94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ. , 17 February 2025

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1508411

This article is part of the Research Topic Inclusive Education in Intercultural Contexts View all 8 articles

The main characteristics of rural schools include their intercultural context and diversity, making them an inclusive reference. This diversity fosters positive relationships between the school and its environment, enhancing the teaching-learning process. This article presents partial results from a project by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain titled “Rural schools: a basic service for social justice and territorial equity in sparsely populated Spain” (PID2020-115880RB-100). Using stratified random sampling with proportional allocation, 101 rural schools in Aragon participated, represented by 61 teachers who provided data through the “Rural school and territorial dimension” questionnaire. The questionnaire gathered information on various educational projects implemented in collaboration with other institutions to promote territorial development and address the challenges and needs of rural areas. The results showed that 90.1% of the projects focus on developing collective identity and a sense of belonging, providing services to the community, fixing and/or rooting the population, and responding to shared needs. These findings highlight the role of rural schools in cultural integration, inclusion, and specific support to ensure that all students and their families feel valued and an integral part of the community.

The academic invisibility of education in rural areas is gradually diminishing, in proportion to the increase and improvement in research on the subject, both in Spain and globally (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Boix, 2020; Santamaría and Sampedro, 2020; Juárez, 2019; Sørensen et al., 2021). A recent systematic review (Fargas-Malet and Bagley, 2021) identifies five key areas of research in rural education: the contextual, which includes the conceptualization of “rural” and issues related to educational policy and organizational-pedagogical models; the connection between school and community, covering the school’s role within its territory, the participation of families, local public administrations, local entities, and residents; the learning environment, with its successful educational practices, intercultural context, educational and social inclusion, and the impact of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT); leadership, through school management teams, continuous teacher training, and collaboration with other schools; and finally, educational equity and quality.

As noted, rural schools exhibit both strengths and challenges stemming from their distinct characteristics. Legislatively, rurality is underrepresented, and regulations are insufficiently tailored to this context (Alcalá and Castán, 2019; Lorenzo and Domingo, 2023). In terms of organizational-pedagogical models (Rural Grouped Schools, CRA, and Rural Innovation Educational Centers, CRIE), these are widely present in Spain and function as dual systems that combine educational and social aspects (Domingo and Nolasco, 2020). However, some schools are geographically isolated, suffering from digital deficiencies, teacher instability, and low student enrollment (Álvarez-Álvarez et al., 2020). A significant gap remains between the initial teacher training programs and the realities of multi-grade classrooms in rural schools (Azano et al., 2021). A similar issue is observed in continuous teacher training (Monforte García et al., 2024), where there has been an increase in training activities related to multi-grade teaching, but these remain insufficient. Thus, it is essential to require specific training to effectively address teaching-learning processes in rural contexts, adapting pedagogical and didactic strategies accordingly. Furthermore, rural schools are increasingly affected by the intensified depopulation process in rural Spain (Government of Spain, 2020; Moreno-Pinillos, 2022).

Despite the challenges, some characteristics of rural schools, such as smaller student-teacher ratios and multi-grade settings, allow for more personalized learning environments. These foster real cooperation, peer support, and positive synergies between older and younger students (Murillo, 2007; Hamodi and Aragués, 2014), which encourage innovative projects that promote critical thinking among students.

Moreover, rural schools establish close relationships between teachers, students, and families, which fosters greater collaboration and commitment to school activities (Azano et al., 2020). Several authors (Bagley and Hillyard, 2015; Lorenzo et al., 2019) also highlight the strategies employed by school management teams and teachers (Álvarez and Vejo, 2017; García and Pozuelos, 2017) in rural schools to establish fluid relationships between the school and the community. This interaction operates in two directions: when teachers recognize and involve the community in school life (Vigo and Soriano, 2015), and when the school engages with the community (Sales et al., 2017). Thus, rural schools share a common trait—their relationship with their territory and commitment to local communities (Moreno-Pinillos, 2022). They are also perceived as cultural hubs and drivers of local development (Tomazzoli, 2020). The closure of a school can accelerate the loss of public services in a locality, leading to a significant decline in economic and social growth (Juárez, 2019; Sørensen et al., 2021).

According to Sánchez (2019), exploring the use of digital technology as a means to combat depopulation, reduce isolation, and bridge the digital divide faced by rural schools compared to urban schools (Carrete-Marín and Domingo-Peñafiel, 2021) is crucial. This approach could create networking opportunities among teachers, students, and community stakeholders, strengthening the sense of belonging, attachment to the territory, and a shared identity (Del Moral and Villalustre, 2011), which would positively impact rural areas.

Consequently, schools play a vital role in rural areas by creating conditions for educational equity, positioning themselves as key components for the development and sustainability of rural communities (Cedering and Wihlborg, 2020). Therefore, it is important to analyze the projects in which rural schools collaborate with various local entities and determine their role in revitalizing the territory.

