94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 25 March 2025

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1496609

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvancing inclusive education for students with special educational needs: Rethinking policy and practiceView all 11 articles

This study’s background is the lack of research and knowledge about special education in Sweden’s School-Age Educare Centers (SAEC), focusing on extra adaptations and special support. The study is important for international educational research because it draws attention to a research area that is lacking. Additionally, out-of-school programs are beginning to question and develop the field of special education. The study aimed to determine to what extent staff of various professional groups support students in need of special support and extra adaptations in SAEC. It is based on a web survey with 412 responses from SAEC staff. The empirical material was analyzed with descriptive and inferential statistics. As a theoretical frame, we used the relational perspective. The result shows that various professional groups have different and distinctive perceptions of students needing special support and extra adaptations in SAEC, especially the principals. Another result was that few students have action programs in SAEC. The results suggest that the students do not receive the special educational support needed to attain sufficient development and learning in the SAEC, which does not meet the governing documents for the SAEC. This study makes an important contribution for all professionals in SAEC (or internationally similar after-school settings) because staff is predicted to receive increased importance in the SAEC to compensate and supplement schools. Implications for practice are the need to allocate resources to implement the special education reform, prioritize SAEC and support staff in the implementation.

Worldwide, after-school care includes various programs for students aged 6–13 before and after school, differing by country. In the US, there are after-school programs; in Japan, extracurricular programs; in Germany and Switzerland, all-day schools; in Australia and England, school-age care; and Sweden, School-Age Educare Centers. These programs support learning, social development, and meaningful leisure time. They help parents balance work and parenting, contributing to family stability. For society and students, they enhance educational outcomes and foster a safe, cohesive community (Plantenga and Remery, 2017).

This article focuses on Swedish SAEC, which is part of the Swedish school system. In Sweden, most students (almost 90%) aged 6–9 attend SAEC, before and after school as well as during holidays. It has its own curriculum, focusing on both personal development and supplementing academic subjects. Activities often include arts, sports, crafts, and problem-solving tasks that encourage collaboration and independence. This comprehensive approach helps students learn in a playful manner. SAEC works closely with schools to ensure seamless integration of learning objectives, promoting continuity in the child’s overall education. SAEC also play a crucial role in promoting equity, as all students, regardless of background, have access to these services at a minimal cost. In Sweden, SAEC must adhere to the national curriculum (part 4), particularly the section outlining goals for SAEC, which emphasizes social development, creativity, and complementing formal education (Skolverket, 2023).

Since SAEC aligns with the regular school curriculum, the interest is how the staff in SAEC expresses how they can meet students’ different needs. In Sweden, there is a special teacher training program for SAEC teachers for 3 years. In the past, the academically trained personnel were called leisure pedagogues but were changed to SAEC-teacher 2001. There is a requirement for at least one trained SAEC-teacher per SAEC. SAEC-teachers usually lead the pedagogical work for the staff. There is a wide variation in the formal competence of the staff. In 2023, 39.4% had the intended training (Skolverket, 2023). Other groups working in SAEC include childminers, assistants, and people who have no post-secondary education at all. SAEC-teachers often share their working time in SAEC and primary school because they are usually authorized to teach up to grade 6 in, for example, sports or art.

There is a growing international knowledge base on education’s conditions for learning, focusing on children’s social and cognitive development outside school, related to SAEC in Nordic countries and similar settings (Haglund and Peterson, 2017). Plantenga and Remery (2017) describe educational care infrastructures in 33 EU countries, with Sweden leading in accessibility and quality. Kirkpatrick et al. (2019) discuss SAEC equivalents in the US, and Hurst (2019) highlights after-school centers in Australia. While there are similarities between Swedish SAEC and these counterparts, differences exist in staffing, governing documents, and supervision. The first comprehensive Swedish research overview (Skolforskningsinstitutet, 2021) concludes that providing meaningful leisure and promoting development requires a strategy to create creative environments and varied teaching situations.

Since many students are shown in after-school-like environments before and after school, the staff also meet students needing special educational support there. An important question is what competencies staff have in handling special educational questions and whether there are resources in the organization to meet students with different needs. In Sweden, the SAEC has both a supplementary and a compensatory assignment according to The education act (SFS 2010:800, n.d.), which means that SAEC has an important role in enhancing student’s learning from an all-day perspective (Skolverket, 2023). In addition, the SAEC teachers are responsible for meeting students’ needs (Skolverket, 2014) and assessing which students need extra adaptations and special support and what teaching is required. SAEC—teachers are responsible for meeting students’ needs, but individual solutions for students can be problematic since SAEC is not a compulsory part of the school system, and the foundation of the SAEC is participation, togetherness, and community (Wernholm, 2023a). This means that there may be an inherent conflict in singling out individual students’ needs as it goes against the inclusive ideal of SAEC programs that emphasize collective values such as teaching as a group and not assessing individual student’s achievements. Ultimately, the principal is responsible for the SAEC staff planning and teaching based on current governing documents (Skolverket, 2023). The SAEC has an important role in all students’ development and learning and should, according to Lundbäck (2022), be strengthened by initiating and developing special educational issues based on the mission of the SAEC.

Two basic concepts within special education in the Swedish context and also adaptable in SAEC, whose meaning is mandatory, are extra adaptations and special support. Extra adaptions mean less intrusive support measures that can be made within the framework of regular teaching. Extra adaptations and special support are individual-oriented and are introduced when a student needs to develop in the direction of the knowledge goals in the curriculum or toward reaching the minimum knowledge requirements that must be achieved. Extra adaptations are less intrusive support efforts compared to special support and are about making teaching more accessible to the student in different ways. The SAEC program can be about visual support or support for students in their play. If extra adaptations are insufficient, the student’s need for special support must be urgently investigated, and the principal must decide how the special support will be offered, for example, as an action program. Special support is a more intrusive support measure. For example, the student is taught in a different place, which requires a formal decision, and the measure is documented in various ways (Skolverket, 2024b).

