94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 03 March 2021

Sec. Social Networks

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.628556

This article is part of the Research Topic Peer Governance in Online Communities View all 6 articles

New models of peer governance are emerging from online communities in the Global South. This is visible in an understudied case of ridesharing “platforms” created on social media communities and materializing in Latin American cities. In this article, I investigate these online communities in different cities of Colombia and how they develop peer governance models. A particular focus is paid to developing organization forms that do not follow the typical structure of firms. In these communities, I study the relationships between members, community managers, and the governance rules they create, while illuminating the hierarchies present, the accountability of their administrators, and its legitimacy. The emerging literature on platform cooperativism, platform urbanism, and peer governance is used to structure a way to understand this new phenomenon with its “southern” particularities. Moreover, in-person and online qualitative research methods are incorporated to engage with the elusive nature of these structures. This will be one of the first studies engaging with the peer governance dilemmas emerging from online communities in the Global South. An analysis on what the platform literature and the institutional ecosystem in developing countries can harness from the particularities of these community-platforms as they evolve in these contexts is also included.

Since the arrival of Uber in Colombia in 2013, and the further expansion of other platforms from 2015 to 2016 (El Espectador, 2019), there have been user complaints about security and dynamic rates, together with driver’s issues with low earnings and high commissions. Also, driving with any type of platform in Colombia can risk the suspension of driving licenses and remarkably high fines. Ridesharing provided by platforms is, as of 2020, still deemed illegal by the Colombian transportation authorities.

Uber and other similar platforms in Colombia are, however, in a legal gray area: The platforms by themselves (not their services) are considered legal as they enter the umbrella of “net neutrality” established by the Colombian government (Congress of the Republic of Colombia, 2011) and its Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (Communications Regulation Commission of Colombia, 2011). However, they are considered to provide an illegal transportation service as per the regulation of the Ministry of Transportation. There have been many regulatory attempts to formalize ridesharing platforms (Congress of the Republic of Colombia, House of Representatives, 2019), nevertheless, the pressure by interest groups, such as taxi drivers, has impeded any relaxation of the transportation regulations or modifications to adapt to new technologies.

Within this context, in recent years there has been an emergence of online communities that use apps such as WhatsApp, Facebook, and Zello as communication mechanisms but still operate outside the multinational platforms. Zello in particular is an application that allows transforming any smartphone or tablet into a walkie-talkie, using the free PTT (Push-to-talk) radio app. It allows for contacting other users privately but, more importantly, it also allows users to join public channels. Among the features of the app, there is real-time streaming, contacts’ availability and status, public and private channels for up to 6,000 users, push notifications, image sharing, and the capacity to work over different types and qualities of internet connections.

It is here where a considerable entrepreneurial and social process is emerging among people in Colombia: Drivers are using online communities on Facebook, WhatsApp, or Zello to create their own “platforms” and compensate for low earnings in the multinational companies. In many cases these drivers even abandon the multinational platforms such as Uber to work fully in their own structures.

Together with WhatsApp and Zello, drivers are also using fare meters via apps such as “Blumeter,” which allows them to coordinate and establish their own transportation schedules, prices, and even geographical divisions to avoid direct competition between them. This level of organization speaks about governance structures and hierarchies, where leadership is performed by specific individuals.

On these emergent online communities-platforms there is also evidence of internal governance rules. These rules include aspects such as internal codes, access-exclusion mechanisms, and fees to be paid to access the mediation benefits of the online community “platform”. Members of these communities are consolidating their role and earnings through referrals and previous ratings in more established multinational platforms, as these communities function on parameters of trust, voice-to-voice recommendations, and individual engagement of the drivers with users. Relationships were primarily built while drivers were still working on the multinational platforms.

Equally, I found out that these groups of drivers include external intermediaries such as doormen at apartment complexes, hotels, bars, and clubs who request trips on passenger’s behalf. Moreover, in these communities there is a purposive framework of communitarian security mechanisms. For example, there are mechanisms established for self-defense against vehicle robbers, community monitoring against police and other authorities looking to fine them, and even recreational activities designed to strengthen the group welfare.

Considering the described context, I develop this article by investigating two cities in Colombia and analyze how communities develop their own peer governance models. I study the characteristics of the online “communities-platforms” to see how the structural arrangements and relationships within them are enforced. Here, I intend to discover how governance norms are developed within these communities, how horizontally or vertically structured the hierarchy of these online communities are, and what the legitimacy of these structures and norms are. Finally, I examine the nature of peer-to-peer relationships in relation to that governance structure, and what the process of accountability (if any) is to which community managers are submitted to.

To evaluate the governance structure of these communities-platforms in Colombia, I discuss the conceptualization of platform cooperativism (Scholz and Schneider, 2017); its further analysis in the literature for the issue of ridesharing platforms Solel (2019, 254–59) can form a suitable theoretical framework. The latter is also embedded in the discipline of platform urbanism. I also consider literature on platform governance Martin et al. (2017, 1396–98) and cite one example coming from the Global North (Stocker and Stephens, 2019), as these are useful to study these online communities-platforms.

Due to the elusive nature of driver’s online communities-platforms, I employ a range of different sources and methods to analyze them. First, I engage with traditional media reporting. Second, I develop in-depth unstructured interviews with members of these online communities-platforms in one of the studied cities, as well as conducting informal ride-conversations. Third, I carried out an online unobtrusive observation (Salmons, 2014) of online communities-platforms.

The nature of the studied communities, and how their governance evolves, demonstrates the need to observe their practices and produce new terminologies, while theorizing about alternative organizational forms in the Global South. This coincides with the institutional impacts of platforms in those contexts. Therefore, I will argue in this article that it is necessary to revise theoretical positions on the nature of the firm and of organizations, as their application to observable practices is not straightforward in the case of the Global South.

In abstract economic theories of the firm (Coase, 1937), it is common to take the institutional structure for granted and “formality” as a given. It is also implicitly, although wrongly, assumed that well-defined property rights and reliable law enforcement are universal, as in neoclassical models. In southern cities, this is often not the case. Within these contexts, I argue that it is common for people to associate and innovate, and it is this type of innovation built out of individual ingenuity and communal links that can be the basis for a different understanding of platformed associations.

To the best of my knowledge, this is one of the first studies addressing the relationships, structures, management, and accountability features emerging from online communities in a country in the Global South. I begin this article with a brief discussion of the data, methodology, strategies, and ethical implications linked to the online methods used for this research (James and Busher, 2009; Salmons, 2014, 154). Furthermore, I develop a theoretical framework and critically discuss platform urbanism, platform governance, platform cooperativism, and the need to reconsider some of its propositions. In the subsequent sections, I elaborate on the case studies and discuss the empirical findings in each of them.

I conclude the article with comments on what the emerging literature on platforms could learn from the specific particularities of these different types of online communities-platforms in urban environments. Moreover, I comment on what the institutional ecosystem of transportation in Colombian cities and other places of the Global South can harness from these alternative governance models.