The scientific literature on interculturality, diversity, and inclusion is also expanding (Cernadas Ríos et al., 2021; Tomé-Fernández et al., 2024), but remains more limited when applied to Spanish rural schools (Álvarez-Álvarez and García-Prieto, 2022). According to Paniagua (2006), respecting and prioritizing heterogeneity in the classroom is the foundation for fostering meaningful learning. Bustos (2010) highlights how attention to interculturality and diversity is inherent in rural schools, given their highly heterogeneous composition, including students from diverse backgrounds, ages, interests, expectations, and educational needs. Domingo (2012) similarly argues that these schools value interculturality and diversity, offering opportunities that meet the needs of all students while promoting differences and emphasizing ‘the value of commonality’ in the teaching-learning process. These characteristics enable the holistic development of students and active participation from everyone involved.

The groupings in rural schools create spaces where the particularities of each student can be addressed in a pluralistic context. The small student-to-teacher ratio fosters positive relationships between students of different ages, where younger students learn from the experiences of older students, consolidating knowledge, skills, and competencies, and enhancing the sense of belonging to a collective project (García-Prieto and Pozuelos, 2015). As a result, intercultural students or those with educational needs are supported equally and are backed by their peers (Díaz Cayuela, 2019). Matías Solanilla and Vigo Arrazola (2020) emphasize how these groupings promote educational inclusion, peer mentoring, cooperative learning, and entrepreneurial spirit, all while respecting the unique characteristics of students in multi-grade rural classrooms.

Consequently, the diversity of contemporary society, shaped by significant migration flows that have brought a variety of cultures and backgrounds to rural areas (Collantes et al., 2010; Kalantaryan et al., 2021), must be addressed by schools. These institutions play a crucial role in fostering participation in initiatives that meet the educational needs of rural populations while upholding the principles of equity and equal opportunities (Sepúlveda and Vergara, 2021). Rather than being isolated entities, rural schools serve as essential pillars of sustainability and territorial cohesion (Rubio, 2020).

This study analyzes the role of rural schools in their territories and highlights their contribution as elements of social cohesion and as generators of rural social and economic capital. The research is part of a project funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain, titled “Rural Schools: A Basic Service for Social Justice and Territorial Equity in Underpopulated Spain” (PID2020-115880RB-100). The analysis is focused on Aragón, one of the regions with the highest percentage of students enrolled in rural schools.

To analyze the role of rural schools in Aragon as key agents in the social, economic and cultural development of the territory, with emphasis on their relationship with interculturality, inclusion and territorial equity.

Describe the main characteristics of the participating teachers and the rural schools in which they taught.

Describe the educational projects in which rural schools in Aragón collaborate with local authorities.

To identify the factors influencing rural teachers’ perceptions of the success of rural schools in establishing meaningful networks with local agents and the rural community to lead the development of the territorial dimension.

This research was conducted using a descriptive, non-experimental, and quantitative design.

A stratified random sampling with proportional allocation was applied, resulting in the participation of 101 rural schools in Aragón, represented by 61 teachers from early childhood, primary, and secondary education in the provinces of Huesca, Teruel, and Zaragoza. The self-reported gender of participants was 65.6% women, 32.8% men, and 1.6% transgender women.

Descriptive statistics for age, years of teaching experience, and years of teaching in rural schools are presented in Table 1. The data show that, on average, the participants have been working as teachers for around 14 years, most of which have been in rural schools. As mentioned in the introduction, the majority of the student population in rural schools in Aragón is highly diverse, particularly because many students come from other countries, making the rural areas of Aragón a model for cultural diversity.

The instrument used was the Rural School and Territorial Dimension Questionnaire (RSTD), 34 which is divided into two parts. The validation process demonstrated high reliability and consistency (α = 0.93). This process involved eight experts in rural education research, teacher training programs, and experienced teachers from rural schools.

The instrument (RSTD), 34, consisted of two parts:

The first was to collect data and information from respondents on the characteristics and environment of the school in which they taught. The second section of the research instrument was intended to collect information on the educational projects implemented, both ongoing and previously developed, in collaboration with the administration and local institutions. This section was subdivided into two parts. The first part aimed to obtain data on the number of projects carried out in each center, the approach adopted in their implementation, the process of execution of these and the level of satisfaction experienced by teachers when participating in these projects. The second part focused on analyzing the contribution of these projects to the local community and the territory in general. Most of this section consisted of multiple-choice questions and open-ended questions, with a smaller proportion requiring a response by rating on a Likert scale.

Data collection began in July 2022 with the distribution of an online survey to the principals of 101 rural schools in the Aragón region. The principals, who also taught classes in addition to managing the schools, were responsible for distributing the survey to the 61 participating teachers. A two-week deadline was set for survey completion.

Data analysis combined descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) with correlation tests (Pearson’s r) and inferential statistics. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess whether the variables met the assumption of normality. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v27 software, with the significance level set at p < 0.05.

