- 1CeIED - Interdisciplinary Research Centre for Education and Development, Lusófona University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 2CeIED - Interdisciplinary Research Centre for Education and Development, Lusófona University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Introduction: This study is part of a cross-cutting and interdisciplinary funded research project involving researchers from different areas - education, sociology and psychology, which aims to contribute to deepening existing knowledge about the relationship between autonomy and curricular flexibility and teacher involvement and well-being. The study presented in this article is justified by the gap found in a Systematic Literature Review carried out in the context of the aforementioned research project. This research aims to understand the challenges posed to leadership based on the relationship between Portuguese educational policies within the scope of Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility developed since 2016 and teacher well-being. To this end, the research is based on the following question: What challenges do leaders face in promoting a school culture in a context of innovation and inclusion?

Methods: This article focuses on a systematic review of reports, recommendations, opinions and independent studies produced in the context of the development of autonomy and curricular flexibility policies in Portugal, published between 2015 and 2023. The selection of documents took into account the websites of the Ministry of Education in Portugal, the National Education Council, all the Teachers’ Unions in Portugal and Transnational Organizations.

Results: The results show that leadership practices based on a collaborative approach and policies that favor teacher autonomy were associated with improved teacher well-being and the development of inclusive pedagogical practices. However, bureaucratization and work overload continue to be significant challenges in teachers’ daily lives. It was also found that the practices of pedagogical leaders can promote innovation and inclusion, requiring continuous institutional support.

Discussion: The results point to the fact that fostering an inclusive and innovative school culture requires leaders to adopt policies that value teacher well-being and promote opportunities for ongoing training. These results are in line with previous research that also points to the importance of a collaborative and supportive environment. The study is a starting point for further research into the relationship between curricular autonomy and teacher well-being.

1 Introduction

School leadership is increasingly seen as a key factor in the collective construction of an inclusive school, i.e., one that is committed to ensuring that each and every student learns. It is also decisive in educational transformation processes, making them meaningful and sustainable to respond to social challenges. To this end, it is necessary to co-create a school culture based on the assumptions of social justice and commitment to the well-being of all those who make up the educational community. This challenge requires recognizing that leadership does not end with the figure of a manager, i.e., top leadership. It is important to note that middle leaders are key players in the implementation of educational policies (Rohlfer et al., 2022). These leaders include department coordinators, cycle coordinators, head teachers, and other middle management positions that act between the school board, teachers, students, and families, as is the case with head teachers. This is because, by acting at the meso level of the system, they have privileged contact with students and parents, promoting communication between the different levels of management and ensuring the implementation of educational policies on the ground (Chang, 2016).

Leadership practices are therefore a privileged object of study for analyzing the implementation of educational policies within the framework of school autonomy (Lima, 2021). This is because leadership is not a single concept, since it is not consensual in the scientific community and has undergone various transformations in its meanings from the end of the 20th century to the present day (Nye, 2009). Similarly, leadership styles are diverse. For example, transactional leadership uses approaches and rules to recognize individual achievements, developing actions that “are based on reward, punishment and self-interest” (Nye, 2009, p. 90). From the perspective of transactional leadership, “the leader only indicates the behaviors to adopt and the objectives to achieve, without influencing or motivating the followers to pursue the desired goals” (Castanheira and Costa, 2007, p. 144). On the other hand, transformational leaders “inspire and empower their followers, using moments of conflict and crisis to awaken their consciences and transform them” (Nye, 2009, p. 89), appealing to the collective interest. At the same time, distributed leadership is based on a collaborative approach, in which responsibility and decision-making are shared between different agents in the educational community, which favors the active participation of all (Spillane, 2006). Instructional leadership prioritizes direct support for teachers and a focus on pedagogical and curricular strategies (Hallinger, 2009). It is also worth mentioning laissez-faire leadership, is characterized by a leader who “does not exhibit typical leadership behaviors, avoiding making decisions and abdicating responsibility and authority” (Antonakis et al., 2003). As a result, the exercise of leadership is limited to solving problems only when they get worse (Bass and Riggio, 2006).

Leadership styles are not “mutually exclusive,” since many “leaders use both styles at different times and in different contexts” (Nye, 2009, p. 91). It is about influencing people through a process of communication, mobilizing experience to make decisions, which requires the application of each of their styles depending on the situation, based on the interaction between the educational community and leaders (Estanqueiro, 2019). Thus, the concept of leadership adopted in this work is based on direction, team building, and actions that can inspire the educational community by example and word of mouth (Adair and Reed, 2006). Leaders can influence and mobilize subjects to create a sense of community, based on a holistic view of the context and practices based on collaboration. This can move everyone in the educational community toward a collective contract to guarantee the learning of each and every student (Fullan, 2020). These are leaders who involve the entire educational community in sharing values with a view to the common good and innovation (Bao, 2024).

In line with the conception of Estêvão (2000), leadership practices must be related to the new demands of the current organizational environment, taking into account the construction of horizontal relationships about hierarchy, with new political concerns that support decision-making based on democracy and autonomy. In this understanding, leadership does not consist of mobilizing others to solve problems whose solutions are previously known but rather supporting the educational community in solving problems that have never been solved (Fullan, 2020). In this way, the exercise of leadership requires a comprehensive vision of the context and the objectives for its development, which results from a transparent and dialogued process, through the articulation of the perspectives of the subjects of the educational community, who are part of a network of formal and informal, internal and external contacts (Rego and Cunha, 2004). They must therefore consider the planning and implementation of a vision, starting with the establishment of a strategy to achieve it. In addition, building a network of people who agree with and can achieve the vision is fundamental, but it is also necessary to motivate the members of the educational community to achieve this vision (Kotter, 2017).

With this in mind, it is important to co-construct dynamics of commitment and collaboration with a view to professional development (Faizuddin et al., 2022) and teacher agency. In this sense, it is assumed that the dialog between theory and practice, in a collaborative way in the processes of teaching and learning and professional development, constitutes a space for transforming subjects and contexts (Northouse, 2018). This can be co-constructed by establishing partnerships with other educational agents who can contribute to enriching teachers’ knowledge. For example, partnerships between schools and universities can give shape to lifelong learning processes, as an opportunity for transformation and emancipation of the subjects in the educational context (Contreras, 2003; Vieira, 2013). Another possibility for professional development lies in Pedagogical Supervision practices when based on a culture of teacher collaboration in the context of a Learning School (Alarcão, 2009), as a factor for change and renewal of educational practices (Vale et al., 2024). These dynamics, when developed based on the assumptions of learning communities (Bolívar and Segovia, 2024), can contribute to a culture that serves teachers’ personal and professional well-being.

