- 1Department of Teaching, School Counseling, and Leadership Studies, Lewis and Clark College, Portland, OR, United States

- 2School of Education and Human Development, University of Colorado-Denver, Denver, CO, United States

Playful pedagogies, rooted in experiential learning, integrate play, humor, spontaneity, and levity to create engaging educational experiences. Playful pedagogies have been shown to support adults' emotional resilience and sense of belonging while reducing stress and anxiety. Despite these benefits, their use in education preparation programs (EPPs) remains underexplored. Given the increasing focus on teacher social and emotional learning (SEL), playful pedagogies hold significant potential for equipping future educators with the skills needed to foster both their own and their students' SEL growth. This paper advocates for a shift in teacher education from predominantly lecture-based instruction to a model that incorporates joy, humor, and experiential learning. We propose integrating playful pedagogies with a reflective learning cycle to enhance SEL competencies among pre-service teachers. Specifically, we introduce a conceptual model that combines a four-level pyramid of playful learning with an iterative reflection process. By integrating playful pedagogy into EPPs, we aim to foster resilience, creativity, and collaboration among future teachers, empowering them to create inclusive learning environments that nurture their students' holistic development.

Introduction

Playful pedagogies are situated within experiential learning, a broader framework emphasizing the importance of hands-on, applied experiences in the learning process. Playful pedagogies refer to the integration of play, humor, spontaneity, and levity into the learning experience, with the goal of creating an enjoyable and engaging environment for learners, offering a transformative approach to education (Forbes, 2021). By incorporating activities such as simulations, games, role-playing, and creative problem-solving and promoting levity and joy, playful pedagogies provide a holistic learning experience that transcends traditional boundaries (Forbes, 2021).

It is important to note that gamification, while related, is distinct from playful pedagogies. Gamification applies game-like elements—such as points, levels, and challenges—to non-game contexts to motivate and engage participants. Although gamification can be part of playful pedagogy, the core of playful pedagogies is centered on levity, humor, and joy, which are not essential components of gamification.

Playful pedagogies support wellbeing, resilience, and a sense of belonging (Brown, 2009) while reducing stress and anxiety (Forbes, 2021). Despite playful pedagogies' proven effectiveness in engaging K-12 students and increasing evidence of its benefits in adult education (Forbes, 2021; James and Nerantzi, 2019), its integration into EPPs remains underexplored (Shin, 2022). Given the growing emphasis on preparing teachers to address SEL (Hon et al., 2023; Schonert-Reichl, 2017; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2017), playful pedagogies hold untapped potential for equipping future educators with the skills needed to foster both their own and their students' social and emotional growth.

While the teaching profession emphasizes practical application, pre-service teacher education still predominantly relies on lectures as the primary mode of instruction (Jensen and Rørbæk, 2022). Recognizing this incongruence, we advocate for a paradigm shift in teacher education—one that prioritizes joy, humor, and experiential, student-centered approaches over traditional lecture methods to better support pre-service teachers' SEL. In this paper, we propose integrating playful pedagogies into teacher education by combining various forms of play with a reflective learning cycle as reflection is central to teacher preparation. Specifically, we introduce a conceptual model that connects a four-level pyramid of playful learning (Forbes and Thomas, 2022) with an iterative reflection process. The reflection cycle, adapted from Korthagen's work (Korthagen, 2017; Korthagen et al., 2001), provides a clear framework for educators to learn from their experiences and refine their abilities. Our model aims to support pre-service teachers' social and emotional competencies by integrating playful pedagogies with structured reflection. We also provide examples of how this model can be applied in teacher education classes. By incorporating playful pedagogy into teacher preparation, we argue that EPPs can foster a culture of resilience, joy, wellbeing, creativity, belonging, and collaboration among future teachers, empowering them to create vibrant, inclusive learning environments that nurture the holistic—cognitive, social, and emotional—development of their students.

Playful pedagogies: a potential pathway to wellbeing

Playful pedagogies in higher education: what they look like

Playful pedagogies are within the scope of applied, experiential approaches to learning (Jensen and Rørbæk, 2022), which actively engage learners and center on lived experiences that allow learners to observe, reflect, think, and act (Girvan et al., 2016). Playful pedagogies integrate elements of play—such as joy, humor, relaxation, freedom, and relief—into the learning experience where enjoyment is one of the primary goals. Effective play-based learning also often involves a teacher who embraces a playful attitude, incorporating joy, spontaneity, and humor into the learning process (Shin, 2022). In higher education, playful pedagogies use hands-on activities that combine joy and lightheartedness with active engagement and relevance, enabling learners to draw from their life experiences, interests, and curiosities. This makes the learning process both enjoyable and meaningful. Playful pedagogies promote experimentation, creativity, exploration, collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving (James and Nerantzi, 2019; Zosh et al., 2018). Because play often involves exaggeration and stepping outside everyday norms, playful learning invites the use of new tools and methods, encourages reimagining of concepts where students learn with and from one another. Throughout the process, students are encouraged to refine their approach to activities or content, deepening their learning (James and Nerantzi, 2019). Playful approaches to learning include but are not limited to simulations, role-playing, storytelling, and creative problem-solving exercises. Playful pedagogies also involve unstructured free time for students to play (Leather et al., 2021) where they have the agency to choose their kind of play.

