- 1GRASIA Research Group, Knowledge Technology Institute, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- 2Department of Sociology, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

- 3Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

Peer production communities are based on the collaboration of communities of people, mediated by the Internet, typically to create digital commons, as in Wikipedia or free software. The contribution activities around the creation of such commons (e.g., source code, articles, or documentation) have been widely explored. However, other types of contribution whose focus is directed toward the community have remained significantly less visible (e.g., the organization of events or mentoring). This work challenges the notion of contribution in peer production through an in-depth qualitative study of a prominent “code-centric” example: the case of the free software project Drupal. Involving the collaboration of more than a million participants, the Drupal project supports nearly 2% of websites worldwide. This research (1) offers empirical evidence of the perception of “community-oriented” activities as contributions, and (2) analyzes their lack of visibility in the digital platforms of collaboration. Therefore, through the exploration of a complex and “code-centric” case, this study aims to broaden our understanding of the notion of contribution in peer production communities, incorporating new kinds of contributions customarily left invisible.

Introduction

What is value? Aristotle's writings (Brown, 2009) on value as, in essence, an exchange of two things; Adam Smith's dichotomy of value in use and value in exchange (Robertson and Taylor, 1957); and the identification by Marx and Engels (1990) of concrete and abstract forms of labor associated to those; are just a few examples of the myriad of conceptualizations historically discussed around the concept of value.

In this article, we explore perceptions of value in the context of the collaborative economy, in which forms of value are increasingly created by crowds and communities of diverse participants. The growth of the collaborative economy has encompassed an increasing lack of common ways to assess, control and measure these forms of value (Arvidsson and Peitersen, 2013). These changes can be understood in the wider context of the Information Economy, in which, as a result of changes in technological conditions, information has become a fundamental source of productivity and power (Castells, 2011).

Concretely, we explore perceptions of value in Commons-Based Peer Production (CBPP). This term, originally coined by Benkler (2002), refers to an emergent model of socio-economic production in which groups of individuals cooperate to produce shared resources without a traditional hierarchical organization (Benkler, 2006). There are multiple, well-known examples of this phenomenon, such as Wikipedia, a project to collaboratively write a free encyclopedia; OpenStreetMap, a project to create free/libre maps of the World; or Free/Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) projects, such as the operating system GNU/Linux or the browser Firefox. Research carried out drawing on crowdsourcing techniques (Fuster-Morell et al., 2016a) found examples of the broad diversity of areas in which collaborative work on the commons is present. This includes citizen science, urban commons, peer funding and open design.

The existence of value beyond measure (Hardt and Negri, 2001) poses a great challenge for researchers. The study of such perceptions in specific contexts, such as CBPP communities, provides us, however, with ways to escape the hegemonic price system to determine value (Pazaitis et al., 2017). In other words, if as argued by Graeber (2001), the capitalist mode of production has transformed the perceptions of value, defining meaningful actions within the broader capitalist social totality, then CBPP provides us with spaces in which to understand such actions as meaningful or not with respect to the internal social totality of these communities themselves. In this article, we develop from Graeber's (2001) perspective of value as a coordination mechanism, which in the case of CBPP is contextualized as the actions which emerge as part of meaningful contribution activities to the participants of such communities and, to a certain extent in some cases, find a reflection in the artifacts that these communities employ to collaborate. We agree, in this respect, with Wittel's (2013) argument on contribution being a key notion around which the framing of perceptions of value operate in the context of CBPP. As a result, we decided to carry out an exploration of what activities are considered contributions or not in CBPP communities, with the aim of shedding light on the perceptions of value in these communities.

With this aim, we investigate notions of contribution in CBPP, posing the question: what types of activities are perceived and valued as contributions in Commons-Based Peer Production and how are they recorded in the tools employed for coordination?

We explore notions of contribution in a large and complex case of CBPP: Drupal. Drupal is a FLOSS content management framework for the development of web applications that was released in 2001. The Drupal project currently powers more than 1.9% of websites worldwide1. The Drupal community has experienced significant growth over the years: there are currently2 more than 1.3 million people registered on the main collaboration platform (Drupal.org, 2017): www.drupal.org. Thus, the study of activities considered as contributions by community members becomes especially relevant in a complex and large case of CBPP, such as the Drupal community. Drupal has been described as “code-centric” in the literature (Zilouchian-Moghaddam et al., 2011; Sims, 2013). Namely, the Drupal community possesses a shared belief that the most valuable type of contribution by participants is source code: the sets of computer instructions which dictate how the Drupal software works. This “code-centrism” is also illustrated by the well-known Drupal motto: “Talk is silver, code is gold3” which is not uncommon in FLOSS communities. In sum, through the exploration of a complex and “code-centric” case, this study aims to unveil perceptions of contribution in peer production which would be less visible in smaller and simpler communities.

Our contribution is two-fold: firstly by broadening our understanding of the notions of contribution in the study of CBPP, providing a set of categories which emerged from our empirical analysis and which highlight activities not widely studied due to their traditional lack of visibility. Having identified these categories, we explore the relevance of activities which have remained less visible. Secondly, by drawing on the previously identified categories, we explore the recording of these forms of contribution in the main platforms employed for collaboration, showing an uneven representation of contribution activities. This analysis of the degree of representation of value attached to meaningful collaborations contributes by following previous calls on CBPP (e.g., De Filippi and Hassan, 2015; Pazaitis et al., 2017) and FLOSS (Carillo et al., 2014) studies to explore the systems of value of CBPP communities in order to further our understanding of how to systematize them into the technological artifacts which support collaboration, with an awareness of the communitarian context.

Conceptual Background

The concept of contribution in FLOSS literature has been widely employed in studies, but mainly in reference to activities related to source code. This can be understood as a form of “code-centrism”: reducing the conceptualization of participation and performance in FLOSS projects to the understanding of the activities surrounding the development of source code (Carillo et al., 2014, p. 3276). This is despite, as we shall see, the diversity of activities carried out in FLOSS communities, such as the organization of events, mentoring and training practices, and the creation of documentation and translations. Krogh and Von Hippel's (2006) literature review on FLOSS shows how studies that include the notion of contribution have principally examined the development of source code as the main type of contribution. This can be observed, for example, in studies focused on motivations to contribute (e.g., Bergquist and Ljungberg, 2001; Ghosh et al., 2002; Lerner and Tirole, 2002; Lakhani and Wolf, 2003; Stenborg, 2004); as well as in those focused on the relationship between organization and contribution (e.g., Dempsey et al., 2002; Koch and Schneider, 2002; Franck and Jungwirth, 2003; Grewal et al., 2006; MacCormack et al., 2006). Another illustration of this “code-centrism” in research on FLOSS can be found in the literature review of Crowston et al. (2012), in which they developed a framework based on an inputs-mediators-outputs-inputs model4 (Ilgen et al., 2005) to review 135 papers. In the case of inputs, most of the literature related to individual participation considers source code related activities (e.g., Luthiger, 2005; Robles et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2006; Fershtman and Gandal, 2007), or more recently between governance and authoritative structures associated with the management of such contributions (Shaikh and Henfridsson, 2017), as well as in the development of theory of how such forms of collaboration are organized (e.g., Howison and Crowston, 2014). A similar “code-centric” character can be observed with regard to outputs, for example regarding FLOSS team performance (e.g., Bezroukov, 1999; Samoladas et al., 2004; de Joode and Egyedi, 2005; Gyimothy et al., 2005). This issue is not, however, exclusive to FLOSS. Jemielniak (2014, p. 39–41) describes an analogous phenomenon in Wikipedia (“editcountitis”) around the number of edits as a major measure to evaluate participants' contributions, in spite of an awareness of its reductionism. In other words, a similar “object-centric” character, in which the objects are digital commons, such as articles and maps, can be found regarding the notions of contribution with respect to CBPP communities. For example, the writing of articles in Wikipedia (e.g., Kittur et al., 2007; Kostakis, 2010; Crowston et al., 2013; Jemielniak, 2014; Matei and Bruno, 2015) or the editing of maps in OpenStreetMap (e.g., Haklay et al., 2010; Neis and Zipf, 2012).

With the aim of questioning our understanding of the notion of contribution in the study of peer production beyond the most traditional “object-centric” conceptions, we carried out an analysis of these perceptions. We framed our analysis drawing on the three layer system of value for CBPP communities developed by Pazaitis et al. (2017). Concretely we explored the (1) production of value and the (2) record of value. The first layer refers to the modality of production: what particular actions are rationalized as meaningful contributions according to the communitarian needs? In this respect, we queried the notion of contribution, framing it as a set of meanings which are constantly evolving through negotiation among community members according to their internal logics of value. The second layer relates to the tools employed to record these forms of value. For this, we carried out an analysis of the previously identified activities considered contributions, showing a lack of visibility in the collaboration platforms of some despite their relevance for the sustainability of the community. The third layer, (3) actualization of value (Pazaitis et al., 2017), concerns the rationalization of such meaningful actions within the logic of external economic systems. For example, through monetization. Since our research question focused on internal production, perception and recording of value, Fuster-Morell et al.'s (2016b) conceptualization of internal systems of recognition and rewarding of value creation in peer production, meant we excluded this last outer layer5 from our analysis.

