- Department of Educational Science, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

Teachers have experienced online teaching anxiety since the pandemic, and as education continues with digitization, the emotional experiences should be addressed. By focusing on the emotions experienced by schoolteachers in online teaching, this research investigates how intense feelings, and strong emotions can be transformed into critical self-reflection and ultimately achieve transformation based on the transformative learning model. As teachers across jurisdictions reportedly experienced burnout, this research discovers that transformative learning is the gateway and a path that allows teachers' passion to be reignited. To cope with the changes and challenges brought by the use of AI and the vastness of online information, it is essential for teachers to re-examine and identify their roles in the classroom and to consolidate their valuable contributions and irreplaceable role in an effective learning environment. Through case studies that cover the life stories of five teachers in Hong Kong, Canada and Taiwan, this research discusses how the emotionality of teachers plays a key role in transformative learning and examines the process in which anxieties transcend into passion.

1 Introduction

The study of emotions has continued to intrigue scholars in various disciplines; in education, teachers' emotions used to be overshadowed by “wellbeing” (Chen, 2020). Although “emotions” does not have a consent definition in academia now, it does not and should not mean that the study of emotions should be less critical. This research aims not to define emotions but to investigate the correlation between emotions and transformative learning. There are many interpretations of the word “emotions”; this research takes the phenomenology and hermeneutics approach, which postulates emotions as an interior emotional space that helps individuals make sense of the world (Beatty, 2019). A narrative approach highlights the unique aspects and the temporal progression of emotions (Beatty, 2019). While the long-term effects of emergency remote teaching (ERT) are still unfolding, education contexts have further pursued digitization (Salama and Hinton, 2023). The transition from in-person classrooms to virtual settings represents a significant transformation in the teaching and learning environment. Most importantly, the nature of teacher-student relationships has altered, as traditional interaction dynamics and established social norms have been disrupted. The digitized interaction is evident in the use of digital means and Internet language (Lee et al., 2024), how it translates to and from different emotions in the classroom must be delineated.

When teachers encounter these unfamiliar scenarios and simultaneous changes, the familiar teaching environment they rely on becomes unsettled, and the critical disjuncture identified here marks the beginning of transformative learning (Taylor, 2000; Kitchenham, 2008). Transformative learning, coined by Mezirow (1989), consists of two key aspects: habits of mind and points of view. When a person experiences a disorienting dilemma in life, which is an event that disrupts the person's familiar social reality, reflection and critical reflection might take place, preparing the individual to acquire further knowledge about the disrupting events, then reintegrating the reflections and ideas into life. However, the model does not address the fundamental connection between emotions and perception, which a vast body of research has discussed the interplaying role of an individual's value judgement, learning and emotions (Pressley, 2021a; Wulf, 2022). This study explores the intricate connection between emotions and learning among teachers, framing the pandemic as a disorienting dilemma, it conceptualizes emotions using the theoretical lens provided by Pekrun (2024)'s and Schutz and Pekrun (2007)'s theory on academic emotions and classroom emotions based on control-value theory.

When emergency remote teaching was first implemented, many teachers experienced online teaching anxiety and lack of emotional support; those emotions, however, are expected to be dealt with by themselves, as a result, many of which remained unresolved. The correlation between professionalism and its unacceptable coexistence with emotions has continuously exploited teachers' capacity for emotional provision and excessive emotional labor (Tsang and Wu, 2022; Wulf, 2023). This research examines the life stories of teachers in three different countries, through individual in-depth interviews, narrative and thematic analysis are applied to inquire into the emotional experiences during the pandemic and in post-pandemic times. In particular, the connection between emotions in the classroom and how those emotional experiences contribute to transformative learning are explored and discussed.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Emotions in traditional and digital classrooms

Online teaching pedagogy is very different from an in-person classroom. Instant exchange of body language, such as eye contact and nodding, etc. are limited by the camera in an online setting, teachers are burdened with identifying and dismissing boredom using a wide array of classroom interactions and activities (Naylor and Nyanjom, 2021; Taguchi, 2020). A virtual teaching space requires teachers to have high digital literacy and be familiar with the functions of the applications such as breakout rooms (Pangrazio et al., 2020), muting functions, etc. Teachers have become the central reason for the flow of emotions, apart from undertaking self-blame and self-doubt, they have to be extra observant, react swiftly to dismiss students' boredom and be pleasant enough to sustain concentration and attention from students.

The emotional transaction occurs during classroom events, in other words, the classroom itself is an emotional place (Schutz and Pekrun, 2007); the transactions depend highly on the individuality of teachers and students. In both online and in-person classrooms, an emotional transaction takes place, as it depends highly on teachers' perspectives, self-perceived identities and beliefs; the emotional flow in an online classroom is positively correlated to the teacher's beliefs in online teaching. Emotional dissonance occurs when teachers experience conflict between their feelings and the perceived display rules they are expected to follow (Morris and Feldman, 1996; Schutz and Pekrun, 2007). When such emotional baggage is not resolved, disequilibrium occurs, often resulting in emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, as emotions are constantly transacted between teachers and students, the feelings of teachers directly impact students' learning (Pekrun, 2022, 2024). Teachers' enjoyment and enthusiasm have been proven to induce enjoyment of classroom activities and instruction in students; this also relates to the contagious nature of emotions known as reciprocal causation in the dynamical systems theory (Pekrun, 2022, 2024). To regulate achievement emotions in the classroom, four aspects have been discussed: first, to target the emotion per se using relaxation techniques such as breathing methods; second, to address the value underlying emotions through cognitive restructuring and therapy sessions; third, to increase one's academic competences, such as training of learning skills; and lastly, to adjust the academic environments through classroom instructions and activities (Pekrun, 2022). Achievement emotions are centered on students, yet this article explores the possibility of expanding them to teachers, as teachers are also learners in the classroom, especially in an unfamiliar teaching setting. Recognizing the need to regulate and manage achievement emotions for teachers, implies that teachers should also reflect on their current values to tackle the underlying emotions, upgrade their skills such as online teaching tools and techniques, and design classroom instructions and learning environments that are mutually enjoyable for themselves and their students.

2.2 Regulation of achievement emotions and transformative learning

Transformative learning is an adult learning theory created by Mezirow (1991). The theory has three essential elements: individual experience, critical reflection, and dialogue (Mezirow, 2000a, 2012; Taylor and Cranton, 2012). As the theory develops, more core elements have been identified: a holistic orientation, an awareness of context and an authentic practice. Reflection is prioritized as it shapes how an individual makes sense of an experience or an event. The critical disjuncture marks the beginning of any possible transformation later, Taylor (2017) added that one's life experience is indeed a determinant factor of how individuals engage in dialogue and reflection; the critical disjuncture or disillusionment experienced by an individual opens a pedagogical entry point (Taylor, 2017). Upon reflection, individuals re-examine their personal and professional values; as the process takes place, Jarvis (2012) pointed out that a narrative point of view usually leads to identifying characteristics, values and actions that are opposite to one's own. It is precisely these contrasting values that provoke meaning-making and re-making and trigger critical reflection, which facilitates transformative learning, thereby enabling a more direct and holistic point of view in individuals. An inseparable relationship exists between transformative learning and an individual's emotions and feelings. Mezirow (2000b) identifies three types of meaning perspective transformations: content, process, and premise. Perspective transformation arises from an individual's recognition of conflicting emotions, thoughts, and actions. Content transformation focuses on reflecting on how one perceives, thinks, feels, and does; process transformation examines how one carries out the act of perceiving; and premise transformation involves understanding why one perceives as they do, that is, identifying the underlying structures that developed the individual's current values (Mezirow, 2000a). Together, these elements underpin critical reflection. Gaining full awareness of one's emotions and feelings is crucial in achieving transformation in content—a connection between perception and emotions substantiated by numerous scholars (Chen, 2020; Brosch, 2021; Wulf, 2023; Moore and Hodges, 2023).

The contagious nature of emotions must not be neglected; as emotions flow in the classroom, emotions experienced by teachers reflect their self-perceived identities (Zembylas, 2003) as emotional transaction occurs, beliefs, goals and standards are also transacted at a social-historical-contextual level (Schutz and Pekrun, 2007). The phases in transformative learning could be applied to regulate such transactions. To better illustrate, Figure 1 has been created.