These concepts are enshrined in The education act (SFS 2010:800, n.d.) and specified in the curriculum (Skolverket, 2014). They must be implemented in regular teaching (Skolverket, 2014, 2023). Thus, teachers and principals must ensure that students receive extra adaptations and special support in teaching. Support for students in need of special support must be provided throughout the school day and in SAEC. According to the Swedish Education Act, students in need of support must be reported to the principal, and an investigation needs to occur immediately. A mapping or pedagogical investigation of students’ needs and learning environment must be done. Thereafter, an action program must be presented with special educational support measures (SFS chapter 3 §5–9). In the academic year 2023/24, 6.2 percent of primary school students are covered by an action program, corresponding to just under 68.600 students (Skolverket, 2024a). Despite this injunction, the knowledge about how many students have an action program written and adapted for SAEC is deficient.

Previous research has also shown that knowledge about how to work with extra adaptions and special support is low among SAEC staff (Boström et al., 2024).

In 2023, the Swedish school inspectorate (2024) investigated schools and SAEC’s work with extra adaptions and special support during students’ whole day. The results show that there is a risk that students will not gain the support they have a right to have because needs reported to the principal are only sometimes followed up. Further competencies needed to be improved; SAEC was not a part of the school’s support work, and their competencies were often neglected.

Despite the mandates of the Swedish education act, there is insufficient knowledge about the number of students with action programs specifically adapted for SAEC. Additionally, previous research indicates that SAEC staff have limited knowledge of implementing extra adaptations and special support. This gap in understanding and practice highlights the necessity for targeted research on specialized pedagogic support within SAEC, which is the primary focus of the present study.

The study aims to determine to what extent staff, consisting of various professional groups, describe how they support students in need of special support and extra adaptations in SAEC.

• RQ 1. How do staff perceive special support and the handling of it?

• RQ2. How do staff value different aspects of support for students in need of special support in SAEC?

• RQ 3. Are there differences within professional groups? If so, how?

Students’ need for support in SAEC settings is almost not researched at all in a Swedish context (Lundbäck, 2022; Skolinspektionen, 2024a; Skolinspektionen, 2024b) and internationally (After-school Alliance, 2014; Lundbäck and Fälth, 2019), which made us reflect on the SAEC-staff’s view of the work with extra adaptations and special support. Therefore, we believe that this study is of good relevance to policy actors and researchers in other countries who are actively reviewing, improving, or reforming SAEC programs, especially considering that Sweden is seen as a forerunner and is high in the international ranking regarding SAEC (cf. Plantenga and Remery, 2017).

Research on special education in the SAEC environment is scarce (Andishmand, 2017; Göransson et al., 2015), and interventions are largely non-existent (Boström et al., 2024). Some studies deal with specific functional variations in SAEC, such as visual and hearing impairments (Engel-Yeger and Hamed-Daher, 2013), physical disability (Finnvold, 2018), and disabilities in general (Parish and Cloud, 2006). One meta-analysis that takes a broader approach is Cirrin and Gillam (2008), who reviewed research regarding language interventions with children in kindergarten, first grade, and after-school care and found relatively little evidence supporting the language intervention practices being used with school-age students with language disorders. On the other hand, a study (Martínez-Álvarez, 2017, 2019) addresses concepts for expanding the educational involvement of bilingual students with language disabilities perceived as potentially in need of special education services. It shows how bilingual students in after-school care settings, who may be considered to need special educational interventions, learned science via digital tools. Martinez-Alvarez named the concept multigenerational learning.

Other important research findings that describe what functions are needed to adequately cater to school-age students with disabilities in childcare and other environments outside of school are described by Jinnah-Ghelani and Stoneman (2009). The adaptations encompassed modifications to the physical environment and activities, strategies to enhance socialization with peers, staff training to manage these adaptations, ensuring student safety, and maintaining clear communication with parents regarding the appropriate treatment of student. An even broader international perspective on students in need of support and after-school programs in the USA is described by Haney (2012) and specific diagnosed with autism whose parents claim that the children do not receive the support they need. On the other hand, Yamashiro (2021) points out that most parents of children in need of special support are very satisfied with the after-school experience. Regarding the situation in Germany, Ahrbeck et al. (2018) question whether it is even possible to educate all children with and without disabilities together in the same setting.

Research in the Nordic countries in this field is also sparse. Even the research area that deals with students’ need for support in SAEC teaching in Sweden is little explored (Lundbäck, 2022; Skolinspektionen, 2024a; Skolinspektionen, 2024b). Two studies highlight that students in SAEC who are in need of extra support but do not always get it are often unable to access it (Karlsudd, 2020; Wernholm, 2023b). A troubling circumstance is a lack of overall statistics on the number of students in SAEC who is in need of extra support (SOU 2022:61, n.d.; SOU 2020:34, n.d.). Lundbäck (2022) emphasizes the importance of SAEC staff competence in critically evaluating activities to identify where students require special support. The SAEC teachers should know how SAEC promotes and supports all students’ learning and development and that the problem should not be placed on the individual student.

The opportunities for after-school programs to meet the needs of all students can be related to the conditions that prevail in the organization. In an ethnographic study, Lager (2015) focused opportunities and obstacles in Swedish SAEC and revealed a wide variation in the staff’s level of education, local conditions, available materials, and time for planning. This ultimately creates different conditions for the SAEC activities. In their research review, Boström and Grewell (2020) showed that physical learning environments in SAEC are varied, often undersized, and poorly adapted for after-school activities. For example, they can be characterized by crowding, which negatively affects students’ learning and concentration. Inadequate premises can also make activities more structured and adult-controlled (Boström and Augustsson, 2016). In a qualitative survey, Elvstrand et al. (2022) investigated how staff in SAEC describe their work on making activities accessible to all students. The results show that the staff have a strong ambition to work inclusively, but various support forms are uncommon. Furthermore, it emerges that few are offered guidance or special educational support, and the resources are often perceived as insufficient.

Concerning the mandatory special educational concepts in SAEC, extra adaptions, and special support, one study shows these concepts are visible differently. The concepts are unclear to the staff, and they mix them up, making adaptations more or less consciously and using different artifacts and working methods (Boström et al., 2024). The results also indicate that the realization of the concept has not spread in the SAEC.

