94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 25 February 2025

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1553580

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvancing Equity: Exploring EDI in Higher Education InstitutesView all 14 articles

Despite the increasing number of racially and ethnically minoritized (REM) individuals earning PhDs and the substantial investment in diversity initiatives within higher education, the relative lack of diversity among faculty in tenure-track positions reveals a persistent systemic challenge. This study used an adaptation of the Community Readiness Tool to evaluate readiness for faculty diversification efforts in five biomedical departments. Interviews with 31 key informants were transcribed and coded manually and using NVIVO 12 in order to assign scores to each department in the six domains of readiness. The results revealed no meaningful differences in overall scores across institutional types, but did show differences within specific domains of readiness. These findings indicate that readiness is multi-faceted and academic departments can benefit by identifying priority areas in need of additional faculty buy-in and resources to enhance the success of diversification efforts.

Increasing faculty diversity in the biomedical sciences holds immense promise for fostering equitable representation, enriching the STEM research environment, and driving groundbreaking discoveries. There is a persistent lack of diversity among academic faculty (Hofstra et al., 2022; Matias et al., 2022) and well-documented benefits of diversification (Llamas et al., 2021). A diverse faculty enhances students’ experiences by challenging them to think critically about knowledge production and to adopt a more inclusive perspective. Faculty diversity also enriches the curriculum and faculty discussions (Gasman, 2016). Diversifying STEM faculty is not just a moral imperative; it is a strategic investment in the future of research. Diversity is a catalyst for innovation, bringing diverse minds together to ask new questions and drive groundbreaking discoveries (Hewlett et al., 2013; Hofstra et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2020).

While “diversity” can broadly be defined as representation of “various social identities, experiences, and perspectives” (American Psychological Association, 2021), we focus on racial and ethnic diversity in higher education and particularly in the biomedical sciences. This decision was informed by several considerations, including the widespread use and availability of robust demographic data and the reality that a lack of racial and ethnic diversity serves as an indicator of broader issues that may impact other dimensions of diversity (such as differential opportunities, barriers to access, and exclusionary practices).

Institutional efforts often misdiagnose the causes behind lagging faculty diversity, perpetuating the “pipeline fallacy” that increasing the number of racially and ethnically minoritized (REM) scholars earning PhDs will automatically result in a more diverse professoriate (Boyle et al., 2020). While expanding the pool of REM postdoctoral scholars is part of the solution (Patt et al., 2022), relying solely on this approach risks perpetuating structural inequities due to systemic barriers embedded within academia. In fact, the pool of REM PhD graduates in biomedical sciences has grown, yet their transition into faculty roles has not kept pace (Gibbs et al., 2014). This disconnect underscores the limitations of focusing narrowly on numerical representation without considering broader structural transformation.

Achieving meaningful demographic change in the professoriate requires a paradigm shift underpinned by an equity mindset that prioritizes structural transformation, acknowledging that institutional factors, not individual shortcomings, are the root cause of barriers to REM scholars’ advancement. We embrace the definition of equity as “an ongoing process of assessing needs, correcting historical inequalities, and creating conditions for optimal outcomes by members of all social identity groups” (American Psychological Association, 2021). Equity in this frame recognizes differences in the starting conditions and subsequent needs of some to reach success, as opposed to assuming an equal footing from the onset. From this perspective, institutions must critically examine and reform hiring practices, prioritize retention as much as recruitment, redefine exclusionary metrics of faculty “fit,” and actively cultivate environments where REM scholars can thrive (Griffin, 2020; White-Lewis, 2020).

Patt et al. (2022) argue for the importance of addressing barriers at the postdoctoral stage, as demographic data on PhD graduates obscures the experiences of those employed as postdocs and the ongoing challenges of diversifying faculty, particularly at research-intensive institutions. Postdoctoral scholar-to-faculty conversion programs have emerged as a promising “grow-your-own” strategy to connect postdocs to tenure-track positions (Culpepper et al., 2021). However, the role of institutional context in the success of such programs has not been systematically evaluated.

It is crucial to assess the environments where future faculty will work. Without addressing departmental readiness to support diversity initiatives, any gains from diversification programs risk being undermined by unwelcoming or inequitable climates, perpetuating the “revolving door” phenomenon, with diverse scholars leaving due to unwelcoming, non-inclusive environments (Griffin, 2020, p. 323). We adopted the APA definition of inclusion as “an environment that offers affirmation, celebration, and appreciation of different approaches, styles, perspectives, and experiences, thus allowing all individuals to express their whole selves (and all their identities) and to demonstrate their strengths and capacity” (American Psychological Association, 2021). In this article, we provide a model for assessing departmental readiness for diversity initiatives, using it to evaluate the conditions in five biomedical departments and identifying barriers that may hinder success.

Institutional transformation aimed at successful faculty diversification requires changes in institutional goals, policies, support, and rewards (Campbell et al., 2009; Hrabowski et al., 2011; Newman, 2011; O’Rourke, 2008; Wunsch and Chattergy, 1991). Smith et al. (2004) emphasize the importance of strategic interventions to enhance faculty diversity, such as special-hire opportunities, diversity indicators in job descriptions, search waivers, spousal hires, expanded job descriptions, modified search requirements, shortened processes, cluster hiring, and out-of-cycle hiring. These strategies, when applied equitably and in compliance with hiring regulations, can contribute to creating a more inclusive and representative faculty.

However, Sensoy and DiAngelo (2017, p. 560) note that scholars including Ahmed (2012), Brayboy (2003), and Henry et al. (2017) identify three key challenges with university-wide diversity initiatives and policies at historically white colleges and universities (HWCUs). First, HWCUs often treat diversity as a standalone issue focused on the inclusion of students and faculty of color without addressing the institution’s deeply ingrained whiteness in its policies, practices, and structures. Second, the responsibility for implementing and sustaining these initiatives disproportionately falls on junior faculty of color and the small number of senior faculty of color, burdening them with additional labor that often goes unrecognized or unrewarded. Finally, these initiatives frequently obscure the pervasive “grammar of Whiteness” (Bonilla-Silva, 2011), normalizing racialized practices and discourses that marginalize faculty of color while leaving the underlying logics of whiteness unexamined and unchallenged.

Unfortunately, when planning diversity efforts, the institutional readiness for such change is often overlooked or overestimated because diversity initiatives are implemented in individual departments rather than entire institutions. White-Lewis (2022, p. 338) argues that “Neglecting departmental contexts fails to explain how all academic units bound by the same university policies…reach such different outcomes, even when comparing disciplines with similar levels of racial diversity.” Rather than institutional readiness, Lee et al. (2007) favor focusing on department readiness because the academic department is central to a university’s hierarchy and bridges institutional priorities.

Community readiness describes the degree to which a community is prepared for change in order to implement an intervention focused on an issue of interest (Castañeda et al., 2012; Plested et al., 2006). Past research on community and organizational readiness for change used a number of assessment tools to evaluate readiness (Castañeda et al., 2012; Edwards et al., 2000; Weiner et al., 2008). The Community Readiness Tool (CRT), based on the Community Readiness Model (CRM) (Donnermeyer et al., 1997), is the most widely used instrument for measuring readiness to tackle an issue (Edwards et al., 2000). A review of use of the CRT (Kellner et al., 2023, p. 24) found that while most studies (55%) defined community based on geography, researchers also defined the concept to include institutions (27%), ethnicity (18%), identity (8%), and LGBTQ+ communities (9%). The CRM emphasizes the importance of aligning interventions with a community’s stage of readiness to prevent misaligned efforts that may not gain traction. Communities using the CRM to holistically assess readiness experience higher levels of implementation success and stakeholder involvement compared with other communities (Thurman et al., 2007).

