95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 19 February 2025

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1513668

Natalie Tyldesley-Marshall†

Natalie Tyldesley-Marshall† Rebecca Johnson‡

Rebecca Johnson‡ Janette Parr†

Janette Parr† Anna Brown†

Anna Brown† Iman Ghosh†‡

Iman Ghosh†‡ Amin Mehrabian†‡

Amin Mehrabian†‡ Yen-Fu Chen†

Yen-Fu Chen† Amy Grove*†‡

Amy Grove*†‡Background: Effective collaboration between different services is recommended by government policy for children and young people (CYP) with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) across many countries. In the UK, despite significant shifts in policy towards partnership working, there remains a scarcity of scientific evidence on how this should be achieved. This mixed methods systematic review examined interventions leading to improved service outcomes for multiagency working for CYP with SEND.

Method: Eleven databases generated a total of 7,473 results. Data from 137 selected studies were analysed. However, only qualitative research findings from thematic synthesis regarding key ingredients of effective partnership are reported.

Results: From these, five key ingredients for effective partnership working in SEND services were identified: (1) participation, and legitimacy to participate in a partnership; (2) personalisation and consultation with children, young people, and their families in designing and delivering services; (3) respectful communication, and feeling that involvement is valued; (4) preparation to be an effective member of a partnership; and (5) working across professional and organisational boundaries.

Conclusion and implications: To facilitate practical application of the findings, three exemplar cases of effective partnership are explored. A framework to support partnership design, collaboration, and the development of evidence-based recommendations, is presented.

Systematic review registration: The study protocol for this study was registered in PROSPERO CRD42022352194.

Across countries, there can be great variation in policy and practice for services for children and young people (CYP) with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND). In England, for example, a child is recognised as having SEND if they have a learning difficulty that requires special educational provisions to be made. In contrast, in the United States, children must have a ‘defined disability’; while in Australia, support is eligible for those that have ‘evidence’ of an impairment that impacts their learning (Wood and Bates, 2020).

Despite this, there does seem to be a common recognition that the interconnectedness of services supporting CYP with SEND necessitates collaboration to effectively support these young people’s health, education and welfare (Rix et al., 2013). Although internationally, there is little consensus about the most effective ways to encourage this (Wood and Bates, 2020).

In the United Kingdom (UK), the Children and Families Act by the Department for Education (DfE; Children and Families Act, 2014) aimed to improve collaboration and partnership working between service providers for CYP with SEND. Policy recommendations suggest that continuity of care for each child or young person could be improved if duplication of work by different service providers was reduced and support was coordinated. Through better coordination of services, the number of children who “slip through the net,” or only start receiving services when problems have become severe, could be reduced (DfES, 2003; p. 68).

Effective collaboration and partnership between multiple agencies or departments within and between the fields of health, social care and education, hereafter referred to as “partnership,” is recommended as a crucial element for the coordination of assessments as well as organisation of services. It aims to provide joined-up services to CYP with SEND and their families (Palikara et al., 2019), and to promote children’s full participation and wellbeing (Castro and Palikara, 2016). Partnership requires multiple forms of expertise and services to effectively liaise to best support CYP with SEND and their families. In this context, the multiple providers recognise the needs of each child in all areas of life, from education to health, and social care.

In the UK, effective collaboration between different departments is recommended by the DfE and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in the SEND Code of Practice, 2014 (updated in 2015; DfE, DHSC, 2015); Every Child Matters by the UK Government in 2003 (DfES, 2003), the SEND review (DfE, DHSC, 2022); and recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines which state that for CYP with severe, complex needs, all “education, health and social care practitioners should collaborate to develop a positive working culture and take time to develop positive relationships with each other” (NICE, 2022; p. 147). There is evidence that collaboration between these services is important for effective service provision (Lynch et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 1998), as well as promoting “holistic development across life domains” (Castro-Kemp and Samuels, 2022).

Despite the significant shifts in policy towards partnership working in SEND, there remains a lack of pragmatic guidance on how this integration should be achieved. The organisation of health and care organisations itself can be a challenge, as care from different services is viewed as disparate and unconnected: “a jigsaw rather than a series of dynamic and localized events” (Gibson et al., 2023). Whilst the boundaries between education, health and social care have blurred in response to complex care needs and vulnerable populations, an increase in service integration generates increased service complexity (Greenhalgh and Papoutsi, 2018; Bharatan et al., 2023). This complexity can be problematic for the professionals who are responsible for implementing changes in the assessment and identification of CYP in need of special support. Providers already face challenges including short, pressured timelines and restricted budgets (Palikara et al., 2019). In England for example, the high needs budget for Local Authorities (LAs) has been increased by £2.5 billion since 2020 (up to £9.1 billion as of June 2022). However, a significant proportion of LAs are struggling to deliver service requirements within budget (DfE, 2022).

A report by the DfE suggested that there is a correlation between LAs that place higher value on collaboration and stronger collective culture, and those that manage their budgets effectively (DfE, 2022). Therefore, evidence suggests that when different professional disciplines work together, the effectiveness of SEND service provision can be improved. However, there is a gap in understanding how best to implement changes in provision of services for CYP with SEND following the 2014 Children and Families Act (Palikara et al., 2019).

A larger mixed methods systematic review was undertaken, which aimed to identify effective interventions that lead to improved service outcomes for CYP with SEND, (of which effective partnership was assumed to be one such intervention), and conditions that facilitated their success. The conditions for success identified in the larger review were: Flexible service delivery; Interventions designed with service stakeholders; Co-produced interventions with CYP with SEND; Regular, open and clear communication between stakeholders; Relationship development; Multi-agency working and information sharing; Expectations are clear between stakeholders; and Opportunities for change through policy reform. The findings reported here are in part, corollaries from these conditions for success, and are reflected in our contextualisation of effective partnership practice. However, the conditions for success were not identified through qualitative analysis alone, so are not discussed here further. This paper focuses on reporting findings regarding effective partnership work in SEND services. The full protocol can be found elsewhere (Tyldesley-Marshall et al., 2023).

Two research questions were developed, although this paper reports on the findings for Question 2:

1. In relation to health, social care, and education services for those aged 0–25 years with SEND, what are: (a) effective interventions that lead to improved service outcomes, and (b) the conditions for success in the local area?

