- The Self-Development Skills Department, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

This study investigates the impact of shared leadership (SL) on the various dimensions of organizational commitment (OC) within Saudi higher education institutions (HEIs). Employing a descriptive cross-sectional survey design, data were collected from faculty members at a prominent Saudi university using structured questionnaires. The questionnaires included validated scales for SL, encompassing dimensions such as Development and Mentoring, Problem-Solving, Support and Consideration, and Planning and Organizing, as well as for OC, which measured affective, normative, and continuance commitment. Descriptive statistics, correlation, and regression analyses were used to assess the relationships between SL and OC components. The findings indicate that shared leadership is widely practiced, with Development and Mentoring emerging as the most prominent SL dimension. A significant positive relationship was identified between SL and all three OC components, with affective commitment demonstrating the strongest correlation. Additionally, SL was found to significantly predict overall OC, underscoring its role in enhancing faculty commitment. These results highlight the potential of adopting shared leadership practices in HEIs to strengthen faculty engagement and institutional performance. Future research should expand data collection across multiple institutions and examine the combined influence of SL and OC on the quality of education and institutional success.

Introduction

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are pivotal in developing human capital, contributing to societal and economic advancement in today’s knowledge-driven economy. The complexity of modern academic environments demands adaptive and collaborative leadership approaches, making traditional hierarchical models less effective for addressing the dynamic challenges faced by HEIs (Avolio et al., 2009; Pearce and Conger, 2002). Recent research promotes a shift toward Shared Leadership (SL), a model where leadership responsibilities are distributed across multiple members rather than concentrated in a single figure of authority (Zhu et al., 2018). SL emphasizes collaboration, shared authority, and collective decision-making, aligning well with the interdisciplinary and collaborative nature of HEIs, where diverse expertise and perspectives drive innovation and organizational success (Avolio et al., 1996; Ensley et al., 2006; Mehra et al., 2006).

Despite these potential advantages, leadership within HEIs often remains centralized, which can limit an institution’s responsiveness and capacity to thrive in a competitive environment (Hoch, 2013; Wang et al., 2014). SL, as a collaborative model, has shown promise in enhancing team dynamics, facilitating decision-making, and increasing morale among team members (Hoch and Kozlowski, 2014; Drescher et al., 2014). It is particularly effective in complex settings where no single individual holds all the expertise needed for optimal decision-making (Pearce and Herbik, 2004; Wang et al., 2014). Nonetheless, there is limited research on SL’s application within HEIs, particularly in non-Western contexts like Saudi Arabia (Aboramadan et al., 2020; Koeslag-Kreunen et al., 2020).

A critical factor in HEIs’ success is fostering organizational commitment (OC) among faculty members. OC, representing an employee’s attachment, obligation, and engagement with their institution, significantly impacts job performance, retention, and organizational effectiveness (Meyer and Allen, 1991). Comprising three dimensions—affective commitment (emotional attachment), normative commitment (sense of obligation), and continuance commitment (awareness of costs associated with leaving)—OC is positively associated with job satisfaction, low turnover, and improved performance (Allen and Meyer, 1996; Pudjowati et al., 2022).

Research underscores the influence of leadership styles on OC. For example, Afsar et al. (2019) found that inclusive leadership styles foster higher levels of affective and normative commitment by creating a sense of belonging among employees. In contrast, traditional top-down approaches tend to restrict engagement and reduce emotional investment (Nguyen and Pham, 2020). SL, with its focus on shared responsibility, shows promise in fostering OC within HEIs, promoting mutual support among faculty members (Drescher et al., 2014; Pearce and Sims, 2002). Yet, there remains a dearth of research on the SL-OC relationship within Saudi HEIs, where hierarchical structures are the norm (Alsubaie, 2021; Alsaeedi and Male, 2013).

Research purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine the impact of shared leadership (SL) on organizational commitment (OC) within Saudi higher education institutions (HEIs). Specifically, it seeks to:

1. Assess the extent of shared leadership practices within Saudi HEIs.

2. Analyze the relationship between shared leadership and the dimensions of organizational commitment (affective, normative, and continuance commitment).

3. Identify which shared leadership domains most significantly predict organizational commitment.

4. Explore variations in shared leadership and organizational commitment based on demographic factors, such as gender, faculty rank, and years of experience.

Research hypotheses

Based on the research questions and literature, the following hypotheses are proposed:

• H1: Shared leadership practices are positively associated with organizational commitment dimensions (affective, normative, and continuance commitment).

• H2: The Development and Mentoring domain of shared leadership is the most significant predictor of organizational commitment among faculty members.

• H3: Variations in shared leadership and organizational commitment scores exist according to gender, faculty rank, and years of experience.

Research significance

This study contributes to both theoretical and practical understandings of shared leadership (SL) and organizational commitment (OC) in non-Western HEIs, with particular focus on Saudi Arabia. Theoretically, it addresses the underexplored SL-OC relationship in higher education, expanding the literature on leadership in culturally unique contexts. Practically, the findings can aid HEI administrators in designing SL-focused leadership development initiatives that foster faculty commitment and enhance institutional performance.

In sum, this study aims to bridge a notable research gap on SL and OC within Saudi HEIs, offering valuable insights that can improve leadership practices and strengthen organizational outcomes in higher education.