Next, we describe the qualitative research design and methods employed in order to further our understanding of the subjectivities of how such forms of value are perceived and how they are recorded in the tools employed for collaboration.

Materials and Methods

This section details the study's research methodology; firstly, the principal author describes the approach and his position as a researcher, then details his data collection methods.

Ethnographic Approach

From 2013 to 2016 the first author collected and generated the materials employed in this article through participant observation in the Drupal community.

We selected an ethnographic approach in order to highlight the understanding of perceptions of value from the point of view of the participants. This allowed us to access participants' interpretations, experiences, and perspectives of intangible contributions which have been inaccessible through quantitative approaches. We decided to focus on a single, in-depth, complex “code-centric” case of CBPP in order to tackle over-generalization, over-simplification and neglect of complexity, issues which have previously been criticized (Viégas et al., 2007; Mateos-García and Steinmueller, 2008) in the study of CBPP. Choosing this approach was also a response to calls to understand how effective forms of collective action and self-organization are constructed in Commons-Based Peer Production (Txoler, 2014, p. 191).

On beginning this research, the first author was already an active member of the Drupal community with over three and a half years' experience. Therefore, his position as an ethnographer was as an insider researcher (Brannick and Coghlan, 2007), who had “natural access,” being an active participant in the community, in similar terms as other participants.

This experience enabled faster access to the community, including understanding of meanings surrounding software and the community, to more direct access to the field site and certain activities, such as the organization of events or the maintenance of official Drupal projects. It also eliminated the necessity to acquire the social and technical skills to avoid being considered a “newbie.”

This previous experience entailed the need, however, to address several challenges relevant to the dynamics of insider research, such as role duality and pre-understanding (Brannick and Coghlan, 2007). The first author dealt with such issues through a constant process of introspection and a continuous review of his roles as both researcher and Drupalista (a communitarian term used to refer to members of the Drupal community). For example, his previous experience within the Drupal community was primarily as a software developer and site builder. As a result, the first author would reflect on the need to widen his understanding from the perspectives of Drupalistas occupying different roles (see Appendix B in Supplementary Material), switching the focus during participant observation, documentary analysis or when selecting interviewees for semi-structured qualitative interviews on these perspectives.

Data Collection Methods

We followed a qualitative approach combining 3 years of participant observation, the analysis of an archive of 8,613 documents and 15 semi-structured interviews. We drew on purposive sampling (Palys, 2008), in which the collection and generation of data was led by questions and emergent themes to produce a relevant range of contexts that enabled the establishing of strategic and cross-contextual comparisons to build a well-founded argument (Mason, 2002). For example, the emergence of a theme regarding the representation of contribution activities in the collaboration platform led to an in-depth study of 73 user profiles until saturation was reached. Data collection and analysis was supported by the Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) NVivo 10, which facilitated tasks, such as coding or the development of models to refine such codes.

Participant Observation

Participant observation began in October 2013 and concluded in November 2016, throughout which field notes were systematically created. Due to the digital nature and global scope of the Drupal project, the great majority of the community's activities are carried out through online media. However, the large number of face-to-face events suggested that they also play an important role in the life of the community. For these reasons, the field site considered for this case study was the emergent set of online and offline spaces in which the day-to-day activities of the community unfold. Analogous approaches have previously been followed by similar studies in which both dimensions are relevant, as in Coleman's (2013) study of FLOSS communities and hacker culture. Concerning the online, the first author engaged in the numerous collaborative tasks that are regularly carried out in the Drupal community. Such tasks included engaging in discussion groups, writing code, maintaining and coordinating Drupal projects, creating documentation and conducting discussions via social networks and chat channels. Beyond “official” channels, various other online spaces emerged as relevant to this study. For example, communication with Drupalistas through WhatsApp and Telegram groups, in addition to other external platforms, such as Slack, StackExchange, and Meetup. The offline engagement also took diverse forms, including attending and participating in the organization of events, sprints focused on source code development, as well as presenting parts of this research at Drupal events of different scopes: local events, DrupalCamps (national/regional), and a DrupalCon (international) as a keynote speaker. In total, the first author carried out F2F participation at thirty-two events (see Appendix C in Supplementary Material). The majority of participant observation at local events was carried out in London, UK, and the surrounding areas, as well as active participation within the local Drupal community of Madrid, Spain.

Participant observation proved to be essential in gaining an in-depth understanding of Drupalistas' perceptions of value. This allowed the first author to identify and then experience which contributions were or were not considered valuable by the community. Furthermore, he gained firsthand knowledge of how these forms of value are embedded into the technical artifacts employed for collaboration within the community. This method was also beneficial in other ways; for example, it enabled the first author to build a rapport with key informants, which facilitated the evaluation of relevant materials in the documentary analysis.

Documentary Analysis

Defining an initial point of collection of relevant documents was required, given the large amount of information generated by a large community, such as Drupal. Software was developed to generate a live archive of Drupal Planet6, which contains Drupalistas' posts made within the community beyond “official channels.”

The data collection process yielded 8,613 documents from the Drupal Planet archive and, to help select their relevance, the first author conducted several further selection inspections. This process was regularly informed by participant observation. This resulted in a total of 586 documents being fully coded, comprising 6.8% of all of the documents collected. A summary of this data is presented in Appendix D in Supplementary Material.

Semi-structured Interviews

As well as hundreds of unstructured conversations carried out as part of the participant observation process, fifteen semi-structured qualitative interviews were carried out with key participants involved in organizational processes related to contribution activities (see Appendix E in Supplementary Material). These interviews provided rich qualitative data, furthering the understanding of Drupalistas' perceptions of value.

Ethical Considerations

The ethical principles described by the University of Surrey (Gallagher, 2013) were followed, as well as the recommendations from the Association of Internet Researchers (Markham and Buchanan, 2012). Drawing on these guidelines, we constantly reassessed so that the discovery of any new issues resulted in remedial action. These actions include anonymizing participants in field notes, in addition to the design of interview consent forms and requesting permission to use materials gathered outside of the public sphere (for example, conversations in Telegram). The use of data about any individual adhered to the UK's Data Protection Act7 (1998). The excerpts shown in the next sections show how long the Drupalista had had a drupal.org account, their main roles and gender.

