95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Educ. , 02 April 2025

Sec. STEM Education

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1469889

Although diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) interventions in science, engineering, and higher education are often discussed as being led at the individual or institutional level, departments can be an effective academic entity for creating meaningful culture change. One way a department can embark on this work is through strategic planning, which can help a diverse group of stakeholders come together to identify a set of goals and pathways for achieving those goals over a sustained amount of time. In this piece, we present an overview of the University of Michigan Department of Mechanical Engineering’s three-phase DEI strategic planning process, which involved proposing strategic planning, creating the strategic plan, and preparing for implementation of the plan. Guiding questions and lessons learned from this process are provided to help other departments create their own locally relevant strategic plans in DEI.

Institutions of higher education in the United States (U.S.) have sought to address issues of campus diversity and climate for decades (Hart and Fellabaum, 2008; Leake and Stodden, 2014; Patton et al., 2019), including during tumultuous times (Holcombe et al., 2023; Malcom, 2024). However, marginalized groups—including people of color; disabled communities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) communities; and women—continue to be underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) (Freeman, 2021; National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2023). Even when “in the room,” marginalized groups in STEM too often report experiences of harassment, stereotyping, pressure to code-switch, and inequitable career outcomes (Braun et al., 2018; Brown and Morton, 2023; Cech, 2022; Cech and Rothwell, 2018; Leaper and Starr, 2019; Miller et al., 2021; Spencer et al., 2022).

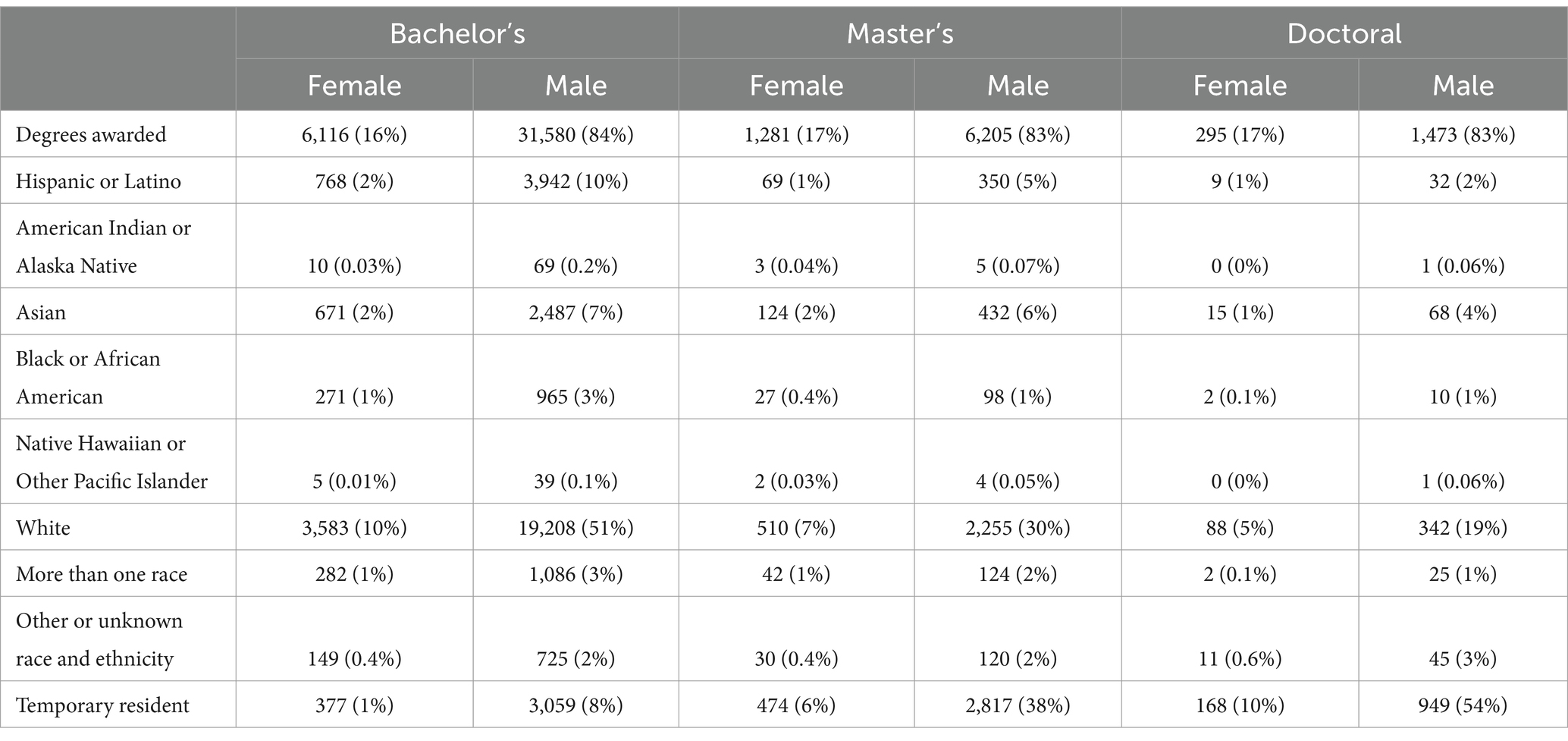

The discipline of mechanical engineering is no exception to these patterns. In 2020, only 16% of mechanical engineering bachelor’s degrees, 7% of master’s degrees, and 3% of doctoral degrees in the U.S. were awarded to Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander students (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2023)—even though these communities make up about a third of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Furthermore, less than 8% of doctoral degrees were awarded to disabled mechanical engineers when, by some estimates, 27% of adults in the U.S. have a disability (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). And for some groups (e.g., LGBTQIA+ and Middle Eastern and North African communities), questions about representation can be challenging to answer because institutional decisions about what data (not) to collect can render these communities invisible (see Chen et al., 2022; Langin, 2024).

