- 1Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

- 2Global Engagement Center, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

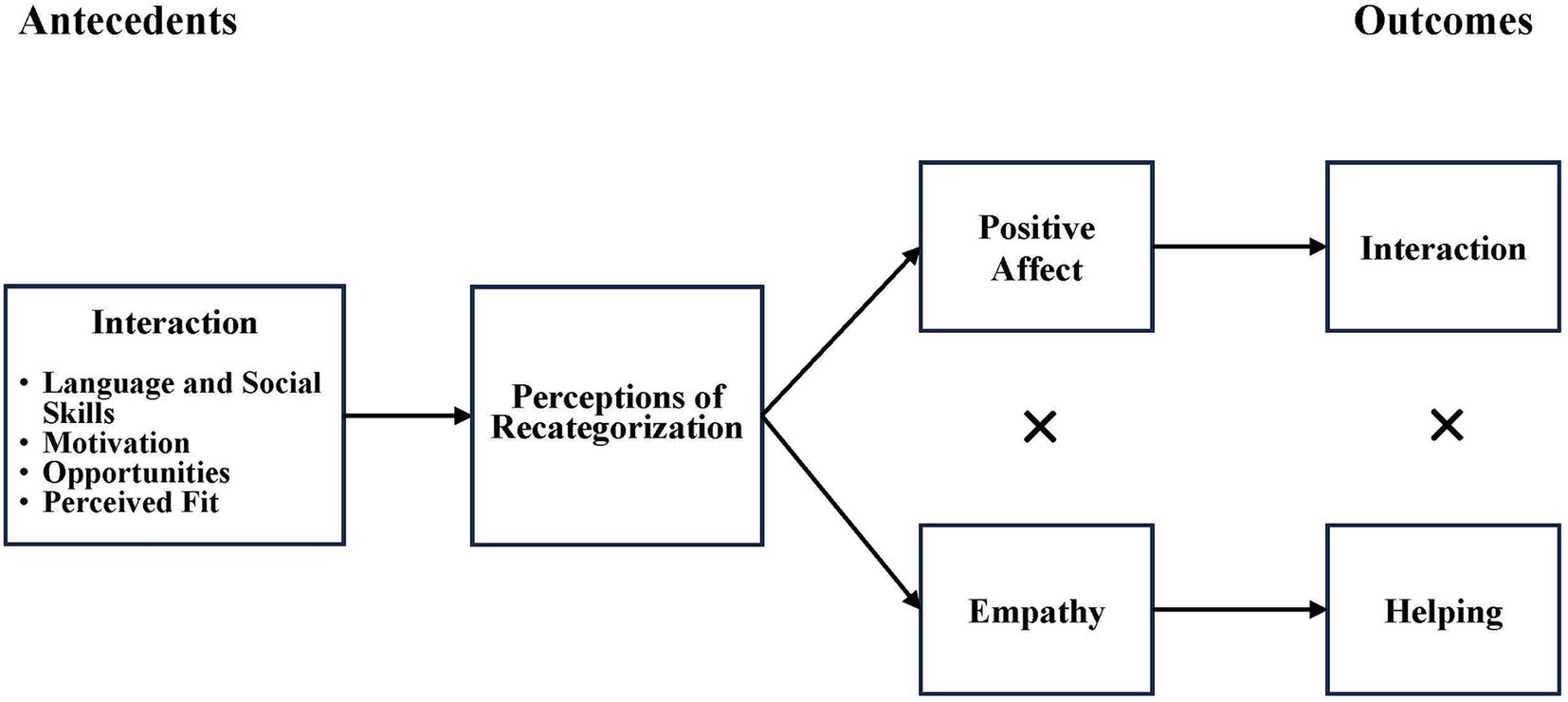

Previous research has focused on how students adapt to the host country during study abroad. However, less is known about how these experiences influence students’ social engagement upon returning home. This study explores how Japanese students’ social interactions abroad influence their relationships with international students in Japan after their return. Using a qualitative approach based on grounded theory, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 24 Japanese students who had studied abroad for one academic year. The findings suggest that social interactions abroad facilitate recategorization, a process in which individuals redefine group boundaries and develop a broader shared identity. This process was influenced by four key factors: language and social skills, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit. Through this process, Japanese students expanded their group boundaries and formed a shared identity with international students in Japan as individuals with study abroad experience. As a result, they developed more positive attitudes toward international students, heightened empathy, and a stronger motivation to engage with and help international students. These findings indicate that recategorization can occur through the formation of a new social identity based on shared experiences rather than direct intergroup contact, highlighting the long-term impact of study abroad on students’ intercultural engagement. This study underscores Japanese students’ tendency to identify with international students in Japan rather than with host nationals upon their return.

1 Introduction

While some Japanese students report a change in their values and attitudes following their study abroad experience, others indicate that they have become more aligned with traditional Japanese values and attitudes (e.g., Heine and Lehman, 2004; Japan Student Services Organization, 2018; Yokota, 2018). To investigate this discrepancy, we explored how Japanese students who had studied abroad perceived their social interactions in their host country and how these interactions affected them cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally upon their return to Japan.

According to data from pre-COVID 2019, 107,346 Japanese students participated in study abroad programs, representing a threefold increase from 2009 (Japan Student Services Organization, 2019). The majority of these students were enrolled in short-term or semester programs. Among them, those who had spent approximately 1 year abroad identified interacting with local people and understanding their culture as their primary objective (Fritz and Murao, 2020). Local residents of the host country, including classmates, friends, and host families, are the most reliable source of information regarding the cultural norms, values, and beliefs of the host country.

Social interaction with these individuals served an instrumental role in conveying the host culture and facilitating the integration of Japanese students into the local community. For instance, Japanese students who had studied abroad indicated that they had enhanced their communication abilities and developed a deeper grasp of cultural nuances through their interactions with locals in the classroom setting (Yokota, 2018). Specifically, students who studied abroad for a period of 3 months or more formed a greater number of local friendships and acquired a deeper understanding of the host country’s culture than students who studied abroad for a shorter period. Moreover, 90% of these individuals reported a change in their attitudes toward foreign and Japanese cultures upon their return (Japan Student Services Organization, 2018).

These studies indicate that social interaction with local people while studying abroad provides Japanese students with sufficient knowledge of the host culture to alter their attitudes toward foreign and/or Japanese cultures upon their return home. Nevertheless, the precise extent to which Japanese students adopt the host culture through social interaction, the factors involved, and the outcomes of this cultural adoption remain unclear.

2 Literature review

2.1 Host culture adoption

Culture is defined as “unique meaning and information systems, shared within groups and transmitted across generations, which allow groups to meet survival needs, pursue happiness and well-being, and derive meaning from life” (Matsumoto and Juang, 2023). As illustrated in the above definition, the process of host culture adoption entails the integration of the host culture’s meaning and information system, encompassing values and beliefs. For instance, Japanese students who resided in Canada for seven months exhibited an increase in their self-esteem (Heine and Lehman, 2004). This indicates that if Japanese students are surrounded by Westerners with high self-esteem for approximately 1 year, their self-concept may be influenced by Western culture. Therefore, meaningful social interaction in the host country is crucial for the adoption of the host culture.