Through their four-level pyramid of play, Forbes and Thomas (2022) illustrate that there are several pathways to engage higher education students in playful pedagogies (see Figure 1). Notably, educators have the autonomy to choose the level or levels that fit their goals and comfort levels. The first level, the base of the pyramid, is playfulness, which is necessary and at the heart of playful pedagogies (Forbes and Thomas, 2022). It involves the instructor being playful, and not taking themselves too seriously even while engaging students in serious learning. In Professors at Play (Forbes and Thomas, 2022), Sharon Peck, one of the contributors, emphasizes that many professors frequently use playfulness in their teaching but do not necessarily report about it: “For many of us, playfulness is a part of us in the same way that teaching is part and parcel of who we are” (Peck, 2022, p. 21). The power of professor playfulness is that it reduces unnecessary hierarchy and fear and increases emotional safety in the classroom. For example, an instructor could make the syllabus less formal and more playful or present themselves as a playful person (Forbes, 2021). The second level involves “connection-formers,” activities whose sole purpose is to get people to laugh, find levity, have fun, enjoy each other's company, and connect. These opening activities may or may not be connected to class content because the purpose is to establish relational safety- a precursor for learning. The third level of the pyramid is “play to teach content” which refers to utilizing play as a tool or medium to teach course content. Play to teach content could consist of adding an element of surprise, levity, competition, or gamifying a lesson (Forbes, 2021; also see Forbes and Thomas, 2022 for more examples). The last, highest, and most challenging part of the pyramid is “whole course-design.” Designing an entire course around a theme of play requires the most time and creativity to develop because it involves a sophisticated and integrated course based on play (Forbes and Thomas, 2022). In summary, educators can choose the forms and pathways to playful pedagogy that they see fit, because regardless of the approach, the core of play lies in its benefits to wellbeing and thriving.

Figure 1. The pyramid of play (Forbes and Thomas, 2022, p. 16).

Playful pedagogies in teacher education: a pathway to wellbeing?

Although empirical studies on the benefits of integrating playful pedagogies into higher education classes are limited, several studies have shed light on the relationship between playfulness, play, and social and emotional wellbeing and competence. For instance, Chang et al. (2013) showed that young adults who were more playful experienced more positive emotions, offsetting the negative effects of psychological stress. Similarly, Magnuson and Barnett (2013) found that playful college students reported lower levels of perceived stress. They were more likely to employ adaptive, stressor-focused coping strategies and less likely to turn to negative, avoidant, or escape-oriented strategies, suggesting a positive connection between playfulness and resilience. Hart and Holmes (2022) further examined the link between playfulness and emotional intelligence, finding that playful behaviors in adults may enhance their abilities to manage, express, and regulate their emotions—all components of emotional intelligence. Moreover, Brown's (2009) extensive research on play found positive connections between play and a renewed sense of optimism, belonging, productivity, and adaptability. Simply put, play energizes and renews us, improving our mood; it is a catalyst that affects our wellbeing (Brown, 2009; Dierenfeld, 2024).

After reviewing the perks of play and playfulness for adults, Leather et al. (2021) argued for playful pedagogies in higher education as a pathway to promote play and playfulness, emphasizing that they become part of a planned cycle of learning activities. Forbes (2021), in one of the few studies that have explicitly examined the benefits of adopting a playful pedagogy in post-secondary education, found that students identified several advantages to playful pedagogies. For example, counseling students enrolled in the author's classes found the learning environment lively, engaging, and authentic (Forbes, 2021). They also found that the playful approach to teaching and use of playful pedagogies promoted their wellbeing, reducing stress, anxiety, and fear. Particularly, participants expressed that “play melted away their stress” (p. 65) which facilitated their readiness to learn and to better connect and be receptive to difficult content. In other words, this playful approach supported students' emotional regulation. They reported feelings of belonging and warmth. The playful approach to learning helped them be more vulnerable, empathic, and authentic with their peers, which all enhance motivation and enjoyment of learning (Forbes, 2021). The benefits of play in a field as emotionally demanding as counseling have significant implications for emotional resilience. Pre-service teachers are another group that could benefit from playful pedagogies especially given the stressors of teaching.

Educator preparation programs (EPPs) are responsible for equipping future PreK-12 teachers with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to effectively teach and support diverse learners. They also aim to develop pre-service teachers' social and emotional competencies, which are crucial for creating supportive, inclusive learning environments and fostering teacher resilience. Foundational knowledge in educational theory, pedagogy, and subject content, along with practical application, student teaching, and reflective practice, are all essential components of teacher preparation. However, a significant incongruence persists within EPPs: the emphasis on theory often outweighs practical application, despite the inherently practical nature of the teaching profession. Lectures and theoretical instruction still dominate EPPs as the primary mode of instruction (Jensen and Rørbæk, 2022). Therefore, it is not surprising that very few studies have examined the positive effects of play on teachers and pre-service teachers. One exception is a recent study (Jensen and Rørbæk, 2022) with Danish pre-service teachers which corroborated the role of play in the enjoyment of learning. Jensen and Rørbæk (2022) examined the experiences of Danish pre-service teachers with playful learning-based teaching and found that pre-service teachers who experienced playful qualities in their learning reported higher levels of happiness and feelings of readiness. In another study (Shin, 2022) that used playful pedagogies with early childhood pre-service teachers, participants reported that their learning experience was “extremely fun,” bringing back fun childhood memories. Shin (2022) argued that learning about play theoretically does not fully equip pre-service teachers with the skills to apply playful pedagogies. This point was vividly illustrated by a participant who revealed that they found experiencing playful pedagogy valuable because they did not see the value of play in learning until they experienced it in their class; they experienced firsthand how “play can provoke learning” (p. 13). Experiencing play also helped pre-service teachers feel more confident in their abilities and better equipped with the tools they needed to utilize play in teaching children (Shin, 2022). Lastly, a recent study (Dierenfeld, 2024) found that teachers used play to reframe stressors, restore balance, and renew joy, thereby enhancing resilience and job satisfaction. Taken together, these studies compel us to wonder why do not EPPs infuse the joys and benefits of play and utilize playful pedagogies in preparing teachers, specifically to cultivate their social and emotional competencies? This question is particularly timely given the increased emphasis on preparing teachers who are prepared to infuse SEL in their teaching (Hon et al., 2023). After all, it seems that a playful approach to teaching and learning can naturally create the environment and conditions for cultivating teacher SEL.

Teacher social and emotional competencies

Interest in SEL has surged in recent years and extant research solidly shows its benefits, particularly for students within K-12 educational settings (Durlak et al., 2011; Hawkins et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2017). SEL involves the process by which individuals acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for cultivating healthy self-identities, managing emotions, achieving personal and collective objectives, demonstrating empathy toward others, nurturing supportive relationships, and making conscientious and compassionate decisions (https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/). Specifically, SEL focuses on five main competencies:

1. Self-awareness: Involves identifying one's emotions and thoughts, and understanding their impact on behavior. This includes acknowledging personal strengths and challenges, as well as being conscious of one's goals and values. High self-awareness involves understanding the link between thoughts, feelings, and actions.