A survey that focused explicitly on extra adaptations and special support was carried out by Sweden’s Teachers Union (Sveriges Lärare, 2023) for 1 week and was based on approximately 400 responses. One survey result was that only 37% of the students considered to be in need of special support, received this. Another was that many students are not given special support and that it varies widely between different SAECs whether support is given.

In this study, we take our starting point from the relational perspective. It is a special educational perspective that focuses on the relationship between the environment and those in it. It is usually opposed to the categorical perspective, which has a psycho-medicine connection where the individual’s characteristics are the basis for any measures (Haug, 1998). We have chosen the relational perspective because many formulations in the Swedish curriculum can be derived from a relational perspective.

In this perspective, school problems are attributed to the school’s organization and activities (Ahlberg, 2009; Skrtic, 1995; Haug, 1998). In the relational perspective, the term students in need of special support is used. Problems that arise for students must be identified, and solutions must be offered with a focus on the learning environment and learning situations. It is particularly important in this personal assessment that the entire school staff reflects on how teaching is organized and how special education teaching takes place. Ahlberg (2009) makes it clear that from this perspective, school difficulties are described with a focus on the relationship and interaction in the learning environment. The learning environment must be adapted to create good learning situations for students needing support, not vice versa. It is the responsibility of the staff to design learning situations in such a way that the difficulties experienced by the student are addressed with possible solutions (or alternative approaches). It is the staff’s responsibility to create the learning situation so that what the student experienced as difficulties has possible solutions (or alternative approaches). In this way, the teacher takes responsibility for the learning situation and lifts the responsibility from the student’s shoulders.

The concepts of “extra adaptations” and “special support” fit well with the relational perspective because this perspective focuses on the interaction between the individual and the environment rather than seeing problems and solutions solely as the individual’s responsibility. It is about adjusting the environment, the teaching, or the support system to better meet the needs of the students who need special educational support.

Since the study focuses on special education, several different theoretical frameworks could be used. A possible alternative theoretical lens could have been system theory from a social-constructionist perspective (Rapp and Corral-Granados, 2024), which could have shed light on underlying mechanisms that create inclusion at different institutional levels. This was not chosen because the study is close to practice.

This study is based on a web survey sent out to various networks and social media in autumn 2023 with the SAEC staff as stakeholders. Data were collected using a web-based survey administered via a link to the survey tool Netigate.1 Responses were received from 412 people; 102 (21%) were men, and 390 (79%) were women, which reflects quite well the gender balance in Swedish SAEC. The study followed the Swedish Research Council’s guidelines. And ethical recommendations for studies in social science research (Vetenskapsrådet, 2017). An introductory text described the study, and that participation was voluntary and anonymous. The respondents gave their consent by answering the questionnaire. Initially, they stated their current professional position as SAEC teachers, SAEC pedagogues, SAEC leaders, principals, childminders, teacher students, assistants, and the category “other.” The criteria for selecting professional services were based on the most common professions in SAEC. According to the data presented in Table 1, approximately 40% of the staff in School-Age Educare Centers (SAEC) are teachers, around 30% are pedagogues/leaders, and 12% are principals. Other staff members account for just over 20%, indicating that a minority lacks formal educational training for SAEC. For those with a teaching degree, some teaching related to special education is included. Among the 412 respondents, it was not possible to deduce how many had a special education teacher degree.

This sub-study has a quantitative approach. The survey consists of both open-ended and fixed answers for SAEC staff. The survey consisted of four themes. The first was background variables such as age, gender, occupational category and number of years in the profession. The second theme was about the SAEC where they worked at and extra adaptations and special support as well as action programs, in total 10 open ended questions and 5 with fixed responses. The third theme was about special pedagogy and after-school pedagogy, a total of eight open-ended question. The fourth theme consisted of 14 questions with fixed responses about extra adaptions och special support and one open question to comment on the answers. The aim was to determine how the various professional groups meet students in need of extra support, what adaptations are made, and to distinguish perceptions between the groups. In addition to demographic information such as age, gender, profession, and years of work in the SAEC, the questionnaire contained statements about extra adaptations and special support in the SAEC. Before the questionnaire was sent out, it was reviewed by 10 persons in different positions in the SAEC to validate the feasibility of the survey.

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics (version 27). Frequency analyses were conducted to describe the survey questions. Frequencies, means, and medians were used to analyze individual statements. The empirical data was analyzed with descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics presented an overall picture of the various claims on a group level. The Mann–Whitney test investigated the distinctions between professional categories for significance testing. It is a nonparametric test comparable to the parametric t-test and tests the null hypothesis when two samples are drawn from the same population. It determines whether the difference between the average ranking of the two groups is significant. By employing both descriptive and inferential statistics, the analysis benefits from a dual approach: descriptive statistics offer a broad view of the data, while the Mann–Whitney U-test provides a more detailed examination of specific differences between groups. This combination enhances the robustness of the findings and supports more nuanced interpretations of the results.

Like all similar studies, the results presented here should be seen as snapshots. Perceptions may change over time and depend on context and topics (Boström et al., 2024; Skolinspektionen, 2016). Repeated measurements and longitudinal studies are required to deepen knowledge of the problem. The study is limited to four occupational groups, and the results are only valid for those included. This was an adequate design choice for the study (cf. Hassmén and Koivula, 1996).

Participants in the study were recruited mainly through social media and specific groups aimed at staff working in SAECs. This type of sampling allowed us to obtain diversity in terms of, for example, geographical spread and level of education. However, the selection approach may have contributed to a preponderance of participants interested in educational issues as they were recruited in these types of groups.

A strength of the chosen statistical method is that extreme values cannot affect the test, which can occur in parametric tests. A weakness is that it requires more interpretation of the results (i.e., it is not as clear about conclusions of the material as parametric tests; Siegel and Castellan, 1988). The study could have been supplemented with qualitative data to explore nuanced perspectives. This was opted out due to the study design. Future research could incorporate mixed methods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of SAEC support structures. A follow-up study incorporating observational data would also strengthen the findings.

The following are the results of staff answers based on each research question. The first concerns how the staff perceives special support and how they describe it is handled. The results highlight that different professional groups experience the role of special education in SAEC differently. The results also show various conditions for working with extra adaptations and special support in SAEC.

