- 1Instituto Superior de Gestão – Business and Economics School, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2CIGEST – Centro de Investigação em Gestão, Lisbon, Portugal

- 3CEFAGE – Centro de Estudos Avançados em Gestão e Economia, Évora, Portugal

Introduction: This research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the SER project, which focuses on autonomy and curricular flexibility. Additionally, it seeks to assess the profiles of students from three Portuguese professional schools in relation to their social and emotional skills, self-concept and personal development after project implementation.

Methods: The sample comprised of 381 students aged between 15 and 20 years. The study employed a quantitative methodology with data collected using the Social and Emotional Skills Questionnaire, the Self-Concept Scale, and the Positive Youth Development Scale.

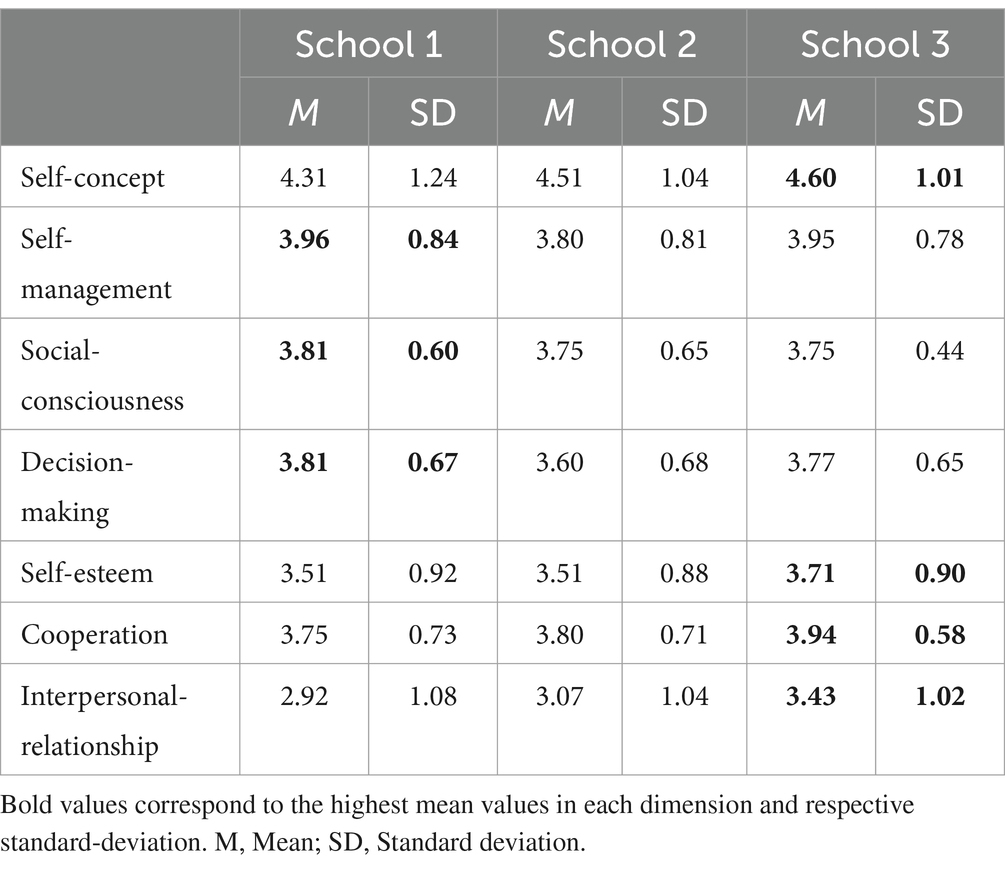

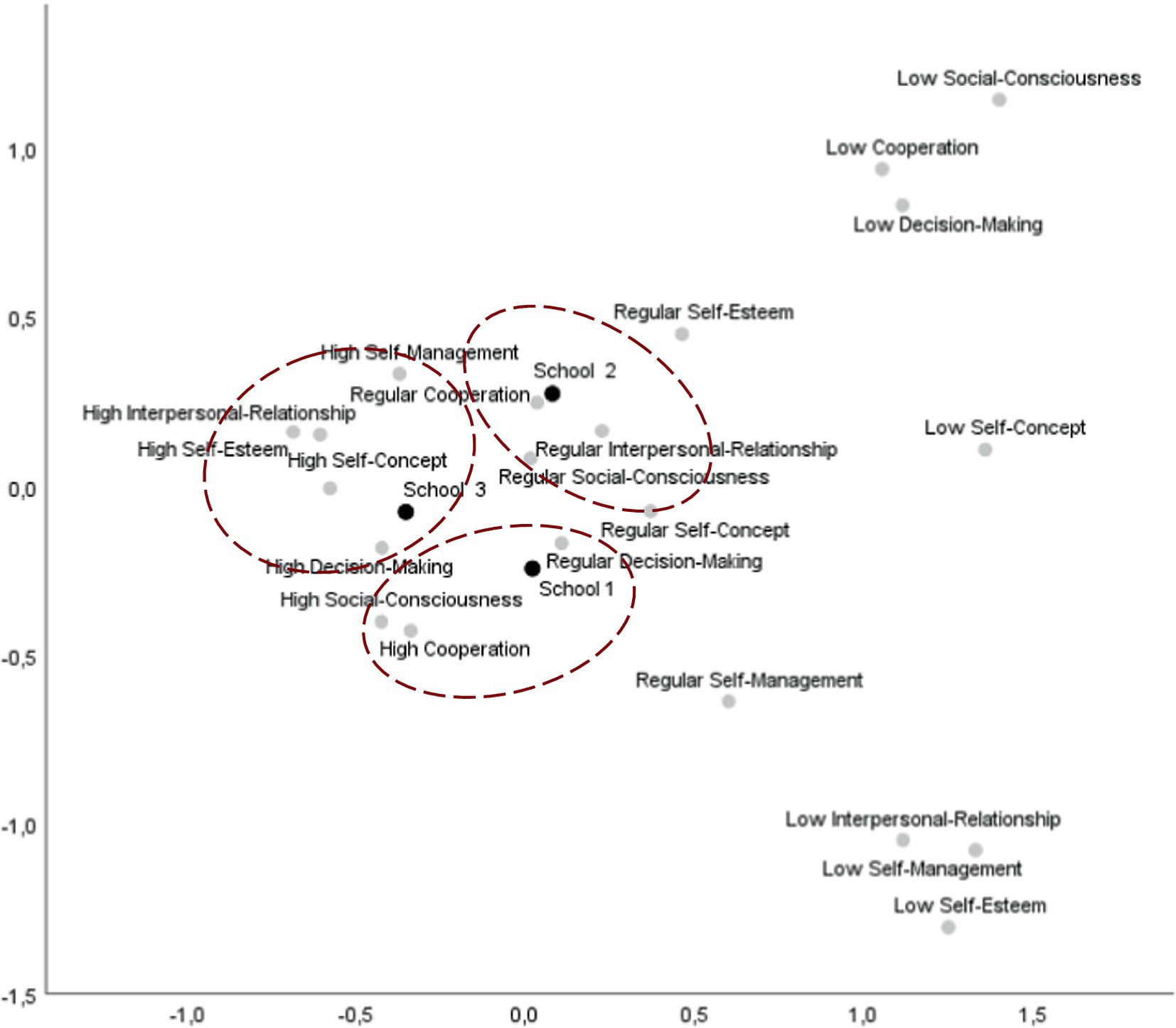

Results: School 1 includes students who tend to exhibit high levels of Social Awareness and Cooperation. School 2, while not excelling in any particular competencies, shows above-average values across all assessed dimensions. Finally, students at School 3 demonstrate elevated levels in Interpersonal Relationships, Self-Esteem, Self-Management, Self-Concept, and Decision-Making.

