- Interdisciplinary Center for Educational Innovation (CIED), Universidad Santo Tomás, Santiago de Chile, Chile

Conversations about hate speech are a complex issue. It is not a new problem; on the contrary, society has been confronted with hate speech against specific communities at different moments. The present study aims to investigate the beliefs of Chilean teachers working in teacher education and their relationship with hate speech that may have occurred in their practice. The methodology was quantitative. The participants were 200 teachers. The data collection instrument was a survey to determine teachers’ beliefs. The results showed that teachers expressed concern about the problem and stated that action must be taken to combat hate speech. At the same time, they argued that their colleagues perpetuate and reproduce hate speech in their practice, which is also a complex situation that needs to be addressed. Finally, there is also a controversy about the limits of freedom of expression.

1 Introduction

The United Nations (UN) gives us an interesting definition of what we could consider hate speech, emphasizing the pejorative and discriminatory nature of such expressions. The UN Strategy and Plan of Action (2019) defines hate speech as “any type of communication, whether oral or written, —or also behavior— that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language about a person or group based on what they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color, ancestry, gender or other forms of identity (United Nations, 2019). Similarly, Aguado Odina et al. (2022) indicate that hate speech represents a communicative action that generates hostile environments for certain people, groups, and/or communities. Hate speech generally refers to statements that question the dignity of people based on their characteristics, individually and collectively, in communities. Such statements express hostility towards an ‘other’ through violent performative discourse, both implicitly and explicitly.

Legal regulation is not an easy task. Pégorier (2018) emphasizes that one of the most frequently faced difficulties is the complexity of respect for human dignity and freedom of expression. This aspect represents the complexity of the legislation for the various states. In particular, virtual communication platforms lack responsibility in establishing control mechanisms around the multiple expressions of hate (Carlson, 2021). For education, it is fundamental that hate speech is not punishable as it is normalized and naturalized in classroom practice. The complexity lies in the overlap between freedom of expression and statements that aim to marginalize and create violence. The understanding of freedom of expression as a fundamental right for democracy and the construction of citizenship.

2 Theoretical framework

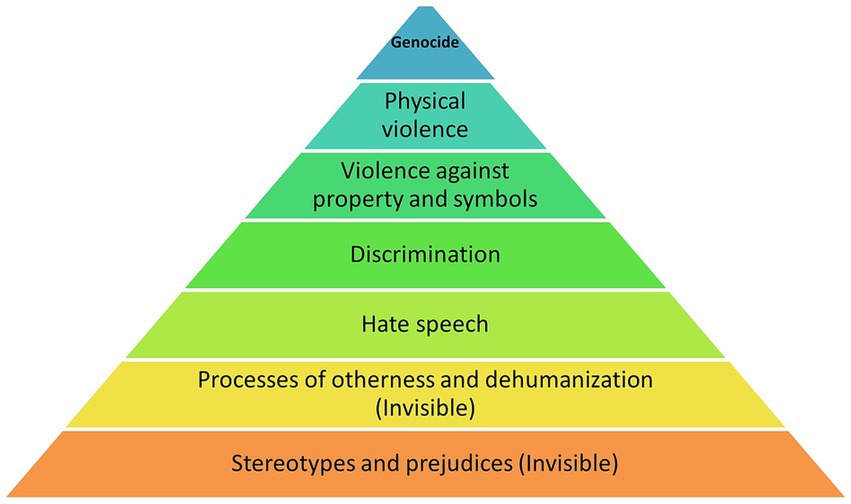

Haider (2020), Mata Benito (2011) and Osuna and Olmo Pintado (2019) suggest that expressions of hatred could be represented graphically in a “hate pyramid (Chart 1).”

Hate speech is thus based on previously shared and reproduced ideas and beliefs that justify inequality based on a false understanding of diversity. Waldron (2012) states that the harmful effects of this type of speech occur on a psychological, social, and political level, which is one of the problems that freedom of expression must address.

Garcés (2020) argues that we are witnessing a paradoxical moment concerning the political-ideological system. On the one hand, freedom of expression is a well-earned asset for democracies and citizens. On the other hand, this freedom is used for anti-democratic purposes and under a logic that aims to discriminate, dehumanize, violate, and marginalize many people based on the characteristics of their identity. Moreover, Rogero (2019) and Aguado Odina et al. (2022) argue that it is necessary to dismantle the processes that activate, produce, and reproduce them through education. In general, violence and inequalities emerge from such processes, which must be prevented and eliminated from all spaces without losing the right to freedom of expression.

According to Parodi et al. (2022), most hate speech occurs in digital spaces. The internet can express written hate messages through images, videos, and other mechanisms. In general, people in vulnerable situations are most often victims of hate speech, which poses a threat to people’s safety and trust. It is essential to consider that what happens online also happens in offline spaces. Above all, be aware of the false myth of anonymity and impunity on the networks. Many people who spread hate through such channels rely on the false idea that they are “protected” on the internet by anonymity and the void scope of the law. This situation is erroneous since many laws sanction the expressions and actions of hate on the networks and allow us to track who spread them, when, and where. Some of the main examples of online harassment and hate are (a) making threats, insults, or racist, sexist, or class-based comments; (b) attempting to infect a person’s computer with viruses; (c) flooding a person’s email inbox with hate messages; (d) spreading false information about a person; (e) mocking a specific person; (f) sharing images of a person without their consent; (g) promoting the exclusion of a person both online and offline; (h) constantly sending violent, offensive and discriminatory messages.

Aguado Odina et al. (2022) note that hate speech is based on a sexist, racist, classist, ableist, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, and LGTBQphobic logic, among others, that permeates the characteristics that constitute such dehumanizing expressions. Thus, we understand that hate speech is a “socially living issue” (Izquierdo Grau, 2019), from which we must understand the discursive practices under which such expressions of hatred are constructed and transmitted. It is necessary to recognize that such practices and discourses are not neutral but respond directly to what Freire (2015) has indicated, namely that education not only imparts knowledge but is also a political act.

Paz et al. (2020) and Emcke (2017) agree that education, especially teachers, should not limit themselves to denouncing hatred and violence as forms of expression that harm people but should also provide the conditions to make visible and understand the mechanisms, spaces, and dynamics under which they are produced, reproduced, and disseminated. Giorgi and Kiffer (2020) propose an in-depth analysis of the hate politics in society, which can profoundly affect classroom situations. Mouffe (1996) proposes One possible solution is to deepen democratic logic. She suggests radicalizing democracy as a political and ideological system where such expressions would have no place.

Aguado Odina et al. (2022) and Waldron (2012) agree that the expressions of transferred hatred are based on unequal social constructions that have historically been used to marginalize, exclude, discriminate, and violate other people and communities. In this context, they propose a series of indicators that could be used in educational spaces to identify, prevent hate, and build counter-narratives:

a. Raising awareness through counter-narrative or alternative discourse campaigns. The aim is to communicate ideas to as many people as possible.

b. Education. Mainly through curriculum reforms, textbooks, and school and career profiles.

c. Training. Mainly to:

• Empower potential victims with information about their rights, the laws, and the resources available to defend themselves within the legal system fully.

• Training of state institutions as guarantors of fundamental rights, mainly law enforcement and security forces, judiciary members, the legislature, and the importance of international frameworks aimed at preventing and regulating expressions of hate.

• Initial and ongoing training of teachers. The aim is to provide teachers with the tools and skills to work with these issues in the classroom.

a. Reporting. Provide sufficient knowledge to make appropriate reports when confronted with hate speech (both under national and international law).

b. Reporting on social networks. Provide communities with the knowledge to report all expressions of hate on social networks, both on the networks in which they participate and those experienced by others. Social networks offer mechanisms to make such reports.

c. Monitoring. Maintain control over the collection of information and actions related to hate speech. This is done to maintain a database that allows educational and social strategies to be developed in light of past experiences to promote the prevention and eradication of such messages.

d. Support. Legal systems must be available to victims in particular. This support must include legal counsel, judicial and social representation, and psychological and psychiatric support.

e. Advocacy. Carry out actions and campaigns aimed at the authorities so that they can take measures to prevent, condemn, and combat hate crimes and hate speech. Political actors, in particular, should actively promote human rights and eradicate hatred and intolerance.

f. Daily actions. People must be fully committed to preventing, eradicating, and combating hate speech and crimes of all kinds. This must be implemented daily, from a simple conversation with neighbors to education in the family, neighborhood, and community, among other instances.

