- 1Department of Educational Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

- 2Yale Health Mental Health and Counseling, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 3Marxism College, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China

- 4Mental Health Education Center, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

- 5Hubei Oriental Insight Mental Health Institute, Wuhan, China

- 6Department of Psychology, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

Introduction and background: Research indicates that Chinese International College Students (CICS) encounter considerable cultural and mental health challenges while studying in the United States. However, there has been limited focus on the processes and outcomes of effective mental health intervention programs tailored to their needs. This study adopted a research-through-service approach to design, implement, and evaluate a four-week group intervention program aimed at enhancing the mental health and well-being of CICS.

Methods and intervention program: The group intervention was designed with the perspective that effective mental health services for CICS should be culturally specific, growth-oriented, and focused on promoting positive learning outcomes rather than merely addressing problems or solutions. Group sessions were conducted in Chinese and emphasized experiential activities aimed at enhancing participants’ cultural confidence and fostering a growth-oriented, positive mindset. Thirteen CICS voluntarily participated in the group intervention. One to three weeks after the program, twelve participants took part in semi-structured post-group interviews. These interviews explored their reflections on the group experience, their general perspectives on well-being, perceived challenges and strategies for managing those challenges, and their attitudes toward seeking professional help when needed. The interview data were analyzed using the Consensus Qualitative Research (CQR) method (Hill, 2012).

Results: Participants shared experiences of cultural conflicts and challenges they faced, as well as the active coping strategies they employed. These strategies included confiding in trusted individuals, practicing forbearance and self-regulation, and seeking practical solutions to underlying problems. When reflecting on the group intervention experience, participants reported notable benefits across intellectual, relational, and emotional domains. Additionally, they provided valuable suggestions for enhancing the program’s effectiveness.

Conclusion: Intervention programs designed to support Chinese International College Students (CICS) should promote cultural confidence, adopt a strength-based and growth-oriented approach, and avoid deficit-focused or problem-centered frameworks.

Research through service: meeting Chinese international college students’ mental health needs

International college students constitute a large and valuable resource for the United States, from making significant epistemic contributions to academic fields (Xu, 2021) and economic contributions to local communities (Hegarty, 2014) to diversifying campus culture (USC US-China Institute, 2021) and to facilitating the internationalization of higher education (Urban and Palmer, 2014). However, while making such contributions international students must endure and overcome significant obstacles to succeed due to a variety of academic, cultural and social adjustment challenges (Lai et al., 2023). Educational institutions have the responsibility to provide effective support services to meet those students’ needs and support their mental health (Skinner et al., 2019). Unfortunately, research on how to provide effective support service is limited, although the types and severity of the challenges faced by international students have been well documented (e.g., Amlashi et al., 2024; Ching et al., 2017; Skinner et al., 2019; Su et al., 2021). In an effort to learn about effective mental health services for international students, we conducted a research-through-service project. We designed and implemented a group experience to 13 Chinese international undergraduate students (four males and nine females, all in the first and second year of study) in a mid-western university and conducted extensive interviews with 12 of them afterwards to explore their experiences of the group, their overall mental health needs, and their perspectives on beneficial support services.

Chinese international college students (CICS) in the United States

Students from China over numbered those from any other countries and constitute more than one-fourth of the entire international student population in the US (IIE, 2023). According to the Migration Policy Institute (Israel and Batalova, 2021), the number of Chinese students studying in the United States has steadily increased in the past several decades before the pandemic and reached 373,000 in the 2019/20 academic year. It is reported that STEM majors are most popular among Chinese students with nearly half of them studying engineering, mathematics, computer science, and physical life science (Lu, 2019).

Characteristics of recent CICS

Most CICS are motivated students as they are attracted to studying in the United States largely by academic and career reasons, including the advanced scientific status of many academic fields, freedom in choosing majors, and access to more career opportunities (Chao et al., 2019). However, there are other characteristics of them that need to be recognized and integrated into our understanding of and service to their psychological needs.

First, most recent CICSs are “single child” to their parents due to the “One Child” national policy in China from 1979 to 2015 (Zhang, 2017). This is an important context for understanding their relationship needs, skills, and behaviors, as many of them grew up being the center of attention at home and having no need to share with siblings. Further, due to growing up in a relatively open and multimedia learning environment they are generally not as placid or shy as older generations of Chinese (Lai et al., 2023).

Secondly, the recent CICSs grew up in China during a time when both the Chinese culture (the foundation of their parents’ life experience) and imported Western culture constitute their life context (Odinye, 2012). Most likely they have been socialized to honor some foundational Chinese cultural values such as family, relationship, and harmony as well as adopt some Western ideals such as autonomy and independence (Lei, 2017). Accordingly, it is expected that they may feel conflicted or confused at times when confronted by different demands based on different cultural values. For instance, should one choose a college major based on their own interest or follow their parents’ expectations? The former may fit the norm and be viewed as healthy in the host culture while the latter is viewed as appropriate and expected in their heritage culture (Guan et al., 2015).

Thirdly, most recent CICS’ schooling in the United States is funded by their parents, which is a huge financial investment by the family. College education in China would cost significantly less than that in the US. Available data have suggested that most of the families are regular income earners, well-to-do but not excessively so (Mendoza, 2016). The psychological implication of this situation on CICS is imaginable, especially in consideration of the Chinese cultural value regarding individuals’ family responsibilities. While it is hugely positive to have family support, it is unavoidable that family’s sacrifices create mental pressure for the students, which could lead to feelings of fear of failure, being a burden to the family, or having little freedom of not following parents’ request.

Successes and challenges of CICS

In the past few decades, thousands of Chinese international students in the United States have successfully completed their college education. Although a significant proportion of them built their career in the United States, Chinese job market has embraced an increasing number of those who returned to China after graduation (Xinhua, 2024). Their successes and achievements, however, are not obtained without significant and sometimes exhausting efforts to overcome the myriad challenges unique to them as international students from China.

Chinese students have reportedly experienced significant challenges in adjusting to studying and living in the U.S., including in academic learning, sociocultural adaptation, and their identity development (Zhang, 2021). A survey of over 500 Chinese international students (mostly in graduate programs) revealed that more than 65% of them felt well-adjusted but 20% of them remained “consistently distressed or culture-shocked” even after three semesters (Wang et al., 2012, p. 430). Beyond adjusting to a new learning and living environment, they are confronted by language barriers and high levels of cultural differences in academic work (Bonazzo and Wong, 2007; Han et al., 2013), including the difference in learning and educational styles and methods (Li et al., 2017). Poor relationships and communication with advisors and course professors are common stressors and could lead to experiences of cultural shock, academic challenges, and interpersonal difficulties (Ching et al., 2017) as well as depression and anxiety (Han et al., 2013). Moreover, anti-Asian discrimination and hostility can have negative psychological consequences and exacerbate homesickness and a sense of isolation for CICS (Xiong et al., 2022).