Discussion: It was found that student profiles differ depending on the school they attend, and it was found that statistically significant differences occur between School 1 and School 2 in Decision-Making and between School 1 and School 3 in Interpersonal Relationships.

1 Introduction

Social and emotional skills, along with self-concept, play a crucial role in the positive development of youth (Jaureguizar et al., 2018). In an increasingly complex society, the ability to understand and manage one’s own emotions, interact effectively with others, and maintain a healthy self-image has become essential for personal and social success (Casino-García et al., 2021). These skills not only contribute to the emotional well-being of young people but also directly influence their interpersonal relationships, academic performance, and ability to face challenges (Arslan, 2021). Positive youth development is intrinsically linked to a set of social and emotional competencies that serve as pillars for the formation of resilient, self-confident individuals capable of navigating the transition from adolescence to adulthood (Wikman et al., 2022).

This exploratory study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the SER Project, an innovative initiative in the field of vocational education in Portugal, focusing on autonomy and curricular flexibility as tools to promote the integral development of students. Thus, this research proposes a detailed analysis of the competency profiles of students from three Portuguese vocational schools involved in the SER Project, highlighting the skills acquired during the program and those that need improvement. The study intends to map the competencies developed while also offering insights into the relationship between social and emotional skills, self-concept, and positive youth development, emphasizing the importance of educational policies and interventions aimed at strengthening these competencies in young people.

2 Study context

In Portugal, vocational schools are a fundamental part of the educational system and provide an alternative to traditional secondary education. These schools emerged in the 1980s in response to the growing need for professional qualifications and the high dropout rates. Today, they are a solid and recognized option within the Portuguese educational system. These schools focus on technical and vocational training, preparing students for the labor market in specific areas (Crato, 2020).

The target audience for vocational schools consists of young individuals who have completed the 9th grade and choose to pursue a training path that combines theoretical education with a strong practical component. Each course culminates in the awarding of a Level IV diploma from the National Qualifications Framework, which is recognized throughout the European Union (Priestley et al., 2021).

One of the major advantages of vocational schools is their strong connection to the labor market, often established through partnerships with local companies and institutions (Ramadhani and Rahayu, 2020). These partnerships allow students to undertake curricular internships, facilitating their integration into the workforce upon course completion. These schools contribute to reducing dropout rates and offer an alternative pathway for continuing studies in higher education (Akbulaev et al., 2021).

The three schools1 analyzed in this study belong to the same private educational group that, over the past decade, has taken decisive steps toward educational innovation and transformation. One of the changes that consolidated this progress is related to the development and implementation of project-based work within the framework of the autonomy and curricular flexibility program promoted by the Portuguese government. The program aims to initiate initiatives that impact students’ development, contributing to their formation as conscious, creative, committed, collaborative, and communicative individuals. Therefore, this study sought to determine whether the implementation of this project effectively aligned students’ profiles with the profiles of the schools they attend. This assessment constitutes a first step in measuring the impact of the transformation in the three schools and in building an evaluation model that supports their improvement and helps to visualize future strategies.

2.1 Profile of School 1

This school adopts an educational approach aimed at developing autonomous, reflective, creative, communicative, and cooperative individuals. The school environment is designed to encourage active learning, innovation, and continuous personal development. The underlying belief is that each student can be the protagonist of their own life, making informed decisions and contributing meaningfully to society. School 1 offers a learning environment that goes beyond mere knowledge transmission, focusing instead on the development of key competencies that empower students to become active, responsible, and innovative citizens.

2.2 Profile of School 2

School 2 promotes an educational environment that emphasizes the holistic development of students, encompassing not only cognitive but also social and emotional aspects. Its goal is to prepare students to face challenges, fostering a proactive, collaborative, and creative mindset. This school stands out for preparing students for the labor market and for shaping conscientious citizens committed to sustainable development and social well-being. Students attending this school are creative, flexible, organized, and collaborative. Upon completing their courses, they are ready to face and overcome the challenges that may arise in their personal and professional lives.

2.3 Profile of School 3

School 3 focuses on the holistic development of its students, emphasizing social, cognitive, and professional skills. It values students’ ability to respond to personal and professional challenges. The school promotes a culture of collaboration, where the integration of all opinions is essential for team success. Its primary goal is to develop committed, creative, flexible, collaborative, conscientious, and competent individuals who can positively contribute to society. Students who choose courses offered by this school are typically attracted to dynamic and varied work environments characterized by constant challenges and opportunities.

It is important to note that the literature review is based on the competencies corresponding to the profiles of the three schools under study.

3 Literature review

3.1 Relationship between social and emotional skills, self-concept, and positive youth development

Social and emotional skills, self-concept, and positive youth development are intrinsically linked and significantly influence one another during the growth process of young individuals (Jaureguizar et al., 2018). Social and emotional skills involve the ability to recognize and manage one’s emotions, establish and maintain healthy relationships, make responsible decisions, and cope constructively with challenges (Murano et al., 2021). The development of these skills contributes to the formation of a positive self-concept, encouraging young people to have a clearer and more confident perception of themselves (Zhang et al., 2020). Additionally, Melendro et al. (2020) note that well-developed social and emotional aspects promote psychological well-being, help young people face the challenges of adolescence, and build a healthy identity, which is essential for their positive development.

Following this idea, Alsaker and Kroger (2020) state that there is a significant relationship between social and emotional skills and self-concept, which refers to an individual’s perception of themselves, including self-esteem, self-image, and self-worth. According to Sagone et al. (2020), young people can only manage their emotions and relate well to others if they have a favorable view of themselves. A strong and positive self-concept is fundamental to the healthy development of young people, as it influences how they see themselves and interact with the world (Rogers et al., 2020). As mentioned earlier, self-esteem plays a critical role in the positive development of young people, as it is one of the main pillars for forming a healthy and balanced identity (Alsaker and Kroger, 2020). The perception young people have of themselves directly influences their confidence, decisions, and how they relate to the world around them (Moneva and Tribunalo, 2020).

Positive self-esteem enables young people to feel capable and valued, fostering an optimistic view of their abilities. This is essential for increasing resilience, which is the capacity to face challenges and adversities constructively (Orth et al., 2019). Young people with high self-esteem are more likely to take calculated risks, explore new opportunities, and persist in the face of adversity because they believe in their abilities and have well-defined goals (Luthar et al., 2019). Moreover, self-esteem is closely linked to emotional and mental well-being, and when young people feel good about themselves, they tend to experience less anxiety, depression, and stress (Steiger et al., 2019).

Self-esteem also significantly impacts the school context, as young people who believe in their capabilities feel more motivated, participative, and engaged in educational activities (Miller et al., 2020). Feeling more prepared to face academic challenges, they generally perform better academically and tend to feel more satisfied with the learning process (Tus, 2020). Conversely, low self-esteem increases insecurity, isolation, and emotional difficulties, which can compromise the social and cognitive development of young people (Orth et al., 2019). These feelings of inadequacy can lead to school dropout and risky behaviors, negatively affecting their life trajectories. Students with strong self-esteem tend to become confident, resilient, and socially competent adults, ready to face life’s challenges and contribute positively to society (Steiger et al., 2019).

During adolescence, self-image can undergo substantial transformations as physical appearance, emotions, and behaviors change constantly, influencing how young people are perceived by others (Monell et al., 2022). Self-image is a central component of self-esteem, so the higher it is, the more likely young people are to feel good about themselves. Conversely, a negative self-image can lead to feelings of insecurity, low self-esteem, and devaluation (Sánchez-Rojas et al., 2022). Based on this premise, Orth and Robins (2022) argue that when young people recognize their value, they build a more robust and resilient self-esteem that supports their decision-making. Self-worth encourages them to achieve their goals and contributes to positive development, facilitating their ability to face the challenges of adolescence and grow into healthy, confident, and resilient individuals (Tomé et al., 2019).

