- Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

This study examines the experiences of five Kansan parents who took on a key role in their children’s home education during the pandemic. The author uses online interviews to investigate how parental agency is manifested through parents’ actions regarding children’s education and health. Drawing inspiration from Bandura’s theory on human agency, the study applies four core properties of agency: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness. The discussion connects the findings to the broader literature on agency, offering insights into how families navigate challenges and support children during crises such as the pandemic.

Highlights

• This study utilizes qualitative methods through interviews with Kansan parents who took on a key role for the education and schooling of 10 children (under 18 years old) at home during the pandemic.

• The author examines how parental agency is reflected in the parental choices and educational strategies during school closure at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic using Bandura’s properties of human agency concept.

• These findings provide insights into how families may respond to challenges in supporting their children in adverse situations, such as building on their agency to target all four core properties of agency framed by Bandura, including intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness.

Introduction

Researchers have described the COVID-19 pandemic as “adverse situations” with the potential to disrupt normative functioning (Gniewosz, 2022). It introduced widespread societal and familial challenges, including disruptions to education, heightened stress levels, and altered communication patterns between parents, children, and the outside world (Gniewosz, 2022; Hoskins et al., 2023; Koskela, 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Patrick et al., 2020). This global pandemic also fueled a growing interest in alternative forms of education, leading to a notable rise in homeschooling across the United States (Eggleston and Fields, 2021; Musaddiq et al., 2022). Based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, more than 10 % of Americans homeschooled their children in 2021, nearly doubling the rate from 2020 (Eggleston and Fields, 2021; Musaddiq et al., 2022).

Studies on families in crisis and adverse situations has provided valuable insights on families with children globally (Darragh and Franke, 2022; Hoskins et al., 2023; Koskela, 2021; Trotta et al., 2024). For example, Trotta et al. (2024) examined the effects of the pandemic-led school closure in Italy and identified an increase of difficulties of distance education to families of primary school students (p. 25). Hoskins et al. (2023) revealed that pandemic-induced changes brought both opportunities for learning and significant pressure on British and Chinese families with children (p. 6). Darragh and Franke (2022) captured parents’ responses in children’s mathematics learning during the pandemic in New Zealand, and reported both parents’ positive and negative experiences (pp. 1534–1537). Koskela (2021) explored parents’ agentic experiences, either grateful or critical, in negotiating support for children in Finnish schools, and found importance of such agency in supporting children’s needs (p. 10).

To learn about the potentials and capabilities of human beings facing adverse situations like the pandemic and to spark positive changes, the concept of agency has captivated the attention of scholars across a wide range of social science disciplines, such as anthropology, psychology, sociology, and education (Ahearn, 2001; Bandura, 2006; Biesta et al., 2015; Sen, 1985). Agency has long been considered a key component underpinning human wellbeing and a pivotal factor in indicating how individuals respond to external changes (Brown and Westaway, 2011; Sen, 1985; Vidyarthi et al., 2021). As a multifaceted and situational concept, agency encompasses the capacity of individuals to make choices, take action, and shape their own lives within their social, cultural, and institutional contexts.

In education, scholars have increasingly focused on parental agency and its relationship to personal wellbeing and children’s education. Parental agency generally refers to the capacity of parents in shaping their children’s educational experiences and overall wellbeing (Koskela, 2021; Vincent, 2001). Studies have explored how parents engage with their children’s educational institutions, advocate for their children’s needs, and support their children’s learning and development (Dennison et al., 2020; Griffiths et al., 2004; Hartas, 2008; Koskela, 2021; Mcclain, 2010; Morris, 2004; Rall, 2021; Rix and Paige-Smith, 2008). Moreover, researchers have emphasized its critical role in supporting minority children within their communities (Curdt-Christiansen and Wang, 2018; Fernández, 2016; Guo, 2021; Kulis et al., 2016; Moustaoui Srhir, 2020). These studies highlight the importance of parental agency in shaping children’s educational processes, educational outcomes, and wellbeing across various cultural, socioeconomic, and racial contexts.

Despite this growing body of research, there is a noticeable gap in studies on families’ home education experiences during the pandemic. Further investigation into diverse families—especially those from different racial and ethnic backgrounds—is necessary to enhance current social science research. In-depth studies on Chinese homeschooling families, in particular, would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the home learning experiences. Overall, knowledge about the agentic experiences of Chinese families is limited. Examining how parents’ pandemic-related challenges and how they supported their children can provide valuable evidence on factors that either strengthen personal confidence, parenting skills, and inspire positive changes in constrained situations and contexts. Interpreting parental agency with the pandemic context and seeking factors related to agency can illuminate research and practice to support more families.

Methods

This study examines the multifaceted home education and agentic experiences of Chinese-American parents with children aged six-18 during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kansas. The focus on Kansas stems from the author’s experience and research expertise in the local education policy and research community, especially after a state initiative that started in 2017 and highlights the social–emotional development of Kansan children (Erickson, 2020; Miller, 2020). The decision to focus on Chinese families has been based on the cultural and linguistic strengths of the author as a Chinese and bilingual researcher who has lived and studied in Kansas for the past few years.

Home education in this study includes two practices. The first refers to a long-term alternative education arrangement, commonly known as “homeschooling.” This practice spans early childhood through secondary education, typically involving children from ages five or six to seventeen or eighteen (Wamsley, 2021; Wang et al., 2019). In this context, children are educated at home instead of attending public or private schools. The second refers to the temporary practice of educating children at home due pandemic-related school closures, often known as “learning at home.” This approach gained significant popularity mainly during the pandemic (Champ, 2021; Hamlin and Peterson, 2022; Wang and Langager, 2023).

As home education and homeschooling are sometimes misused and mixed in the same way, the author attempted to distinguish between home education and homeschooling. When the author refers to the first type of home education, the author uses “homeschooling,” and when the author refers to the second type of home education because of the school closure and the pandemic, the author uses the “pandemic-induced home education.” The author regards this second type of home education as different from homeschooling as some of these parents went back to public schools immediately after the pandemic.