2. Self-management: Involves regulating emotions, thoughts, and actions, including managing stress, controlling impulses, self-motivation, and pursuing personal and academic objectives. It also covers managing oneself in social settings.

3. Social awareness: Involves understanding others' perspectives, empathizing with people from diverse backgrounds and cultures, including social and ethical norms, and identifying support systems within one's environment.

4. Relationships skills: Includes providing one with the tools to establish and sustain positive relationships, communicate effectively, listen well, collaborate, resolve conflicts constructively, solve problems together efficiently, and give and receive assistance as necessary.

5. Responsible Decision-making: Involves enabling others to make thoughtful and respectful choices regarding their behavior and social interactions, considering safety, ethics, social norms, consequences, and the wellbeing of themselves and others (Oberle and Schonert-Reichl, 2017).

Although SEL initially focused on children and youth in K-12 schools, in recent years, calls for strengthening social and emotional competencies in adults, as well, have emerged (e.g., Jagers et al., 2019). EPPs were particularly encouraged to support the SEC of pre-service teachers (Jagers et al., 2019; Schonert-Reichl, 2017; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2017). This is not surprising because teachers are the “engine that drives” student SEL (Schonert-Reichl, 2017). In particular, Schonert-Reichl (2017) identified that three dimensions are key for SEL to be systemic-all driven by cultivating the five SEL competencies in teachers: (1) SEL and emotional resilience of teachers, (2) SEL of students, and (3) the learning environment. Playful pedagogies offer an ideal context for all three dimensions.

SEL of teachers

Pre-service teachers face unique challenges in developing their social and emotional competencies. The demands of their EPPs, coupled with anxieties about classroom readiness, can create emotional stressors that impede social and emotional growth. Additionally, teaching is widely recognized as one of the most stressful professions within the human service sector with close to 50% leaving the profession within the first 5 years (Sims and Jerrim, 2020). One potential solution is cultivating the social and emotional competencies of teachers which can offset the chronic stresses of teaching (Hon et al., 2023; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Katz et al., 2020) and support their wellbeing and emotional resilience. Given that the level of preparation by EPPs affects turnover among beginning teachers (Flushman et al., 2021), they are uniquely positioned to provide pre-service teachers with the foundations they need to support their own social and emotional competencies, a key dimension to systemic SEL. Unfortunately, pre-service teachers' SEL and wellbeing during preparation have not received much attention in EPPs (Corcoran and O'Flaherty, 2022; Schonert-Reichl, 2017). In the US, a national scan (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2017) of EPPs revealed that pre-service teachers receive very few opportunities to learn about emotional awareness and management, which are both critical for teacher wellbeing and resilience skills. Similarly, another study (Corcoran and O'Flaherty, 2022) which examined the growth trajectories of 305 Irish pre-service teachers' perceptions of psychological wellbeing during their four years of teacher preparation, reported a lack of approaches that taught pre-service teachers skills related to emotional competence and wellbeing.

SEL of students

Given that they are role models as well as architects of learning opportunities, teachers' social and emotional competencies benefit student SEL in various ways. First, by embodying social and emotional skills through their interactions, teachers model to students how SEL competencies can be applied effectively and consistently (Oberle and Schonert-Reichl, 2017). Second, teacher pedagogical practices that support student autonomy, voice, and mastery as well as perspective-taking, collaboration, and cooperation promote students' SEL (Greenberg et al., 2017). Third, students gain from learning opportunities that intentionally allow them to practice, refine, and apply SEL skills (Greenberg et al., 2017). SEL programs have traditionally provided a context for students to develop social and emotional skills, but approaches like playful pedagogies may offer a more meaningful integration. One critique of SEL programs is the assumption that SEL is separate from academic learning, prompting calls for greater integration with content (Elias, 2019; Jones and Bouffard, 2012). Playful pedagogies address this by combining SEL development with the academic curriculum. The key is for teachers to clearly identify the academic objectives of playful learning activities, along with the specific SEL components they aim to develop.

The learning context

The classroom environment is the third and last key dimension of systemic SEL. Teachers set the tone and climate of their classrooms. Teachers who show high social and emotional competence recognize the effects of their emotions and behaviors on the climate and tone of the classroom. When teachers struggle with their social and emotional skills, their classrooms tend to have more conflict and feel less warm, inclusive, and engaging (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). In contrast, teacher warmth and emotional awareness competencies have been associated with supportive teacher-student relationships and a positive classroom climate, enabling students to engage with their learning, explore, and take learning risks (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Pianta et al., 2002). In fact, one meta-analysis of more than 100 studies (Marzano, 2003) reported that teachers who formed positive relationships with their students had 31% fewer behavior problems during the school year than teachers who did not. Playfulness in the classroom sets the tone of the learning environment giving students and teachers the opportunity to enjoy each other's company and engage more deeply in their learning (Forbes, 2021).

Recent studies suggest that preparing teachers who are SEL-ready is gaining attention in EPPs. Experts argue that only promoting teachers' knowledge of SEL is not enough (Hon et al., 2023). In addition to foundational knowledge and a deep understanding of SEL, pre-service teachers need support in developing their personal social and emotional skills in areas such as self-awareness and positionality. They also need to grow their ability to create positive and supportive learning environments and hone their abilities in cultivating student SEL (Hon et al., 2023). Against this backdrop, lectures and readings on SEL, while necessary, do not suffice because they do not offer embodied, genuine opportunities for pre-service teachers to practice, develop, and refine their SEC. Playful pedagogies provide the context for pre-service teachers to practice and develop social and emotional skills and apply these skills with children and youth in their own classrooms while also experiencing humor, levity, and joy. To put it simply, firsthand experience can help pre-service teachers see the value of play in fostering SEL rather than speculate about its role. However, not all experiences result in learning (Dewey, 1938). Therefore, to be intentional about fostering teacher SEL through playful pedagogies, an iterative learning cycle that involves observing, reflecting, thinking, and acting is a necessary part of the process.