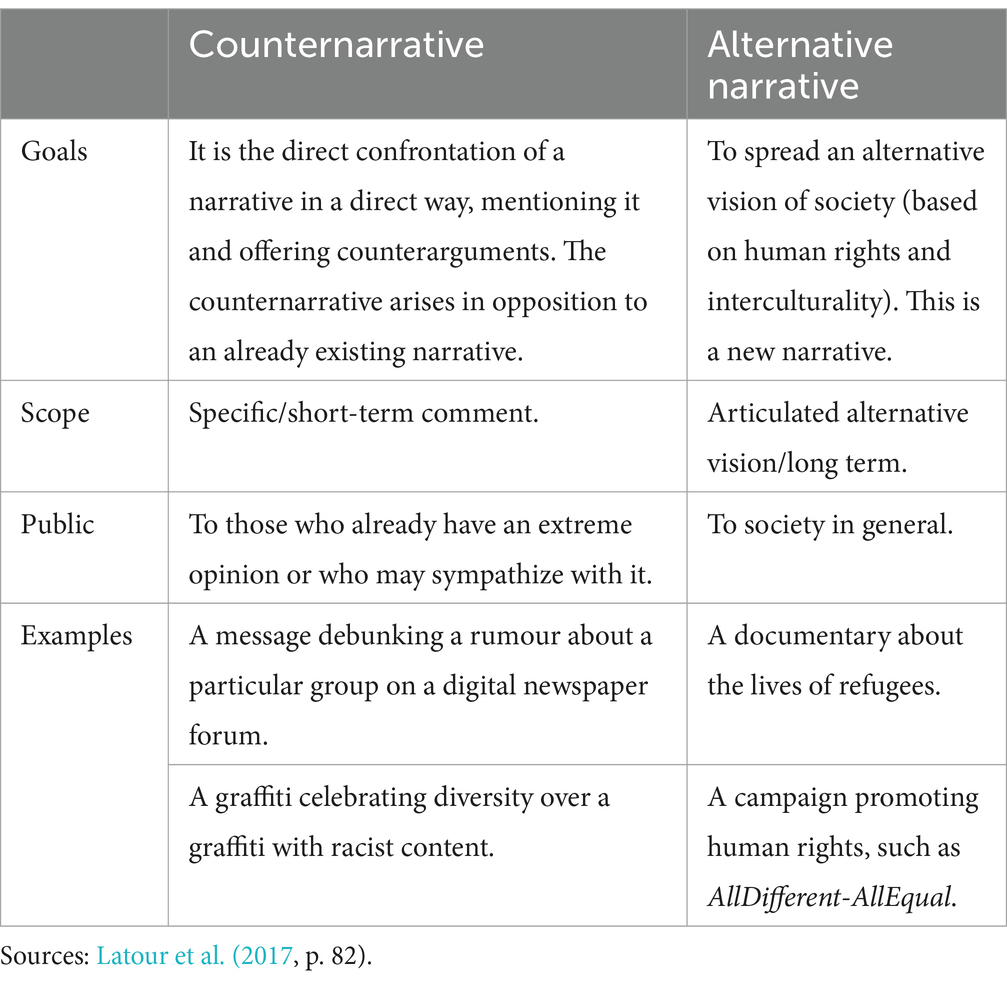

To prevent hate speech and hate crimes, it is essential to combat the stereotypes and prejudices that underlie such expressions. From a didactic perspective, we can consider counter-narratives and alternative narratives as educational strategies. The first step is to understand the intolerance behind such expressions (Massip Sabater et al., 2021). Counter-narratives are narratives constructed against something, while alternative narratives are not reactive but purposeful (Latour et al., 2017). Table 1 describes these strategies in more detail:

While counter-narratives can be used in the short term and reactively, the development of alternative narratives responds to stories that contain an articulated vision that can be developed over a more extended period. Counter-narratives can feed alternative narratives. Denouncing injustices and discriminatory messages is not enough; solutions must also be found. In this sense, any message directed against hate speech must be based on human rights as a fundamental goal for society and people.

Aguado Odina et al. (2022) and Latour et al. (2017) provide some general criteria for the development of counter-narratives or alternative narratives:

a. No hate or violence. Counter-narratives and alternative narratives must never contain hatred against groups or explicit or implicit incitement to violence.

b. The foundation is human dignity. Counternarratives and alternative narratives must be based on human beings’ inalienable dignity.

c. Personal positioning. It is necessary to reflect on one’s positioning and prejudices before speaking out in defense of victim groups.

d. Do not generalize or point out new scapegoats. Generalizations about groups should not be used, and schemes that encourage the search for new “scapegoats” should not be reinforced by using arguments based on diverting attention from one group to another (“The problem is not the immigrants, but the politicians”).

e. Be aware of who your audience is. Your target audience is not people with extreme opinions but the so-called “silent majority.”

f. Not just data. While data is critical to combating hate speech, empathy is essential in the fight against such speech.

g. Critical thinking. The best response to hate is to encourage critical thinking and balanced and constructive dialog. Challenging extreme arguments and introducing new ideas and viewpoints that encourage questioning are necessary.

3 Methodological framework

The present study uses a quantitative methodology within the positivist paradigm (Cohen et al., 2013). In this paradigm, the researcher separates himself from the reality that shapes the object of study to discover realities and formulate probabilistic generalizations that enable their prediction. Generally, a hypothetical-deductive model is followed to establish causal relationships between concepts that are contrasted and verified in representative samples selected using sampling techniques. They usually work with modalities that imply experimental control through techniques that facilitate the collection of information in large quantities, objective tests, scales, questionnaires, and systematic observation (Bisquerra and Alzina, 2004).

We understand the positivist paradigm (Latorre et al., 1994) as it focuses on explaining, predicting, and controlling phenomena and objects of study, thus establishing regularities that are part of the phenomenon under study. We, therefore, rely on a positive understanding of reality, which states that the world is objective and independent of the people who know it. It includes logical phenomena that can be described through systematic observation and scientific methods that help us to propose explanations and descriptions of the phenomena we study (Bisquerra and Alzina, 2004; Cohen et al., 2013).

There is a clear distinction between subjects and objects, and the social world is understood to be similar to the natural world. The regularities in this social world are explicit in cause-effect relationships and show that events do not occur randomly (Ortega-Sánchez, 2023). Therefore, the proposed quantitative method uses an exploratory-descriptive survey study approach. We follow what Cohen et al. (2013) indicate and where such a method is helpful for researchers as it allows us to describe situations, events, and facts and explain how they are manifested.

The description helps us because we seek to measure and evaluate concepts and variables that are part of our study’s definitions. The description provides a way to obtain information about what we want to study, delimit the sample, the method of data collection, the registration, and the subsequent analysis (Cardona Moltó, 2002). López-Roldán et al. (2015) The quantitative methodology allows us to approximate causal relationships and measure reality objectively. All this can lead to generalizations that can help us explain social phenomena.

We define the objectives of this research in two areas:

a. Identifying the beliefs prevalent among teachers regarding gender-based hate speech in teacher education programs.

b. Characterizing the beliefs of professors in teacher education regarding hate speech from a gender perspective.

