95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 20 February 2025

Sec. Mental Health and Wellbeing in Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1514895

Introduction: A healthy social–emotional functioning is vital for students’ general development and wellbeing. The school environment is a major determinant of social–emotional functioning, yet little is known about school-level and student-level characteristics related to healthy social–emotional functioning. In this study, we examined school-level characteristics (school size, school disadvantage score, urbanization level, and school denomination) and student-level characteristics (grade, secondary school track, participation in a COVID-19-related catch-up program, and measurement moment - during or after COVID-19) as predictors of students’ motivation for school, academic self-concept, social acceptance, and school wellbeing.

Methods: In school year 2020–2021, just after the first Covid-19 outbreak, 3,764 parents of primary school students from 242 Dutch primary schools and 2,545 secondary school students from 62 secondary schools filled out online questionnaires, before and after a Covid-19 related catch-up program was implemented at their school. Reliable and validated questionnaires were used to assess students’ motivation (Intrinsic Motivation Inventory), academic self-concept (Harter Self Perception Profile for Children; Self-Description Questionnaire-II), school wellbeing (Dutch School Questionnaire) and social acceptance (PRIMA Social Acceptance Questionnaire). School characteristics were derived from online databases. Student participation in a catch-up program and measurement moment (before or after the program) were taken into account. Data was analyzed via multilevel General Linear Mixed Models, separately for primary and secondary education.

Results: Of the school-level factors, only school disadvantage score was a significant predictor, specifically for primary school students’ motivation. Of the student-level characteristics, grade and catch-up participation were significant predictors of lower motivation, academic self-concept and school-wellbeing in primary school. In secondary school, students in higher grades had significantly lower motivation and school wellbeing; participants in catch-up program had a significantly lower academic self-concept; and perceived social-acceptance and school wellbeing were significantly lower just after COVID-19.

Conclusion: School-level characteristics only played a minor role in explaining differences in students’ social–emotional functioning. In both primary and secondary education, students in higher grades and participating in catch-up programs scored lower on their social–emotional functioning. Schools should be aware of students in higher grades being at risk for more problems in their social–emotional functioning.

COVID-19 has had a major impact on education. In many countries, schools were closed for extended periods of time and had to move to online and hybrid models of learning. This has had considerable implications for student learning, with high learning losses reported around the world (Betthäuser et al., 2023; König and Frey, 2022). Various studies have also documented how school closures resulted in poor social–emotional functioning of children and adolescents; young people were less motivated for school, felt less secure regarding their academic performance, had fewer positive peer relationships, had trouble sleeping, and were more likely to feel depressed and have mental health problems than in the period before COVID-19 (Deng et al., 2023; Harrison et al., 2022; Kauhanen et al., 2023; Ludwig-Walz et al., 2022; Mazrekaj and De Witte, 2024; Samji et al., 2022; Viner et al., 2022). These negative outcomes have also been reported for the Netherlands (Fischer et al., 2022; Luijten et al., 2021), with students’ social–emotional functioning continuing to lag behind that of their peers before COVID-19 (Orban et al., 2023; Van Oers et al., 2023).

These results are concerning given the importance of social–emotional functioning for positive behaviors in schools, the ability to assess risks, develop healthy relationships with others, and do well in school (Trentacosta and Fine, 2010). Low social–emotional functioning tends to be related to problematic behaviors, with higher rates of delinquency, aggression, and substance use (Moffitt et al., 2011; Trentacosta and Fine, 2010). Students with high social–emotional functioning generally do well later in life with more advanced careers, better health and other positive outcomes, such as marital status (Heckman et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2015; Moffitt et al., 2011). As youths spend a substantial amount of time in school, their experiences in the school context strongly affect their social–emotional functioning (Wells, 2000). Given the importance of the school-context for social–emotional functioning, in this study, we therefore examine the student-level and school-level characteristics that are related to social–emotional functioning of Dutch primary and secondary school students. Insight into relevant risk factors greatly facilitates early identification of students that are most at risk for adverse outcomes, helping in developing and implementing strategies or interventions to ameliorate social–emotional functioning of these risk at-risk populations.

Social–emotional functioning has not been defined clearly and studies tend to use different descriptions. A recent meta-analysis on the effectiveness of social–emotional intervention programs for example identified up to 136 frameworks comprising more than 700 different constructs related to social–emotional functioning (Cipriano et al., 2023), with the constructs that were considered important largely depending on the definition and framework used (Abrahams et al., 2019; Kyllonen, 2016). Here, we will follow the definition of social–emotional functioning provided by Weissberg et al. (2015), p. 6 as this framework is widely used in research in the school context and closely aligns with the goals of our project, referring to social–emotional functioning as: “the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that can enhance personal development, establish satisfying interpersonal relationships and productivity,” among others self-awareness, self-concept, empathy for others, responsible decision-making, recognition and management of emotions, and relationship skills. Others have labeled social–emotional functioning as “non-cognitive skills,” “psychosocial skills,” “interpersonal and intrapersonal skills,” or character skills” (see Duckworth and Yeager, 2015). Despite this multitude of terms, it has been stated that “all terms refer to the same conceptual space” (Duckworth and Yeager, 2015, p. 239), meaning that terms share characteristics regarding their relation to cognitive outcomes, dependence on contextual factors, and student benefits.

The large variety in the number of constructs and frameworks used also results in a large number of instruments that each measure different aspects of students’ social–emotional functioning (Primi et al., 2016; see Abrahams et al., 2019; McKown, 2019; Ng et al., 2022). There are many different measurement instruments available (aimed at measuring over 1800 outcomes), with limited reports on effectivity, reliability and validity, and often no clear descriptions of measurement purpose, operationalizing similar measures as different constructs, and vice versa (Cipriano et al., 2023).

As there are no clear guidelines on what social–emotional functioning entails, which aspects provide important indicators of students’ social–emotional functioning (and possible problems herein), and what measurement instruments provide valid and reliable ways for assessing social–emotional functioning, many schools have difficulties in monitoring their students’ social–emotional functioning. That is, they find it difficult to understand what the construct entails, and they do not know how to select adequate measurement instruments to monitor their students’ social–emotional functioning and possible problems herein. In the Netherlands, this was considered especially problematic during COVID-19 (Inspectorate of Education, 2021). Evidence of a relative decline in students’ cognitive skills emerged relatively quickly, as Dutch schools structurally and systematically monitor their students’ cognitive progress via standardized monitoring systems, allowing for comparison of results between schools and over time (Engzell et al., 2020). Such evidence was lacking for students’ social–emotional functioning, even though it was, and is, considered to be an important educational outcome as well. During the COVID-19 period, most schools relied on informal and unsystematic observations or non-standardized, readily available instruments when aiming to monitor students’ social–emotional functioning (Inspectorate of Education, 2021), making over-time and between-school comparisons extremely difficult.

Taking into account the large variety of constructs and measures, in our study, we will focus on four specific measures of social–emotional functioning: motivation for school, academic self-concept, social acceptance, and school wellbeing. These outcome measures were derived from the three main categories of the Framework for Social and Emotional Learning (Jones and Bouffard, 2012; Jones et al., 2019): (1) cognitive regulation (skills related to cognition and planning – i.e., motivation: the energizing of behavior for initiating, guiding and maintaining goal-directed behavior, (Simpson and Balsam, 2016); (2) emotional processes (skills associated with expressing and regulating emotions and “the self,” i.e., self-concept: the perception of competence in a certain domain (Wigfield and Eccles, 2000), here specifically focused on the academic domain); and 3) social/interpersonal skills (related to prosocial and cooperative behaviors and social relationships, i.e., social acceptance: the extent to which a child is liked by peers; Rabiner et al., 2016). A fourth outcome (school wellbeing) was added as a broader school-level, social–emotional factor, referring to well-being (i.e., personal happiness and life satisfaction; Pollard and Lee, 2003) in the school environment (Huebner and Gilman, 2006). This factor was previously found to be important for students’ social–emotional functioning and most strongly affected by social–emotional intervention programs (Cipriano et al., 2023).

Despite the lack of structured data on students’ social–emotional functioning, there was a widespread concern about overall wellbeing during and after COVID-19, which, in the Netherlands, resulted in a large government-funded program for school-based interventions. Schools could apply for funding to implement interventions that would address students’ learning losses and their social–emotional functioning. The programs were specifically aimed at vulnerable, at-risk students, who had suffered most from the COVID-19-related lockdowns. Schools were free to determine the type of program they implemented, the goals of the program and specific delivery and target group of students, as long as they could provide (narrative) evidence that the target group included students that were behind in their cognitive and/or social–emotional functioning. Many schools applied for the funding, with most Dutch primary schools (around 70%) and secondary schools (around 90%) applying for the funding. The specific goals of the programs and the activities used to reach these goals widely varied between schools. Many schools chose to implement programs that focused on students cognitive skills (mainly performance in the core subjects: mathematics and language), but almost half of the schools also included interventions to enhance students’ well being and social–emotional functioning (De Bruijn and Meeter, 2023; De Bruijn et al., 2021; Kortekaas-Rijlaarsdam et al., 2020). Activities included were most often focused on extension of school hours, tutoring, remedial teaching, provision of extra materials, or summer schools. More information on the program choices schools made can be found in our previous publications (De Bruijn et al., 2021; Kortekaas-Rijlaarsdam et al., 2020).

International research has documented positive effects of intervention programs on students’ social–emotional functioning, with a recent meta-analysis reporting a moderate to large overall effect size of 0.194 (ranging from 0.122 to 0.293 depending on the outcome measure used, e.g., school climate, prosocial behaviors, externalizing behaviors); effects that seem to last over time (Cipriano et al., 2023). Also, intervention programs are considered cost-effective and feasible to implement in practice (Domitrovich et al., 2017; Kraft, 2020).

Yet, although overall positive effects of social–emotional intervention programs have been reported, there is large variability in their effects. It is yet unclear what type of program is most effective, and which mechanisms are responsible for these differential effects – in large part because studies are inconsistent in the outcomes and features of intervention programs they examined. A moderator analysis (Durlak et al., 2022) shows inclusive results regarding program, school, and student characteristics that explain the effects of social–emotional intervention programs (Durlak et al., 2022). One factor that seems to consistently relate to the effectiveness of social–emotional intervention programs is program implementation: how a program is being delivered in practice (Durlak, 2015, 2016). Implementation features entail components such as program structure, fidelity, dosage, and extent to which a program was implemented as intended (e.g., Durlak, 2015; Durlak, 2016; Low et al., 2016). Intervention programs with a higher implementation quality are generally found to be more effective (Durlak, 2015; Low et al., 2016).

