94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 25 March 2025

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1537034

This article is part of the Research TopicExtended Education - Leadership in PracticeView all 5 articles

Introduction: In European countries, the emphasis placed on Extended Education (EE) differs not only in practice but also in policies and literature. In fact, there are still no standardized concepts or definitions of this specific educational area.

Methods: The aim of this study is to contribute to a transnational understanding of EE by inductive content analysis of essential documents from five different countries. The results of this study will facilitate a better understanding of shared factors which can be used to improve student access, success and retention in education, generate valuable guidelines for effective leadership and highlight the potentials of public governance for social innovation. As part of the Erasmus+ project “EKCO” (Extended Education Facilitating Key Competences through Cooperative Learning), a research team consisting of local experts in the field of EE from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland and Austria was asked to provide a selection of local literature on EE that they considered particularly relevant. A total of 19 documents were submitted from the five countries. In the present study, the expert sampling was subjected to an inductive content analysis using MAXQDA software to identify the salient points that emerged from the sampling.

Results: The results indicate that five main categories can be identified in the EE literature offered, namely: (1). Factors influencing EE, (2). Institutions and structure, (3). Pedagogical requirements, (4). Content of EE and (5). Factors influenced by EE.

Discussion: The analysis of the data shows that, despite national differences, there are common intentions, processes and structures that are productive for the development of key competences and future skills. Moreover, the interplay of these factors should be considered when discussing EE. The article discusses how national EE policies can learn from the diversity of their structures, processes and intentions.

“Extended education flourishes all over the world” (Bae, 2019, p. 153). In most countries around the world, schools - in various forms - are given the task of supporting pupils beyond the traditional lessons - be it in terms of professionalization (see Holmberg, 2021), health and resilience (Murray et al., 2024), learning (Entrich, 2020; Noam and Triggs, 2018), inequality (Bae et al., 2019) or their leisure behavior, to name just a few examples. Internationally, such offers are often discussed under the heading of EE (Schüpbach, 2019).

In this context, very different expectations, structures and processes emerge. These are subsumed under EE, which can be understood to mean the following, for example:

“[.] we can tentatively define programs and activities in the field of extended education as activities and programs that are based on a pedagogical intention and organized to facilitate learning and educational processes for children and adolescents that are not (completely) covered by school-curriculum-based learning and that aim at fostering academic achievement or success in school, or in general at accumulating cultural capital in a broader sense” (Stecher et al., 2018, p. 77).

While in economics it is almost an existential threat not to learn from and analyze the national experiences and circumstances of other countries in the world (Steffen and Oliveira, 2018), countries remain rather isolated in their educational systems or focused on their national circumstances (see Ecarius et al., 2013). The EU is taking first steps to make national education systems more transparent and accessible. For example, comparative reports and overviews of national education systems are published on the Eurydice information network (European Commission, n.d.). It can be seen that many areas of education are approached and structured in different ways and many aspects still seem to be specific to individual countries. For innovation in the education sector, we consider it fruitful to compare different systems in terms of their intentions, structures and processes. In section 2, a transdisciplinary analysis will draw on insights from sociological, socioeconomic, organizational and educational disciplines to better understand the role of governance in EE. Section 3 presents a two-step analysis of EE in five different countries (Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Norway, Sweden). The selection of the countries was based on their participation in the EKCO (Extended Education Facilitating Key Competences through Cooperative Learning) project. Firstly, the participating experts in EE were asked about key documents (from science, policy and practice) in order to obtain country-specific information on intentions, structures and processes. Subsequently, central foci of these documents were condensed using a qualitative content analysis in order to obtain inputs for the further development of EE in a contrastive comparison. Finally, section 4 will discuss the results of the study and highlight the potentials of governance in EE.

Extended education is a broad term that encompasses organized leisure time, recreational time, learning support and tutoring (Bae, 2019) as well as health, nature and creative learning settings that are typically not embedded in regular school curricula and thus not graded (Stecher, 2018). In contrast to formal education or schooling, EE can be seen as institutionalized informal education. While still following curricula and concepts, it can focus on social and emotional skills, play and student well-being that complement other school related skills and knowledge (Holmberg, 2021). Schüpbach defines EE as follows:

“Extended education represents a multitude of programs/activities/offerings, among other things, that provide children and adolescents with a range of supervised activities designed to encourage learning and development, for children to be supervised and safe, and extending the regular school day. Some of them pursue general goals, such as psychological well-being and social competence, others focus on specific educational outcomes and goals. They are extracurricular, meaning that they are non-credential and voluntary. They can be offered in school-, faith-, and community-based settings, for any age range, and can be held before school (in the morning), between school hours (lunchtime), after school (afternoon), on weekends, or during school vacation” (Schüpbach, 2019, p. 135).

Extended education teachers1 engage with students during and outside of class hours, however, in contrast to regular teachers they are not in charge of teaching school curricula, student achievement and grading. Instead, they focus on aspects such as planning and facilitating meaningful leisure time and recreation, and thereby the development of personal and social skills, offering supervised free play situations and providing learning opportunities outside of graded school subjects (Ecarius et al., 2013; Holmberg, 2021, Noam and Triggs, 2018). In some countries EE teachers have completed a different type of pedagogical training than schoolteachers, with an emphasis on pedagogy, communication, social skills and recreation amongst others rather than subject matter and methodology (see Fischer and Loparics, 2020).