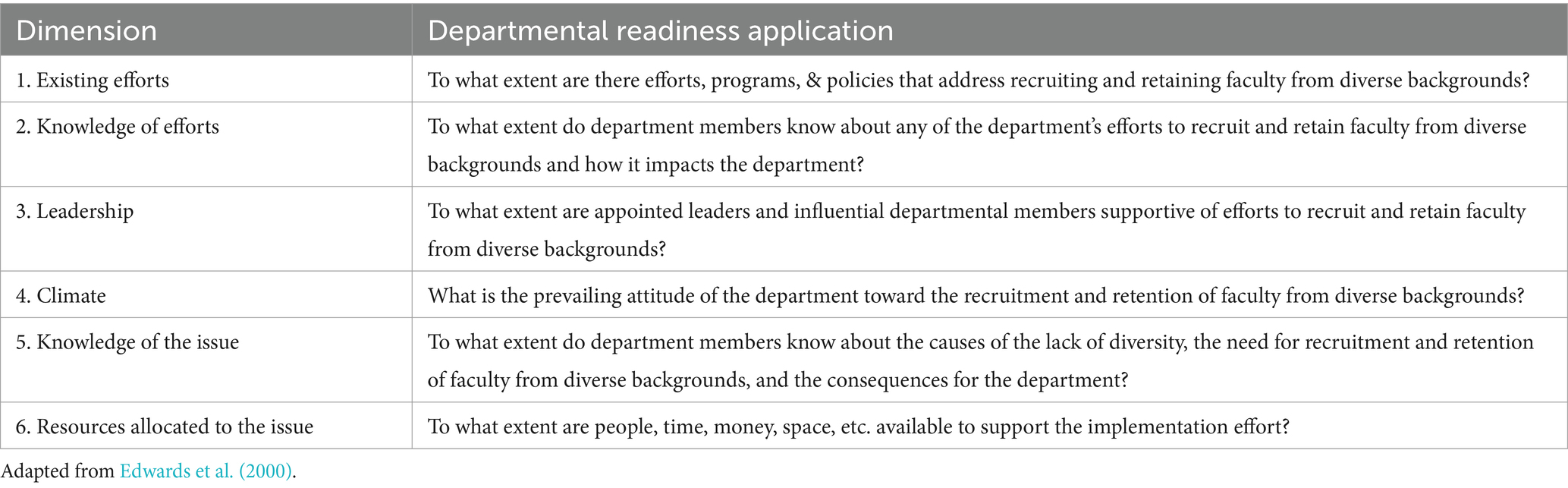

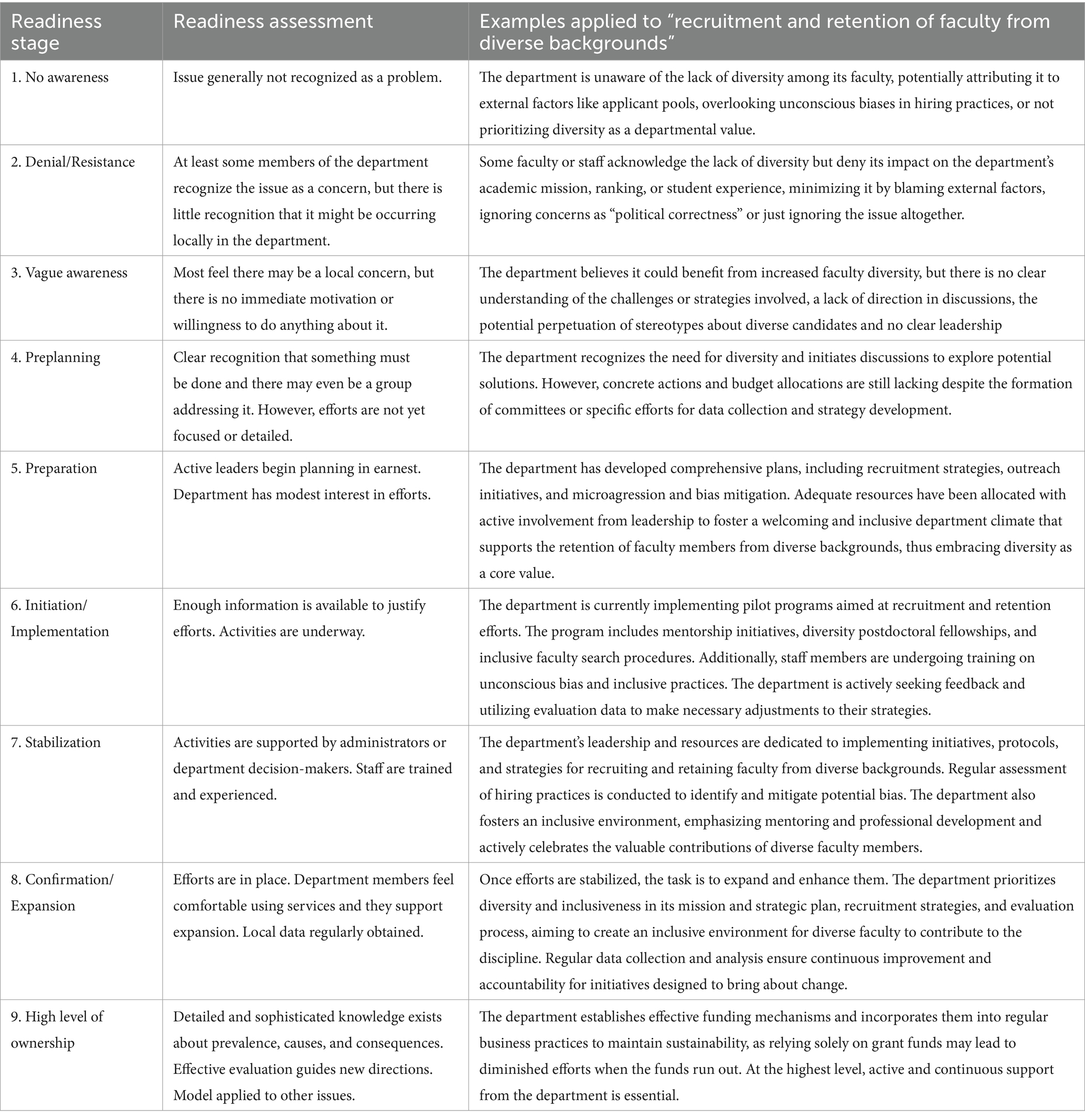

A readiness assessment involves measurements in six dimensions (existing efforts, knowledge of existing efforts, leadership, community attitudes/climate, knowledge about the issue, and resources). The nine levels of readiness are no awareness, denial/resistance, vague awareness, preplanning, preparation, initiation/implementation, stabilization, confirmation/expansion, and community ownership (Edwards et al., 2000; Table 1).

Table 1. The table presents the six dimensions of readiness and how they were applied to departmental readiness to support a diversity initiative aimed at faculty.

Considering faculty diversification efforts, Griffin (2020) asserts that it is essential to focus on faculty recruitment and hiring processes, particularly for full-time and tenure-track positions, as well as the cultural and environmental aspects of their workplaces (p. 301). Biased practices based on idiosyncratic preferences have been observed in faculty hiring committees (White-Lewis, 2020), and even when REM scholars secure faculty positions, structural challenges can limit their ability to thrive. They may face unwelcoming or hostile academic environments; microaggressions, lack of mentorship, and the devaluation of research on race or ethnicity can create barriers to their retention, advancement, and long-term success (Culpepper et al., 2021). And according to Gasman (2016), excuses and resistance to revising or rethinking policies are common in the academy: “…faculty will bend rules, knock down walls, and build bridges to hire those they really want (often white colleagues) but when it comes to hiring faculty of color, they have to ‘play by the rules’ and get angry when any exceptions are made. Let me tell you a secret—exceptions are made for white people constantly in the academy; exceptions are the rule in academe” (p. 206).

Biases and structural inequities in recruiting and hiring are exacerbated for postdoctoral positions, a key step toward faculty roles in many disciplines. Patt et al. (2022) describe the postdoctoral career stage as a “closed system” akin to an “old boys network” (p. 3). Relying on limited networks exacerbates existing racial and gender disparities (Herschberg et al., 2018; Patt et al., 2022). Searches for postdoc positions are often based on personal networks with little institutional oversight, and many openings are never publicly advertised (Herschberg et al., 2018; McGlynn, 2019; Patt et al., 2022). This informal process makes it difficult for REM candidates to learn about opportunities, let alone secure them. Principal investigators, who hold considerable power in hiring postdocs, are predominantly white and male (Yosso et al., 2009) and often have racialized professional networks. The resulting recruitment process favors candidates within these networks, effectively sidelining qualified REM scholars who lack network connections. The lack of transparency in postdoctoral researcher hiring makes it difficult to pinpoint where interventions are needed to promote equitable practices and the diversification of the STEM workforce (Herschberg et al., 2018; Heirwegh et al., 2024; McGlynn, 2019; Culpepper et al., 2021). Disrupting existing processes will require introducing alternative pathways into the professoriate (Boyle et al., 2020; Gutiérrez y Muhs et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2023; Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017).

Academic departments are a type of community characterized by a collective of individuals who, despite diverse perspectives, share mutual interests, interact regularly, and cultivate a sense of belonging and group identity, particularly during the hiring season. During searches, faculty collaboratively navigate decisions that shape the department’s future, reflecting shared values and priorities. Moreover, academic departments are where hiring decisions actually occur. As Boyle et al. (2020) explain, “The general lack of intentionality in the recruitment of historically underrepresented minorities speaks to the rift that exists between the communication of underrepresentation as a national problem and its treatment at the department, where actual progress needs to be made” (p. 20). Departments can play a crucial role in reshaping hiring processes to foster—or obstruct—faculty diversity (White-Lewis, 2021). Using the campus as a broad unit of analysis may overlook differences in readiness between departments. Some departments may be ready to implement diversity initiatives, while others may not, making campus-wide readiness assessments an ineffective measure. Academic departments hold the reins of change, exerting a profound influence on the composition of the faculty body (Edwards, 1999; Hobbs and Anderson, 1971; Ryan, 1972).

Diversity initiatives aimed at influencing faculty hiring, including postdoc conversion programs, can be complex and challenging to implement. A department may have to modify its hiring procedures, which some members may perceive as a threat to departmental autonomy. Given these dynamics, we argue for shifting focus from applicants to the actions, willingness, and commitment of departments to drive meaningful change. Assessing readiness to make those changes is an essential step that can assist leaders in designing effective strategies. This study presents the results of one such departmental assessment; while the specific diversity initiative in question was a postdoc conversion program (Culpepper et al., 2021), our findings have implications for successful diversification efforts more broadly.

The AGEP PROMISE Academy Alliance (APAA) is an NSF-funded initiative to develop and study a model for leveraging a state university system structure to diversify faculty. Five public institutions began collaborating in 2018 to implement a faculty diversity effort centered on postdoctoral conversion to tenure-track faculty positions. In 2020, the APAA leadership team and its external advisory board discussed the important but unexamined role of the departmental environment into which REM postdocs would be hired and developed for potential conversion into faculty roles. Given the research demonstrating how bias, climate, and microaggressions–both personal and structural–discourage REM scholars from remaining in the academy (Allen and Stewart, 2022; Rodrıguez et al., 2014; Turner et al., 1999), we wanted to determine whether departments were safe and supportive environments for REM candidates.