3.2 Models and theories

Positive development is a field of study that focuses on promoting the competencies, resources, and qualities necessary for youth to become healthy and productive adults (Bowers et al., 2020). Over time, several models and theories have emerged to understand and guide this process. Without attempting to present all models and theories, the following section will outline those that have been most referenced in the literature over time.

3.2.1 Five C’s model of positive youth development

This model, developed by Lerner et al. (2014), posits that positive youth development can be understood through five key areas, known as the “5 C’s”: Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring. Competence assesses skills in specific areas (e.g., academic, social, cognitive); Confidence focuses on self-esteem and positive identity; Connection examines positive relationships with people and institutions; Character addresses moral values and integrity; and Caring emphasizes empathy and concern for others (Tomé et al., 2019). This model shifted the focus of adolescent research from a deficit-based approach (e.g., prevention of risky behaviors) to one that emphasizes youth capabilities, potential, and well-being (Bowers et al., 2020; Geldhof et al., 2019).

3.2.2 Self-determination theory (SDT)

SDT was created by Deci and Ryan (1985) and evaluates three basic needs: (a) competence, which focuses on the feeling of effectiveness in interacting with the environment; (b) autonomy, which pertains to the control of one’s own actions and decisions; and (c) relatedness, which refers to how we are valued by others. According to this theory, when these needs are met, youth are more likely to experience psychological well-being and engage in positive behaviors (Ryan and Deci, 2017). Niemiec and Ryan (2019) add that this theory can be used to understand the motivational basis for effective performance. Vansteenkiste et al. (2020) highlight its application in promoting positive youth development.

3.2.3 Ecological systems theory of human development

Bronfenbrenner’s theory (1989; Rosa and Tudge, 2017) emphasizes that youth development is influenced by the social environment and the systems that comprise it, namely: (a) the microsystem, which constitutes the immediate environment (e.g., family, school, friends); (b) the mesosystem, which includes interactions between different microsystems; (c) the exosystem, which refers to social factors that influence the youth indirectly (e.g., parents’ work, educational policy); (d) the macrosystem, which encompasses the culture, values, and social norms that influence all previous systems; and (e) the chronosystem, which characterizes changes and continuity over time (Neal and Neal, 2017).

3.2.4 Resilience model

The resilience model is based on the research of Masten and Garmezy (1985), Rutter (1985), and Werner and Smith (1992) and refers to the ability of youth to successfully face and overcome adversities. It highlights the importance of providing youth with internal and external resources to cope with challenges and promote positive development (Masten, 2018). In this context, Luthar et al. (2019) refer to the existence of protective factors, including personal attributes, positive relationships, and community support; and risk factors that refer to adverse circumstances such as poverty, abuse, or family problems (Ungar, 2019).

3.2.5 Psychosocial development theory

Proposed by Erikson (1968), this theory describes the stages of psychosocial development throughout life. In the context of adolescence, it highlights the identity versus role confusion crisis. According to Kroger (2017) and Schwartz et al. (2019), identity formation is crucial for a successful transition to adulthood. Syed and McLean (2018) complement this idea by noting that this theory significantly influences career development, as it shows how commitment and identity influence young people’s career choices.

3.2.6 Moral development theory

Created by Kohlberg in the 1950s, this theory focuses on moral and ethical development, which directly influences youth character and integrity (Kohlberg and Hersh, 1977; Mathes, 2021). According to the author, this development occurs through three main levels: (a) the pre-conventional, where moral judgment is based on rule obedience to avoid punishment, and justice is seen in terms of immediate exchange or reciprocity; (b) the conventional, where behavior is directed toward social approval and maintaining order in society; and (c) the post-conventional, which views morality in terms of universal human rights and principles that may or may not be reflected in laws (Nainggolan and Naibaho, 2022). Kohlberg demonstrated that morality develops with age, though not all adults reach the highest levels of moral development (Ahmeti and Ramadani, 2021).

3.2.7 Theory of multiple intelligences

In 1983, Gardner proposed the theory of multiple intelligences, which posits the existence of 10 relatively autonomous but interconnected intelligences that arise from the interaction between biological potential and learning from environmental conditions. Initially, seven intelligences were identified: musical, linguistic, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, logical-mathematical, intrapersonal, and interpersonal (Gardner, 1993). Later, Gardner (2003) proposed three additional intelligences: naturalist, existential, and spiritual. The author rejects the hypothesis that the various intelligences can be coordinated by a general executive function and argues that any intellectual competence must encompass a set of abilities that allow the individual to solve problems or difficulties within a specific cultural context (Hanafin, 2014).

3.2.8 Social skills model

This model emerged in England in the 1970s with Argyle (1978), but several authors have since contributed to its study (e.g., Del Prette and Del Prette, 2021; Milani, 2022; Vila et al., 2021). This model emphasizes the importance of social and emotional skills for positive youth development. Jones and Kahn (2017) support this idea, arguing that communication skills, problem-solving, and empathy are essential for young people’s academic, professional, and personal success. Argyle (2019) and Weissberg et al. (2018) add that socio-emotional learning plays a vital role in preparing youth for the challenges of adult life. Similarly, Miller et al. (2020) argue that this learning can be an effective tool to address mental health needs and promote educational success.

3.2.9 Cognitive development theory

Emerging in 1970 from Piaget’s work, this theory, though primarily focused on childhood, also has implications for youth development (Piaget, 1970). The transition to formal operational thinking allows adolescents to address moral, social, and personal issues in a more complex and abstract manner (Lourenço, 2016). This theory emphasizes active learning and knowledge acquisition through interaction with the environment (Case and Okamoto, 2017). Piaget was criticized for underestimating the influence of culture, education, and socialization on cognitive development, but his theory remains a central reference in education and developmental psychology (Müller et al., 2018).

3.3 Autonomy and curricular flexibility

According to Lima (2020), autonomy and curricular flexibility are central concepts in contemporary educational reforms, aimed at making education more tailored to individual student needs and the specificities of each school context. Curricular autonomy refers to the ability of schools and teachers to adapt the curriculum to the needs of their students and the local context (Silva and Fraga, 2021). This may include topics that align with student interests, teaching methods for different learning styles, and/or the integration of projects involving the local community (Carvalho et al., 2023).

Curricular flexibility, on the other hand, relates to the ability to adjust and modify the curriculum to respond to the constant changes in society, technology, and the workforce (Esi, 2024). The organization of content and the creation of varied learning pathways promote an interdisciplinary approach that helps prepare students for an uncertain and dynamic future (Zohar et al., 2024).

4 Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out using a quantitative methodology that, through a questionnaire survey, focused on collecting numerical data that can be measured objectively. This approach is suitable for quantifying attitudes, opinions and/or behaviors that, based on a representative sample, can be generalized to a population (Mohajan, 2020). However, data were collected from a convenience sample due to ease of access to participants, and as such, results cannot be inferred for the entire population with the same confidence as with probability sampling (Mweshi and Sakyi, 2020). It is important to note that at the time of data collection, more than half of the students were undertaking internships as part of their courses, which is why the response rate was around 45%.

4.1 Participants

The sample consisted of 381 students from three Portuguese vocational schools, aged between 15 and 19 years (M = 14.99, SD = 1.44), of which 55.2% were male.