The teacher learning cycle

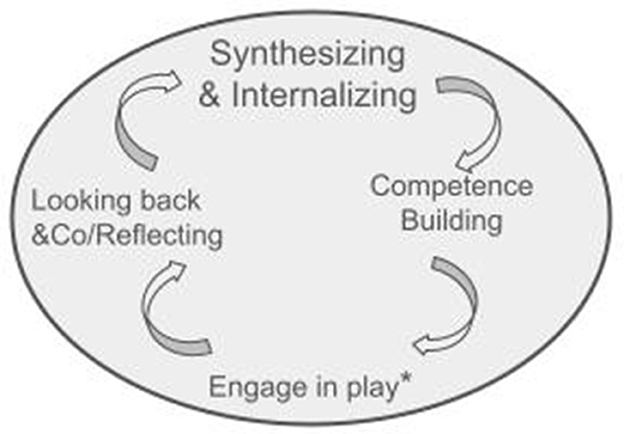

Playful pedagogies fall within the domain of experiential learning (Jensen and Rørbæk, 2022), which emphasizes the role of experience in building and creating knowledge. A robust body of research (e.g., Girvan et al., 2016; Korthagen, 2017) recognizes the fundamental role of involving pre-service professionals as active participants in their own learning, promoted through applied approaches and reflection (Jensen and Rørbæk, 2022). However, guidelines on how to reflect can be ambiguous (Korthagen, 2017). This process must be intentional and explicit, as reflective activities are essential for helping pre-service teachers understand their actions, their sources, and how to improve their practice (Avalos, 1998). Reflection is not just a routine, superficial exercise; rather, it is foundational to teacher learning (Korthagen, 2017). Therefore, reflection is important when considering the use of playful pedagogies to support teacher learning in general, and teacher SEL in particular. With this in mind, our learning cycle is adapted from Korthagen et al.'s (2001) Action–Looking back–Awareness–Creating alternatives–Trial (ALACT) model of reflection to aid pre-service teachers' meaning-making process. Specifically, a main goal is for them to consider how the playful approaches they engage in can support their SEL development. Korthagen et al. (2001) contend that the reflection process must be structured and must consist of the dimensions of thinking, feeling, wanting, and acting. So, Korthagen et al.'s (2001) model does not only focus on the cognitive, but also the affective, and motivational aspects—what teachers want and need—of teacher learning and gaining competencies. They also argue that context shapes these dimensions (see Figure 2). Together these factors are vital for cultivating teacher SEL.

Our teacher reflective learning process includes four phases:

Phase 1-Engage in play: Involves pre-service teachers actively engaging with the playful learning experience in their EPP classroom.