Current understanding and support programs

Various programs have been developed and implemented to support the mental health and cultural adjustment of CICS and other international students. These include standard campus services (e.g., orientation, counseling, culture/language exchange programs) and more specialized programs focused on academic support (e.g., English language support, tutoring, mentoring) or adjustment and acculturative stress reduction (e.g., psychoeducational, cultural orientation, socio-cultural, and peer-pairing programs) (Aljaberi et al., 2021). Personalized help-seeking web applications have also recently been developed for CICS students (Choi et al., 2023). Despite these efforts, however, research on the efficacy of these programs is limited, and a significant gap remains in understanding how to deliver or implement effective and inclusive mental health services to international students (Sakız and Jencius, 2024).

Although educational institutions have demonstrated a growing commitment to developing and implementing programs designed to support international students, a significant proportion of these programs continue to adopt a deficit-based approach, emphasizing problem remediation rather than the promotion of positive student development (Lee et al., 2021). This prevailing approach is consistent with the broader scholarly discourse on international student experiences, which has been largely shaped by a colonial, imperial paradigm and informed by deficit models of language, culture, and literacy (Neupane, 2022, p. 50). Some scholars have pointed out that a key factor contributing to the challenges faced by CICS students in the United States is actually the lack of intercultural competence within U.S. educational systems (Heng, 2023). This systemic inadequacy forces students to “shoulder the burden of adjusting, with the host culture used as a benchmark against which to measure their success” (p. 1). This systemic failure places the burden of adjustment on students, who are measured against the host culture (p. 1). Consequently, international students’ challenges are often publicly portrayed as deficiencies. In contrast to this approach, we advocate for a sociocultural perspective that recognizes CICS students’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds, prior schooling, and life experiences as strengths.

The present project

A comprehensive literature review on Chinese international college students (CICS) revealed several key themes. First, a dominant focus on identifying challenges has led to extensive lists of stressors and obstacles faced by CICS (e.g., Ching et al., 2017). This deficit-based approach not only reinforces negative stereotypes (Liu et al., 2023) but also reflects a colonial and imperial perspective on culturally and linguistically diverse students (Neupane, 2022). Second, influenced by this dominant deficit model, suggested interventions often focus on overcoming specific difficulties, such as language barriers (e.g., Mei, 2017) or student-professor relationships (e.g., Kingston and Forland, 2008). This resulted in a mis-perception regarding CICS’ mental health needs. Third, although various programs and recommendations aim to help CICS cope with challenges (e.g., Maleku et al., 2021), evidence of effective implementation is lacking, and the efficacy of these practices is frequently mis-evaluated through a deficit lens of language, culture, and competence (Neupane, 2022). Finally, a promising trend toward a culture-centered and asset-based approach is emerging, promoting a socioculturally attuned understanding of and engagement with CICS (e.g., Heng, 2023; Neupane, 2022). This shift offers the potential to mitigate the negative consequences of deficit-focused research and interventions.

Based on these observations, we saw a critical need for practical and functional interventions that align with the characteristics and needs of CICS, providing effective support grounded in respect and appreciation for their culture and their being. Therefore, the present project employed a research-through-service methodology to develop, implement, and evaluate an intervention program for CICS. This intervention focuses on providing support, validation, and encouragement to CICS as individuals, with problem-solving anticipated as a secondary, emergent outcome. We intend to join the emerging effort to promote a socioculturally tuned approach in understanding and supporting CICS by developing a culture-specific, growth oriented, and positive learning outcome driven (vs. problem or problem solution focused) intervention program.

Our design of the intervention drew upon several theoretical frameworks: ethnic identity studies (e.g., Sue et al., 1998), self-determination theory (e.g., Ryan and Deci, 2017), positive psychology (e.g., Fredrickson, 2004), and research on Chinese students’ mental health values (e.g., Lei, 2017). Recognizing the significant roles of ethnic identity in psychological well-being (Smith and Sylva, 2011) and cultural confidence in mitigating mental health risks (Liao, 2012), we adopted a Chinese culture-centered approach focused on fostering cultural confidence. Informed by self-determination theory, the intervention aimed to enhance participants’ sense of competence through engaging and accessible activities. We also prioritized a person-centered approach (Weber et al., 2004), focusing on fostering feelings of understanding, validation, and value, and strengthening interpersonal relationships. This emphasis on positive development contrasts with the problem-focused orientation of many existing programs. We believe that effective interventions should be strength-based, positive, and growth-oriented, an approach supported by positive psychology theories such as Fredrickson (2004) Broaden-and-Build theory. Furthermore, we incorporated key Chinese mental health values, including harmonious interpersonal relationships, adherence to life principles, prioritization of family, pursuit of purpose and meaning (Duan et al., 2022), and emphasis on achievement and effective communication (Lei, 2017). The intervention’s overarching goal was to empower CICS, fostering motivation, positivity, and hope while respecting their cultural characteristics.

Method

Intervention service: theme-based and semi-structured growth group experience participants

Group facilitators

The group was co-facilitated by two female credentialed counseling psychologists from China (the third and fourth authors; they were visiting scholars in the U.S. at the time of this intervention/research project). One of them held a doctoral degree in counseling psychology and was a college professor, and the other a master’s degree in social work and was a psychological counselor for a college in China. They were in their early and mid-40th, respectively, and had worked with college students in mental health related teaching and counseling for over 10 years. Besides the co-facilitators, two female doctoral Chinese international students in counseling psychology (the second and sixth authors) also attended the group activities as observers/assistants.

Group members

The intervention program was open to all CICS on a midwestern university campus. Thirteen CICS (three males and ten females) responded to an announcement of the group on the Chinese student association’s community wechat and participated in the group intervention program. Their age ranged from 19 to 23, major was diverse, and years of U.S. experience varied from 1 to 3.

Group experience design

The first part of our research through service project was to provide CICS needed psychological assistance based on our professional observations and understanding of the literature. Drawing from ethnic identity development theories, we designed the intervention to create a process that provides CICS psychological comfort with a sense of cultural connection and familiarity and to meet their developmental and adjustment needs/interests at this stage of their life. Following the theoretical understanding of the power of positive emotions, we strove to make the program inviting, engaging, and enjoyable. Accordingly, we (1) organized a series of four group sessions under the name “I Can Be Here And There” (contrasting the “Being not here or there” feeling of being culturally misplaced) for any CICS who are interested. We avoided using conventional names such as support group or therapy group and called it a growth group. (2) used multiple group facilitators who are either Chinese educators or Chinese international graduate students in counseling psychology and used the Chinese language for communication and group activities. (3) employed activities that are consistent with CICS mental health values and characteristics and easy for them to get involved in, and (4) designed group activities that fit CICS’ developmental and adjustment needs, such as needing direction for and seeing meaning in life. We intentionally included activities meant to stimulate deeper levels of discussion (beyond talking about the specific difficulties they encountered) such as meaning in life or the art of giving and receiving support. Specifically, we provided tools for expressing feelings, reviewing life experiences, and recognizing that having negative emotions is natural and meaningful. Meanwhile, the focus was on having members encourage and support each other in emotional regulation and debugging, facilitating a sense of belonging, and aiming at their ultimate life goals.

Procedures

We ran four weekly two-hour-long group sessions for four consecutive weeks. At the beginning of each group, authentic Chinese food/snacks, prepared by the group leaders, were shared to help participants feel the care and cultural familiarity. The overarching themes focus on discovering “what we have experienced, what we want to gain, and how we pursue achievement.” The following four group sessions were offered.

