95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 24 January 2025

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1478472

This article is part of the Research Topic Inclusive Education in Intercultural Contexts View all 8 articles

Following the current rise of cross-sector networks in education, we take a closer look at the supply side in the field of cultural education in Germany. We consider goal diversity in cross-sector collaborations and aim to provide insights into the group-specific goals of actors in the initial phase of collaborations. Using the lens of collaborative governance, collaborative engagement, and goal diversity research, we conducted 24 semi-structured interviews which we analyzed using thematic qualitative content analysis. We identified distinct goals for each of the five participating groups. These goals can be assigned to the macro, meso, and micro levels of the network, providing information about the direction of the goals and emphasizing the dynamic interplay of goals and their implications for collaborative dynamics. Future research could determine whether the results can be found in other contexts.

In recent years, educational networks have grown significantly as actors from various sectors collaborate to promote equal opportunities and social cohesion. Cultural and arts education (referred to as cultural education in the following), crucial for addressing societal challenges such as socioeconomic disparities and social polarization (Jessop, 2017; Le et al., 2015; Liebau, 2018), is predominantly studied within formal school curricula (Dumitru, 2019). However, some countries have witnessed a decline in arts subjects, affecting access to cultural education across different social strata (Fobel and Kolleck, 2021; Neelands et al., 2015; Winner et al., 2013). Therefore, collaborations between formal and non-formal cultural education sectors with access to groups that are affected are increasingly pivotal in addressing these challenges (Gigerl et al., 2022). Current cultural funding programs in Germany prioritize strengthening local cultural education structures through diverse sectoral engagement (BMBF, 2021; European Commission, 2021). Cross-sector collaborations encounter challenges such as different communication styles, organizational diversity, and trust-building with geographically dispersed partners (Babiak and Thibault, 2009; Bardach, 2001; Bryson et al., 2015), which can impede collaborative success and warrant further empirical explanation (Castañer and Oliveira, 2020; Huxham and Vangen, 2000). With expertise and knowledge now distributed across multiple organizations and networks (e.g., Pearce and Conger, 2002; Clarke, 2018), identifying common goals becomes crucial for effective collaboration (Bryson et al., 2015, p. 649). Conflicting goals within networks may lead to competition and hinder progress (Castañer and Oliveira, 2020; Huxham and Vangen, 2000; Picot et al., 2023), leading to complex collaborative governance (Gugu and Dal Molin, 2016; Head, 2008; Saz-Carranza and Ospina, 2011).

Research on organizational goals in collaborations and networks, particularly in the cultural sector, remains limited (Schelling, 1980; Schöttle and Tillmann, 2018). Particularly in the cultural sphere, research has focused on the topic of participation (Fobel and Kolleck, 2021; Zimmer and Kolleck, 2024), students’ participation in school in general (Sousa and Ferreira, 2024), on framework conditions and infrastructure of cultural education (Büdel and Kolleck, 2023; Fobel, 2022), on factors that strengthen collaborative efforts, such as trust and sense of place (Le and Kolleck, 2022a, 2022b), and on collaborative learning for arts education (Gigerl et al., 2022). The supply side with a focus on factors that promote the sustainability of cross-sector collaborations itself has mostly been neglected so far.

This article aims to provide insights into group-specific goals in cross-sector cultural education collaborations. The study, conducted in German municipalities, uses qualitative methods to explore collaborative governance, stakeholder engagement, and goal diversity. Results highlight varied goals across network levels, contributing to understanding the complexities of cross-sector collaboration in cultural education. The paper concludes by discussing the implications of these findings, acknowledging study limitations, and suggesting avenues for future research.

One aspect that significantly influences cross-sector collaboration is governance structures (Moirano et al., 2020, p. 12). Cross-sector collaboration typically operates within a framework of collaborative governance, where decision-making authority is distributed among stakeholders from various sectors (Emerson et al., 2012). By integrating diverse perspectives, expertise, and resources into the decision-making process, the success of cross-sector collaborations is enhanced (Weber et al., 2022). However, little research has explored the inclusion of diverse participant groups as a critical element of successful interorganizational partnerships in education. One example are Straub and Ehmke (2021), who identified four types of team members for various actor groups across the teacher education system, demonstrating differences in ascribed importance of factors such as perceived trustworthiness or collective ownership of goals. In general, heterogeneity may arise in terms of goals, competencies, skills, knowledge bases, power dynamics, perceptions, and cultures (Corsaro et al., 2012). This description also applies to our target group (see details in chapter 3), referencing Emerson et al. (2012) who define collaborative governance as:

The processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished (p. 2).