2.2 Social interaction in the host country

The existing literature on international students has examined the role of social interaction in student adjustment. International students typically interact with three main groups: (1) host nationals (natives), (2) co-nationals (compatriots), and (3) non-co-nationals (international students from other national backgrounds; Bochner et al., 1977). With regard to social interaction with host nationals, Kashima and Loh (2006) observed that Asian international students with stronger ties to local Australians exhibited a higher level of host cultural orientation. Similarly, Hendrickson et al. (2011) indicated that international students with a high proportion of friendships with host nationals exhibited significantly greater satisfaction and a stronger sense of social connectedness. These findings suggest that social interactions with host nationals are important for international students’ adjustment to the host culture. However, it has often been reported that relationships with host nationals are sporadic and superficial (Meng et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2020).

Broadly, earlier studies have indicated that co-nationals were the primary source of social support, while host nationals were second, and non-co-nationals were third (Bochner et al., 1977; Furnham and Alibhai, 1985). However, more recent studies have yielded different results, indicating that non-co-nationals serve as the primary network, co-nationals as the secondary network and host nationals as the terriary network (Montgomery and McDowell, 2009; Schartner, 2014). Consistent with these findings, another study found that interaction with non-co-nationals provides both academic and emotional support, that interaction with co-nationals serves as a source of comfort for students, and that interaction with host nationals remains a superficial social relationship (Pho and Schartner, 2019). Furthermore, a recent study indicated that Chinese international students in Belgium were subject to the influence of both individual and environmental factors. The study identified two environmental factors—low motivation of host nationals and lack of opportunities—as the root causes of superficial social interaction with their host nationals (Meng et al., 2019). Collectively, these findings indicate that research on international students’ social interaction needs to examine the antecedents and outcomes of social interaction, not merely the patterns of social interaction.

2.3 Antecedents of social interaction

The antecedents of social interaction have been examined from both individual and environmental perspectives (Bethel et al., 2020; Meng et al., 2019). Among individual differences, language proficiency has been documented as an influential factor in social interaction with host nationals. For example, both English and local language proficiency were identified as significant predictors of social ties among Chinese international students in their host country (Cao et al., 2017). Additionally, studies have indicated that international students with high English proficiency play a pivotal role in fostering close relationships with host nationals, whereas low English proficiency has been associated with challenges in academic performance and adjustment in the host country (Pho and Schartner, 2019).

Moreover, motivation to interact with host nationals has been identified as a crucial factor influencing social interaction. Despite the fact that numerous studies have indicated that international students initially aspired to engage with host nationals, they encountered significant challenges due to a lack of interest and initiative on the part of the host nationals (Brown, 2009; Robinson et al., 2020; Schartner, 2014). In contrast, a recent study reported that Chinese international students exhibited a tendency to remain within the compatriot network in their host country, and demonstrated a reluctance to establish social networks with host nationals (Meng et al., 2019). These contrasting findings indicate that international students’ motivation to interact with host nationals varies widely, ranging from strong interest to reluctance. This diversity in attitudes highlights the need for further investigation into the factors shaping their social engagement.

With respect to environmental factors, limited opportunities for interaction with host nationals have been identified as a structural barrier. International students and host nationals often study and live in separate university facilities and housing, and tend to participate in social activities that are largely exclusive to their own groups (Meng et al., 2019). These distinctions in study, housing, and social activities result in a lack of opportunities for interaction, which may cause international students to feel isolated and detached from the host community (Pho and Schartner, 2019; Schartner, 2014).

Furthermore, cultural distance (Hofstede, 2001), defined as the degree of cultural dissimilarity in norms and values between internationals and hosts, has been identified as a significant determinant of social interactions. For instance, international students find it easier to interact with those from culturally similar backgrounds, while perceiving fewer commonalities with host nationals, such as shared conversational topics and social behaviors. These differences often act as barriers, leading to greater segregation (Robinson et al., 2020). Consequently, cultural distance has been shown to negatively impact host-national connectedness (Bethel et al., 2020).

2.4 Outcomes of social interaction

The extant literature on social interaction outcomes has documented that international students form a shared identity with host nationals, often referred to as common ingroup identity (Gaertner et al., 2000). The Common Ingroup Identity Model draws on the theoretical foundations of Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and Self-categorization Theory (Turner et al., 1987). In accordance with the common ingroup identity, members of different groups can recategorize themselves as a single, more inclusive superordinate group encompassing both compatriots and the hosts. Their attitudes toward the former host “outgroup” members, now conceived of as part of the “ingroup” will become positive, mitigating any prejudice that might stand between them (Gaertner et al., 2000).

This process of recategorization entails a shift in members’ perceptions of group boundaries from a dichotomous “us versus them” to a more inclusive “we.” As a result, the typical inclination to view one’s own group in a favorable light (ingroup bias; Brewer, 1979) is extended to subgroup members included in the superordinate representation. This results in the formation of positive beliefs, affect, and behaviors toward formerly outgroup members. In line with this model, other studies have demonstrated that recategorization can also facilitate positive affect (Gaertner et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 2006), as well as empathic concern, which in turn gives rise to altruistic motivation and helping behavior toward the newly regarded ingroup members (Batson, 2011; Dovidio et al., 1997).

In this context, social interaction between members of different groups serves as a means of learning about each other, which has the effect of undermining prejudice and increasing understanding. Furthermore, social interaction has been demonstrated to reduce anxiety, foster intimacy, and cultivate empathy for individuals who were previously perceived as belonging to the outgroup. Consequently, social interaction serves to diminish the perceived distance between subgroups, and promotes a sense of similarity and belonging to a more comprehensive community. The efficacy of these processes is enhanced when there is a superordinate identity category (e.g., university student community) that subsumes subgroup identities.

For instance, Chinese students in a group comprising both Chinese and American members (e.g., a Christian, classmates) exhibited a sense of solidarity with the American, based on a shared ingroup identity, making them more likely to empathize with the Americans even when they held opposing views on a contentious political matter (Hail, 2015). A subsequent study revealed that Chinese students who demonstrated profound engagement with French culture exhibited a more favorable social relationship with the local French population, a greater sense of social connectedness, a higher level of received social support, and a reduction in prejudice (Cao et al., 2018). These findings suggest that international students in host countries may form a kind of shared identity with host nationals.

However, such studies on international students only focus on when they are abroad and not on when they have returned to their home country. The extent to which international students are aware of the outcomes of these social interactions after they return home has not been sufficiently investigated. In this regard, Stoeckel (2015) found that German students formed a European identity through social interactions with non-co-national international students while studying abroad, and that this change remained stable after the students returned to their home institutions. While such research has been accumulating, a different insight may be gained by focusing more on the experiences of Japanese students in relation to the link between social interactions in the host country and their impact on students after they return home.

2.5 The present study

The present study aims to explore how Japanese students who have studied abroad perceive their social interactions in the host country, and how these social interactions have affected them cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally.

In light of the above objectives, we propose the following research questions:

1. How do Japanese students perceive the factors that influence social interaction while studying abroad?

2. How do Japanese students perceive the influence of social interaction during their study abroad on themselves upon their return to Japan?