2. (a) What are the key ingredients for effective partnership, or joint commissioning, of health, social care, and education services to those aged 0–25 years with SEND? and (b) Where these services are provided for those aged 0–25 years with SEND, what are the most effective ways of achieving improved outcomes (as defined by the individual literature, for example, co-location of services, or an explicit, documented process) when working together?

The search strategy was developed by an information specialist (AB) in collaboration with the research team, topic advisors from academia, members of the Research and Improvement in SEND Excellence (RISE) partnership—a group of professionals from education, SEND services, and charity/third sector providers, and patient and service user input via the RISE partnership. Records were retrieved from a range of health, nursing, education, sociology, social care, social policy, and management databases, in addition to Google Scholar and relevant websites (Supplementary File 1). Search terms included terms used for indexing in databases, such as medical subject headings/MeSH, where available, as well as additional descriptive words and phrases (free-text keywords). Database searches were run during September 2022. To keep findings contemporary and relevant, these were limited by filters to records published from 2012 to the day that each search was run; and studies from the UK. In addition, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, known to the authors to be interested in research and/or policy relating to CYP with SEND were contacted for their help to identify relevant studies, and reports (a ‘Call for Evidence’). Later, once our list of included studies was finalised, the reference lists for these were checked for further papers of potential relevance, as were papers that referenced our finalised list included studies.

Table 1 reports the PI/ECOSS framework of pre-defined eligibility criteria used to identify relevant quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies for inclusion (Booth et al., 2022). Literature was excluded if the findings reported from those with SEND aged 0–25, their families, or professionals, could not be separated; or if findings from the research undertaken in the UK could not be separated. Articles which did not report empirical research were excluded, e.g., editorials. Studies where the interventions were found to be ineffective, and those targeted at families of CYP with SEND rather than CYP with SEND themselves, were also excluded. Literature that was not published in a peer-reviewed academic journal was not included in the analysis, though a list of the most relevant of these was compiled (Supplementary File 2). Google Translate1 (Google, 2006) was used for any identified abstracts, or texts, not written in English (Odukoya et al., 2022).

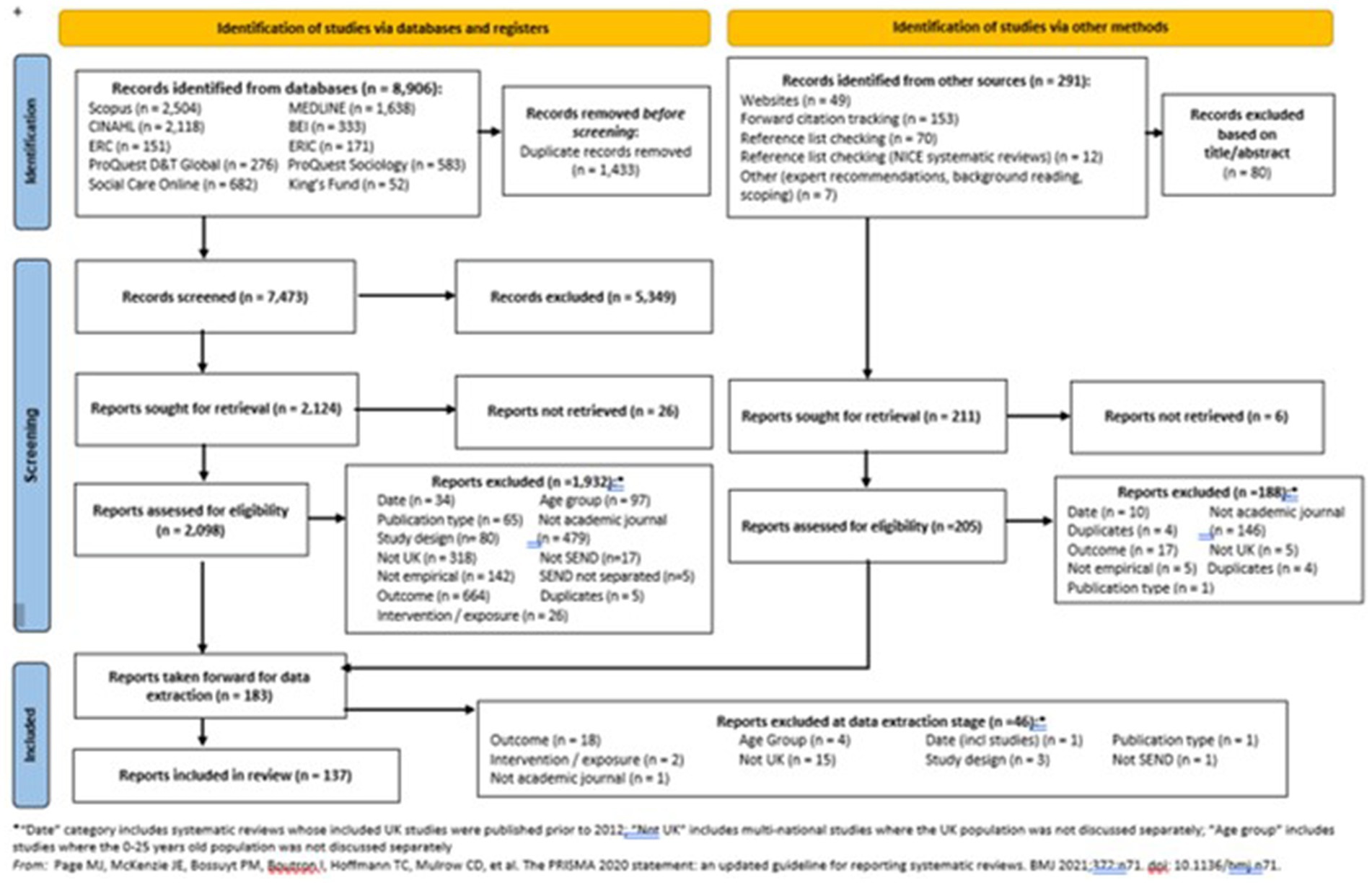

Database searches retrieved 8,906 records. De-duplication in EndNote 20 (Clarivate, 2020) left 7,473 records transferred to Rayyan software (HBKU Research Complex, 2016) for screening. Dual independent screening was undertaken at the title and abstract level, and then full text level. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or a third reviewer. After the title/abstract screening, 2,124 records, plus an additional 211 from other sources, were retrieved to be examined (Figure 1). Thirty-two could not be retrieved, and a further 2,166 were excluded after reading the full text (or found to be ineligible at the data extraction stage); see Supplementary File 3 for list of exclusions, ordered by reason for exclusion). Therefore, 137 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Figure 1 summarises this process in a PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021). Forty-one were quantitative studies, (further detail reported elsewhere (Tyldesley-Marshall et al., 2024), leaving 96 included studies: 59 qualitative studies, and 37 mixed methods studies. Screening was undertaken by NT, JP, IG, and AM, and AG.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study selection flow diagram.