Figure 1. Managing achievement emotions through a transformative learning framework, incorporating ideas from Mezirow (2000a)'s management of achievement emotions and Mezirow (2000b)'s transformative learning framework.

Pekrun has postulated 4 ways to regulate achievement emotions building on the control-value theory: emotion-oriented regulation and treatment, appraisal-oriented regulation and treatment, competence-oriented regulation and treatment, and design of academic environments (Pekrun, 2006). Emotion-oriented regulation targets emotions directly through relaxing techniques such as breathing; appraisal-oriented regulation is cognitive restructuring, which involves self-examining the underlying emotions; competence-oriented regulation reflects current skills and recognizes the need to improve; design of academic environments is about classroom instruction. Figure 1 postulates that the ways are directional, each regulation requires more in-depth reflection than the last. This overlaps with Mezirow (1991)'s transformative learning theory and describes the steps in the TL framework: self-examination of feelings, critical assessment of assumptions, and search for new roles and reintegrating them into life, which is rephrased as “enacting transformation in life” in Figure 1. According to the transformative learning framework, when an individual reflects on one's perception and becomes aware of one's feelings and thoughts that contrast each other, one examines the frame of reference. Frame of reference categorizes experiences, beliefs, people, events, and the self (Mezirow, 2000b, p. 22). Habits of mind, however, are concerned with how an individual thinks and feels on a much more individualized level as they center on one's habits of thought process. By incorporating Pekrun's four steps in regulating achievement emotions into the transformative learning framework, the key step is critical self-reflection and reintegration into life, which can be broken down into several parts: (i), teachers need to examine existent values and identify the current frames of reference; (ii) by exploring one's course of action, new knowledge must be acquired to adjust the current frames; and (iii) to build confidence and skills in assisting individuals to channel meaningful reflections into reintegration in life.

3 Method

3.1 Participants

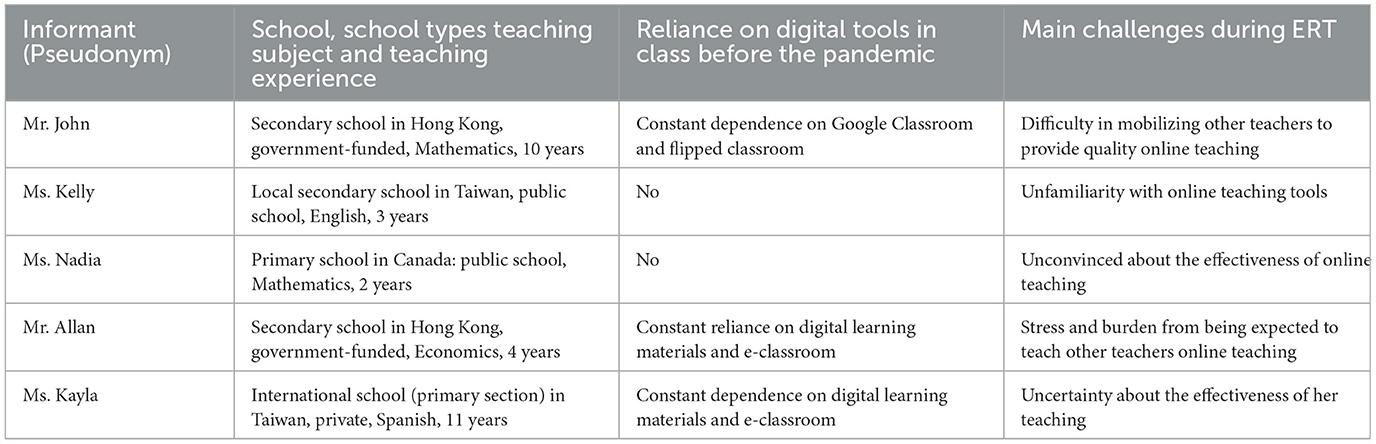

Five schoolteachers teaching in Hong Kong, Canada and Taiwan were interviewed. These informants were approached by snowball sampling. The first two informants were teachers I know who were teaching at two different school types; each was asked to invite one other informant working in another school, and the fourth informant also invited another teacher from a different school to the research. This reduces sample biases and introduces diversity within the sample. Semi-structured interviews and open-ended questions were used so that informants could describe their stories and experiences in detail (Creswell, 1998; Mezirow and Taylor, 2009). This research examines how schoolteachers interpret the shifts in education brought about by the pandemic and how they perceive their professional identity in the context of the digital age.

These schoolteachers work in five different secondary schools in Hong Kong, Canada, and Taiwan. These three regions are selected because continuous professional development is prioritized in them; moreover, as each region has diverse classrooms, teachers' experiences might be moderate due to cultural inclusivity. Technology integration into education has also become increasingly important in these regions at a similar development speed. Owing to this, it is believed that the cross-cultural case studies in this research would bring meaningful insights regarding teachers' experiences during the pandemic. Table 1 has been created to describe their demographic background.

3.2 Instruments

This interdisciplinary qualitative research incorporates digital fieldwork, including online interviews with informants and virtual classroom observations, where I participated as a guest in one of my informants' online classes. Memo writing and field notes were compiled during each semi-structured interview. Keywords, key phrases and significant emotions were jotted down in the fieldnotes to enable smoother analysis later. Due to varying consent, only two interviews were audio-recorded; the recorded interviews were conducted in English or translated into English. To increase validity, memo writing and field notes were jotted during the interviews, and a preliminary analysis of keywords was conducted immediately after the interviews based on the memo and field notes. Moreover, informants were asked to review the quotes used in the research results to verify the accuracy and completeness of the data. I have also sent a copy of the research article to them to see if the quotes and discussion reflected their thoughts and feelings accurately. All of them replied, and the feedback was positive so far.

Digital participant observation was also conducted in the study, digital ethnography was applied through online interviews and virtual participant observation. An online classroom observation session was arranged via MicrosoftTeams. To minimize the effects on Mr John's students, they were not told that I was there as a researcher, but that I was there as an observer to John's teaching. As the lesson shows the faces of students, video recording As was not conducted at all to protect the students. To increase validity, field notes were written and I also stayed behind for about 30 min to double check a few details with Mr John when the lesson was over. Digital ethnography is a new research method; though a relatively new and unconventional research method, it is a valid and valuable tool for understanding contemporary fields, particularly in studies focused on digital learning. This research is instrumental as it focuses on digital learning. Digital ethnography emerged in the 2000s, particularly regarding how ethnography could be moved to the digital world and how ethnography can help anthropologists understand the digital world (Pink et al., 2015). It is an approach that invites researchers to consider the effects of digital media in shaping ethnography; this research employs digital ethnography by conducting interviews and participant observation online.

The interview asked the following questions:

Q1. Please describe your experience of ERT during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Q1.1 What were the strongest emotions you felt during that time?

Q1.2 How did you manage those emotions?

Q2. What was the most significant challenge, and how did you overcome it?

Q2.1 How did you feel when you were facing that challenge?

Q2.2 How did you feel when the challenge was over?

Q3. Have you noticed any differences in your students when physical school resumed?

Q3.1 Are these changes observed in particular groups of students or students in general?

Q3.2 Were those differences only observed by you, or did any of your colleagues also share similar insights?

Q4. Now that the pandemic has passed, do you still rely on digital tools such as Kahoot or AI in class? Why or why not?

Q4.1 What is your take on digital tools? Are they beneficial to students?

Q4.2 Do you think your students learn better or perform worse when you teach with digital tools?

Q5. Do you think teachers will become obsolete in the coming era?

Q5.1 In your opinion, what can teachers do to avoid being replaced by artificial intelligence?

Q5.2 What kind of qualities should teachers have that are also irreplaceable by machines?

3.3 Procedure

Narrative analysis was used in the data analysis, as it allows a more complete interpretation of informants' emotional experiences, which is the focus of this research. The theoretical basis of narrative analysis stems from Gadamer (2003)'s Bildung, which loosely translates as the image of humans. In-depth interviews provide the space for informants to speak about their experiences, and from the narratives they have chosen, the underlying values that protrude in the conversation allow room for researchers to grasp the perspectives to capture the image that the individual has regarding the research subject at hand. Thick description is incorporated in the data analysis and discussion to include the informants' narration and viewpoint in as much depth as possible.