4.2 Data collection instruments

Social and Emotional Competencies. Social and Emotional Competencies were assessed using a 16-item self-report instrument originally developed by Zych et al. (2018) and later validated for the Portuguese population by Lobo et al. (2019). This tool measures four key dimensions of social and emotional competencies, each essential for personal and interpersonal functioning. These dimensions—Self-awareness, Self-management and Motivation, Social Awareness and Prosocial Behavior, and Decision-making—are designed to provide a holistic view of individuals’ socio-emotional capabilities. Below is a detailed explanation of each dimension, with examples of items and their theoretical underpinnings.

1. Self-awareness: refers to the ability to recognize and understand one’s emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behavior. This dimension also includes the capacity for accurate self-assessment, helping individuals recognize their strengths and limitations.

Items: “I know how to classify my emotions”—This item measures an individual’s ability to identify and label their emotions correctly, a critical skill for emotional regulation.

“I can understand why I feel the way I do”—Assesses emotional insight, helping individuals gain deeper awareness of the root causes of their emotions.

Self-awareness is the foundation of emotional intelligence, allowing individuals to navigate their emotional landscape and improve their interpersonal interactions. It plays a crucial role in emotional regulation and contributes to more effective decision-making and self-reflection.

2. Self-management and Motivation: refers to the ability to regulate one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors effectively in different situations. It involves managing stress, controlling impulses, and motivating oneself to set and achieve personal goals.

Items: “My goals are clear”—This item evaluates goal-setting ability, which is crucial for maintaining motivation and focus on long-term objectives.

“I can control my emotions when faced with difficult situations”—Assesses the ability to stay composed and manage emotional reactions under stress, which is essential for problem-solving and maintaining resilience.

Self-management is key to emotional resilience, helping individuals remain focused on their objectives and adapt to challenges. It also includes self-motivation, ensuring that individuals remain driven and persistent even in the face of adversity.

3. Social Awareness and Prosocial Behavior: Social awareness is the ability to empathize with others, understand their emotions and perspectives, and recognize social cues. Prosocial behavior refers to actions that benefit others, such as offering help and showing empathy.

“I offer help to those in need”—This item evaluates prosocial tendencies, focusing on an individual’s willingness to engage in altruistic behaviors.

“I can tell when someone is upset, even if they do not say it”—Measures empathetic sensitivity, the ability to understand others’ emotions through nonverbal cues, which is crucial for effective interpersonal relationships.

This dimension fosters social harmony and helps build supportive relationships. It plays a significant role in team collaboration, conflict resolution, and fostering inclusive environments. High social awareness promotes prosocial actions, benefiting both individual and group well-being.

4. Decision-making: refers to the ability to make thoughtful and responsible choices, taking into account the well-being of oneself and others. This includes weighing the consequences of various options and considering ethical aspects in decision-making.

“I do not make decisions carelessly”—Assesses the ability to make well-considered decisions by evaluating the potential consequences before acting.

“I think carefully before making important decisions”—Evaluates reflective thinking and the consideration of multiple factors in decision-making processes.

Decision-making is critical for personal success and effective social functioning. It helps individuals manage life challenges and responsibilities while promoting ethical reasoning and thoughtful consideration of the impact of their actions on others.

Participants respond to each of the 16 items on a five-point Likert scale, where they indicate their level of agreement with each statement: 1: Strongly disagree; 2: Disagree; 3: Neither agree nor disagree; 4: Agree; 5: Strongly agree.

This scale provides a nuanced understanding of participants’ perceived competencies across the four dimensions, enabling a comprehensive assessment of social and emotional skills.

This 16-item scale offers a reliable measure of social and emotional competencies, which are increasingly recognized as vital for success in academic, professional, and personal domains. High levels of these competencies are linked to better mental health, improved academic performance, and more positive social interactions. By using this scale, researchers and educators can assess key areas of socio-emotional development and implement interventions aimed at enhancing these competencies in various populations.

The results were calculated by summing the items, and the higher the value, the more developed the assessed competencies are. In the scale validation study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were obtained, ranging from 0.67 to 0.87.

Self-concept. The Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (PHCSCS), developed by Piers and Harris (2002), is a widely utilized self-report instrument designed to measure self-concept in children and adolescents. Comprising 60 items, this scale assesses multiple dimensions of self-concept, providing a detailed evaluation of how young individuals perceive themselves across various life domains. The participants respond to each item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

The first dimension, Behavior, evaluates a child’s perception of their conduct, particularly in structured environments like school. It reflects their self-assessment of discipline, rule-following, and overall behavior. An example item from this dimension is, “I behave well at school,” which assesses the child’s self-perception of their behavior in academic settings, an environment where good conduct is often associated with positive self-concept. Positive self-perceptions in this domain tend to correlate with better academic and social outcomes, whereas negative perceptions can be linked to behavioral problems and lower self-esteem.

The second dimension, Anxiety, captures the child’s feelings of nervousness, worry, and fear in various situations, whether social or personal. An example item is, “I am often afraid,” which measures the child’s tendency to experience fear and anxiety, factors that can negatively impact self-concept and mental health. Elevated levels of anxiety can hinder a child’s overall self-concept, potentially leading to issues with confidence and emotional well-being. This dimension is particularly useful in identifying children who may require emotional support.

Emotional Status, the third dimension, evaluates the child’s perception of their emotional well-being and relationships, focusing on their sense of self-worth and how they feel valued by their peers. An example item is, “My friends like my ideas,” which assesses the child’s perception of acceptance within their peer group. Positive perceptions of emotional status are essential for a healthy self-concept, as children who feel valued by their friends are more likely to have a higher sense of self-worth, whereas negative feelings in this area can lead to feelings of isolation.

The fourth dimension, Popularity, assesses how children view their social standing among peers, including how many friends they have and their overall sense of social acceptance. An example item is, “I have many friends,” which evaluates the child’s perception of their popularity. Social inclusion and popularity are critical aspects of a child’s self-concept, as feeling accepted by peers contributes positively to self-esteem, while feelings of rejection can diminish it.

Physical Appearance, the fifth dimension, assesses how children feel about their looks and physical characteristics. Items in this dimension explore the child’s satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their appearance. For instance, “I like my appearance” is an item that directly measures body image satisfaction, a crucial component of self-esteem, especially during adolescence when body image issues can profoundly affect self-worth.

Finally, the Happiness-Satisfaction dimension measures the child’s overall sense of contentment with their life. This dimension reflects their general outlook on life and their emotional well-being. An example item, “I am a happy person,” assesses the child’s self-reported happiness. High scores in this dimension typically indicate a positive overall self-concept, while lower scores may point to emotional difficulties.

In summary, the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale provides a comprehensive assessment of self-concept by evaluating behavior, anxiety, emotional status, popularity, physical appearance, and happiness-satisfaction. The tool offers valuable insights into the various facets of a child’s self-perception, contributing to a holistic understanding of their emotional and social development.

The results were obtained by summing all the items that make up each dimension, where a higher value corresponds to a higher level of self-concept among respondents. The original scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.89 to 0.92.

Positive Youth Development. The Positive Youth Development Short Form (PYD-SF) scale, developed by Arnold et al. (2012) and validated for the Portuguese population by Tomé et al. (2019), is a self-report instrument designed to assess key developmental attributes in adolescents. It consists of 34 items that evaluate five core dimensions: Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring. Each of these dimensions provides a comprehensive view of positive youth development by capturing essential aspects of social, emotional, and moral growth. Responses to each item are rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

The first dimension, Competence, refers to a young person’s self-perception of their abilities in areas such as academics, social interactions, and physical tasks. An example item, “I am successful in the work I do in the classroom,” reflects the individual’s confidence in their academic achievements. This dimension is essential because high levels of competence contribute to a sense of mastery and self-efficacy, encouraging goal-setting behavior and success in both personal and academic contexts.