This study builds on previous engagements with the impact of platforms in cities in the Global South, which we could include in the emerging discipline of platform urbanism, here focused on urban transportation (Granero-Realini and Bercovich, 2018; Reilly and Lozano-Paredes, 2019). For this specific article, I engage with an interpretivist paradigm, looking at how drivers of online “communities-platforms” are constantly involved in interpreting their world and in developing meanings for their activities. Furthermore, I adopt an interpretative stance on the phenomenon being explored and thus inform the way in which theory is applied to the discussion and the conclusions of this article. This methodology is also informed by my personal context, perspectives, and lived experience in Colombia and Latin America.

I use an instrumental case study approach as a methodology strategy (Yin, 2009) to engage with the studied online communities-platforms. I selected two online communities in the cities of Bogotá and Cali to uncover the themes on peer governance dilemmas that this article addresses. These case studies are “Drivers Club Bogotá” in the city of Bogotá, together with “Los Sellos” in the city of Cali.

For this article, part of the discussion and conclusion is built on in-depth unstructured interviews with drivers of online communities. This field research was carried out in mid- 2018, and in total I interviewed five drivers (including one administrator) from the “Los Sellos” community, both male and female, between the ages of 27 and 52. Each interview had a duration of approximately 1 h, and all the interviews were conducted in Spanish, as it is the native language of the researcher and the interviewees.

Together with the in-depth interviews, I also developed informal conversations, which I call “ride-conversations”, which were approximately 30–45 min long in each of the case studies. These 18 ride-conversations were performed in-situ (10 in Cali, eight in Bogotá) in July 2019, and important insights were extracted from them, which will be discussed further in the article. All the interviews were transcribed, and the resulting texts coded (Saldaña, 2021) and analyzed to find themes related to the questions on rule creation, hierarchies, relationships, and manager accountability among online communities. Equally, the notes emerging from the informal ride-conversations were coded and analyzed to identify hints related to these topics.

To complement the data from the interviews and informal ride-conversations, I also conducted online unobtrusive observation Salmons (2014, 57–9) of posts in the Facebook group of the “Driver’s Club Bogotá” online community from March 28, 2017 (creation day of the group) to August 2019. This Facebook group (Drivers Club Bogotá Blog, 2020) is the only place on social media where these conversations are publicly available for this case study. There is no access to the internal conversations of the Zello Channel or the WhatsApp groups. The latter would require a structure of participant observation and being a member of the group, thus interacting with them in that digital space. This would have implications for the methodology and the research data collected.

This secondary data also includes a documentary analysis of traditional media articles. The latter ranges from the first time the phenomenon of these online communities-platforms was documented in Colombia in May 2018 to August 2020. This was done in the national high circulation newspapers EL TIEMPO and EL ESPECTADOR, together with the regional newspaper (Cali) EL PAIS. From this data, I took notes, coded, and analyzed them to find themes related to this article’s topic. As with the interviews and informal ride-conversations, this process of analysis was developed in Spanish.

In a context where platform intermediation blurs the lines between the digital and the physical realm, online research methods help to engage with the meanings embedded in the environment in which online communities develop. The usage of online research refers to a completely new environment in which peer governance can be studied. Online research, in this case complementary to in-situ research, also responds and recognizes the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic which, even if it limits in-person fieldwork, opens the door to many new opportunities of engaging with online methods.

Among ethical challenges related to this study, there is the consideration of issues of informed consent and subject data protection. For addressing this, I developed the design of the interviews in a manner which attends to informed consent. I also ensured that the interviewees clearly understood the associated risks and benefits related to the study, together with a previous presentation of the information for an easy opt-out. This was done with both the formal interviewees and the more informal ride-conversations with the drivers.

The aim of the informal conversational (Mikkelsen, 1995) for the case of the “ride-interviews” in the form of unstructured interview is to uncover strategies of online community members and what the nature of their organization is. An unstructured interview or guided conversation was appropriate in this case, as I wanted to study a range of organizational and networking strategies among drivers, as well as the behavior of this particular group. The applied method was a guided conversation, and each driver was previously briefed about the interview when boarding the car after requesting one of the services. Regarding questioning techniques, the interviews were developed with open-ended questions. The process was interesting as it necessitated an introduction of the interviewer that helped to “break the ice” with the driver.

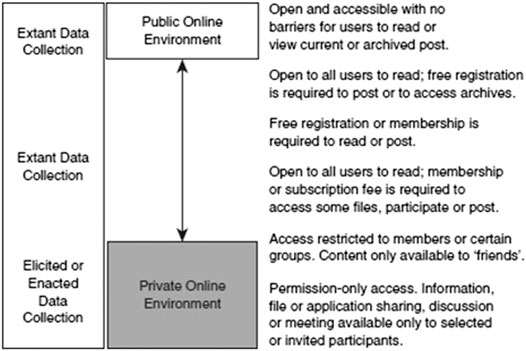

On the other hand, regarding the unobtrusive observation of the social media groups, I ensured the anonymity of the subjects when analyzing and publicizing the data in this article. The discussion on unobtrusive observation in the realm of online ethnography, however, brings us here to address issues linked to the “public-private internet continuum” (Salmons, 2014, 156) (Figure 1). In this structure, developed specifically for engagement with qualitative online research, there is a large and somewhat diffuse space of analysis between the private and the public online environment. This includes an extreme where data is open to all users to read with a free registration to the platform, to the other extreme where the data is exclusive for selected participants, usually needing admission to the group by the community manager.

FIGURE 1. The public – private internet continuum. source (Salmons 2014, p. 156. Citing Vision2Lead, Inc. 2013).

Issues on open access and registration definitions are solved according to the nature of the online space being researched. I observe what is considered ethically permissible Salmons (2014, p. 154) ‘if the online setting is perceived as public’. Here, it is stated that researchers can quote and analyze the information freely considering the following criteria (James and Busher, 2009):

• That the information of the online forum, group, or community is officially and publicly archived.

• That no password is required for archive access

• That no site policy explicitly prohibits it

• That the topic is not highly sensitive.

Considering the case of Drivers Club Bogotá (Drivers Club Bogotá Blog, 2020), it can be attested that all these conditions were met, and that having a personal Facebook allows for visiting the pages directly, where the information is publicly accessible, although authorization is required for accessing the groups.

I can attest that the observations developed for this article are between the public and private online environment of the internet continuum. All the social media pages analyzed are open for access, but the groups required a manager authorization to participate, which was given in consideration with informed consent and reaffirmation of the anonymity of members via Facebook message related to the observation of the group. Therefore, at least for this specific article, there were no ethical issues regarding non-obtrusive observation. Registry in the Zello channel or WhatsApp groups is a further step that did require internal participation in the online community, and that step was not taken for data collection linked to this article.

There is abundant literature on governance models, and more recently on peer-to-peer governance, although it is not my intention in this article to elaborate on a comprehensive review on this literature. However, I am interested in focusing on references of governance models emerging in “platformed” communities and exploring the nature of their structures. At the same time, there is also an increased emergence in the literature related to the impacts of platforms in broader institutions and spaces.

Platform urbanism is a recent and emergent theme in urban futures’ research and studies. The elaboration of the concept ‘platform capitalism’ termed by Srnicek (2016) helped to frame platforms in current debates of political economy, especially considering the increasingly central role of data, instead of traditional commodities, in the new forms of capitalism. It was from the recognition that platform capitalism has relevant and abundant expressions in the urban space that the theme of ‘platform urbanism’ came to be.