In accordance with the objectives set, the results obtained in this research are presented below.

As shown in the Figure 1, the majority of participants held dual roles as members of the school management team and as teachers/tutors, with most employed under permanent contracts.

Figure 2 presents data on the type of schools, classroom structure, and educational stages, highlighting the prominence of CRA/CPR/CER schools, multi-grade classrooms, and primary education.

Table 2 presents the initial results regarding the educational projects carried out by schools in collaboration with local communities. Of the participants, 24 identified local authorities as the most prominent collaborators in educational projects conducted in their rural schools. Additionally, some participants considered that the primary collaborators were Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) (13 teachers, 21.3%) and companies (10 individuals, 16.4%).

Regarding the role played by the school in these collaborative projects, 25 of the 61 teachers (41.0%) noted that their schools had taken on a leadership role in implementing the projects, whereas 17 (27.9%) indicated that the schools had shown active collaboration. Similarly, in terms of the goals of the projects shared between the schools and local entities, 32 teachers (52.5%) identified School-Territory Needs as the primary goal, and 17 participants (27.9%) emphasized Service-Learning.

Finally, the goals of the shared projects between the school groups and the entities primarily focused on addressing Group-Territory needs, as indicated by 28 teachers (45.9%), while 16 participants (26.2%) identified Service-Learning as the main objective.

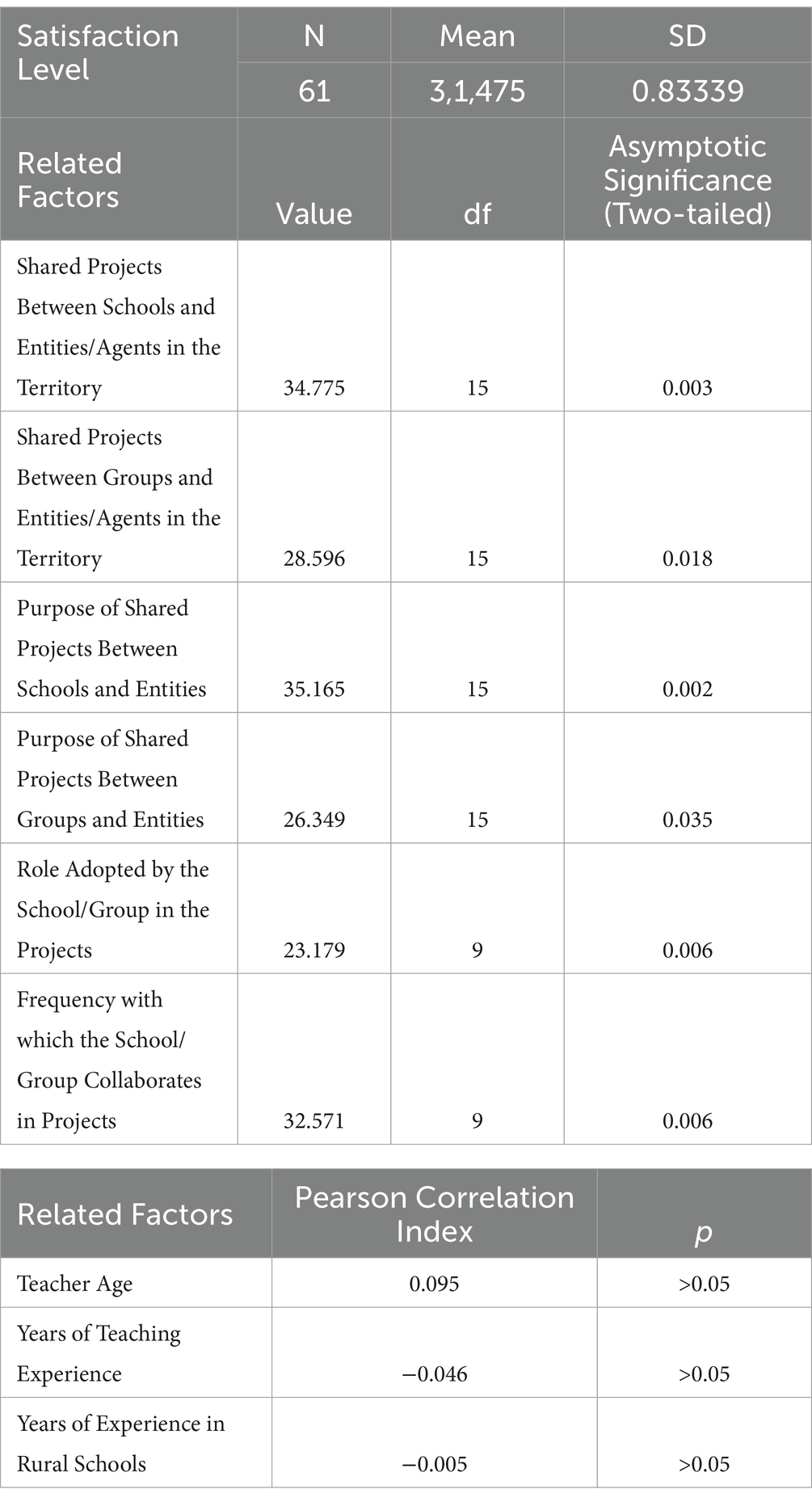

Table 3 indicates that the shared projects between schools, groups, and entities, as well as the role adopted by the institutions, have a significant relationship with the level of satisfaction of the respondents. However, factors such as the teachers’ age or years of experience do not appear to significantly influence this satisfaction. The following key points are presented:

Table 3. Shared projects between schools and entities/agents in the territory vs. level of satisfaction regarding collaboration.

