- 1Foreign Language Teaching Laboratory, School of English, Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 2Linguistics Laboratory, School of Philology, Department of Linguistics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Introduction: This study aims to explore the instructional strategies employed by Greek teachers in primary and secondary school classes attended by large numbers of refugee and migrant students. As there is not a clear methodological ‘blueprint’ for CLIL that teachers are required to follow, our study will investigate which of the principles framed for the CLIL approach are in fact applied by educators.

Methods: To this aim, we adopted a survey-based research methodology (web-based questionnaire) and a phenomenological approach (semi-structured interviews).

Results: Results include data from 125 respondents of the questionnaire, working in 21 different regional units of Greece, and the lived experiences of five educators. Most of the participants had no prior training in bilingual or intercultural education but were highly qualified (holders of at least an MA). Thus, although educational background was not identified as a predictive factor to the teaching strategies, training in topics such as bilingual education and interculturality was. Scaffolding techniques were significantly affected by teachers’ age, training and educational setting (primary vs. secondary). Moreover, the variety of activities offered differed between the two levels of school settings as educators chose strategies they deemed appropriate for the cognitive and proficiency level of their students.

Discussion: Overall, our findings suggest that, although educators of Greek state schools lack specific training in managing plurilingual and pluricultural classes, they experiment with a variety of CLIL practices and that those who have had some relevant trainings are more prompt to support their students with multiple scaffolding techniques than those who have had no such prior experience.

1 Introduction

Greece has been the destination for immigrants since the 1990s immigration influx from Eastern Europe; about 25 years later, the country faced an unprecedented flow of refugees mainly from Middle Eastern countries and Afghanistan and at the beginning of 2020, Greece became home to an estimated 112,300 refugees; among them, 42,500 were children with refugee or migrant backgrounds. Of these children, 31,000 were of school age, and 4,815 were unaccompanied minors (UNICEF, 2023, in Simopoulos and Magos, 2020; Ministry of Education, Religious Affairs and Sports1).

The educational management of migrant and refugee students has been a major challenge for the Greek educational system. In response to the growing need to support students from migrant or refugee backgrounds, the Greek State either reactivated and readjusted structures that were already in place, such as the Zones of Educational Priority (ZEP) and the reception classes, or created a form of ‘bridge’, such as the Reception Facilities for Refugee Education for children residing in Open Accommodation Sites. The Zones of Educational Priority (ZEP) were first launched in 2010 aiming to admit and support students with no or limited knowledge of Greek. Currently the program includes (a) reception classes, that is, pull-out classes that provide intensive Greek language courses for 3 h on a daily basis while for the rest of the school day children attend the mainstream class according to their age; (b) reception classes that are designed to support students who have acquired basic language skills in Greek, and the educator is given the option either to work with them in pull-out classes or co-teach them in the mainstream class.

The Reception Facilities for Refugee Education were launched in 2016 aiming to provide educational programs to refugee children living in Accommodation Centers. These programs provide mandatory morning or afternoon classes aimed at assisting refugee children in transitioning into the regular education system; however, such programs have been criticized for creating school segregation for refugee students who do not have the opportunity to interact or integrate with Greek students in any way (Jalbout, 2020).

By October 2023, the number of migrant and refugee children had decreased to 25,000, including 7,000 new arrivals from Ukraine and 2,000 unaccompanied minors (UNICEF, 2023). By the end of the year 2023, 15,134 children were enrolled in school, with 14,222 of them attending regularly (Asylum Information Database, 20242). Currently, the Greek educational system is expected to cater for a mosaic of student nationalities (Mattheoudakis et al., 2021; Chatzidaki and Tsokalidou, 2021), while Greek educators who have been trained to become teachers in Greek state schools—where everything is taught in Greek—are expected to accommodate students who come from various ethnic and L1 backgrounds, with limited or no knowledge of Greek.

Against this backdrop, funded projects like E.P.P.A.S. (2006–2008) and “Diapolis”3 were developed to support Greek teachers and equip them with the instructional and intercultural skills needed. In particular, the former aimed to train teachers in the combined teaching of language and content in primary and secondary education, while the latter aimed to support the work of Reception Classes and the integration of foreign and repatriated students into school education. As a result of these efforts, the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach was adopted by some inspired subject teachers, e.g., Biology, Physics, Mathematics, etc. in secondary schools (see, for example, Vletsi and Economou, 2019; Koutsandreas, 2019, among others).

The adoption of CLIL methodology in school contexts that host migrant students seems to be a reasonable and to an extent, inevitable instructional choice, as refugee and migrant students are usually speakers of languages other than the L1 of the host country and therefore they are required, within the school setting, to develop in parallel language competence in a new language and content knowledge related to the school subjects taught in the curriculum. CLIL allows instructors, irrespective of whether they teach reception or mainstream classes to focus on both language and content and to do so in an integrated way without sacrificing the one for the other and without delaying L1 speakers’ progress. Taking into consideration that large numbers of immigrants have entered the Greek schools since 2015, we should expect CLIL to be currently implemented in classes hosting multilingual learners, even if this is not always a deliberate instructional choice or even if teachers are not always consciously aware of using it.

CLIL is the European version of content-based instruction, commonly linked to the Canadian immersion programs that began in 1965 (Zaga, 2004; Cenoz, 2015). CLIL is a multifaceted phenomenon, involving a great deal of variation both in the terms used to denote the concept and in ways of realizing it (see Gülle and Nikula, 2024 for a detailed report). This flexibility may be due to the fact that CLIL does not have a clear methodological ‘blueprint’ but is a flexible approach that can be adapted to meet the needs of different educational and cultural contexts (Bower et al., 2020). According to Coyle et al. (2010), CLIL is an educational approach with a dual focus, where a language other than the native one is used as the medium for learning and teaching content; this dual focus results in the simultaneous acquisition of both language and content.

Historically, English has been the most popular vehicular language used in CLIL contexts and in 75% of those cases, English is a foreign rather than a second language (Gülle and Nikula, 2024). However, due to global mobility, international migration and other sociocultural changes on a global level, opportunities have emerged which enable other major, home and/or indigenous languages to become vehicular languages in specific CLIL contexts (Bower et al., 2020). The application of CLIL with languages other than English has also been promoted by the European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML) which funded the CLIL LOTE (CLIL in Languages Other Than English) program in 2021 (Daryai-Hansen et al., 2023). CLIL LOTE aimed to support CLIL in languages other than English across educational settings, both in the language classroom and in other subjects.

Against this backdrop, in our study we are going to examine the implementation of CLIL with the use of Greek as a vehicular language in primary and secondary state schools located in various parts of Greece, attended by Greek native and non-native speakers. This is an under-explored research area with important implications for education policy designers as well as teacher education programs and in-service teacher training.

2 Literature review

Research in the use of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in immigrant educational contexts in countries which historically have hosted large numbers of immigrants and refugees is not too extensive, but it underscores the potential of CLIL methodology both for supporting academic achievement and social inclusion. Somers (2017, 2018), for example, supports that CLIL programs are capable of providing immigrant students with educational opportunities and effective pedagogical support which existing mainstream monolingual, and minority bilingual education programs may not. He therefore proposes that immigrant students should have access to multilingual programs utilizing the CLIL approach. Otterup (2019) also explores the implementation of CLIL methodology with English as a vehicular language in a Swedish school attended by several migrant students of different L1 backgrounds. The author adopts some sociolinguistic concepts such as power relations, symbolic capital, investment, and agency for elaborating on various benefits the participants get from the English-mediated instruction. Ortiz and Finardi (2023) looked into the potential effectiveness of CLIL for the social inclusion of refugees and immigrants, rather than for its impact on academic success. This was a project implemented by a non-governmental association—La Roseraie—in Geneva, Switzerland, whose aim is to help in the social inclusion of refugees and immigrants. The results of the study indicated that the use of CLIL can promote social inclusion by helping participants understand issues related to everyday life through the language as well as by using the language to relate to and improve life in that context.

As already mentioned, research in the use of CLIL methodology for the teaching of Greek (L2) to immigrants and refugees is scarce. This is due mainly to the fact that CLIL methodology is not officially implemented in Greece or promoted in any way (see also European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2023; Mattheoudakis, 2019; Varis, 2023) and therefore, Greek instructors are not trained in CLIL methodology. Having said that, we should acknowledge that there are individual schools and instructors who have introduced CLIL in their own setting, but these are scarce and rarely reported or published (see Varis, 2023 for some exceptions with regard to CLIL implementation in Greece with English as a vehicular language). With respect to Greek as a second language, to date, only Papastylianou (2018) has discussed the application of CLIL to unaccompanied minor refugees in Greece in a primary school setting, without however testing its effectiveness in the particular context. Also, Kosyvas (2020) has looked into CLIL strategies for teaching Mathematics to refugee/migrant students in intercultural schools in Greece and some of the educators who attended the program “Diapolis” mentioned above, implemented CLIL in their high school classes and reported on its impact on their students’ academic performance (see Vletsi and Economou, 2019; Koutsandreas, 2019). In all of the aforementioned studies, Greek was the vehicular language in a mixed class of native and non-native speakers of Greek.

Recent insights from CLIL research, second language acquisition research, teaching methodology and extensive classroom observation in several countries have indicated six (6) quality principles and strategies that are important in the implementation of CLIL (Meyer, 2013). These are: (a) rich input, (b) scaffolding, (c) rich interaction and pushed output, (d) interculturality, (e) development of Higher Order Thinking skills (H.O.T.), and (f) sustainable learning. Below we are providing the theoretical background underlying each of the strategies as well as some practical applications in class.

a. Rich input: Research in second language acquisition has underscored the importance of meaningful and challenging input in foreign language acquisition (Krashen, 1987). Classroom content needs to be meaningful by focusing on global issues but also being relevant to students’ prior knowledge, experiences, interests, and attitudes. Video clips, flash-animations, web-quests, podcasts, or other interactive materials can become a rich source for designing interesting tasks that will create opportunities for meaningful language output.

b. Scaffolding learning: To help students successfully deal with the rich input of authentic materials and to make sure that most of this input can become intake, scaffolding is essential. Scaffolding helps reduce the cognitive and linguistic load of the input (= input-scaffolding) and thus supports language and content comprehension. Scaffolding also helps learners complete a given task or assignment through appropriate, supportive structuring. Finally, scaffolding also supports language production (= pushed output) by providing sentence frames, phrases, subject-specific vocabulary and lexical chunks necessary to complete assignments. In sum, scaffolding can boost students’ cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP).

c. Rich Interaction and Pushed Output: According to Long’s Interaction Hypothesis (1996), interaction promotes and facilitates language acquisition. It is the feedback received during interaction that promotes interlanguage development because interaction “connects input, internal learner capacities, particularly selective attention, and output in productive ways” (Long, 1996, p. 451). Swain has claimed that modified output supports L2 development because “learners need to be pushed to make use of their resources; they need to have their linguistic abilities stretched to their fullest, they need to reflect on their output and consider ways of modifying it to enhance comprehensibility, appropriateness and accuracy” (Swain, 1993, p. 160). In CLIL classes, student interaction and output are promoted and supported by tasks and that is why task design is one of the key competences for every CLIL teacher.

d. Interculturality: The importance of interculturality in education has been underlined in several studies (e.g., Dervin, 2016) and according to Camerer (2007), the promotion of intercultural communicative competence should be the ultimate educational goal. CLIL can promote this goal as it allows students to discover the hidden cultural codes and use the appropriate means and strategies to address them.

e. Development of Higher Order Thinking Skills: According to Meyer (2013), the core elements of CLIL—input, tasks, output, and scaffolding—need to be balanced in class so that various cognitive activities are triggered. Additionally, systematic work with the language is of overriding importance as it helps students develop their linguistic skills and express their thoughts in an increasingly complex manner. Zwiers (2006) recommends the use of writing scripts/scaffolding frames for the incorporation of academic thinking skills in teaching routine.

f. Sustainable learning: By ‘sustainable learning’, we refer to the need to make sure that “what is taught in class is taught in a way that new knowledge becomes deeply rooted in students’ long-term memory” (Meyer, 2013, p. 307) Meyer makes specific recommendations that aim to help teachers achieve this goal, e.g., promote autonomous learning, introduce portfolio work, adopt translanguaging, make connections to students’ attitudes and experiences, promote a lexical approach and spiral learning.