Importantly, in targeting students’ social–emotional functioning, it seems important to take differences in school characteristics into account, given the important role that schools play in students’ development (Paulus et al., 2016). Unfortunately, knowledge regarding school-level characteristics that relate to students’ social–emotional functioning is limited, as not many large-scale studies have structurally investigated such relations between and within schools (Patalay et al., 2020). Most studies have examined school-level characteristics in relation to mental health problems, particularly in secondary education. Previous research has shown that mental health difficulties in the school population are associated with a range of social–emotional skills, including motivation (e.g., Doll and Lyon, 1998; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012), self-regulation (e.g., Gross and Muñoz, 1995; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012), empathy (e.g., Green et al., 2005), self-awareness (Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012; Posse et al., 2002), and social skills (e.g., Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012; Rae-Grant et al., 1989; also see Denham et al., 2009; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012). Yet, although low social–emotional functioning is seen as predictive for the onset of mental health problems (Thomson et al., 2019; Weare and Markham, 2005), more research is needed to understand whether similar factors are of importance when examining social–emotional functioning.

Previous studies focusing on mental health outcomes have indicated that especially school deprivation score is an important predictor of behavioral problems and mental health difficulties among students (Ford et al., 2021; Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012; Kellam et al., 1998; Patalay et al., 2020; Saab and Klinger, 2010). In addition, school climate has consistently been found to be a determining factor for students’ mental health, where a positive educational environment in which students and teachers feel safe, both physically and socially, relates to better mental health (e.g., Ford et al., 2021; Patalay et al., 2020; Steinmayr et al., 2022). Evidence on other school-related factors, such as school size, urbanicity, gender balance, or staff-student ratio, has been inconclusive (Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Ford et al., 2021; Rathmann et al., 2020; Saab and Klinger, 2010; Sellström and Bremberg, 2006; Vaz et al., 2014).

Additionally, most studies have focused on how school-level factors relate to secondary school students’ mental health (Kellam et al., 1998; Patalay et al., 2020; Saab and Klinger, 2010; Vaz et al., 2014), whereas social–emotional development already starts from a young age onwards, making it important to identify factors related to social–emotional functioning already at a younger age – as early intervention may prevent later problems. One of the few studies conducted in the primary school setting indicated that more than 11% of the variation in students’ social–emotional functioning could be attributed to school-level variables (i.e., proportion of students with special needs, average level of academic achievement; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012), suggesting that contextual factors may be of even greater importance in the earlier years of education. A closer examination of school-level factors related to social–emotional functioning in primary and secondary school thus seems vital for determining upon effective interventions for strengthening students’ social–emotional functioning.

In determining school-level characteristics to include in this study, we follow the framework of Ford et al. (2021) in which three groups of school-level factors are distinguished: (1) The broader school context, representing structural socioeconomic factors of the school surroundings, such as urbanicity or area-level deprivation; (2) School community, characteristics of the school population, such as average socioeconomic status, number of students with special educational needs, and ethnic composition; (3) Operational factors, referring to structural school characteristics, for example school size, pupil-to-teacher ratio, and school climate. Following this framework and meta-analytic results on school-level factors related to effects of social–emotional intervention programs (Cipriano et al., 2023) we will include the following school-level characteristics: urbanization level (level 1: the broader school context), school disadvantage score and denomination (level 2: school community), and school size (level 3: operational factors).

Similar to school level characteristics, there is limited literature exploring individual student-level factors predictive of students’ social–emotional functioning, and there is limited knowledge of individual differences in students’ social–emotional experiences, with little attention for developmental differences, diverse backgrounds, and the contexts surrounding children (Hamilton and Gross, 2021). This was especially problematic during the Covid-19 pandemic, as many students faced social–emotional difficulties due to the Covid-19 outbreak, and schools and teachers were struggling with addressing these difficulties among their students.

Research on individual differences in students’ mental health indicates that individual-level characteristics seem to be even more strongly linked to students’ mental health than contextual school-level factors. That is, only around 1 to 3 percent of the variance in student social–emotional outcomes are accounted for by school-level characteristics (e.g., Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Hinze et al., 2023; Kidger et al., 2012; Rathmann et al., 2020; Saab and Klinger, 2010; Sellström and Bremberg, 2006). For example, students’ age seems to be of importance, with various studies indicating that older students experience more mental distress and problems than their younger peers – particularly when entering adolescence (Green et al., 2005; Hinze et al., 2023; Jones, 2013; Rathmann et al., 2020; Yoon et al., 2023).

When considering experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, the period during which our research was conducted, a specific factor of interest to consider is students’ at-risk status. At risk students are students who are at risk for dropping out of education before graduating, because of cognitive or social–emotional difficulties, or a disadvantaged background (Watson and Gemin, 2008). Schools were most likely to select these students for on-site education during the COVID-19 lockdowns, because of them being at risk for poorer cognitive and mental health outcomes. As such, these students were more likely to report depressive or anxious feelings or deteriorations in their wellbeing because of their vulnerability (Mansfield et al., 2021). Again, it should be noted that previous studies mainly focused on predictors of students’ mental health (problems), instead of examining aspects of more general social–emotional functioning. In order to fully understand relations of individual-level characteristics with social–emotional functioning, more research is needed.

Given the known importance of students’ social–emotional functioning, and the lack of knowledge regarding predicting factors hereof, this study examines the student- and school-level characteristics that are related to social–emotional functioning of Dutch primary and secondary school students. Specifically, we looked at school-level characteristics (school size, school disadvantage score, urbanization level, and school denomination) and student-level characteristics (grade, track - for secondary school students, participation in a COVID-19-related catch-up program, and measurement moment - during or after COVID-19) predictive of motivation for school, academic self-concept, social acceptance, and school wellbeing.

Taking these characteristics and outcome measures, we aimed to answer the following research questions:

To what extent do students’ grade, participation in a catch-up program, measurement moment, and – specifically for secondary school – track relate to students’ academic motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social-acceptance?

To what extent do school size, school disadvantage score, urbanization level, and school denomination relate to students’ academic motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social-acceptance?

The first research question focuses on predictive student-level characteristics, the second on predictive school-level characteristics. By answering these questions, we aimed to disentangle how the school environment relates to student’s social–emotional functioning, and whether this differs depending on characteristics of individual students. Our results provide insights into students’ social–emotional functioning, and the role of school- and student-level characteristics herein. Given the importance of students’ healthy social–emotional functioning, these findings are of vital importance for schools to identify students at risk for negative impacts of schooling experiences (Mansfield et al., 2021). In addition, our results may support schools in understanding how their context affects students’ social–emotional functioning and how they can create a more conducive environment.

An overview of our research design is presented in Figure 1. Our study is part of a wider evaluation study of the government’s funding program of school-based catch-up programs. Students completed questionnaires at the start of the program at their school and once after the program had finished. For primary school students, parents were asked to fill out the questionnaire on behalf of their child, because children of this age have limited cognitive capacities in understanding questions and reflecting upon their social–emotional functioning.

Figure 1. Visual representation of our research design, including school-level and student-level factors and social–emotional outcome measures.

Note that although we include both program participation (comparing catch-up program participants and non-participants) and measurement moment (pretest, posttest) in our analyses, we do not examine program effectiveness. For all participants, we only included data at one measurement point. We mainly include these factors to control for possible differences between participants and non-participants and measurement moments. Although examination of program effectiveness was our initial aim, too few participants answering the questionnaires at both measurement points to make such an analysis feasible.