The second dimension, Confidence, measures an adolescent’s internal sense of self-worth and overall satisfaction with who they are. For example, “I am very happy with who I am” gauges how comfortable and content the individual feels with their identity. Confidence is closely linked to self-esteem and emotional well-being, making it a critical factor in fostering resilience and a positive outlook on life.

Connection, the third dimension, assesses the strength of an adolescent’s relationships with family, friends, and the broader community. An example item is “My friends care about me,” which highlights the importance of supportive social networks. Positive connections with others are fundamental for fostering a sense of belonging, security, and emotional support, all of which are vital for healthy development.

The fourth dimension, Character, reflects the adolescent’s sense of moral responsibility and ethical behavior. Items such as “I contribute to making the world a better place to live” assess the individual’s commitment to values like honesty, integrity, and social responsibility. Character development is a key component of positive youth development, as it promotes a sense of purpose and helps young people navigate social expectations and moral dilemmas.

Finally, Caring refers to the adolescent’s empathy and compassion toward others. An example item, “It bothers me when bad things happen to others,” captures the individual’s concern for the well-being of others. Caring is integral to developing prosocial behavior and cultivating healthy interpersonal relationships, as it encourages empathy and altruism.

Overall, the PYD-SF scale provides a robust measure of positive youth development by integrating these five dimensions, each contributing to the holistic growth and well-being of adolescents. The scale’s ability to capture these attributes makes it a valuable tool for understanding how young people navigate challenges, build relationships, and develop into capable, confident, and caring individuals.

The internal consistency of the original scale and the Portuguese version presented Cronbach’s alpha indices ranging from 0.73 to 0.96.

Sociodemographic questions (e.g., gender, age) were also included to characterize the sample.

4.3 Procedures

The items from the three questionnaires and the set of sociodemographic questions were entered into Google Forms, and the link was sent to the directors of the three vocational schools, who distributed it to their students. Participants were informed about the research objectives, and it was ensured that the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union would be respected [Regulation (EU) No. 679/2016, of April 26]. Multivariate statistical techniques were employed to analyze the relationships between variables simultaneously. Initially, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component analysis (PCA) to assess the construct validity of the instruments used, followed by an evaluation of their reliability. To confirm the validity of theoretical constructs, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was also performed. This technique allowed for verifying whether the observed data are consistent with the predefined factor structure, i.e., whether the latent constructs proposed in the theoretical model explain the correlations between the observed variables. The model fit, as well as the factor loadings, variances, covariances, and measurement errors, were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood method. To compare means, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine whether the average values of the constructs under study differ significantly depending on the school to which the students belong. Finally, multiple correspondence analysis was employed to reduce the dimensionality of the categorical data set and project the variables and categories into a lower-dimensional space, providing a simplified representation of the students’ profiles across the three schools. All analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software.

5 Results

5.1 Data analysis

To understand the internal structure of the instruments used for data collection and identify their dimensions, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was conducted (Hair et al., 2018). Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) indicators and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were also calculated to ensure that the item correlations were sufficient and appropriate (Marôco, 2021). The extraction of components followed the Kaiser-Guttman criterion, considering the percentage of explained variance (Roni and Djajadikerta, 2021). In the initial phase, all items from the three scales were used, but after the PCA, only items with a correlation greater than 0.40 with the respective factor, a correlation difference greater than 0.20, and at least two associated items were selected. Consequently, only seven dimensions were retained, which were renamed according to the items they comprised: Self-concept (α = 0.74), Self-management (α = 0.74), Decision-making (α = 0.74), Social Awareness (α = 0.68), Self-esteem (α = 0.89), Cooperation (α = 0.86), and Interpersonal Relationships (α = 0.87).

Subsequently, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm that the latent factors were responsible for the behavior of the manifest variables (Alavi et al., 2020). The obtained data were compared with the fit indices recommended by Xia and Yang (2018), and it was verified that the model is well-fitted to the sample data [χ2 = 2.09, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, LO90 = 0.07, HI90 = 0.15].

The exploratory analysis was conducted to understand the factor matrix of the data and to identify patterns, trends, and relationships before proceeding with more rigorous analyses. The CFA aimed to validate the factor structure obtained from the PCA. Both analyses are essential and complementary and should be performed to ensure the validity and reliability of the instruments, thereby guaranteeing the rigor of the obtained results.

5.2 Comparison of means of the variables under study based on the school attended by students

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics of the variables under study for each school. The results showed that students from School 1 had the highest average scores in Self-Management, Social Awareness, and Decision-Making, suggesting that they are balanced and aware individuals. They demonstrate a strong ability to manage their own emotions and behaviors, maintaining organization, discipline, and resilience in the face of challenges. These students work well in groups, promote an inclusive and harmonious environment, and carefully consider all options and their short- and long-term impacts.

School 2 did not stand out in any specific dimension but showed average values above the central point of the scale in all evaluated competencies. Generally, students attending this school have a good self-perception and find it easy to relate to their peers and teachers. They believe in their potential and use constructive criticism to improve weaknesses without feeling demotivated. They demonstrate respect for others’ opinions and feelings and are valuable members in any group.

Lastly, School 3 is where students exhibit the highest levels of Self-Concept, Self-Esteem, Cooperation, and Interpersonal Relationships. These dimensions characterize students who show confidence and self-assurance without excess. They have a balanced view of their capabilities and limitations, allowing them to face challenges with a positive and resilient attitude. These students are empathetic, understanding, communicative, and know how to establish and maintain healthy relationships.

The data analysis also revealed statistically significant differences in Decision-Making [F(2,378) = 4.157, p < 0.05] and Interpersonal Relationships [F(2,378) = 4.281, p < 0.05] based on the school attended by the students. A post-hoc analysis revealed that the primary differences in Decision-Making occur between School 1 and School 2, and in Interpersonal Relationships between School 1 and School 3.

The decision-making process was based on a 95% confidence interval, which complements a 5% significance level. Both concepts are closely related, as a 95% confidence interval and a 5% significance level provide complementary approaches to determining the presence of significant effects or differences.