This study builds on an exploratory case study of a single biomedical department’s readiness to adopt a faculty diversity initiative (Carter-Veale et al., 2024). We extend the prior work to examine the readiness of biomedical departments at four additional institutions in the same mid-Atlantic state higher education system. The departments are located in different types of institutions: two research-intensive universities, one mid-size doctoral university with high research activity, and two primarily undergraduate, regional comprehensive institutions. We address two key questions: What is the level of readiness in each department to recruit and retain faculty from diverse backgrounds? And does the level of readiness differ depending on the type of university?

We conducted a cross-sectional study with a mixed-methods design. We adapted the Community Readiness Model and modified the second edition of the CRT (Oetting et al., 2014; Michaels, 1983; Slater et al., 2005) to create a Departmental Readiness Tool. While previous applications of the CRM to higher education defined the university campus as the community (Edwards et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2016; Kelly and Stanley, 2014; Wasco and Zadnik, 2013; Wichmann et al., 2020), we defined a community (our unit of analysis) as a biomedical department taking part in the APAA project and our issue as “the recruitment and retention of faculty from diverse backgrounds.” Readiness was defined as a department’s willingness and commitment to change in order to recruit and retain faculty from diverse backgrounds.

The study was approved by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County Institutional Review Board. Interviewees provided their written informed consent to participate.

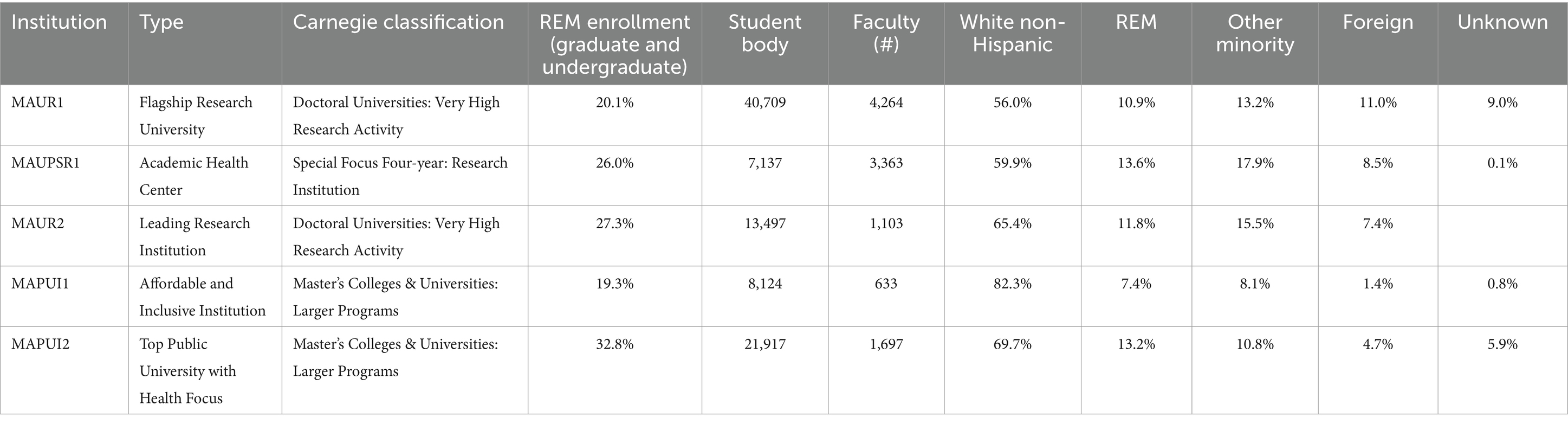

The setting was five biomedical departments in the Mid-Atlantic University State System, which serves over 150,000 students at more than 10 institutions, multiple regional centers, and a system office. Each institution operates independently under a president and provost, while a chancellor guides system-wide strategies. Table 2 presents key institutional data.

Table 2. The table presents key data on the institutions that are the locations of the five biomedical departments in the study.

Mid-Atlantic R1 (MAUR1), the flagship institution in the system, is a top public research university. Among a student body of over 40,000, 20.1% are from REM groups, while only 10.9% of the 4,000+ faculty members identify as REM individuals. Its six key informants consisted of one lecturer, three full professors (including the department chair), and two assistant professors, with a gender composition of five women and one man.

Mid-Atlantic Professional School R1 (MAUPSR1), specializing in public health, law, and human services, operates as an academic health center with a strong emphasis on biomedical research and clinical care. It enrolls over 7,000 students and employs over 3,000 faculty. REM students are 26.0% of the population, while REM faculty are 13.6% of the professoriate. Participants included one associate professor and five full professors (the department chair and co-chair among them), with a gender composition of four men and two women.

Mid-Atlantic R2 (MAUR2) is a mid-sized research university. It enrolls over 13,000 students (27.3% REM) and has over 1,000 faculty members (11.8% REM). Participants included two associate professors and four full professors (including the department chair and co-chair), consisting of five women and one man.

Mid-Atlantic Primarily Undergraduate Institution 1 (MAPUI1) is a comprehensive regional university enrolling over 8,000 students and employing 600+ faculty. REM students are 19.3% of the population, while REM individuals make up 7.4% of faculty. Participants were two associate professors and four full professors, including the department chair and co-chair; the gender breakdown was two women and four men.

Mid-Atlantic Primarily Undergraduate Institution 2 (MAPUI2) is also a regional comprehensive institution, specializing in health professions and aspiring to achieve R-2 Carnegie status. It enrolls over 21,000 students (32.8% REM) and has over 1,500 faculty (13.2% REM). Participants included one associate professor and six full professors (including the department chair and co-chair), consisting of six women and one man.

The second edition of the CRT (Oetting et al., 2014) recommends interviewing six to eight key informants per community. We completed six or seven interviews in each department, resulting in 31 total interviews. Key informants were recommended by APAA leadership team representatives from each campus, as they were familiar with the departments where the initiative had been implemented. They identified members of their institution’s biomedical department who had significant knowledge of the department’s dynamics and a history of departmental service. We used a combination of purposive and convenience sampling methods, considering factors such as faculty rank and service roles (e.g., previous service on search committees), gender, and leadership positions. We attempted to capture a comprehensive range of perspectives on the department’s readiness for recruiting and retaining faculty from diverse backgrounds. We prioritized participant autonomy, confidentiality, and anonymity.

Racial diversity across departments was minimal, with each department represented by primarily white faculty and one or two members who identified as racially/ethnically marginalized. This pattern allowed us to look closely at how mostly non-REM individuals interpret and react to departmental diversity initiatives.

We used the 40 questions in the Community Readiness Tool (CRT) handbook (Oetting et al., 2014; Plested et al., 2016) to assess readiness in six dimensions: existing efforts, knowledge of efforts, leadership, climate, knowledge of the issue, and resources allocated to the issue (Supplementary Appendix). Kelly and Stanley (2014) provide details and specific steps for conducting a readiness assessment. Two APAA leadership team members independently adapted the questions to make them relevant to the research topic and then worked together to arrive at a consensus. The modified questions were pretested with an APAA leadership team member who gave feedback on wording and clarity.

Scholars studying race and ethnicity concur that racial issues are typically “hot button” topics in the United States, causing people of color to become vocally angry and white people to become silent, defiant, or disconnected (Singleton and Hays, 2008). Kaplowitz et al. (2019) suggest that “an important part of the role of the facilitator in dialogues is to ensure that societal inequality is not re-enacted within the dialogue space” (p. 47). Our internal evaluator, an expert in race and ethnicity, recognized the complex power dynamics and racialized social structures inherent in interviewing predominantly non-REM key informants about faculty diversification and recommended employing an external interviewer to mitigate potential biases linked to institutional affiliation and perceived insider-outsider status. This approach aligns with the assertion by Merrıam (2009) that external interviewers can enhance data reliability by creating the social distance necessary for authentic participant engagement. To foster rapport and facilitate candid, unguarded responses, we recruited an experienced interviewer whose racial and gender identity aligned with the majority of our participants. Virtual video interviews occurred in July and August 2021 and were recorded, with handwritten notes taken by a consultant, a middle-aged white man who was a former academic. Participants were instructed to answer based on their perception of what department members think and know, not their own personal beliefs. A professional transcription firm transcribed the interviews, and the transcriptions were verified by the research team.

The internal evaluator and two graduate assistants independently reviewed all transcripts and followed the standard CRT scoring protocol and procedures (Oetting et al., 2014). Each of the six dimensions was rated numerically, with one indicating “no awareness” and nine indicating “high level of departmental ownership.” According to the CRT handbook, when scores fall between two whole numbers, the prescribed procedure is to round down to the lower stage of readiness.

The exploratory data analysis involved two rounds of thematic analysis of the 31 interview transcripts. The first round consisted of manual analysis. We read the transcripts and listened to the interviews to check for transcription accuracy. The internal evaluator and a graduate assistant repeatedly read and coded each interview using a deductive approach, with predefined categories derived from the six dimensions of readiness. For the second round, we used NVIVO 12 software for coding. The internal evaluator and a second graduate assistant revisited the text multiple times to ensure consistent application of the coding scheme and to refine identification of relevant data segments. Table 3 summarizes the scoring rubric.

Table 3. The table presents the nine stages of readiness, a description of each readiness stage, and examples used for scoring interviews.