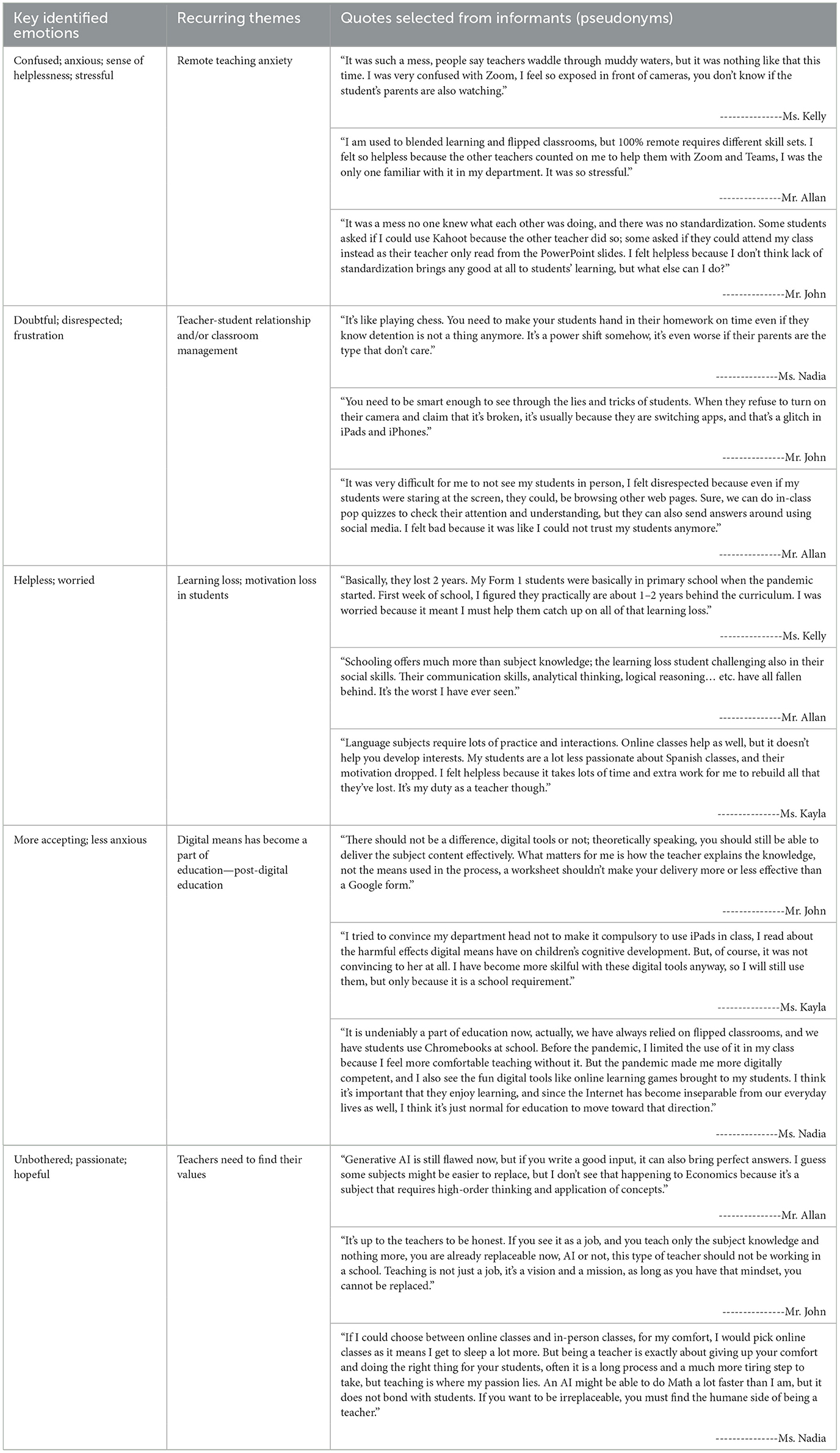

Thematic analysis was employed in the data analysis process to identify and interpret repeated keywords and similar patterns within the data as reflected in Table 2. This method provides flexibility to delve beyond surface-level content, exploring underlying meanings and implicit and explicit ideas held by the informants. The recurring themes were finalized based on the recurring and strong emotions shown in my informants' story narration, the content and experiences they were describing were compared, and the commonality between them was identified as the themes.

Narrative analysis provides a clear narration from the informants regarding how they understand the experiences, how they structure the story, how it was told, and the events that they highlighted and showed specifically strong emotions reflect their personal identity, value and what the experiences mean to them. Thematic analysis provides the possibility to analyze and categorize the emerging themes and patterns across data sets. Recurring ideas are discussed and summarized, which is crucial to understanding the commonality in the informants' experiences.

While the informants come from diverse cultural backgrounds, cultural differences primarily influence their emotional expressions, reflecting the behavioral dimension of emotions. However, this paper focuses on the emotions experienced by the informants, adopting a hermeneutic perspective that posits individuals from different cultures can share similar emotional experiences (Beatty, 2019). Five key themes emerged in this research, they were identified by strong emotions repeatedly mentioned by these informants, and by linking the emotions back to the incident that they were describing, the issues were identified as the themes that protrude. These recurring themes consistently in the informants' narratives about their experiences.

4 Results

The transcripts and memos are analyzed using narrative and thematic analysis, as the research centers on emotions. Each informant's narrative, along with the common themes that emerge as patterns in their responses, is particularly important. Frequently mentioned emotions and associated themes are identified as informants recounting their experiences and sharing their opinions in response to each question. The relevant quotes and identified themes are presented in the following table.

In each research question, one big theme was identified; although other subthemes also appeared, the selected ones are the ones that protrude. My informants have different starting points regarding their views and experiences in online education. The pandemic's beginning has been a critical disjuncture for all the informants, who have all experienced reflection throughout the period. The pandemic marks a chaotic beginning of massive online education. Still, the end of the pandemic and the emergence of AI have signified an official start of a digital era.

4.1 Remote teaching anxieties

When asked to describe their experiences during emergency remote teaching, most informants agreed it was chaotic, and they all reported a lack of structure from the school and other teachers teaching the same subject, and a lack of technical support (such as tutorials on which software to use and how to utilize all functions in it) from the education bureau and the school. When ERT was implemented, only two of my informants (Ms Nadia and Mr John) had previously been trained to conduct lessons online. Still, they also shared similar emotional experiences with the others: a sense of helplessness, confusion and anxiety. Pressley (2021b)'s study on how the pandemic impacted teachers' self-efficacy revealed that teachers had the lowest instructional efficacy when teaching virtually as compared to hybrid and in-person, which also echoes to the anxiety that is reported by informants in this study. Remote teaching anxiety denotes teachers' anxiety precisely when the teaching is conducted online (Ma et al., 2022). As reflected in these informants, one key reason was their unpreparedness for suspending in-person schooling and the shift to virtual mode < 2 months after “COVID-19” was first detected. These informants have not received sufficient training on online teaching; they felt incompetent and lacked self-confidence during ERT. Full-scale remote teaching has altered my informants' familiar social realities, bringing disorientation.

Another source is the feeling of being monitored by students' parents. In a physical classroom, such possibilities could never happen without formal and former school invitations, e.g., lesson observations are quite common in schools. However, in a virtual environment, teachers will not know if students' parents are also sitting in class. At the start of ERT, this caused lots of anxiety in my informants, thereby stirring up negative emotions when they were teaching, and negatively affecting the online classrooms as these emotions are transacted to their students (Pekrun and Marsh, 2022).

A third source of anxiety comes from how other teachers in school counted heavily on his knowledge and experiences of online teaching. Mr. Allan was promoted during the pandemic to be in charge of teacher training in using digital tools. Allan did not see himself as an expert in online teaching, but he was the only one who had ever conducted blended learning before. As he pointed out, other teachers in his department have been teaching for two decades without digital tools, so they were reluctant. This is also consistent with the research findings from previous scholars, Remmi and Hashim (2021) found that veteran teachers prefer traditional methods over online tools because they are more familiar with them, making them feel more secure and comfortable.

A fourth source of anxiety is students' feedback from cross-classroom comparisons. Standardization in digital teaching and how it should be used after school was not present, teachers rely on one's judgement and rubrics. As Mr John described, “The lack of standardization caused students to compare the lesson structure and formats with one another, resulting in extra stress for teachers.” Some teachers might be more familiar with digital tools, while it is still new for others; students' cross-classroom comparison put teachers in a position to “compete with each other.” John mentioned “a sense of defeat” when he was given suggestions to use Kahoot “just like the other class.”