3. To what extent do Japanese students perceive the adoption of the host culture through social interaction in the host country upon their return to Japan?

A grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) will be employed to explore Japanese students’ perceptions of their experiences. Charmaz (2014) emphasizes the importance of situating a grounded theory within the context of existing research findings and theoretical frameworks (Charmaz, 2014, p. 311). As discussed in the previous sections, past research has primarily examined how international students align their identities with host country nationals during their time abroad. In contrast, this study investigates how social interactions in the host country influence returnees after studying abroad. While this study builds on existing theoretical research, particularly the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 2000), it also takes an exploratory approach by examining returnees’ experiences. Therefore, this study not only employs this theoretical perspective but also aims to construct a middle-range conceptual model based on empirical data.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

In line with previous research findings (Heine and Lehman, 2004; Yokota, 2018), we selected participants who had studied abroad for one academic year and had engaged in social interactions with locals and/or international students frequently enough to facilitate the adoption of the host culture. Additionally, the destination countries were specified as Western countries, which are the typical study abroad destinations for Japanese students (Japan Student Services Organization, 2019).

The participants were 24 Japanese students (15 females, 9 males) who had spent one academic year (8 to 12 months) studying in Western countries and had returned to Japan between 2016 and 2024. They studied abroad as undergraduates in various countries, including the United States (12), the United Kingdom (4), Australia (3), Sweden, Spain, Poland, Germany, and Finland (1 each). During their study abroad period, all participants were enrolled in higher education institutions and engaged in regular academic coursework alongside local peers in their host country. Additionally, some were enrolled in English language courses or participated in internships. Most participants resided in dormitories with locals and international students, except for one individual who lived with a host family. At the time of the interview, the participants ranged in age from 20 to 26 years. All had returned from their study abroad within the past three years. Nineteen of the participants were currently enrolled as undergraduate students at medium-sized public or private universities located in urban areas of Japan. The remaining five participants had already commenced employment in these same areas.

3.2 Procedure

This study was approved by the Nagoya University Institutional Review Board (ID: 191270) before participant recruitment began. Following this approval, the principal researcher collaborated with study abroad centers and international student affairs officers at Japanese universities to invite Japanese students who had studied abroad to participate in the study via email or in person. A total of 15 students were recruited for the study between 2019 and 2020, while nine students were recruited between 2023 and 2024. Prior to the interview, all participants were provided with an explanation of the study and a consent form, and their consent was duly obtained.

In line with previous research (e.g., Meng et al., 2019; Stoeckel, 2015), the interview questions addressed both successful and challenging social interactions in the host country, as well as changes in cognitive processes, emotional states, and behavioral patterns after returning to Japan.

The interviews were conducted in Japanese and lasted between 60 and 90 min. In conducting the interviews, the research team did not categorize international students as co-nationals and non-co-nationals, as had been done in previous research, because there were very few Japanese international students at the participants’ host institutions. All interviews were transcribed, cross-checked against the audio recordings, and coded. The research team then identified themes, patterns, and relationships in the interview transcripts.

3.3 Analysis

The research team employed grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) to code and analyze interview transcriptions, focusing on three stages: initial coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding. Constant comparisons were made during each stage to ensure that the data collection process was conducted in parallel. The initial coding stage involved processing meaningful words and phrases, while the focused coding stage entailed organizing codes into larger categories and themes. The final stage was theoretical coding, which identified relationships between categories and themes to provide a conceptual framework. The team maintained a written record of their assumptions and thought processes, a practice known as memo-writing. Furthermore, the team employed theoretical sampling to analyze the data, a process that entailed the iterative collection and refinement of categories. The principal investigator conducted interviews with 15 students and developed a preliminary framework during the 2019–2020 period. Subsequent interviews were conducted with nine students during the 2023–2024 period, aimed at confirming the accuracy of the model. The team ceased data collection when novel data no longer generated new theoretical insights. This ongoing sampling strategy, which included peer review and participant feedback, optimally reflected the experiences of study participants.

3.4 Research team

The three researchers were Japanese, bilingual, and had each spent a substantial amount of time residing in Canada, the United States, and Germany. The principal investigator had been engaged in international student exchange for over 25 years, and was currently serving as both a faculty member and an international student advisor in his department. This expertise guided the design of this study, as well as the subsequent data collection, analysis, and writing. The remaining two researchers were professors with over 30 years of experience in the academic fields of social psychology and international education. In addition to their expertise in these fields, they had also been involved in the implementation and coordination of international student exchange. As a result, they contributed to the credibility of our analysis by examining social interactions in the host country and their changes after students return to Japan from both academic and practical perspectives.

4 Results

Our analysis identified four themes related to Japanese students’ experiences of social interactions in the host country: language and social skills, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit. In addition, three themes related to the outcomes of social interactions in the host country were identified: perceptions of recategorization, positive affect and interaction, and empathy and helping. Participant quotes are provided to illustrate each theme.

4.1 Social interaction in the host country

In interviews with 24 participants, all students reported experiencing both the adoption of the host culture and the reaffirmation of Japanese culture. However, the extent to which they reaffirmed Japanese culture and adopted aspects of the host culture varied considerably. Seventeen students indicated that they reaffirmed Japanese culture and consciously decided the extent to which they would integrate aspects of the host culture. In contrast, seven students reported substantially altering their perceptions and feelings about Japanese culture as a result of adopting elements of the host culture. Four key themes emerged from the interviews that shaped their responses.

4.1.1 Language and social skills

The first theme, language and social skills, highlights how these factors shaped participants’ social interactions with host nationals, influencing their ability to engage effectively in social settings. Twelve out of the 24 participants initially struggled with language barriers, describing difficulties in understanding fast-paced conversations, interpreting direct communication styles, and grasping cultural nuances. These barriers often led to psychological stress and feelings of exclusion. One participant illustrated this experience:

I talked to American students, but it was mostly small talk. We didn’t have much to discuss, and I felt a lot of stress due to the language barrier. It made me feel alienated because I couldn’t fully join the local students’ group.

This sense of alienation was a recurring theme among participants who lacked confidence in their language abilities. However, as participants reflected on these struggles, they also identified various strategies to mitigate these challenges.

In contrast, the remaining 12 participants emphasized the importance of social skills as a means of overcoming these barriers. Among them, several found ways to navigate these barriers by leveraging social skills, particularly interpersonal sensitivity. One participant explained how she adjusted her approach:

In class, my classmates started arguing about a game rule. As the discussion grew more intense, I listened to their opinions and encouraged them to compromise. Some classmates commented that Japanese people are good at maintaining harmony in relationships. Through my interactions with the British, I became more aware of my own Japanese identity and realized who I was.

Rather than relying solely on language proficiency, this participant demonstrated interpersonal sensitivity by showing concern for others and acting as a mediator, which enabled her to build rapport despite linguistic challenges. This suggests that social skills can help overcome language barriers, offering another way to facilitate interaction with host nationals.

Other participants emphasized the importance of self-disclosure and actively creating personal opportunities to interact with locals, particularly in settings where group conversations were overwhelming. One participant noted:

I wondered whether some international students got along with Finns while others didn’t, depending on the way international students invited Finns to interact after Japanese class, even if they were in the same class. I wanted to make friends with the locals, but since I’m not comfortable speaking in large groups, I preferred one-on-one interactions.

