94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 08 April 2025

Sec. Mental Health and Wellbeing in Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1544199

Background: Worldwide, 10–20% of youth suffer from mental health problems. Research shows that high levels of resilience may increase resistance against mental and physical distress. In this, a ‘whole-school’ resilience intervention (Anchor Approach) can support children and adolescents. The aim of this study was to understand the intervention effects according to staff, parents and mental health services. Perceptions are explored through intervention sustainability, acceptability, efficacy, feasibility and flexibility and adaptability.

Methods: Seven qualitative focus groups were conducted in six schools adopting the Anchor Approach intervention, with participants consisting of parents (N = 4), school staff (N = 12), and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS; N = 4). Thematic analysis was conducted on the data by two researchers.

Results: Four themes were revealed: (1) “Timeliness,” (2) “Behavioural Impact of the Anchor Approach,” (3) “Engagement with the Anchor Approach,” (4) “Working together.” Participants felt the intervention was timely and changes toward emotion-focused care were found. Variations between schools in its usage resulted in differences in confidence, behavioral changes and care continuity. Dependent on environmental factors, concerns about feasibility were raised regarding implementation, resources and communication of support offered.

Conclusion: The Anchor Approach was well utilized and accepted, positively impacting staff confidence, student behavior and staff-student interactions. High levels of acceptability and utilization (with variations) were identified across participants. Staff time and complexity of resources provided may impact intervention feasibility and sustainability.

The prevalence of child and adolescent mental health problems in England has increased over the past 20 years (Collishaw et al., 2004; Collishaw et al., 2010). Childhood mental health problems contribute to lower educational achievements, increases of health risk behaviors, self-harm and suicide (Patel et al., 2007; Fergusson and Woodward, 2002) and persist into adulthood (Arnow, 2004; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003). They are socially and economically costly, with burden falling on public services (Knapp et al., 1999; Suhrcke et al., 2007). Preventative research is therefore integral to individuals and the population at large.

Resilience research focuses on increasing the possibility of positive outcomes when an individual is faced with stress, rather than on reducing the likelihood of stress or adversity itself (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013). For example, resilience could constitute the strengths and assets (Martin and Marsh, 2008; Ungar and Liebenberg, 2013) that enable students to continue to perform well at school despite worries about their grades, future or identity. High levels of resilience have been shown to buffer against distress (Richardson, 2002; Vance et al., 2008) and resilience has been demonstrated to be improved through intervention (Johnson and Wiechelt, 2004). Thus, resilience interventions can prevent children and adolescents’ mental health difficulties from extrapolating (Johnson and Wiechelt, 2004).

School is a central component of a child’s life, influencing learning (Marzano, 2007), social and emotional health (Lester and Cross, 2015); thus, schools are considered the optimal setting for interventions promoting mental health (Goldberg et al., 2019).

A ‘whole-school approach’ specifically involves all levels of the school-working together, targeting the ethos behind problematic behaviors and the behaviors themselves (Dray et al., 2017). They focus on how the school environment interacts with student behaviors, for example providing staff resources to help when responding to difficult students constructively and positively, avoiding punitive punishments. These approaches have been found to be more effective than student-facing interventions in reducing psychological problems (Wells et al., 2003) as they are not limited to individuals or classrooms, having broader impacts at policy- and system-level (Allen, 2014). Whole-school resilience programs specifically have been shown to produce significant positives regarding academic, behavioral and social–emotional functioning (Durlak, 2015).

However, teachers’ programme acceptability influences their preparedness and accuracy for implementations (Reimers et al., 1987; Han and Weiss, 2005). The most important factors identified for successful whole-school approaches are: staff engagement, knowledge of intervention, time and availability of resources; highlighting the importance of understanding staff experiences and engagement for successful application (Han and Weiss, 2005; Bond et al., 2005). Currently, there is a bias toward student self-report in resilience research (Libbey, 2004; Leonard and Gudiño, 2021). To determine if an intervention is utilized as intended, staff needs to be paneled (Bruhn and Hirsch, 2017). Parents are also important stakeholders as they can reinforce the intervention using home resources (Banerjee et al., 2016). Finally, context should be taken into account; including the needs and capabilities of staff and students, and how the school environment and age of students impacts efficacy. Most school-based programmes target one age cohort and are implemented for a short-time, limiting their use in natural settings. Follow-ups where the intervention has been integrated holistically are necessary to understand real-world impacts (Banerjee et al., 2016). By collecting opinions from those implementing and supporting the intervention, across a range of environments, it is possible to identify which dimensions are important for specific outcomes (Fitzpatrick et al., 2013).

