public and domestic spheres in the preclassic Maya lowlands. Am. Anthropol. 117, 519–534. doi: 10.1111/aman.12285

Inomata, T., MacLellan, J., Triadan, D., Munson, J., Burham, M., Aoyama, K., et al. (2015b). Development of sedentary communities in the Maya lowlands: Coexisting mobile groups and public ceremonies at Ceibal, Guatemala. PNAS 112, 4268–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501212112

Inomata, T., Ortiz, R., Arroyo, B., and Robinson, E. J. (2014). Chronological Revision of Preclassic Kaminaljuyú, Guatemala: implications for social processes in the southern Maya area. Latin Am. Antiq. 25, 377–408. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.25.4.377

Inomata, T., Pinzón, F., Palomo, J. M., Sharpe, A. E., Ortiz, R., Méndez, M. B., et al. (2017a). Public ritual and interregional interactions: excavations of the central plaza of group a, Ceibal. Ancient Mesoam. 28, 203–232. doi: 10.1017/S0956536117000025

Inomata, T., and Triadan, D. (2015). “Preclassic Caches from Ceibal, Guatemala,” in Maya Archaeology 3, eds C. Golden, S. Houston, and J. Skidmore (San Francisco: Precolumbia Mesoweb Press), 56–91.

Inomata, T., Triadan, D., Aoyama, K., Castillo, V., and Yonenobu, H. (2013). Early ceremonial constructions at Ceibal, Guatemala, and the origins of lowland Maya civilization. Science 340, 467–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1234493

Inomata, T., Triadan, D., MacLellan, J., Burham, M., Aoyama, K., Palomo, J. M., et al. (2017b). High-precision radiocarbon dating of political collapse and dynastic origins at the Maya site of Ceibal, Guatemala. PNAS 114, 1293–1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618022114

Inomata, T., Triadan, D., Vázquez López, V. A., Fernandez-Diaz, J. C., Omori, T., Méndez Bauer, M. B., et al. (2020). Monumental architecture at Aguada Fénix and the rise of Maya civilization. Nature 582, 530–533. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2343-4

Inomata, T., and Tsukamoto, K. (2014). “Gathering in an open space: introduction to mesoamerican plazas,” in Mesoamerican Plazas: Arenas of Community and Power, eds K. Tsukamoto, T. Inomata (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press), 3–15.

Joyce, R. A. (2004). Unintended consequences? Monumentality as a novel experience in formative mesoamerica. J. Archaeol. Method Theor. 11, 5–29. doi: 10.1023/B:JARM.0000014346.87569.4a

King, E. M. (2016). “Rethinking the role of early economies in the rise of Maya states: a view from the lowlands,” in The Origins of Maya States, eds L. P. Traxler, and R. J. Sharer (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology), 417–460.

Kosakowsky, L. J. (1987). Preclassic Maya Pottery at Cuello, Belize, Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Law, I. A., Housley, R. A., Hammond, N., and Hedges, R. E. M. (1991). Cuello: resolving the chronology through direct dating of conserved and low-collagen bone by AMS. Radiocarbon 33, 303–315. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200040339

Lee, D., and Awe, J. J. (1995). “Middle formative architecture, burials, and craft specialization: report on the 1994 investigations at the Cas Pek Group, Cahal Pech, Belize,” in Belize Valley Preclassic Maya Project: Report on the 1994 Field Season, Occasional Papers in Anthropology, eds P. F. Healy, J. J. Awe (Peterborough, ON: Trent University), 95–115.

Lesure, R. G., and Blake, M. (2002). Interpretive challenges in the study of early complexity: economy, ritual, and architecture at paso de la Amada, Mexico. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 21, 1–24. doi: 10.1006/jaar.2001.0388

Lohse, J. C. (2010). Archaic origins of the lowland Maya. Latin Am. Antiq. 21, 312–352. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.312

Lohse, J. C. (2023). “The end of an era: closing out the archaic in the Maya Lowlands,” in Pre-Mamom Pottery Variation and the Preclassic Origins of the Lowland Maya, D. S. Walker(Boulder, CL: University Press of Colorado) 33–56.