According to Aziri (2011), job satisfaction includes psychological, physiological, and environmental conditions and factors that ensure positive feelings toward work, increasing productivity, and a sense of well-being (Dami et al., 2022). Hongying (2007), for his part, presents five factors that point to the perception of satisfaction with teaching work: school management, teaching, colleagues, performance, and career progression prospects. At the same time, Molero et al. (2019) add to these factors relationships with students, organizational aspects, lack or absence of resources, and low self-esteem.

It is important to note that the benefits of well-being are not only limited to the subjects but are also related to the development and maintenance of relationships between teachers and students, contributing to a positive learning climate (Dreer, 2023). In other words, teacher well-being plays a central role both in the school environment (Matos et al., 2022) and in promoting learning (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009).

In this context, leadership practices must be based on a process of reflection-action (Schön, 1983), which can be understood as a dimension of agency. This is a concept commonly used to explain the social action of those who, for a specific reason, decide to act on something to bring about change (Zadok et al., 2024). Although it is used in different scientific contexts, in an educational context it can be related to the action of its agents, as vectors of change and active contributors to educational reforms (Priestley et al., 2015).

In terms of transformation, the Portuguese education system underwent a significant curriculum changes between 2016 and 2018. This was marked by the introduction of legislative measures and public policies aimed at promoting inclusion, autonomy, and curricular flexibility and combating school failure (Diario da Republica, 2016, 2018a,b). In 2016, the National Program to Promote School Success (PNPSE) (2016) was created, to promote equity, improve the quality of teaching, and reduce school failure rates. In 2017, the Pedagogical Innovation Pilot Projects (PPIP) began, which stood out for introducing experimental practices in school clusters, to eliminate school dropouts through flexible management of 100% of the curriculum. Committed to the holistic development of each and every student, based on education for democracy, the National Strategy for Citizenship Education (Monteiro et al., 2017) was drawn up to train active, critical, and aware citizens.

This period saw the start of the Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility Project (PAFC), in which 226 school groupings and non-grouped schools took part. This gave each educational setting the possibility of managing up to 25% of the curricular workload, adapting teaching to its specific needs. After evaluating the implementation of this project in the form of a pedagogical experiment, this curricular changes culminated in the enactment of Decree-Laws 54/2018 (2018a) and 55/2018 (2018b), both of July 6 (Diario da Republica, 2016, 2018a,b). Decree-Law 54/2018 deepened the understanding of inclusion as an essential element of education, ensuring that each and every student is supported in their learning process, regardless of their individual needs. Decree-Law 55/2018 strengthened schools’ curricular autonomy, allowing them to adapt the curriculum to their specific realities to promote learning by managing up to 25% of the curriculum.

This set of educational policies that embody Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility is based on the vision of an education system that values inclusion and equity. The focus is on providing students not only with academic knowledge but also with skills and attitudes that culminate in the competencies set out in the curriculum document Profile of Students Leaving Compulsory Schooling (Martins et al., 2017). These include critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving; as well as ethical, cultural, and social values for an education that recognizes students as active citizens in an ever-changing society.

The implementation of this educational policy in the context of autonomy and curricular flexibility has been evaluated through studies that highlight its positive impacts on curriculum articulation, teacher collaboration, and the diversification of teaching methodologies. The recent legislative changes have highlighted, especially through the evaluation of this policy, the importance of “monitoring leadership strategies and their impact on the empowerment of actors and institutions as systematically as possible (.)” (Cosme et al., 2021, p. 106).

This political-educational scenario summons school contexts to the challenge of promoting learning for each and every one of their students through an agency inserted at a micro level of “curricular management autonomy” (Lima, 2020, p. 187). This implies the ability to the degree of power of given individuals or groups - especially individual teachers or the governing bodies of schools - in determining what students will learn (Morgado and Sousa, 2010, p. 371).

In this context of increasing autonomy and accountability, the role of leadership is crucial to the success and sustainability of educational reform (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2021). However, we cannot ignore the fact that this scenario makes teaching work more complex, which can be a challenge to teachers’ well-being if they are not offered the necessary conditions for the full professional exercise of their duties (Duong et al., 2023). The results presented in the Eurydice Report (2021) indicate that Portuguese teachers are the most stressed at work. In this sense, it recommends that policies aimed at improving teacher well-being should seek to strengthen teamwork and collaboration within schools, developing social and interpersonal skills and teachers’ sense of autonomy in their work.

Through a systematic review process, this article aims to understand the challenges posed to leadership based on the relationship between Portuguese educational policies in the field of Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility and teacher well-being. Recognizing the diversity of leadership styles and the crucial role that principals and middle leaders play in guiding educational processes, the research in this article is based on the following question: What challenges do leaders face in promoting a school culture in a context of innovation and inclusion?

2 Methods

This study was conducted as part of a cross-cutting and interdisciplinary funded project involving researchers from different fields - education, sociology, and psychology - and different generations. The aims of the Project in development is to contribute to deepening existing knowledge about the relationship between autonomy and curricular flexibility and teacher engagement and well-being. This article, which is an excerpt from the aforementioned project, focuses on a systematic review of reports, recommendations, opinions, and independent studies produced in the context of the development of autonomy and curricular flexibility policies in Portugal. It followed the ethical guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of CeiED, the research center that includes the authors.

A systematic review is a review that has the explicit intention of being conducted systematically (Okoli, 2015). It is thus a methodical and comprehensive approach to identifying, selecting, and critically evaluating relevant documents on a specific topic to answer a well-defined research question (Gonçalves and David, 2022; Manterola et al., 2013). In this sense, systematic reviews are an opportunity to synthesize a specific topic from the evidence available from primary sources. Considering the object of this research, the systematic review is an opportunity to synthesize the relationships between autonomy curricular flexibility, and teacher well-being, supporting the understanding of the challenges posed to leadership. It is hoped that the evidence arising from this systematic documentary review can assist decision-making in different sectors, including those responsible for formulating educational policies.

