94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 05 February 2025

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1512667

Previous studies on blended learning in Chinese universities focused on improving language training. However, higher education should also address key competencies and moral education. Therefore, this study constructed a blended learning mode in English Viewing, Listening and Speaking Course based on the Production-Oriented Approach, aiming at solving the traditional drawbacks of language training in this course and implementing cultivation of key competencies, values, and attitudes at the same time. 40 students were invited to participate in the practice of this mode. A pre-test and a post test, students’ productive performance, questionnaires, and teacher’s observation were used to evaluate the effectiveness of this mode. The results showed that this mode could effectively implement both language education and the cultivation of virtues and other key competencies.

The COVID-19 outbreak has accelerated the push for blended teaching in universities worldwide. Study at home has been normalized. Higher education institutions have had to change from traditional face-to-face teaching models to online teaching. As the pandemic has been successfully under control, universities are gradually returning to normal teaching in the post-pandemic era.

Scholars are concerned about the impact of COVID-19 on education, especially the teaching modes and the role of online teaching in the post-pandemic era. Some argued that the pandemic demonstrated the enormous potential of online education to differentiate itself from traditional models (Wang, 2020). Since the pandemic, online education has not only taken on the burden of international education and withstood various tests, but has also developed habits of mind, technology, and even emotional identity for online education (Liu et al., 2021a; Liu et al., 2021b). However, some studies have argued that online education was only a complementary form of educational internationalization during the pandemic, and that it could neither fully resolve the internationalization crisis caused by the pandemic (Liu et al., 2020), nor replace face-to-face teaching (Zhou, 2020). Although the importance of online education has increased since the pandemic was brought under control, it could only be used as a complementary means to offline education (Liu et al., 2021b).

In other words, whether online education can become a mainstream trend in technological innovation for digital internationalization remains controversial. Professor Ulrich Teichler, an international renowned expert in higher education, actively advocated that in the post-epidemic era, it might be an opportunity to move toward a more creative mix of modes of teaching and learning for all institutions of higher education in the world (Pan et al., 2020). Therefore, many colleges and universities have chosen to facilitate blended learning so that the advantages of both offline and online education can be combined.

As for foreign language courses in China, blended learning is not something new. According to Hu and Hu (2020), the development of foreign language education informatization in China can be divided into three phases: the phase of foreign language e-learning (1949–1997), the phase of computer network-assisted teaching (1998–2011), and the phase of in-depth integration of information technology and foreign language education (2012–2019). The third phase can be divided into the “Internet + foreign language education” period and the “Artificial Intelligence + foreign language education” period.

The advent of the “Internet + higher education” era has promoted the application of blended teaching of English in universities (Liang et al., 2022). Before the outbreak of the epidemic in 2020, many studies had been conducted on theoretical and practical exploration of online and offline hybrid teaching of English in China. In particular, the number of relevant research publications increased dramatically in 2016–2018. Many English blended teaching research results and national quality courses were launched during this period. The research topics range from the exploration of the application of blended teaching models in university English, to the construction of blended teaching models based on various platforms and different courses, and to the analysis of factors related to blended teaching models in university English (Liang et al., 2022). The goal is to sharpen students’ language skills.

Undoubtedly, the post-pandemic era will witness further improvement of blended teaching in foreign language courses in China. However, the fundamental aim of education is to cultivate talents with virtue. Foreign language learning should not be limited to the cultivation of foreign language skills, but should also focus on the guidance of correct values and the development of other competences. Moreover, the epidemic has a great impact on the cognition of university students. Students have gained a deeper understanding of teamwork, dedication, sustainable development and so on. Therefore, it is a good opportunity to carry out such a teaching reform in the post-epidemic era.

English Viewing, Listening and Speaking Course is a basic course for English majors in our university with the purpose of sharpening students’ listening and speaking skills. However, traditional teaching emphasizes listening and neglects speaking due to limited time in class, and learning and using are separated. Instead of only targeting at language training, this research tried to construct a blended learning mode in this course based on the Production-Oriented Approach (POA) to solve the traditional drawbacks of language training in this course as well as cultivate virtues and other key competences in 21st century.

POA is a theory of foreign language education with Chinese features. It has been developed over the last decade by Professor Wen Qiufang, a distinguished researcher in China, and other scholars with the aim of overcoming the weaknesses in English instruction in higher education in China.

To be more specific, the first problem POA aims to solve is input–output separation (Wen, 2020a, p. 28). The pedagogical methods used in mainstream education in China are characterized as being text-centered and input-based (Wen, 2018a). Teachers adopt either bottom-up instruction or top-down instruction. Both, however, separate learning from using language. Other English teachers conduct task-based or project-based approaches, which emphasize using English but pay insufficient attention to learning new linguistic forms and lack teachers’ systematic guidance in students’ production.

The second weakness of current English education in China is the separation of language training and personality shaping (Wen, 2020a, p. 28). “Wen Yi Zai Dao (Literature is the vehicle of ideas and ethics)” is a key concept in Chinese culture. This term is a Confucian statement about the relationship between literature and ideas (Wen, 2020a, p. 32).

In the past, we mostly taught foreign languages as pure language tools. However, 4 years of university is a critical period for students to form their world outlook, outlook on life and values. The main channel for students to receive higher education is the study of various courses. If our teaching only emphasizes the law of language itself and the training of language skills, without considering the all-round development of college students, such foreign language teaching cannot be regarded as foreign language education, or at best, it can only be equated with the skills training of language training institutions, and foreign language teachers cannot be regarded as workers engaged in higher education, but only general language skills trainers (Wen, 2020a, pp. 33–34). Therefore, POA emphasizes the leading role of teachers. Such a leading role is not only reflected in the cultivation of students’ foreign language application ability, but also in the cultivation of students’ correct outlook on life, world outlook and values.