*“Date” category includes systematic reviews whose included UK studies were published prior to 2012; “Not UK” includes multi-national studies where the UK population was not discussed separately; “Age group” includes studies where the 0–25 years old population was not discussed separately.

Relevant data in line with the research questions were extracted from all included studies, using a piloted tool (Supplementary File 4) by NT, JP, IG, and AM. The extracted information included: sample, study design, intervention/service model, data answering the research questions, and use of Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE)2 (NIHR: Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands, 2022). Authors were contacted for missing or ambiguous data. The extracted data were checked for accuracy by a second reviewer and entered into a Table of Study Characteristics (Supplementary File 5).

Each paper was regarded as a separate study. Included studies were critically appraised according to their study design. Classification of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods was based on both analysis and presentation of data. Thus, a survey presenting responses to both open and closed questions separately was classified as a mixed methods study. However, if the responses from the open questions were transformed to quantitative, and presented with the responses from the closed questions, or only closed question responses reported, then this was classified as a quantitative study. Joanna Briggs Institute tools were used for analytical cross-sectional; cohort; qualitative; and quasi-experimental studies (Lockwood et al., 2015); and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018) for mixed methods studies. (Results of qualitative and mixed methods study appraisal can be found in Supplementary File 5. Results of Risk of Bias assessments for quantitative studies are presented elsewhere (Tyldesley-Marshall et al., 2024)). Critical appraisal was performed to explore the methodological strengths and limitations for each study and not for the purposes of exclusion.

For the qualitative studies, and the qualitative components extracted from mixed methods studies, the methods of qualitative evidence synthesis outlined in the Cochrane Handbook were adopted (Higgins et al., 2022)3. The 96 included studies were grouped according to study design, i.e., qualitative, or mixed method (Popay et al., 2006).

The study data could be any element of the Findings and/or Discussion from the included article and included both direct participant quotations and author description and interpretation. A thematic synthesis method was employed that has been used previously in systematic reviews for exploring experiences, attitudes and perspectives (Thomas and Harden, 2008). The approach was chosen as it is “both accessible and adaptable to varying breadths of qualitative data” (Chahley et al., 2021). Codes were developed inductively, and length of text coded ranged from a phrase to multiple sentences, to maintain meaning and context (Thomas and Harden, 2008; Noyes et al., 2018). All qualitative data were reviewed by a second reviewer (AG). Codes were organised into related areas, i.e., descriptive themes. The data were read and re-read, and the descriptive themes developed into final analytical themes by AG, in line with the review questions (Thomas and Harden, 2008).

One hundred and thirty-seven articles were selected to be included: 59 qualitative studies, 37 mixed method studies, and 41 quantitative studies. (Citations for all 137 can be seen in Supplementary File 6). Of the 96 qualitative and mixed methods, 39 were conducted in England; six in Scotland, one in Wales; and 50 were reported as being conducted in the UK, or across the UK. Sample population sizes in the qualitative and mixed methods studies ranged from one (e.g., 1 person, or 1 case) to open-ended survey responses from 245 individuals, and to case study research which included three child therapy services with 46 therapists and 558 children participating. Studies focused on the experiences of mixed professional groups, as well as CYP and their families. (Details of included study characteristics are in Supplementary File 5).

Five themes were identified in the thematic synthesis of qualitative data which describe the key ingredients to effective partnership in SEND services: (1) participation, and legitimacy to participate in a partnership; (2) personalisation and consultation with children, young people, and their families in designing and delivering services; (3) respectful communication, and feeling that involvement is valued; (4) preparation to be an effective member of a partnership; and (5) working across professional and organisational boundaries. These themes are described using three exemplar qualitative studies.

The exemplar qualitative cases were selected due to their explicit description and exploration of partnership within SEND services to provide a breadth of description across the broad range of 96 included studies (Barlow and Coe, 2013; Green and Dicks, 2012; McKean et al., 2017). The first study, Green and Dicks (2012), is a case study which describes a three-year partnership between a case manager in health and a social worker providing services for CYP with difficulties caused by brain injury (Green and Dicks, 2012). The second, Barlow and Coe (2013), focuses on early education partnerships with a health visiting service. This involved 25 interviews with stakeholders including staff at a children’s centre, a range of voluntary sector organisations, staff from health visiting services, and service users (Barlow and Coe, 2013). The third is a case study of interprofessional collaboration for children with speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN). In this latter study, partnership was explored in the LA setting to understand the range of social capital relationships and how these affected the abilities of partner members to collaborate (McKean et al., 2017). Figure 2 below, presents each of the five ingredients for effective partnership as identified in our review.

The literature depicted partnership participation in two ways. The first were literal descriptions of who or which professionals or agencies participate in a partnership in SEND services. For example, in Green and Dicks (2012), participation was between a social worker and a case officer responsible for the aspects of CYP’s clinical care (Green and Dicks, 2012). In Barlow and Coe (2013), the voluntary sector, education, and healthcare professionals participated in the partnership. Here, partner members either did not contribute effectively through choice, or were not able to, meaningfully contribute. Therefore, relationships were transactional in nature. An important distinction in partnership participation was the difference between an agency/actor participating in a partnership, and them having the legitimacy to participate in the partnership (McKean et al., 2017).

The second type of partnership describes partners who appeared to have joint responsibility for service delivery. These partners took actions and risks together and their autonomous decision-making was supported by their organisations (Barlow and Coe, 2013). Green and Dicks (2012) illuminate this distinction well. In this first quote, an occupational therapist was instructed to provide a discrete service which is more aligned to the first type of partnership working:

“A privately funded brain injury occupational therapist was instructed to work with Jake [the young person] and his mother, to enable management of his difficulties and behavioural problems and develop independence skills” (Green and Dicks, 2012; p. 10).