Academic departments have the potential to be impactful sites for breaking patterns of inequity and exclusion in STEM. Departments are where students, faculty, postdocs, and staff learn “what kinds of social behaviors are encouraged, discouraged, tolerated, and not tolerated in classrooms, laboratories, and other social spaces” (Ong et al., 2018, p. 233). Changes to a department’s policies and procedures thus have the potential to create measurable and meaningful culture change. For example, department-level diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) work at the University of California Berkeley’s Department of Chemistry resulted in graduate students and postdocs feeling more valued and included after two years (Stachl et al., 2021). In contrast to institutions, departments typically have more flexibility in designing interventions that attend to their communities’ local histories, needs, interests, and heterogeneities (Armanios et al., 2021; Fisher and Henderson, 2018). A department can also scale an individual intervention across courses and research groups, and call attention to discipline-specific issues (e.g., the physical inaccessibility of machine shops; see Jeannis et al., 2020). Importantly, department-level work can lead to models of change that other departments within and outside of an institution can adopt (Chaudhary and Berhe, 2020; Cronin et al., 2021).

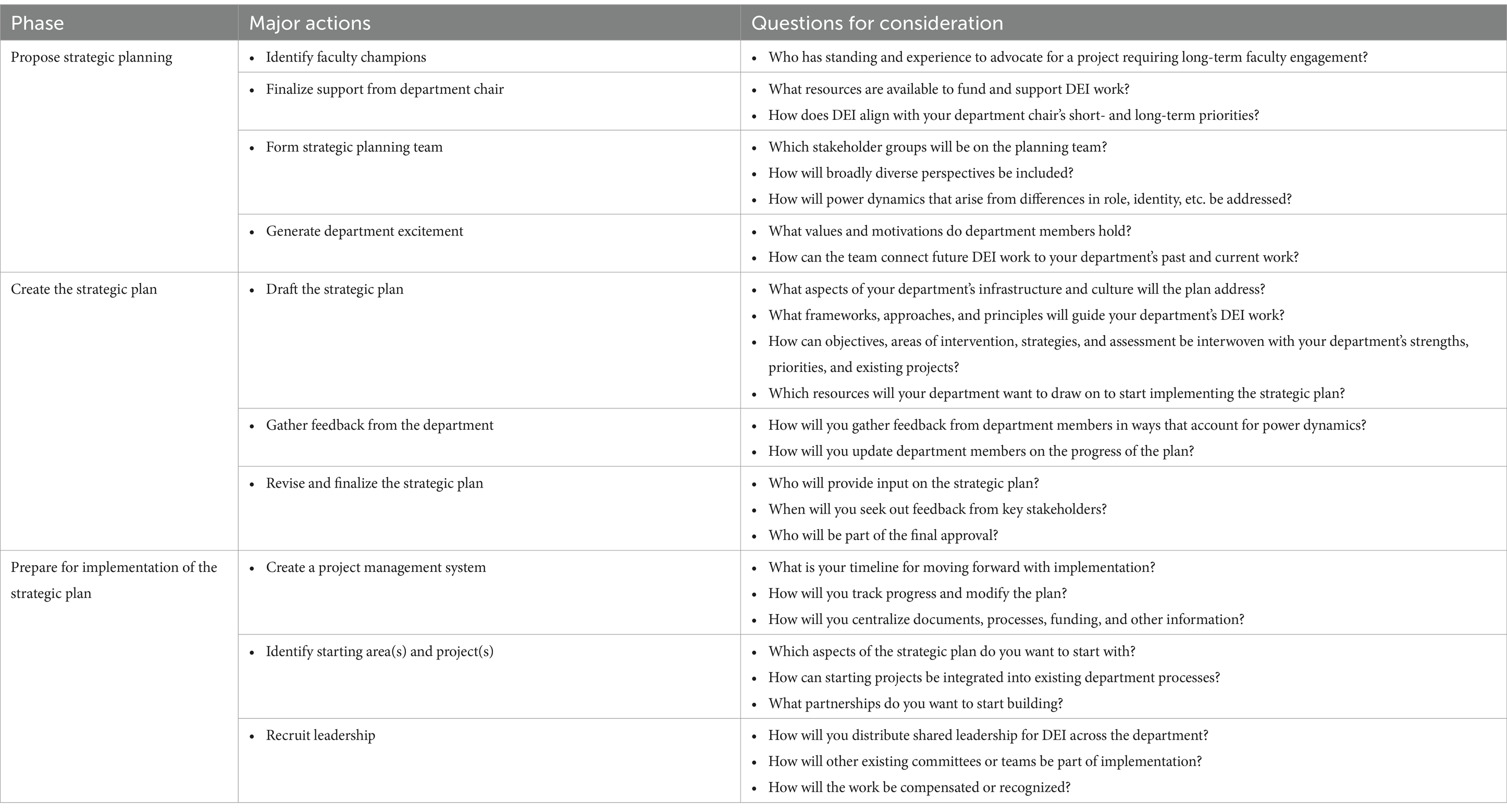

However, it can be daunting for a department to begin designing a set of DEI interventions that work together to create larger-scale change. In this piece, we describe how strategic planning can be an effective tool for helping a department accomplish such work. We describe three major phases of department-level strategic planning (Table 1) using the University of Michigan (U-M) Department of Mechanical Engineering (ME) as an example. Finally, we end with lessons learned about creating a sustainable and resilient infrastructure for department-level culture change.