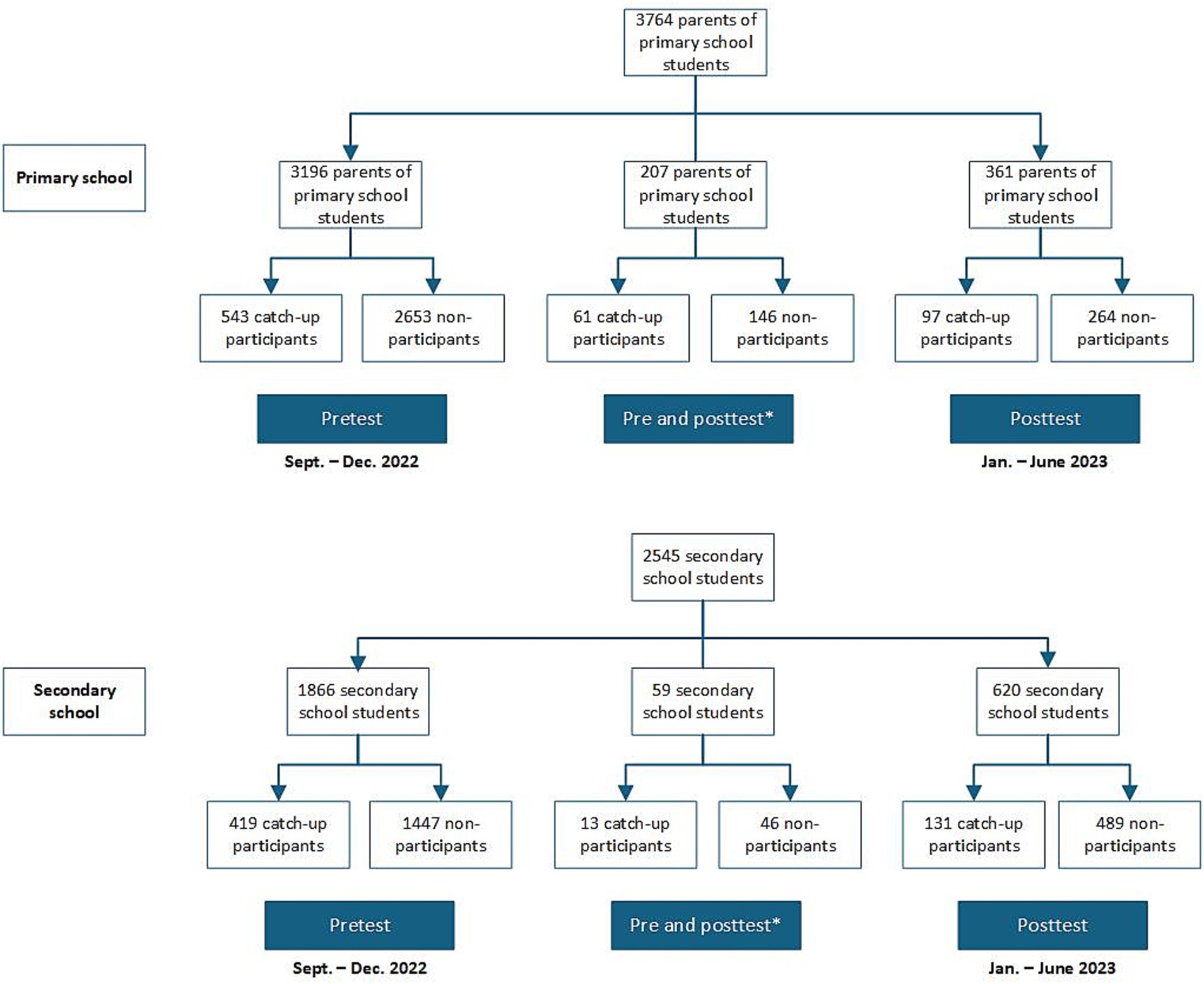

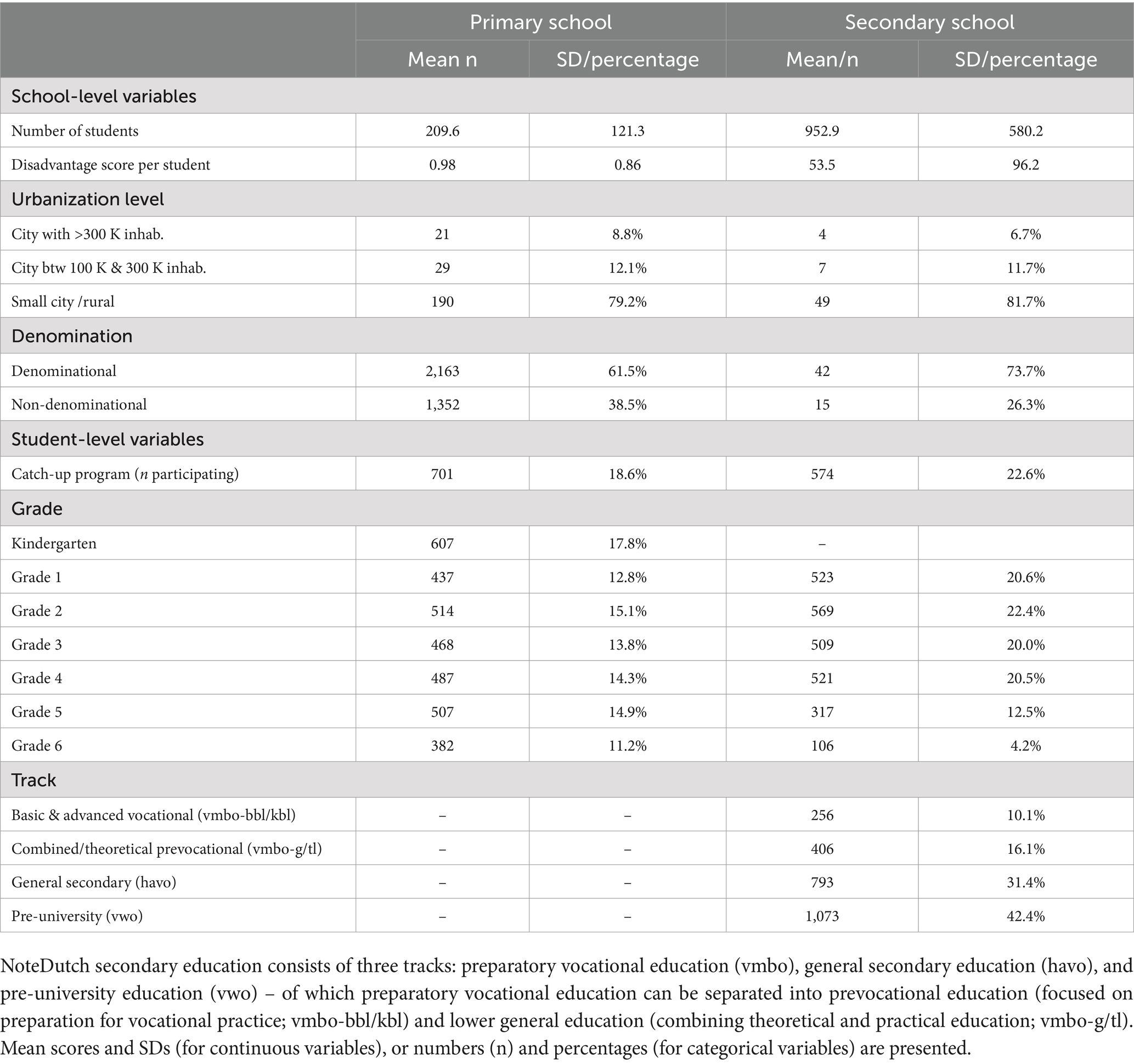

Students and their parents could participate if they attended a school where a catch-up program was implemented. Students from specialist schools were excluded. Table 1 presents an overview of the number of participants, indicating the number of parents and secondary school students that filled out the questionnaire before and after the program, and the number of students that participated in a catch-up program. A flowchart presenting the number of participants in each condition is presented in Figure 2. In total, 3,764 parents of primary school students from 242 Dutch primary schools filled out the questionnaire, either before the program (3196), after the program (361) or at both time intervals (207). In addition, 2,545 secondary school students from 62 different schools filled out the questionnaire, either before the start of the program (1866), after program completion (620) or at both time intervals (59). Table 2 summarizes the background characteristics of participating students and their schools.

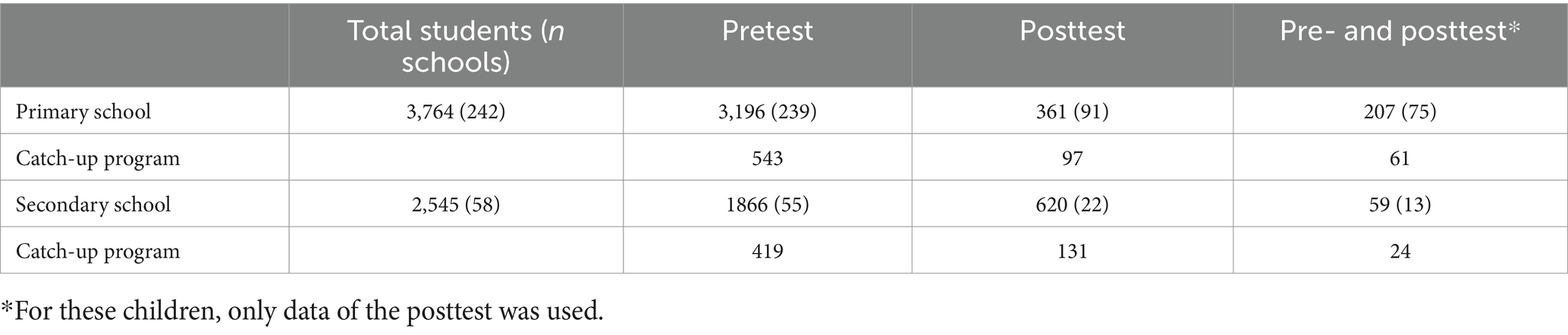

Table 1. Number of participating children and schools, at pretest, posttest, and both, for the total sample of primary and secondary school students, and for catch-up program participants.

Figure 2. Overview of primary school and secondary school participants, at pretest and posttest, and number of students following a catch-up program.*For analyses, only posttest data of these participants was used.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics on school level and child level variables, separated for primary and secondary school students.

Parents and participation students provided consent before filling out the questionnaires at both timepoints. Participation was anonymous and participants could withdraw from the study at any moment. The study was approved by the ethical board of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (primary education: VCWE-2019-151; secondary education: VCWE-2020-190).

Motivation for school was measured with the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI; Ryan and Deci, 2000). The IMI is a reliable (α = 0.85) questionnaire that is commonly used as a measure of motivation (McAuley et al., 1989). An abbreviated Dutch version of the IMI was used, which has been validated with primary school students (Vos et al., 2011). This abbreviated version contains 14 questions measuring three components of motivation for school: perceived competence, interest, and effort. Items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all true” to “True.” Example items are “I am pretty skilled at school” and “I think school is boring.” Internal consistency of the Dutch translation of the IMI is considered to be good (α = 0.78; Vos et al., 2011). Internal consistency of the IMI in this study was good for both primary school (α = 0.88) and secondary school (α = 0.89).

In order to take into account age differences between primary school and secondary school students, different measures of academic self-concept were used for primary and secondary school students. Parents of primary school students filled out the subscale school skills of the Competency Experience Scale for Children (CBSK; Veerman et al., 2004). The CBSK is a Dutch translation of the Harter Self Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1985) developed for Dutch 8-to-12 year old children. The subscale school skills consists of six questions in which parents were asked to indicate how much their child thinks he or she is like other children on several aspects of academic functioning. An example item is “Some children think they are good learners” with answer options on a four point Likert scale ranging from “I am not like these children” to “I am exactly like these children.” The school skills subscale is considered a reliable (test–retest reliability α = 0.86) and valid measure of children’s academic self-concept (Veerman et al., 2004). Internal consistency of the CBSK school skills subscale in this study was good (α = 0.78).

Secondary school students filled out the Dutch translation of the Self-Description Questionnaire-II (SDQ-II; Marsh, 1990; translated by Simons and Simons, 2001). The SDQ-II asks students about their own perception of their skills and performance in Mathematics, Dutch and for school in general. Items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all true” to “true.” An example item is “I do well in tests in most school subjects.” The Dutch translation of the three SDQ-II subscales is a reliable (test–retest reliability ranging from.77 to.92 in Flemish secondary school students; Denies et al., 2017) measure of academic self-concept. The scale is widely used to measure academic self-concept (Gilman et al., 1999) and validity of both the original (supported by confirmatory factor analyses; Gilman et al., 1999) and translated (Van Bael, 2013) version of the scale has been proven. Internal consistency of the SDQ in this study was good (α = 0.85).

School wellbeing was measured with the School Wellbeing Scale from the Dutch School Questionnaire, a commonly used questionnaire in Dutch primary schoolss (Schoolvragenlijst; SVL; Smits and Vorst, 2008). The School Wellbeing Scale consists of 9 questions measuring the extent to which students appreciate and are satisfied with daily life at school. An example item is “I am happy to go to this school,” which can be answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all true” to “true.” The SVL is a reliable measure of school wellbeing (internal consistency α > 0.80; Smits and Vorst, 2008), for which validity has been provided by the Dutch Committee on Tests and Testing (based on a study among 10.000 students; Egberink and Leng, 2024). Internal consistency of the SVL in this study was good for both primary school (α = 0.87) and secondary school (α = 0.88).