The Anchor Approach is a whole-school resilience intervention that has been used in 31 schools in the UK for up to six years. A collaboration between students, teachers, staff, parents, and health/social care professionals is involved, providing training for staff and parents alongside research-based tools (Brendtro and Brokenleg, 2009). Evidence-based emotion coaching (Gus et al., 2015) is also adopted by staff and parents, for children’s self-regulation and stress response management. The framework is adaptive, and when needed, areas of difficulty are identified, and resources are tailored, respectively.

Due to the intervention’s length and breadth, the Anchor Approach is an appropriate example of a naturalistic whole-school approach.

Using this intervention, we aimed to:

1. Explore staff and parent perceptions of the impact of a resilience-based whole-school intervention;

2. Explore whole-school intervention sustainability focusing on perceptions of:

a) Acceptability to staff (teachers, teaching assistants, senior leadership, special educational needs coordinators and parents);

b) Perceived efficacy of the program and its components in relation to student behavior;

c) Feasibility of implementing the intervention on an ongoing basis with ‘minimal but sufficient resources’;

d) Flexibility and adaptability of the intervention to complement the environment of individual schools.

A qualitative focus group design was adopted, and seven focus groups were run in total, with up to 6 participants attending each. Two interview schedules (one for staff, one for parents) were designed by the researchers in collaboration with the Public Health team (Haringey Council, London) and stakeholders (parents and staff), in order to most comprehensively evaluate the intervention. Schedule development was guided by the research aims, and the intervention suitability, which was guided by Han and Weiss’ (2005) school intervention suitability recommendations.

A pilot run of the interview schedules was conducted with one staff member and one parent linked to the Anchor Approach to refine the questions and suit the target population. The pilot also provided an opportunity for the researchers to discuss logistical arrangements with participants, such as the scheduling of focus groups. Following discussion and feedback from the staff member and parent (and the Steering Group), the final questions were agreed and submitted to UCL Research Ethics Committee, in the Ethics Application Form.

Staff and parent interview schedules were designed to extract opinions regarding the feasibility of the Anchor Approach in a naturalistic school setting.

The staff schedule considered four key areas: (1) opinions of the Anchor Approach; (2) how well the Anchor Approach works; (3) how realistic and costly (in terms of time and economic costs) programme implementation is; (4) how easily the intervention and accompanying resources can be adapted to meet the needs of the school.

The parent schedule explored: (1) awareness of the Anchor Approach and feedback on resources; (2) perceived impact of the Anchor Approach on their child in school and at home; (3) impact of the Anchor Approach on communication with their child and members of staff.

Full interview schedules details can be found in Supplementary Appendix A (staff interview schedule) and Supplementary Appendix B (parent/guardian interview schedule).

12 schools were contacted between the end of January to late April 2022, of which six schools participated: five junior schools and one secondary school. From these schools, 4 parents, 12 staff (7 teachers, 3 SENCOs, 1 cover supervisor, 1 trainee teacher) and 4 CAMHS staff were interviewed (N = 20).

Participants were recruited through opportunistic sampling via an email to staff and parents in participating schools. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) team members were also recruited to provide insight on the comparative impact of the Anchor Approach.

Each school was provided with an email to be distributed to staff and parents containing an information sheet explaining the research, and a link to an online consent form where they could share their availability for a focus group.

Focus groups were conducted digitally on Microsoft teams between April and mid-June. Groups were organized for parents and staff separately and allocation was determined by availability. Participants were allocated to minimize same-school membership where possible, ensuring privacy. Each group lasted approximately 45 min (range = 22–65 min, mean = 45).

The focus group commenced with a standardized introduction, detailing the research and reminding participants of their ethical rights. Staff were reminded at the start of each focus groups that all voices are valued equally. A working document was shared so participants could contribute any additional thoughts or notes, if they felt uncomfortable expressing these with the group. Anchor approach resources were also attached where participants requested.

The interview schedules were used to direct the topics of conversation and were adapted based on the natural shift of the conversation. Follow-up questions were asked to confirm details mentioned by participants. After the focus group, participants were debriefed. Results were transcribed automatically by Microsoft Teams, checked and anonymized manually by a researcher.