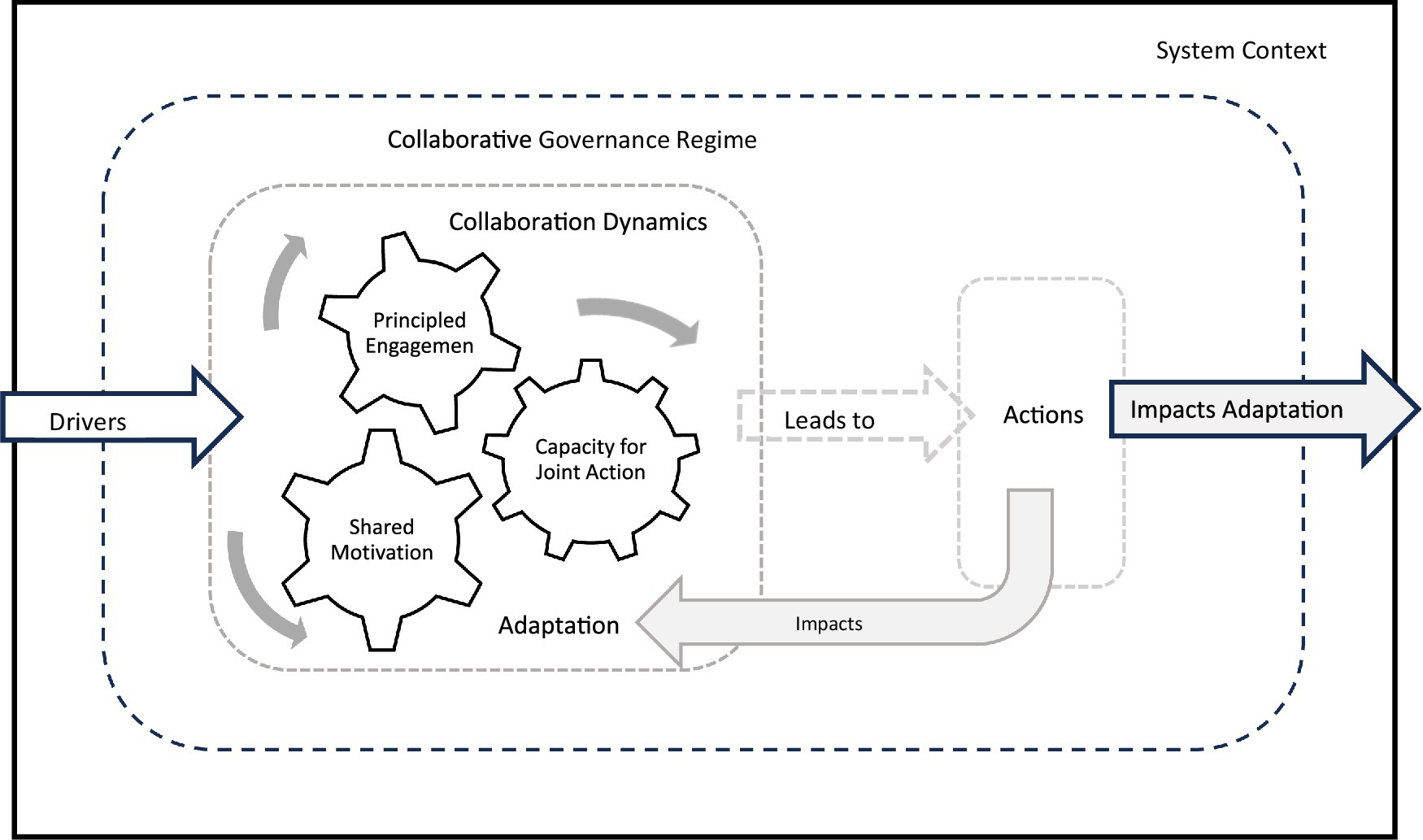

Emerson et al. (2012) developed an integrative framework for collaborative governance (see Figure 1), encompassing three dimensions: collaboration dynamics, collaborative governance regime (CGR) and system context (p. 6). This framework illustrates a broader system context influenced by political, legal, and socioeconomic conditions, with all dimensions interconnected. These dynamics collectively guide collaborative actions, aimed at achieving the shared purpose of the CGR (Emerson et al., 2012).

Figure 1. The integrative framework for collaborative governance (own figure according to Emerson et al. (2012), p. 6).

Key collaborative dynamics, including diverse perspectives, enrich the collaborative process despite “differing content, relational, and identity goals” (Emerson et al., 2012, p. 10). Shared motivation emphasizes interpersonal and relational aspects within collaborative dynamics, often initiated through principled engagement. These factors, among others, constitute “a collection of cross-functional elements that come together to create the potential for taking effective action” (Saint-Onge and Armstrong, 2004, p. 19).

Research consistently highlights stakeholder engagement as crucial for successful cross-sector collaborations (Acero et al., 2024; Huynh et al., 2023; Reed et al., 2018). Engagement involves active participation in decision-making processes that affect stakeholders. Success depends on institutional structures, available resources, a supportive culture, prior engagement experiences, and the capacities, needs and desires of the stakeholders involved (Eaton et al., 2021; Gugu and Dal Molin, 2016; Reed et al., 2018), alongside drivers of collaborative dynamics (Emerson et al., 2012).

In the Integrated Framework for Collaborative Governance (CGR), the identity and roles of actors are pivotal (Emerson et al., 2012, p. 11). Actors represent diverse entities such as themselves, constituencies, public agencies, NGOs, communities, or the public, each contributing unique expertise, resources, values, and goals to the collaboration (Bardach, 2001). Maintaining high levels of engagement ensures continued commitment, fosters creative problem-solving, sustainable solutions (Emerson and Nabatchi, 2015), and builds trust and mutual understanding (Harris and Albury, 2009).

Active engagement catalyzes resource mobilization, creating dynamic synergy that surpasses individual contributions (Bryson et al., 2016), enhancing collaboration by bolstering trust and resilience (Harris and Albury, 2009). Stakeholders’ motivations to participate hinge on perceiving a direct link between their involvement and effective outcomes (Ansell and Gash, 2008). Additionally, autonomous motivation strengthens collaborative efforts and leads to enhanced work satisfaction in general (Kolleck, 2019). Conversely, incentives to collaborate diminish when stakeholders input is seen as merely advisory (Futrell, 2003). Aligning diverse goals of participating actors is crucial for merging resources effectively (Baraldi and Strömsten, 2009), yielding collaborative advantages (Bryson et al., 2016).

Various scholars emphasize the importance of mutual understanding of goals and motives for successful cross-sector collaborations (Amabile et al., 2001; Bronstein, 2003; Katzenbach and Smith, 1996). Goals are future desired states that individuals strive to achieve through their competences and goal-oriented behavior (Kleinbeck and Kleinbeck, 2009), profoundly influencing human behavior (Elliot and Fryer, 2008). Goal alignment among stakeholders – shared, organizational, and individual – is crucial for effective collaboration dynamics (see Figure 1).

Bryson et al. (2016) categorize goals into organizational core goals, core goals shared across organizations, public value goals beyond core goals, negative-avoidance goals, negative public value consequences beyond shared core goals, and not-my-goals (Bryson et al., 2016, p. 914), stressing the need for alignment to maximize cross-sector collaboration potential. Their model advocates a holistic approach covering discovery, adaptation, commitment, and accomplishment, providing a strategic roadmap in dynamic landscapes.

Organizational, sectoral, or individual goals may diverge from jointly defined project goals (Bryson et al., 2015; Castañer and Oliveira, 2020; Meads et al., 2005; Winkler, 2006), sometimes remaining undisclosed during collaboration despite being critical in emerging conflicts (Bryson et al., 2015). Diversity in participation can enhance group processes but also introduces tensions such as autonomy vs. interdependence or self-interest vs. collective interest (Mannix and Neale, 2005). Vangen and Huxham (2012) describe a goals framework that captures goals in the collaboration arena as a tangled web of dynamic, ambiguous, and partially overlapping goal hierarchies. It thus suggests that a large variety of goals influence actions and behaviors in collaboration (p. 752). Furthermore, they distinguish between six dimensions of goals in collaboration, which are level, origin, authenticity, relevance, content and overtness. The tension between goal congruence and goal diversity is particularly important for the level and content dimension (Vangen and Huxham, 2012, p. 753) which we will discuss later in the results of our study.

Castañer and Oliveira (2020) made an attempt to differentiate goals and distinguish between the following three types of individual goals in collaborations:

1. To feel like a ‘good citizen’ to satisfy one’s own moral standards without expecting the partner’s reciprocity – the moral or principled-selfish way.

2. To ensure that the helped partners recognizes the assistance and feels indebted, perhaps increasing reciprocity and commitment toward the IOR (Das and Teng, 1998, 2000) – the instrumental way.

3. To establish a reputation for being a good partner and hence being able to attract new partners (Williamson, 1993) – the reputational way (Castañer and Oliveira, 2020, p. 987).