Social acceptance was measured using the Social Acceptance Questionnaire from the PRIMA-study (Driessen et al., 2000; Vandenberghe et al., 2011), consisting of 6 questions measuring the social relations of students with their classmates. Items have to be answered on a five point Likert scale ranging from “not at all true” to “true.” An example item is “I get along well with most children in my class.” The Social Acceptance Questionnaire is a reliable measure of students’ social acceptance (α = 0.82; Vandenberghe et al., 2011; 0.79 ≤ α ≥ 0.84; Van den Branden et al., 2015). Validity of the questionnaire has been proven (convergent factor analysis; Driessen et al., 2002; see Denies et al., 2017). Internal consistency of the Social Acceptance Questionnaire in this study was good for both primary school (α = 0.85) and secondary school (α = 0.83).

School characteristics were obtained from the Dutch national database of Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs (DUO); a government agency responsible for keeping records of student and school data and in charge of distributing funding to schools. DUO collects data annually on characteristics of all primary, secondary and higher education institutions in the Netherlands. For this study, the most recent database (October 2021) was used to derive data on the number of students, urbanization level, and denomination. School location was used to determine the urbanization level, which was categorized into: (1) city with >300.000 inhabitants (the four biggest cities in the Netherlands: Amsterdam, Den Haag, Rotterdam, Utrecht); (2) other cities with between 100.000 and 300.000 inhabitants (the 18 biggest cities in the Netherlands, except the four biggest); or (3) small city/rural, representing all smaller cities or villages. Schools were also categorized on the basis of their denomination. Non-denominational schools provide education on behalf of the state and can be attended by all children, irrespective of their religion. Denominational schools have a specific belief, religion, or ideology (e.g., Catholic, Protestant or Muslim), and schools can refuse students if their parents are not adhering to these religious or ideological beliefs. Non-denominational schools are not founded or governed by the state, but by an association (e.g., a church), yet are funded by the government in a similar manner as non-denominational schools. Both denominational and non-denominational schools can decide what and in which way they teach, and may have specific educational ideologies, for example Jenaplan or Montessori.

Finally, we included the average disadvantaged score of a school as indicated in the database of Statistics Netherlands (CBS). To counter educational disadvantage, schools in the Netherlands receive extra funding derived from the number of disadvantaged students registered at their school. Per student, disadvantage scores are determined by parents’ country of origin, educational level, debt repayment, and mother’s residency period. The extra funding a school receives is determined by aggregating disadvantage scores of their student population. In this study, the average disadvantage score per student was used, calculated by dividing the sum of individual disadvantage scores by the number of students.

Data was collected in the school year 2020–2021. Primary and secondary schools that had applied for funding of a catch-up program were required to participate in this study, and were asked to invite parents via an email sent through the school portal. Participants were asked to fill out the questionnaire within 3 days after receiving the invitation. The second questionnaire was sent after the catch-up program at the school was finished, using the same procedure. Filling out the questionnaires took approximately 25 min. To link questionnaires at both timepoints, participants were asked to fill out two questions in both questionnaires by which a personalized code could be constructed that we could use to link their answers.

Several demographic questions were included, about the student’s school, grade, and, for secondary school students, track. In addition, participants were asked to indicate whether they participated in a catch-up program, and if so, what the goal of this program was, what type of activities were done, and how often the program was provided. After these demographic questions, which were used to determine student-level characteristics, participants filled out the four questionnaires described above (motivation, academic self-concept, school wellbeing and social acceptance). At the end of the questionnaire, participants were provided with contact details of the research team, so they could get in touch in case they had any questions or concerns.

The CBS and DUO databases containing school characteristics are publicly available from the respective websites. The version for the year of data collection (i.e., 2021) was downloaded and used.

Our sample included too few participants who filled out the questionnaire at both time points for a viable within-participant analysis. We therefore analyzed between-participant differences and included data of all participants, independent of whether they participated at pretest or at posttest. For participants who filled out the questionnaire at both time points, we included only the posttest data. To account for the different measurement time points, a variable indicating measurement time (i.e., pretest or posttest) was constructed and included in the analysis models. Participation in a catch-up program was coded as ‘yes’ if parents or students indicated that they participated in such a program at one or both of the timepoints.

Data cleaning and analysis was conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27 for Windows. School-level variables (i.e., number of students, urbanization level, denomination, disadvantage score) were linked to data of individual students via a BRIN-number: a code that is assigned to each educational institute in the Netherlands. BRIN-numbers are available at both the level of the individual school (BRIN-6) as well as the level of school associations (BRIN-4). As school characteristics differ for individual schools, we included data at the individual school level. BRIN-6 numbers were assigned to data of individual participants based on the school names provided in the questionnaires. Unfortunately, not for all participants’ BRIN-6 numbers could be determined as some school names are used by multiple schools, and school associations sometimes use the same name for individual schools. Participants for whom a BRIN number could not be established were excluded from further analysis.

Assumptions of normality, linearity, and independence of errors were checked using Q-Q plots, Shapiro–Wilk tests of normality, scatterplots and P–P plots. Next, multilevel General Linear Mixed Models with Restricted Maximum Likelihood estimation were constructed to analyze whether school characteristics were predictive of student social–emotional functioning. This analysis was done separately on primary school and secondary school data. Separate models were constructed for the four outcome measures (motivation, academic self-concept, school wellbeing, and social acceptance). In these models, school characteristics (number of students, disadvantage score, urbanization level, denomination) and student characteristics (grade, catch-up program participation, measurement moment, and for secondary school students: track) were entered as fixed factors. Random intercepts and slopes were added at school level using variance components as covariance type, to control for nesting within schools. To correct for correlations between the multiple outcome measures, the significance level was set at α = 0.0125 (i.e., taking the conventional α = 0.05 divided by the number of outcome measures examined). Satterthwaite adjustment was used in all models, to calculate an approximation of the effective degrees of freedom (i.e., pooled degrees of freedom) for a probability distribution comprised of several independent normal distributions with unknown variance (Satterthwaite, 1941, 1946).

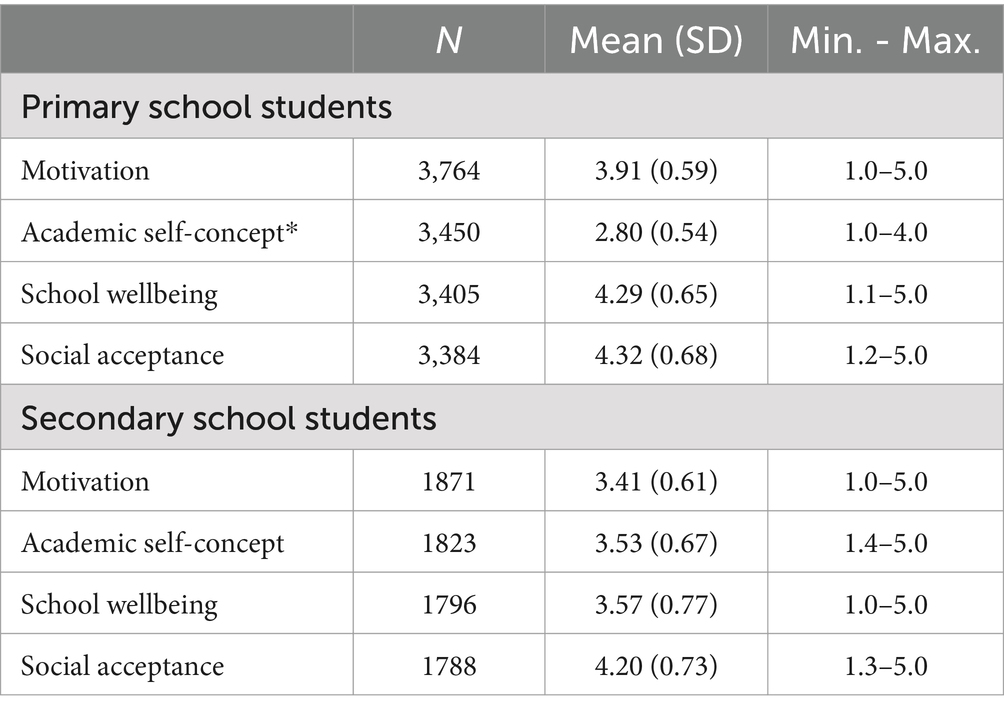

Mean scores on motivation, academic self-concept, school wellbeing and social acceptance, associated standard deviations and minimum/maximum values are presented in Table 3, separately for primary school and secondary school students. Correlations are presented in Appendix A and the full measurement models are presented in Appendix B. The following section presents the model results, separately for primary and secondary school students.

Table 3. Mean (standard deviations) and minimum – maximum scores on the outcome measures motivation, academic self-concept, school wellbeing and academic self-concept for primary school and secondary school students.

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 6.6% variance; with an approximate total of 7.2% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