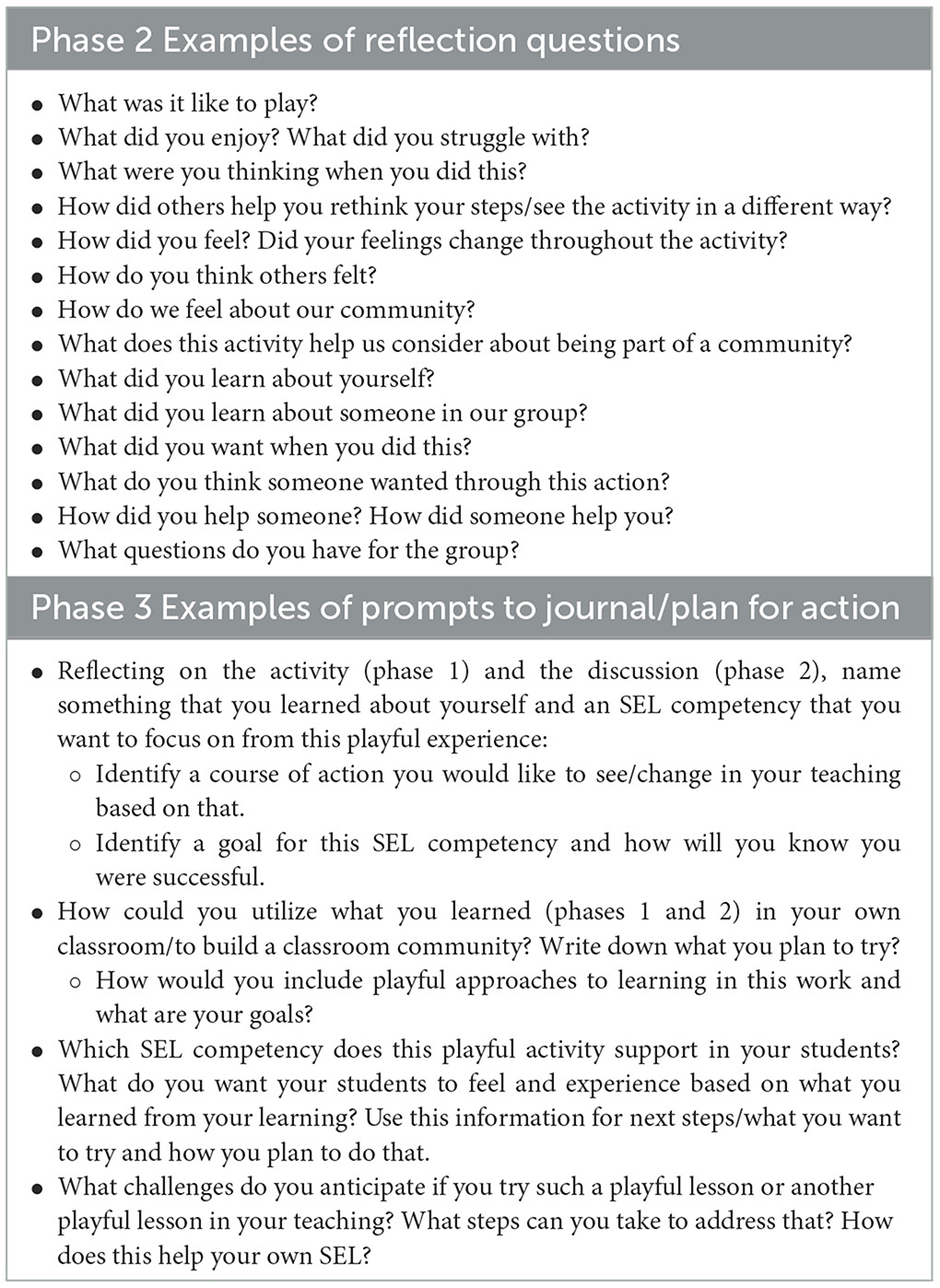

Phase 2-Looking back and co/reflecting: Involves the pre-service teachers reflecting and looking back on the playful activity, what happened and how they acted and felt and what motivated their actions. This process includes pre-service teachers reflecting on their own and with their classmates. The teacher educator raises a few questions to structure the process and get pre-service teachers to consider the cognitive, affective and motivational aspects of pre-service teachers' engagement with the activity and using the five SEL competencies to frame the questions.

Phase 3-Synthesizing and internalizing: This step involves pre-service teachers building awareness of their own SEL competencies and identifying/planning next steps in their teaching. They do this by using what they learned about their social and emotional competencies through engaging in playful pedagogy and analyzing the factors that influence their actions and thoughts as they come up with plans for action. This process is personal. It also involves considering how they can apply playful pedagogies in their own teaching-thinking how they can integrate playful pedagogies and SEL into teaching the curriculum. By providing prompts, teacher educators help to concretize the process (see Table 1). To ensure continuity and engagement, we advise that pre-service teachers share their plans with teacher educators, supervisors, and cooperating teachers at their placement.

Phase 4-Competence building: In this phase, pre-service teachers actively develop their SEL competencies by applying the SEL competencies they are learning as well as using playful pedagogies (it is encouraged they utilize them) in their teaching. This is an opportunity for them to explore their social and emotional competency development and how a playful approach impacts their teaching and growth. This is where they can bring together SEL and playful learning to teach the curriculum. Phase 3's plan guides this stage. Pre-service teachers provide evidence of growth by documenting actions taken and reflecting on how these actions influence their thoughts, emotions, and motivations. They demonstrate their evolving practice. Practicum supervisors and cooperating teachers can support this process by providing feedback during practicum placements. Additionally, videotaping lessons for feedback in EPP classes can further support competence building.

A playful model to cultivate pre-service teachers' SEL

The playful model emphasizes cultivating teacher SEL through playful pedagogies, highlighting the joy, levity, and creativity that play can bring to education. The aim is for educators to experience these benefits firsthand, incorporate playful pedagogies into their teaching, and foster the development of pre-service teachers' social and emotional competencies. The model (Figure 3) integrates Forbes and Thomas's (2022) pyramid of play with the teacher learning cycle adapted from Korthagen et al. (2001) to enhance the five SEL competencies. Play serves as the learning context, while the teacher learning cycle provides a structured mechanism for developing and deepening these competencies. Strengthening SEL skills -the five SEL competencies- through play at their EPPs equips pre-service teachers with the tools to create a supportive, joyful, engaging learning environment in their own classrooms. Specifically, the model aims to help pre-service teachers (1) create a supportive learning environment that can also foster playful pedagogies for K-12 students, (2) support student SEL, and (3) enhance their own SEL, wellbeing, and resilience as educators-the three dimensions of SEL identified by Schonert-Reichl (2017). These three dimensions are depicted by the circle on the right side of Figure 3.

Figure 3. The playful model for cultivating pre-service teacher SEL: the model includes (left to right) The pyramid of play (Forbes and Thomas, 2022); The playful teacher learning cycle (adapted from Korthagen et al., 2001); CASEL's 5 SEL competencies; the three dimensions of SEL (Schonert-Reichl, 2017).

After engaging in playful experiences, pre-service teachers are guided to reflect on these experiences and to identify the SEL skills involved. During the reflection phase, they are encouraged to first reflect independently, and then engage in group discussions with their peers. Reflection questions (see Table 1) can serve as a guide, but educators should tailor them to align with their specific goals and students' needs, including SEL goals. It is recommended to keep the number of reflection questions concise to allow for deep reflection. Providing opportunities for pre-service teachers to raise their own questions is fundamental, as is creating space for them to share any hesitations about SEL and using playful pedagogies in their teaching. In the phase 3, pre-service teachers outline actionable steps they want to take, allowing them to translate reflection into practice. Therefore, it is important that teacher educators guide pre-service teachers through this phase by offering prompts that support their thinking about next steps and their reasons for them. Finally, the last phase involves applying their new learning and monitoring their SEL growth over time. Support and feedback from the teacher educator, peers, supervisors and cooperating teachers contributes to pre-service teachers finetuning their abilities.

Integrating the playful pyramid with the teacher learning cycle offers three key advantages. First, the playful pyramid provides educators with multiple entry points into play, highlighting that the use of play is not rigid or linear. Instead, it suggests that playful pedagogies can be implemented in a variety of ways in the classroom. Teacher educators can choose the level of play that aligns best with their goals and the needs of their pre-service teachers. This flexibility is crucial, as teachers' autonomy, goals, sense of efficacy, and specific needs are critical factors in ensuring that any strategy is both adopted and sustained (Reeve et al., 2022). Second, the teacher learning cycle emphasizes the value of structured reflection as an integral part of teacher development (Korthagen, 2017). By embedding reflective practices, the cycle helps pre-service teachers gain deeper insights into their teaching and adapt their approaches effectively. Third, a common critique of SEL is that it is often treated as separate from the core curriculum. Our model addresses this issue by proposing playful pedagogies as a way to teach academic content while simultaneously developing SEL competencies. In this integrated approach, SEL and content learning are intertwined, rather than treated as distinct areas, with play providing an enjoyable, lighthearted, and engaging context for learning. Next, we explore examples of how this framework can be applied.

