- Emirates College for Advanced Education, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

This project sought to increase fathers’ involvement in their children’s literacy development through interactive shared reading at home. Parent–child home reading is not a traditional practice in the UAE, and reading attainment is below international standards for children attending state schools. During workshops in Kindergarten schools, simple techniques were shared with fathers for reading picture books in Arabic and English with their bilingual children. Fathers were provided with books to take home to read for pleasure and for information with their children. Recommendations arising include providing guidance on the selection and provision of diverse, contemporary, culturally relevant picture books; holding nationwide reading workshops for both mothers and fathers; and increasing school-home liaison to encompass parents within the literacy development ecosystem in the UAE.

Introduction

This policy brief offers actionable recommendations for policymakers based on the findings from a research and development project which had two broad aims: firstly, to foster language and literacy development through father-child interactive shared reading at home, and secondly, to increase fathers’ involvement in their young children’s development, while building their sense of competence, confidence, and wellbeing. The study took place in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates where there is growing interest and research in early childhood education and developing the literacy ecosystem. With the approval of the school authorities, eight public school kindergarten principals in both urban and suburban settings were approached for their support. All agreed to participate in the project by providing school facilities for the research team to conduct the workshops and by inviting all fathers of four- and five-year old children in their schools to participate in the project. While school attendance at that age is not mandatory, there is high attendance among the national population in public school kindergartens. Public schools are attended by 36% of the overall population of Abu Dhabi (SCAD, 2018; Gallagher, 2019). Eighty fathers of children aged 4–6 years participated and were given children’s books to take home to read with their children. Data were gathered during and after the workshops, and a wide survey of fathers’ engagement and wellbeing was also conducted which received 161 responses. The present paper focuses on linking actionable policy recommendations arising from the project with governmental vision and initiatives to develop literacy in the UAE. It is anticipated that these recommendations will have a positive impact on the experiences of parents, particularly fathers, in sharing reading with their young children.

There are two main components to the actionable recommendations. These encompass strategies for supporting paternal engagement in shared reading at home, and guidance on the selection and provision of culturally relevant picture books to share with young Emirati children and their parents. To ground these recommendations, a short review of home language and literacy practices among UAE nationals as well as literature pertaining to enhancing literacy through shared reading will be presented, followed by curated pertinent findings from the study.

Fathers, language, and literacy in the UAE

For many Emirati families, home reading is not a traditional practice (Barza and von Suchodoletz, 2016; Gregory et al., 2021), and a strong traditional oral culture remains a feature of contemporary Emirati society (Baker, 2018). The Emirati population speak a dialect of Gulf Arabic (known as “Khaleeji,” the variety of Arabic spoken across the Gulf states). Children learn Modern Standard Arabic for literacy and other formal purposes at school, and also learn English at school where it is both a subject and the language of teaching for some subjects (Gallagher and Dillon, 2023). A wide range of other languages are often heard at home, including the home languages of domestic helpers and spouses from overseas, both prevalent in Emirati households. Nevertheless, family language policy revolves around fostering children’s Arabic and developing Arabic-English bilingualism (Zhang et al., 2024). The national population, although socioeconomically the dominant class in the UAE, comprises only 13% of the overall resident population of the UAE (GLMM, 2024). For Emirati fathers in a society traditionally considered patriarchal, their family role has not traditionally encompassed direct involvement in their children’s educational development (Ridge et al., 2017). However, as the UAE continues on its rapid economic and social development trajectory, the role of fathers is evolving (Alteneiji, 2023), as evidenced for example by the introduction of paternity leave in 2020 (MOHRE, n.d.). This project responded to a call in 2022 by the Abu Dhabi Early Childhood Authority (ECA), indicative of a new interest in the role of fathers in the region, for proposals to investigate fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives in Abu Dhabi. In addition, ECA initiated a ‘Parent Friendly Workplace’1 award for workplaces that exceed local or global policies around parent-friendly practices, and which includes an emphasis on fathers’ involvement (Dickson et al., 2024), not just to improve children’s quality of life but also to enhance parental emotional, psychosocial, and physical well-being. Such initiatives are expected to contribute towards greater involvement of fathers going forward.