The Bundesvereinigung Kulturelle Kinder-und Jugendbildung (2017) mentions shared goals as a central condition for the success of cross-sector work, in addition to a common culture of collaboration and suitable framework conditions. Fischer and Hübner (2019) name possible goals for different educational groups, which are mostly based on the systems they are working in: While schools may want to develop into an attractive location, art and cultural institutions may want to reach more audiences, cultural education institutions may want to secure their extracurricular offers, and art and culture professionals tend to focus on opening up new fields of activity. These presumed goals have an influence on collaborative dynamics and may challenge collaboration as it often is initiated by elected officials whose goals and motivations ‘differ widely, they often have competing stakes in cultural planning’ (Markusen and Gadwa, 2010, p. 385). This may impede collaborative actions in this specific field of cultural education or open up areas of conflict.

Although literature describes that there are both common and different goals in cross sectoral collaboration (see this chapter), there is a research gap with empirical studies on goal diversity and group-specific goals in cross-sectoral collaboration, especially for the field of cultural education. The empirical studies available to date relate to a more detailed exploration of shared goals and their significance for cross-sector collaboration. For example, Kolleck et al. (2020) highlight the importance of goal agreement and analyzed that more influential actors in cross-sector networks were more likely than less influential actors to show high identification with shared goals. Another survey was conducted by AbouAssi et al. (2024) who found evidence that, in the perceptions of local government and non-profit leaders, goal alignment is linked to collaborations achieving their goals. Dusdal and Powell (2021) investigated the motivations of researchers partaking in international collaborative research and identified several different motivations such as career advancement or networking, but did not differentiate between disciplines or groups. Another study looked at the reasons for the engagement in cross-sector coalitions, e.g., identifying complementary or common goals, building trust among each other or perceiving that other actors have important resources (Koebele, 2019, 2020).

There is a lack of understanding why different groups within a specific field as cultural education networks engage in a cross-sector network and which specific goals apart from the commonly shared goal they want to achieve. Addressing this research gap will create a better understanding of the reasons of engagement and collaborative dynamics at the beginning of a collaboration. Furthermore, the results can help develop more tailored and effective strategies for cross-sectoral collaboration in cultural education networks, thereby maximizing their potential to enrich their communities.

This study aims to identify the group-specific goals that actors seek to achieve through participating in cross-sector collaborative networks in the field of cultural and arts education. We employed an exploratory research design to gather data in this understudied field. A total of 24 semi-structured interviews were conducted and audio-recorded, alongside the hierarchical mapping technique. After transcription, the interview data was analyzed using thematic analysis.

The interviews were conducted in four urban municipalities and two rural regions in Germany, each in a different federal state. Each municipality was studied in the context of a two-year consultancy process led by a mediating institution. The aim of this process was to build and strengthen cultural education collaborations and networks in order to address barriers to participation in cultural education and to promote participatory structures for disadvantaged children and youth at the local level. To this end, a team of actors from different sectors (administration, cultural education, coordination, schools, independent arts and culture scene) was formed in each of the six municipalities. Their collaborative efforts focused on fostering sustainable partnerships and incorporating diverse perspectives to develop cultural education opportunities tailored to the needs of local communities.

As researchers, our aim was to identify conducive conditions for fostering social relationships, collaboration and the formation of social networks. To gain deeper insights into collaboration and the emergent social networks, we conducted interviews with actors from all participating sectors (as outlined in the preceding sector). Our interviews focused on exploring perspectives, specifically targeting individuals actively engaged in the consultation process and most likely to facilitate emergent collaborations. Additionally, we employed purposive sampling (Flick, 2014, pp. 175–176), ensuring a maximum representation of cases. This involved selecting interviewees from various hierarchical levels across all sectors, while also including informal leaders and critical cases. Some of the interviewees were already more closely connected with other actors in the network at the time of the interview, while others had fewer contacts. What they all share is their involvement in cultural education within their working environment. Following the recruitment and interviewing of two or more actors from each sector, we reached a point of data saturation (Table 1).

In total, 24 interviews, ranging in duration from 27 to 78 min, were conducted between September and November 2018. Prior to this, three pretest interviews were conducted to refine the interview guide. The semi-standardized interview guide included four main questions, along with egocentric network maps adapted from Kahn and Antonucci (1980). These network maps were used to create a narrative-generating atmosphere. Semi-standardized interviews provide a structured framework allowing flexibility and openness to additional insights. The interviews were structured into five sections: description of institutional roles and tasks, perspectives on collaboration, visualization of social ties and network, goals and expectations related to the collaboration, and open topics. The first question aimed to stimulate narrative by asking about the interviewee’s role outside the collaborative network. Subsequent questions focused on network building, collaborative intentions, goals and expectations regarding participation in the collaborative process, allowing interviewees to share their personal stories. Narrative-generating questions and open-ended questions were used to support interviewees’ narratives. To gain more insight into network relationships, further questions were asked, for example ‘You have just mentioned person X. To what extent do you already know this person?’ or ‘You were just talking about idea X. What are your goals for this idea and for the collaboration as a whole?’

During the interviews, egocentric network maps were used to stimulate narration and help interviewees visualize their networks (Hollstein and Pfeffer, 2010). We used standardized-structured network maps that strike a balance between openness to enrich narratives and structure to elicit information relevant to the interview topic. The network maps were introduced when discussing social ties and visualizing the network using the hierarchical mapping technique (Hollstein and Pfeffer, 2010). Participants were tasked with placing their collaborative partners on the egocentric network map and explaining their choices. The main aim was not to map the entire network, but to gain deeper insights into social relationships, which are crucial for understanding social networks (Bernhard, 2018), and to visualize individual perspectives within the network. While using the network maps, interviewees frequently started talking about their relationships with the individuals they had positioned on the network map.

The data were analyzed using thematic qualitative content analysis, following Kuckartz (2014). This methodological approach aims at the development of a system of categories. Our analysis focused on this research method and the interview transcripts. Although the network maps were used primarily to gather additional information and complement the interviewees’ narratives, they were not directly used for the analysis presented in this article. Initially, the question about goals was explicitly asked during the interviews (‘What goals do you pursue with your participation in the collaboration?’). Subsequently, further insights into goals emerged during the interviews, prompting us to use the entire transcripts for a comprehensive analysis. Prior to coding, case summaries were written to condense the central characteristics of individual cases against the background of the research question (Kuckartz, 2014).

In order to address the research question regarding the identification of goals among actors from different sectors, the data were analyzed in two distinct phases. Initially, the main category ‘goals of the participating actors’ was developed and defined in a codebook and subsequently validated through consensual coding. The data was then systematically coded within the framework of the main category. First, the goals of the interviewees were analyzed without regard to group affiliation, focusing on the content and commonalities of the goals of all stakeholders. Then, four sub-categories were formed through inductive coding: target group-related goals, resource-related goals, competence-related goals and goals related to visibility and appreciation (Table 2).

