94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ., 12 February 2025

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1465714

In literate societies of the 21st century, written language plays a crucial role in both the professional and social life of individuals. Consequently, educational reforms emphasize the development of literacy skills in children. The ability to read and comprehend text is fundamental for individuals to fully engage and succeed in social contexts. Existing research supports that reading and writing are active cognitive processes essential for understanding and producing messages, and that there is a direct connection between children’s drawing and speech. Based on the above, a descriptive case study took place to look for evidence and provide examples of how a preschool child’s narrative drawings relate to early literacy skills. Narrative drawings are defined as sketches that are accompanied by a story told by a child while drawing or when presenting the final artwork. This study analyzed 35 narrative drawings, produced by a child between her four-and-a half and fifth year of age. The accompanying stories were recorded and transcribed for analysis purposes. Qualitative content analysis of both the drawings and the transcribed narratives provided evidence that narrative drawing promotes children’s reading readiness and offers opportunities for early literacy development.

In literate societies of the 21st century, written language plays a decisive role in both the professional and social life of individuals. Written language is essential for clear communication whether texts are intended for reporting or documenting facts, keeping records, giving instructions, conveying ideas, or disseminating knowledge in professional contexts. In social contexts, written language allows individuals to express thoughts, feelings and identities, through sharing experiences and perspectives, and to connect regardless of distance. Great importance is attached to individuals’ ability to read and understand what they read, since this ability is the basis for their fullest participation and success in social contexts (Lenhart et al., 2021; Manolitsis, 2016). Reading and writing are considered active thinking processes which are essential for making meaning, understanding, and producing messages, rather than merely developing explicit skills (Neumann, 2022; Dafermou et al., 2006). Reading and writing are not just about acquiring specific skills like vocabulary, grammar, or punctuation. They involve a holistic engagement where individuals actively interact with texts to construct meaning and communicate effectively. This perspective highlights the fluidity and adaptability inherent in both reading and writing.

Consequently, current research trends in education focus on activities and interventions that promote the coding and decoding of written language and developing literacy in various contexts. Effective literacy pedagogy requires engaging children with different types of texts—both oral and/or written—which have personal meaning, and also relate to the social reality they experience (Doumanidou et al., 2016). Literacy in education is considered a dynamic process with an emphasis on the continuous, evolving nature of reading and writing, shaped by active engagement, contextual influence, iterative development, and ongoing learning. Children’s social interactions play a crucial role in shaping distinctive learning experiences (Neumann, 2022).

Considering reading and writing as active thinking processes highlights the importance of cognitive engagement in meaning-making, text comprehension, and message production. It is essential for parents and educators to recognize the significance of early book reading, as it plays a crucial role in fostering the development of emerging literacy skills (Lenhart et al., 2021). As Neumann (2022) suggests, the cultural context, linguistic background, and effective practices during early childhood can significantly influence children’s development in reading and writing. He asserts that children’s learning should be supported through a variety of activities and individualized approaches. A creative activity involves the use of children’s drawings to encourage them to describe and narrate the stories embedded within their visual representations. This method not only supports the development of their oral language skills but also facilitates an understanding of the relationship between spoken and written language. Yiannikopoulou (2016) notes, for example, that when children depict their own characters in their drawings, they begin to recognize how the way in which the characters’ names are written can mirror their personalities. For instance, the name “Snow White” might be written in white, while the name of a character who is constantly dancing might be written in a circular form. Contemporary educational approaches have increasingly focused on examining the learning trajectories of young children, beginning in the early years of development. Consequently, it is essential to engage children in a variety of activities and experiences that can strengthen their reading and writing abilities (Yiannikopoulou, 2002). This perspective poses particular challenges for early childhood educators.

Vygotsky (1978) developed the theory of the Zone of Proximal Development, which posits that learning and development are social processes occurring through interaction with more experienced individuals. This approach is particularly significant for understanding how children develop literacy skills. The contribution of an adult, along with the various strategies and stimuli provided to the child, helps the child mature and decode written language. These are abilities and functions that the child possesses but are still in the process of maturation. Vygotsky proposed that language and thought develop independently, yet they merge in early childhood to form unique ways of thinking and communicating (Rieber, 2012). One way of communicating and expressing ideas and thoughts is artmaking in any form it can take. Vygotsky was among the first scholars who noticed that children often draw and tell a story simultaneously, indicating a direct relationship between a child’s drawing and speech. Vygotsky (1978) argued that children’s drawings are deeply connected to their innate narrative impulse, which becomes evident in their earliest attempts at representational art. This impulse, drives children to embed stories within their drawings, transforming visual representation into a medium for storytelling. Furthermore, the social and communicative dimensions of drawing are significant, as children often engage in verbal narration or discussion that complements and enhances the drawing process. These interactions highlight the intertwined nature of visual and verbal expression in early childhood, underscoring how drawing functions as both a creative and communicative act. This type of communication, as a personal conversation between an individual and his/her creation, can become a common language, when shared with other group members (Brooks, 2009).