Application of the playful model in teacher education

In this section, we spotlight two different learning activities to engage pre-service teachers in playful pedagogies and cultivate their own SEL competencies. One activity is at the connection former level of the pyramid and the other provides an example of play to teach content.

Connection formers: what do you meme to laugh and connect

The playful pedagogies pyramid includes connection formers, which consist of activities that bring levity and humor to a classroom. They can be related or unrelated to the content and often utilized to build community, trust, and connection in the classroom, all key to student learning and engagement. Memes are one type of connection formers. They build community through laughter, humor. For example, What Do You Meme-Family—with a twist—is a connection former that pre-service teachers can use after a few months of being together in a cohort. The class can be divided into three-four teams for this activity. Each team picks a meme-able photo from the stack and they have to show it to the other groups before the other groups come up with a meme caption that is related to their cohort, members in their cohort, or their experience as a pre-service. The team in the judge role collects each group's caption out loud to everyone, they take a few minutes to deliberate and share their vote on the funniest meme caption. This activity provides participants with an opportunity to share stories, reflect on their experiences, offer perspectives, and make observations about each other—all within a playful context. It encourages students to express their perspectives in a playful way and allows them to laugh together, appreciate and bond over their shared journey. After the activity, phase 2 in the reflection circle contributes to connecting the learning experience to SEL. This activity could support the SEL competencies: self-awareness, social awareness and relationship skills. Some examples of reflection questions that are specific to the activity include:

Self-awareness:

• How did a particular caption reflect your own experiences and emotions as part of this cohort?

• Did you find any of the memes or captions particularly relatable? Why?

• What do you need to have in place to facilitate such an activity in your own class? What would you want your student to take away from it?

Social awareness:

• What did you learn about the perspectives or experiences of others through this activity?

• Did anyone's caption surprise you or change how you think about someone's experience in the cohort?

Relationships skills:

• How did this activity help you connect with others in the group?

• Did you have to negotiate or collaborate with others during the caption creation process? How did that go?

• How did humor and playfulness help us connect as a group, and how could we bring these elements into our future teaching?

Afterwards, pre-service teachers work individually on phase 3 with the teacher educator utilizing prompts to guide their action plans. For example, the teacher educator could use one of these three prompts: (1) Based on what you learned about yourself, identify one change you would like to make in your teaching practice to better support your SEL growth. What is your course of action for implementing this change? What should I be looking for if I am in your classroom? (2) What specific playful activities could you use to foster relationship skills such as collaboration and communication in your classroom? Write down what you plan to implement and your goals for doing so. (3) Based on your reflections, what challenges do you anticipate if you try a playful lesson in your teaching practice? What specific steps can you take to address these challenges?

Phase 4 involves pre-service teachers carrying out their competence building plan and evaluating their growth. Connecting elements of this playful activity to SEL competencies contributes to all three dimensions of SEL: creating a supportive learning environment, enhancing teacher SEL, and offering a way to model and engage students in their own SEL development and demonstrate how play could be included in the classroom. The laughter and exchange of recollections on events deepens the sense of community. Teacher wellbeing is further supported through humor and connection. The reflection cycle provides a structured yet dynamic approach to developing SEL competencies in pre-service teachers. Each phase targets the SEL competencies of interest by encouraging participants to engage emotionally, reflect deeply, internalize insights, and apply their learning. This iterative cycle ensures that SEL is not just theoretical but is actively practiced and reinforced.

Play to teach content: paper airplanes for different types of discussion

Second to the top of the pyramid of play is play to teach content. At this level, the teacher educator uses playful approaches as a means to teach their course content. Hence, it is an opportunity to model to pre-service teachers how playful learning can be used to combine curricular content with SEL. In paper airplanes, students write responses to a prompt on a piece of paper, fold it into a paper airplane, and throw it toward the instructor. Pre-service teachers are invited to test their airplanes to see how far they can go before throwing them. The instructor then reads the responses, maintaining student anonymity and sparking further discussion. This activity can be used to explore content, such as assigned readings, or reflections on aspects of their practicum. Several components of SEL can be examined in phase 2 of the reflection cycle. Although several are outlined here, we advise that teacher educators only use a few and align them with their goals to allow for in-depth reflection. Below are examples for questions that address self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness:

Self-awareness:

• What emotions did you notice during the paper airplane activity? Why?

• How did you feel about sharing your response anonymously? Did anonymity make it easier or harder for you to express yourself?

Self-management:

• Were there any moments during the activity when you felt stressed or unsure? How did you handle those feelings?

• When was the last time you made a paper airplane and tried to fly it? How did you manage your reactions if your airplane didn't go as far as you wanted or if something did not go the way you wanted it to?

• How can you use what you learned about managing your emotions and behavior during this activity in future teaching situations?

Social awareness:

• What did you notice about your peers' reactions during the activity? How might their responses reflect different perspectives or experiences?

• How do you think the playful aspect of this activity affected your classmates' willingness to participate?

Phase 3 could involve pre-service teachers devising a plan for their classrooms. For instance, a teacher educator could ask them one of the following questions: (1) What steps would you take to ensure that every student feels comfortable participating in an activity like this? Consider how you might support different SEL needs, such as encouraging self-awareness or managing anxiety. How would you adjust the activity to achieve these goals? (2) How can you adapt this paper airplane activity to teach a specific piece of content in your future classroom, while also fostering SEL competencies like social awareness or relationship skills? Describe the content you would teach and how you would modify the activity to address both learning and SEL goals, (3) Identify a goal for integrating playful activities like this into your teaching practice. How will you know if your students are successfully learning the intended content and developing SEL skills such as collaboration?

Phase 4 entails pre-service teachers carrying out their competence building plan and evaluating their growth. This step could involve the supervisor, mentor teacher or EPP faculty observing the activity and offering the pre-service teacher feedback on their development. This playful activity creates a space for empathy and reciprocal vulnerability, nurturing several aspects of SEL and supporting trust in the classroom.