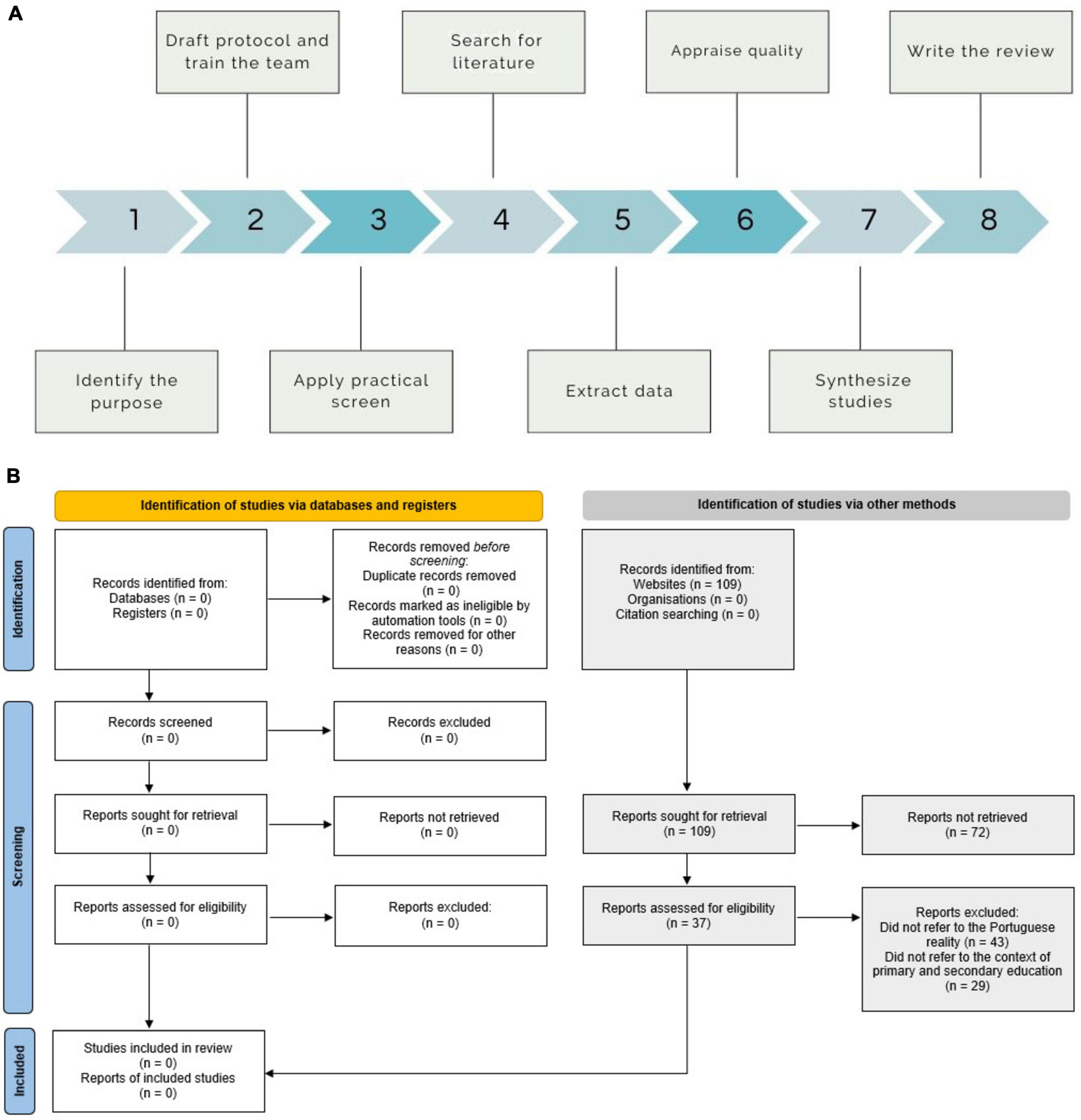

The systematic review carried out in this article was based on the eight stages of Okoli’s (2015) model, shown in Diagram 1, which represents the progression of its various stages.

With the aim (Stage 1) of understanding the challenges posed to leadership based on the relationship between Portuguese educational policies in the field of Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility and teacher well-being, a protocol for the systematic review (Stage 2) was planned collectively with the research team. The process included several researchers to guarantee impartiality and reliability. The definition of the protocol was based on the concern to ensure consistency in the execution of the review, in addition to the adoption of methods that improve transparency and reproducibility when conducting systematic reviews (Polanin et al., 2020). In this sense, the protocol was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Pigott and Polanin, 2020), given their potential to promote clear and complete documentation of reviews and to help readers better understand the methods, results and conclusions of the review (Moher et al., 2009; Page et al., 2021).

After taking on the PRISMA protocol, the documents to be submitted to the systematic review process were selected (Stage 3). This study is justified by the gap found in a Systematic Literature Review1 carried out by searching databases, taking into account our research object. This gap is related to a temporal issue that implies a gap between the recent implementation of the education policy in 2018 and the development and publication of scientific productions. In addition, as this is an educational policy, it is important to analyze the documents issued by the Ministry of Education, as well as other entities that directly or indirectly influence the development of educational policies, but which are not included in research. In this way, a systematic review of reports, recommendations, opinions, and independent studies allows for a more in-depth look from other angles, subjects, and perspectives.

Therefore, the documentary selection for this research was based on a search for various publications made between 2016 and 2023 on the websites of the Portuguese Education Authority (Directorate-General for Education, Ministry of Education), the National Education Council and Transnational Organizations (European Commission, OECD, UNESCO). To ensure that the research was comprehensive, external evaluations relating to the education policy under study were also analyzed, as well as documents inherent to the projects promoted by the Ministry of Education in this area, in addition to documents issued by the various teachers’ unions in Portugal (Step 4). The selection of documents used combinations of the following terms: autonomy, curriculum, flexibility, and well-being. Of the 109 documents found, including reports, recommendations, opinions, and independent studies, 30 national and 7 international publications were selected. The exclusion criteria centered on not referring to the Portuguese reality and/or the context of primary and secondary education, as they did not concern the subject of this research. The process of analyzing each record to identify compliance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria was carried out independently by two researchers so that a consensus analysis could be defined. No automation tools were used at any stage of the research process. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) provides an overview of the search, screening, and identification procedures used in this review.

Figure 1. (A) The eight stages of Okoli’s (2015) model. (B) PRISMA flow diagram.

A full-text review was carried out on these 37 studies, and there were no documents that did not meet the inclusion criteria we defined or that included criteria for their exclusion. The data collection process was carried out independently by three researchers and then a consensus analysis was defined by two other researchers.

Thus, the selected documents (which consider the context of Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility in Portugal) were subjected to content analysis (Step 5) based on emerging categories. The analysis presented in the next section is guided by the category of teacher well-being, from an interpretative and qualitative perspective (Step 7), based on three subcategories, namely:

(i) Pedagogical practices: For the challenges posed in terms of promoting collaborative work and sharing experiences, practices, methodologies and materials and their impact on diversifying classroom practices. Also, the environment experienced in the school and its relationship with higher levels of teachers’ psychological well-being.

(ii) Teacher Training: The challenges posed by the professional development of teachers and their relationship with well-being.

(iii) Performance Appraisal/Professional Development: Because of the challenges posed by promoting self-reflection on professional development needs and monitoring teaching staff, to improving their practices and ensuring their professional and personal well-being.

Alongside the emerging subcategories, the recommendations for promoting teacher well-being will be analyzed. Given that the 37 documents analyzed were issued by official bodies, there was no exclusion due to insufficient quality (Step 6). Finally, this article responds to Step 8, i.e., the description of the systematic review process itself, with a view to transferability.