Table 1. Phases of department-level strategic planning for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), including major actions and questions to consider during each phase.

This piece is written by three members of the U-M ME DEI strategic planning team. Susan joined the department as staff when the DEI strategic plan was being finalized. She comes to this work as a straight, cis, Asian American woman; settler; and 1.5 generation immigrant to the U.S. While a Ph.D. student and postdoc in ecosystem ecology, Susan’s research focused on identifying how different components of forest ecosystems interact to influence Earth’s climate. She uses a similar systems approach to examine how components of social systems interact to shape department climate in STEM disciplines like engineering. Susan’s socialization into the scientific community at primarily white institutions has contributed to her awareness of how someone’s background can be privileged in some contexts while rendered invisible in others. Alondra graduated with a Ph.D. from U-M ME in 2024. While a Ph.D. student, she reviewed the first draft of the department’s DEI strategic plan and moderated graduate student town halls to gather feedback for the plan. Alondra identifies as a Hispanic woman with disabilities. She recognizes the opportunities and privilege that come with pursuing an engineering degree at a research-intensive university in the U.S.—but has also experienced firsthand how educational spaces and engineering courses have not been built with all communities in mind. Alondra aims to combine her technical skills with an intersectional lens to create inclusive solutions to everyday engineering problems. Karl is a Professor in U-M ME who is a straight, cis, non-disabled white man. Karl was the founding chair of the department’s DEI Committee in 2016 and worked on the department’s DEI strategic plan since its inception. He was motivated to work on DEI issues by the need to address structural causes of non-inclusive and inequitable practices prevalent in STEM and academia in general. He realized that even though U-M and its College of Engineering proposed their own DEI strategic plans, the work to make long-term systemic change must also be done at the department level. As a group, we believe creating a supportive culture in mechanical engineering requires academic leaders to design structural changes that account for how DEI functions complexly, dynamically, and in ways that are context-sensitive and context-specific.

U-M ME’s strategic plan in DEI serves one of the largest departments at the university’s College of Engineering, with approximately 700 undergraduate students, 300 doctoral students, 275 master’s students, 80 faculty, 60 staff, and 60 postdocs. Consistent with national patterns in mechanical engineering (Table 2), several demographic groups are underrepresented in U-M ME. In 2023, 25% of bachelor’s degrees, 23% of master’s degrees, and 31% of doctoral degrees were earned by students who identified as female (College of Engineering, University of Michigan, 2023). Black, Hispanic, Hawaiian, or Native American domestic students comprised 12% of bachelor’s degrees, 10% of master’s degrees, and 25% of doctoral degrees (College of Engineering, University of Michigan, 2023).

Table 2. Mechanical engineering degrees awarded in the United States in 2020 as reported by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf23315/report).

The department’s strategic plan in DEI sits within a larger ecology of DEI work at U-M, which includes a university-wide DEI strategic plan (DEI 1.0) that launched in 2016 (U-M ODEI, 2024a). DEI 1.0 was comprised of 50 strategic plans—one for each school, college, or unit at the university. U-M’s DEI initiatives at the university, college, and department levels also operate within a larger legal and legislative landscape, including the state of Michigan’s adoption of Proposal 2 in 2006, which “restricted the use of race- and gender-conscious approaches in admissions, hiring, and other functions in public institutions” (U-M ODEI, 2024b). The College of Engineering’s DEI 1.0 included objectives that the department shared, such as expanding recruitment and retention of a broadly diverse student body (Michigan Engineering Office of Culture, Community and Equity, 2024)—but the plan’s recommendations were typically described at the college-level, leaving individual departments to determine how to work toward DEI 1.0 goals.

In response, a Staff/Faculty DEI Committee and a Student DEI Committee (now known as the ME DEI Alliance, an outgrowth of a student organization called the Mechanical Engineering Graduate Council), were formed. Both committees identified that department DEI activities seemed to be too narrowly focused, occur intermittently, or burden and involve the same subset of people. The diffuse nature of this work created barriers not only for connecting DEI efforts within the department, but also for connecting department efforts with those in the College of Engineering’s DEI 1.0. To address this challenge, both DEI committees proposed that the department create a strategic plan that could serve as a touchstone for future DEI work in the department.

U-M ME’s strategic planning in DEI occurred between 2020 and 2023. During this time, the COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matters protests raised awareness around social inequity and injustice (Fries-Britt et al., 2024), contributing to the department’s sense of urgency for developing a strategic plan in DEI. The finalization of the DEI strategic plan—including generating community support and outlining the DEI plan’s goals and mission—was completed as the department began its broader strategic planning process. DEI was included both as its own focus area in the department’s broader strategic plan, as well as in the other focus areas of the strategic plan: research, education, communication, and organizational structure. This integration of DEI throughout a department’s goals and practices is a critical component for building a more sustainable and resilient foundation that can sustain long-term DEI work.

By making norms, assumptions, values, and visions explicit, strategic plans can help academic leaders integrate DEI throughout their organization (Kezar et al., 2008). Our DEI strategic planning activities fell into three major phases: proposing strategic planning, designing the strategic plan, and preparing for implementation of the strategic plan. Major actions and attendant driving questions associated with each phase are highlighted in Table 1.