Green and Dicks (2012) also describe partners who have legitimacy to participate in partnership work in the quote below.

“While the case manager valued and relied on the social worker’s enhanced knowledge of deaf needs, it was also necessary [for the case manager] to provide education about brain injury. Jake [the young person] encountered stigma associated with the use of the term brain injury, particularly at school and the case manager was able to spend time in school to provide brain injury education to staff” (Green and Dicks, 2012; p. 10).

Effective partnership reflected collaborative, rather than transactional partnership practice (McKean et al., 2017). For partnerships to be effective, the partners ought to take joint responsibility for actions and decisions and adopt a supportive relationship among all parties involved. The literature suggests that a partnership member seemed to require a sense of legitimacy in the partnership, which stemmed from support at an organisational level. This support appeared to enable the partner’s autonomy to make and act on decisions within the partnership. In Green and Dicks (2012), both partners were in a position to make changes “on the ground within a short timescale” for the benefit of the young person; without excessive bureaucracy or negotiation with their respective organisations (Green and Dicks, 2012; p. 10).

An important ingredient to effective partnership working appeared to be the personalisation towards, and consultation with, the service users, i.e., CYP with SEND and their families. This appears to benefit both service users and service providers. McKean and colleagues demonstrated how highly collaborative forms of partnership between organisations, (what they termed “co-practice”), brought benefits to the organisational partners, such as greater capacity to individualise services to the needs of the CYP (McKean et al., 2017). They found that across the partnership, individual capacity was increased in terms of their ability “to harness the overall resource distributed amongst members of the inter-professional team” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 514).

The authors found that the needs of families with SLCN were a priority for those providing SLCN services, and they highlighted the benefits to inclusive practice which were gained via collaborative working (McKean et al., 2017). Similarly, in Barlow and Coe (2013), those who worked for a Peers Early Education Partnership (PEEP), believed strongly in their service, and the resultant benefits of working collaboratively with standard child health clinics (Barlow and Coe, 2013).

This user-centred approach to partnership in SEND appears to enable service providers from different agencies to flexibly adapt their service delivery depending on the needs of the service users. Personalisation, and in a similar vein, consultation, could therefore, potentially focus attention on the CYP needs, and deflect competing demands from partnership agencies that may not necessarily be the same as the needs of service users. Barlow and Coe (2013) described how professions in a PEEP had different stated objectives in terms of their early goals for the service, but that “despite these differences good progress was achieved in terms of working together effectively” to respond to the needs of the service users (Barlow and Coe, 2013; p. 36). An explicit partnership was forged across sectors, and multiple agencies, with an aim of improving outcomes for CYP and their families. All participants in this study referred to the partnership as having “improved the quality of the clinic environment, and service users identified a wide range of benefits from the enhanced service such as increased levels of confidence and personal development” (Barlow and Coe, 2013; p. 36).

Green and Dicks (2012) describe this process of personalisation, or maintaining a focus on the user, in foster care placements for a young person with brain injury:

“The social worker was willing to think creatively for a solution that did not fit within the standard service provision to disabled young people requiring emergency accommodation” (Green and Dicks, 2012; pp. 8-9).

The partnership was deemed successful because the professionals were able to adopt new perspectives which focused on the user. Members of the partnership were able to work outside of their organisational constraints, “maintaining the client’s goals and needs at the centre of all decision making,” (Green and Dicks, 2012; p. 8) in order to find a more satisfactory solution for the young person. The lessons from this seem to be clear: professionals should be consistently reminded throughout their training to always put the service users at the centre of their actions, and the user’s needs as their priority.

The previous two themes demonstrate how communication is a fundamental component of partnership working. However, for partnerships to be effective, and to generate improved outcomes for CYP, the communication between agencies and professionals needs to be moderated and respectful (McKean et al., 2017). Both agencies involved in the partnership in this case of Green and Dicks (2012) (e.g., social workers and case managers) were open to moderated discussion, which allowed them to share what they expected from the other party and be clear in setting the expectations for what they would deliver. Both in terms of their capacity to deliver the service and the clear expectations of the aims of the work with CYP.

Further, mutual respect and understanding of different points of view was essential for partnership working (Green and Dicks, 2012). Partners utilised their knowledge of the young person to jointly risk assess and plan what services could be provided, and what needed to be sourced from elsewhere. The partners in this study, were able to demonstrate mutual respect and identify gaps in knowledge and additional services sought in rapid response to a crisis situation. This appeared to facilitate a longer-term, planned and coordinated rehabilitation plan with contingency planning for the future. Each partner had skills and knowledge that the other lacked which helped to ensure that the other partner’s contribution was valued:

“While his social worker had provided excellent deaf-focused services, it was evident that Jake [young person] would benefit from [additional] tailored rehabilitation from therapists skilled in dealing with his specific cognitive and behavioural problems, and with brain injury experience and expertise” (Green and Dicks, 2012; p. 7).

“The social worker was able to approach private case management with the view that there was no threat or criticism of service delivery rather as a way of “topping up” what could be provided by the stretched services battling to meet the diverse needs of disabled children in Jake’s local area” (Green and Dicks, 2012; p. 8).

Preparation in our review, represented the practical side of partnership working. Actions undertaken to prepare for being an effective member of a partnership were important and necessary for effective partnership working.

Preparatory activities to ensure partnerships could work together effectively included dedicating time to face-to-face meetings, establishing goals and desired outcomes for CYP for the partnership, and dedicating time to allocate responsibility for different actions (Green and Dicks, 2012). As depicted in the following quote:

“The case manager and social worker were able to meet regularly to plan actions, and a person-centred plan was used with Jake to continually identify his “felt need’” […] The close contact between the case manager and social worker, [was] essential for delivery of a coordinated service” (Green and Dicks, 2012; pp. 8-10).

Time to prepare for partnership working was partnership work in itself. This was in addition to professional service work partners needed to perform to deliver services for CYP. While partnership working may appear time-consuming in a time- and resource-limited environment, the close relationships that developed from this partnership work were essential for delivery of coordinated services for CYP. They could therefore be viewed as a worthwhile investment for organisations who deliver SEND services (Green and Dicks, 2012). Recognition, however, is required that preparation is a legitimate use of time and resources for an organisation, and should be accounted for accordingly, rather than seen as optional, or an “add on.” We believe that that this is worth the investment given the benefits for partnership. While this preparation will impact upon time and resources, this impact could be reduced if discussed and addressed within existing team meetings.