Since the early 1980s, artmaking has been thought of and investigated as symbol producing and perceiving activity. It has been considered a form of language involving learning to navigate and utilize a system of symbols to convey meaning, connect with others, and express ideas, just as verbal language does in a more structured way (Perkins, 1980; Gardner, 1980; Gardner, 2011; Geoghegan, 1994). This perspective, which is central to the theory of Multiple Intelligences (Gardner, 1983), contrasts with Piaget’s view of integrated, cross-domain developmental stages (Piaget, 1985). The theory of Multiple Intelligences proposes that meaning is constructed not solely through intellectual processes, but by integrating the intellect with sensory experiences. Gardner (1983) argued that instead of a singular, general intelligence, individuals possess at least eight distinct intelligences: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. His pioneering research with children, particularly through Project Zero, revealed that the arts are embedded within these intelligences, demonstrating their integral role in human cognitive development (Sidelnick and Svoboda, 2000).

Acknowledging the communicative potential in young children’s artistic language (Perkins, 1980; Hall, 2020) and the relationship between children’s drawing and speech, the purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between children’s drawings with free choice of subject matter in relation to early literacy. More specifically, we aimed to describe how could a young child’s involvement in narrative drawing contribute to acquisition of early literacy. For the purposes of this study, narrative drawings are described as sketches that are accompanied by a story told by a child while drawing or when presenting the artwork immediately after its completion.

Emergent literacy refers to the period before formal reading and writing instruction when a child develops foundational skills necessary for literacy. It is a term that encompasses the ability to decode written language and understand its message, as well as producing coded messages before children receive formal education (Manolitsis, 2016; Puranik and Lonigan, 2012). Emergent literacy is a complex phenomenon encompassing a range of knowledge, skills, attitudes and experiences that set the stage for later reading and writing success. Literacy knowledge pertains to a child’s understanding of the written word before formal education, while literacy skills denote how children exhibit this knowledge (Rhyner et al., 2009). The term “emergent literacy” was first introduced by Clay (1966) in her doctoral dissertation. Today, the term is widely recognized and refers to an evolutionary process toward learning, rather than teaching, beginning with a child’s early experiences and continuing through formal education. It denotes the child’s ability to use written language, particularly when written language is prevalent in their environment. This process encompasses phonological awareness, vocabulary development, oral language comprehension, and the recognition of written symbols (Doyle, 2019; Manolitsis, 2016).

A multitude of studies corroborate that literacy acquisition stems from the children themselves, from infancy, and flourishes when nurtured in an environment conducive to and abundant in writing experiences (Sandvik et al., 2014). Emergent literacy combines multiple cultural, social, historical, and cognitive aspects as it is fostered through interactions with adults, exposure to print materials, storytelling, and other language-rich experiences (Dickinson and Neuman, 2006). Children’s main source of stimuli related to literacy during early childhood is their family as well as the wider community which they are part of.

Learning to read and write are interrelated processes that evolve in tandem with oral language development (Labbo and Teale, 2013). Language processing—including hearing, listening, speaking, reading, and writing—matures in an interconnected fashion, with each facet shaping the others. This perspective of interconnected language processes is embodied in the Early Childhood Education Curricula of Cyprus, where this study took place. In terms of language education and literacy skill development, emphasis is placed on curating experiences within the ambit of children’s interests and capabilities, fostering their socialization through language, and nurturing literate identities that meld communication skills (both verbal and non-verbal) and diverse uses of language (both oral and written). Achieving these goals necessitates active engagement in child-relevant activities and interaction with their social environment, as evidenced by pertinent research (Manolitsis, 2016; Puranik and Lonigan, 2012). Emphasis is laid on the notion that reading and writing are not isolated skills, but active cognitive processes engaged in constructing meaning, comprehension, and message creation (Neumann, 2022; Lenhart et al., 2021).