U-M ME’s strategic planning began by proposing a department-level strategic plan in DEI and gathering department support to build enough momentum for sustaining long-term DEI work, particularly from faculty. During this phase, we focused on the following (Table 1):

• Identifying faculty champions to advocate for and/or lead the strategic planning process;

• Working with the department chair to allocate resources for strategic planning;

• Forming a team to design the strategic plan; and

• Generating excitement across the department’s faculty.

Our faculty champion previously held department DEI leadership roles and approached the department chair with the DEI committees’ idea for creating a strategic plan. This proposal included requests for funding and the chair’s commitment to support structural interventions in the department. These requests were important to make early on in the strategic planning process, so that the changes posed in the plan could be sustainable (Buchanan et al., 2005). After receiving the chair’s approval for this work, the faculty champion formed a strategic planning team consisting of members from the Staff/Faculty and Student DEI Committees.

To begin generating faculty support and garner feedback, the faculty champion presented the proposal for a department strategic plan in DEI during a faculty meeting. The presentation described how implementing a plan could be feasible and why DEI was integral to our department and discipline. The case was presented that attending to DEI in engineering is needed for multiple overlapping reasons: (1) diversity is increasingly important for the future of the STEM workforce, as funding agencies acknowledge (e.g., National Science Board, 2020); (2) inequity in engineering processes harms marginalized communities (Waight et al., 2022) and a focus on diversity can uncover flaws in engineering design, as exemplified by the racially discriminatory pulse oximeter (Sjoding et al., 2020); and (3) exclusion remains an issue that students expect leadership to address, particularly given ongoing anti-Black racism (Holly and Comedy, 2022). While diverse teams can create better products—including more socially just ones—equity and inclusion are engineering values in their own right. If treating everyone with dignity and respect is part of a department’s core values, then DEI needs to be explicitly included in the department’s curriculum, practices, and administrative structures (Ormand et al., 2022). These arguments highlighted how our department could be more intentional about putting our principles into practice, and our faculty voted to move forward with creating a DEI strategic plan. Different arguments may resonate more for other departments, and we have found that staying attuned to your community’s interests, motivations, goals, and needs helps maintain continued support for DEI work.

Creating a DEI strategic plan involves not only developing a mission statement and actionable goals to serve that mission, but also building a department culture where different stakeholder groups are empowered to provide input and can share leadership in designing and implementing the strategic plan (Kezar, 2023). U-M ME’s work during this phase involved (Table 1):

• Drafting the strategic plan based on assembled information, such as other DEI plans, campus resources, and department data;

• Gathering department feedback through a transparent and inclusive process; and

• Revising and finalizing the strategic plan based on department input.

To have open, effective, and collaborative writing across faculty, staff, and students on the DEI strategic planning committee, it was important to create a space where everyone—especially students—felt able to safely and meaningfully contribute. The student DEI Committee’s two-year history of independence (with only advisory support from the faculty DEI committee chair during that period), helped provide students on the planning committee with confidence that their recommendations would be taken seriously.