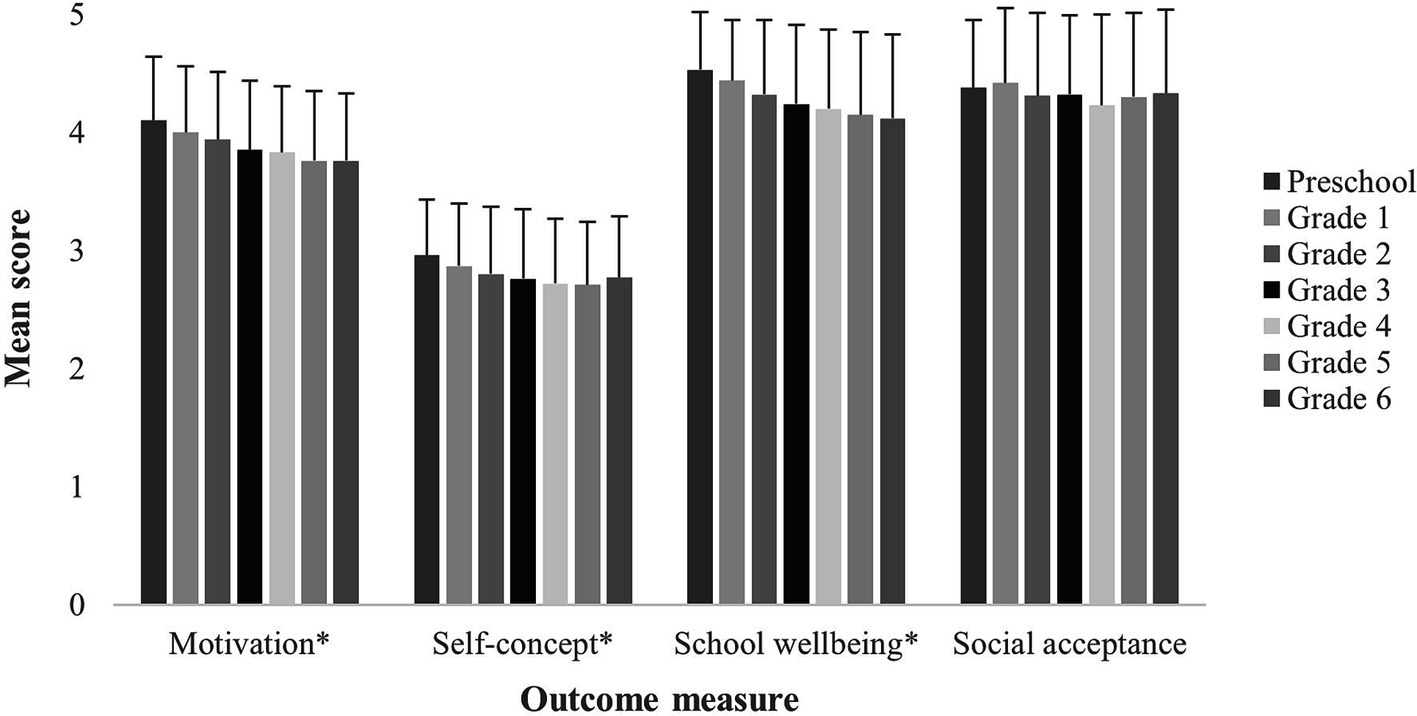

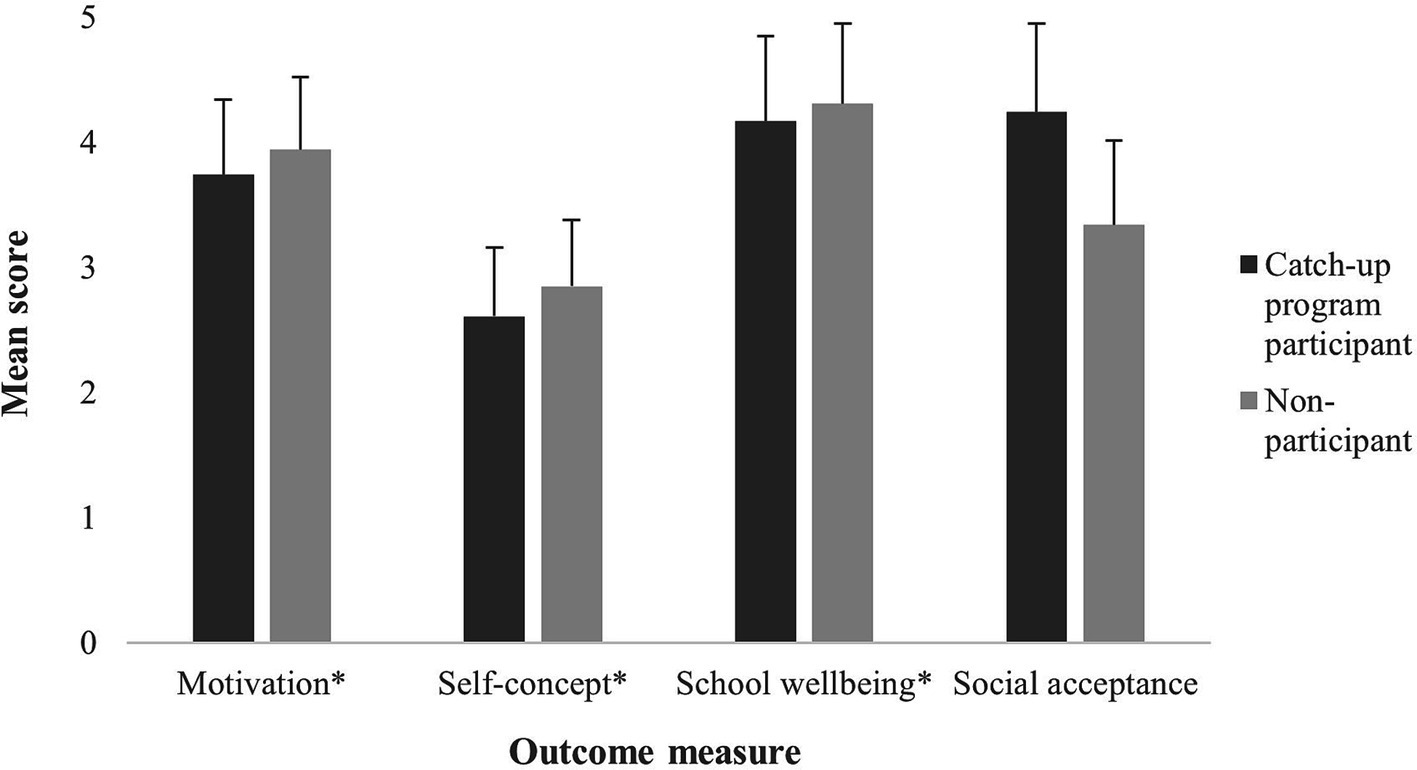

Effects on motivation were found for disadvantage score [β = 0.05, SE = 0.01, F (1, 204.59) = 11.68, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.02,0.08], grade [β = −0.06, SE = 0.01, F (1, 3123.32) = 146.82, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.07, −0.05], and participation in a catch-up program [β = −0.17, SE = 0.03, F (1, 2986.12) = 39.13, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.22, −0.11]. Students at schools with a higher disadvantage score generally had a higher motivation for school than students at schools with lower disadvantage scores. Students in higher grades were less motivated for school than their peers in lower grades (see Figure 3), and students who participated in a catch-up program scored lower on motivation than their non-participating peers (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Primary school students’ scores on motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social acceptance separated by grade. * indicates significant differences between the grades. Error bars present standard errors.

Figure 4. Primary school students’ scores on motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social acceptance, separated for children’s participation in a catch-up program (yes/no). * indicates significant differences between the two groups. Error bars present standard errors.

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 4.0% variance; with an approximate total of 4.7% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

A main effect of grade was found [β = −0.03, SE = 0.01, F (1, 2874.71) = 38.53, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.04, −0.02], with students in higher grades in general having a lower self-concept compared to students in lower grades (see Figure 2). In addition, participation in a catch-up program was a predictor of academic self-concept [β = −0.21, SE = 0.03, F (1, 2746.79) = 66.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.26, −0.16], indicating that students who participated in a catch-up program scored lower on self-concept than their peers who did not participate in a catch-up program (see Figure 3).

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 5.2% variance; with an approximate total of 7.5% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

Main effects of grade [β = −0.07, SE = 0.01, F (1, 2830.93) = 127.00, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.08, −0.06] and participation in a catch-up program [β = −0.09, SE = 0.03, F (1, 2769.65) = 8.43, p = 0.004, 95% CI = −0.15, −0.03] were found. Students in higher grades had a lower school wellbeing than their peers in lower grades (see Figure 3), and students who participated in a catch-up program scored lower on school wellbeing than their non-participating peers (see Figure 4).

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately.6% variance; with an approximate total of 2.9% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

We did not find significant main effects (all p > 0.0125).

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 6.8% variance; with an approximate total of 9.4% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