Enhancing literacy through shared reading

Given the scope and ambition of the UAE’s national development plans, as set out in the Abu Dhabi Economic Vision 2030 (Government of Abu Dhabi, 2007), education has assumed increased importance in the national agenda as the country embarks on the transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to a knowledge economy (Gallagher and Jones, 2023) and as it continues its aspirations to be a global player (Miller, 2016). High standards of reading comprehension are an essential component of the capacity-building required for such a transformation. Research internationally and in the region has connected higher levels of parental engagement with home reading with higher literacy levels (Al Ramamneh et al., 2023), emphasizing the importance of home reading practices for overall academic development. However, reading attainment in the UAE, according to the results of standardized international tests, is well below international norms for children attending state schools (Taha-Thomure, 2019).

Interactive shared reading, also referred to in the literature as dialogic reading (Dowdall et al., 2020), which involves the caregiver actively engaging the child in conversation about the story (Xu and Gao, 2021), draws upon Vygotskian theory which posits that child development occurs best through interaction with caregivers who pitch the interaction at a level that is appropriate for the child. In this project, parent–child home reading is construed as synonymous with interactive or dialogic shared reading wherein the adult and child engage together in reading as a meaning-making activity (Šilinskas et al., 2020). This typically involves recasts, expansions, and open-ended questions (Noble et al., 2020). Multiple benefits, including indirect benefits (McNally et al., 2023), are experienced by children from early home reading, including oral language development (Wang et al., 2023), conceptual development (Raban, 2022), vocabulary development (Shahbari-Kassem et al., 2024), comprehension skills (Al-Janaideh et al., 2022), positive dispositions towards reading (Zhang et al., 2024), and socioemotional development (Sun et al., 2023). For young children, picture story books provide the springboard for dialogue and for the development of familiarity with books in a pleasurable, informative way that can also promote parental wellbeing (Canfield et al., 2020).