Findings

“Object-Oriented” and “Community-Oriented” Contribution Activities

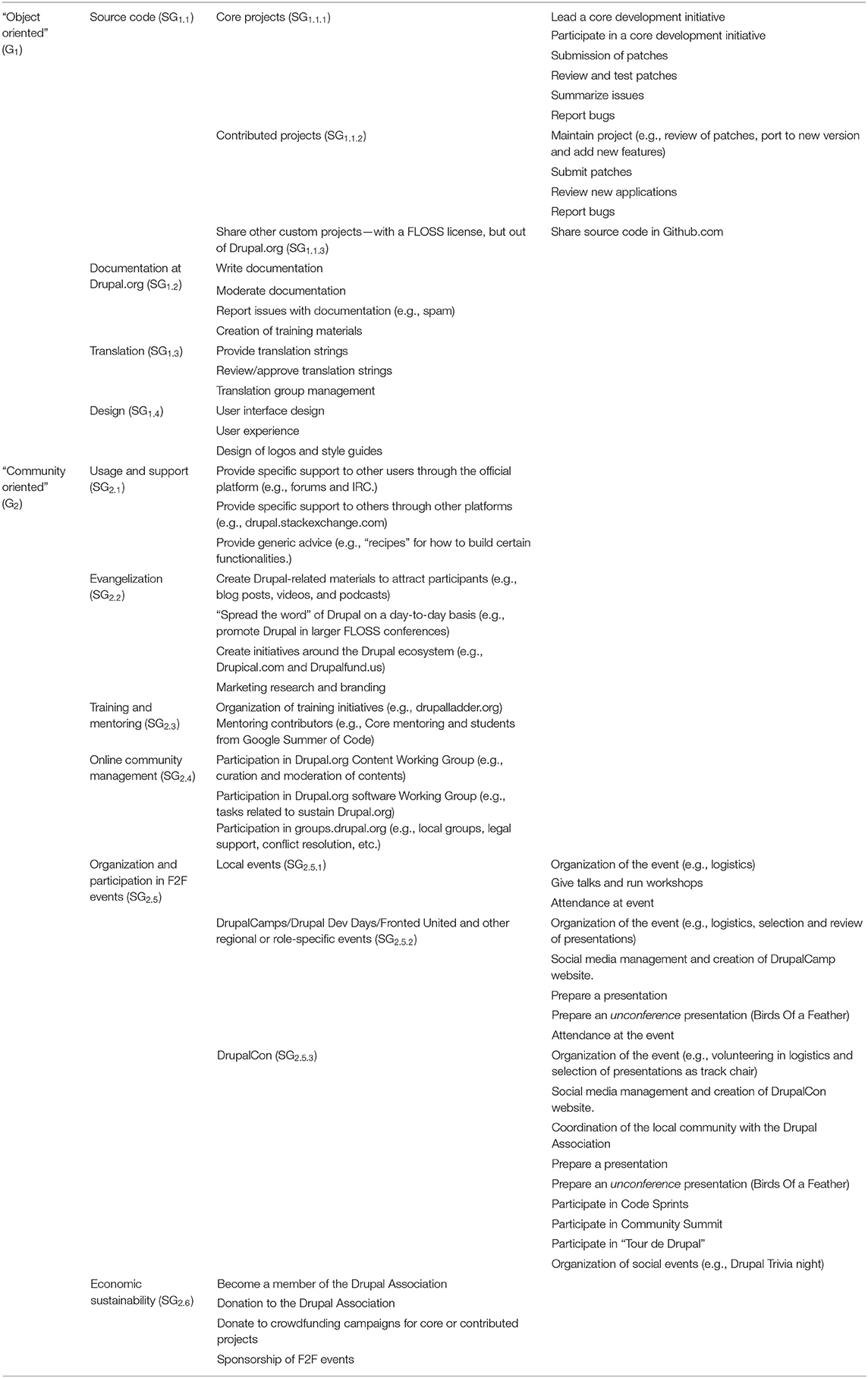

When studying what types of activities are perceived as contributions in the Drupal community, two main types of contribution activities emerged. The first was “object-oriented” contributions, encompassing all activities whose main focus of action are objects, typically digital commons, such as source code, documentation, and translations. The second category was “community-oriented” contributions, the focus of which is directed toward the community. Examples are the organization and participation in face-to-face events, activities related to supporting other users, and mentoring. Table 1 provides a summary of the contribution activities identified in this study.

The activities are firstly classified according to the main categories: “object-oriented” (G1) and “community-oriented” (G2). Contribution activities related to source code (SG1.1) are further classified into three subgroups: core (SG1.1.1), contributed (SG1.1.2), and FLOSS custom projects (SG1.1.3) not included in Drupal.org. The reason for this distinction is the significant differences found in the organizational aspects of the socio-technical systems that surround these contribution activities (Rozas and Huckle, 2021), despite the type of object being the same: source code. For example, the possibility of performing modifications in the digital commons for the core group is more formalized, typically harder to achieve, and more specialized. As a consequence, new contribution activities emerge and are considered valuable. For example, the “creation of summaries of the issues,” in which hundreds of comments are summarized, is perceived as a valuable contribution. This type of contribution is typically carried out by newer members to save core developers having to read the whole list of issues. It is encouraged as a way to “contribute to core,” whilst enabling the newest members to become familiar with the organizational processes and technicalities. The following excerpt, extracted from field notes taken when participating in a local event, illustrates how these activities are valued as contribution activities:

“[…] I joined then a Drupal Ladder8 session coordinated by Karen. […] Karen explained to us ways to contribute to core. One of them I was completely unaware of was summarizing the messages of the issues lists for the developers: ‘A good way to contribute initially is doing some issue summaries' and encouraged us to visit https://drupal.org/issue-summaries, in which we could find very detailed rules on how to do it. The idea is that you find and read a whole issue and, following certain templates and instructions, make a summary so the developer doesn't have to spend a lot of time reading all of the comments. […]”

Extracted from full field notes during the participant observation at a Drupal Coding Sprint in London on 31st May 2014.

Within the “community-oriented” group (G2), a distinction is made with regard to contribution activities related to the organization and participation in face-to-face events (SG2.5). In this case, they are differentiated by their scope. The second of these subgroups (SG2.5.2) includes regional, national and role-specific events. This is because the dynamics, organizational processes and identified contribution activities in these events are similar. As in the case of the subgroup SG1.1, the main difference between SG2.5.1, SG2.5.2 and SG2.5.3 is with regard to the level of formalization and the ease of participation in their organization. For example, DrupalCon activities, largely organized by the most formal institution within the Drupal community, the Drupal Association, are at the formal end of the spectrum. As in the case of the subgroups of G1, organizational processes with a higher degree of complexity in G2 involve significant organizational changes overtime, including more clearly defined roles (Rozas and Huckle, 2021) and the emergence and perception of new activities which are valued as contributions, such as the peer reviewing and selection of presentations carried out by “track chairs,” as I10 explains:

“[…] I can go back as far as Chicago [2011]. […] I think the biggest change was over the process. People submit proposals on the website, which are public, so everyone can see the proposals. Then, track chairs can go through them, and decide. There are two or three chairs for each track. […] DrupalCon is a very different beast than it used to be. Where… you know, at SunnyVale [2007] we got all fit in the outside lunch patio at Yahoo. […] That's not a conference, that is a code sprint… you know, plus occasional presentations. So, it has definitely grown dramatically, and so there's a very different feel now.”

Developer and system architect, M, 11 years.

While, as previously discussed, “object-oriented” activities have been widely employed in studies drawing on the notion of contribution, those whose main focus of action is the community have received less attention. This is despite the relevance of these activities to sustain the community. A comment from I3 illustrates, for example, the relevance of activities, such as the participation in and organization of local face-to-face events for the health of the community:

“[…] organizing talks, meetups or just hanging out with Drupalistas to drink some beers and have a talk, are also very important activities, and very positive for the community.”

System architect and developer, M, 8 years. Original reply in Spanish.

Furthermore, Drupalistas explain and are aware of the differences with respect to the internal logics of value when compared with “object-oriented” activities, such as contributing source code. The following excerpt from field notes illustrates how some Drupalistas identify the participation in and organization of face-to-face events as contributions and the awareness of the perception of differences in value:

“[…] She explained to me that we, as a community, are not aware sometimes of the relevance that other activities have, such as the organization of events like this one [referring to the DrupalCamp] or the ‘Tour de Drupal9’. She thought that organizing and attending events like this one are definitely types of contribution, but they aren't so popular. She explained to me that we tend to think a lot about contributing code, especially to core, but she highlighted: ‘thanks to things like this [referring to the F2F event], the community is very healthy’.”

Designer and front-end developer, F, 5 years. Extracted from full field notes during the participant observation at DrupalCamp North East 2014.

Participation in face-to-face events as those mentioned in the previous excerpt, was commonly described as a way to humanize the community. Drupal is regarded not just as “a piece of software” anymore, but rather a community in which Drupalistas become commoners through “commoning” (Linebaugh, 2008). By affecting the emotional experiences of Drupalistas these contribution activities play a relevant role in the sustainability of the community, and increase the commitment to participate in the community. The following excerpt from I2, a newcomer, while reflecting on how attendance at local meetings changed his emotional experiences, illustrates this:

“[…] indeed, the fact of attending these meetups was really good. Because you realize there are people behind the source code, right? There are people behind the modules. And you meet people that can tell you a kind of personal story. […] And then, it stops being something anonymous, it becomes something yours.”

Themer and site builder, M, 1 year. Original reply in Spanish.

Another common outcome of “community-oriented” activities was help with overcoming barriers, and increasing the will to contribute, providing opportunities to participate in the community to those who are not technical and, thus, facilitating the diversity of participants beyond the most technical profiles. The following excerpt from a new member after attending a DrupalCamp for the first time illustrates this type of outcome:

“Walking in the door, I didn't feel like a part of the community. I wasn't sure where I fit in since I wasn't a developer, designer, or vendor. I wasn't sure what to expect at the NYC Camp […]. [After participating in the event] I never got a sense of feeling inferior for lack of experience or an inability to code. We had really engaging and valuable sessions. […] The experience came together for me during several discussions both in the sessions and on the side. Drupal is about community. The community builds, maintains, advocates, cautions, and develops the platform. […] For me, this triggered the idea of giving back to the community in a way that made sense for us.”