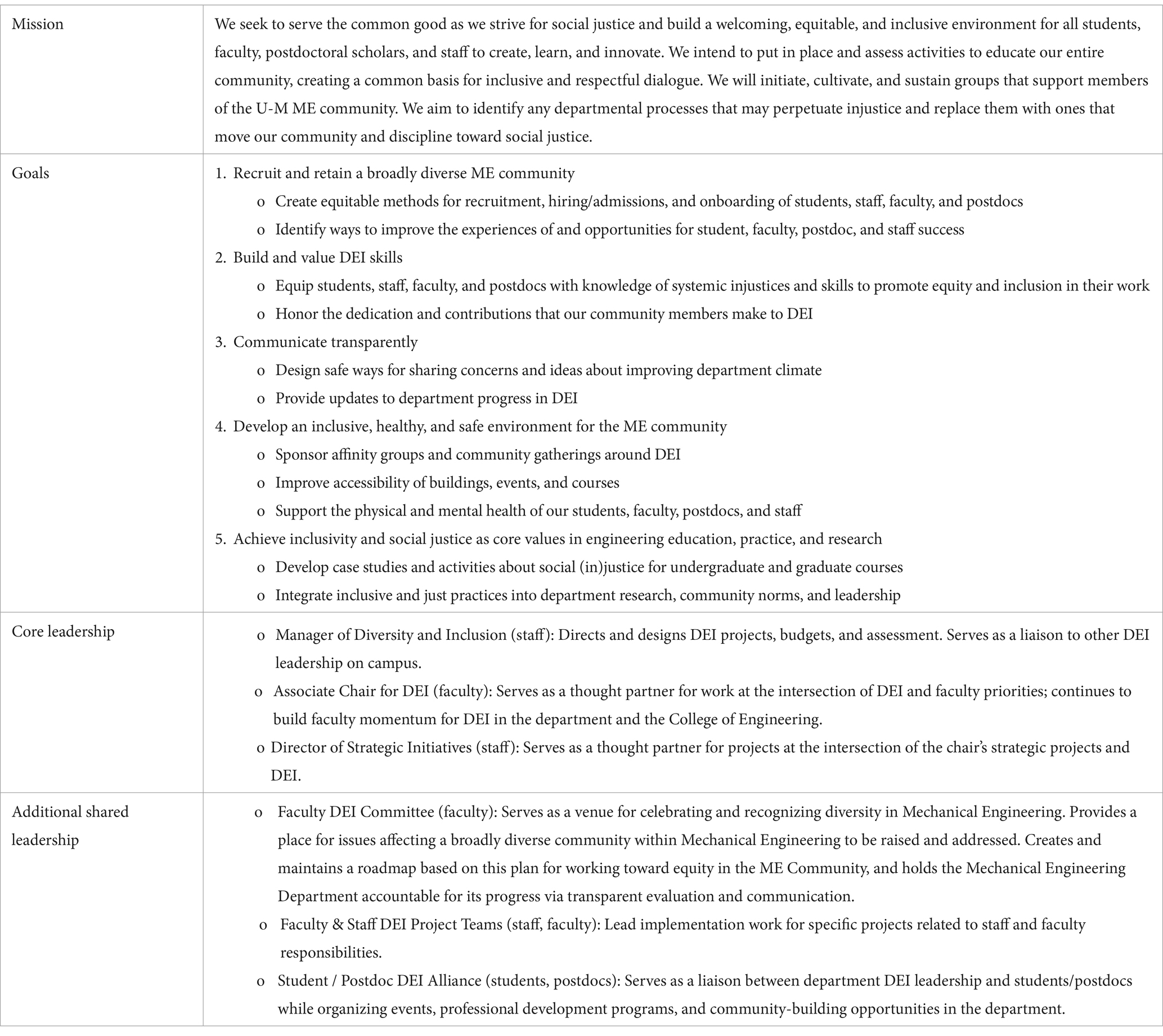

To write the strategic plan, the DEI strategic planning committee first examined other DEI strategic plans at U-M, including the College of Engineering’s DEI 1.0 (Michigan Engineering Office of Culture, Community and Equity, 2024) and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering’s DEI Committee Roadmap (Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Michigan, 2021). The committee also analyzed existing data from U-M climate surveys and about department demographics to learn more about U-M ME’s local context and DEI-related issues. Cataloging existing university resources that supported DEI efforts was also important for helping the committee develop attainable goals and steps for implementation. For example, if DEI training programs did not exist at U-M, they would need to be developed before asking members to participate in them. The committee then developed a mission statement and a set of aspirational DEI goals (Table 3). These goals were further broken down for each of the department’s core constituencies: undergraduate students, graduate students and postdocs, staff, and faculty—including tenured and tenure-track, research, and teaching faculty. This approach required iterative discussions to narrow down compiled ideas for the strategic plan, but was worthwhile because it both provided an organizational structure for gathering input and helped each constituent group see themselves in the plan. It also reminded the department how strategies for addressing DEI issues might need to vary for each stakeholder group. For example, strategies for recruiting undergraduate students differ from those needed for recruiting assistant professors.

Table 3. Summary of key elements of the University of Michigan Department of Mechanical Engineering’s strategic plan and implementation for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

After drafting the plan, the DEI strategic planning committee gathered department feedback in two stages. First, we circulated the draft plan to department leadership (consisting of the department chair and associate chairs), staff in our department’s Academic Services Office, and the undergraduate program and graduate program faculty committees. Their feedback was incorporated into the next iteration of the DEI strategic plan, which increased the number of contributors to the plan to over 30 people. Next, we expanded input to the entire department by gathering feedback from each of our constituency groups using surveys and town halls. Town halls were held separately for students and postdocs, for staff, and for faculty. During these town halls, attendees were asked to share feedback on the aspirational goals in the plan, including critiques and ideas related to parts of the plan specific to their department role. To help students and postdocs feel comfortable sharing feedback, student leaders facilitated the student and postdoc town halls, captured responses anonymously, and aggregated data for the strategic planning committee to review. This process of gathering feedback not only provided helpful suggestions for the final strategic plan, but also served to begin normalizing conversations about DEI in our department.

After the strategic plan was approved, we began strengthening the organizational infrastructure to support and sustain the work of implementing the department’s DEI strategic plan. This work was inspired in part by the concepts of infrastructuring and shared leadership. Infrastructuring involves “participat[ing] in the ongoing, active, and collective work of (re)forming infrastructure” (Hammond et al., 2022, p. 38). Shared leadership “involves multiple people influencing one another across varying levels and at different times” and helps build resiliency for DEI work because groups are able “to learn, innovate, perform, and adapt to the types of external challenges that campuses now face and that will continue to shape higher education moving forward” (Holcombe et al., 2023, p. 1). Work in this phase included (Table 1):

• Solidifying funding, a core DEI leadership team, and project management tools;

• Identifying a few areas of the strategic plan to begin working on; and

• Recruiting leaders for the implementation team.

Our first steps in developing infrastructure to sustain DEI work included creating a three-year budget and working with department leadership to integrate DEI needs into the department’s annual budgeting process. It also involved creating new DEI positions, including an Associate Chair for DEI and a full-time Manager of Diversity and Inclusion. Importantly, these positions were designed to have direct links and opportunities to collaborate with department faculty and staff leadership—which helps integrate DEI into the department decision-making process. The core DEI leadership (Table 3) also designed a system for organizing, communicating, and tracking progress of everyday DEI work. This system uses collaborative software for sharing documents with team members and partners, as well as project management software for tracking project progress, tasks, ideas, and feedback. These tools were created to help centralize information and retain institutional memory—which are often common challenges to sustaining DEI efforts, especially when there is turnover in leadership or teams.