Findings and discussion

Enjoyment of reading

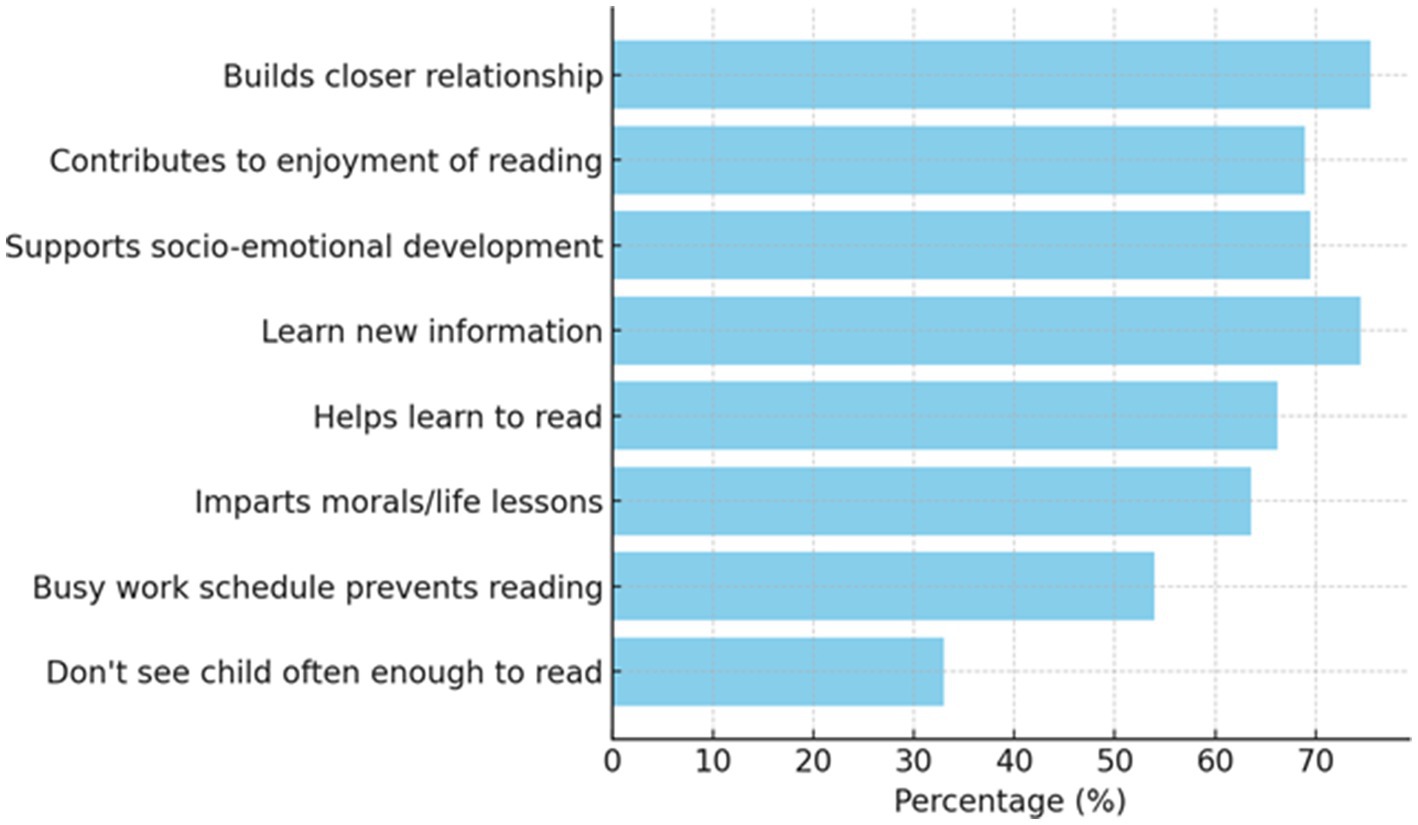

After participating in the workshops, fathers were provided with a selection of books to take home with them and were invited to provide feedback after reading them with their children by sending a voice note to the project phone on their experience. They were asked to mention aspects such as the books they read, the time and place of reading, and their own as well as their children’s reaction to the book, and feelings about the reading session. Fathers reported great enjoyment from reading with their children (Dillon et al., 2024) in their voice messages, even though interactive parent–child shared reading for pleasure was an experience that was new for most of them. Representative comments include “I enjoyed the book, and my son did too. It felt good to read with him,” and “It felt comfortable. I felt a connection with my child,” thereby highlighting a feeling of wellbeing. Indeed, the title of this paper, which includes the exclamation “Come home early and read with us!,” is a direct quotation from one of the participants as he relayed his child’s reaction to the novelty of reading with his father and illustrates how much the experience was enjoyed and looked forward to. The sense of enjoyment and closeness resulting from engaging in shared reading conveyed by fathers was confirmed by results from the survey, as seen in Figure 1 below, with most fathers (75.5%) agreeing that shared reading builds a closer relationship with their child. Results from the survey also show paternal recognition that parent–child reading contributes to children’s enjoyment of reading (68.9%), and that reading supports their children’s socio-emotional development (69.5%).

Preference for lingua-culturally relevant books and ways of reading

Workshop participants indicated that they preferred books which were culturally relevant to the UAE national culture and books which focused on the flora and fauna of the country’s natural desert environment. Regarding language use, as the UAE promotes bilingualism in Arabic and English, books were provided in these two languages. Fathers reported that they mostly read in Arabic, but some read in English, while others alternated between Arabic and English. A few fathers commented that they translated the book from standard Arabic into Emirati Arabic as they read to facilitate their child’s comprehension of the literary form. A small number of fathers noted that their children did not speak much Arabic due to having a foreign-born mother and were glad of the opportunity to develop their child’s Arabic. Some fathers mentioned that they preferred to discuss the books, rather than read them, perhaps due to limited confidence in their own reading skills. In contrast, others mentioned that they provided information or discussed ideas that were prompted by the books. In this traditionally oral culture, when fathers were asked in the project survey about the literacy activities they like to do with their children, the strongest association was found between fathers telling stories out loud and children asking to be read to (r(130) = 0.59, p < 0.001), indicating that the oral storytelling culture is easily connected to reading, and affirming that reading aloud with children need not be portrayed as an entirely new practice, but rather seen as an extension of oral storytelling. Survey participants also confirmed some education-related benefits, as seen in Figure 1 above, including that reading together is a way for their children to learn new information (74.5%), helps their child to learn to read (66.2%) and imparts morals or life lessons (63.6%).