By integrating the strengths of Western instructional approaches with Chinese contextual features, POA provides a brand-new mode of foreign language teaching. After long-term practice, a relatively mature POA theoretical system has been formed by Professor Wen’s POA research group, as is shown in Figure 1 (Wen, 2018b).

Figure 1. The newly-revised system of POA (Wen, 2018b).

POA consists of three components: teaching principles, teaching hypotheses, and teacher-guided teaching procedures. The teaching principles include learning-centered, learning-using integration, cultural exchange, and key competencies. Learning-centeredness means that in classroom instruction, with limited classroom time, instructors must employ all possible means to make full use of every minute of teaching so that students can engage in learning. The learning-centered principle focuses on activating processes of learning rather than on the learner as a person, thereby challenging the learner-centered principle, which marginalizes the role of the teacher to that of a facilitator, consultant and helper and downplays the teacher’s professional function as a designer, organizer, and director of language instruction (Wen, 2018a). Different from learner-centeredness, POA puts “achieving teaching objectives and promoting effective learning” in the first place, and carries out teaching activities in a planned, organized, and leading manner. POA believes that although students are the main body of learning activities and teachers cannot replace students’ learning, teachers should play a leading role in the whole teaching process and use their professional knowledge to guide students to learn (Deng, 2018). Learning-using integration principle maintains that learning and using language must be integrally joined (Wen, 2018a). “Cultural exchange principle” requires that the teaching content should comply with the concept of cultural exchange and mutual learning and advocate that different ethnic groups respect each other’s culture, learn from each other’s cultural essence, and oppose cultural hegemony and cultural discrimination. “Key competencies” consists of six key competencies in foreign language education, namely language competency, learning competency, critical thinking competency, cultural competency, creative competency, and collaborative competency.

Teaching hypotheses comprise output-driven, input-enabled, selective learning, and assessment being learning. The teaching processes include three phases: motivating, enabling, and assessing. Each phase is teacher-led by guiding, designing, or scaffolding. In the phase of motivating, teachers explicitly describe relevant communicative scenarios which students may have not experienced but may perceive as possible occurrence. The designed tasks which students are required to try out are challenging so that students are motivated to fill the gap between their prior knowledge and the knowledge needed to accomplish the designed tasks. In the phase of enabling, teachers use receptive skills as enablers and divide the output task into subtasks. Students carry on selective learning to acquire the content, language forms and discourse structure needed to complete the output tasks while teachers provide instructions. In the last phase, teacher-student collaborative assessment (hereafter TSCA) is conducted to assess students’ production. Many studies have investigated or compared the effectiveness of different forms of assessment, such as teacher assessment, self-assessment, peer assessment, and computer-mediated assessment (Han and Hyland, 2016; Lundstrom and Baker, 2009; Suzuki, 2008; Yang et al., 2006). However, few studies have looked at the integration of these forms into one holistic assessment to maximize effectiveness. TSCA was proposed in 2016 by Wen (2016) to address the challenges of responding to students’ production, that is, low efficiency and poor effectiveness (Sun, 2020a). TSCA encompasses all classroom-based activities taken by students under the teacher’s guidance to evaluate their learning output, providing an opportunity for further learning. It organizes and balances the aforesaid four assessments in L2 classrooms, shedding light on how assessment can be an integral part of teaching to enhance learning (Sun, 2020a).

Since 2008, Professor Wen and her research group have published many research articles concerning POA and an increasing number of foreign language teachers in China have put this new approach into practice. Relevant POA-based language teaching and learning research can be divided into the following four aspects: (1) The teaching procedures of POA, namely, motivating (Zhang, 2020; Yang, 2015; Wen and Sun, 2020), enabling (Qiu, 2017, 2019, 2020a), and assessing (Sun, 2017, 2020a); (2) The application of POA to foreign language courses such as College English (Qiu, 2020a; Zhang, 2020; Zhang, 2021), Academic English Writing (Chen and Wen, 2020), Comprehensive English (Sun, 2020b), and Business English Negotiation Course (Nie et al., 2023); (3) The POA and teacher development (Qiu, 2020b; Sun, 2020c; Wen, 2020b; Zhang, 2020); (4) teaching materials (Bi, 2019; Chang, 2017).

The existing findings have shown the feasibility and effectiveness of the POA for foreign language teaching and learning in tertiary education. For example, the teaching effectiveness of the motivating practice was appraised by both the teacher’s and students’ retrospective evaluations in a dialectal research carried out by Zhang (2020). As for the phase of enabling, Qiu (2020c) evaluated the actual effectiveness of the enabling implemented through interviews of the class observer and participants and the analysis of student productive performance. Interview data showed that the class observer and participating students responded positively toward the enabling activities, and the analysis of student writing performance revealed that enabling the POA instruction resulted in diverse structure, flexible use of language resources, and rich content. As for assessing, recent studies have shown that TSCA helps students revise their written work, enhance their assessment cognition and build a supportive dynamic learning atmosphere where they serve as “scaffolds” for each other (Sun, 2017; Sun and Wen, 2018).

As for the integration of the POA and moral education, the relevant researches are quite limited. Wang and Lu (2024) explored the rationale behind the integration of POA into moral education through college foreign language teaching, put forward five principles that guide the teaching design of such integration and provided a step-by-step demonstration of how to design a teaching plan in college comprehensive English class. Zhang (2022) took the “English Teaching and Research Course” as an example and elaborated on the cultivation of morality in terms of talent cultivation, approaches, the sources of the materials, the theoretical basis, the methods for implementation, and specific steps. However, both researches did not provide any data to test the effectiveness of their teaching. Liu (2023) proposed to construct a teaching path in translation course for English majors’ moral education based on the POA. This study proved the effectiveness in moral education and but did not prove its effectiveness in language teaching. Wang (2021) focused on English writing course and proved the effectiveness in language teaching and moral education by questionnaires and interviews, but no pre-test and post-test data was provided.