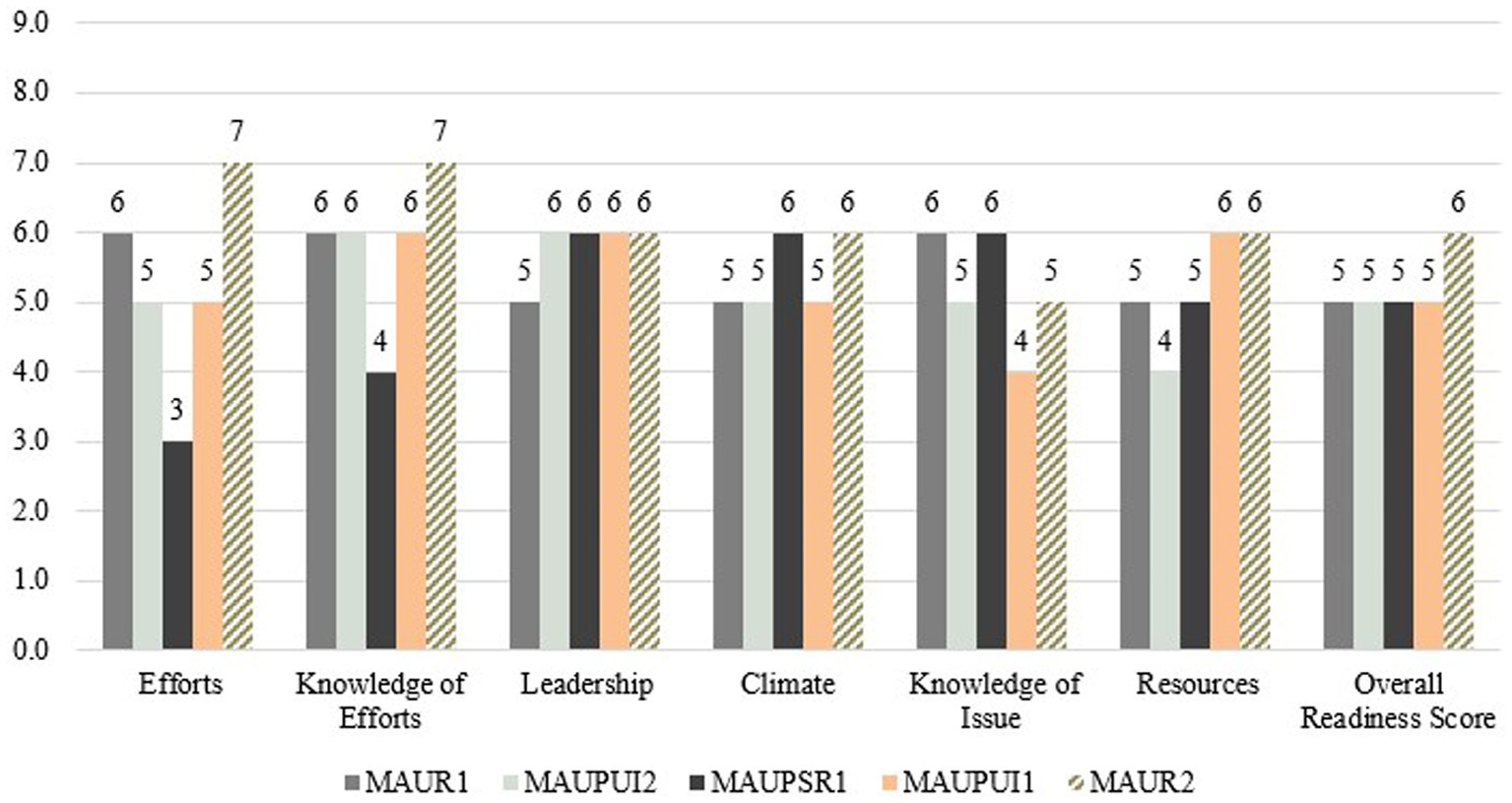

In this section, we present quantitative readiness scores for each department and comments from key informant interviews that highlight important themes. This approach contextualizes the numerical scores (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Department readiness scores (rounded down, as per the assessment protocol) for each dimension and overall.

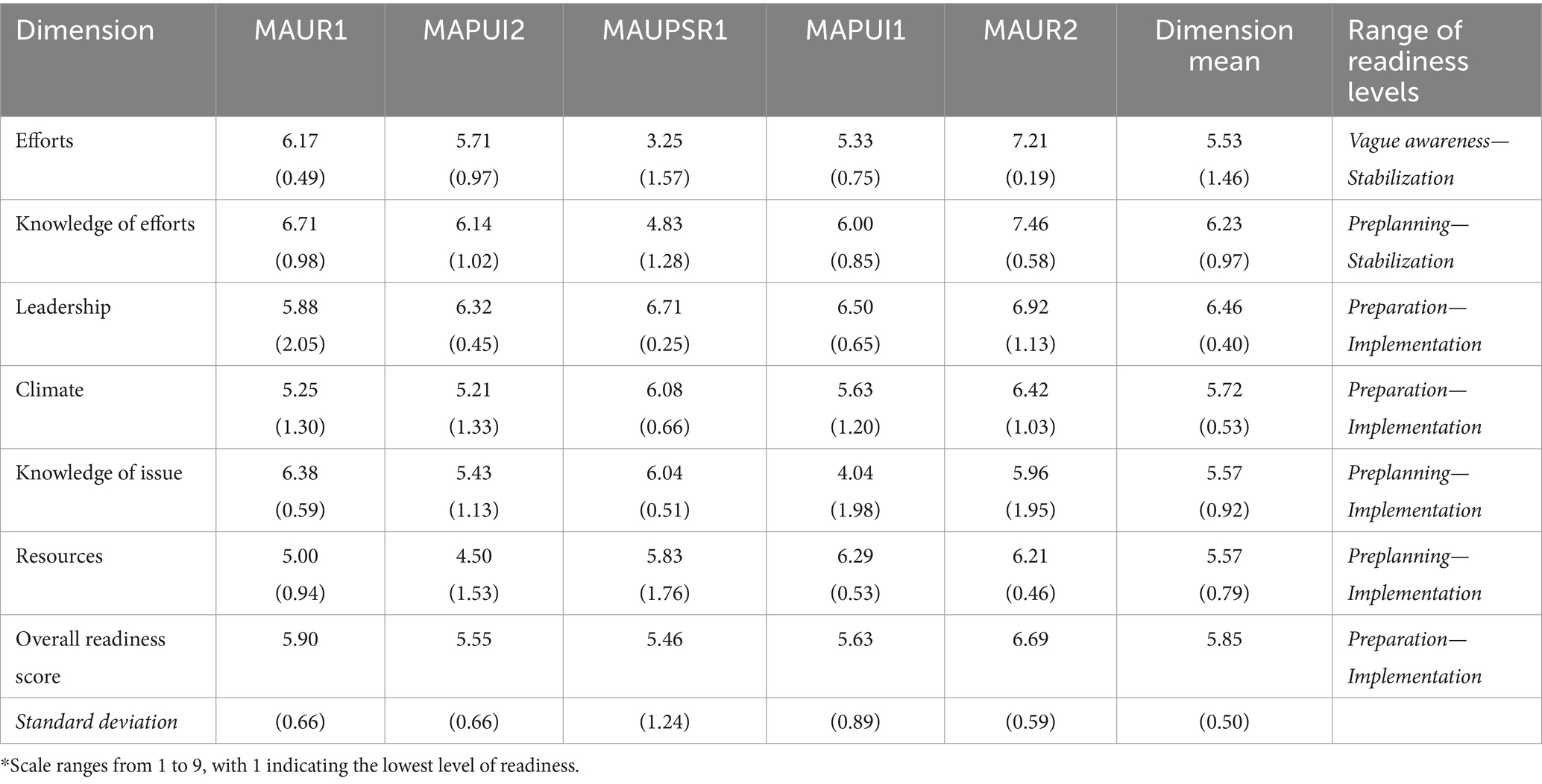

Table 4 shows the overall mean readiness scores and standard deviations for each department and their scores for each dimension of readiness. The assessment revealed little variation in overall readiness across the five departments, indicating that institutional type, by itself, is not a primary factor determining readiness for faculty diversity initiatives. The highest overall mean readiness score was M = 6.69 (SD 0.59) for MAUR2, placing it in the Initiation/Implementation stage. The other departments scored in the Preparation stage.

Table 4. The table presents the mean scores and standard deviations for each department on each dimension of readiness, as well as department overall scores.

In an academic community, there may be a tendency to interpret readiness scores as passing or failing “grades” rather than as a baseline level of readiness for an intervention. Instead of fixating on overall scores, it is more productive to focus on dimension scores to identify areas that warrant improvement. Our assessment found notable differences in readiness within dimensions, whether comparing departments on a dimension or looking at a single department across all dimensions.

Diversity efforts were broadly interpreted to include any program, workshop, policy, or training that directly or indirectly affects recruitment and retention of REM faculty, including the postdoctoral conversion initiative. This dimension evaluates how much department members know about programs already underway. ANOVA results (Table 5) indicate a statistically significant difference between departments (p < 0.001). MAUR2 (M = 7.21, SD 0.19) and MAUPSR1 (M = 3.25, SD 1.57) had the highest and lowest average scores, respectively, corresponding to the Stabilization and Vague Awareness stages. The two primarily undergraduate institutions, MAPUI2 (M = 5.71, SD 0.97) and MAPUI2 (M = 5.33, SD 0.75), had mean scores of 5 (Preparation stage), while MAUR1 (M = 6.17, SD 0.49) fell into the Implementation stage.