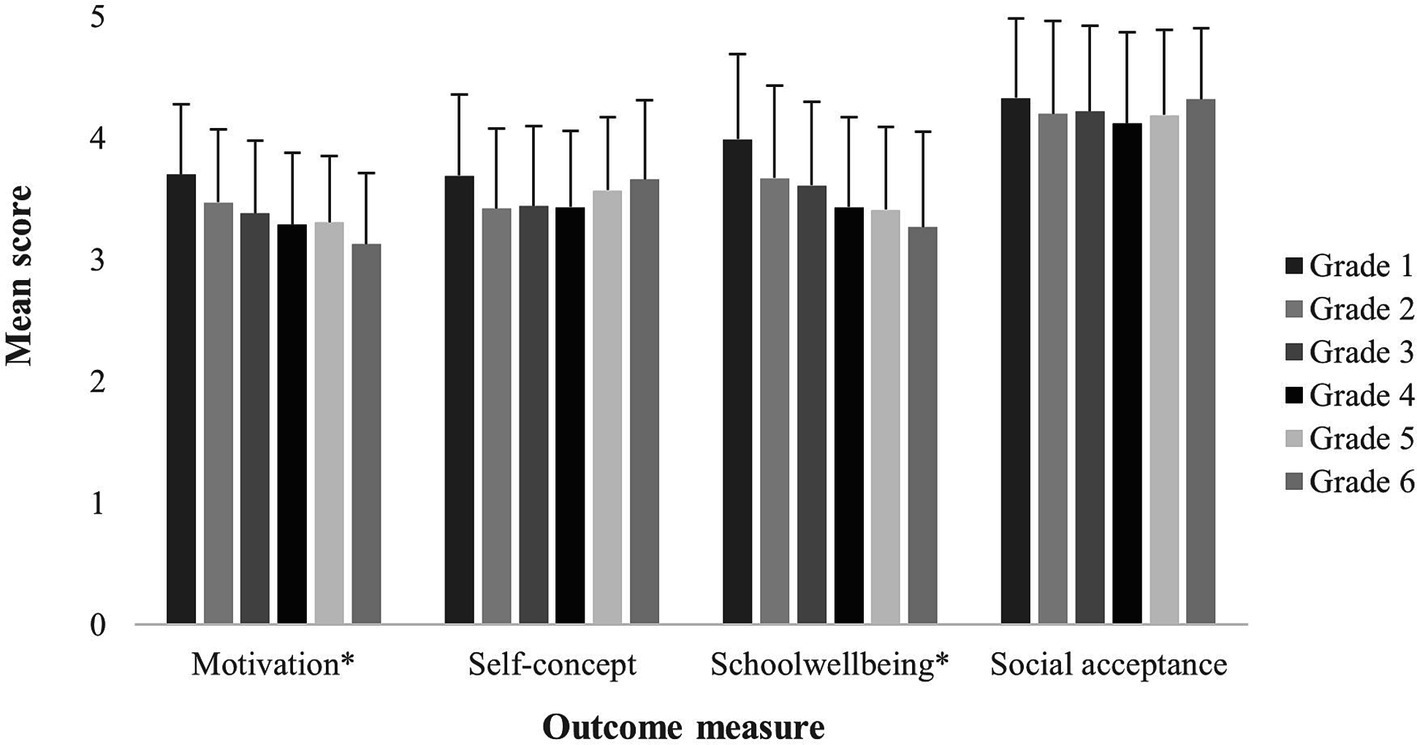

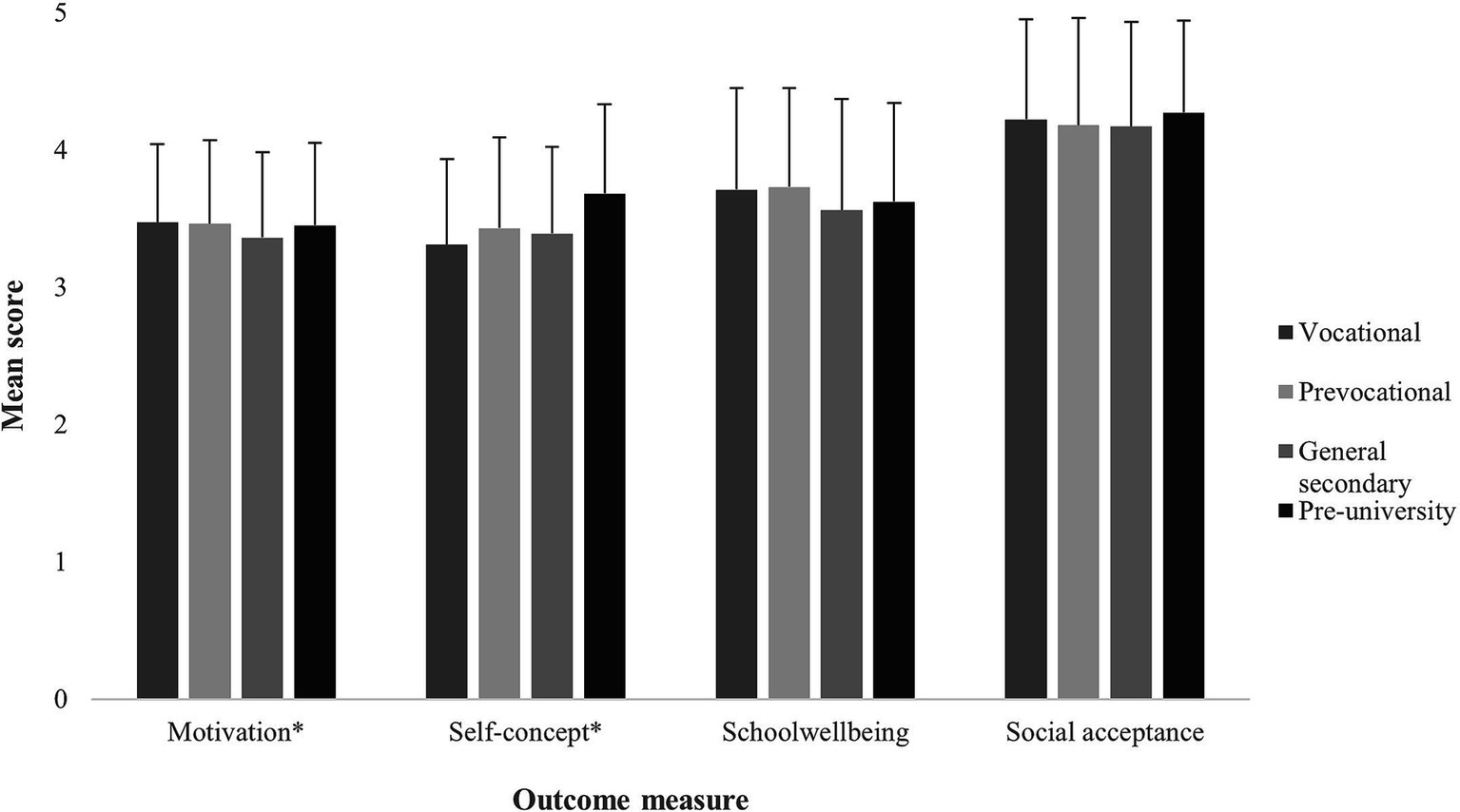

A main effect of grade was found [β = −0.10, SE = 0.01, F (1, 1628.37) = 83.30, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.12, −0.08], indicating that students in higher grades had a lower motivation for school than their peers in lower grades (see Figure 5). Also, ‘track’ predicted students’ motivation [F (3, 1207.91) = 3.66, p = 0.012], with students in the general secondary track being less motivated than their peers in the pre-university track [β = −0.11, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.17, −0.04; see Figure 6].

Figure 5. Secondary school students’ scores on motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social acceptance separated by grade. * indicates significant differences between the grades. Error bars present standard errors.

Figure 6. Secondary school students’ scores on motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social acceptance separated by track. * indicates significant differences between the tracks. Error bars present standard errors.

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 7.8% variance; with an approximate total of 10.6% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

A main effect of track was found [F (3, 1197.41) = 19.44, p < 0.001] with students in the vocational [β = −0.33, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.46, −0.20], prevocational [β = −0.25, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.36, −0.15], and general secondary track [β = −0.26, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.33, −0.18] having a lower self-concept compared to their peers in the pre-university track (see Figure 6). In addition, an effect of participation in a catch-up program [β = −0.29, SE = 0.04, F (1, 1604.47) = 60.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.36, −0.22] was found, indicating that students who participated in a catch-up program generally had a lower self-concept than their non-participating peers.

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 7.6% variance; with an approximate total of 14.0% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

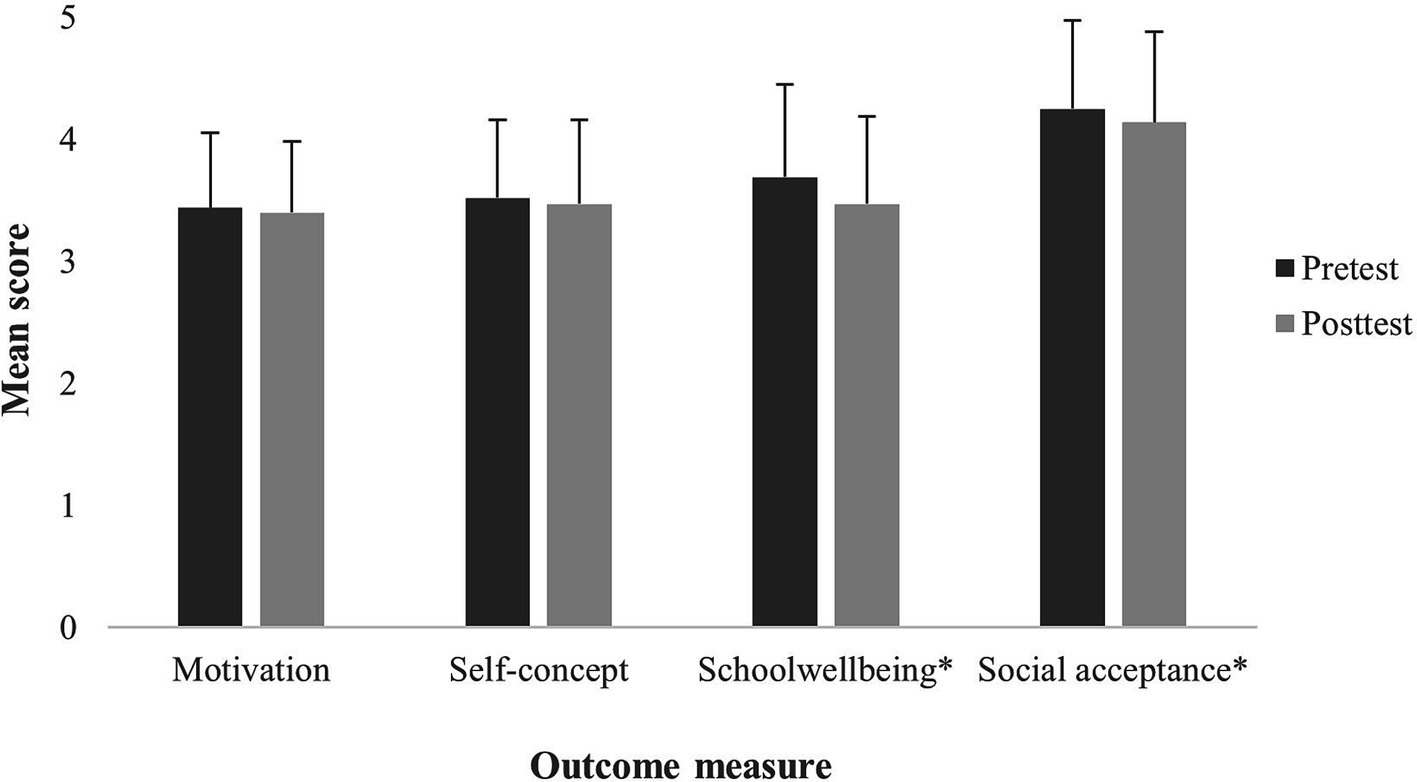

A main effect of grade [β = −0.13, SE = 0.01, F (1, 1702.05) = 101.80, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.15, −0.10] was found, with students in higher grades having a lower school wellbeing than their peers in lower grades (see Figure 5). Also, measurement moment was predictive of school wellbeing [β = 0.16, SE = 0.06, F (1, 511.00) = 7.38, p = 0.007, 95% CI =0.04, 0.28] with students scoring higher on school wellbeing at pretest compared to posttest (see Figure 7). This effect was not caused by participation in the catch up program, as the interaction between measurement moment and catch up program participation was not significant [β = 0.07, SE = 0.09, F (1, 1718.43) =0.71, p = 0.40, 95% CI = −0.10, 0.24].

Figure 7. Secondary school students’ scores on motivation, self-concept, school wellbeing, and social acceptance, for the pretest sample and the posttest sample. * indicates significant differences between the two measurement moments. Error bars present standard errors. Note: These differences do not reflect significant changes over time, as both samples constitute different participants.

Pseudo R2 indicated that the fixed effects in the model (marginal R2) accounted for approximately 1.7% variance; with an approximate total of 3.2% explained by fixed and random effects together (conditional R2).

A main effect of measurement moment was found [β = 0.18, SE = 0.05, F (1, 110.03) = 11.70, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.08, 0.29], indicating that students scored higher on social acceptance at the pretest compared to the posttest (see Figure 7). This effect was not caused by participation in a catch up program, as the interaction between measurement moment and catch up participation was not significant [β = 0.13, SE = 0.09, F (1, 1703.32) = 2.47, p = 0.12, 95% CI = −0.03, 0.31].

The aim of this study was to examine school- and student-level characteristics predictive of primary and secondary school students’ social–emotional functioning, specifically: school motivation, academic self-concept, school wellbeing and perceived social acceptance. In doing so, we used data collected during and just after the COVID-19-related lockdowns in the Netherlands. Our findings indicate that in primary school, students attending schools with a higher disadvantage score were more motivated for school compared to those attending schools with a lower disadvantage score. No other school-level characteristics were related to social–emotional outcomes. At the student-level, students in higher grades and students participating in a catch-up program generally were less motivated for school and had a lower academic self-concept and school wellbeing compared to their peers in lower grades and non-participating students. No significant predictors were found for perceived social acceptance.