Overall, existing research has not explored the integration of POA and moral education in English listening and speaking courses, nor has it simultaneously tested the effectiveness of the teaching model in improving both language skills and moral education. Moral education should be subtly integrated into language teaching, rather than being the sole focus of the language classroom. Therefore, it is necessary to demonstrate that the teaching model can effectively enhance both language skills and cultivate other competencies and virtues.

We conducted the blended learning reform in an experimental class in our university. English Viewing, Listening and Speaking Course is a basic course for the 1st and 2nd grade English majors. Given that the POA is more suitable for learners with good language proficiency (Li, 2017), sophomores, rather than freshmen, were selected as the participants. In addition, only the participants whose grade point average (GPA) was 3.00 out of 4.00 or higher took part in this study. Their English level corresponds to CSE 4 (China Standards of English). Forty sophomores, 4 male and 36 female, who met the above requirement and showed willingness to experience this new learning mode were invited to participate in this study. Their mean age was 20 years and they were skilled at using digital technology to communicate or study via the online learning platforms. What’s more, to avoid the subjectivity of the author, two experts were invited to mark students’ initial and subsequent productions. Both were experienced English teachers with applied linguistics research background and language evaluation ability.

English Viewing, Listening and Speaking Course is a basic course for English majors in our university with the purpose of sharpening students’ listening and speaking skills. Under the guidance of the POA, speaking task can be used as the drive and listening activity can be used as the enabler. The POA-based English Viewing, Listening and Speaking blended learning mode is output-driven and input-enabled with the help of multiple teaching channels. The teaching mode is shown in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 2, motivating and assessing are carried out online, while enabling is carried out both online and offline. The reason for allocating the two offline class hours to the enabling phase is that the enabling activities directly affect whether students can complete the subsequent productive tasks. Offline sessions are more conducive to face-to-face communication between teachers and students, allowing teachers to better play their guiding role throughout the enabling phase, whether in guiding listening and speaking skills or cultivating other competencies and virtues.

In the motivating phase, the teacher uses online learning platforms to describe relevant communicative scenarios either via micro-lectures, videos, or documents. Students try out the required productive activity online for the first time to become aware of their problems in accomplishing the activity and be motivated to overcome these deficiencies. The teacher then explains the learning objectives of a certain unit and describes types of tasks and specific requirements via online platforms. Since the enabling process is mainly achieved by listening and students are expected to acquire basic listening skills and strategies in their first two grades, the enabling process is also designed as a process of acquiring listening skills and strategies. Flipped classroom method is adopted for this purpose. In the first part of enabling, i.e., the online enabling before class, teachers use micro-lectures or MOOC to introduce new listening skills to students. Students finish some online tasks before class. The second part of enabling takes offline during class and the third part of enabling takes online after class. The whole enabling phase serves as not only the practice of the newly-learnt listening skills but also the enabling activities for the motivating task. Students conduct selective learning of input materials and finish subtasks, while the teacher offers guidance and supervision. At last, in the assessing phase, students submit the subsequent productions and TSCA is conducted online. Moral education is implicitly integrated with language training in this mode. While sharpening listening and speaking skills, students also cultivate core competences and virtues which are vital for them in the 21st century.

The study took Unit 6 Embrace the Unknown from the textbook Over to You Viewing, Listening and Speaking Book II as the teaching topic to perform the above blended learning mode. The reasons for choosing this topic were: (1) This topic was intriguing to college students who were full of curiosity; (2) Talking about the unknown was a challenging task, which coincided with the requirement of the POA’s motivating scenario; (3) Questioning claims, one of the learning objectives in this unit, related to critical competency in the POA; (4) The story of Zheng He in this unit could be used to integrate language training with personality shaping, which made this POA-based blended learning reform special.

The teaching objectives covered two levels: language and skills. As for language, students were expected to tell the story of Zheng He, a great Chinese explorer, as well as the Chinese culture embodied in the story, and be able to organize listening notes. As for skills, three key competencies would be cultivated. First, critical thinking competency: to enable students to question claims. Second, collaborative competency: to enable students to communicate effectively with teammates. Third, intercultural competency: to familiarize them with the Chinese cultural concepts “harmony without uniformity” and “amity and good neighborliness” and strengthen the awareness of mutual learning among civilizations.

The teaching of this unit lasted 2 weeks with 2 offline class hours. Figure 3 shows the timeline of the teaching procedures. On the first and second days, students completed the motivating task on the online platform. Based on the students’ difficulties in output, the teacher posted before-class enabling online activities on the third day. Students had 3 days to complete the before-class online tasks, including learning new listening skill and practicing basic listening exercises. On the seventh day, there was an offline flipped classroom, where the teacher provided face-to-face guidance. From the eighth to the eleventh day, students continued to complete the enabling activities online. The after-class facilitation activities aimed to further consolidate the listening skills students had learned, while also offering additional support in language, content, or discourse structure to address students’ productive difficulties. The final 3 days were for online assessing, where students submitted their final output, and the teacher led a teacher-student collaborative assessment.

Three phases of the POA, namely motivating, enabling, and assessing, were illustrated as follows.

Different from warm-up or lead-in in traditional classrooms, motivating in POA presents a challenging task for students, requiring more than existing knowledge to complete, so as to stimulate students’ hunger for knowledge. There are three basic principles to evaluate the effectiveness of motivating design: authentic communication, cognitive challenge, and appropriate production objectives (Wen, 2018b). As shown in Figure 4, the three criteria match the three steps of motivating correspondingly (Zhang, 2020).