Barriers to father-child shared reading

In terms of barriers to father-child reading, however, many fathers (54%) reported via the survey that a busy work schedule prevents them from having time to read, while one third of fathers mentioned that they do not see their child often enough to read with them. This was corroborated by field notes from workshops which reported some school principals’ observations that many fathers were often not involved in their children’s day-to-day lives due to divorce, which they said is increasingly prevalent. Challenges with finding appropriate spaces to read with their children were also frequently reported by the fathers who participated in the workshops. Some fathers also said they were unsure of what kind of books to read and when and where to read with their children at home, and others reported that there were not enough suitable books at home.

School-home partnerships for shared reading

School principals were critical to the success of the workshop element of the project, as they invited fathers on the research team’s behalf and provided facilities for the workshops. Field notes observed that principals were cognizant of the importance of early reading in both Arabic and English and expressed a wish to have more books available in their school libraries for families. A member of staff in one school, however, noted that her young child who attends a private school brings home books to read for pleasure with her parents every week, and remarked that this is not a common practice in public school kindergartens where there are few books in school libraries. And, although some principals mentioned the need for more direct engagement by fathers in their children’s education, other members of school staff indicated that they would have preferred to have only mothers attend the reading workshops, perhaps suggesting that fathers may not necessarily be fully welcome in some early years school settings.

Policy implications

To meet national aspirations for a successful transition from an oil economy to a knowledge economy, reading standards must improve, and this requires multiple efforts on multiple fronts, not just at school but across the educational ecosystem. A national literacy strategy, launched in 2015, aspires for half of Emirati parents to undertake to read to their children (UAE Government, n.d.). To realize this strategy in a context where home reading is not yet common, parents need support and guidance on why, how, and what to read with their children. Although there are multiple recent top-down, school-based initiatives to promote child reading in the UAE (for an overview, see Taha-Thomure, 2019), initiatives to promote parent–child reading at home are few so far, and are needed.

In line with recent research on parental engagement in the UAE which also emphasizes the importance of early home reading for future literacy and academic achievement (Hefnawi and Jeynes, 2022), one of the key findings of the present study is that modern Emirati fathers within a traditionally oral cultural setting are ready and willing to engage in shared reading at home. Not only are Emirati fathers ready and willing to read picture books with their children, but they also find it enjoyable and fulfilling. However, traditional gender roles may hinder sustained involvement, highlighting the need for policies like awareness campaigns and workshops to address these barriers. Most of the research on parent–child home reading is from more western societies, and this study strongly advocates for parent–child reading in this Middle Eastern context, thereby supporting other recent initiatives in similar contexts, such as the ‘Iqrali’/Read to me project in Jordan which aim to increase parental engagement in early literacy activities.

Secondly, to promote parental engagement with early literacy in this context, families need to be made aware of the diversity and quality of contemporary children’s literature in general, and in Arabic in particular, as the fathers who participated in this study were often not aware of the attractiveness, quality, and diversity of children’s books available nowadays. There has been huge growth across the Middle East in the publication of books in Arabic for young children (Taha-Thomure et al., 2020), and the quality of the 10 books that each father received certainly contributed in no small measure to the success of this project. Thus, guidance for families on the selection and provision of diverse, contemporary, culturally relevant picture books in both languages is also recommended as an educational policy. Guidance alone is not sufficient, however, and such books must be put directly into the hands of families and children through school and community libraries. Nationwide workshops should train educators, librarians, and community leaders on book selection and distribution, tailored to local contexts. Partnerships with publishers, authors, and digital platforms can ensure a steady supply of culturally relevant books. Effective distribution through community libraries, schools, and digital platforms is essential while monitoring through surveys will help assess the impact.