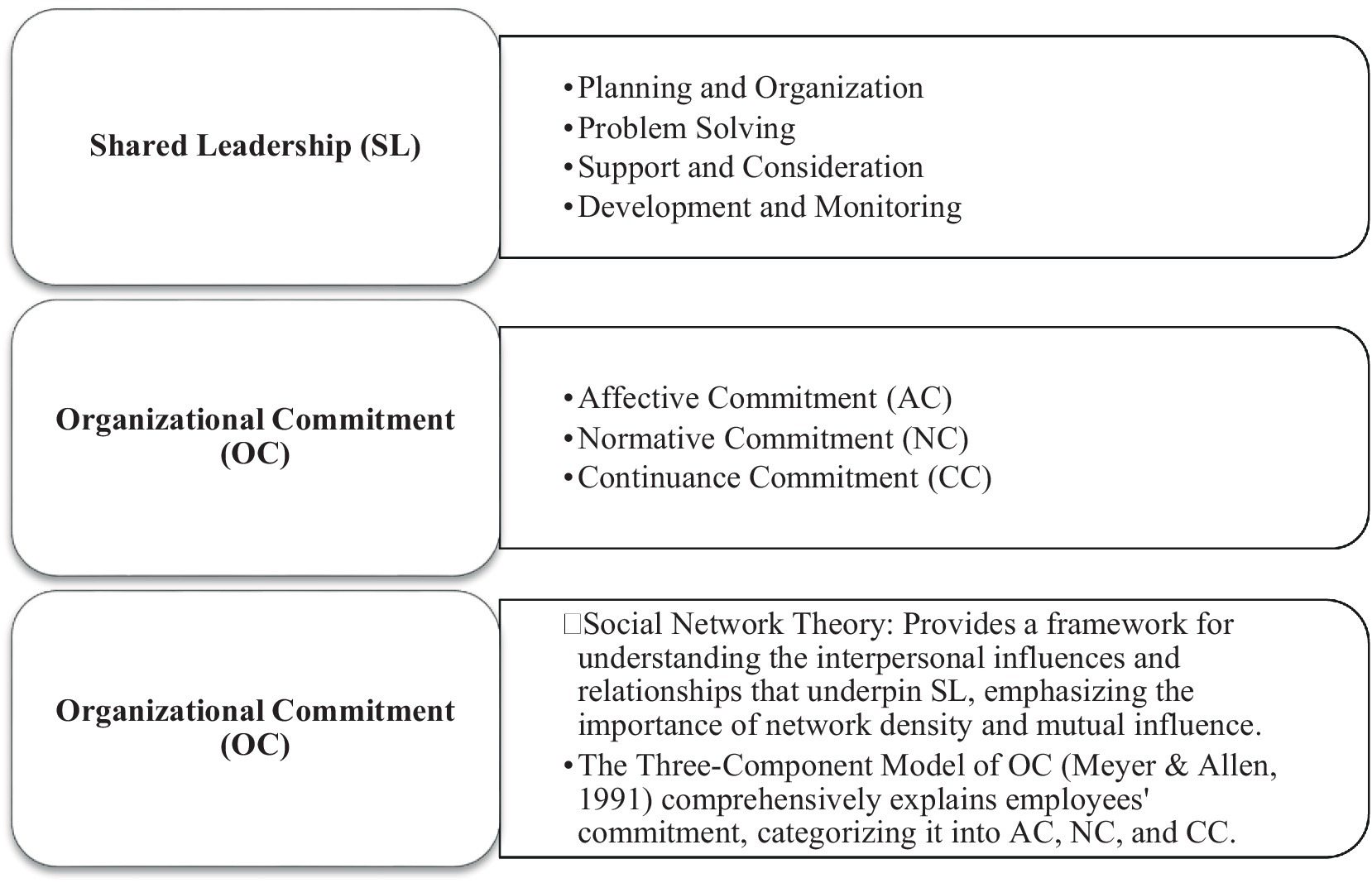

Conceptual framework

This study’s conceptual framework investigates the impact of shared leadership (SL) on organizational commitment (OC) within the context of Saudi higher education institutions (HEIs). This framework outlines the key components of SL and OC, their interrelationships, and the guiding theories and empirical findings.

Components of the conceptual framework

1 Shared Leadership (SL)

o Planning and Organization: Engages faculty in decision-making processes, fostering a sense of ownership and commitment.

o Problem Solving: Involves collaborative efforts to address challenges and ensure quality assurance within HEIs.

o Support and Consideration: Reflects mutual influence and interpersonal relationships among group members, creating a supportive environment.

o Development and Monitoring: Includes continuous professional development, mentoring, and feedback mechanisms to support faculty growth and distributed leadership.

2 Organizational Commitment (OC)

o Affective Commitment (AC): Emotional attachment and identification with the institution, driven by positive leadership experiences.

o Normative Commitment (NC): Sense of obligation and responsibility toward the institution, influenced by social norms and organizational values.

o Continuance Commitment (CC): Perceived costs of leaving the institution, influenced by personal investments and lack of alternatives.

Theoretical basis

• Social Network Theory: Provides a framework for understanding the interpersonal influences and relationships that underpin SL, emphasizing the importance of network density and mutual influence.

• The Three-Component Model of OC (Meyer and Allen, 1991) comprehensively explains employees’ commitment, categorizing it into AC, NC, and CC.

Hypothesized relationships

1. SL and AC: Higher levels of SL practices (planning and organization, problem-solving, support, and consideration, development, and monitoring) positively influence faculty members’ emotional attachment to the institution (AC).

2. SL and NC: SL practices enhance faculty members’ sense of obligation and responsibility toward the institution (NC).

3. SL and CC: SL practices impact the perceived costs of leaving the institution (CC), although this relationship may be less strong than that between AC and NC.

Visual representation

The visual representation of this conceptual framework is depicted below, illustrating the hypothesized relationships between the components of shared leadership (SL) and organizational commitment (OC).

This diagram highlights how the different components of SL (planning and organization, problem-solving, support and consideration, development, and monitoring) interact with the components of OC (affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment), providing a structured basis for empirical investigation in the context of Saudi HEIs.

Literature review

Shared leadership (SL) has emerged as a significant paradigm in organizational studies, challenging traditional hierarchical leadership models. SL is defined as a dynamic and interactive influence process among group individuals who aim to lead one another toward achieving group or organizational goals (Pearce and Conger, 2002). This approach aligns with academic institutions’ collaborative and complex nature, where diverse expertise and perspectives are essential.

Shared leadership (SL)

SL refers to a condition of reciprocal influence that occurs when team members interact, significantly enhancing team and organizational performance. It influences many team members’ outcomes by distributing leadership roles as a characteristic of an emerging team (Bolden et al., 2009). Gibb first proposed distributed and targeted team leadership (Carson et al., 2007), later used by Claudet (2012) to promote positive school leadership collaboration and solve real-world problems in educational institutions. When a single person is in charge, it is called focused leadership; when two or more people share the roles, duties, and tasks of leadership, it is called dispersed leadership.

SL distributes leadership responsibilities, influence, and decision-making across a team or organization. It envisions the leadership mantle moving among the group members, emerging spontaneously in the group’s dynamics. SL is nurtured when a formal leader creates a culture of openness, trust, respect for all members, and a willingness to share power and responsibility. Effective shared leadership comprises four important dimensions: planning and organization, problem-solving, support and consideration, and development and monitoring.

Planning and organization

Teachers’ engagement in decision-making processes is closely linked to organizational commitment (OC). According to Graham (1996), a teacher’s active involvement in shaping school culture is critical for fostering commitment. However, some studies have not found a direct connection between democratic decision-making and OC, suggesting that the impact of participatory decision-making on OC can vary depending on the context (Millward and Timperley, 2010). Several key characteristics influence this relationship, including the teacher’s authority, the administration’s sincerity, the acceptance of changes among teachers, the inclusiveness of the participation process, the genuine influence teachers have, and the outcomes of decision-making procedures (Amtu et al., 2021).

Problem-solving

Due to globalization, public demands for the quality of higher education institutions have become more tangible and pressing. Higher education institutions are now accountable for delivering quality assurance to the community. This accountability is significant because the quality of higher education is defined by the level of compatibility between institutions and established standards (Akbari et al., 2016). An internal quality assurance system is one effective method to ensure that higher education requirements are met. Universities implement this system systematically to manage and uphold education quality standards (Lo et al., 2010).

Leadership teams in higher education can be characterized by two main dimensions: rational-technical and cultural-process-oriented (Akdemir and Ayik, 2017). The rational-technical dimension includes codified norms, procedures, functions, task specialization, and hierarchy. In contrast, the cultural-process-oriented dimension emphasizes cohesion, beliefs, informal and individual connections, engagement, togetherness, and shared ideals (Bolden and Petrov, 2014). Group cohesion strengthens organizational commitment (OC), and role clarity is positively linked to OC (Pahi et al., 2020; Balthazard et al., 2004; Bergman et al., 2012).

Effective problem-solving within shared leadership involves sociable leaders who address difficulties quickly, empower teachers to participate, and closely supervise daily practices (Hulpia and Devos, 2010). However, Koeslag-Kreunen et al. (2018) found that most school leadership behaviors involve sharing ideas without engaging in constructive confrontations or co-construction. This finding indicates that an individual’s perception of a task and the role of shared leadership are crucial in motivating teachers to seek out disagreement and co-create new knowledge (Wahlstrom and Louis, 2008; Almutairi, 2020).

Support and consideration

SL is a social activity involving relationships among group members to achieve a common goal. Social network theory offers a framework for investigating interpersonal influences on group members. The effect of leadership is exercised through these relationships and assumes the presence of followers or influences. SL establishes forms of mutual influence that strengthen and deepen existing team connections. Thus, social network theory is relevant as it investigates ways of interacting individually with others (Wu and Chen, 2018). The increasing shared influence in groups can be understood through leadership networks aligning with social network theory (Wasserman and Faust, 1994).