The mean satisfaction score is 3.1475, with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.83339, indicating some variability in the responses. The bilateral asymptotic significance value (0.003) suggests significant differences in satisfaction levels concerning the mentioned factors.

For the shared projects between the schools and entities or agents in the territory, a value of 34.775 with 1 degree of freedom (df) and a significance level of 0.003 indicates a significant relationship between these projects and the level of satisfaction.

The statistical value is 28.536 with a significance of 0.018, indicating that collaboration with groups and entities has a significant relationship with the level of satisfaction.

With a value of 35.185 and a significance of 0.002, it is observed that the purpose of these projects is also a relevant factor for satisfaction.

Although it presents a lower value (23.173), it is also significant (0.009), suggesting that the role adopted by the school or group influences satisfaction.

The correlation between teacher age and satisfaction is 0.095 but is not significant (p > 0.05). The years of teaching experience show a negative correlation (−0.046), suggesting a slight tendency for greater experience to be associated with lower satisfaction; however, this finding is also not significant (p > 0.05). Additionally, the years of experience in rural schools do not significantly impact satisfaction (p > 0.05).

Table 4 shows that a significant proportion of respondents perceive the school as a key actor in network creation (37.7%). Additionally, there is a significant relationship between the perception of the educational community and the school as agents of change, and participation in networks. However, more experienced teachers, particularly those with experience in rural schools, tend to place less importance on this participation.

Below are some key findings:

• No participation: 4.9% of responses indicate that the school does not participate in network creation.

• Occasional and limited participation: 24.6% of responses suggest sporadic participation.

• Minimally relevant participation: 29.5% indicate that the school’s participation is of little relevance in network creation.

• Highly relevant participation: 37.7% of respondents view the school’s participation as highly relevant in this aspect.

• NS/NC (Not Sure/No Comment): 3.3% of respondents did not answer this question.

These results demonstrate that a substantial proportion of respondents (37.7%) view the school as an important actor in network creation; however, a significant number consider it to be less relevant or only participate sporadically.

Educational Community Valued as a Change Agent: The statistical value of 50.645, with a significance level of 0.048, suggests that the perception of the educational community as a change agent is significantly related to participation in network creation.

School Valued as a Change Component: A statistical value of 45.808, with a significance of 0.001, also indicates a significant relationship between the perception of the school as a change component and its participation in network creation.

Teacher Age: A negative correlation (−0.105), which is not significant (p > 0.05), suggests that age does not significantly impact perceptions of the school’s participation in networks.

Years of Teaching Experience: A negative correlation (−0.225), significant at p < 0.05, indicates that teachers with more years of experience tend to rate the school’s participation in network creation lower.

Years of Experience in Rural Schools: A negative correlation (−0.258), significant at p < 0.05, suggests that teachers with more experience in rural schools also tend to rate the school’s participation in networks lower.

This section is structured around the three specific objectives of the study: describing the characteristics of rural schools and their teaching staff, analyzing the educational projects developed in collaboration with local entities, and identifying the factors influencing the success of these initiatives. Each objective is discussed in detail, with evidence from the findings linked to relevant theoretical frameworks and prior research. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by rural schools and their potential to address the unique needs of their territories.

The results showed that most of the participants exercise roles as a member of the management team or as a teacher/tutor in the school and mostly their contractual situation is that of a civil servant. It was observed that according to the type of school, classroom organization and stages, the CRA/CPR/CER, Multigrade Classrooms and Primary Stage stand out.

The findings show that most teachers in rural schools in Aragón are highly experienced, with an average of over 13 years of teaching in these contexts. The participating schools are characterized by their multicultural environments, with students from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. These characteristics highlight the inclusive and heterogeneous nature of rural schools, which fosters a personalized teaching-learning process and a strong sense of belonging within the community.

Moreover, the smaller teacher-student ratio and the multigrade classroom structures provide unique opportunities for cooperative learning and peer mentoring. These features support the development of meaningful relationships between students, teachers, and families, contributing to a more cohesive and inclusive educational environment.