3.1 Instrument

We ensure the validity of the instrument based on the definitions of Manheim and Rich (1999) who recommend combining three factors: internal, external, and statistical validity. In such definitions, we are helped by the approaches Krippendorff (1990) where internal validity refers to the fact that the indicators and variables fulfill the possibility of establishing causal relationships. External validity refers to the possibility of making generalizations. Statistical validity, where the criterion ensures the relationship between the instrument’s reliability and the statistical analysis, where sample size, normality, and homoscedasticity, among others, can be replicated through multivariate techniques (Lynch, 2013). The Cronbach Alpha Index was applied to ensure the reliability of the instrument. The literature (Cohen et al., 2013) indicates that a factor of 0.7 is high for studies in the social sciences. In this study, we obtained a factor of 0.84.

3.2 Information gathering techniques

The Within the framework of quantitative methodology with a descriptive-exploratory approach Álvarez-Gayou (2003), descriptive studies usually use developmental, longitudinal, cross-sectional, cohort, survey, and observational designs. Given our research objectives, we consider it appropriate to use a survey design using a self-administered questionnaire. The self-administered survey allows the respondents to receive the questionnaire and instructions via indirect contact, facilitating answering the questions as people can do this when it suits them (De Leeuw, 2004).

The survey and questionnaire strategy is beneficial because it follows a subject-centered approach, where information is obtained by applying the instrument to people. Such an application pursues the goal of representativeness of the sample in the broader universe (Castellvi et al., 2023). Hence, it is one of the most commonly used and recommended strategies by different authors (Font Fábregas and Pasadas del Amo, 2016).

Bisquerra and Alzina (2004) suggest that descriptive research and survey studies are typical of the initial stages of research development and can usefully prepare the way to establish new research. Thus, survey studies allow us to collect information from subjects by formulating questions and estimating population inferences from the results of a given sample.

Font Fábregas and Pasadas del Amo (2016) state that the most essential characteristics of the survey method include the following:

a. The information is obtained by indirectly observing the facts from the people interviewed.

b. It allows for massive applications, extending the results to communities using sampling techniques.

c. The researcher’s interest does not lie in the specific subject who answers the questionnaire but in representing the population to which he or she should belong.

d. It allows the collection of data on different topics.

e. The information is collected in a standardized way through a questionnaire, which allows for comparisons between all of them and, thus, exports and contrasts with other similar research.

For the construction of the instrument, Díaz de Rada (1999) suggests the following factors:

a. Desired level of data quality.

b. Budget.

c. Content of the questionnaire, including the number and type of questions and alternative answers.

d. Time for application.

e. Type of universe under study.

Among the main advantages and disadvantages of the survey strategy (Font Fábregas and Pasadas del Amo, 2016), we can mention:

a. It allows you to cover a wide range of topics.

b. Facilitates the comparison of results.

c. The results of the study can be generalized, considering the selected sample.

d. It makes it possible to obtain meaningful information.

e. A high level of information is obtained with little economic and time expenditure.

We can comment on the disadvantages:

a. It is unsuitable for studying populations with communication difficulties.

b. The information is limited to the person’s statements.

c. The interviewer’s presence can cause reactive effects on the answers.

d. The lack of context and life references limits the interpretation of survey data.

e. The existence of physical obstacles makes contact with sample units difficult.

f. The development of a comprehensive survey is complex and expensive.

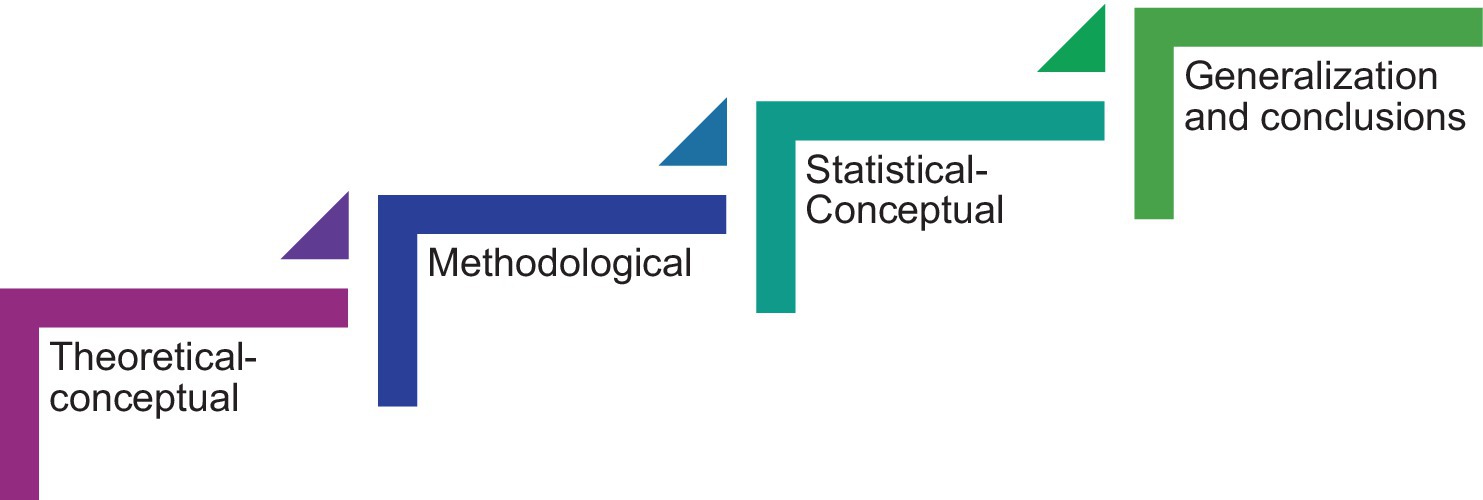

For the research process, we considered the approaches of Cohen et al. (2013) who defined four development phases in Figure 1. At the first level, the objectives and problems of the study are set out. At the second level, we determine the sample selection and the definition of the variables to be studied. At the third and fourth levels, the pilot questionnaire is prepared. Its formulation leads to the statistical level, where conclusions and generalizations can be drawn and conclusions made after coding and analyzing the data.

Figure 1. Theoretical-conceptual process. Source: Own elaboration based on Cohen et al. (2013).

To ensure compliance with the study objectives, we adapted the phases of survey research proposed by Cohen et al. (2013) and presented them in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Phases of survey research. Source: Own elaboration based on Cohen et al. (2013).

3.3 Sample

In choosing the sample, we considered Bisquerra and Alzina's (2004) the statement that the units of analysis and content must be defined and delimited, including where they are located and the time available to develop the study with the population. The type of sampling was non-probabilistic for convenience (Cohen et al., 2013), given the possibility of access and the objectives proposed in the study. The selection of those who are part of the sample is not subject to probability. However, it refers to other criteria related to the study’s objectives or the requirements of the person who selects the sample. Therefore, it is essential to consider the ease of access to the sample and the willingness of the individuals to participate in the research (Castellvi et al., 2023).

For the above, we formed a sample of 200 teachers. The age range of the participants was between 30 and 44 years (65%). The gender distribution was quite homogeneous (55% of individuals identified themselves as women and 45% as men; there was no response to the other variable). In addition, the largest % of participants graduated after 2000 (83% of respondents).

3.4 Data analysis

We used statistical techniques to analyze the data, allowing us to represent teachers’ beliefs based on a numerical study (Castro Posada, 2001). Quantitative analysis implies that the numerical data, using variables, correlations, and observation units, allow inferences based on statistics since the theoretical elements are converted into numerical values (Castro Posada, 2001).

From this perspective, statistics provides objectivity to studies, as we can make exhaustive and controlled measurements since the researcher maintains a distant relationship with the object of study (Castellvi et al., 2023). In quantitative methodology, the study process follows a hypothetical-deductive method in which relationships between data and concepts are established. This leads us to the fact that we can make representations of the data from statistics as an axis for generalizing the conclusions to a broader population (Font Fábregas and Pasadas del Amo, 2016).

Creswell (2014) suggested that the analysis should be conducted from an external perspective and attempts not to change the study’s context. In this way, data collection was carried out without interfering with reality. This information was then analyzed through an experimental procedure that aims to objectify the conclusions drawn from the analysis as much as possible.