This study seeks to understand Kansan families’ pandemic experiences, including family characteristics, children’s home education experiences, and parental agency experiences, with respect to their children’s pandemic experiences. The research questions are listed as follows:

Q1. What are the characteristics of the home-educated families in this study?

Q2. To what extent do the two groups of home-educated children adapt to their learning environment? What curriculum arrangements, daily schedules, and learning tools are used during the pandemic? What were the learning outcomes?

Q3. What challenges confronted home-learning children during a crisis such as the pandemic? What did the parents do to overcome these challenges?

The central purpose of this qualitative study is to understand the educational and agentic experiences of parents with children who stayed at home during the pandemic. By doing so, the actions of individuals and their perspectives on children’s education can be probed. Multiple sources of data were collected and analyzed in this study. The data for this study came mainly from: (1) online interviews, and (2) archived documents.

Interviews. Five in-depth interviews were conducted in October and November 2021 to examine how children have been learning during the pandemic using questions about parental engagement, children’s academic performance and learning experiences, as well as other parental factors. Among these interviewees, the author sought parents without a limitation of their race and ethnicity, but managed to recruit and complete interviews with Chinese-American parents who lived in Kansas.

Archival Documents. Published information about pandemic research and parental agency literature during the pandemic were reviewed, including peer-reviewed journal articles, official governmental regulations, press releases from credible media, and other online platforms of educational institutions.

The participants were recruited in two steps. First, the author created and posted a recruitment advertisement on WeChat’s local Kansan Chinese group. WeChat is a free mobile application that has over 1.2 billion users as of 2020, according to the data published by a German statistics company, Statista Inc., which helped reach families efficiently. The author shared a message in a local grocery market chat group asking for volunteers to participate in a research project on the topic of Kansan children’s education. More than five families contacted the author in a few days. After screening their current location, families that currently lived in Chicago and families that travelling in Shanghai were not included for the purpose of research focus of this article. Although parents were offered two options to participate, all agreed to complete two parts of the interview. Therefore, interview with each parent last approximately 1.5 hours.

Regarding interview content, there were two parts to the questions: For the first part, the questions were semi-structured. The questions were designed to be open-ended. The objective of this stage was to allow participants to talk and share as freely as possible, and to avoid manipulating interviewees’ perceptions and their responses.

Examples of non-directive open-ended questions included, “can you share the overall academic learning experiences of your children in 2020,” “what excited them,” “what made them upset,” “what about their learning experiences recently,” “can you tell me about the extracurricular activities that your children had engaged in 2020,” “what about family activities during the pandemic,” “are there any challenges to you that came from them studying at home last year, including the challenges to you, and the challenges to them,” “how did you overcome those challenges,” “can you share some example with me,” “is there anything else that particularly unforgettable to you last year,” “is there anything else that you want to share with me,” and so forth.

For the second part, survey items from the Center for Universal Education at Brookings Institution’s Family Engagement in Education Project were adapted for interview questions. Brookings Institution is American research group founded in 1916 on Think Tank Row in Washington, D.C. Between May 2020 and January 2021, a large-scale study led by the Center for Universal Education had been applied to about 25,000 parents across 10 countries on families’ beliefs, motivations, and sources of information regarding their children’s education, and generated extensive results around parents’ purpose of education, pedagogical preferences, indicators of quality education, and so forth. The original survey contains 36 questions. All the survey items were carefully reviewed and modified for cultural and contextual relevance. Questions that did not apply to homeschooling families were not included. Some questions that interviewees expressed as having trouble selecting fixed answers were also captured in author’s research notes.