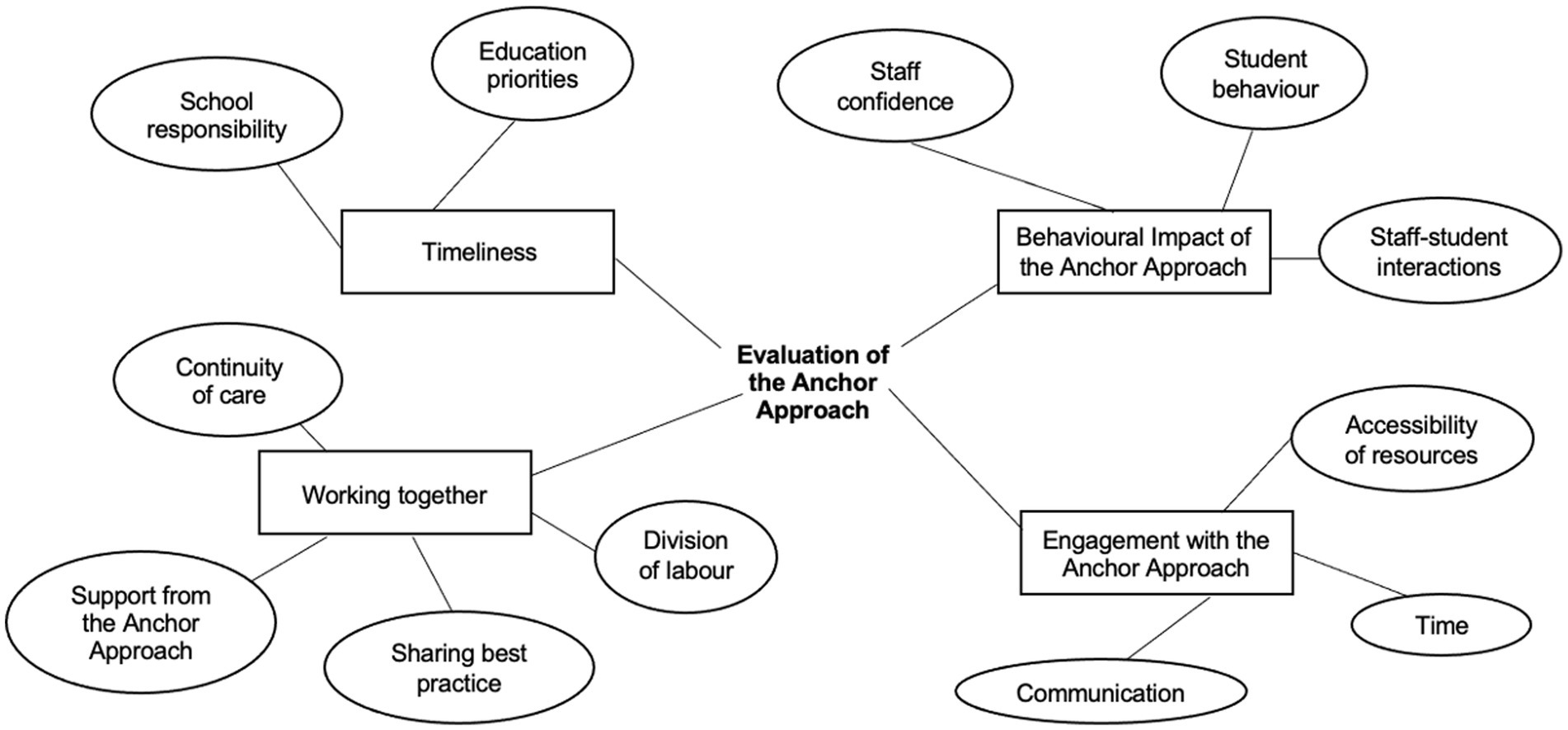

Transcripts were reviewed by two reviewers (IR, JM) using Braun and Clark’s (Smith, 2015) inductive and deductive method of qualitative analysis and a list of key themes were agreed. Four key themes emerged about the acceptability, efficacy, and feasibility of the Anchor Approach. These themes were (1) “Timeliness,” (2) “Behavioural Impact of the Anchor Approach,” (3) “Engagement with the Anchor Approach,” and (4) “Working together.” Each theme was also broken down into twelve associated codes (see Figure 1 for a full display of themes and codes).

Figure 1. A Thematic map of the themes (timeliness, working together, engagement with the Anchor Approach, and behavioral impact of the Anchor Approach) and codes identified through seven focus groups. Boxes representing themes, circles respective codes.

Staff, parents, and CAMHS staff were aware of both the need for emotional support for students and the current limitations in emotional support provided within schools, recognising the timeliness of the intervention. Participants felt that schools hold responsibility for student well-being, agreeing on a need to pivot away from punitive measures. Staff recognized that student behavior needed to be understood for change to occur, and CAMHS staff confirmed that this change was evident between Anchor Approach schools and non- Anchor Approach schools.

