94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 05 March 2025

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 10 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1435836

This article is part of the Research TopicSituating Equity at the Center of Continuous Improvement in EducationView all 8 articles

Introduction: Research-practice partnerships (RPPs) are posited as a vehicle to improve the use of research evidence. Equity-centered RPPs are an evolving subset of RPPs loosely bound by equity principles and varying in partnership design and approaches. There is a need for a better understanding of the partnership dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs, as well as whether and how equity-centered RPPs improve youth outcomes.

Methods: We leverage the growing literature on the use of research evidence, RPPs, and improvement research to provide an interdisciplinary framework that connects the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs to proximal and distal outcomes.

Results: We argue that equity-centered RPPs are RPPs that center race and racism in their composition, goals and approaches to research. Explicitly attending to race and power in partnership dynamics and activities, centering children marginalized by oppression, and embracing historical perspectives are hallmarks of equity-centered RPPs. By first attending to equitable processes (i.e., dynamics and activities), equity-centered RPPs create the conditions for equitable outcomes – for RPP participants and the students and schools they serve. We posit that the theory of racialized organizations centers the role of race in partnership dynamics, activities and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs and social design experiments capture the disposition of equity-centered RPPs of advancing equity through learning via the production and use of research evidence.

Discussion: We conclude with a discussion of how this theory of action can be useful for those participating in and studying equity-centered RPPs.

Equity is increasingly being discussed in K-12 education and the work of research-practice partnerships (RPPs) in the U.S. But what is equity? How do we manifest equity in our partnership work? And more importantly, how does our commitment to equity translate into an improvement in youth outcomes? In the pendulum swings in the racial climate since the murder of George Floyd, equity came to dominate the parlance of practitioners, policymakers, and scholars. Consensus on what equity means and the exact nature of equitable policies and practices remain elusive (Bulkley, 2013; Castro, 2015; Najarro, 2022; Sawchuk, 2022; Unterhalter, 2009). In one breath, equity is equal distribution of inputs; in another breath, it evolves into meeting students where they are and giving them what they need (Alemán, 2006; Bulkley, 2013). Yet in another gasp, equity captures the panacea to the myriad afflictions and maladies in the K-12 education system. Similar to urban and rural education (Welsh, 2024; Welsh and Swain, 2020), accompanying the absence of a universal definition (the definitional gap of educational equity) has been unresolved questions about how equity is measured (the assessment gap of educational equity). The definition and conceptualization of equity has important implications for not only K-12 education but also the work and outcomes of RPPs, especially as RPPs employ continuous improvement principles and methodologies to advance equity.

For this study, we understand equity as both a process and an outcome. Equity is being achieved when identity does not predict students’ experiences or outcomes, and structural and systemic barriers that have historically disproportionately harmed students of color are removed (Bensimon, 2018). Disrupting racial inequities in education is a complex and arduous task because of race and power dynamics and Whiteness structures (Grace and Lastrapes, 2024; Swanson and Welton, 2019). Tseng (2024) highlighted that “current systems for producing and using research are mired—as are all U.S. institutions—in a long history of racism, xenophobia, and a culture of paternalism.” (p.19). Equity is an emphasis on transforming structures to reduce differences in youth outcomes.

RPPs are defined as “long-term collaboration[s] aimed at educational improvement or equitable transformation through engagement with research” (Farrell et al., 2021, p. 5). The theory of action underlying RPPs as vehicles for improvement or transformation relies on improving the conditions for the use of research evidence by education decisionmakers (Farrell et al., 2021; Finnigan, 2023; Penuel and Watkins, 2019; Tseng et al., 2017; Welsh, 2021; Wentworth et al., 2017). RPPs are “a promising strategy for producing more relevant research, improving the use of research evidence in decision making, and engaging both researchers and practitioners to tackle problems of practice” (NNERPP, n.d.) Equity-centered RPPs have emerged as an evolving subset of RPPs, loosely bound by equity principles and varying in partnership design and approaches (Doucet, 2021; Farrell et al., 2021, 2022; Henrick et al., 2019; Penuel et al., 2017; Vetter et al., 2022; Welsh, 2021). Prior research has emphasized the potential of RPPs to pursue work which could potentially advance equity but noted that without explicit conceptualizations and operationalizations of equity, “such work can unintentionally maintain the status quo and further marginalize students and communities” (Vetter et al., 2022, p. 841). Some scholars have argued that RPPs lack an explicit focus on equity and do not center issues of race, culture, class, and power that underlie educational inequities (Gutiérrez and Jurow, 2016). Diamond (2021) contended that “RPPs are an organizational approach and not an equity strategy.” (p.1). Tseng (2017) emphasized the need to refine the theories of action governing partnership work. Skeptics of RPPs posit that “most RPPs were oriented toward process rather than outcomes” (Schneider, 2020). This necessitates a richer understanding of not only the process of RPPs (proximal outcomes) but the complex and multifaceted ways in which the process results in products that improve K-12 education (distal outcomes). Without a theoretical and conceptual grounding, the activities, dynamics and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs may proclaim equity but not manifest in improvements in youth outcomes, especially for traditionally marginalized students (Tseng, 2024).

In this study, we leverage the growing literature on the use of research evidence, RPPs, and improvement research to provide an interdisciplinary framework that connects the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs to proximal and distal outcomes. We add to the conceptualization of an equity-centered RPP and provide a pathway for how the process of partnering and the use of research evidence translates into the reduction of disparities in youth outcomes. The framework presented was iterative and the foundations were co-constructed by researchers and practitioners working together in an equity-centered RPP with a singular goal of reducing disparities in students’ disciplinary outcomes. The theory of action was developed over multiple conversations between the lead researcher and lead district partners over 7 years. It was shared with additional members of the RPP leadership and research team members and iterated based on feedback. Overall, the theory of action is informed not only by a synthesis of the literature, but also by our collective experiences as participants in multiple RPPs, former teachers and school leaders, and researchers studying the use of research evidence and equity phenomena such as school discipline. This framework is being used by the equity-centered RPP to develop a shared understanding of the goals of the work and guide decision-making, as well as a research team studying how equity-centered RPPs can foster conditions to use research evidence.

A theory of action for equity-centered RPPs can provide a useful starting point as equity-centered RPPs are developed, expanded, and studied. Although there have been prior literature reviews (Vetter et al., 2022) and insightful articles on the definition and work of equity-centered RPPs (Farrell et al., 2022), our review of the literature could not surface a comprehensive theory of action that links the process of equity-centered RPPs to the products of equity-centered RPPs. This study responds to Farrell et al.’s (2023) call for research that interrogates the relationship between RPPs’ conceptualization of equity, internal processes and practices, and products and outcomes. As equity-centered RPPs sustain and expand their operations, there is a need for theory-building in the study and practice of equity-centered RPPs, a deeper understanding of the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs, and research to show whether and how equity-centered RPPs can lead to improvements in equitable outcomes for students. The framework contributes to the nascent literature on the theorization about the work and outcomes of RPPs in general and equity-centered RPPs, and the knowledge base on RPPs and the use of research evidence in decision making in K-12 education (Arce-Trigatti et al., 2018; Farrell et al., 2019; Henrick et al., 2023; Penuel et al., 2018; Welsh, 2021). Coburn and Penuel (2016) found that research on partnership dynamics within RPPs “tends to focus on the challenges, providing little insight into how partnership designs and strategies used by participants can address these challenges” (p. 48) and—more significantly—does not examine relationships between partnership dynamics and partnership outcomes. Accordingly, we not only draw on existing definitions of partnership dynamics but extend dynamics forward into their implications for RPP activities and outcomes. These linkages are suggested, but not explicitly theorized, by descriptions of equity-focused RPP work such as Diem et al. (2024), in which RPP participants directly attend to ways whiteness infiltrates partnership work (i.e., dynamics), counter normative relationships with an antiracist decision-making protocol (i.e., activities), and identify racially biased policies and practices (i.e., proximal outcomes) in pursuit of more equitable school behavior policies (i.e., distal outcomes).