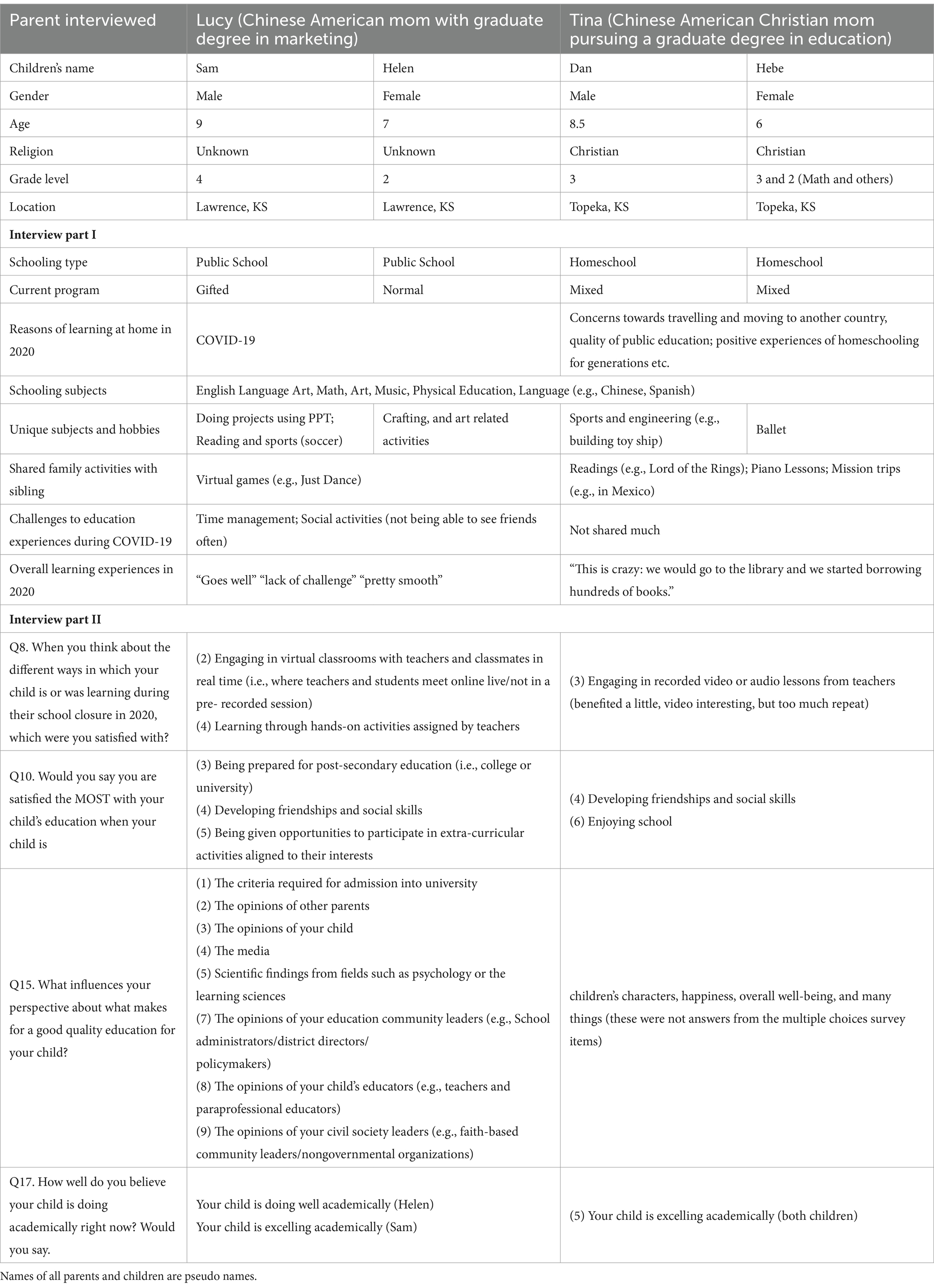

Examples of relevant interview questions included, “Q8. When you think about the different ways in which your child is or was learning during their school closure in 2020, which were you satisfied with” as this can help researcher know the ways classes were arranged during the pandemic, “Q14. How do you react when something about your child’s education bothers or upsets you” as this may help address parental concerns and parental actions, “Q15. What influences your perspective about what makes for a good quality education for your child” as this may help address parental expectation of children’s education, and “Q17. How well do you believe your child is doing academically right now” as this may help understand parental perception of children’s academic performance, and “Q22. At the time of this interview, how happy is your child with their education” as this may help the researcher get a sense of children’s happiness level as an aspect of children’s overall wellbeing, and so on. The answers to these questions aided me in interpreting parental agentic experiences regarding children’s education and lives during the pandemic.

Several Zoom interviews were conducted in the English language. Amazon Gift Card with 15 dollars for each interview was offered to incentivize and value the time of participants. All interviews were conducted with the interviewees’ permission with video recordings, and the written consent form was sent back and stored in the researcher’s confidential and personal computer. The audio data were transcribed according to an online service called Descript. The data analysis involved organizing and preparing the data to gain a general impression. The researcher used carefully stored research notes to code and analyze the scripts. After the coding process, the parental agency literature was revisited and the analysis was refined. This iterative process was repeated several times to ensure that the findings and data were compared.

For the analytical lens of this study, the concept of human agency and the properties of agency framed by Dr. Albert Bandura were applied. In an article entitled Toward a Psychology of Human Agency, Bandura (2006) presented four core properties of human agency: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness. He emphasized individuals’ capability to form intentions of having action plans and strategies (intentionality), setting goals and anticipating outcomes (forethought), making choices and executing actions with self-regulation (self-reactiveness), and making corrective adjustments when necessary (self-reflectiveness) (Bandura, 2006, p.165).

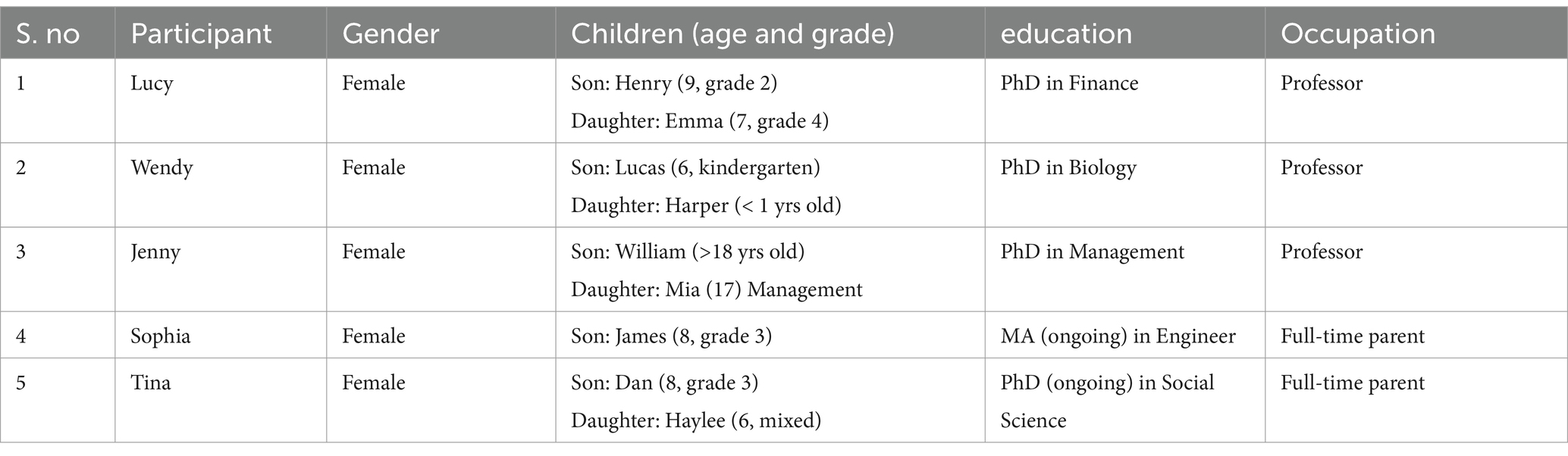

The author managed to recruit five mothers during the pandemic whose families had shared educational experiences, such as staying at home from 2020 to 2021. The basic characteristics of the interviewees are listed in Table 1, which includes information on their parents and children. All names are pseudonyms to protect their confidentiality.

Findings

Among the interviewed families, four lived in Lawrence, Kansas, and one lived in Topeka, Kansas at the time of the interview. All families shared the racial identity of Chinese. All the interviewees were mothers with graduate degrees. These families and children had rich experiences during covid-19 regarding the motivations of home education, children’s wellbeing, and overall home education experiences at the early stage of the pandemic.