Finally, the interview data coded under the main category were assigned to the respective subcategories. The second step of the analysis followed. Our aim here was to identify an overall goal for each of the groups involved. To do this, we created a qualitative cross tab, which Kuckartz (2014) describes in the last step of the thematic content analysis as simple and complex analyses and visualizations, and for which he offers different possibilities. We use the crosstab to show links between group characteristics and the coded thematic statements. The previously formed subcategories (Table 3, y-axis) were identified in each group (Table 3, x-axis). In a further step of interpretation and the last step of the analysis, these subcategories were condensed into an overall, group-specific goal for each group of actors (Table 3, last line).

Several interviewees talked about shared goals and their relationship with other actors. The following quote in particular stood out for us:

We all have the same goals, we are all idealists and everyone feels alone in their field, but when you do something together, you are not alone (B3_2).

This quote highlights that the interviewees perceive collaboration as a collective effort toward common goals, providing a sense of unity and support while reducing feelings of isolation. Collaboration is seen as a process with no considerations of differences in goals or tensions. The following sections explore these different goals in detail.

According to the interviewees of the administration group, the emerging network’s primary goal is to improve access to educational services for children and youth and to establish and secure sustainable structures:

[…] to develop ideas about what the young people here want. So, also to get input from their side, what is wanted here, what is needed here, to work something out (B1_3).

They emphasize considering the wishes and needs of the target group through direct input. Aligning services with the interests of children and young people aims to foster inclusion and engagement. Furthermore, interviewees express a collective motivation to optimize available cultural offerings by seeking financial support and sustainable funding:

And at the end of the day, of course, it’s also about money, and I’m not going to get any money if I’m here as a lone fighter shouting that we need money, but that will only crystallize if we say, ok, after this project we have these results, they have to be consolidated and we hope that the municipal budget will then also be geared to the needs (B3_2).

Engagement in the network stems from the collective need to advocate for resources and funding. By presenting tangible results, they aim to secure municipal funds for cultural education. Another interviewee highlights the goal of creating a dedicated cultural budget approved by politicians to ensure long-term funding without competition from other areas. The actors’ engagement is driven by a desire to use their professional skills to promote cultural education, prioritizing community benefits over personal benefits. Furthermore, they emphasize the importance of structural interfaces, shared responsibility, and collaborative decision-making rather than centralization:

[…] that everyone in the team does everything, that’s important, and not one person saying ok, now we’ll do this and everyone else will support it, but then one person is the one who “does everything,” organizes everything and in the end you do it together (B2_1).

Additionally, they aim to enhance interactions with actors from different sectors, particularly the cultural sector, and strategize “how to advance in these areas” (B4_4) for the greater good of cultural education. The ultimate goal of the administrative actors is to create a vibrant network with inclusive structures that integrate various youth and cultural initiatives and attract families, as illustrated by the following statement:

The goal is to create a community, a network, where the different places, where […] incredibly good youth work and cultural work is done […], to bring that together, to coordinate it and simply to create a structure (B1_3).

Participation of various institutions and stakeholders enriches cultural education and community integration. The interviewees aim to unify disparate efforts into a structured framework. By creating a community of practice, they envision a more collaborative approach that enhances the accessibility and quality of cultural education. In summary, the administration group’s primary goal is to optimize the cultural education network within their municipality.

The interviewees in the coordination group hope that children and youth will benefit from the network’s offerings. One interviewee articulates the wish for children to feel ownership and belonging in these spaces:

That the children conquer these places that we have prepared, that they have the feeling ‘this is my place and when I’m bored, I just go there and have a look’ (B4_1).

More generally, the cultural network should aim to serve children and youth, facilitating identity-forming experiences and encouraging regular visits. To achieve this goal, the coordination group seeks to unlock the potential of local cultural collaborations and enhance the profile of core cultural institutions, which often face funding challenges despite their significant role:

[…] that they are in a better financial position, because that also offers opportunities for collaboration, then you also know that you can ask them differently without always having to beg or have a guilty conscience, because they are in difficult economic circumstances anyway (B4_2).

Insufficient funding hampers the development of sustainable structures and impedes recognition of these actors as full members of the network by other stakeholders. This funding gap also means that not all needs of children and youth are met by programs:

But there should be more funding for the independent providers in this cultural scene, so that they can also consolidate a little, yes, because youth work does not reflect everything that concerns the leisure behavior of children and young people (B4_2).

This quote underscores the cultural scene’s importance for children’s and youth’s leisure activities and sense of belonging. Despite holding key resources, cultural actors’ involvement in networks is hindered by funding shortages. The interviewees from the coordination group stress this funding gap, which limits synergies with artists. They emphasize a desire for greater involvement of cultural education actors on equal terms. Their vision is a vibrant, cross-sector network fostering mutual support and resource sharing without hierarchies. One interviewee envisions a network where participants from different sectors can easily access support and expertise:

That would be my wish, that the participants from the different areas say: ‘We now have a functioning network. We have a structure. We know who we can turn to when we have open questions’. And that you support each other with the resources that each of you can bring to the team (B1_6).

Due to uneven financial support, the coordination group seeks to create structures and synergies. They aim to build a network where other actors can easily access each other’s expertise and resources, leading to optimized resource use and enhancing collaboration. This well-connected network, as they imagine it, is expected to improve efficiency, knowledge sharing, and endure beyond temporary projects. The promotion of such a structure is also connected to hopes for long-term financial support and collaboration.

And I think that such a network can also create a group or a community, which then lasts even longer (B1_5).

The interviewees envision lasting connections within the network that foster a sense of longevity beyond resource sharing. The overall goal of the actors is to create ‘synergies of resources’, harnessing collective cultural forces in the local community.

Interviewees from the cultural education group advocate for greater youth involvement in initiating and shaping cultural activities. They emphasize the importance of children and youth participation in decision-making processes to create genuine access through suitable collaboration methods:

What I hope for most of all is that we manage to work together in such a way that we close these gaps, so to speak, and yes, create a form of access that does justice to children and young people and really opens doors and not just, well, tries to (B4_5).

Their participation aims to fill gaps in the community’s cultural offerings, benefiting both the target group and providers. Clarifying responsibilities is essential to protect cultural work from being overtaken by other actors. One suggested solution is a coordination center, “if everyone supports it” (B2_2). Network members should be empowered to realize their ideas, share influence and pool resources to develop sustainable structures:

Specifically, I think it’s a pity that a lot is actually possible in the city, but that it’s often played off against each other or played off against each other due to a lack of knowledge, and that a network structure like this could actually be something that somehow manages to establish itself better in the long term, that increases recognition and somehow also opens up more perspectives for cultural actors, but also for educational and social actors, especially in the field of cultural education, because this network also has an outward effect and not just an inward effect, and that’s actually my goal (B1_2).

The interviewee envisions a long-term collaboration that raises awareness and expands opportunities for other actors in cultural education. Poor coordination of existing structures led to disagreements due to a lack of knowledge. Perspectives and knowledge in cultural education are seen as important, and the interviewees explicitly wish to share knowledge and develop their skills.