Session one

The focus of the first group session was on “The difference and its beauty.” The participants drew self-portraits, prepared thoughtful self-introductions (for use in social settings), expressed expectations for each other in the group, shared their difficulties in acculturation, and validated each other’s experiences. The process was helping participants recognize and feel comfortable with being “different” from domestic students and view the differences as resources. The facilitators provided feedback to validate participants’ feelings and planted a seed of reframing cultural differences as their assets/resources.

Session two

The second group focused on “The challenge: real, normal, and functional.” Participants were first led to experience a warming-up activity in which they symbolically experienced “coming out of a difficult place” with physical moves. Then they drew streams of the major challenges they had encountered in life and noted how they had (or not) overcome them. These activities were to help participants recognize that having ups and downs in life is normal and expected, and they are not the only ones with unfortunate events/experiences in life. Afterwards, participants were instructed to write a letter about their past struggles and attempts to overcome them. Randomly and anonymously, each member took home one letter from another group member so they can write a reply to the anonymous author for sharing in the next session. The goal was to help members see that others share their struggles and that they all had successfully overcome some challenges in the past.

Session three

The third group was about “The benefit of life difficulties: Allowing one to walk out stronger.” Participants each identified the author of the letter they took home and gave the replying letter they composed to the author. They were encouraged to use ways, Chinese or Western, they are comfortable with to “meet and greet” the author and share their replies. Both verbal and nonverbal (handshakes, hugs, bows) actions were observed. Then the group went through a carefully designed experiential activity symbolizing implicit and indirect expression of emotions. Participants took turns to share one “low” experience and then tapped on one random item provided (e.g., a pot or a box) to express their feelings during the struggle and allowed others to experience empathy. Collaboratively, diverse sounds symbolizing different emotions expressed by members seemed to make a symphony. This session was to provide an experience of collaboration and help members gain confidence in overcoming difficulties with each other’s support.

Session four

The last group was “The future for me: Meaning in life.” The group activities included practicing guided imaginary mindfulness, during which participants were led to imagine their life as a big tree. Then they drew the life tree on a big piece of paper to reflect their ideal life, with their dreams and wishes as “fruits” hanging from the tree. In small groups, participants shared with each other their fruits and the meaning of these fruits to them. Afterwards, they shared in the big group their discoveries about their dreams for life and their own strengths and resources that would help them succeed. Returning to their trees, participants each wrote down specific efforts they needed to make in life. The second round of mindfulness practice focused on the feelings they may have after reaching their goals. The intention was to help participants connect their life goals with needed pursuits and gain a sense of control in life, which could prevent or reduce self-negation and feeling lost when running into cultural adjustment difficulties. All group members were encouraged to send farewell wishes to each other at the end of the session.

Research: post intervention interviews

The purpose

Subsequent to the completion of the group intervention, a qualitative interview study was implemented to investigate participants’ experiences and evaluations of the program, their perspectives on psychological well-being (framing well-being in contrast to deficit-based conceptualizations of mental health), their approaches to challenge management, their attitudes toward help-seeking behaviors, and their views on effective forms of psychological assistance. Using a qualitative research method, the post-intervention interview study specifically aimed to solicit information regarding: (1) CICS’s perceived need for psychological support; (2) their perspectives on accessing professional mental health services; (3) the perceived utility of specific components of the intervention; and (4) their recommendations for enhancing the service.

Participants and procedure

Twelve out of the thirteen group members (three males, nine females) were interviewed either individually or in pairs about one to 3 weeks after the group experience. The thirteenth member was not able to do the interview because he moved out of town for internship right after the group was completed. The semi-structured interviews were conducted by the group co-facilitators who followed an interview protocol (Appendix A). The questions covered the following areas: their experiences that have affected their sense of well-being and their challenge coping methods, their views regarding obtaining mental health service, their evaluation of the group experiences, and the suggestions they have for mental health service for CICS. All participants gave permission to be audio recorded, and the recorded interviews were later transcribed for data analysis. The length of the interviews ranged from 55 to 150 min as some participants had more to share than others.

Data analysis

A team of three female Chinese scholars and doctoral students in counseling psychology analyzed the data using CQR (Hill, 2012) method. CQR provides a systematic approach to analyzing complex and nuanced data, emphasizing collaboration and consensus-building among multiple researchers. We selected this method to mitigate potential individual biases and ensure balanced and credible findings. To ensure confidentiality, no identifying information was provided to the data analysis team.

Each team member first read through all the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data. They then used two transcripts to develop domains consensually before they each independently constructed core ideas for the raw data under each domain. Then the team met multiple times to discuss and consensually arrive at final core ideas for each case. The first, second and third authors audited and reviewed the drafts of the consensual versions of the result multiple times. An active feedback-response-review process was engaged and continued with the coding team till everyone felt the results represented the data adequately. The team followed CQR procedure and performed a cross-analysis of themes within domains across cases and constructed categories for each domain. Then the auditors examined the “fit” of those categories and engaged a similar feedback-response-review process before the team finalized the results. The data analysis was conducted in Chinese, the results were translated into English for presentation by three research team members following the back translation process (Brislin, 1980).

Results

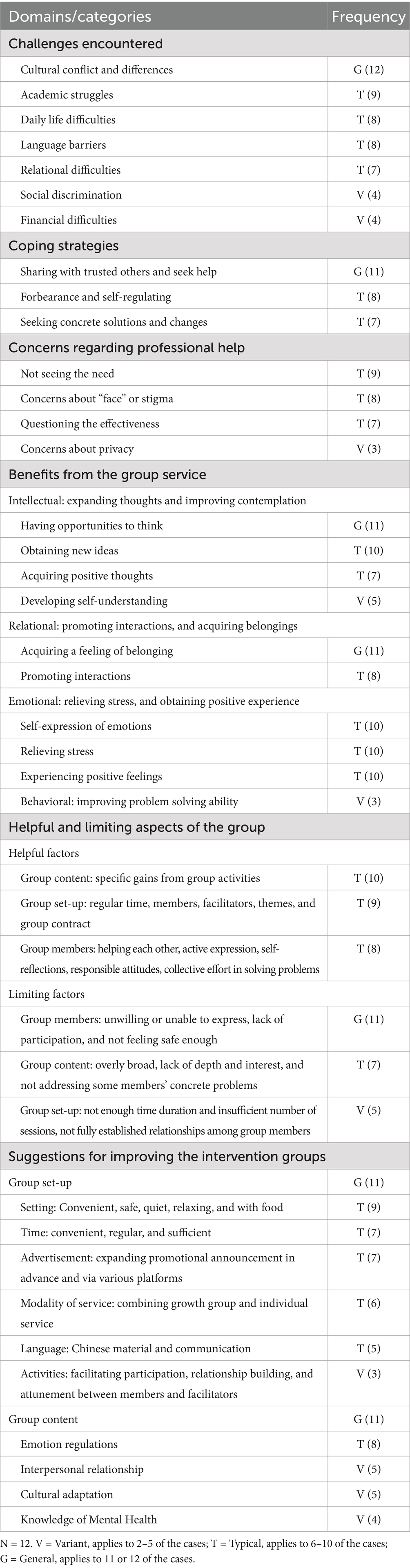

Six domains and 41 categories nested under the domains were identified and presented in Table 1. We labeled the categories and core ideas following Hill’s (2012) recommendation that “general” refers to a result applicable to all or all but one participant (eleven or twelve), “typical” to more than halfway up to the cutoff for general (six to ten), and variant to at least two up to the cutoff for typical (two to five). Data that applied to single cases was excluded from this report.