The four elements in the productive scenario (see Appendix I), namely, topic, purpose, identity, and setting, were quite clear. The topic was “embrace the unknown.” The purpose was to show the world the Chinese spirit of exploration as well as Chinese culture embodied in the story. The identity was representatives of China, and the setting was Youth Power, a real formal program. The productive task could not only expand students’ knowledge about Zheng He’s story as well as Chinese culture but also enhance their critical thinking skills. The identity of representatives of China gave students a sense of mission so that the scenario could successfully inspire students to learn. The productive objective could be achieved with moderate difficulty and within controllable time and could be divided into a series of logically connected sub-objectives as illustrated in the following part. Therefore, the scenario met the three criteria, namely, authentic communication, cognitive challenge, and appropriate productive objectives.

Students’ initial production showed that their main difficulty lied in content. To be more specific, their stories about Zheng He were too simple, failing to provide enough details to demonstrate the feat of Zheng He’s voyages to the West. What’s more, the exploration of the Chinese culture embodied was also insufficient. Therefore, the enabling stage mainly focused on enriching the content of their speeches.

In response to students’ output difficulties, the teacher guided students through an inquiry-based learning process. Rather than directly telling students the problem of their initial production, the teacher designed a series of activities that would gradually lead students to discover problems, think about them and solve them. These activities were designed in accordance with the POA principles of alignment, gradualness, and variety, and incorporated the training of listening skill, critical thinking, and intercultural competencies. Critical thinking competency was used to add depth to intercultural competency and intercultural competence adds breadth to critical thinking competency. Language skills were enhanced by both intercultural and critical thinking competencies. In this way, moral education was naturally achieved.

Enabling activities were be divided into three stages, before class, during class, and after class. Among them, before-class and after-class activities were conducted online, while during class offline. Guided by POA’s criteria, activities before, during, and after class were woven together by five mind maps, labeled as Mind Map A, B, C, D, and E. Mind mapping not only served as a practical way to practice the skill of organizing listening notes, but also provided a clear outlining for ideas that students would use to build their speeches. Figures 5–7 respectively present the design of before-class, during-class, and after-class enabling activities (Detailed explanation of enabling activities can be seen in Appendix I).

Being the last phase of the POA, assessing includes ongoing response given to students upon their completion of tasks in the enabling phase and “delayed” response to their after-class output. TSCA is specifically used in this delayed assessment (Sun, 2020a).

The traditional TSCA skeleton framework formulated three separate phases: pre-class, in-class, and post-class (Sun, 2020a). In our blended learning mode, the assessing phase was conducted completely online. Therefore, the framework was redesigned, as shown in Figure 8. The specific assessment process presented in Figure 8 can be seen in Appendix I.

After the students have submitted their second output, the teacher organized online collaborative teacher-student assessment guided by four concepts in the POA: (1) assessment is a sublimation of teaching and learning; (2) assessment requires professional leadership from the teacher; (3) assessment requires multiple forms of participation from all students; and (4) assessment requires the teacher to play a leading role.

The gradual development of language brings difficulties to the evaluation of teaching effect. The improvement of language proficiency is a gradual and slow process. The teaching of a unit is of limited help to the overall language proficiency, and it is difficult to trigger lasting language improvement or learning transfer. Even if it can play a role, it may not be captured by the detection index as an explicit representation. Therefore, the evaluation of POA-based teaching is based on the “present” perspective of the classroom. Researchers can examine explicit classroom performance, student gains, and production quality (Qiu, 2020a, pp. 66–67).

Therefore, there are three indicators to evaluate the effectiveness of POA-based teaching: “engagement,” which refers to the degree of students’ attention and participation in class; “sense of gain,” which refers to whether students feel that they have achieved something in class, and “production quality,” which refers to the objective evaluation of students’ output performance (Wen, 2017). These three indicators cover the three dimensions of student behavior, cognition, and performance. The first one focuses on the learning process, and the latter two focus on the learning results (Bi, 2017).

Accordingly, evaluating the effectiveness of teaching and learning facilitated by the POA required a combination of questionnaires, teacher’s observation, and output texts to assess students’ engagement, sense of gain and production quality. Teacher’s observation was adopted to assess students’ engagement, questionnaires were employed to know about students’ sense of gain, and output texts were analyzed to assess production quality. What’s more, since this course is mainly targeted at improving students’ speaking and listening ability and the improvement of students’ speaking ability could be tested by the initial and subsequent productive performance in the POA, a pre-test and a post-test were complemented to test whether students’ listening skill of organizing notes was sharpened. The quantitative data of the initial and subsequent productive performance, the pre-test and post-test, as well as the questionnaires were analyzed by SPSS 29.

Students’ initial speeches in the motivating stage and the subsequent speeches after the enabling stage were used to test the improvement of students’ oral production. There were 80 speeches in total, with 40 speeches collected in students’ initial and subsequent production. Two experienced experts were invited to evaluate students’ speeches by the scoring rubrics in the assessing phase (See Appendix II). Both experts are experienced English teachers with applied linguistics research background and language evaluation ability. One of them has been teaching English Viewing, Listening, and Speaking Course for 8 years, and the other has been teaching English Public Speaking Course for more than 6 years.

Before the formal evaluation, the two experts randomly selected two from the initial and subsequent speeches, respectively, for pre-evaluation to ensure that the experts had roughly the same understanding of the scoring criteria and the quality of the students’ speeches. After the formal evaluation, the consistency of the scores of the two experts were checked. The results of Spearman correlation analysis showed that the scores were highly consistent (r = 0.983, p < 0.01), and the mean and standard deviation were very close (see Table 1). This shows that the scores of the two experts are consistent, and the scores can reflect the true level of students’ speeches. Students’ scores were the average of the two experts’ scores.

To evaluate whether there was a significant difference between the initial production and subsequent production scores, a series of statistical tests were conducted. First, the normality of the difference scores between the initial production and subsequent production was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The results indicated that the difference scores did not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.05), suggesting that the data violated the assumption of normality (see Table 2).