Content editor and manager, M, 1 year. Retrieved 22nd May 2014, from https://assoc.drupal.org/content/guest-post-why-olympus-gives-back-drupal under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

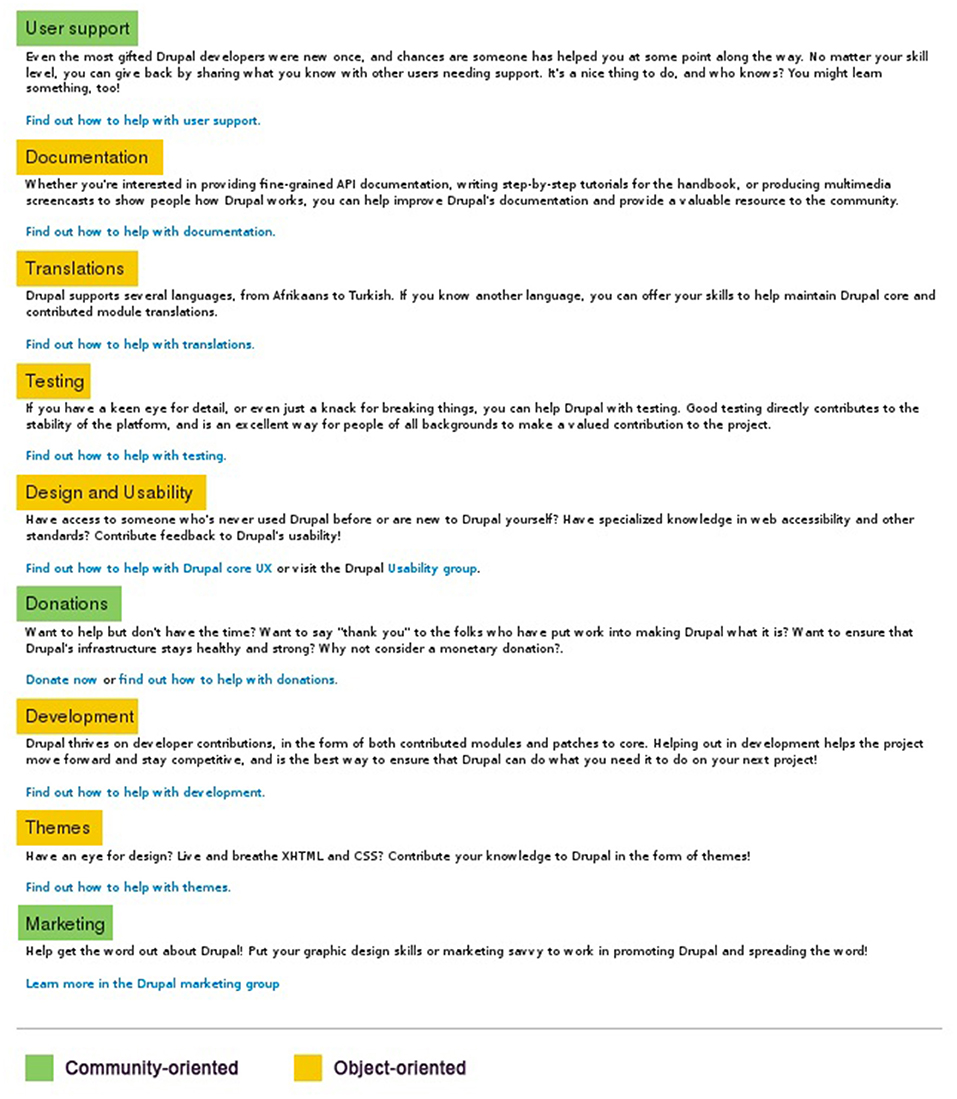

These perceptions of what can be considered contribution contrast with those represented in the main collaboration platform. In other words, the rationalization of certain activities as meaningful contributions according to the Drupal community's needs—the first interrelated layer of value conceptualized by Pazaitis et al. (2017)—mismatch with the systematization of the assessment of such activities to track and record such forms of value in the main collaboration platform—the second interrelated layer of value conceptualized by Pazaitis et al. (2017). This mismatch is illustrated, for example, in the main pages that explain how individuals could contribute to Drupal, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. List of contribution activities in the main site “Get involved”: yellow depicts “object-oriented” activities and green “community-oriented” activities. Retrieved 22nd October 2014 and modified 10th June 2019, from https://drupal.org/contribute, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

On the one hand, encouragement and explanations of how to contribute to “object-oriented” activities (G1) are represented on the “Get Involved” page (Drupal.org, 2014d) relating to contribution in the main collaboration platform. Some of them are differentiated and highlighted. For example, in the case of contribution activities related to source code (SG1.1), there is an explicit distinction between “theming” and “backend” development.

On the other hand, “community-oriented” activities (G1) are only partially reflected in user support, donations and marketing on the main page (see Figure 1). References can be found when a deeper navigation into the platform is made through less relevant and less visible spaces. For example, a sub-page named “Contribute to Drupal.org” (Drupal.org, 2014a), provides information about contributions related to the main collaboration platform itself. This area also refers to some of the “online community management” (SG2.4) contributions. However, no explicit mention is made of the “organization and participation in face-to-face events” (SG2.5) in primary and secondary levels of the platform. The first reference to events can be found only after navigating through more hidden and tertiary links in the “General Resources” section to the Drupal Groups (Drupal.org, 2014c), which allow participants to start browsing by geographical location after several steps.

Overall, this analysis shows a need to widen our understanding of contribution activities beyond the traditional view of source code or other “object-oriented” activities, and the existence of differences with regard to the internal perceived value. Additionally, evidence is provided with regard to the lack of visibility of “community-oriented” activities in the main collaboration platform. To further understanding of this lack of visibility, the next section explores the representation of the identified contribution activities at an individual level, by studying user profiles.

Representation of Contribution Activities in User Profiles

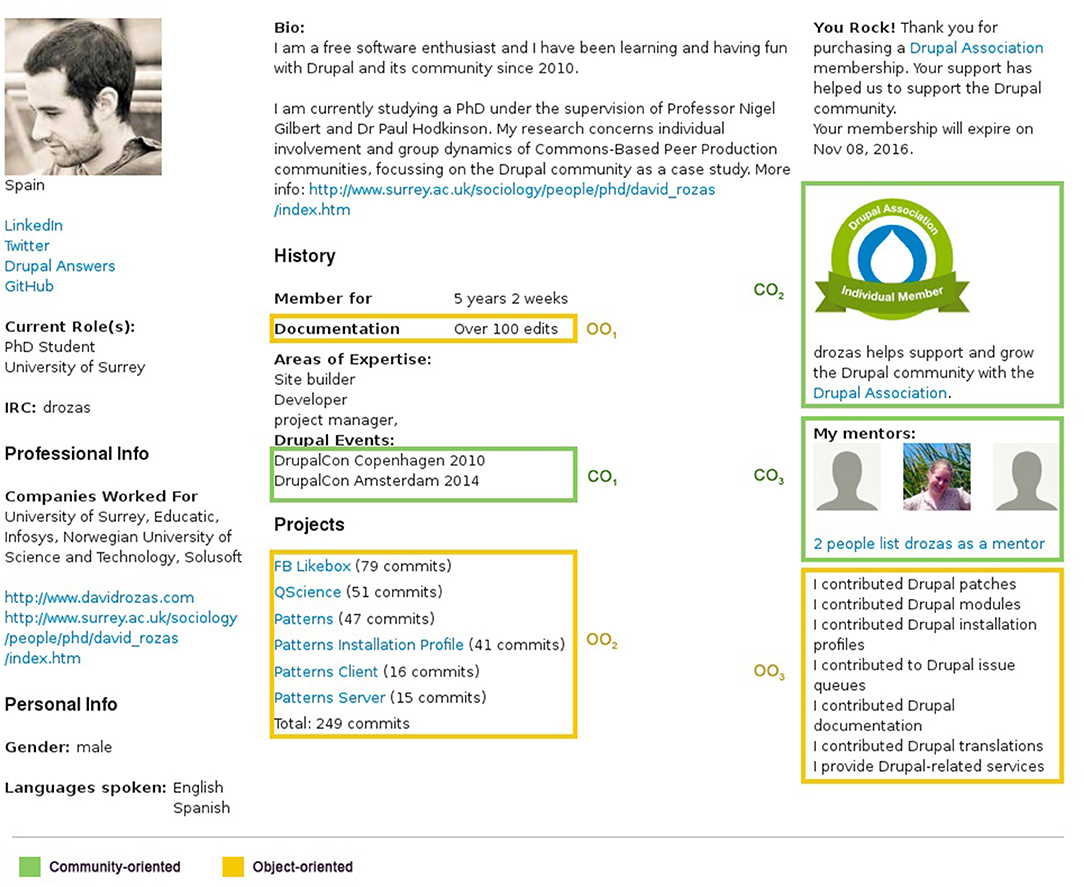

User profiles have been previously identified as a key element in the generation of other participants' perceptions in FLOSS communities (Marlow et al., 2013). They are an important source of public references, used to evaluate the reputation of other members, and play a significant role in the process of status attainment in FLOSS communities (Stewart, 2005). In Drupal, there are several ways to access profiles. The main way, however, is the main profile page at Drupal.org. Figure 2 below shows the first author's profile on the site, depicting his tracked and recorded forms of contribution since 2010.