Challenges encountered

Participants identified challenges they had encountered. They generally reported experience of cultural differences and conflicts studying in the U.S. One participant shared,

It is awkward when classmates talk about their favorite singers or movies because I do not understand what they are talking about. It is even harder when they talk about favorite animations and books. It is hard to translate a Chinese book title, which is embarrassing. We have not hung out together since then.

Another participant said openly “Some people suggest I directly bring up the issues, but I am too reluctant to do so because this way of communication is different from that I learned in my home country.”

Participants typically identified daily life struggles including having different lifestyles from others and barriers in daily life. A participant shared,

My biggest struggle was living with a roommate. We had different habits, and I had language barriers that made me not good at communication. Our schedules were different, but I was afraid to communicate that. I avoided making any noise in the morning to avoid their retaliation. I fear to express my frustration or different thoughts.

Another shared, “My roommate had a different living style, e.g., hygiene, loud stereo, issues with using common space, and bringing guys to our unit.”

Academic struggles are typically identified by the participants, who recognized the struggle in achieving high goals, enduring overloads of courses and tasks, lacking allegiance with their major, and having language barriers in studying. For example, a participant shared that “I have academic stress. I set high expectations for myself and feel stressed out by it. I feel upset when I have too many things to do.” Another participant said, “I feel overloaded with academic stress and have to stay up late to write essays.”

Relational difficulties were typically identified including communication challenges, lack of social support, difficulty in getting involved in communities, and barriers when communicating with own family. A student shared “Unless you were from here, outsiders can hardly get involved however great English you speak. Asians still hang out with Asians. I do not push myself anymore. I do not have to get involved (into the community).” Another noted, “I know one person (Chinese) who spoke English all the time, got along with non-Chinese people, and made great progress in English. But they were kind of excluded by Chinese students.”

Language barriers were typically reported, including fear of and struggle with communication and discussion, and fear of saying something wrong or not understandable to others. As one student shared “(I) feel uncomfortable. I fear being embarrassed making mistakes in front of (American) people. Even if others understand what you meant, you may not be able to understand what they say the next, which is extremely embarrassing.” Another reported, “Poor language also impacts academic performance, which further leads to a decrease in motivation.”

Social discrimination was variantly talked about by interviewees, who reported feeling socially discriminated against by others and feeling worried about it. They were also afraid that nobody would respond to their questions on public platforms. One student noted, “Some teachers were incongruent. They were nice in their appearance but internally viewed me as stupid. They looked down upon me… appeared happy to help, but actually not.”

Financial difficulties were variantly mentioned. A participant described, “my family encountered financial difficulties, so I had to spend a lot of time working a part-time job, and I felt overloaded.”

Coping strategies

CICS try to use various ways to help themselves cope with the difficulties in adapting to studying abroad. Participants generally reported seeking support from trusted others when experiencing mental struggles, such as venting to friends and family, and sometimes seeking professional help. One participant described,

I called my mom two to three times a day at that time, and my mom was never bothered by me. She told me that I would be fine after this. I guess if your parents blame you after you share with them, you would be very likely to become depressed because you are not affirmed by (this place and your parents).

Another participant noted, “I will share with best friend(s) about my uncomfortable feelings, usually with Chinese friends.”

Typically, participants reported using forbearance and self-regulation in coping with challenges, as the result of their family’s education and expectations as well as their own personalities. Sometimes it is because of no other choice. One participant noted, “Everyone has their own struggles. Others are not able to bear you if you vent to them frequently. You cannot always vent to friends.” Another noted, “I mentioned a little bit to my family, but did not disclose details.”

Participants also typically recognized that solving concrete problems that made them struggle or changing the environment is a coping strategy. As a student described, “(I) sought help from others. Firstly, I asked Chinese friends what to do if they were in that situation. Regarding the specific struggles, for example, changing the dorm room, I sought help from my advisor.” Another noted, “I communicated with my roommate by text. Although they did not reply, they changed their behavior a bit as the result.”

Concerns regarding professional help

Participants expressed concerns regarding seeking professional help. They typically reported being unaware of their need to seek professional help. They thought that counseling was for bigger or more serious problems than what they had experienced. Sometimes, they were not aware of the availability of professional help. One participant noted, “Only when it is extremely severe, and I cannot handle it at all by myself, will I seek (counseling). I am afraid that it is a waste of time for others for small struggles such as not doing well in exams.” Another participant noted, “Counseling can only help those who seek help. Many (CICS) do not know it is an option and not because of unwillingness.”

Concern with “face” or stigma with counseling was a typical response. As one participant said, “It would be great if counseling can help. (I am) worried people around me will have stigma and see me as someone with mental problem if I seek counseling.” Another noted, “Some Chinese students are passive in seeking counseling, because they think it means admitting something wrong with them that they could not recover from.”

Participants typically reported doubts about the effectiveness of counseling, including distrusting counselors and feeling that American counselors would not understand them well. Additionally, due to being non-native English speakers, they were afraid of not being able to express their struggles clearly. One participant said, “It is hard for a counselor from a different cultural background to give me the answer that I want. Or maybe the counselor does not think of it as a problem and has difficulty understanding me.” Another participant said, “Some people think that counselors cannot understand them without having the same experiences, so they reject counseling.”

Participants variantly expressed concerns about confidentiality. They were afraid that the content of their therapy would be disclosed to others. For example, one participant said,

Even though I know counselors have professional ethics, the Chinese community is just so small that I am afraid my secret may be accidentally disclosed. It would be terrible if it happened.”

Benefits from the group service

Participants identified four areas in which they gained from the group experience. Intellectually, they felt an expansion of thoughts and contemplation in four aspects. Firstly, they generally reported obtaining opportunities to think and reflect. One participant said, “The group helped me reflect on the causation of some life experiences. I would not think about it in my daily life, but I got to do so in the group.” Another participant said, “I reflected on myself after hearing different thoughts from others.” Secondly, participants typically noted that they obtained new ideas from the group. One participant stated, “I have gained a new sense of meaning which is to help international students who just come here and feel lost.” Another participant said, “I reflected on my relationship with my family and understood something new.” Thirdly, students typically reported the acquisition of positive thoughts and ideas. One participant shared, “I became more hopeful as I realized that I would have a higher and better experience after hitting the bottom in life.” Another participant said, “I found the meaning, that is substantial. I should not give up but stick to it.” Fourthly, students variantly reported achieving better self-understanding from the group. One participant said, “There are commonalities among group members’ experiences and perceptions, which helped me know better who I am in others’ eyes.”

Relationally, participants reported feeling being supported and acquiring a sense of belonging in the group. One participant shared, “I experienced mutual support as others are seriously helping me figure out the solutions to my struggles.” Another participant said, “I was not the only one that had experienced depressing time. I am not alone.” It is typical that students experience promotion of interactions with others. One said, “in the real world we usually say hi and leave. But in the group, we sat down and talked to each other.” Another said, “I got opportunities to understand others in this group.”