For example, the overall happiness level of all families interviewed was relatively high. When interviewees were asked how happy their children were with their education, all shared that they were very happy, and one parent shared that both her children were extremely happy. In the following sub-sections, the author addressed some of the major themes to further understand children’s pandemic and parental agency experiences. Despite the small sample size, the author examined the findings comparatively by their educational arrangements, namely, home education arrangements. Next, the author presents the results and key themes. Selected quotes are presented to illustrate the emergent themes arising from parental voices.

Two different types of home education are introduced earlier for this study: (1) home education could refer to the family practice of educating children at home rather than at a public or private school; (2) home education could refer to the temporary practice of educating children at home due to the pandemic, and it has a similar meaning to learning at home.

As most readers experienced the second type during the pandemic, but not homeschooling, here is more statistics regarding the “homeschooling” practice. With the highest prevalence of homeschooling practices globally, the United States has experienced a steady increase in homeschooled children during the past few decades. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) estimated that in 1999, approximately 850,000 American children were homeschooled, while approximately 1,690,000 (about 3.3%) school-age children were homeschooled in 2016 (Wang et al., 2019).

The legal status and specific practices of homeschooling vary widely across countries and education systems. According to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report launched to describe countries’ laws and policies on inclusion and education, out of the 211 education systems with available data, homeschooling is allowed in 123 of them and exists in 153 of them (Yin, 2022). Notably, even in countries where homeschooling lacks legal recognition, it remains a visible trend, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Present-day homeschooling contains several different formats and arrangements. For example, a family may choose to educate children at home while having the learning supplemented by taking classes with a private tutor, studying in a group (homeschool cooperatives or co-ops), part-time enrollment in a traditional school or an online school, and fully delivering education to children by parents themselves (Cheng and Hamlin, 2023). Among the interviewed families, one parent came from a homeschooling family with three generations of homeschoolers.

“I felt like the weakness of homeschooling families is math”

Children from most interviewed families were enrolled in traditional public schools, while one family opted for homeschooling. Tina, a mother of two homeschooled children, explained that her children had been homeschooled by family members, including herself, even before the pandemic. In contrast, Lucy, another parent with children of similar ages enrolled in public schools, shared her own reasons for home education during the pandemic. Below are quotes illustrating the diverse motivations behind these educational choices.

I do feel like there’s a lot of repeating (for public learning materials provided by the school district) so my kids start getting bored. So for certain lessons as start skipping lessons…we decided not to use it after we are done because it is just a lot of repeating. (Tina)

During the COVID period of time, for a safety reason, we decided to keep them home. Both of them (my children) took online distance learning classes with the elementary school offered by Lawrence public school district. They both stayed home for the entire period of time. (Lucy)

All the interviewed parents, despite not having grown up in the United States, placed a high value on education and had a clear understanding of the subjects being taught. Both Lucy’s children, who attended public school, and Tina’s homeschooled children followed similar curricula during the pandemic, including subjects such as reading, math, art, music, and physical education. Families consistently emphasized the importance of English language and mathematics. Tina, the homeschooling mother, shared her experience of using Singapore math books at home and her deliberate efforts to support her children’s math learning.

I felt like the weakness of homeschooling families is math…cause a lot of parents do not feel confident that they can teach math well, and they do not emphasize on math learning. And so a lot of kids go through homeschooling but they have no confidence in solving math problems. So that’s why early on, we emphasize on math a lot. And so they spend at least 20 min or half an hour a day on math. (Tina)

This aligns with findings from research communities. Homeschool literature indicates that homeschoolers tend to perform better on reading assessments but comparatively worse in mathematics than their traditionally schooled peers. For instance, a study using ACT math scores as an outcome measure identified a mathematical disadvantage for homeschoolers (Qaqish, 2007). The narratives presented here offer additional evidence to inform public debates on different schooling types, while also serving as a caution for families considering homeschooling, highlighting potential challenges their children may face in mathematics.

Tina’s homeschooling approach allowed her children to explore personalized subjects that were less commonly offered to their peers in public schools. For instance, her son studied programming, while her daughter developed an interest in learning foreign languages like Spanish. Tina felt fortunate to have the support of her mother-in-law, Lily, who had successfully homeschooled five sons and now lived with them. Tina’s husband, an engineer, also fully supported their decision to homeschool, confident in its benefits for their children. Below are a few examples of each child’s strengths and why Tina believed these subjects were important.

I do see the advantage, like my son, he started to building some programming, that kids who does not have backgrounds would not necessarily know how to program video games or do stuff with like writing codes. He is not actually writing, but he has an easy program that helps him write codes to program. My daughter is very gifted in language and she just takes on all language learning. I just feel like, by homeschooling them, they can get more personalized learning and teaching. (Tina)

Tina’s approach to her children’s education exemplifies all aspects of human agency as described by Bandura (2006), which emphasized individuals’ capability to form intentions of having action plans and strategies (intentionality property, evidenced by Tina’s educational choices before the pandemic and her intentionally arranging children’s education, selecting certain learning materials and daily schedules for them; and Tina’s being intentional about each schooling type’s weakness and intentionally making responding choices), setting goals and anticipating outcomes (forethought property, evidenced by Tina’s being aware that homeschoolers’ potential disadvantage in math learning, her decision to use Singapore math for her children to embrace more challenges), making choices and executing actions with self-regulation (self-reactiveness property, seen from Tina’s homeschooling choices and Tina’s having her family members taking responsibility to homeschool the two children whenever needed), and making corrective adjustments when necessary (self-reflectiveness property, seen as Tina changing the learning materials after getting to know the public materials suggested by her local school district, and after getting feedback from her son, who had felt that the materials were too easy for him).

The relatively strong agentic experience of Tina was also evidenced by Tina’s different arrangements of two children of her: her son Dan being advanced in learning math related materials to his age, and her daughter Hebe being advanced in learning English language art, compared with their age groups. Hebe learned the language with her elder brother despite that she was about 2 years younger. The interviewed families with children enrolled in public schools usually followed what teachers asked them to arrange, and the materials for different age groups, Tina’s agency, were vividly shown in this process of her personalized choices of education arrangements and learning materials for her children.

