94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 20 March 2025

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1510765

The acquisition of a second language frequently induces anxiety among students, particularly in speaking situations. This anxiety often stems from linguistic insecurity, fear of mispronunciation, and perceived judgment from both instructors and peers. Proficiency in public speaking is a critical goal in teacher training programs and is progressively developed throughout the education of prospective teachers. This study examines the level of language anxiety among future primary school teachers at the Higher Normal School of Casablanca, identifies the factors contributing to this anxiety, and proposes strategies to mitigate it. The findings reveal that anxiety arises from diverse factors, including fear of negative evaluation, lack of confidence, and insufficient opportunities for oral practice. These results underline the importance of teacher training programs in addressing emotional barriers through tailored strategies such as collaborative learning activities, gradual exposure to speaking tasks, and explicit training on coping mechanisms. Implementing these methods could help prospective teachers not only overcome their own anxiety but also equip them to support their students effectively in language learning environments. By linking the findings to practical implications, this study highlights the necessity of integrating emotional support mechanisms into teacher training programs. Such initiatives aim to foster both linguistic competence and emotional well-being, ensuring future educators are better prepared to create inclusive and supportive classroom environments.

When exploring the sociolinguistic landscape of Morocco, it becomes evident that the country is characterized by a rich linguistic diversity, as outlined by Boukous (2008) and Mabrour and Mgharfaoui (2011). This diversity is composed of three main linguistic groups: (a) the Amazigh linguistic block, encompassing three distinct dialectal varieties; (b) the Arabic linguistic block, which includes Modern Standard Arabic and Moroccan Arabic dialects; and (c) the foreign language block, featuring French, English, and Spanish. In the Moroccan education system, Arabic serves as the official language, while foreign languages, particularly French, play a key role. French is introduced as a subject in the second year of primary education in public schools and even earlier in private schools, becoming the language of instruction in higher education for scientific and technical disciplines (Hachimi, 2020). This reflects its utilitarian role in various socioeconomic contexts and as a medium for the dissemination of scientific and cultural knowledge.

Globally, foreign language acquisition has been identified as a complex process requiring significant effort and often triggering emotional barriers. Research by Bogaards (1991) highlights how emotional filters, such as anxiety and low self-esteem, can hinder motivation and enjoyment of learning. These emotional challenges are particularly pronounced in oral production tasks, where students face heightened vulnerability. Recent studies emphasize that foreign language anxiety is more frequent during production (e.g., speaking) than reception (e.g., listening or reading) (Castillo-Rodríguez and Santos-Díaz, 2022). Additionally, the format in which languages are learned (e.g., digital versus paper) also influences students’ emotional responses (Peña-Acuña and Crismán-Pérez, 2022). These insights underscore the need for research that examines the emotional dimensions of language learning in specific cultural and linguistic contexts, such as Morocco.

While emotions are frequently viewed as disruptive in speaking situations, they are integral to students’ experiences and can significantly affect performance. In Moroccan classrooms, where multilingualism and cultural diversity are prominent, students often face an “identity shock” as they reconcile their native linguistic and cultural backgrounds with the target language. Additionally, students must navigate interactions within heterogeneous groups, which can exacerbate feelings of insecurity and anxiety. Language then becomes both a tool for communication and a potential barrier, affecting students’ confidence and self-esteem. Horwitz et al. (1986) coined the term “foreign language anxiety” to describe the discomfort students feel in speaking situations, particularly when perfection is expected. This phenomenon is evident in Moroccan classrooms, where students often refrain from speaking due to fear of making mistakes or being judged by their peers (Horwitz et al., 1986).

To address these challenges, it is crucial to create a supportive learning environment that minimizes negative emotions, such as anxiety and frustration, while fostering confidence and self-esteem. This study aims to assess the level of foreign language anxiety among prospective primary school teachers at the Higher Normal School of Casablanca, identify its causes and manifestations, and propose strategies for classroom organization and activities that account for emotional factors.

To better understand the emotional challenges faced by prospective primary school teachers in foreign language classrooms, this study seeks to address the following research questions:

1. What is the level of foreign language anxiety among prospective primary school teachers, and how does it vary by educational level?

2. What factors contribute to speaking anxiety among prospective primary school teachers in foreign language classrooms?

3. Which dimensions of foreign language anxiety are most prevalent among prospective primary school teachers?

Foreign language anxiety (FLA) is defined as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (Horwitz et al., 1986, p. 128). This definition highlights the situational nature of FLA, meaning that even individuals who do not usually consider themselves anxious may experience this type of anxiety in specific contexts, such as language learning (MacIntyre et al., 1999; Teimouri et al., 2019). To measure and better understand this phenomenon, Horwitz et al. (1986) developed the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS), a reliable and widely used instrument in studies on language anxiety (Horwitz, 2010). Using this tool, researchers have conducted systematic investigations (e.g., MacIntyre and Gardner, 1991; Phillips, 1992; Aida, 1994), which have consistently revealed a negative correlation between FLA and academic performance. These detrimental effects of FLA on academic outcomes have been confirmed across various linguistic contexts, including the acquisition of multiple foreign languages and specific linguistic skills (e.g., Kitano, 2001; Yan and Wang, 2001; Kondo and Yang, 2004; Matsuda and Gobel, 2004; Elkhafaifi, 2005; Agobia and Kodah, 2023; Andreuccetti, 2024; Milhaud, 2024).

While the FLCAS has been widely validated and employed in diverse educational contexts, one limitation is its cultural adaptability. In multilingual environments like Morocco, where Arabic, French, and increasingly English are central to education, the unique sociolinguistic dynamics may amplify or modify how FLA manifests. The reliance on French as the primary medium of instruction in higher education and the simultaneous emphasis on mastering English in an increasingly globalized economy place Moroccan students under unique pressures. Despite the robustness of studies from Anglophone and Asian contexts, there is a lack of research investigating how FLA interacts with the multilingual realities and educational policies of Morocco. Addressing this gap is crucial for tailoring effective interventions to reduce anxiety and improve learning outcomes.

Language learning anxiety can manifest in several dimensions, including communication apprehension, fear of negative evaluation, and test anxiety (Horwitz et al., 1986).

Communication apprehension refers to the anxiety students feel when expressing themselves in a foreign language in front of a group. This type of anxiety differs from glossophobia, which pertains to the fear of public speaking regardless of the language used. Fear of negative evaluation, on the other hand, reflects the apprehension of being judged unfavorably by one’s social environment. This fear may arise in contexts such as job interviews or public presentations, where students worry not only about their teachers’ evaluations but also about judgment from their peers, whether real or imagined. These two dimensions are often amplified by test anxiety, which stems from fear of failure and a desire to achieve often unattainable perfection. This interplay of interconnected factors makes each experience of language anxiety unique and highly individual.