Some authors who focus on emerging engagement with platform urbanism refer to platforms as extractive agents in the city. For example, Krivý (2016, p.15) sustains the notion that the effects of platforms in cities are linked to the accumulation of centralized corporate power and the reproduction of social inequality linked to the latter. This perspective on the conflicts emerging from platforms in cites was addressed even before the emergence of big platforms such as Uber (Gillespie 2010) in relation with the increasing accumulation of power for framing the discourse in the urban space.

However, here I argue that platforms in cities are not only mechanisms of extraction that could find solutions with the ‘democratization’ proposed by proponents of platform cooperativism (Scholz, 2016), or entrepreneurial activism within platforms (Sandoval, 2020). Platforms are also, more than anything, ecosystems of interaction. They are special and new social spaces which exponentially expand the ability of people to interact, building a relational nature that is behind the creation of all types of markets Brown et al. (2004, p. 747–50).

In this sense, the work of Barns (2020) is very illustrative in how platform urbanism can be defined and, furthermore, studied. Barns (2020 p. 21) argues that platform urbanism more than everything is an urban ecosystem of new relational processes, building on ‘co-constitutive natures of urban institutions, actors, governing tactics, modes of expertize, training data, and ways of knowing and designing cities.’ And that in this case, platforms are actors of the enormous variety of relationships and interactions which are natural to cities.

Barns (2020) considers that platform urbanism is the ecosystem which embodies the many ways in which the interrelations of urban life develop, mediated by platform technology. Moreover, he believes that platforms are triggering very specific new forms of interactions, markets, and agency.

Platform technology when interacting with social networks is also giving strength to new ways of understanding organizations and institutions, and the way in which people construct governance alternatives. There are valuable examples, such as from Hartl et al. (2016, 2758) and Martin et al. (2017, 1396–97), focusing on the organizational models for conceptualizing platform governance.

Martin et al. (2017, 1403–05) in particular offers a framework which differentiates forms of platform governance and original ownership. In this framework, the forms of membership and leadership, as two models of platform governance, are presented using the example of Freegle: A democratically governed platform which is deemed to accommodate the values of both platform users (members) and owners (leaders).

Studying this division shows that more instrumental structures are held as important by the owners’ side, while social and environmental values are important for the members’ side. The differences of these two actors in platform governance, and how they can create eventual conflict, are relevant if we are to engage with the hierarchical structures of any type of platform organizational operation.

Structures of platform governance and how a democratically or cooperatively managed platform can give better social outcomes is also the base for the conceptualization of “platform cooperativism”. Scholz and Schneider (2017, 20–27) in their work with several other authors on platform cooperatives show an excellent example of what are we talking about when engaging with platform impacts on emerging online communities.

Scholz and Schneider (2017, 9–29) rightly present that the business model of centralized multinational platforms of the “sharing economy” reproduce characteristics of profit capture from operators in a monopolized or oligopolies marketplace. In this case, the situation is not different or innovative in relation with other capitalist forms. Equally, they argue that a centralized model does not necessarily give agency and power to its users, or the “members” side if we are to use the classification termed by Martin et al. (2017, 1405).

The response of the authors involved in this literature is the advocacy toward cooperative platforms as a model to confront the centralized multinational structures of “sharing economy” platforms. These platforms are framed as community builders but engage with members exclusively as costumers. As Tonkinwise, (2017) states (in Scholz and Schneider, 2017, 128–9) states, platform cooperatives are therefore deemed as an opportunity for designing and reviving the project of establishing a genuine sense of community.

In this narrative on platform cooperatives, it is also recognized that we as a culture are becoming more cooperative. Commons-based peer production is an example of the possibility of large-scale enterprises using models of platform governance (Benkler, 2017 in Scholz and Schneider, 2017, 91–5). However, this literature also acknowledges that decentralized governance forms in platforms do not imply horizontality. There is a need to engage with the idea that the communities behind these platforms both give value and build it for society at large (Fuster-Morell, 2017 in Scholz and Schneider, 2017, 213–7).

Moreover, the structuring of platform cooperatives is argued as being an issue of stakeholder interdependence rather than autonomy, agency, and independence of individual actors. There is a push to abandon the emphasis on autonomy by previous cooperative conceptual engagements and embracing the idea of community interdependence. The goals of egalitarianism, democratic governance, and equity are now facilitated by platform technology (Rushkoff, 2017 in Scholz and Schneider, 2017, 33–7; Hoover 2017, in Scholz and Schneider, 2017, 108–12).

Both the theoretical structuring of platform cooperatives and the impact of the platform economy at large are complemented by another contribution which is also useful for the development of this article: A typology of the different characteristics and impacts of the platform economy, which is elaborated by Solel (2019, 247), being especially operative for engaging with the governance of platform and platformed communities. Solel’s classification is useful to differentiate between platform capitalism, the sharing economy, and platform cooperativism. Moreover, the classification provides a clear structure for the elements of platform governance, including ownership of the platforms and decision-making within them.

In the realm of the “platform economy”, ownership is defined by this author as belonging to private individuals or companies, with multiple shareholders and no relation between ownership, control of the platform, and its use (Solel, 2019, 256). Equally, “decisions” or decision-making is deemed exclusive to the owners, who are accountable only to the shareholders (Solel, 2019, 256). As what is classified as “sharing economy” goes beyond the original definition of this phenomenon, Solel (2019, 257) rightly observes that ownership for this case is varied.“Sharing economy enterprises can use all forms of ownership. They may be owned by a public authority, a non-profit, users or some users, or by a private company”.

Here, decision-making is assigned as determined by the owners and emerges in various combinations and forms. For platform cooperativism, however, the definitions provided are more nuanced and establish that in the case of ownership, it lies on the side of the users:“The owners of platform cooperatives are the users. In certain cases, they can be some of the users – like service-providers who are members, while the consumers are not, or consumers who are members purchasing from non-members. Another option is of a multi-stakeholder cooperative combined of private individuals of different groups, or a combination of private individuals and a public authority. In other cases, ownership can be of a non-profit or public authority, as long as the decision makers are the members;” (Solel, 2019, 259).

This “design guide” of what defines the governance of platform cooperatives is a very powerful tool which attests to the diversity and flexibility of the structures present in platform cooperativism. Defined here also is its decision making as a democratic organization, linked to the basics of cooperativism (one owner, one vote).

Observing the framework proposed by Solel (2019), I observe that the legal definitions of cooperatives linked to the development of “platform cooperatives” are not to be forcibly intertwined. There is the need for more flexible definitions that would help us to engage with the characteristics of the platform economy and its effects in new forms of organizations and their governance.

“Platform Cooperatives” in this sense are understood in this article not as a legal association or established institution or organization. Rather, it is a theoretical term in which the democratic governance of the emerging type of platform organization is central to its definition.

However, it is also interesting to consider the characteristics of these types of organizations when emerging from online communities in low institutionalization contexts. One example is “Arcade City”, a network that grew out of a fragile governance context (Stocker and Stephens, 2019). This platform evolved from social networking in Facebook, which emerged at the time thanks to the platforms Uber and Lyft stopping their service in Austin, Texas, due to regulatory failure and conflicts with the local government.