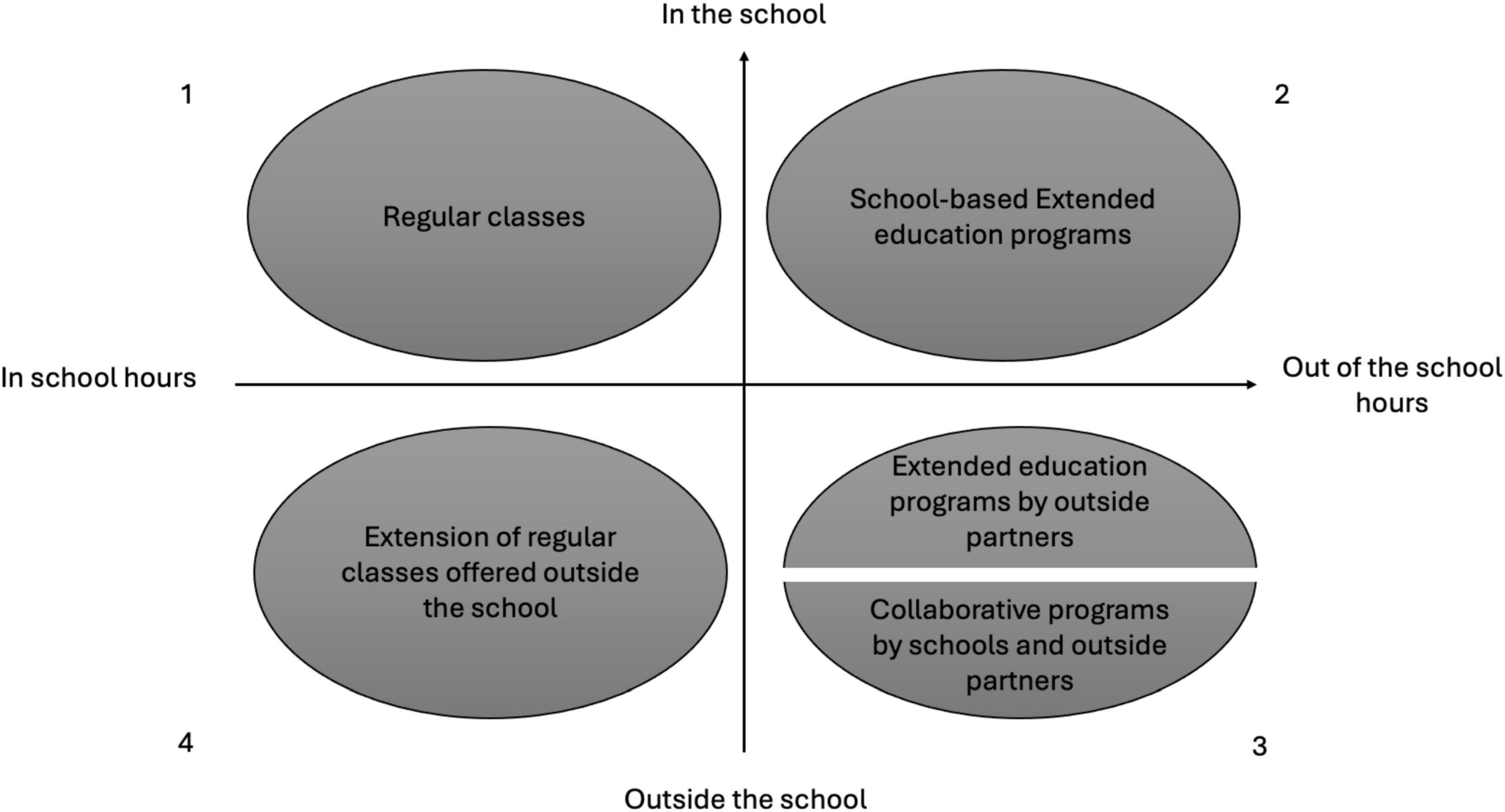

Depending on the respective country policy and institutional setting, EE teachers can work with public or private schools, either as part of the school staff or in separate institutions that often collaborate with schools. Figure 1 presents an overview of the various professional settings EE teachers work in.

Figure 1. Scope and field of extended education (EE) [replicated from Bae (2019), p. 161].

Extended education moves on a spectrum of no relation to school’s regular curricula activities and leisure programs that take place outside of school hours and a strong relation, when EE supports innovations in education, such as student-centered teaching or all-day schooling (Bae, 2019). Educational policy provides the conditions for EE collaboration with other educational institutions, making it a stakeholder of varying importance. Depending on the organization of formal and informal learning in education systems additional terms are used to describe extended education, such as all-day schools in German speaking countries, afterschool or out-of-school in the United States, leisure-time-oriented programs in Scandinavian countries or cram schools in Japan, Taiwan and Korea (Noam and Triggs, 2018, p. 171). Particularly in school models that include EE in school hours, as is the case in all-day schools, EE teachers collaborate closely with school leaders and thereby become facilitators of the all-day school design. The term shadow education is used in extended education that primarily encompasses academic training that is aimed at increasing student achievement and children’s opportunities in education (Cipollone and Stich, 2017).

The rapidly growing field of EE is mirrored by growing attention in an emerging field of research on the processes, outcomes and specific issues of EE. The role of learning that takes place outside of formal education in school has been analyzed through a pedagogical and organizational lens on education (Bae, 2019; Stecher, 2018), a sociological perspective on inequality in education (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990; Ecarius et al., 2013; Holmberg, 2021, Noam and Triggs, 2018), anthropologically (Campbell, 2009) as well as economically, focusing on the role of private stakeholders and market dynamics in education (Bray, 2007; Cipollone and Stich, 2017; Wilkins and Olmedo, 2019). The role of leadership, particularly governance, can support the understanding of the interplay of institutions and stakeholders in education and shed light on how EE is embedded in the education system.

Governance is defined as the cooperation between different public, private and non-governmental stakeholders (Wilkins and Olmedo, 2019, p. 5) that, in contrast to more hierarchical leadership styles of educational institutions and education policy, include stakeholders of varying power and leverage (e.g., Tikly, 2017). Governance allows collaboration between involved actors that play different roles in educational processes, that can present a more diverse and specialized understanding than hierarchical leadership processes in education. From a global perspective, governance has the potential of fostering participation and partnerships across public and private sectors for the greater good (Unterhalter, 2024). Governance can be seen as a collaborative response to state led or market-based failures, such as ineffective top-down steering, or the protection of self-interest in competitive markets (Wilkins and Olmedo, 2019, p. 5).

Schools work collaboratively with various stakeholders within the education policy frameworks to provide quality education, leisure time and care. Stakeholders can entail EE, social work, psychologists and medical staff, learning aid, legal and political representatives, sport, music, nature, art, parent clubs, cultural clubs, as well as teacher training and professionalization, amongst others. They characterize the institutional structure in which education takes place and can vary both nationally and regionally, depending on the legal frameworks of the education system and regional interactions between stakeholders.

Hierarchical leadership structures in educational institutions run the risk of overlooking possible avenues for developments of collaborations with involved actors and stakeholders, due to insufficient insight and information in centralized leadership models. Educational governance includes economic, institutional, governmental, legal, regional and international actors, amongst which EE represents one, that collaborate in a variety of constellations of educational networks on (inter-)national and regional scales (Maag Merki and Altrichter, 2015). Governance perspectives emphasize that a variety of social processes, stakeholders and actors are involved in education, honoring (1) their respective resources and expertise as well as (2) the complexity of the education system, while acknowledging the challenge of coordinating involved parties effectively (Ittner et al., 2021, p. 7; Wilkins and Olmedo, 2019, p. 6). Other drawbacks of governance processes are the difficulty to ensure participation and distribution of power between stakeholders and that “participatory policy processes are not captured by local power elites” (Torfing and Triantafillou, 2013, p. 17). Rather than a normative proposal for governance practices in EE, an analysis EE through a governance lens can help identify the circumstances, actors involved, existing resources, and needs in education to promote knowledge transfer between education systems and institutions and thereby maximize the potential of current EE models.

Maag Merki and Altrichter (2015) identify the following criteria as central in the analysis of educational governance:

• Theoretical pluralism

• Pluralism of data on education systems, educational practices social norms, values and beliefs

• Pluralism of research methods

• An analysis of interdependencies between actors and the education system, e.g., through the study of curricula and legal frameworks

• A broad scope that includes historical, political and social dimensions in their specific socio-cultural context

• An analysis of the education system

Studying educational governance requires theoretic pluralism, such as systems theory, policy-network theory, institutional theories, rational choice theory, or organizational theories (Ittner et al., 2021, p. 7).

This includes the emergence of new public governance, which is characterized by the gradual incorporation of market-based management techniques into the education sector (Mezza, 2021, p. 30). New public governance holds potential for social innovation (Sørensen and Torfing, 2015) When leadership in new public governance follows principles of collaboration and networking, knowledge can be transferred between involved stakeholders and regional and school specific needs can be met more precisely. Another emerging discourse that employs a similar lens is called democratic professionalism (Noordegraaf, 2020; Sachs, 2016). It stresses the importance of an ecosystem approach in education that understands the interdependency of collaborations between educational institutions, teachers and school-stakeholders (Mezza, 2021, p. 31). Both perspectives highlight the potentials of governance in education.