A leadership network is a pattern of team members who rely on one another for leadership. The density of these networks intensifies as dependence on one another for leadership develops. In social network research, density is a crucial feature describing the overall degree of different exchanges among group members (Baker-Shelley et al., 2017). The greater the network density, the more relationships each group member has with other members. When one group member perceives another as exercising leadership influence, links between group members form (Babalola, 2016). Consequently, density focuses on the average number of leadership-related ties (Han et al., 2018). Network density measures the proportion of total possible linkages in each network (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). Multiple leaders’ social contact is crucial to achieving distributed leadership success (Clugston et al., 2000).

Open communication—defined as a work environment where people feel satisfied exchanging ideas, experiences, and information within a group—promotes organizational commitment (OC) (Kok and McDonald, 2017). Good communication within the school improves the workplace environment and strengthens OC (Choi et al., 2018).

Development and monitoring

In today’s schools, leadership is no longer primarily the responsibility of the school administrator; instead, it is a collective function where other members with explicitly designated leadership positions assist in running the school (Choi et al., 2018). Assistant principals can serve as formal leaders, while faculty leaders with official leadership positions but no hierarchical power over other instructors are responsible for mentoring colleagues, coordinating curriculum activities, providing professional support, and playing a leadership role.

A school administrator’s leadership characteristics significantly impact teacher and student achievement (Uluöz and Yağci, 2018). Positive and supportive leadership behaviors from school administrators foster a productive and motivated educational environment, enhancing both teacher and student performance. Conversely, problematic behaviors from school administrators can jeopardize staff and student achievements, negatively affecting their commitment to the organization (D'Innocenzo et al., 2021).

Effective development and monitoring within a shared leadership framework involve continuous professional development, regular feedback, and support systems that enable teachers to grow and excel. This collaborative approach to leadership ensures that leadership responsibilities are distributed and all members are engaged in the school improvement process, fostering a culture of continuous development and high organizational commitment.

Organizational commitment (OC)

The three-component model of organizational commitment (OC), proposed by Meyer and Allen (1991), is one of the most empirically tested models in organizational studies. Meyer and Allen assert that OC consists of three distinct mindsets: affective commitment (AC), normative commitment (NC), and continuance commitment (CC). These three components together offer a comprehensive explanation of employees’ commitment to their organizations.

Affective commitment (AC)

Affective commitment focuses on a faculty member’s emotional attachment to the institution where they work. AC is an employee’s desire to invest emotionally in the organization (Vandenberghe et al., 2017). It involves the employee’s psychological attachment, identification with, and participation in the organization. Employees remain in the organization because they want to. AC is a psychological attachment that develops from identifying with a goal, and it can be aimed at constituencies such as organizations or supervisors. It has received significant scholarly attention among commitment components because it is linked to crucial organizational outcomes (Breitsohl and Ruhle, 2013). AC is strongly linked to the transformational leadership style, whereas CC has a modest relationship (Alsiewi, 2016; Ndlovu et al., 2018). In contrast, AC has no relationship with NC. The perceived shared leadership style also influences employees’ OC, suggesting that the impact of leadership style varies depending on the institution and situation (Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016).

Normative commitment (NC)

Normative commitment focuses on participants’ sense of responsibility toward the institutions in which they work. NC is an obligatory commitment where employees stay with a company because they feel responsible and compelled to do so (Alsiewi, 2016). NC emphasizes the requirement to continue working at one’s current organization due to the pressure and guilt associated with adhering to social norms. Workers with strong NC perceive working at their organization as their duty, driven by their values and ideologies. NC also focuses on a person’s desire to remain at a company due to tasks, work duties, dedication, or morale (Khan et al., 2021). Individual culture and work ethics usually support this type of commitment, making one wish to stay at their institution. Unlike the other two types of commitment, NC is not related to an organization’s purpose or mission but to the values that personnel uphold. NC in universities also centers on a faculty’s perceived duty to stay at their institution out of a sense of responsibility (Amtu et al., 2021).

Continuance commitment (CC)

Continuance commitment (CC) refers to an employee’s perception of the costs associated with leaving an institution (Meyer et al., 2015). Employees decide to stay by weighing the expense of leaving against the advantages of staying. This form of commitment is based on the employee’s potential costs of leaving the company and the perceived lack of other job prospects. Also known as calculative commitment, CC involves evaluating how beneficial it is to remain at an organization long-term (Hussein and da Costa, 2008).

CC focuses on two main points:

1. Security and Investment: An individual may choose to stay because they have secured a senior position, developed specialized expertise and local affiliations, or have family bonds that necessitate financial stability and continuity. Leaving the organization would require significant financial sacrifice.

2. Lack of Alternatives: An individual may feel compelled to stay due to a perceived lack of other viable work options (Aboramadan et al., 2020).

Meyer and Allen (1991) defined CC as the result of two factors:

• Investment: The volume and quality of investments, or “side bets,” that individuals have made in their current position.

• Alternatives: The perceived absence of suitable alternatives elsewhere.

Individuals often invest considerable time and effort in developing specialized skills within an organization, enhancing their earning potential and benefits by staying with the company. CC is thus the outcome of an employee’s decision to remain because of the personal resources already invested and the potential costs of changing jobs (Meyer et al., 2015).

As a result, those who have heavily invested in their organizations are less likely to leave. According to Meyer and Allen (1991), an individual’s commitment is influenced by their perception of career opportunities outside the organization. Unlike affective commitment (AC), which is rooted in emotional attachment, CC is based on a cost–benefit analysis of leaving versus staying.

In teaching, for example, some individuals remain committed despite significant stress and responsibilities. The profession’s challenges may attract those seeking a demanding career, further reinforcing their commitment (D'Innocenzo et al., 2021).

Methodology

To meet the purpose of this survey study, a cross-sectional design was employed. A cross-sectional survey design is a type of research in which researchers collect data from a sample population at a single point in time (Connelly, 2016).

Sample characteristics

The study took place at one of the largest government universities in Saudi Arabia, which has approximately 4,000 faculty members across 22 colleges and management offices. The survey was circulated electronically via email to faculty members. Utilizing QuestionPro, an online survey platform, we gathered responses from 496 faculty members, representing 12.4 percent of the total faculty population. The participants were randomly selected, and there were no cases of incomplete surveys.