Everyone perceives the world through the lens of their own culture. The values, beliefs, experiences, and knowledge acquired from their cultural context shape the way they think, learn, and interact with others. Each child, depending on the stimuli and experiences they encounter, interacts with other children within the framework of their family life, helping them connect language with their identity and culture. Given these factors, educators must be sensitive to the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of each child. Cultural diversity and children’s prior experiences can serve as enriching elements in the process of their language development (Sperry and Sperry, 2021). School literacy encompasses not only the technical skills involved in learning the written language coding system but also various other accomplishments within the multimodal communicative environment of our time. Literacy is not merely the ability to decode written language or encode spoken language, but also the functional use of language in different communicative contexts (Apostolou and Stellakis, 2020). One form of literacy is children’s drawing. Drawing involves the ability to observe, analyze, and synthesize perceptual impressions of the world, informed by experiences and cognitive abilities (Efland, 2004).

Narrative drawing is an art form that combines visual expression with storytelling. In narrative drawings, the drawn image is accompanied by a verbally expressed story that is directly related to the visual representation of the subject matter. Lev Vygotsky was one of the first to observe how children draw and tell a story at the same time, pointing out the direct relationship between the drawing and the child’s speech (Rieber, 2012). Similarly, Elliot Eisner emphasized the significance of each child’s intimate ‘conversation’ with their sketches, which dynamically unveils scenes from their daily life and imagination, akin to a cinematic sequence (Eisner, 1996). Children from a very young age learn that they can create signs and marks which can stand for something else (symbolism). Young children’s signs are initially made and then named, and at a later stage, signs are named before being made. In either case, young children can recognize that visual forms can be transformed into symbols. Eisner contends that while symbolic drawing is commonly perceived as a means of communication, its primary role is the articulation of thought. Symbol-making is a natural human capacity that requires abstraction and transformation of one concept into another (Eisner, 2005). Children use the images they create to construct an understanding of their world and convey what they know to others.

Brooks (2005) underscored the role of children’s markings as a tangible manifestation of thought, referring to this as ‘visual thinking.’ She also proposed that these markings serve as tools to stimulate both intra- and interpersonal dialogs, facilitating children in constructing meanings independently. She considered these traces as a form of visual language possessing three essential functions. The ideational function presents the child’s experiences in a visual format, while providing a depiction of their social reality. The second function, the interpersonal, pertains to the child’s relationship with the portrayed subjects and their interaction with the viewer. Lastly, the textual dimension concerns the depicted objects themselves (including any accompanying written or spoken text) and how they interrelate to convey a holistic narrative.

Tsikalaki (2005) posits that interest in children’s artwork encompasses the blending of writing and drawing often found in children’s artworks, reminiscent of primitive iconographic scripts. Forming images that are intended to correspond to aspects of the world is a structure-seeking process with no predetermined clear standards for a young child. In spelling, standards are clear and one can spell a word either correctly or incorrectly. On the contrary, symbolic images have no such standards. Children rely upon their sensibilities and perceptions to determine the adequacy of the visual symbols they create. Another thing that children learn when they create images, as Eisner (2005) pointed out, is that their visual symbols can be related to other symbols to form a whole, just like letters in a word, words in a sentence, sentences in paragraphs, and so forth. During this study, it was hypothesized that encouraging an intellectually independent child, autonomous in creating symbolic images, to express her stories while or after completing her drawings, would make her language visible to the teacher and provide evidence connecting visual and verbal representations.

Perkins (1980) discussed “literalism,” a developmental phenomenon which occurs in the primary school years, when young artists appear to become less imaginative. Formal investigations have disclosed that primary school children’s artistic “language” becomes more straightforward, less venture-some and expressive. How to render something correctly becomes more of a concern. Furthermore, literalism appears also in the talk of children, where there is a decline in the use of fresh metaphors and a certain scorn for metaphorically “roundabout” ways of saying things. At best, this period seems unfortunate, and, at worst, literalism appears as the “dead-end” of artistic development. It is, therefore, important to examine the meanings young children express in talk and pictures before they develop “literalism.” Dyson (1986) considered drawing as a major writing strategy for young children and stressed the importance in understanding the connections between the worlds that young children create through talk and drawing.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between a preschool child’s narrative drawings and early literacy skills prior the literalism period. Given the individuality of each person’s artistic expression and the unique way each child develops symbolic drawing, this descriptive case study focused on the connection between a child’s involvement in narrative drawing and the acquisition of early literacy. Thirty-five narrative drawings created by a child were collected and analyzed through qualitative content analysis. The child that participated in the study was a female between her four-and-a half and fifth year of age, called Maria. The 35 narrative drawings selected by the researchers were produced over a span of 6 months. Maria was observed by her parents to draw daily an average of two drawings at home and enjoyed their attention when she described her work. The practice of having an adult transcribe her descriptions was a routine that she adopted from preschool and since her mother expressed great interest in this routine, the child continued it at home and enjoyed the praise she received from her mother. The mother informed the child that an expert friend would be interested in studying her drawings of stories, and this proved to have further enhanced the child’s narrative drawing attempts. There was no guiding instruction about what she should draw, ensuring spontaneity and freedom in her art. Her stories were transcribed by her mother, either while she was drawing or after she completed a drawing.