Love, M., and Guernsey, J. (2007). Monument 3 from La Blanca, Guatemala: a middle preclassic earthen sculpture and its ritual associations. Antiquity 81, 920–932. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00096009

MacLellan, J. (2019a). Preclassic Maya houses and rituals: excavations at the karinel group, Ceibal. Latin Am. Antiq. 30, 415–421. doi: 10.1017/laq.2019.15

MacLellan, J. (2019b). Households, Ritual, and the Origins of Social Complexity: Excavations at the Karinel Group, Ceibal, Guatemala (Ph.D. Dissertation). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

MacLellan, J. (2019c). Preclassic Maya caches in residential contexts: variation and transformation in deposition practices at Ceibal. Antiquity 93, 1249–1265. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2019.129

MacLellan, J., and Castillo, V. (2022). Between the patio group and the plaza: round platforms as stages for supra-household rituals in early Maya society. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 66, 101417. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101417

Marcus, J. (1998). Women's Ritual in Formative Oaxaca: Figurine-Making, Divination, Death and the Ancestors, Museum of Anthropology Memoirs. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Marcus, J., and Flannery, K. V. (2004). The coevolution of ritual and society: new c-14 dates from ancient mexico. PNAS 101, 18257–18261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408551102

McAnany, P. A. (2004). K'axob: Ritual, Work and Family in an Ancient Maya Village. Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

McAnany, P. A., Storey, R., and Lockard, A. K. (1999). Mortuary ritual and family politics at formative and early classic K'axob, Belize. Ancient Mesoam. 10, 129–146. doi: 10.1017/S0956536199101081

Morris, I. (1991). The archaeology of ancestors: the saxe/goldstein hypothesis revisited. Cambridge Archaeol. J. 1, 147–169. doi: 10.1017/S0959774300000330

Munson, J. (2012). Temple Histories and Communities of Practice in Early Maya Society: Archaeological Investigations at Caobal, Peten, Guatemala (Ph.D. Dissertation). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

Munson, J., and Pinzón, F. (2017). Building an early Maya community: archaeological investigations at Caobal, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoam. 28, 265–278. doi: 10.1017/S0956536117000050

Ortmann, A. L., and Kidder, T. R. (2013). Building mound a at poverty point, louisiana: monumental public architecture, ritual practice, and implications for hunter-gatherer complexity. Geoarchaeology 28, 66–86. doi: 10.1002/gea.21430

Parker Pearson, M. (1999). The Archaeology of Death and Burial, Texas AandM University Anthropology Series. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Pendergast, D. M. (1982). Excavations at Altun Ha, Belize, 1964-1970. Toronto, ON: Royal Ontario Museum.

Pugh, T. W. (2021). Social complexity and the middle preclassic lowland Maya. J. Archaeol. Res. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.2021.1007./s10814-021-09168-y

Reimer, P. J., Austin, W. E., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Blackwell, P. G., Bronk Ramsey, C., et al. (2020). The IntCal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0-55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2020.41

Ringle, W. M. (1985). The Settlement Patterns of Komchen, Yucatan, Mexico (Ph.D.). New Orleans: Tulane University.

Ringle, W. M. (1999). “Pre-Classic Cityscapes: Ritual Politics among the Early Lowland Maya,” in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, eds D. C. Grove, R. A. Joyce (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks), 183–223.

Robin, C. (1989). Preclassic Maya Burials at Cuello, Belize, BAR International Series. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Robin, C. (2017). “Ordinary people and east-west symbolism,” in Maya E Groups: Calendars, Astronomy, and Urbanism in the Early Lowlands, eds D. A. Freidel, A. F. Chase, S. Dowd, and J. Murdock (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 361–385.