“The challenges of learning at home is the lack of challenges”

Some agentic experience was also witnessed in Lucy’s family with talented children. Lucy has a nine-year-old boy and a seven-year-old girl. Her son was enrolled in a gifted program while her daughter was enrolled in regular program at the same local school. Her son passed the test that their local school district used to assess gifted children at the beginning of the school year. The education arrangement, therefore, became relatively smooth as school teachers took the lead, and that Lucy’s role during the pandemic had more to do with “time management,” namely, to provide reminders for her children of their schedule, to print stuff for them, and to assist with other things children’s teachers asked them to do.

My son is enrolled in the gifted program. That program kept going without mixing kids up across the entire period. So he got to do more projects individually with a gifted teacher. So he did not get too bothered by the regular classroom activity…I think everything goes on pretty well, except just the learning part is a little bit of lacking of challenge…I guess I’m lucky, they do not need any help. They manage their stuff very well. The only thing we have to spend time is just to print them the schedule and sometimes remind them of the schedule. So they do not forget about which time to go to which class. (Lucy)

Like Lucy, other interviewed parents of children enrolled in public schools preferred public schooling. For example, all parents shared that they were most satisfied when their children could develop friendships and social skills at school. One of the major concerns of homeschooling community centers is the social and emotional wellbeing of children who study at home. Children’s socialization has been a topic of considerable interest and concern among scholars, the public, and policymakers (Kunzman and Gaither, 2020; Medlin, 2000). However, homeschooled families do not see this problematic and that they have taken action to help children socialize. According to Tina, her children took classes with each other and with other families who had homeschooled their children. Homeschooled families sought help from homeschooling organizations for socializing, as shared by Tina.

We have different homeschooling organizations. The ones we attend is just for socializing. They (my children) just play and then they have subjects but mainly for practice being a classroom with other kids. It’s only 2 hours once a week. When the kids grow older, there is another homeschooling organization called Cornerstone. It’s more for middle school, high school students, and those are more supervised. I heard from my friends that they want you to submit a weekly plan, what you are gonna teach your kids every week. Through those organizations, once kids get into high school, they could take college courses for free. A lot of parents send their kids there to go through college quicker. They can take college courses that they need to. It depends what you need. It’s very free in Kansas, whatever you want. (Tina)

Regarding children’s academic performance during the pandemic, there was a mixed picture. Tina, the homeschooling mother, perceived that both of her children were excelling academically. Other mothers with children enrolled in public schools perceived their children to have done less well academically during the pandemic. The condition of children’s academic performance was also not fixed during the pandemic period, adding to the complexity of the evaluation.

For example, a parent with a 17-year-old daughter mentioned that the daughter sometimes struggled and did not struggle at other times. These examples provided information on why and how children learned at home during the pandemic. The interview data were organized in a few forms to provide the overall learning experiences described by the parents of 10 children in Kansas. Here is a form that compared Lucy and Tina, as their profiles shared the most similarity in terms of the ages of their children and the perception of their talented sons (Table 2).

Parental agency in adverse situations

In contemporary terms, an agent is “a being with the capacity to act,” and agency denotes “the exercise or manifestation of this capacity (Schlosser, 2019).” Individual agency has been understood as a multidimensional construct involving engagement with the past, present, and future, comprising the capacity and intention to set goals (Bandura, 2006; Schlosser, 2019), freedom to enjoy what they value (Alkire, 2008; Sen, 1985), autonomy in relationships and actions (Alkire, 2008; Szabat, 2023), expectations and strategies for success (Griffiths et al., 2004; Schoon et al., 2021), and so forth. In other words, past experiences, reflections on one’s capabilities given constraints and opportunities, and expectations towards the future could inform the manifestation of agency.

Parents’ agency was reflected not only in the previous examples of Tina and Lucy leading or assisting their children in arranging their curriculum and their schedule intentionally, but also in parents’ beliefs, attitudes, and ways of parenting during a crisis. Although the purpose of this study was not to measure agency or judge who had more agency, There are some unique agentic experiences from the interviewees, manifested in different examples of parents taking responsibility for children’s education, and how they found ways to address children’s concerns and to perceive pandemic experiences.

Among the interviewees, Jenny was a highly educated parent, as she owned a doctoral degree and served as a professor at a local university. Her daughter, Mia, is a child who needs special care. Mia was attending local public school’s inclusive program, with most classmates who did not need special care. Jenny shared their experiences during the pandemic, showing her empathy as a teacher and as a parent.

That was a very hard time for Mia’s teachers. Because for special needs, sometimes if you teach them like solving a math problem, you have to write and draw on a piece of paper in front of them. And at the beginning of 2020, maybe after March of 2020, when the classes are online, a lot of teachers do not know how to use the technology and they struggle a lot to explain details online through the students…In the past we outsourced education to school, but with the pandemic, we have to be with Mia every day and help her to learn each subject and help her to keep active physically. (Jenny)

Being aware of the shared challenges regarding physical exercise and socialization due to the pandemic, Jenny shared more about her experience of a parent helping Mia. For example, Jenny and her husband created many travel opportunities for Mia: they went to the national parks when school was closed, and they had road trips to Colorado, Michigan, and quite a few places during the pandemic.

The challenging part for Mia is just the lacking of real social interaction with her friends and teachers. She is a very social person. So I think she made that up by just greeting everyone on Zoom and seeing their faces. Since she stayed at home and we stay at home every day, so our family get closer. I think the relationship among family members also help. (Jenny)

When Jenny shared her family had a closer relationship as they traveled together and read the bible together, the researcher asked Jenny to share more about their beliefs and perceptions of the pandemic. Jenny then started to share more stories about her daughter Mia, and why they could keep a positive mood during the pandemic.

Mia became a believer around age 10. She was baptized at age 12, and we read the Bible together and we pray together and we just keep ourselves focused on God and knowing everything including the pandemic is for good purpose. And there are a lot of things to be thankful for, even during the pandemic. So that helped us to have a very positive perspective every day. (Jenny)

The author was able to learn and capture insights and strategies from other parents in adverse situations and their ways of communicating with their children to help them learn, and attempted to be fair in presentation of the data using parents’ voices. The author did not ask them to share their religious belief. Therefore, some of the interviewees did not disclose them. Wendy, mother of a six-year-old boy, Lucas, and a newborn baby younger than 1 year old, shared her strategies when her son Lucas had trouble following his teacher and cried when taking a class.