The final theme recognises the importance of developing a successful model of partnership working which prioritises SEND services as whole, over and above the individual organisations or agencies. McKean et al. (2017) described how effective partnership was achieved in one LA in England when “skills, knowledge and resources are distributed amongst professionals and agencies” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 514). McKean et al. (2017) theorise that resources being devolved to schools has enforced negotiation between professionals in schools and other professional services, which they found improves personalisation, and working across boundaries in partnerships.

In Green and Dicks (2012), where a case manager had more resource available to them (from the organisational level), they were able to take primary responsibility for the young person’s case, understanding and acknowledging that the social worker had a heavy workload at the time. Sharing resources, as well as knowledge of the other partners via regular communication, allowed for the social worker and case manager to share responsibility to address the young person’s needs, as well as more effectively work across organisational boundaries (Green and Dicks, 2012).

We found that the lack of effective work across boundaries hindered professional relationships and outcomes for CYP. This can result from “border disputes and poor awareness of respective priorities” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 514). For example, when professionals did not reach out, and into, other agencies this was seen as detrimental to effective partnership in early education partnerships with health visiting services (Barlow and Coe, 2013). Similarly, when one professional acted as if their views were more important than others, then “trust and reciprocity evaporated” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 521), and this damaged effective working between the different teams in the partnership.

Successful partnerships were found to be underpinned by other elements, such as sharing knowledge. In Green and Dicks (2012), the partners (a social worker and case manager) shared knowledge, and understanding of each other’s knowledge gaps and how they could be filled, in order to coordinate to improve services for the young person with SEND (Green and Dicks, 2012). In their study of neurological disability, Green and Dicks (2012), found regular, open, and clear communication were an important element of partnership working, which aided the management of expectations across the organisations and partners involved.

McKean et al. (2017) found that the hierarchy in an organization can impact on legitimacy to participate, and working across boundaries. Organisations with more flexible hierarchies allowed actors more flexibility to act, and have autonomy to act, whilst organisations with more rigid hierarchical models were found to reduce staff’s sense of agency to act, and their ability to negotiate the actions they undertook.

Barlow and Coe (2013) found PEEP clinics were based within traditional child health clinics. This sharing of physical spaces facilitated greater understanding in PEEP practitioners and members of the healthcare teams of each other’s roles, more effective working relationships, and ultimately aided recognition of “complementary expertise, and mutual trust and respect [that] was evident throughout the interviews” (Barlow and Coe, 2013; p. 41). Health visitors and those who worked for a PEEP in the same location, described learning much from each other through integrated working practices:

“I think certainly our practitioners are much clearer on what the particular parameters are in which health workers operate and they therefore understand their role I think much better. (#3 PEEP manager)” (Barlow and Coe, 2013; p. 40).

McKean and colleagues found that a values-based approach where the “child and family [are] at centre” was reported as an essential requirement for the personalisation of services. This approach enabled the professionals involved to feel that their involvement was valued, as this Special Educational Needs Coordinator reports:

“ultimately we all have the child at the forefront of what we are trying to benefit so it’s not like we are on different sides erm … it’s purely yes there is a need and we want to do the best we possibly can for this child … and it’s always about negotiating how best both parties can do that … So I just think there is a mutual respect” (McKean et al., 2017; pp. 521-522).

The belief that others in the partnership shared the same values also helped to engender trust and reciprocity in partnerships, which appeared to result in stronger partnership working (McKean et al., 2017).

Actions such as setting time for partner members to meet regularly, and planning using a person centred plan may appear simple. However, they were the tangible building blocks of partnership working that enabled the intangible elements of partnership working (i.e., trust and reciprocity) to develop over time. In the literature we found that regular face-to-face meetings, sharing statements which allowed them to outline expectations, and clarification of their own partnership expectations appeared to contribute to successful outcomes for CYP (Green and Dicks, 2012).

One study described SLCN provision by an LA in England and its linked National Health Service partner. It identified that the creation of strong working relationships across professional boundaries “was easiest where individual staff had worked together for extended periods and/or liaised very frequently” […] “Activities to develop relationships, such as cross-agency professional development, were highly valued as opportunities to build co-professional knowledge and ‘ties’ of trust.” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 521). In this study, the integration of services created new complexities, for which additional preparation was required. This encompassed the provision of organisational-level resources (such as time and people) to allocate to partnership work. McKean et al. (2017) identified the following as a contextual factor of primary importance…having“[s]ufficient resources of time and skills for staff to liaise and support children with SLCN. This allowed the development of trust which can potentially maximize developing and deploying human and social capital resources,” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 524).

The findings suggest that clear communication and understanding partnership roles and boundaries resulted in successful partnership. McKean et al. (2017) were keen to stress that clarity “should not be confused with rigidity or with entirely non-overlapping role delineation” (McKean et al., 2017; p. 523). Overlapping and flexible role boundaries necessitated negotiation and communication around services, to tailor to the needs of families, engendering trust facilitating the partnership (McKean et al., 2017).

Our review aimed to identify the key ingredients of effective partnership working; however, we also identified underpinning elements to these. We suggest that all these align and interact as part of a dynamic process of partnership. To illustrate this, we created a 2×2 matrix which is shown in Figure 3. The matrix demonstrates how the ingredients for partnership can be organised on an operational plane, where the ingredients are organised across two intersecting continuums: tangible-intangible plane shows ingredients which partnerships can enact to increase chances of successful interventions and partnerships.

Tangible ingredients reflect organisational, actionable activities that can be developed within and between partnerships—they can be mutually agreed, characterised and constructed. On the other end of the continuum are the intangible ingredients which reflect characteristics, values, and beliefs which partnerships can work to embody. They appear harder to record and report, and harder to develop, but essential to the dynamic process of partnership.