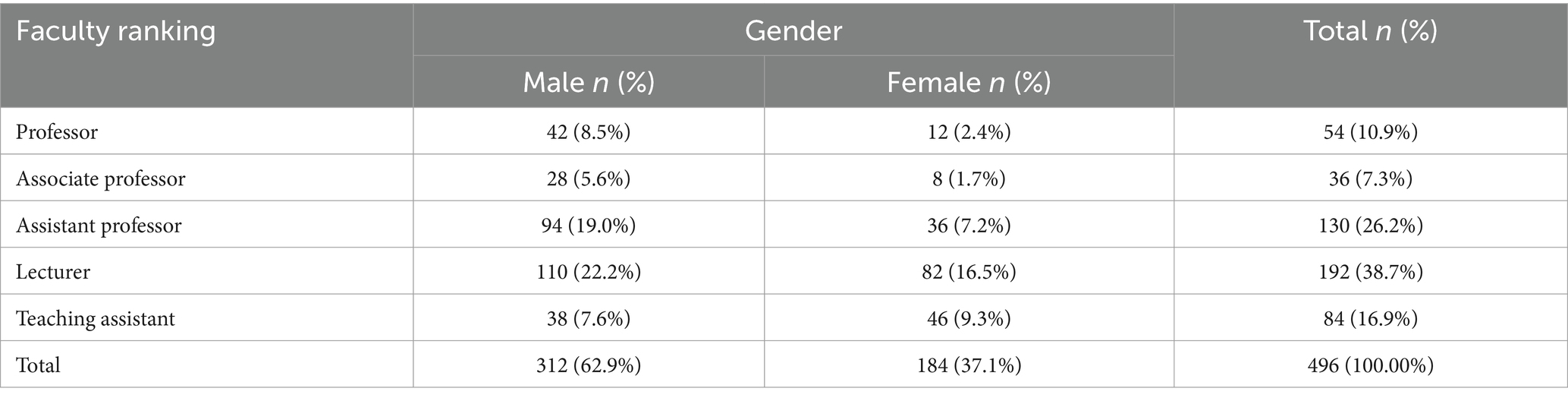

The respondents included both genders and served at different faculty ranks, including teaching assistant, lecturer, assistant professor, associate professor, and full professor. Most respondents were lecturers (38.7 percent), followed by assistant professors (26.2 percent). The distribution of faculty ranking by gender is outlined in Table 1 below. Additional demographic information such as age, type of settlement (urban or rural), financial situation, marital status, and parents’ education could provide further insights into the sample characteristics.

Procedure

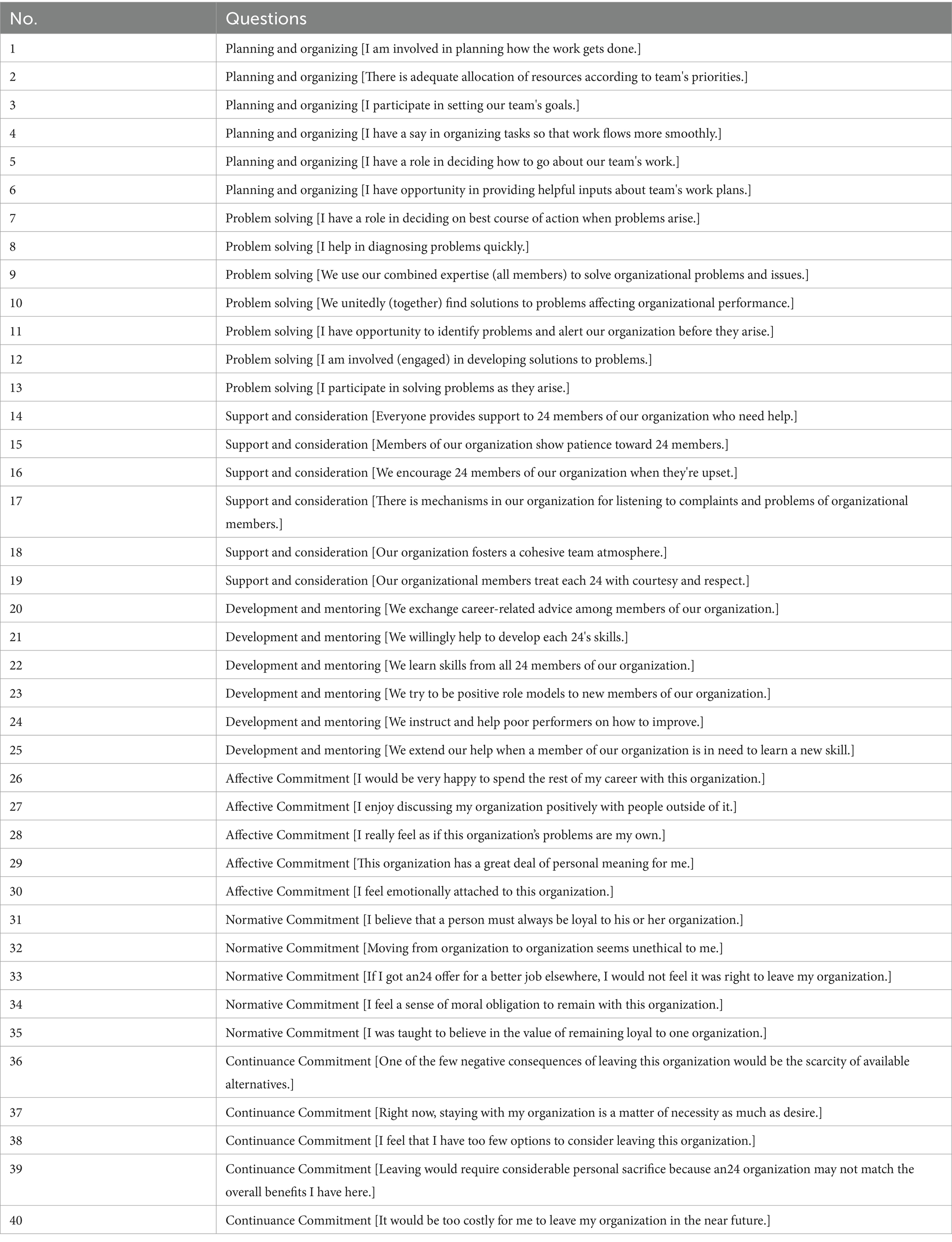

Data for this study were acquired through a structured survey questionnaire comprising 48 items. This questionnaire recorded demographic information such as gender, faculty rank, experience level, and nationality, and it included two primary scales: (1) the shared leadership scale and (2) the organizational commitment scale.

Shared leadership scale

Shared leadership involves the distribution of influence among team members, significantly enhancing team and organizational performance. We adopted the dimensions of effective shared leadership (SL) as recommended by Hiller et al. (2006), Carson et al. (2007), Mihalache et al. (2014), and Fausing et al. (2015). The dimensions include:

• Planning and Organizing

• Problem-Solving

• Support and Consideration

• Development and Mentoring

A total of 25 items focused on these SL dimensions were formatted on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example items include: “I participate in setting our team’s goals” and “We use our combined expertise to solve organizational problems” (see Appendix A for a complete list of items).

Organizational commitment scale

Organizational commitment (OC) indicates a team member’s level of engagement with the organization’s goals and the bond they share with their organization. The OC scale focused on three dimensions of OC in higher education, as recommended by Clugston et al. (2000):

• Affective Commitment (AC): Emotional attachment to the organization.

• Normative Commitment (NC): Sense of moral obligation to remain with the organization.

• Continuance Commitment (CC): Awareness of the costs of leaving the organization.

The items within the OC scale were also formatted on a 7-point Likert scale. Examples include: “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” and “I feel emotionally attached to this organization” (see Appendix A for a complete list of items). A similar methodology has been used by several other researchers such as Wayoi et al. (2021), Alamri and Al-Duhaim (2017), Trivellas and Santouridis (2016), and Morrow (2011).

To ensure the validity and reliability of the scales included in the survey questionnaire, we consulted with experts to validate the items and pilot-tested the questionnaire with a small group of faculty members. The Cronbach alpha coefficient was calculated to assess internal consistency, yielding values of 0.84 for the SL scale and 0.79 for the OC scale, indicating good reliability.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis for this study was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 26). This choice of software was appropriate given the study’s design and the closed-ended nature of the questionnaire.

Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize the data, including frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations. These measures provided an overview of the demographic characteristics of the respondents and the distribution of scores on the shared leadership and organizational commitment scales.