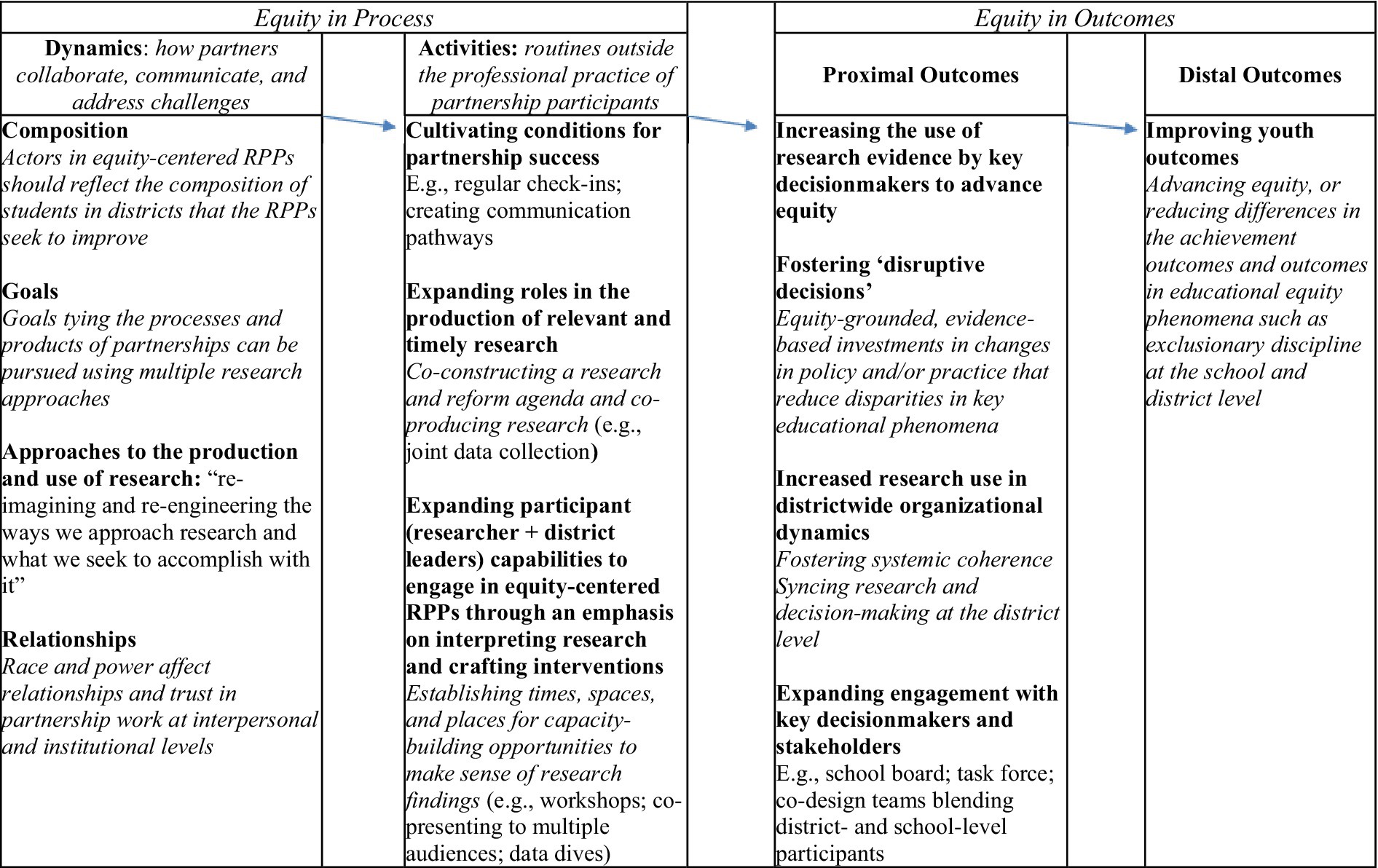

Figure 1 provides a guiding conceptual framework of how equity-centered RPPs may improve youth outcomes. The framework outlines the elements and connections among partnership dynamics, partnership activities, and the proximal and distal outcomes of equity-centered RPPs. Equity in RPP dynamics—organizational norms and routines which disrupt normative power differentials (Diamond and Gomez, 2023)—lay the foundation for RPP activities that continuously affirm the knowledge, experiences, and contributions of historically marginalized RPP constituents. As Figure 1 illustrates, involvement with RPP activities has effects on each participant individually and institutionally (proximal outcomes), which in turn have positive impacts on student achievement, student and staff experiences, and advancing educational equity (distal outcomes). We emphasize that there is no single agreed-upon definition of equity-centered RPPs. We distinguish equity-centered RPPs by their wholesale attention to race, racism, and power. We argue that first attending to equitable processes (i.e., dynamics and activities) creates the conditions for equitable outcomes—for RPP participants and the students and schools they serve. Equity in youth outcomes is undergirded by equity in the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs. We posit that racialized organizations theory centers the role of race in partnership dynamics, activities and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs and social design experiments capture the disposition of equity-centered RPPs of advancing equity through learning via the production and use of research evidence. We contend that disruptive decisions are the connective tissue between the use of research evidence and improvement in youth outcomes.

Figure 1. Equity-centered RPPs and the use of research evidence to advance equity: theory of action. Bolded theory of change elements are discussed below. Italicized text provides brief definitions. Roman text provides examples.

In what follows, we first provide a brief review of the growing literature on equity-centered RPPs. Following this, we provide a definition of equity-centered RPPs and posit a theoretical framing for the theory of action. Next, we discuss the components of Figure 1 from the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs to the proximal and distal outcomes of equity-centered RPPs. We conclude with a discussion of how this theory of action can be useful for those participating in and studying equity-centered RPPs.

There are relatively few empirical studies of equity-centered RPPs that document what equity-centered RPPs are in practice, how they function, and how the functioning of equity-centered RPPs may improve the use of research evidence and disrupt inequities in students’ outcomes (Farrell et al., 2021, 2023; Vetter et al., 2022). Although a growing number of studies have considered the distinguishing features of equity-centered RPPs (Farrell et al., 2021, 2023; Vetter et al., 2022; Welsh, 2021), there is no universal definition of equity-centered RPPs. Farrell et al. (2023) broadly conceive of equity-centered RPPs as pursuing equity in the process of partnering or in the work (i.e., desired outcomes) addressed by the partnership. The five dimensions of equity-focused RPPs posited by Vetter et al. (2022)—theoretical frameworks for understanding equity and justice, explicit connection to equity and justice in the purpose of the research, clearly defining equity and justice within the RPP, use of methods/designs which advance equity and justice, and contribution to equity and justice—span Farrell et al.’s (2023) conceptual dichotomy. Tseng (2024) shared three design principles to ensure that RPPs are equity-driven: centering children marginalized by oppression, embracing historical contexts and legacies of inequities, and contending with power dynamics to foster equitable collaborations.

How RPPs conceptualize and operationalize equity has “consequences for what gets studied, whose voices are included, how resources are distributed, and what and whose knowledge is foregrounded in partnership activity” (Farrell et al., 2023, p. 201). Research has highlighted that diverse partners within RPPs invoke varying understandings of equity (Farrell et al., 2021, 2023; Vetter et al., 2022). Supplee et al. (2023) similarly emphasized the primacy of creating a “shared understanding of what it means to have equity for participants.” Questions of whose voices are included and what knowledge is foregrounded shape the internal processes of RPPs and the objects of RPP work (Supplee et al., 2023).

Farrell et al. (2023) categorized equity in products as addressing one of three main topics: achievement and standardization; identity, culture, and belonging; or power, justice, and anti-racism. Farrell et al. identified systematic variation in how RPP members operationalized their conceptualization of equity, in accordance with the domain of focus. For example, RPPs with a focus on achievement and standardization often engaged in deficit or neutral orientations towards target groups, whereas RPPs with goals around identity, culture, and belonging took an asset orientation. These linkages support explicitly centering and studying the relationship between equitable processes within RPPs and equitable experiences and outcomes for students and staff.

How equity is discussed in the RPP literature has evolved and increased over time. Scholars have highlighted that some RPPs demonstrate more complex equity logics for outcomes than for process, or vice versa, with other RPPs lacking any equity focus at all (Farrell et al., 2023; Gutiérrez and Jurow, 2016). Notwithstanding, the field’s growing attention to equity can be seen in the 2023 revision of the 2017 RPP effectiveness framework. This revision to the framework included explicit attention to equity, voice, privilege, and power across all dimensions and indicators. This emphasis can be seen, for example, in attention to the “meaningful inclusion of voices of students, families, and communities and the ways in which power dynamics unfold within partnership work” (Henrick et al., 2023, p. 4). Considering equity in both products and processes is integral.

In addition to the dimensions of variation—goals, composition, approaches to research—posited by Farrell et al. (2021), we posit that attention to race and racism is a defining feature of equity-centered RPPs. Equity-centered RPPs are RPPs that center race and racism in their composition, partnership goals and approaches to research. Explicitly attending to race and power in partnership dynamics and activities, centering children marginalized by oppression, and embracing historical perspectives are hallmarks of equity-centered RPPs (Tseng, 2024). One of the distinctive features of equity-centered RPPs is that critical perspectives are not added in but are a part of the DNA of these partnerships, shaping processes and outcomes. Critical perspectives in partnership work are needed for understanding the topic and transforming the problem of practice. Equity-centered RPPs infuse criticality in each of the dimensions discussed by Farrell et al. (2021), with specific attention to race and racism.