Sometimes he (Lucas) could get really frustrated. I think it important for the parents to be really patient because it was hard for you, but it was also hard for them. I guess, parents really need to be really patient. And at the time of their frustration, do not try to reason with them just to try to show your emotions to them. Just say, ‘I’m really sorry. You know, you did not catch up with your teacher. You must feel really frustrated, but that’s okay. Mama is here. Mama will help you. Do not cry.’ Just show your emotion first. And then when he calms down, you can start reasoning with him and say, “hey, if your teacher already go to the next word, but you were still writing the previous one, you’d better quit what you were writing and try to follow your teacher. It’s important to follow your teacher’s pace. Your teacher cannot follow every one of the kid in the class. When he feels frustrated, you just show empathy, show your emotions to them first, and then when they calm down, you have to reason with them and to tell them what’s the right thing to do. (Wendy)

Some parents stated that the pandemic made their life more difficult but they took different ways to help their children. As a mother of two boys, it was “hard to do some PE, it’s hard” for Sophia’s sons to take some of his favorite classes. Sophia originally had some thoughts in mind to help with the PE class but failed. When asked if her family took children to play outside, Sophia also shared that was not the case at the very beginning of the pandemic as they did not want to meet people for fear of the virus.

At that time, I was thinking we can buy some ropes so they can jump at a home. I asked my older son. He did not show any interest on the ropes. So, okay, I gave up. Sometimes he just ran at the home, jump on the sofa and the bed. That’s all. So that’s the (pandemic) influence…At the very beginning, we hardly to go outside at that time, we seldom went outside because we did not want to meet people. We went to parks during the weekend. But during the weekdays, most of the time we were at home. (Sophia)

As a child who loved PE class the most before the pandemic, Sophia’s elder son quickly shared with Sophia that he felt bored. The author asked Sophia if classes being closed upset her sons, Sophia said yes, and then she shared how she helped her children get engaged and learn.

Yes, sometimes he just told me he felt a little boring (bored). We try to avoid this, because we bought a lot of toys for them, for both of them. If they want to play Lego, we buy Lego. If they want other toys…My older boy loves playing Lego. He can play Lego for hours. If we bought new Lego, it will keep him busy for a long time, so that’s a good thing. Another thing is very important. I also borrowed hundreds of books from library…for the full whole year. I bought many books from the library, so sometimes I just borrow…not bought, borrow, I am sorry. I borrow like 40, 50 books from the library for a couple of months. And then after read all the books, I return them, and borrow some books again. So we borrow a lot of books from library. So this, this was very helpful, the books. (Sophia)

Sophia’s experience echoed Tina’s experiences. Although their children had different schooling arrangements, they both valued the importance of children’s reading and learning. Even though Sophia thought the pandemic brought about challenges, she mentioned the positive side of the pandemic regarding her children’s language learning. After about 1 year of school closure, her son’s school later reopened, and things went back to normal for Sophia’s family. When asked if there was anything else she wanted to share with me, Sophia said more about her children’s language learning experiences as a bilingual parent.

Because we were all at home for over 1 year, so I teach Chinese every day for them. This is a good chance for them to learn Chinese. But now they are both in school now. We do not have time to learn Chinese every day, you know. Maybe just a once a week or a couple of times a week for Chinese. (Sophia)

Discussion: understand parental agency

The interviewed Chinese parents’ experience during the pandemic showed relatively strong parental agency in children’s education and life, manifested by the way parents selected the educational programs and curriculum for their children, kept their children engaged in their classes, supported their children’s physical exercises and social needs, responded to children’s emotional needs and learning needs, taught children foreign languages, directed children to books and reading materials, among other examples.

As demonstrated in parental agency literature, there have also been some major common themes that parental agency literature shares. On the one hand, parental agency has been argued to play a critical role in children’s education. The concept of agency was analyzed in the context of children’s education process, such as in education mobility, educational collaboration, and learning process (Darragh and Franke, 2022; Hartas, 2008; Koskela, 2021; Morris, 2004; Schnee and Bose, 2010; Schoon et al., 2021).

For promoting education outcomes, the parental agency is argued to play a critical role in children’s overall academic success (Morris, 2004; Rall, 2021b), reflected in parental strategies for helping children learn mathematics (Schnee and Bose, 2010) and in enhancing children’s language studies at home (Hartas, 2008), and so forth. The parental agency could also influence the education process, as seen in the relationships between families and schools within their education system and the potential to foster successful collaboration between parents and schools (Koponen et al., 2013; Rautamies et al., 2019), aiding families in making critical schooling decisions (Dennison et al., 2020; Koskela, 2021; Mcclain, 2010), helping children’s upward transition of education levels (Dunlop, 2003) and having predictive power on children’s education mobility (Schoon et al., 2021).

On the other hand, the parental agency impacts several aspects of children’s wellbeing and life. The parental agency serves an important role in making decisions for their children, especially in difficult life moments. For example, researchers have investigated the experiences of parents with children in need of pediatric palliative care (Szabat, 2023), parents of children with Down Syndrome for early interventions (Rix and Paige-Smith, 2008), parents of children with special health care needs in South Israel (Peres et al., 2014), parents with children under outpatient community mental health treatment (Erickson, 2022), parents with children in dyslexia (Griffiths et al., 2004), among a few other studies. Parental agency was also reflected in parents with key decision-making in terms of children’s behavior, such as with those with children having suicidal behavior (Juel et al., 2023), parents of children with delinquent behaviors (Hagan et al., 2002), parents of students that suffered from bullying (Hein, 2017), and so forth.

The author investigated how parental agency was reflected in family experiences during the pandemic, focusing on four core properties of human agency: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness based on Bandura’s work and interpretation of the core properties (Bandura, 2006). The changes in Chinese American households regarding how parents perceived their children’s learning and life at home were explored.

In adverse situations like the pandemic, some parents with children may find building personal confidence, strengthening parenting ability, and taking the initiative to make positive changes even more difficult. However, the families interviewed in this study seem not to be negatively influenced by the pandemic. This may have to do with the strong parental agency that supports children’s learning and life.