MAUPSR1 department members, at the Vague Awareness stage, showed limited recognition of existing faculty diversity efforts, with few respondents able to identify any initiatives. A faculty member mentioned that the department has “considerable efforts in pipeline programs for younger—for undergraduates, for high school students, even middle school students and getting them into science” but “there are no specific efforts in the department to recruit diverse faculty members.” In contrast, key informants at MAUR2, which fell into the Stabilization stage, could name and describe multiple, sustained diversity initiatives for students and faculty that had been in place for over 4 years, including “a Pre-professoriate program, APAA postdoctoral conversion program, implicit bias training, and an ADVANCE grant addressing gender diversity” mentioned by one person. Another key informant expressed commitment to diversity and STEM education “as indicated by our undergraduate and graduate programs and our faculty recruitment. We are just very aware of it and go out of our way to make sure that women and minorities are part of the shorter long list [of candidates].” MAUR2 did not reach the next stage of readiness because there was no evidence that they were developing new efforts based on evaluation data.

MAUR1 is at the Initiation/Implementation stage, indicating that efforts are underway but have been in place fewer than 4 years. Respondents describe some diversity efforts, such as “the presidential postdoctoral fellowship program, the McNair program, and a Diversity of Science Initiative.” MAUR1 is part of the President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, but this program focuses on placing postdocs in tenure-track positions at other institutions rather than diversifying their own faculty.

In some departments, the APAA postdoctoral conversion program was the sole effort identified by key informants as a faculty diversification initiative. Informants from other departments mentioned additional activities, such as anti-bias training and microaggression workshops, aimed at fostering a more inclusive environment. Members of MAUR1, MAPUI1, and MAPUI2 described various initiatives that, while not directly focused on recruiting diverse faculty, help create a more welcoming environment for both faculty and students. For example, a respondent at MAPUI2 mentioned their “Howard Hughes Medical Institute, in their Inclusive Excellence program, which is in science education, focused on cultural change, so creating more welcoming and inclusive STEM culture at the university level.” In that grant-funded project, “We also train faculty in cohorts, and those faculty go through implicit bias training. They learn about inclusive teaching practices. And as part of that training, they are talking about and thinking about diversity issues.” Initiatives with less formal structures targeting the departmental climate or extending social networks for hiring diverse candidates complement more structured efforts.

One MAPUI2 respondent pointed to specific actions such as recruitment and retention activities that the department actively engaged in:

We make a concerted effort to contact, for example, HBCUs and other minority-type institutions and networks in order to advertise these positions, don’t know if the department itself is aware of many of the other offices on campus that could help. But being somebody who is very involved in that on a personal level, I know who to reach out to, but I’m not sure how much of a departmental awareness of that there is. …. Prior to DEI discussion it has just been talk, action has occurred in the last 3 years. We have had initiated conversations with our diversity, equity, and inclusion offices [at MAPUI2] to simply ask what else we can do to improve not just recruitment, because I think recruitment, we’re actually pretty decent. It’s the retention and promotion part, I think that’s more difficult.

A key informant at MAUR1 described an additional strategy to make REM faculty more comfortable in the department:

Well, at our regular faculty meetings, because of concern that some faculty of color may feel uncomfortable speaking up publicly, we now have a middle person…So they could send a private chat to this spokesperson who is, I think the chair assigned, who is viewed as a neutral party and who pledges anonymity. And so, anyone at all who wants to make a comment to the group, instead of raising their hand, they could just send an anonymous chat to that person. And the spokesperson would say, I received…a comment in the anonymous text, someone wonders whether such and such.

The analysis of MAUPSR1’s diversity efforts indicates limited awareness of and action on faculty recruitment and retention, reflecting the Vague Awareness stage. Although no informants mentioned the department’s existing postdoc conversion program, two highlighted upcoming diversity initiatives, including a collaborative NIH FIRST grant application with their peer institution, MAUR2, which has the highest readiness score in this study. One MAUPSR1 respondent described the FIRST grant as “designed to help recruit individuals from diverse backgrounds. It is NIH FIRST program, which is the Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation, or something like that, which is a program designed to provide funding for recruitment at an institutional level, recruitment of multiple positions for individuals from diverse backgrounds who have made a commitment to improving diversity in environmental sciences.” Despite this initiative, several informants suggested that departmental efforts remain focused largely on student pipeline programs spanning middle school to graduate levels, with limited immediate strategies to recruit and retain diverse faculty in the department. One individual described current efforts:

Again, these are all to get underrepresented minority students into that graduate student pipeline, bring them onto campus, give them those exposures. And I think…the long-term goal is to get them into faculty positions, and I’ve had around eight, nine students go through …in…14 years. Three of them have been part of [MAUR2’s nationally prestigious] program or these other programs. And two of them have gone on to, one is [a] postdoc…[in] Vermont, and one is now a faculty member at Spelman College in Atlanta. So she is faculty. So I think the pipeline is working, I think the logic behind the pipeline is good…There really needs to be more opportunities. We’re trying at that level.

The emphasis on external placements reflects a broader commitment to faculty diversity but a lack of active efforts to address diversity deficits in their own faculty. This limited focus contributes to the department’s Vague Awareness score.

This dimension measures the extent to which individuals or groups understand the presence, scope, and purpose of initiatives aimed at recruiting and retaining faculty from diverse backgrounds. The interviews indicate that while some faculty are aware of diversity efforts, their understanding is often superficial or incomplete.

ANOVA results indicate a statistically significant difference across departments (p = 0.00). Given the lack of faculty diversity initiatives at MAUPSR1 described above, it is not surprising that it had the lowest mean score (M = 4.83, SD 1.28), falling into the Pre-planning stage. A MAUPSR1 respondent noted their lack of knowledge:

We are certainly aware of at least a small number of studies that show that increased diversity tends to lead to successful outcomes in the biomedical workforce. I think at least some of the faculty are aware of those sorts of driving forces behind the need to improve this….I would say that people are very aware that this is an important criterion. If you ask me about, are people aware of specific programs that are available, then I would say probably a few. I don’t know. I haven’t heard of any specific funding mechanisms or even initiatives, to be honest, for diverse faculty retention.

Another MAUPSR1 respondent attributed the department’s limited awareness of diversity efforts to its “large size” and the effects of the pandemic, noting that “there is not as much discussion…and so, that could lead to a lack of dissemination of the information.” However, another respondent disagreed, asserting that “there’s a lot of different ways to get the information if you want to get the information.” They pointed to multiple channels—new faculty orientation, regular faculty meetings, involvement in retention and training programs, and communication with the department chair—as ample avenues for staying informed about faculty diversity issues.

Three institutions, MAPUI1 (M = 6.00, SD 0.85), MAPUI2 (M = 6.14, SD 0.85), and MAUR1 (M = 6.71, SD 0.98) were at the Initiation/Implementation stage, while MAUR2 (M = 7.46, SD 0.58) scored at the Stabilization stage. Any stage above Initiation/Implementation suggests that the faculty can both identify an initiative by name, such as the Diversity Science Initiative introduced at MAUR1, and explain the benefits of the program. Referring to the APAA program, a respondent from MAPUI1 said:

I’m thinking that had there not been a [postdoc conversion] program, we would have just sort of continued the way that we always continued in the past. We would have – even though, like I say, I think diversity has always been something that has been on our mind, we didn’t really make any sort of formal move in that process other than, prior to the program, we would advertise for a faculty member and that would have to go through our diversity office at the university in terms of any kind of hiring.

Similarly, respondents at MAPUI2 mentioned that their inclusive hiring strategies are widely known within the department, even among those who may not actively engage in diversity initiatives. By expanding social networks and updating practices for advertising faculty positions, the department has increased awareness of their diversity efforts: “Even if they are not interested, they have heard of it. And they know that we are doing these efforts. To what level they are aware of where to go, and what to do and how much they want to be involved is a whole different kind of question, but at least they are aware of it.” This suggests that knowledge of these strategies has permeated departmental culture and communication channels, establishing diversity efforts as a shared knowledge base.

A common theme that emerged is that department members are generally more aware of diversity initiatives targeting REM students than those focused on faculty. Regarding searches, departments prioritize knowledge about recruiting faculty from diverse backgrounds, including through the APAA postdoc conversion program, emphasizing formal, de jure procedures to support equitable hiring. Although they have introduced new administrative procedures to support these goals, they still heavily rely on faculty members to publicize open positions through their personal and professional networks. Because networks often reflect existing racial patterns, de facto discrimination may persist without direct mitigation efforts. Department leaders typically communicate diversity initiatives through faculty meetings, emails, and specialized seminars with invited speakers. However, the effectiveness of communication depends on faculty attendance and active engagement, which can be inconsistent, limiting broader awareness and full participation in diversity-focused hiring initiatives.

Awareness of diversity efforts varied due to several factors, including misconceptions, communication practices, and faculty engagement. Some faculty may hold misunderstandings about the necessity of these initiatives, believing responsibility for recruitment lies elsewhere. Consistent and effective communication, such as regular updates in faculty meetings, can enhance awareness. Conversely, a lack of engagement or unclear messaging can lead to a disconnect.

MAUR1, MAUPSR1, and MAPUI2 have established effective communication channels for disseminating information about diversity initiatives. MAUR1 excels in engagement, with one informant noting, “Our chair talks about [diversity recruitment efforts] at our faculty meetings on a regular basis…So, I would say that would be the reason why [the majority of faculty are aware].” According to a respondent, MAPUI2 maintains consistent awareness as well: “We discuss faculty recruitment in our faculty meetings… the majority of the faculty know about the attempts at recruiting diverse faculty.”