To our knowledge at least, to date there have been hardly any studies aiming to examine the use of CLIL strategies in class. A recent one was carried out in Turkey by Metlí and Akıs (2022) with English as the medium of instruction in a class of students attending the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program. The paper outlines the challenges encountered by the teachers, such as the lack of vocabulary repertoire and weak foundational knowledge, and describes the strategies used by the instructors to address these challenges—interdisciplinary activities, individualized feedback, and the promotion of higher-order thinking skills. However, the setting and the participants of this study are very different from the one examined in our research and therefore it cannot be used for comparative purposes.

3 The research

3.1 Aim and research question

Taking into consideration that (a) the implementation of CLIL methodology in Greek state schools with mixed student population is expected to be more common than officially reported, (b) that Greek educators do not receive any official training in CLIL methodology, and (c) that CLIL instructors need to follow the principles and strategies mentioned above, our study aims to explore some instructional strategies employed by Greek teachers in primary and secondary school classes attended by large numbers of refugee and migrant students. Thus, this study focused only on a few aspects out of necessity of circumscription of the research focus and in order to have the possibility to deepen the investigation of these specific aspects. As there is not a clear methodological ‘blueprint’ for CLIL that teachers are required to follow, our study will investigate which of the principles framed for the CLIL approach (Meyer, 2013) are in fact applied by educators. In particular, we are going to focus on the use of scaffolding in learning, interaction and output, and interculturality. The strategies for the promotion of rich input, developing H.O.T. skills and sustainable learning, though vital in the CLIL instructional process, are not going to be explored, for the reasons stated above. We do recognize that drawing clear distinguishing lines is not always feasible as class instruction is a dynamic process and tends to combine or merge strategies, thus blurring the distinctions. However, for the sake of this research, we will adopt Meyer’s (2013) categorization and focus on specific practices and strategies as will be explained below.

3.2 Methodology and materials

In the present study we followed a mixed-methods design, given that this is broadly accepted as a research design that allows investigators to explore educational complexities combining quantitative and qualitative data (e.g., Zhou et al., 2023): we used quantitative and qualitative approaches (a) simultaneously, by integrating both closed- and open-ended questions in our questionnaire, and (b) sequentially, by integrating an explanatory follow-up phase of one-to-one interviews, with nested sampling.

The present study includes two parts: for the first part, we used a survey-based research methodology, with both quantitative and qualitative data: A web-based questionnaire was utilized to access a widely dispersed population of educators in various school settings with a tool that has been judged suitable for people who are quite familiar with the internet use (e.g., McDougald, 2015). The questionnaire consisted of two sections: The first one included 11 items aiming to elicit data regarding participants’ demographics, professional and educational background as well as school subjects taught. The second section included three separate questions which examined in total 20 strategies. The strategies studied included (a) eight strategies for introducing a new concept in class, (b) five strategies for supporting students’ participation in class, and (c) seven strategies to support assessment. Each of the three questions tapped on one of the above categories—a, b, or c—that corresponds to a distinct stage of the teaching process—presentation (introducing a new concept), rehearsal (supporting student participation), and evaluation (assessment). The 20 strategies included in those questions covered mainly three thematic axes; these correspond to Meyer’s (2013) suggested typology of CLIL strategies, and in particular to: (a) inclusion of migrant students’ L1s and cultures in class (interculturality), (b) use of instructional practices for scaffolding learning, and (c) use of instructional practices for promoting student interaction and output. Most questions also included an additional option for participants to select in case they wished to add further suggestions and teaching practices, not included in the options given. A final question asked participants to identify whether students are allowed to use specific strategies during the three teaching phases mentioned above. Furthermore, participants were presented with a set of seven statements about teaching and assessment practices and were required to mark the degree of their agreement on a 5-grade Likert scale ranging from ‘Totally disagree’ to ‘Totally agree’ and the option of ‘no response’, irrespective of their actual self-reported practices. A final open question invited participants to provide remarks or comments related to the topic examined (For the full Questionnaire, see Supplementary material 1).

For the second part of this survey, we adopted a phenomenological approach because it is well-suited for exploring teachers’ lived experiences. Qualitative analysis gave us the opportunity to investigate participants’ experiences, beliefs and opinions, and provided us with detailed insight and understanding of their choices in their effort to balance content and language during teaching. To this aim, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five educators who volunteered to participate. The semi-structured interviews covered a set of 15 questions (Supplementary material 2), serving as a reference point to facilitate the conversation. These questions addressed issues related to practices used in multilingual classes as well as teachers’ professional experiences (e.g., Villabona and Cenoz, 2021; Calafato, 2023), as these emerged from participants’ answers to the questionnaire. The interviews lasted up to an hour each and were recorded on Zoom. Using digital methods for the interview was deemed necessary as it enabled us to reach participants who were located in geographically remote areas. All interviews were conducted in Greek; the excerpts included in the paper were translated into English by one of the researchers.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The study was approved by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Research Committee (Ethics Approval: 29645/2024) and written informed consent was obtained by the participants during recruitment. First, the web-based questionnaire was distributed to specific primary and secondary schools in various geographical areas in Greece (the areas from which we received responses can be found in Supplementary material 3); these are schools admitting a large number of migrant and refugee students. Teachers were encouraged to complete the questionnaire, but their participation was optional. To reduce the risk of volunteer bias, we kept our informants unaware of the objectives of the study; however, our results should be considered representative only of the specific population. Also, the last question of the questionnaire explicitly required them to state whether they would be willing to give an interview related to the themes covered in the questionnaire. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with a representative sample of the educators who explicitly expressed interest in being involved in this phase of the research. By that we mean that the teachers selected represented different levels of education and specialties and included an educator who also held a position of responsibility. Collected data from the questionnaire were next coded quantitating qualitative components (see 3.2 and 4.1 for further detail), and quantitative data were analyzed in SPSS; in the end, interviews were transcribed verbatim, and interviewees’ responses were analyzed and discussed.

3.4 Participants

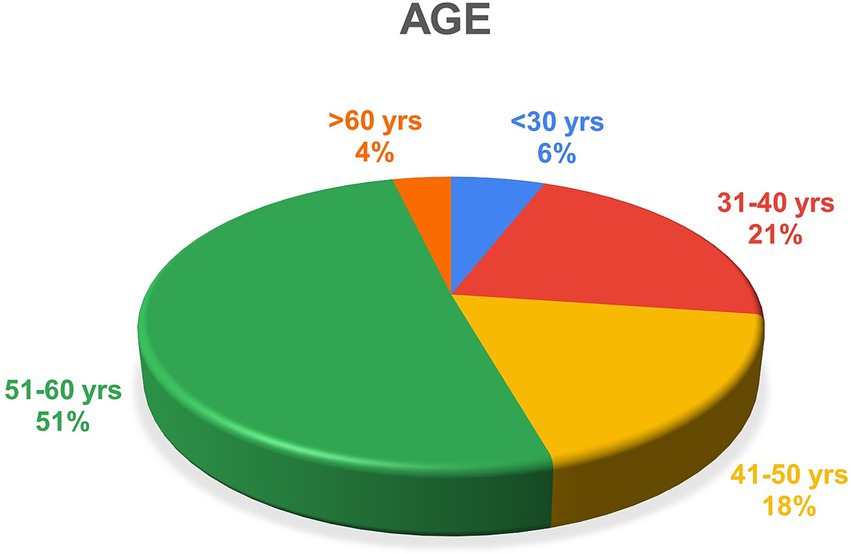

The web-based survey was completed by 136 (123 female and 13 male) educators. Respondents came from 21 out of the 74 regional units of Greece (Supplementary material 3); half of them were between 51 and 60 years old and about 40% of the participants were between 31 and 50 (n = 55); very few were younger than 30 or older than 60 (Figure 1).