Although this qualitative study could not prove a causal link between parental factors with children’s learning outcomes and process, it added additional vivid evidence to the literature to understand the context and concept of parental agency, using parental voices, and the unique pandemic setting. The qualitative study added a piece of what parental agency may help in adverse situations. Although how families confronted the challenges differs by the specific context and situation faced, some parents of essential characteristics showed higher and stronger parental agency than others, which have helped them support the wellbeing and education of their children during a crisis like the pandemic. The interviewees with advanced degrees, certain beliefs and attitudes towards adverse situations in life, access to certain resources, and other family characteristics, may be among the factors that allowed the interviewed parents’ capability to do this and to help their children. The author hoped future studies could provide more insights into what families faced during difficult times and what practical strategies could help them develop parental agency and help their families confront challenges during a crisis.

As for the limitations of this study, these five families with relatively highly educated mothers may not represent all Chinese families in the United States, and the findings may not be enough to get generalizable insights. Insights from mothers not fathers may also limit the representation of the findings. To achieve more, and to find out the actions and strategies parents engaged to facilitate changes in their children’s education and life during crisis, more variation of sample and larger sample sizes will be needed. For additional meaningful research designs and to factors related to parental agency, such as what hindered parental agency exercises during the pandemic, and what helped parents support their children’s education and wellbeing in constrained circumstances, both quantitative and qualitative research are needed in the future.

There are a few practical implications of this study to inform education policy, guide service providers, and support home-based learners. First, the current and prospective homeschooling families, especially families navigating unfamiliar educational systems, this study hopes to offer practical strategies, resource insights, and solutions for overcoming common challenges. Learning from similar families’ experiences may enhance their children’s social and academic development. Second, understanding why some Chinese families choose homeschooling over public education will help educators, school districts, and policymakers create more inclusive policies. Third, for educational service providers—such as consultants, curriculum developers, and mental health professionals—this study hopes to help them gain understanding of Chinese parents who live in the United States. Tailoring services to these families can improve children’s education and wellbeing.

Data availability statement

More takeaways from this project are available upon request, subject to review for ethical considerations by the author. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will not be publicly shared to protect participant identities.

Ethics statement

This study is supervised by the University of Kansas, under IRB ID of STUDY00147738, which has been effective since October 25, 2021. All families interviewed had shared written consent by email to get interviewed and for data analysis. All the names from interviews here are pseudonyms without identifiable information.

Author contributions

DY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by a Summer Research Scholarship from the University of Kansas.

Acknowledgments

The author drafted the paper in 2021 and 2022, before ChatGPT got introduced. The author used the free version of ChatGPT in 2024 mainly for grammar editing and would like to give credit to it. ChatGPT says: “no robots were harmed or overworked in the making of this paper” when I asked it to make the acknowledgment in a fun way.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 30, 109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

Alkire, S. (2008). Concepts and measures of agency. OPHI Working Paper Series. Available at: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:cdecbaca-447c-43b7-8e3f-851517b5ff97

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., and Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers Teach. 21, 624–640. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Brown, K., and Westaway, E. (2011). Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 36, 321–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-052610-092905

Champ, M. (2021). Homeschool registrations rising in Australia, alternative education advocates say mainstream schools need a shake-up. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-08/home-and-alternative-schooling-on-the-rise-in-australia/100503948 (Accessed October 8, 2021).

Cheng, A., and Hamlin, D. (2023). Contemporary homeschooling arrangements: An analysis of three waves of nationally representative data. Educ. Policy 37, 1444–1466.

Curdt-Christiansen, X. L., and Wang, W. (2018). Parents as agents of multilingual education: Family language planning in China. Lang. Cult. Curric. 31, 235–254.

Darragh, L., and Franke, N. (2022). Lessons from lockdown: parent perspectives on home-learning mathematics during COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 20, 1521–1542. doi: 10.1007/s10763-021-10222-w

Dennison, A., Lasser, J., Awtry Madres, D., and Lerma, Y. (2020). Understanding families who choose to homeschool: agency in context. School Psychology 35, 20–27. doi: 10.1037/spq0000341

Dunlop, A.-W. (2003). Bridging children’s early education transitions through parental agency and inclusion. Educ. North 11, 55–65.

Eggleston, C., and Fields, J. (2021). Census Bureau’s household pulse survey shows significant increase in homeschooling rates in fall 2020. Suitland, MD: United States Census Bureau.

Erickson, E. G. (2022). Parental “sense of agency”: A qualitative study of parents experiences assisting their children in outpatient community mental health treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Erickson, P. (2020). 11. Kansans can: redesign professional learning and re-licensure. Educ. Considerations 46:2235. doi: 10.4148/0146-9282.2235

Fernández, E. (2016). Illuminating agency: A Latin@ immigrant parent\u0027s testimonio on the intersection of immigration reform and schools. Equity Excell. Educ. 49, 350–362.

Gniewosz, G. (2022). A mother’s perspective: perceived stress and parental self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 20, 666–693. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2022.2120464

Griffiths, C. B., Norwich, B., and Burden, B. (2004). Parental agency, identity and knowledge: mothers of children with dyslexia. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 30, 417–433. doi: 10.1080/0305498042000260511

Guo, Y. (2021). Towards social justice and equity in English as an Additional Language (EAL) policies: The agency of immigrant parents in language policy advocacy in Alberta schools. Int. Rev. Educ. 67, 811–832.

Hagan, J., McCarthy, B., and Foster, H. (2002). A gendered theory of delinquency and despair in the life course. Acta Sociol. 45, 37–46. doi: 10.1080/00016990252885780

Hamlin, D., and Peterson, P. E. (2022). Homeschooling skyrocketed during the pvandemic, but what does the future hold? Educ. Next 22, 18–24.