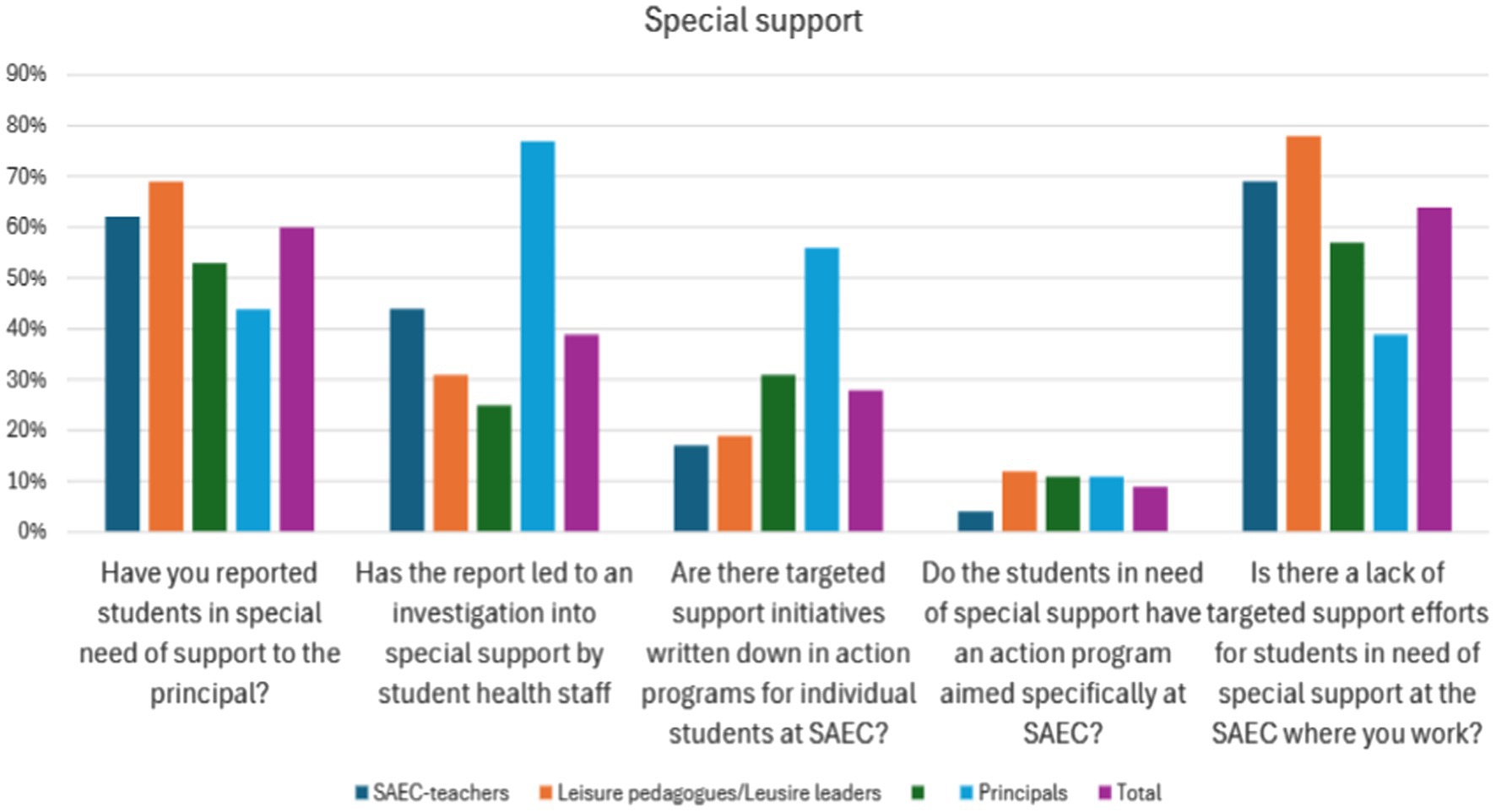

Related to extra adaptations and special support, the respondents took a stand on five statements, shown in Figure 1. When asked if the staff reported to the principal if students needed special support, 60% of the respondents answered Yes, and 40% answered No. The answers differed in a follow-up question on whether the notification of special support led to an investigation by student health staff. Most principals believed this was the case (80%), while the other staff estimates were about half as high (25–40%). These differences may be because the principals have an overall picture of the school, or they overestimate that the health staff has handled the notification.

Figure 1. SAEC staff perceptions of special support. SAEC staff perceptions of special support. The percentage indicates whether they agree with the statement (Yes).

When asked whether students needing special support have action programs explicitly aimed at SAEC, the answer was Yes (11% or below). This indicates that very few students in SAEC have action programs. When asked about whether there is a lack of targeted support efforts, the staff agreed with this statement to a great extent (65–78%), except for the principals (39%). In conclusion, approximately two-thirds of the respondents, excluding the principals, believe that support measures in the SAEC need to be improved. From the answers, we conclude that support efforts could be more robust in SAEC and that action programs aimed at SAEC and targeted efforts in the action programs are less common.