Figure 2. Overview of the first author's profile at Drupal.org: yellow depicts “object-oriented” activities and green “community-oriented” activities. Numbers are employed to refer to specific indicators in this section. Retrieved 2nd April 2015, from https://www.drupal.org/u/drozas and modified 10th June 2019, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

The importance of user profiles at Drupal.org was confirmed in interviews, observation and documentary analysis. I4, a Drupal front-end developer, highlights the importance of user profiles when hiring services from other Drupalistas:

“[…] We always go and check to see if they've got a Drupal.org account and check what contributions they've made before, and whatever. It kind of gives you the sense of, you know, who you're gonna be dealing with.”

Developer and project manager, M, 11 years.

Another example is that the representation of certain contribution activities in the profile can be a motivator:

“[..] She got her first patch committed to core. She was very enthusiastically showing her friend her profile at Drupal.org because in the ‘Projects’ section appears ‘Drupal core (1 commit)’.”

Manager, content editor and site builder, F, 2 years. Extracted from full field notes during the participant observation at DrupalCon Amsterdam 2014.

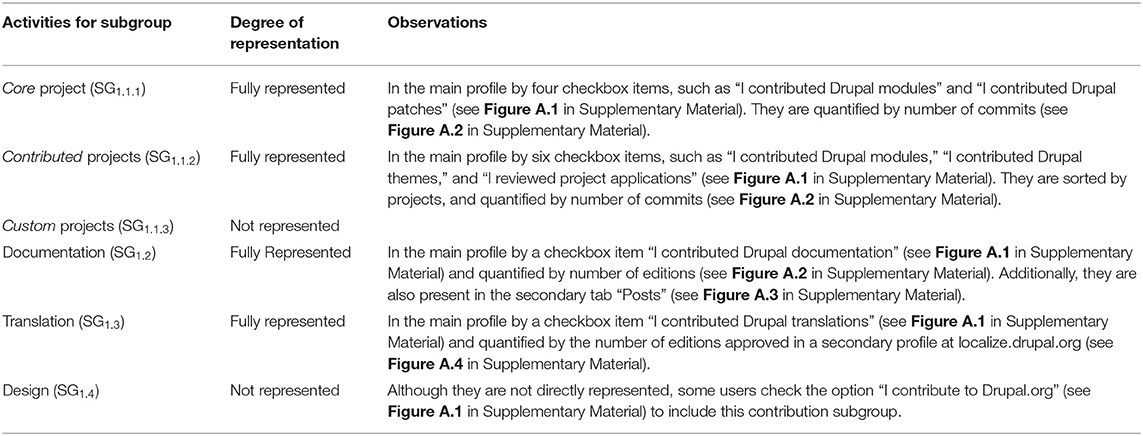

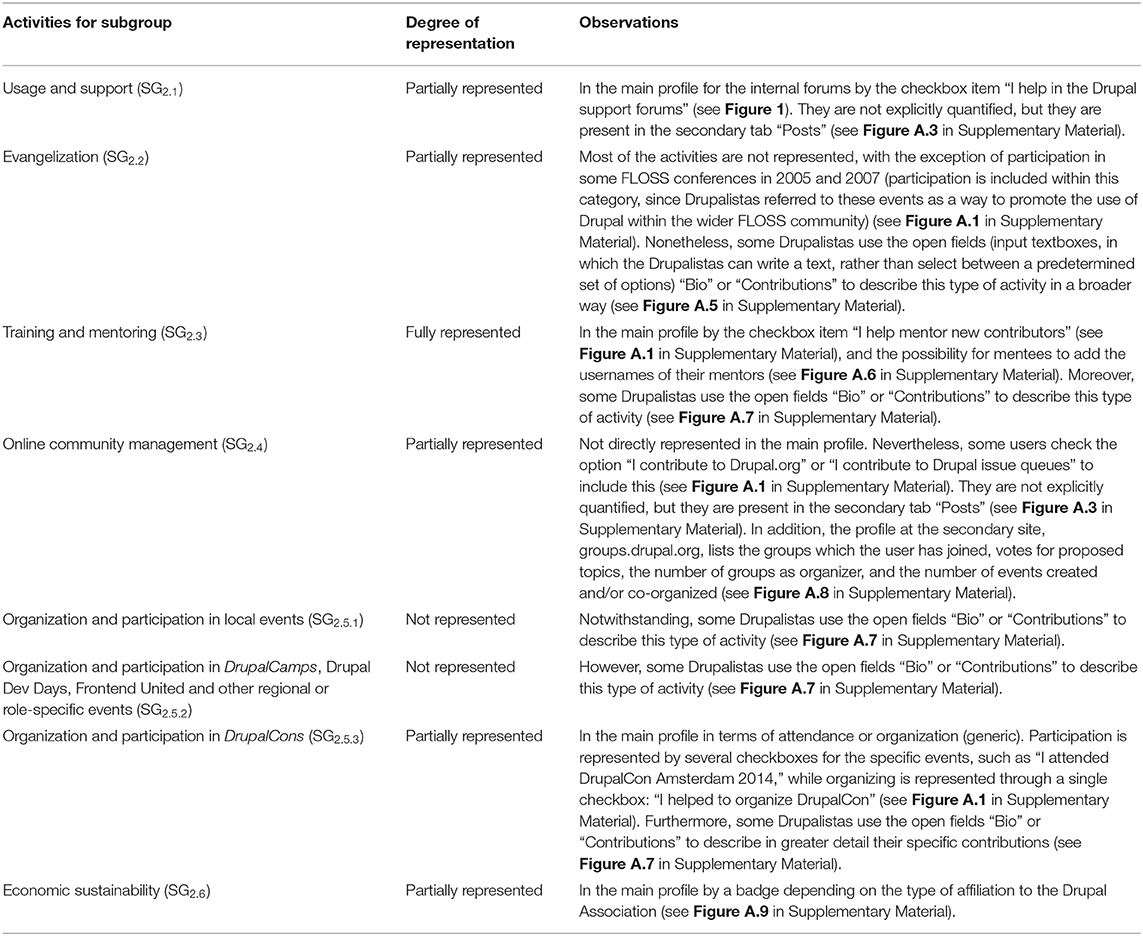

Tables 2, 3 present a summary of the analysis carried out to study how the identified activities are represented on the main collaboration platform in individual profiles for the “object-oriented” and “community-oriented” groups, respectively. The analysis was carried out in all platforms and sub-platforms (e.g., https://groups.drupal.org, https://localize.drupal.org, or http://assoc.drupal.org) that form part of the main platform of collaboration. The nomenclature for the subgroups is the same as previously employed in Table 1. For those which are fully or partially represented, the items employed in user profiles and the quantification of the activities, if any, are detailed in the column for observations. Figures illustrating these items are also referred to in this column, and presented subsequently in Appendix A in Supplementary Material.

The analysis shows an uneven representation of contribution activities in user profiles at Drupal.org. Overall, this affects the activities within the “community-oriented” category (G2) far more than those in the “object-oriented” category (G1). The exceptions for G1 are “design” (SG1.4) and “custom projects” (SG1.1.3). In the case of the former, it was found that, as we shall see with “community-oriented” activities, Drupalistas use generic open text fields to overcome these limitations. For the case of the latter, the lack of representation can be explained on the basis of the lack of perceived value of code outside the main platform of collaboration. These projects are not subject to community peer-reviewing processes and are commonly disregarded, as I10 explains:

“[…] unlike other projects, Drupal.org is the central nexus. If your module isn't on Drupal.org, a lot of people won't touch it, myself included.”

Developer and system architect, M, 11 years.

However, in general terms these activities are commonly represented and even quantified and automatically included in the platform with no need for additional intervention by the participant, as depicted in Figure 2. The number of commits in core and contributed projects, the number of editions in the documentation, depicted in areas OO1 and OO2 of Figure 2, or the number of approved translations shown in Figure A.4 in Supplementary Material are indicators of this.

The most prominent lack of representation is found within the “community-oriented” category (G2) and it is especially significant for contribution activities related to the organization of and participation in local events (SG2.5.1), DrupalCamps and role-oriented events (SG2.5.2). In these cases a prominent use of open text fields by Drupalistas was found, as illustrated in Figure A.7 in Supplementary Material. This can be explained as a way in which Drupalistas try to overcome these limitations, providing an indicator of the unfulfilled need to have these traditionally less visible contributions publicly acknowledged, as shown in the following excerpt (full version in Figure A.7 in Supplementary Material) of the profile of this Drupalista:

“[…] I am a freelance Drupal Site Builder and Front End Developer […] I have been very involved in training and mentoring web developers, particularly young people, getting them into careers specializing in Drupal. I have helped to support the Drupal community by speaking at camps and conferences […]Drupal community

- Founding and organizing Drupal West London

- Mentoring apprentices and creating open source curriculum for learning Drupal-Open Drupal

- Speaking at DrupalCamps on Drupal commerce, Responsive web design 6 and Open Drupal: http://chandeepkhosa.com/?q=speaker[…]”

Frontend developer and site builder, M, 7 years. Excerpt from Figure A.7 in Supplementary Material.