From a sociological perspective, the role of EE as a provider of childcare and informal education plays an important role for parents’, specifically mothers’, opportunities in social and economic contexts. “[E]xtended education, as a social institution, is part of the ecology of the entire society” (Bae, 2019, p. 158). As EE stretches between offering supervised leisure time including cultural and health related activities, to learning support, such as tutoring or assistance with homework, language, reading tasks, etc., it can be seen as a commodification of household resources. The provision of informal education and childcare is unevenly distributed across genders, socio-economic and socio-cultural backgrounds. The access to informal education contributes positively to students’ educational attainment and consequently their educational and professional (Cipollone and Stich, 2017; Entrich, 2020). Access to EE for all students, not only widens the scope of children’s educational, social and cultural experiences but it may raise the equality of opportunity in education for children of disadvantaged family backgrounds.

The aim of this study is to identify differences, similarities and challenges in EE across countries. The insights can be used to improve student access, success, and retention in education, generate valuable guidelines for effective leadership, and highlight potentials for social innovation in the public sector.

The data collection was carried out as follows: experts from the countries participating in EKCO (see section “1 Introduction”) were asked to submit documents from the fields of policy, practice and research that were as meaningful as possible and that illustrate what extended education is in their countries and which challenges exist. These documents were translated using DeepL. After the analysis, the results were presented to the experts to rule out any linguistic misunderstandings.

This was followed by using the qualitative data analysis method called “inductive qualitative content analysis” (Mayring, 2022) to find out which factors emerged as central in relation to EE in the sample obtained. Since inductive content analysis allows a systematic investigation that reduces complexity but generates a broad understanding of the phenomena referred to Mayring (2010), p. 65 it was the appropriate methodological approach for this research. For the content analysis, the MAXQDA 24 software was used, which allows thematic data analysis (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2023).

For the inductive content analysis, the approach of expert sampling (purposive sampling) was used. Expert sampling is applied when people with specific expertise in a particular area are required in the sample (Teddlie and Yu, 2007). Therefore, expert sampling relies on the expertise of the people chosen. Teddlie and Yu (2007) describe the scope as follows: “For example, a purposive sample is typically designed to pick a small number of cases that will yield the most information about a particular phenomenon [.]” (p. 83). However, the selection of experts is often a challenge (Marquardt et al., 2019). In this research project, the participating expert teams were asked to provide a selection of local literature on EE that they considered relevant (see Table 1). The experts were asked to provide documents from practice, research and policy documents (see Table 2). They were also asked to submit as comprehensive a view as possible of the strengths and areas of development of extended education. It can be argued that they are suitable because they have already had ample evidence of their suitability for participation in the ERASMUS+ project. An advantage of expert sampling is that these individuals typically possess a more profound comprehension of the subject matter (Marquardt et al., 2019), coupled with an expansive view of their respective national research domain, due to their expertise and involvement in the field. Moreover, this expert sampling provides valuable insights into the diverse national education systems across countries, highlighting their unique characteristics. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware that expert sampling may be susceptible to research bias, which could affect the reliability of the results (Berndt, 2020).

A total of 19 documents were submitted by the experts. Seven of these documents were research work (e.g., literature review, reports, qualitative analysis). Six of the documents submitted could be identified as pedagogical-didactic frameworks of individual schools or projects for school practice and a further six were policy documents, including legal texts, curricula or commentary on national curricula (Table 2).

The research is based on the core criteria for qualitative research proposed by Steinke (2012): Intersubjective traceability is ensured by disclosing all decisions in all phases of the research process. The presentation of the indication of the research process has already been described in the key points here. The findings were linked to the empirical material and any limitations were disclosed. Coherence and relevance are always discussed. The researcher from Austria who selected the data was not involved in the categorization of the data in order not to violate objectivity.

In qualitative research, “validity” and “reliability” are defined and evaluated differently than in quantitative research. In this context, “validity” refers to whether a research finding actually captures the phenomenon it purports to measure. It ensures that the chosen methods, such as interviews or observations, provide the relevant data needed to answer the research question. In the case of the present research, which is internationally comparative, documents selected by local experts on policy and practice appear to be an ideal approach to identifying and defining similarities and differences in policies across countries. Reflection on the researcher’s point of view was achieved through member checking, in which the results were presented to and discussed by the international experts in order to minimize bias and achieve as accurate a representation of social reality as possible. No misunderstandings were found. “Reliability” in qualitative research is not understood as the reproducibility of results as in quantitative research, but rather as the consistency and transparency of research methods and decisions. This means that the research process is documented in such a way that it can be understood by others and, if necessary, replicated. This includes a detailed description of data collection and analysis, as well as a clear reflection on one’s own position and possible factors influencing the research. In the present research, this was achieved by having the study design and contact with the international experts carried out by a different person than the one who carried out the evaluation. The evaluator was not involved in the selection of experts and documents and is new to the field. The presentation of the results described above ensured that there were no misunderstandings during the evaluation.

Regarding ethical considerations, all persons involved were informed about the purpose of the research and the documents were provided voluntarily, unless they are publicly accessible. Internal school documents are not cited to ensure anonymity.

First, the documents which were predominantly written in the local language were translated into English using the “DeepL” translation software and an overview of the translated documents was created. After the organization and the translation of the documents, the analysis process started with the examination of the content. Categories were formed inductively in a close reading of the documents’ content (Mayring, 2021). Recurring terms, main topics, paragraphs, or headings were recorded as categories. For example, if a paper dealt with the topics of well-being and life opportunities in connection with EE, the two categories of well-being and life opportunities were formed. The documents were read individually, and more codes developed gradually. Categories were added and adapted over the course of the reading process and after several readings relations and contradictions between categories were identified. When content saturation was reached, the categories were divided into logical main and sub-categories. In the end, five main categories emerged from the 19 documents (Figure 2).

The content analysis resulted in five main categories with a total of 1,632 allocations of all categories:

As illustrated in Figures 1, 3 categories were identified by paying attention to their respective levels and the interplay between the categories. The following sections provide a detailed examination of the five primary categories: (1) Factors influencing EE, (2) Institutions and structure, (3) Pedagogical requirements, (4) Content of EE and (5) Factors influenced by EE. In general, the focus in the submitted documents was on organizational topics, different requirements as well as on content and design concepts. Table 3 summarizes the categories and their corresponding subcategories. This section presents each category individually, and discusses its respective subcategories and examples from the analyzed literature.

Factors influencing EE includes factors that have an influence on the organizational, didactic or content design of EE. The following subcategories were identified:

a) Political framework and legal organization

b) Principal, schoolteachers and school conditions

c) Parents and socio-economic status

d) Age

The factor “Age,” for instance, will affect not only the duration of time children spend in the institution, but also the specific content designed to meet their expectations and needs. Furthermore, it can also determine the degree of teacher involvement and the role that educators are expected to assume in the early education of these children.

The national conditions in the countries seem to have a particularly strong influence on the design of EE, as they specify EE conditions at the state level. Document 1, for instance, addresses the issue of insufficient resources for EE: “One particular factor is based on the fact that for several years, leisure education has been severely under-prioritized on both the social and educational policy agenda. Major cutbacks in the leisure education area, as well as an increased focus on longer school days and school performance, have dominated and had an impact on the everyday life of the leisure education institutions, the time spent with the children and young people as well as a lack of financial and staff resources.”