2.1 Synthesis

The documents that make up the systematic review presented in this article are summarized in the Supplementary Data Sheet, which gathers the information related to the aim of this research. The following information was compiled in a spreadsheet for each article: (a) Theme, (b) Year, (c) Organization/Institution, (d) Authors, (e) Title, (f) Description, (g) References. The themes fall into the 3 emerging categories described above.

3 Results

The results will be presented based on the three dimensions that emerged from the systematic analysis, namely: Pedagogical Practices, Teacher Training, and Performance Evaluation/Professional Development. At the end, recommendations on promoting teacher well-being will also be presented.

3.1 Pedagogical practices

To develop the analysis, we will first explore the relationship between pedagogical practices and the well-being- of teachers in the various documents consulted.

One of the main pedagogical practices that is mentioned as a positive influence on teachers’ well-being is sharing and helping each other. In this sense, the evaluation study of Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility (Cosme et al., 2021) highlights that 53.6% of teachers consider it essential to share experiences, practices, methodologies, and teaching materials. At the same time, moments of discussion and pedagogical reflection present themselves as an opportunity to promote diversification in teaching and learning strategies and act as a social support mechanism between teachers. This collaboration is identified as an aspect related to improved job satisfaction and continuous professional development.

On the other hand, increased bureaucratization and work overload are mentioned in the documents as aspects that have negatively affected teachers’ well-being. The accumulation of administrative responsibilities, along with the perceived length of curriculum documents, lack of resources, and disinterest on the part of students, are other factors identified as having the potential to aggravate teachers’ physical and mental fatigue (Cosme et al., 2021; Varela et al., 2018). Likewise, the pressure to fulfill tasks unrelated to teaching practices is recognized as contributing to increased stress and emotional exhaustion among teachers. In this sense, a study carried out in 2018 by the National Federation of Teachers on the social organization of work in school education in Portugal, to understand teacher illness, indicates the need for a “redefinition of the teaching function and the structure and content of teaching, namely about programs and methods, in addition to demands for improved salaries and benefits” (Varela et al., 2018, pp. 76–77). It also highlights the impact of bureaucracy on teachers’ well-being: From a planned and more democratic school, both for teachers and students, we move on to a bureaucratized school that is immovable in its organization, in order to sustain maximum flexibility - immune to pressure from its main players - accompanied by total unpredictability. The worst of both worlds - petrified and solitary management, widespread social flexibility. For those in charge, almost absolute power, for those who exercise it, almost total submission (Varela et al., 2018, p. 81).

We cannot ignore the societal and global challenges that can affect the dynamics of teaching professionalism. Although “the teaching profession [was] already, before the COVID-19 pandemic, exposed to high levels of stress” (Matos et al., 2022, p. 322), we highlight the unprecedented challenges brought to the school environment by the pandemic crisis and, consequently, transferred to pedagogical practices. In this context, teachers have felt the impact of the pandemic on their professional lives, reporting lower levels of life satisfaction and well-being. In addition, an increase in psychological and psychiatric symptoms is also identified. There was also a perception among teachers of receiving less support from management and colleagues in the school context, which intensified the feeling of isolation and helplessness (Matos et al., 2022). The pandemic has not only hampered the development of teaching practices, but has also highlighted pre-existing problems, such as the lack of resources, especially digital resources, and the need to adapt quickly to distance learning technologies.

Assertive communication and support from school management and colleagues emerge as critical factors for teacher well-being. A solid support network in the school environment, made up of both colleagues and leaders, is fundamental for promoting well-being and reducing stress. Such action allows teachers to deal with the challenges posed by the profession, and to respond to the needs of each and every student, adapting teaching methodologies, especially during the pandemic (Matos et al., 2022). Teacher well-being, as a priority, should always be considered in education policies, to promote a healthy environment that favors teachers’ professional development. To this end, it is important to consider that the factors that contribute to stress and the emergence of states of anxiety and depression in teachers identified by the scientific literature in this area involve age, teaching experience, remuneration, qualifications, workload and the psychological demands of the job (Matos et al., 2022, p. 328).

Regarding age, “the most recent Eurostat data indicate that, at the EU level, almost 40% of lower secondary school teachers are aged 50 or over, and less than 20% are under 35” (Varela et al., 2018, p. 32). The experience is important to support teachers at the start of their careers, to prevent them from leaving the profession. It’s about offering guidance and mentoring according to the needs identified and the challenges faced. In this sense, having career prospects can be an important motivating factor for building a dynamic and evolving career path that can help make the teaching profession more attractive to young graduates (Varela et al., 2018).

Based on the challenges posed to teachers, teaching practice requires action that goes beyond the simple transmission of information. Teachers are expected to contribute to the holistic development of each and every student, taking into account and responding to individual differences through collaboration with other educational actors (Matos et al., 2022). However, these challenges for teachers hurt their well-being, bringing perceptions of emotional exhaustion and a certain demotivation. This is particularly true of teachers who say they don’t receive adequate support from the educational environment, which implies a feeling of being unable to meet the expectations of the school, parents, and community.

Another important aspect mentioned in the documents consulted is the fact that, compared to other professionals, teachers are part of a population at risk in terms of well-being when it comes to developing mental health problems (Matos et al., 2022). Stress and burnout have a direct impact on teachers’ ability to provide quality education, thus affecting student success. Likewise, teachers at advanced levels of burnout are more likely to be absent from their duties, which entails entropy in the education system.

In this context, the documents consulted point to the fact that coping strategies and the exercise of resilience are fundamental to teachers’ well-being. Those who develop coping mechanisms tend to report better results in terms of both well-being and teaching practices (Matos et al., 2022). On the other hand, a lack of adequate training and a sense of isolation are factors that worsen their well-being.

In short, the results point to collaborative teaching practices and institutional support as crucial factors for teacher well-being. In contrast, bureaucratization, work overload, and new demands, such as those imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, are aspects that have compromised teachers’ well-being. Therefore, the development of resilience strategies combined with better working conditions are opportunities to guarantee teachers’ well-being.

3.2 Teacher training

Considering the second dimension that emerged from the systematic review, we will explore the aspects that relate teacher training to its influence on teacher well-being. It is important to consider various aspects that are directly related to the quality of training, continuous professional development, the development of pedagogical possibilities for adapting to teaching contexts, and strategies for teacher well-being.

Bearing in mind that “initial and in-service training represent two sides of a purpose that is intended to complement each other to train teachers for the educational challenges that circumstances demand” (Faria et al., 2020, p. 61), it is essential that this is a process that promotes not only scientific and pedagogical skills but also ethical aspects and participation in the school community. This is because, as mentioned in the previous dimension (pedagogical practices), teaching is a complex act that goes beyond the mere transmission of information. As such, the continuous development of teachers is essential to respond to the educational and social challenges facing a school that wants to be inclusive. In this sense, initial and ongoing training can help teachers feel prepared to face the challenges of the profession and, consequently, less vulnerable to stress, which can lead to greater levels of well-being. In this context, continuous teacher training is recognized as a complementary element to initial teacher training (Faria et al., 2020), from a lifelong learning perspective. This process of continuous learning can ensure that teachers not only keep up to date but also develop greater resilience in the face of the adversities they face in their profession.