Several studies have sought to identify the causes of FLA, highlighting various triggers and exacerbating factors. Young (1991) proposed six main sources of language anxiety: personal and interpersonal factors, teacher attitudes, student-teacher interactions, oral activities, exams, and beliefs about language learning. Personal factors include low self- confidence and unrealistic expectations, leading to frustration and disappointment when students fail to meet their goals. Teacher attitudes, such as an excessive emphasis on error correction, can exacerbate anxiety by creating an environment perceived as punitive. Interactions with teachers and peers, particularly the fear of others’ reactions, also represent a significant source of anxiety. Oral activities, such as presentations or answering questions in class, as well as the gap between students’ expectations and the content assessed in exams, are frequently cited as major stressors. Finally, unrealistic beliefs about language learning, such as the idea that it is possible to quickly attain perfect mastery of a foreign language, contribute to heightened language anxiety.

Recent studies have expanded the scope of FLA research by exploring its relationships with other variables. For example, FLA has been correlated with willingness to communicate (Liu and Jackson, 2008; Zhou et al., 2020), self-efficacy (Mills et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2022), motivation (Alamer and Almulhim, 2021), and learning autonomy (Ahmadi and Izadpanah, 2019). Students who develop a strong perception of their abilities and intrinsic motivation tend to experience less anxiety and perform better.

However, these variables may interact differently in multilingual contexts like Morocco, where cultural expectations, language hierarchies, and institutional practices heavily influence learner experiences. For instance, students may feel greater anxiety when learning a foreign language that is perceived as socially or economically prestigious, such as English or French.

To explain how FLA negatively impacts language learning, researchers have developed several theoretical mechanisms. Krashen’s (1987) affective filter hypothesis posits that when this filter is activated by negative emotions such as anxiety, input information is blocked and fails to reach the students’ brains. This hypothesis is supported by MacIntyre’s (1995) three-stage model, which distinguishes between input, processing, and output phases in language learning. During the input phase, students’ attention may be diverted by irrelevant concerns, such as the fear of negative evaluation, preventing the encoding of information. The processing phase is also compromised, as the speed and accuracy of storing information can decrease. However, in the output phase, some students manage to compensate for the negative effects of anxiety through increased effort, as observed by MacIntyre and Gardner (1994). While these theoretical frameworks provide robust explanations, they often overlook how sociolinguistic factors, such as those present in Morocco, mediate the relationship between FLA and performance.

By situating FLA within the Moroccan context, this study aims to bridge the gap between global research on language anxiety and the specific challenges faced by students in a multilingual educational system. In particular, it will explore how the interplay between Arabic, French, and English in Moroccan classrooms shapes students’ experiences of FLA and their coping strategies. This contribution is essential not only to understand the phenomenon in a culturally specific setting but also to develop interventions that align with the needs and realities of Moroccan students.

To achieve the objectives of this study, a quantitative approach was adopted, which involves categorizing the various positions or attitudes expressed in the responses to enable a quantified interpretation of the results. This method allows for the collection of standardized data, facilitating analysis and the formulation of generalizable conclusions. The findings from this study will inform the design of targeted interventions to reduce language anxiety among pre-service teachers. By identifying students with high levels of anxiety and understanding the factors contributing to their stress, teacher training programs can implement strategies to foster a more supportive learning environment. For instance:

• Students with high communication apprehension may benefit from role-playing exercises and group discussions to build confidence.

• Tailored feedback and supportive teaching practices can help alleviate test anxiety and fear of negative evaluation.

These interventions will contribute to improving the overall well-being and academic performance of future educators in Morocco.

The study included a total of 95 participants, comprising 84 women and 11 men, distributed as follows: 58 first-year students enrolled in the primary education specialization program, 18 s-year students, and 19 third-year students. These participants were selected from the primary specialization program at the Higher Normal School of Casablanca.

The predominance of female participants reflects broader trends in teacher training programs in Morocco, where women represent a significant majority. While this gender imbalance aligns with the demographic reality of the field, it may also influence the results. Analyses will include statistical tests to determine whether gender differences.

significantly affect reported anxiety levels. Additionally, the comparability of data across the three educational levels will be assessed to ensure the validity of intergroup comparisons.

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling method. A Google Forms link was distributed through university discussion groups (WhatsApp and email), accompanied by a detailed explanatory document outlining the study’s objectives, usage modalities, and confidentiality criteria. Students were informed that their participation was voluntary, and their responses would remain anonymous. A statement in the introduction of the questionnaire explicitly mentioned: “By responding to this questionnaire, you voluntarily consent to participate in this study and agree to the use of your data for scientific research purposes.”

Despite repeated reminders, the response rate reached 63.3% (95 out of 150 potential participants). This rate may have been influenced by factors such as academic workload or limited interest in the study (Figure 1).

To accomplish the objectives of this study, we opted for the utilization of the FLCAS, a questionnaire developed by Horwitz et al. (1986), which has exhibited a high level of reliability. In its original configuration, the questionnaire comprises 33 items, and respondents provide their feedback using the Likert scale, a tool measuring individual attitudes on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

To ensure its relevance in the Moroccan context, the questionnaire was translated into French. The translated version was piloted with a group of 10 students to verify their understanding of the questions and identify necessary linguistic adjustments. Modifications included simplifying certain terms to better reflect the local educational context while maintaining the validity and reliability of the instrument.

Firstly, a preliminary meeting was held with the students in the three groups to obtain their consent to take part in the study. Then, certain instructions were clarified:

The assessment of language anxiety can be classified into three distinct levels. A score below 3 indicates a low level of language anxiety, suggesting that the individual’s anxiety is not of concern. Scores between 3 and 4 indicate a moderate level of anxiety, meaning that responses fall between neutrality and some degree of agreement with the questionnaire questions. Finally, an average score between 4 and 5 indicates a high level of anxiety, suggesting agreement or strong agreement with most of the questionnaire questions relating to language anxiety. This classification serves as a tool for identifying students who need additional support to manage their language anxiety, thereby improving their academic performance and general well-being.

Average communicative apprehension was calculated from 16 questionnaire items: 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 12, 14, 18, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 32. In addition, mean fear of negative evaluation was calculated for questions 3, 7, 13, 15,16, 17, 20, 23, 25, 31, 33. In addition, the concept of test anxiety comprises 5 items: 2, 8, 10, 19 and 21. Once all the data had been collected, a careful analysis was carried out.