It is also important to consider the impact of the parents and their socio-economic status, as outlined in Document 8: “As women to a greater extent are employed and work outside the home, there is a need for expanded childcare in many countries. To meet modern families’ way of life requires good quality childcare – an important part of this is various forms of EE.”

The socio-economic status is often mentioned in the documents in connection with financial issues of EE. While in some countries, there are basic fees or supplementary services, which results in some families being unable to afford these options due to their socio-economic status, in other countries, initiatives are being implemented with the objective of reducing these inequalities through the allocation of state funding to EE. Furthermore, the inequalities that have been caused can be found in the documents: “Children’s right to a placement in [EE-Institution] is legally governed by the parents’ need for care, which means that children who have parents who are unemployed or on parental leave do not have a legal right to a place in [EE-Institution]” (Document 8). Document 8 additionally emphasizes in this respect: “The national report highlights that the inequality of to what extent children attend [EE] is related to family’s different socioeconomic background. Children who live in vulnerable areas more often do not have access to [EE].”

These explanations show that EE is often used by national education systems to respond to educational policy needs. The focus on improving performance or addressing social inequalities point to the compensatory role EE could assume. The following explanations show in which ways internal school factors could partially thwart this mission.

Finally, the school leaders, schoolteachers and school conditions were identified as influencing factors. At the EE teacher level, for example, the different qualifications of EE teachers are mentioned as having an impact on EE. Document 15 reports on the effects of the use of social workers on EE: “They found that while most social workers offered free-play programs and ensured that homework was completed without well-targeted assistance, they seldom offered extracurricular programs.”

At the school management level, it is the respective visions and leadership. Document 9 describes the influential role of school leadership in establishing shared goals and conditions for collaborations: “leaders influence pupils’ learning for example, by promoting a vision and goals and by enabling teachers to have the resources to teach well. Further, shared goals and effort are emphasized concerning professional learning communities, and a supportive leadership is highlighted as being especially important for this.”

Furthermore, it is stated that: “professional development as a long-term process, emphasizing the need to provide [EE] staff with ongoing support in the professional development process for instance, by the principal.” With regard to school conditions, it is mentioned that organizational problems in particular, such as a lack of time resources or coordination difficulties of EE teachers with schoolteachers, have an impact on EE: “A lack of time resources is apparently quite often a limiting factor for cooperation at all-day schools” (Document 17), highlighting communication issues in hierarchical structures within educational institutions.

The findings clearly show that the goals and policies of EE are quite similar between the different countries, but the structures are significantly different, which leads to different challenges. In this sense, transnational learning could have a supportive effect.

“It would be short-sighted to conclude that all-day schools cannot be effective. Rather, it is highly likely that such results can be linked to the currently inadequate forms of their design (personnel, organizational, pedagogical, financial)” (Document 17).

Due to the document types, it is not particularly surprising that a lot could be found on organizational framework conditions. Descriptions of various types of offerings were found not only in the general curricula, but also in the individual school descriptions. Therefore, the three subcategories “Guidelines, organization and systems,” “Values, rights and mission,” and “Design of the offer” were derived. The Curricula or framework concepts of all-day schools often started with the description of the values, rights and tasks associated with school and specifically with EE. A more detailed description of the subcategories “Guidelines, organization and systems” and “Design of the offer” can be found below.

The documents showed that “scaffolding” of EE was an important issue, which includes historical forms of EE as well as reports on different forms of EE in different countries. The current national structures were recorded in particular. Some of the uploaded documents report on the system, the organizations or the structure of the national responsible institutions in great detail. The national structures for EE differ in many respects within the five countries, with different terms being used for EE itself. A clear distinction from the school system can be found in the literature, for example in Document 8: [EE] should be “something other than the school” or “It is often stressed that education in [EE] is something else than education in, for example, school.” This shows that the learning opportunities provided within EE are regarded to be different from formal education fostered in school.

It was not uncommon for documents to deal with issues such as funding, infrastructure design, responsibilities or timing, leading to the following subcategories being identified:

a) Infrastructure and rooms

b) Financing and costs

c) Time and time structure

d) Leadership, management and teams

e) Communication and exchange

Particularly often, predefined timetables or explanations of the tasks within the individual time blocks could be found. The design of individual EE organizations depend largely on political regulations, school conditions (see section “4.5 Factors influenced by EE”) and funding. In terms of funding, considerable differences were found between countries. While in some countries, childcare is fully financed by the state, some regulations entail various surcharges for specific services or for the entire EE program.

The organization’s staff on both, the school staff and leadership level, appears to be particularly relevant here. The documents frequently report on the tasks and responsibilities of the principal or various teams (e.g., pedagogical teams, support teams, steering groups, working groups). Internal school communication and exchange is also frequently addressed at an organizational level, with regular meetings, team meetings, WhatsApp groups or feedback loops, for example, being an integral part of the organization of EE in the system descriptions for exchange. The exchange with all parties involved is considered a key factor in many documents, whereby the task of fruitful cooperation is also mentioned at the pedagogical level (see section “4.3 Pedagogical requirements”).

“To ensure good interaction between the numerous actors of all-day school forms, meaningful and appropriate communication (regarding learning progress and tasks to be completed) between the teachers of the teaching part and the care part and the parents/guardians is necessary” (Document 16). Here too, it can be seen that different systems produce different communication structures which can lead to coordination issues between and within organizations.

In the documents, a distinction was often made within the (curricular) design of EE between learning time and leisure time or supervision. This included, for example, the descriptions of “afternoon or morning care,” and their corresponding responsibilities and conditions. Document 12 offers an example: “Morning supervision is generally limited to supervising children who come to school before the start of block times. As morning supervision is not subject to any specific requirements, a specially qualified supervisor does not necessarily have to be employed.”

The divergent understandings of EE are reflected in the different structures offered. While some documents focus on learning and school support, others also talk about pure supervision tasks or child-managed play. As explained in Document 11: “The term “child-managed play” refers to play that is organized by children themselves. EE teachers might initiate play by making time, locations, and equipment available, but the choice and management of activities are entrusted to the children.”

However, in some documents a mixture of both areas, in which different content blocks of learning time and free time alternate was also mentioned. An illustrative example can be found in Documents 8: “In the [EE] care and education should be combined” and Document 6: “The supervision part is divided into two parts, learning time and free time. These two parts can be organized separately from lessons or combined with them.”

In general, this main category includes issues that relate specifically to EE teachers’ requirements, such as qualification processes in EE, organizing and planning their EE lessons, or interacting with different parties. In general, the documents focus on didactic approaches to EE, the qualification of EE teachers, different forms of cooperation (both, on an intra-institutional level and with external parties, parents or institutions) and the extent of involvement in EE teaching. In the documents attention was paid to the pedagogical and didactic arrangements and their circumstances. In this context, the following subcategories were derived:

a) Didactic methods, tasks and tools

b) Teacher’s qualification

c) Cooperation (internal and external)

d) Teacher-student relationship

e) Teacher’s involvement

The subcategories are explained in more detail in the following sections.