The 35 of Maria’s drawings along with the accompanying recorded stories were independently examined by each of the two researchers to ensure a high degree of reliability of the data. Specifically, researchers examined each drawing based on:

1. Subject matter, elements and principles of design, such as lines, shapes, space, and emphasis.

2. The child’s recorded oral narratives for each drawing, focusing on structure, length, expression, syntax, and vocabulary.

Gardner (2017), reflecting on his early studies, noted that young children in contemporary developed societies are increasingly exposed to technology that offers a diverse range of patterns, shapes, and visual narratives. He emphasized the importance of considering cultural signals, such as those from mass media, peers, siblings, and parental influences, when analyzing children’s drawings. These cultural indicators informed the categorization of subject matter, themes, and topics within the drawings, which were identified through recognizable symbols and corroborated by the transcribed stories narrated by the child. Following this, the drawings were further analyzed through elements and principles of design, including line, shape, space, and emphasis, to identify the symbols that served as metaphors for various story elements. Verification of these visual symbols was conducted in parallel with the written narratives, with detailed notes recorded in a table for each drawing to ensure a comprehensive analysis.

Maria’s recorded oral narratives for each drawing were also systematically analyzed and categorized to explore their structural composition. This analysis focused on determining whether the narratives included distinct elements of a beginning, middle, and end, and whether these components were visually represented in the drawing and their respective placement on the picture plane. Additionally, the stories were classified by length and assessed in terms of linguistic features, including expression, syntax, and vocabulary. More specifically, the stories were further categorized based on their length to analyze variations in narrative complexity and detail and compare it to the visual complexity based on number of elements on the picture plane. Each narrative was examined for linguistic features, including the richness of expression, the structure and coherence of syntax, and the diversity and appropriateness of vocabulary.

Correlations between the visual and the linguistic content of each narrative drawing were identified and provided evidence for the symbols presented in the images and mentioned in the stories. Integrated analysis allowed for a comprehensive understanding of how visual and linguistic elements worked together to communicate the story. This methodological approach allowed for a comprehensive understanding of how narrative drawing activities, placed in chronological order of creation can support early literacy development, offering valuable insights into the cognitive and the communicative processes involved in relation to developing patterns regarding either the visual or the linguistic symbolism. Maria’s drawings were studied beyond shapes and lines on paper but as language expressing imagined worlds, worlds of time and space, and of actors, objects and actions (Dyson, 1986).

All of Maria’s drawings were accompanied by a story, each with a clear beginning, middle and ending. The sequential order of events described orally was often reflected in the visual symbols within the drawings. For example, in Drawing #2 (Figure 1), the story narrates an unpleasant event for one individual, followed by a reaction of kindness by another individual, Maria, who is then praised with a prize. The painting features a long, continuous curved line enclosing various toys, possibly symbolizing a storm or the rescue of the toys. A circular shape on the right may symbolize the cave in which the two friends were playing making the correspondence of story with the drawing evident. Visual symbols were recognizable and relevant to the corresponding stories in all drawings. In most drawings researchers found elements from every phase of the story.

In all drawings, the elements of the story were positioned on the surface according to their importance in the sequence of events described orally. The beginning of the story featuring the protagonist, was drawn in the center of the page and in most cases, the story visually evolved in a random position on the page based on available space. However, there were a few cases such as in Drawing #16 (Figure 2), where the linear visual representation of symbols from left to right, resembled written language.