This study adhered to ethical standards for research involving human participants. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. Data were used exclusively for research purposes and stored securely to prevent unauthorized access.

The mean scores for different types of language anxiety (communicative apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation) were calculated for the three groups of students, categorized by their year of study. The results are presented in Table 1.

The results indicate significant variations between the three groups regarding the different types of language anxiety:

The mean scores reveal that second-year students exhibit the highest levels of communicative apprehension (53.38), followed by third-year students (49.35) and first-year students (46.19). This trend suggests that as students advance in their studies, they experience increasing pressure to communicate effectively in French, likely due to greater academic expectations and more demanding oral activities. The slight decline in third-year scores may indicate a partial adaptation to these linguistic challenges, as students develop coping mechanisms and gain more experience in oral communication.

The highest levels of fear of negative evaluation were recorded among second-year students (33.90), followed by third-year students (29.64) and first-year students (27.44). This pattern suggests that second-year students are more sensitive to peer and teacher judgment, potentially due to heightened academic expectations and a more competitive learning environment. The slight decrease in the third year may be attributed to increased self-confidence and greater experience in managing evaluations, allowing students to feel more at ease with assessments and feedback.

The analysis of test anxiety scores reveals that second-year students report the highest levels (16.01), followed by first-year students (14.94) and third-year students (14.93). The elevated anxiety levels among second-year students may be attributed to the increased difficulty of coursework and the higher stakes of examinations during this academic stage. In contrast, the slightly lower scores observed in the third year suggest that students may have developed better test-taking strategies and coping mechanisms over time. Additionally, third-year students likely benefit from increased familiarity with assessment formats and expectations, allowing them to approach tests with greater confidence and reduced stress.

These variations confirm that the second year is a critical period during which students are particularly vulnerable to both fear of negative and communicative apprehension. This trend could be explained by greater academic pressure, more frequent assessments, and heightened awareness of peer comparison.

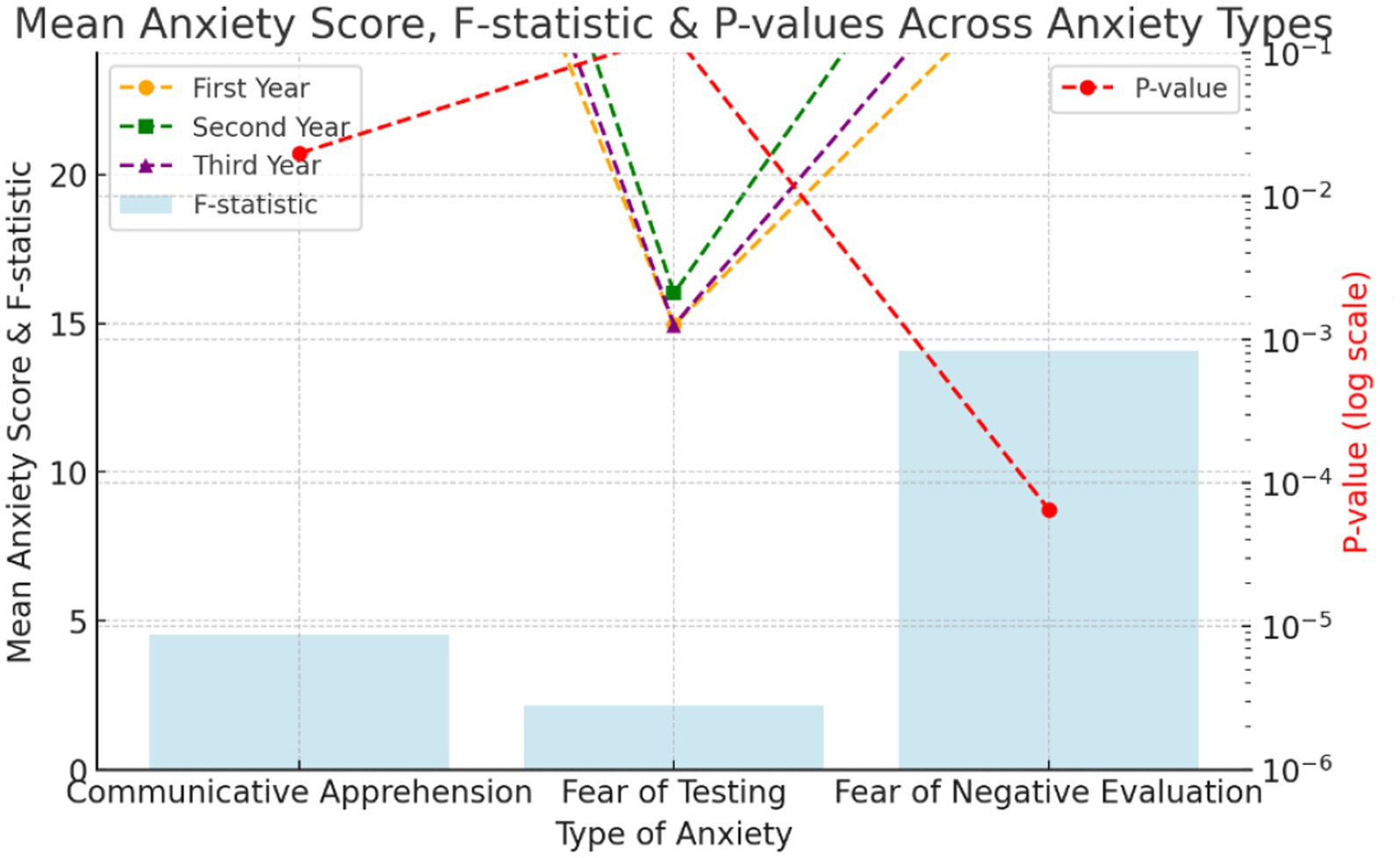

To assess the statistical significance of these differences, an ANOVA analysis was conducted. The results are summarized in Table 2.

The ANOVA results (Table 2) confirm a statistically significant difference in communicative apprehension across academic levels (f = 4.54, p = 0.0199). The increase from 46.19 in the first year to 53.38 in the second year, followed by a slight decline to 49.35 in the third year, suggests that oral communication anxiety peaks in the second year. This could be attributed to greater exposure to interactive speaking tasks, higher fluency expectations, and increased participation in classroom discussions. The slight decline in the third year may indicate a degree of adaptation or the development of coping strategies, allowing students to feel more confident when speaking in French. The significant p-value (0.0199) confirms that these differences are not due to chance and that communicative apprehension is indeed influenced by academic progression.