Commonly addressed topics could be found in connection with the “didactic methods, tasks and tools.” This subcategory has a pretty high number of second-order subcategories which reflects the different didactic approaches and claims in the countries. Thirteen different second-order subcategories were identified, which in addition to different teaching approaches also include, for example, the teacher-student relationship. The second-order subcategories are presented in the following list:

a) Ensuring a good environment

b) Pedagogical concept and planning

c) Different learning environments and activities

d) Knowledge transfer and learning support

e) Care and supervision

f) Diversity and inclusion

g) Child-centered education

h) Promotion of independent learning

i) Balance between activity, recreation and rest

j) Introduction to local communities, environments and values

k) Value transfer

l) Group-oriented teaching

m) Experiential learning

In some documents, particular emphasis is placed on the fact that the pedagogical requirements within EE should arise from children’s needs. These text passages were collected as “Child-centered education.” Document 5 shows: “Teaching in school-age educare shall stimulate pupils’ development and learning and offer pupils a meaningful way to spend their free time. This shall be done through teaching based on pupils’ needs, interests and experiences, as well as by continuously challenging pupils by inspiring them to make new discoveries, or “Teaching shall be adapted to the circumstances and needs of each pupil.” In other documents, the importance of group-oriented teaching is highlighted, as evidenced in Document 8: “Group-oriented teaching refers to joint learning and learning by and together with others is emphasized rather than individual learning. Teachers are involved in learning activities together with children they investigate, explain, and develop knowledge.”

These are not the only demands placed on EE teachers. The texts further mention that EE teachers are also expected to find a balance between activity, recreation and rest and to introduce the children to the local community, culture and values. In addition, a task of EE teachers seems to be to ensure a good environment for children, as described in Document 1: “The pedagogical professionalism seems to fundamentally rest on a pedagogy that creates good communities where all children and young people can participate and get involved.”

Furthermore, the promotion of independent learning, which means that the teacher does not explicitly explain the content to the children, is also mentioned in several documents: “Teachers in the supervision part should support pupils to such an extent that the children’s independent performance is guaranteed” (Document 16). The role of the teacher extends beyond mere knowledge or value transfer, as evidenced by the fact that “care and supervision” appear to be an additional responsibility in EE. This task is defined in Document 8 as follows: “an important aspect of [EE] teachers’ work is relationships. In the [EE] care and education should be combined.” Document 10 for instance describes that: “[EE] shall maintain and meet children’s needs for care, safety, well-being, sense of belonging and validation.”

“This concept refers, among other things, to the fact that it is important that the staff is trained and committed to leisure education” (Document 1).

In addition to the existence of a range of didactic approaches, the literature also reveals significant discrepancies in the expectations placed on the training and qualification of EE teachers. While documents 1 and 11, for example, attach great importance to teacher competences and qualifications, document 15 also mentions forms of EE that include social workers without specific pedagogical training. Document 15 describes this as follows: “Social workers working at all-day schools in [country] are mostly involved in the care setting before and after lessons and at lunchtime. They have different educational backgrounds, e.g., a bachelor’s degree, a completed childcare apprenticeship, or no specialized education.”

Due to the consistent mention, two separate subcategories were created for the topics of “Professional development and support” and “Flexibility.” The former is often recorded in the literature within concept descriptions of EE institutions or statutory curricula. In particular, internal exchange and ongoing training are mentioned as a way of organizing ongoing development and internal support. Document 18 states this as follows: “Teachers: 15 h of further training must be completed.”

The necessity for EE teachers to demonstrate considerable flexibility in EE is emphasized by the requirement for a broad and readily accessible repertoire within their EE teaching. Changes can occur spontaneously, particularly when working with children and young people and EE teachers should be able to respond flexibly to them. The following three passages in the documents could provide evidence for the subcategory “flexibility”:

• “The educator should be able to adapt the teaching in that way and let the pupils decide” (Document 2).

“Pedagogical tact implies awareness of the child’s experiences and involvement in the subjectivity of the other: To exercise tact means to see a situation calling for sensitivity, to understand the meaning of what is seen, to sense the significance of this situation, to know how and what to do, and to actually do something right” (Document 11).

• “Since pedagogical tact and understanding are connected to a particular practical situation, it is impossible to establish an exact set of rules or skills for the teacher. To act tactfully, the teacher must have integrated a form of practical and professional pedagogical wisdom” (Document 11).

In terms of guaranteeing the quality of teaching staff, leadership responsibility is frequently highlighted (see section “4.1 Factors influencing EE”), whereby the principal is held responsible for initiating and ensuring quality assurance measures, discussions with colleagues or support measures, for example. Moreover, the competences and skills of EE teachers should also be made possible through internal support from colleagues and the school management. The following can be found in Document 9: “… professional development as a long-term process, emphasizing the need to provide [EE] staff with ongoing support in the professional development process for instance, by the principal.”

Despite the diversity of documents and national differences, it is clear that a great deal of responsibility is delegated to EE teachers and which points to the role of their training, skills and actions for EE quality. This is in line with the frequently cited work on the role of teachers by Hattie (2023). While there are different attitudes toward existing institutional structures and the problems associated with them, the different education systems seem to describe this in a standardized way.

Cooperation is closely related to the previous topic of internal support and emphasized in the literature as a crucial factor in early education. The documents highlight not only the importance of teamwork within EE institutions but also the collaboration with parents and external organizations. The literature recognizes both internal cooperation within the school and partnerships with external entities, including communication with parents.

The notion of collaboration between EE teachers and schoolteachers from the school system appears to be a recurrent theme throughout the documents:

• “Collaboration between staff members is a key factor in attaining professionalism in [EE]” (Document 9).

• “Teachers in schools and [EE], though must cooperate to create the best possible conditions for pupils’ development and learning” (Document 8).

• “(…) Ensuring that pedagogues and teachers collaborate in the most fruitful and effective way during students’ hours in school” (Document 4).

• “It is important that the tasks are carried out in regular consultation between the teachers of the teaching part and the supervision part (learning time)” (Document 16).

The relationship between EE teachers and the children is frequently mentioned in the documents. The extent to which EE teachers are involved in EE is referred to particularly in the context of the children’s freedom to make decisions and organize their own time. The teacher generally plays an important role in the documents and is ascribed various functions in EE. From a non-involved supervisor, who should only intervene in individual situations to a confidant and playmate, or an authority figure that transfers knowledge to learners, various forms of teacher involvement can be found. The teacher should adjust the degree of leeway granted depending on the needs and age of the children. The ability to find the appropriate level of involvement or degree of freedom is often mentioned in connection to teacher’s qualifications and their flexibility (see section “4.3.2 Teacher’s qualification”).

The documents provided extensive information on EE content. For instance, within the curricula received, the content was clearly defined at the state level, outlining the requirements that should be included in EE in the participating countries. “Content of EE” exhibited the greatest variety in descriptions, and it seems there is still no consensus on the core content of EE. Consequently, five subcategories were created to represent the variety of thematic focuses:

a) Activities and playing

b) Community and socializing

c) Active participation, responsibility and independence

d) Space and care

e) Development and learning

The following sections provide a detailed description of these subcategories.

The two subcategories, “Activities and playing” and “Community and socializing,” are presented together in this analysis due to considerable overlap in the documents. Both appear to play an important role in which EE content was mentioned in the documents. What they have in common is that both sub-categories include all content that is not aimed at learning at school, and although learning is not the main focus here, it does not mean that nothing is learnt.