This illustrates how students strategically adapted their interaction styles, opting for smaller, more intimate settings where they felt more comfortable engaging in conversation. By prioritizing personal interactions, they naturally engaged less in large-group interactions, which in turn fostered deeper individual relationships.

These findings indicate that while language barriers initially hindered interaction, social skills played a crucial role in shaping participants’ engagement with host nationals. Rather than viewing language proficiency as the sole factor in successful interaction, participants recognized the interplay between language abilities and social adaptability, highlighting the diverse ways in which Japanese students navigated social interaction in a host context.

4.1.2 Motivation

The second theme, motivation, emerged as participants’ willingness to engage with the host culture varied based on their study abroad objectives. Thirteen of the 24 participants initially expressed a strong desire to integrate aspects of the host culture, including its values and beliefs. Among them, seven developed a strong sense of integration into the host culture, which led to a transformation in their personal values and perspectives. One participant shared her experience:

I was able to embrace Swedish culture and values because I consciously absorbed them and interpreted them in my own way. I experienced a strong sense of well-being and a slower pace of life in Sweden. Making small changes to align with these ideas improved my well-being and made my study abroad experience more enjoyable.

Her experience highlights the role of active engagement in cultural adaptation—those who intentionally integrated into Sweden’s local customs and interpreted its cultural norms in their own way found greater satisfaction in their study abroad experience. However, this process was not uniform across participants.

The remaining six participants initially intended to adopt the host culture but ultimately found it challenging due to various barriers. Language barriers hindered their ability to form relationships with locals, limiting their integration. One participant described her struggle:

At first, I tried to learn British customs, but the language barrier and my lack of confidence made it impossible. I initially stayed with Asian international students, but I realized I couldn’t continue that way. When I tried again to build personal relationships with British people, the language barrier remained a challenge.

Her account underscores how language proficiency was a critical factor in cultural adaptation (see Theme 1). While motivation influenced participants’ initial willingness to engage with the host culture, communication barriers ultimately restricted deeper integration.

In contrast, the remaining 11 participants had different study abroad goals, such as improving their English proficiency, pursuing academic studies, or advancing their international careers. Their focus was on personal and professional development rather than cultural adaptation. One participant explained:

My goal in studying in the U.S. was to improve my English and experience life abroad. While I accepted and respected American culture, I continued to live as a Japanese person. I had no desire to change my values to assimilate into American culture.

His statement indicates that his personal goals took priority over cultural adaptation during his study abroad experience. While he acknowledged the host culture, he deliberately chose to maintain his original values and identity. This suggests that cultural adaptation is not merely a result of exposure but is shaped by individual goals and intentions.

These findings indicate that initial motivation influenced how participants engaged with the host culture. Those who actively sought cultural integration succeeded when external barriers, such as language proficiency, did not obstruct their efforts. Conversely, those with other priorities were less likely to alter their values. Thus, motivation played a central role in determining whether participants internalized the values of the host culture, shaping how language ability and personal objectives influenced this process.

4.1.3 Opportunities

The third theme, opportunities, highlights how access to and engagement in social interactions shaped participants’ engagement with both locals and international students. While many had access to social spaces for interacting with locals, the extent to which they utilized these opportunities varied, influencing their social networks and engagement with the host culture.

Among the 24 participants, 20 described having opportunities to interact and collaborate with locals in both academic and extracurricular settings. In classrooms, they worked on group projects, attended lectures, and collaborated with local students. Outside academics, they joined social groups such as sports clubs, church fellowships, and Japanese language circles, which facilitated informal interactions. However, simply having opportunities did not guarantee meaningful connections. One participant shared his experience of immersing himself in local communities:

After six months, I changed my environment by joining a soccer club and attending all the home parties I was invited to by American students. Working as a Japanese language class assistant, I gained confidence in helping Americans learn Japanese.

His experience underscores the importance of proactive engagement in fostering deeper relationships with host nationals. By placing himself in environments that encouraged local interaction, he increased his chances of forming meaningful connections.

In contrast, 18 participants reported frequent interactions with international students, particularly those from Asian countries. As non-native English speakers, these students were perceived as more approachable than locals, making communication easier. Participants also felt a sense of familiarity due to shared cultural values and physical appearance, which encouraged closer connections. Additionally, university policies grouping international students in dormitories played a key role in shaping these social networks. Living in shared spaces fostered daily interactions, naturally strengthening friendships and a sense of belonging. One participant reflected on how the dormitory environment influenced her social interactions:

I learned more about career flexibility from international student groups in the dorm than from Americans. With many events taking place in the dorm, I was satisfied with my interactions with international students and didn’t feel the need to engage further with locals.

This illustrates how institutional structures shaped participants’ social networks. Frequent interactions with international students fostered a sense of community but often resulted in less engagement with locals, as students felt more comfortable within their international peer groups. Five participants confirmed this, feeling comfortable in their friendships with Asian and European international students and seeing little need to expand their social circles. Ultimately, social interactions depended not only on opportunities but also on personal comfort, shared experiences, and language confidence.

These findings suggest that engagement with the host culture depends not only on opportunities but also on how individuals engage with them. While some actively sought interactions with locals, reinforcing their cultural adaptation, others found comfort in international student groups. Thus, personal choices and contextual factors play a crucial role in facilitating social interactions with host nationals, which in turn create opportunities for the internalization of host cultural values.

4.1.4 Perceived fit

The fourth theme, perceived fit, emerged as participants evaluated the extent to which the host culture aligned with their personal values and beliefs. Seventeen out of 24 participants reaffirmed their Japanese cultural values through interactions with the host culture. Initially, they sought to immerse themselves in the host environment, but experiences of cultural discomfort made them realize that Japanese values were a fundamental part of their identity. One participant described this realization:

I studied abroad to immerse myself in British culture, but after a few months, I realized that Asia and Japan were a big part of my identity. I started dressing and presenting myself as more Japanese. I felt that the British were British, and I was me. I didn’t change much in my mindset. For example, I wondered if my insistence on sharing the garbage disposal and cleaning the dorm kitchen was a Japanese trait.

This participant’s experience illustrates how cultural immersion can reinforce pre-existing identities rather than lead to complete assimilation. Similarly, another participant reflected on how studying abroad shifted her aspirations:

My roots were in Japan. Before studying abroad, I wanted to live in the U.S., but now I don’t. I appreciate American openness and friendliness, but I realized I don’t have to force myself to be like an American or change my fundamental way of thinking.

These reflections highlight a common trend: instead of fully adopting the host culture, many participants developed a stronger awareness of their Japanese identity as a result of their study abroad experiences.

In contrast, seven participants found that the host culture’s values aligned closely with their own, reinforcing their motivation to embrace it. One participant studying in Finland described how her experiences shaped this perspective:

When I stayed with my Finnish friends' parents, I connected with nature, built bonfires, and experienced the quiet atmosphere. Since I was already skeptical of Japan’s fast-paced lifestyle, I chose to study in a country with a different rhythm, and I felt genuinely happy there. The Finnish lifestyle suited me better.