As this is a profession whose training does not end with initial training, the documents consulted highlight the importance of knowledge associated with teaching practice. This is because “the specific knowledge of teachers, being practical knowledge, is developed and revealed in practice, hence the importance of training in context, and the privileged context of teacher practice is the classroom” (Faria et al., 2020, p. 63). Without ignoring the fact that theoretical training is essential in building teacher professionalism, articulation with real educational contexts is mentioned as a positive strategy for developing the knowledge teachers need. This helps teachers to reflect on and devise responses to the daily challenges faced in the classroom. This requires interpretation and action tailored to each situation faced, contributing to the construction of a personal pedagogical repository. This repository can be enriched by both individual and collective experiences through sharing with other teachers (Faria et al., 2020).

Since there is recognition that professional knowledge is developed in interaction with peers, “the importance of training with and among peers” is highlighted (Faria et al., 2020, p. 63). This training developed in a collaborative context can support the process of reflection on action, allowing teachers to revisit their practices in the light of new theories and methodologies. In this understanding, the environment based on a culture of mutual support is identified as fundamental to teacher well-being (Faria et al., 2020), because it acts as a support mechanism, reducing the sense of isolation and overload that many teachers feel when carrying out their duties.

The impact of ongoing training is highlighted by teachers, and its importance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is evident. This is because the abrupt need to transition to distance learning was less impactful for teachers who already had previous training in the areas, proving to be a decisive factor for their well-being (Matos et al., 2022, p. 323). This context underlines the importance of training in line with new technologies and emerging needs so that teachers can respond to unpredictable situations.

In summary, teacher training is identified in the documents consulted as a central element in the development of teaching skills and teacher well-being. Initial and ongoing training is recognized as an opportunity for teachers to develop strategies so that they can face the challenges posed by the exercise of their functions. The promotion of collaborative contexts between teachers, which value the sharing of experiences and practices, stands out for creating healthier educational environments that are conducive to professional and personal growth.

3.3 Performance evaluation/professional development

For an analysis of teacher performance evaluation and teachers’ professional development and its relationship with well-being, it is essential to identify the impact of performance evaluations on the improvement of teaching practices, continuous professional development, and teachers’ well-being.

The Eurydice Report (2023) Structural indicators for monitoring education and training systems in Europe - 2023: The teaching profession identifies performance evaluation as an opportunity for teachers’ continuous professional development. It’s about understanding performance appraisals as a space for dialogue to identify training needs, turning appraisals into an opportunity for growth and improvement. This is because, by identifying gaps and priority areas for training, each educational context will be able to design training offers tailored to local needs, directly contributing to the success of each and every student. In addition, the specialized support offered after evaluations is also identified as an aspect that promotes teachers’ confidence in their pedagogical choices, which in turn influences their well-being and job satisfaction. This scenario is also related to teacher retention, since those who feel supported in their professional development tend to stay in their careers, reducing teacher turnover (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023).

Another point of note in the Eurydice Report (2023) is the direct link between career progression or salary progression and the teacher performance evaluation process. That is when evaluations are directly linked to career progression or salary increases, teachers have an additional incentive to become more actively involved in their professional development. Thus, the model of linking performance to career growth is widely advocated by bodies such as the OECD (2013), as it provides concrete motivation for teachers to continually strive in their teaching practices. Such an incentive not only contributes to the development of teacher performance but is also a long-term driver of motivation. Recognition for a job well done, through promotions or salary increases, generates a sense of appreciation that contributes to teachers’ well-being and their desire to continue in the profession. This is because the feeling of career stagnation and the lack of prospects for professional growth contribute to the development of symptoms of emotional exhaustion and job dissatisfaction. In this sense, the Eurydice Report (2023) highlights the importance of creating a culture of constructive evaluation, which offers meaningful feedback and opportunities for growth. This has the potential to reduce stress and increase job satisfaction. Teachers who feel that their appraisals are focused on their personal and professional development, rather than being merely bureaucratic or judgmental processes, are more likely to experience a sense of well-being in their working environment. In short, the aforementioned report points to the need to implement educational policies that assume teacher performance evaluation as an integral part of teachers’ professional development and well-being. As such, educational institutions and those responsible for formulating government education policies should consider creating training programs tailored to the needs revealed by the results of performance evaluations.

3.4 Recommendations on promoting teacher well-being

In this section, we will highlight the recommendations for promoting teacher well-being, based essentially on two documents published in the period under review, namely the recommendations of the National Education Council and those contained in the Report of the Observatory of Psychological Health and Well-being: Monitoring and Action promoted by the Ministry of Education in Portugal.

The recommendations show concern that teacher well-being be incorporated systemically into educational policies and practices. These recommendations address both the need to reformulate initial and in-service training practices and the implementation of institutional strategies to ensure long-term well-being. In addition, they refer to the need to promote self-care and the well-being of teachers and the school community, through various strategic actions. Bearing in mind that teacher stress is a recurring problem in schools, the recommendations also stress the importance of creating environments that prevent or mitigate this problem. Among the strategies suggested are:

– Active participation of the different players in the school community, such as students, parents, and teachers in projects and activities. Furthermore, it is important that this involvement also includes decision-making, taking into account the collective construction of a sense of belonging. This can contribute to co-creating a more balanced educational environment, which influences teachers’ levels of well-being, as they feel more involved and supported by their communities.

– Greater autonomy and curricular flexibility so that teachers can manage the organization of content and the dynamics of their classrooms. In this sense, autonomy is referred to as a central factor for well-being, as it provides greater scope for decision-making and authorship over one’s work, resulting in a significant stress reduction.

– The provision of spaces for self-care in schools and activities to strengthen interpersonal relationships between teachers, managers, and other education professionals. These spaces and group activities are fundamental for promoting self-care and creating a support network within the school, as well as enabling the design of strategies for reconciling work and family life.

– Promoting ongoing training in the area of well-being, so that teachers can develop tools to deal with crises, support stress management and promote well-being, through strategies that allow them to organize their routines and responsibilities, balancing professional demands with personal life. From another perspective, training courses are also opportunities for forward-looking planning aimed at meeting the needs of the context. To this end, it can integrate the needs of the different teacher recruitment groups, anticipating future challenges and creating appropriate responses collectively. It is worth mentioning the recommendation that ongoing training be integrated into teachers’ timetables, to promote teachers’ ongoing professional development without overburdening them.