I want to work more with schools, that’s not my strength. My strength is the work with the children and the conceptual work. Everything in between takes a lot of energy and I want to optimize that. I feel like I’m putting too much into it, or maybe I have less breath than I usually have. That’s where I expect help and relief (B3_1).

The identified gap is in effectively working with schools, seen as crucial for reaching children. Assistance is sought in establishing sustainable, mutually beneficial relationships with educational institutions and streamlining their own work structures.

Additionally, on an interpersonal level, interviewees seek a supportive working atmosphere with colleagues:

Just to see sometimes, oh, you are not doing it all wrong, no, because if you actually get criticism like that and it says, well, it’s not all that important, maybe you can cancel it, then it’s good to have someone who says, firstly, we have the same problem, secondly, what you are doing is good, thirdly, it’s important (B4_3).

The goal is to create valued structures that influence decision-making processes. Greater recognition is linked to hopes for a lasting impact on the community’s cultural education landscape. The cultural education group aims to build sustainable structures and secure the future of cultural education by increasing visibility and recognition, especially among hesitant policymakers.

Emphasizing the importance of creating meaningful activities, members of the school group aim to provide space for such activities within their institutions:

[…] that the pupils at my school, including those who are socially disadvantaged, that they all have the opportunity to have a meaningful activity in the afternoon. Something that’s fun, that gets them off the streets or off their smartphones, that just keeps them engaged in a meaningful way and exposes them to things that they might not even experience at home (B2_3).

Their goal is to offer meaningful after-school activities that enrich pupils’ educational experiences and, in the long run, address social inequalities by fostering engagement. Members of the school group emphasize the need for minimal effort in terms of resources:

My expectations are that we will really build a professional structural network in which the work is shared. Given my personal situation and the other responsibilities I have in addition to running the school, I cannot afford to waste too many resources or take up too much time. But what is important has to be done and I would like to be involved, so my expectation is simply to participate, but that it is really feasible in terms of time (B2_3).

This highlights the group’s goal for a professional network with efficient responsibility allocation, acknowledging time constraints while emphasizing the importance of the network’s work. Another member, whose role depends on organizing afternoon activities in educational institutions, participates to secure funding for these activities, reflecting a role-related rather than personal goal. She suggests a fund managed by working group leaders and highlights the need for support in providing afternoon programs in all-day schools:

Because I also organize the all day school in the afternoon, I always need group leaders to offer something, and it’s good to know who I can turn to, who might know someone who has free capacity to work with us. It would also be great if you could just have a financial pot for it, somehow from the leaders of the working groups. Yes, and if such actions come out, like they offer something at school or we go somewhere with the school, then I think that’s also great (B3_5).

This underscores the need for a network of resources to support for organizing afternoon school activities. By fostering connections and leveraging capacities, members aim to provide diverse activities for pupils. Financial support is essential for the feasibility and sustainability of these afternoon programs. Another goal is to increase appreciation within their own working environment, as articulated by a member:

Of course, I would like to be a headmaster who is also accepted in his environment and is perceived as someone who is also committed and yes, of course you also want to be successful or simply appreciated (B2_3).

The quote reflects the school leader’s desire for acceptance, recognition, and appreciation to enhance his role and improve the reputation of his institution.

The interviewees stress that the network should not only care for achieving their own goals, but ‘to support each other and that we really build a professional structural network in which the work is distributed’ (B3_5).

Overall, the overarching goal of the school actors is to increase institutional and role attractiveness, optimizing resource use and time feasibility.

Artistic self-expression is at the heart of the interviewees’ engagement and work with children and youth:

My experience is that children who have been there and who I have met later and who tell me that they did this or that activity with me, it stays in their memory because the children are at the center, they really get to do something that they want to do and that also empowers them (B3_3).

Members aim to create a positive, empowering environment with lasting impressions and impactful experiences for children and youth by focusing on their interests and activities. They also seek to delegate tasks to reduce their workload or establish a coordination office to manage organizational and financial aspects, allowing them to focus on their “core business” (B3_3):

It would be wonderful if there was help, because I’m an actress and now a drama teacher, but I do not really have the capacity or the means for all this organizational financial stuff (B3_3).

Based on this excerpt, the interviewee recognizes her expertise as an actress and aims to maintain within the network. Seeking support in areas outside her field of expertise would allow her to concentrate effectively on her core responsibilities and strengths while remaining an active network member. Interviewees of this group rely on collaboration with others to enhance their own work within the network.

So, I really need to find network partners for my actual work. And yes, maybe venues will open up or project locations (B3_4).

By expanding her professional network and exploring new opportunities for partnerships, the interviewee aims to improve their work environment and create better working conditions. Additionally, they intend to leverage network contacts to advance tasks beyond their usual scope. In the following quote, the interviewee discusses a project he initiated that faced structural obstacles, preventing it from reaching the intended audience.

In this particular case, I would hope that there would be support at another time, so that I would know exactly, could you please try to push this issue somewhere here at the youth welfare office and at the youth center or at the social services, to provide funding for it or to make it easier for the teachers to organize it (B3_4).

The interviewees emphasize the importance of collaboration to create a sustainable and efficient work environment. They adopt a proactive and persistent attitude toward improving their working conditions, as highlighted in the following quote:

The big goal would be that we manage to send a list of demands at least to our ministry in [name of state], but even better to the federal ministry, that we finally change this funding policy. That there should be more long-term funding in addition to project funding (B3_4).

The interviewee aspires to secure long-term funding alongside project-based support, prioritizing financial stability for both the network and their own work environment. This stability is crucial for fostering lasting partnerships and sustainable project funding.

By nurturing personal relationships, the interviewees seek to minimize uncertainties in working dynamics, especially among the actors of municipal administration. One interviewee reflects:

What I knew before, what I realize again now, is that this / that it is good when you have already worked together […] this strangeness in the contact, that it is lifted a bit when you have worked together for two afternoons or mornings (B2_6).

While members prioritize their own working conditions and sometimes view themselves as “lone fighters” (B3_3), they also value reducing unfamiliarity. Building familiarity and comfort among colleagues is seen to foster communication, trust, and productivity within networks or collaborations. The overarching goal of the arts and culture group can be summarized as “improving their own working conditions.”

Our analysis reveals diverse motivations driving actors to participate in network development within cultural education. Each group’s goals can be categorized into distinct levels: macro, meso, and micro, providing a strategic framework to understand systemic differences in goal pursuit.

At the macro level, overarching goals such as “Optimizing the cultural education landscape” (administration group), “Synergies of resources” (coordination group) and “Building sustainable structures for cultural education” (cultural education group) focus on enhancing the entire cultural education system within the municipality. The administration group aims to refine the cultural network to improve access for children and youth, fostering sustainable structures and inclusivity through community engagement. Their goal is to consolidate various youth and cultural initiatives into a dynamic network that elevates the accessibility and quality of cultural education.