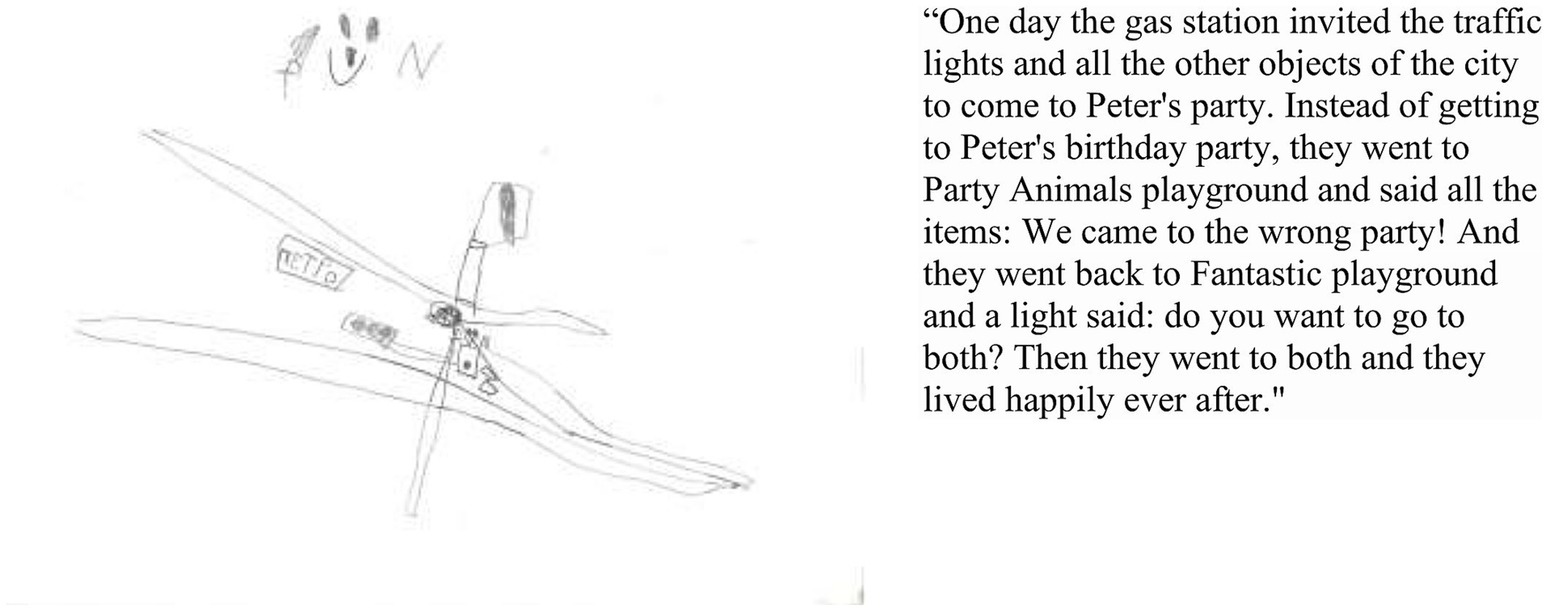

Maria’s habit of illustrating narratives yielded a collection of images and stories that integrated both realistic and imaginative elements which gradually became more elaborate and detailed in both aspects. Whether the story involved following a cat’s footprints or creating a horse out of muffins, Maria often attempted to write in her drawings. Letters and numbers appeared in some drawings, and all drawings included repetition of lines and shapes, such as long vertical parallel lines for a cage, long curvy lines for trails, small curves or straight lines next to each other horizontally representing roof tiles or waves. These visual elements paralleled written language, indicating Maria’s developing comprehension of the concept of print as an emergent reader and writer. She also seemed to understand that writing is intertwined with social life, which is also a characteristic of emergent readers and writers. For example, Drawing#12 (Figure 3) looks like a map that aims to orient viewers toward a birthday party in a street scene with traffic lights and a gas station, demonstrating perception of space and time, which also relates to writing.

Figure 3. Drawing #12 with story demonstrating developing comprehension of the concept of print and perception of space and time.

Maria’s ability to formulate and express sentences developed throughout the period of data collection. Over time she composed longer sentences, used past and future tenses appropriately, used conjunctions, understood the permanence of written language. Maria herself requested that her descriptions be transcribed while or after drawing, giving meaning to what she drew. In Drawing#23 (Figure 4), for example, Maria started with a title and the sequence of events are described in the form of dialogs, while the image included a detailed representation of all characters.

The categorization of subject matter, themes, and topics in Maria’s drawings revealed the presence of cultural indicators (Gardner, 2017), as identified through recognizable visual symbols corroborated by her oral narratives. A significant number of these symbols was derived from mass media, particularly characters from children’s films and classic fairy tales. Additionally, familial themes were prominent, with frequent depictions of Maria’s two younger brothers or representations of five-member families engaged in various playful activities, such as walking in a line reminiscent of a train. Notably, a symbolic representation of a family of birds in a nest mirrored her own family structure, consisting of a father, mother, and three young birds. Beyond familial influences, peer relationships emerged as another cultural indicator, with Maria’s drawings often portraying both specific and unspecified friends engaged in social activities, such as playing or attending birthday celebrations. Even in drawings featuring highly imaginative subject matter, the inclusion of symbols, such as a question mark within a cloud above a character’s head, arrows indicating direction, or street signs with invented spelling, appeared to reflect the child’s efforts to expand her communicative repertoire. As Cazden (2017) observed, children acquire language primarily as a means of engaging with and expressing their understanding of the world around them, rather than for the purpose of discussing language itself.