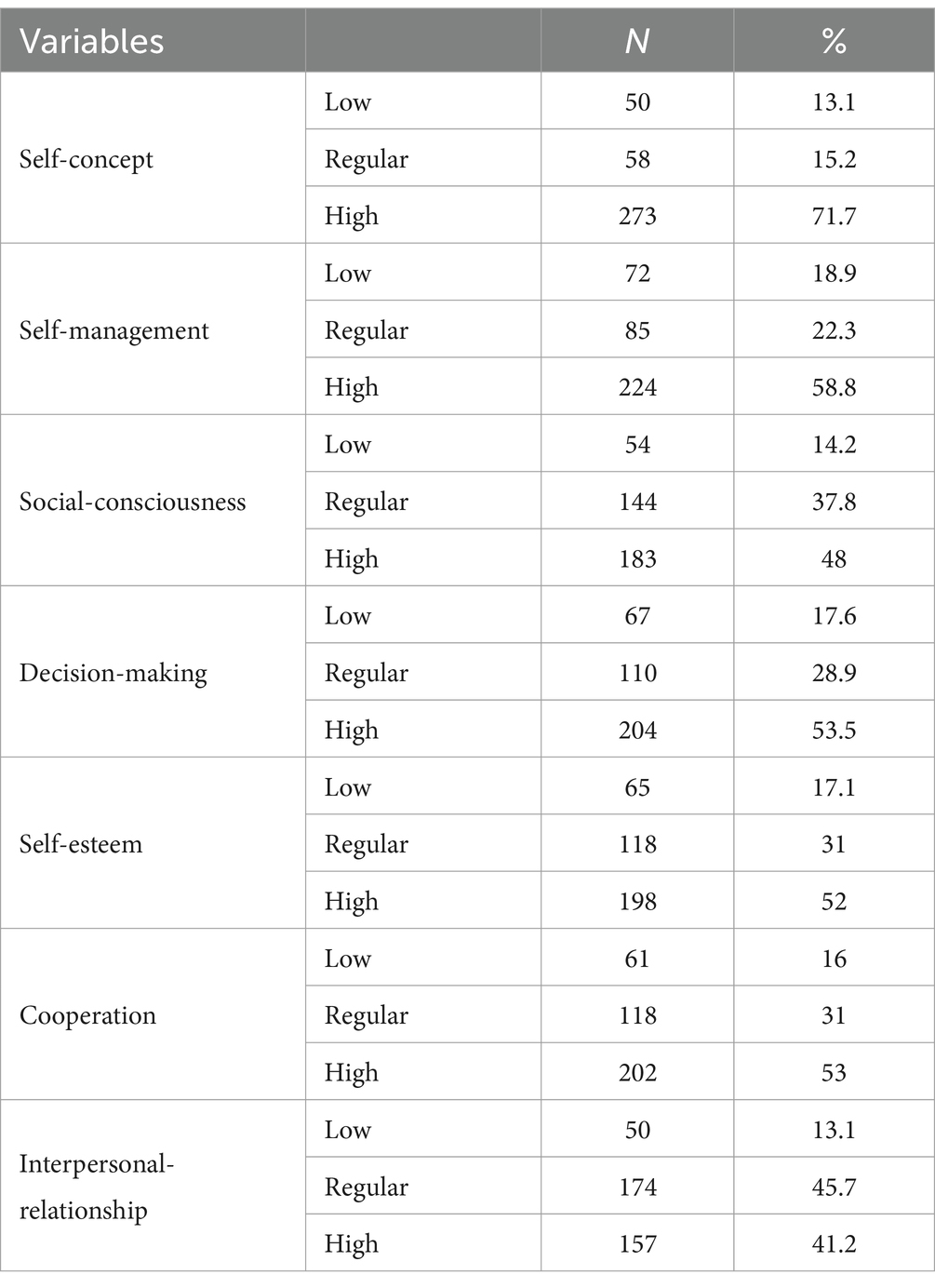

5.3 Profile of students in vocational schools

To determine the profile of students across the three vocational schools, a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) was conducted. To enhance data readability, the dimensions were recoded into Low, Regular, and High categories based on their midpoint (Table 2).

Through Figure 1, it is possible to observe that School 1, located between the third and fourth quadrants, encompasses students who exhibit high levels of Social Awareness and Cooperation. However, these students are situated at a midpoint concerning Decision Making. Consequently, they are diligent, responsible, and attentive to the needs and well-being of others (e.g., peers, friends, family). Additionally, they are sensitive to social dynamics affecting society (e.g., inequalities, social injustices) and are strong advocates for human rights.

In the second quadrant, School 2 is positioned, where students display average levels of Cooperation, Social Awareness, and Interpersonal Relationships. Accordingly, they adhere to the rules and norms established by the school both in the classroom and in other school activities. These students respect teachers and peers, participate in classes, and avoid conflicts.

School 3, situated in the third quadrant, includes students who exhibit high levels in Interpersonal Relationships, Self-Esteem, Self-Management, Self-Concept, and Decision Making. These students actively engage in school and extracurricular activities, demonstrate understanding and sensitivity to the emotions and needs of others, are effective team workers, and contribute to fostering a supportive and collaborative environment. They are self-disciplined and capable of meeting deadlines without constant supervision. They maintain a positive outlook on life and positively influence their surroundings, which generally leads to their success.

6 Discussion

Despite the simultaneous implementation of the SER Project across the three schools, it was observed that School 3 yielded the best results regarding the assessed dimensions. This outcome may be attributed to the student profile and/or the specificity of the courses offered (e.g., Accounting Technician, Aircraft Mechanic and Flight Material, Legal Services Technician).

The results of this study align with those found by Jaureguizar et al. (2018), emphasizing the importance of social and emotional skills in positive youth development. It was found that the competencies of students from the three schools may be related to the educational environment and pedagogical practices of each institution.

Analysis of the school profiles revealed that School 1 includes students with high levels of Social Awareness and Cooperation. This result is consistent with Bronfenbrenner’s (1989) Ecological Theory of Human Development, which suggests that students’ immediate environment, such as the school and its values, directly influences the development of these competencies.

Conversely, School 2 did not stand out in any particular competency but showed positive results across all evaluated dimensions. These results can be validated by the Five C’s Model of Positive Youth Development by Lerner et al. (2014), which posits that a balanced approach can contribute to a more uniform competency profile among students.

Lastly, it was found that students from School 3 demonstrated high levels of Interpersonal Relationship, Self-Esteem, and Self-Management, which aligns with Rogers et al. (2020) theory regarding the significance of positive self-concept in youth development. As the study indicates, a strong self-image may be associated with students’ ability to relate well to others and manage their own emotions.

It was also observed that significant differences between schools, particularly between School 1 and School 3, concerning Interpersonal Relationships, can be partially explained by Deci and Ryan’s (2012) Self-Determination Theory (SDT). This theory highlights how autonomy and a positive relational environment can promote healthy emotional development and good peer relationships. The influence of the school environment on the development of specific competencies is corroborated by Gardner’s (1983) Theory of Multiple Intelligences, which suggests that different intelligences (e.g., interpersonal, intrapersonal) may be more or less stimulated depending on the educational context. The distinct pedagogical practices in the three studied schools likely contributed to the differentiated development of skills among students.

Additionally, it was found that students from School 2 exhibited similar values across all social and emotional dimensions, indicating that an educational environment valuing curricular flexibility and proactivity, as advocated by Niemiec and Ryan (2019), may result in more holistic and uniform development of social and emotional skills. The fact that School 1 excels in Social Awareness and Cooperation while School 3 stands out in Interpersonal Relationships and Self-Esteem may indicate that different pedagogical approaches influence specific aspects of youth development. This is a central concept in Erikson’s (1968) Psychosocial Development Theory, particularly regarding identity formation and self-image during adolescence.

As evidenced by this study’s results, the effectiveness of the SER Project aligns with Masten’s (2018) Resilience Model, which posits that educational programs focused on social and emotional competencies strengthen youths’ internal resources, enabling them to overcome challenges and build a solid foundation for positive development.

The statistically significant differences observed between schools, particularly in Decision-Making, reflect the importance of adapting educational interventions to the specific profile of each student group, as suggested by Ungar (2019). This author argues that implementing personalized educational approaches is crucial for promoting resilience and well-being among youth in diverse contexts.

The analysis of the competencies developed by students from the three schools reveals that curricular flexibility, one of the pillars of the SER Project, had a positive impact on students’ positive development.

7 Conclusion

This exploratory study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a project centered on autonomy and curricular flexibility. The objective was to understand the competency profiles of students from three Portuguese vocational schools. The evaluated dimensions include social competencies, socio-emotional competencies, and positive development, with the goal of identifying those that are most developed and those needing improvement. This investigation provides a detailed analysis of how each school impacts the development of its students’ socio-emotional competencies. This is significant because these skills are increasingly valued in both the labor market and personal life. Additionally, the study serves as a tool for adjusting or strengthening each school’s pedagogical practices based on the specific profiles and needs of its students.

The results of this study highlight the need for differentiated educational policies tailored to students’ characteristics and needs, as these may be more effective than a uniform approach. Thus, it is essential to grant schools greater autonomy to adapt curricula to their realities.