Robin, C., Meierhoff, J., Kestle, C., Blackmore, C., Kosakowsky, L. J., Novotny, A. C., et al. (2012). “Ritual in a farming community,” in Chan: An Ancient Maya Farming Community, ed C. Robin (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 113–132.

Rosenswig, R. M. (2010). The Beginnings of Mesoamerican Civilization: Inter-Regional Interaction and the Olmec. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenswig, R. M. (2021). Opinions on the lowland Maya Late archaic period with some evidence from northern Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica 32, 461–474. doi: 10.1017/S0956536121000018

Rosenswig, R. M., VanDerwarker, A. M., Culleton, B. J., and Kennett, D. J. (2015). Is it agriculture yet? Intensified maize-use at 1000 cal BC in the Soconusco and Mesoamerica. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 40, 89–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2015.06.002

Sabloff, J. A. (1975). Excavations at Seibal, Department of Petén, Guatemala: Ceramics, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Saturno, W. A. (2009). “Centering the Kingdom, Centering the King: Maya Creation and Legitimization at San Bartolo,” in The Art of Urbanism: How Mesoamerican Kingdoms Represented Themselves in Architecture and Imagery, eds W. L. Fash, L. López Luján (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks), 111–134.

Saunders, J., Mandel, R., Sampson, C., Allen, C., Allen, E., Bush, D., et al. (2005). Watson Brake, a Middle Archaic mound complex in northeast Louisiana. Am. Antiq. 70, 631–668. doi: 10.2307/40035868

Saxe, A. A. (1970). Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices (Ph.D.). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Schmidt, K. (2010). Gobekli Tepe – the stone age sanctuaries: new results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Docum. Praehistor. 37, 239–255. doi: 10.4312/dp.37.21

Sharpe, A. E. (2019). The ancient shell collectors: two millenia of marine shell exchange at Ceibal, Guatemala. Anc. Mesoam. 30, 493–516. doi: 10.1017/S0956536118000366

Sharpe, A. E., and Aoyama, K. (2023). Lithic and faunal evidence for craft production among the middle preclassic Maya at Ceibal, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoam. 34, 407–431. doi: 10.1017/S0956536122000049

Smith, A. L. (1982). Excavations at Seibal, Department of Peten, Guatemala: Major Architecture and Caches, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Stanton, T. W., Dzul Góngora, S., Collins, R. H., and Martín Morales, R. (2022). “Pottery and society during the Preclassic Period at Yaxuná, Yucatán,” in Framing Complexity in Formative Mesoamerica, eds L. DeLance, G. M. Feinman (Boulder, CL: University Press of Colorado), 55–85.

Storey, R. (2004). “Ancestors: bioarchaeology of the human remains of K'axob,” in K'axob: Ritual, Work, and Family in an Ancient Maya Village, Monumenta Archaeologica, ed P. A. McAnany (Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California), 109–138.

Sullivan, L. A., Awe, J. J., and Brown, M. K. (2018). “The cunil complex: early villages in belize,” in Pathways to Complexity: A View from the Maya Lowlands, eds M. K. Brown, G. J. Bey (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida), 35–48.

Tourtellot, G. (1988). Excavations at Seibal, Department of Petén, Guatemala: Peripheral Survey and Excavation, Settlement and Community Patterns, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Tourtellot, G. (1990). Excavations at Seibal, Department of Peten, Guatemala: Burials: A Cultural Analysis, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Triadan, D., Castillo, V., Inomata, T., Palomo, J. M., Méndez, M. B., Cortave, M., et al. (2017). Social transformations in a middle preclassic community: elite residential complexes at Ceibal. Ancient Mesoam. 28, 233–264. doi: 10.1017/S0956536117000074

Turner, V. W. (1969). “Humility and hierarchy: the liminality of status elevation and reversal,” in The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, eds V. W. Turner (Chicago, AL: Springer), 166–203.

Turner, V. W. (1974). Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.