The documents indicate that the activities conducted in EE provide an opportunity for learning, the development of social skills and the testing of one’s own identity: “In all-day schools, collaboration, tolerance and socially appropriate forms of interaction are developed, and communication skills are promoted” (Document 16).

This category emphasizes the promotion of community and social learning. Consequently, helping each other, listening to each other, making friends and overcoming conflicts are often cited as EE content in documents that emphasize social learning. “Opportunities to develop new friendships seem crucial across the board. For both children and young people, leisure education seems to provide access to and opportunities to be with friends” (Document 1).

Within “Activities and playing,” a separate (second order) subcategory called “Time outdoors” was created to highlight the significant role time spent outdoors plays in the documents. Scientific studies pointed out: “Play and activities seem to be of great importance regardless of age, partly as something you do together and partly as something that creates experiences of joy and satisfaction for yourself” (Document 1).

A total of 14 out of 19 documents dealt with each of these two content categories (“Activities and playing” and “Time outdoors”) and they appear in all countries participating in this study.

The content of “Active participation, responsibility and independence” is also featured in almost all documents. Document 2, for example, provides the following information: “Participation is part of democracy, and it incorporates concepts such as inclusion and influence. It is related to pupils’ possibility to have a say, make themselves be heard and to influence activities, actions and decisions in the school.” (Document 2).

Involving children in decision-making processes is focused on as follows: “When involving children more in making different decisions and carrying out various activities, children take more initiative. Educators say they have a greater focus on children’s resources, as the didactic approach is oriented toward enlarging what actually was a success for the children. So, with the children’s participation we also see a renewal of educational practice” (Document 2).

This passage illustrates the relationship between participation, responsibility and independence. In addition to the content, the impact of participation on children (see section “4.5 Influenced factors by EE”) is also outlined, as are the didactic requirements to facilitate active participation (see section “4.3 Pedagogical requirements”). Hence, if the objective is to guarantee child-centered education that is responsive to children’s needs, it seems imperative for the children to be actively engaged in decision-making processes.

The assumption of responsibility is an inherent aspect of self-determination and freedom. Documents 13 and 18, for instance, indicate that a distinct children’s parliament is established for this objective, with the intention of simultaneously imparting democratic values. “The children’s parliament meets once a month and discusses topics relevant to the children. They can express their needs/wishes/complaints here” (Document 13).

This shows that democracy and the active participation of children are seen as important contents in EE.

The subcategory “Space and care” consists of EE content that focuses on the provision of space. EE should create spaces in which children can experience safety and care, and where they can be themselves. In Document 1, for example, EE is described as a place “[…] where there is space and time.” “Having a good time is placed in the context of leisure education as the physical place where there is space and experiences of freedom and leisure, as well as experiences of co-determination and influence” (Document 1).

In contrast to the aforementioned subcategories, “development and learning” focuses on teacher’s professional development and learning. Again, there is considerable variation in the focus of the content included in the documents. Some national curricula, for instance, designated content and competences for EE are listed that are similar to those typically encountered in school settings, such as “Mathematics and Construction,” or “Digitization and Technology.” Other documents include a diverse range of learning content, that includes personal development, values, social norms and a healthy lifestyle. The topics collected in this sub-category are as follows:

a) Creativity and curiosity

b) Food, health and lifestyle

c) Awareness of values, norms and rules

d) Facing challenges and new skills

e) Personal development

f) Projects

g) Digitization and Technology

h) Ecology and environment

i) Mathematics and Construction

j) Reading and relaxing

k) Communication and language

As previously noted in “section 4.2 Institutions and structure,” EE concepts are frequently distinguished from school concepts. This perspective is also reflected to some extent in the learning content. In addition to school-related learning content, EE content revolves around the promotion of curiosity, creativity, new skills and hobbies. Document 16 includes references to personal development and self-confidence: “In this context, the main aim is to strengthen self-confidence and self-esteem. Children learn to assess themselves and recognize their own strengths and weaknesses. They develop concepts and strategies to overcome their weaknesses and build on their strengths. The pupils’ self-confidence and ability to empathize are promoted in equal measure.”

The final main category “Factors influenced by EE” encompasses factors that are influenced by EE. The following subcategories were derived from the documents:

a) Well-being

b) Development

c) Academic performance

d) Life opportunities

e) School climate, attitude and behavior

f) Belonging, social learning and inclusion

The documents described expected effects of EE on children’s and young adults’ academic performance, their school-related behavior and attitudes as well as the school climate. Documents 2, 11 and 15, for example, indicated that school-related behavior, attitudes and academic performance are influenced by pupils’ “active participation.”

The subcategory “Development” is distinct from “Academic performance” as it contains those effects of EE that are not only centered around academic performance, but go beyond by including social, emotional and cognitive aspects. When considering EE’s influence on children’s development and on their “Life opportunities,” documents mention short-term and long-term effects: “Childcare that complements family and school life offers children stability and security and promotes equal opportunities for children of different social and cultural backgrounds, languages, religions and genders” (Document 12).

The documents pay special attention to the categories “Well-being” and “Belonging, social learning and inclusion.” EE can have an impact on the sense of belonging and the development and maintenance of friendships, which in turn promote inclusion. These potentials also point to the key challenges that emerged in all participating countries, namely that the children who would benefit most from EE are not always the ones who participate - especially children from families with low incomes and little formal education, with languages other than the national language often experience limited access to EE. Document 1 reports that: “[…] research has emphasized the importance of this community element for young people who attend a leisure or youth club. A community where experiences of belonging and being included, hanging out with friends, and being with pedagogues who are good to talk to and who respect you, have been highlighted in several Nordic studies.”

Some factors within this sub-category are related to one another. For instance, well-being is mentioned in relation to belonging, social learning and inclusion. “[…] relationships and socializing are emphasized as important conditions in leisure education that both promote well-being and prevent unhappiness” (Document 1).

Finally, the documents name some content-related dimensions, such as active participation and collaborative decision making are expected to have an influence on pupils’ well-being. “Well-being thus also seems to be linked to the children’s experiences of freedom to choose what they want to do in their free time. Being able to decide for themselves, to choose how the afternoon and evening should take place outside the school setting, is found several times in the research interviews across ages and different leisure education institutions” (Document 1).

The aim of this study was to gain an understanding of what is particularly important in transnational research on EE, to learn from different national structures, processes and intentions of EE and to derive recommendations for leadership, policy and educational institutions.

First, limitations of this research should be mentioned. In particular, the literature on EE is limited to the participating countries in the Erasmus+ “EKCO project,” Austria, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Future studies should analyze further countries by building on the five EE categories identified in this study: (1). Factors influencing EE, (2). Institutions and Structure, (3). Pedagogical requirements, (4). Content of EE, (5). Factors influenced by EE. Another limitation is that the project’s research team was deliberately selected for research on EE and was therefore responsible for the selection of the documents (expert sample), which could have led to a subjective selection that is guided by interests. However, the clear advantage of this approach is that linguistic differences have provided access to literature that is not English. The documents from the partner countries were provided in the original language, which made it necessary to rely on the computer-generated translations done by “DeepL” prior to the analysis. The translations are, however, considered adequate for the purpose, as the experts affirm the results for their own countries.