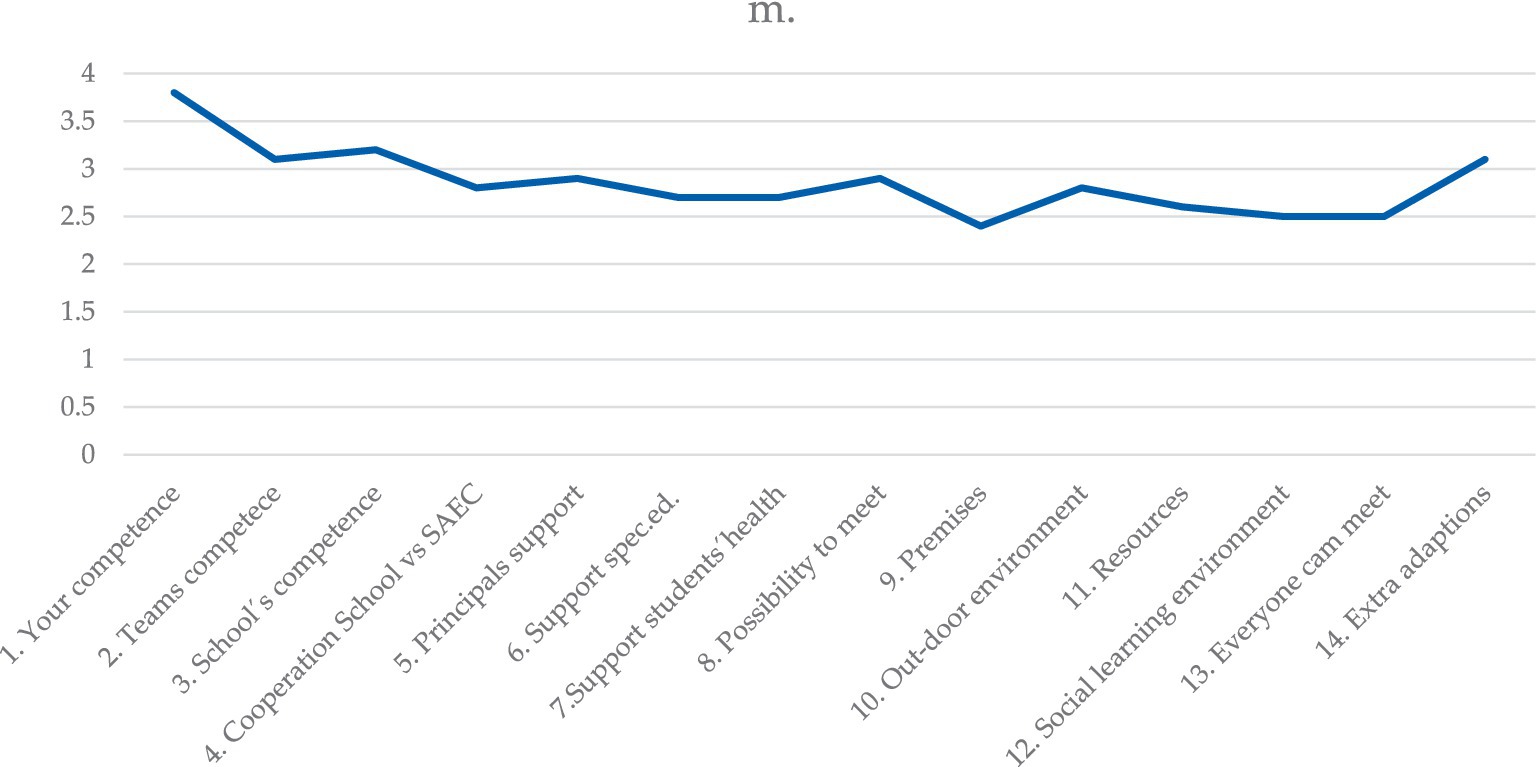

The second research question was about how staff values different aspects of support for students needing special support in SAEC. For example, they assess their team’s and school’s competence to meet students with special educational support needs and the possibilities of the premises and the outdoor environment. The respondents rated 14 statements on a Likert scale from 0 to 5. The results of the means are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. SAEC staff perceptions of the staff and the learning environment can meet students in need of special support.

The results show that staff values their competence higher (m = 3.8) than the teams’ (m = 3.1) and the schools’ competence (3.2). They also agree that extra adaptations are made in the learning environment at SAEC to meet the students individually (m = 3.1). All other statements are, on average, three or below. The estimate of the premises (no 9) has a low average value, which means that the staff believes the premises, to a low degree, meet students’ need for special support. The conclusion is that there is great potential for improvement.

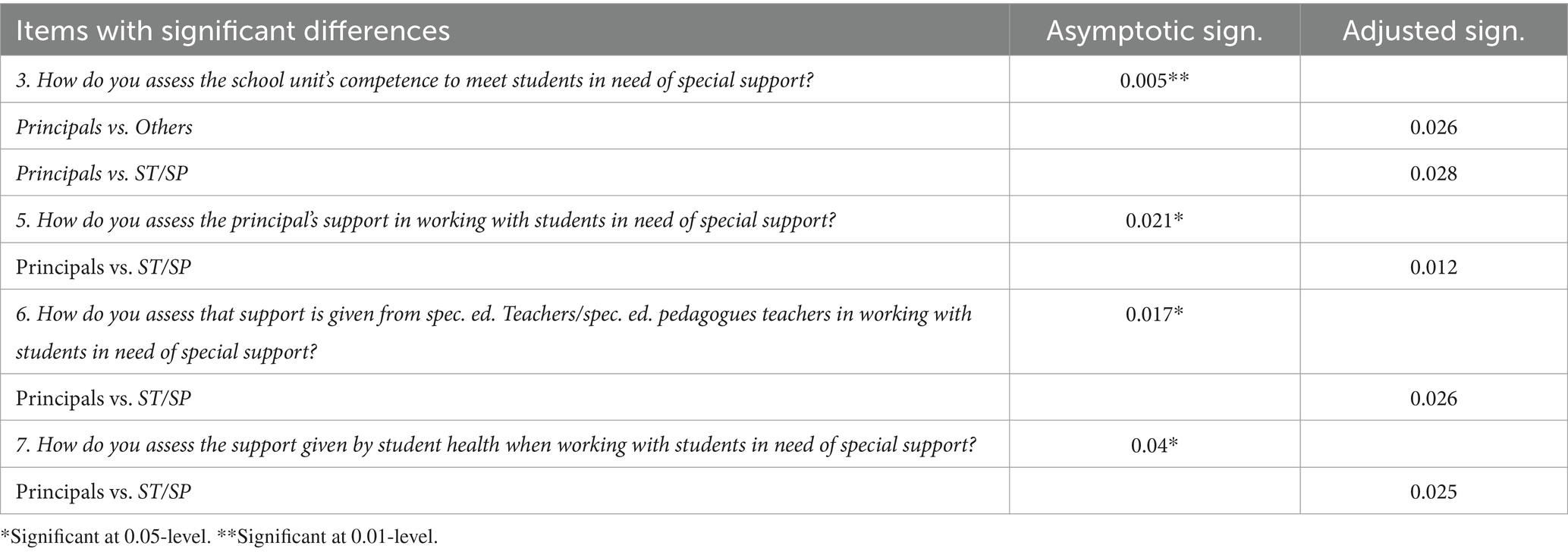

The third research question focused on differences within professional groups. Four of the 14 items concerning support to students needing special support show significant differences in responses between groups of respondents. A clear recurring pattern is that principals exhibit response patterns that deviate from those of other staff (assistants, SAEC teachers, and other staff); see Table 2.