For secondary school students, school-level factors were not related to their social–emotional functioning. At the student-level, students in higher grades were found to be less motivated and have a lower school wellbeing compared to their peers in lower grades. Likewise, students in the general secondary track were less motivated than their peers in the pre-university track; and students in lower tracks had a lower self-concept than students in the pre-university track. In addition, school wellbeing and perceived social acceptance were lower for students who filled out the questionnaire at post-test, just after the COVID-19-related lockdowns, compared to those filling out questionnaires at pretest, during the period of COVID-19-related school closures. Lastly, students participating in a catch-up program had a lower academic self-concept than their non-participating peers.

Results of our study indicate that individual student-level factors were stronger predictors of students’ social–emotional functioning than school-level characteristics (Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012), which is in line with previous studies reporting that schools accounted for only around 1 to 4% of the variation in students’ mental health (Ford et al., 2021; Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Hinze et al., 2023; Patalay et al., 2020). It has been suggested that such results are caused by a relative uniformity across schools in approaches to students’ social–emotional functioning (Ford et al., 2021). In light of equal educational opportunities, this seems a positive finding, as the school students attend does not, or only to a minor extent, seem to impact students’ social–emotional functioning. It is plausible that all schools can support students’ social–emotional functioning, regardless of their background.

Our study indicates that school-level factors may play a role particularly during primary school (although only specifically for motivation). This in line with previous findings reporting that 11% of the variation in primary school students’ social–emotional functioning was explained by school-level variables (i.e., proportion of students with special needs, average level of academic achievement; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012), whereas the explained variance in secondary schools is suggested to be only around 1–3% (Ford et al., 2021; Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Hinze et al., 2023; Patalay et al., 2020). The school environment is sometimes seen as less supportive for developmental needs of older students (Eccles et al., 1993; Roeser et al., 2000), possibly because students start to attach more value to experiences in their personal environment compared to experiences at school as they enter adolescence, such as at their sports clubs and other leisure time activities (Entwisle and Hayduk, 1988; Sammons et al., 1995). However, other studies have allocated the differences in primary and secondary schools to differences in school and class size, arguing that school effects are generally smaller at the primary school level because of less between-school variation (Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Rutter and Maughan, 2002). Consequently, in primary school, school-level variation may be a reflection of between-classroom rather than between-school differences (Patalay et al., 2020).

Regarding specific school-level factors that were found to be of importance, only school disadvantage score turned out to be related to social–emotional functioning, specifically primary school students’ motivation. Previous studies have consistently found disadvantage score to be linked to students’ behavioral and mental health problems (Ford et al., 2021; Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012; Kellam et al., 1998; Patalay et al., 2020; Saab and Klinger, 2010). Although the mechanisms by which socioeconomic adversity relates to mental health have not been fully understood, these are thought to be multifaceted, involving factors such as parental mental health, family support, and nutrition and sleep (Letourneau et al., 2013; Reiss, 2013). Such mechanisms seem to have had an even larger impact on students’ mental health during COVID-19, with reports of disproportionate effects in disadvantaged populations (Scrimin et al., 2022). Although our results suggest similar relations of disadvantage score when focusing on social–emotional outcomes, we found a significant effect for only one of our four outcome measures, and only for primary school students, suggesting that the a school’s deprivation score does not necessarily lead to reduced student well-being.

In explaining these contradictory results, we expect that social–emotional functioning is more directly related to student background characteristics or to peer-to-peer interactions in the school environment than to broader school-level factors. Equally likely is an overlap in school characteristics that would limit students’ functioning, such as where a disadvantaged school population correlates with poor school management or teacher quality, or high teacher turnover (Smithers and Robinson, 2004). This argument is supported in studies that indicate the importance of school climate: students report better social–emotional functioning in schools with a positive educational environment, where teachers and students feel physically and socially safe, are surrounded by caring and respectful adults, and where their school is managed effectively (e.g., Ford et al., 2021; Hinze et al., 2023; Patalay et al., 2020; Steinmayr et al., 2022). Unfortunately, our study did not include data about these school-level factors. Given that conditions related to school climate are malleable and can be improved through targeted interventions (see for example Charlton et al., 2021), future studies should include these characteristics as predictors of students’ social–emotional functioning.

Our findings show that students in higher grades, both in primary and secondary education, reported lower social–emotional functioning than their peers in the lower grades, indicating that students start to experience more social–emotional problems as they get older. This is in line with findings of previous studies, reporting a growth in mental health problems among older students, with about one third of the students reporting mental health problems by mid-adolescence, mainly among girls (e.g., Hinze et al., 2023; Jones, 2013). Also during COVID-19, social–emotional difficulties and mental health problems were highest among adolescents compared to their younger peers (Schmidt et al., 2021). The rise in mental health difficulties as students move into adolescence is not surprising in itself, given that adolescence is associated with increasing developmental challenges – for example in the context of peer relationships and coping with adversities. These issues may be especially challenging for girls who often have an earlier puberal onset, and a heightened sensitivity for relationships problems (Hinze et al., 2023; Yoon et al., 2023). Our results add to these previous findings by showing that these age differences are also apparent when examining social–emotional functioning – important predictors of students’ mental health (Thomson et al., 2019; Weare and Markham, 2005).

In secondary school students, we found that not only grade, but also track was predictive of student motivation and academic self-concept, with students in lower tracks having a lower academic self-concept; and students in the general secondary track being less motivated, compared to their peers in the pre-university track. These results are consistent with results from PISA surveys that Dutch students in lower tracks experience lower perceived competence and less motivation than peers in higher tracks (Dood et al., 2020; Meelissen et al., 2023). Similar conclusion have been reached in international studies, reporting more motivational problems and lower perceptions of academic ability in vocational compared to academic tracks (e.g., Dæhlen, 2017; Vasalampi et al., 2023). Students in higher educational tracks often have parents with a higher educational background (Jaeger, 2007), who are generally more involved in their child’s education (Rowan-Kenyon et al., 2008). Consequently, these students receive more support for their academic aspirations, which is likely to foster their motivation and their positive perceptions of their own academic capabilities (Vasalampi et al., 2023).

Here, we specifically found a motivational difference between the general secondary track and pre-university track. This result is probably a sampling effect, as the voluntary nature of our project likely had only the most motivated students participating. As motivational differences between tracks tend to be small (Korpershoek et al., 2015), this sampling strategy might have masked motivational differences between the other tracks. Adding to these previous findings, we also show that school wellbeing and social acceptance did not differ for students of the different tracks. Thus, despite being less motivated and having a lower self-concept, students in the lower tracks still seem to be satisfied and feel socially accepted at school to a similar extent as their peers in the higher tracks.

In addition, students who participated in the catch-up programs reported lower levels of social–emotional functioning than their non-participating peers (specifically: lower motivation, academic self-concept and school wellbeing in primary school; and lower academic self-concept in secondary school). This indicates that schools, especially primary schools, had an accurate view of their students’ social–emotional functioning. Previous research has reached similar conclusions, showing lower mental health outcomes among students who were allowed on-site education during COVID-19 (Mansfield et al., 2021). We do not know how schools selected students for participation in their catch-up programs. Schools might have based this choice solely on student academic performance, as students’ cognitive growth is linked to their social–emotional functioning (Quílez-Robres et al., 2021), and information on student grades is more readily available. Still, independently of schools’ rationale for selecting specific students, the programs seem to have reached students that were most in need socially-emotionally. At-risk students were expected to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19 due to a loss of support (e.g., Courtney et al., 2020; Golberstein et al., 2020; Lee, 2020), and because of a cumulation of risk factors within their home environment (e.g., limited physical space, economic challenges, parental problems; Cluver et al., 2020; Courtney et al., 2020; Crawley et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020).

Surprisingly, secondary school students reported lower school wellbeing and perceived social acceptance at post-test compared to pretest. We expected lower social–emotional functioning at pretest, given that pretest data was collected during a period of school lockdowns in the Netherlands, when infection rates and pandemic-related stressors were at a peak and students were not attending school in-person. Posttest data was collected after this initial period of stressors, when there were only limited restrictions due to COVID-19 (schools, stores, and sports clubs were open, people were allowed to meet in larger groups, etc.). It has been suggested that longitudinal exposure to COVID-19-related stressors (social isolation, school disruptions, etc.) has been experienced as additive, meaning that effects may have been not immediately observable, but only manifested later on (Chavira et al., 2022; Racine et al., 2021). Findings from longitudinal studies support this idea, reporting that youths’ mental health worsened throughout the pandemic (Kauhanen et al., 2023; Panchal et al., 2023) – a trend that may have continued also after the initial period of lockdowns was over. Further follow-up on these results seems vital, given the long-lasting negative consequences of social–emotional difficulties (Kauhanen et al., 2023).

Alternatively, as largely different students answered the questionnaires at pre- and posttest differences in social–emotional functioning between pretest and posttest may also be due to sampling differences. Students experiencing more difficulties at posttest (due to the pandemic) may for example have been more inclined to participate than students who did well. Although we approach the same students at both measurement moments, we cannot ascertain that both samples are similar, as we had no background characteristics available, such as gender, age, or socioeconomic status.

This study has several strengths, firstly the focus on school- and student-level predictors of students’ social–emotional functioning – specifically during the period of COVID-19. We examined a variety of characteristics at the school- and student-level simultaneously, this way controlling for possible interactions of between- and within-school effects (Gutman and Feinstein, 2008). In addition, our sample consisted of a relatively large number of Dutch primary and secondary school students, to whom we administrated a battery of validated and reliable questionnaires for this population. Lastly, data were analyzed using robust, reliable analysis methods taking into account both variance at the school- and the individual level (i.e., the nested structure of the data).

As a first limitation, the initial aim of our study was to examine effectiveness of catch-up programs in remediating deficits in students’ social–emotional functioning that developed during school closures as a result of COVID-19. However, too few students filled out our questionnaires both before and after the catch-up programs to reliably assess the effectiveness of the programs. Instead, we focused on student- and school-level predictors of social–emotional functioning. In interpreting these results, it should be considered that this was not the initial aim of the study. Also, as we wanted to guard students’ privacy while limiting the workload for the study, we did not take into account all individual characteristics that may of interest, such as gender, age, socioeconomic or cultural background, behavioral problems, and academic achievement (e.g., Hinze et al., 2023; Rathmann et al., 2020; Patalay et al., 2020; Steinmayr et al., 2022). At the school-level, school climate, school policy regarding personal development, and average student performance have been noted as relevant factors (Ford et al., 2021; Hinze et al., 2023; Humphrey and Wigelsworth, 2012; Patalay et al., 2020; Steinmayr et al., 2022). For future studies, it would be interesting to include a broader range of school- and student-level characteristics to get more insight into between- and within-school differences in students’ social–emotional functioning. Results of the present study may be helpful in determining which factors to include.