The development of the analyzed competencies has direct implications for students’ future professional lives. Skills such as Decision-Making, Self-Esteem, and Social Awareness are highly valued in the current job market. Schools that successfully promote these competencies among their students significantly contribute to their employability and professional success. The relationship between the educational environment and the competencies developed by students is evident in this study. Schools that foster a collaborative and flexible learning environment, as exemplified by the schools analyzed, tend to generate more robust competency profiles among their students. The obtained results reinforce the importance of implementing pedagogical models that not only impart knowledge but also encourage students’ social and emotional development.

7.1 Limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

Despite the positive results, this study has limitations, including its focus on only three schools from a specific private education group, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the assessment of competencies was based on self-reports, which may be influenced by participants’ personal biases. Future studies should consider expanding this research to other schools and regions.

Another limitation pertains to the exclusive use of a quantitative methodology. It is suggested that complementary evaluation methods, such as direct observation and interviews, be included to obtain a more detailed understanding of students’ competencies. Given this, it is pertinent to continue this type of research to ensure the continuous improvement of the educational environment and the holistic development of students. Longitudinal studies are also recommended to track and monitor the development of competencies over time. Comparative studies with data from other countries should be conducted to identify best practices and adapt them to the Portuguese context. Finally, it is important to further investigate how the school environment and the use of new technologies influence students’ competency development.

In a constantly changing world, social and emotional skills are critical to the academic and professional success of young people, as they influence the ability to interact, make decisions, and manage emotions. This study is of paramount importance for assessing the effectiveness of the SER Project, which aims to promote autonomy and curricular flexibility in the three vocational schools analyzed. Evaluating how these elements influence the development of social and emotional skills is essential for understanding whether the project meets the students’ needs. The results, in addition to contributing to the implementation of innovative educational policies, help adapt curricula and teaching methods to the specific needs of students, fostering more comprehensive development aligned with the demands of the labor market. The execution of this study involved a rigorous methodological approach that provided insights which can contribute to improving educational practices and the development of policies better suited to the needs of students.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MN: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RR: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The data protection of participants and their respective schools was ensured in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union [Regulation (EU) n. 679/2016, of April 26].

References

Ahmeti, K., and Ramadani, N. (2021). Determination of Kohlberg’s moral development stages and chronological age. Int. J. Soc. Hum. Sci. 8, 37–48.

Akbulaev, N., Mammadov, I., and Shahbazli, S. (2021). Accounting education in the universities and structuring according to the expectations of the business world. Univ. J. Account. Finance 9, 130–137. doi: 10.13189/ujaf.2021.090114

Alavi, M., Visentin, D., Thapa, D., Hunt, G., Watson, R., and Cleary, M. (2020). Chi-square for model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 76, 2209–2211. doi: 10.1111/jan.14399

Alsaker, F., and Kroger, J. (2020). “Self-concept, self-esteem, and identity” in Handbook of adolescent development. eds. S. Jackson and L. Goossens (New York: Psychology Press), 90–117.

Argyle, M. (2019). “Social skills” in Companion encyclopedia of psychology (New York: Routledge), 454–482.

Arnold, M. E., Nott, B. D., and Meinhold, J. L. (2012). The positive youth development inventory-short form (PYD-SF): an instrument for assessing positive youth development in adolescents. J. Youth Dev. 7, 24–34. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2012.150

Arslan, E. (2021). Investigation of pre-school childrens’ self-concept in terms of emotion regulation skill, behavior and emotional status. Ann. Psychol. 37, 508–515. doi: 10.6018/analesps.364771

Bowers, E., Geldhof, G., Johnson, S., Lerner, J., and Lerner, R. (2020). Special issue: positive youth development. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 2037–2040. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01295-7

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). “Ecological systems theory” in Annals of child development. ed. R. Vasta, vol. 6 (New York: JAI Press), 187–249.

Carvalho, A., Cosme, A., and Veiga, A. (2023). Inclusive education systems: the struggle for equity and the promotion of autonomy in Portugal. Educ. Sci. 13, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/educsci13090875

Case, R., and Okamoto, Y. (2017). The role of central conceptual structures in the development of children’s thought. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 61, 83–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1996.tb00538.x

Casino-García, A., Llopis-Bueno, M., and Llinares-Insa, L. (2021). Emotional intelligence profiles and self-esteem/self-concept: an analysis of relationships in gifted students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–23. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031006

Crato, N. (2020). “Curriculum and educational reforms in Portugal: an analysis on why and how students’ knowledge and skills improved” in Audacious education purposes: how governments transform the goals of education systems, (Cambridge) 209–231.

Deci, E., and Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Thousand Oaks: Springer.

Deci, E., and Ryan, R. (2012). “Self-determination theory” in Handbook of theories of social psychology. eds. P. Van Lange, A. Kruglanski, and E. Higgins (Berlin: Sage), 416–437.

Esi, M. (2024). Comprehensive implications of “curricular flexibility” in education. Int. J. Soc. Educ. Innov. 11, 65–75.

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: the theory in practice. Barcelona: Basic Books/Hachette Book Group.

Gardner, H. (2003). La inteligencia reformulada: las inteligencias multiples en el siglo XXI. Barcelona: Paidós.

Geldhof, G., Bowers, E., and Lerner, R. (2019). Positive youth development: theory, research, and applications. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 56, 45–88. doi: 10.1016/bs.acdb.2018.11.004

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., and Tatham, R. (2018). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall: Pearson.

Hanafin, J. (2014). Multiple intelligences theory, action research, and teacher professional development: the Irish MI project. Austral. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 126–141. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n4.8

Jaureguizar, J., Garaigordobil, M., and Bernaras, E. (2018). Self-concept, social skills, and resilience as moderators of the relationship between stress and childhood depression. Sch. Ment. Heal. 10, 488–499. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-9268-1

Jones, S., and Kahn, J. (2017). The evidence bases for how we learn: supporting students' social, emotional, and academic development. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute.

Kohlberg, L., and Hersh, R. (1977). Moral development: a review of the theory. Theory Pract. 16, 53–59. doi: 10.1080/00405847709542675

Kroger, J. (2017). Identity development in adolescence and adulthood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lerner, R., Wang, J., Chase, P., Gutierrez, A., Harris, E., Rubin, R., et al. (2014). Using relational developmental systems theory to link program goals, activities, and outcomes: the sample case of the 4-H study of positive youth development. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2014, 17–30. doi: 10.1002/yd.20110

Lima, L. (2020). Autonomy and curriculum flexibility: when schools are challenged by the government. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Educacional, 172–192. doi: 10.34632/investigacaoeducacional.2020.8505

Lobo, I., Silva, J. T., Ferreira, P., and Matos, A. (2019). Validation of the social and emotional competencies scale for the Portuguese adolescent population. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 32, 12–21. doi: 10.1186/s41155-019-0114-7

Lourenço, O. (2016). Piaget's theory of cognitive development: what is it and what is it not? Int. J. Theory Res. 16, 23–34. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2016.1143266

Luthar, S., Crossman, E., and Small, P. (2019). “Resilience and adversity” in Handbook of developmental psychopathology (Berlin: Springer), 37–56.

Marôco, J. (2021). Structural equation analysis theoretical foundations, software & applications. Pêro Pinheiro: Report Number.

Masten, A. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: past, present, and promise. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 10, 12–31. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12255

Masten, A., and Garmezy, N. (1985). “Risk, vulnerability, and protective factors in developmental psychopathology” in Advances in clinical child psychology. eds. B. Lahey and A. Kazdin (US: Springer), 1–52.