Table 2. Significant differences between professional groups (ST = SAEC-teacher, SP = SAEC-pedagogues).

The statistical results show that principals assess the school unit’s competence to meet students in need of special support significantly higher than SAEC pedagogues/ leaders and others (assistants, childminders, etc.). Furthermore, it appears that principals assess their support in working with students in need of special support significantly higher than SAEC pedagogues/-leaders. Principals assess support from special ed. teachers/-pedagogues significantly higher than SAEC pedagogues/-leaders. Principals assess support from students´ health staff significantly higher than SAEC pedagogues/-leaders. Principals have distinctive perceptions of special support and extra adaptations compared to part-time pedagogues/leaders and other staff. They appreciate to a greater degree that students are offered special educational support in SAEC. No statistically distinct perceptions between principals and SAEC teachers appear.

This is a study which, in contrast to previous research, took as its starting point special functional variations (cf. Finnvold, 2018; Parish and Cloud, 2006) in SAEC-like environments but instead focused on special pedagogical concepts such as extra adaptation and special support in Swedish SAEC. Two previous studies (Karlsudd, 2020; Wernholm, 2023b) and an authority report (Skolinspektionen, 2024a; Skolinspektionen, 2024b) have clearly shown that many students in Swedish SAEC require special support but have yet to receive it. The need for extra support for school-age-students with disabilities is also emphasized in international research by, for example by Jinnah-Ghelani and Stoneman (2009). Concerning other countries, there is a lack of research in this area, but indications from other studies confirm similar situations (cf. Cirrin and Gillam, 2008; Haney, 2012; Martínez-Álvarez, 2017, 2019). Therefore, this study aimed to investigate to what extent different professional groups in SAEC perceive/describe how they support students needing special support.

The result shows that various professional groups have different and distinctive perceptions of students needing special support and extra adaptations in SAEC. In this context, it should also be remembered that the support given in different SAECs varies greatly between them (Sveriges Lärare, 2023). This can also be related to the fact that the conditions in SAEC differ a lot in connection to the staff’s educational level, planning time (Lager, 2015), and learning environment (Boström and Grewell, 2020).

The theoretical starting point of the study, the relational perspective (Ahlberg, 2009; Haug, 1998; Skrtic, 1995), emphasizes the importance of the environment, in this case, the SAEC, being adapted to the needs of different students. In cases where this happens in the Swedish SAEC, it is difficult to determine. If one looks at the low extent to which staff state that they make extra adjustments or that action plans are developed, there are concerns that students do not receive the support they are entitled to. The survey also shows that the resources are inadequate and insufficient, which has also appeared in previous studies.

Given that the results show different perceptions of how the special educational support is given, and in particular principals’ deviant perceptions, it seems to be a crucial task to get the entire staff, both in school and SAEC, in agreement in order to create a good learning environment for all students (cf. Ahlberg, 2009).

Above all, the principals’ perceptions differ from those of the other professional groups, even though The education act prescribes a clear and logical process regarding students in need of support (SFS 2010:800, n.d.). The question is whether the principals’ distinctive perceptions compared to professional groups with lower academic education are due to the principals having more insight into and knowledge of the area. Alternatively, if the principals overestimate the efforts, the staff closest to the students will have the best practical insight. Somewhat paradoxically, the SAEC-teachers do not differ with statistical significance from the principals. However, the result confirms that it prevails ambiguities in the type of support students are entitled to in SAEC (cf. Boström et al., 2024).

Another evident result of the study is that, regardless of the professional group’s opinion, very few students have action programs in SAEC. According to staff, less than 10% of students in SAEC have remedial programs. This can be compared to Sweden’s Teachers Union (Sveriges Lärare, 2023), which, in a survey, concluded that only 37% of the students deemed to need special support in SAEC receive it. However, according to the staff, reporting to the principal seems to have been quite extensive, but then the investigations and statements do not seem to occur on a proportionate scale. This can also be compared to Karlsudd (2020) and Wernholm (2023b) studies and the School Inspectorates report (2024), which stated that students in SAEC who need extra support but do not always get it are often unable to access it. It is time to take action following the Swedish education act. The question is, what is the lack of special support due to? Is special educational support not needed to the same extent in the SAEC as in school? Or, are the need of special support not just as important to address in the SAEC? Or are special educational interventions under-prioritized in the SAEC? Or is it that simple that special education in the SAEC has yet to develop and find its forms? The results suggest that the students do not receive the special educational support needed to attain sufficient development and learning in the SAEC, which does not meet the governing documents for the SAEC.

A third overall result of the study is that the staff sees great potential for improvement in the special educational support in SAEC, both in staff development and learning environments. But then the staff must also be given the conditions in terms of time and training (cf. Boström et al., 2024).

To bridge the gap in special support and extra adaptions in SAEC, extensive development work is needed both for policymakers and staff. First, resources need to be allocated to ensure adequate resources are allocated for special education. This includes additional staff with competence in special education, providing necessary materials, and creating conducive learning environments tailored to students in need of extra adaptions and special support. It is also important that the support measures developed are aligned with the SAEC’s teaching practices, which can ultimately help to create a holistic approach to students’ support needs (Skolinspektionen, 2024a; Skolinspektionen, 2024b).

This should be linked to regularly reviewing and updating policies related to special education support to ensure they are aligned with current research and best practices. Ensure these policies are effectively implemented across all SAECs.

Secondly, comprehensive training programs should be implemented for all staff members, including principals, teachers, and support staff, to ensure a consistent understanding of special educational needs and the importance of extra adaptations and special support. Foster a collaborative environment where all professional groups, regularly meet to discuss and plan the support needed for students. This can help align perceptions and strategies across different roles. This can lead to, for example, creating learning environments that are flexible and adaptable to the needs of all students. This includes physical spaces, teaching methods, and the use of technology to support learning.