Emotionally, participants reported gains in three aspects. Firstly, it is typical that participants reported gaining opportunities to express themselves emotionally. One participant said, “I found that I can show the real me. I do not have to suppress and isolate myself but express my feelings.” Another said, “People can calm down and chat in the group after being emotional.” Secondly, participants typically reported feeling less stressed as a result of the group. As one participant shared, “It is relaxing and free of worry in the group. I felt well relieved.” Another student shared, “After releasing my stress, I felt much better and able to fall asleep.” Thirdly, students typically experienced positive feelings. One said, “I feel warm in heart.” Another noted, “I feel satisfied when others accept what I said.”

Behaviorally, participants variantly reported that the group activities and exercises helped them improve problem-solving ability. One said, “The group activity helped me become interested in socialization. I was able to talk to old friends and acquaint new friends as well.” One said, “Helping others is also a way to address my own concerns. I found it easier and more objective when solving problems for others, while benefitting from the solution myself as well.”

Helpful and limiting aspects of the group

Participants recognized three helpful aspects of the group. Firstly, it is a typical response that participants found the group content and activities were beneficial to them. They identified writing and exchanging letters, drawing a life tree, and tapping instruments as especially helpful. One participant said, “The themes of the group helped us share different ideas.” Another noted, “Writing and exchanging letters not only offered coping solutions to others but also to oneself.” Secondly, they typically noted group set-up was effective including meeting at regular times and with stable membership and facilitators, preset discussion themes, and group contract. One participant stated, “Meeting at a specific place and time gives me an opportunity to think about some problems clearly which I did not in the past.” Another participant shared, “I felt good in the process of communicating regularly with the same members. This format is different from daily life, and we talked on a deeper level.” Thirdly, participants typically noted the positive roles group members played. They noted that members were willing to help each other, actively participated, openly reflected, expressed, and were serious and conscientious about the group. One participant said, “Group members took it seriously and supported each other sincerely.” Another participant shared, “During group activities, I felt being understood when others got the emotions I wanted to express.”

Participants also identified the limitations in the same three aspects. Firstly, students generally noted that some members were not inclined to express themselves or lacked participation, which may make others feel unsafe in the group. One said, “(some) were not willing to expose in front of others; they prefer not to express their feelings.” Another student said, “(some) are introvert and shy, and have no motivation (to participate).” Secondly, students typically recognized limitations in group content (e.g., themes were overly broad, lack of depth and interest, and some concrete problems were not fully addressed) restricted their group experience. A student said, “The theme was too broad to resonate with some specific (feeling).” Another said, “The theme of life meaning is too overwhelming.” Thirdly, group set-up was variantly reported as restrictive as well. It includes insufficient time duration and session amount (e.g., four times are not enough to fully get involved. It would be better if it was longer and more times), and not fully established relationships among group members (e.g., people tended to hide something and did not fully express; they did not fully disclose their real feelings).

Suggestions for future intervention groups

Participants offered suggestions for providing effective intervention groups for CICS, and their suggestions were about the set-up and content of the group, respectively.

For group set-up, suggestions were made in six areas: namely, setting, meeting times, promotion advertisement, modality of service, language choice, and group activities. Firstly, participants typically suggested that the group setting be convenient, safe, quiet, relaxing, theme-based, and offering Chinese comfort food. One participant said, “It is relaxing in the group without any concerns. We can do activities and eat comfort food.” Another participant noted, “I hope the group can be extended to more people. It provides a social space and a good atmosphere in which folks can eat and chat.” Secondly, students typically suggested meeting frequently at regular times at convenient locations with continuous service. A participant shared that, it would be like a vaccine to have the group started at the beginning of the semester, and continuously meet.” Another participant said, “(I wish the group) could be hosted somewhere close to the dorm.” Thirdly, students typically provided suggestions on advertisement in advance via various platforms to attract more people. One participant suggested, “advertising the service by sending the emails and promoting on Wechat blogs, and letting more people know would be helpful.” Another suggestion was “Advertisement is important. You can organize more social activities and share them (on the platforms).” Fourthly, participants typically supported “combining the growth group and individual counseling service.” Another shared, “both individual and growth group service are necessary. In the growth group, members can discuss together; in individual therapy, clients can receive one-to-one service.” Fifthly, students typically preferred that the service be conducted in Chinese. One participant noted, “service in my native language can provide me great psychological support.” Another participant said, “language itself can influence many people.” Lastly, students variantly suggested group activities being more relaxing, involving more interactive participation between students and facilitators. One participant said,

Facilitators should follow the trend of the era and offer content that resonates with students. It is not a lecture, but more like friendship. We can have more social activities of playing games and communicating, and share with each other concerns and feelings, rather than visiting a doctor or taking a class.

In terms of the content of the group activities, participants offered four specific suggested focuses, namely, emotional regulation (a typical response), interpersonal relationship (a variant response), cultural adaptation (a variant response), and knowledge of mental health (a variant response). Participants shared “(I hope to) learn how to manage self (emotions) through these activities;” “(I hope) this group can help students to relax and mitigate stress;” “themes related to study, social relationships, intimate relationships, and relationships with parents are more attractive;” “the group should help deal with cultural shock, teach better adjustment to the new environment, increase knowledge and understanding, and change the mindset of CICS;” and “(group service should) introduce knowledge to prevent (mental disorders) and change the wrong beliefs.”

Discussion

While scholarly attention has been directed toward CICS’s adjustment to the U.S. higher education context, the application of action research or research-through-service methodologies to this population has been limited. This study addresses this gap by employing such a methodology to identify a specific need, develop and implement a targeted intervention, and subsequently evaluate its efficacy in promoting CICS’s growth and learning. This approach provides a novel framework for both researching and supporting CICS, effectively bridging the divide between understanding their mental health needs and developing effective interventions. The key advantages of this methodology include its emphasis on bridging research and practice, providing direct benefits to the participants, as well as its collaborative nature empowering participants as stakeholders. From an ethical perspective, this action research paradigm reflects a commitment to minimizing the potential for unintended harm, specifically by mitigating the risk of perpetuating negative stereotypes associated with this population (Heng, 2023). Furthermore, this approach may contribute to increased CICS engagement in campus-based mental health initiatives.

The interview study following the intervention provided information toward the identified goals, namely, CICS’s perceived need for psychological support, their perspectives on accessing professional mental health services; the perceived utility of specific components of the intervention, and their recommendations for enhancing the intervention program. These results not only revealed that CICS did experience many challenges that have been reported in the literature, but also allowed us to learn more about CICS’ psychological needs and their thoughts regarding helping seeking and helpful mental health services. Their specific feedback regarding our intervention provided valuable information for future program development to help CICS. Most importantly, the findings supported our assumption that cultural confidence-focused and psychological growth-oriented interventions (vs. problem-focused) are effective modalities for CICS.