This definition of equity-centered RPPs builds on Farrell et al.’s (2021) definition and encapsulates Tseng’s (2024) three design principles for RPPs. That is, race and power are made visible and explicitly considered when centering historically marginalized children and youth and attending to equity in RPP goals, composition, and approaches. By adding attention to power dynamics and relationships, this definition elevates how equity can be present in not only the products and outcomes of an RPP, but also the internal processes (dynamics and activities) of partnership. Prior scholars have highlighted the importance of studying the researcher-practitioner relationship in order to better understand the outcomes and processes of collaborative work (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Tseng et al., 2017; Vakil et al., 2016). A focus on the process of partnering necessitates “attention to the genesis of a practice” (Gutiérrez and Vossoughi, 2010, p. 1010) and consideration of “the dynamics of invisibility and critical reflexivity” with particular focus on the impact of positionality and power, normative roles of researcher vs. the researched, barriers to access to all parts of the research process, choices being made on research collection and methods, and barriers to collaboration (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016, p. 176).

RPPs have been criticized for lacking an explicit focus on equity and not centering issues of race, culture, class, and power that underlie educational inequities (Ahn et al., 2024; Gutiérrez and Jurow, 2016). Scholars have noted that in instances where RPPs orient themselves to racially equitable outcomes and products, other aspects of equity are missed, such as underlying racial and power dynamics in the partnerships or educational systems themselves (Ahn et al., 2024; Diamond, 2021; Farrell et al., 2023). Vetter et al. (2022) found that only 17 of the 149 RPPs included in their thematic review merit the label “equity-focused,” as evinced through explicitly and effectively defining and addressing power and privilege in how RPPs conceptualize communities, RPP structures, and targeted outcomes. Vetter et al. (2022) distinguished between equity-adjacent RPPs and equity-focused RPPs: equity-focused RPPs explicitly address power and privilege within both the RPP itself and the larger educational context, in contrast with RPPs which do not explicitly attend to equity and social justice. Ahn et al. (2024) underscored that “Although many RPPs may state a focus on redressing racial inequity or injustice, few RPPs work from explicit frameworks that center race as a concept or engage critically with the racialized experiences of partners or learners” (p.298).

Equity-centered RPPs are rooted in the tradition of scholars such as Carter G. Woodson, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Gloria Ladson-Billings who use race as a central theoretical lens to understand inequality in schools. Equity-centered RPPs are defined not only by “building from racialized understanding of student and educator experiences” (Ahn et al., 2024; p. 295) but also operationalizing a racialized understanding of the process of partnering. The race and positionality of members of partnership are often overlooked dimensions of RPPs. Equity-centered RPPs center race and positionality (Ahn et al., 2024; Milner, 2007; Tanksley and Estrada, 2022) given that individual racialized understandings will undoubtedly shape collective dynamics, activities, and outcomes of RPPs. As such, equity-centered RPPs are not only confronting the structural racism that pervades schooling in the U.S (Ahn et al., 2024; Sobti and Welsh, 2023; Welsh et al., 2019), but addressing issues of bureaucratic representation in the composition of RPPs and racism in how partnership participants work to catalyze continuous improvement in K-12 education (Welsh, 2021; Doucet, 2021; Ishimaru et al., 2022; Tanksley and Estrada, 2022). Those engaging in equity-centered RPPs must situate race as “a master category that constantly structures our society via our interpersonal and institutional interactions and practices even as the realizations and realities of race shift over time. (Vakil et al., 2016 p.198)” Given how race and power dynamics are embedded in educational organizations, Diamond and Gomez (2023) suggest that institutionalizing disruptive routines is a core means by which to deconstruct anti-Black racism in education. Equity-centered RPPs are but one means through which to respond to this call.

To be clear, there are many theories that can be applied to the operations and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs. Scholars have advanced organizational theory (Arce-Trigatti et al., 2018), institutional theory (Farrell et al., 2023), and complexity theory (Welsh, 2021) as conceptual frameworks for understanding and organizing the inherent messiness of partnership work. We contend that racialized organizations theory and social design experiment are useful as frameworks for the theory of action presented in this study. We draw on racialized organization theory as our primary critical theory for centering race in both the process and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs. RPPs are racialized organizations and the participants in RPPs hail from and work in racialized organizations whether non-profits, universities, or district central offices. This focus on race, power, and racialized power dynamics is congruent with the definition of equity-centered RPPs and the understanding of schools, districts, and RPPs themselves as racialized organizations. Social design experiment (SDE) captures the centrality of learning to the functioning and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs, especially as RPPs utilize design principles to study and address complex social issues, involving the co-creation and testing of interventions within real-world settings to understand their impact on social dynamics and communities. We invite equity-centered RPP participants and researchers to leverage a variety of critical and critical race theories to interrogate the aim and actions of equity-centered RPPs and link the work of RPPs to the educational equity phenomena they study and seek to improve (e.g., Little and Welsh, 2022; Sobti and Welsh, 2023).

Ray (2019) argued that organizations are racial structures and that race shapes resources, opportunities, social status, processes and procedures within the organization. In racialized organizations, whiteness is viewed as a credential. Prior studies have documented how a premium on “collegiality” in RPPs can serve to protect whiteness (Tanksley and Estrada, 2022; Villavicencio et al., 2023). Whiteness as a credential may also manifest in norms and practices that position white researchers as experts and prioritize certain types of research and expertise. Prior studies have used racialized organizations in examining RPPs or highlighted the need for the application of racialized organizations to the work of RPPs (Diamond, 2021; Denner et al., 2019; Farrell et al., 2021; Oyewole et al., 2023; Villavicencio et al., 2023; Welsh, 2021). Racialized organizations theory provides a critical lens to analyze the inequities that emerge from policies and structures that often appear race-neutral and legitimate but are often disparate in application. Racialized organizations theory is useful to RPP dynamics as well as where and how racialized credentialing exists within the RPP and district context. Racialized organizations theory can inform not only the partnership process, but also the products of RPPs. Examining the decoupling of formal rules from organizational practices at the RPP-, district-and school-level offers a valuable lens to shape our thinking and analysis of race and power dynamics among key decisionmakers who may share the same race.

Applying racialized organizations theory also enables researchers to interrogate the multiple layers and intersections of boundaries which contextualize district decision-making—such as researcher, practitioner, or community member; racial and ethnic groups; or class (Penuel et al., 2015)—with a focus on how boundary negotiation shapes not only the racial group agency of district decisionmakers, but ultimately that of teachers and students. Researchers may apply racialized organizations theory to understand unequal allocation of resources in the personnel and programs devoted to reducing inequality in achievement and equity outcomes. Racialized organization theory may be used to examine how equity-centered RPPs recognize the prevalence of anti-blackness in K-12 education (Sobti and Welsh, 2023) and center the agency of students in reform conversations (e.g., how conversations highlight the role of students versus educators in the contributors and solutions to racial inequality in K-12 education).

Social design experiments are “cultural historical formations designed to promote transformative learning for adults and children” and provide opportunities for reflection and examination of informal theories based on participants’ lived partnership experiences (Gutiérrez and Vossoughi, 2010 p.100). SDE’s “explicit focus on disrupting educational, structural, and historical inequities through the design of transformative learning activity provides openings for learning, a context of critique for resisting and challenging the conditions that create and sustain inequities, and a space for generating their possible solutions” (Gutiérrez and Jurow, 2016, p.4). Similar to equity-centered RPPs, social design experiments are dynamic, rife with disruptions and revisions, and are co-designed (Gutiérrez and Vossoughi, 2010; Welsh, 2021). Social design experiments conceptualize research as an intervention for historical injustice that works toward more just futures and provides a lens to create and study change (Gutiérrez and Vossoughi, 2010; Gutiérrez, 2016). Social design experiments recognize the expertise and knowledge found in communities.

The approach of social design experiment aligns well with the complexity and disposition of partnership work in equity-centered RPPs. Research use, partnership work, and district and school practices are complex, nuanced, and can be framed as learning processes (Farrell et al., 2022; Honig et al., 2017; Tseng, 2022; Welsh, 2021; Welsh et al., 2021). Individual learning in partnership work is connected to transformation of K-12 education in schools and districts. Social design experiment as an analytic tool uses various artifacts to facilitate and promote reflection among the partnership participants with an emphasis on documenting and tracing the process of partnering and the use of research evidence for understanding how the exchange these phenomena. Reflexivity, participatory approaches, and a critical orientation are all essential ingredients in the study of equity-centered RPPs in order to reveal the layers of race and power in the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs (Coburn et al, 2008; Drame and Irby, 2015; Holmes, 2020).