Emergent literacy was evident in most drawings, where Maria demonstrated phonological awareness, knowledge of letters and numbers, understanding the concept of print, and a gradually developed vocabulary and comprehension skills. Maria’s ability to create and reproduce stories (narrative drawing) seemed directly related to emergent literacy. It was an activity that engaged the child and it was frequently practiced at home and at the preschool. The way in which parents and, as well as teachers utilized this activity helped Maria to develop skills such as understanding and using new words, as well as structuring and organizing her thoughts with a beginning, middle, and end.

Emergent literacy is a crucial stage in a child’s development, serving as the foundation for future success in reading and writing. Educational projects and programs are designed to equip children with the skills and knowledge required to become proficient readers and writers (Hutton et al., 2021). Parents and educators are provided with guidance to foster children’s literacy development, recognizing that the role of the adult is fundamental in establishing the groundwork for the child’s success.

The foundation of literacy is established during the early years of a child’s life and is shaped by their experiences and interactions within their environment. Drawing on Lev Vygotsky’s theoretical framework, learning and development are conceptualized as social processes facilitated through interactions with more knowledgeable individuals. This perspective holds particular significance for parents and educators, emphasizing that the development of reading and writing skills is not solely a matter of instruction but also a dynamic process of learning (Yiannikopoulou, 2002).

Children become cognizant from a very early age that writing serves as a vessel for messages. To foster this realization, it is essential to provide an environment conducive to supporting the child throughout this process. Kennedy and McLoughlin (2023) emphasize the pivotal role of early childhood educators in equipping children with language development strategies and nurturing emergent literacy skills prior to their entry into primary school. They argue that early childhood educators have the potential to play a decisive role in ensuring a high-quality preschool curriculum, thereby preparing children effectively for their subsequent educational journey.

Drawing plays a significant role in literacy development. Children frequently narrate stories about their drawings by incorporating random letters of the alphabet or various signs (pseudograms), or symbols they observe in their environment. When prompted to ‘read’ their drawings, children can often articulate a clear message or story. Children aged 5–6 may recognize drawing as an explanatory form of communication, yet they continue to use it as a precursor to writing. The progression from drawing to making writing marks and eventually reading, facilitates the understanding of language mechanics and spelling conventions.

Narrative drawing, that is, artmaking accompanied by storytelling proves to be a fun activity for coding and decoding language and developing literacy. During narrative artmaking, children orally describe and assign meaning to the visual symbols of their work. Narrative drawing is inextricably linked to oral and written language development and as an interactive learning environment that engage learners in the incorporation of contextualized literacy experiences (Kim, 2018) it could facilitate more effective concept formation in young children.

Eisner advocated a strict, more sophisticated and rigorous arts curriculum that would put arts instruction on par with lessons in reading, science and math. He argued that to neglect the contribution of the arts in education, either through inadequate time, resources or poorly trained teachers is to deny children access to one of the most stunning aspects of their culture and one of the most potent means for developing their minds (Eisner, 2005).

In our rapidly evolving world, children encounter numerous challenges that will necessitate applying creativity and imagination. Imagination, instrumental in facilitating children’s understanding of reality, finds an unencumbered outlet in narrative drawing. Art, serving as an expressive conduit, can aid in numerous aspects of our lives, one of them being literacy. By narrating stories through their drawings, children cultivate oral expression—a fundamental skill for the progression of literacy. In essence, a child’s sketch is a visual manifestation of thought, a channel for both intrapersonal and interpersonal dialogs aiming at constructing meaning.

Weadman et al. (2023) suggested a range of linguistic experiences and emergent literacy concepts that a preschool teacher can incorporate to facilitate learning in school settings, such as drama and roleplays, responsive and high-quality adult–child interactions, music and songs promoting sound discrimination and word play with rhyme, or dialogic book reading. This study illuminates the integral role of narrative drawing and literacy development. It underscores the importance of fostering an environment that encourages creative expression and highlights the role of adults in steering this process. Narrative drawing can develop oral language competence and emergent literacy while promoting children’s active participation in various contexts. Narrative drawings serve as a foundational element for emergent literacy, as they assist children in understanding the organization of written language and in developing communication and writing skills. Additionally, they enhance phonological awareness by helping children comprehend the sounds of the language. Consequently, the creation of rich, supportive, and linguistically stimulating environments is essential for fostering literacy from the early stages of life.