Challenges and coping strategies

Participants identified several major challenges they encountered while studying in the United States. Consistent with the existing literature (e.g., Yan and Berliner, 2009), they reported experiences of cultural differences and conflicts, language barriers, social discrimination, and financial worries. These challenges seemed to cause difficulties in their academic work, interpersonal relationships, and daily life activities. Using English as the second language and in a strikingly different cultural context, CICS undoubtedly must overcome significantly more demands and challenges than their domestic counterparts to succeed at college. Moreover, social discrimination could lead to psychological distress and a reduction of opportunities for the targeted people (Fibbi et al., 2021). These findings align with stereotypical portrayals of CICS in existing literature. However, it is crucial to recognize that experiencing challenges is a normal part of the international student experience. What is problematic is the tendency to attribute CICS’s challenges to a lack of ability or competence, thus overlooking the significant impact of cultural adjustment (Heng, 2023). This misattribution can negatively affect CICS’s self-confidence and self-esteem.

According to our participants, CICS have made great efforts to manage encountered larger-than-usual challenges in their own way. Some of them would exercise forbearance and self-regulation to cope with the challenges as much as they can, which are traditionally preferred cultural methods by the Chinese (Wei et al., 2012). Chinese culture emphasizes that emotions be regulated using the individual’s will, which is shown in the tendency of making internal attribution in face of difficulties (Lieber et al., 2000). This attribution tendency may lead to more reliance on self-help and higher hesitation in professional help-seeking. Notably, unlike older Chinese generations who do not accept out-of-family help-seeking or disclose family misery (Wei et al., 2012), our participants also considered sharing their difficulties with trusted others. There may be contributing factors for those who are unwilling to rely on families when suffering. On one hand, it’s typical in Chinese culture that people only share positive updates but not negative ones to avoid making families worry for them. On the other hand, due to the cultural distance, CICS may find it hard for their families to understand their current struggles in context. Thus, CICS would choose to vent and seek help from close and reliable friends. Meanwhile, they also want concrete solutions to their difficulties. Additionally, some CICS wanted the space to express their struggles and related feelings and are eager to increase self-understanding, and even seek professional help when having too serious challenges or self-help had failed. It is clear that this generation of CICS have been influenced by both Chinese traditions and Western cultures.

Perspectives on seeking professional help

In relation to professional help-seeking behaviors, participants reported a general lack of perceived need, even when confronted with various challenges. This reticence may be attributed to CICS’s cultural emphasis on self-reliance, which may discourage the utilization of external professional resources, or to a conceptualization of professional help as being reserved for severe psychopathology. This perspective facilitates a non-pathologizing approach to normative adjustment difficulties, allowing for self-directed coping strategies and reliance on informal support systems. While institutional efforts to address practical concerns such as roommate conflicts, academic advising, and language acquisition are warranted, some participants indicated that existing language programs do not adequately meet their needs. Furthermore, they suggested that diverse dormitory placements, without accompanying intercultural education and preparation, may inadvertently exacerbate adjustment difficulties. These findings underscore the imperative for institutions to provide comprehensive and timely support services, including proactive policies and programs that promote intercultural understanding and mitigate potential sources of conflict.

When reflecting on actual professional help, participants articulated several salient concerns, including the potential for negative social evaluation within their community, and the fear of losing face with accessing counseling services. Participants also expressed apprehension regarding the cultural competence of American counselors, specifically citing concerns about a lack of familiarity with Chinese cultural norms and values. Moreover, the realistic potential for language barriers to impede effective communication between counselors and clients was present. These findings are congruent with existing literature on international student help-seeking behaviors (e.g., Williams et al., 2018) and underscore CICS’s evident ambivalence toward engaging with professional mental health services. While some of these concerns are attributable to the influence of Chinese cultural values and beliefs, others represent more universal anxieties shared by individuals considering seeking psychological assistance. These culturally nuanced concerns present a considerable challenge for universities seeking to provide effective and culturally responsive mental health services that demonstrate a deep understanding of CICS’s social and cultural realities within the context of their studies in the United States.

Benefits from the group

Participants’ self-reports indicated that the intervention yielded positive outcomes that addressed both their practical and culturally relevant needs. These outcomes included the development of new cognitive frameworks for understanding personal challenges, the formation of meaningful interpersonal relationships and support networks, opportunities for emotional expression and the attainment of psychological well-being, and enhancements in problem-solving capacities. Participants specifically articulated that the group experience facilitated deeper levels of reflection and self-understanding, contributing to the adoption of a more positive cognitive orientation. The observed benefits of social interaction and emotional expression within the group context underscore the importance of interpersonal connection, a value emphasized in both Confucian philosophy (Tsui and Farh, 1997) and Western psychological research, which has demonstrated significant associations between social relationships and mental health (Bassett and Moore, 2013).

Participants reported sense of social connectedness is identified as a key component of motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2000) and a mitigating factor against stress (Seppala, 2016), further contributing to positive affect and a sense of empowerment (Chen, 2022). Notably, some participants demonstrated measurable improvements in their problem-solving skills, likely attributable to expanded perspectives, increased social support, and enhanced emotional regulation. These findings resonate with the core tenets of positive psychology (Seligman, 2002) and Fredrickson’s (2001) Broaden-and-Build theory, suggesting that positive emotional experiences can facilitate the expansion of individuals’ cognitive and behavioral repertoires (Fredrickson, 2001) and promote their pursuit of self-actualization (Chan et al., 2006; Seligman, 2002) within the context of their academic and personal lives in the United States.

Suggestions for improving the intervention program

Participants provided actionable recommendations for enhancing the group experience, focusing on content, structure, and outreach. They highlighted the importance of experientially engaging and appealing activities, noting the positive impact of interactive and meaningful experiences. Stable group membership and consistent facilitators were also deemed valuable. To maximize engagement and participation, participants suggested convenient, safe, and relaxing meeting environments; more frequent meetings; and the provision of Chinese food. They also recommended broader advertisement of these services to increase accessibility for CICS. These recommendations offer practical guidance for institutions seeking to develop more effective support programs for CICS, with the goals of improving mental health and promoting greater utilization of available services. Content suggestions included addressing realistic challenges related to emotional regulation, interpersonal relationships, cultural adaptation, and mental health literacy—topics directly relevant to the challenges CICS encounter.

Implications of the study

Participant feedback from the group and subsequent suggestions affirmed the value of adopting a positive, growth-oriented and culture-centered approach, in contrast to a solely problem-focused model, in program development for supporting CICS. Providing them with an opportunity of being with others with similar cultural backgrounds, sharing personal experiences while eating comforting food, and engaging in deeper explorations with peers’ support may enhance participants positive emotions, including relief through self-expression, testing their perceived reality with others in similar situations, and gaining a sense of understanding and emotional connection with peers. This process will facilitate CICS’ deeper understanding of their challenges as well as resources and foster insights into meaning and purpose, resulting in expanded perspectives and enhanced feelings of empowerment.

The findings of this study also provide compelling support for a systematic institutional commitment to fostering a cultural lens in the interpretation of CICS behaviors. It is imperative that these behaviors be understood within a cultural context, recognizing them as reflections of active engagement in the process of cultural adjustment, rather than attributing them solely to individual personality traits or deficiencies. Therefore, the most efficacious form of support for CICS likely involves a deliberate and sustained institutional focus on cultivating transcultural sensitivity and enhancing the overall cultural competence of the educational system.