Figure 1 links the dynamics and activities of equity-centered RPPs to proximal and distal outcomes. Proximal outcomes capture how partnership activities shape the participants in an RPP and local decision-making whereas distal outcomes capture how RPPs affect students in the K-12 education system (who are typically not active participants in partnership activities). We situate RPPs as mutually beneficial and a two-way street for learning for participants: (a) research to practice in the use of research evidence and (b) practice to research in the expansion of researchers’ capabilities. As such, all RPP members experience proximal outcomes of deepening their engagement with diverse ways of knowing and their understanding of equity-oriented research and practices as well as increasing their capacity to engage in equity-centered partnership work. On the researcher side, proximal capacity-building outcomes at the individual level include researchers’ capabilities for engaging in partnership work such as understanding educational issues, applying learning, presenting and communicating research findings, and understanding their identity as a researcher. On the practitioner side, proximal outcomes at the individual-level include using research evidence in district and school leaders’ decisions and practice. At the institutional level, RPPs may shape the organization and ethos of departments and universities (Gamoran, 2023) or at the institutional level, shaping organizational dynamics such as the district’s norms, culture, and routines around the use of research and other evidence (Henrick et al., 2017).

RPP dynamics refer to the interpersonal, organizational, and structural factors that shape the functioning and success of RPPs. These dynamics influence how partners collaborate, communicate, and address challenges. Partnership dynamics refer to how RPP members work together, the characteristics of the relationship between partners, and the dispositions and stance of partners that shape how they work and navigate boundaries (Penuel et al., 2015). Denner et al. (2019) examined the role of culture and power in the construction and evolution of the RPP and found that over time, the dynamics of the RPP become just as important as the “findings” produced.

There are four core elements of the dynamics of equity-centered RPPs: (1) determining RPP composition, (2) developing RPP goals, (3) deciding upon research approaches, and (4) developing relationships.

In his fireside chat in July 2024, interim director of IES Mark Soldner addressed RPP composition. He implored participants at the 2024 NNERPP forum to create expansive, cross-sector research-practice partnerships that include a broad swath of educational constituents beyond researchers and practitioners. He raised concerns about who is not typically at the “RPP table”—students, parents, community-based organizations—and encouraged an expansion of who is involved to build capacity to collaborate across sectors. Scholars such as Kris Guitierrez have noted the importance of researcher and participant diversity in developing a new ecology such as equity-centered RPPs (Gutiérrez, 2016). Henrick et al. (2023) highlighted that meaningfully including diverse constituent groups and building the partnership around voices speaking from multiple vantage points requires attending to power and privilege dynamics in order to create equitable partnership contexts. Welsh (2021) argued that equity-centered RPPs aiming to disrupt inequities in education should engage multiple practitioner constituents from school board members to district leaders, principals, and assistant principals. Vetter et al. (2022) outlined how equity-centered RPPs can include students as decisionmakers, researchers, and valued partners within RPPs. Relevant diverse perspectives should be included in all aspects of partnership work: when structuring the partnership, developing research questions, conducting research, revising partnership goals, and sharing new knowledge (Krishnan et al., 2024; Supplee et al., 2023; Teeters and Jurow, 2022).

Can an equity-centered RPP in a majority-Black district be composed of majority-White participants? This is the operative question bedeviling several RPPs claiming to be equity-centered RPPs. Applying the bureaucratic representation lens (Nicholson-Crotty et al., 2011), the diversity of actors in equity-centered RPPs should reflect the composition of students in districts that the RPPs seek to improve. Equity-centered RPPs may be defined by shared racial identity among participants in the partnership (Vakil et al., 2016). The solidarity extends beyond representational diversity into the link between the personal histories of participants and the values, goals, and processes of partnering (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Vakil et al., 2016). Shared racial identity between researchers and practitioners bodes well for developing the politicized trust for partnership work—yet even with shared racial identity, details about the roles and processes of working together are salient considerations in collaborative work (Vakil et al., 2016).

Even in cases where the key actors in the equity-centered RPP may share the same race, this does not preclude inequitable race and power dynamics in partnership activities or among decision makers. Participating in an equity-centered RPP requires positionality-dependent work. White researchers and educators’ efforts to disrupt anti-Blackness should be cognizant of their interpersonal and institutional positioning (Hytten and Stemhagen, 2023). For example, frank conversations about race and power among partnership participants in an equity-centered RPP may contribute to sustained politicized trust which, in turn, creates open and honest forums for the discussion of inequality in racialized topics such as discipline and behavior. This may strengthen the alignment between the contributors to disparities and interventions (Teeters and Jurow, 2022; Welsh and Little, 2018; Welsh, 2023).

Equity-centered RPPs ought to tackle the central challenge in US education—inequality in education (Farrell et al., 2021; Gamoran and Bruch, 2017; Tseng, 2024)—and transform schools by centering the reduction of disparities in K-12 education. Equity across race, gender, power, sexuality, and ability is central in both the process of partnering and the intended student and school outcomes of equity-centered RPPs (Farrell et al., 2021). As Bang and Vossoughi (2016) advocated for in their work with Participatory Design Research (PDR), equity-centered RPPs are tasked with analyzing the participatory process itself as an object of study to accurately and comprehensively engage in collective knowledge construction. These paired goals—which tie the processes and products of partnerships—can be pursued using multiple research and partnership approaches, including design-based implementation research (O’Neill, 2018; Penuel, 2019; Penuel et al., 2022) and networked improvement communities (Noble et al., 2021).

Given the attention to race and power in the DNA of equity-centered RPPs, one of the aims of equity-centered RPPs is to produce and use antiracist research (Doucet, 2021; Tseng, 2024). Doucet (2021) defines antiracist research as race-and racism-conscious, strengths-based, humanizing, co-constructed, and community-centered. Engaging in inclusive research or inquiry to address local needs; supporting the practice or community organization in making progress on its goals; engaging with the broader field to improve educational practices, systems, and inquiry; and fostering ongoing learning and develop infrastructure for partnering are all possible goals of equity-centered RPPs. (Henrick et al., 2023).

Doucet (2019) argued that the approach to research in equity-centered RPPs must seek to communicate the lived experiences of marginalized groups in K-12 education in community-uplifting ways. In particular, research “1. must take into account the intercentricity of race and racism with other forms of subordination, 2. challenge dominant ideologies, 3. have a commitment to social justice, 4. center experiential knowledge and insist people of color have legitimate expertise, 5. utilize transdisciplinary approaches” (Doucet, 2019, pg. 5–6). This aligns with Doucet’s (2021) definition of antiracist research. As Orellana and Gutiérrez (2006) noted “We need to think carefully about the problems we name. Whose problem is it? For whom is it a problem? What other problems might we identify if we began from different vantage points” (p. 118). These approaches are the antithesis of feeding into “damage-centered” or deficit research (Supplee et al., 2023; Tuck, 2009; Okamoto, 2024). Hytten and Stemhagen (2023) offered renarrativizing—“engaging with history in ways that can generate hope and provide resources for action” (p. 5)—as a means by which to dismantle deficit, anti-Black racism in education. Equity-centered RPPs are committed to producing and using what Pasque et al. (2022) term “unapologetic education research.”

Equity-centered RPPs ought to be at the vanguard of “re-imagining and re-engineering the ways we approach research and what we seek to accomplish with it” (Tseng, 2024, p.19). Research in equity-centered RPPs aiming to advance equity can draw on multiple research approaches, including design-based implementation research (O’Neill, 2018; Penuel, 2019; Penuel et al., 2022), networked improvement communities (Noble et al., 2021), and Participatory Design Research (PDR) (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016). Equity-centered RPPs do not inherently need to prioritize a particular methodology or research approach, but they do reject a dominant objective, colorblind, quantitative-centric approach that privileges a particular type of knowledge and does not provide “an historicized understanding of the ecology, its resources, and constraints” (Gutiérrez, 2016, p. 192). A defining feature of equity-centered RPPs is valuing the multitude of ways of knowing practitioners and community members bring to joint work (Archibald, 2008; Henrick et al., 2023; Tachine and Nicolazzo, 2023).

Drawing on the insights of Gutiérrez and Vossoughi (2010), improving the use of research evidence relates to how RPP members think about the use of research evidence. This extends the pertinent questions about the use of research evidence from the how and what to the why, who, and for whom research is used (Kirkland, 2019). The use of research evidence plays an important role in constructing race and is constructed by race (Doucet, 2021; Kirkland, 2019). Research evidence has been misused to sustain racial hierarchies and promote anti-blackness (Diamond, 2021; Doucet, 2019; Kirkland, 2019). Kirkland (2019) argued that the use of research evidence is a “system of power” and not a neutral act. Scholars have highlighted the importance of shared power in co-constructing the research agenda (Tseng et al., 2017). Placing data in racial and historical context is pivotal to the use of research evidence in equity-centered RPPs (Kirkland, 2019). Given the ways in which race and racism shape dominant ideas of expertise and authority, researchers’ capabilities, and participants’ dignity and contributions to creating knowledge, equity-centered RPPs can heed Hytten and Stemhagen’s (2023) call to revalue Black people in the United States by instituting routines, practices, and habits which center Black people.