A highly significant effect was observed for fear of negative evaluation (f = 14.08, p = 0.000065), indicating that this type of anxiety varies considerably across academic levels. The increase from 27.44 in the first year to 33.90 in the second year, followed by a reduction to 29.64 in the third year, suggests that students in their second-year experience heightened anxiety regarding peer and teacher judgment. This may be due to increased academic expectations, social comparison, and a greater awareness of language proficiency gaps. The decline in the third year could reflect growing self-confidence, improved resilience, and familiarity with evaluation criteria. The extremely low p-value (0.000065) confirms that these differences are highly statistically significant, meaning that fear of negative evaluation is strongly influenced by academic progression.

Unlike the other two dimensions of anxiety, test anxiety does not vary significantly between academic levels (f = 2.16, p = 0.135). The nearly identical scores (14.94 in the first and third years, with a slight increase to 16.01in the second year) suggest that test-related anxiety remains relatively stable across all years. This could imply that students experience consistent stress related to exams and assessments, regardless of their academic progression. Although the second-year students display a slightly higher mean, the differences are not statistically significant, indicating that test-related anxiety is not significantly affected by academic level.

These results confirm that language anxiety fluctuates significantly across academic levels, with the second year emerging as the most critical period. While test anxiety remains stable, communicative apprehension and fear of negative evaluation show the most variation, peaking in the second year before declining in the third. The statistically significant p-values for the first two anxiety dimensions reinforce the validity of these findings and highlight the importance of targeted interventions to support students during this crucial stage of language learning (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evolution of anxiety levels across academic years and statistical significance (Anova results). Source: Authors.

The initial facet under consideration is “communicative apprehension,” encompassing items 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 12, 14, 18, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 32 The analysis of the data reveals significant variations in means and standard deviations (SD) across the 3 years of study. These fluctuations provide insights into the dynamics of anxiety and self-confidence in the context of learning French as a foreign language (Table 3).

In general, mean scores tend to increase between the first and second years, indicating heightened levels of anxiety or insecurity during this period. A slight stabilization or decrease is observed for some items in the third year. The standard deviations (SD), which measure the variability of responses, increase during the second year, suggesting greater individual differences in students’ experiences at this critical stage.

The item “I never feel sure of myself when I speak in a French class” follows a relatively stable trend: 2.67 (SD = 0.40) in the first year, increasing to 2.90 (SD = 0.44) in the second year before dropping to 2.65 (SD = 0.40) in the third year. This pattern suggests that while students experience a temporary increase in insecurity in the second year, their confidence improves in the third year.

Similarly, the statement “I panic when I have to speak without preparation in French class” shows a notable increase from 3.08 (SD = 0.46) in the first year to 3.80 (SD = 0.57) in the second year, followed by a slight decrease to 3.53 (SD = 0.53) in the third year. This fluctuation highlights the impact of growing expectations for spontaneous communication, particularly in the second year.

The item “I do not feel confident speaking in French” also shows a continuous increase: 2.44 (SD = 0.37) → 3.00 (SD = 0.45) → 3.18 (SD = 0.48), suggesting that students struggle with confidence as they progress, possibly due to more complex linguistic demands.

The difficulty of understanding spoken French increases over time, as evidenced by the item “I’m scared when I do not understand what my teacher is saying in French,” which initially decreases from 2.53 (SD = 0.38) in the first year to 2.40 (SD = 0.36) in the second year but rises significantly to 2.76 (SD = 0.41) in the third year. This suggests that while comprehension may initially improve, the increasing complexity of classroom discourse in advanced levels may heighten students’ anxiety.

A similar trend is observed in “I get nervous when I do not understand what my teacher is saying,” where mean scores rise from 3.03 (SD = 0.45) in the first year to 3.50 (SD = 0.53) in the second year before slightly decreasing to 3.24 (SD = 0.49) in the third year. This could indicate that the pressure of understanding spoken French peaks in the second year before students develop coping strategies in their final year.

Students also express concerns about keeping up with the pace of the course. The item “The pace of the French course is so fast that I’m afraid I will not be able to keep up” follows a similar pattern: 2.10 (SD = 0.04) → 2.65 (SD = 0.09) → 2.35 (SD = 0.08). The increase in the second year reflects heightened academic demands, while the slight decline in the third year may indicate better adaptation.

Engaging with native speakers remains a significant challenge, as reflected in the item “I would be nervous to speak with people whose mother tongue is French,” where mean scores remain high: 3.27 (SD = 0.49) in the first year, peaking at 3.59 (SD = 0.54) in the second year, before slightly decreasing to 3.30 (SD = 0.50) in the third year. This persistent anxiety suggests that, despite growing familiarity with the language, many students continue to feel uncomfortable interacting with native speakers. Conversely, students gradually feel more comfortable around native speakers, as indicated by “I would probably feel comfortable around native speakers of the foreign language,” which increases from 2.76 (SD = 0.42) in the first year to 3.36 (SD = 0.50) in the second year and 3.45 (SD = 0.87) in the third year. This improvement suggests that while initial apprehensions exist, exposure to the language and cultural interactions help ease students’ anxiety over time.

Students’ motivation fluctuates across the 3 years. The statement “I would not mind studying more French lessons” rises from 4.17 (SD = 0.08) in the first year to 4.47 (SD = 0.15) in the second year before declining to 3.75 (SD = 0.12) in the third year. The second-year peak may indicate enthusiasm for deeper language learning, while the third-year drop could reflect academic fatigue or competing priorities.

The item “During the French course, I often find myself thinking about things unrelated to class” also follows an interesting pattern, increasing from 2.22 (SD = 0.04) in the first year to 2.60 (SD = 0.09) in the second year before slightly decreasing to 2.40 (SD = 0.08) in the third year. This suggests that distractions may be more common in the second year, potentially due to cognitive overload.

Similarly, “I feel compelled to prepare for the French course” gradually declines from 2.17 (SD = 0.04) in the first year to 2.11 (SD = 0.07) in the second year and 2.00 (SD = 0.06) in the third year. This decrease may reflect students’ increasing confidence in managing course content without as much preparatory work.

A key challenge in language learning is mastering grammatical structures. The item “I feel overwhelmed by the number of rules that must be mastered to learn French” exhibits a steady increase: 2.67 (SD = 0.40) in the first year, 3.25 (SD = 0.49) in the second year, and 3.82 (SD = 0.57) in the third year. This trend highlights the growing perception of complexity as students’ progress to more advanced levels.