CAHMS 4: “…their kind of behaviour management is still quite shame based… very much speaking down to them…it just so happens that this is one of the schools that did not have the Anchor Approach.”

CAMHS 3: “it was clear in kind of the language and tone that was used when talking about behaviours like whether they were spoken as like a problem behaviour or this child needs some support.”

The Anchor Approach provided “novel” (Staff 11) alternatives to punishments, suggesting the intervention may be beneficial for changing interactions with challenging students.

Staff 4: “…I do not anymore hear “Oh my goodness, he’s the most awful child” …there is much more of an understanding… “and I had a discussion about what’s going on at home,” “and I had a discussion about how he’s feeling” and so I think that is a very gradual move.”

CAMHS also identified more responsibility taken by staff rather than relying on external support through a shift in education priorities. Information at referral appeared more detailed, allowing CAMHS to spend more time on complex cases. In this way they suggested that the message of the Anchor Approach “echoes” (CAMHS 1) into wider, systemic, effect. This may demonstrate a cognitive and behavioural shift in understanding and communicating within staff.

CAMHS 3: “… more information about kind of what, well, things have gone well, things that have not… things that have been tried and, and people who have been involved….”

Prioritising the intervention was distinct in some schools, as school policy was changed directly. Embedding the intervention in a systematic and long-lasting way welcomed by staff.

Staff 4: “We are actually also sort of in the process of rewriting our behaviour policy. Based on [the Anchor Approach], I mean ours is such a sort of a sanction-based behaviour policy which now just does not fit with the way that we are working in school.”

In others, there was a feeling of cynicism (Staff 11) from older staff, described as “militant” (Staff 12) in their desire to follow original school policies rigidly, neglecting a new approach to education. In these situations, staff felt empowered by the Anchor Approach to evidence their choices when not supported by other staff/school policy. Some participants still believed in punitive punishments, not internalising the intervention aims. Although benefits were recognised, negative perceptions remained, including feelings of dislike and that students “deserved” (Staff 12) punishment. It may be unrealistic to expect a full change toward an emotion-centred response to disruptive students, as it is worth remembering staff are also only human.

Staff 11: “…the emotional capacity that you are gonna dedicate to, like, pastoral stuff is always gonna be limited.”

A range of behavioral impacts were identified, especially improvements in staff confidence. Staff appreciated having additional “strategies” (Staff 1, Staff 3) when responding to students. Having the ability to draw on the ‘evidence-based practice’ was also “reassuring” (Staff 2) when communicating with parents. This enabled them to highlight disruptive behaviors without apprehension, orienting conversation toward working together with the child.

Staff 2: “…it’s just having that sort of theory to back you up on why you are doing things.”

Staff 2: “…it was definitely really helpful, in that instance, and to be able to, you know, speak with the parents and them know that I, as much as I could, I understood how they were feeling….”

Similarly, some parents reported confidence in expressing thoughts using shared language.

Parent 2: “…you are always as a parent trying to figure out how to say what you want to say… And you are always wondering if you can convey, something that you want to express to them in a way that they’ll understand….”

The language also increased confidence in CAMHS when conversing about well-being strategies, without feelings of chastising teachers and an awareness of shared understanding. It alleviated personal responsibility for getting responses ‘right’ and increased confidence in provided strategies.

CAHMS 4: “…knowing if the schools had the training as well… you are on the same page, which has been quite helpful.”

Student behaviour also demonstrated improvements – staff reported improved attendance and attributed this change to higher personal responsibility, better emotional control and greater feelings of belonging. Emotion coaching in particular was mentioned several times in this context (e.g., Staff 3).

Staff 7: “…the attendance thing… it’s not just that we are aware, they are aware as well, that we kind of hold them to account and care about them truly.”

Some parents also reported changes in behavior (better ability to communicate about emotions), although they were less clear on Anchor Approach relations. Children showed active introductions of Anchor Approach concepts (Parent 1, Parent 2).

Parent 1: “talking about at the end of the day how she was in the blue and the green and the red…like quite clear that was going on.”

However, not all parents identified prominent behavior improvements in children related to the intervention (Parent 3). This may mean that engagement may not be universal, or differences in levels of communication between families.

Regarding staff-student interactions, staff felt more confident to recognize and understand the context behind student behavior and react appropriately to the situation. This improved relationships and created a cultural shift, allowing staff to reach out about non-academic subjects, which students welcomed.

Staff 2: “it’s a more positive way to be interacting with children than sort of shouting, um you know, being strict and firm.”