Moreover, while this study focused on fathers’ engagement in shared reading, workshops on shared reading should be provided for both fathers and mothers. Kindergartens and schools are appropriate settings for this, as an accessible and familiar setting for parents. To signal to fathers that they play an important role in their children’s educational development, one policy implication is to make fathers more overtly welcome in Kindergarten schools, to underline their important role in their children’s development. In addition, such workshops should emphasize to parents that literacy occurs along a continuum, and rather than being a new practice, and should portray interactive shared reading as occurring naturally within the context of oral storytelling and multilingualism.

Interestingly, and building upon a previous study which found that Emirati parents saw moral development and knowledge building as among the most important purposes for reading (Barza and von Suchodoletz, 2016), enjoyment of books, building a close relationship, and fostering socio-emotional development were found in this study to be valued also. The adoption of these recommendations has the potential to improve children’s literacy and academic outcomes over time. By increasing father involvement in home reading and strengthening school-home partnerships, establishing a culture that values early literacy will benefit educational outcomes for future generations.

Actionable recommendations

While this project involved fathers in the UAE, we believe that our findings and recommendations may be generalizable to other diverse contexts where home reading is not a common practice and where efforts are needed to expand the literacy ecosystem to include fathers. Actionable recommendations arising from the project to inform regional literacy programs and to bridge the gap between policy and practice are outlined in bullet format below.

• Take measures to increase fathers’ awareness of their importance in their young children’s literacy development, and of the mutual enjoyment and wellbeing engendered through engaging in interactive shared reading at home.

• Make fathers more openly welcome in preschools and Kindergartens, to signal that paternal engagement is both welcome and highly beneficial for their children’s educational development.

• Provide advice on time management and on allocating space for engaging in parent–child interactive shared reading at home

• Strive to engage with fathers as well as mothers through parental engagement programs.

• Build fathers’ and mothers’ familiarity and comfort with engaging in shared reading at home, through nationwide workshops on the why, what, and how of shared reading.

• Provide guidance on high-quality, culturally appropriate, contemporary children’s books in Arabic and English for families and schools.

• Provide access to such books for all families in the community through expanded school or community-based libraries.

Conclusion

The goal of this project was to encompass fathers within the emergent literacy development ecosystem in the UAE where early childhood education is in its infancy (Gallagher, 2020) and where recognition of the importance of early childhood is relatively recent (Dillon, 2019). Fathers who participated in this study enjoyed the experience and are willing to embrace a role in family literacy development by connecting with their children’s development through the enjoyment of sharing reading. This initiative aligns with the country’s National Literacy Strategy (UAE Government, n.d.) and the updated UAE Vision 2031 (UAE Government, 2023), which emphasize the development of a knowledge-based society and aim to improve literacy rates in line with international standards. In light of this, we recommend nationwide workshops on interactive parent–child shared reading for both mothers and fathers of young children, using the existing school network to host the workshops. Thus, guidance for families on the selection and provision of diverse, contemporary, culturally relevant picture books in both languages is recommended as an educational policy to support bilingualism and cultural identity. For this, we recommend making fathers more openly welcome in Kindergarten schools to emphasize their importance in their children’s development; providing guidance on culturally relevant, diverse books in both Arabic and English; and putting these books into the hands of families and children through school and community libraries.