This account suggests that for some participants, studying abroad provided an opportunity to seek alternative lifestyles that resonated more deeply with their personal values. Similarly, exposure to different communication styles influenced participants’ perceptions of cultural fit. One participant who studied in Germany noted:

In Germany, I had to clearly say yes or no with reasons, and this communication style suited me. After returning to Japan, I still use this approach at work and have adjusted my lifestyle to maintain a German-style work-life balance.

These experiences illustrate how participants assessed their personal alignment with the host culture through firsthand engagement with local norms and practices. Some reaffirmed their Japanese identity, while others found alternative cultural models that better aligned with their personal values.

In sum, four key factors—language and social skills, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit—interacted to shape participants’ social interactions in the host country. Language and social skills (Theme 1) influenced how effectively participants navigated intercultural interactions, while motivation (Theme 2) shaped their willingness to engage with the host culture. Opportunities (Theme 3) determined the extent of contact with locals, either facilitating or limiting meaningful engagement. Finally, perceived fit (Theme 4) influenced how participants assessed the compatibility between their own values and those of the host culture. As a result, these factors collectively shaped whether participants incorporated aspects of the host culture into their lives or maintained their existing cultural perspectives.

4.2 Outcomes of social interactions in the host country

As a result of social interactions in the host country, participants experienced notable shifts in their perceptions, emotions, and ways of engaging with international students in Japan. Sixteen of the 24 participants actively supported international students, providing academic and daily life assistance, Japanese conversation practice, and other forms of support. Additionally, they took part in activities that fostered cross-cultural interaction, such as school clubs, shared housing, and social gatherings.

In contrast, the remaining eight participants were either unaware of these changes or did not engage in activities associated with them. These shifts occurred gradually during and after their study abroad experience, making it difficult for participants to articulate their changes in a clear and detailed manner. This section explores three key themes as outcomes of social interactions in the host country.

4.2.1 Perceptions of recategorization

The fifth theme, perceptions of recategorization, emerged as participants reassessed their self-perceptions and views of international students in Japan within the context of the university student community. All students experienced both the adoption of the host culture and the reaffirmation of Japanese culture, though the extent of these processes varied depending on four factors (see Themes 1 through 4).

Through this process, participants redefined their identity and deepened their self-awareness. Reflecting on their experiences, they became more aware of how their perspectives and experiences differed from those of Japanese students who had not studied abroad, reinforcing their sense of identity as individuals with study abroad experience. One participant described this shift:

Before studying abroad, I thought other people’s values were always right and often worried about others’ opinions. However, after returning to Japan, I have become more confident in my own way of thinking and feeling, and I want to live by my own values.

This shift in self-perception suggests that studying abroad provided her with an opportunity to critically reflect on her beliefs, ultimately leading to a clearer sense of her own values.

Additionally, most participants reported that experiencing both the joys and challenges of studying abroad (see Themes 1 through 4) reshaped their views of international students and deepened their empathy (see Theme 7). This understanding fostered stronger connections with the international student community. One participant reflected:

As a former international student, I realized that international students often don’t have cars, struggle with the language, and face difficulties in daily life. So I wanted to be someone they could rely on in Japan, someone who could support them when needed…. Since I understand how hard it can be for international students to make Japanese friends, I wanted to become part of the international student community.

This participant identifies herself as a “former international student,” meaning an individual with study abroad experience, while also expressing empathy and a desire to support international students as peers.

Furthermore, participants noted that engaging with diverse cultural backgrounds boosted their confidence in communicating with international students in Japan and heightened their awareness of their identity as individuals with cross-cultural experiences. This confidence strengthened their self-perception as individuals with study abroad experience, helping them see international students as peers rather than as a separate group. One participant shared:

Before, I admired international students and wanted to talk to them in English. But after returning to Japan, that admiration has faded—I now see them as part of my everyday life. If an international student needs help, I naturally want to get involved. My sense of ‘wanting to engage’ has changed significantly after studying abroad.

This account shows how her study abroad experience made her see international students as part of her social sphere.

These narratives demonstrate how study abroad experiences shaped participants’ cognitive perceptions and led Japanese students to view international students as peers rather than outsiders. One participant encapsulated this transformation:

Before, international students and Japanese students seemed like distinct groups on campus. Now, I see a more mixed categorization: Japanese students who have only lived in Japan, those like me who have experienced both Japan and life abroad, international students who have lived abroad and are now experiencing Japan, and international students who are already familiar with Japan. Although we all share the label ‘university student,’ each person’s experiences are unique…. When I studied in Sweden, I stopped focusing on identity and race. You can’t judge a person just by looking at them, so I began to prioritize talking to and understanding them rather than categorizing them.

This testimony demonstrates how study abroad reshaped participants’ perceptions of social group boundaries, leading them to identify more with those who share study abroad experiences rather than with groups defined by nationality. These participants recognized their commonalities with international students in Japan, forming a shared identity based on their study abroad experience, reinforcing experience-driven recategorization.

Through their study abroad experiences, participants reevaluated social boundaries and developed a shared identity as individuals with study abroad experience, fostering a sense of belonging beyond national distinctions. This shift encouraged more natural and reciprocal interactions with international students, strengthening emotional connections and motivating participants to support them.

4.2.2 Positive affect and interaction

The sixth theme, positive affect and interaction, became evident in participants’ accounts of how their attitudes toward international students in Japan changed after studying abroad. Before going abroad, many participants viewed interactions with international students primarily as opportunities to practice English. However, upon returning, their motivation shifted toward genuine engagement, driven by the enjoyment they experienced abroad, exposure to new perspectives, and a desire to continue these meaningful interactions in Japan. One participant reflected on this shift in motivation:

Before studying abroad, I wasn’t particularly motivated to befriend Asian international students. However, after spending time in the Asian student community in England, I now enjoy interacting with Asian international students in Japan as well.

Her statement illustrates how firsthand immersion in a diverse cultural environment reshaped her willingness to engage with international students. Experiencing a sense of belonging within an international community abroad made her more open to forming similar connections back in Japan.

Another participant highlighted the enjoyment of engaging with people from diverse backgrounds in the host country:

In Poland, I experienced discussions I never imagined. For example, in political debates, I encountered people with conservative views, while others were more liberal. It was exciting to challenge and refine our ideas one by one. In Japan, people don’t discuss politics like that.

Her experience demonstrates how exposure to open and dynamic discussions abroad led to a greater appreciation for diverse perspectives. After returning to Japan, she sought to maintain this exposure to different viewpoints and cultural experiences by engaging with international students.

These positive interactions abroad evoked feelings of joy and connection, fostering a deeper appreciation for intercultural exchange. Some participants found that even casual encounters with international students in Japan, such as seeing them on campus, brought them joy. One participant described this emotional connection:

Now, I smile when I see international students in the university cafeteria. It reminds me of the fun experiences I had with international students in England—exploring university shops, eating together, and having a great time. I want international students in Japan to enjoy themselves just as much.

Her response highlights how positive emotions associated with past interactions influence present behaviors and attitudes. The nostalgia she experiences when encountering international students suggests that emotional bonds formed abroad can carry over into one’s home environment, reinforcing continued engagement with culturally diverse groups.