Similarly, the coordination group seeks to leverage resources effectively by supporting key cultural institutions facing financial challenges. They aspire to create identity-building experiences for young people within cultural spaces, nurturing a collaborative network that encourages mutual support and resource sharing.

The cultural education group targets macro-level goals by addressing gaps in cultural education provision, advocating for increased participation among youth, and elevating the profile of cultural education among policymakers. Their aim is to achieve lasting impact and recognition in municipal cultural policies.

Moving to the meso level, the school group focuses on “Increasing institutional and role attractiveness” by enhancing their school’s appeal through meaningful extracurricular activities. They prioritize providing engaging opportunities, especially for disadvantaged pupils, beyond traditional classroom settings. Seeking efficiency in resource management within a professional network, they emphasize the need for financial support and coordinated efforts to organize after-school activities. Their goal is to foster a supportive environment that enhances their institution’s reception and their own roles within it.

Conversely, the micro perspective is exemplified by the independent cultural actors’ goal of “Improving their own working conditions.” They emphasize resource sharing and task delegation to alleviate individual workloads, enabling them to focus on their artistic strengths. Seeking organizational and financial support, they aim to create impactful experiences for their audience through arts and expand their professional network. Their pursuit is characterized by a desire to strengthen their individual positions within the network while fostering collaborative partnerships.

By categorizing these goals into macro, meso, and micro levels, we provide a comprehensive understanding of how different groups within cultural education networks aim to impact the broader system, their respective organizations, and their own professional roles (see Figure 2).

The primary focus of our study was to explore the distinct goals pursued by actors from various organizations involved in cross-sector networks of cultural education. Understanding these goals is crucial as they provide initial insights into the nuanced significance of goal-setting in cross-sector collaboration within cultural education. Goals and their alignment are widely recognized as pivotal indicators of collaboration success (Vangen and Huxham, 2012; Weber et al., 2022).

Firstly, our analysis contributes to the extant literature on cross-sector collaboration literature by empirically examining the diverse goals that drive actors’ engagement in cultural education networks. Existing literature underscores the challenges inherent in collaborative efforts when goals are not clearly defined (Emerson et al., 2012, p. 17). Vangen and Huxham (2012) describe how goals within collaborative systems can be complex and multifaceted, calling them “tangled web,” ranging from individual and organizational aspirations to broader collaborative aims, which may evolve over time. They argue that while diversity in goals can pose challenges, it also brings unique benefits to collaborations (p. 37). Bryson et al. (2015) emphasize the management of tensions arising from the coexistence of unified and diverse goals as essential for effective collaboration (p. 654). Our study affirms this duality, highlighting both the congruence and diversity of goals across different groups engaged in cultural education networks.

Aligned with Vangen and Huxham’s (2012) framework, which categorizes goals into system levels – collaboration, organzation(s), and individual(s) – our findings demonstrate that goals within cultural education networks operate at multiple levels. For instance, goals such as “Optimizing the cultural education landscape” (administration group), “Synergies of resources” (coordination group) and “Establishing sustainable structures for cultural education” (cultural education group) are indicative of macro-level goals focused on enhancing the overall cultural education ecosystem. These collaborative goals represent shared aspirations that leverage collective efforts to achieve outcomes that individual actors cannot accomplish alone (Bryson et al., 2016, p. 912).

In contrast, organizational goals, exemplified by the “Increasing institutional & role attractiveness” pursued by the school group, emphasize enhancing the institution’s appeal through effective collaboration. These goals reflect aspirations that benefit the organization itself within the collaborative network (Vangen and Huxham, 2012).

At the individual level, goals such as “Improving their own working conditions” identified among independent arts and cultural actors highlight personal aspirations within the network. These goals underscore the importance of creating supportive environments that enable individuals to focus on their core strengths and professional development within the collaborative framework.

Our second contribution underlines the critical role of goal congruence and diversity in sustaining long-term collaborative networks in cultural education. Existing literature suggests that goal diversity is pervasive even in straightforward collaborative settings (Vangen and Huxham, 2012, p. 754). While our study reveals some degree of goal congruence, particularly around overarching collaborative goals like expanding access to cultural education for disadvantaged youth, it also highlights diverse goals across the five participating groups. Das and Teng (2000) conceptualize this tension as a “framework of conflicting forces” (p. 85), emphasizing the dynamic interplay of goals and their implications for collaborative dynamics. In managing these tensions, effective collaborative governance becomes crucial, aligning operational structures and decision-making processes with shared goals (Weber et al., 2022).

Thirdly, our study contributes to understanding the nexus between collaborative goals and governance structures. When goals are perceived as congruent, governance structures tend to align accordingly (Weber et al., 2022). Conversely, diverse goals necessitate flexible governance frameworks capable of accommodating varying interests and priorities (Saz-Carranza and Ospina, 2011). Our findings suggest that while there is alignment around core collaborative goals, there exists diversity in goals across system levels and content dimensions within cultural education networks. This tension stresses the need for adaptive governance strategies that foster cohesion while respecting diversity among stakeholders.

In summary, our study identifies group-specific goals within cross-sector networks involved in cultural education. However, our findings represent only a snapshot of goal diversity in this context, requiring further empirical exploration. Future research could explore whether similar patterns emerge in different contexts and over time, using longitudinal designs to track goal evolution and participation dynamics. Additionally, examining the influence of framework conditions such as organizational structures and power dynamics could provide a more comprehensive understanding of group-specific goals in cross-sector collaborations.

According to Taherdoost (2022), qualitative research offers valuable insights for theory-building and understanding social phenomena, complementing quantitative approaches by uncovering new perspectives and generating hypotheses.

Our findings reveal a spectrum of goals among stakeholders engaged in cultural networks, ranging from shared goals to distinct ambitions at macro, meso, and micro levels of collaboration. This nuanced understanding underscores the critical need to navigate these levels effectively in cross-sector partnerships.

The study highlights two crucial insights: firstly, the peril of discordant goals jeopardizing the success of cross-sector collaborations in cultural education. Secondly, it emphasizes the necessity for transparent goal-setting from the outset and the integration of diverse perspectives to sustain voluntary commitment among participants.

Out-of-school cultural education depends heavily on sustained engagement, making proactive communication and goal alignment crucial for long-term collaboration. Stakeholders should establish frameworks at the outset to align shared and individual goals, ensuring clarity for all parties. Regular reviews can help teams assess progress and make adjustments, while training in skills like conflict resolution and effective communication can support the management of diverse goals and strengthen networks. This study, focused on six German municipalities, may have limited applicability to other contexts and primarily reflects the views of active participants, overlooking less engaged voices. Future research should include broader perspectives and long-term analyses to better support sustainable cultural education networks.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because individuals could be identified through the datasets as the cohorts per interviewed community are small. Anonymity was guaranteed to the participants. The publication of the accumulated results does not compromise the anonymity of the participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWFyaWUtdGhlcmVzZS5hcm5vbGRAZnUtYmVybGluLmRl.