All institutions have strengths and areas for improvement. For example, despite its effective communication channels, MAUR1 faces engagement challenges, as one informant remarked: “The pandemic wore on people’s memories… some of these things have sort of dropped off people’s radar.” MAUPSR1, a large department, faces differences in awareness; an informant stated, “I would think a small minority of the department faculty are aware of this new initiative.” At MAPUI2, a subset of faculty is informed, such that “even if they are not interested, they have heard of it… at least they are aware of it.” This highlights a critical gap between the existence of initiatives and faculty knowledge about them.

In this readiness dimension, we find that the challenge in advancing diversity initiatives in universities lies in the difference between recognition and understanding. While faculty may recognize the importance of diversity and the existence of related efforts, they often lack a deep understanding of the initiatives themselves, their goals, strategies, and broader impacts. This gap can prevent faculty from fully engaging with the initiatives, supporting them effectively, or contributing meaningfully to their success. Faculty participation may remain superficial or passive, rather than proactive and transformative.

Faculty engagement in diversity initiatives can be hindered by gaps in knowledge. At MAUPSR1, faculty members recognize the importance of diversity, but the depth of these efforts is not well understood. MAUPSR1 faculty members asserted, “Faculty diversity needs to reflect the diverse student body,” suggesting a shared understanding of diversity’s significance. At MAUR1, faculty members understand the value of diversity but lack a comprehensive understanding of its goals and systemic changes needed for effective support. At MAUR2, many faculty members understand the value of diversity but few actively work to understand related issues. Some faculty members view diversity as a numbers game, limiting meaningful engagement and preventing effective support for these initiatives.

The CRM emphasizes that to progress in readiness, stakeholders must move from mere awareness to a substantive understanding of initiatives. Without this shift, misconceptions and passive attitudes may persist, undermining the initiatives’ success. Bridging this gap requires targeted education and communication to clarify the necessity and potential benefits of diversity initiatives. By fostering a deeper, shared understanding of efforts, institutions can better align faculty support with the goals of recruitment and retention strategies, ultimately driving meaningful departmental and institutional change.

The leadership dimension assesses the level of commitment and awareness of departmental leaders, including administrators, department chairs, and senior faculty, their understanding of the problem, and their active support for meaningful and sustained efforts to address it. The scores in this dimension ranged from 5.88 to 6.92. Four out of the five mean scores round down to a 6, placing them in the Implementation stage, including MAPUI2 (M = 6.32, SD 0.45), MAUPSR1 (M = 6.71, SD 0.25), MAPUI1 (M = 6.5, SD 0.65), and MAUR2 (M = 6.96, SD 1.13). MAUR1 (M = 5.88, SD 2.05) scored at the Preparation stage. While some studies find that administrators and department chairs hold varied attitudes toward diversity, with some adopting active strategies and others taking a more passive or avoidant approach (Gasman et al., 2011), we did not find significant variation in leadership readiness.

A MAUR1 respondent’s account of the chair’s leadership style reveals a systematic approach to integrating diversity discussions into departmental activities: “He has this commitment to monthly focused meetings and inviting in speakers.” This structured tactic aims to keep diversity efforts at the forefront of departmental priorities.

The initiatives department members mentioned, such as anti-racist summits and training on microaggressions, exemplify the leadership’s commitment to fostering an inclusive environment. One MAUR1 respondent noted, “Our department has implemented training sessions on unconscious bias, and leadership has made it a point to participate, showing their commitment to these efforts.”

Findings from the thematic analysis highlight significant challenges and nuances in the leadership dimension. While key informants felt that departmental leaders generally acknowledged the importance of diversifying faculty, some leaders view it as a secondary priority. As an informant at MAPUI1 explained, “We can hire extensively, but ensuring faculty workload meets contract requirements is my main priority. If I prioritized diversity, essential tasks would not get done. Diversity is an add-on—more of an awareness project.” This sentiment reflects the treatment of diversity as an auxiliary concern, rather than one of a department’s core priorities.

Moreover, leaders’ stances on diversity were often influenced by top-down directives from higher administrative levels. A respondent from MAPUI2 noted, “Our chair, I think…he’s really just following what the people higher up are kind of promoting. I think this is a consequence of the top-down thing.” Reliance on external administrative support or prodding highlights sometimes limited internal ownership of diversity efforts, which can undermine the continuity and effectiveness of initiatives. As one MAPUI1 interviewee emphasized, “Leaders are the chair and associate chair who wrote the job description; the dean funded the position, and the chair forms a hiring committee to make it happen.” Institutional leaders beyond the dean level did not factor into this faculty member’s perception of departmental leadership.

Competing priorities—especially within resource-constrained environments—led some leaders to perceive a zero-sum situation, where diversity initiatives could detract from other essential departmental needs. As a respondent from MAUR1 explained, “Some of them have said that since they have been trying to recruit and retain people and have not been successful at recruiting and retaining people, why dedicate time to that? ‘We have been trying,’ according to some senior people, so, ‘and they are still not coming, so why recruit?’” This reflects a sense of resignation and a narrow perception of diversity efforts, where increasing representation is seen as hopeless and incompatible with other departmental goals or priorities. This perspective does not challenge the effectiveness of current practices or acknowledge that existing recruiting strategies might be flawed. Instead, it deflects responsibility by implicitly blaming candidates for not applying, rather than considering alternative approaches or addressing systemic barriers that may deter REM individuals from seeking positions at the institution. An unwillingness to critically evaluate existing methods limits the potential for meaningful progress.

Finally, ambiguity surrounding targeted mentoring for REM faculty reflects a lack of clarity among departmental leaders. An informant from MAUR2 noted, “I’d say they are sort of in the middle. They understand the problem. It’s not something they have necessarily lived. And they have come to understand that there are people that have a lived experience that looks like this and are on board with that.” This highlights a gap between recognition of the issue and implementation of concrete, supportive actions for minoritized faculty. Another MAUR2 respondent commented, “We heard, sort of, murmurs that some people did not feel like this was the right approach in terms of changing how we would do anything because they felt like the best people will be the people we hire, and it does not matter what their minority status is.” This reported sentiment reveals resistance to intentional efforts to hire REM faculty; diversity-related support may be perceived as an unnecessary or even divisive strategy, rather than a necessary tool for retention and success.

Three departments (MAUR1 M = 5.25, SD 1.30, MAPUI1 M = 5.63, SD 1.20, and MAPUI2 M = 5.21, SD 1.33) scored at the Preparation stage, while MAUPSR1 (M = 6.08, SD 0.66) and MAUR2 (M = 6.42, SD 1.03) scored at the Initiation/Implementation stage. In departments at the Preparation stage, key informants reported that their colleagues passively support efforts to address the issue, but only a few play an important role in developing solutions. Department members have not taken broad ownership of the problem; they do not believe it is their responsibility to handle the issue and might not actively engage in its resolution:

What seems to be the problem is the actual work that needs to be done to actually change the department…So…we did a survey and I think 95% of the faculty said they are interested in this stuff, like changing the culture and stuff like that. But it doesn’t translate. And oftentimes what they often focus on in translation is a focus on students, representation of students of color, and all that stuff and not on themselves, the things that need to be corrected on themselves to help with that change. (MAUR1 respondent)

At MAUR1, members report a sentiment of helplessness, feeling that they have tried everything they know to do but their efforts have not been successful. Key respondents agreed that the departmental climate is not sufficiently welcoming to faculty from diverse backgrounds and were concerned because they had recently lost a REM faculty member to another institution.

MAPUI1 and MAPUI2 respondents acknowledged the demographic disconnect between their student body and faculty and suggest that it is a concern that affects all of them. A MAPUI1 faculty member explained, “I think we recognize that students need to sort of see themselves in the faculty that teach them or see a similar population….it makes me a better scientist, to have people with diverse views and experiences.” But members of these departments noted the relatively passive support for faculty diversity. A MAPUI1 respondent commented, “I would say everyone is supportive of the idea. It’s the effort that might be lacking.”

Scoring at the Initiation/Implementation stage suggests that a department understands that they are responsible for addressing the issue but they have only made modest efforts to do so. In response to MAPUI2’s efforts to discuss the results of their climate study, an interviewee noted differences in degree of involvement for this issue as opposed to other topics: “I would say, 60 to 80 faculty…attend monthly mandatory meetings. We had a meeting to talk about the climate survey when it comes to representation of faculty and all that stuff and how we are affecting pedagogy and making the environment inclusive and welcoming to students. And when we had that meeting, about 35 of the faculty showed up.” A MAUPS1 respondent’s comment also highlights the level of engagement:

I know it’s an issue beyond our department within our institution, especially in our location in downtown [mid-Atlantic city], and I know from discussions with colleagues at other institutions that as we said before, that they are aware of and struggle with this same issue without a huge amount of success. So it’s definitely a topic that’s out there and under consideration. Beyond that, I don’t know a lot of details.

Participants noted how busy faculty are, potentially causing them to view diversity as an “add on” that was not a priority on the long list of items to be accomplished. However, in some cases, a key leader’s efforts motivated a department to prioritize diversification. For instance, the MAUR2 department had no prior experience with a postdoc-to-faculty conversion program, but the dean encouraged them to participate in the initiative:

Multiple departments at [MAUR2] had the option to participate. And I think the biology department was very overall enthusiastic about it. So even though it’s not an effort that was necessarily spearheaded by the biology department, the biology department certainly embraced it.