“Some students asked if I could use Kahoot because the other teacher did so; I was kind of humiliated but then first things first, so I upgraded my knowledge and started to make things even more interesting. One day a student from another class asked if she could attend my class as their teacher was only reading from the PowerPoint slides. I felt quite helpless. If some teachers decide to slouch, there's not much I can do about it.” ---------------Mr John

As reflected in John's narrative above, the frustration lies in how some teachers are not making enough effort to deliver quality online classes to students. He is also anxious because students could give constructive feedback about the delivery of the classes, which could also appear to be directive and commanding, a power dynamic that teachers are usually not used to. He also expressed concerns regarding the fact that not every student dares to voice out their needs, nor directly to the involved teachers. In the case when another student asked to join his class, it was difficult to handle as the other teacher involved was the department head. For Mr. John, mainly working in Hong Kong, a city embedded with the cultural values of respecting one's superior, it was particularly difficult and socially inappropriate in the situation.

4.2 Teacher-student relationships & classroom management

It has been established in numerous research that quality teacher-student relationships are critical to students' academic achievements; the development of rapport with students is especially important because it allows teachers to understand students better as a person, and to identify and possibly solve problems that students face in life. It has also been expected that teachers take up the role and be able to identify students with family issues and/or school bullying, etc., (Kaufmann and Vallade, 2020). Students spend the most time at school with their teachers, while the most with their parents or guardians, teacher-student relationships are therefore very important (Lave and Wenger, 1991).

In online classrooms, teachers find it challenging to feel respected from their students, as the lack of physical presence and body language make it almost impossible to ensure students are giving their full attention. The shift to a virtual classroom has made it difficult for Mr. Allan to trust his students, the power dynamic was very different, and he felt powerless and insecure as students could switch off their cameras anytime they wished. Hermino and Arifin (2020)'s research discussed the restriction of electronic devices in schools; whereas in a virtual classroom, not only is the restriction impossible, but students also face little to no consequence even when caught being on their phones. Ms. Nadia described it as “a game of chess,” teachers have to find a strategic way to discipline their students as erring them too much might also cause disinterest or disengagement in online classes.

Proper and appropriate class dynamics rely on teachers' goal setting and rules writing with their class at the beginning of the semester (Sprick et al., 2021). In offline classes, rules usually focus on students' behaviors, such as not chatting amongst themselves during lessons, not talking back to their teachers, etc. Although these rules might seem trivial, they formulate the base of how a good student is expected to behave. In a virtual classroom, extra time is placed on administrative measures just to ensure students are present on Zoom. Some teachers place pop quizzes at random times to make sure students are still sitting in front of the computer and not wandering around or daydreaming. The effectiveness of these adjustments is often correlated to the variation of adjustments, but the variations depend highly on the digital literacy of teachers. For those who have relatively lower digital literacy, they might simply require students to keep their cameras on. However, it is not practical, first, there is the issue of privacy; second, students can still come up with excuses. In Mr. John's experience, his students lied to him about the malfunctions of their cameras. He then gave them a deadline to get their devices fixed. Mr. John has an Instagram account that he uses to post video clips that explain Mathematics concepts to his students. He realized the students lied to him about the cameras because of a post they did, feeling disappointed, he then spoke with each of the students privately, and they promised it would not happen again. Although it worked out all right in the end, the process required lots of extra time, effort, and mental strategies.

4.3 Learning losses of students

The most significant difference in students reported was the issue of learning losses. Teachers find it worrying as the curriculum did not make any adjustments because of the pandemic, it implies that teachers are responsible for 3 years of subject knowledge in one academic year to help students catch up. As described by Ms. Kelly, students have lost 2 years. She noted that learning loss was related to students' lack of concentration in online settings, the lack of self-discipline and self-efficacy are the direct cause, although she also noted that students with lower SES might face more difficulties than others. Access to resources such as a desk, an electronic device with a camera and microphone, a stable network, etc., is not the same for every student. The correlation between resources and students' achievements has been discussed for years (Singh, 2016; Hubalovsky et al., 2019; Kuhfeld et al., 2023); yet in online learning, these inequalities are amplified; the burden and the consequences of widened learning gap have been shifted to teachers.

Another observable learning loss was social learning loss. Communication is key to learning and acquiring knowledge (Lave and Wenger, 1991). In a virtual classroom, organic interactions in students are no longer present, they are either put into “breakout rooms” to conduct compulsory academic conversations, or they simply do not interact with each other. Mr Allan has observed that students have become less sociable and more distant from their classmates after the pandemic. Mr. Allan spoke about the missed out on team-building opportunities and occasions such as Sports Day, School Outing, subject field trips, informal class gatherings, etc. However, those interactions are fundamental to peer relationships and the establishment of friendships. Teachers have expressed worries and sorrows for their students, Mr. Allan highlighted that students' social learning loss can only be resolved with time and life experiences.

4.4 The beginning of post-digital education

4.4.1 Digital participant observation: findings and highlights from fieldnotes

To understand how the experience of ERT has changed teachers in general, the interview asked about their current incorporation of digital means. Mr. John has kindly arranged for an online tutorial class for his students, I “sat in” the class using another device connected to John's account. My face was not shown, and my presence remained unknown to his students. He has always been utilizing two devices simultaneously, as it lets him check for any potential technical issues from a “participant” point of view. The field notes taken can be found below.

It was a 45-min Mathematics tutorial session with a class of 20, and the students were about to sit in the university entrance examination. When the lesson first started, John used about 2 min to take the attendance of his students. One of them was missing and the others immediately volunteered to contact him, and that student was online 5 min afterwards. During the lesson, students were quite attentive, they all turned on their cameras, and it clearly shows that the camera was pointing at themselves and their work desks; the entire class was very diligent, and they were doing math questions on their desks the whole time. In that particular lesson, John adapted the model of a flipped classroom, in which he arranged for a video explaining the concept of trigonometry and required his students to watch it and answer some questions on Google form. Two students did not do the assigned task, as they had forgotten about it. It was intriguing that those students told John the truth in a respectful way yet with a light tone, indicating that John has established a good teacher-student relationship with this class, and therefore students can freely express themselves, feeling in a safe and trusting environment (Fitria and Suminah, 2020). The software that was used was Teams, while John shared the screen with the class, every single student's camera and faces were shown surrounding the side of the screen. Instead of a breakout room for group work, John challenged these students with some advanced-level questions and encouraged them to pair up or to work as a team and attempt them. It seems that the students are very used to such a format, and one of them asked John “So we can use our phone?” John nodded and those students were then on their phones. When time was up, the six teams, which were grouped by the students themselves, came up with their answers. Four of them were right, and John invited some of them to show the steps and to demonstrate how they reached the answers. The entire class was very attentive, even to the ones who got the correct answer. The lesson went fast, by the end of the lesson, the students thanked John and some of them stayed and chitchat with John.

The above field notes illustrate some important elements and observable elements that deepen the understanding of online classes. John himself describes online classes as something that should not bring a difference in students' learning. As denoted by John

“There should not be a difference, digital tools or not, theoretically speaking, you should still be able to deliver the subject content effectively. What matters for me is how the knowledge is explained by the teacher, not the means that is used in the process, a worksheet shouldn't make your delivery more or less effective than a Google form.”

To achieve so, it requires the extra hard work and efforts of the teacher. In John's class, before the pandemic, he barely knew those students, as they had just been sorted into the same class for the 1st year of senior high school. The pandemic has made it difficult for students to bond with each other, but John has tried to work on that by having “after-class casual conversation sessions;” he set up an Instagram account just for his students and updated the page by posting short video clips/reels that explain common misconceptions in Maths. He also asks all his students how they are every day, sending mass messages to the entire class in private messages. He had to spend an extra hour to 2 h each day, to manage these interactions, so that he could develop a proper rapport with his students, and to have a healthy teacher-student relationship with them.