Engagement was high across most participants, however in some cases barriers were identified such as a lack of time. Staff, CAMHS and parents all noted limits to their schedules, especially needing to work additional hours (systemic problem).

CAMHS: “…when teachers have a lot going on and they feel like they are already at full capacity then even to think about something, even if it, no matter how easily presented it is, can feel too much.”

Parent 3: “…none of us have got time to go in and, you know, spend 2 h at school going through this.”

Due to “jam packed” (Staff 10) workloads, there were cases where staff needed more emotional resources for themselves than offering them to students due to increased stress. This revealed a need for the Anchor Approach to consider teachers’ well-being.

Staff 10: “Maybe we need some Anchor Approach!” and Staff 11: “Yeah, we need some Anchor Approach.”

In some instances, teaching assistants would need to use their personal time for training, meaning only those with high interest may be attending sessions.

Staff 3: “…they [teaching assistants] had to opt-in like voluntarily and I think they were paid to stay, but still, it’s not their directed time, so it’s still a choice for them, which made it a little bit difficult with all staff being on the same page…”

However, the Anchor Approach team offered additional training sessions and so this may be a school-specific organizational issue.

When the Anchor Approach was being used only with disruptive students rather than the whole cohort, the whole-school impact on behaviors was minimized. The main reason was reported to be work pressure as classroom time was difficult to manage in comparison to talking to a student individually.

Staff 2: “…it’s kind of our ‘trauma children’ that we really do um, use this approach for….”

Staff 3: “… it’s easier and it’s not right, but it’s easier just to shout and say like “stop doing that,” than to take them out and have a chat with them….”

This demonstrates that in some cases the Anchor Approach was utilised as a last resort, going against intervention aims in replacing punishment with understanding.

A ‘cost–benefit’ analysis of time spent on training and usefulness was identified, with the approach generally considered to have higher benefits than costs.

Staff 2: “Those hours that you spend in the training have probably saved a lot, a lot more time along the way.”

Accessibility of resources was a major concern to engagement. Materials provided were easily digestible, praised and widely used.

Staff 2: “…rather than bombarding them [student teachers] with the enormity of your behaviour policy… they can have a look through this and it really does, it’s easy to digest, it’s really user friendly and I still refer back to it at times.”

Despite their believed usefulness, participants at times felt overwhelmed by the number of resources. There was a preference for shorter materials within staff and parents when responding to upset children.

Parent 4: “I cannot go through like 4 sheets of paper working out which of the behaviours it most fits and what I need to do.”

Feedback may be due to lack of direct engagement between intervention and parents, lessening their awareness and/or confidence using resources.

Another barrier to engagement included mixed feelings reported about communication. Parents stressed a general lack of knowledge about the Anchor Approach. Some attempted to learn about it using external resources (Parent 1, 2, 3), demonstrating proactive engagement and interest in methodology, not currently met by the Anchor Approach team.

Parent 2: “If we are to participate as parents as well as the basic families in that one, I just need to understand.”

There were also concerns about accessibility and acceptability of resources regarding parents from low SES backgrounds, or whom English was a second language, feeing unable to participate in discussions.

Staff 1: “The understanding you know, and also some of them [parents] kind of keep back as well because they do not understand our school system or they think that you know their English is not good enough so we would not necessarily get that good engagement.”

On the other hand, group differences primarily seemed to be between those who had/had not received training, suggesting the language used is not universally approachable, but teachable.

Parent 4: “Oh, I have not seen that [the shared language sheet], that, that looks really useful [laughs]!”

Participants were highly in favor of working together through the ‘whole-school’ approach. However, this was not always present, and some individuals felt undervalued and rejected, unable to effectively provide support.

To provide continuity of care, staff reported they needed to communicate the needs of students between themselves and believed in displaying a supportive community.

Staff 8: “…if we took all of our students where we have identified they have an issue, and if we pass that on to other people. So it’s like a schoolwide approach would be really, really helpful…”

Unfortunately, in some schools it was evident this continuity did not exist; only providing training to one year group, form-time teachers or teaching staff. This impacted the ability to enable changes. There were concerns that without shared strategies, students could “crack again” (Staff 7), resulting in a reversal in intervention effects.

Staff 7: “…So it will be incredibly helpful if the whole staff body were aware of what, what to do in the classroom with said student and how to approach….”

As mentioned, those who wanted to be more centrally involved (CAMHS and parents), felt they could not continue the care outside the school setting.