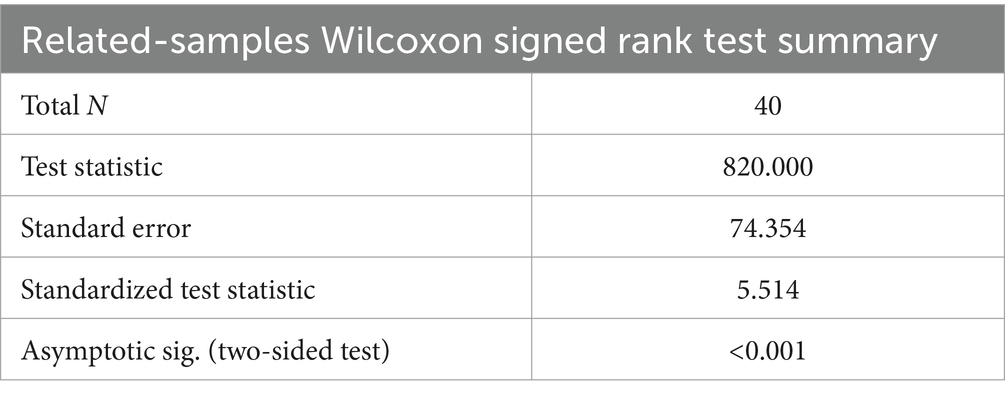

Since the data did not meet the assumption of normality, a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, a non-parametric test, was used to compare the initial production and subsequent production scores. The results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test revealed a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores (Z = 5.514, p < 0.001) (see Tables 3, 4). This indicated that there was a statistically significant change from the initial production to the subsequent production, suggesting that the POA-based blended learning mode was effective in improving students’ oral ability.

Table 4. Wilcoxon signed rank test summary for the initial production and subsequent production scores.

To test students’ improvement in listening, a pre-test and a post-test were conducted, respectively, at the beginning and the end of this unit. Since the learning objective concerning listening in this unit was organizing listening notes, the pre-test and post-test adopted the section of “Talk” in TEM 4 (Test for English Majors Grade Four).

TEM 4 has been implemented by the Chinese Ministry of Education since 1991 to examine English majors in comprehensive universities nationwide. The test covers all aspects of English listening, reading, writing and translation. It is held in June every year for sophomores majoring in English. “Talk” is a section in TEM 4 listening. In this section, students will hear a talk. Students can use a blank sheet for note-taking. Based on the notes, they will fill in the blanks to complete the outline of the talk on Answer Sheet with no more than three words for each blank. The word(s) they fill in should be both grammatically and semantically acceptable. Therefore, the section of “Talk” is appropriate to test students’ ability of organizing listening notes.

Four talks of TEM 4 in the year of 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015 were selected. The pre-test consisted of two talks from 2012 and 2013, and the post-test consisted of the rest two (see Appendix III). Since TEM 4 is reviewed by national experts every year to ensure a balanced level of difficulty, the pre-test and the post-test were basically at the same level of difficulty. The tests were issued by Chaoxing. Platform in class and scored by the platform since this kind of blank-filling task could be automatically marked after the teacher set up the correct answers. Forty students participated in both tests and the results were analyzed by SPSS 29. To assess whether there was a significant difference between pre-test and post-test scores, a series of statistical tests were performed. Initially, the normality of the difference scores between pre-test and post-test was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The results indicated that the difference scores did not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.05), suggesting a violation of the normality assumption (see Table 5).

Given the failure to meet the normality assumption, a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, a non-parametric test, was employed to compare pre-test and post-test scores. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test revealed a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores (Z = 5.527, p < 0.001) (see Tables 6, 7). This result indicated a statistically significant change from pre-test to post-test, suggesting that the POA-based blended learning approach effectively improved students’ listening proficiency.

After the study of the unit, all the 40 students were invited to finish an online questionnaire (See Appendix IV) issued by the teacher. The purpose of the questionnaire was to let students make self-assessment about their achievement in this unit. The questionnaire consisted of five scale items, which measured the attitude of the respondents through the numerical interval of 1–10. Among them, 1 represented strong disagreement and 10 represented strong agreement. The five scale items corresponded to the five teaching objectives of the unit. The first and second items corresponded to language teaching objectives, and the third, fourth and fifth items corresponded to key competencies and moral education objectives. A total of 40 questionnaires were distributed by Wenjuanxing, an online questionnaire tool, and 40 valid questionnaires were returned. The results of the questionnaire were analyzed by SPSS 29, as shown in Table 8.

According to descriptive statistics in Table 8, the mean of Item 1 is 7.22 and that of Item 2 is 7.4, showing that students felt they had achieved a lot regarding listening and speaking abilities. Students’ self-assessment was consistent with the results of the pre- and post-tests as well as the initial and subsequent speeches. Item 3 is related to self-assessment of critical thinking competency and the mean is 7.3. Item 4 is related to self-assessment of communication competency and the mean is 7.7. Item 5 is related to cultural competency and the mean is 7.9, the highest among the five items. Students thought that they made a lot progress in these three competencies, which demonstrated that the POA-based blended learning mode was effective in cultivating students’ key competencies besides learning competency.

The teacher acted as both the lecturer and the observer in class. Offline classroom observation on students’ participation was conducted from three dimensions: “behavioral participation,” “cognitive participation” and “emotional participation” (Qiu, 2020a, p. 112) as shown in Table 9. Furthermore, it is important to note that the teacher had participated in multiple POA teaching research guidance and training sessions. This experience enabled the teacher to comprehensively understand the tasks involved in classroom observation and the requirements for emotional participation. By having this background, the teacher was better equipped to minimize misunderstandings and enhance the reliability of the data collected during the observations.

From the perspective of behavioral participation, students participated in eight teaching steps, which took 54 min. The main training skills were language listening and speaking skills, critical thinking competency, collaborative competency, and intercultural competency. The organizational forms of student participation included class activities, pair activities, group activities and individual activities. The interactive types of participation included teacher-student-teaching material interaction and student–student-teaching material interaction. Behavioral participation reflected comprehensiveness. Students not only participated in language skills training, but also in critical thinking competency, collaborative competency, and intercultural competency training.