These findings suggest that positive interaction experiences abroad strengthened participants’ emotional connection to international students in Japan, increasing their engagement and interest in intercultural exchange. More broadly, they indicate that study abroad experiences do not merely provide temporary exposure to cultural diversity but have lasting psychological and social effects that extend into post-return interactions. By fostering a sense of connection, confidence, and openness, these experiences contribute to long-term attitudinal shifts that support deeper intercultural relationships.

4.2.3 Empathy and helping

The seventh theme, empathy and helping, emerged as participants reflected on how studying abroad changed their emotions and actions toward international students in Japan. While abroad, they encountered interpersonal challenges and relied on both local and international students for support. These experiences heightened their awareness of the difficulties international students face and fostered a desire to assist others upon their return. One participant recalled feeling nervous and uncertain in her first class in Australia:

When I attended my first class in Australia, I was very nervous and scared. The professor was kind, noticed my situation, and approached me. Both local and international students also talked to me during class, which made me feel relieved. I can imagine that international students in Japan must also feel nervous about attending classes. Because I understand how they feel, I want to help them in the same way.

Her experience shows how receiving support in an unfamiliar setting made her realize the importance of offering similar assistance to international students in Japan. By identifying with their anxieties, she developed a stronger sense of responsibility toward creating a welcoming environment.

Many participants also expressed concern that international and Japanese students had few opportunities to interact and actively sought ways to bridge this gap. One participant reflected on her study abroad experience and how it motivated her to support international students in Japan:

I'm tutoring a Korean international student now, and I noticed that she had little interaction with Japanese students. When I studied in England, I mostly interacted with international students and had fewer chances to connect with British students. I had to seek out those opportunities on my own, and it was quite difficult. So I feel sad when I see international students in Japan facing the same challenge. That made me want to get involved and support them as a Japanese friend.

Her experience shows how her challenges abroad deepened her awareness of international students’ struggles in Japan and motivated her to actively support them. Many of these participants saw themselves not just as tutors but as friends who foster social connections and a sense of belonging.

Another participant explained how her experiences in Finland reinforced her motivation to assist international students in Japan:

I can imagine how lonely international students feel being alone in a foreign country…so I wanted to create a comfortable place for them in Japan. When I studied in Finland, my tutors helped me a lot, and I realized how important it was to have someone to rely on. Many people helped me while I was abroad, and now I want to return the favor by helping international students here.

Her statement highlights how receiving support abroad firsthand often inspired a strong desire to reciprocate that kindness upon returning home. This cycle of support and empathy shows how study abroad influences both personal growth and engagement with international students in Japan.

Recognizing the challenges of studying abroad and the value of support, participants developed greater empathy and actively helped international students. This shift shows how personal experiences of vulnerability and support abroad can transform into proactive efforts to foster inclusivity and help others in similar situations.

In sum, three key factors—perceptions of recategorization, positive affect and interaction, and empathy and helping—interacted to shape participants’ engagement with international students after studying abroad. Through the process of recategorization (Theme 5), participants redefined social group boundaries, seeing themselves and international students as peers rather than separate groups. This transformation fostered positive affect and interaction (Theme 6), deepening their appreciation for cultural diversity and increasing their motivation to engage with international students. These experiences also cultivated empathy and a desire to help (Theme 7), prompting participants to take active roles in supporting international students in Japan, often as tutors or cultural mediators. Together, these outcomes illustrate how study abroad experiences not only reshape personal perceptions but also encourage long-term engagement with international students in Japan, fostering sustained intercultural connections even after returning home.

4.3 Summary of the results

Our analysis identified that participants’ study abroad experiences were shaped by the interplay of four key factors—language and social skills, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit—which influenced how they navigated intercultural interactions in the host country. These factors influenced not only how participants engaged with the host culture but also how they interacted with international students and other culturally diverse individuals upon returning to Japan.

Upon returning to Japan, participants underwent a process of recategorization, influenced by their study abroad experiences. Through this process, they not only redefined social group boundaries but also reassessed their own identity as individuals with study abroad experience, perceiving international students as peers rather than an outgroup. This transformation fostered positive affect and interaction, deepening their appreciation for cultural diversity and increasing their motivation to engage with international students. Furthermore, these experiences cultivated empathy and a sense of responsibility, prompting participants to take active roles in supporting international students, often as tutors or cultural mediators.

Together, these findings illustrate how study abroad experiences shape both self-perception and engagement with international students upon return to Japan. The factors influencing social interactions in the host country ultimately contributed to long-term intercultural engagement in Japan, reinforcing connections beyond the study abroad context and solidifying participants’ identity as globally engaged individuals. Figure 1 illustrates the process by which study abroad experiences influence long-term engagement, showing how key themes are interrelated — from the antecedents of social interactions abroad to recategorization and its subsequent outcomes.

5 Discussion

5.1 Recategorization through social interaction in the host country

This study examined how study abroad experiences influence participants’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes upon return. Four key factors—language and social skills, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit—shaped their intercultural engagement abroad and continued to influence their interactions in Japan. After returning, participants underwent a recategorization process, expanding group boundaries and adopting a shared identity as individuals with study abroad experience. This shift fostered positive affect, empathy, and sustained intercultural engagement, deepening their connection with international students and motivating them to actively help and support international students.

Our findings align with the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 2000), which suggests that intergroup contact can foster a shift from an “us vs. them” mindset to a shared identity.

One possible explanation for the findings is that social interactions abroad prompted participants to redefine group boundaries, shifting their perceptions from a distinction between “Japanese students” and “international students in Japan” to a broader recognition of “individuals with study abroad experience.” This recategorization likely influenced how they engaged with international students once they were back in Japan.

Additionally, as participants redefined group boundaries, their attitudes toward international students became more positive, which can be explained by the concept of ingroup bias (Brewer, 1979). This concept posits that individuals tend to favor those they perceive as members of their own group. By recognizing international students as part of their expanded ingroup, participants may have developed greater positive affect and a stronger willingness to interact with them. This process may explain why many participants, upon return, continued engaging with international students instead of reverting to exclusively Japanese-centered social circles.

Furthermore, our study found that participants cultivated empathy and a sense of responsibility, which led them to actively support international students in Japan—often as tutors, mentors, or cultural mediators. This finding aligns with Dovidio et al. (1997), who argue that recategorization can result in empathic arousal, whereby an individual’s motivational system becomes attuned to the needs of others, fostering helpful and altruistic behaviors. In our study, through the recategorization of group boundaries, participants developed greater empathy toward international students, as they recalled their own challenges during study abroad and related them to the struggles faced by international students in Japan. This process of empathic arousal, in turn, motivated them to actively support international students upon their return, taking on roles as tutors, mentors, or cultural mediators.

Collectively, these findings illustrate how study abroad experiences influence both self-perception and intercultural engagement after returning. The Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 2000) explains how participants redefined their self-perceptions and social boundaries. The concept of ingroup bias (Brewer, 1979) provides insight into their increasingly positive attitudes and interactions with international students, while Dovidio et al. (1997) account for their heightened empathy and motivation to support them. Together, these theoretical perspectives provide a psychological framework for understanding how study abroad returnees cultivate a lasting commitment to intercultural exchange beyond their time abroad.