In its evolution, the platform started with a preserved interdependency between stakeholders, observable in its functionality (Stocker and Stephens, 2019, 19–24). This online community however, evolved toward a natural hierarchization. The platform showed that beyond an intention of horizontality and community building, a clear structure emerged which centralized its hierarchy in the function of the original community managers (the initiators and “owners” of the platform). These managers, despite issues not pertinent to this article and the fluctuation between roles, preserved their position in the continuing evolution of the community (Facebook, 2020a).

Observing the example of Arcade City, it can be argued that although interdependence and full horizontal democratic decision-making is a laudable goal exposed by the conceptualization of platform cooperativism (as seen in the work of Solel, 2019 and Scholz and Schneider, 2017), the articulation of platform cooperatives will tend to be less egalitarian and more meritocratic. Hierarchies even when developing processes of mutual coordination, (or what Bauwens et al. (2019, 19) denominate as stigmergic collaboration) necessarily develop as a process of governance. Governance that needs a managing actor, the benevolent dictator, emerges naturally in these communities.

Institutional characteristics of markets in the Latin American context Schneider (2013, 15–18) are the reason for this differentiated evolution. Hierarchies, clientelism, and a favor toward certain groups of interest over others have meant that people no longer trust hierarchies -of exclusion- and work against them for both communal and individual interest. To a point that acknowledges the enabling effects of technology, the government and the corporations are regarded as unnecessary, and people are no longer looking for their approval or help to build new alternatives of well-being.

Those processes of transformation, however, cannot escape the evolving nature of hierarchies built out of meritocracy, linked to the first “entrepreneur” who, by the nature of its idea, transforms automatically into the owner. This then replaces the hierarchies of exclusion of Latin American capitalism Schneider (2013, 15–23) with internal governance structures in their online communities. In turn, this ends up giving its members the conditions that the alternatives within the structures of government regulation and multinational corporations cannot provide.

There is a need for further research mapping of the emerging governance models and analysis of them as to their success for delivering social and economic benefits. For this article, the literature on platform cooperatives and peer-to-peer governance is useful in articulating the nature of the studied online communities and gives hints on their structure. Equally, previous and seminal engagements in organizational theory, such as the garbage can model of organized anarchies Cohen et al. (1972, 1–5), help us to traduce the nature of structures growing from informal or not clearly defined settings.

However, all this literature falls short on engaging with the paradox where horizontal structures of interdependency naturally and unequivocally evolve to centralized hierarchical systems. The latter talks to us about how the agency, autonomy, and independence of individual actors, in this case, the managers’ role, cannot be ignored by having an aspirational ideal of absolute equality and interdependence in platform cooperativism. Equally, it refers to the individual agency of members, who articulate themselves into this communitarian structures but do not abandon their own interests, especially in terms of economic gain.

It is the purpose of this article then to contribute to the mapping of different governance models that are happening in online communities and to look for a new model. In the following sections, this article will engage with two selected online communities. It will study them within the previously analyzed theories and concepts and the research questions linked to this article: How governance norms are developed, what the structure of their hierarchies is, their legitimacy and the nature of peer relationships, and the process of accountability for those who are high in the structure.

As stated by this community’s name, the idea behind its organization started, and is still perceived by the members and the administrators, as a “Club”. However, its organization goes beyond the conceptualization of a club, and denotes the presence of a more sophisticated construction of governance structures.

The community was begun in October 2017 by a group of drivers from multinational platforms such as Uber, Cabify, DiDi, Beat, and others which are active in the city of Bogotá. It’s main purpose at the beginning, according to the founder, was to “Help each other on night shifts on the apps, just to hold a conversation and alert everyone if there were any problems” – Pedro (founder of the community, - named changed for anonymity).

Equally, as the founder comments:“We were drivers of apps who had other occupations, and this was a complementary job to sustain our families, and it was interesting to find people in a similar situation”.

Furthermore, what started as a WhatsApp group built from some drivers who met at the “activation” days of the multinational platforms, kept growing into an online community. This community turned to be mostly based on a Facebook group (created by the original drivers), and amounts to 6,000 members as of 2020 (Drivers Club Bogotá Blog, 2020). Currently, this group has framed its own branding, a high level of audiovisual production, centralized messages from the administrators (the original founders of the group), and even a website (Drivers Club Bogotá Blog, 2020).

The growth of the first WhatsApp group, the creation of others, and their development in the Facebook group was first linked to their utility in sharing information on accidents, traffic, and the presence of police checkpoints in the city. The third point was so these checkpoints could be avoided because, as I mentioned before, drivers are in peril of losing their licenses or receiving high fines due to their work on the platforms.

Moreover, the expansion of this specific online community is also linked to platforms such as Uber using cash payments in Colombia (Uber Blog Colombia, 2017). This payment system is designed in a way that every time a driver takes a cash payment, it incurs a debt to the platform for the cost of the commission. This allows Uber and other companies to expand their service and critical mass, being sustained every time a passenger uses the service by credit card payment, when the commission debt is paid.

This, however, created an incentive for drivers to avoid credit card transactions completely, by building more direct relations with customers, and leaving multinational platforms if the debt amounted to an unpayable state. There is no shared information between systems and platforms and no traceable credit history for drivers, so they can do this freely.

Members of Drivers Club Bogotá started to develop direct relationships with their customers (users) who were usually either drivers of other platforms or people from their immediate social circle who were also members of the WhatsApp groups. This prompted drivers to abandon the platforms altogether and begin to use the WhatsApp groups as their way of contacting members and developing all their payments using cash.

Equally, drivers started to use the Facebook group of Drivers Club Bogotá and their own WhatsApp groups to establish a system in which if one of the drivers is contacted directly by a user, and it cannot provide the ride, it locates some other driver who is near and can effectively do it. The governance of these first groups did not represent any costs for members and it was exclusively built on community links and social capital.

As I mentioned above, the online community evolved from a unique WhatsApp group into several WhatsApp groups and then into a Facebook group (Drivers Club Bogotá Blog, 2020) which united all the drivers providing this form of decentralized cash-based ride service. This went alongside an emergent system of collaboration for ride-provision, and no clear hierarchies or structures of governance, nor specific rules. There were only informal processes of community membership that evolved from social links.

However, member growth produced a big evolution and change in these structures. In October 2018, the first evidence of governance documentation emerged, which established the different norms regarding the inclusion of drivers into a centralized communication channel powered by the “Zello” app. This mobile application works as a push-to-talk walkie talkie in exclusive channels and became a definitive tool for platform drivers who were already members of the online community.

Members of Driver’s Club Bogotá were prompted (Drivers Club Bogotá Blog, 2020) by the founders to join a centralized Zello channel with the narrative and framing of it being a support network and facilitating the growth of the community. This support network claimed to be the new place to report the state of the road, traffic congestion, police checkpoints, expand cash-payable rides (as the contacts from drivers on WhatsApp groups were harnessed), and give security support in case of robbery or other incidents.

Among the normatively of the “Zello” channel, as observed in a post in their Facebook page, it was established that:

1. On the community chat no memes, jokes, chains, or religious images were allowed.

2. Commercial publications, including sales, products, and service offerings, have a cost and are canalized by the administrators.