Equity-centered RPPs also ensure attention to race, racism, and power in cultivating trust and relationships. Relationships are a key ingredient in the use of research evidence (Tseng, 2022; Tseng et al., 2017). Challenges in the use of research evidence are not an information problem given that the use of research evidence is relational rather than translational (Dumont, 2019; Penuel et al., 2015). Relationships are also an essential component of partnership work and are one of the critical avenues through which decisionmakers acquire and understand research (Tseng, 2022; Welsh, 2021). Barton et al. (2014) highlighted the centrality of relationships in RPPs and contend that relationships are the key to success in RPPs, analogous to the importance of location in real estate. Doucet (2021) highlighted the importance of focusing on trusting relationships and their ingredients. Partnering is shaped by critical historicity, race, power, and relationality (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016).

The approach to the use of research evidence in equity-centered RPPs rests on relationships, suggesting that the work of equity-centered RPPs is not solely about generating research but also fostering engagement to facilitate the use of research in decision-making. Race and power shape the relationships and interactions at the core of the process of partnering in equity-centered RPPs and the use of research evidence in district policy deliberation (Huguet et al., 2021; Tseng, 2022; Turner, 2015, 2020; Welsh, 2021). Race and power affect relationships and trust in partnership work at interpersonal and institutional levels (Diamond, 2021; Farrell et al., 2021; Supplee et al., 2023). Race and power interact in complex ways in RPPs between different actors (Denner et al., 2019). Vakil et al. (2016) highlighted the importance of acknowledging the underlying tensions of race and power dynamics in partnerships as partners work to cultivate trust. As such, equity in partnership work requires attention to race and power asymmetries among participants (Diamond, 2021; Doucet, 2019; Henrick et al., 2019).

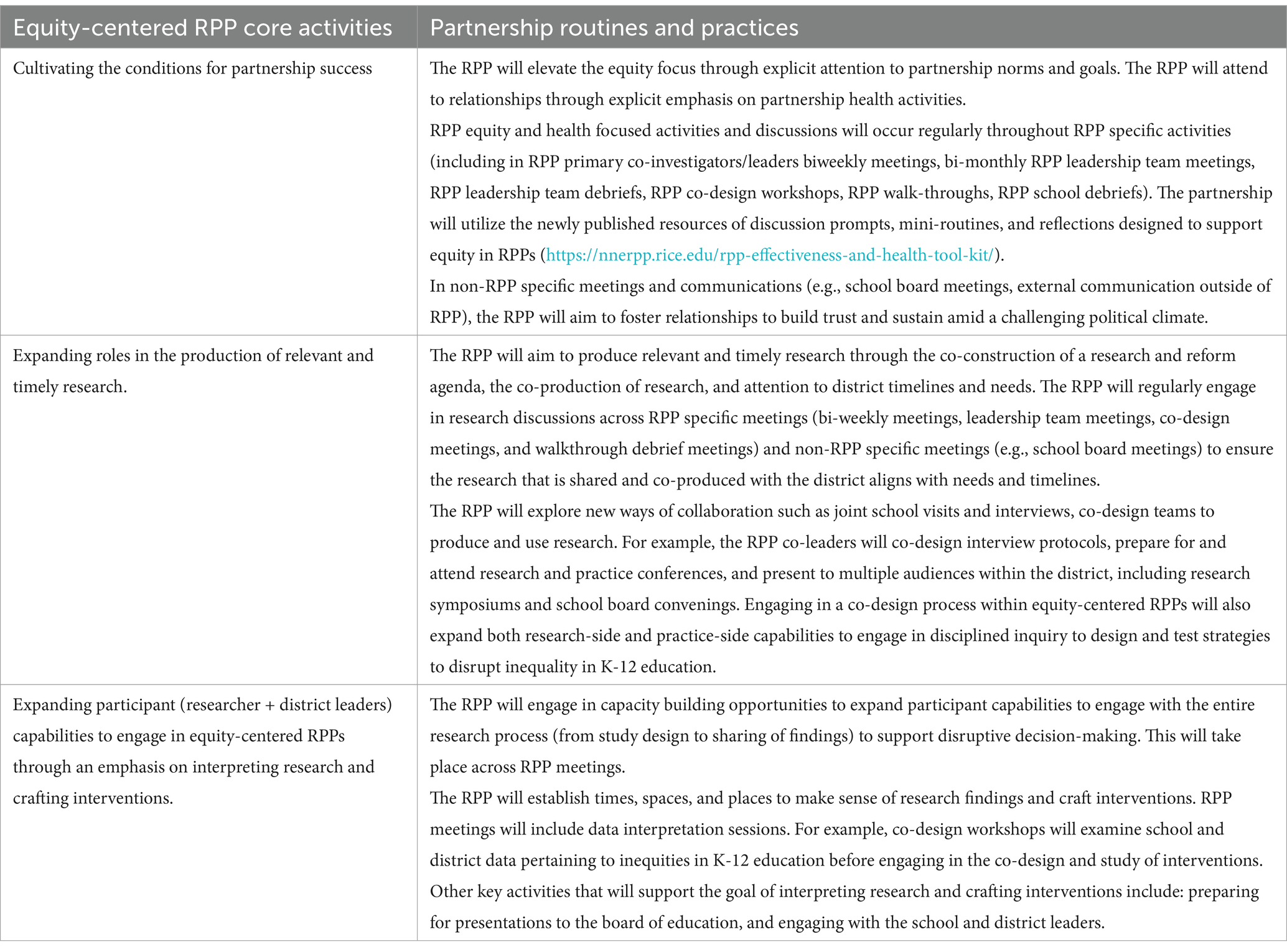

Penuel et al. (2015) posited that RPPs are “joint work at the boundaries.” Boundary practices refer to routines outside the professional practice of partnership participants; boundary crossing captures how differences are perceived and navigated (Penuel et al., 2015). We complement Penuel et al.’s (2015) framework of boundary crossing and practices with Farrell et al.’s (2022) framing of RPPs to operationalize the principles of equity-centered RPPs in partnership activities related to (a) cultivating conditions for partnership success (b) expanding roles in the production of relevant and timely research, and (c) expanding participant (researchers and district leaders) capabilities to engage in equity-centered RPPs through an emphasis on interpreting research and crafting interventions. Intentionality around developing equitable RPP dynamics (described in the earlier section) will contribute to the development of organizational norms and routines which disrupt normative power differentials. Table 1 illustrates the activities of an equity-centered RPP focused on school discipline.

Table 1. Illustrating the activities of equity-centered RPPs: an equity-centered RPP focused on school discipline.

One of the main ways RPP participants work together is cultivating the conditions for partnership success (Farrell et al., 2021). Setting goals and norms for RPP check-ins and working sessions at the outset of partnering proactively fosters the creation and maintenance of equitable processes within the RPP by building structures and routines to reflect on and discuss power and privilege dynamics within the partnership itself. Regular check-ins to discuss partnership and research project progress, formal and informal interactions at district events, and work sessions at the district central office are some of the ways RPPs can cultivate the conditions for partnership success, maintaining their equity focus by enacting routines created at the outset and iterating these routines through RPP member feedback. These check-ins and working sessions provide a venue for the partnership to address not only the desired outcomes of the RPP, but the process of partnership itself through self-evaluation and the use of evidence for improvement (Sherer et al., 2020). Communication pathways are an important component of managing the partnership and fostering capacity (Farrell and Coburn, 2017).

It is well documented that researchers and policymakers have different tempos about the production and use of research (Farrell et al., 2018, 2021; Penuel et al., 2015). This makes the timing and the products of RPPs an operative tension (Farrell et al., 2018; Henrick et al., 2016; Welsh, 2021). Tseng et al. (2017) highlighted the need for democratizing evidence in education and a broader participation of practitioners and communities in defining the research agenda.

Democratizing data collection is an example of role re-mediation in partnership work that can improve the use of research evidence. Doucet (2019) argued that democratizing research production is a strategy to improve the usefulness of research evidence. Joint data collection also creates an avenue for district leaders to interface with school leaders (Coburn and Talbert, 2006) and provides serendipitous and informal opportunities for relationship building (Oliver et al., 2014). As Bang and Vossoughi (2016) highlighted, “while there is growing attention to processes of co-design across researchers and practitioners within DBR, there is often less attention to collaborative processes of data analysis and writing and the new roles, relations and practices such collaboration requires” (p. 174). Co-production of research evidence results in an increase in decisionmakers’ understanding of research evidence and increased use of evidence (Doucet, 2021). Experimentation with boundary spanning practices can take several forms, such as co-developing interview protocols, joint data collection, and sensemaking discussions involving multiple constituent groups.