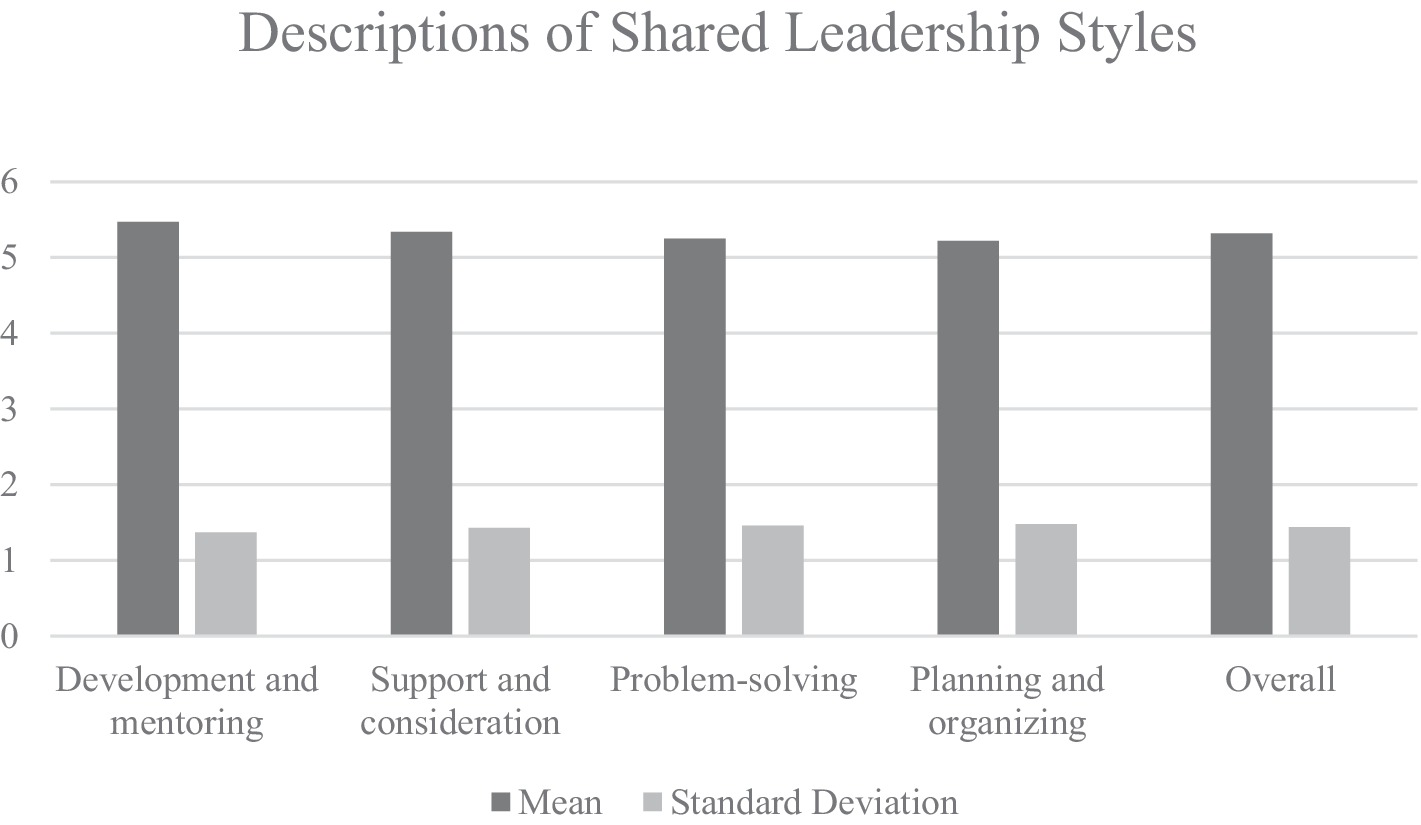

Before conducting inferential analyses, normality tests were performed to assess the distribution of the data. The Shapiro–Wilk test was utilized to evaluate normality, with results indicating whether the data followed a normal distribution. Based on the outcomes of these tests, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was employed to assess the relationships between shared leadership and organizational commitment, as it assumes that the data are normally distributed. Additionally, linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the predictive power of shared leadership on organizational commitment. Statistical significance for all inferential tests was set at p < 0.05, ensuring that any observed relationships were unlikely to have occurred by chance (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework illustrating the impact of shared leadership on organizational commitment in Saudi higher education institutions.

Figure 2. Descriptions of shared leadership styles. A 7-point Likert scale was used to measure participants’ responses, so the overall score for participants could range from 1.0 to 7.0.

Results

This study primarily examined the effect of shared leadership on organizational commitment within Saudi higher education institutions. The main results of the present study are presented below, organized by the research question.

Practice of shared leadership in Saudi higher education

The results of the first research question, which aimed to determine the prevalence of the shared leadership style in Saudi universities and the dimensions that are most commonly practiced, were encouraging. The participants’ overall score for shared leadership was positive, with a mean value of 5.32 (SD = 1.44), indicating a promising potential for shared leadership in Saudi higher education.

An examination of specific dimensions of shared leadership revealed that Development and Mentoring (M = 5.47, SD = 1.37) was the most practiced dimension, followed by Support and Consideration (M = 5.34, SD = 1.43). Planning and Organizing were the least practiced among the four dimensions of shared leadership, which include Development and Mentoring, Support and Consideration, Problem-solving, and Planning and Organizing.

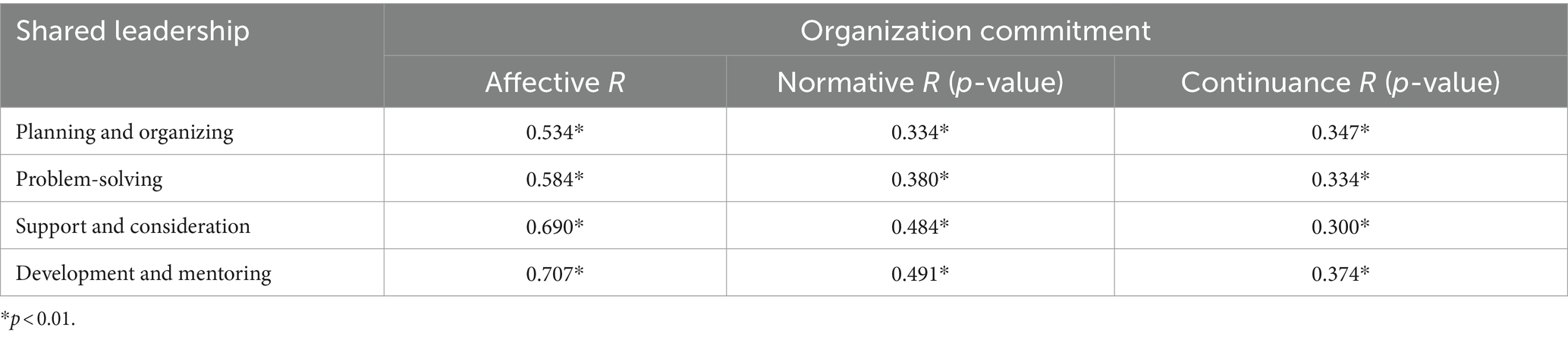

Descriptions of organizational commitment

Figure 3 shows how the dimensions of the OC scale are perceived. The results demonstrate that AC is the best measure for OC, with a mean score of 5.66 and a standard deviation of 1.43. This is followed by NC, with a mean score of 4.97 and a standard deviation of 1.43. AC, NC, and CC are good measures for OC with mean scores above the average.