Because of how broad our department’s DEI strategic plan was, the core DEI leadership adopted a shared leadership approach. The department’s Manager of Diversity and Inclusion worked with staff to identify DEI projects that staff had interest in, but had not had sufficient time or resources to begin tackling. For example, our department’s Human Resources team decided to review the staff hiring process and create an inclusive hiring guide for search committees. Facilities and instructional lab staff worked with a local organization, the Disability Network Washtenaw Monroe Livingston, to identify ways of improving the physical accessibility of public spaces, research labs, and student machine shops in one of our main buildings. A team of faculty and staff co-created an annual faculty DEI retreat where faculty can have a regular, communal opportunity to reflect on and discuss how to integrate equity-focused teaching into their pedagogical practices. The student- and postdoc-led ME DEI Alliance was interested in organizing community events and learning opportunities throughout the year for all constituencies in our department, receiving financial support and mentorship from the department. We also found that maintaining a faculty DEI committee has helped sustain efforts in the department, even with recent college-level leadership changes and shifts in the landscape of higher education (Malcom, 2024). Some of the affordances of a faculty DEI committee are that they can maintain discussion and support for DEI among our faculty, identify new areas of need in our department, and meet with other decision-making committees in our department and college to advocate for changes.

As we designed and launched these projects, we strove to not overburden team members and to find ways that DEI labor would be financially compensated, support professional growth, count toward annual reviews, and/or address work area needs. Overall, sharing responsibility and leadership in DEI across our department has allowed us to simultaneously address multiple areas of our DEI strategic plan, leverage the specific expertise and varying perspectives of our DEI leaders, and stay more aware of changes in stakeholder needs and the broader social landscape of higher education at the university and beyond.

In this piece, we described how one department approached using strategic planning to more intentionally build DEI into its department infrastructure and culture. Our three-phase process is a singular example of how a department can engage in this kind of work. To help other departments design a strategic planning process that works for their own local contexts, we outline our process and provide “Questions for consideration” to help frame these actions in Table 1. In Table 3, we present an overview of the plan’s goals along with organizational structures for implementation. Finally, we end with a few additional lessons about strategic planning for department-level culture change.

1. It’s okay to start small and build off existing work. Although strategic planning provides a way to develop an ideal vision for change, the task of doing so can feel daunting and unattainable. Even with our department’s excitement around a DEI strategic plan, there was still some uncertainty about whether individuals and the department had enough tools, resources, time, and knowledge to meet the community’s DEI objectives. We found it helpful to address these uncertainties by giving ourselves license to develop objectives and implementation projects that start small, to examine what other departments and disciplines were doing for inspiration and ideas (e.g., Cronin et al., 2021; Stachl et al., 2021), to find DEI assessment tools and programs created by other universities and organizations (Brancaccio-Taras et al., 2022; DO-IT, 2024; Korte, 2019; McNair et al., 2020), and to use a broad set of success indicators that include the use of qualitative and affective data.

2. Embrace growth and flexibility as part of the process. A department’s DEI strategic plan succeeds and is more resilient to challenges when it has support from its community members, each of whom have different backgrounds, interests, and experiences with DEI and strategic planning. Including flexibility and growth as norms in your strategic planning process can help promote trust, collaboration, and innovation (Canning et al., 2020). Flexibility and growth also welcome individuals to engage differently with DEI work as their understanding of and interest in the topic grows—helping to encourage a culture of shared leadership (Holcombe et al., 2023) that provides a department with more people and resources to tackle setbacks, new challenges, or slower-than-anticipated change. Flexibility and growth also prepare a department to be responsive to its own community’s needs, feedback, and circumstances as they change over time.

3. Keep aiming for infrastructural changes. DEI strategic planning should attend to structural causes of inequity—including racial inequity in STEM (Holly, 2024; McGee, 2020). This work can be done by taking an infrastructural approach, where strategic planning in DEI focuses on making ongoing changes to specific components of a department’s culture—such as processes, policies, and norms. An infrastructural approach to DEI work also helps a department focus its attention on actions within its control that can lead to systemic changes addressing inequity and exclusion in the broader STEM community.

4. Build relationships and identify shared objectives with internal and external partners. A department’s strategic plan in DEI does not exist within a vacuum. A key part of developing a resilient infrastructure for DEI is to understand the broader ecology of actors and circumstances that influence your department’s DEI work. Identifying how your department’s DEI objectives overlap with a wide range of stakeholders can help maintain support for your department’s DEI efforts. For example, our DEI strategic plan is aligned not only with university, college, department chair, and associate chair priorities, but also with those of major professional societies (ASME, 2024) and accreditation boards (ABET, 2024) in our discipline. In addition, building relationships across the university has helped us adapt our DEI strategies as different needs in our department emerge. The expertise of U-M’s Office of the Vice President and General Counsel and Equity, Civil Rights, and Title IX Office have helped us navigate the dynamic and complex legal and policy landscapes associated with DEI, resulting in better programs that support our students, staff, postdocs, and faculty. Overall, building a widespread network of partners with shared objectives and diverse expertise helps a department sustain its DEI work even as changes in leadership and the broader higher education landscape occur.

These are some of the lessons we learned when we encountered challenges during our department’s DEI strategic planning process. When facing obstacles in this work, we encourage readers in STEM to remember that as engineers and scientists, we are trained to solve complex problems. It is within our capabilities to combine our ability “to gather, analyze, and interpret relevant data and to evaluate the efficacy of strategies we implement” with learned knowledge of DEI and address “the moral and ethical responsibility…to improve equity and inclusion in STEM” (Ormand et al., 2022, p. 280). Strategic planning is one way to begin merging skillsets together. It has provided our department with new opportunities for our community to come together, co-create commitments to DEI, and connect culture change initiatives that might otherwise be siloed, so that we can build a more broadly diverse, equitable, and inclusive culture in mechanical engineering and STEM higher education.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: statistics about department enrollment presented in this perspective were obtained through internal data sources at the University of Michigan. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Susan Cheng, Y2hlbmdzQHVtaWNoLmVkdQ==.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SJC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AMO-O: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. KG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for SJC was provided by the Tim Manganello / BorgWarner Department Chair of Mechanical Engineering Endowment. KG was funded by the Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Michigan.