3. The main report and communication channel is Zello, and WhatsApp groups were now to be limited to the announcement of dates for progressive activation of members into the Zello channel.

4. Any disrespectful conduct or insulting vocabulary will result in immediate expulsion from the Zello channel.

5. Permanence in the community was linked to the following of these fundamental rules. Non-compliance results in expulsion, and if expelled an undefined economic penalty will be charged for re-admission.

Moreover, the organization on this centralized channel also created codes and keywords that were of mandated use for being part of the community. These codes include references to:

• Estimated Time of Arrival (EW)

• Rest for Coffee, Smoking, or for a “Express Conversation” (R6)

• Situation or Problem (R8)

• “Fast”

• “Understood” (R10)

• “House”

• “Cellphone” (Z2)

• Suspect situation – approach other members

• “Pending”

• “User”

• Real-time location (20W)

• No news – “all good” (X3)

• “Wife” or “Husband”

• Report of situation for precaution

• Drunk or Drugged user

• Restroom

• Familiar

• Male (OMEGA)

• Female (ALFA)

• Senior (ROBLE – “Oak” in Spanish)

This use of alphanumeric or purely numeric codes evolved from more than solely a communication efficiency device to a management tool to organize the processes of the community.

The organization of these language codes and governance rules, including the policies for termination of membership and exclusion of the community, shifted the structures of Driver’s Club Bogotá’s Facebook community and their WhatsApp groups. Even if membership was not enforced and signing in to the Zello channel was not mandated (yet), it produced a hierarchization that was not present before.

A soft introduction of governance rules for the use of the Zello channel was framed together with the benefits of belonging to this centralized form of communication, and to a narrative of community growth as a “big family”. Monetary and price incentives were also announced in the (Facebook, 2020a) group to promote the participation of drivers. Furthermore, the introduction of the Zello channel and the rules associated to it came together with an association with other groups of drivers of different types of vehicles, including trucks, minivans, and even motorcycles (providing moto-taxi services).

Expansion and association with other groups and other digitally based communities for transportation provision was commanded by the original community members and managers, but especially by its original founder and leader. This entrepreneurial leader, with a charismatic personality and persuasion abilities, has been framing a brand for himself and the community, and this has become clearer as the community has grown.

Driver’s Club Bogotá, before the centralization attempts in the Zello channel, was a somewhat loose community of drivers who started to organize to support each other and then structured an informal mode (built from social and community relationships). This process was known to the founders who encouraged it and even participated in it.

At first there was not a clear organizational model, nor a defined way to structure decision-making. It was an emergent and organic community of cooperation, which we could map with the diagram (Figure 2) in the concluding thoughts.

This first structure was built on informal structures and by the free association of members, who formed a hierarchy primarily based on members cooperation but also on individual interest in coming together to provide more efficient ride services, and thus earning more money. To this effect, we cannot refer to this first structure as either platform cooperativism, using Solel’s (2019) typology, and nor it can be related to the conceptualization of a “sharing economy” heterodox platform. This order was spontaneous and classifiable within the characteristics of an organized anarchy present in the structures of the garbage can model of organizations (Cohen et al., 1972).

The first build-up of governance for Drivers Club Bogotá was decided on an anarchic and incremental process, in which decision-making evolved through the horizontal input of members. There were members who came up with the idea (not the creators of the Facebook/WhatsApp groups or would-be administrators) of using WhatsApp to connect with customers, and the administration of that communication fell upon those drivers who came up with the idea. Neither was there a clear authority beyond participants who became decision-makers in the creation of the groups.

However, further expansion of the community happened when the administrators and original founders of the online group created the “Zello” channel and started their process of centralization. These administrators were always the same six individuals, original founders of the platform, and their intervention re-arranged the structure of the community organization (Figure 3).

A hierarchical structural organization with an organized anarchical evolving process rapidly and drastically was transformed into a hierarchical organization. The leadership role that was assumed by the administrators, and especially by the founder, who also became a spokesperson when issues of rideshare platforms emerged in the national debate (RCN, 2020). The leaders control the communities, manage and organize the payments, and keep the accounts, which gives them the advantage to situate themselves, not formally, but tacitly, at the top of the hierarchy – thus transforming hierarchies into hierarchies.

Even though the enforcement of rules of the Zello channel does not apply to the whole community (as in not all members are required to sign into the centralized structure) there is a process of exclusion-inclusion around the Zello channel, leaving members of the WhatsApp groups out. On the other hand, new members of the (Facebook, 2020c) group, or those who came to the community by means other than the original WhatsApp groups, are also joining the Zello channel, and incorporating to the structure in its recent form. These newer users are unaware of the previous hierarchical construction.

The centralization of the structure means that the decision-making process transformed from an organized anarchy into a different combination in which democratic structures are not present. The decision to centralize into a Zello channel was made exclusively by the founders of the original communities with a great risk: The non-validation of the members of the community could have caused its disintegration. However, the Zello channel introduction was successful and members accepted the new hierarchies without visible conflicts, leading us to question the issues of legitimacy and accountability of the administrators and the imposed hierarchy in the online community.

An easy transformation of a governance structure from a loose hierarchy or organized anarchy into a clear hierarchy where decision-making was allocated to managerial individuals suggests ideas about a natural legitimacy by these managers. This legitimacy however does not necessarily come from leader popularity, which could refer to an election process. Rather, it emerges from a transactional articulation, in which members cede their “sovereignty” in decision-making in exchange for the benefits of community membership.

Accepting the new structure is incentivized by mediation delegation, an increase in business, and a sense of community that is framed by the recreational and communal activities developed by the administrator. As told by a community member named Juliana (name changed for anonymity):“The Zello channel is way more convenient, before in the WhatsApp groups there was no clarity on who was going to take the ride, and many times I lost passengers, with the Zello group I know exactly where to go and who to pick up.”

According to one administrator named Fernando (named changed for anonymity), it was clear when the community began to grow beyond a manageable point and the decision of creating the Zello channel was a necessary opportunity:“We decided to use the Zello app when drivers started to have problems with WhatsApp, there were too many of them. We were happy but needed this app to provide better services, especially when more of our drivers were relying only on the WhatsApp thing, they quit the apps.”

The willingness of drivers not just to quit the established platforms, i.e., Uber, but also to join these groups and accept the soft imposition of governance rules linked to the Zello community talks to us about a calculation and acceptance of risk. Members of the community report that joining Drivers Club Bogotá, even when not working with the multinational platforms, is a risk worth taking. It is a way to gain more money and avoid the problems of rate settlement and complaint mechanisms of multinational platforms.

Equally the administrators of the online community have been smart in framing a brand specifically linked to the Zello channel. This branding includes the promotion of community cohesion which includes social events, parties (online parties during the COVID-19 lockdown), trips to nearby tourist locations, and the articulation of sanitary and cleaning rules for the post-lockdown return to work. All these strategies for social cohesion are framed exclusively for members who have already signed to the Zello channel and are well perceived and embraced by the community members.

As exposed by Santiago (named changed for anonymity):“The Zello channel is the best way to find out about what’s going on, and even during the lockdown we got messages everyday asking us to be together as a family. Asking God to help us all. I felt that we were a family in these times”.