Figure 3. Descriptions of organizational commitment. A 7-point Likert scale was used to measure participants’ responses. Therefore, the overall score for participants could range from 1.0 to 7.0.

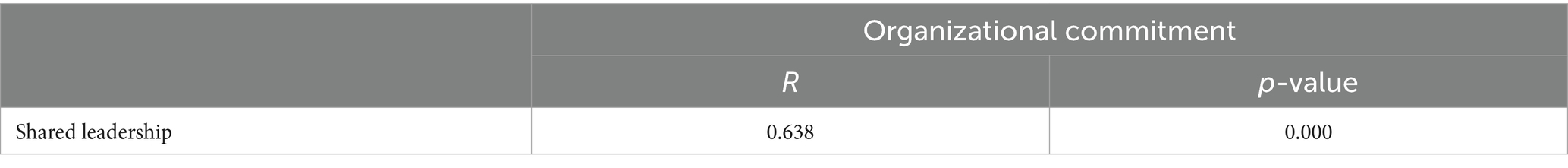

Correlation of shared leadership with organizational commitment

The second research question of the present study examined the correlation between shared leadership (SL) and organizational commitment. We conducted a Pearson’s correlation analysis to address this question. The results of the analysis indicated that SL has a significant relationship with OC at the university with a correlation coefficient of 0.638, p < 0.05. Table 2 illustrates the extent of the relationship between SL and OC.

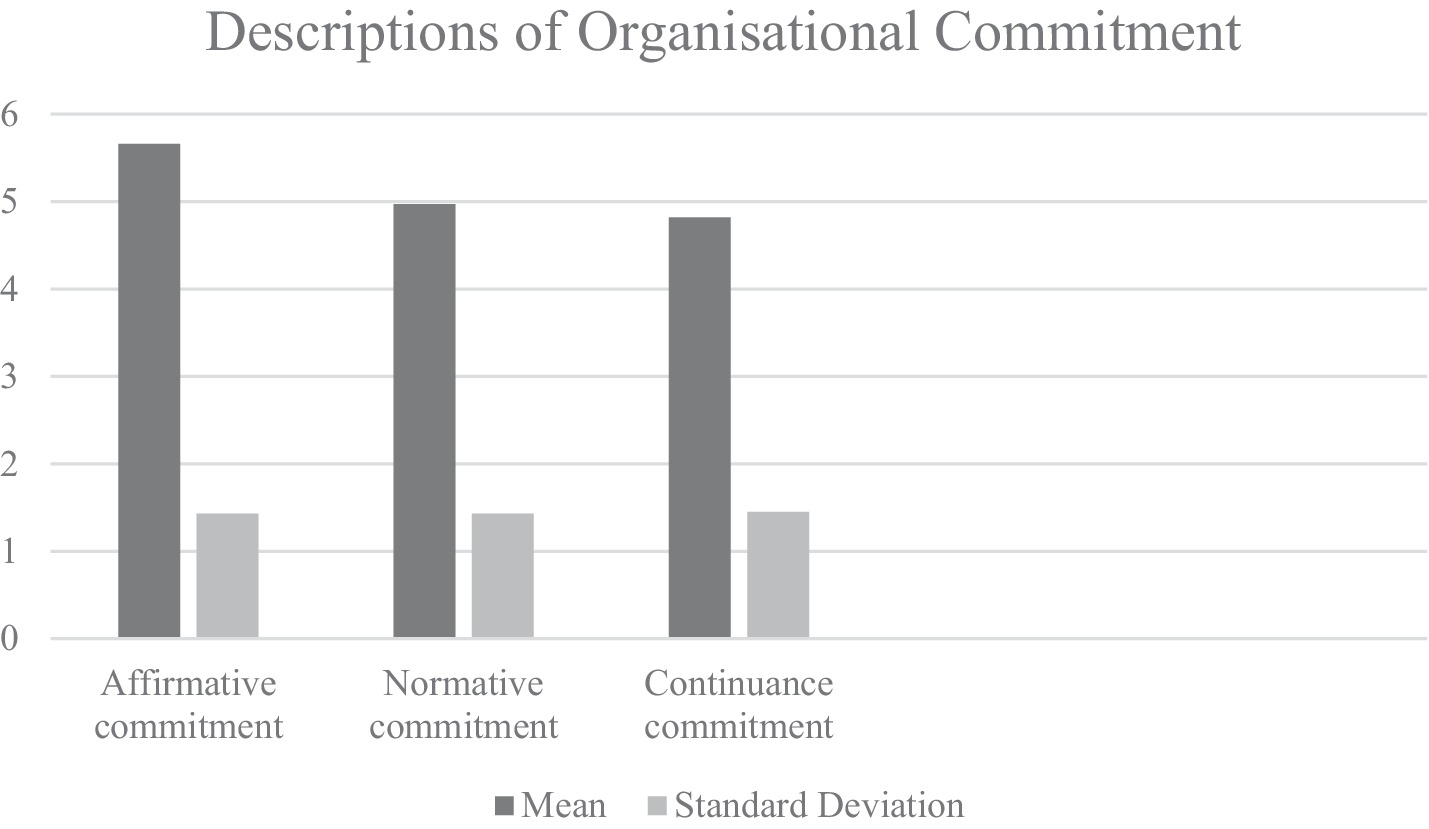

Table 3 presents the relationships between each domain of shared leadership (SL) and each domain of organizational commitment (OC). The correlation analysis indicates significant relationships between Planning and Organizing and all domains of OC, with a p-value <0.05. The findings also reveal significant relationships between Problem Solving and all domains of OC, with a p-value <0.05. For Support and Consideration, the p-value is <0.05 across all domains of OC, indicating significant relationships between Support and Consideration and all domains of OC. Lastly, Development and Mentoring had a p-value of 0.005, which is less than the critical value of 0.05, suggesting significant relationships between Development and Mentoring and all domains of OC.

Table 3. Correlations among the shared leadership domains and the organizational commitment domains.

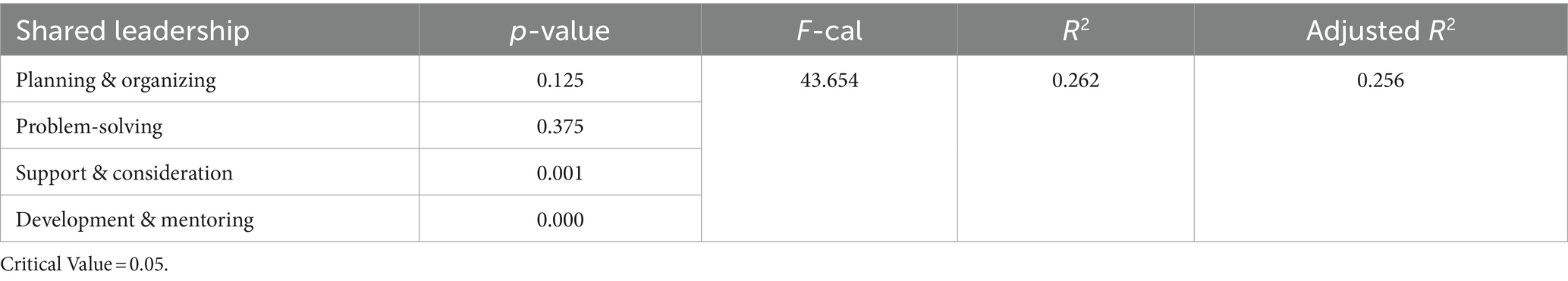

Shared leadership as a predictor of organizational commitment

In addition to examining the association between shared leadership (SL) and organizational commitment (OC), the present study also explored whether SL significantly predicts OC. We performed a regression analysis to identify the specific domain(s) of SL that predict OC. The results of our analysis showed that Support and Consideration and Development and Mentoring significantly predict organizational commitment in university settings, with p < 0.05 (see Table 4 for details). However, the other two dimensions of SL, Planning and Organizing and Problem Solving, were not found to be significant predictors of OC.