The clearest exception found regarding the lack of representation of community-oriented activities was the indicator of mentorships, depicted in area CO3 of Figure 2. This indicator allows recognition to be given to Drupalistas as mentors and, reciprocally, users can indicate, on their profile, who has mentored them. This goes in line with a more general need of the community to find indicators which visibilize “community-oriented” activities, as indicated by the emergence of initiatives (Drupal.org, 2014b; Nordin, 2014) to improve how activities are represented in user profiles at Drupal.org, to “[…] go beyond code creation activity and into more community-oriented contribution stuff, since that's also a huge part of what makes Drupal healthy.” This example of peer-to-peer mentorship references indicates the path and will to follow in that direction of recognition of “community-oriented” contributions.

In sum, this analysis of user profiles provides, firstly, a descriptive account of how the contribution activities identified in the previous subsection are represented in different user profiles on the main collaboration platform; but most importantly the analysis provides empirical evidence of the uneven representation of certain contribution activities, affecting especially those identified as “community-oriented.” It has been seen, however, that “community-oriented” activities, such as these are understood as a type of contribution and play a key role in the sustainability of the community, as shown in the first section; but in spite of this relevance to fostering collaboration, they are commonly not recorded and unequally represented in the main collaboration platform, as seen in this last section.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Our research explored perceptions of value and how such forms of value are reflected in the platforms employed for coordinating a large case of CBPP. We provide two main contributions for the literature on FLOSS and, more widely, for the literature on CBPP.

Firstly, our exploration of the rationalization of certain activities as meaningful contributions according to the internal logics of value shows the need to broaden our understanding of valued contributions. We provide evidence of the perception of identified “community-oriented” forms of contribution, how they are valued as well as their relevance for the sustainability of the community.

Secondly, through an analysis of the representation in the main collaboration platform, we contribute empirical evidence of the uneven representation of some of these contribution activities, affecting especially those identified as “community-oriented.” Next, we detail each contribution and provide implications for future research.

Talk Is Silver, Code Is Gold? Beyond “Code-Centrism” in FLOSS and “Object-Centrism” in CBPP

A few studies on the level of commitment in FLOSS moved the focus from code contribution to explore communication contributions (Crowston and Howison, 2006) and support contributions (Lakhani and Von Hippel, 2004). Furthermore, Coleman's (2013) work on FLOSS and hacker culture showed a relationship between face-to-face events and the political, moral and affective dimensions of FLOSS communities. “Object-centrism” is, however, still commonly present in the studies of FLOSS and, more widely, in studies of CBPP communities (e.g., Kittur et al., 2007; Haklay et al., 2010; Neis and Zipf, 2012; Crowston et al., 2013). In spite of having received less attention in the literature, we show how “community-oriented” contribution activities, such as the organization of events, are indeed understood and valued as contributions. Furthermore, we show how they are fundamental for the sustainability of the community. A modest hackathon organized in a small venue, for example, may not be at first sight perceived as the most relevant way to contribute to the global project. Nevertheless, as shown in this study, the interactions which occur in these spaces are key to increasing collaboration beyond solitary endeavors when contributing (Chełkowski et al., 2016, p. 16), the commitment to participate in the community, humanizing it and increasing the diversity of participants.

The issue identified in this research is not particular to this case study, nor is it specific to the time period (2013–2016) in which this study was carried out. Overall, there is a lack of common ways to measure intangible forms of value as those identified in this study as a result of a “value crisis” (Arvidsson and Peitersen, 2013), which has also been described in other CBPP communities (e.g., Jemielniak, 2014, p. 39–40; Chełkowski et al., 2016, p. 13–14). In this respect, the implications for research are two-fold. Firstly, on the need to consider these less visible forms of value when carrying out studies of such communities. Secondly, on understanding its dynamic nature since, as we have seen, new contribution activities may emerge and be considered valuable over time according to the internal logics of value.

Further work could explore forms of value, such as those which emerged from this case study in a wider range of CBPP communities. Furthermore, studies to compare “object-centric” contributions, such as the numerous studies on the number of code commits in FLOSS referred to in section Conceptual Background, with respect to “community-centric” contributions could be carried out. A mixed-methods approach triangulating qualitative data, as from this study, with quantitative data, for example carrying out a Social Network Analysis of the identified networks of mentorship, would offer opportunities to further our understanding of the development and changes experienced over time in the acknowledgment and distribution of value in CBPP communities. The quantitative side could be undertaken, for example, by the study of the networks and the changes experienced over time of “community-oriented” contributions, which could also be compared with networks of “object-oriented” contributions. In addition, this approach would offer the possibility to carry out comparative studies of the characteristics, such as gender, age, or location, of the participants who perform these activities.

In sum, we hope the questioning of our understanding of contribution in FLOSS and CBPP carried out in this research will help researchers to frame studies on the forms of value present in such communities from new perspectives.

Recording and Representation of Value in Collaboration Platforms

We extend FLOSS and CBPP literature by providing a descriptive account of how the contribution activities identified in the previous subsection are represented on different user profiles on the main collaboration platform; but most importantly the analysis provides empirical evidence of the uneven representation of certain contribution activities, affecting especially those identified as “community-oriented.” Hence, not only “community-oriented” activities, such as these are understood as a type of contribution and play a key role in the sustainability of the community, as previously discussed; but they are commonly not recorded and unequally represented in the main collaboration platform. In other words, by drawing on the three layer system of value for CBPP communities developed by Pazaitis et al. (2017), we found a mismatch between the (1) production of value and the (2) record of value. This unequal representation was found at an “official” level, such as in the main sections of the platform dedicated to contribution, as well as at an individual level, such as in the study of user profiles.

Overall, “community-oriented” contributions are poorly represented in the main collaboration platform as compared to “object-oriented” ones. This disjunction between the relevance and lack of visibility of “community-oriented” contributions casts doubt on the “object-centric” belief traditionally present in CBPP communities, illustrated by the motto “Talk is silver, code is gold” for the specific case of FLOSS communities.

The lack of representation of “community-oriented” activities found in this study cannot be understood as due solely to socio-cultural reasons. The “code-centric” character of the community offers only a partial explanation. Technical limitations also have a major impact. For example, while certain activities are easily quantifiable (e.g., the number of commits of source code, or the number of edits of wiki pages), others are more difficult to quantify or represent in concise, useful ways. As we have seen, the issue is not exclusive to Drupal and other FLOSS communities. For example, Jemielniak (2014) identifies the number of edits in Wikipedia as “one of the few quantified measures of user-contribution value […] Everybody on Wikipedia knows that […] is flawed […], but in the absence of other quantified indicators, it is used nevertheless” (p. 40). In other words, the main challenge resides in the difficulty to provide indicators to acknowledge and aggregate the value of some types of contribution, or to find interoperable ways to have this value recognized by other communities; an issue that is under exploration by researchers (De Filippi and Hassan, 2015) as well as CBPP communities10 themselves. The Drupal community is also attempting to find suitable indicators, as illustrated when discussing peer-to-peer mentorship references.

Thus, a broader understanding of the notion of contribution also has implications for the provision of indicators that acknowledge, aggregate and incorporate these forms of value in the technical artifacts employed to support the organization of peer production. This aspect is particularly relevant for large and global CBPP communities as they scale up since, due to their growth and their global character, the generation of perceptions between unknown members becomes more frequent in these communities, and the role of the platforms employed to support their self-organization (e.g., through the creation of trust) becomes more crucial. In this respect, the potential of blockchain technologies to facilitate the dynamics of social sharing, as proposed by Pazaitis et al. (2017), offers the possibility to experiment with new systems of value in which to record the perception of such actions as meaningful or not with respect to the internal social totality of these communities themselves (Graeber, 2001). In other words, these decentralized technologies are offering novel opportunities (Rozas et al., 2021) for the development of open and transparent indicators expressing the different dimensions of value in CBPP, including those which have remained less visible, and their impact could lead to the emergence of innovative ways for commoners to coordinate, scale up self-governance or share these forms of value amongst different CBPP communities in interoperable ways.

Future research should investigate the indicators of value and the various models of distribution of value which are emerging in CBPP, such as those identified in this case study. Overall, this broader understanding is also relevant for more technical fields, such as Computer Science, as well as research initiatives aiming to develop platforms to support and foster the development of CBPP. For example, a high degree of flexibility is expected for the design of mechanisms that indicate forms of value in the collaboration platforms employed by these communities. In other words, rather than creating tools which impose “one-fits-all” indicators, such as “likes,” a broader understanding of contribution in CBPP implies, for these platforms, the need to offer mechanisms that enable communities to define these indicators dynamically, allowing them to reflect the results of their processes of negotiation of what is considered valuable.