From the perspective of cognitive participation, students participated in different cognitive activities in each teaching step. In Activity 1 “Compare Mind Map A and B,” students compared and analyzed two mind maps and reflected on the shortcomings of their initial output. In Activity 2 “Think critically: question claims,” students further questioned the reasonableness of the content in the instructional material. In Activity 3 “Explore for cultural evidence,” students understood Zheng He′s cultural contributions by understanding the video material, and then updated the mind map by using listening skills and the information obtained in the video. In Activity 4 “Understand Chinese cultural concepts embodied in the story of Zheng He,” students first analyzed and summarized the cultural concepts embodied in the story of Zheng He, and then further understood them in the teacher’s teaching. Finally, students updated the mind map again by applying the knowledge they understood. The whole enabling process reflected the development path from understanding to application, and reflected the characteristics of the gradual development of cognitive ability.

From the perspective of emotional participation, student participation reflected a strong interest. Observers understand students’ emotional experience through their expressions and actions. Curiosity was reflected in the exchange of views with neighbors. Staring at the blackboard and the teacher’s presentation showed concentration and interest. Nodding, frequent hand movements and excited expressions during group communication showed their activeness (Table 9).

In traditional English viewing, listening, and speaking courses, speaking activities are often used as lead-in or warming-up before listening, or after-listening activities. In either case, students mainly use prior knowledge to complete oral tasks and the input from listening is not necessarily converted into output in speaking. Students are passive listeners and not sure what language knowledge they are supposed to learn from listening. In other words, learning and using are separated.

Compared to traditional mode, the POA-based blended learning mode uses speaking activities as motivator and listening activities as enabler so that input and output are effectively connected in the teaching procedures. In our experiment, students first realized their difficulties in the motivating oral task. Then, being motivated, they became active learners with clear objectives. They benefited from the ideas, language, or discourse structure of the following listening enabling tasks to overcome the initial difficulties, and finally used the newly learned ideas, language, or discourse structure to produce the oral task for the second time. Learning and using were integrated, contributing to the significant improvement in the subsequent speeches.

Certainly, the realization of integrating listening and speaking is attributed to the POA teaching mode. Traditional offline classrooms can also adopt the POA teaching mode. However, if the three phases—motivating, enabling, and assessing—are all implemented offline, the duration of each unit in the offline teaching process would be significantly extended, resulting in a limited amount of teaching content that can be covered within a semester.

Traditional English viewing, listening, and speaking courses take in the form of offline teaching and learning with 2 class hours per week. The time and energy students devote to this course is limited, which undoubtedly hinders the improvement of their listening and speaking abilities.

In contrast, blended learning makes learning happen inside and outside class. Digital technology allows students to conduct autonomous study before and after class and frees up class time for activities, allowing a deeper exploration of content because new material has already been explored before class (Zibin and Altakhaineh, 2019). In our experiment, the note-taking listening skill was first introduced to students via a micro-course before class, and the practice of this skill spanned pre-class, in-class, and post-class listening activities. Compared to traditional mode, blended learning considerably increases students study time, which is a basic requirement for language learners since sufficient practice is the foundation of everything.

What’s more, students can adopt a more individualized learning style, which is particularly important in the context of listening skills. Due to varying levels of language proficiency, learners have different needs and abilities when it comes to processing listening tasks. For instance, some students with higher language proficiency might be able to comprehend the material after listening just once, grasping the key points and nuances on their first attempt. On the other hand, students with lower proficiency may require additional practice, needing to listen to the same material two or even more times to fully understand it. This personalized approach to listening practice allows each student to progress at their own pace, addressing their specific challenges and strengths. By catering to these individual differences, the learning experience becomes more effective and supportive, ensuring that all students can improve their listening skills according to their unique needs.

The aim of this teaching was to improve students’ critical thinking, collaboration and communication skills, and intercultural competence. The improvement of collaboration and communication skills was attributed to the cooperation and interaction between online and offline groups, as well as teacher-student communication. The advanced online learning platform ensured effective teacher-student and student–student interaction after class. Teachers could upload resources, issue course notices, initiate discussions, assign various types of individual and group tasks, supervise, remind, and guide students via computer or mobile phone. Students were given more flexibility in arranging their study time and could receive instant messages from teachers and group members.

The cultivation of critical thinking and intercultural competence primarily relied on the design of teaching activities and the selection of teaching materials. However, it was only through blended learning, which broke the limitations of physical classroom conditions, that teachers had the freedom to integrate more teaching materials and engage in more refined teaching activities to guide students’ thinking and cultivate intercultural awareness. Critical thinking and intercultural attitudes were skillfully woven into language teaching. In contrast, if traditional offline teaching had been used, the limited time available could only have been allocated to language instruction.

Therefore, the above POA-based blended learning mode not only addresses the traditional limitations of language training in this course but also plays a crucial role in cultivating a range of virtues and essential competences needed in the 21st century. This approach goes beyond simply teaching language skills; it integrates the development of personality and character traits into the learning process.

All in all, the POA-based blended learning mode made learning happen beyond the classroom and increased students’ investment in listening and speaking practice. What’s more, by using listening activities as enables and speaking tasks as the drive, it successfully stimulated students’ motivation to learn and integrated learning and using. Also, it has achieved relatively good effectiveness in both language training and cultivation of virtues and other competencies such as critical thinking competency, collaborative competency, and cultural competency.