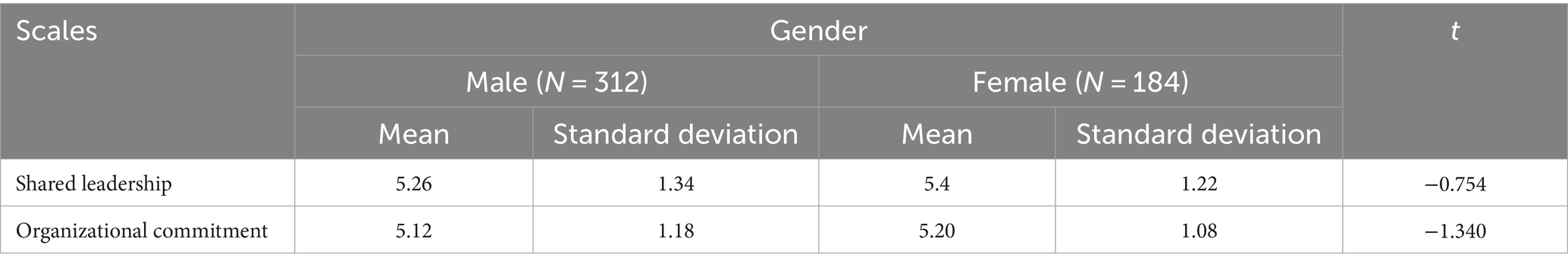

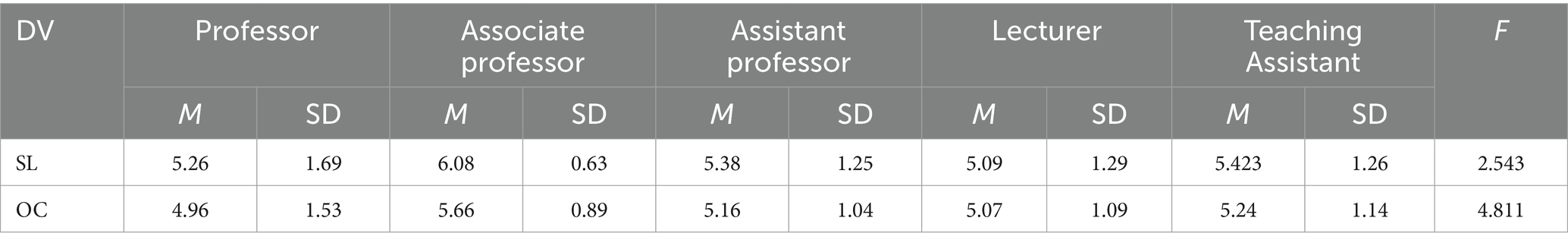

Differences in shared leadership and organizational commitment with respect to participants’ demographics

The fourth and last question of the current study focused on confirming if there are any significant differences in SL and OC concerning participants’ demographics, such as gender, faculty ranking, and years of experience. In order to examine the gender-based differences, we conducted an independent sample t-test with ‘gender’ as an independent variable and ‘SL’ and ‘OC’ as dependent variables. The results of the t-test indicated that there were no significant differences between males (M = 5.26, SD = 1.34) and females (M = 5.4, SD = 1.22) on their scores for SL; t(494) = −0.754, p > 0.05. Similarly, no significant differences were found in participants’ scores for ‘OC’ between males (M = 5.12, SD = 1.18) and females (M = 5.20, SD = 1.08) faculty members; t(494) = −1.340, p > 0.05. Overall, these results suggest that male and female participants are almost at similar levels of shared leadership and organizational commitment (see Table 5).

We conducted a one-way between-subjects ANOVA to examine if significant differences existed concerning faculty rank (position). Table 6 presents the means and standard deviations of SL and OC by faculty rank. The mean SL and OC scores for associate professors were 6.08 and 5.66, respectively, which were relatively high compared to other faculty ranks. However, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed no significant differences in the two scales (SL and OC) among the various faculty ranks.

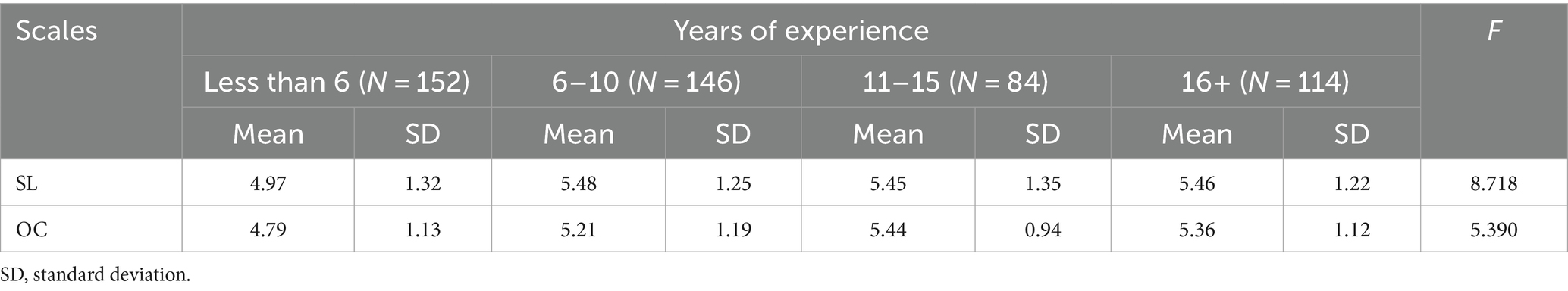

Table 7 depicts the means and standard deviations of SL and OC by years of experience. For SL, the mean for those with 6–10 years of experience was slightly higher than for those with 11–15 years and 16+ years. For OC, the mean for those with 11–15 years of experience was higher than for other ranges. The ANOVA indicated no significant differences in SL and OC based on years of experience. Therefore, we rejected the hypothesis that there are significant differences in SL and OC based on years of experience.

Table 7. Differences in shared leadership and organizational commitment according to their year of experience.

Discussion

Shared leadership (SL) has gained recognition as a vital model for enhancing organizational effectiveness, especially in the collaborative environments typical of higher education institutions (HEIs). This study aimed to investigate the impact of SL on organizational commitment (OC) within Saudi HEIs. The findings contribute significantly to the theoretical understanding of both SL and OC and offer practical insights for effective implementation within educational settings.

Alignment with research questions

The primary research question explored how SL influences OC among faculty members in Saudi HEIs. The study found that specific SL practices, particularly the Development and Mentoring style, significantly enhance faculty members’ affective commitment to their institutions. This aligns with the hypothesis that participatory leadership models would foster greater engagement and loyalty among faculty. For example, faculty who experienced mentoring relationships reported feeling more valued and invested in their roles, supporting the idea that emotional attachment drives organizational commitment.

Furthermore, the study examined the relationship between SL dimensions and the various components of OC, specifically affective, normative, and continuance commitment. The results indicated that while Development and Mentoring strongly influenced affective commitment, the Support and Consideration dimension also played a role in fostering normative commitment. This finding builds on previous research by Meyer and Allen (1991), which emphasized the importance of emotional attachment in enhancing OC. Our results contribute to the literature by highlighting that SL not only influences commitment levels but also modifies the nature of that commitment.