Author contributions

KG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. CH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YA: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this project was provided by the Abu Dhabi Early Childhood Authority (ECA).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Al-Janaideh, R., Hipfner-Boucher, K., Cleave, P., and Chen, X. (2022). Contributions of code-based and oral language skills to Arabic and English reading comprehension in Arabic-English bilinguals in the elementary school years, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25, 2495–2510. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2021.1927974

Al Ramamneh, Y., Saqr, S., and Areepattamannil, S. (2023). Investigating the relationship between parental attitudes toward reading, early literacy activities, and reading literacy in Arabic among Emirati children. Large-scale Assessments in Education. 11. doi: 10.1186/s40536-023-00187-3

Alteneiji, E. (2023). Value changes in gender roles: perspectives from three generations of Emirati women. Cogent Soc. Sci. 9:2184899. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2023.2184899

Baker, F. (2018). Shaping pedagogical approaches to learning through play: a pathway to enriching culture and heritage in Abu Dhabi kindergartens. Early Child Dev. Care 188, 109–125. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1204833

Barza, L., and von Suchodoletz, A. (2016). Home literacy as cultural transmission: parent preferences for shared reading in the United Arab Emirates. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 11, 142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.08.002

Canfield, C. F., Miller, E. B., Shaw, D. S., Morris, P., Alonso, A., and Mendelsohn, A. L. (2020). Beyond language: impacts of shared reading on parenting stress and early parent–child relational health. Dev. Psychol. 56, 1305–1315. doi: 10.1037/dev0000940

Dickson, M., Midraj, J., McMinn, M., Sukkar, H., Alharthi, M., and Read, B. (2024). Fathers’ experiences of juggling work and family life in Abu Dhabi workplaces. Soc. Sci. 13:592. doi: 10.3390/socsci13110592

Dillon, A. (2019). “Innovation and transformation in early childhood education in the UAE” in Education in the United Arab Emirates. ed. K. Gallagher (Cham: Springer), 19–36.

Dillon, A., Gallagher, K., Saqr, S., Habak, C., and AlRamamneh, Y. (2024). The joy of reading – Emirati fathers’ insights into shared reading with young children in a multilingual context. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev., 1–14. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2024.2413149

Dowdall, N., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Murray, L., Gardner, F., Hartford, L., and Cooper, P. J. (2020). Shared picture book reading interventions for child language development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Dev. 91, e383–e399. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13225

Gallagher, K. (2019). Introduction: context and themes. In K. Gallagher (Ed.) Education in the UAE: Innovation and transformation, pp. 1–18. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978–981–13-7735-8

Gallagher, K. (2020). “Early childhood language education in the UAE” in International handbook of early language learning. ed. M. Schwartz (Cham: Springer), 893–921.

Gallagher, K., and Dillon, A. (2023). “Teacher education and EMI in the UAE and Arabian peninsula - past, present and future perspectives” in Plurilingual pedagogy in the Arabian peninsula: Transforming and empowering students and teachers. eds. D. Coelho and T. Steinhagen (London: Routledge).

Gallagher, K., and Jones, W. (2023). EMI in the Arab Gulf States: strategies needed to support the realization of governmental visions for 2030 and beyond. In M. Wyatt and G. GamalEl (Eds.). English as a medium of instruction on the Arabian peninsula. London: Routledge.

GLMM. (2024). Percentage of Nationals And Non-nationals in Gulf Populations 2020. Available at: https://www.grc.net/ (Accessed November 5, 2024)

Government of Abu Dhabi. (2007). Abu Dhabi Economic Vision 2030. Available at: https://www.actvet.gov.ae/en/media/lists/elibraryld/economic-vision-2030-full-versionen.pdf (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Gregory, L., Taha-Thomure, H., Kazem, A., Boni, A., Elsayed, M. A. A., and Taibah, N. (2021). Advancing Arabic language teaching and learning: A path to reducing learning poverty in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hefnawi, A, and Jeynes, W. (2022). Parental involvement in the UAE and in other moderate Arab states. In Relational aspects of Parental Involvement to Support Educational Outcomes: Parental Communication, Expectations, and Participation for Student Success. 1st ed. Ed. W. Jeynes Routledge. pp. 139–158.