– Articulation between the University and educational contexts through the establishment of protocols, with the valorization of teachers who act as cooperating supervisors during internships in initial training. This should be complemented by continuous monitoring of teachers during their initial career, as suggested by replacing the probationary period with a real induction year.

– Reducing the workload of teachers with more years of service to prevent burnout. The CNE (Ramos, 2016) suggests reducing teachers’ workload or the number of students per class, so that they can concentrate on teaching, learning, and assessment processes.

– Revaluing the teaching career, both professionally and socially, by improving working conditions and seeking consensus on solutions to the challenges faced by teachers.

These recommendations seek to create a more sustainable education system, where teachers are empowered to deal with the challenges of teaching and feel that they are in an environment that supports their well-being and professional development.

4 Discussion

Promoting an innovative and inclusive school culture involves creating a collaborative environment where teachers feel supported and have opportunities for professional development. The results indicate that pedagogical practices based on sharing and mutual support between professionals are fundamental to teachers’ well-being and the diversification of teaching and learning strategies. However, challenges include bureaucratization and work overload, which can reduce the time available for collaboration and pedagogical reflection (Varela et al., 2018).

In this sense, dialog with the educational community is one of the challenges facing leaders, requiring a deep and holistic view of the context. Co-creating a school culture based on horizontal and assertive communication is a challenge that requires overcoming hierarchical barriers that can hinder pedagogical innovation. Thus, in line with Chang’s (2016) thinking, leaders must act as intermediaries between the school and the community, encouraging the implementation of actions that promote inclusion.

Therefore, the need to systematically monitor and evaluate leadership practices and their impact on school culture is fundamental. As Cosme et al. (2021) point out, leaders must develop strategies that drive innovation and ensure that all voices in the educational community are heard and valued. However, this is not an innate process, requiring leadership practices that tackle resistance to change and the complexity of curriculum management (Lima, 2020; Morgado and Silva, 2019).

In terms of teaching practices, leaders need to encourage a culture of sharing. This could guarantee what is stated in Recommendation No. 3/2019 of the National Education Council, within the margin of autonomy that leadership has, that teachers have time and space for collaborative work. This scenario implies a reassessment of school organization and the creation of regular moments for collective reflection on action (Schön, 1983). In addition, tools need to be made available to help overcome or minimize bureaucratic and workload demands, which could help achieve more innovative and inclusive teaching practices.

The pressure to fulfill administrative tasks combined with the lack of support from the leadership directly influences teachers’ levels of well-being. The obstacles placed in the way of managing teachers’ working time jeopardize their ability to focus on implementing diverse and inclusive pedagogical practices rather than bureaucratic tasks. In this sense, the results show that teachers who report greater institutional support, both from colleagues and leadership, cope better with the challenges of the profession (Matos et al., 2022).

In line with the perspective of Dami et al. (2022), teacher well-being is related to teacher satisfaction and student learning. Therefore, the complexity of educational reforms and the increase in teachers’ responsibilities may be related to the promotion of stress, compromising innovation and inclusion. Lack of adequate resources and insufficient support from leadership can lead to lower levels of engagement and motivation (Duong et al., 2023), hindering the implementation of innovative pedagogical practices.

With this in mind, leaders face the task of creating conditions that promote teacher well-being, which implies developing policies and actions that strengthen teamwork and collaboration (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021). Since, as presented by Matos et al. (2022), the lack of support from leadership implies a sense of isolation for teachers in terms of well-being, creating a support network in the educational context could help reduce this sense of isolation and the emotional exhaustion of teachers. This pathology can lead to teachers facing burnout and not being able to carry out their duties, making it a challenge for leaders. It is therefore important for leaders to implement strategies to combat work overload and offer continuous emotional and professional support, especially after periods of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results analyzed show that initial and ongoing teacher training is fundamental to meeting educational challenges, while lifelong professional development, which combines theory and practice, is seen as essential (Northouse, 2018). However, the lack of relevant ongoing training that is appropriate to needs, especially in contexts of rapid change (such as distance learning), has been highlighted as a factor that aggravates teacher stress.

Promoting opportunities for teachers’ professional development based on a culture of reflection-action (Schön, 1983) requires an ongoing commitment from leaders to encourage teachers’ professional development (Faizuddin et al., 2022). This involves not only technical training but also strengthening pedagogical knowledge and interpersonal relationships, which are essential for building a positive school climate. One opportunity lies in establishing partnerships between schools and universities, based on the recognition that teaching and training are possibilities for the transformation and emancipation of those involved in education (Contreras, 2003; Vieira, 2013).

Promoting teachers’ professional development involves strategic planning on the part of the leadership, taking into account a training offer that meets both curricular requirements and emerging ones, such as the use of new technologies. In addition, promoting a collaborative culture (Fullan, 2020), where teachers share experiences and knowledge, can be an opportunity to foster innovation and inclusive teaching practices.

In this context, performance evaluation, when seen as an opportunity for teachers’ continuous professional development, can motivate them to improve their teaching practices, increasing their levels of well-being. However, the results show that, in some contexts, performance evaluation can be perceived as a bureaucratic and stress-generating process, especially if it is directly linked to career progression or salary incentives (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023).

Leaders face the challenge of implementing a culture of constructive evaluation, based on dialog and the assumptions of a Learning School (Alarcão, 2009), which goes beyond judgment. One opportunity lies in Pedagogical Supervision processes, including in the context of School-University articulation, which could enhance better pedagogical practices (Vale et al., 2024). By making performance evaluation a formative process, that identifies training needs and offers specialized support, leaders can turn evaluation into a tool for promoting well-being and innovation. This process also helps to retain teachers keep them motivated, and to create a more inclusive and innovative school environment.

About the challenges related to promoting a culture of well-being, the recommendations included in the systematic review point to the need for institutional strategies that incorporate teacher well-being into the policies and practices of the educational context. The involvement of the whole community, the relationship between teachers, the co-creation of spaces for self-care, and curricular flexibility are important aspects of building a balanced educational environment (Dreer, 2023). In addition, the promotion of greater autonomy for teachers is seen as a central factor for their well-being and for the innovation of their teaching practices.

It is therefore up to leaders to foster a culture of well-being and autonomy, which includes promoting the active participation of all the actors in the educational community in decision-making (Bao, 2024). This can help increase a sense of belonging and motivation for innovation. Leaders also need to ensure that teachers have the flexibility to adapt their pedagogical practices according to the needs of each and every student, which is essential for creating an inclusive environment.

5 Conclusion

Creating a context that favors inclusion requires a collaborative approach, the motivation and well-being of teachers, as well as a continuous and collective commitment to reflection and action. Recent educational changes in Portugal offer a margin of autonomy for the construction of pedagogical practices adjusted to the needs of the context but require leaders to assume themselves as active agents in the implementation of changes that prioritize the well-being of all members of the educational community. Promoting an inclusive and innovative school culture presents multifaceted challenges for leaders, whose actions must focus on managing change, and inspiring and mobilizing all those involved. Although these challenges are presented in any style of leadership, we are aware that the design of specific ways to overcome them will depend on the interaction and communication between leaders and the community and decision-making experience (Estanqueiro, 2019).