The Knowledge of the Issue dimension assesses a department’s understanding of broader societal factors contributing to the lack of faculty diversity in the department. This dimension reflects the department’s awareness of systemic inequities, such as racism, sexism, and discrimination, that have historically limited access to academic positions for underrepresented groups. The lack of diversity among faculty is not just a departmental issue but a reflection of larger societal patterns, as well as barriers faced by underrepresented groups in academia, such as implicit bias, unequal mentorship opportunities, and disparities in funding or research support.

ANOVA results find significant differences (p < 0.05) on scores for this dimension, which fell into three stages of readiness: Pre-planning (MAPUI1 M = 4.04, SD 1.98), Preparation (MAPUI2 M = 5.43, SD 1.13 and MAUR2 M = 5.96, SD 1.95), and Initiation/Implementation (MAUR1 M = 6.38, SD 0.59 and MAUPSR1 M = 6.04, SD 0.51).

Despite being the first to implement the postdoc conversion initiative, MAPUI1 scored the lowest on this dimension, at the Preplanning stage, indicating that members of the department recognize that something must be done but their efforts are not yet focused with concrete ideas to address the problem. They are not particularly aware of structural issues in society broadly or higher education specifically that create a continued need to recruit and retain REM faculty. Uncertainty in the department about what the problem is and how to solve it is reflected in this comment:

We’re afraid to offend and we’re afraid to, afraid that we don’t know things that we should know about. We see it, and we’ve got the guilt over it, I think. I think we have the white guilt over it. We look at ourselves, even on Zoom, and there’s a whole picket fence going across of white people, and all talking about these issues that, you know, we don’t know what percentage of Black kids make it through our program. We have anecdotal evidence from certain ones and what we kind of sense, but we don’t know. We don’t, I don’t know.

I still think there’s some misconceptions on how we actually hire…diverse individuals, right? I mean, because there’s very few of them that wanna give up our standard way of evaluating…And to realize that, in every other search, our practices may have prevented these colleagues from rising up on the list is a hard thing to believe you did…And I think most people can’t even hear that, so. And if you can’t hear it, then how do you acknowledge that you were part of preventing people from a diverse background?

MAPUI2 and MAUR2 are at the Preparation stage in their knowledge of the issue. Some participants noted that departments might need to share faculty demographic data to demonstrate that they are not as racially diverse as faculty imagine. Despite various faculty diversity initiatives, key informants reported that members of the department at MAUR2 have limited awareness of systemic issues that lead to unequal outcomes:

I think a lot of people think that if you’re a minority in STEM that you’re golden and you’ll get a job. What I would say, you might get an interview, but you won’t necessarily get the job.

I think people think that the reason we don’t recruit faculty from diverse backgrounds is because there are none; no one applies. I believe this is wrong, but I think [others believe], “Well, if they applied we would hire them. But there are none. They don’t apply, so we can’t hire them.”

Another MAUR2 respondent suggested that knowledge of the issue is based on lived experience:

So I think that a lot of them have a general idea about this, but may have never actually seen the numbers, okay? And a lot of them come from communities where you rarely saw someone who was underrepresented, [because] they're as old as they are. So I’d say they’re sort of in the middle. They understand the problem. It’s not something they’ve necessarily lived. And they’ve come to understand that there are people that have a lived experience that look like this, and are on board with that. And then there are some people who are extremely well informed.

MAUR1 and MAUPSR1 are at the Initiation/Implementation stage. Some key informants felt that attention within the department was still on applicants rather than structural factors such as hiring processes:

I think it’s a little bit of the case of, that we don’t know what we don’t know. Faculty have a good knowledge of what’s needed to retain a minority faculty as opposed to attract them from the beginning. (MAUPSR1 respondent)

However, others reported that their campuses were making efforts to educate faculty and staff about racial equity, leading to greater understanding:

Well, I think there’s a lot of literature with the events of the past year that just, [I’m] thinking COVID but also thinking racial equity type of stuff. So, it’s a topic of conversation. And so, yeah, I think everyone is a lot more aware. And then on our campus our president has routinely [held] town halls and I guess panel discussions where he’s open and that topic is routinely brought up. (MAUPSR1 respondent)

While one MAUR1 respondent mentioned cluster hiring as a possible solution, another argued that they need a more sustainable solution:

Hiring several faculty at the same time to support this initiative…the idea would be to bring, kind of a cohort-style hire. So, bringing on maybe three or four faculty or something at the same time who focus on diversity science. And ideally these would also be faculty from diverse backgrounds, although they didn’t have to be. And bringing them on together so there’s, again, this community amongst the faculty who are collaborating and doing this research together and also collaborating with other folks in the department. And basically, in hopes, because with retention, also that could be really powerful, having these folks come in together and kind of build this community.

It’s, “Once we recruit one or two, we should be good.” But I think there’s just an incentive for this to be a regular process that happens all the time. It’s like it should be the norm in the future, but not just cluster or incentive for a certain period of time. I think that’s the misconception that a lot of people probably have. I think there was a lot of people who think like, “If you just recruit a few,” but actually, it’s not enough. You need to have some work in the process on a continuous basis so people are supportive and people are supported by a bigger net instead of just an island in recruitment by themselves.

Our analysis revealed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), with institutions falling into three stages of readiness: Pre-planning (MAPUI2 M = 4.50, SD 1.53), Preparation (MAUR1 M = 5.00, SD 0.94, and MAUPSR1 M = 5.83, SD 1.76), and Initiation/Implementation (MAUR2 M = 6.21, SD 0.46 and MAPUI1 M = 6.29, SD 0.53).

At the time of our interviews, MAPUI2 had not implemented the postdoc conversion initiative and were in the process of committing resources to faculty diversification. They were aware of the message that it sent when and if they relied on grant funds, as one MAPUI2 respondent explained: “Sustaining these efforts through grant funds suggests that the efforts are temporary. So some efforts are funded externally and the funding will go away.” Another respondent compared their lack of resources to a private research-intensive institution, saying “Of course [Johns] Hopkins, they can just go and sort of hand-pick and get the people and just offer more money because they can afford it. A state institution might have a harder time putting up that money….that actually [is] what frustrates me, that Hopkins actually is doing that, because I think that’s not only unfair, I think it’s really hurting academia overall.” The assumption is that primarily undergraduate institutions are in competition with private research-intensive institutions for the same REM candidates, and are likely to lose the contest. This “high-demand/low supply” myth of a bidding war for REM scholars persists despite being debunked (Smith et al., 2004).

The two research-intensive institutions (MAUR1 and MAUPSR1), with operational budgets of over a billion dollars each, were at the Preparation stage:

The chair…has actually put aside $200,000 to focus on broadening participation and increasing representativeness of samples and students and trying to do a pipeline for, focus on doing a pipeline for postdocs to people of color to, that will transition to an assistant professor. This is why I feel like leadership, at least my chair, is invested because he’s actually been, put away $200,000 and has encouraged both my work and my colleagues, and my work in trying to get these funds. (MAUR1 respondent)

We’re not there yet but we’re working on it. We’ve not had any specific programs, efforts identified for other, say, faculty recruitment in diversity other than the expressed wish that we need to recruit a more diverse faculty. Those resources come to the chair to use to recruit new faculty then. But again, it’s not a separate pot of money that is designated for diverse [individuals]. (MAUPSR1 respondent)

The readiness scores indicate that size or institutional budget does not automatically determine the level of resources available to support diversity efforts. MAUR2 and MAPUI1 both scored at the Initiation/Implementation stage, despite their differences in focus (research vs. teaching), size, and budget. MAUR2 had several other postdoc conversion programs on campus, and one respondent explained why no new resources were being committed: “No resources are being allocated to solve a problem that in their minds no longer exists.” Another MAUR2 informant asked, “Is there really need for additional interventions?” A MAPUI1 interviewee discussed expanding their resources to address the issue, saying “we had zero before [the initiative], and now we are looking at, we used to have no policies written down at all for anything. Now, we are becoming more policy-driven, and so, we are adding a little bit, we are adding these…the diversity statement and rubric.” Another MAPUI1 respondent is optimistic about future resources for this new hiring path:

For incoming tenure-track faculty members, they are given research monies to sort of continue with and start up a research program. As far as I know, this will be the case for this postdoc position as well. So, I think if we were to continue down this way and hire any people like this, then those internal funds would continue to be provided. This comes primarily through the [school], through the dean’s office is really who determines how much research money people are given to sort of support their research at the beginning of their career.

Most departments rely on external funding from offices at the provost, dean, or college level to support initiatives for recruiting and retaining diverse faculty. While some departments have diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) administrators or access to institutional resources, others lack designated departmental funds for faculty diversification. Despite these limitations, departments offer professional development opportunities specifically aimed at addressing diversity issues, which some faculty actively use to enhance their skills. As a MAUR2 respondent noted, “Several people in my department have taken it upon themselves to train…by acceding to positions of leadership and committees…Our people go to workshops and all kinds of extracurricular activities to try and improve their understanding and skills.” This highlights a proactive effort by some individuals to take advantage of available resources that the department offers to address diversity challenges, even as systemic, long-term solutions remain underdeveloped.

This study employs a novel application of the Community Readiness Model (CRM) to evaluate the readiness of biomedical departments at five universities to recruit and retain faculty from racially and ethnically minoritized (REM) backgrounds. We used the Departmental Readiness Tool (DRT) to assess departmental readiness across the CRM’s nine stages, ranging from no awareness to community ownership. This framework provided a nuanced baseline for understanding each department’s capacity to implement and sustain faculty diversity initiatives.