The implications for the actors who govern SAEC are to take research and authority reports seriously and allocate resources so that students receive statutory support. Resources should be allocated not only to the activities but also to training staff. Without knowledge of special pedagogy, it is difficult to adapt to learning environments. Insight can also be found in research. In 2009, Jinnah-Ghelani and Stoneman highlighted important factors for implementing special education in the SAEC setting: adaptations in the learning environment, staff training, and conscious communication about the treatment of students in difficulties.

Another implication of this study is the importance of prioritizing research in special education in SAEC settings. This is required to understand and fulfill SAEC’s mission for approximately 500.000 students in Sweden. SAEC has both a complementary and compensatory mission in relation to the school. This will be difficult to fulfill if there are insufficient resources, competence, and research to drive development forward within SAEC. Since countries with similar extended education do not have curricula, international comparisons are difficult. However, some countries, for example, Australia, have, to some extent, governing documents, and Switzerland has none (Hurst et al., 2024), and this issue is discussed in our Nordic neighboring countries. Therefore, this study is important from an international perspective.

It also appears to be very important that staff working in SAEC gain more knowledge about how to support the different needs of students in this type of after-school care. It is also crucial that the support is provided in a way that is adapted to the specific mission of the SAEC, and thus, it may not always look the same for students in the SAEC as in school. Couture (1999) asked 25 years ago whether school-age care could meet the specific requirements students in need of support can have. Our answer is yes, but the framework factors should be implemented to give the school-age-care an honest opportunity to do so. However, international research in similar settings (extended education) in other countries is needed to gain a broad and comprehensive understanding, so students in need of special support will receive special pedagogical support even outside the context of the school.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HE: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

After-school Alliance (2014). After-school supporting students with disabilities and other special needs, MetLife Foundation. ED546847.

Ahlberg, A. (2009). “Kunskapsbildning i specialpedagogik [Knowledge formation in special education]” in Specialpedagogisk forskning. En mångfacetterad utmaning. ed. A. Ahlberg (Lund: Studentlitteratur), 9–28.

Ahrbeck, B., Felder, M., and Schneiders, K. (2018). Lessons from educational reform in Germany: one school may not fit all. J. Int. Spec. Needs Educ. 21, 23–33. doi: 10.9782/17-00036

Andishmand, C. (2017). Fritidshem eller servicehem. En etnografisk studie av fritidshem i tre socioekonomiskt skilda områden. [An ethnographic study of after-school centers in three socioeconomically diverse areas.] (Diss). Göteborg: Göteborgs Universitet, 403.

Boström, L., and Augustsson, G. (2016). Learning environments in Swedish leisure-time centres: (in)equality, “schooling”, and lack of Independence. Int. J. Res. Extend. Educ. 4, 125–145. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v4i1.24779

Boström, L., Elvstrand, H., and Lundbäck, B. (2024). Om extra anpassningar och särskilt stöd i fritidshemmet. Hur tänkte policyaktörerna egentligen? [About extra adaptations and special support in the leisure center. What did the policy actors really think? Specialpedagogiska rapporter och notiser], Kristianstad: Högskolan Kristianstad. 22.

Boström, L., and Grewell, C. (2020). “Fritidshemmet lokaler och materiella resurser i relation till verksamhetens kvalitet. [The SAEC's premises and material resources in relation to the quality of the activities]” in Betänkande av Utredningen om fritidshem och pedagogisk omsorg: Stärkt kvalitet och likvärdighet i fritidshem och pedagogisk omsorg, SOU 2020, vol. 34 (Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik AB), 493–516.

Cirrin, F. M., and Gillam, R. B. (2008). Language intervention practices for school-age children with spoken language disorders: a systematic review. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 39, 110–137. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/012)

Couture, M. (1999). Can school-age care meet the specific needs of special needs children? Can. J. Res. Early Childhood Educ. 8, 65–69.

Elvstrand, H., Lago, L., and Lundbäck, J. (2022). Fritidshemslärares arbete, trivsel och inkluderande arbetssätt och samverkan: en enkätstudie i en svensk fritidshemskontext. [SAEC-teachers work, well-being and inclusive working methods and collaboration: a survey study in a Swedish SAEC context]. FPPU Forskning i Pædagogers Profession og Uddannelse 6, 107–121. doi: 10.7146/fppu.v6i2.134278

Engel-Yeger, B., and Hamed-Daher, S. (2013). Comparing participation in out of school activities between children with visual impairments, children with hearing impairments and typical peers. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34, 3124–3132. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.05.049

Finnvold, J. E. (2018). School segregation and social participation: the case of Norwegian children with physical disabilities. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 33, 187–204. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1424781

Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., Klang, N., Magnusson, G., and Nilholm, C. (2015). Speciella yrken? Specialpedagogers och speciallärares arbete och utbildning. En enkätstudie. [Special professions? The work and education of special pedagogues and special teachers. A survey study], Karlstad: Karlstad University Studies. 2015. 13.

Haglund, B., and Peterson, L. (2017). Why use board games in leisure-time centres? Prominent staff discourses and described subject positions when playing with children. IJREE 5, 188–206. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v5i2.06

Haney, M. (2012). After school care for children on the autism spectrum. Child Fam. Stud. 21, 466–473. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9500-1

Hassmén, P., and Koivula, N. (1996). Variansanalys. [Analysis of variance]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Haug, P. (1998). Pedagogiskt dilemma: Specialundervisning. [Pedagogical dilemma: Special education]. Liber: Göteborg.

Hurst, B. (2019). Play and leisure in Australian school age care: reconceptualizing children’s waiting as a site of play and labour. Childhood 26, 462–475. doi: 10.1177/0907568219868521

Hurst, B., Schuler, P., Elvstrand, H., Cartmel, J., Boström, L., and Orwehag, M. (2024). Extended education in Switzerland, Sweden and Australia – In search of didactical commonalities and connections : ZfE Edition (in press).