Secondly, related to the first limitation, we used data of different measurement points to examine predictors of social–emotional functioning. As data was collected during the period of COVID-19, this means that students’ responses might differ depending on regulations and developments at the specific measurement point. Also, students may feel different at the beginning compared to the end of the school year, for example because of being well-rested just after the holidays, or having developed specific social–emotional competencies throughout the year (e.g., Gadaire et al., 2021). By taking into account measurement moment as a predictor of social–emotional functioning, we aimed to take this limitation into account. Our results show that – indeed, for secondary school students – the timing of measurement of social–emotional functioning mattered for how students felt. This is an important limitation for future studies to take into account, as it indicates that the timing of measurement should be considered when examining how students feel at school.

Thirdly, our study relies solely on parent-reported or self-reported social–emotional functioning, mainly to limit the burden being placed on participating students, parents, teachers, and schools. Although the measures we used are reliable and have been validated for our population, limitations of self-report are well-known, especially among children and adolescents (Abrahams et al., 2019; Martinez-Yarza et al., 2023; Duckworth and Yeager, 2015). Social desirability, difficulties in understanding, misinterpretations, and lack of insight into internal states have commonly been mentioned when using student self-report, especially among younger students (Duckworth and Yeager, 2015). Despite this, it might be difficult for parents to get a good grasp of the inner-feelings of their children (Renk and Phares, 2004), although substantial overlap has been reported between parents’ and children’s ratings of child social–emotional functioning (Berman et al., 2016). It is advised for future studies to triangulate results of questionnaires with those of other measurement tools, such as teacher- and parent-report or independent observations (Denham et al., 2009). This is especially true for between-school or over time comparisons, such as when aiming for program evaluation (Duckworth and Yeager, 2015).

In general, the school-level and individual-level characteristics included in our study only explained a small amount of the variance in students’ social–emotional functioning. This is especially true in primary school (approximately 3–7% of the variance explained in primary school; and 3–14% in secondary school), and for social acceptance (approximately 3% explained variance in primary and secondary school). Previous studies examining predictors of social–emotional functioning have also reported low levels of explained variance, particularly when examining school-level characteristics (e.g., Gutman and Feinstein, 2008; Hinze et al., 2023; Kidger et al., 2012; Rathmann et al., 2020; Saab and Klinger, 2010; Sellström and Bremberg, 2006). Still, this small amount of explained variance in social–emotional functioning does not rule out schools as an important setting for working on students’ social–emotional functioning. Using universal and targeted interventions, schools can have a direct impact on their students’ social–emotional functioning (Cipriano et al., 2023; Dray et al., 2017; Durlak et al., 2022, p. 34), and such small school-level effects can have meaningful impacts on future health and well-being (Ford et al., 2021).

Yet, it seems of interest to explore other, unexamined factors underlying differences in students’ social–emotional functioning. Well-established theoretical frameworks, such as Deci and Ryan (1985) Self-Determination Theory, Bandura (1986) Social-Cognitive Theory, Vygotsky (1978) social developmental theory, or Bowlby (1973) attachment theory may help in identifying factors of relevance. Examples are parental support, self-efficacy, resilience, and personality (Allen et al., 2018). Indeed, factors identified in leading theories (e.g., parental support and parent–child relationships, resilience) alongside lifestyle behaviors (screen time, sleep quality, physical activity) also proved to be major risk/protective factors for students’ wellbeing in the period of Covid-19 (De Figueiredo et al., 2021; Ng and Ng, 2022). Additionally, a different approach may be needed, where the focus is not solely on the school-context, but also on other environments influencing students’ development, taking a more ecological approach by considering the whole system surrounding the developing child (following for example Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological theory; Bronfenbrenner, 1992; Sameroff’s Transactional Model of Development; Sameroff, 2009).

Complicating this type of research is that there is no common consensus upon the framework to use when examining social–emotional functioning in educational settings (Abrahams et al., 2019). Consequently, it is difficult to choose the outcome domains to include when examining students’ social–emotional functioning. Possibly, our results would have been different if we had used different outcome domains or measurement instruments. There is no consensus on what “social–emotional functioning” entails, meaning that researchers are prone to make decisions based on their own preferences. This limitation is also reflected in practice, where there is a large variety in social–emotional constructs being monitored by schools; and a multitude of available measurement instruments (Cipriano et al., 2023). For cognitive learning outcomes, schools typically make use of academic monitoring systems to keep track of their students’ progress. For structural evaluation of school policies and program effectiveness for students’ social–emotional functioning, such a structured monitoring system would be vital as well. This would also allow for closer examination of interrelations between students’ cognitive performance and social–emotional functioning. Given the difficulties associated with monitoring social–emotional functioning (Abrahams et al., 2019), a critical consideration of the competencies to be included in such a system, and the best way for structurally monitoring them seems vital for future studies and policies. We therefore strongly advocate the development of a general framework for social–emotional functioning – entailing important constructs for schools, teachers, and students. Such a framework is also vital for guiding the development, implementation, and use of appropriate measurement instruments (Abrahams et al., 2019).

Given that students’ social–emotional functioning is closely linked to their cognitive functioning (Durlak et al., 2022; Mahoney et al., 2018), it seems a fruitful endeavor to examine whether the characteristics that we found to be predictive of students’ social–emotional functioning are also relevant for their cognitive outcomes. Many schools feel the pressure to focus their curricular goals on students’ cognitive development, given the importance that national and international policymakers attach to well-developed academic skills. Thus, schools will greatly benefit from methods that can simultaneously target their students’ social–emotional functioning and cognitive performance. A closer examination of the student characteristics that are related to both cognitive and social–emotional outcomes can give important insights into which students may benefit most from such interventions. Our results give some insight into characteristics that may be of relevance to include.

In general, for school policy, our results indicate that students in higher grades and lower tracks may be most at risk for hampered social–emotional functioning, especially during adverse circumstances (such as a pandemic). In developing strategies for strengthening students’ social–emotional functioning, special attention for these at risk populations thus seems warranted, especially since interventions for social–emotional functioning seem to be more effective for younger students than for their older peers (Durlak et al., 2022). Educational policies should take individual differences into account when deciding upon effective approaches aimed at targeting social–emotional functioning. Importantly, teachers may need support to successfully implement strategies to ensure beneficial outcomes for all students, meaning that continuous professional development is crucial for implementation of effective policies (Cipriano et al., 2023).

In this study, we examined student- and school-level characteristics predictive of students’ social–emotional functioning, specifically in the period during and just after COVID-19. School-level characteristics played a minor role in explaining differences in students’ social–emotional functioning. Of the four factors examined, only school disadvantage score was a significant predictor, specifically for motivation of primary school students. At the student-level, primary school students in higher grades and participating in a catch-up program were less motivated for school, and had a lower academic self-concept and school wellbeing compared to their lower-grade peers and non-participating students. In secondary school, students in higher grades had a lower motivation and school wellbeing compared to their lower-grade peers; catch-up program participants had a lower academic self-concept than their non-participating peers; and perceived social-acceptance and school wellbeing were significantly lower in the post-COVID-19 sample compared to the pretest sample who participated during the period of lockdowns. These results underline the importance of student characteristics in predicting school experiences, pinpointing factors that schools should be aware of when aiming to identify students at risk for problems in their social–emotional functioning. Given the convincing evidence of effectiveness of social–emotional intervention programs for fostering students’ social–emotional functioning (Cipriano et al., 2023), our results may help schools in successfully identifying students most at risk for social–emotional difficulties. This can consequently successfully help this population of students by providing targeted social–emotional intervention programs.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation, upon reasonable request.

The studies involving humans were approved by Vaste Commissie Wetenschap en Ethiek—Faculty of Behavioral and Human Movement Sciences—Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ME: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. AK-R: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1514895/full#supplementary-material

Abrahams, L., Pancorbo, G., Primi, R., Santos, D., Kyllonen, P., John, O. P., et al. (2019). Social-emotional skill assessment in children and adolescents: advances and challenges in personality, clinical, and educational contexts. Psychol. Assess. 31, 460–473. doi: 10.1037/pas0000591

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., and Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 1–34. doi: 10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Berman, A. H., Liu, B., Ullman, S., Jadbäck, I., and Engström, K. (2016). Children's quality of life based on the kidscreen-27: child self-report, parent ratings and child-parent agreement in a Swedish random population sample. PLoS One 11:e0150545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150545

Betthäuser, B. A., Bach-Mortensen, A. M., and Engzell, P. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 375–385. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). “Ecological systems theory” in Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. ed. R. Vasta (London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 187–249.

Charlton, C. T., Moulton, S., Sabey, C. V., and West, R. (2021). A systematic review of the effects of schoolwide intervention programs on student and teacher perceptions of school climate. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 23, 185–200. doi: 10.1177/1098300720940168

Chavira, D. A., Ponting, C., and Ramos, G. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health and treatment considerations. Behav. Res. Ther. 157:104169. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2022.104169

Cipriano, C., Strambler, M. J., Naples, L. H., Ha, C., Kirk, M., Wood, M., et al. (2023). The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: a contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Dev. 94, 1181–1204. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13968

Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Sherr, L., Wessels, I., Krug, E., Rakotomalala, S., et al. (2020). Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 395:e64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4

Courtney, D., Watson, P., Battaglia, M., Mulsant, B. H., and Szatmari, P. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: challenges and opportunities. Can. J. Psychiatry 65, 688–691. doi: 10.1177/0706743720935646

Crawley, E., Loades, M., Feder, G., Logan, S., Redwood, S., and Macleod, J. (2020). Wider collateral damage to children in the UK because of the social distancing measures designed to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in adults. BMJ Paediatr. Open 4:701. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701

Dæhlen, M. (2017). Completion in vocational and academic upper secondary school: the importance of school motivation, self-efficacy, and individual characteristics. Eur. J. Educ. 52, 336–347. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12223

De Bruijn, A. G. M., and Meeter, M. (2023). Catching up after COVID-19: do school programs for remediating pandemic-related learning loss work? Front. Educ. 8:1298171. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1298171

de Bruijn, A. G. M., Sincer, I., Turkeli, R., Meeter, M., and Ehren, M. C. M. (2021). Inhaal-en ondersteuningsprogramma’s om leerachterstanden te remediëren: theory of change aanvragen PO en VO uit de tweede tranche van de subsidieregeling i.v.m. COVID-19; rapportage deelstudie 1. Amsterdam: LEARN! Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

De Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L. C. L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í., et al. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents' mental health: biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 106:110171. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Boston, MA: Springer US.

Deng, J., Zhou, F., Hou, W., Heybati, K., Lohit, S., Abbas, U., et al. (2023). Prevalence of mental health symptoms in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1520, 53–73. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14947