For mental health services on college campuses, the study results suggest that psychological support should be conceptualized and promoted as a service that fosters well-being and personal growth, rather than solely as a treatment for mental illness or psychopathology. Effective interventions for CICS should explicitly incorporate individuals’ existing strengths and leverage their cultural confidence as valuable resources. Furthermore, these services should provide CICS with structured opportunities for self-exploration, facilitated emotional expression, and meaningful interpersonal interaction with peers, aiming for mitigating stress, cultivating a sense of belonging within the campus community, and fostering the development of positive cognitive and affective perspectives.

Finally, the study results suggest the benefits of using Chinese in intervention programs. A culture-centered approach is undoubtedly enhanced by the use of participants’ native language. Given that CICS constitute one of the largest international student populations on many campuses, the presence of Chinese-speaking counselors and professionals is highly beneficial. In both individual and group interventions, using Chinese can enhance participants’ sense of familiarity, connection, and comfort, leading to increased sharing and active participation.

Limitations and future research

There are several limitations to this study. First, our sample was small, which limited the applicability of the data to understand CICS broadly. Secondly, the group facilitators conducted the interviews, which had the advantage of existing trusting relationships but also the possible disadvantage of demand characteristics, namely the participants knew what the interviewers wanted to hear. Thirdly, the participants’ group experience may have influenced their answers to some of the interview questions. Fourthly, we used Chinese in running the group and conducting the study. When the results are translated into English for presentation, there is an unavoidable loss of richness of the data. It was challenging to precisely portray the meaning of some Chinese words in English. Lastly, even though we used a rigorous qualitative data analysis method (CQR), the effectiveness of it in analyzing qualitative data in Chinese is limited because Chinese verbal communication is often implicit and indirect (Gao and Ting-Toomey, 1998), and it is sometimes hard to capture the meaning between or behind the verbal lines.

Future effort to study CICS experience through action research is strongly encouraged. Group intervention is ideally made available for all CICS, and have it always followed by participant interviews as the interview process itself has the value of being a positive closure as well as a rich source of data. Further potential researcher bias is to be avoided by not having the group facilitators to do the interviews. Finally, qualitative research methods need to be developed for analyzing Chinese interview data. Perhaps regulated interpretation of hidden meaning can be allowed using a consensual approach to address the issue that Chinese communication tends to be indirect and subtle.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Kansas Review Board of Human Subjects Research. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Data were initially collected as part of the intervention program evaluation. When used for this study, the data were considered archival in that no identifiable information was recorded and the individuals who were in the program had graduated and left the university. At the time of the intervention program, participants did sign a generic informed consent form to voluntarily participate in the intervention and allow data for potential research. They were not specifically asked to sign up for this study at that time as we were not focusing on publishing the study. Later, we made a formal application for KU IRB to review our proposed way of using the data for this publication and received approval.

Author contributions

CD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Chinese international students who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aljaberi, M. A., Alsalahi, A., Juni, M. H., Noman, S., Al-Tammemi, A. B., and Hamat, R. A. (2021). Efficacy of interventional programs in reducing acculturative stress and enhancing adjustment of international students to the new host educational environment: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:7765. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157765

Amlashi, R., Majzoobi, M., and Forstmeier, S. (2024). The relationship between acculturative stress and psychological outcomes in international students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 15:1403807. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1403807

Bassett, E., and Moore, S. (2013). Social capital and depressive symptoms: the association of psychosocial and network dimensions of social capital with depressive symptoms in Montreal, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 86, 96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.005

Bonazzo, C., and Wong, Y. J. (2007). Japanese international female students' experience of discrimination, prejudice, and stereotypes. Coll. Stud. J. 41, 631–640.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). “Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials” in Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology. eds. H. C. Triandis and J. W. Berry (Boston, Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon), 89–102.

Chan, C. L., Chan, T. H., and Ng, S. M. (2006). The strength-focused and meaning-oriented approach to resilience and transformation (SMART) a body-mind-spirit approach to trauma management. Soc. Work Health Care 43, 9–36. doi: 10.1300/J010v43n02_03

Chao, C. N., Hegarty, N., Angelidis, J., and Lu, V. F. (2019). Chinese students’ motivations for studying in the United States. J. Int. Stud. 7, 257–269. doi: 10.32674/jis.v7i2.380

Chen, J. (2022). An exploration of relationships between therapist strength-focused, context-focused, and other-focused orientations and psychotherapy outcomes (Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/exploration-relationships-between-therapist/docview/2709041993/se-2?accountid=15172

Ching, Y., Renes, S. L., McMurrow, S., Simpson, J., and Strange, A. T. (2017). Challenges facing Chinese international students studying in the United States. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 473–482. doi: 10.5897/err2016.3106

Choi, I., Mestroni, G., Hunt, C., and Glozier, N. (2023). Personalized help-seeking web application for Chinese-speaking international university students: development and usability study. JMIR Form Res. 7:e35659. doi: 10.2196/35659

Duan, C., Hill, C. E., Jiang, G., Li, D., Li, Y., Zhang, S., et al. (2022). Meaning in life: perspectives of experienced Chinese psychotherapists. Psychotherapy 59, 26–37. doi: 10.1037/pst0000395

Fibbi, R., Midtbøen, A. H., and Simon, P. (2021). “Consequences of and responses to discrimination” in Migration and discrimination (Cham: Springer), 65–78.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 359, 1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Gao, G., and Ting-Toomey, S. (1998). Communicating effectively with the Chinese. Cham: Sage Publications.

Guan, Y., Chen, S. X., Levin, N., Bond, M. H., Luo, N., Xu, J., et al. (2015). Differences in career decision-making profiles between American and Chinese university students: the relative strength of mediating mechanisms across cultures. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 46, 856–872. doi: 10.1177/0022022115585874

Han, X., Han, X., Luo, Q., Jacobs, S., and Jean-Baptiste, M. (2013). Report of a mental health survey among Chinese international students at Yale University. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 61, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.738267

Hegarty, N. (2014). Where we are now: the presence and importance of international students to universities in the United States. J. Int. Stud. 4, 223–235. doi: 10.32674/jis.v4i3.462

Heng, T. T. (2023). Socioculturally attuned understanding of and engagement with Chinese international undergraduates. J. Divers. High. Educ. 16, 26–39. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000240

Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: a practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

IIE. (2023). Open doors report on international educational exchange. Available at: http://www.iie.org/opendoors (Accessed March 5, 2024).

Israel, M., and Batalova, J. (2021) International students in the United States Migration Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/international-students-united-states-2020 (Accessed March 15, 2024).