The results indicate that the second year represents a critical period of heightened anxiety, particularly in areas such as spontaneous speaking, comprehension, and classroom pressure. This phase coincides with increasing linguistic and academic demands, leading to greater individual differences in student experiences. However, by the third year, many of these anxieties begin to stabilize, suggesting a process of adaptation and increasing confidence. While some challenges, such as speaking with native speakers and mastering grammatical structures, persist over time, students gradually develop coping strategies that help them navigate the complexities of language learning.

The results (Table 4) reveal notable trends in students’ anxiety and self-perception during French lessons over the 3 years, highlighting critical aspects of fear and discomfort in the classroom.

One of the most striking findings concerns the fear of being called on in class. The item “I tremble when I know that I’m going to be called on in language class” shows a significant rise from 2.67 (SD = 0.05) in the first year to 4.00 (SD = 0.14) in the second year, before slightly decreasing to 3.65 (SD = 0.12) in the third year. This suggests that students experience increasing stress when speaking in class, especially in the second year, when expectations may be higher. Although this fear decreases slightly in the third year, it remains elevated. A similar pattern is observed for “I feel very complexed when I have to speak French in front of other students” (2.58 → 3.60 → 3.12), indicating that speaking in front of peers remains a source of anxiety.

The fear of negative evaluation also intensifies in the second year. The item “I’m afraid that other students will laugh at me when I speak French” increases from 2.58 (SD = 0.051) in the first year to 3.60 (SD = 0.127) in the second year, before decreasing to 2.35 (SD = 0.081) in the third year. This suggests that students become more self-conscious about making mistakes as they advance. However, the decline in the third year may indicate that they develop greater confidence and resilience over time.

The tendency to compare oneself to peers also plays a role in students’ anxiety. The item “I keep thinking that other students are better than I in French” rises from 2.53 (SD = 0.050) in the first year to 3.15 (SD = 0.111) in the second year, then declines to 2.70 (SD = 0.093) in the third year. A similar pattern is observed for “I feel that other students speak better French than me” (2.65 → 3.45 → 2.53). These results indicate that students become more aware of their abilities in relation to their peers in the second year, which may contribute to increased self-doubt. However, the decrease in the third year suggests that they gain more confidence and stop making as many comparisons.

Despite preparation, anxiety persists throughout the 3 years. The item “I feel anxious even when I am well prepared for the French course” increases steadily from 2.58 (SD = 0.05) in the first year to 2.95 (SD = 0.10) in the second year and 3.35 (SD = 0.11) in the third year. This suggests that students’ anxiety is not only linked to lack of preparation but also to the pressure of performing well in class. Frustration with learning also appears in “I get irritated when I do not understand the mistake corrected by my teacher” (2.98 → 3.20 → 3.00). This frustration peaks in the second year but slightly decreases in the third year, possibly as students adjust to feedback and corrections.

The results also show a change in students’ willingness to participate in class. The item “It embarrasses me to volunteer answers in my language class” follows a different pattern from other anxiety-related items, decreasing from 1.95 in the second year to 1.35 in the third year. This suggests that students gradually become more comfortable speaking up in class, despite their initial hesitation. The tendency to avoid class follows a similar trend. The item “I often feel like not going to my language class” slightly increases in the second year (1.77 → 1.95) but then drops to 1.35 in the third year, indicating a decrease in avoidance behavior.

Overall, the second year appears to be a critical phase during which anxiety, self-doubt, and fear of negative evaluation reach their highest levels. This period is marked by increased academic expectations and greater oral participation, which may explain the rise in anxiety. However, by the third year, many students show signs of adaptation, with a decline in self-comparison, fear of judgment, and avoidance of participation. While some challenges, such as spontaneous speaking and performance anxiety, persist, students seem to develop coping strategies that help them manage these difficulties over time.

To investigate the specific items related to test anxiety and assessments in French language classes, we analyzed a set of statements reflecting various anxiety-inducing factors. For each item, (Figure 3) we calculated the mean and standard deviation (SD) to identify the aspects that students found most anxiety-provoking. This approach allows us to capture both the average intensity of the responses and the variability among students, providing a comprehensive view of their experiences. The results highlight how different dimensions of test-related anxiety evolve over the course of 3 years and point to critical areas for pedagogical intervention.

The analysis of students’ responses to language learning anxiety and confidence reveals notable trends over the 3 years. In general, anxiety-related concerns fluctuate, with some aspects showing a steady increase while others decrease over time. The second year appears to be a transitional phase, characterized by heightened stress and uncertainty, whereas the third year demonstrates varying patterns of adaptation and confidence.

One of the most striking findings concerns students’ concern about making mistakes in class. The item “I do not worry about making mistakes in language class” decreases steadily from 3.10 (SD = 0.061) in the first year to 3.00 (SD = 0.106) in the second year and 2.41 (SD = 0.083) in the third year. This downward trend suggests that as students advance, they become increasingly aware of their errors, which may contribute to greater self-consciousness and hesitation in language production. The decline in confidence could reflect the transition from basic language structures to more complex linguistic expectations, where mistakes are more noticeable.

In contrast, students report increasing comfort during language assessments. The item “I am usually at ease during tests in my language class” rises from 3.27 (SD = 0.06) in the first year to 3.50 (SD = 0.12) in the second year, reaching 3.88 (SD = 0.13) in the third year. This trend indicates that over time, students may develop better test-taking strategies, increased familiarity with assessment formats, or improved language proficiency, which helps reduce test-related anxiety. This pattern contrasts with the overall increase in concern about making mistakes, suggesting that while classroom participation anxiety grows, performance anxiety in structured assessments decreases.

Concerns about failing the language class show a gradual decline over time. The item “I worry about the consequences of failing my foreign language class” starts at 3.74 (SD = 0.07) in the first year, decreases to 3.50 (SD = 0.12) in the second year, and further declines to 3.29 (SD = 0.11) in the third year. While anxiety remains relatively high, this decline suggests that students may gain confidence in their ability to pass the course as they progress. The second-year decrease may also indicate a shift in priorities, with students focusing more on linguistic competence rather than fear of failure.

A more variable trend is observed in students’ perceptions of their teacher’s correctional approach. The item “I am afraid that my language teacher is ready to correct every mistake I make” starts relatively low at 2.06 (SD = 0.041) in the first year but increases significantly to 2.75 (SD = 0.097) in the second year before decreasing to 2.17 (SD = 0.075) in the third year. This pattern suggests that in the second year, students may feel increased pressure to perform accurately, possibly due to more frequent corrections or stricter evaluation criteria. However, the decline in the third year indicates that students either become more accustomed to feedback or develop strategies to handle corrections more effectively.