The design and writing of the strategic plan would not be possible without the students on the DEI strategic planning team: Khalif Adegeye, Shannon Clancy, Nosakhare Edoimioya, Nathan Geib, Won Young Kang, Panagiota Kitsopoulos, Syeda Lamia, Victor Le, Shuyu Long, and Hang Yang. We extend our gratitude to the students, postdocs, staff, and faculty who have contributed time, energy, and feedback to the Department of Mechanical Engineering’s DEI strategic plan and implementation over the years—especially those on the ME DEI Alliance, Mechanical Engineering Graduate Council, Women and Gender Minorities in Mechanical Engineering, and the ME Staff/Faculty DEI Committee. We thank J. W. Hammond for his helpful feedback on this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ABET. (2024). ABET advances DEI-related criteria across all four commissions. Available at: https://www.abet.org/abet-advances-dei-related-criteria-across-all-four-commissions/ (Accessed September 11, 2024).

Armanios, D.E., Christian, S.J., Rooney, A.F., McElwee, M.L., Moore, J.D., Nock, D., et al. (2021). Diversity, equity, and inclusion in civil and environmental engineering education: Social justice in a changing climate. Presented at the 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access, Virtual Conference.

ASME. (2024). Diversity, equity, and inclusion. Available at: https://www.asme.org/about-asme/diversity-and-inclusion (Accessed September 11, 2024).

Brancaccio-Taras, L., Awong-Taylor, J., Linden, M., Marley, K., Reiness, C. G., and Uzman, J. A. (2022). The PULSE diversity equity and inclusion (DEI) rubric: a tool to help assess departmental DEI efforts. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 23, e00057–e00022. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.00057-22

Braun, D. C., Clark, M. D., Marchut, A. E., Solomon, C. M., Majocha, M., Davenport, Z., et al. (2018). Welcoming deaf students into STEM: recommendations for university science education. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 17:es10. doi: 10.1187/cbe.17-05-0081

Brown, H. P., and Morton, T. R. (2023). Sick and tired of being sick and tired. J. Eng. Educ. 112, 7–11. doi: 10.1002/jee.20501

Buchanan, D., Fitzgerald, L., Ketley, D., Gollop, R., Jones, J. L., Lamont, S. S., et al. (2005). No going back: a review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 7, 189–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x

Canning, E. A., Murphy, M. C., Emerson, K. T. U., Chatman, J. A., Dweck, C. S., and Kray, L. J. (2020). Cultures of genius at work: organizational mindsets predict cultural norms, trust, and commitment. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 626–642. doi: 10.1177/0146167219872473

Cech, E. A. (2022). The intersectional privilege of white able-bodied heterosexual men in STEM. Sci. Adv. 8:eabo1558. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo1558

Cech, E. A., and Rothwell, W. R. (2018). LGBTQ inequality in engineering education. J. Eng. Educ. 107, 583–610. doi: 10.1002/jee.20239

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2023). Disability impacts all of us Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html (Accessed July 7, 2024).

Chaudhary, V. B., and Berhe, A. A. (2020). Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16:e1008210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008210

Chen, C. Y., Kahanamoku, S. S., Tripati, A., Alegado, R. A., Morris, V. R., Andrade, K., et al. (2022). Systemic racial disparities in funding rates at the National Science Foundation. eLife 11:e83071. doi: 10.7554/eLife.83071

Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Michigan, (2021). Diversity, equity and inclusion committee roadmap.

Cronin, M. R., Alonzo, S. H., Adamczak, S. K., Baker, D. N., Beltran, R. S., Borker, A. L., et al. (2021). Anti-racist interventions to transform ecology, evolution and conservation biology departments. Nature Ecol. Evol. 5, 1213–1223. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01522-z

DO-IT. (2024). Available at: https://www.washington.edu/doit/programs (Accessed July 11, 2024).

Fisher, K. Q., and Henderson, C. (2018). Department-level instructional change: comparing prescribed versus emergent strategies. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 17:ar56. doi: 10.1187/cbe.17-02-0031

Freeman, J. B. (2021). STEM disparities we must measure. Science 374, 1333–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.abn1103

Fries-Britt, S., Kezar, A., McGuire, T. D., Dizon, J. P. M., Kurban, E. R., and Wheaton, M. M. (2024). Forever changed: Healing & rebuilding through ongoing crisis. About Campus 29, 16–23. doi: 10.1177/10864822241238167

Hammond, J. W., Brownell, S. E., Byrd, W. C., Cheng, S. J., McKay, A., and Tarchinski, N. A. (2022). Infrastructuring to scale multi-institutional equity and inclusion innovations. Change 54, 37–43. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2022.2101866

Hart, J., and Fellabaum, J. (2008). Analyzing campus climate studies: seeking to define and understand. J. Divers. High. Educ. 1, 222–234. doi: 10.1037/a0013627

Holcombe, E. M., Kezar, A. J., Elrod, S. L., and Ramaley, J. A. (Eds.). (2023). Shared leadership in higher education: A framework and models for responding to a changing world. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Holly Jr, J. (2024). “Righting wrongs: (re)defining the problem of Black representation in U.S. mechanical engineering study” in Handbook of critical whiteness: Deconstructing dominant discourses across disciplines. eds. J. Ravulo, K. Olcoń, T. Dune, A. Workman, and P. Liamputtong (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 1–17.