In our analysis, overall readiness scores did not vary meaningfully by type of institution, with all five departments scoring in the middle of the readiness continuum, in the Preparation (n = 4) or Initiation/Implementation (n = 1) stage. However, there were more differences between departments when comparing scores within domains, with statistically significant differences in several areas. This affirms, that the department is an important level of community to examine for understanding the contexts where diversification efforts would take place. The DRT is successfully able to differentiate dimensions where departments are more and less prepared. It also underscores the DRT’s utility, regardless of institutional type, in providing actionable departmental data to drive improvements in readiness.

None of the departments in this study received an overall score indicating the highest level of readiness. Our findings challenge the argument by White-Lewis (2021) that the success of faculty diversity strategies “greatly depends on various configurations of an institution’s type and resources” (p. 340), as this was not an important factor in overall readiness levels. While institutional resources and configurations may facilitate diversity initiatives at a macro level, they do not ensure that departments are prepared to implement or sustain them. Departmental readiness offers a more targeted approach to understanding the factors that enable or hinder the success of diversity initiatives.

The variability in scores on different dimensions highlights the significant role of departmental actors. Key informant interviews indicated that most of the departments have relatively successfully negotiated the hurdles of attracting talented REM students, but may fail to recognize that REM faculty confront similar issues. Former University of Richmond President Ronald Crutcher summarized the need for ongoing efforts, saying “Systemic racism is a peculiar American condition. It’s like a heart condition—it’s not something you can get rid of. You cannot fix it. But you can manage it” (cited in Brown, 2021, p. 17). Addressing racial equity and faculty diversity requires sustained commitment and deliberate action rather than isolated, one-time efforts.

Discussing the complexities of fostering diversity within institutional contexts, Brown (2021) suggests that “Not all institutions, offices, or departments are ready to diversify. People of color who are hired often end up feeling isolated and frustrated, and leave after a couple of years” (p. 90). Her definition of readiness (“being comfortable with being uncomfortable, inviting new perspectives into decision-making, and, in some cases, giving up power” [p. 90]) provides a compelling framework for understanding the cultural and structural shifts required for sustainable diversity efforts. Our study builds on Brown’s work by applying the CRM to operationalize and measure readiness as the degree to which a department is ready to take action on the recruitment and retention of faculty from diverse backgrounds.

The CRM conceptualizes readiness not as a binary state (ready or not ready) but as a continuum, with varying levels of readiness across six dimensions. Readiness is multi-faceted and dynamic. For example, one department in our study demonstrated high readiness in terms of leadership support and resource allocation but exhibited lower readiness in the departmental climate, with lingering resistance to change among members. This variability underscores Brown’s argument about the discomfort and power dynamics inherent in fostering diversity. Departments must not only invite new perspectives in but must also address relational resistance and structural barriers to ensure that newly hired individuals—particularly those from underrepresented groups—are included and valued rather than isolated and frustrated.

While this study uses data collected at a single timepoint, readiness is not static; it can change over time with targeted interventions. Departments that initially exhibit low readiness in some dimensions can make measurable progress after engaging in facilitated dialogues, training sessions, and ongoing evaluations. Departments should view readiness as a developmental process, that can be cultivated through intentional efforts.

Our findings also contribute to understanding the critical role of departmental contexts in shaping the outcomes of diversity initiatives (Boyle et al., 2020; White-Lewis, 2020). Considering these contexts can help explain why academic units within the same university—operating under uniform institutional policies such as implicit bias training and equity office interventions—may yield vastly different results (White-Lewis, 2021). Lee et al. (2007) argue that “the keys to more lasting reform may lie in the academic department….Trying to implement change too hastily in the department, however, may squander resources or at best result in a quick flush of change that quickly vanishes when the intervention is withdrawn….If the level of readiness is not sufficient, department leadership and faculty members should first create such readiness before moving forward with significant change interventions” (p. 17). Diversity initiatives confront structural issues embedded in societal inequities and university policies and practices. Departments must not only express readiness but also take proactive and sustained steps to address systemic inequities. As inequity and structural barriers are fundamentally social issues, STEM departments may benefit from the support of their social science colleagues to design and implement effective interventions. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, departments can develop comprehensive approaches to managing systemic inequities, ensuring that diversity initiatives translate into meaningful and lasting institutional transformation.

Gaps in departmental readiness should not delay diversity and inclusion efforts. Waiting until a department is fully ready can perpetuate existing disparities. By assessing readiness and pinpointing areas needing improvement, departments acquire crucial insights that allow them to take charge of their transformative journey, embarking on strategic planning, judicious allocation of resources, and development of appropriate policies. This approach situates departments as trailblazers in advancing faculty diversification and confers on institutions the ability to allocate resources prudently.

While initiatives like mentoring programs, cluster hiring, and target-of-opportunity hiring focus on recruiting diverse individuals, they often neglect whether departments are ready to support, retain, and value their new colleagues. This can result in patchwork solutions that maintain the status quo rather than driving transformative change. Griffin (2020, p. 282) distinguishes between a “diversity mindset,” which centers on representation through numbers and quotas, and an “equity mindset,” which focuses on creating systemic changes to ensure fair access, opportunities, and outcomes. Departments will have done enough when fair and equitable hiring processes are informed by the lessons of past initiatives. When departments no longer rely on external funding or temporary programs to advance faculty diversity but instead sustain these efforts through embedded practices and policies, we will know we have achieved lasting change. The goal of readiness is not to tick off items on a checklist, but to achieve a state where departments naturally prioritize equity and inclusion.

Our findings, aligned with the hiring literature, emphasize the need for a shift from a diversity mindset to an equity mindset. Progress must be iterative—addressing one dimension of readiness at a time while building a foundation for sustained change across all dimensions. This approach ensures that diversity initiatives are not isolated or temporary but become embedded in faculty hiring and retention processes. Ultimately, we will have done enough when equitable practices are institutionalized and diversity initiatives are no longer necessary because departments are prepared to foster and sustain equity and inclusion in all aspects of their operations.

Assessing departmental readiness for any initiative is valuable for administrators with limited resources, as it helps prioritize efforts and allocate resources effectively. While only some campuses may have the interest or ability (given their geopolitical context or funding source) to pursue diversity initiatives, departments will continue to be units of action for implementing other priorities and curricular changes. Institutions can foster change where it is most likely to succeed and allocate resources to departments that are ready to move forward. For departments that are struggling, the assessment can guide targeted support to help increase their readiness, ensuring that resources are used strategically.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board, University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

WC-V: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. GS: Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. FU: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), Directorate for Education and Human Resources (EHR), through the following Alliances for Graduate Education and the Professoriate (AGEP) awards: #1820984, #1820974, #1820971, #1820983, and #1820975.

We would like to thank the PROMISE Academy Alliance Leadership Team and the External Advisory Board for their continued work developing, implementing, and scaling the model of faculty diversification in the biomedical sciences through postdoctoral pathways.

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1553580/full#supplementary-material

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: racism and diversity in institutional life. Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press.

Allen, A. M., and Stewart, J. T. (2022). We’re not OK: black faculty experiences and higher education strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

American Psychological Association (2021). Equity, diversity and inclusion framework. Available at: https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/equity-division-inclusion-framework.pdf (Accessed January 26, 2025).

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2011). The invisible weight of whiteness: the racial grammar of everyday life in contemporary America. Ethn. Racial Stud. 35, 173–194. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.613997

Boyle, S. R., Phillips, C. M., Pearson, Y. E., DesRoches, R., Mattingly, S. P., Nordberg, A., et al. (2020). An exploratory study of intentionality toward diversity in STEM faculty hiring. American Society of Engineering Education Virtual Conference Newsletter, paper #31234.

Brayboy, B. M. J. (2003). The implementation of diversity in predominantly White colleges and universities. J. Black Stud. 34, 72–86. doi: 10.1177/0021934703253679

Brown, S. (2021). Diversifying your campus: key insights and models for change. Washington, DC.: The Chronicle of Higher Education. 9:14.

Campbell, P. B., Thomas, V. G., and Stoll, A. (2009). “Outcomes and indicators relating to broadening participation” in Framework for evaluating impacts of broadening participation projects: report from a National Science Foundation workshop. eds. B. C. Clewell and N. Fortenberry (Washington, DC: The National Science Foundation), 54–63.

Carter-Veale, W., Cresiski, R. H., Sharp, G., Lankford, J. D., and Ugarte, F. (2024). Assessing departmental readiness to support minoritized faculty. New Directions for Higher Education. 2024, 47–57.

Castañeda, S. F., Holscher, J., Mumman, M. K., Salgado, H., Keir, K. B., Foster-Fishman, P. G., et al. (2012). Dimensions of community and organizational readiness for change. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 6, 219–226. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0016

Culpepper, D., Reed, A. M., Enekwe, B., Carter-Veale, W., LaCourse, W. R., McDermott, P., et al. (2021). A new effort to diversify faculty: Postdoc-to-tenure track conversion models. Front. Psychol. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733995

Donnermeyer, J. F., Plested, B. A., Edwards, R. W., Oetting, G., and Littlethunder, L. (1997). Community readiness and prevention programs. Community Dev. 28, 65–83.

Edwards, R. (1999). The academic department: how does it fit into the university reform agenda? Change 31, 16–27. doi: 10.1080/00091389909604219