Discussion

Recommendations for EPPs

The integration of playful pedagogies and a focus on cultivating pre-service teachers' social and emotional competencies hold several important imply several recommendations for EPPs, encouraging them to:

• Consider shifting toward experiential, playful, and reflective approaches: This holistic model emphasizes active learning, addressing both the cognitive and social-emotional aspects crucial for pre-service teachers and their future students.

• Prioritize pre-service teacher social and emotional competency development: EPPs need to make the development of pre-service teachers' self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making a central focus, not just an afterthought. Explicitly integrating SEL-building activities and reflective practices into coursework and field experiences is essential.

• Model playful, SEL-enhancing practices: Teacher educators should model the very playful pedagogies and SEL-enhancing practices they hope their pre-service teachers will adopt. Experiencing this firsthand allows pre-service teachers to understand the value and impact of such approaches.

• Provide guidance on implementing playful pedagogies: EPPs should equip pre-service teachers with practical tools and a clear framework for incorporating playful learning activities into their classrooms. This includes not only the 'how-to' of playful techniques but also the rationale behind them—specifically, how these approaches foster student SEL.

• Foster a culture of playfulness and wellbeing: EPPs should strive to create a learning environment imbued with a spirit of playfulness, levity, and concern for the wellbeing of all members of the community. This models the type of vibrant, inclusive, and supportive climate pre-service teachers should aim to cultivate in their own classrooms.

• Find ways for pre-service teachers to monitor their growth: Phase 4 in the teacher learning cycle is expected to take place in practicum, outside the EPP course work. Therefore, there should be in place concrete pathways that ensure that pre-service teachers are practicing, monitoring, and evaluating their SEL skill development and comfort in including play in teaching. Video recordings are one way to do that. Another way is including mentor teachers and supervisors, as we highlight next.

• Collaborate with mentor teachers and supervisors: EPPs should work closely with mentor teachers and supervisors in the field to ensure a consistent, seamless approach to supporting pre-service teachers' SEL development. Observations, feedback, and joint reflections can reinforce the importance of these competencies.

Conclusion and future directions

Although scholars have long advocated for SEL training for teachers (Hon et al., 2023; Jones and Bouffard, 2012; Katz et al., 2020; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2017), several large-scale surveys indicate that many teachers feel inadequately prepared to manage the social and emotional demands of teaching. Few teachers enter the field with formal SEL training as part of their teacher education programs (Hamilton and Doss, 2020; Hon et al., 2024). Pre-service teachers also frequently report a gap between their learning in EPP classrooms and their experiences in K-12 settings, often noting that EPPs emphasize theory over practical experience (Ketter and Stoffel, 2008). Playful pedagogies, a form of experiential learning, offer an opportunity for pre-service teachers to practice skills while embracing play, humor, and levity. Our proposed model combines playful pedagogies with an SEL-focused reflection cycle to support the cultivation of SEL for pre-service teachers. Furthermore, given that only about half of in-service teachers believe they are effective in helping students develop strong social and emotional skills, and even fewer feel equipped with effective strategies for supporting students who struggle in this area (Schwartz, 2019), we would be remiss if we did not note that our proposed model can also benefit teachers who have been in the profession for years as well. Professional development that involves applying the model and providing in-service teachers with feedback and guidance throughout the process could help them develop their own SEL competencies and practical, engaging strategies for integrating SEL into their classrooms.

While this manuscript presents a promising approach for integrating playful pedagogies into teacher preparation to cultivate pre-service teachers' social-emotional competencies, further research is needed to empirically validate the effectiveness of the proposed model. It is also worthwhile to examine the application of the model with in-service teachers. Future studies should explore the implementation of this framework in diverse education contexts (teacher education and in-service professional development) and investigate the long-term impacts on teachers' wellbeing, resilience, and ability to foster SEL in their own classrooms. This could be an exciting direction for higher education, particularly for teacher preparation, given the growing emphasis on teacher SEL and resilience.

It is also important to examine and understand the factors that prevent educators from using playful pedagogies to support pre-service teacher SEL in EPPs. Also, because pre-service teachers might start their careers in schools where playful pedagogies and SEL might not be supported, it is also important to help them find the pathways that work for them. For example, a new teacher who cannot teach content through play could find ways of using playfulness and/or connection formers to cultivate SEL.

Our proposed model offers a pathway to integrate playful pedagogies with the teacher learning cycle to enhance teacher SEL competencies. While further research is needed to test this model, it presents a promising approach for actively engaging pre-service teachers in their learning, providing them with both pedagogical skills and SEL competencies. This is a pathway that may be worth exploring because, “Play is our brain's favorite way of learning” (Diane Ackerman, n.d.)

Author contributions

LD: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the publication of this article. LD was supported by Lewis & Clark Graduate School funds. DD was supported by UC-Denver Departmental PD funds.

Acknowledgments

ChatGPT4o, developed by OpenAI, was used to edit certain sentences for clarity and flow.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Avalos, B. (1998). School-based teacher development the experience of teacher professional groups in secondary schools in Chile. Teach. Teach. Educ. 14, 257–271. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(97)00040-1

Brown, S. L. (2009). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. London: Penguin.

Chang, P. J., Qian, X., and Yarnal, C. (2013). Using playfulness to cope with psychological stress: taking into account both positive and negative emotions. Int. J. Play 2, 273–296. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2013.855414

Corcoran, R. P., and O'Flaherty, J. (2022). Social and emotional learning in teacher preparation: pre-service teacher well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 110:103563. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103563

Dierenfeld, C. M. (2024). Unlocking fun: accessing play to enhance secondary teachers' well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 142:104523. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104523

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Elias, M. J. (2019). What if the doors of every schoolhouse opened to social-emotional learning tomorrow: reflections on how to feasibly scale up high-quality SEL. Educ. Psychol. 54, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1636655

Flushman, T., Guise, M., and Hegg, S. (2021). Partnership to support the social and emotional learning of teachers. Teach. Educ. Q. 48, 80–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103278

Forbes, L. K. (2021). The process of play in learning in higher education: a phenomenological study. J. Teach. Learn. 15, 57–73. doi: 10.22329/jtl.v15i1.6515

Forbes, L. K., and Thomas, L. D. (Eds.). (2022). Professors at Play Playbook. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University - ETC Press.