The second plane depicts the relational-structural continuum of partnership. Relational ingredients can be difficult to construct or agree in principle. For example, ‘trust’ can be defined and its importance stated, but it is developed through partnership interactions over time, sharing and exchange, following through on expectations, showing understanding of boundaries, and reflecting valuing in what other partners have to offer the partnership. Structural ingredients (or ingredients with structural characteristics) reflect constructed, outlined, boundaried operations or activities for partnerships. Our review of literature shows that critical for successful SEND partnerships is the requirement for a spread of ingredients across each section of the two continuums, creating the four sections observed in Figure 3. The weighting of ingredients will vary across differing contexts, settings, and in terms of where emphasis lay in the interaction between organisation and SEND activity.

Our findings showed that the components of partnership include each of the four domains. Tangible/structural facilitators include constructive, strategic and logistic activities that partnerships can develop at the start of a new or emergent partnership. For example, preparation to participate may include consideration of certain conditions for intervention success, such as identifying what flexible service delivery means to each partner and how this might introduce optimal ways of working or potential sources of conflict (for instance, if flexibility in one activity introduces challenge or conflict in another). When considering participation and legitimacy to participate, the design of an intervention (or innovation or adaption) which includes service stakeholders, as well as CYP with SEND, should set up an intentionally inclusive participation environment that more equitably distributes contribution power. In contrast, the relational/intangible domain reflects the value of attending to nuanced and interpersonal aspects of working in partnerships—building trust, values alignment and feeling valued etc. These domains are not mutually exclusive. We have organised them to reflect the balance of structural practices, strategies and activities coupled with relational interactions and the understanding that practicing partnership requires an ongoing dialogue within and between each domain. However, we note that trust, reciprocity, and values alignment recurred across many of the themes.

This review aimed to understand what effective partnership practice looks like, and what the key ingredients of effective partnership working are. In reviewing and analysing the qualitative literature, five themes were identified: (1) participation, and legitimacy to participate in a partnership; (2) personalisation and consultation with children, young people and their families in designing and delivering services; (3) respectful communication, and feeling that involvement is valued; (4) preparation to be an effective member of a partnership; and finally (5) working across professional and organisational boundaries.

Participation, and legitimacy to participate in partnership working was a theme which supports previous literature (Janssen et al., 2020; Sørensen and Torfing, 2011). This is in line with past reviews on effective partnerships that have found that a collaborative attitude, or willingness to help and see others’ work in the partnership as a joint responsibility, facilitates effective partnership, and reduces resistance to changes in organisational practices (Janssen et al., 2020; Sørensen and Torfing, 2011).

The second ingredient identified for effective partnership working was personalisation and consultation with CYP with SEND and their families. This supports previous review findings that the more involved professionals are, the less resistant to change they will be, resulting in better coordinated services, more tailored to the users’ needs (Sørensen and Torfing, 2011). We build on past research findings that through working with those from the community, professionals can better learn to more effectively collaborate with those both inside and outside their own organisation (Geesa et al., 2022).

A third key ingredient of partnership identified was respectful communication, and all partners feeling valued. This echoes findings of past reviews that respect for collaborators, their roles and task distribution, and “each other’s values related to the patients’ outcome” were qualities that promoted collaboration (Janssen et al., 2020). Our review adds to the evidence base which shows that that clear communication “without condescension” promotes partnership (Janssen et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2018), and that when different partners are viewed as contributing unequally, this is a barrier to collaboration (Zamboni et al., 2020; Alexopoulou-Giannopoulou et al., 2015).

Respectful communication also fed into preparation to be an effective member of a partnership. If poor communication led to resultant problems that subsequently needed addressing, the time and energy that was wasted in “fire-fighting” often meant that individuals had little time to do more than necessary duties, and so could not invest time in preparing for, or developing their, partnership (Johnson et al., 2018). This adds to previous work which highlighted the importance of clear processes and communication, in improving teamwork and collaboration (Geesa et al., 2022; Wranik et al., 2019; Wathne et al., 1996).

Participation, and legitimacy to participate had overlap with working across boundaries, as the way leaders managed people and relationships, processes, and demonstrated leadership at an organisational level and beyond, could facilitate an environment where collaboration is valued and promoted (Janssen et al., 2020). This supports the ideas that those in “siloed” teams (i.e., teams that work in isolation, and do not engage with other teams) were less likely to share knowledge with other teams or departments, or engage in collaborative behaviour, such as establishing partnerships (Janssen et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2018; Alexopoulou-Giannopoulou et al., 2015). Previous research has shown that clear roles, responsibilities and division of tasks aid multidisciplinary working (Janssen et al., 2020; Wranik et al., 2019; Alderson et al., 2022), whilst ambiguous roles and responsibilities have been found to be a barrier (Hysong et al., 2011).

We ensured credibility of our findings through engaging multiple reviewers during article screening, selection, and data extraction processes. Such strategies serve to enhance confidence that our findings are not based on any single reviewer’s particular viewpoints but clearly derived from the data. We still gathered feedback and insights from PPIE, though not as planned in the protocol (Tyldesley-Marshall et al., 2023), and our findings were discussed with the wider RISE Partnership prior to writing up the final report. In addition, we were able to gain professional stakeholder feedback through our collaborative approach with the RISE partnership, in addition to drawing on insights from a project-wide advisory group (consisting of academic experts).

We recognise the review had some limitations. The outstanding limiting feature was the large heterogeneity found across studies in terms of methodology, and results, regarding study populations, SEND services, interventions, and outcomes. A second limitation linked to the heterogeneous nature of the review results, is that methods of reporting the included studies varied and were inconsistent. This review only included studies from the UK and its constituent nations, thus, the results may not be transferable to other contexts, and lower- and middle-income countries in particular. Conceptual findings about partnership are potentially generalisable to other countries, although the data was limited to UK-based studies. Further research is needed to determine the generalisability of these findings to other contexts, particularly comparative analyses involving international frameworks. Furthermore, there were difficulties in locating, and synthesising relevant literature due to the broad nature of the topic. It is well recognised that the definition of SEND is still “broad and still difficult to narrow down” (Hassani and Schwab, 2021; p. 15). However, consulting those with expertise in the area, and a wider consultation with the wider RISE Partnership, a call for evidence—was undertaken to identify studies that would otherwise be hard to find.

Despite these limitations, the review adopted a rigorous method and reporting standards using PRISMA (Page et al., 2021). While the present review confirms results of many previous systematic reviews exploring effective collaboration and partnership working, this review has also highlighted more nuanced factors relating to partnership in how they interrelate with each other, and how they interact throughout the lifecycle of the partnership.