In sum, there remains a need to further our understanding of the provision of indicators which measure and aggregate less visible forms of value, as well as how to incorporate them into the technical artifacts employed to support the organization of CBPP. We aim for the identification and evidence of the lack of visibility of “community-oriented” activities presented in this study to contribute to furthering our understanding on how to recognize and incorporate such forms of value.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://davidrozas.cc/lab/drupal_planet_archive.php.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was not provided for this study on human participants because in order to ensure this study fulfills the ethical principles described by the University of Surrey, an evaluation was undertaken as to whether this study should be referred to the University Ethical Committee to seek an ethical review. This research did not fall into any of the categories described by the Ethical Principles Procedures for Teaching and Research (http://www.surrey.ac.uk/fhms/Ethics%20Committee/ethicsfiles/Ethical_Principles_and_Procedures.pdf), and hence, it was concluded that it was unnecessary. Nevertheless, the study was carried out considering the recommendations at all times. For example, when the processing of personal data required the personal consent of the participant, such as in the case of qualitative interviews, the process was carried out according to the suggested Data Protection Act (1998). In addition to the guidelines provided by the University of Surrey, the Recommendations from the Association of Internet Researchers Ethics Working Committee (http://aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf) were evaluated and constantly considered during the course of this study. This document provides a set of guidelines to facilitate the process of ethical assessment in the field of Internet studies, as well as a set of common questions to help the researcher to raise ethical considerations. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

DR coordinated the elaboration of the paper and participated in all the phases, including data collection, conceptualization, literature review, structuration, analysis, and overall writing of the article. NG, PH, and SH discussed the paper's general approach, reviewed the paper, and contributed to parts of it across all sections. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the project P2P Models (https://p2pmodels.eu) funded by the European Research Council ERC-2017-STG (grant no.: 759207) and by the project Chain Community funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (grant no.: RTI2018-096820-A-100).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The content of this manuscript has been published as part of the thesis of DR (Rozas, 2017). We thank the Drupal community, especially to all of the Drupalistas with whom the first author met; their collaboration made this research possible. We were grateful to the editor and two reviewers for their constructive feedback on our manuscript. Finally, we would like to thank Tabitha Whittall for her help in copy-editing and proofreading this article.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2021.618207/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Usage statistics and market share of Drupal—https://w3techs.com/technologies/details/cm-drupal/all/all, last accessed on 5th June 2019. This percentage includes well-known websites with complex architectures and high loads of traffic, such as mtv.co.uk and economist.com.

2. ^See “Getting involved”—https://www.drupal.org/getting-involved, last accessed on 5th June 2019.

3. ^As illustrative examples, the motto can be found in relevant Drupal blogs such as that of the Drupal Association (2014), or the official blog of the largest Drupal business company Acquia.com (2014).

4. ^This refers to an extension of the earlier Input-Process-Output model (Hackman and Morris, 1975) that, among other differences, distinguishes emergent states from processes. Crowston et al. (2012) applied the inputs-mediators-outputs-inputs model characterizing, for example, FLOSS community members' characteristics as inputs, decision-making as processes, roles as emergent states, and team performance as outputs.

5. ^See Greenstein and Nagle (2014) and Robbins et al. (2018) for studies exploring the measuring of the economic impact of FLOSS. Exploring Apache as a case study, the former estimated the cost of replacing this FLOSS web server with proprietary software in the US between $2 and $12 billion (Greenstein and Nagle, 2014, p. 628). The latter estimated the cost of production of several FLOSS languages (R, Python, Julia, and Javascript) at more than $3 billion, based on 2017 prices (Robbins et al., 2018). More recent initiatives include the ongoing Open Source impact study, commissioned by the European Union, assessing the economic impact of FLOSS in Europe (see https://www.openforumeurope.org/open-source-impact-study/, last accessed on 18th February 2021).

6. ^The archive is available at http://davidrozas.cc/lab/drupal_planet_archive.php. Because Drupal Planet only retains posts for 16 weeks, tailored scripts generated that archive; the source code for which is under a FLOSS license and available at https://github.com/drozas/drupal_planet_archive.

7. ^See https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents, last accessed on 5th June 2019.

8. ^Drupal Ladder (http://www.drupalladder.org/) is a Drupal initiative to help people learn how to contribute to Drupal, including the organization of events and the collaborative creation of learning materials.

9. ^It refers to an initiative (https://groups.drupal.org/tour-de-drupal) of Drupalistas to cycle together over several days to the city in which the DrupalCon is held.

10. ^See, for example, the Open Value Network organizational framework for CBPP- http://valuenetwork.referata.com/wiki/Main_Page, last accessed on 7th June 2019.

References

Acquia.com (2014). Talk Is Silver, Code Is Gold: Acquia's Code Contributions to the Drupal Project. Available online at: http://www.acquia.com/blog/talk-silver-code-gold-acquias-code-contributions-drupal-project (accessed July 25, 2014).

Arvidsson, A., and Peitersen, N. (2013). Value Crisis. The Ethical Economy: Rebuilding Value After the Crisis. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Benkler, Y. (2002). Coase's penguin, or, linux and the nature of the firm. Yale Law J. 112, 369–446. doi: 10.2307/1562247

Benkler, Y. (2006). The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bergquist, M., and Ljungberg, J. (2001). The power of gifts: organizing social relationships in open source communities. Inform. Syst. J. 11, 305–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2575.2001.00111.x

Bezroukov, N. (1999). A second look at the Cathedral and the Bazaar. First Monday 4. doi: 10.5210/fm.v4i12.708

Brannick, T., and Coghlan, D. (2007). In defense of being native: the case for insider academic research. Organ. Res. Methods 10, 59–74. doi: 10.1177/1094428106289253

Carillo, K. D. A., Huff, S., and Chawner, B. (2014). “It's not only about writing code: an investigation of the notion of citizenship behaviors in the context of Free/Libre/Open source software communities,” in 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Waikoloa, HI: IEEE), 3276–3285. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2014.406

Chełkowski, T., Gloor, P., and Jemielniak, D. (2016). Inequalities in open source software development: analysis of contributor's commits in Apache software foundation projects. PLoS ONE 11:e0152976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152976

Coleman, G. (2013). Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking. New Jersey, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400845293

Crowston, K., and Howison, J. (2006). Hierarchy and centralization in free and open source software team communications. Knowl. Technol. Policy 18, 65–85. doi: 10.1007/s12130-006-1004-8

Crowston, K., Jullien, N., and Ortega, F. (2013). “Is wikipedia inefficient? Modelling effort and participation in wikipedia,” in 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Wailea, HI). doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2013.368

Crowston, K., Wei, K., Howison, J. and Wiggins, A. (2012). Free/Libre open-source software development: what we know and what we do not know. ACM Comput. Sur. 44:7. doi: 10.1145/2089125.2089127

De Filippi, P., and Hassan, S. (2015). “Measuring value in commons-based ecosystem: bridging the gap between the commons and the market,” in MoneyLab Reader, INC Reader, eds G. Lovink and N. Tkacz (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, University of Warwick), 74–91.

de Joode, R., and Egyedi, T. (2005). Handling variety: the tension between adaptability and interoperability of open source software. Comput. Standards Interfaces 28, 109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.csi.2004.12.004

Dempsey, B., Weiss, D., Jones, P., and Greenberg, J. (2002). Who is an open source software developer? Commun. ACM 45, 67–72. doi: 10.1145/503124.503125

Drupal Association (2014). The Drupal Association: Coming of Age. Available online at: https://assoc.drupal.org/node/709 (accessed July 25, 2014).

Drupal.org (2014a). Contribute to Drupal.org. Available online at: https://drupal.org/contribute/drupalorg (accessed November 11, 2014).

Drupal.org (2014b). Decide on the List of User Contributions to be Included on User Profiles. Available online at: https://www.drupal.org/node/2305759#comment-9004949 (accessed September 15, 2014).

Drupal.org (2014c). Drupal Groups. Available online at: https://groups.drupal.org/ (accessed November 11, 2014).

Drupal.org (2014d). Ways to Get Involved. Available online at: https://www.drupal.org/contribute (accessed April 30, 2014).

Drupal.org (2017). Drupal. Available online at: https://drupal.org (accessed February 10, 2017).

Fershtman, C., and Gandal, N. (2007). Open source software: motivation and restrictive licensing. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 4, 209–225. doi: 10.1007/s10368-007-0086-4

Franck, E., and Jungwirth, C. (2003). Reconciling rent-seekers and donators – the governance structure of open source. J. Manage. Govern. 7, 401–421. doi: 10.1023/A:1026261005092

Fuster-Morell, M., Martínez, R., and Salcedo, J. L. (2016a). “Mapping the common based peer production: a crowd-sourcing experiment,” in The Internet, Policy & Politics Conference (Oxford).