3.5 Ethical criteria

The instrument was submitted for approval by the Scientific Ethics Committee in its final version and was accepted in Letter/Report No. 23-2024. The Santo Tomás Scientific Ethics Committee was accredited by Resolution of the Ministry of Health No. 23136643/2023.

4 Results

We will divide the results into two sections to answer the objectives. First, we will present teachers’ beliefs about hate speech from a gendered perspective in the context of their practices. The data comes from Part 1 of the instrument. In the second part, we will address a characterization of the same beliefs expressed by teachers in their practices as expressions of hate. Similar to the first analysis, the characterization will emerge from the responses to the multiple-choice questions, as the goal was to explore the subjectivities to arrive at a subsequent characterization of the beliefs.

4.1 Teachers’ beliefs about gender-based hate speech in the context of initial teacher training

It is interesting to note that 52% of teachers indicate that topics that can be associated with hate speech are covered in their lessons. We also found that 18% of the indicators of “totally disagree” and “disagree. This shows that although in the statement “Conflict issues linked to messages, speeches or expressions that transmit hate are addressed in classes,” 31% indicate the indicator “undecided,” which raises some questions for us or instead leads us to conclude that teachers do not have clarity about the objectives they pursue in class. At the same time, it is not insignificant that 18% do not incorporate these topics into their practice; therefore, the question arises, from what perspective are they working on the content?

It is noticeable that with two similar statements such as “I usually include in my practices (occasionally) topics related to hate speech from a gender perspective as educational input for future teachers” and “I usually include in my classes (occasionally) content from social networks that expresses hate speech from a gender perspective as educational input for future teachers” similar but not identical percentages. For the first statement, we found 57% between the “totally agree” and “agree” categories and 19% for the opposite indicators. For the second statement, we found 40% in the favorable indicator for the second statement versus 32% in the denial indicator. We cannot affirm that there is a contradiction per se. However, the differences should be investigated in the context of other information collection techniques to explore these aspects where there are differences in responses to similar statements.

If we continue with the analysis that is being carried out, we can refer to the statement, “It is more important that students learn more content than on other topics such as hate speech with a gender perspective,” we found 46% who position themselves in the indicators of “totally agree” and “agree,” compared to 31% in the indicators of “totally disagree” and “disagree.” If we focus on the 31% just mentioned, a certain incoherence or lack of logic in the discourse could be raised since, in this case, there is a rejection of the idea that students learn more about topics related to hate speech. This even becomes more complex if we contrast it with the statement, “Gender issues and problems are aspects that should not be dealt with in educational spaces or in teacher training,” where we found 83% who position themselves in the indicators of “totally disagree” and “disagree.” Therefore, we cannot establish a unified criterion regarding the beliefs expressed by teachers regarding the problem, so such aspects should be investigated in future studies that include such approaches.

If we contrast the statements of “when hate speech from a gender perspective arises in my practices, I immediately stop the class and express my disagreement and then continue with the content,” we find 79% in the affirmative indicators versus 8% in the negative indicators; “When hate speech from a gender perspective arises in my practices, I immediately stop the class and promote a debate between the students,” we see 74% in affirmative positions in contrast to 11% in the opposite indicators and; “When hate speech from a gender perspective arises in my practices, I immediately stop the class and have a private conversation with the people involved” we find 63% of affirmative responses versus 8% of negative statements. The above indicates a clear trend; although the answers are not exactly similar in percentages, their statistical variability is not significant, so we could suggest that the beliefs of the teaching staff conform to the practices that the statements indicate.

In the same analysis, we can consider the responses to the statement, “Teacher training courses should not deal with hate speech, since this quotation is a response to social problems that must be resolved in other spaces”; we find 76% of responses in opposing positions, compared to 13% who are in the affirmative. This result suggests that, for these teachers, the programs must deal with such problems and complexities. It is not insignificant that 13% of the respondents argue that this should not happen, but they also argue that such issues should be worked on in other spaces outside of the courses. However, the teachers, if we consider the statement “Teachers should be trained to work on hate speech, however, there is neither the time nor the training opportunities to carry out such tasks,” 58% affirm that teachers should have training in this regard. However, they do not have the space, time, or skills that prevent them from accessing such knowledge. Along the same lines, 24% position themselves in categories that assume that teachers should be trained to work from such perspectives and problems in teacher training despite not having the time or space.

In the questionnaire, the sentence of “Teacher educators have the duty to prepare and work on hate speech from a gender perspective as an important issue for inclusion in the teaching of their discipline,” it is interesting to note that 88% of participants affirmed the duty of teachers to receive training on hate speech in order to include it in their practice. We found that only 4% of participants indicated this should not be the case; therefore, teachers would not need to train themselves to work on such issues. In this sense, we could include the statement, “Independent of the actions of the Ministry and/or families; courses must assume the duty to work on the construction of counter-narratives of hate from a gender perspective,” in which 91% affirm that courses must assume that there is a problem with expressions of hate. Therefore, it must be addressed by constructing counter-narratives that promote new versions and narratives in the face of events that generate discrimination and inequality.

Last but not least, we must point out the responses to the statements “hate speech commonly materializes in violent actions towards marginalized groups,” where 83% are positioned in affirmative indicators, and in the statement “Hate speech towards diversities, in general, is accompanied by actions of physical, material and/or psychological violence,” the situation is quite similar since 90% of the responses fall into affirmative sectors, both agreeing on the seriousness of the problem we face. This finding shows that, from the beliefs of the teaching staff, there is recognition of the consequences of the dissemination, production, and reproduction of hate speech and, therefore, the consequences that it can have for people and society in general. The statement could give a clue about new ways to investigate the problem, “Social networks influence the construction and reproduction of students’ discourses,” with 96% positioning in the categories of “totally agree” and “agree,” leaving no room for doubt about the teachers’ belief in the function of social networks and their relationship with hate speech, which should be further explored and addressed in future studies that consider the results presented here.

4.2 Characterization of teachers’ beliefs about hate speech from initial teacher training

To characterize teachers’ beliefs, we used the strategy of multiple choice questions, following the definitions of Castellvi et al. (2023) and Cohen et al. (2013) where, in research on social science teaching, such a strategy has been useful to generate panoramas of the participants’ beliefs. Indeed, we can begin by pointing out that 97% of the participants declared that they make personal use of social networks. This percentage is an interesting finding, considering that it is stated in the previous section that social networks are the main space from which hate speech is disseminated and reproduced. This ratio could be contrasted with the question: Do the hate speech you hear in the media and social networks affect you in any way? Where 76% responded affirmatively. From this result, we can indicate that there are controversies in the use of social networks, as this is where, in their opinion, the greatest amount of hate speech is generated and spread.

In the same vein, we can consider that, in light of the impacts of hate speech on society, 76% of the respondents stated that such comments have a detrimental effect on the professional field. In parallel, 56% also indicated that such expressions affected them in the relationships they established with their peers. It is striking that 6% of the teaching staff stated that hate speech did not affect them in any way. In this matter, we can delve into and characterize some aspects that form part of the beliefs of the participating teaching staff and are related to the effects of hate speech from a social perspective. 93% of them indicated that such expressions promote violence and discrimination, which means the remarkable coincidence that exists between the participants and what we could indicate as the main effect of such conflictive situations. Next, 83% indicated that the effects are emotional, giving them clues about the type of violence of the expressions of hate.

Additionally, this finding appeared that hate generates social exclusion (75% of affirmative responses) and causes mental health problems among the participants (72% of affirmative responses). It is not insignificant to consider the 66% who point out that hate speech generates complexities in the development of the educational process. Due to the nature of the instrument, we do not know what aspects of the educational process they could refer to, which, and due to the interest it entails, should be investigated in future studies. Finally, we cannot fail to mention the 58% who affirmed that expressions of hate restrict freedom of expression. This result means that people cannot develop frameworks of freedom due to the hatred produced towards them.