While our review highlights the importance of flexibility of services to adapt to the users’ needs, this goal is not always congruent with traditional evaluations, or scientifically robust interventions with protocols requiring strict adherence, or cost and time limitations. This is not, however, an intractable problem. An evaluation could be designed that recognises and assesses the ability of intervention delivery to adapt to the context/setting and/or CYP, rather than identifying this as a detractor. For example, a recent scoping review of the public health intervention evaluation tool, RE-Aim (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance; Hodgson et al., 2023) found this tool has been applied as a planning and evaluation framework in real world settings (both clinical and community). This may be worth considering for interventions that involve partnerships with multiple health, care, and or education providers.

While organisations that deliver services for CYP with SEND have developed flexibly to serve the needs of their local populations, more consistency in roles and training may lead to more consistent provision across regions, and improve services by reducing waiting times, for example. Evaluations could include experience, effectiveness, implementation, and cost-effectiveness endpoints, and use reporting standards, such as the TIDIER framework to ensure that a flexible SEND service delivery is feasible, and effective, prior to it being rolled out as an accepted service model (Hoffmann et al., 2014). An agreed, standardised group of outcomes which are assessed in a study, such as a Core Outcome Set (Webbe et al., 2018) could be considered for SEND and developed with input from CYP and families. Comparison between interventions with the same aim, and replication studies, would become easier, but more importantly, lessons learnt could be more easily and widely applied to other services in the public sector.

This paper has explored effective partnerships within, as well as across, the sectors of health, social care, and education for services for CYP with SEND. Five key ingredients to effective partnership were identified and an underpinning matrix demonstrates how the ingredients for partnership can be organised across two intersecting continuums. The findings of this review have the potential to offer a valuable contribution to commissioners of, professionals in, and policymakers for, services to CYP with SEND. The findings may help to improve early stages of development and implementation or partnership work in this sector and inform the refinement of existing services, thereby leading to improved services and service outcomes for CYP with SEND in the UK.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

NT-M: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RJ: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. IG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AM: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Y-FC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) West Midlands (NIHR200165); Department for Education (awarded 01/04/22), NIHR Advanced Fellowship (reference AF300060); and the NIHR Technology Assessment Reports programme (reference NIHR131964).

We would like to thank Richard Hastings, Centre for Research in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, University of Warwick for their advice on SEND provision, and Sarah Abrahamson and Pearl Pawson, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick for their project management and administrative support. We would like to thank the RISE partnership for their feedback on findings from the initial scoping searches, which was utilised to inform the review questions and scope.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Education, or the NIHR.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1513668/full#supplementary-material

CYP, Children and young people; DfE, Department for Education; DfES, Department for Education and Skills; DHSC, Department of Health and Social Care; LA, Local authority; MeSH, Medical subject headings; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; NIHR, National Institute for Health and Care Research; PEEP, Peers early education partnership; RISE, Research and Improvement for SEND Excellence (RISE partnership); SEND, Special educational needs and disabilities; SLCN, Speech language and communication needs; UK, United Kingdom.

1. ^https://translate.google.co.uk

2. ^https://www.nihr.ac.uk/patient-and-public-involvement-and-engagement-resource-pack

Alderson, H., Mayrhofer, A., Smart, D., Muir, C., and McGovern, R. (2022). An innovative approach to delivering a family-based intervention to address parental alcohol misuse: qualitative findings from a pilot project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8086. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138086

Alexopoulou-Giannopoulou, E., Panagiotis, M., Athina, A.-B., and Georgios, V. (2015). Conflict management in operating room. Rostrum Asclepius/Vima tou Asklipiou 14, 323–344.

Barlow, J., and Coe, C. (2013). Integrating partner professionals. The early explorers project: peers early education partnership and the health visiting service. Child Care Health Dev. 39, 36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01341.x

Bharatan, I., Logan, K., Manning, R. M., and Swan, J. (2023). Values alignment in sustaining healthcare innovation processes. Shaping high quality, affordable and equitable healthcare: Meaningful innovation and system transformation. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 315–338.

Booth, A., Sutton, A., Clowes, M., and Martyn-St-James, M. (2022). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 3rd Edn. London: Sage.

Castro, S., and Palikara, O. (2016). Mind the gap: the new special educational needs and disability legislation in England. Front. Educ. 1:00004. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2016.00004

Castro-Kemp, S., and Samuels, A. (2022). Working together: a review of cross-sector collaborative practices in provision for children with special educational needs and disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 120:104127. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104127

Chahley, E. R., Reel, R. M., and Taylor, S. (2021). The lived experience of healthcare professionals working frontline during the 2003 SARS epidemic, 2009 H1N1 pandemic, 2012 MERS outbreak, and 2014 EVD epidemic: a qualitative systematic review. SSM Qual. Res. Health 1:100026. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2021.100026

DfE (2022). High needs budgets: effective management in local authorities: research report June 2022: Gray, P., Richardson, P., and Tanton, P.: Strategic services for children and young people (RR1238): Department for Education. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/high-needs-budgets-effective-management-in-local-authorities (Accessed March 15, 2023).

DfE, DHSC (2015). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. 14 March 2023.

DfE, DHSC (2022). SEND review: Right support, right place, right time: Government consultation on the SEND and alternative provision system in England. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/send-review-right-support-right-place-right-time (Accessed March 15, 2023).

DfES (2003). “Every child matters” in Department for Education and skills (London: Department for Education and Skills).

Geesa, R. L., Mayes, R. D., Lowery, K. P., Quick, M. M., Boyland, L. G., Kim, J., et al. (2022). Increasing partnerships in educational leadership and school counseling: a framework for collaborative school principal and school counselor preparation and support. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 25, 876–899. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2020.1787525

Gibson, B. E., Hamdani, Y., Mistry, B., and Kawamura, A. (2023). Tinkering with responsive caring in disabled children's healthcare: implications for training and practice. SSM Qual. Res. Health 3:100286. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100286

Google (2006). Google translate. Available at: https://translate.google.co.uk (Accessed October 27, 2023).