Online class observation has shown that his hard work has paid off. Students were communicative and attentive in the online classroom. John denoted that when the academic year first began, the students were relatively passive in the lesson, but their interactions with each other were quite ideal, he thinks that his strategies worked well and that students have also established good peer relationships with each other despite the physical distance. John added that a continuation of online classes would not be a problem for him, but it would not be his preference either, as developing rapport using digital means was too time-consuming. Yet, the incorporation of the flipped classroom and blended learning were more encouraged in his lessons, as he thought it was the only way for students' understanding of particular knowledge to be consistent, and it was also a way to ensure that his efforts were not wasted, as those learning materials could be reused again in other classes.

It is noteworthy that my other informants, Ms. Kayla and Ms. Nadia were not vast supporters of digital tools, yet the pandemic has strengthened their confidence and increased their competencies in using digital teaching tools. Both Kayla and Nadia teach primary school children, Kayla was particularly concerned about the harmful effects that digital tools might have on children's cognitive functional development (Small et al., 2020). Ms. Nadia was also reluctant to use Chromebooks in class before the pandemic, but the pandemic has made her feel more confident, and she now sees digitalization as a natural direction for education to proceed. The study by Nicolosi et al. (2023) revealed that younger teachers reported higher levels of negative emotions and less confidence in improving teaching skills during the pandemic. As demonstrated in the study of Lo (2024), student motivation and perception on independent learning could vary depending on their cultures, proper teachers' guidance which fosters autonomy and balances cultural differences enhances students' learning effectively. The feelings and self-efficacy are therefore crucial in the quality of education that teachers deliver. The informants in this study on the other hand, realized that they become more confident in online teaching after the pandemic, it may be a positive outcome of critical reflection and actions taken to increase digital literacy after realizing their own shortcomings. Ms. Nadia mentioned how she browsed Youtube videos about functions of Zoom and asked her husband to teach her ways to improve the resolution of the pictures that she shared in class through the screen.

Education is inevitably moving toward digitalization, especially in the digital era that we are in; and the pandemic has accelerated the process and footsteps of digitalization in education. Even though not all teachers were well-trained before the pandemic to deliver online classes, the pandemic has forced them to learn new skills and all my informants have become more digitally competent after the pandemic. Despite their initial reluctance toward using digital tools, most of them have decided to increase the portion of it in a traditional classroom, and most teachers have recognized that different types and portions of preparation work can be done to make online education a practical learning experience for students.

4.5 Transformative learning—embracing individuality

The last interview question concerns informants' views regarding teachers' obsolescence in the future, and the informants are pretty optimistic about the irreplaceability of teachers. In the process of their narrations, steps of transformative learning can be traced. In the year 2023, generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and image generation gained popularity once they became available to the public. The usage of ChatGPT has been discussed as a concerning phenomenon in the academic community, as it threatens intellectual property. Even in schools, teachers expressed concerns that students might abuse these readily available tools in doing their assignments. However, the informants can see a substantial weakness of AI, Mr. Allan noted the inaccuracy and inability to improvise based on the predicted emotional responses of users. Having said that, all informants use AI tools for lesson preparation, especially for classroom design, and rubrics writing for classroom activities. However, they all agree that further usage is not practical at this time, as high order thinking skills are not possible in these tools, thereby lacking the ability to replace teachers, who can think, feel and react based on students' responses and unspoken emotional clues and unique learning needs. For this reason, my informants are positive about teaching being sustainable in the future.

Another essential feature of the uniqueness of teachers is “teachers' voice;” as denoted by John, “It's up to the teachers. If you see it as a job, and you teach only the subject knowledge and nothing more, you are already replaceable now, AI or not, this type of teacher should not be working in a school. Teaching is not just a job, it's a vision and a mission, as long as you have that mindset, you cannot be replaced.” It may be true that students have access to the vastness of information online, and numerous sources of shadow educators. However, my informants pointed out that the feeling of being cared for is irreplaceable—when students feel that teachers genuinely care about them, not just their learning, but themselves as individuals, it is the foundation of a good teacher-student relationship (Kitchenham, 2008; Vighnarajah and Bakar, 2008; Keiler, 2018; Ma et al., 2022). To achieve so, teachers must recognize that “teaching is more than a job” and be able to see the teaching role as a vision, a mission that entitles them to connect with students while being their moral compass. Embracing individuality in both students and teachers, therefore, seems to be the key to avoiding being replaced by AI. Ms. Nadia described it as “the importance of enjoying my work and being passionate about teaching.” More than three informants described the key to bonding with students and connecting with them is by addressing one's human side, seeing students as individuals, to treating them as equals and with respect while demanding reciprocity—a quality that AI will not be able to achieve, at least until they can think and be able to handle moral dilemma.

Transformative learning was evident in all informants, Kayla and Nadia have become more digitally competent and have shifted their perspectives regarding digital tools. Even though Nadia still believes that digital tools could be harmful to the cognitive development of children, she is not reluctant to use them in class, “as long as it could help the students regain their interests in Spanish. As for Nadia, she has shifted her perspective from being reluctant to use Chromebooks, to using them more often and accepting that it is a natural development of education in the digital era that we are in today. Kelly and Allan did not have training in online teaching before, but the pandemic has also equipped them with some new skill sets. They all believe that the development of AI will not replace teachers, and they are hopeful about it since they see the intrinsic values of the subjects that they teach. They have all found their places in post-digital education, the pandemic allowed them to reflect deeply on their teaching identities and consolidated the perspective that teachers' irreplaceability stems from their emotionality, compassion and empathy (Lee et al., 2024). With the newly acquired narrative, these teachers have learnt to embrace their own, and their students' individuality and reintegrate into their teaching profession.

5 Discussion

This research has five key findings: (i) remote teaching anxiety experienced by teachers during the pandemic, (ii) the biggest challenge for teachers was maintaining a good teacher-student relationship and classroom management, (iii) severe learning loss and motivation loss observed in students, (iv) teachers are still relying on digital tools in class after the pandemic and have accepted that education has been digitized, and (v) Transformative learning is evident in these teachers, and they pointed out the importance of embracing one's individuality to combat the era of artificial intelligence. Some key emotions have been identified in the interviews, as the interviews are conducted after the pandemic is over, when teachers are asked to describe their emotional experience during then, the emotions they described are naturally the ones they identified as they protruded. In terms of tackling those emotions directly, as shown in Figure 1, these teachers' initial response to their feelings was to suppress them. This also echoes to Morris and Feldman's (1996) emotional labor, particularly on emotional display rules. These teachers could not directly express their negative emotions such as confusion, anxiety and stress to their students, as these negative emotions are against the perceived emotional display rules that teachers should have. Some teachers tried to tackle the feelings by talking with their colleagues, and it seemingly helped them feel better in the beginning.

Critical self-reflection requires individuals to look reflexively into their thoughts and to examine their values (Mezirow, 2000a). When informants were describing their experiences, they described the self-doubts they had when ERT first began, and some denoted a slight sense of guilt for not knowing online teaching before the pandemic (Ross and DiSalvo, 2020; Russell, 2020; Schwenck and Pryor, 2021; Stewart, 2021). As the informants recalled their experiences, they also engaged in critical self-reflection, and some mentioned critical self-reflection during ERT. In the interview process, the second question asks about the most significant challenge and how it was overcome. My informants pointed to the same challenge, which is the teacher-student relationship and effective classroom management. This has also been mentioned by previous researchers who studied teachers' wellbeing during the pandemic (Laidlaw, 2023; Oxley et al., 2023; Tatum, 2023, etc.). In this study, these informants were asked to describe their emotions and feelings during and after the challenge, which is a process that triggers them to examine their underlying values and beliefs. As they recalled their experience, it is shown that they had gone through the mental stages as well during the pandemic. Some informants talked about their disbelief in online teaching, and their doubts on whether their students were attentive in their lessons. It is shown in their recount of experience that they overcame them by putting more trust on their students, and some of them even actively opened an Instagram account just to connect with his students in a better way. They realized that they had some biases against online learning, and since the pandemic has made it inevitable, it forced them to re-examine their existing beliefs and restructure them into a new focus, which is to employ digital means in connecting with their students, so as to develop more effective communication thereby improving classroom management. Although researchers have also had similar findings regarding how digital communication could aid students' learning (Kim et al., 2014; Jahnke, 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Mir et al., 2023, etc.), this research looks specifically at the struggles of teachers during the process of searching for solutions.