The most notable increase over time is found in students’ confusion when preparing for assessments. The item “The more I study for an assessment, the more confused I get” rises from 2.77 (SD = 0.05) in the first year to 3.26 (SD = 0.11) in the second year and stabilizes at 3.18 (SD = 0.10) in the third year. This increase suggests that as students’ progress, they encounter more complex linguistic structures, greater expectations, and possibly higher cognitive overload, making test preparation more challenging. The slight decrease in the third year may reflect greater adaptation to study strategies or better comprehension of language rules.

Overall, these findings highlight the dual nature of language learning anxiety and confidence. While students gain ease in structured testing environments and develop greater confidence in passing the course, they simultaneously become more self-conscious about mistakes, corrections, and study confusion. The second year emerges as a key period of heightened anxiety, reinforcing the idea that this stage represents a transition where expectations and cognitive demands increase. However, the third-year results indicate partial adaptation, with some anxieties decreasing while others persist.

Linguistic anxiety is a complex and widespread phenomenon among students at all educational levels, from primary school to university. Previous studies, such as those conducted by Haskin et al. (2003), Horwitz et al. (1986), and Alamer and Almulhim (2021), have emphasized that students experience significant anxiety when engaging in oral communication activities in a foreign language. This anxiety stems from various factors, including the fear of making mistakes, apprehension about peer and teacher judgment, and performance-related stress (Horwitz et al., 1986; Price, 1991, cited in MacIntyre and Gardner, 1994).

The findings reveal that first-year students exhibit moderate levels of language anxiety, with a mean score of 46.19 for communication apprehension, lower than that of second- and third-year students. This can be attributed to their transition into a new academic environment combined with the challenges of learning a foreign language. This period is often accompanied by feelings of frustration and uncertainty. Moreover, the pressures of adapting to new academic and linguistic demands can exacerbate anxiety (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1994; Horwitz et al., 1986).

Second-year students report the highest levels of anxiety, particularly in terms communicative apprehension (mean score of 53.38) and fear of negative evaluation (33.90). These elevated levels can be linked to multifactorial causes, including the increasing complexity of coursework and heightened academic expectations (Rice et al., 2006). The second year represents a critical phase during which students are required to grasp more complex concepts while managing greater pressure to succeed.

Third-year students exhibit a slight decline in anxiety levels, as reflected in reduced mean scores for communicative apprehension (49.35) and fear of negative evaluation (29.64) This improvement can likely be attributed to better adaptation to academic requirements and an increased sense of competence.

The results highlight communication apprehension as a particularly prevalent issue. Speaking in front of an audience is the most anxiety-inducing aspect for students, especially during the second year, where the mean score reaches 53.38. As noted by Horwitz et al. (2010), this type of anxiety is often tied to evaluative situations where students fear failing to meet the expectations of peers or teachers.

Educators can address communication apprehension by fostering a supportive classroom environment and emphasizing that making mistakes is an essential part of the learning process (Alamer and Almulhim, 2021). Low-stakes activities, such as informal discussions, can also encourage students to express themselves without fear of judgment.

Fear of negative evaluation is a persistent dimension across all 3 years, associated with the fear of being judged by peers or teachers. This often results in avoidance of classroom participation. These findings align with Horwitz et al. (1986), who noted that the fear of negative evaluation can undermine students’ confidence.

Educators should create an inclusive classroom climate where errors are normalized and valued as learning opportunities. Clear disciplinary rules can also prevent behaviors such as peer mockery that exacerbate this fear.

While test anxiety remains a persistent concern among students, the results indicate that its variation across academic levels is not statistically significant (F = 2.16, p = 0.135). This suggests that students experience relatively stable levels of exam-related stress throughout their studies, regardless of academic progression. However, the consistently high mean scores indicate that testing remains a source of anxiety, reinforcing the need for supportive assessment strategies.

Incorporate informal discussions and role-playing to allow students to practice speaking without fear of failure.

Provide constructive feedback and reward individual efforts to reinforce students’ confidence.

Normalize mistakes as an integral part of the learning process to reduce the fear of judgment.

Equip students with strategies to manage anxiety positively and channel their stress effectively.

The findings demonstrate that language anxiety varies across years of study, peaking in the second year due to increased academic and linguistic demands. The three dimensions of anxiety—communication apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation—interact to shape students’ experiences. By implementing targeted strategies, educators can alleviate the effects of linguistic anxiety and create a more supportive learning environment. Future research could explore the impact of specific interventions on reducing linguistic anxiety in various academic contexts.

Language anxiety represents a major barrier to language learning, particularly in oral activities. Educational institutions serve as essential frameworks for implementing mental health prevention programs to address this issue (MacKean, 2011). Beyond the family environment, these institutions provide accessible and structured settings that reach a broad student population (Christner et al., 2011). Various programs have been developed based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (Higgins, 2006; Seligman et al., 2007), mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy (Lynch et al., 2011; Rogers and Maytan, 2012; Song and Lindquist, 2015), and second- and third-wave cognitive-behavioral strategies, including relaxation, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy (Deckro et al., 2002; Grégoire et al., 2016).

Research also highlights the effectiveness of gradual exposure techniques in reducing language anxiety, starting with low-stakes activities such as pair work or small group discussions before progressing to more demanding contexts. The adoption of scaffolding strategies provides progressive support to learners through tools such as sentence starters, vocabulary lists, and modeled oral production examples. Goh (2017) defines scaffolding as a structured instructional strategy designed to support learning while fostering independent thinking and problem-solving skills.

Scaffolding includes cognitive modeling, where instructors demonstrate and explain the steps necessary to complete a task. Farida and Rozi (2022) emphasize its central role in improving students’ oral proficiency by reducing cognitive load and equipping learners with essential linguistic resources. These strategies include the use of visual aids, self-assessment grids, and structured feedback. As learners gain fluency and confidence, instructional support is gradually reduced, fostering greater communicative autonomy (Goh, 2017).

Integrating a constructive approach to error correction and providing continuous support are essential for creating a positive learning environment (Farida and Rozi, 2022). A supportive classroom climate encourages students to approach oral tasks with confidence and engage actively in communicative interactions. The introduction of oral interpretation exercises, where students read prepared texts aloud, has been found beneficial for improving pronunciation and fluency while reducing anxiety through structured preparation and constructive feedback.