CAMHS 4: “I’ve never been involved in that [the Anchor Approach meeting] and I cannot actually picture what that looks like…”

Parent 4: “…I felt that like as a parent, it’d be really great to be following the same kind of, the same procedure if you like, and reinforcing and supporting that at home.”

There were clear divisions of labor: senior staff overseeing activities, pastoral staff supporting disruptive students, teaching staff focusing on classes as a whole. This assisted staff to review approaches, making more informed decisions over student care. The dilution of responsibility aided CAMHS in distributing their resources to students who required more support as they felt confident referring schools to the Anchor Approach for system-wide changes, allowing them more time to focus on individuals or classes.

CAMHS 1: “…we are only, you know, our team can only do so much. So when you have got somebody like the Anchor Approach that can go into a school and do a whole staff training, that takes such a, not a weight, but it means that we can do other things….”

CAMHS and staff were also interested in sharing best practice between each other and across schools, such that they could both feel confident that the Anchor Approach was working and share success with other teachers.

CAMHS 1: “It puts the training into action then. But I think if you do not have that, then you, you do not see the training.”

Several participants mentioned importance of teamwork for understanding materials and brainstorming strategies. Conversations were an important factor in making the intervention work, helping change the dialog about disruptive students.

Staff 7: “that sort of discussion forum really helped the most for us.”

Lastly, support provided by the approach team was consistently praised.

Staff 4: “I mean my engagement personally with the Anchor Approach team has been fantastic… I find them really easy to communicate with and they always reply.”

Participants felt more confident that the team could get back to them quickly on any queries and were available to support schools on specific cases.

The aims of this study were to (1) explore perception of the impact of a resilience-based whole-school intervention (the Anchor Approach) to improve school engagement, and (2) to explore school intervention sustainability focusing on perceptions of intervention (a) acceptability, (b) efficacy, (c) feasibility, and (d) flexibility and adaptability. Key themes found included the timeliness of the intervention, impact on the school setting, engagement, and working together.

Schools were shown to be well-placed facilities for resilience provisions, as students could manage emotional difficulties more efficiently following whole-school resilience-based implementations. This was shown by improved abilities in communicating emotions with parents and staff and lowered classroom disruptions, which suggests resilience improvements as demonstrated in past literature (Knapp et al., 1999; Aburn et al., 2016). High resilience has been recognized to buffer against mental and physical distress (Richardson, 2002; Vance et al., 2008), and so the intervention may have wider impacts on the wellbeing and quality of life in students (Beecham, 2014; Luthar and Ansary, 2005; Wilkins et al., 2015). Alongside resilience, the intervention demonstrated improved attendance, responsibility and engagement with extracurriculars, replicating previous findings on school engagement (Finn and Rock, 1997; Luthar and Ansary, 2005).

The whole-school approach of the intervention was integral to student and staff-related outcomes; staff described feelings of positive and improved well-being, and student behavioral change was consistently reported by both internal staff and external CAMHS agents. Comparatively, where minimal staff practiced the intervention they reported high levels of stress, lower capacity/interest in implementing changes, and punitive measures, demonstrating strong evidence that a whole-school change in ethos is required for effectiveness, acceptance and treatment fidelity.

Parents were identified as important in reinforcing the intervention at home. However, they felt under-utilized, reflecting the importance of partnership between internal and external populations, to help close the typical “parent-school gap,” when developing whole-school interventions.

High staff buy-in and confidence was demonstrated, suggesting acceptability of the intervention, which is key to intervention success (Banerjee et al., 2016; Bruhn and Hirsch, 2017). However environmental concerns, such as staff time were also raised. Additionally, there was some push-back on terminology used in the associated resources, which were seen as excluding those from lower SES backgrounds. As such the acceptability of the resources provided and contextual factors may be worth further consideration. For successful changes to appear in improving resilience, the ‘whole-school’ approach is vital. This relies on cooperation between all members involved, including parents reinforcing the intervention at home; whereby before cooperation can be achieved, mutual understanding between different stakeholders is needed. To determine if an intervention is utilized as intended, staff needs to be paneled (Bruhn and Hirsch, 2017) and facilitators and barriers can be assessed, helping to improve the intervention on a system level. Parents are also significant stakeholders reinforcing the intervention using home resources (Banerjee et al., 2016). By collecting opinions from those implementing and supporting the intervention, it is possible to identify which dimensions are important for specific outcomes (Fitzpatrick et al., 2013).