Members clearly assign legitimacy to their membership in the community, no matter the governance model. They recognize that these schemes are a way to achieve personal gain, in some cases even growing what they define as a “self-managed micro-business” with their own vehicles and improving their working conditions. Female drivers for example even attest that they enjoy the security that passengers are vetted by trusted community members, and the Zello channel has demonstrated a more efficient way to connect with fares during dead hours when markets are saturated.

All of this refers to a cohesive community that shows no special interest in the characteristics of decision-making in the organization and does not show evidence of concern with the structures of the hierarchy they tacitly joined. This then leads to the main problem in the accountability of administrators: accountability is virtually non-existent. There is no process or channel to question the structures of the authority, the selected language for the online community, or the rules of permanence. If one of the governance rules is broken and the member is expelled, there is no mechanism for appealing or returning beyond payment of a monetary penalty.

Additionally, other elements for the functioning and definition of the community have no process of discussion or contestation. Fare rates are defined by the community administrators daily using the application Blumeter, which bases its tariffs according to the price of Uber rates, minus the commission. This application works as a taximeter to manage trips and calculate in real-time the price of the trip, personalize values, use dynamic rates, see details of the trip, and calculate return. The independence that the use of this application could mean in terms of tariff definitions, for example allowing individual drivers to lower their rates to become more competitive, is restricted by the centralized administration of the community.

These structures raise the question of how cooperative this platform can be if decision-making and leadership is extremely centralized and, we could say, authoritarian. Even if this authority is coming from benevolent dictators. It certainly does not meet the definitions surrounding platform cooperativism (Scholz and Schneider, 2017 and Solel, 2019, 259), and comes close to a structure that is not far from the extractive structures of platform capitalism (Solel, 2019, 256).

In the “platform” created by Drivers’ Club Bogotá, owners are making decisions and are not accountable to members (although they may be accountable to other stakeholders). However, it could be argued that ownership is not exclusive to the administrators, as there are no specific profits or dividends that the community is creating for itself. The profit generation rests in the drivers who “own” the platform, even if submitted to an unaccountable governance hierarchy. I argue then that these emergent platforms fit with the intended governance model of a “sharing economy” Solel (2019, 257) where enterprises can use all forms of ownership in a flexible manner, profits are made by members, and decision-making is carried out through a variety of ways, determined by the owners.

In the following, I will discuss the other case study of this article which, even if similar in evolution, has a different process and structure which will be interesting to engage with. We will see that the presence of this, and many other groups which the scope of this article is not able to cover, already gives us evidence of the diversity of governance models and how the classification of “sharing economies” could be correctly applied to them.

As observed in the discussions on different (Facebook, 2020b) groups, interviews, and in traditional media, Cali, the second largest city in Colombia, was the birthplace of the phenomenon of drivers creating alternative “platforms” from their online communities. This process was attested to in my own previous research Reilly and Lozano-Paredes (2019, 431), and equally identified very early by media reporting (El Pais, 2018).

The online community of drivers, known colloquially as “Los Sellos”, gains its name from the use of a Zello channel, similar to the structure of “Driver’s Club Bogotá”. (They have used several names for their group, but their external identification and recognition by society has not followed suit). Similar to the previous case, “Los Sellos” emerged first from two big WhatsApp groups made up of drivers from Uber and similar multinational platforms. These groups evolved organically from drivers who met in different circumstances, including the “activation” days at the multinational platforms’ offices, and social media groups dedicated to “drivers” of different platforms.

One of the WhatsApp groups was formed by approximately 200 drivers in late 2017, and the other one by 100 drivers the same year. In general, and again like the case of Driver’s Club Bogotá, these groups served at their start as a support network to share information regarding authorities' checkpoints, traffic jams, accidents, etc. Likewise, if a driver was contacted directly by one of its clients (with whom the drivers build loyalty and community links) and cannot provide the service, whichever member of the group is closest can carry out the ride. This mediation generally involved no cost to members and was handled informally.

I could note from the discussions emerging from the case in Bogotá that drivers took the idea of creating the WhatsApp groups for building a “platform” of ride-hailing services specifically from this group in Cali. Equally, there were direct references from drivers in this city, bringing their experience to the group of Driver’s Club Bogotá. Furthermore, issues of legitimacy and accountability of managers were also replicated, even if the hierarchies are somewhat vague.

The experience of “Los Sellos” has a particularity in its evolution which can help to illuminate the debate: It resulted in the creation of financial collaborative structures, cooperation with external actors, and the geographical division of the city to avoid competition. All of this emerged from the collaborative structure and defined its increasing popularity, how it competes with multinational platforms, and how it inspires business models of local enterprises (VICE, 2019).

From the informal modes related to one of the identified WhatsApp groups, administrators centralized their efforts by using the Zello channel. However, there is evidence that, separate from the case of Bogotá, these administrators submitted to the community the decision of using the Zello channel. Moreover, they even voted on the WhatsApp group on the conditions for the structuring of the new “platform” around Zello.

It is clear that the reduced number of group members helped this organizational level. Even if they opened their WhatsApp groups beyond the 256 members limit, their group fluctuates to date between 290–310 drivers, which reduced scalability but allowed for a smoother organizational process.

When the first Zello channel for this group was created in January 2018, the following rules were submitted for consideration of the online community, as informed by one of the managers:

1. All the members of the group must own their own car, or if they are doing work for a patron, the patron should also be a member of the group.

2. If a driver wants to be added to the Zello channel, it is necessary that an “active member” nominates him (It is not clearly defined what it is meant by “active” member).

3. There is a one-time fee for entering the group of $100.000 Colombian pesos (approximately 27 US Dollars)

4. There is a monthly fee of $40.000 Colombian pesos (approximately 11 US Dollars). If the member does not pay that monthly fee, they are excluded from the platform. If they pay again, they are let back in.

5. All the collected money goes to a “collaborative fund” destined to the “administration” of the platform. More important is the payment of fees for recovering vehicles confiscated by authorities. (Confiscated in this case due to the previously mentioned legal limbo in which this type of transportation service experiences in the country.)

6. All earnings are for drivers or their patrons.

Separate from the case of Driver’s Club Bogotá, governance documentation is not available anywhere in the social media groups of the drivers, but rather in internal chats and memos. The characteristics of these rules are bound to be more fluid, as they were told to the researcher by drivers themselves, and not by a specific document that is available in their groups.

However, it is interesting to point out here how the development of governance rules in this case is structured not on a community construction (as could be argued for the case of Driver’s Club Bogotá), but in the clear mechanisms of payment and the creation of common funds for the group. These rules also cover cases in which a member owns more than one car and puts other drivers to work for him or her, under the accepted norms of the online community. It should also be noted that the association process for these drivers, and their collaborative funding creation, does not suppress either their individual interest nor their search for profit.

In other words, the money they add to the collaborative fund for the growth of the community and for self-preservation against punitive measures of the authorities does not transform into a common pool of earnings. I could even argue here, from the conversations with the drivers, that if individual earnings were to be added to the “collaborative fund” and then distributed democratically, the community organization would collapse, as the drivers would quit.