Green, L. L., and Dicks, J. (2012). Being there for each other – who fills the gaps? A case of a young person with a neurological disability by a children's social worker and a case manager. Soc. Care Neurodis. 3, 5–13. doi: 10.1108/20420911211207017

Greenhalgh, T., and Papoutsi, C. (2018). Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 16:95. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4

Hassani, S., and Schwab, S. (2021). Social-emotional learning interventions for students with special educational needs: a systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 6:6. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.808566

Higgins, J, Thomas, J, Chandler, J, Cumpston, M, Li, T, Page, M, et al. (2022). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 6.3. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (Accessed October 12, 2020).

Hodgson, W., Kirk, A., Lennon, M., Janssen, X., Russell, E., Wani, C., et al. (2023). RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance) evaluation of the use of activity trackers in the clinical Care of Adults Diagnosed with a chronic disease: integrative systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 25:e44919. doi: 10.2196/44919

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., et al. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., et al. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 34, 285–291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

Hysong, S. J., Esquivel, A., Sittig, D. F., Paul, L. A., Espadas, D., Singh, S., et al. (2011). Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: a qualitative analysis. Implement. Sci. 6:84. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-84

Janssen, M., Sagasser, M. H., Fluit, C. R. M. G., Assendelft, W. J. J., de Graaf, J., and Scherpbier, N. D. (2020). Competencies to promote collaboration between primary and secondary care doctors: an integrative review. BMC Fam. Pract. 21:179. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01234-6

Johnson, R., Grove, A., and Clarke, A. (2018). It’s hard to play ball: a qualitative study of knowledge exchange and silo effects in public health. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18:1. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2770-6

Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., and Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evid. Implement. 13, 179–187. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

Lynch, A., Alderson, H., Kerridge, G., Johnson, R., McGovern, R., Newlands, F., et al. (2021). An inter-disciplinary perspective on evaluation of innovation to support care leavers’ transition. J. Child. Serv. 16, 214–232. doi: 10.1108/JCS-12-2020-0082

McKean, C., Law, J., Laing, K., Cockerill, M., Allon-Smith, J., McCartney, E., et al. (2017). A qualitative case study in the social capital of co-professional collaborative co-practice for children with speech, language and communication needs. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 52, 514–527. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12296

NICE (2022). Disabled children and young people up to 25 with severe complex needs: integrated service delivery and organisation across health, social care and education. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Contract No.: NG213.

NIHR: Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (2022). Patient and public involvement and engagement resource pack.

Noyes, J., Booth, A., Flemming, K., Garside, R., Harden, A., Lewin, S., et al. (2018). Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series-paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 97, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020

Odukoya, O. O., Jeet, G., Adebusoye, B., Idowu, O., Ogunsola, F. T., and Okuyemi, K. S. (2022). Targeted faith-based and faith-placed interventions for noncommunicable disease prevention and control in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 11:119. doi: 10.1186/s13643-022-01981-w

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n160-n. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Palikara, O., Castro, S., Gaona, C., and Eirinaki, V. (2019). Professionals’ views on the new policy for special educational needs in England: ideology versus implementation. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 83–97. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1451310

Popay, J, Roberts, H, Sowden, A, Petticrew, M, Arai, L, Rodgers, M, et al. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC methods Programme Lancaster University. 15 March 2023.

Rix, J., Sheehy, K., Fletcher-Campbell, F., Crisp, M., and Harper, A. (2013). Exploring provision for children identified with special educational needs: an international review of policy and practice. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 28, 375–391. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2013.812403

Rosen, C., Miller, A. C., Pit-ten Cate, I. M., Bicchieri, S., Gordon, R. M., and Daniele, R. (1998). Team approaches to treating children with disabilities: a comparison. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 79, 430–434. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90145-9

Sørensen, E., and Torfing, J. (2011). Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Adm. Soc. 43, 842–868. doi: 10.1177/0095399711418768

Thomas, J., and Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tyldesley-Marshall, N., Parr, J., Brown, A., Chen, Y.-F., and Grove, A. (2023). Effective service provision and partnerships in service providers for children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities: a mixed methods systematic review protocol. Front. Educ. 8:8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1124658

Tyldesley-Marshall, N., Parr, J., Brown, A., Ghosh, I., Mehrabian, A., Chen, Y.-F., et al. (2024). Effective service provision and partnerships in service providers for children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND): A mixed methods systematic review. Warwick evidence. A report commissioned by the National Children’s bureau on behalf of the RISE partnership. London: The RISE Partnership Trust.

Wathne, K., Roos, J., and von Krogh, G. (eds). (1996). “Towards a theory of knowledge transfer in a cooperative context” in Managing knowledge: Perspectives on cooperation and competition (London: SAGE Publications Ltd), 55–81.

Webbe, J., Sinha, I., and Gale, C. (2018). Core outcome sets. Arch. Dis. Childh. Educ. Pract. 103, 163–166. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312117

Wood, P., and Bates, S. (2020). National and international approaches to special education needs and disability provision. Education 48, 255–257. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2019.1664395

Wranik, W. D., Price, S., Haydt, S. M., Edwards, J., Hatfield, K., Weir, J., et al. (2019). Implications of interprofessional primary care team characteristics for health services and patient health outcomes: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Health Policy 123, 550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.03.015

Keywords: children and young people, collaboration, joined-up working, disabilities, partnership, service improvement, service provision, special educational needs

Citation: Tyldesley-Marshall N, Johnson R, Parr J, Brown A, Ghosh I, Mehrabian A, Chen Y-F and Grove A (2025) Improving partnerships to improve outcomes for children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities: qualitative findings from a mixed methods systematic review. Front. Educ. 10:1513668. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1513668

Received: 18 October 2024; Accepted: 07 February 2025;

Published: 19 February 2025.

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Maurice H. T. Ling, University of Newcastle, SingaporeCopyright © 2025 Tyldesley-Marshall, Johnson, Parr, Brown, Ghosh, Mehrabian, Chen and Grove. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amy Grove, YS5sLmdyb3ZlQGJoYW0uYWMudWs=

†Present address: Natalie Tyldesley-Marshall, Janette Parr, Anna Brown, Iman Ghosh, Amin Mehrabian, Yen-Fu Chen and Amy Grove: Birmingham Centre for Evidence and Implementation Science, School of Social Policy and Society, Birmingham, United Kingdom

‡ORCID: Rebecca Johnson, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2847-8298

Amin Mehrabian, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8879-7565

Iman Ghosh, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7073-7468

Amy Grove, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8027-7274

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.