Fuster-Morell, M., Salcedo Maldonado, J. L., and Berlinguer, M. (2016b). “Debate about the concept of value in commons-based peer production,” in International Conference on Internet Science (Florence), 27–41. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-45982-0_3

Gallagher, A. (2013). Ethical Principles and Procedures for Teaching and Research. Available online at: http://www.surrey.ac.uk/fhms/Ethics%20Committee/ethicsfiles/Ethical_Principles_and_Procedures.pdf (accessed June 5, 2019).

Ghosh, R., Glott, A., Krieger, B., and Robles, G. (2002). Free/Libre and Open Source Software: Survey and Study. Part iv: Survey of Developers. Available online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20060715124127/http://www.infonomics.nl/FLOSS/report/index.htm (accessed June 5, 2019).

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. London: Springer. doi: 10.1057/9780312299064

Greenstein, S., and Nagle, F. (2014). Digital dark matter and the economic contribution of Apache. Res. Policy 43, 623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2014.01.003

Grewal, R., Lilien, G., and Mallapragada, G. (2006). Location, location, location: how network embeddedness affects project success in open source systems. Manage. Sci. 52, 1043–1056. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0550

Gyimothy, T., Ferenc, R., and Siket, I. (2005). Empirical validation of object-oriented metrics on open source software for fault prediction. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 31, 897–910. doi: 10.1109/TSE.2005.112

Hackman, J., and Morris, C. (1975). Group tasks, group interaction process, and group performance effectiveness: a review and proposed integration. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 8, 45–99. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60248-8

Haklay, M., Basiouka, S., Antoniou, V., and Ather, A. (2010). How many volunteers does it take to map an area well? The validity of Linus' law to volunteered geographic information. Cartograph. J. 47, 315–322. doi: 10.1179/000870410X12911304958827

Hardt, M., and Negri, A. (2001). Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvjnrw54

Howison, J., and Crowston, K. (2014). Collaboration through open superposition: a theory of the open source way. MIS Q. 38, 29–50. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.1.02

Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., and Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: from input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 517–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070250

Jemielniak, D. (2014). Common Knowledge? An Ethnography of Wikipedia. Stanford University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780804791205

Kittur, A., Chi, E., Pendleton, B. A., Suh, B., and Mytkowicz, T. (2007). “Power of the few vs. wisdom of the crowd: Wikipedia and the rise of the bourgeoisie,” in Proceedings of the 25th Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2007).

Koch, S., and Schneider, G. (2002). Effort, co-operation and co-ordination in an open source software project: GNOME. Inform. Syst. J. 12, 27–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2575.2002.00110.x

Kostakis, V. (2010). Peer governance and Wikipedia: identifying and understanding the problems of Wikipedia's governance. First Monday 15. doi: 10.5210/fm.v15i3.2613

Krogh, G., and Von Hippel, E. (2006). The promise of research on open source software. Manage. Sci. 52, 975–983. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0560

Lakhani, K., and Von Hippel, E. (2004). “How open source software works:free user-to-user assistance,” in Produktentwicklung mit virtuellen Communities (New York, NY: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-84540-5_13

Lakhani, K., and Wolf, R. (2003). Why Hackers Do What They Do: Understanding Motivation and Effort in Free/Open Source Software Projects. MIT Sloan working paper No. 4425–03 (New York, NY: SSRN). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.443040

Lerner, J., and Tirole, J. (2002). Some simple economics of open source. J. Ind. Econ. 50, 197–234. doi: 10.1111/1467-6451.00174

Linebaugh, P. (2008). The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All. University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520932708

Luthiger, B. (2005). “Fun and software development,” in Proceedings of the First International Conference on Open Source Systems (Genova).

MacCormack, A., Rusnak, J., and Baldwin, C. Y. (2006). Exploring the structure of complex software designs: an empirical study of open source and proprietary code. Manage. Sci. 52, 1015–1030. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0552

Markham, A., and Buchanan, E. (2012). Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Recommendations From the AoIR Ethics Working Committee. Available online at: http://aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf (accessed June 5, 2019).

Marlow, J., Dabbish, L., and Herbsleb, J. (2013). “Impression formation in online peer production: activity traces and personal profiles in github,” in Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (San Antonio, TX). doi: 10.1145/2441776.2441792

Marx, K., and Engels, F. (1990). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Matei, S. A., and Bruno, R. J. (2015). Pareto's 80/20 law and social differentiation: a social entropy perspective. Public Relat. Rev. 41, 178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.11.006

Mateos-García, J., and Steinmueller, W. E. (2008). The institutions of open source software: examining the Debian community. Inform. Econ. Policy 20, 333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.infoecopol.2008.06.001

Neis, P., and Zipf, A. (2012). Analyzing the contributor activity of a volunteered geographic information project – the case of OpenStreetMap. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinform. 1, 146–165. doi: 10.3390/ijgi1020146

Nordin, D. (2014). Motivation and Collaboration in an Open Source Project: A Qualitative Study of the Drupal Community. Waltham, MA: Bentley University.

Palys, T. (2008). “Purposive sampling,” in The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, Vol. 2, ed L. M. Given (Los Angeles, CA: Sage), 697–698.

Pazaitis, A., De Filippi, P., and Kostakis, V. (2017). Blockchain and value systems in the sharing economy: the illustrative case of backfeed. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 125, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.025

Robbins, C. A., Korkmaz, G., Calderón, J. B. S., Chen, D., Kelling, C., Shipp, S., et al. (2018). “Open source software as intangible capital: measuring the cost and impact of free digital tools,” in Paper From 6th IMF Statistical Forum on Measuring Economic Welfare in the Digital Age: What and How (Washington, DC), 19–20.

Roberts, J. A., Hann, I. H., and Slaughter, S. A. (2006). Understanding the motivations, participation, and performance of open source software developers: a longitudinal study of the Apache projects. Manage. Sci. 52, 984–999. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1060.0554

Robertson, H. M., and Taylor, W. L. (1957). Adam Smith's approach to the theory of value. Econ. J. 67, 181–198. doi: 10.2307/2227781

Robles, G., González-Barahona, J. M., and Michlmayr, M. (2005). “Evolution of volunteer participation in libre software projects: evidence from Debian,” in Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Open Source Systems (Genoa).

Rozas, D. (2017). Self-organisation in commons-based peer production. drupal: ‘the drop is always moving’ (Doctoral thesis), University of Surrey, California. Available online at: http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/845121/ (accessed June 5, 2019).

Rozas, D., and Huckle, S. (2021). Loosen control without losing control: formalization and decentralization within commons-based peer production. J. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 72, 204–223. doi: 10.1002/asi.24393

Rozas, D., Tenorio-Fornés, A., Díaz-Molina, S., and Hassan, S. (2021). When Ostrom Meets Blockchain: Exploring the Potentials of Blockchain for Commons Governance. Sage Open.

Samoladas, I., Stamelos, I., Angelis, L., and Oikonomou, A. (2004). Open source software development should strive for even greater code maintainability. Commun. ACM 47, 83–87. doi: 10.1145/1022594.1022598

Shaikh, M., and Henfridsson, O. (2017). Governing open source software through coordination processes. Inform. Organ. 27, 116–135. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2017.04.001

Sims, J. (2013). Interactive Engagement With an Open Source Community: A Study of the Relationships Between Organizations and an Open Source Software Community. Austin, TX: University of Texas.

Stenborg, M. (2004). Explaining Open Source. Helsinki: The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy.

Stewart, D. (2005). Social status in an open-source community. Am. Sociol. Rev. 70, 823–842. doi: 10.1177/000312240507000505

Txoler, P. (2014). “Making the third industrial revolution,” in FabLab: Of Machines, Makers and Inventors, eds J. Walter-Herrmann, and C. Büching (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag), 181–194.

Viégas, F. B., Wattenberg, M., and McKeon, M. M. (2007). “The hidden order of Wikipedia,” in Online Communities and Social Computing: Second International Conference, OCSC 2007, Held as Part of HCI International 2007 (Beijing), 445–454. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73257-0_49

Wittel, A. (2013). Counter-commodification: the economy of contribution in the digital commons. Cult. Organ. 19, 325, 327–328. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2013.827422

Keywords: value, self-organization, contribution, commons-based peer production, Free/Libre Open Source Software, social production, Drupal, digital commons

Citation: Rozas D, Gilbert N, Hodkinson P and Hassan S (2021) Talk Is Silver, Code Is Gold? Beyond Traditional Notions of Contribution in Peer Production: The Case of Drupal. Front. Hum. Dyn. 3:618207. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.618207

Received: 16 October 2020; Accepted: 22 February 2021;

Published: 18 March 2021.

Edited by:

Nathan Schneider, University of Colorado Boulder, United StatesReviewed by:

Dariusz Jemielniak, Kozminski University, PolandBrian C. Keegan, University of Colorado Boulder, United States

Copyright © 2021 Rozas, Gilbert, Hodkinson and Hassan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Rozas, drozas@ucm.es

David Rozas

David Rozas