From a psychological perspective, managing language anxiety requires a multifaceted approach combining relaxation and mindfulness techniques. Research suggests that incorporating brief relaxation sessions at the beginning of lessons or integrating deep breathing exercises can equip students with strategies to manage anxiety during speaking tasks. Feedback delivery also plays a crucial role: constructive, strength-based comments contribute to a supportive classroom atmosphere. Offering written feedback as an alternative to public corrections can help mitigate feelings of intimidation and reinforce learners’ motivation.

Curriculum design also plays a central role in reducing language anxiety. The inclusion of progressive activities, such as role-playing and simulations, enables students to gradually develop their oral proficiency. Ongoing teacher training in evidence-based strategies, particularly cognitive-behavioral techniques and mindfulness approaches, serves as a powerful tool for supporting learners. Additionally, adopting flexible assessment methods, such as portfolios and group presentations, reduces the pressure associated with high-stakes evaluations while promoting self-reflection and communicative skill development.

Finally, social and cultural factors influence the effectiveness of anxiety-reduction strategies. Recognizing students’ diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds fosters an inclusive and collaborative learning environment, reducing fear of judgment. Encouraging peer interaction among students with varying proficiency levels enhances learning experiences and contributes to lowering anxiety.

In conclusion, addressing language anxiety requires an integrated approach that combines pedagogical, curricular, and psychological strategies. By fostering supportive classroom environments, utilizing evidence-based teaching methodologies, and implementing systemic curricular changes, educators and curriculum designers can significantly reduce students’ anxiety and enhance their success in foreign language acquisition.

Within the context of language education in Morocco, where national educational policy emphasizes Arabic as the official language while also integrating globally prevalent foreign languages, acquiring a second language—particularly in spoken classroom interactions—can induce anxiety and hinder the overall learning experience. This study highlights the multifaceted nature of language anxiety and its implications for future primary school teachers.

The findings indicate that language anxiety among students at the Higher Normal School of Casablanca is predominantly moderate, though individual variations exist. Among the three dimensions of language anxiety—communicative apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation—communicative apprehension emerged as the most significant source of anxiety. Specifically, students reported heightened discomfort in spontaneous communication situations and interactions with proficient French speakers. This study contributes to existing research by reaffirming the strong link between language anxiety, self-confidence issues, and students’ perceived competence in oral communication.

Furthermore, the findings reveal that second-year students experience the highest levels of anxiety, particularly in terms of communicative apprehension and fear of negative evaluation. This suggests that increased coursework complexity, heightened academic expectations, and greater peer comparison in the second year contribute to anxiety spikes. In contrast, third-year students demonstrated a slight reduction in anxiety levels, likely due to better adaptation to academic demands and an increased sense of competence.

While severe language anxiety was not widely reported, the prevalence of moderate anxiety remains a key concern, as even moderate anxiety can negatively impact classroom participation and overall learning outcomes. Given its impact, addressing the underlying emotional, cognitive, and social factors influencing students’ anxiety is essential.

To mitigate language anxiety, this study advocates for the adoption of teaching strategies that promote a supportive and inclusive classroom environment. Educators should normalize errors as part of the learning process, encourage gradual exposure to speaking activities, and provide constructive feedback to enhance students’ confidence. Additionally, fostering a sense of competence and addressing negative self-perceptions about language learning can significantly reduce anxiety. Future teacher training programs should integrate these findings to better prepare educators to manage language anxiety in their classrooms.

Given the statistical findings, targeted interventions are essential to help students navigate the challenges of oral communication in a foreign language while fostering confidence. Future research could further explore additional factors influencing language anxiety, such as cultural attitudes toward language learning, to develop even more tailored interventions.

In conclusion, while the rate of language anxiety observed in this study is not alarmingly high, it remains a significant challenge that must be addressed to enhance the learning experience of future primary school teachers. By implementing evidence-based strategies and creating a supportive learning environment, educators can effectively reduce anxiety and contribute to the development of confident, competent communicators in foreign language settings.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LO: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The work was carried out as part of Haroud Samia’s thesis at the Higher Normal School of Casablanca, under the supervision of Saqri Nadia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agobia, P. K., and Kodah, M. K. (2023). Anxiété langagière et l’âge de début d’appropriation dans le contexte multilingue ghanéen: Cas des étudiants de français. Akofena. 7, 21–34. doi: 10.48734/akofena.n007v1.03.2023

Ahmadi, M., and Izadpanah, S. (2019). The study of relationship between learning autonomy, language anxiety, and thinking style: The case of Iranian university students. Int. J. Res. English Educ. 4, 73–88. doi: 10.29252/ijree.4.2.73

Aida, Y. (1994). Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: The case of students of Japanese. Mod. Lang. J. 78, 155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02026.x

Alamer, A., and Almulhim, F. (2021). The interrelation between language anxiety and self- determined motivation: A mixed methods approach. Front. Educ. 6:618655. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.618655

Andreuccetti, L. (2024). L’anxiété langagière chez les élèves en classe d’anglais: Comment se manifeste l’anxiété langagière lors de la prise de parole des élèves en production orale en cours d’anglais? [Master’s thesis, INSPE de Bourgogne].

Bogaards, P. (1991). Dictionnaires pédagogiques et apprentissage du vocabulaire. Cah. Lexicol. 59, 93–107.

Boukous, A. (2008). “L’avenir du français au Maghreb” in L’avenir du français AUF/Éditions des Archives Contemporaines. ed. J. Maurais.

Castillo-Rodríguez, C., and Santos-Díaz, I. C. (2022). Hábitos y consumos lectores en lengua materna y lengua extranjera del futuro profesorado de educación primaria de la Universidad de Málaga. Investig. Sobre Lectura 17, 83–110. doi: 10.24310/isl.vi17.14483

Christner, R. W., Mennuti, R. B., Heim, M., Gipe, K., and Rubenstein, J. S. (2011). Facilitating mental health services in schools: Universal, selected, and targeted interventions. In A practical guide to building professional competencies in school psychology. eds. T. M. Lionetti, E. P. Snyder, and R. W. Christner. Springer Science + Business Media. 175–191. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6257-7_11

Deckro, G. R., Ballinger, K. M., Hoyt, M., Wilcher, M., Dusek, J., Myers, P., et al. (2002). The evaluation of a mind/body intervention to reduce psychological distress and perceived stress in college students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 50, 281–287. doi: 10.1080/07448480209603446

Elkhafaifi, H. (2005). Listening comprehension and anxiety in the Arabic language classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 89, 206–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00275.x

Farida, L. A., and Rozi, F. (2022). Scaffolding Talks in Teaching Speaking Skills to the Higher Education Students, Why Not? Asian Pendidikan 2, 42–49. doi: 10.53797/aspen.v2i1.6.2022