It agrees with Álvarez-Álvarez and Gómez-Cobo (2021) who found that teachers in rural schools in Spain tend to hold positions as civil servants or as interim staff. They often show a clear preference for rural areas and value advantages such as lower student-teacher ratios, the natural environment and flexible organizational structures. Many have previous experience in rural schools, which increases their appreciation for this educational environment. However, they face challenges due to limited initial university training specific to rural education, which impacts their adaptation and performance in these unique environments.

Despite the progress observed, gaps persist between the initial training of teachers and the specific demands of rural multigrade classrooms. This aspect confirms the observations made by authors such as Bustos Jiménez (2008), who underline the need for educational policies that address the specificities of the rural context, both in pedagogical and organizational terms. In addition, continuous training for the development of competences related to the territorial dimension remains a pending challenge (Boix and Buscà, 2020).

The results demonstrate that rural schools play a pivotal role in promoting territorial development through collaborative educational projects. Over 50% of the projects analyzed focused on addressing the shared needs of the territory, such as fostering collective identity, preserving local heritage, and providing community services. The collaboration with local authorities was identified as the most common and impactful form of partnership, with schools frequently assuming leadership roles in these initiatives.

Additionally, the projects emphasize service-learning as a key strategy to connect educational activities with the realities of the local community. By engaging students in solving local issues, these projects not only enhance learning outcomes but also contribute to the sustainability and development of rural areas. This alignment of educational objectives with territorial needs highlights the strategic importance of rural schools as agents of change.

According to the findings of this study, the correlation between teacher satisfaction and participation in shared educational projects highlights the need for active integration between schools and local communities, which has been pointed out in recent research (Grané and Argelagués, 2018; Champollion, 2018). Likewise, the frequency of collaboration is identified as a key factor for the sustainability and impact of these projects (Schafft, 2016).

The high cultural diversity present in these institutions represents both challenges and opportunities to foster meaningful learning and collective belonging (Domingo-Peñafiel, 2020; Beach et al., 2019). This approach is aligned with previous research that highlights the value of rural schools in the revitalization of their territories, as they act as engines of social cohesion and local development (Abós et al., 2021).

Teacher satisfaction with the collaborative projects was closely linked to the active roles they played, either as leaders or active participants. Teachers expressed higher levels of satisfaction when their schools were directly involved in initiating and leading the projects, as opposed to merely being recipients. This underscores the importance of empowering schools and teachers to take on leadership roles in territorial collaborations.

The impact of rural depopulation widely documented (Government of Spain, 2020), continues to represent a barrier to the consolidation of rural schools. The stability of teaching teams is essential to guarantee the continuity of educational projects and their impact on local communities. In this sense, collaborative networks between schools and local agents emerge as key strategies to overcome these challenges (Lorenzo Lacruz and Abós Olivares, 2021).

The study also identified challenges, such as the lack of stability in teaching staff and the limited availability of specific training programs tailored to the realities of rural schools. These factors were perceived as barriers to the successful establishment and sustainability of meaningful networks with local agents. Addressing these challenges through targeted policies and training programs is essential to enhance the long-term impact of these projects.

The discussion highlights the multifaceted role of rural schools as educational institutions and drivers of territorial development. By aligning their educational projects with the needs of their local communities, rural schools strengthen social cohesion, enhance intercultural inclusion, and contribute to the sustainability of their territories. The study emphasizes the importance of collaborative efforts between schools, local authorities, and other stakeholders to address the unique challenges and opportunities of rural education.

Rural schools are not only educational spaces, but also active agents of territorial development. The results of this study, together with previous research (Mosneaguta, 2019; Rodríguez et al., 2023), show how educational projects designed to respond to local needs can foster rootedness, strengthen social capital, and promote the sustainability of rural territories. This underscores the importance of a two-way approach in the implementation of these projects, where both schools and local communities have an active participation.

The teaching staff in rural schools in Aragón requires greater stabilization, as most educators are transient. This lack of permanence hinders the establishment of leadership roles and, consequently, stability. To promote a more inclusive rural school with a focus on multiculturalism, achieving stability and fostering leadership within the management team is essential. Such leadership ensures the continuity of multicultural projects that address community needs for coexistence and cultural richness, as rural territories and schools are inseparable.

The necessity of this inseparable connection between the rural school and the territory defines the school’s role as a catalyst for establishing relationships with local organizations. When the initiative originates from the school, rather than the external environment, teachers’ satisfaction levels increase—regardless of factors such as age or years of experience, which this study does not identify as significant influencers. Any initiative that stems from the school to enhance interculturality through cooperation with local administrations can serve as a valuable asset, fostering community participation and strengthening the fundamental bonds within an inclusive school and society.

Projects shared between rural schools and their surrounding communities contribute to higher teacher satisfaction, as these collaborations are perceived as valuable learning opportunities for students. Engagement with the local environment enriches the educational experience, making it more relevant and competency-based. Furthermore, any collaborative efforts with external organizations should prioritize interculturality, thereby creating a more inclusive school and territory.