Beyond theoretical alignment, our findings support and expand upon prior research on study abroad returnees and their post-return engagement (Cao et al., 2018; Hail, 2015; Stoeckel, 2015). In particular, our study builds on Stoeckel (2015) work, which found that German students formed a European identity through social interactions with non-co-national international students abroad, and that this change remained stable after their return. This process closely parallels our findings, as participants similarly developed a shared identity with international students in Japan through interactions with host nationals and other international students in the host country.

However, our study extends this understanding by showing that both positive and challenging study abroad experiences foster a shared identity as individuals with study abroad experience, which facilitates recategorization and enables participants to perceive international students as peers, deepening intercultural engagement. By clarifying how study abroad drives identity transformation and post-return social relationships, our study provides new insights into its long-term impact. In this regard, while Stoeckel (2015) showed that study abroad fosters identity change, our study further reveals its underlying mechanisms, illustrating how study abroad experiences shape a shared identity as individuals with study abroad experience, which in turn fosters recategorization and deeper intercultural engagement.

Furthermore, our findings corroborate previous research indicating that only a subset of students develop a shared identity with host nationals. In our study, 17 out of 24 participants reaffirmed their connection to Japanese culture, while seven developed a stronger attachment to the host culture. This finding aligns with studies on Chinese international students, which found that only some students established a shared identity with host nationals in the United States and France (Cao et al., 2018; Hail, 2015).

Thus, a considerable number of participants appear to have formed a shared identity with international students in Japan upon their return, rather than with host nationals during their time abroad. One possible interpretation of this finding is that while social interactions with host nationals are crucial for student adjustment, interactions with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds may also be a key factor in shaping student outcomes—regardless of whether they are host nationals or international students. These findings suggest that social interactions in the host country play a crucial role in shaping student adjustment and long-term intercultural engagement. The following sections will examine the antecedents and outcomes of these interactions.

5.2 Antecedents of social interaction

Our findings identify four antecedents of social interactions, categorized into two individual factors (language and social skills, motivation) and two environmental factors (opportunities, perceived fit). These findings align with the framework discussed in Section 2 (Meng et al., 2019).

Among the four factors, language and social skills played a crucial role in shaping social interactions in the host country. Approximately half of the participants encountered language-related difficulties when interacting with locals in the host country. These difficulties gave rise to psychological barriers that impeded socialization, consistent with those of previous researchers (Brown, 2009; Cao et al., 2017; Pho and Schartner, 2019). Conversely, approximately half of the participants indicated that social skills, including interpersonal sensitivity, self-disclosure, and one-on-one interactions, were effective in reducing intergroup conflict and fostering closer relationships with host nationals. This finding aligns with Brown (2009), who found that social skills play a crucial role in cultural adjustment by facilitating meaningful interactions and reducing psychological barriers in intercultural settings. It also supports Gaertner et al.’s (2000) concept of personalization, which emphasizes the importance of individualized interactions in building intergroup connections. Participants who engaged in one-on-one conversations or shared personal experiences were more successful in overcoming social barriers and forming meaningful relationships with host nationals. Therefore, despite the potential challenges in forming relationships with host nationals due to language barriers, the development of social skills may serve as a compensatory factor in fostering relationships with host nationals.

Furthermore, regarding motivation, a number of participants indicated a desire to adopt the host culture, whereas others expressed a lack of motivation, citing language barriers and their individual goals as factors. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that low language proficiency is associated with poor adjustment in the host country (Cao et al., 2017; Pho and Schartner, 2019) and research suggesting that Japanese students’ motivations for studying abroad are largely limited to English language learning and superficial cultural experiences (Fritz and Murao, 2020). In light of global landscape, the conventional objectives of study abroad—namely, language acquisition and cultural understanding—appear to be evolving.

As for environmental factors, the majority of participants reported having frequent opportunities to interact with both host nationals and international students in the host country. This finding contrasts with previous studies (Pho and Schartner, 2019; Schartner, 2014), which reported limited social interactions with host nationals. However, as discussed in Section 2, Meng et al. (2019) found that frequent interaction with host nationals did not necessarily lead to deeper relationships due to language barriers. This aligns with our findings.

Moreover, regarding perceived fit, the majority of participants indicated a sense of alignment between their personal values and beliefs and those of Japanese culture. Conversely, some participants indicated a perceived alignment between the values and beliefs of the host culture and their own. Despite the intention of studying abroad to adopt the values and beliefs of the host culture (Fritz and Murao, 2020; Yokota, 2018), the majority of participants reaffirmed their Japanese cultural values and beliefs due to the significant cultural differences between Japan and the host country. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating that cultural distance impedes host-national connectedness (Bethel et al., 2020; Robinson et al., 2020).

In summary, while language proficiency plays a key role in fostering social interactions in the host country, social skills can compensate for language barriers. Additionally, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit further influence students’ engagement.

5.3 Outcomes of social interaction

Building upon the discussion in Section 5.1, which highlighted the role of recategorization in shaping participants’ social engagement, this section examines the outcomes of social interactions, focusing on positive affect, interaction, empathy, and helping.

Our findings indicated that through social interaction in the host country, participants exhibited greater positive affect and engaged more frequently with international students in Japan. They also showed heightened empathy and a greater willingness to support international students in Japan.

The relationship between positive affect and interaction can be explained by Johnson et al. (2006) claim that positive affect may foster a more inclusive sense of ingroup identity and facilitate the recategorization of outgroup members as part of the ingroup, leading to a lasting sense of shared identity. From this perspective, participants’ positive affect, such as feelings of joy and interest, may have reinforced their recognition of international students as fellow students and encouraged sustained interactions. As this process was iterative and self-reinforcing, ongoing interactions with international students further strengthened their positive emotions and deepened their commitment.

Regarding empathy and helping, this finding aligns with the empathy-altruism hypothesis (Batson, 2011), which suggests that two conditions are necessary for empathic concern: perceiving the other as in need and valuing their welfare, which in turn fosters altruistic motivation toward ingroup members. In our study, participants who faced cultural and linguistic challenges and received support from locals and international students during study abroad became more attuned to the difficulties international students encounter in Japan, fostering an altruistic motivation to provide assistance and promote inclusive intercultural interactions. In addition, by redefining international students as part of their ingroup, participants came to perceive their well-being as personally and socially significant. This recognition reinforced their commitment to fostering inclusive intercultural interactions and providing support upon their return. These acts of reciprocity and recognition of ingroup members’ well-being further reinforced their empathy and strengthened their commitment to intercultural engagement.

5.4 Theoretical implications

This study extends the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 2000) by showing that recategorization can be driven not only by intergroup contact but also by the formation of a new social identity based on shared experiences. While the Common Ingroup Identity Model traditionally emphasizes the role of intergroup interaction in fostering a superordinate identity, our findings suggest that the development of a shared identity as individuals with study abroad experience itself serves as a mechanism for recategorization, facilitating greater engagement with international students in Japan. Building on these findings, this study further refines the Common Ingroup Identity Model by illustrating how shared experiences—rather than direct intergroup contact alone—can shape identity-based recategorization. This process expands group boundaries, strengthens participants’ psychological connection with international students, and motivates continued intercultural engagement upon return.