The five categories identified in this research offer five key recommendations for educational policy on a national and at the EU level:

1. Factors influencing EE: Extended education has been established in all countries for many years, even if it has had a longer tradition in some countries and has been rolled out more recently in others as part of political innovation programs. Legal and organizational difficulties such as different employers or unclear regulations should therefore be reviewed and revised as far as possible. Cooperation between different countries and institutions could facilitate knowledge transfer and successful concepts can be adopted. This would help to establish a supportive structure in the schools. Support for schools regarding school development and accompanying research also appears to be necessary, as some countries have set up broad accompanying research and some hardly have any studies to show for it. Similar to teaching, specific responses are needed for specific student characteristics such as language skills and socio-economic status.

2. Institutions and structure: The importance of EE has been highlighted in the previous sections. The document analysis shows major intranational differences in all countries regarding spatial and staffing resources and costs. It seems necessary to establish minimum standards to reduce these differences as far as possible. The importance of organization within schools was also emphasized in all countries – educational governance should offer exchange formats, further training and organizational development based on good practices.

3. The results highlight the need of a further development of institutional autonomy to adapt to current local contexts and needs and increased cooperation between school, EE and other involved stakeholders, such as parents or social workers. This would allow for a more effective use of resources (time, infrastructure, staff) and support innovative and equitable practices in EE (Sørensen and Torfing, 2015). This quest is supported by governance perspectives that stress the importance of enabling self-governance of institutions (Wilkins and Olmedo, 2019). Educational policy should provide goals that serve the common good and that allow autonomy of individual schools as well as the creation of networks on the local, national and supranational level. Institutional structures that support “regulated self-regulation” (Torfing and Triantafillou, 2013, p. 15), can help reduce complexity, coordination issues and quality assurance in leadership processes that are characterized by collaborative networks of institutions and other stakeholders (Wilkins and Olmedo, 2019). Finally, from an equity perspective, leadership should pay attention to the access to and distribution of participatory power and leverage of influential stakeholders in educational institutions to mitigate marked-based power dynamics that run risk of excluding people of disadvantaged backgrounds (Torfing and Triantafillou, 2013, p. 17).

4. Pedagogical requirements: At the pedagogical level, the qualification of staff should be specified. While some of the analyzed countries require a qualification at the academic level as a standard, others employ unqualified staff. An EU-wide minimum standard would be necessary to improve the quality of children’s education. Likewise, organizational development within educational institutions must be promoted at this level to improve the cooperation of educators. This points to the role of school leadership and teacher appraisal, as well as the provision of quality initial and in-service teacher training, in the continuous development of staffs’ pedagogical competences and organizational cultures that are responsive to their contextual needs.

5. Content of EE: The core content of EE is discussed very differently in the various countries, but there also seem to be debates within the countries. While in some countries the goal is “learning,” others promote the self-determination of children. It is recommended to use these differences as inspiration for a lived diversity of content, since in contrast to teaching, EE is based on voluntary offers, personal and community-based interests as well as access of individuals to EE.

6. Factors influenced by EE: Numerous student characteristics are said to be influenced by EE – such as well-being, personal development, academic performance, life opportunities, school climate and social belonging including inclusion in the documents. This content, as outlined above, is shared by all countries, even if there is variance. It is recommended that the governments consider pedagogical requirements and offer clear and beneficial framework conditions, resources and training, as well as programs to promote organizational development. In addition to that, the comparative analysis has shown difficulties in access to EE in all participating countries – the ones who could benefit the most do not always have the opportunity to participate in EE.

This study points to an increasing institutionalization and decentralization of informal education (care, leisure time, learning support, cultural, social, personal and health related activities) through the collaborative provision of education by different stakeholders. Consequently, educational leadership on the school, local, national and international level needs to ask new questions, such as: (1) What is the role of EE institutionalized informal education? (2) What are the goals of EE? (3) What are the characteristics of the student and staff body? (4) Which aspects need to be further developed? (5) Which resources and practices do already exist in the network of professionals in EE? (5) In which ways can collaborative efforts and training support the provision of quality EE? And (6), at which governmental level can these developments be best be governed?

These results provide clear indications of where further research and governance efforts could be directed at both the transnational and national level. On the academic level, transdisciplinary sociological and organizational analyses could shed more light on the emerging field of EE (see Maag Merki and Altrichter, 2015) and on possible avenues to support education quality and equality of opportunity in education (Bae et al., 2019; Entrich, 2020; Holmberg, 2021; Cipollone and Stich, 2017). From a gender perspective, the role of EE in institutionalized childcare could be examined further to offer insight on the relationship between social, economic and educational opportunities of children’s primary caregivers, who are predominantly women (Berghammer et al., 2019; Felderer et al., 2006; Schierbaum and Ecarius, 2022; Zartler et al., 2011). On a social level, the facilitation of access to health (Murray et al., 2024), cultural and social learning opportunities in EE (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990; Noam and Triggs, 2018) could be studied more closely. On a leadership level, a governance perspective could support the effective allocation of expertise to the demands of EE and allow the implementation of solutions that are tailored to specific institutional or regional contexts. This can provide insights for policy development and raise new questions for quality assurance and professional training. Recommended policy and organizational guidelines that promote social innovation and collaboration through governance practices are the (1) adaptivity to current contexts and needs, (2) pragmatic and realistic use of available resources, (3) a distribution of power to allow autonomy and support self-management of educational institutions and involved stakeholders, (4) horizontal integration of all stakeholders to share needs and ideas, (5) collaboration to pool resources, and (6) the integration of diverse groups (Sørensen and Torfing, 2015).

This paper identified five central categories of EE: The first category contains factors that shape EE, such as national frameworks or educational policy structures. Three categories were identified that describe structures and processes: the institutional structures, pedagogical requirements and EE content. The fifth category describes effects of EE, such as the well-being of children and young people, or the promotion of educational opportunities and positive effects on student performance. These categories should not be considered as isolated but understood in relation to one another by paying attention their interaction. The potential outcomes of EE depend on policy structures in the same ways that EE content and design is based on EE teacher competence, leadership support and the quality of collaboration with internal and external stakeholders. A governance perspective shows that EE is influenced by a multitude of conditions and that the overall design of EE in the countries is influenced by their respective political circumstances. Consequently, a standardized solution or a cross-national approach will not necessarily yield the same results in every country. However, there is potential for mutual learning and knowledge transfer through the study of individual approaches of the countries. Another important contribution of this paper is to provide an understanding of possible blind spots in the current overall discourse on EE. In effect, it can be surmised that there are areas that are not sufficiently addressed in the existing research on EE. These include the promotion of equal opportunities for children of disadvantaged family backgrounds, the fostering of critical and creative thinking and the role of educational governance and leadership in providing quality EE.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

BK: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AE: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The project EKCO is co-funded by ERASMUS+. The publication is supported by Johannes Kepler Open Access Publishing Fund and the federal state Upper Austria.