Based on the systematic review discussed in this article, we recognize that one of the main limitations centers on a certain dependence of the documents analyzed on secondary sources and studies that have already been published. This may not fully reflect the specific realities and challenges of different educational contexts. Bearing in mind that Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility are a recent educational policy in Portugal, it is not yet possible to access longitudinal studies that could provide a more in-depth view of the influence of pedagogical leadership in promoting teacher well-being over time. It should be noted that our intention to gain an in-depth understanding of a specific context - in particular the Portuguese context - is an option that conditions comprehensiveness and generalization.

Overall, the results of the systematic review suggest relevant implications for leadership practices, taking into account the promotion of a school culture. The collective construction of a collaborative environment, concerned with the continuous professional development of teachers, can directly influence levels of teacher well-being and pedagogical practices themselves. However, the implementation of these practices requires an institutional commitment from the pedagogical leadership, taking into account structural issues such as bureaucratization and work overload. To create a truly inclusive and innovative environment, leaders must prioritize, within the margin of autonomy they have, the reduction of administrative tasks, creating conditions that foster collaboration between teachers.

Promoting innovative pedagogical practices, based on mutual support and ongoing training, also requires significant organizational changes. This includes reviewing educational policies at the central and school levels to guarantee time and space for pedagogical reflection, as well as providing tools to help overcome bureaucratic barriers. The implementation of policies that value teacher autonomy and well-being must be accompanied by the promotion of a culture of constructive evaluation, focused on the continuous development of teachers.

On a political level, the results of this study point to the need for policies that recognize the importance of teacher well-being as a key factor in educational success. Similarly, in-service training policies should consider technical, pedagogical, emotional, and relational training, taking into account the challenges of practicing the profession.

With this in mind, public policies should prioritize the co-creation of an inclusive school culture, involving all members of the educational community. This implies bringing leadership closer to the real needs of teachers and students and giving teachers greater autonomy to adapt their teaching practices to the realities of the context.

The systematic review carried out is a starting point for further research, especially in areas that have been little explored, such as the influence of curriculum changes on teachers’ mental health and innovation processes. In this context, longitudinal studies that track the effects of leadership practices over time can provide insights into the role of pedagogical leadership in creating collaborative and innovative environments.

Another area that could be explored is the relationship between performance evaluation and teacher well-being, particularly in contexts where the evaluation system is strongly linked to career progression and financial incentives. It may also be relevant to understand how evaluation processes can be tools for professional development and the retention of teachers in schools.

In short, it is essential to recognize that promoting an inclusive and innovative school culture depends on a delicate balance between curricular autonomy, institutional support, and the continuous development of leadership and teachers. Although the challenges are complex, the results of this study indicate that a collaborative approach, centered on the well-being and professional development of teachers, can be a promising way to build a more equitable educational environment. Continued research and adaptation of educational policies will be essential to consolidate these practices and respond to emerging challenges in the global educational landscape.

Author contributions

LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. EE: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. RD: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The project has the reference COFAC/ILIND/CeiED/1/2023 and was supported by ILIND and FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the entire team involved in this research project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1520947/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ Two members of the project took part in the ECER 2024 International Congress, Education in an Age of Uncertainty: memory and Hope for the Future, held in the city of Nicosia (August 27–30), presenting two papers: “Times of Change and times of change: a study of the relationship between curricular autonomy and teacher engagement and well-being “and - Curricular autonomy, work engagement and teacher well-being: A systematic review” where the scarcity of systematic reviews of reports, recommendations, opinions and independent studies was demonstrated.

References

Alarcão, I. (2009). Formação e supervisão de professores: Uma nova abrangência. Rev. Ciências Educ. 8, 119–128.

Antonakis, J., Avolio, B., and Sivasubramaniam, N. (2003). Context and leadership: An examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Leadersh. Q. 14, 261–295. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(03)00030-4

Bao, Y. (2024). The effect of principal transformational leadership on teacher innovative behavior: The moderator role of uncertainty avoidance and the mediated role of the sense of meaning at work. Front. Educ. 9:1378615. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1378615

Bolívar, A., and Segovia, J. (2024). Comunidades de práctica profesional y mejora de los aprendizajes. Barcelona: Editorial Grao.

Castanheira, P., and Costa, J. (2007). “Lideranças transformacional, transaccional e laissez-faire: Um estudo exploratório sobre os gestores escolares com base no MLQ,” in A Escola sob suspeita, org M. Jesus and C. Fino (Porto: ASA).

Chang, Y.-Y. (2016). Multilevel transformational leadership and management innovation: Intermediate linkage evidence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 37, 265–288. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-06-2014-0111

Contreras, J. (2003). A autonomia da classe docente. Coleção Ciências da Educação Século XXI. Porto: Porto Editora.

Cosme, A., Ferreira, D., Lima, L., and Barros, M. (2021). Avaliação externa da autonomia e flexibilidade curricular: Decreto-lei n° 55/2018: Relatório final 2018-2020. Lisboa: Direção Geral da Educação.

Dami, Z., Imron, A., Burhanuddin, B., and Supriyanto, A. (2022). Servant leadership and job satisfaction: The mediating role of trust and leader-member exchange. Front. Educ. 7:1036668. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1036668

Diario da Republica. (2016). Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.° 23/2016, de 11 de abril. Available online at: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/analise-juridica/resolucao-conselho-ministros/23-2016-74094661 (accessed September 15, 2024).

Diario da Republica. (2018a). Decreto-Lei n° 54/2018, de 6 de julho. Available online at: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/54-2018-115652961 (accessed September 15, 2024).

Diario da Republica. (2018b). Decreto-Lei n° 55/2018, de 6 de julho. Available online at: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/55-2018-115652962 (accessed September 15, 2024).

Dreer, B. (2023). On the outcomes of teacher wellbeing: A systematic review of research. Front. Psychol. 14:1205179. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1205179

Duong, A., Nguyen, H., Tran, A., and Trinh, T. (2023). An investigation into teachers’ occupational well-being and education leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ. 8:1112577. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1112577

Estanqueiro, A. (2019). Saber lidar com as pessoas. Princípios da comunicação interpessoal (27a ed.). Oeiras: Editorial Presença.