Kingston, E., and Forland, H. (2008). Bridging the gap in expectations between international students and academic staff. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 12, 204–221. doi: 10.1177/1028315307307654

Lai, H., Wang, D., and Ou, X. (2023). Cross-cultural adaptation of Chinese students in the United States: acculturation strategies, sociocultural, psychological, and academic adaptation. Front. Psychol. 13:924561. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.924561

Lee, J., Kim, N., and Su, M. (2021). Immigrant and international college students’ learning gaps: improving academic and sociocultural readiness for career and graduate/professional education. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2, 100047–103740. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100047

Lei, Y. (2017). The Chinese mental health value scale: Measuring Chinese college students’ cultural values, values of mental health, and subjective well-being (Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/chinese-mental-health-value-scale-measuring/docview/1975367044/se-2?accountid=15172

Li, Z., Heath, M. A., Jackson, A., Allen, G., Fischer, L., and Chan, P. W. (2017). Acculturation experiences of Chinese international students who attend American universities. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 48, 11–21. doi: 10.1037/pro0000117

Liao, X. (2012). Cultural self-confidence: a new dimension of the quality of spiritual life. Qilu Academic Journal 227, 79–82.

Lieber, E., Yang, K. S., and Lin, Y. C. (2000). An external orientation to the study of causal beliefs: applications to Chinese populations and comparative research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 31, 160–186. doi: 10.1177/0022022100031002002

Liu, W., Yu, C., and McClean, H. (2023). Positive psychology in international student development: what makes Chinese students successful? J. Postsec. Stud. Success 3, 81–98. doi: 10.33009/fsop_jpss132933

Lu, X. (2019). What are the most popular majors for international students in the U.S.? Available at: https://www.wes.org/advisor-blog/popular-majors-international-students/#:~:text=Unsurprisingly%2C%20STEM%20majors%20are%20most%20popular%20among%20Chinese,%2817.2%20percent%29%2C%20and%20physical%20life%20science%20%288.4%20percent%29 (Accessed March 15, 2024).

Maleku, A., Kim, Y. K., Kirsch, J., Um, M. Y., Haran, H., Yu, M., et al. (2021). The hidden minority: discrimination and mental health among international students in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Soc. Care Community 30, e2419–e2432. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13683

Mei, L. (2017). Perceptions of academic English language barriers and strategies-interviews with Chinese international students. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1773/38564 (Accessed April 5, 2024).

Mendoza, J. (2016). How international students are changing the 'rich Asian' narrative. Available at: https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2016/0506/How-international-students-are-changing-the-rich-Asian-narrative (Accessed March 25, 2024).

Neupane, D. (2022). Rethinking methodologies: implications for research on international students. J. Teach. Learn. 16, 50–66.

Odinye, I. (2012). Western influence on Chinese and Nigerian cultures. OGIRISI 9, 108–115. doi: 10.4314/og.v9i1.5

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sakız, H., and Jencius, M. (2024). Inclusive mental health support for international students: unveiling delivery components in higher education. Glob. Ment. Health 11:e8. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2024.1

Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Seppala, E. (2016). Connect to thrive: the many benefits of social connection. Available at: https://emmaseppala.medium.com/connect-to-thrive-the-many-benefits-of-social-connection-626d35907179 (Accessed May 5, 2024).

Skinner, M., Luo, N., and Mackie, C. (2019). Are U.S. HEIs meeting the needs of international students? New York: World Education Services.

Smith, T. B., and Sylva, L. (2011). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: a meta-analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 58, 42–60. doi: 10.1037/a0021528

Sue, D., Mak, W. S., and Sue, D. W. (1998). Ethnic identity. In L. C. Lee and N. W. S. Zane (Eds.), Handbook of Asian American psychology (pp. 289–323). Cham: Sage Publications, Inc.

Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Shi, F., Liang, B., Li, X., Wen, J., et al. (2021). Chinese international students in the United States: the interplay of students’ acculturative stress, academic standing, and quality of life. Front. Psychol., 12, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.625863

Tsui, A. S., and Farh, J. L. L. (1997). Where guanxi matters: relational demography and guanxi in the Chinese context. Work. Occup. 24, 56–79. doi: 10.1177/0730888497024001005

Urban, E. L., and Palmer, L. B. (2014). International students as a resource for internationalization of higher education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 18, 305–324. doi: 10.1177/1028315313511642

USC US-China Institute (2021). Chinese students in U.S colleges. Available at: https://china.usc.edu/chinese-students-us-colleges (Accessed June 2, 2024).

Wang, K. T., Heppner, P. P., Fu, C. C., Zhao, R., Li, F., and Chuang, C. C. (2012). Profiles of acculturative adjustment patterns among Chinese international students. J. Couns. Psychol. 59, 424–436. doi: 10.1037/a0028532

Weber, K., Johnson, A., and Corrigan, M. (2004). Communicating emotional support and its relationship to feelings of being understood, trust, and self-disclosure. Commun. Res. Rep. 21, 316–323. doi: 10.1080/08824090409359994

Wei, M., Liao, K. Y. H., Heppner, P. P., Chao, R. C. L., and Ku, T. Y. (2012). Forbearance coping, identification with heritage culture, acculturative stress, and psychological distress among Chinese international students. J. Couns. Psychol. 59, 97–106. doi: 10.1037/a0025473

Williams, G., Case, R., and Roberts, C. (2018). Understanding the mental health issues of international students on campus. Educ. Res. Theory Pract. 29, 18–28.

Xinhua, (2024). China's job market embraces increasing returned overseas students. The state council information office of the People’s Republic of China.

Xiong, Y., Rose Parasath, P., Zhang, Q., and Jeon, L. (2022). International students’ perceived discrimination and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 72, 869–880. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2059376

Xu, C. L. (2021). Portraying the ‘Chinese international students’: a review of English-language and Chinese-language literature on Chinese international students (2015–2020). Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 23, 151–167. doi: 10.1007/s12564-021-09731-8

Yan, K., and Berliner, D. C. (2009). Chinese international Students' academic stressors in the United States. Coll. Stud. J. 43, 939–960.

Zhang, J. (2017). The evolution of China's one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes. J. Econ. Perspect. 31, 141–160. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.1.141

Zhang, S. (2021). Voices of Chinese international students: A critical understanding of their experiences in the United States. San Francisco: University of San Francisco.

Appendix A

Semi-Structured Interview Protocol (probing is allowed)

(1) As a Chinese international college student (CICS) from China living and studying here in the U.S., how do you describe your psychological well-being?

(2) What experiences have you had that had affected your sense of well-being?

(3) How do you manage challenges to your well-being when they arise?

(4) Have you ever sought help from professionals (counselors or psychotherapists on and off campus)?

(5) What are your views regarding using professional mental health service, e.g., counseling service offered by the counseling center on campus.

(6) You recently finished our 4-session growth group experience; What do you think about it?

(7) What are your suggestions for the university to offer mental health service for CICS?

Keywords: Chinese international students, Chinese culture, growth-oriented, mental health, culture-specific

Citation: Duan C, Chen J, Li F, Zhou M, Lin X and Li S (2025) Research through service: Meeting Chinese international college students’ mental health needs. Front. Educ. 10:1412427. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1412427

Edited by:

Weifeng Han, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Enrique H. Riquelme, Temuco Catholic University, ChileSiyu Xu, Dhurakij Pundit University, Thailand

Copyright © 2025 Duan, Chen, Li, Zhou, Lin and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Changming Duan, ZHVhbmNAa3UuZWR1

Changming Duan

Changming Duan Jingru Chen

Jingru Chen Fenglan Li3

Fenglan Li3 Mi Zhou

Mi Zhou Shengnan Li

Shengnan Li