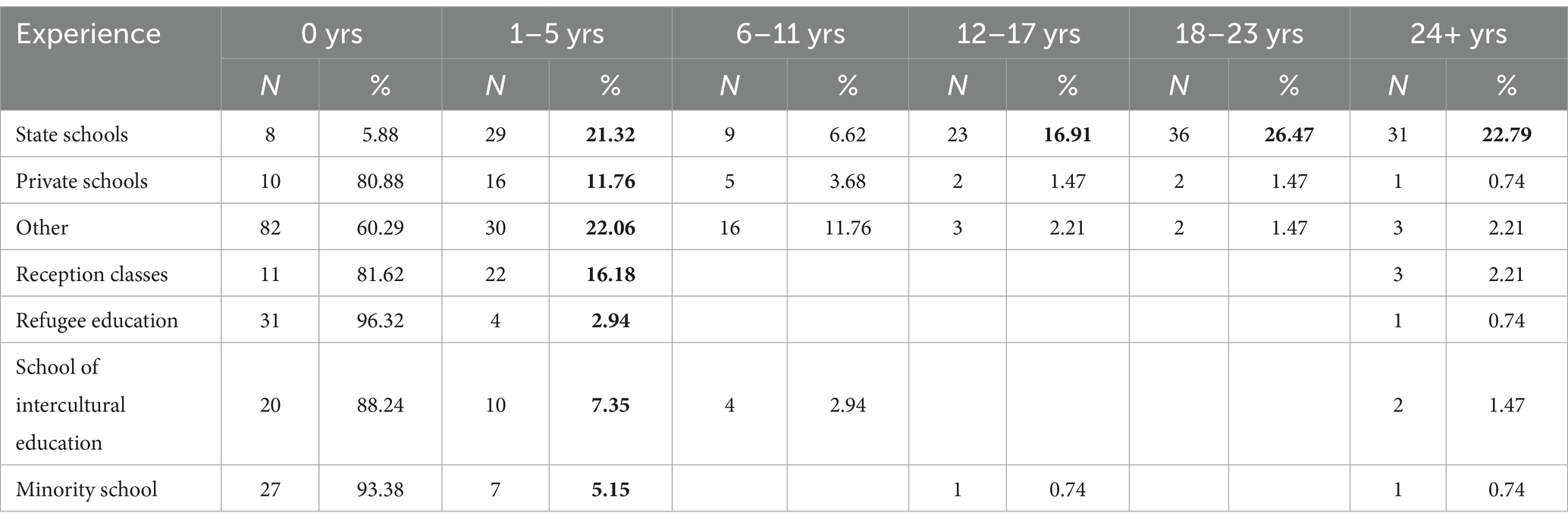

Teachers’ professional background included mostly teaching experience in the state sector (illustrated in bold in Table 1); all types of education included in the table below are state funded—except for the private schools. Regarding their teaching experience with L2 Greek students, in particular, this is relatively limited—between 1 and 5 years— (Illustrated in bold in Table 1) and includes mostly teaching experience in reception classes (16.18%) (Table 1).

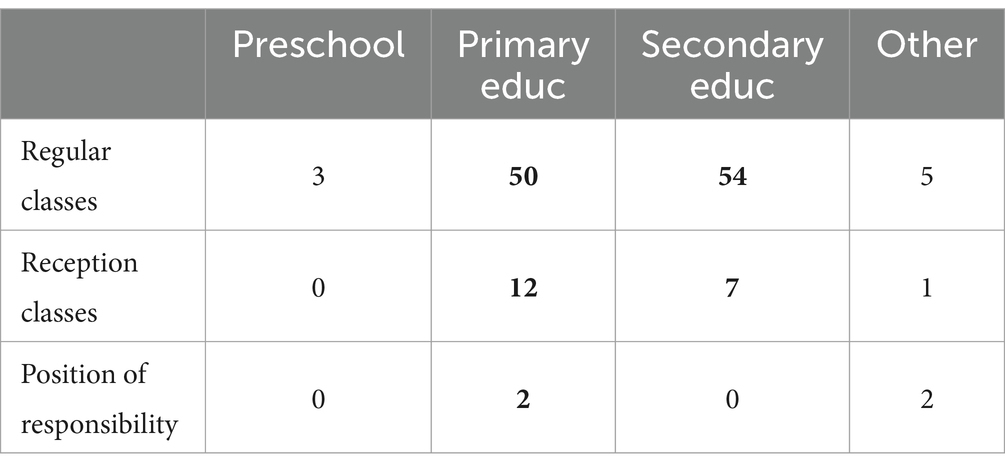

The following Table 2 illustrates respondents’ current position. This was an inclusion criterion for the data we next report: In particular, preschool educators were excluded from the analysis as the kindergarten curriculum is designed to be interactive and interdisciplinary promoting mostly if not exclusively oracy; also, due to learners’ very young age, instructional practices and techniques are quite different in preschool education from those adopted in primary and secondary classes. As a result, preschool educators (n = 3) were excluded from further analyses. The same applied for participants who were employed in structures working with both minors and adults (n = 8), as their answers included also references to adult education practices. Thus, in what follows we report on data from 125 participants (illustrated in bold in Table 2).

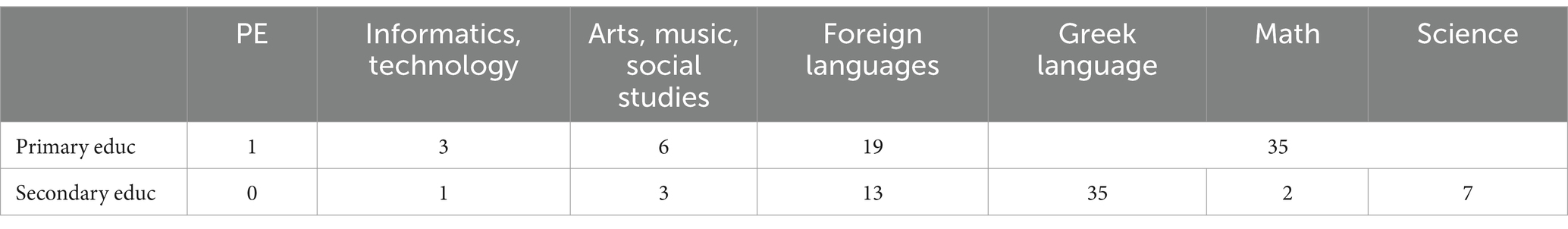

The group of primary school teachers included 64 participants (53 female, 11 male). Primary school teachers work with students between 6 and 12 years old and are required to teach a wide range of subjects including mathematics, Modern Greek, science and social studies, while subjects such as physical education, arts, music and foreign languages are taught by subject-specific teachers. Secondary education teachers included 61 participants (59 female, 2 male). They teach teenagers between 13 and 18 years old and have expertise in a specific subject area (e.g., Teachers of secondary education are employed in both junior high schools), i.e., the Greek Gymnasium (for ages 13–15 years), and senior high school, the Greek so-called Lyceum (for ages 16–18 years). The subjects taught by the 125 respondents of our sample are illustrated in Table 3.

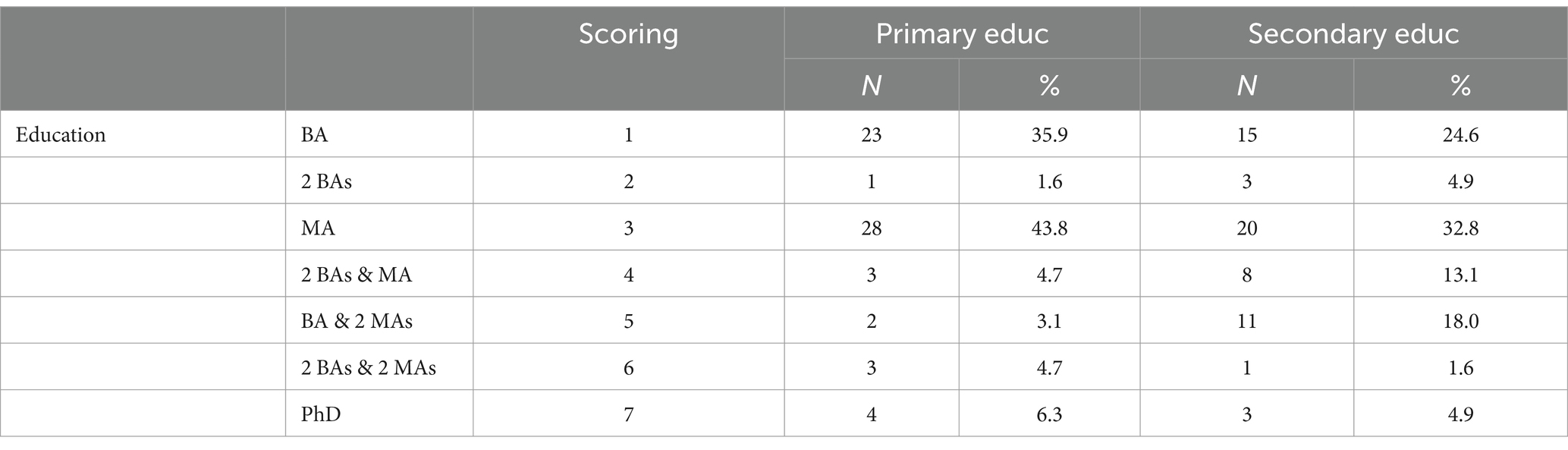

For participants’ educational background we created a composite score (see Table 4): 1 point was awarded to those who held one bachelor’s (BA) degree (n = 38), 2 points were given to holders of two BA degrees (n = 4), 3 points to those who had a BA and a Master’s degree (MA) (n = 48), 4 points were awarded to holders of two BA and one MA degree (n = 11), 5 to holders of a BA and two MA degrees (n = 13), 6 to holders of two BA and two MA degrees (n = 4), and 7 points were given to holders of a PhD (n = 7).

Approximately one-third (30.4%) of the participants held only one BA degree, 38.4% held both a BA and an MA degree, and 28% were holders of at least 3 degrees or of a Ph.D. Table 5 illustrates teachers’ academic profile per level of education.

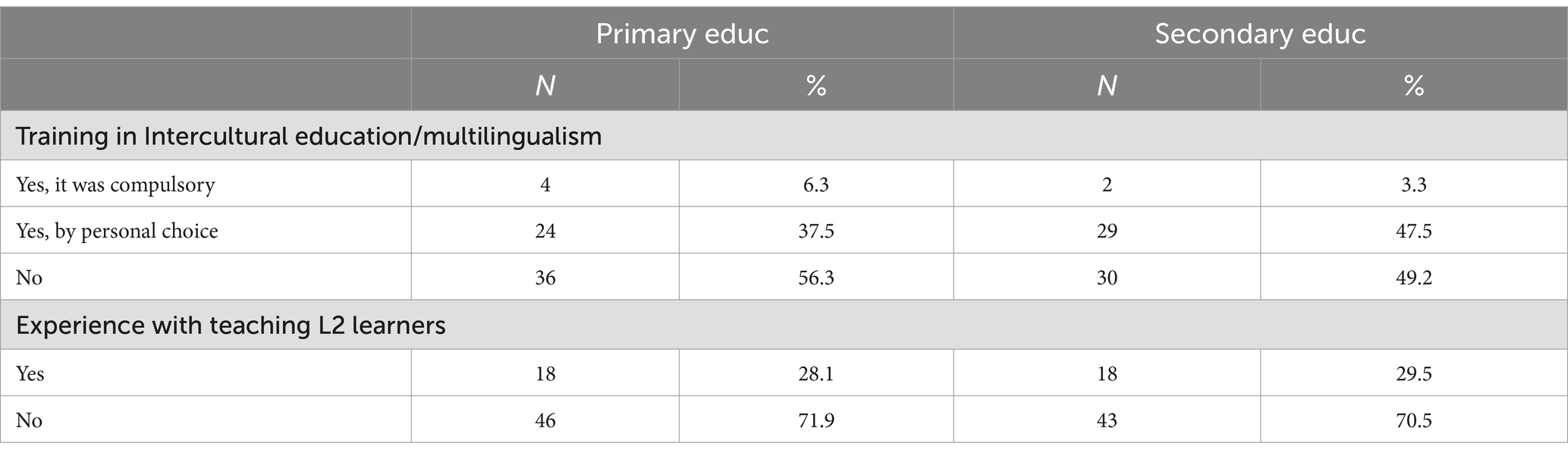

For the needs of the present study, we also considered whether participants had previously attended any training programs in intercultural education, in refugee and migrant education or in multilingualism, and whether this was their personal choice or a compulsory training they had to attend (coded as 0, 2 and 1 respectively). More than half of the participants stated that they had never attended similar training programs. Of those who answered ‘yes’, 37.5% of primary teachers and 47.5% of secondary teachers reported that they had attended them by personal choice (Table 5).