The financial structure that surrounds governance of this online community is furthermore complemented by the creation of a codified language of communication, which helps with the structuring of the “platform”. But, and again, this is different from the previously studied case, as the language is more reduced and lacks elements of community-building and welfare, which are replaced by fund structure and management. These codes include references to:

• Estimated Time of Arrival (TLL)

• “Location” (LO)

• “Cellphone” (CEL)

• “Member” (M)

• “Suspended member” (MS)

• “Report” (RE)

• “Payment” (PA)”

These codes are available in the public access page of the Zello channels online and were provided by one of the interviewed members.

This group has five clearly defined leaders who manage the Zello channel and expand the structure of the community, making use of the “collaborative fund” to add innovation that is not present in the other case study in Bogotá. There are also some other organizational innovative structures which engage with internal and external competition.

Due to security concerns in this Colombian city, it is very common for people living in middle-class gated community buildings (a prevalent urban housing form in Colombia), to rely on security guards for ordering a ride from trusted sources. This is a process that continues to be applied for ordering regular taxi cabs, for example.

The structure of this case for “Los Sellos” depends heavily on an association with those security guards. In this case, the administrators of the group make use of the “collaborative fund” (which, making a quick calculation of annual income, amounts to roughly $144,000,000 Colombian pesos (41,900 US dollars), not counting the entry fee) to pay these security guards $1,000 Colombian pesos (Approximately 0.27 US Dollars) for each ride they can pitch in. Equally, they pay them $80,000 Colombian pesos (Approximately 22 US dollars) as an incentive if they can get 50 rides in seven days. This association is crucial for the governance structures that are formed in the online community, as the security guards are not members of the group, but certainly articulate within its structures and have direct communication with the administrators.

There is also evidence in this online community that the group has structured itself geographically to divide the areas of coverage in the city. This is to avoid direct competition between members and to increase the scope of possible users, as well as daily earnings. Geographical divisions are assigned by selection of the drivers, or if that is not accommodating, by a draw of drivers and locations. It should be noted that these allocations are not permanent.

As was stated by one of the managers of the Zello channel (El País, 2018):“We divide the city so that when a client requests the service, we can supply it in the shortest possible time and thus compete face to face with taxis and Ubers……In the south of the city for example we have a group of 50 partners dedicated to just four neighborhoods, and then another group for the Universities”– Miguel (Manager – name changed for anonymity).

Considering all the above-mentioned elements, and the nature of rule and decision-making in this online community, we could define this governance structure as a democratic entity of self-interested individuals with external allies. There is also a reliance on the mutually accorded decision of territorial divide. This allocation into democratic decision is very relevant here, as we could easily adapt the framework of platform cooperativism Solel (2019, 259) into it.

Ownership of this online community its allocated to their members and administrators alike, and the profits are destined to both the individual driver, but also by fee payment to the fund for advancing the community’s goals. Equally, decision-making is democratic, helped here again by the stable low scale of the group, if we are to compare it with the numbers of the case study in Bogotá.

The structure for this community-platform can be mapped by the diagram (Figure 4) in the concluding thoughts.

On legitimacy among members and administrators, it is interesting to engage with an element which emerged in one of the ride-conversations in Cali. One driver named Mauricio (named changed for anonymity) has a view on the legality and legitimacy of belonging to the group, which sheds light on the governance of the community but also its perception to members:“This is not a platform that has all the problems of Uber and its “friends”…We don’t have all those problems that other drivers have with the dynamic rates, and the commission payments……Besides, we are not giving money to the companies from abroad, this is all for ourselves. We came together to work, and this is different from Uber and its legal problems, we are not illegal.”

This perception, which is no doubt wrong, as individually providing transportation services for a profit in Colombia is still illegal, do attest however to the nature of belonging of the drivers and their interest in working in this online community. A sense of legitimacy is added by removing the corporative element of multinational platforms such as Uber, and embracing the ideas of locality, nationality, and work and dignity.

Community building is perceived as important in the legitimacy of “Los Sellos”, but the access to work and the ability to use this online community as a leverage mechanism to be able to receive economic gain is what assures its permanence. Linked to this is that the structures of the community and the role of the administrators is not put into doubt.

Drivers agree that the submission to vote on the original governance decisions, including the functioning of the collaborative fund, rates, and the association with security guards, kept them “at peace” with the way the community is organized. Moreover, drivers are also happy with the arrangement in which, different to what happens in the previous case study, administrators do not define centralized rates. Each member has a “Taximetro” app, easily downloadable from the online stores, then a daily rate per distance/time is suggested by administrators, but drivers are free to modify them and lower the price if they want to be more competitive externally (in relation to other drivers on other platforms).

Elements of free association and participation on decision-making, which includes both the original decisions and the daily suggestion of rates in the Zello group, leads to a smooth acceptance of the authority of the administrators. Interests are still cohesive as each individual driver offers their position and the community acts as an advantage mechanism.

Conflicts haven’t emerged as it is not a standardized organization; it may emerge in the future with their platformization – but is not a union, not a guild, not a company, but instead is an association of individuals with a specific purpose who have created other “services” and “benefits” for themselves. However, the democratic characteristic of decision-making in this online community does not eliminate issues of accountability in the organization. There are problematic aspects which are hidden in the acceptance of the governance structure. These are problems located in the lack of mechanisms for conflict resolution inside the community, and especially in the unbalanced power that the patrons (owners of more than one vehicle, who have people working for them) have over other drivers.

Equally, it is interesting to ask here if the decision-making even is democratic, and is not affected by the imposition of the administrators’ ideas, position in the hierarchy, and agency. That is, administrators as founders could enjoy a tacit advantage as the “creators” of the idea, as the articulators of the governance structures, as those with the association with security guards, and as those who manage the collaborative fund.

I was not able to find evidence among the members of mechanisms in which they could propose new ways in which the community could work and submit it for a vote by the group. Moreover, there is no evidence that the collaborative fund has some sort of audit regarding its use beyond the administrators. Even if there are no traces of corruption, visible in complaints by community members for example, it could be argued that the managing of monetary resources in many cases can lead to some level of embezzlement.

Nevertheless, there is a clear element of trust between members that is strengthened by the reduced amount of people in the online community, and the vetted association of any new driver. For the time being, this community of “Los Sellos”, in a similar fashion to the case of “Driver’s Club Bogotá”, still enjoys an inertia as its growth is not planned, and informal trust mechanisms are preserved. The community works because of its previous arrangements and grows according to an incremental process. However, if the community were to grow far beyond its inception, I argue that problems of corruption or power dynamics could easily emerge.

Colombia and Latin America have a context where institutions do not perform as expected because laws, regulations, and organized governance generally does not apply as is intended. There is a process among the population of diminished trust in the government’s functions and its institutions. However, there is also a cultural phenomenon of trust-building and organization between the population Rosario Maritza (2017, 5–6), which can easily be classified as trust between peers if it were to be analyzed under a framework of the literature related to the organizations evolving from platforms in the region.

Trust between peers in Latin America is built by citizens in a process of collective action that demonstrates the organizational capacity of individuals with a common goal. This collaboration is in most cases public, spontaneous, and non-recurrent (Rosario Maritza, 2017, 6). It is this trust that is behind the development of online communities in Latin America and Colombia, and it is easily detected in the language that is used by the members of the online communities in their social media interactions, but is also more than evident in their willingness to associate. Furthermore, it is evidenced in their acceptance to rescind the management of the monetary resources of the community (in the case of Los Sellos).