Hartas, D. (2008). Practices of parental participation: a case study. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 24, 139–153. doi: 10.1080/02667360802019206

Hein, N. (2017). New perspectives on the positioning of parents in children’s bullying at school. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 38, 1125–1138. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2016.1251305

Hoskins, K., Thu, T., Xu, Y., Gao, J., and Zhai, J. (2023). Me, my child and Covid-19: parents’ reflections on their child’s experiences of lockdown in UK and China. Br. Educ. Res. J. 49, 455–475. doi: 10.1002/berj.3850

Juel, A., Erlangsen, A., Berring, L. L., Larsen, E. R., and Buus, N. (2023). Re-constructing parental identity after parents face their offspring’s suicidal behaviour: an interview study. Soc. Sci. Med. 321:115771. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115771

Koponen, K., Laaksonen, K., Vehkakoski, T., and Vehmas, S. (2013). Parental and professional agency in terminations for fetal anomalies: analysis of Finnish women’s accounts. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 15, 33–44. doi: 10.1080/15017419.2012.660704

Koskela, T. (2021). Promoting well-being of children at school: parental Agency in the Context of negotiating for support. Front. Educ. 6:652355. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.652355

Kulis, S. S., Ayers, S. L., Harthun, M. L., and Jager, J. (2016). Parenting in 2 worlds: Effects of a culturally adapted intervention for urban American Indians on parenting skills and family functioning. Prev. Sci. 17, 721–731.

Kunzman, R., and Gaither, M. (2020). Homeschooling: An updated comprehensive survey of the research. Other Education-the journal of educational alternatives, 9, 253–336.

Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., Chang, O. D., and Downing, K. M. (2021). Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 122:105585. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105585

Mcclain, M. (2010). Parental agency in educational decision making: a Mexican American example. Teach. College Rec. Voice Scholarship Educ. 112, 3074–3101. doi: 10.1177/016146811011201203

Medlin, R. G. (2000). Home schooling and the question of socialization. Peabody J. Educ. 75, 107–123.

Miller, M. (2020). 5. Leadership during change. Educ. Consider. 46:2245. doi: 10.4148/0146-9282.2245

Morris, J. E. (2004). Can anything good come from Nazareth? Race, class, and African American schooling and Community in the Urban South and Midwest. Am. Educ. Res. J. 41, 69–112. doi: 10.3102/00028312041001069

Moustaoui Srhir, A. (2020). Making children multilingual: Language policy and parental agency in transnational and multilingual Moroccan families in Spain. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 108–120.

Musaddiq, T., Stange, K., Bacher-Hicks, A., and Goodman, J. (2022). The Pandemic’s effect on demand for public schools, homeschooling, and private schools. J. Public Econ. 212:104710. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2022.104710

Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., et al. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a National Survey. Pediatrics 146:e2020016824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824

Peres, H., Glazer, Y., Landau, D., Marks, K., Abokaf, H., Belmaker, I., et al. (2014). Understanding utilization of outpatient clinics for children with special health care needs in southern Israel. Matern. Child Health J. 18, 1831–1845. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1427-2

Qaqish, B. (2007). An analysis of homeschooled and non-homeschooled students’ performance on an ACT mathematics achievement test. Home School Res. 17, 1–12.

Rall, R. M. (2021). Why we gather: educational empowerment and academic success through collective black parental agency. J. Family Div. Educ. 4, 64–90. doi: 10.53956/jfde.2021.153

Rautamies, E., Vähäsantanen, K., Poikonen, P.-L., and Laakso, M.-L. (2019). Parental agency and related emotions in the educational partnership. Early Child Dev. Care 189, 896–908. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1349763

Rix, J., and Paige-Smith, A. (2008). A different head? Parental agency and early intervention. Disab. Soc. 23, 211–221. doi: 10.1080/09687590801953952

Schlosser, M. (2019). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/agency.

Schnee, E., and Bose, E. (2010). Parents" don't" do nothing: reconceptualizing parental null actions as agency. School Commun. J. 20, 91–114.

Schoon, I., Burger, K., and Cook, R. (2021). Making it against the odds: how individual and parental co-agency predict educational mobility. J. Adolesc. 89, 74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.04.004

Sen, A. (1985). Well-being, agency and freedom: the Dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos. 82, 169–221. doi: 10.2307/2026184

Szabat, M. (2023). Parental agency in pediatric palliative care. Nurs. Inq. 31:e12594. doi: 10.1111/nin.12594

Trotta, E., Serio, G., Monacis, L., Carlucci, L., Marinelli, C. V., Petito, A., et al. (2024). The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Italian primary school children’s learning: a systematic review through a psycho-social lens. PLoS One 19:e0303991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0303991

Vidyarthi, A., Vijayaraghavan, J., Livesey, A., Bibi, A., Armstrong, C., Haj-Ahmad, J., et al. (2021). Agency and resilience—foundational elements of adolescent well- being. Geneva: PMNCH for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health.

Vincent, C. (2001). Social class and parental agency. J. Educ. Policy 16, 347–364. doi: 10.1080/0268093011-54344

Wamsley, L. (2021). Homeschooling doubled during the pandemic, U.S. Census survey finds. NPR News. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2021/03/22/980149971/homeschooling-doubled-during-the-pandemic-u-s-census-survey-finds (Accessed March 22, 2021).

Wang, K., Rathbun, A., and Musu, L. (2019). School choice in the United States: 2019 (NCES 2019-106). Washington, DC: ERIC.

Wang, Q., and Langager, M. (2023). Curricular flexibility: a comparative case study of homeschooling curriculum adjusting in the USA and China. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 25, 40–53. doi: 10.1108/IJCED-06-2022-0047

Yin, D. (2022). The importance and relevance of home education: global trends and insights from the United States. UNESCO GEM Report. Available at: https://gem-report-2021.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Yin.pdf (Accessed May 25, 2021).

Keywords: pandemic (COVID19), challenges, home education, homeschooling, K-12, Chinese American families, parental agency, online interviews

Citation: Yin D (2025) Navigating uncertainty: parental agency in Kansan Chinese families’ education at home during the pandemic. Front. Educ. 9:1499193. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1499193

Edited by:

Simona De Stasio, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyReviewed by:

Benedetta Ragni, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyFrancesco Sulla, University of Foggia, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Yin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Danqing Yin, ZGFucWluZy55aW5Aa3UuZWR1; ZGFudHkueWluQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Danqing Yin

Danqing Yin