Jinnah-Ghelani, H., and Stoneman, Z. (2009). Elements of successful inclusion for school-age children with disabilities in childcare settings. Child Care Pract. 15, 175–191. doi: 10.1080/13575270902891024

Karlsudd, P. (2020). Looking for special education in the Swedish after-school leisure program construction and testing of an analysis model. Educ. Sci. 10:359. doi: 10.3390/educsci10120359

Kirkpatrick, B. A., Wright, S., and Daniels, S. (2019). Tootling in an after-school setting: decreasing antisocial interactions in at-risk students. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 21, 228–237. doi: 10.1177/1098300719851226

Lager, K. (2015). I spänningsfältet mellan kontroll och utveckling. En policystu-die av systematiskt kvalitetsarbete i kommunen, förskolan och fritidshemmet. In the field of tension between control and development. A policy study of system-atic quality work in the municipality, preschool and after-school centres. Göte-borgs Universitet (Diss).

Lundbäck, B. (2022). Specialpedagogik i fritidshemmet. Från samlat forskningsläge till pedagogisk praktik. [Special education in SAEC. From a comprehensive research situation to pedagogical practice]. (Diss.) Växjö: Linnéuniversitetet.

Lundbäck, B., and Fälth, L. (2019). Leisure-time activities including children with special needs: a research overview. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 7, 20–35.

Martínez-Álvarez, P. (2017). Multigenerational learning for expanding the educational involvement of bilinguals experiencing academic difficulties. Curric. Inq. 47, 263–289. doi: 10.1080/03626784.2017.1324734

Martínez-Álvarez, P. (2019). What counts as science? Expansive learning for teaching and learning science with bilingual children. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 14, 799–837. doi: 10.1007/s11422-019-09909-y

Parish, S. L., and Cloud, J. M. (2006). Child care for low-income school-age children: disability and family structure effects in a national sample. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 28, 927–940. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.10.001

Plantenga, J., and Remery, C. (2017). Out-of-school childcare: exploring availability and quality in EU member states. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 27, 25–39. doi: 10.1177/0958928716672174

Rapp, A. C., and Corral-Granados, A. (2024). Understanding inclusive education – a theoretical contribution from system theory and the constructionist perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 28, 423–439. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1946725

Siegel, S., and Castellan, N. J. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioralsciences. New York, London: McGraw-Hill.

Skolforskningsinstitutet (2021). Meningsfull fritid, utveckling och lärande i fritidshem. [meaningful leisure, development and learning in after-school centers]. Stockholm: Systematisk litteraturöversikt. 3.

Skolinspektionen (2016). Skolans arbete med extra anpassningar- kvalitetsgranskningsrapport. [The school's work with extra adaptations - quality review report]. Skolinspektionen. Dnr 2015:2217.

Skolinspektionen (2024a). Elevens hela dag som utgångspunkt för stöd. Arbetet med extra anpassningar och särskilt stöd i skola och fritidshem. [The student's entire day as a starting point for support. Work with extra adaptations and special support in school and SAEC]. Rapport 2024, 7.

Skolinspektionen (2024b). En granskning av skolornas arbete med extra anpassningar och särskilt stöd i de obligatoriska skolformerna och i fritidshemmet. [a review of schools' work with extra adaptations and special support in compulsory school forms and in SAEC]. Rapport 2024, 8.

Skolverket (2014). (rev. 2017). Allmänna råd för arbete med extra anpassningar, särskilt stöd och åtgärdsprogram. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Skolverket (2023). Styrning och ledning av fritidshemmet. Kommentarer till Skolverkets allmänna råd om styrning och ledning av fritidshemmet. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Skolverket. (2024a). Särskilt stöd i grundskolan. Läsåret 2023/24. Available online at: https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=12766 (Accessed July 1, 2024).

Skolverket. (2024b). Extra anpassningar, särskilt stöd och åtgärdsprogram. Extra anpassningar, särskilt stöd och åtgärdsprogram - Skolverket. 240705.

Skrtic, T. (1995). Disability and democracy: reconstruction (special) education : Teacher College Press.

SOU 2020:34. Stärkt kvalitet och likvärdighet i fritidshem och pedagogisk omsorg – Betänkande från Utredningen om fritidshem och pedagogisk omsorg (U 2918:08). Available online at: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2020/06/sou-202034 (Accessed April 1, 2024).

SOU 2022:61. Allmänt fritidshem och fler elevers tillgång till utveckling, lärande och en meningsfull fritid. Available online at: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2022/11/sou-202261/ (Accessed April 30, 2024).

Sveriges Lärare (2023). Gruppstorlekar, extra anpassningar och särskilt stöd i fritidshem. Statistiskt faktablad 2023:1. Available online at: https://www.sverigeslarare.se/contentassets/fad73fa042f84039b8d848106d1fcd91/2023-1-gruppstorlekar-extra-anpassaningar-och-sarskilt-stod-i-fritidshem.pdf (Accessed April 30, 2024).

Wernholm, M. (2023a). Fritidshemslärares erfarenheter av extra anpassningar och särskilt stöd i fritidshemmet. SPSM. FoU skriftserie 15:2022.

Wernholm, M. (2023b). Undervisning i ett fritidshem för alla? Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 28, 64–88. doi: 10.15626/pfs28.04.03

Yamashiro, N. (2021). How well are afterschool programs serving children with special needs or disabilities? After school snack. Available online at: https://afterschoolalliance.org/afterschoolSnack/How-well-are-afterschool-programs-serving-children-with-special_10-11-2021.cfm (Accessed April 30, 2024).

Keywords: extra adaptations, professional groups, School-Age Educare Centers, significant differences, special educational support

Citation: Boström L and Elvstrand H (2025) What about extra adaptions and special support in Swedish School Age Educare Centers? Front. Educ. 10:1496609. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1496609

Received: 14 September 2024; Accepted: 04 March 2025;

Published: 25 March 2025.

Edited by:

Dianne Chambers, Hiroshima University, JapanReviewed by:

Kayi Ntinda, University of Eswatini, EswatiniCopyright © 2025 Boström and Elvstrand. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lena Boström, bGVuYS5ib3N0cm9tQG1pdW4uc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.