Goh, C. (2017). Research into practice: Scaffolding learning processes to improve speaking performance. Lang. Teach. 50, 247–260. doi: 10.1017/S0261444816000483

Grégoire, S., Lachance, L., Bouffard, T., Hontoy, L.-M., and De Mondehare, L. (2016). L’efficacité de l’approche d’acceptation et d’engagement en regard de la santé psychologique et de l’engagement scolaire des étudiants universitaires [The effectiveness of the approach of acceptance and commitment with regard to the psychological health and academic engagement of university students]. Canad. J. Behav. Sci. 48, 222–231. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000040

Hachimi, H. (2020). La formation des enseignants de français du secondaire qualifiant au Maroc: enjeux théoriques et pédagogiques et leur praticabilité en classe réelle. Expériences pédagogiques. 5, 75–89. Available at: https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/220155

Haskin, J., Smith, M., and Racine, M. (2003). Decreasing anxiety and frustration in the Spanish language classroom. ERIC. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED474368 (Accessed July 9, 2024).

Higgins, D. M. (2006). Preventing generalized anxiety disorder in an at-risk sample of college students: A brief cognitive-behavioral approach (Publication No. 3235646). Doctoral dissertation, The University of Maine. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Horwitz, E. K. (2010). Foreign and second language anxiety. Lang. Teach. 43, 154–167. doi: 10.1017/S026144480999036X

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 70, 125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Horwitz, E. K., Tallon, M., and Luo, H. (2010). “Foreign language anxiety” in Anxiety in schools: The causes, consequences, and solutions for academic anxieties. ed. J. C. Cassady (New York: Peter Lang Inc), 95–115.

Kitano, K. (2001). Anxiety in the college Japanese language classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 85, 549–566. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00125

Kondo, D. S., and Yang, Y. L. (2004). Strategies for coping with language anxiety: The case of students of English in Japan. ELT J. 58, 258–265. doi: 10.1093/elt/58.3.258

Krashen, S. D. (1987). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall International.

Liu, M., and Jackson, J. (2008). An exploration of Chinese EFL learners’ unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 92, 71–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00687.x

Lynch, S., Gander, M., Kohls, N., Kudielka, B., and Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based coping with university life: A non-randomized wait-list-controlled pilot evaluation. Stress. Health 27, 365–375. doi: 10.1002/smi.1382

Mabrour, A., and Mgharfaoui, K. (2011). “The (non)native teacher: Motivations and representations. Case of language teaching/learning in institutions in Morocco” in The nonnative teacher: Identities and legitimacy in the teaching and learning of foreign languages. eds. V. Badrinathan and F. Dervin. Editions Modulaires Européennes & Intercommunications.

MacIntyre, P. D. (1995). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. Mod. Lang. J. 79, 90–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05418.x

MacIntyre, P. D., Babin, P. A., and Clément, R. (1999). Willingness to communicate: Antecedents and consequences. Commun. Q. 47, 215–229. doi: 10.1080/01463379909370135

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1991). Language anxiety: Its relation to other anxieties and top-processing in native and second languages. Lang. Learn. 41, 513–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1991.tb00691.x

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Lang. Learn. 44, 283–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01103.x

MacKean, G. (2011). Mental health and well-being in postsecondary education settings. In CACUSS preconference workshop on mental health. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.737.6978&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed December 30, 2024).

Matsuda, S., and Gobel, P. (2004). Anxiety and predictors of performance in the foreign language classroom. System 32, 21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2003.08.002

Milhaud, M. (2024). Enquête sur l’anxiété en classe de FLE. Université Hankuk des ÉtudesÉtrangères. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313779274_Enquete_sur_l%27anxiete_en_classedeFLE. (Accessed January 28, 2025)

Mills, N., Pajares, F., and Herron, C. (2006). A reevaluation of the role of anxiety in second language learning. Lang. Learn. 56, 573–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2006.tb02266.x

Peña-Acuña, B., and Crismán-Pérez, R. (2022). Projected reading versus actual consumption of narrative formats in L1 Spanish university students. Investigaciones Sobre Lectura 17:129. doi: 10.24310/isl.vi18.14308

Phillips, E. M. (1992). The effects of language anxiety on students’ oral test performances and attitudes. Mod. Lang. J. 76, 14–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1992.tb02573.x

Price, M. L. (1991). “The subjective experience of foreign language anxiety: Interviews with highly anxious students” in Language anxiety: From theory and research to classroom implications. eds. E. K. Horwitz and D. J. Young (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall), 101–108.

Rice, K. G., Vergara, D. T., and Aldea, M. A. (2006). Cognitive-affective mediators of perfectionism and college student adjustment. Personal. Individ. Differ. 40, 463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.011

Rogers, H., and Maytan, M. (2012). Mindfulness for the next generation: Helping emerging adults manage stress and lead healthier lives. USA: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M. E., Schulman, P., and Tryon, A. M. (2007). Group prevention of depression and anxiety symptoms. Behav. Res. Ther. 45, 1111–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.010

Song, Y., and Lindquist, R. (2015). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress, and mindfulness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 35, 86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.06.010

Teimouri, Y., Goetze, J., and Plonsky, L. (2019). Second language anxiety and achievement: A meta-analysis. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 41, 363–387. doi: 10.1017/S0272263118000311

Wang, D., Guo, D., Song, C., Hao, L., and Qiao, Z. (2022). General self-efficacy and employability among financially underprivileged Chinese college students: The mediating role of achievement motivation and career aspirations. Front. Psychol. 12:719771. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719771

Yan, J. X., and Wang, P. (2001). The impact of language anxiety on students’ Mandarin learning in Hong Kong. Lang. Teach. Res. 6, 1–7.

Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does the anxiety research suggest? Mod. Lang. J. 75, 426–439. doi: 10.2307/329492

Keywords: foreign language, language anxiety, future teacher, primary section, anxiety

Citation: Haroud S, Ouchaouka L and Saqri N (2025) Investigating the causes of language anxiety among future primary school teachers in foreign language classes. Front. Educ. 10:1510765. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1510765

Received: 13 October 2024; Accepted: 21 February 2025;

Published: 20 March 2025.

Edited by:

Raona Williams, Ministry of Education, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Elena Jiménez-Pérez, University of Malaga, SpainCopyright © 2025 Haroud, Ouchaouka and Saqri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samia Haroud, c2FtaWEuaGFyb3VkQGVuc2Nhc2EubWE=

†ORCID: Samia Haroud, orcid.org/0009-0004-8702-1943

Nadia Saqri, orcid.org/0000-0001-8057-0596

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.