Sidelnick and Svoboda (2000) case study of the role of artmaking for a first-grader with learning difficulties revealed that drawing can move children from the visual to the spoken and then to the written. The acknowledgment of the developmental significance of drawing is closely linked to a focus on authenticity in the writing process. This perspective holds that children learn to read and write most effectively when they engage with texts they have personally created. Typically, these initial written expressions take the form of labels, captions, and brief narratives that children either dictate or write to provide additional context, clarification, or elaboration on their drawings. Such activities, as also found in this study, not only support the development of literacy skills but also foster a deeper connection between visual and written forms of expression, enhancing children’s understanding of both modes of communication. This study invites further exploration into novel, art-based pedagogical strategies aimed at enhancing literacy, thereby reinforcing the potential of art as an instrumental tool in child development and education. Studying and analyzing both the drawings and the transcribed stories of a preschool child provided evidence that narrative drawing promotes children’s reading readiness and offers opportunities for meaning making in exciting for the children, self-directed, ways. All types of multimodal expression as a phenomenon of communication (Rodosthenous et al., 2019) are worth studying in education for different age groups, combining different semiotic resources, or modes, in texts and communicative events, such as still and moving image, speech, writing, or movement. The arts are interwoven with other intelligences, offering a means to create learning environments that extend beyond conventional classroom methods, which often focus primarily on linguistic and logical-mathematical skills (Sidelnick and Svoboda, 2000). Geoghegan (1994) emphasized the importance of helping children “see bridges between the disciplines” and enabling them to “discover how ideas are connected” (p. 458).

Further research on the integration and application of diverse semiotic resources within education is critical for preparing children to participate meaningfully in an increasingly complex and technology-driven world. Understanding and leveraging the potential of diverse semiotic resources is crucial for preparing children to navigate and communicate in a rapidly evolving technological landscape. Rapid technological advancements increasingly incorporate multiple modes of communication, such as visual, textual, and auditory, into contemporary societies, necessitating that children acquire the ability to interpret and construct meaning across these diverse modalities. Developing such competencies enables them to navigate digital environments effectively, engage in multimodal forms of communication, and adapt to continuously evolving methods of expression and information exchange.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

EP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Apostolou, Ζ., and Stellakis, N. (2020). Οι εκπαιδευτικοί της πρωτοσχολικής ηλικίας γνωρίζουν τα επίσημα κείμενα και τις πρακτικές γραμματισμού που λαμβάνουν χώρα στη βαθμίδα που έπεται ή προηγείται της δικής τους; [Do early childhood educators know the official texts and literacy practices that take place in the grade level before or after their own?]. Επιστημονική Επετηρίδα Παιδαγωγικού Τμήματος Νηπιαγωγών Πανεπιστημίου Ιωαννίνων 13, 1–51. doi: 10.12681/jret.22149

Brooks, M. (2005). Drawing as a unique mental development tool for young children: interpersonal and intrapersonal dialogues. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 6, 80–91. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2005.6.1.11

Brooks, M. (2009). What Vygotsky can teach us about young children drawing. Int. Art in Early Childhood Res. J. 1, 1–13.

Cazden, C. B. (2017). Communicative competence, classroom interaction, and educational equity: The selected works of Courtney B. Cazden: Routledge.

Clay, M. M. (1966). Emergent reading behaviour. Doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland Library, New Zealand.

Dafermou, C., Koulouri, P., and Basagianni, E. (2006). Oδηγός Nηπιαγωγού: Eκπαιδευτικοί σχεδιασμοί. Δημιουργικά περιβάλλοντα μάθησης [Teacher’s guide: Educational planning. Creative learning environments]. Athens: OEDB.

Dickinson, D. K., and Neuman, S. B. (2006). Handbook of early literacy research, vol. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Doumanidou, S., Contopoulou, A., and Dina, M. (2016). Εφαρμοσμένες γλωσσικές δραστηριότητες: Γέφυρες επικοινωνίας και γραμματισμού [Applied language activities: Communication and literacy bridges]. Kavala: Saita.

Doyle, M. A. (2019). “Marie M. Clay’s theoretical perspective: a literacy processing theory” in Theoretical models and processes of literacy. eds. D. E. Alvermann, N. J. Unrau, M. Sailors, and R. B. Ruddell. 7th ed (New York, NY: Routledge), 84–100.