Holly Jr, J., and Comedy, Y. (2022). Whitey on the moon: racism’s maintenance of inequity in invention & innovation. Technol. Innov. 22, 331–340. doi: 10.21300/22.3.2022.7

Jeannis, H., Goldberg, M., Seelman, K., Schmeler, M., and Cooper, R. A. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to students with physical disabilities’ participation in academic laboratory spaces. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 15, 225–237. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2018.1559889

Kezar, A. (2023). Provocation 5: culture change requires adept shared leadership. Change 55, 2–3. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2023.2213568

Kezar, A., Eckel, P., Contreras-McGavin, M., and Quaye, S. J. (2008). Creating a web of support: an important leadership strategy for advancing campus diversity. High. Educ. 55, 69–92. doi: 10.1007/s10734-007-9068-2

Korte, A. (2019). SEA Change honors diversity efforts by universities. Science 364, 844–845. doi: 10.1126/science.364.6443.844

Langin, K. (2024). LGBTQ Ph.D. graduates will soon be counted in key U.S. survey : Science. doi: 10.1126/science.z0d1u4l

Leake, D. W., and Stodden, R. A. (2014). Higher education and disability: past and future of underrepresented populations. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 27, 399–408.

Leaper, C., and Starr, C. R. (2019). Helping and hindering undergraduate women’s STEM motivation: experiences with STEM encouragement, STEM-related gender Bias, and sexual harassment. Psychol. Women Q. 43, 165–183. doi: 10.1177/0361684318806302

McGee, E. O. (2020). Interrogating structural racism in STEM higher education. Educ. Res. 49, 633–644. doi: 10.3102/0013189X20972718

McNair, T. B., Bensimon, E. M., and Malcom-Piqueux, L. (2020). From equity talk to equity walk: Expanding practitioner knowledge for racial justice in higher education. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Michigan Engineering Office of Culture, Community and Equity. (2024). DEI 1.0 Available at: https://culture.engin.umich.edu/dei-1-0/ (Accessed July 11, 2024).

Miller, R. A., Vaccaro, A., Kimball, E. W., and Forester, R. (2021). “It’s dude culture”: students with minoritized identities of sexuality and/or gender navigating STEM majors. J. Divers. High. Educ. 14, 340–352. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000171

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (2023). Diversity and STEM: Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities 2023. (No. Special Report NSF 23–315). Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation.

National Science Board (2020). Science and Engineering Indicators 2020: The State of U.S. Science and Engineering. Vision 2030. Report # NSB-2020-15. Alexandria, VA. Available at: https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/nsb/publications/2020/nsb202015.pdf

Ong, M., Smith, J. M., and Ko, L. T. (2018). Counterspaces for women of color in STEM higher education: marginal and central spaces for persistence and success. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 55, 206–245. doi: 10.1002/tea.21417

Ormand, C. J., Macdonald, R. H., Hodder, J., Bragg, D. D., Baer, E. M. D., and Eddy, P. (2022). Making departments diverse, equitable, and inclusive: engaging colleagues in departmental transformation through discussion groups committed to action. J. Geosci. Educ. 70, 280–291. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2021.1989980

Patton, L. D., Sánchez, B., Mac, J., and Stewart, D.-L. (2019). An inconvenient truth about “Progress”: an analysis of the promises and perils of research on campus diversity initiatives. Rev. High. Educ. 42, 173–198. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2019.0049

Sjoding, M. W., Dickson, R. P., Iwashyna, T. J., Gay, S. E., and Valley, T. S. (2020). Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2477–2478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2029240

Spencer, B. M., Artis, S., Shavers, M., LeSure, S., and Joshi, A. (2022). To code-switch or not to code-switch: the psychosocial ramifications of being resilient Black women engineering and computing doctoral students. Sociol. Focus 55, 130–150. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2022.2054482

Stachl, C. N., Brauer, D. D., Mizuno, H., Gleason, J. M., Francis, M. B., and Baranger, A. M. (2021). Improving the academic climate of an R1 STEM department: quantified positive shifts in perception. ACS Omega 6, 14410–14419. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c01305

U.S. Census Bureau, (2023). Population estimates, July 1, 2023, (V2023). Quick Facts. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045222 (Accessed July 7, 2024).

U-M ODEI, (2024a). DEI 1.0 Archives (2016-2021). Available at: https://diversity.umich.edu/dei-strategic-plan/dei-1-0-archives/ (Accessed September 11, 2024a).

U-M ODEI, (2024b). Legal Context. Available at: https://diversity.umich.edu/about/history/legal-context (Accessed September 11, 2024b).

Keywords: diversity, inclusion, equity, strategic planning, higher education

Citation: Cheng SJ, Ortiz-Ortiz AM and Grosh K (2025) Engineering change: strategic planning to build a department culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion in mechanical engineering. Front. Educ. 10:1469889. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1469889

Received: 24 July 2024; Accepted: 27 January 2025;

Published: 02 April 2025.

Edited by:

Xiang Hu, Renmin University of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Stephanie M. Gardner, Purdue University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Cheng, Ortiz-Ortiz and Grosh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan J. Cheng, Y2hlbmdzQHVtaWNoLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.