Teachers value the objectives of shared projects with local agents and organizations. Thus, it is not merely about cooperating with local entities but about developing purposeful, competency-based, and socially relevant projects that promote civic engagement rooted in interculturality and inclusion.

Additionally, a significant proportion of teachers in Aragón’s rural schools perceive the school as a key agent in establishing networks with the surrounding community, capable of driving meaningful change. However, more experienced educators express greater skepticism in this regard. Inter-institutional collaboration is essential in rural areas, where schools often function as the central pillar of the community. The active involvement of local institutions, such as public administrations, NGOs, and businesses, reinforces the social fabric of rural regions.

The analyzed data underscore that rural schools in Aragón are intertwined with territorial and social dynamics. While local social agents and entities are involved, schools must facilitate projects that foster interculturality and maintain close ties with their territories. Most projects focus on community needs, respecting and integrating cultural diversity in rural schools.

Data on entrepreneurship and economic activity highlight the importance of promoting skills that foster entrepreneurship in rural areas, addressing structural issues like depopulation and lack of job opportunities. Service-learning projects connect education with the social realities of the community, allowing students to participate in solving local problems. This commitment to social engagement, combined with educational value, creates an effective approach aligned with principles of multiculturalism and inclusion. While rural schools often collaborate on projects, they rarely initiate them.

The fact that over half of the projects aim to meet community needs confirms the critical role of rural schools in bridging education and territorial development. Rural schools should be seen not only as educational institutions but also as local development agents capable of responding to the specificities of their territories and the needs of their populations, particularly in Aragón’s rural areas.

In summary, the findings highlight the value of inter-institutional collaboration in the rural regions of Aragón and its significance for the educational and social development of rural schools and their territories. It underscores the need for collaboration that promotes interculturality as both a value of inclusion and a necessity in rural communities.

Achieving this requires a multifocal perspective (social, economic, political, and educational) to understand the relationship between the territory and the rural school. A reductionist and fragmented viewpoint would lead to incomplete and biased conclusions. The relationship between rural schools and their territories is symbiotic (Domingo-Peñafiel, 2020), as they are inextricably linked, given the school’s role as a motor for local development and a generator of social and economic capital.

Recent advancements in pedagogical innovation in rural areas present opportunities for driving educational change. Rural schools are equipped to meet the challenges and demands of their specific contexts (Álvarez and Vejo, 2017) by adopting practices that engage with their students and communities. This approach requires teachers to be knowledgeable about and appreciative of the community’s traditions, values, and beliefs (Álvarez and Vejo, 2017). In this context, innovation aims at improvement, rooted in collaboration and commitment to the territory and its agents. This promotes democratic and cultural participation while fostering an identity that adapts to evolving local, national, and international realities.

Although this study is only a minimal part of a global study at the national level with a greater variety of instruments, for the results that have been obtained for this study we highlight the following limitations: -Sample limited to Aragón: Although the study covers a significant number of rural schools in Aragón, its findings cannot be directly extrapolated to other regions of Spain or international rural contexts with different characteristics. -Measurement instrument and self-reporting: The use of a questionnaire as the sole instrument may limit the depth of analysis, as the data relies on teachers’ subjective perceptions. Additionally, the self-reporting method may introduce cognitive biases or social desirability effects. -Absence of qualitative methods: While a robust quantitative approach was employed, incorporating interviews or focus groups could have enriched the analysis by providing a deeper understanding of teachers’ experiences and their relationship with educational projects.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

VD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project has been funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain titled “Rural schools: a basic service for social justice and territorial equity in sparsely populated Spain” (PID2020-115880RB-100).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abós, P., Boix, R., Domingo-Peñafiel, L., Lorenzo, J., and Rubio, P. (2021). El reto de la escuela rural: Hacer visible lo invisible. Barcelona: Graó.

Alcalá, M. L., and Castán, J. L. (2019). The origins of rural schools in Teruel: The creation of a school system in the 19th century. Sevilla: Caligrama.

Álvarez, C., and Vejo, R. (2017). How do Spanish rural schools position themselves regarding innovation? An exploratory study through interviews. Aula Abierta 45, 25–32. doi: 10.17811/rifie.45.2017.25-32

Álvarez-Álvarez, C., and García-Prieto, F. J. (2022). Policies implemented in rural schools: an international bibliometric analysis (2001-2020). Arch. Anal. Polít. Educ. 30:6660. doi: 10.14507/epaa.30.6660

Álvarez-Álvarez, C., García-Prieto, F. J., and Pozuelos, F. J. (2020). Possibilities, limitations, and demands of educational centers in rural areas of northern and southern Spain as viewed from school leadership. Perfiles Educ. 42, 94–106. doi: 10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2020.168.59153

Álvarez-Álvarez, C., and Gómez-Cobo, P. (2021). 2. La Escuela Rural: ¿un destino deseado por los docentes? Rev. Int. Form. Prof. 96:1507. doi: 10.47553/RIFOP.V97I35.2.81507

Azano, A. P., Brenner, D., Downey, J., Eppley, K., and Schulte, A. K. (2020). Teaching in rural places: Thriving in classrooms, schools, and communities. London: Routledge.