Also, this mode may be adopted by EFL learners from other cultures as well. On the one hand, although POA is a Chinese-featured theory, its applicability in different cultural contexts has been discussed since the second international forum on innovative foreign language education in China, which was held at the University of Vienna, Austria, on 13–14 October 2017. Experts discussed about how POA could be positioned in relation to ELT theories and praxis in the international field of language education. Some perceived the contextual similarity English language teaching between Hungary and China and discussed issues in relation to the pedagogical practice of POA (Pu, 2018). What’ more, POA has been successfully applied in other cultural contexts, such as in Indonesia, Japanese, South Korea, and Thailand (Nur, 2019; Tian, 2019; Yin, 2019). The findings of Yin (2019) provide data to support the applicability of POA in teaching writing in the Korean EFL context. Therefore, the POA-based teaching mode constructed in our study is likely to have some implications on the teaching of English listening and speaking in other countries. On the other hand, although the content of the practice in this study is related to Chinese figure and Chinese culture, the shining points of the diverse cultures in the world provides resources to be integrated with language teaching. By means of teaching content, teaching procedures and activities, students can develop different competencies and shape their personalities and outlook. Therefore, the applicability of this mode can go beyond the Chinese context.

In general, the POA-based blended learning mode constructed in this study not only effectively solves the traditional drawback of “separation of learning and using,” but also naturally integrates the cultivation of key competencies and moral education into language teaching. Through online and offline teaching design, students’ interest can be stimulated, and students can fully participate in the learning process. While sharpening the basic language skills, students can exercise their learning competency, critical thinking competency, collaborative competency, cultural competency, and other key competencies in the 21st century, and shape a correct outlook on life and world.

This study has some limitations. First, the results may not be persuasive due to the small sample size and the lack of the control group. Second, the time of the experiment was short, and there was no long-term tracking of changes in students’ language proficiency and other abilities. Third, the study did not provide quantitative evidence of improvements in other student abilities. Self-assessment by questionnaires was subjective and the results need to be verified by other possible methods. Fourth, the teacher’s own classroom observation may be biased and lack objectivity. This potential bias could be mitigated by involving independent peer observers or using video recordings to analyze classroom interactions in future research. Fifth, although the after-class enabling activities were aimed at creating space for students’ individual development and ensuring the diversity of the output content, the content was to a considerable extent prescribed by the teaching materials. It would be better to add an extension activity at the end of the unit so that students can engage in personal expression. The contradiction between creativity and the POA’s principle of alignment needs to be solved in the future.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethic Committee of the School of Foreign Languages, Guangzhou City University of Technology. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JC: Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research received funding from Special Group on Philosophy and Social Science Planning of Guangdong Province. It is one of the outcomes of the research project (GD23WZXY02–06) entitled “The construction and practice of the POA-based teaching mode of integrating Chinese excellent traditional culture into English Viewing, Listening, and Speaking Course for English majors.”

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1512667/full#supplementary-material

Bi, Z. (2017). Evaluating the attainment of productive objectives through the use of POA teaching materials. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 10:40-46+96.

Bi, Z. (2019). Exploring the use of POA-based teaching materials: dialectical research. Modern Foreign Lang. 3, 397–406.

Chang, X. L. (2017). Textbook writing based on the production-oriented approach. Modern Foreign Lang. 3, 359–368.

Chen, H., and Wen, Q. F. (2020). POA-based instruction of nominalization in academic English writing course: taking enabling phrase for example. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 1, 15–23.

Deng, H. L. (2018, 2018). Comparison of "production-oriented approach" and "task-based approach": concept, hypothesis and process. Foreign Lang. Teach. 39, 55–59.

Han, Y., and Hyland, F. (2016). Oral corrective feedback on L2 writing from a sociocultural perspective: a case study on two writing conferences in a Chinese university. Writing Pedag. 8, 433–460. doi: 10.1558/wap.27165

Hu, J. H., and Hu, J. S. (2020). Theoretical and paradigm evolution of foreign language education Informatization in the past 70 years. Foreign Lang. e-Learn. 1:17-23+3.

Li, Z. (2017). Practical research on the production-oriented approach in higher vocational college English flipped classroom. China Vocat. Technic. Educ. 31, 88–92.

Liang, W. H., Xiang, M. W., and Zhang, C. (2022). Diachronic and synchronic characteristics of studies on college English blended teaching in China. Foreign Lang. E-learn. 2:32-38+116.

Liu, Q. Q. (2023). A practical study on the improvement of ideological and political education effectiveness in translation course based on “production-oriented approach”. J. Guangdong Industry Polytechnic 3, 58–63. doi: 10.13285/j.cnki.gdqgxb.2023.0036

Liu, J., Gao, Y., Altbach, P. G., and Hans, D. V. (2020). Atterbach on the impact of the new crown epidemic on the internationalization of global higher education. Modern Univ. Educ. 6, 31–38.

Liu, J., Gao, Y., and Wu, Y. (2021a). Opportunities and challenges of internationalizing higher education in the context of online teaching and learning: an interview with Hans de Witte, director of the Centre for International Higher Education Studies at Boston College. World Educ. Inform. 4:17-20+48.

Liu, J., Lin, S. Y., and Gao, Y. (2021b). The new normal of the internationalization of higher education in the post-epidemic era -- based on in-depth interviews with 21 scholars including Philip G. Altbach. Educ. Res. 42, 112–121.

Lundstrom, K., and Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: the benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 18, 30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Nie, W., Lu, T., and Liu, P. L. (2023). The design and implementation of English negotiation practice teaching using the production-oriented approach. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 6:19-27+93. doi: 10.20083/j.cnki.fleic.2023.02.019

Nur, A. D. (2019). “Promoting a production-oriented approach to emerging extensive reading in a tertiary context. [Paper presentation]” in The 17th Asia TEFL and 6th ELL conference (Bangkok, Thailand).