Novel and heterodox governance models emerging in the studied online communities are one of the multiple outcomes that digital platforms have had on social interactions in the Global South. As developed previously, I argue that the study of these outcomes and implications in contexts where the level of institutionalization is low and property rights are not well defined (i.e., countries in the Global South) has been lacking in the literature so far. However, having the opportunity to address this issue and investigate “platformed” communities in cities of the Global South helps to respond to a growing call for exploring new avenues of research for “southern” platforms (Koskinen et al., 2019).

Theorizing the impact of platforms in Colombia and the evolution of peer governance mechanisms is an issue that cannot be fully understood without new framing as to the nuances of both southern practices and the impact of platforms. Platforms in the Global South are challenging to study due to the lack of conceptual definitions and their spread, but most of all due to their intertwined nature with pre-existing institutions (Koskinen et al., 2019). There is a phenomenon of shared space between platform technology and societal structures, such as informality and peer intermediation, and this has meant platforms in southern contexts remain largely understudied.

As described by Bhan (2019, p. 5):“One way to conceptualize a vocabulary of Southern urban practice, then, is to start from particular empirical configurations of core urban systems -land, infrastructure, economy, governance, and cultural systems-in a particular set of cities’.

The practices of the studied online communities-platforms are itinerant, informal, and surpass formal structures of transport no matter the vehicle, while also promoting the agency of its users. “Platforms” or “Online-communities-platforms” in this article have therefore that point of reference in their theorization, framing an ecosystem developed by means of platforms, and that with technological mediation, enables the agency of users and creates new institutions, while de-institutionalizing others.

This analysis of de-institutionalization or institutionalization is a nuanced way to study how platforms in the Global North differ from those in the south. The software and transaction characteristics may be the same, as well as their developmental nature, but platforms operating in the ‘south’ add an element of institutional agency by operating in informal settings. Thriving on a void of informal practices, platforms transform into the building bricks and cement for the creation of new organizational forms and institutions that cannot be explained by forcing conceptualizations applicable to the ‘Global North’.

The most interesting implications of how platforms in the south differ from the north are in their institutional implications and their socio-technical nature (Koskinen et al., 2019, p. 325). Cases like the Mushikashika in Africa (Dumba, 2017) or Go-Jek in Indonesia (Prananda et al., 2020) are examples of the effect of platforms in urban institutions. These examples cannot be understood solely by relying on the technological but must be engaged with in socio-technical and institutional considerations of complexities such as informality.

In this article, the study of the “Driver’s Club Bogotá” and “Los Sellos” online communities showed how, in the process of creating “platforms”, innovative forms of organization emerged out of a bricolage of different software and hardware. In a process that could replicate “co-optation” mechanisms theorized in the “Möbius Organizational Form” (Watkins and Stark, 2018), but with its differences for the studied context, as these online-communities are not firms or formal organizations, but rather ad-hoc groups with their alternative and particular “southern” processes.

As I discussed in the two studied cases, it is difficult to classify the nature of organizational models emerging from these online communities.

These communities have elements of governance that exist in a gray space between extractive platform economy, heterodox sharing economies, and democratic platform cooperativism. In terms of structures and hierarchies, I observed that managers, as holders of the “founder” positions at the top and “owners” of the communities, are deemed to protect the integrity of the system, and more importantly decide on its rules. Rules that, even if submitted to democratic decision as was the case of “Los Sellos”, do not allow members a participation in their creation.

This clearly does not work in favor of the construction of democratic structures where interdependence is the main rule of interaction. It is important to question then whether those managers or leaders have a power of coercion against individual actors, which in this case I argue to be possible. The ability to create rules and the position in which managers are located as the “creators” of the online community gives them a leverage, and forces members into an “expected to comply” behavior.

I also observed a smooth construction of organization models, based on strong community ties, internal trust, and a sense of cohesiveness against a context that its hostile. These online communities-platforms are showing the strength of community building and designing simple but sophisticated and efficient models of organization. These models, however, are not exempt from problematic aspects regarding the lack of extended democratic models and certain levels of authoritarianism and corruption that may emerge from a lack of direct accountability and the management of monetary resources.

In any case, the characteristics of their internal functioning and the apparent smoothness and lack of conflict in which these communities-platforms developed refers to new questions and subjects that ought to be included in the theory of governance in online communities. Still left to discuss are new forms of accountability, in which trust and community links, together with individual interest of the members, act as many “eyes” on the processes and behavior of the managers. We could argue that these “benevolent dictators” at the top of hierarchies have a position within their communities out of meritocracy, and that this is not just upheld but preferred by the members. We could even state that governance structures, ownership, and democratic decision-making are more fluid than what is expected in the theory, and that maybe we cannot design the governance models for online communities but learn from their incrementalism and flexibility.

All the above calls for more research of peer governance in online communities, especially in the Global South, to evaluate if the thoughts and conclusions I am proposing here can be observed in other similar cases. This should be done through contexts where these types of flexible organizations are giving solutions that “designed” ones cannot.

What is written and what is real.

The use of theoretical rather than legal or policy terminologies for platformed “sharing” or “cooperativism” refers here to the evolving nature of platform economies and organizations. Coming from an observation on how that what is written, regulated, or codified as legal does not represent the evolution of society, especially in contexts of the south.

Latin America is an excessively “legalized” and “politicized” region. There is an idea in this region that the great social transformations come from the political arena, with a hidden underestimation of the role of the individual and their private initiatives in the achievement of those transformations. I argue here that it is inherent to Latin American societies and their evolution to believe too much in the written law and the value of its inception.

Latin Americans tend to believe that the world evolves as it is described in the written law and regulations, or worse, that it should be this way. This is enough in this case to put something in writing for it to be published and fulfilled, thus becoming a “reality”. This of course is not the case and has never been in the evolution of societies in this region, nor in the entire Global South. The idea behind the promulgation of legal definitions and stringent regulations vs. what ends up happening is represented in a typical Colombian idiom which perfectly describes the situation: “Se acata, pero no se cumple” in Spanish, which means “It is complied with, but not fulfilled”.

For the case of the studied online communities, I must insist here in the argument that the classifications pertinent to organizational forms and theory of the firm should not be de-contextually applied to what it is observed in the Global South. Much less if we are to consider the evolution of platform organization which is relatively new, with its nuances difficult to define at such an early stage.

Therefore, an observation and development of new interpretations out of practices is more useful to structure the hypothesis of a second or ‘southern’ generation of cooperative or mutualist platforms. This should be a theorization which responds to the everyday activities and strategies of people and that can also be harnessed for the implementation of better policies that do not end up simply as dead words written on paper.

By using software bricolage of WhatsApp, Zello, and other platforms, drivers of the online communities unified to defend themselves against insecurity on the streets and to improve their work conditions. However, they also united against both a government that has not been able to cope with the nature of platforms, and corporate structures such as multinational platforms that are exploiting them. I argue here then that recognizing flexible and incrementally structured organizations, with different forms of accountability built on trust and individual interest, can be good for an institutional ecosystem that has proven incapable to provide alternatives of growth.