Azano, S., Vázquez, S., and Liesa, M. (2021). Analysis of initial training in rural schools in teacher education programs: evaluations and perceptions of students as involved agents. Tendencias Pedagógicas 37, 43–56. doi: 10.15366/tp2021.37.005

Bagley, C., and Hillyard, S. (2015). School choice in an English village: living, loyalty and leaving. Ethnogr. Educ. 10, 278–292. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2015.1050686

Beach, D., Johansson, M., Öhrn, E., Rönnlund, M., and Per-Åke, R. (2019). Rurality and education relations: metro-centricity and local values in rural communities and rural schools. Europ. Educ. Res. J. 18, 19–33. doi: 10.1177/1474904118780420

Boix, R. (2020). The territorial dimension of teacher training in Spain. Territorializat. Educ. Trend Necessity 5, 63–75. doi: 10.1002/9781119751755.ch4

Boix, R., and Buscà, F. (2020). Competencias del Profesorado de la Escuela Rural Catalana para Abordar la Dimensión Territorial en el Aula Multigrado. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio En Educación 18, 115–133. doi: 10.15366/reice2020.18.2.006

Bustos, A. (2010). Approaching rural school classrooms: heterogeneity and learning in multigrade groups. Rev. Educ. 352, 353–378. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-0034-8082-RE

Bustos Jiménez, A. (2008). Docentes de escuela rural. Análisis de su formación y sus actitudes a través de un estudio cuantitativo en Andalucía. Rev. Invest. Educ. 26, 485–519.

Carrete-Marín, N., and Domingo-Peñafiel, L. (2021). Technological resources in multigrade rural classrooms: a systematic review. Rev. Brasileira Educ. Campo 6, 1–31. doi: 10.20873/uft.rbec.e13452

Cedering, M., and Wihlborg, E. (2020). Village schools as a hub in the community. A time-geographical analysis of the closing of two rural schools in southern Sweden. J. Rural. Stud. 80, 606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.09.007

Cernadas Ríos, F. X., del Lorenzo Moledo, M., and Ángel Santos Rego, M. (2021). Intercultural education in Spain (2010-2019): a review of research in scientific journals. Publications 51, 329–371. doi: 10.30827/publicaciones.v51i2.16240

Champollion, P. (2018). Inégalités d’orientation et territorialité: l’exemple de l’école rurale montagnarde. París: Cnesco.

Collantes, F., Pinilla, V., Sáez, L. A., and Silvestre, J. (2010). The demographic impact of immigration in depopulated rural Spain. Boletín Elcano 128, 1–28.

Del Moral, M. E., and Villalustre, L. (2011). Communities of practice in web 2.0 for collaboration between rural schools. Didáct. Innov. Mult. 20, 1–8.

Domingo, V., and Nolasco, A. (2020). “Educational tandem in the province of Teruel (Spain): grouped rural schools (CRA) and rural centers for educational innovation (CRIE)” in Retos socio-político-psicológicos de la educación. ed. K. J. Gherab (Madrid: GKA), 221–232.

Domingo-Peñafiel, L. (2020). Escola rural i territori: una simbiosi clau. Temps d'Educació 59, 7–9. doi: 10.1344/tempseducacio2020.59.1

Fargas-Malet, M., and Bagley, C. (2021). Is small beautiful? A scoping review of 21st-century research on small rural schools in Europe. Europ. Educ. Res. J. 21, 822–844. doi: 10.1177/14749041211022202

García, F. J., and Pozuelos, F. J. (2017). The integrated curriculum: work projects as a global proposal for an alternative rural school. Aula Abierta 45, 7–14. doi: 10.17811/rifie.45.2017.7-14

García-Prieto, F. J., and Pozuelos, F. J. (2015). A community proposal for education in rural areas. Cuad. Pedag. 459, 46–50.

Government of Spain. (2020). The demographic challenge and depopulation in figures. Madrid: Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge.

Grané, P., and Argelagués, M. (2018). Un modelo de educación comunitaria para la mejora de las relaciones entre las familias, escuelas y comunidades: revisión de las experiencias locales en Cataluña, Comunidad de Madrid, Comunidad Valenciana y Canarias. Profesorado Rev. Curríc. Formación Prof. 22, 51–70. doi: 10.30827/profesorado.v22i4.8394

Hamodi, C., and Aragués, S. (2014). The rural school: advantages, disadvantages, and reflections on its false myths. Palabra 14, 46–61.

Juárez, D. (2019). Policies for closing rural schools in Ibero-America: Debates and experiences. Nómada: Thematic Research Network on Rural Education.