The pandemic might be over, but the impacts of ERT are still unfolding. These teachers have observed learning losses in their students, including having less passion and interests in lessons, and difficulties in socializing with peers, etc. This also parallels to the findings of researchers who studied the impacts of online learning after the pandemic (Zhang et al., 2022; Aliyyah et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2023; Song and Park, 2021; Fitria, 2021; Koutsouba et al., 2021, etc.). However, this study delineates the worries and sense of helplessness that teachers have experienced within the turmoil. Instead of blaming their students, they actively searched for solutions and realized that incorporating digital means such as interactive online games on Kahoot, blended learning, and even posting videos on social media which explain subject content have helped students regain interest in class, and in some cases, improved their communication skills as they were more actively sharing their opinions with their peers and the teachers. This is itself the process of the new frame of reference as a reintegration into life—these teachers who initially did not rely on digital tools, after experiencing the pandemic, are actively incorporating digital elements in and out of the classroom.

Additionally, the new frame of reference is also evident in the teachers' acknowledgment of the digital era that educators are working in. Their attitudes are pretty positive, accepting and a lot less anxious as compared to when they described their dominant emotions during the pandemic. Current literature has covered the benefits of online learning (Alsayed and Althaqafi, 2022; Fiorini et al., 2022; Chojczak and Starford, 2023; Haugsbakken et al., 2023; etc.), teachers' attitudes about online teaching and emergency remote teaching the pandemic (Kundu and Bej, 2021; Karakus and Gürbüz, 2022; Evangelou, 2023; Karaca and Akyuz, 2024, etc.); and ways to improve online learning such as instructions, improvement of teachers' digital literacy, etc. (Hickey, 2022; Yin, 2022; Gurvich, 2023; Kanchana et al., 2023). However, this research denotes the emotional experience and the transformation of teachers who have experienced the pandemic and how that brings changes to their views about digital tools and online teaching in general.

The last part of the interview shows that teachers are primarily unbothered, hopeful and quite passionate about the prospect of the teaching field. Although new frames of reference have been introduced to these teachers, the experience of the pandemic has also consolidated their belief and enthusiasm of teachers' mission. The informants mentioned that teaching is a mission and is more than just a job; this view has become even stronger since the pandemic helped them understand that students do need teachers to use technology in an effective way to help them learn. During the pandemic, students were physically away from teachers, but access to the Internet and artificial intelligence have always been there. However, according to my informants, many students still preferred going to them when they encounter academic and personal issues. It was also this type of interaction that gave my informants the opportunity to reflect on their roles as a teacher, and the mental strength to overcome the negative emotions they have experienced during the pandemic. This has brought a more refined frame of reference, particularly about their roles as teachers, and that led them to the state of confidence and the belief that as long as teachers embrace individuality of themselves and of their student, they will not be obsolete in the era of machines and artificial intelligence. Existent research focuses on how teachers could incorporate AI in their classrooms and the ways in which AI could be used to develop a better learning environment (Chiu et al., 2023; Su and Yang, 2023; Veletsianos et al., 2024; Younis, 2024). However, this study reveals that while teachers agree with using digital tools in their classrooms, embracing them does not necessarily signify that teachers will become obsolete in the near future.

6 Research implications

This research uses digital ethnography and in-depth interviews, it analyses the narratives of five teachers working in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Canada. The focus of the study is the emotionality and the emotional experiences of these teachers during the pandemic and in the post-pandemic times. Using the model of Pekrun et al. (2007), classroom emotions are explored in both online and offline settings, it is suggested in this study that regulation of achievement emotions could be applied to teachers. The theoretical framework of transformative learning theory is incorporated with it, allowing a systematic delineation of teachers' emotional experiences in the process of transformative learning.

The study has identified five themes using thematic analysis, they correspond to the research questions asked in the survey, and a specific emotion is commonly described among the informants. The themes include remote teaching anxieties; teacher-student relationship & classroom management; learning losses of students; the beginning of post-digital education; transformative learning—embracing individuality. At the beginning of ERT, teachers were in a deep state of confusion and a sense of helplessness (Kaufmann and Vallade, 2020). Teachers were unfamiliar with online teaching and anxious about students' learning progress. As described by Ms. Kayla, “My students did respond to me in class, but I don't know if they are catching on. I don't know how to create polls on Zoom, so when I ask questions, they are the direct and easy ones, and mostly for checking if they are there, but I can't see their faces and observe the presence of confusion or boredom.” Full-scale remote teaching was a disorienting dilemma that disrupted teachers' familiar social realities (Mezirow, 2000b; Beatty, 2019; Akbana and Dikilitaş, 2022). Teachers identified the emotions, and they took corresponding actions, some of them concealed and suppressed the negativity, while others addressed them by discussing the issue with their colleagues (Izhar et al., 2021) and supervisors (Gnawali, 2020; Andrews, 2022). Applying Pekrun et al. (2007) model, emotion-oriented regulation managed emotional dissonance (Pekrun et al., 2007, p. 29). These teachers have experienced intense emotions such as anxiety and frustration, which caused them to reflect on themselves and their existent values critically. This is the second step of achievement emotions regulation—appraisal-oriented regulation. These teachers identified their biases against online teaching and acknowledged the need to improve their digital literacy to benefit their students' learning (Mezirow, 2000b; Jarvis, 2012; Calleja, 2014; Gnawali, 2020).

7 Conclusion

As discussed in this study, teachers continued to look for strategic ways to balance discipline and trust with their students, while they became more open-minded to accept constructive feedback from students, they also tried other methods such as setting up social media accounts to maintain good teacher-student relationships during the pandemic (Cairns et al., 2020; Castelli and Sarvary, 2021; Centeio et al., 2021). This demonstrates a new frame of reference being established and put into practice. At the same time, as teachers more actively seek digital tools to increase classroom dynamics and varieties of classroom activities, they are also performing competence-oriented regulation (Schutz and Pekrun, 2007, p. 29). As teachers carried on incorporating flipped classrooms and blended learning during the post-pandemic times, it shows that they have reintegrated the newly acquired knowledge into the design of academic environments and turned them into more interactive and practical learning spaces for their students (Brosch, 2021; Schwenck and Pryor, 2021; Day, 2021; Kuhfeld et al., 2023). More importantly, it is revealed in this study that teachers have achieved transformative learning on the level of self-perception. In the digital age and the post-digital education era, the emotional experiences brought about by the pandemic allowed these teaching individuals to reflect on their values and roles as teachers critically. The importance of “embracing individuality,” both of teachers themselves and students, has been identified as the key that distinguishes them from AI, and it is precisely this humanness that exists in teachers that makes them irreplaceable (Barbour et al., 2020; Benade, 2020; Ross and DiSalvo, 2020; Russell, 2020; Schwenck and Pryor, 2021; Stewart, 2021; Dolighan and Owen, 2021; Brookfield et al., 2022). This study hopes to shed light on the importance of teachers regulating their emotions and becoming aware of the emotional dynamic in the classroom and how that could affect students' learning. Instead of denying the emotions, teachers should embrace them and utilize them in a way that creates a positive and encouraging learning environment for their students, emotional exchange could also help teachers connect with students and co-develop an emotionally safe environment for both of them and ultimately benefitting students' learning.

An important implication of this research is to magnify the humanistic nature of teaching, and, through analyzing the narratives in the storytelling of five individuals, to demonstrate that transformative learning might likely be the only path to transcendence (Beatty, 2019). Emotions should not be viewed as a barrier to professionalism, emotions are fundamental, humanistic elements that teachers inevitably have (Lindholm, 2007; Kitchenham, 2008; Chen, 2020; Choi et al., 2021). To address them and to manage them, this study shows the possibility of expanding and incorporating Perkun's management of achievement emotions into Mezirow's transformative learning theory. To embrace transformative learning, reflection and critical self-reflection must be consistently performed. Emotions are essential traits of humans and are significant but subtle traces of learning that take place in us, especially in transformative learning. Education will likely carry on in this digitized direction, but teaching quality will only be guaranteed if teachers actively increase digital competencies and digital literacy and reflectively incorporate technology-based teaching in an engaging and meaningful way to engage students. Lo et al. (2024) showed that goal setting and resource management played significant roles in university students' independent learning skills and motivation, further echoing to Pekrun (2006, 2022)'s emphasis on the important role that teachers have in creating an motivating and rewarding learning environment. This study has demonstrated the possibilities of embracing emotionality and individuality as the key to quality education and maintaining the irreplaceability of teachers in the journey of students' learning—whether teachers will become obsolete in the future is in the hands of teachers themselves.