Ethical approval was not required in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

M-TA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NK: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number NETKUB. Support for publication was provided by the Open Access Publication Fund of Freie Universität Berlin.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbouAssi, K., Prince, W., and Johnston, J. M. (2024). A recipe for success? The importance of perceptions of goal agreement in cross-sector collaboration. Public Adm. 102, 370–387. doi: 10.1111/padm.12925

Acero, A., Ramirez-Cajiao, M. C., and Baillie, C. (2024). Understanding community engagement from practice: a phenomenographic approach to engineering projects. Front. Educ. 9:732. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1386729

Amabile, T. M., Patterson, C., Mueller, J., Wojcik, T., Odomirok, P. W., Marsh, M., et al. (2001). Academic-practitioner collaboration in management research: a case of cross-profession collaboration. Acad. Manag. J. 44, 418–431. doi: 10.2307/3069464

Ansell, C., and Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 18, 543–571. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mum032

Babiak, K., and Thibault, L. (2009). Challenges in multiple cross-sector partnerships. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 38, 117–143. doi: 10.1177/0899764008316054

Baraldi, E., and Strömsten, T. (2009). Controlling and combining resources in networks — from Uppsala to Stanford, and back again: the case of a biotech innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 38, 541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.11.010

Bardach, E. (2001). Developmental dynamics: interagency collaboration as an emergent phenomenon. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 11, 149–164. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003497

Bernhard, S. (2018). Analyzing meaning-making in network ties—a qualitative approach. Int. J. Qual. Methods 17:160940691878710. doi: 10.1177/16094069187871

BMBF (2021) Förderrichtlinie (2018–2022) [Funding guideline (2018-2022)]. Available at: (https://www.buendnisse-fuer-bildung.de/buendnissefuerbildung/de/programm/foerderrichtlinie-2018-2022/foerderrichtlinie-2018-2022).

Bronstein, L. R. (2003). A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc. Work 48, 297–306. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.3.297

Bryson, J. M., Ackermann, F., and Eden, C. (2016). Discovering collaborative advantage: the contributions of goal categories and visual strategy mapping. Public Adm. Rev. 76, 912–925. doi: 10.1111/puar.12608

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., and Stone, M. M. (2015). Designing and implementing cross-sector collaborations: needed and challenging. Public Adm. Rev. 75, 647–663. doi: 10.1111/puar.12432

Büdel, M., and Kolleck, N. (2023). 'Rahmenbedingungen und Herausforderungen kultureller Bildung in ländlichen Räumen – ein systematischer Literaturüberblick' ['Framework conditions and challenges of cultural education in rural areas - a systematic literature review']. Z. Erzieh. 26, 779–811. doi: 10.1007/s11618-023-01144-0

Bundesvereinigung Kulturelle Kinder-und Jugendbildung (2017) Qualitätsdimensionen für Kooperationen von Kultur und Schule: Gemeinsam kulturelle Bildungs-und Teilhabechancen verbessern [Quality dimensions for cooperation between culture and schools: improving opportunities for cultural education and participation together]. Available at: (https://www.bkj.de/digital/wissensbasis/beitrag/qualitaetsdimensionen-fuer-kooperationen-von-kultur-und-schule/).

Castañer, X., and Oliveira, N. (2020). Collaboration, coordination, and cooperation among organizations: establishing the distinctive meanings of these terms through a systematic literature review. J. Manag. 46, 965–1001. doi: 10.1177/0149206320901565

Clarke, N. (2018, 2018). Relational leadership: theory, practice and development. New York: Routledge.

Corsaro, D., Cantù, C., and Tunisini, A. (2012). Actors' Heterogeneity in Innovation Networks. Indust. Market. Manag. 41, 780–789. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.06.005

Das, T. K., and Teng, B.-S. (1998). Between trust and control: developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 491–512. doi: 10.2307/259291

Das, T. K., and Teng, B.-S. (2000). Instabilities of strategic alliances: an internal tensions perspective. Organ. Sci. 11, 77–101. doi: 10.1287/orsc.11.1.77.12570

Dumitru, D. (2019). Creating meaning. The importance of arts, humanities and culture for critical thinking development. Stud. High. Educ. 44, 870–879. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1586345

Dusdal, J., and Powell, J. J. W. (2021). Benefits, motivations, and challenges of international collaborative research: a sociology of science case study. Sci. Public Policy 48, 235–245. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scab010

Eaton, W. M., Brasier, K. J., Burbach, M. E., Whitmer, W., Engle, E. W., Burnham, M., et al. (2021). A conceptual framework for social, behavioral, and environmental change through stakeholder engagement in water resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 34, 1111–1132. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2021.1936717

Elliot, A. J., and Fryer, J. W. (2008). “The goal construct in psychology” in Handbook of motivation science. eds. J. Y. Shah and W. L. Gardner (New York: Guilford Publications), 235–250.

Emerson, K., and Nabatchi, T. (2015). Collaborative governance regimes. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., and Balogh, S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Public Adm. Rev. 22, 1–29. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur011

European Commission. (2021) Culture and Creativity—Previous Programmes. Available at: (https://culture.ec.europa.eu/resources/creative-europe-previous-programmes).

Fischer, B., and Hübner, K. (2019) Kulturelle Bildungskooperationen: Freiräume für kinder und Jugendliche im Fokus [Cultural education cooperation: Focus on open spaces for children and young people]. Available at: https://www.kubi-online.de/ (Accessed July 31, 2024).

Fobel, L. (2022). 'Non-formal cultural infrastructure in peripheral regions: responsibility, resources, and regional Disparities'. Urban Plan. 7:5675. doi: 10.17645/up.v7i4.5675

Fobel, L., and Kolleck, N. (2021). Cultural education: panacea or amplifier of existing inequalities in political engagement? Soc. Incl. 9, 324–336. doi: 10.17645/si.v9i3.4317

Futrell, R. (2003). Technical Adversarialism and Participatory Collaboration in the US Chemical Weapons Disposal Program. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 28, 451–482. doi: 10.1177/0162243903252762

Gigerl, M., Sanahuja-Gavaldà, J. M., Petrinska-Labudovikj, R., Moron-Velasco, M., Rojas-Pernia, S., and Tragatschnig, U. (2022). Collaboration between schools and museums for inclusive cultural education: findings from the INARTdis-project. Front. Educ. 7:53. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.979260

Gugu, S., and Dal Molin, M. (2016). Collaborative local cultural governance. Adm. Soc. 48, 237–262. doi: 10.1177/0095399715581037

Harris, M., and Albury, D. (2009). The innovation imperative: why radical innovation is needed to reinvent public services for the recession and beyond. London: NESTA.

Head, B. W. (2008). Assessing network-based collaborations. Public Manag. Rev. 10, 733–749. doi: 10.1080/14719030802423087

Hollstein, B., and Pfeffer, J. (2010) Netzwerkkarten als Instrument zur Erhebung egozentrierter Netzwerke. Available at: (www.pfeffer.at/egonet/Hollstein%20Pfeffer.pdf).