Finally, we were interested in investigating whether working experience with students coming from migrant or refugee backgrounds (see also Table 1) correlated with the teaching strategies they use. To this end, we coded the variable of previous relevant experience (yes = 1; no = 0), the latter case being much more common both among primary and secondary school teachers.

The primary and secondary education groups have equal population variances, as evaluated by the Levene’s test run for age (F(1,123) = 0.742), education level (F(1,123) = 0.030), training (F(1,123) = 1.779), prior experience in teaching Greek as L2 (F(1,123) = 0.115, all ps > 0.01), suggesting that educators of both school sectors have similar range of age, academic and professional backgrounds. The variables of gender (F(1,123) = 33.506, p < 0.001), teaching subjects (F(1,123) = 17.000, p < 0.001), and position -mainstream vs. reception classes- (F(1,123) = 10.340, p = 0.002) violated the homogeneity of variance assumption needed, and indicated that (a) our male respondents were mainly primary school teachers (t(1,123) = −2.594, p = 0.011), (b) assigned teaching subjects differ, though not significantly, between primary and secondary schools (t(1,123) = −0.912, p > 0.01), as already discussed, and that (c) reception class teachers came predominantly from primary education (t(1,123) = −1.779, p = 0.078).

As already stated, the present paper includes the lived experiences of five female participants (between 31 and 50 years old) who agreed to be interviewed in a follow-up session:

T1 is a primary school teacher in mainstream classes (age group: 31–40 years): at the time of the interview, she was teaching to a class of 17 3rd grade students; 5 of them had home languages other than Greek. She had previously worked with students from 1st to 6th grade and, in her interview, she shared experiences with those classes as well.

T2 is a teacher in Reception Classes (age group: 31–40): she had been teaching students with home languages other than Greek for 2 years. She shares her teaching experiences with small groups of students, which she created based on their proficiency level in Greek L2.

T3 is an ICT teacher (age group: 41–50): she has a long teaching experience in both primary and secondary education. In her interview she shared her experiences and focused on the period 2018–2024.

T4 is a language teacher in mainstream classes of secondary education (age group: 41–50): she has a long experience in teaching Ancient and Modern Greek, literature, history and social studies. In her interview she shared her experiences over the years, with a focus on the period 2018–2024.

T5 is a Refugee Education Coordinator (age group: 41–50): since 2018, she has been positioned in several camps of Northern Greece. In her interview she shared her experiences related to her assignment.

The various profiles of the interviewees gave us the chance to gain a broader picture of the challenges faced in a variety of primary and secondary school settings and shed light on the teaching strategies applied in both mainstream classes which host mixed student populations, as well as in reception classes, where students of L1s other than Greek are supported for their smooth transition into mainstream school settings.

4 Results

4.1 The questionnaire

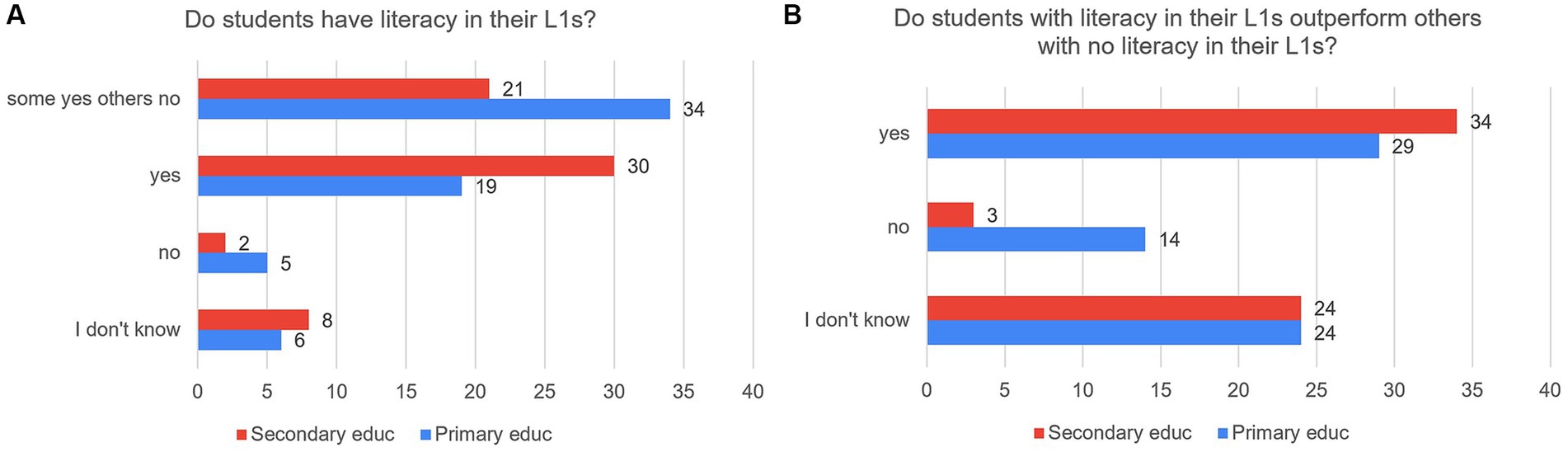

The first four questions of the questionnaire addressed the strategy of interculturality. In particular, the first two ones related to students’ biliteracy skills and examined whether teachers were aware of students’ literacy skills in their L1. A one-way Anova revealed a significant effect of the educational setting on teachers’ knowledge about students’ biliteracy (F(3,121) = 3.352, p = 0.021, η2 = 0.077). Most primary teachers acknowledged that some students have literacy in their L1, while others do not, while the most common response among teachers of secondary education was that their students are biliterate, a finding that may be linked to their students’ age (Figure 2A). On the other hand, in both educational settings, our respondents suggested that biliterate students outperform bilinguals with no literacy in their L1, although a large number of educators did not take a stand (Figure 2B). As expected perhaps, teachers who acknowledged their students’ biliteracy, also suggested that biliterate students outperform bilinguals with no literacy in their other language, as evidenced by a positive correlation between these two variables (r(123) = 0.422; p < 0.001).

Figure 2. (Α) Distribution of responses about students’ biliteracy; (B) Distribution of estimated students’ performance as a factor of biliteracy.

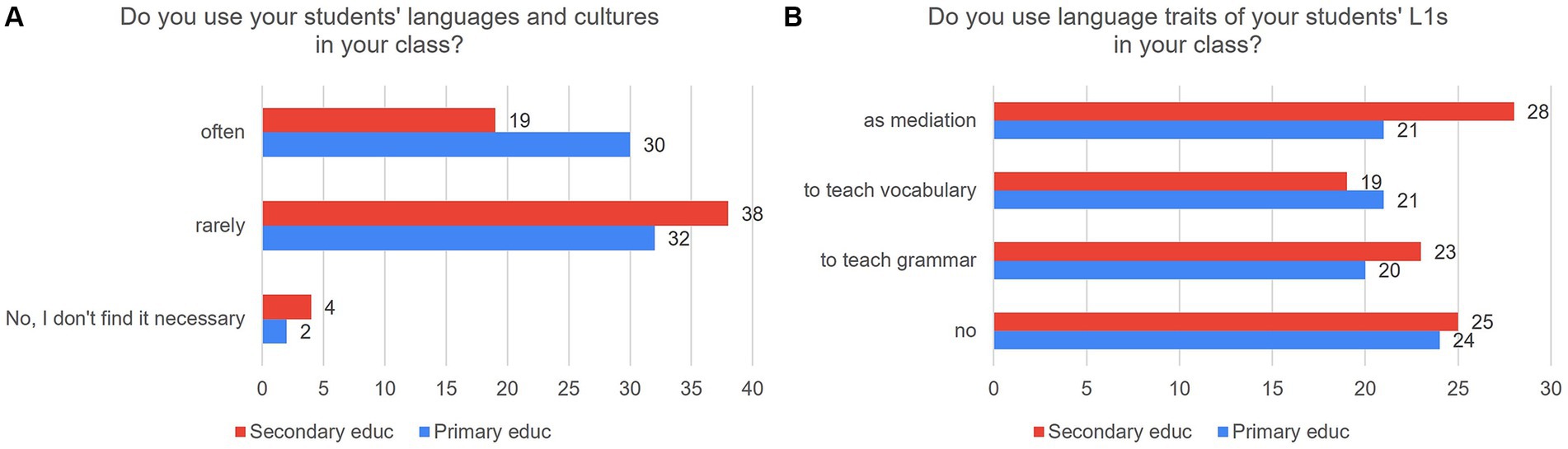

The next two questions examined whether teachers included students’ home languages and cultures in class. Respondents reported using their students’ L1 and cultures in class, but their answers indicate that they do so rarely rather than frequently, especially the secondary school teachers (Figure 3A). One-way Anova revealed a significant effect of the educational setting on the distribution of teacher responses (F(2,122) = 3.439, p = 0.035, η2 = 0.013). When asked whether they use features/traits of their students’ L1 in their class (Figure 3B), 37% of primary school teachers and 41% of secondary school teachers reported not using their students’ other languages (thus, in-class use of their students’ L1s—as self-reported and illustrated Figure 3A—was limited to non-language teaching topics). The rest of them reported using their students’ languages either for mediation purposes, or to make comparisons between the L1 and L2 vocabulary or grammar. Notably, teachers who used their students’ languages and cultures in their class extensively were the ones who also acknowledged their students’ biliteracy, as suggested by a positive correlation between these two variables (r(123) = 0.354; p < 0.001); they were also those who used linguistic traits of their students’ L1s to teach grammar/vocabulary or to translanguage (r(123) = 0.556; p < 0.001), and those who stated that biliterate students outperform bilinguals with no literacy in their other language(s) (r(123) = 0.257; p = 0.004). No significant correlation was found between the frequency of including students’ L1s in class and teachers’ educational and professional background. However, a significant correlation was found between the frequency of this variable and teachers’ attendance of training seminars on intercultural education (r(123) = 0.196; p = 0.029).

Figure 3. (A) Teachers’ degree of use of students’ languages and cultures in class; (B) Teachers’ degree of use of students’ L1s language traits in class.