Teaching is more than just a job; the pandemic has made everyone realize and feel this profoundly. Just as remarked by Mr. John, who is a passionate educator, “Teaching is not a job; it is a mission. The students will likely not remember what you teach them in class, but even decades later, they will still remember that a good teacher once cared so deeply for him/her.” Digitization of education has just begun, and it seems likely that the development of artificial intelligence will continue to thrive. As we co-exist with AI and digitization, we need to keep track of the changes they bring to education. It is suggested in this study that the emotional experience and the ability to feel, think, and empathize should be embraced. Still, there is a need to examine further the possibilities of systematically incorporating these skills in teacher education. Most importantly, the correlation of emotions, transformative learning and management of classroom emotions should continue to be explored, as emotions make us human.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. For the publication fee, we acknowledge financial support by the Heidelberg University.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akbana, Y. E., and Dikilitaş, K. (2022). EFL teachers' sources of remote teaching anxiety: insights and implications for EFL teacher education. Acta Educ. Gener. 12, 157–180. doi: 10.2478/atd-2022-0009

Aliyyah, R. R., Rasmitadila, N., Gunadi, G., Sutisnawati, A., and Febriantina, S. (2023). Perceptions of elementary school teachers towards the implementation of the independent curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Learn. Res. 10, 154–164. doi: 10.20448/jeelr.v10i2.4490

Alsayed, R. A., and Althaqafi, A. S. A. (2022). Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: benefits and challenges for EFL students. Int. Educ. Stud. 15:122. doi: 10.5539/ies.v15n3p122

Andrews, R. L. (2022). “Teacher and supervisor assessment of principal leadership and academic achievement,” in School Effectiveness and School Improvement (London: Routledge), 211–219. doi: 10.1201/9780203740156-17

Barbour, M. K., LaBonte, R., Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., et al. (2020). Understanding Pandemic Pedagogy: differences between emergency remote, remote, and online teaching. Virginia Tech. Available at: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/101905 (accessed August 15, 2024).

Beatty, A. (2019). Emotional Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781139108096

Benade, L. (2020). “Is the classroom obsolete in the twenty-first century?” in Design, Education and Pedagogy (London: Routledge), 6–17. doi: 10.1201/9781003024781-2

Brookfield, S. D., Rudolph, J., and Tan, S. (2022). Powerful teaching, the paradox of empowerment and the powers of Foucault. An interview with Professor Stephen Brookfield. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 5:12. doi: 10.37074/jalt.2022.5.12

Brosch, T. (2021). Affect and emotions as drivers of climate change perception and action: a review. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 42, 15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.001

Cairns, M. R., Ebinger, M., Stinson, C., and Jordan, J. (2020). COVID-19 and human connection: collaborative research on loneliness and online worlds from a socially-distanced academy. Hum. Organ. 79, 281–291. doi: 10.17730/1938-3525-79.4.281

Calleja, C. (2014). Jack Mezirow's conceptualisation of adult transformative learning: a review. J. Adult Cont. Educ. 20, 117–136. doi: 10.7227/JACE.20.1.8

Castelli, F. R., and Sarvary, M. A. (2021). Why students do not turn on their video cameras during online classes and an equitable and inclusive plan to encourage them to do so. Ecol. Evol. 11, 3565–3576. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7123

Centeio, E., Mercier, K., Garn, A., Erwin, H., Marttinen, R., and Foley, J. (2021). The success and struggles of physical education teachers while teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 40, 667–673. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2020-0295

Chen, J. (2020). Refining the teacher emotion model: evidence from a review of literature published between 1985 and 2019. Cambridge J. Educ. 51, 327–357. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2020.1831440

Chen, L., Gillan, J., Decker, M., Eteffa, E., Marzan, A., Thai, J., et al. (2023). Embedding digital data storytelling in introductory data science course. J. Problem Based Lear. Higher Educ. 11, 126–152. doi: 10.54337/ojs.jpblhe.v11i2.7767

Chiu, T. K., Moorhouse, B. L., Chai, C. S., and Ismailov, M. (2023). Teacher support and student motivation to learn with Artificial Intelligence (AI) based chatbot. Inter. Lear. Environ. 32, 3240–3256. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2023.2172044

Choi, H., Chung, S., and Ko, J. (2021). Rethinking teacher education policy in ICT: lessons from emergency remote teaching (ERT) during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Korea. Sustainability 13:5480. doi: 10.3390/su13105480

Chojczak, D., and Starford, A. (2023). Interactive methods used in collaborative writing in the online ESL classroom. Deleted J. 39, 5–26. doi: 10.61504/CZKC7151

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. New York: Sage Publications, Inc.

Davis, T. E. K., Sokan, A. E., and Mannan, A. (2023). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on students in institutions of higher education. Higher Educ. Stud. 13:20. doi: 10.5539/hes.v13n2p20

Day, J. V. C. (2021). Lights, camera, action? A reflection of utilizing web cameras during synchronous learning in teacher education. Teacher Educ. J. 14, 3–21.

Dolighan, T., and Owen, M. (2021). Teacher efficacy for online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brock Educ. J. 30:95. doi: 10.26522/brocked.v30i1.851

Evangelou, F. (2023). Views of Greek teachers on the implementation of teaching approaches in online classrooms. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 7, 152–166. doi: 10.46328/ijtes.441

Fiorini, L. A., Borg, A., and Debono, M. (2022). Part-time adult students' satisfaction with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 28, 354–377. doi: 10.1177/14779714221082691

Fitria, H., and Suminah, S. (2020). Role of teachers in the digital instructional era. J. Soc. Work Sci. Educ. 1, 70–77. doi: 10.52690/jswse.v1i1.11

Fitria, T. N. (2021). “Artificial intelligence (AI) in education: using AI tools for teaching and learning process,” in Prosiding Seminar Nasional and Call for Paper STIE AAS, 134–147.

Gadamer, H.-G. (2003). Truth and Method (2nd ed.). London: The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

Gnawali, L. (2020). “Embedding digital literacy in the classroom,” in Developing Effective Learning in Nepal: Insights Into School Leadership, Teaching Methods and Curriculum, 90–93.

Gurvich, R. (2023). Enhancing online instruction through better interactions. J. Educ. Online 20:9. doi: 10.9743/JEO.2023.20.4.9

Haugsbakken, H., Nykvist, S., and Lysne, D. A. (2023). The need to focus on digital pedagogy for online learning. Eur. J. Educ. 6, 52–62. doi: 10.2478/ejed-2023-0005

Hermino, A., and Arifin, I. (2020). Contextual character education for students in the senior high school. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 9, 1009–1023. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.9.3.1009

Hickey, D. T. (2022). Situative approaches to online engagement, assessment, and equity. Educ. Psychol. 57, 221–225. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2022.2079129

Hubalovsky, S., Hubalovska, M., and Musilek, M. (2019). Assessment of the influence of adaptive E-learning on learning effectiveness of primary school pupils. Comput. Human Behav. 92, 691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.033

Izhar, N. A., Al-Dheleai, Y. M., and Na, K. S. (2021). Teaching in the time of COVID-19: the challenges faced by teachers in initiating online class sessions. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 11, 1294–1306. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v11-i2/9205

Jahnke, I. (2022). Quality of digital learning experiences – effective, efficient, and appealing designs? Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 40, 17–30. doi: 10.1108/IJILT-05-2022-0105

Jarvis, C. (2012). “Fiction and film and transformative learning,” in The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice, 486–502.