Huxham, C., and Vangen, S. (2000). Leadership in the shaping and implementation of collaboration agendas: how things happen in a (not quite) joined-up world. Acad. Manag. J. 43, 1159–1175. doi: 10.2307/1556343

Huynh, T. H. P., Bui, T. Q., and Nguyen, P. N. D. (2023). How to foster the commitment level of managers? Exploring the role of moderators on the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: a study of educational managers in Vietnam. Front. Educ. 8:185. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1140587

Jessop, S. (2017). Adorno: cultural education and resistance. Stud. Philos. Educ. 36, 409–423. doi: 10.1007/s11217-016-9531-6

Kahn, R. L., and Antonucci, T. C. (1980). “Convoys over the life course: attachment, roles, and social support” in Life-span development and behavior. eds. P. B. Baltes and O. G. Brim (New York, N.Y: Academic Press), 253–286.

Katzenbach, J. R., and Smith, D. K. (1996). Teams: Der Schlüssel zur Hochleistungsorganisation [Teams: The key to high-performance organisation]. Wien: Ueberreuter.

Kleinbeck, U., and Kleinbeck, T. (2009). Arbeitsmotivation: Konzepte und Fördermaßnahmen [Work motivation: concepts and support measures]. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Koebele, E. A. (2019). Integrating collaborative governance theory with the advocacy coalition framework. J. Publ. Policy 39, 35–64. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X18000041

Koebele, E. A. (2020). Cross-coalition coordination in collaborative environmental governance processes. Policy Stud. J. 48, 727–753. doi: 10.1111/psj.12306

Kolleck, N. (2019). Motivational aspects of teacher collaboration. Front. Educ. 4:85. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00122

Kolleck, N., Rieck, A., and Yemini, M. (2020). Goals aligned: predictors of common goal identification in educational cross-sectoral collaboration initiatives. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 48, 916–934. doi: 10.1177/1741143219846906

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative text analysis: a guide to methods, practice & using software. London: Sage Publications.

Le, T. H. T., and Kolleck, N. (2022a). You know them all’—trust, cooperation, and cultural volunteering in Rural Areas in Germany. Societies 12:180. doi: 10.3390/soc12060180

Le, T. H. T., and Kolleck, N. (2022b). The power of places in building cultural and arts education networks and cooperation in rural areas. Soc. Incl. 10, 284–294. doi: 10.17645/si.v10i3.5299

Le, H., Polonsky, M., and Arambewela, R. (2015). Social inclusion through cultural engagement among ethnic communities. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 24, 375–400. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2014.911714

Liebau, E. (2018). “'Kulturelle und Ästhetische Bildung' ['Cultural and aesthetic education']” in Handbuch Bildungsforschung. eds. R. Tippelt and B. Schmidt-Hertha (Wiesbaden: Springer), 1219–1239.

Mannix, E., and Neale, M. A. (2005). What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 6, 31–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2005.00022.x

Markusen, A., and Gadwa, A. (2010). Arts and culture in urban or regional planning: a review and research agenda. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 29, 379–391. doi: 10.1177/0739456X09354380

Meads, G., Ashcroft, J., Barr, H., Scott, R., and Wild, A. (2005). Case for interprofessional education in health and social care. Oxford: Blackwell.

Moirano, R., Sánchez, M. A., and Štěpánek, L. (2020). Creative interdisciplinary collaboration: a systematic literature review. Think. Skills Creat. 35:100626. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2019.100626

Neelands, J., Belfiore, E., Firth, C., Hart, N., Perrin, L., Brock, S., et al. (2015). Enriching Britain: culture, creativity and growth. Coventry: University of Warwick.

Pearce, C. L., and Conger, J. A. (2002). “All those years ago: the historical underpinnings of shard leader-ship” in Shared leadership: reframing the hows and whys of leadership. ed. C. L. Pearce (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 1–18.

Picot, A., Reichwald, R., Wigand, R. T., Möslein, K., Neuburger, R., and Neyer, A.-K. (2023). The boundaryless enterprise: information, organization & leadership. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

Reed, M. S., Vella, S., Challies, E., de Vente, J., Frewer, L., Hohenwallner-Ries, D., et al. (2018). A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? Restor. Ecol. 26:216. doi: 10.1111/rec.12541

Saint-Onge, H., and Armstrong, C. A. (2004). The conductive organization: building beyond sustainability. Boston: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Saz-Carranza, A., and Ospina, S. M. (2011). The behavioral dimension of governing interorganizational goal-directed networks-managing the unity-diversity tension. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 21, 327–365. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muq050

Schöttle, A., and Tillmann, P. A. (2018) Explaining the benefits of team goals to support collaboration. In 26th Annual Conference of the International. Group for Lean Construction, Chennai, India: IGLC.

Sousa, I., and Ferreira, E. (2024). Students’ participation in democratic school management: a systematic literature review. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 23:333. doi: 10.11576/jsse-6333

Straub, R. P., and Ehmke, T. (2021). A person-centered approach for analyzing multidimensional integration in collaboration between educational researchers and practitioners. Front. Educ. 6:69. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.492608

Taherdoost, H. (2022). What are different research approaches? Comprehensive review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research, their applications, types, and limitations. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Res. 5, 53–63. doi: 10.30564/jmser.v5i1.4538

Vangen, S., and Huxham, C. (2012). The tangled web: unraveling the principle of common goals in collaborations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 22, 731–760. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur065

Weber, C., Haugh, H., Göbel, M., and Leonardy, H. (2022). Pathways to lasting cross-sector social collaboration: a configurational study. J. Bus. Ethics 177, 613–639. doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04714-y

Williamson, O. E. (1993). Transaction cost economics and organization theory. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2, 107–156. doi: 10.1093/icc/2.2.107

Winkler, I. (2006). Network governance between individual and collective goals: qualitative evidence from six networks. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 12, 119–134. doi: 10.1177/107179190601200308

Winner, E., Goldstein, T. R., and Vincent-Lancrin, S. (2013). Art for art’s sake? The impact of arts education. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Keywords: cross-sector collaboration, collaborative governance, goals, goal diversity, cultural education

Citation: Arnold M-T and Kolleck N (2025) ‘We all have the same goals’? Goal diversity in cross-sector collaborations of cultural education. Front. Educ. 10:1478472. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1478472

Received: 09 August 2024; Accepted: 08 January 2025;

Published: 24 January 2025.

Edited by:

Lucia Herrera, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Paulo Vaz De Carvalho, Catholic University of Portugal, PortugalCopyright © 2025 Arnold and Kolleck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marie-Therese Arnold, bWFyaWUtdGhlcmVzZS5hcm5vbGRAZnUtYmVybGluLmRl

†ORCID: Marie-Therese Arnold, orcid.org/0000-0002-8264-3880

Nina Kolleck, orcid.org/0000-0002-5499-8617

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.