Furthermore, this study provides a structured framework for understanding the antecedents, mediators, and outcomes of recategorization within the Common Ingroup Identity Model. Previous research has given limited attention to clearly specifying the factors that shape this process or capturing how these factors interrelate (Gaertner et al., 2000). Our study addresses this gap by identifying four key factors—language and social skills, motivation, opportunities, and perceived fit—that influence intercultural interactions abroad. These factors shape shared experiences, which, in turn, determine the quality of recategorization and impact positive affect, empathy, interaction, and helping behaviors. By explicitly mapping these connections, our model extends the Common Ingroup Identity Model beyond its traditional applications and provides new insights into how international experiences contribute to long-term intercultural engagement.

5.5 Practical implications

This study expands the understanding of study abroad outcomes by suggesting that the impact of study abroad extends beyond individual growth, shaping returnees’ engagement in intercultural exchange and support activities upon their return. Previous research has primarily framed the outcomes of study abroad in terms of personal growth and individual goals (e.g., Fritz and Murao, 2020). However, this study suggests that returnees were motivated to engage with international students in Japan, leading to increased participation in intercultural exchange and support activities.

As discussed in Theoretical Implications, recategorization through a shared identity as individuals with study abroad experience played a key role in facilitating continued engagement with international students. Through this identity shift, returnees perceived international students as part of their extended social group, which encouraged them to take an active role in intercultural exchange and support efforts. However, research suggests that opportunities for interaction between Japanese and international students in Japan remain limited in both quantity and quality (Taniguchi et al., 2022).

Given these findings, simply increasing international student enrollment is insufficient for fostering meaningful intercultural engagement. Instead, universities should actively leverage returnees as facilitators to bridge the gap between Japanese and international students in Japan. Institutions can support this process by implementing structured programs such as peer mentoring, tutoring, and intercultural events, ensuring that returnees play an active role in fostering meaningful engagement. By strengthening collaboration between returnees and universities, these initiatives can help translate study abroad experiences into sustained intercultural interaction, contributing to the genuine internationalization of higher education.

5.6 Limitations and future research

It should be noted that our study has some limitations. First, as a qualitative study, our findings are inherently shaped by the subjectivity of participants’ narratives and the researcher’s interpretation. While grounded theory was employed to develop a theoretical framework, the emergent findings are context-specific and may not be directly generalizable to different cultural or educational settings. Future research could incorporate quantitative or mixed-method approaches to enhance the robustness and transferability of these findings.

Second, our study focused on Japanese participants who had studied abroad in Western countries for one academic year. Those who are aware that their stay in the host country will be limited to a short period may not be as ready to adopt a host culture identity as international students seeking a degree and possibly employment in that country. Future research should examine whether different study abroad conditions—such as variations in study duration, program type, destination (e.g., Asian countries), or individual factors such as gender, prior overseas experience, and pre-departure training—lead to different outcomes.

Third, it is possible that both Japanese students and host nationals held self- and other-cultural stereotypes, which may have shaped their expectations and interpretations of intercultural interactions (Glazer et al., 2018). While our study primarily examined the recategorization process from the perspective of Japanese students, it is also crucial to consider how their presence influenced host nationals, as recategorization is a mutual process. Future research could track changes in biases among both groups over time (before, during, and after study abroad) to better understand how intergroup contact contributes to the formation, maintenance, and transformation of cultural biases. This would offer valuable insights into both theoretical discussions on intergroup relations and practical strategies for fostering positive intercultural engagement.

6 Conclusion

This study explored how Japanese students’ social interactions during study abroad influence their relationships with international students in Japan. Using qualitative analysis based on grounded theory, our findings suggest that social interactions in the host country facilitated recategorization, wherein Japanese students expanded their group boundaries and formed a shared identity with international students in Japan as individuals with study abroad experience. This identity shift was linked to greater positive affect toward international students in Japan, heightened empathy, and increased motivation to engage in intercultural interactions and support activities upon their return.

Our findings contribute to the literature by showing that the impact of study abroad extends beyond individual adaptation and identity transformation in the host country. Instead, study abroad experiences influence students’ long-term engagement with intercultural interactions in their home country, fostering a sustained commitment to cross-cultural exchange. This study extends the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 2000) by suggesting that social interactions in the host country not only foster connections with host nationals but also shape relationships with international students in the home country upon return.

These findings also highlight that participants tended to identify more strongly with international students in Japan upon returning home, rather than with host nationals during their study abroad. While extensive research has examined students’ adaptation to the host country, further investigation is needed into the changes they undergo after returning home. In this regard, our study may be the first to explicitly examine the process of recategorization for Japanese students as an outcome of study abroad.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Nagoya University Institutional Review Board (ID: 191270). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NI: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP20K14027.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bethel, A., Ward, C., and Fetvadjiev, V. H. (2020). Cross-cultural transition and psychological adaptation of international students: the mediating role of host national connectedness. Front. Educ. 5. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.539950

Bochner, S., McLeod, B. M., and Lin, A. (1977). Friendship patterns of overseas students: a functional model. Int. J. Psychol. 12, 277–294. doi: 10.1080/00207597708247396

Brewer, M. B. (1979). In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: a cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychol. Bull. 86, 307–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.307

Brown, L. (2009). A failure of communication on the cross-cultural campus. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 13, 439–454. doi: 10.1177/1028315309331913

Cao, C., Meng, Q., and Shang, L. (2018). How can Chinese international students’ host-national contact contribute to social connectedness, social support and reduced prejudice in the mainstream society? Testing a moderated mediation model. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 63, 43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.12.002

Cao, C., Zhu, C., and Meng, Q. (2017). Predicting Chinese international students’ acculturation strategies from socio-demographic variables and social ties. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 20, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12171

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Validzic, A., Matoka, K., Johnson, B., and Frazier, S. (1997). Extending the benefits of recategorization: evaluations, self-disclosure, and helping. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 401–420. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1997.1327

Fritz, E., and Murao, J. (2020). Problematising the goals of study abroad in Japan: perspectives from the students, universities and government. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 516–530. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1643869

Furnham, A., and Alibhai, N. (1985). The friendship networks of foreign students: a replication and extension of the functional model. Int. J. Psychol. 20, 709–722. doi: 10.1080/00207598508247565

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., and Bachman, B. A. (1996). Revisiting the contact hypothesis: the induction of a common ingroup identity. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 20, 271–290. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(96)00019-3

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., and Samuel, G. (2000). Reducing intergroup bias. London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge: The common ingroup identity model : Psychology Press.

Glazer, S., Roach, K. N., Carmona, C., and Simonovich, H. (2018). Acculturation and adjustment as a function of perceived and objective value congruence. Int. J. Psychol. 53, 13–22. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12554

Hail, H. C. (2015). Patriotism abroad. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 19, 311–326. doi: 10.1177/1028315314567175

Heine, S. J., and Lehman, D. R. (2004). Move the body, change the self: acculturative effects on the self-concept. Psycholog. Foundations Cul. 8, 305–332.