In terms of efficacy, the intervention was consistently applauded as successful in supporting emotional regulation and meeting developmental needs. No reported differences in number of referrals to mental health services were noted, which may suggest no measurable differences in behavioral difficulties. However, referral quality significantly improved, which supported mental health services in working with specific students who required additional support. This may be important regarding the research of impact; although more students were not referred for mental health support, those who were potentially received a more efficient response, as services were more familiar with individual student needs.

Long-term follow-up is necessary to confirm an intervention is fit for purpose (Banerjee et al., 2016), and this has been confirmed here; the intervention reached feasibility of over six years and demonstrated a saturation of ideals across the schools interviewed. Positive results were found in reductions in classroom disruptions and in CAMHS referral efficiency. Several schools did not report whole-school changes in ethos or behavior, due to associated large time commitments in implementing the intervention. This was related to the feasibility of the number and complexity of resources. Additionally, part-time staff especially were not able to attend all training, limiting their engagement, presenting a concern as fidelity.

The flexibility and adaptability were not commonly discussed, but in some cases the intervention was adapted for use directly with students. Exercises were provided during form time or support sessions, suggesting good adaptability of resources. However, the associated high workload with the intervention meant, by necessity, it was diffused across many school staff. Also acknowledging pedagogy has high attrition rates, these factors influence flexibility; teachers must be familiar enough with the intervention to modify it without sacrificing core principles (Han and Weiss, 2005), and have an in-depth understanding of programme effectiveness. Once staff achieve this understanding, they can recognize the limits in which the program can be modified (McLaughlin and Mitra, 2001), then independently continue using resilience-based methods with students. This would assist with internalising the methods, constituting a successful intervention, and decreasing a reliance on external assets. There is currently little room for within the intervention to fit the resources available to school, however this may be due to the specific participating schools as they have a higher student population than average, which will not be representative of the wider population.

Although a good sample size was recruited, the qualitative nature of the study may limit generalizability. In particular, the sample may have been skewed by participation bias toward an interest in the Anchor Approach. However due to the widespread use of the intervention across multiple schools in the borough this is unlikely. Furthermore, conclusions in relation to mental health service referrals are anecdotal, so should be extrapolated with caution. Quantitative data is needed to confirm whether the Anchor Approach has a significant impact on child health.

This study has demonstrated that whole-school resilience approaches are viable across several settings and across longer periods of time as identified by the staff providing these interventions. Uses and barriers to use were also identified amongst this population which can be considered for future development.

The prevalence of child and adolescent mental health risk has shown a consistent increase in emotional problems over the past 20 years (Collishaw et al., 2004; Collishaw et al., 2010). According to participants these difficulties are likely to increase further over the next few years. As such, the Anchor Approach (or similar whole-school resilience approaches) may provide increasing value and importance for schools going forward.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the UCL Research Ethics Committee (21415.003). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

IZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. NA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Public Health team in Haringey council and undertaken independently by UCL (the Resilience Research Group).

Our thanks to Ceri May and Susan Otiti from the Public Health team at Haringey Council and Haringey Council for help and support on this project. Also, the schools, school staff, CAMHS staff, and parents in Haringey borough who shared their own experiences of the whole-school resilience approach in focus groups.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1544199/full#supplementary-material

Aburn, G., Gott, M., and Hoare, K. (2016). What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan.12888

Allen, M. (2014). Local action on health inequalities: Building children and young people’s resilience in schools. London: Public Health England, UCL Institute of Health Equity.

Arnow, B. A. (2004). Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65, 10–15

Banerjee, R., McLaughlin, C., Cotney, J., Roberts, L., and Peerebom, C. (2016). Promoting emotional health. Wales: Well-being and Resilience in Primary Schools.

Beecham, J. (2014). Annual research review: child and adolescent mental health interventions: a review of progress in economic studies across different disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 714–732. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12216

Bond, L., Toumbourou, J. W., Thomas, L., Catalano, R. F., and Patton, G. (2005). Individual, family, school, and community risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in adolescents: a comparison of risk profiles for substance use and depressive symptoms. Prev. Sci. 6, 73–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3407-2

Brendtro, L. K., and Brokenleg, M. (2009). Reclaiming youth at risk: Our Hope for the future. London, UK: National Educational Service.

Bruhn, A. L., and Hirsch, S. E. (2017). From good intentions to great implementation. Report Emotional Behavioral Disorders Youth 17:70.