Pan, Q. J., Hu, Y. H., and Que, M. K. (2020). Challenges and innovations in higher education teaching and learning in the post-epidemic era: an interview with professor Ulrich Teichler, a world-renowned expert on higher education. Fudan Education Forum 18, 10–16. doi: 10.13397/j.cnki.fef.2020.06.003

Pu, S. (2018). Production-oriented approach in different cultural contexts: theory and practice. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 41, 236–237. doi: 10.1515/cjal-2018-0014

Qiu, L. (2017). The step-by-step design of language activities in the production-oriented approach. Modern Foreign Lang. 3, 386–396.

Qiu, L. (2019). Promoting enabling effectiveness in POA instruction: dialectical research. Modern Foreign Lang. 3, 407–417.

Qiu, L. (2020a). Designing enabling activities in the production-oriented approach. Beijing, China: Foreign Language Teaching and Re-search Press.

Qiu, L. (2020b). Contradictions and resolutions in different stages of teacher professional development in applying the production-oriented approach. Foreign Lang. China 1, 68–74. doi: 10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2020.01.010

Qiu, L. (2020c). Enabling in the production-oriented approach: theoretical principles and classroom implementation. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 43, 284–304. doi: 10.1515/CJAL-2020-0019

Sun, S. G. (2017). Teacher-student collaborative assessment in classroom teaching: a reflective practice. Modern Foreign Lang. 40, 397–406.

Sun, S. G. (2020a). Optimizing teacher-student collaborative assessment in the production-oriented approach: a dialectical research. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 43, 305–322. doi: 10.1515/CJAL-2020-0020

Sun, S. G. (2020b). Teacher-student collaborative assessment in the production-oriented approach. Beijing, China: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 43:305–322.

Sun, S. G. (2020c). Teacher development by applying the teacher-student collaborative assessment: an expansive learning perspective. Foreign Lang. China 1, 75–83. doi: 10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2020.01.011

Sun, S. G., and Wen, Q. F. (2018). Teacher-student collaborative assessment (TSCA) in integrated language classrooms. Indonesian J. Appl. Linguist. 8, 369–379. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v8i2.13301

Suzuki, M. (2008). Japanese learners’ self revisions and peer revisions of their written compositions in English. TESOL Q. 42, 209–233. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00116.x

Tian, W. W. (2019). Applying POA to teacher development in an ELT MA course in Thailand: a social-constructivist practice. [Paper presentation] The sixth international symposium on the theory and practice of POA. Seoul, South Korea.

Wang, Z. L. (2020). Replacing the classroom, or going beyond it? --controversies and reflections on online education. Modern Distance Educ. Res. 5, 35–45.

Wang, Y. (2021). System construction of ideological and political education in English writing teaching based on production-oriented approach. Foreign Lang. Liter. 5, 147–156.

Wang, J. J., and Lu, P. (2024). Integration and incorporation: POA-guided teaching design of moral education through college foreign language teaching. Foreign Lang. Educ. China. doi: 10.20083/j.cnki.fleic.2024.0005

Wen, Q. F. (2016). Teacher-student collaborative assessment: a new form of assessment for the production-oriented approach. Foreign Lang. World 5, 37–43.

Wen, Q. F. (2017). A theoretical framework for using and evaluating POA-based teaching materials. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 10:17-23+95-96.

Wen, Q. F. (2018a). The production-oriented approach to teaching university students English in China. Lang. Teach. 51, 526–540. doi: 10.1017/S026144481600001X

Wen, Q. F. (2018b). Production-oriented approach in Chinese as a second language. Chinese Teach. World 3, 387–400. doi: 10.13724/j.cnki.ctiw.2018.03.008

Wen, Q. F. (2020a). Production-oriented approach: Developing a theory of foreign language education with Chinese features. Beijing, China: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Wen, Q. F. (2020b). Constructing a theoretical framework for the development of experienced foreign language teachers. Foreign Lang. China 1, 50–59. doi: 10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2020.01.008

Wen, Q. F., and Sun, S. G. (2020). Design scenarios for the motivating phase in the POA: key elements and examples. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 2, 4–11.

Yang, L. F. (2015). How to design a video-taped micro-lecture for the motivating phase of the production-oriented approach. Foreign Lang. Educ. China 4, 3–9.

Yang, M., Badger, R., and Zhen, Y. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 15, 179–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2006.09.004

Yin, J. (2019). The production-oriented approach to teaching writing in South Korea: English as a foreign language pre-service teachers’ experiences with reading-to-write. J. Asia TEFL 16, 547–560. doi: 10.18823/asiatefl.2019.16.2.7.547

Zhang, L. L. (2020). Motivating in the production-oriented approach: from theory to practice. Chinese J. Appl. Linguist. 43, 268–283. doi: 10.1515/CJAL-2020-0018

Zhang, W. J. (2020). Applying the production-oriented approach to college English teaching: a self-narrative study. Foreign Lang. China 1, 60–67. doi: 10.13564/j.cnki.issn.1672-9382.2020.01.009

Zhang, D. (2021). Construction and application of a blended Golden course framework of college English. Technol. Enhanced Foreign Lang. Educ. 1:71-77+91+12.

Zhang, W. L. (2022). Approaches to and the effects of integrating elements for the cultivation of morality in English major courses: taking the “English teaching and research course” as an example. J. Beijing Second Foreign Lang. Univ. 4, 18–35.

Zhou, Y. F. (2020). The impact of the new pneumonia epidemic on the internationalization of higher education. World Educ. Inform. 5, 13–15.

Keywords: blended learning, English viewing, listening and speaking course, the production-oriented approach, key competency cultivation, moral education

Citation: Cheng J (2025) Blended learning reform in English viewing, listening and speaking course based on the POA in the post-pandemic era. Front. Educ. 10:1512667. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1512667

Received: 19 October 2024; Accepted: 23 January 2025;

Published: 05 February 2025.

Edited by:

Hanxi Wang, Harbin Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Panagiotis Tsiotakis, University of Peloponnese, GreeceCopyright © 2025 Cheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiaxue Cheng, Y2hlbmdqeEBnY3UuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.