Kalantaryan, S., Scipioni, M., Natale, F., and Alessandrini, A. (2021). Immigration and integration in rural areas and the agricultural sector: an EU perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 88, 462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.04.017

Lorenzo, J., and Domingo, V. (2023). “The school in rural contexts: contemporary regulations and school organization” in La escuela y su organización: análisis y retos. eds. J. Cano and A. Cebollero (Dykinson), 115–133.

Lorenzo, J., Domingo, V., Nolasco, A., and Abós, P. (2019). Analysis of educational leadership at rural early-childhood and primary schools: a case study in Teruel (Aragon, Spain). Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 22, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2019.165759

Lorenzo Lacruz, J., and Abós Olivares, P. (2021). Escuela rural y territorio: Análisis de buenas prácticas educativas en el contexto de la comunidad autónoma de Aragón (España). Rev. Espaço Curr. 14, 1–21. doi: 10.22478/ufpb.1983-1579.2021v14n2.58080

Matías Solanilla, E., and Vigo Arrazola, B. (2020). The value of place in inclusion and exclusion relationships in a grouped rural school: an ethnographic study. Márgenes, Rev. Educ. Univ. Málaga 1, 90–106. doi: 10.24310/mgnmar.v1i2.8457

Monforte García, E., Edo Agustín, E., Domingo Cebrián, V., and Ramo Garzarán, R. M. (2024). Pre-service and in-service teacher training for rural schools: a dual perspective of rural teaching. ENSAYOS, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete 39, 74–90.

Moreno-Pinillos, C. (2022). School in and linked to rural territory: teaching practices in connection with the context from an ethnographic study. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 32, 19–35. doi: 10.47381/aijre.v32i2.328

Mosneaguta, M. (2019). The impact of a global education program on the critical global awareness level of eighth-grade students in a rural School in South Carolina (Tesis doctoral). Carolina: University of South Carolina.

Murillo, J. L. (2007). Does the rural school exist? Aula Libre, por una práctica libertaria en la educación 85, 6–8.

Paniagua, A. (2006). Counterurbanisation and new social class in rural Spain: theenvironmental and rural dimensions revisited. Scott. Geogr. J. 118, 1–18.

Rodríguez, J., Marín, D., López, S., and Castro, M. M. (2023). Tecnología y Escuela Rural: avances y brechas. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 21, 139–157. doi: 10.15366/reice2023.21.3.008

Rubio, P. (2020). “Rurality, territory, and school” in El reto de la escuela rural. Hacer visible lo invisible. eds. P. Abós, R. Boix, L. Domingo, J. Lorenzo, and P. Rubio (Barcelona: Grao), 12–23.

Sales, A., Moliner, O., and Lozano, J. (2017). Strategies to link schools to their territories. A survey study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 237, 692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.044

Sánchez, F. (2019). Rural blended education: a semi-presential education project to curb depopulation in rural areas. 3C TIC. Cuadernos de desarrollo aplicados a las TIC 8, 74–95. doi: 10.17993/3ctic.2019.81.74-95

Santamaría, N., and Sampedro, R. (2020). The rural school: a review of the scientific literature. Rev. Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 30, 153–176. doi: 10.4422/ager.2020.12

Schafft, K. A. (2016). Rural education as rural development: understanding the rural school–community well-being linkage in a 21st-century policy context. Peabody J. Educ. 91, 137–154. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2016.1151734

Sepúlveda, Á. A. R., and Vergara, M. (2021). The rural school facing urban expansion: conflicts and opportunities. Educ. Educ. 24, 71–90. doi: 10.5294/educ.2021.24.1.4

Sørensen, J. F. L., Svendsen, G. L. H., Jensen, P. S., and Schmidt, T. D. (2021). Do rural school closures lead to local population decline? J. Rural. Stud. 87, 226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.016

Tomazzoli, E. (2020). Traveling between mountains, countryside, and small islands: Italian rural primary schools as engines for community development. Temps d’Educació 59, 91–108.

Tomé-Fernández, M., Aranda-Vega, E. M., and Ortiz-Marcos, J. M. (2024). Exploring social skills in students of diverse cultural identities in primary education. Societies 14:158. doi: 10.3390/soc14090158

Keywords: rural schools, cultural integration, territorial dimension, inclusion, Aragon

Citation: Domingo Cebrián V, Nolasco Hernández A, Lorenzo Lacruz J and Gracia Sánchez L (2025) The Aragonese rural school in intercultural contexts: a basic of social justice and territorial equity in resilient Spain. Front. Educ. 10:1508411. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1508411

Received: 09 October 2024; Accepted: 20 January 2025;

Published: 17 February 2025.

Edited by:

Jie Zhang, SUNY Brockport, United StatesReviewed by:

José Eugenio Rodríguez-Fernández, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainCopyright © 2025 Domingo Cebrián, Nolasco Hernández, Lorenzo Lacruz and Gracia Sánchez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Virginia Domingo Cebrián, dmRvbWluZ29AdW5pemFyLmVz

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.