Kanchana, J. D., Amarasinghe, G., Nanayakkara, V., and Perera, A. S. (2023). A set of essentials for online learning: CSE-SET. Disc. Educ. 2:4. doi: 10.1007/s44217-023-00037-y

Karaca, E., and Akyuz, D. (2024). Facilitating online learning environment in math classes: Teachers views and suggestions. J. Pedag. Res. 20:581 doi: 10.33902/JPR.202426581

Karakus, G., and Gürbüz, O. (2022). Investigating K-12 teachers' views on online education. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. Int. J. 14, 202–222. doi: 10.34105/j.kmel.2022.14.012

Kaufmann, R., and Vallade, J. I. (2020). Exploring connections in the online learning environment: student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Inter. Learn. Environ. 30, 1794–1808. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1749670

Keiler, L. S. (2018). Teachers' roles and identities in student-centered classrooms. Int. J. STEM Educ. 5:34. doi: 10.1186/s40594-018-0131-6

Kim, M. K., Kim, S. M., Khera, O., and Getman, J. (2014). The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: an exploration of design principles. Internet Higher Educ. 22, 37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.04.003

Kitchenham, A. (2008). The evolution of John Mezirow's transformative learning theory. J. Transform. Educ. 6, 104–123. doi: 10.1177/1541344608322678

Koutsouba, M., Koutsouba, K., and Giossos, Y. (2021). Elements of unfairness in e-learning distance higher education in covid-19 era. Ανοικτή Εκπαίδευση Το Περιοδικό Για Την Ανοικτή Και Εξ Αποστάσεως Εκπαίδευση Και Την Εκπαιδευτική Τεχνολογία 17, 64–79. doi: 10.12681/jode.27008

Kuhfeld, J. S. M., Lindsay Dworkin, K. L., Emily Markovich Morris, L. N., Erin Castro, M. H., Darrell, M., and West, J. B. K. (2023). The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up? Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-pandemic-has-had-devastating-impacts-on-learning-what-will-it-take-to-help-students-catch-up/ (accessed August 12, 2024).

Kundu, A., and Bej, T. (2021). We have efficacy but lack infrastructure: teachers' views on online teaching learning during COVID-19. Quality Assur. Educ. 29, 344–372. doi: 10.1108/QAE-05-2020-0058

Laidlaw, J. (2023). Canadian music teachers' burnout and resilience through the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Canad. J. Educ. Admin. Policy 203, 102–116. doi: 10.7202/1108435ar

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. New York, NJ: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lee, J. S., Xie, Q., and Lee, K. (2024). Informal digital learning of English and L2 willingness to communicate: roles of emotions, gender, and educational stage. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 45, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2021.1918699

Lindholm, C. (2007). “An anthropology of emotion,” in A companion to psychological anthropology: modernity and psychocultural change, eds. C. Casey, and R. B. Edgerton (London: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.), 30–47.

Lo, N. P. (2024). Cross-cultural comparative analysis of student motivation and autonomy in learning: perspectives from Hong Kong and the United Kingdom. Front. Educ. 9:1393968. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1393968

Lo, N. P., Bremner, P. A. M., and Forbes-McKay, K. E. (2024). Influences on student motivation and independent learning skills: cross-cultural differences between Hong Kong and the United Kingdom. Front. Educ. 8:1334357. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1334357

Ma, K., Liang, L., Chutiyami, M., Nicoll, S., Khaerudin, T., and Van Ha, X. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic-related anxiety, stress, and depression among teachers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Work 73, 3–27. doi: 10.3233/WOR-220062

Mezirow, J. (1989). Transformation theory and social action: a response to collard and law. Adult Educ. Quart. 39, 169–175. doi: 10.1177/0001848189039003005

Mezirow, J. (2000a). Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000b). “Learning to think like an adult. Core concepts of transformation theory,” in Learning as Transformation. Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress, eds. J. Mezirow, and Associates (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 3–33.

Mezirow, J. (2012). “Learning to think like an adult. Core concepts of transformation theory,” in The Handbook of Transformative Learning. Theory, Research, and Practice, 73–95.

Mezirow, J., and Taylor, E. W. (2009). “Transformative learning in practice: insights from community, workplace, and higher education,” in Jossey-Bass eBooks. Available at: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB00308958 (accessed August 12, 2024).

Mir, N. A., Fathima, A., and Suppala, S. (2023). A new paradigm for blended learning. Int. J. Adult Educ. Technol. 14, 1–10. doi: 10.4018/IJAET.321654

Moore, S., and Hodges, C. B. (2023). Emergency Remote Teaching. New York: EdTechnica. doi: 10.59668/371.11681

Morris, J. A., and Feldman, D. C. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Acad. Manag. Rev. 21:986. doi: 10.2307/259161

Naylor, D., and Nyanjom, J. (2021). Educators' emotions involved in the transition to online teaching in higher education. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 40, 1236–1250. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1811645

Nicolosi, S., Alba, M., and Pitrolo, C. (2023). Primary school teachers' emotions, implicit beliefs, and self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Sports Active Living 4:1064072. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2022.1064072

Oxley, L., Asbury, K., and Kim, L. E. (2023). The impact of student conduct problems on teacher wellbeing following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br. Educ. Res. J. 50, 200–217. doi: 10.1002/berj.3923

Pangrazio, L., Godhe, A., and Ledesma, A. G. L. (2020). What is digital literacy? A comparative review of publications across three language contexts. E-Learn. Digital Media 17, 442–459. doi: 10.1177/2042753020946291

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 18, 315–341. doi: 10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: from achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 36:83. doi: 10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., and Perry, R. P. (2007). “The control-value theory of achievement emotions: an integrative approach to emotions in education,” in Emotion in Education, eds. P. A. Schutz and R. Pekrun (Elsevier Academic Press), 13–36. doi: 10.1016/B978-012372545-5/50003-4

Pekrun, R., and Marsh, H. W. (2022). Research on situated motivation and emotion: Progress and open problems. Learn. Instr. 81:101664. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101664

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., and Tacchi, J. (2015). Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. London: SAGE.

Pressley, T. (2021a). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Resear. 50, 325–327. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211004138

Pressley, T. (2021b). Returning to teaching during COVID-19: an empirical study on elementary teachers' self-efficacy. Psychol. Sch. 58, 1611–1623. doi: 10.1002/pits.22528

Remmi, F., and Hashim, H. (2021). Primary school teachers' usage and perception of online formative assessment tools in language assessment. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progr. Educ. Dev. 10:2235. doi: 10.6007/IJARPED/v10-i1/8846

Ross, A. F., and DiSalvo, M. L. (2020). Negotiating displacement, regaining community: the harvard language center's response to the COVID-19 crisis. Foreign Lang. Ann. 53, 371–379. doi: 10.1111/flan.12463

Russell, V. (2020). Language anxiety and the online learner. Foreign Lang. Ann. 53, 338–352. doi: 10.1111/flan.12461

Salama, R., and Hinton, T. (2023). Online higher education: current landscape and future trends. J. Further Higher Educ. 47, 913–924. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2023.2200136

Schwenck, C. M., and Pryor, J. D. (2021). Student perspectives on camera usage to engage and connect in foundational education classes: it's time to turn your cameras on. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2:100079. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100079

Singh, R. (2016). Learner and learning in digital era: some issues and challenges. Int. Educ. Res. J. 2:508.

Small, G. W., Lee, J., Kaufman, A., Jalil, J., Siddarth, P., Gaddipati, H., et al. (2020). Brain health consequences of digital technology use. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 22, 179–187. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/gsmall

Song, J., and Park, M. (2021). Emotional scaffolding and teacher identity: two mainstream teachers' mobilizing emotions of security and excitement for young English learners. Int. Multil. Res. J. 15, 253–266. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2021.1883793

Sprick, R., Sprick, J., Edwards, J., and Coughlin, C. (2021). Champs: A Proactive and Positive Approach to Classroom Management Third Edition. Eugene: Ancora Publishing.

Stewart, W. H. (2021). A global crash-course in teaching and learning online: a thematic review of empirical Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) studies in higher education during Year 1 of COVID-19. Open Praxis 13:89. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.13.1.1177

Su, J., and Yang, W. (2023). Unlocking the power of ChatGPT: a framework for applying generative AI in education. ECNU Rev. Educ. 6, 355–366. doi: 10.1177/20965311231168423

Taguchi, N. (2020). Digitally mediated remote learning of pragmatics. Foreign Lang. Ann. 53, 353–358. doi: 10.1111/flan.12455

Tatum, A. (2023). Exploring teachers' well-being through compassion. Impact. Educ. J. Transfor. Prof. Pract. 8, 23–31. doi: 10.5195/ie.2023.325

Taylor, E. (2000). Fostering Mezirow's transformative learning theory in the adult education classroom: a critical review. Canad. J. Study Adult Educ. 14, 1–28. doi: 10.56105/cjsae.v14i2.1929

Taylor, E. W. (2017). Transformative Learning Theory. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 17–29. doi: 10.1007/978-94-6300-797-9_2

Taylor, E. W., and Cranton, P. (2012). The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice. London: John Wiley and Sons.