Girvan, C., Conneely, C., and Tangney, B. (2016). Extending experiential learning in teacher professional development. Teac. Teach. Educ. 58, 129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.04.009

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., and Durlak, J. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. Future Child. 27, 13–32. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0001

Hamilton, L. S., and Doss, C. J. (2020). Supports for social and emotional learning in American schools and classrooms. Arlington, VA: Rand Corporation. doi: 10.7249/RRA397-1

Hart, T., and Holmes, R. M. (2022). Exploring the connection between adult playfulness and emotional intelligence. J. Play Adulthood 4, 28–51. doi: 10.5920/jpa.973

Hawkins, J. D., Kosterman, R., Catalano, R. F., Hill, K. G., and Abbott, R. D. (2008). Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 162, 1133–1141. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1133

Hon, D., Rush, K., Darwich, L., Sauve, J., and O'Neil, L. V. (2024). Oregon's journey creating social and emotional learning standards for educator preparation programs. Soc. Emot. Learn. Res. Pract. Policy 4:100054. doi: 10.1016/j.sel.2024.100054

Hon, D., Sauve, J. A., Mahfouz, J., and Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2023). “Social and emotional learning in pre-service teacher education programs,“ in Social and Emotional Learning in Action: Creating Systemic Change in Schools, eds. S. Rimm-Kauffman, M. J. Strambler, and K. A. Schonert-Reichl (New York, NY: Guildford Publication), 115–137.

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., and Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educ. Psychol. 54, 162–184. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

James, A., and Nerantzi, C. (2019). The Power of Play in Higher Education: Creativity in Tertiary Learning. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-95780-7

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Jensen, H., and Rørbæk, L. L. (2022). Smoothing the path to practice: playful learning raises study happiness and confidence in future roles among student teachers and student ECE teachers. Stud. Educ. Eval. 74:101156. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2022.101156

Jones, S. M., and Bouffard, S. M. (2012). Social and emotional learning in schools: from programs to strategies and commentaries. Soc. Policy Rep. 26, 1–33. doi: 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2012.tb00073.x

Katz, D., Mahfouz, J., and Romas, S. (2020). Creating a foundation of well-being for teachers and students starts with SEL curriculum in teacher education programs. Northwest J. Teach. Educ. 15:5. doi: 10.15760/nwjte.2020.15.2.5

Ketter, J., and Stoffel, B. (2008). Getting real: exploring the perceived disconnect between education theory and practice in teacher education. Stud. Teach. Educ. 4, 129–142. doi: 10.1080/17425960802433611

Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: towards professional development 3.0. Teach. Teach. 23, 387–405. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

Korthagen, F. A., Kessels, J., Koster, B., Lagerwerf, B., and Wubbels, T. (2001). Linking Practice and Theory: The Pedagogy of Realistic Teacher Education. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781410600523

Leather, M., Harper, N., and Obee, P. (2021). A pedagogy of play: reasons to be playful in postsecondary education. J. Exp. Educ. 44, 208–226. doi: 10.1177/1053825920959684

Magnuson, C. D., and Barnett, L. A. (2013). The playful advantage: how playfulness enhances coping with stress. Leis. Sci. 35, 129–144. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2013.761905

Marzano, R. J. (2003). What Works in Schools: Translating Research into Action. Arlington, VA: ACSD.

Oberle, E., and Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). “Social and emotional learning: recent research and practical strategies for promoting children's social and emotional competence in schools,” in Handbook of Social Behavior and Skills in Children, ed. J. Matson (Cham: Springer), 175–197. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-64592-6_11

Peck, S. (2022). “Focus on: playful perspective,” in Professors at Play Playbook, eds. L. Forbes and D. Thomas (Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University - ETC Press), 21–23.

Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., Payne, C., Cox, M. J., and Bradley, R. (2002). The relation of kindergarten classroom environment to teacher, family, and school characteristics and child outcomes. Elem. Sch. J. 102, 225–238. doi: 10.1086/499701

Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., Cheon, S. H., Matos, L., and Kaplan, H. (2022). Supporting Students' Motivation: Strategies for Success. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003091738

Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. Future Child. 27, 137–155. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0007

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Kitil, M. J., and Hanson-Peterson, J. (2017). To reach the students, teach the teachers: A national scan of teacher preparation and social and emotional learning. A report prepared for the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia.

Schwartz, S. (2019). Teachers support social-emotional learning, but say students in distress strain their skills. Educ. Week 38, 12–13.

Shin, M. (2022). Reclaiming playful learning: exploring the perceptions of playful learning among early childhood preservice teachers. Asia-Pac. J. Res. Early Child. Educ. 16, 1–22. doi: 10.17206/apjrece.2022.16.3.1

Sims, S., and Jerrim, J. (2020). TALIS 2018: Teacher working conditions, turnover and attrition. Statistical working paper. London: UK Department for Education.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., and Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: a meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Dev. 88, 1156–1171. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12864

Keywords: pre-service teachers, education preparation programs, social and emotional learning, playful pedagogies, teacher SEL, teacher reflection, classroom climate

Citation: Darwich L, DeBay D, Forbes L and Mahfouz J (2025) Play, reflect, cultivate social and emotional learning: a pathway to pre-service teacher SEL through playful pedagogies. Front. Educ. 9:1478541. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1478541

Received: 10 August 2024; Accepted: 03 December 2024;

Published: 08 January 2025.

Edited by:

Benjamin Dreer-Goethe, University of Erfurt, GermanyReviewed by:

Simona Sava, West University of Timişoara, RomaniaAmanda Lopes, University of Massachusetts Boston, United States

Copyright © 2025 Darwich, DeBay, Forbes and Mahfouz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lina Darwich, bGRhcndpY2hAbGNsYXJrLmVkdQ==

Lina Darwich

Lina Darwich Dennis DeBay

Dennis DeBay Lisa Forbes

Lisa Forbes Julia Mahfouz

Julia Mahfouz