A significant capacity building exercise in research-practice partnership is “to have the evidence and the opportunities for the people working on the problem to really talk about it, internalize it and understand it” (Coburn et al., 2013, p. 4). Thus, establishing times, spaces, and places to jointly make sense of research findings (e.g., workshops, data dives) and mutual learning opportunities for researchers and practitioners to discuss identified issues and the relevant research is a critical component of building research capacity (Farrell and Coburn, 2017). Equity-centered RPPs can follow in the footsteps of prior partnerships (López Turley and Stevens, 2015) and use research workshops to develop the research capacity of the partnership, especially in the interpretation of the findings of ongoing research within the context of the partnership.

As discussed above, jointly engaging in research work—data collection activities, data analysis, and drawing conclusions—not only improves the relevance of research for practitioner partners, but expands the capacities of both researchers and practitioners. Joint work develops researchers’ capacity to identify and respond to research questions that are highly salient for practitioners, as well as practitioners’ capacities to both apply extant research to their problems of practice and incorporate research insights organically to address ongoing and evolving problems of practice. In addition to jointly collecting data, regularly holding sensemaking meetings, and co-attending conferences, other capacity building activities can include soliciting feedback and guidance from people who have been involved in existing RPPs, such as members of advisory boards.

RPPs are boundary-spanning organizations in which the boundary infrastructure (i.e., the RPP itself) can influence the incorporation of RPP products into district decision-making (Farrell et al., 2022; Penuel et al., 2015; Yamashiro et al., 2023). The outcomes of equity-centered RPPs are shaped by decisions. RPPs may increase the use of research evidence in decision-making (Tseng, 2012) and the theory of action of equity-centered RPPs underlines the importance of decisions by policymakers and practitioners to advance and sustain educational equity. Coburn et al. (2009ab) highlighted that decision-making in school districts “is centrally about interpretation, argumentation, and persuasion” (p. 1116). At its core, equity-centered RPPs fosters bidirectional learning at boundaries (Farrell et al., 2022) to catalyze and inform disruptive decisions. The overarching distal outcome posited by our theory of action is partly facilitated by disruptive decision-making that reduces disparities in educational outcomes.

We understand “disruptive decisions” to be equity-grounded, evidence-based investments in changes in policy and/or practice that reduce disparities in key educational equity phenomena. Decisionmakers can choose decisions that hinder the advancement of equity, but these are not disruptive decisions as we define them. Sinclair and Brooks (2024) describe the power of “critical moments” during policy development when decisionmakers set or maintain trajectories which either advance equity or preserve inequitable status quos; we refer to decisions that propel trajectories which advance equity as disruptive decisions. Disruptive decisions are the connective tissues between the use of research evidence and improvement in youth outcomes in equity-centered RPPs.

Disruptive decisions are facilitated by research evidence that is relevant, responsive, and relational (Yanovitzky and Weber, 2020). People have a higher likelihood of using research evidence that is responsive, routinized, and relational (Yanovitzky and Weber, 2020). Relevant research (attuned to the urgent needs of the district) increases the likelihood of research being used in local decision-making (Farrell et al., 2022; Huguet et al., 2021). Useful research evidence must also be routinized in that it must be integrated into existing routines within the organization. Asen and Gent (2019) argued that the usefulness of research is determined by necessity, relevance, and sufficiency.

Research can be used in different ways to shape disruptive decisions. For example, RPP dynamics, activities, and products may shape thinking on education policy and practice (conceptual use of research evidence) by decisionmakers (e.g., school board members, district and school leaders), investments in policies, programs, and personnel for reducing disparities (instrumental use of research evidence) by decisionmakers, or validate prior held positions, preferences, or decisions on education policy and practice (symbolic/strategic use of research evidence).

Research evidence can inform leadership practice through multiple pathways (Farrell et al., 2022). Research can also shape research habits of inquiry of district officials and researchers (Coburn et al., 2013; Coburn and Penuel, 2016; Farrell et al., 2018; Farrell and Coburn, 2017). Equity-centered RPPs have introduced antiracist tools supporting local decisionmakers’ capacity to reduce inequality in education, but emphasized that using these tools is not sufficient to disrupt inequality: RPP participants must also name and engage with racial tensions within RPPs to realize disruptive decisions (Diem et al., 2024).

Yamashiro et al. (2023) discussed how an RPP’s routines and structures for collaboration (i.e., internal politics) can also facilitate the RPP’s negotiation of external political considerations. Creating processes for members to address issues of power, privilege, and access within the RPP facilitates consensus around the values and norms of the RPP, which can streamline and unify the RPP’s external relations and messages. This applies to the RPP’s relationships with both the research and practice institutions as well as with other community institutions, such as parents’ groups (Anderson, 2023; Klein, 2023). The ways of functioning and routines of equity-centered RPPs, in addition to traditional research products, can shape districts’ policies and practices in various ways to advance equity.

A relational approach to the use of research evidence centered on relevance and relationships suggests that the work of the RPP is not solely about generating research but also fostering engagement to facilitate the use of research in decision-making. Decision-making is a social and interactive process that spans multiple levels of the educational systems in which data and research must be interpreted (Coburn and Talbert, 2006; Huguet et al., 2017; Tseng, 2022; Weiss and Bucuvalas, 1980). Decisions are a result of both formal and informal interactions. Decisionmakers at the school board, district and school-level access and use research evidence in different ways throughout the policy process (DeBray et al., 2014; McDonnell and Weatherford, 2013; Penuel et al., 2018; Tseng and Nutley, 2014).

Changes in practice and policy are a function of decisions by key decisionmakers at multiple educational governance levels in local contexts. In the U.S, contemporary educational policy-making remains a largely local affair as principals and district central office leaders play a central role as the primary decisionmakers on the programs and reforms that schools implement (Farrell et al., 2022; Penuel et al., 2017). Though equity-centered RPPs may start with working with school and district leaders, over time, there will be increasing engagement and possible participation with other decisionmakers interested in advancing equity, namely teachers, parents and school board members. Through participating in an RPP or through working in a district engaged in RPP work, decisionmakers’ capacities for using and responding to research evidence grows, supporting capacity and resources for disruptive decision-making.

Ahn et al. (2024) highlighted that “some RPP projects acknowledge equity and social justice goals as motivations for their work, but very few studies utilize frameworks that directly center equity and social justice or articulate any clear, direct contribution to equity and justice outcomes (Vetter et al., 2022)” (p.296). We hope the theory of action for equity-centered RPPs provides RPP members and researchers with a framework to better conceptualize and manifest equity in their partnerships. A theory of action matters for research use. A theory of action is necessary but not sufficient for fostering tools that support the use of research evidence. This theory of action adds to the ongoing conversation on equity-centered RPPs in the spirit of collaborative learning. We synthesize and acknowledge the budding body of studies on equity-centered RPPs. This framework also contributes to the RPP literature with its explicit focus on race and power in the fabric and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs.

An equity-centered RPP is the culmination of equity-centered research, equity-centered practices, and equity-centered partnership. Within each of these elements, there are operative processes and outcomes that require intentionality and thoughtfulness to fully manifest the potential of equity-centered RPPs to shape learning in district offices, schools, and universities. Equity-centered RPPs are rooted in boldness and intentionality in order to navigate the myriad pressures emanating from the political, social, historical, and economic context in which partnerships are created, sustained, and expanded. Intentionality can guide the dynamics, activities, and outcomes of RPPs.

Equity-centered RPPs are a strategy to both improve the use of research evidence and reduce inequality in education. The ways in which equity-centered RPPs foster research use holds significant potential to disrupt inequities in education and improve youth outcomes. To unlock the potential of equity-centered RPPs, a richer understanding of partnership processes is necessary to improve the proximal outcomes of equity-centered RPPs, which in turn will reduce group differences in key educational outcomes.

Farrell et al.’s (2021) defining principles (partnerships that are enduring, directly support school-based improvement and/or transformation, engage explicitly with research (producing and consuming), and include and center individuals across roles and experiences) can be manifested in the process of partnering through various partnership structures, such as design-based research, improvement networks, and research alliances (Vetter et al., 2022). Equity-centered RPPs use continuous improvement principles and methodologies in activities as they grow and evolve. Consider the case of the equity-centered RPP that inspired the framework:

Since 2017, district leaders in urban-emergent district in the Southeastern U.S. have partnered with researchers to produce and use research on school discipline policy and practice to reduce discipline disparities. The composition, goals, and approaches to research in the partnership are highly attentive to race and power. This partnership is entering a new phase and pivoting from understanding disproportionalities in students’ disciplinary outcomes to transforming these inequities through collaboration and research. Starting in 2024, the partnership embarked on the co-design of in-school suspension (ISS). The co-design process starts with a co-design team at each middle school comprised of the principal, assistant principals, ISS personnel, and behavior specialists. The co-design teams will individually and collaboratively meet with researchers and district leaders to analyze data and brainstorm ways to improve the processes and structures of ISS. Attending to race and power in research approaches, such as incorporating an intersectionality lens in co-design workshops, shape collaborative, iterative discipline inquiries for improvement as insights emerging from co-design. They not only shape disciplinary processes and structures through iteration but also inform improvements in other district practices, such as the design of the school discipline dashboard. Focusing attention on race and power spotlight data and disparities and create a space to hold tensions in the many uncomfortable conversations, such as discussing teachers’ racialized perceptions of student behavior, that accompany iterative inquiries for improvement. Attending to race and power also makes researchers more discerning of evidence of effectiveness and implications for traditionally marginalized groups when synthesizing evidence. Attending to race and power amplifies the commitment to change of RPP members and creates the confidence and conditions to make disruptive decisions like the district-wide implementation of restorative practices.