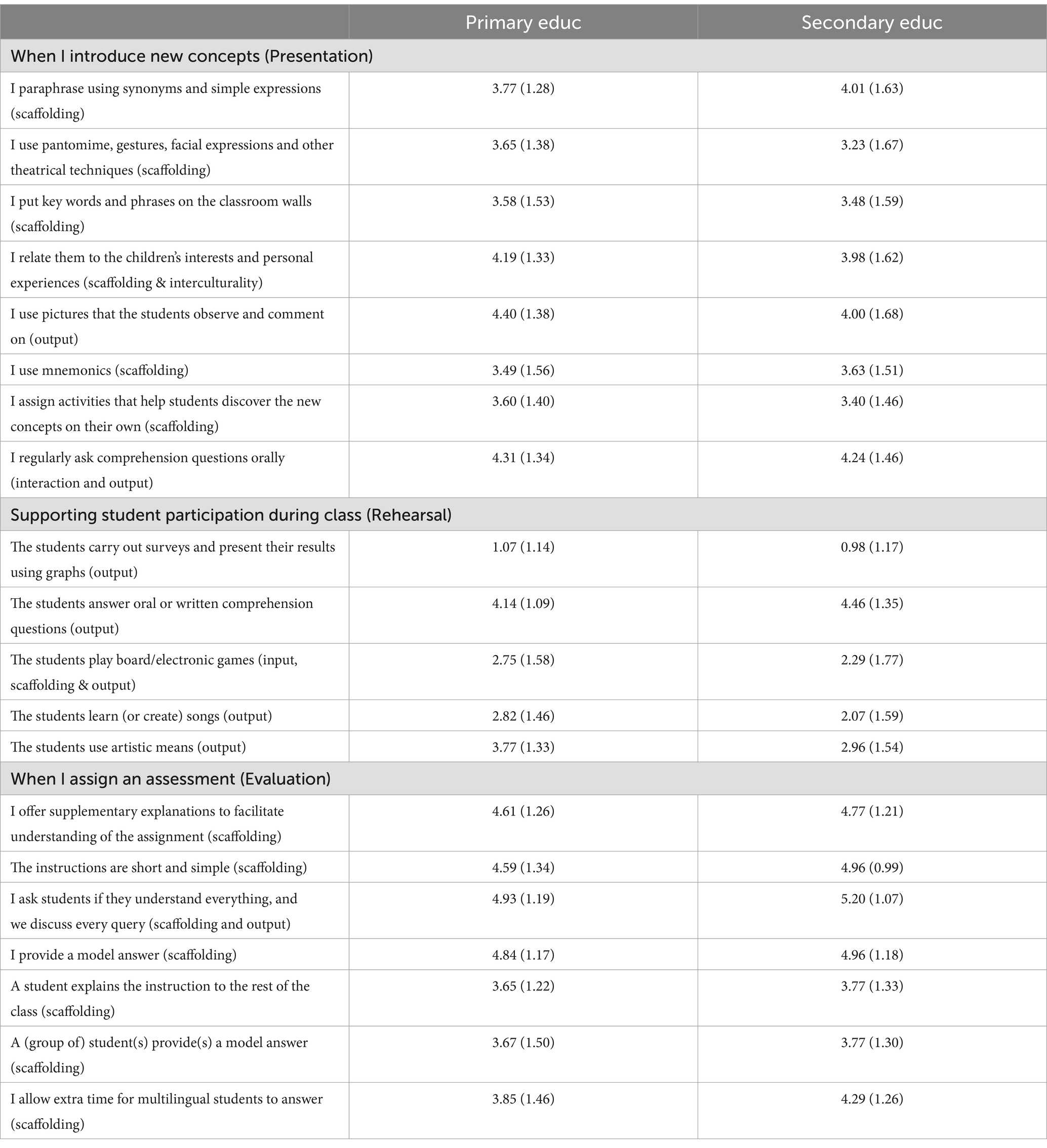

Next, we aimed to examine teachers’ use of 20 instructional strategies and their frequency of use on a 6-grade Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’ (and ‘no response’). We coded textual Likert scale responses into numerical values: never = 0 to almost always = 7; “no response” was coded as missing value. Cronbach’s A for these 20 items was α = 0.882, suggesting good internal consistency. The strategies studied included (a) eight strategies for introducing a new concept in class, (b) five strategies for supporting students’ participation in class, and (c) seven strategies to support assessment. Three separate questions were included in the questionnaire to tap on each of the above categories that corresponds to a distinct stage of the teaching process—presentation (introducing a new concept), rehearsal (supporting student participation), and evaluation (assessment). The strategies examined under each category can be found in Table 6. Each strategy has also been labeled following Meyer’s (2013) typology of CLIL strategies: (a) interculturality, (b) scaffolding, (c) rich interaction and pushed output.

The mean rate of teachers’ use of these strategies is illustrated in Table 6 per educational setting. We conducted one-way Anovas to investigate a possible effect of the level of schooling on each category of strategies. There was no significant effect of the educational setting—primary or secondary level—on the majority of the eight practices used by teachers when introducing a new concept. A significant effect of the educational setting was found on most of the five practices that support students’ participation in class, i.e., games (F(1,123) = 4.263, p = 0.041, η2 = 0.033), songs (F(1,123) = 7.950, p = 0.006, η2 = 0.061), and artistic means (F(1,123) = 10.636, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.080), with primary school teachers reporting using them more often than secondary school teachers [games t-value = n.s.; songs (t(117) = 2.685; p = 0.008); arts (t(119) = 3.099; p = 0.002)]. Finally, no effect of the educational setting was found on any of the seven assessment strategies.

With relation to teachers’ demographics, age significantly correlated with several of the above mentioned practices: the younger the teachers, the more frequently they reported using games (r(123) = 0.204; p = 0.022) when introducing a new concept, and the more frequently they offered supplementary explanations to facilitate understanding of the assignment when they assigned one (r(123) = 0.218; p = 0.015); also, the younger teachers are, the more frequently they ask comprehension questions (r(123) = 0.231; p = 0.009), provide a model answer (r(123) = 0.221; p = 0.013) or ask a student to provide one (r(123) = 0.185; p = 0.039), and the more frequently they allow extra time for multilingual students to answer (r(123) = 0.188; p = 0.036).

Narrowing down to each educational setting (see the full correlation table in Supplementary material 4), in primary education, teachers who use scaffolding strategies when introducing new concepts are consistent in this practice, as all of them correlate positively, i.e., teachers who use paraphrasing, they also use pantomime (r(62) = 0.318; p = 0.012) or keywords (r(62) = 0.551; p < 0.001), they relate content to learners’ interests (r(62) = 0.444; p < 0.001), they use visual aids (r(62) = 0.357; p = 0.004), assign discovery activities (r(62) = 0.354; p = 0.005), and regularly ask comprehension questions (r(62) = 0.435; p < 0.001), multiplying the opportunities for student familiarization with the new concepts. It is interesting to note that six teachers cited techniques they use, not included in the list of practices examined. In particular, one male teacher emphasized the use of role play, another male PE teacher mentioned using translanguaging with his students, and a female ICT teacher highlighted the supporting role of ICT tools. The remaining three female teachers emphasized the frequent use of songs, paintings and collage, fairy tales, narratives, and games. Similarly, secondary school teachers reported applying a wide variety of practices, as evidenced by the highly significant correlation found between, e.g., paraphrasing and pantomime (r(59) = 0.437; p < 0.001), use of keywords (r(59) = 0.664; p < 0.001), connection of the content to students’ interests (r(59) = 0.729; p < 0.001), use of visual aids (r(59) = 0.541; p < 0.001), mnemonics (r(59) = 0.645; p < 0.001), discovery activities (r(59) = 0.359; p = 0.006), and frequent comprehension questions (r(59) = 0.636; p < 0.001). In other words, secondary school teachers not only enhance their teaching by increasing the input, but they also provide support for the learning process and encourage active student participation. Eight language teachers provided a variety of techniques they use, including kinesthetic activities, photography, art, games (like crosswords and acrostics), applications (such as Quizlet), and translation into English.

Regarding the support of students’ participation in class, primary school teachers report using songs as well as games (r(62) = 0.382; p = 0.002), arts (r(62) = 0.504; p < 0.001), and oral or written comprehension questions (r(62) = 0.445; p < 0.001). No significant correlation was found between the use of surveys and other practices mentioned in the questionnaire. Participants suggested additional practices, including translanguaging, group work and having students take on the teacher’s role (proposed by one teacher). In secondary education, no significant correlation was found between comprehension questions and other practices, but significant correlations were found between other pairs of variables, such as songs and games (r(59) = 0.564; p < 0.001), arts (r(59) = 0.649; p < 0.001), as well as surveys (r(59) = 0.428; p = 0.001), the latter contributing to learning process scaffolding (O’Malley and Chamot, 1980; Chamot et al., 1999). Seven language teachers added further practices, namely, differentiated instruction, translanguaging, drama activities and role-play, projects and debates.

Finally, significant positive correlation was found among the output-oriented scaffolding practices that both primary and secondary school teachers use, when they assign an assessment. In particular, in the primary school level, the use of supplementary explanations to facilitate understanding of the assignment correlated with the provision of short and simple instructions (r(62) = 0.398; p = 0.001), asking comprehension questions (r(62) = 0.514; p < 0.001), providing a model answer (r(62) = 0.609; p < 0.001), asking a student to explain (r(62) = 0.492; p < 0.001) or to provide a model answer (r(62) = 0.441; p < 0.001), and allowing extra time for multilingual students to answer (r(62) = 0.581; p < 0.001). Similarly, in the secondary sector, giving supplementary explanations to facilitate understanding of the assignment correlated with giving short and simple instructions (r(59) = 0.417; p = 0.001), asking comprehension questions (r(59) = 0.540; p < 0.001), providing a model answer (r(59) = 0.405; p = 0.002) or asking a student to explain (r(59) = 0.350; p = 0.008) or to provide a model answer (r(59) = 0.471; p < 0.001), and allowing extra time for multilingual students to answer (r(59) = 0.523; p < 0.001).