We are particularly interested in teachers’ responses to whether freedom of expression should be restricted because of the dissemination and expression of hate. We found that 40% of responses indicated that laws should set limits on freedom of expression. Only 18% stated that freedom of expression is a right that should not be restricted. At the same time, we can draw a contrast with the responses to the question of what you think the state should do about hate speech. The majority of responses focus on the choice that indicates that public policy should protect people from such speech. Next, and attracting our particular attention, 72% of teachers state that laws should be stricter to stop the spread of such speech. From this result, we can infer and establish a relationship between restricting freedom of expression and the state’s action in creating stricter laws to stop the spread of hate speech. This aspect should be further explored in subsequent studies due to its relevance to developing critical thinking, citizenship education, and preserving democracy.

When we asked the participants if we could add if they include some kind of gender and diversity treatment in their practices, we found that 51% responded in the affirmative that they do. However, they do not have sufficient skills to do so as they would like, so it is only partially done. This result shows that teachers consider this problem and topic relevant. At the same time, they might be interested in receiving better training that would enable them to create significant inclusion processes in their practice. In fact, in this framework, we found 40% positive responses indicating that this is a relevant topic for the training of future teachers and should, therefore, be included in their programs. We do not know how this should be done, whether by redesigning the curriculum, through optional or cross-curricular courses, or another idea of the teaching staff. Considering the present work and the topic being addressed, it would be extremely interesting to investigate this aspect in future studies. It would be possible to add to the above that when asked about the types of reforms that could be made to the programs or curricula to include topics and problems that deal with hate speech, 35% of the participating teachers agreed with the need to promote more courses on citizenship education, followed by 24% on courses on gender and interculturality, which are topics that could relate to aspects that are discriminated by hate speech.

5 Discussion

Regarding the teachers’ statements, we can note some interesting aspects that contrast with the theory on this subject. For example, it is essential to mention that 52% of teachers beliefs state that they do address issues related to hate speech. As the previous studies (e.g., Aguado Odina et al., 2022) showed, it is essential that conflictual issues, such as socially relevant problems, are addressed in teacher training and that the objectives pursued in promoting the teaching processes are transparent. This result also aligns with the teachers’ statements, 18% of whom stated that they did not consider such topics in their practice. As the works González-Valencia and Santisteban-Fernández (2016) showed, despite various efforts and didactic proposals to change teaching practices towards contexts in which social complexities affecting students are addressed, teachers’ practices remain framed in traditional and patriarchal perspectives.

In this regard, we can refer to the works of Díez Bedmar (2022), Marolla Gajardo et al. (2021), Marolla (2019) and Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2020), who concur that the practice of teacher educators continues to transmit traditional content under society’s conservative views. In particular, these views are understood from a masculine and patriarchal perspective, in which the emphasis is on the actions of men with political, economic, and military power. In this way, narratives have been constructed to the detriment of the actions and histories of other characters, such as women, diverse ethnic groups, the poor, and children, among others that we could mention that have been excluded in historical and social development. It is from such perspectives and contexts that teachers transmit and teach the actions of history.

In light of this finding, we cannot fail to mention that the learned narratives do not provide a framework or possibilities for their problematization (Canal et al., 2012; Marolla-Gajardo et al., 2021; Santisteban, 2019). They are taught and worked with historical narratives that pretend to be objective and do not provide the possibilities to promote critical and creative thinking or citizenship education. It is not a history that poses the question of students with solving problems or dilemmas (Ipar et al., 2022), such as hate speech and its impact on people’s lives. Instead, it is an objective, narrative story that must be memorized to be recited on demand. It appears that the appearance is that history has unfolded gradually and that powerful men or solutions have either solved the problems that have arisen or that events have occurred for which there is no concrete explanation.

Similarly, we can comment that based on the beliefs expressed by teachers, 60% of students expressed interest in including topics related to hate speech in their lessons. Beyond that, however, we would like to focus on the 22% of students who did not express interest in this regard. Here, we asked ourselves: What are the teaching staff’s practices? What are the students’ attitudes or interests? What are the dynamics of educational practices? Other questions could give us a deeper insight into the teaching and learning process. Theoretically, we can find the studies of Crocco (2018, 2019), Molet Chicot and Bernard Cavero (2015) those who agree that it is not only important that teachers are committed to teaching that promotes change in the face of traditional and social inequalities but that there must also be an interest and a need on the part of students to bring about change that enables them to develop critical and civic thinking in the face of the complexity they face as individuals, which they can also share with the collective. Here, it is essential to note suggested by Aubert et al. (2004) and Giroux (2018) that the transformative potential that education can have can be understood.

The rejection expressed by teachers towards hate speech is of particular interest, as mentioned in the results section. Here, we realize that 20% expressed that such a situation does not occur, and 29% are neutral. This result could be explained by following the work and ideas of Amezaga et al. (2020) and Apolo et al. (2019), those who state that while there is a recognition of gender issues or other types of inequality, There may even be a recognition of hate speech; they may adopt and share some hate perspectives (Barnidge et al., 2019; Chen, 2021) or, in other cases, they may prefer not to address the situation by expressing an apparent ‘neutrality’ towards the problems (García Tomé, 2022). We are very interested in the 10% of teachers’ responses stating that their colleagues support hate speech when it occurs in practice. Carlson (2021) and González Nadal and Hernández (2023) note that hate speech is not only produced and reproduced by extremist groups but is also often shared and disseminated by individuals who do not belong to any particular group but only share discriminatory ideas that promote inequalities.

In the results section, we noted some contradictions in the teachers’ responses that make it attractive to analyze them in more detail. On the one hand, 46% of teachers responded positively to the suggestion that students should learn more about content than about the treatment of hate speech, while 31% disagreed. This result is in direct contrast to the suggestion that gender issues and problems should be addressed in teacher training, with 83% agreeing. Following the studies of Barendt (2019), Marolla-Gajardo et al. (2023) and Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021), we could suggest that teachers do not consider the issue of hate speech relevant or have not given it the importance it deserves as a socially relevant problem, which is why they would opt for content-based teaching.

In this sense, and as studies such as those by de la Cruz et al. (2019), Díez Bedmar and Ortega-Sánchez (2021), García Luque and de la Cruz (2017), Marolla Gajardo et al. (2021), and Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2020) have stated, there must be teacher training that recognizes current gender problems and focuses its courses and perspectives to provide future teachers with tools to position their work in line with combating inequalities. Without the minimum competencies, it is difficult for teachers to promote change. On the contrary, they are likely to reproduce inequalities because they do not know the strategies and pathways by framing themselves in content-based, traditional, and patriarchal teaching methods (Crocco, 2019; de Lauretis, 2015; Díaz de Greñu and Anguita, 2017; Díez Bedmar, 2022; Muzzi et al., 2019). This should be done, as teachers agree with the answers given during the study, regardless of the decisions of the Ministry, as it is framed with the objective of social justice and only a curricular transformation.

Education is a powerful instrument in addressing hate speech, offering a proactive and sustainable approach to strengthening democratic norms. Hate speech poses significant challenges to democratic societies, often undermining the principles of equality, dignity, and mutual respect that are central to democracy. As Reid (2020) asserts, regulating hate speech does not necessarily erode democratic legitimacy; instead, when implemented judiciously, it can serve to protect the foundational values of democracy. Education, as a complement to regulation, amplifies this protective function by cultivating a society resilient to hateful rhetoric and committed to democratic ideals. Educational programs can go beyond simply teaching students to identify hate speech; they can also foster deeper engagement with the social, historical, and psychological contexts that give rise to it. By integrating modules that address systemic discrimination, historical injustices, and the psychology of prejudice, educational institutions can help individuals develop an empathetic understanding of marginalized experiences. This nuanced approach not only mitigates the appeal of hate speech but also strengthens the social fabric by encouraging solidarity across diverse groups. Moreover, such programs highlight the distinction between free speech and harmful speech, allowing students to better navigate the complexities of democratic discourse without conflating harmful rhetoric with legitimate expression.