Mathes, E. W. (2021). An evolutionary perspective on Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. Curr. Psychol. 40, 3908–3921. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00348-0

Melendro, M., Campos, G., Rodríguez-Bravo, A. E., and Arroyo Resino, D. (2020). Young people’s autonomy and psychological well-being in the transition to adulthood: a pathway analysis. Front. Psychol. 11, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01946

Milani, M. (2022). The effectiveness of social skills training on happiness and mental health of adolescent males. Mental Health Res. Pract. 1, 14–22. doi: 10.22034/MHRP.2022.154061

Miller, J., Lee, J., and Song, Q. (2020). Social-emotional learning as a tool to address mental health needs and promote educational success. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 112:104935. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104935

Mohajan, H. (2020). Quantitative research: a successful investigation in natural and social sciences. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 9, 50–79. doi: 10.26458/jedep.v9i4.679

Monell, E., Clinton, D., and Birgegård, A. (2022). Emotion dysregulation and eating disorder outcome: prediction, change and contribution of self-image. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 95, 639–655. doi: 10.1111/papt.12391

Moneva, J., and Tribunalo, S. (2020). Students’ level of self-confidence and performance tasks. Asia Pacific J. Acad. Res. Soc. Sci. 5, 42–48.

Müller, U., Sokol, B., and Overton, W. (2018). Reframing Piaget’s theory: the biological roots of cognitive development. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 54, 215–258. doi: 10.1016/bs.acdb.2017.10.003

Murano, D., Lipnevich, A., Walton, K., Burrus, J., Way, J., and Anguiano-Carrasco, C. (2021). Measuring social and emotional skills in elementary students: development of self-report Likert, situational judgment test, and forced choice items. Personal. Individ. Differ. 169:110012. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110012

Mweshi, G., and Sakyi, K. (2020). Application of sampling methods for the research design. Arch. Bus. Rev. 8, 180–193. doi: 10.14738/abr.811.9042

Nainggolan, M., and Naibaho, L. (2022). The integration of Kohlberg moral development theory with education character. Techn. Soc. Sci. J. 31, 203–212. doi: 10.47577/tssj.v31i1.6417

Neal, J., and Neal, Z. (2017). Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Soc. Dev. 22, 722–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00600.x

Niemiec, C., and Ryan, R. (2019). “Self-determination theory: a framework for understanding the motivational basis of effective performance” in Performance psychology: perception, action, cognition, and emotion. (New York: Routledge), 65–87.

Orth, U., and Robins, R. (2022). Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classic question. Am. Psychol. 77, 5–17. doi: 10.1037/amp0000922

Orth, U., Robins, R., and Widaman, K. (2019). Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 116, 835–859. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000204

Piaget, J. (1970). “Piaget's theory” in Carmichael's manual of child psychology. ed. P. Mussen (New York: Wiley), 703–732.

Piers, E., and Harris, D. (2002). Piers-Harris Children’s self-concept Scale-2. Psychometric properties of the social and emotional competencies questionnaire (SEC-Q) in youth and adolescents. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 51, 943–106. doi: 10.2307/1129534

Priestley, M., Alvunger, D., Philippou, S., and Soini, T. (Eds.) (2021). Curriculum making in Europe: policy and practice within and across. Bradford: Emerald.

Ramadhani, M., and Rahayu, E. (2020). Competency improvement through internship: an evaluation of corporate social responsibility program in vocational school. Int. J. Evaluat. Res. Educ. 9, 625–634. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20571

Rogers, M., Creed, P., and Glendon, A. (2020). Adolescents’ perceived self-concept and the impact on career aspirations: a longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 79, 247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.015

Roni, S., and Djajadikerta, H. (2021). Data analysis with SPSS for survey-based research. Berlin: Springer.

Rosa, E., and Tudge, J. (2017). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: its evolution from ecology to bioecology. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 5, 243–258. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12022

Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 147, 598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598

Ryan, R., and Deci, E. (2017). Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

Sagone, E., De Caroli, M., Falanga, R., and Indiana, M. (2020). Resilience and perceived self-efficacy in life skills from early to late adolescence. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 882–890. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2020.1771599

Sánchez-Rojas, A., García-Galicia, A., Vázquez-Cruz, E., Montiel-Jarquín, A., and Aréchiga-Santamaría, A. (2022). Self-image, self-esteem and depression in children and adolescents with and without obesity. Gac. Med. Mex. 158, 118–123. doi: 10.24875/GMM.M22000653

Schwartz, S., Zamboanga, B., Meca, A., and Ritchie, R. (2019). Identity in emerging adulthood: reviewing the field and looking forward. Emerg. Adulthood 7, 441–448. doi: 10.1177/2167696818777042

Silva, S., and Fraga, N. (2021). Autonomia e flexibilidade curricular como instrumentos gestionários. O caso de Portugal. REICE: Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 19, 37–54. doi: 10.15366/reice2021.19.2.003

Steiger, A., Allemand, M., Robins, R., and Fend, H. (2019). Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118, 532–544. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000213

Syed, M., and McLean, K. (2018). “Erikson's theory of psychosocial development and career development” in Career development and counseling: putting theory and research to work. (New York: Wiley), 101–126.

Tomé, G., Gaspar, T., Matos, M. G., and Reis, M. (2019). Validation of the positive youth development scale (PYD-SF) for the Portuguese population. Revista de Psicologia da Criança e do Adolescente 10, 55–70. doi: 10.1234/rpca.2019.101

Tus, J. (2020). Self–concept, self–esteem, self–efficacy and academic performance of the senior high school students. Int. J. Res. Cult. Soc. 4, 45–59. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13174991.v1

Ungar, M. (2019). Change your world: the science of resilience and the true path to success. Toronto: Sutherland House.

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R., and Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 44, 1–31. doi: 10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

Vila, S., Gilar-Corbí, R., and Pozo-Rico, T. (2021). Effects of student training in social skills and emotional intelligence on the behaviour and coexistence of adolescents in the 21st century. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105498

Weissberg, R., Durlak, J., Domitrovich, C., and Gullotta, T. (2018). Social and emotional learning: past, present, and future. New York: Guilford Press.

Werner, E., and Smith, R. (1992). Overcoming the odds: high risk children from birth to adulthood. New York: Cornell University Press.

Wikman, C., Allodi, M., and Ferrer-Wreder, L. (2022). Self-concept, prosocial school behaviors, well-being, and academic skills in elementary school students: a whole-child perspective. Educ. Sci. 12, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/educsci12050298

Xia, Y., and Yang, Y. (2018). The influence of number of categories and threshold values on fit indices in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 53, 731–755. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1480346

Zhang, Z., Jiménez, F., and Cicala, J. (2020). Fear of missing out scale: a self-concept perspective. Psychol. Mark. 37, 1619–1634. doi: 10.1002/mar.21406

Zohar, A., Gilead, T., Barzilai, S., and Arcavi, A. (2024). Designing guiding principles for twenty-first century curricula: navigating knowledge, thinking skills, and pedagogical autonomy in the Israeli curriculum. Interchange 55, 93–113. doi: 10.1007/s10780-024-09515-0

Keywords: competency profile, professional schools, curricular autonomy, curricular flexibility, Portugal

Citation: Neves ML and Rodrigues R (2024) SER project: analysis of the skills profile of students from three Portuguese professional schools. Front. Educ. 9:1484872. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1484872

Edited by:

Amjad Islam Amjad, School Education Department, Punjab, PakistanReviewed by:

Elizabeth Ifeoma Anierobi, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, NigeriaMuhammad Mohsan Ishaque, University of Gujrat, Pakistan

Copyright © 2024 Neves and Rodrigues. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria de Lurdes Neves, bWFyaWEubmV2ZXNAaXNnLnB0

†ORCID: Lurdes Neves, orcid.org/0000-0002-1605-6848

Rosa Rodrigues, orcid.org/0000-0001-6548-418X

Maria de Lurdes Neves

Maria de Lurdes Neves Rosa Rodrigues

Rosa Rodrigues