A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted to reduce the dimensionality of the dataset containing measurements of the strategies in the three teaching stages: (a) when introducing new concepts, (b) when supporting participation, and (c) when assigning assessments. The Kayser–Meyer–Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (a) KMO = 0.896; (b) KMO = 0.747; (c) KMO = 0.840 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (a) χ2(28) = 666.153, p < 0.001; (b) χ2(10) = 145.693, p < 0.001; (c) χ2(21) = 597.718, p < 0.001 indicated correlations between items sufficiently large for PCA. (a) One component had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and explained 65.18% of the variance; (b) one component had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and explained 49.37% of the variance; (c) two components had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and together explained 78.03% of the variance: the first, called ‘structured instructional support’ (including strategies 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 of Table 6), explained 40.38% of the variance, and the second, called ‘student-centered activities’ (including strategies 5 and 6 of Table 6), explained 37.64% of the variance. These components were next used as a dependent variable to conduct multiple linear regression analyses and test whether the use of these scaffolding practices can be predicted by participants’ age, gender, educational background, training in intercultural education or other relevant topics, prior experience in teaching Greek L2 learners, school settings (primary/secondary), position in mainstream or reception classes and the subjects taught. The analysis applied backward elimination method and the final model for the techniques indicated that: (a) teaching subjects predicted statistically significantly scaffolding practices implemented in the Presentation phase (F(1,123) = 9.962, p = 0.002, R2 = 0.075); (b) school setting (primary/secondary), prior experience in teaching L2, training and the teaching subjects predicted scaffolding during Rehearsal (F(4,120) = 5.501, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.155), and (c) during Evaluation, age predicted the component named ‘structured teaching strategies’ (F(1,123) = 5.048, p = 0.026, R2 = 0.039), while training and teaching subjects predicted the component called ‘student-centered activities’ (F(3,121) = 4.860, p = 0.003, R2 = 0.108).

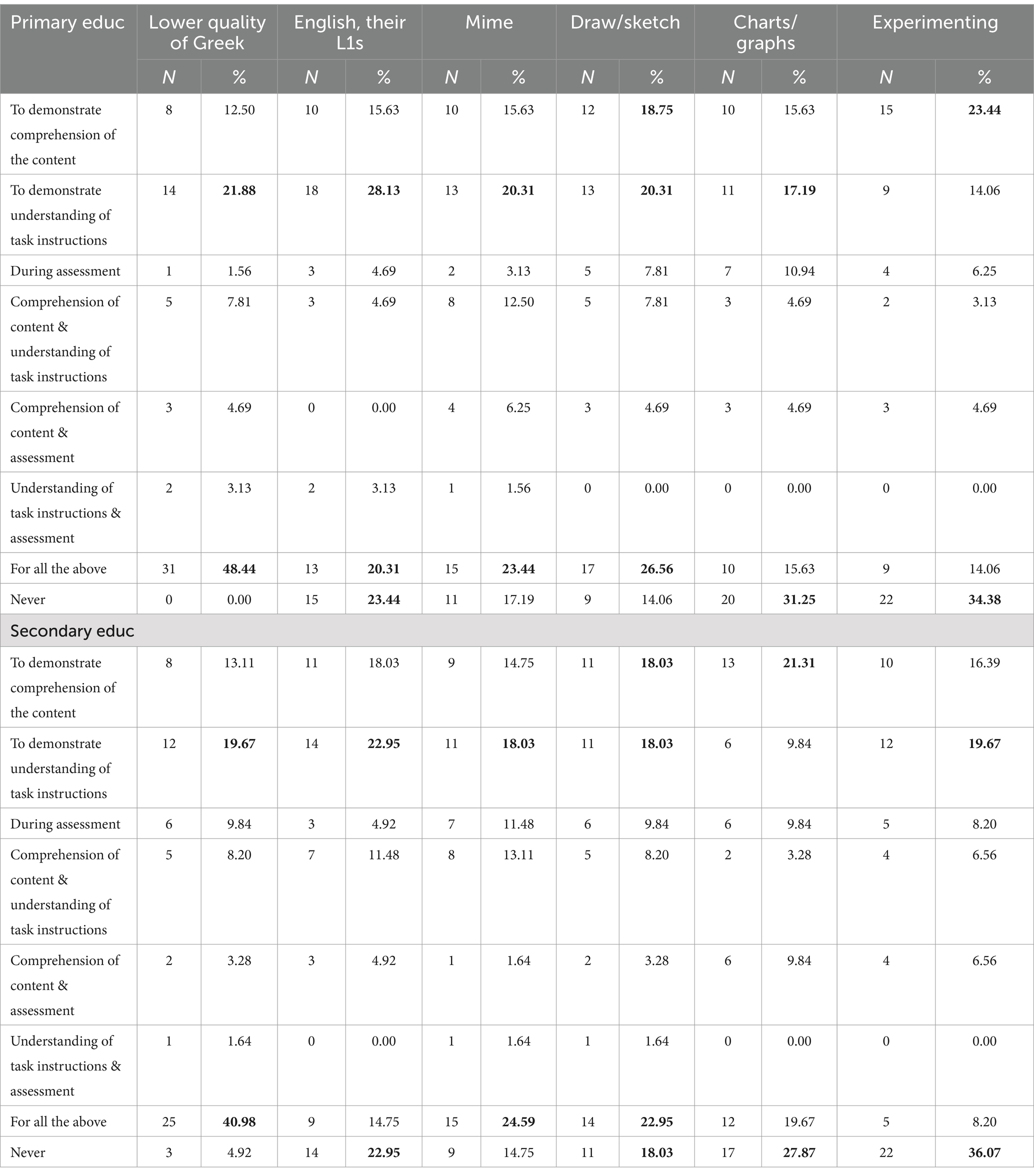

Finally, participants were invited to identify whether students are allowed or not to practice the following six strategies (a) to demonstrate comprehension of the content, (b) to demonstrate understanding of task instructions, and (c) during assessment. These strategies aim to boost learners’ output by allowing them to use any means available—linguistic or not.

1. Use everyday language and simple expressions in Greek

2. Use other languages they know (English, their L1s)

3. Mime

4. Paint/draw/sketch

5. Use symbolic representations (charts, maps, diagrams, pictures)

6. Use activities of active discovery (experimenting)

One-way Anovas revealed no significant effect of the educational setting on the six practices. As illustrated in Table 7, teachers in both primary and secondary education would prefer the use of simple, everyday expressions in Greek for all the proposed situations over any of the other output-oriented scaffolding techniques. However, around 10–30% of them, would additionally use most of the remaining suggested output-oriented techniques in order to give students the opportunity to demonstrate understanding of the task instructions. Symbolic representations (e.g., charts, maps and diagrams) are slightly preferred by secondary than primary school teachers, whereas activities of active discovery (such as experimenting) seem to be preferred by primary teachers. Use of languages other than Greek (English or their L1s) is not an option for more than 20% of teachers in both educational settings, while another 20% allow their students to demonstrate comprehension of the content, understanding of task instructions and during assessment. Finally, another 22–27% of the teachers allow their students to use miming or painting/drawing/sketching for the same purposes.

Some of these practices correlate with teachers’ demographic and academic or professional background: More specifically, young teachers allow students to mime more frequently than old ones (r(125) = −0.186, p = 0.03); teachers who reported having received training on intercultural education or bilingualism allow students to use other languages they know (English, their L1s) (r(125) = 0.269, p = 0.002) and favor miming more (r(125) = 0.224, p = 0.012) compared to teachers with no training. Additionally, teachers of reception classes allow their students to use simple everyday expressions in Greek (r(125) = 0.188, p = 0.03) and mime (r(125) = 0.191, p = 0.03) more frequently than teachers of mainstream classes; finally, the more experienced teachers are with teaching L2 students, the more they allow them to use their other language(s) (r(125) = 0.242, p = 0.007), simple expressions in Greek (r(125) = 0.187, p = 0.03), or mime (r(125) = 0.190, p = 0.03) in order to participate in the classroom.

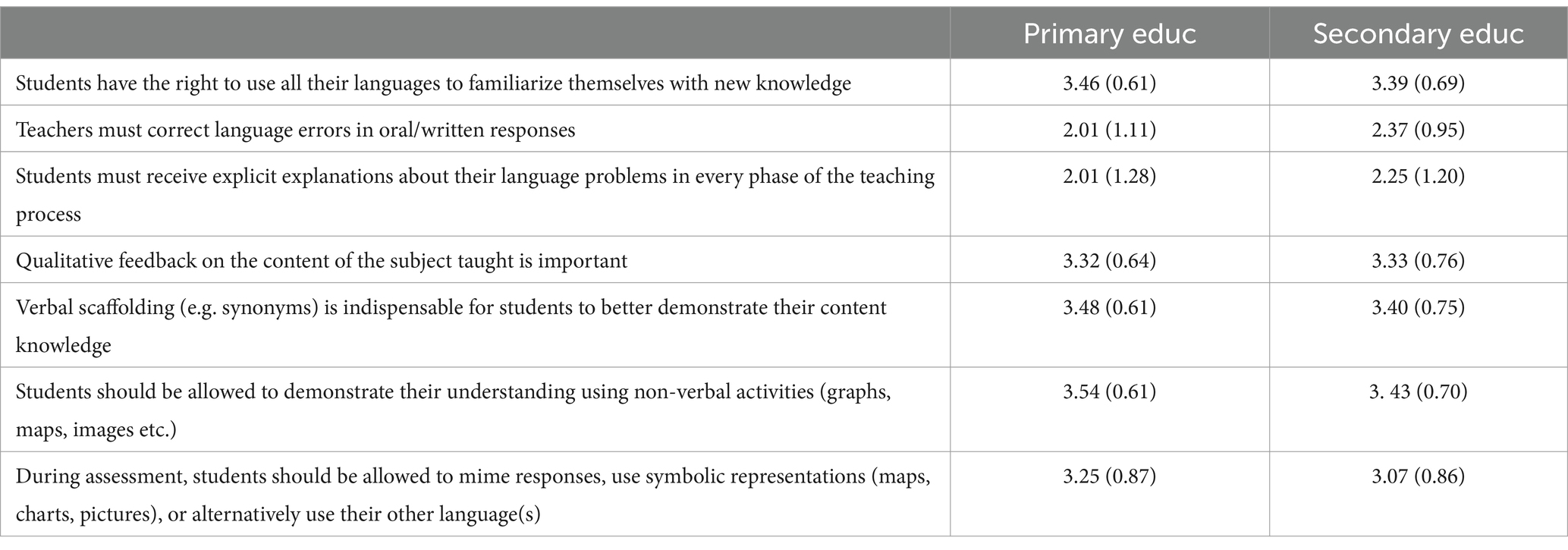

In the last section of the distributed questionnaire, we aimed to examine whether the actual practices of our respondents are in line with their beliefs on the opportunities students should be given, their rights and obligations. To this aim, they were required to indicate the degree of agreement with a set of seven statements on a 5-grade Likert scale ranging from ‘Totally disagree’ to ‘Totally agree’ and the option of ‘no response’; textual Likert scale responses were coded into numerical values: totally disagree = 0 to totally agree = 5; “no response” was coded as missing value (Table 8). Cronbach’s A for these seven items was α = 0.824, suggesting good internal consistency. Interestingly, primary teachers’ beliefs did not correlate with several of their self-reported practices in the previous sections of the questionnaire, but those of secondary teachers did (see Supplementary material 4 for Correlations Table).