Critical thinking is a cornerstone of democracy, enabling citizens to engage thoughtfully with competing ideas and resist manipulation. Education equips individuals with the analytical tools needed to deconstruct hate speech, exposing its logical fallacies, emotional appeals, and underlying biases. This critical engagement helps to dismantle the power of hate speech to persuade or polarize, reinforcing democratic norms of rational debate and informed decision-making. Reid’s (2020) argument for a cautious approach to regulating hate speech aligns with this perspective, suggesting that fostering critical literacy can serve as a non-coercive means of protecting democratic legitimacy. Democracies thrive on the principle of pluralism, which requires fostering an environment where diverse perspectives coexist peacefully. Hate speech, by its very nature, undermines this principle, often targeting specific groups and eroding social trust. Education can counteract this by emphasizing the collective responsibility of individuals to uphold inclusive norms. Through participatory activities such as group discussions, collaborative projects, and community service initiatives, educational institutions can instill a sense of shared accountability for maintaining respectful discourse. This collective ethos not only counters the divisive effects of hate speech but also fortifies the democratic ideal of unity in diversity.

In multicultural democracies, intergenerational and intercultural understanding is critical for fostering cohesive societies. Hate speech often exploits cultural and generational divides, perpetuating stereotypes and exacerbating tensions. Educational initiatives that prioritize intercultural dialogue, historical reconciliation, and the celebration of diversity can play a transformative role in bridging these divides. By creating spaces for meaningful exchanges between different groups, education nurtures empathy, reduces prejudices, and reinforces the democratic commitment to equality and respect. Education also serves as a catalyst for civic participation, enabling individuals to become active agents in defending democratic values. Civic education programs that address hate speech can encourage students to engage in advocacy, policy-making, and community organizing. For instance, students may be empowered to campaign for anti-hate speech policies or to create awareness campaigns that promote respectful dialogue. This active engagement ensures that democratic norms are not only internalized but also enacted, creating a robust defense against hate speech at both individual and institutional levels. Reid (2020) emphasizes the importance of fostering a culture of inclusion and respect, a goal that education can achieve by preparing citizens to uphold these values in their communities.

When we talk about social justice, we must mention that the affirmative responses regarding the consequences of hate speech on people are around 90%, recognizing the seriousness of the issue, from violent actions to physical, material, or psychological violence, which are part of the expressions that seek the elimination of otherness (Bazzaco et al., 2018; Espinosa Miñoso et al., 2014; Posetti et al., 2021). At the same time, we can mention that such speeches are not random but are specifically aimed at destroying groups with specific characteristics. The teaching staff recognizes this situation. At this point, we must inevitably reflect again on the meaning of otherness by thinking, following the line of Levinas (1993) and Mèlich (2014) not only about the category of the human being as such but also about the identities and characteristics that constitute this human being because alienation does not concern the “human” being” as a human being, but is directed against people with specific characteristics and/or traits that are abhorrent to the group that emits hatred (Amezaga et al., 2020; González Nadal and Hernández, 2023). Perhaps what we lack in teacher training is a deepening of the ethical sense of society as a whole and concerning the interrelationships between them, seeking to provide a view not from compassion but from respect, tolerance, acceptance, and co-construction in a world that has multiple problems that everyone can solve. It is essential to raise the idea of social justice as a guiding principle and practice for pedagogical thinking.

The fight against hate speech through education represents a profound contribution to the preservation and enhancement of democratic norms. By promoting critical thinking, fostering social cohesion, bridging divides, and empowering civic participation, education addresses the root causes and effects of hate speech in a manner that is both preventative and transformative. As Reid (2020) highlights, the regulation of hate speech, when combined with robust educational efforts, not only avoids undermining democratic legitimacy but actively strengthens it, ensuring that the ideals of equality, dignity, and inclusion remain central to democratic life.

6 Conclusion

After conducting this research, we would like to highlight some aspects to reaffirm the importance of the results obtained and, above all, to encourage further studies with different methodologies and in other contexts to investigate the problem addressed. Hate speech is a social and global problem that does not only affect specific communities, but different types of expressions spread hate in different communities, places, territories, and countries. It is, therefore, not a problem that we should ignore or disregard, as it is a complex phenomenon that occurs on a mass scale, is produced, and is constantly reproduced.

Such expressions are significant in educational institutions and throughout the literature. The consequences of this are related to the increase in social inequalities, particularly concerning gender, ethnicity, race, migration, poverty, and religion, among other factors that are part of the identity of a particular group or community. This means that hate speech is directed against and attacks specific characteristics essential to the group in question. If we were to remove such a characteristic, such as being Muslim, from a particular community, they would no longer be part of “the Muslims.” They would, therefore, lose this identity factor. More complex cases occur when it comes to “being a woman,” “being white,” “being Mapuche,” or any other characteristic that is an inalienable characteristic of the person. For most of their life, to avoid falling into absolutes, the individual will continue to be Mapuche, as this is part of their ethnic group. Hatred, therefore, has different degrees and consequences depending on the group against which it is directed and the acts committed.

In this sense, the results show us that teachers recognize that there are hate speeches in the programs in which they participate. They confirm that there are expressions directed against different communities, ethnic groups, races, and all those who do not fit into the conservative and traditional patterns defined by dominant masculinity and hegemonic economic and political forces. It is also known that such speeches exist in educational curricula and are part of a more complex social whole that directly and indirectly affects educational institutions.

In this recognition of hate speech, teachers state that it is a problem that has been increasing in classrooms and educational spaces. At the same time, teacher training lacks the skills and tools to deal with and address the problem. Furthermore, teachers recognize that they do not have the resources to generate learning processes that incorporate and work with hate speech. The aim should be to propose spaces that combat inequality.

It is worth noting that although hate speech is not a constant problem in teacher education, it does exist and is increasing in both production and dissemination. In this case, social networks represent a favorable space for the mass production of hate speech. As the study shows, such networks not only cause such problems to occur but also cause them to be disseminated in different contexts and locations. Furthermore, we must mention that such spread is virtually instantaneous, meaning the hate speech spread may have reached different locations within minutes. This research states that hate speech in teacher training programs is mainly spread through social networks.

What is notable about this argument is that while teachers express contradictions in some points of their answers, their commitment to including hate speech in the classroom outweighs this. They agree that something needs to be done to reduce inequalities, discrimination, violence, and all derogatory forms that imply the exclusion of people based on a particular characteristic of a particular community. Teachers affirm that one way to solve this problem is to position the curriculum according to relevant social problems. Thus, any topic can be addressed as a socially relevant problem that stimulates the development of critical and creative thinking and the empowerment of students to address inequalities. The main goal would be to position citizenship education that protects democracy and human rights as an axis for social justice.

Teachers must also recognize the consequences of producing and reproducing hate speech in society. They agree that these are violent expressions that can have psychological and physical consequences and can even lead to the death of the people subjected to violence. The level of violence can vary depending on the degree of hatred expressed and the group that emits such expressions, with some being more radical in their actions. In other cases, hatred is expressed by individuals, which makes its eradication and elimination from society even more complex, as they are not organized movements or identifiable ideological currents.

The findings of the study on hate speech in teacher education underscore the urgency of transitioning from theoretical understanding to practical application. While the research offers a rich analysis of the challenges posed by hate speech, the next step involves implementing actionable programs and policies to equip educators with the tools and strategies necessary to counteract hate speech effectively. This shift requires focusing not just on further studies but on creating evidence-based interventions that can be tested, refined, and scaled. A central recommendation is the implementation of comprehensive training programs for educators, both at the initial and in-service stages. Teachers must be equipped to recognize hate speech, understand its social implications, and respond effectively. Such training could include:

• Workshops on Critical Literacy and Media Awareness: Teachers need practical strategies to help students deconstruct hate speech in digital and offline spaces. Workshops could focus on identifying manipulative rhetoric, understanding the psychological and social impact of hate speech, and constructing counter-narratives that promote empathy and inclusivity.