Many thanks to the experts from the EKCO project for providing relevant documents: Andrea Schlian, David Thore Gravesen, Gunn Helen Ofstad, Helene Elvstrand, Inga Kjerstin Birkedal, Kari Stamland Gusfre, Lea Ringskou, Louise Krobak Jensen, Patricia Schuler Braunschweig, Silje Eikanger Kvalø, Synnøve Eikeland, Tim Olsen Levang, Tuula Helka Skarstein, Regula Spirig.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. DeepL was used to translate the documents.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1537034/full#supplementary-material

Bae, S. H. (2019). Concepts, models, and research of extended education. Int J. Res. Extended Educ. 6, 153–164. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v6i2.06

Bae, S. H., Cho, E., and Byun, B.-K. (2019). Stratification in extended education participation and its implication for education inequality. Int J. Res. Extended Educ. 7, 160–177. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v7i2.05

Berghammer, C., Beham-Rabanser, M., and Zartler, U. (2019). “Machen Kinder glücklich? Wert von Kindern und ideale Kinderzahl,” in Sozialstruktur und Wertewandel in Österreich. Trends 1986 – 2016, eds J. Bacher, A. Grausgruber, and M. Haller (Wiesbaden: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-21081-6

Berndt, A. E. (2020). Sampling methods. J. Hum. Lactation 36, 224–226. doi: 10.1177/0890334420906850

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J.-C. (1990). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Bray, M. (2007). The Shadow Education System: Private Tutoring and its Implications for Planners, 2nd Edn. Paris: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Campbell, E. (2009). The educated person. Curriculum Inquiry 39, 371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2009.00448.x

Cipollone, K., and Stich, A. E. (2017). Shadow capital: The democratization of college preparatory education. Sociol. Educ. 90, 333–354. doi: 10.1177/0038040717739071

Ecarius, E., Klieme, L., Stecher, and Woods, J. (eds) (2013). “Extended education—an international perspective,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Extracurricular and Out-of-School Time Educational Research, (Opladen: Barbara Budrich), 7–26. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvdf0hzj

Entrich, S. R. (2020). Worldwide shadow education and social inequality: Explaining differences in the socioeconomic gap in access to shadow education across 63 societies. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 61, 441–475. doi: 10.1177/0020715220987861

European Commission (n.d.). Eurydice. Available online at: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/.

Felderer, B., Gstrein, M., Hofer, H., and Mateeva, L. (2006). Kinder, Arbeitswelt & Erwerbschancen: Fertilität und Beschäftigung - Work Life Balance der Frauen in Österreich aus ökonomischer Sicht. Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS).

Fischer, O., and Loparics, J. (2020). Specialised professional training makes a difference! The importance and prestige of typical duties in all-day schools from the perspective of teachers, leisure educators, principals and coordinators of extended education. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 8, 211–226. doi: 10.25656/01:26574

Hattie, J. (2023). Visible Learning: The Sequel: A Synthesis of Over 2,100 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, 1st Edn. Milton Park: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9781003380542

Holmberg, L. (2021). To teach undercover. A liberal art of rule. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 9, 57–68. doi: 10 2565:26579

Ittner, D. M., Mejeh, M., and Diedrich, M. (2021). “Governance im Bildungssystem: Schulische Governance im Spiegel von Theorie, Bildungspolitik und Steuerungspraxis,” in Handbuch Schulforschung, eds T. Hascher, T.-S. Idel, and W. Helsper (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 1–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-24734-8_13-1

Kuckartz, U., and Rädiker, S. (2023). “Using software for innovative integration in mixed methods research: Joint displays, insights and inferences with MAXQDA,” in The Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods Research Design, ed. C. A. Poth (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications), 315.

Marquardt, K. L., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., and Wang, Y. (2019). What makes experts reliable? Expert reliability and the estimation of latent traits. Res. Politics 6, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/2053168019879561

Mayring, P. (2010). “Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse,” in Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, eds G. Mey and K. Mruck (Berlin: Springer), 601–613. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-92052-8_42

Mayring, P. (2021). Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-By-Step Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Mayring, P. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 13th Edn. Weinheim Basel: Beltz.

Mezza, A. (2021). Reinforcing and Innovating Teacher Professionalism: Learning from other Professions. OECD Education Working Paper No. 276. Paris: OECD.

Murray, S., March, S., Pillay, Y., and Senyard, E. L. (2024). A systematic literature review of strategies implemented in extended education settings to address children’s mental health and wellbeing. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 27, 863–877. doi: 10.1007/s10567-024-00494-3

Noam, G. G., and Triggs, B. B. (2018). Expanded learning. A thought piece about terminology, typology, and transformation. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 6, 165–174. doi: 10.25656/01:21635

Noordegraaf, M. (2020). Protective or connective professionalism? How connected professionals can (still) act as autonomous and authoritative experts. J. Professions Organiz. 7, 205–223. doi: 10.1093/jpo/joaa011

Sachs, J. (2016). Teacher professionalism: Why are we still talking about it? Teach. Teach. 22, 413–425. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1082732

Schierbaum, A., and Ecarius, J. (eds.). (2022). Handbuch Familie: Band II: Erziehung, Bildung und pädagogische Arbeitsfelder. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-19843-5

Schüpbach, M. (2019). Useful terms in English for the field of extended education and a characterization of the field from a Swiss perspective. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 6, 132–143. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v6i2.04

Sørensen, E., and Torfing, J. (2015). “Enhancing public innovation through collaboration, leadership and new public governance,” in New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research, Palgrave Macmillan UK, eds A. Nicholls, J. Simon, and M. Gabriel (Berlin: Springer), 145–169. doi: 10.1057/9781137506801

Stecher, L. (2018). Extended education – Some considerations on a growing research field. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 6, 144–152. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v6i2.05

Stecher, L., Maschke, S., and Preis, N. (2018). “Extended education in a learning society,” in Informelles Lernen, eds N. Kahnwald and V. Täubig (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 73–90. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-15793-7_5

Steffen, M. O., and Oliveira, M. (2018). “Knowledge sharing benefits among companies in science and technology parks: A cross-country analysis,” in Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM 2018) 1 and 2, 1089–1097.

Steinke, I. (2012). “Quality criteria for qualitative research,” in Qualitative Research: A Handbook, 9th Edn, eds U. Flick, E. von Kardorff, and I. Steinke (London: Pearson), 319–331.

Teddlie, C., and Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 77–100. doi: 10.1177/1558689806292430

Tikly, L. (2017). The future of education for all as a global regime of educational governance. Comp. Educ. Rev. 61, 22–57. doi: 10.1086/689700

Torfing, J., and Triantafillou, P. (2013). What’s in a Name? Grasping new public governance as a political-administrative system. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 18, 9–25. doi: 10.1080/12294659.2013.10805250

Unterhalter, E. (2024). Soft power in complicated and complex education systems: Gender, education and global governance in organisational responses to SDG 4. Int. Rev. Educ. 70, 547–573. doi: 10.1007/s11159-024-10098-2

Wilkins, A., and Olmedo, A. (2019). Education Governance and Social Theory. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Keywords: extended education, leadership, governance, content analysis, international comparison

Citation: Krepper B, Efstathiades A and Loparics J (2025) Learning from the diversity of national structures, processes and intentions with regard to extended education. Front. Educ. 10:1537034. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1537034

Received: 29 November 2024; Accepted: 28 February 2025;

Published: 25 March 2025.

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Marie McQuade, University of Glasgow, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Krepper, Efstathiades and Loparics. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James Loparics, amFtZXMubG9wYXJpY3NAcGh3aWVuLmFjLmF0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.