We also examined whether their beliefs, as reflected in their answers to the question above, correlated with participants’ profiles. No main effect of educational setting (primary/secondary) was found on respondents’ mean rate of agreement with the suggested statements; instead, variation in their responses about verbal scaffolding correlated positively with their teaching position, i.e., whether they teach in reception or mainstream classes (r(125) = 0.182, p = 0.04), and with their participation in relevant training programs (e.g., on intercultural education, bilingualism, etc.) (r(125) = 0.200, p = 0.02). As the degree of agreement between all the statements was significant (Pearson correlations all ps < 0.05), we also conducted PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the dataset. The Kayser–Meyer–Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (KMO = 0.844) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2(21) = 421.207, p < 0.001) indicated correlations between items sufficiently large for PCA. The analysis identified two distinct factors, with eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 that together explained 73.45% of the variance: the first factor, named ‘instructional scaffolding’ was primarily defined by agreement on use of all students’ languages (0.786), qualitative feedback on content (0.768), verbal scaffolding (0.856), use of non-verbal activities to demonstrate understanding (0.889), and of non-verbal assessment (0.849) and explained 49.7% of the variance; the second factor, named ‘error correction’ was primarily defined by agreement on teachers’ duty to correct errors (0.844) and give explicit explanation about them (0.865), explaining 23.74% of the variance. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to test whether the use of these two factors can be predicted by participants’ age, gender, educational background, training in intercultural education or other relevant topics, prior experience in teaching Greek L2 learners, the school setting (primary/secondary), the current position in mainstream or reception class and the subjects taught. The analysis applied backward elimination method and the final model for the techniques indicated that the educational setting (primary/secondary) and training in relevant topics significantly predicted instructional scaffolding (F(2,122) = 5.319, p = 0.006, R2 = 0.080); no model fitted ‘error correction’ factor.

A final open-ended question invited participants to contribute, if they wished to, their thoughts or suggestions on the topic (57 responses). In several cases, respondents used this question to express their personal opinions regarding the challenges of multilingual classes in the Greek educational system, make teaching suggestions or express their needs. Some participants suggested that differentiated teaching strategies do contribute to better understanding of the content in all school subjects and stated that new teaching strategies are constantly tested in classrooms to fit students’ needs. Several of the participants stressed the importance of using English as a mediation language or alternative means of communication in class, like miming and the arts, drama activities, painting, photography, music and dance, to facilitate communication with the L2 learners but also to create a welcoming environment for them. These teachers also underlined the right of children to have access to their own languages and use them in class if this can support their understanding and participation. An interesting comment came from a teacher who said:

“Students particularly enjoy organizing events that showcase their own creations, such as painting and photography exhibitions. They also take pleasure in organizing visits to various sites where they assume the role of guides” (P 30).

And somebody else suggested that “…such practices are very helpful even for monolingual students” (P 21).

A lot of educators stressed the need for further training, and in particular, practical training in teaching multilingual and highly diversified student audiences, since their university studies do not equip them with relevant skills. It is interesting to note that this was mainly expressed by primary rather than secondary school teachers.

Some participants provided their personal opinions and suggestions based, apparently, on their personal experiences. Some of these opinions are contradictory but this is inevitable since they reflect different teacher experiences, attitudes and beliefs regarding intercultural education. In particular, one teacher stated:

“Students have a lot of potential and they wish to be part of the school community. When the community supports them, they can do miracles. However, the Greek educational system does not support the development of other languages. There needs to be support for the students to integrate socially, for their parents to get involved in the school community, but also for Greek L1 students to develop intercultural skills.” (P 72)

On the other end, another teacher provided a completely different view:

“There is no room for other languages in the school setting; the exclusive use of Greek in class is the only way to help L2 learners to acquire it.” (P 109)

A more realistic perhaps suggestion was made by the following participant:

“All Greek teachers need to train in intercultural education as all Greek schools will soon become intercultural.” (P 3)

4.2 The interviews

In what follows we are going to identify themes that emerged in the interviewees’ responses through recurrent references and comments. The main purpose of our interviews was to zoom in on the actual strategies and teaching practices adopted by those educators in their effort to integrate language and content in their multilingual classes. Some of their responses reiterate information already collected through the questionnaire; however, some of the details provided in the interviews allow us to gain deeper insight and better understanding of the rationale behind the choices described. The themes identified in the interviewees’ responses and briefly discussed in this section are as follows:

a. The use of differentiated instructional strategies

b. The need for appropriate materials and resources

c. The use of differentiated assessment

d. Issues of linguistic diversity, interculturality and inclusivity

4.2.1 Differentiated instructional strategies

The use of differentiated instructional strategies and their role in supporting student understanding of content and language is one of the recurring themes in teachers’ responses. Especially in the reception class where learners have limited or no knowledge of Greek, the teacher emphasizes the need to use pictures to explain the vocabulary, to engage in games, and to use model expressions that help learners acquire lexical chunks without resorting to grammar or syntax rules:

“To teach the word-order, I ask oral questions such as ‘What color is the table?’ and provide the model answer ‘The table is brown’: The children answer in a playful way questions on the color of objects in the classroom, but they are in fact learning grammar; the word-order, the gender agreement, etc., depending on the pre-specified teaching aim. With students of higher proficiency level in Greek, I introduce new concepts translating the demanding vocabulary in their L1s using google translator. When I assist students in the mainstream class (co-teaching), I work in close collaboration with the teacher of the class: we prepare different versions of assignments, so that all students can participate in the class.” (T2).

When it comes to curricular content, teachers report on adapting the language to accommodate their L2 learners’ needs:

“Math is always ok; we start with a short recap and proceed. Solving math problems is a different story, because language is demanding even for monolingual Greek speaking children. I delete misleading information that is often included to help them distinguish the necessary information to solve the problem, and I lower the language level by avoiding subordination or low frequency words.” (T1)

One of the interviewees who works in primary education suggests that role plays, video projections, graphs and illustrations help them involve learners and balance the teaching of language and content since children learn and practice speech acts depending on the situation. As an example, she cites the ‘grocery store’, a role-play activity that requires students to go to the school canteen and practice conversation skills but also arithmetic operations.

When talking about secondary school students, one teacher referred to the use of project-based learning which allows the implementation of interdisciplinary approaches but also gives more space to students to develop their critical skills, improve their L2 skills but also acquire knowledge relevant to their age and interests:

“Project-based learning is also very important. I can remember two examples. First, we visited a radio station and a TV channel. Students learned about the properties of the news reading discourse and about the conventions to follow when interviewing ordinary people or politicians. For the former, we filmed a newscast, which was aired by the local channel and the children were enthusiastic. For the latter, the children took up roles (a citizen, a politician, an official, a journalist) and interviewed each other in class. The experience was fascinating. For some time afterwards, they watched the news with their parents and came back to school with comments and impressions on what they saw.” (T1)

4.2.2 Materials and resources

Another recurrent theme in teachers’ interviews relates to the need for appropriate materials and resources used in their multilingual classes. The following reception class teacher refers to her collaboration with mainstream class teachers for the creation of materials.

“In reception classes, we have the freedom to define our own curriculum based on students’ needs, as it is not pre-specified by the ministry of education. Thus, we can adapt the materials we use in relation to the availability of resources. I usually turn to the other schoolteachers to collaborate; (…) we mostly focus on language development and cooperate in working with activities of creative writing.” (T2)

The following teacher also points at the value of collaboration with colleagues for the creation and sharing of resources given the lack of relevant materials:

“… we strive to learn from our own experiences, from colleagues, and from resources we find ourselves. For example, when someone discovers an app and finds it effective after testing it in class, they share it with other colleagues. I have often had the opportunity to demonstrate tools that I use to my colleagues, who then incorporate them into their teaching as well.” (T4)

Another teacher focuses on the importance of alternative resources like interactive boards, YouTube, and applications for supporting student comprehension:

“The use of interactive boards in most Greek public schools is highly beneficial. (…) Students are especially enthusiastic about YouTube videos and games in applications like Kahoot, or collaborative activities in digipad or padlet. I incorporate these resources to enhance content comprehension in at least every other lesson.” (T4)

“Scratch, Jigsaw are ready to use. The platforms have the option to turn to their L1s (or other languages they may speak).” (T3)

4.2.3 Differentiated assessment

The assessment of Greek L2 learners in classes that are mostly monolingual is a challenging and time-consuming task for those educators, as it requires them to design customized assignments and assessments. However, as the following excerpt indicates, they realize the value of this extra work for the long-term benefit of their students.

“For the assessment, I create questions of grading difficulty; for homework I create several sets, usually two or three, according to my students’ knowledge level. Although it takes a lot of personal effort to do that, it is important to get their homework done. Otherwise, either someone from home helps them, or they come to school without having done their homework.” (T1)

Alternative types of assessment, such as competitive games, are to be preferred according to one teacher as she feels that she can get “more important and profound information about their acquired knowledge…. because children are not stressed.” (T2).

The same teacher describes in detail another alternative type of assessment, teacher diaries, which are used in a very targeted way. This method helps her track her students’ progress but also their preferences and learning styles. Diaries also act as a reminder for follow up work, e.g., further practice activities and other material appropriate for the language needs of the specific student.

“I alternate across assessment methods to gain a deeper insight of my students’ progress. For example, I keep a diary of their achievements: I always have a notebook by my side and keep notes whenever necessary. This way, I can go back to my notes and recall the child’s needs, the teaching practices that were proved effective, some song or game they mostly liked and any other relevant information. For example, when a student narrates a story and I notice grammar errors, I take a note and I set a relevant teaching aim for a follow-up class for which I prepare the necessary material; in this case I do not give feedback on the language errors, if the task was designed for a specific content or for another language skill, as for example to promote oral production.” (T2)

The use of traditional types of testing is also mentioned, interestingly as a way to increase multilingual students’ self-esteem: “Of course, I sometimes give them a short, structured test, which children like, because they feel that they are starting to fit in the ‘real education system’.” (T2)

4.2.4 Linguistic diversity, interculturality and inclusivity

One of the main themes that was repeatedly raised, directly or indirectly, in the interviewees’ responses related to the use of multilingual students’ languages and cultures in class. More than one teacher made reference to the need to acknowledge those students’ languages, ethnic and cultural background in class, as this has a positive impact on their motivation and self-esteem:

“I remember a Kurd student, when he was invited to use his L1, he immediately gained interest and became responsive to the needs of the class.” (T3)

Interviewees also referred to the value of translanguaging as an inclusive pedagogical practice, since it helps educators support student understanding, promotes communication with teachers and peers and boosts L2 learners’ motivation. In Tai’s words (2022: 975), the teacher in similar settings needs “…to mobilize various available multilingual and semiotic resources and draw on what students know collectively for transcending cultural boundaries from the students’ everyday culture to cultures of school science and mathematics.”