• Diversity and Inclusion Modules: Curricula should integrate content that normalizes diversity and promotes understanding of different cultural, ethnic, gender, and social identities. By fostering an environment of inclusion, these modules can reduce the prevalence of hate speech in classrooms.

• Guidelines for Addressing Hate Speech in Real Time: Teachers often face hate speech during their practice but lack clear protocols for responding. Providing specific guidance, such as facilitating class discussions, engaging in restorative dialogues, or reporting incidents to school authorities, can empower teachers to address such challenges confidently.

Programs such as these align with the practical recommendations outlined in the document, particularly regarding the need for curricular reforms and the development of counter-narratives as proactive educational strategies. There are notable examples of school systems and initiatives successfully addressing hate speech that could serve as models:

• The No Hate Speech Movement (Council of Europe): This initiative equips educators with tools to combat hate speech through education and advocacy. Schools participating in the campaign have implemented workshops that encourage critical thinking and empower students to challenge discriminatory language.

• Finland’s KiVa Program: While primarily an anti-bullying program, KiVa addresses the roots of hate speech by promoting social cohesion and empathy among students. The program includes teacher training, student workshops, and community involvement, creating a holistic approach to tackling harmful behaviors.

• Australia’s Harmony Day Initiatives: Australian schools use Harmony Day to celebrate cultural diversity and address issues such as racism and hate speech. Activities range from class discussions to community events, fostering a culture of respect and understanding.

These examples highlight the importance of integrating anti-hate speech initiatives into broader frameworks of citizenship and diversity education. They also provide evidence of the efficacy of multi-pronged approaches that combine training, student engagement, and community involvement. Moving from research to actionable solutions requires a focus on experimental programs and the evaluation of their outcomes. To use findings effectively, it is essential to:

• Develop Pilot Programs: Based on the recommendations in the study, pilot programs can be designed to test specific interventions, such as workshops on counter-narratives or digital literacy training. These pilots should be monitored to assess their impact on reducing hate speech and fostering inclusive classroom environments.

• Create Collaborative Platforms: Collaboration between researchers, educators, and policymakers is crucial for translating research findings into practical tools. Establishing networks where best practices and resources can be shared will ensure broader adoption and adaptation to local contexts.

• Measure Impact: Collecting evidence of what works is vital. Schools implementing anti-hate speech programs should track changes in student behavior, teacher confidence, and the overall school climate. This data will not only validate the effectiveness of interventions but also inform the refinement of strategies.

The fight against hate speech in education is both a moral and democratic imperative. While research provides a solid foundation, it is the practical application of these insights that will bring about meaningful change. Immediate steps include the integration of diversity-focused content into curricula, the development of teacher training programs, and the establishment of clear guidelines for addressing hate speech in schools. Drawing inspiration from successful case studies, educators and policymakers can implement targeted interventions that transform classrooms into spaces of respect and inclusivity. By prioritizing action and experimentation, we can ensure that research findings are not just theoretical but actively contribute to building a more democratic and equitable society.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Santo Tomás Scientific Ethics Committee Letter/Report No. 23-2024. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JM-G: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile (ANID), FONDECYT 11231022.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aguado Odina, T., Izquierdo Montero, A., Laforgue Bullido, N., and Lorón Díaz, Í. (2022). Adolescents facing hate speech. Participatory research to identify scenarios, agents and strategies to confront them. Reina Sofia Center on Adolescence and Youth.

Amezaga, A., María, C.G., Kuric, S., Morado, R., and Orgaz, C. (2020). Breaking chains of hate, weaving support networks: young people facing hate speech on the internet. Reina Sofía Center on Adolescence and Youth.

Apolo, M., Calderón, C., and Amores, J. (2019). Hate speech towards migrants and refugees through the tone and frames of messages on Twitter. J. Span. Assoc. Commun. Res. 6, 361–384. doi: 10.24137/raeic.6.12.2

Aubert, A., Fisas, M., Valls, M.R., and Duque, E. (2004). Dialogue and transformation: Critical pedagogy of the 21st century. Grao.

Barendt, E. (2019). What is the harm of hate speech? Ethical Theory Moral Pract 22, 539–553. doi: 10.1007/s10677-019-10002-0

Barnidge, M., Kim, B., Sherrill, L. A., Luknar, Ž., and Zhang, J. (2019). Perceived exposure to and avoidance of hate speech in various communication settings. Telematics Inform. 44:101263. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101263

Bazzaco, E., García Juanatey, A., Lejardi, J., Palacios, A., and Tarragona, L. (2018). Is it hate? Practical manual to recognize and act against hate speech and crimes. Institute of Human Rights of Catalonia, SOS Racisme Catalunya. Available at: https://www.idhc.org/es/publicaciones/es-odio-manual-practico-para-recognize-y-actuar-frente-a-discursos-y-delitos-de-odio.php (Accessed October 15, 2023).

Bisquerra, R., and Alzina, R. B. (2004). Educational research methodology. Madrid: La Muralla Editorial.

Canal, M., Costa, D., and Santisteban, A. (2012). Students facing relevant social problems: how do they interpret them? How do they think about participation? In N. Albade, F. García Pérez, and A. Santisteban (Eds.), Educating for citizen participation in the teaching of social sciences (Díada-University Association of Professors of didactics of social sciences), pp. 527–536. Sevilla: University Association of Professors of Didactics of Social Sciences.

Cardona Moltó, M. C. (2002). Introduction to research methods in education. Madrid: EOS Publishing House.

Castellvi, J., Marolla, J., and Escribano, C. (2023). “Qualitative research” in How to research in social sciences didactics? Methodological foundations, techniques and research instruments. ed. D. Ortega-Sánchez (Barcelona: Octahedron), 11–120.

Chen, T. (2021). The influence of hate speech on TikTok on Chinese college students [master Dissertatiton, graduate theses and dissertations, University of South Florida]. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/8747/ (Accessed March 10, 2023).

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Crocco, M. (2018). “Gender and sexuality in history education” in The Wiley International handbook of history teaching and learning. eds. Metzger, S. A., and Harris, L. M. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 335–363.

de la Cruz, A., Díez Bedmar, M. C., and García Luque, A. (2019). Teacher training and reflection on diverse gender identities through social sciences textbooks. In M. Joao Hortas, A. Dias D'Almeida, and N. Alba Fernándezde (Eds.), Teaching and learning social sciences didactics: Teacher training from a sociocritical perspective (pp. 273–287). Lisbon: AUPDCS-Polytechnic of Lisbon.

De Leeuw, E. (2004). New technologies in data collection, questionnaire design and quality. Bilbao: Basque Institute of Statistics.

Díaz de Greñu, S., and Anguita, R. (2017). Teacher stereotypes regarding gender and sexual orientation. Interuniv. Elect. J. Teach. Educ. 20, 219–232. doi: 10.6018/reifop/20.1.228961

Díaz de Rada, V. (1999). Data analysis techniques for social researchers. Practical applications with SPSS for Windows. RA-MA editorial.

Díez Bedmar, M. C. (2022). Feminism, intersectionality, and gender category: essential contributions for historical thinking development. Front. Educ. 7, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.842580

Díez Bedmar, M. C., and Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2021). “State of the art on the gender perspective and the teaching of history and social sciences in Spain” in The teaching of history in Brazil and Spain: A tribute to Joan Pagès blanch. eds. I. A. Santisteban and C. A. Lima Ferreira (Belo Horizonte: Editora Fi), 234–254.

Espinosa Miñoso, Y., Gómez Correal, D., and Ochoa Muñoz, K. (2014). Weaving in a different way: Feminism, epistemology and decolonial bets in Abya Yala. Popayán: University of Cauca Press.