Collishaw, S., Maughan, B., Goodman, R., and Pickles, A. (2004). Time trends in adolescent mental health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 1350–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00335.x

Collishaw, S., Maughan, B., Natarajan, L., and Pickles, A. (2010). Trends in adolescent emotional problems in England: a comparison of two national cohorts twenty years apart. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 885–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02252.x

Dray, J., Bowman, J., Campbell, E., Freund, M., Wolfenden, L., Hodder, R. K., et al. (2017). Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56, 813–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780

Durlak, J. A. (2015). Studying program implementation is not easy but it is essential. Prevention Sci. 16, 1123–1127. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0606-3

Fergusson, D. M., and Woodward, L. J. (2002). Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 225–231

Finn, J. D., and Rock, D. A. (1997). Academic success among students at risk for school failure. J. Appl. Psychol. 82, 221–234

Fitzpatrick, C., Conlon, A., Cleary, D., Power, M., King, F., and Guerin, S. (2013). Enhancing the mental health promotion component of a health and personal development programme in Irish schools. Adv. School Ment. Health Promot. 6, 122–138

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol. 18, 12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Goldberg, J. M., Sklad, M., Elfrink, T. R., and Karlein,, &, Schreurs, M. G, Bohlmeijer, E. T., and Clarke, A. M. (2019). Effectiveness of interventions adopting a whole school approach to enhancing social and emotional development: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ., 34, 755–782, doi: 10.1007/s10212-018-0406-9

Gus, L., Rose, J., and Gilbert, L. (2015). Emotion coaching: a universal strategy for supporting and promoting sustainable emotional and behavioural well-being. Educ. Child Psychol. 32, 31–41.

Han, S. S., and Weiss, B. (2005). Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 33, 665–679. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7646-2

Johnson, J. L., and Wiechelt, S. A. (2004). Introduction to the special issue on resilience. Subst. Use Misuse 39, 657–670

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., and Poulton, R. (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder developmental follow-Back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709

Knapp, M., Scott, S., and Davies, J. (1999). The cost of antisocial behaviour in younger children. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 4, 457–473. doi: 10.1177/1359104599004004003

Leonard, S. S., and Gudiño, O. G. (2021). Beyond school engagement: school adaptation and its role in bolstering resilience among youth who have been involved with child welfare services. Child Youth Care Forum 50, 277–306.

Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2015). The relationship between school climate and mental and emotional wellbeing over the transition from primary to secondary school. Psychol. Well-Being 5. doi: 10.1186/s13612-015-0037-8

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. J. Sch. Health. 74.

Luthar, S. S., and Ansary, N. S. (2005). Dimensions of adolescent rebellion: risks for academic failure among high- and low-income youth. Dev. Psychopathol. 17, 231–250

Martin, A. J., and Marsh, H. W. (2008). Academic buoyancy: towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. J. Sch. Psychol. 46, 53–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.01.002

Marzano, R. J. (2007). The art and science of teaching: A comprehensive framework for effective instruction. Alexandria, VA: ASCD Publications.

McLaughlin, M. W., and Mitra, D. (2001). Theory-based change and change-based theory: going deeper, going broader. J. Educ. Chang. 2, 301–323. doi: 10.1023/A:1014616908334

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., and McGorry, P. (2007). Adolescent health 3 - mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 369, 1302–1313.

Reimers, T. M., Wacker, D. P., and Koeppl, G. (1987). Acceptability of behavioral interventions: a review of the literature. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 16, 212–227. doi: 10.1080/02796015.1987.12085286

Richardson, G. E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 58, 307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020

Smith, J. A. (2015). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods, 1–312. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Suhrcke, M., Pillas, D., and Selai, C. (2007). Economic aspects of mental health in children and adolescents. Europe.

Ungar, M., and Liebenberg, L. (2013). Ethnocultural factors, resilience, and school engagement. Sch. Psychol. Int. 34, 514–526.

Vance, D. E., Struzick, T. C., and Masten, J. (2008). Hardiness, successful aging, and HIV: implications for social work. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 51, 260–283

Wells, J., Barlow, J., and Stewart-Brown, S. (2003). A systematic review of universal approaches to mental health promotion in schools. Health Educ. 103, 197–220.

Keywords: school, school children, resilience, intervention, qualitative research

Citation: Zak IK, Rubens I, Abbott N and McGowan J (2025) A qualitative evaluation of a whole-school approach to improving resilience in childhood and adolescence. Front. Educ. 10:1544199. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1544199

Received: 12 December 2024; Accepted: 25 March 2025;

Published: 08 April 2025.

Edited by:

Raquel Artuch Garde, Public University of Navarre, SpainReviewed by:

Marija Jevtic, University of Novi Sad, SerbiaCopyright © 2025 Zak, Rubens, Abbott and McGowan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer McGowan, amVubmlmZXIuYS5sLm1jZ293YW5AdWNsLmFjLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.