The theory of action is intended to aid researchers studying equity-centered RPPs in the design of their studies and their attention to theory-building. It is not meant to be final or exhaustive, but rather collaborative and iterative as scholars provide empirical evidence on the operations and outcomes of equity-centered RPPs. Empirical studies on RPPs are limited yet necessary to refine the theories of action governing partnership work (Farrell et al., 2021, 2023; Glazer et al., 2023; Penuel and Hill, 2019; Tseng, 2017; Welsh, 2021), particularly with respect to the relationships between equitable internal processes, and equitable products and outcomes. There is a need for empirical studies to expand the nascent literature on how partnership participants conceptualize and operationalize equity in equity-centered RPPs and contribute to a granular understanding of “what equity means and looks like within RPP efforts” (Farrell et al., 2022, p. 2). Studying equity-centered RPPs is a pathway to develop a richer understanding of the use of research evidence. The theory of action will enable scholars to empirically probe how an equity-centered RPP supports research use and improves student outcomes. The framework may also guide the creation of research instruments and indicators to assess the functioning of an equity-centered RPP and inform additional studies of equity-centered RPPs.

Using the theory of action as a guide to study equity-centered RPPs will add valuable insights to the growing debate on whether and how education leaders in different decision-making roles use research evidence differently (Mills et al., 2020; Penuel et al., 2018) and a better understanding of the types of research evidence educators and education leaders find useful (Farrell et al., 2022). By centering the process of partnering in equity-centered RPPs, researchers may unpack the roles of race and power in the dynamics of RPPs and provide the connections between partnership dynamics, partnership activities, and some of the proximal outcomes of equity-centered RPPs. The resulting insights may extend prior findings on race and power in district policy deliberation and the process of partnering in equity-centered RPPs (Huguet et al., 2021; Tseng, 2022; Turner, 2015, 2020; Welsh, 2021). Making race and power visible is critical to building a theoretical and conceptual understanding of how equity-centered RPPs may improve the use of research evidence. The use of research evidence in equity-centered RPPs and deliberations regarding educational equity at the school and district-level is layered with discourse related to race and power (Huguet et al., 2021; Turner, 2015, 2020). District leaders view problems and solutions through a racial lens manifested in explicit and implicit racial discourse (Turner, 2020). Furthermore, the equity orientation of equity-centered RPPs does not preclude deficit discourse or foster opportunity gaps discourse (Huguet et al., 2021; Turner, 2020). Accordingly, particular attention should be paid to race and power in the discourse of decisionmakers. Observation analysis focuses on discursive expressions of power with emphasis on language and interaction (who speaks, how they speak, who interrupts, who is heard, who redirects, and the body language of board members in conversations on school discipline, school climate and culture, and equity in education, as well as manifestations of unequal expressions of power based on race, gender, and class). Researchers studying equity-centered RPPs may consider following the approach of Huguet et al. (2017) and focus on decision trajectories and episodes to segment observations.

There is a crystallizing consensus on the importance of evidence to inform education policy and practice, as well as the complexities of research utilization (Coburn et al., 2009a; Farley-Ripple, 2012; Tseng, 2022; Tseng et al., 2017). The theory of action also has a practical function in that it serves as a guiding tool for the work of the partnership, a north star that guides how the partnership aims to design and enact work in an equitable manner to advance equity outcomes. The framework can guide how the partnership assesses progress towards equity related goals. RPPs function in fields ranging from medicine to criminal justice to education and connect researchers with practitioners to work jointly to improve processes, policies, practices, and/or outcomes (Brotman et al., 2021; Farrell et al., 2021; Sullivan et al., 2013, 2017). Even though our focus is on K-12 education partnerships, the prevailing insights can be applied to other fields, such as health. Within the context of the RPP from which the theory of action emerged, RPP members are enacting the framework to guide decision-making and develop a shared understanding of the goals of the work and the guiding tenets of the equity-centered approach. We hope participants in equity-centered RPPs draw inspiration and ideas to better manifest equity in both process and outcomes.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

RW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KJM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was generously supported by the William T. Grant Foundation and the American Institutes for Research Equity Initiative (Grant ID 203768).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahn, J., Gomez, K., Lee, U.-S., and Wegemer, C. M. (2024). Embedding racialized selves into the creation of research-practice partnerships. Peabody J. Educ. 99, 295–313. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2024.2357031

Alemán, E. (2006). Is Robin Hood the “prince of thieves” or a pathway to equity?: applying critical race theory to school finance political discourse. Educ. Policy 20, 113–142. doi: 10.1177/0895904805285290

Anderson, E. R. (2023). Political considerations for establishing research-practice partnerships in pursuit of equity: organizations, projects, and relationships. Educ. Policy 37, 77–100. doi: 10.1177/08959048221130993

Arce-Trigatti, P., Chukhray, I., and López Turley, R. N. (2018). Research–practice partnerships in education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 561–579.

Archibald, J.-A. (2008). Indigenous Storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

Asen, R., and Gent, W. (2019). Reconsidering symbolic use: a situational model of the use of research evidence in polarised legislative hearings. Evid. Policy 15, 525–541. doi: 10.1332/174426418X15378681033440

Bang, M., and Vossoughi, S. (2016). Participatory design research and educational justice: studying learning and relations within social change making. Cogn. Instr. 34, 173–193. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2016.1181879

Barton, A. W., Futris, T. G., and Nielsen, R. B. (2014). With a little help from our friends: couple social integration in marriage. J. Fam. Psychol. 28, 986–991. doi: 10.1037/fam0000038

Bensimon, E. M. (2018). Reclaiming racial justice in equity. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning. 50, 95–98. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2018.1509623

Brotman, L., Dawson-McClure, S., Rhule, D., Rosenblatt, K., Hamer, K., Kamboukos, D., et al. (2021). Scaling early childhood evidence-based interventions through RPPs. Futur. Child. 31, 57–74. doi: 10.1353/foc.2021.0002

Bulkley, K. E. (2013). Conceptions of equity: how influential actors view a contested concept. Peabody J. Educ. 88, 10–21. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2013.752309

Castro, E. L. (2015). “Addressing the conceptual challenges of equity work: A blueprint for getting started” in Understanding Equity in Community College Practice, ed. E. L. Castro 172, (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons), 5–13.

Coburn, C. E., Bae, S., and Turner, E. O. (2008). Authority, status, and the dynamics of insider–outsider partnerships at the district level. Peabody J. Educ. 83, 364–399. doi: 10.1080/01619560802222350

Coburn, C. E., Honig, M. I., and Stein, M. K. (2009a). “What’s the evidence on districts’ use of evidence?” in Research and practice in education: Towards a reconciliation. eds. J. Bransford, L. Gomez, D. Lam, and N. Vye (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press).

Coburn, C. E., Toure, J., and Yamashita, M. (2009b). Evidence, interpretation, and persuasion: instructional decision making at the district central office. Teachers College Record. 111, 1115–1161. doi: 10.1177/016146810911100403

Coburn, C. E., and Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res. 45, 48–54. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16631750

Coburn, C. E., Penuel, W. R., and Geil, K. (2013). Research practice partnerships at the district level. William T. Grant Foundation. Available at: https://rpp.wtgrantfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Research-Practice-Partnerships-at-the-District-Level.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Coburn, C. E., and Talbert, J. E. (2006). Conceptions of evidence use in school districts: mapping the terrain. Am. J. Educ. 112, 469–495. doi: 10.1086/505056

DeBray, E., Scott, J., Lubienski, C., and Jabbar, H. (2014). Intermediary organizations in charter school policy coalitions: evidence from New Orleans. Educ. Policy 28, 175–206. doi: 10.1177/0895904813514132

Denner, J., Bean, S., Campe, S., Martinez, J., and Torres, D. (2019). Negotiating trust, power, and culture in a research–practice partnership. AERA Open 5:2332858419858635. doi: 10.1177/2332858419858635

Diamond, J. B. (2021). Racial equity and research practice partnerships 2.0: A critical reflection. William T. Grant Foundation. Available at: https://wtgrantfoundation.org/racial-equity-and-research-practice-partnerships-2-0-a-critical-reflection (Accessed August 18, 2023).