Font Fábregas, J., and Pasadas del Amo, S. (2016). Opinion polls. Madrid: The books of the Catarata.

García Luque, A., and de la Cruz, A. (2017). “Coeducation in initial teacher training: a strategy to combat gender inequalities” in Research in social sciences didactics. Challenges, questions and lines of research. eds. I. R. Martínez, R. García-Moris, and C. R. G. Ruíz (Córdoba: AUPDCS-University of Córdoba), 133–142.

García Tomé, N. (2022). Tackling hate speech through social sciences [TFM]. Jaén: University of Jaén.

Giorgi, G., and Kiffer, A. (2020). The turns of hatred. Gestures, writings, politics. Eterna cadencia editoriala.

Giroux, H. (2018). Pedagogy and the politics of Hope: Theory, culture, and schooling: A critical reader. New York, NY: Routledge.

González Nadal, D., and Hernández, J. (2023). Hate speech and LGTBIQ+ pride in the digital conversation (ideas Llorante and Cuenca 1; LLYC IDEAS, p. 26). LLYC IDEAS. https://resources.llyc.global/es/hate-speech-and-lgtbiq-pride-in-the-digital-conversation (Accessed June 12, 2023).

González-Valencia, G. A., and Santisteban-Fernández, A. (2016). La formación ciudadana en la educación obligatoria en Colombia: entre la tradición y la transformación. Educación y Educadores 19, 89–102. doi: 10.5294/edu.2016.19.1.5

Haider, A. (2020). Misunderstood identities. Race and class in the return of white supremacy. Oakland, CA: Dream traffickers.

Ipar, E., Villarreal, P., Cuesta, M., and Wegelin, L. (2022). Dilemmas of the digital public sphere: hate speech and political-ideological articulations in Argentina. Latin America Today 91, 93–114. doi: 10.14201/alh.27755

Izquierdo Grau, A. (2019). Critical literacy and hate speech: a research in secondary education. REIDICS. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Didact. 5, 42–55. doi: 10.17398/2531-0968.05.42

Latorre, A., Arnal, J., and Del Rincón, D. (1994). Methodological bases of educational research. Barcelona: Experiencia Editions.

Latour, A., Perger, N., Salaj, R., Tocchi, C., and Viejo Otero, P. (2017). We CAN! Alternatives—no hate speech youth campaign. COE. https://www.coe.int/en/web/no-hate-campaign/we-can-alternatives (Accessed March 11, 2023).

López-Roldán, P., Fachelli, S., López-Roldán, P., and Fachelli, S. (2015). Methodology of quantitative social research. Barcelona: Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Lynch, S. M. (2013). Using statistics in social research. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Manheim, J. B., and Rich, R. C. (1999). Empirical political analysis: research methods in political science (1st ed., 1st reprint). Madrid: Alianza.

Marolla, J. (2019). The absence and discrimination of women in the training of history and social sciences teachers. Educ. Elect. J. 23, 1–21. doi: 10.15359/ree.23-1.8

Marolla Gajardo, J., Castellví Mata, J., and Mendonça dos Santos, R. (2021). Chilean teacher Educators' conceptions on the absence of women and their history in teacher training programs. A collective case study. Soc. Sci. 10, 106–125. doi: 10.3390/socsci10030106

Marolla-Gajardo, J., Gutiérrez, N., and Fuentes, N. (2021). Historical problems: analysis of the absence of women and their history in the curricula of Chile and Peru. Education 30, 1–21. doi: 10.18800/educacion.202102.007

Marolla-Gajardo, J., Zurita-Garrido, F., Pinochet-Pinochet, S., and Castro-Palacios, G. (2023). Hate speech and the gender perspective: a problem from the teaching of social sciences in school. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2023, 133–144. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.12.1.133

Massip Sabater, M., Carmen Rosa, G., and González-Monfort, N. (2021). Countering hate: hate narratives in digital media and the construction of alternative discourses in secondary school students. Bellaterra J. Teach. Learn. Lang. Lit. 14, 1–19. doi: 10.5565/rev/jtl3.909

Mata Benito, P. (2011). Ethical, critical, participatory and transformative citizenship: Educational proposals from the intercultural approach. Madrid: National University of Distance Education.

Molet Chicot, C., and Bernard Cavero, O. (2015). Gender policies and teacher training: ten proposals for a debate. Temas de Educ. 21, 119–129.

Mouffe, C. (1996). Feminism, citizenship and radical democratic politics. Citizens and the political, 1996, ISBN 84-7477-574-4, pp. 1-20, 1–20.

Muzzi, S., Tosello, J., and Santisteban, A. (2019, 2019). “The gender perspective in the history and social sciences curricula in Italy and Argentina: a reflection for teacher training” in Teaching and learning social sciences didactics: Teacher training from a sociocritical perspective. eds. M. J. Barroso, A. D. D'Almeida, and N. D. A. Fernández. AUPDCS, 234–242.

Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2023). How to do research in social sciences education? Methodological foundations, techniques and research instruments. Barcelona: Octaedro.

Ortega-Sánchez, D., Marolla, J., and Heras, D. (2020). “Social invisibilities, gender identities and narrative competence in the historical discourses of primary school students” in Education for the common good: Towards a critical, inclusive and socially committed practice. eds. J. Díez Gutiérrez and J. R. Rodríguez Fernández (Barcelona: Octaedro), 89–103.

Ortega-Sánchez, D., Pagès, J., Quintana, J., Sanz de la Cal, E., and Anuncibay, R. (2021). Hate speech, emotions and gender identities: a study of social narratives on twitter with trainee teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:55. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084055

Osuna, C., and Olmo Pintado, M. D. (2019). Hidden racism. On involuntary complicity in the racist mechanism. Convives, 25. https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/178866 (Accessed March 12, 2023).

Parodi, R., Cuesta, M., and Wegelin, L. (2022). Problematizing hate speech: democracy, social media, and the public sphere. Commun. Cult. Traps 87, 1–16. doi: 10.24215/2314274xe061

Paz, M. A., Montero-Díaz, J., and Moreno-Delgado, A. (2020). Hate speech: a systematized review. SAGE Open 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/2158244020973022

Pégorier, C. (2018). Speech and harm: genocide denial, hate speech and freedom of expression. Int. Crim. Law Rev. 18, 97–126. doi: 10.1163/15718123-01801003

Posetti, J., Shabbir, N., Maynard, D., Bontcheva, K., and Aboulez, N. (2021). Online violence against women journalists: A global snapshot of incidence and impacts. UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/en/world-media-trends/online-violence-against-women-journalists-global-snapshot-incidence-and-impacts (Accessed September 18, 2023).

Reid, A. (2020). Does regulating hate speech undermine democratic legitimacy? A cautious 'no'. Res. Publica. 26, 181–199. doi: 10.1007/s11158-019-09431-6

Santisteban, A. (2019). Teaching social sciences from social problems or controversial topics: state of the art and results of a research. El Futuro del Pasado Elect. J. History 10, 57–79. doi: 10.14516/fdp.2019.010.001.002

United Nations. (2019). The United Nations strategy and plan of action on hate speech (hate speech). United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/Action_plan_on_hate_speech_EN.pdf (Accessed March 15, 2023).

Keywords: hate speech, teachers, training education, democracy, citizenship

Citation: Marolla-Gajardo J (2025) Democracy is at risk: beliefs of Chilean teachers about the transmission of hate speech in teacher education. Front. Educ. 9:1505020. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1505020

Edited by:

Titus Alexander, Democracy Matters, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nicolás De-Alba-Fernández, Sevilla University, SpainNoelia Pérez-Rodríguez, University of Seville, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Marolla-Gajardo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jesús Marolla-Gajardo, am1hcm9sbGFnQHNhbnRvdG9tYXMuY2w=; amVzdXNtYXJvbGxhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Jesús Marolla-Gajardo

Jesús Marolla-Gajardo