“A year ago, in my class there were some Chinese-speaking children with no knowledge of Greek. In that case, translanguaging was the key approach to making things work. We managed to communicate and started learning the basics with many visual aids, pictures, and games, while the children mostly mimed to demonstrate understanding.” (T1)

The usefulness of miming or of other alternative—nonverbal—means by students to demonstrate understanding has been also underscored by Echevarría et al. (2010) who claim that students may be allowed to mime responses or demonstrate their understanding by using the symbolic representations found in charts or pictures. Alternatively, other practices include the use of code-switching, and the use of English or any other language students can master.

“We often ask newcomers to write or answer orally in English. Moreover, I often give some activities of creative writing, in which children can code-switch and incorporate all the languages of their repertoire.” (T4)

The following secondary school teacher makes an interesting contribution regarding her practices for promoting linguistic and cultural diversity and inclusivity in her class:

“Instead of using students’ native languages in the classroom, we focus on encouraging them to speak in Greek about their personal experiences, customs, food, and music from their countries of origin. However, there are some examples which promoted the use of children’s L1s that I can share with you. The first one is my class participation in the international competition of plurilingual kamishibaï, a blend of theater and storytelling originating from Japanese tradition. Also, utilizing language autobiographies has proven very effective, allowing children to open, and fostering a stronger bond among them.” (T4)

5 Discussion

Due to the mass migrations in southern Europe over the past 10 years, the landscape of Greek language education has changed significantly, as large numbers of immigrant and refugee students of various ages, ethnic backgrounds and L1s have joined mainstream classrooms (Chatzidaki and Tsokalidou, 2021; Mattheoudakis and Maligkoudi, 2025; Olioumtsevits et al., 2022, 2023). This change of student population in the Greek state schools had an obvious impact on teachers’ needs and called for immediate action on the part of the Greek state, which reactivated the use of reception classes. However, we still have not seen a state-organized and systematic effort to equip current and prospective Greek teachers with the skills and resources needed to address the challenges faced in their multilingual and multicultural classrooms. Attendance of teacher training programs, workshops, seminars and webinars on bilingual and intercultural education have been mainly organized by private organizations, NGOs and university departments and their attendance is optional. An interesting initiative undertaken by the Ministry of Education in collaboration with UNICEF is the program Teach4Integration,4 launched in 2021. The program has been successfully running for 3 years in three different geographical locations in Greece and targets state primary and secondary school teachers. Teach4Integration provides educators with the knowledge and skills required to address the challenges of multilingual classes, but attendance is not compulsory.

Given this lack of systematic and organized state support, teachers are left to experiment with various methods and approaches when teaching multilingual classes. As they find themselves in a situation which requires them to teach curricular content in (L1) Greek but also Greek as a second language and curricular content in (L2) Greek, they need to adopt instructional strategies appropriate for bilingual education settings. These are strategies commonly adopted in CLIL classes, as CLIL promotes the teaching of curricular content in a language other than students’ L1and allows teachers to address both content and language objectives without sacrificing the one for the sake of the other.

As information about the actual instructional choices teachers make in multilingual classes is scarce, our study aimed to investigate the instructional strategies employed by educators working at schools with large numbers of migrant students in various parts of the country; these were self-reported by teachers who volunteered to participate in our study by answering a web-based questionnaire. Participants were not provided with any information regarding the objectives of our study so as to minimize the risk of volunteer bias. Also, as their answers indicated, none of these teachers had received any training in CLIL methodology, during pre- or in-service education; this finding further minimizes the risk of self-selection bias, since participants’ limited theoretical knowledge and training in CLIL would be expected to discourage them from participating in a study related to CLIL.

Our study analyzed the answers of 125 primary and secondary school educators working in 21 different regional units of Greece; this number reflects a good geographical dispersion of the participants. Respondents were mostly women and covered a wide age range, mainly between 30 and 60 years of age. Almost half of them worked in the primary school sector (64) and the rest were secondary school teachers. Regarding their position at the time of the survey, only 19 of them worked in reception classes, the majority being mainstream class teachers. Regarding their teaching experience, this came mainly from the state sector; their teaching experience with L2 Greek learners, in particular, was very limited—between 1 and 5 years—and included mainly instruction of reception classes. The vast majority of the participants are highly qualified with 2/3 of them reporting being holders of at least one MA or a Ph.D. Finally, with respect to their training, as already stated, more than half of the educators participating in the survey stated that they had never received any type of training in bilingual and intercultural education, in CLIL methodology or in the teaching of L2 Greek to speakers of other languages, thus confirming our expectations.

In what follows we are going to discuss the use of CLIL strategies by the respondents following Meyer’s typology and focusing on the strategies of interculturality, scaffolding, and pushed output. We are also going to discuss to what extent teachers’ use of those strategies is influenced by their age, educational background, teaching experience, previous training, and educational setting (primary or secondary). The lack of similar studies in the use of CLIL strategies with immigrant student populations in other European countries does not allow us to compare our findings with those of other studies. In a research review, Somers (2017) examined the comparative suitability of CLIL programs for immigrant minority language students by reviewing 9 studies which took place in Belgium, England, Germany, and Sweden between 2010 and 2016. Based on his review, the findings of these studies highlight the positive impact of CLIL programs on immigrant students’ levels of proficiency in both the majority and the additional language as well as on their overall academic achievement in comparison to non-immigrant students (Steinlen et al., 2010; Steinlen and Piske, 2013, 2016; Steinlen, 2016 in Somers, 2017). However, none of those studies examined or even discussed the use of strategies employed in the CLIL settings researched.

Interestingly, participants’ educational background was not found to have an impact on any of the strategies used. One reason for that may be the fact that the vast majority of the participants were highly qualified and therefore the particular variable could not have a differentiating function. On the other hand, participants’ expertise and teaching subjects were found to predict the strategies used at the Presentation stage of the lesson as well as scaffolding at the Evaluation stage; however, it was not possible to draw further details and make any generalizations, as the number of educators for some teaching subjects was particularly low.

As regards the promotion of interculturality, teachers’ answers to the corresponding questions (Figure 3) indicated that they rarely incorporate or showcase in any way multilingual students’ L1 and home cultures in class; secondary school teachers significantly less so than their colleagues in primary schools. According to these teachers, references to students’ L1 serve mainly teaching or communication purposes—comparisons between Greek and L2 language features or as a mediation tool—rather than the conscious promotion of intercultural awareness and multilingualism. These findings were not unexpected, as similar results were obtained in previous studies conducted with state school educators in Greece by Fotiadou et al. (2022) and also with state school teachers in three European countries, Greece, Italy and the Netherlands (Bosch et al., 2024). In the present study, secondary school teachers’ reluctance to include L1 learners’ language and cultural features may be related to the higher demands placed on them by the secondary school curriculum, the attainment of particular learning outcomes and the perceived time constraints. The fact that some of them do resort to learners’ L1 for communication or teaching purposes indicates that teachers are able to create connections and build bridges between the two languages and/or cultures. However, they do it out of necessity—to fulfill the teaching aims and communicate with those students—and not for raising all students’ intercultural awareness. Such choices indicate that teachers do not perceive the diversity among their students as an opportunity for cultivating intercultural skills or for promoting intercultural awareness (see also Mattheoudakis et al., 2017; Olioumtsevits et al., 2024 for further discussion).

Our analysis also showed that teachers who promoted interculturality were also those who were interested in their students’ L1 literacy development, as they were aware of its importance for students’ academic and emotional development (cf. Somers, 2017) (Graph 2). Finally, and quite predictably, the analysis revealed the importance of teacher training for the development of educators’ intercultural awareness and the adoption of similar strategies. Similar findings were also reported by Gatsi et al. (2023) and also in the Teach4integration “Ekpedefsi gia tin entaksi” (2023) evaluation report, which was based on educators’ feedback after completing their attendance of the relevant training program (see also Mohammadi et al., 2023). In fact, our findings indicated that the more training seminars teachers attended, the more interculturally aware they were and the more inclusive approaches they reported adopting. Although these findings may come to no surprise, they need to be stressed as they have important implications for the re-design and updating of tertiary education departments’ curricula but also for policy designers so as to urgently address teachers’ and students’ needs in multilingual educational settings (see also Bosch et al., 2024).

With regard to scaffolding, this is significantly affected by teachers’ age. The younger the teachers, the more scaffolding strategies they employ, mainly at the evaluation stage of their lesson (Table 6, see also Supplementary material 4). Scaffolding in this case is used to increase the chances for successful performance and thus improve students’ self-esteem and motivation. The choice of the particular strategy by younger teachers and therefore, more recent university graduates, may reflect a change of curricula in tertiary education aiming to equip students of educational departments with appropriate training and skills required in contemporary school settings (see also Maligkoudi et al., submitted/under review). Also, the regression analysis indicated that (a) educational setting (primary or secondary) and (b) training predicted instructional scaffolding type. Although scaffolding techniques are used consistently and systematically in both primary and secondary education, teachers in the respective sectors adopt different types of scaffolding strategies: primary school teachers opt mainly for miming, paraphrasing, visual aids, discovery activities, relating content to learners’ interests and experiences. On the other hand, secondary school teachers report using a variety of techniques such as kinaesthetic activities, photography, and games, which are usually not typically found in secondary school settings. Such choices, which are rather unconventional for the Greek secondary school setting, aim to boost L2 learners’ comprehension but also to bridge the gap between L1 and L2 speakers’ language and academic performance. They further underline teachers’ awareness of the need to adopt alternative instructional strategies, even if their training and/or experience do not support them.

The promotion of pushed output is affected by the educational setting, especially at the second stage of the teaching process—rehearsal (Table 7). Primary school teachers report using strategies such as games, songs, artistic activities but also translanguaging more often than secondary school teachers. The pedagogical value of using similar strategies with primary school learners has been supported in recent studies as they have been found to promote linguistic, cognitive and emotional development (Tribhuwan et al., 2022; Paraponiari and Mattheoudakis, 2025, among others). With respect to the use of translanguaging in particular, Leonet and Saragueta (2023) found pedagogical translanguaging useful since it facilitates language comparison and scaffolds understanding and written production (see also Franck and Papadopoulou, 2024, for the feasibility and emotional impact of pedagogical translanguaging). If primary school teachers promote learners’ output more than their secondary school peers, this means that primary school learners are possibly given more opportunities to increase their output and therefore to develop their linguistic skills. Having said all the above, we need to acknowledge the variety of output strategies secondary school educators reported using: songs, games, arts, surveys, drama activities and role plays, projects and debates, among others. These are obviously cognitively and linguistically more challenging activities compared to the ones employed by primary school teachers, but they are also more appropriate for the age of secondary school learners.