McNally, S., Leech, K. A., Corriveau, K. H., and Daly, M. (2023). Indirect effects of early shared Reading and access to books on Reading vocabulary in middle childhood. Sci. Stud. Read. 28, 42–59. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2023.2220846

Miller, R. (2016). Desert kingdoms to global powers: The rise of the Arab gulf. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

MOHRE. (n.d.). UAE Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratization Paternity leave. Available at: https://www.mohre.gov.ae/en/paternity-leave.aspx (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Noble, C., Cameron-Faulkner, T., Jessop, A., Coates, A., Sawyer, H., Taylor-Ims, R., et al. (2020). The impact of interactive shared book Reading on Children's language skills: a randomized controlled trial. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63, 1878–1897. doi: 10.1044/2020_JSLHR-19-00288

Raban, B. (2022). Strong conceptual knowledge developed through home reading experiences prior to school. J. Early Child. Res. 20, 357–369. doi: 10.1177/1476718X221083413

Ridge, N., Jeon, S., and El Asad, S. (2017). The nature and impact of Arab father involvement in the United Arab Emirates. Sheikh Saud bin Saqr Al Qasimi Foundation for Policy Research, working paper, 13.

SCAD. (2018). Education Statistics https://scad.gov.ae/documents/d/guest/education-20statistics-202017-18-20-20en-pdf-1#:~:text=Government%20schools%20contain%2036.0%25%20of,of%20Abu%20Dhabi%20Emirate%20pupils.&text=of%20pupils.%20%E280A2%20Female%20pupils,male%20pupils%20in%20government%20schools.&text=education%2C%20while%2025.525%20were%20in%20the%20private%20schools (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Shahbari-Kassem, A., Asli-Badarneh, A., Hende, N., and Roby-Bayaa, A. (2024). Reading stories in Arabic: the impact of lexico-phonological and diglossic distance level on comprehension and receptive and productive vocabulary among Arab kindergarten children. Front. Educ. 9, –1394024. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1394024

Šilinskas, G., Sénéchal, M., Torppa, M., and Lerkkanen, M. (2020). Home literacy activities and Children’s Reading skills, independent Reading, and interest in literacy activities from kindergarten to grade 2. Front. Psychol. 11:508. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01508

Sun, H., Ng, S. C., and Peh, A. (2023). “Shared book Reading and Children’s social-emotional learning in Asian schools” in Positive psychology and positive education in Asia. eds. R. B. King, I. S. Caleon, and A. B. Bernardo (Cham: Springer).

Taha-Thomure, H. (2019). “Arabic language education in the UAE” in Education in the UAE: Innovation and transformation. ed. K. Gallagher (Singapore: Springer).

Taha-Thomure, H., Kreidieh, S., and Baroudi, S. (2020). Arabic children's literature: glitzy production, disciplinary content. Issues Educ. Res. 30, 323–344.

UAE Government (2023). ‘We the UAE 2031’ vision. Available at: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/ strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/innovation-and-future-shaping (Accessed January 30, 2025).

UAE Government. (n.d.). National Literacy Strategy. Available at: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/human-resources-development-and-education/national-literacy-strategy#:~:text=The%20National%20Literacy%20Strategy%20aims,to%20read%20to%20their%20children (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Wang, D., Su, M., and Zheng, Y. (2023). An empirical study on the reading response to picture books of children aged 5–6. Front. Psychol. 14:1099875. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1099875

Xu, Y., and Gao, J. (2021). A systematic review of parent-child Reading in early childhood (0–6): Effects, factors, and interventions. London: UCL Institute of Education.

Keywords: home reading, UAE, literacy development, father-child reading, interactive shared reading

Citation: Gallagher K, Dillon AM, Saqr S, Habak C and Alramamneh Y (2025) “Come back home early and read for us!” Enabling father-child shared reading in policy and practice. Front. Educ. 10:1529382. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1529382

Edited by:

Ana Sucena, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Rotem Schapira, Levinsky College of Education, IsraelDeborah Bergman Deitcher, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Copyright © 2025 Gallagher, Dillon, Saqr, Habak and Alramamneh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kay Gallagher, a2F5LmdhbGxhZ2hlckBlY2FlLmFjLmFl

Kay Gallagher

Kay Gallagher Anna Marie Dillon

Anna Marie Dillon Claudine Habak

Claudine Habak Yahia Alramamneh

Yahia Alramamneh