Diamond, J. B., and Gomez, L. M. (2023). Disrupting white supremacy and anti-black racism in educational organizations. Educ. Res. 0013189X231161054:0013189X2311610. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231161054

Diem, S., Iverson, E., Welton, A. D., and Walters, S. W. F. (2024). A path toward racial justice in education: anti-racist policy decision making in school districts. Educ. Policy 38, 1526–1562. doi: 10.1177/08959048241271329

Doucet, F. (2019). Centering the margins: (re)defining useful research evidence through critical perspectives. In William T. Grant Foundation. William T. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED609713 (Accessed October 16, 2023).

Doucet, F. (2021). Identifying and testing strategies to improve the use of antiracist research evidence through critical race lenses. William T. Grant Foundation.

Drame, E., and Irby, D. J. (2015). Positionality and racialization in a PAR project: reflections and insights from a school reform collaboration. Qual. Rep. 20, 1164–1181. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2236

Dumont, K. (2019). Reframing evidence-based policy to align with the evidence. In William T. Grant Foundation. William T. Grant Foundation. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED624645 (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Farley-Ripple, E. N. (2012). Research use in School District central office decision making: A case study. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadership 40, 786–806. doi: 10.1177/1741143212456912

Farrell, C. C., and Coburn, C. E. (2017). Absorptive capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding district central office learning. J. Educ. Chang. 18, 135–159. doi: 10.1007/s10833-016-9291-7

Farrell, C. C., Davidson, K. L., Repko-Erwin, M., Penuel, W. R., Quantz, M., Wong, H., et al. (2018). A descriptive study of the IES researcher-practitioner partnerships in education research program: final report. Technical report no. 3. In National Center for research in policy and practice. National Center for Research in Policy and Practice. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED599980 (Accessed October 28, 2023).

Farrell, C. C., Harrison, C., and Coburn, C. E. (2019). “What the hell is this, and who the hell are you?” role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. AERA Open 5:2332858419849595. doi: 10.1177/2332858419849595

Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A., Anderson, E. R., Bohannon, A. X., Coburn, C. E., et al. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research–practice partnerships. Educ. Res. 51, 197–208. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211069073

Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Coburn, C. B., Daniel, J., and Steup, L. (2021). Research-practice partnerships in education: The state of the field. Grant Foundation: William T.

Farrell, C. C., Singleton, C., Stamatis, K., Riedy, R., Arce-Trigatti, P., and Penuel, W. R. (2023). Conceptions and practices of equity in research-practice partnerships. Educ. Policy 37, 200–224. doi: 10.1177/08959048221131566

Finnigan, K. S. (2023). The political and social contexts of research evidence use in partnerships. Educ. Policy 37, 147–169. doi: 10.1177/08959048221138454

Gamoran, A. (2023). Advancing institutional change to encourage faculty participation in research-practice partnerships. Educ. Policy 37, 31–55. doi: 10.1177/08959048221131564

Gamoran, A., and Bruch, S. K. (2017). Educational inequality in the United States: can we reverse the tide? J. Educ. Work. 30, 777–792. doi: 10.1080/13639080.2017.1383091

Glazer, J. L., Shirrell, M., Duff, M., and Freed, D. (2023). Beyond boundary spanning: theory and learning in research-practice partnerships. Am. J. Educ. 129, 265–295. doi: 10.1086/723061

Grace, J., and Lastrapes, R. E. (2024). What do School administrators think about race? A critical race mixed-method study. J. Sch. Leadership 34, 177–201. doi: 10.1177/10526846231194349

Gutiérrez, K. D. (2016). 2011 AERA presidential address: designing resilient ecologies: social design experiments and a new social imagination. Educ. Res. 45, 187–196. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16645430

Gutiérrez, K. D., and Jurow, A. S. (2016). Social design experiments: toward equity by design. J. Learn. Sci. 25, 565–598. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2016.1204548

Gutiérrez, K. D., and Vossoughi, S. (2010). Lifting off the ground to return anew: mediated praxis, transformative learning, and social design experiments. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 100–117. doi: 10.1177/0022487109347877

Henrick, E., Cobb, P., Penuel, W. R., Jackson, K., and Clark, T. (2017). Assessing research-practice partnerships. Grant Foundation: William T.

Henrick, E., Farrell, C. C., Singleton, C., Resnick, A. F., Penuel, W., Arce-Trigatti, P., et al. (2023). Indicators of research-practice partnership health and effectiveness: updating the five dimensions framework. National Center for Research in Policy and Practice.

Henrick, E., McGee, S., and Penuel, W. (2019). Attending to issues of equity in evaluating research-practice partnership outcomes. NNERPP Extra 1, 8–13. doi: 10.25613/XAPZ-QT83

Henrick, E., Munoz, M. A., and Cobb, P. (2016). A better research-practice partnership. Phi Delta Kappan 98, 23–27. doi: 10.1177/0031721716677258

Holmes, A. G. D. (2020). Researcher positionality—A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research—A new researcher guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 8, 1–9. doi: 10.34293/education.v8i2.1477

Honig, M. I., Venkateswaran, N., and McNeil, P. (2017). Research use as learning: the case of fundamental change in School District central offices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 54, 938–971. doi: 10.3102/0002831217712466

Huguet, A., Allen, A.-R., Coburn, C. E., Farrell, C. C., Kim, D. H., and Penuel, W. R. (2017). Locating data use in the microprocesses of district-level deliberations. Nordic J. Stud. Educ. Policy 3, 21–28. doi: 10.1080/20020317.2017.1314743

Huguet, A., Coburn, C. E., Farrell, C. C., Kim, D. H., and Allen, A.-R. (2021). Constraints, values, and information: how leaders in one district justify their positions during instructional decision making. Am. Educ. Res. J. 58, 710–747. doi: 10.3102/0002831221993824

Hytten, K., and Stemhagen, K. (2023). Abolishing, renarrativizing, and revaluing: dismantling Antiblack racism in education. Educ. Res. 0013189X221143092:0013189X2211430. doi: 10.3102/0013189X221143092

Ishimaru, A. M., Barajas-López, F., Sun, M., Scarlett, K., and Anderson, E. (2022). Transforming the role of RPPs in remaking educational systems. Educ. Res. 51, 465–473. doi: 10.3102/0013189X221098077

Kirkland, D. E. (2019). No small matters: Reimagining the use of research evidence from A racial justice perspective. William T. Grant Foundation.

Klein, K. (2023). It’s complicated: examining political realities and challenges in the context of research-practice partnerships from the School District Leader’s perspective. Educ. Policy 37, 56–76. doi: 10.1177/08959048221130352

Krishnan, S., Dickson, S., and Henrick, E. (2024). Equity-centered and vision-aligned research: strategies of a district research office to build better research collaborations. NNERPP Extra 6, 8–16. doi: 10.25613/C9SZ-HZ43

Little, S. J., and Welsh, R. O. (2022). Rac(e)ing to punishment? Applying theory to racial disparities in disciplinary outcomes. Race Ethnicity and Education, 25, 564–584.

López Turley, R. N., and Stevens, C. (2015). Lessons from a School District–university research partnership: the Houston education research consortium. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 37, 6S–15S. doi: 10.3102/0162373715576074

McDonnell, L. M., and Weatherford, M. S. (2013). Evidence use and the common Core state standards movement: from problem definition to policy adoption. Am. J. Educ. 120, 1–25. doi: 10.1086/673163

Mills, K. J., Lawlor, J. A., Neal, J. W., Neal, Z. P., and McAlindon, K. (2020). What is research? Educators’ conceptions and alignment with United States federal policies. Evid. Policy 16, 337–358. doi: 10.1332/174426419X15468576296175

Milner, H. R. (2007). Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen. Educ. Res. 36, 388–400. doi: 10.3102/0013189X07309471

Najarro, I. (2022). Schools trying to Prioritze equity have their work cut out for them, Survey Shows. EdWeek. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/schools-trying-to-prioritize-equity-have-their-work-cut-out-for-them-survey-shows/2022/11 (Accessed September 7, 2024).

Nicholson-Crotty, J., Grissom, J. A., and Nicholson-Crotty, S. (2011). Bureaucratic representation, distributional equity, and democratic values in the Administration of Public Programs. J. Polit. 73, 582–596. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000144

NNERPP (n.d.). Home page. National Network of education research-practice partnerships. Available at: https://nnerpp.rice.edu/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Noble, C. E., Amey, M. J., Colón, L. A., Conroy, J., De Cheke Qualls, A., Deonauth, K., et al. (2021). Building a networked improvement community: lessons in organizing to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Front. Psychol. 12:732347. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.732347

Okamoto, D. (2024). “Engaging with race and racism in research” in New approaches to inequality research with youth: Theorizing race beyond the traditions of our disciplines. eds. E. Tuck, K. W. Yang, and J. Nixon (1st ed). (New York: Routledge).