Dyson, A. H. (1986). Transitions and tensions: interrelationships between the drawing, talking, and dictating of young children. Res. Teach. Engl. 20, 379–409. doi: 10.58680/rte198615598

Efland, A. (2004). The arts and the creation of mind: Eisner's contributions to the arts in education. J. Aesthetic Educ. 38, 71–80. doi: 10.2307/3527377

Gardner, H. (1980). Artful scribbles: The significance of children's drawings. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2017). Reflections on artful scribbles: the significance of Children’s drawings. Stud. Art Educ. 58, 155–158. doi: 10.1080/00393541.2017.1292388

Hall, E. H. (2020). My rocket: young children’s identity construction through drawing. Int. J. Educ. Arts 21, 1–30. doi: 10.26209/ijea21n28

Hutton, J. S., DeWitt, T., Hoffman, L., Horowitz-Kraus, T., and Klass, P. (2021). Development of an eco-biodevelopmental model of emergent literacy before kindergarten: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 730–741. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.6709

Kennedy, C., and McLoughlin, A. (2023). Developing the emergent literacy skills of English language learners through dialogic Reading: a systematic review. Early Childhood Educ. J. 51, 317–332. doi: 10.1007/s10643-021-01291-1

Kim, M. S. (2018). Learning-by-designing literacy-based concept-oriented play (LBCOP) activities: emergent curriculum for/with young CLD children and their teacher. Interact. Learn. Environ. 27, 256–271. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2018.1460615

Labbo, L. D., and Teale, W. H. (2013). “An emergent-literacy perspective on reading instruction in kindergarten” in Instructional models in reading. eds. S. A. Stahl and D. A. Hayes (New York, NY: Routledge), 249–281.

Lenhart, J., Suggate, S. P., and Lenhart, W. (2021). Shared-Reading onset and emergent literacy development. Early Educ. Dev. 33, 589–607. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2021.1915651

Manolitsis, G. (2016). Ο αναδυόμενος γραμματισμός στην προσχολική εκπαίδευση: Νέα ζητήματα και εκπαιδευτικές προτάσεις. [Emergent literacy in early childhood education: New issues and educational proposals]. Preschool Primary Educ. Laboratory of Pedagogical Research & Applications. 4, 3–34.

Neumann, M. M. (2022). What counts Most in assessing emergent literacy with digital tools? Child. Educ. 98, 72–77. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2022.2020556

Piaget, J. (1985). The equilibration of cognitive structures. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Puranik, C. S., and Lonigan, C. J. (2012). Early writing deficits in preschoolers with oral language difficulties. J. Learn. Disabil. 45, 179–190. doi: 10.1177/0022219411423423

Rhyner, P. M., Haebig, E. K., and West, K. M. (2009). “Understanding frameworks for the emergent literacy stage” in Emergent literacy and language development. Promoting learning in early childhood. ed. P. M. Rhyner (New York: Guilford), 5–35.

Rieber, R. W. (2012). The collected works of LS Vygotsky: Scientific legacy. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Rodosthenous, M., Stylianou-Georgiou, A., and Pitri, E. (2019). A case study on the production of multimodal texts in secondary education. Punctum. Int. J. Semiotics 5, 216–234.

Sandvik, J. M., van Daal, V., and Adèr, H. J. (2014). Emergent literacy: preschool teachers’ beliefs and practices. J. Early Child. Lit. 14, 28–52. doi: 10.1177/1468798413478026

Sidelnick, M. A., and Svoboda, M. L. (2000). The bridge between drawing and writing: Hannah's story. Read. Teach. 54, 174–184.

Sperry, L. L., and Sperry, D. E. (2021). Entering into the story: implications for emergent literacy. Front. Psychol. 12:665092. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.665092

Tsikalaki, Ε. (2005). Η εξέλιξη του παιδικού σχεδίου και οι προκύπτουσες παιδαγωγικές αρχές για τη διδασκαλία του μαθήματος της αισθητικής αγωγής [the development of children's drawing and the resulting pedagogical principles for teaching the subject of aesthetic education]. Educ. Sci. 4, 201–218.

Weadman, T., Serry, T., and Snow, P. C. (2023). The Oral language and emergent literacy skills of preschoolers: early childhood Teachers' self-reported role, knowledge and confidence. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 58, 154–168. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12777

Yiannikopoulou, A. (2002). Η γραπτή γλώσσα στο νηπιαγωγείο. [Written language at the preschool]. Athens: Kastaniotis.

Keywords: visual expression, narrative drawing, emergent literacy, early childhood education, multimodal meaning making

Citation: Pitri E and Michaelidou A (2025) The contribution of narrative drawing in early literacy. Front. Educ. 10:1465714. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1465714

Received: 16 July 2024; Accepted: 03 February 2025;

Published: 12 February 2025.

Edited by:

Jihea Maddamsetti, Old Dominion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaCopyright © 2025 Pitri and Michaelidou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eliza Pitri, cGl0cmkuZUB1bmljLmFjLmN5

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.