Estêvão, C. (2000). “Liderança e democracia: O público e o privado,” in Liderança e estratégia nas organizações escolares, org J. Costa, A. Mendes, and A. Ventura (Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro), 35–44.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2021). Teachers in Europe: Careers, Development and Well-being. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2023). Structural indicators for monitoring education and training systems in Europe – 2023: The teaching profession. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Faizuddin, A., Azizan, N., Othman, A., and Ismail, S. (2022). Continuous professional development programmes for school principals in the 21st century: Lessons learned from educational leadership practices. Front. Educ. 7:983807. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.983807

Faria, A., Santana, I., Figueiral, L., and Ferro, N. (2020). Recomendação n.° 3/2019, de 31 de julho. Recomendação sobre qualificação e valorização de educadores e professores dos ensinos básico e secundário. Available online at: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/recomendacao/3-2019-123610607 (accessed September 15, 2024).

Fullan, M. (2020). The nature of leadership is changing. Eur. J. Educ. 55, 139–142. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12388

Gonçalves, I., and David, Y. (2022). A systematic literature review of the representations of migration in Brazil and the United Kingdom. Comunicar 30, 49–61. doi: 10.3916/C71-2022-04

Hallinger, P. (2009). Leadership for 21st century schools: From instrutional leadership to leadership for learning. Hong Kong: Institute of Education.

Hargreaves, A., and Fullan, M. (2021). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hongying, S. (2007). Literature review of teacher job satisfaction. Chin. Educ. Soc. 40, 11–16. doi: 10.2753/CED1061-1932400502

Jennings, P., and Greenberg, M. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to child and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Lima, L. (2020). Autonomia e flexibilidade curricular: Quando as escolas são desafiadas pelo governo. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Educacional, (Especial). 172–192. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.34632/investigacaoeducacional.2020.8505 (accessed September 15, 2024).

Lima, L. (2021). Assembleia da República. Comissão de Educação, Ciência, Juventude e Desporto. Audição pública “O Regime de Autonomia, Administração e Gestão dos Estabelecimentos Públicos da Educação Pré-Escolar e dos Ensinos Básico e Secundário” (23 de fevereiro de 2021), Lisbon.

Manterola, C., Astudillo, P., Arias, E., and Claros, N. (2013). Systematic reviews of the literature: What should be known about them. Cirugía Española 91, 149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cireng.2013.07.003

Martins, G., Gomes, C., Brocardo, J., Pedroso, J., Carrillo, J., Silva, L., et al. (2017). Perfil dos alunos à saída da escolaridade obrigatória. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação.

Matos, M., McEwan, K., Kanovskı, M., Halamová, J., Steindl, S., Ferreira, N., et al. (2022). Compassion protects mental health and social safeness during the COVID-19 pandemic across 21 countries. Mindfulness 13, 863–880. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01822-2

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

Molero, M., Pérez-fuentes, M., Atria, L., Oropesa, F., and Gázquez, J. (2019). Burnout, perceived efficacy, and job satisfaction: Perception of the educational context in high school teachers. Hindawi BioMed Res. Int. 1. doi: 10.1155/2019/1021408

Monteiro, R., Ucha, L., Alvarez, T., Milagre, C., Neves, M. J., Silva, M., et al. (2017). Estratégia nacional de educação para a cidadania. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação.

Morgado, J., and Silva, C. (2019). “Articulação curricular e inovação educativa: Caminhos para a flexibilidade e a autonomia,” in Currículo, inovação e flexibilização, org J. Morgado, I. Viana, and J. A. Pacheco (Santo Tirso: De Facto Editores), 129–148.

Morgado, J., and Sousa, F. (2010). Teacher evaluation, curricular autonomy and professional development: Trends and tensions in the Portuguese educational policy. J. Educ. Policy 25, 369–384. doi: 10.1080/02680931003624524

OECD (2013). Synergies for better learning: An international perspective on evaluation and assessment, OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in education. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264190658-en

Okoli, C. (2015). A guide to conducting a standalone systematic literature review. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 37, 879–910.

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Pigott, T., and Polanin, J. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: High-quality meta-analysis in a systematic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 90, 24–46. doi: 10.3102/0034654319877153

Polanin, J. R., Hennessy, E. A., and Tsuji, S. (2020). Transparency and reproducibility of meta-analyses in psychology: A meta-review. Persp. Psychol. Sci. 15, 1026–1041. doi: 10.1177/1745691620906416

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. London: Bloomsbury.

Ramos, M. (2016). Recomendação n.° 1/2016, de 19 de dezembro. Recomendação sobre a condição docente e as políticas educativas. Available online at: https://www.cnedu.pt/pt/noticias/cne/1133-recomendacao-a-condicao-docente (accessed September 15, 2024).

Rego, A., and Cunha, M. (2004). A essência da liderança: Mudança x resultados x integridade: Teoria, prática, aplicações e exercícios de autoavaliação. Lisboa: Ed. RH.

Rohlfer, S., Hassi, A., and Jebsen, S. (2022). Management innovation and middle managers: The role of empowering leadership, voice, and collectivist orientation. Manag. Organ. Rev. 18, 108–130. doi: 10.1017/mor.2021.48

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Basic Books.

Vale, A., Coimbra, N., Martins, A. O., and Oliveira, J. (2024). “The teaching profession and the renewal of pedagogical practices in higher education in times of the pandemic,” in Fostering values education and engaging academic freedom amidst emerging issues related to COVID-19, eds Y. Waghid and Z. Gross (Leiden: Brill), 19–25.

Varela, R., Santa, R., Silveira, H., Coimbra de Matos, A., Rolo, D., Areosa, J., et al. (2018). Inquérito nacional sobre condições de vida e trabalho na educação em portugal. Available online at: https://www.spn.pt/Media/Default/Info/22000/700/0/0/Relat%C3%B3rio%20-%20Estudo%20sobre%20o%20desgaste%20profissional%20(2018).pdf (accessed November 28, 2024).

Vieira, F. (2013). A experiência educativa na formação inicial de professores. Atos Pesquisa Educ. 8, 593–619.

Keywords: pedagogical leadership, curriculum autonomy, curriuculum flexibility, teacher well-being, teacher professional development, pedagogical practices, teacher training

Citation: Lima L, de Oliveira Martins A, Estrela E and Duarte RS (2024) Challenges posed to leadership: systematic review based on the relationships between curricular autonomy and teachers’ well-being. Front. Educ. 9:1520947. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1520947

Received: 31 October 2024; Accepted: 15 November 2024;

Published: 12 December 2024.

Edited by:

José Matias Alves, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, PortugalReviewed by:

Marília Favinha, University of Évora, PortugalLuísa Carvalho, Polytechnic Institute of Portalegre, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Lima, de Oliveira Martins, Estrela and Duarte. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louise Lima, bG91aXNlLmxpbWFAdWx1c29mb25hLnB0

Louise Lima

Louise Lima Alcina de Oliveira Martins

Alcina de Oliveira Martins Elsa Estrela

Elsa Estrela Rosa Serradas Duarte2

Rosa Serradas Duarte2