Contributions to SL and OC theory

This research extends the existing literature on SL, which has predominantly focused on Western contexts (Pearce and Conger, 2002; Wang et al., 2021). By demonstrating the effectiveness of SL in Saudi HEIs, this study challenges the notion that hierarchical leadership models are the only viable approach in non-Western cultures. Specifically, our findings reveal that faculty members in Saudi HEIs respond positively to SL practices, particularly in relation to Development and Mentoring, which was the most frequently practiced and had the strongest influence on OC.

From a theoretical perspective, this suggests that SL can transcend cultural boundaries, reinforcing the universality of collaborative leadership models. SL theory emphasizes the distribution of leadership responsibilities among team members, but this study adds a new layer by highlighting the importance of contextual adaptability. For example, while the Development and Mentoring style of SL was particularly effective in this study, it might be less dominant in other contexts. This emphasizes the need for SL theory to consider cultural nuances and situational factors when being applied in different settings.

Additionally, the study contributes to OC theory by showing how specific SL styles enhance different dimensions of OC. The empirical evidence presented indicates that SL practices, particularly the Development and Mentoring dimension, significantly enhance affective commitment by fostering emotional attachment to the institution. This suggests that SL’s impact on OC is largely driven by its ability to create a supportive, growth-oriented environment where faculty members feel valued and engaged, leading to higher loyalty and job satisfaction. Furthermore, the findings challenge traditional views on normative commitment by suggesting that participatory leadership reduces the sense of obligation, making employees stay because they want to, not because they feel they must.

Practical implications for higher education institutions

The findings offer practical insights for the implementation of SL styles in HEIs, particularly in non-Western contexts like Saudi Arabia. The Development and Mentoring style provide a concrete example of how faculty members can be supported in their professional growth. HEIs could formalize mentoring programs where senior faculty members guide junior colleagues in teaching strategies, research, and career development. These mentoring relationships can enhance affective commitment by fostering a sense of belonging and purpose, as supported by the study’s findings.

Moreover, Support and Consideration, another SL dimension, offers a practical avenue for HEIs. Faculty members thrive in environments where their voices are heard and they feel empowered to contribute to decision-making processes. One effective implementation strategy would be to establish faculty councils or committees that engage faculty members in institutional governance. Such participatory governance structures would enhance faculty members’ emotional investment in the institution, reinforcing both affective and normative commitment.

Furthermore, the study’s findings indicate that Planning and Organization, an essential SL style, is closely linked to teachers’ involvement in institutional decision-making processes. HEIs could implement shared leadership by fostering inclusive strategic planning processes where faculty members participate in shaping the university’s long-term vision. This approach not only strengthens OC but also aligns with research by Graham (1996) and Amtu et al. (2021), which emphasize that faculty engagement in decision-making processes enhances commitment. Such participatory practices can enhance not only normative commitment but also a sense of shared ownership and responsibility among faculty members.

The practical implications of these findings are substantial for HEIs seeking to improve faculty commitment and institutional effectiveness. Institutions should consider implementing structured mentorship programs that prioritize the Development and Mentoring style, which has been shown to strengthen affective commitment. By fostering an environment where faculty members feel valued and supported, institutions can cultivate higher levels of engagement and job satisfaction.

Integration of literature with study findings

Integrating previous literature with the study’s findings is crucial for reinforcing the results and demonstrating their alignment with existing knowledge. The work of Kalkan et al. (2020), which discusses the development of schemas of attitude and behavior for exploring OC, aligns with the current study’s finding that active involvement in decision-making processes enhances OC. By showing that engagement in shared leadership can build such schemas, the present study adds depth to the conceptual understanding of OC, reinforcing the idea that leadership styles influence behavioral and attitudinal changes in faculty members.

Additionally, the study’s findings resonate with Hussein and da Costa (2008), who found that participatory management practices positively affect OC. The strong relationship observed in this study between SL and OC demonstrates that SL’s emphasis on participation and collaboration aligns with the broader leadership literature, where faculty involvement in leadership fosters loyalty and engagement (Bohórquez, 2014). These connections between the study’s findings and existing research help to position SL as a critical factor in enhancing organizational loyalty and commitment within educational settings.

Almutairi (2020) also supports the current study’s findings by indicating that intrinsic motivators, such as professional growth and mentorship, are more impactful than external rewards in fostering OC. This provides a nuanced understanding of how leadership influences commitment, emphasizing the need for HEIs to focus on intrinsic motivators when implementing SL practices.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. The research was conducted at a single government university in Saudi Arabia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other HEIs or cultural contexts. The specific characteristics of the institution, such as its size and governance structure, may not be representative of all Saudi universities. Additionally, the cross-sectional design captures a snapshot in time, making it challenging to infer causality between SL practices and OC. Future research could benefit from longitudinal studies that track changes in commitment over time in response to SL interventions.

Sampling also presents limitations; while we achieved a response rate of 12.4 percent, potential biases may exist in self-reported data, where faculty members may provide socially desirable responses. Further research should consider incorporating diverse methodologies, such as qualitative interviews, to deepen understanding of faculty perceptions of SL and its impact on OC.

Conclusion

This study provides compelling evidence that shared leadership (SL) significantly enhances faculty organizational commitment (OC) within Saudi higher education institutions (HEIs). The findings reveal that the Development and Mentoring style of SL is not only the most commonly practiced but also the most effective in fostering emotional attachment among faculty members. As faculty who feel supported and mentored demonstrate greater loyalty and commitment, these insights highlight the critical role that collaborative leadership can play in the educational landscape.

Relevance of the study

The relevance of this research lies in its contribution to the growing body of literature on SL, particularly in non-Western contexts where hierarchical leadership models have traditionally dominated. By demonstrating the effectiveness of SL in Saudi HEIs, this study challenges prevailing notions about leadership dynamics in different cultural settings. It reinforces the idea that participatory and supportive leadership approaches can transcend cultural boundaries and significantly enhance faculty engagement and retention.

Future directions

Future research could further explore the long-term effects of SL on OC, employing longitudinal studies to assess how sustained SL practices influence faculty commitment over time. Additionally, investigating the impact of SL in diverse non-Western educational contexts will help determine the universality and adaptability of these practices. A mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative and qualitative data, could provide richer insights into how SL operates in practice and its nuanced effects on faculty engagement.

In conclusion, this study underscores the importance of adopting shared leadership practices in higher education, particularly in non-Western settings. By prioritizing supportive and participatory leadership approaches, HEIs can significantly enhance faculty commitment, improve job satisfaction, and ultimately drive institutional success.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aboramadan, M., Albashiti, B., Alharazin, H., and Dahleez, K. A. (2020). Human resources management practices and organizational commitment in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 34, 154–174. doi: 10.1108/ijem-04-2019-0160

Afsar, B., Masood, M., and Umrani, W. A. (2019). The role of job crafting and knowledge sharing on the effect of transformational leadership on innovative work behavior. Pers. Rev. 48, 1186–1208. doi: 10.1108/PR-04-2018-0133

Akbari, M., Kashani, S. H., and Hooshmand Chaijani, M. (2016). Sharing, caring, and responsibility in higher education teams. Small Group Res. 47, 542–568. doi: 10.1177/1046496416667609

Akdemir, Ö. A., and Ayik, A. (2017). The impact of distributed leadership behaviors of school principals on the organizational commitment of teachers. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 5, 18–26. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2017.051402

Alamri, M. S., and Al-Duhaim, T. I. (2017). Employees perception of training and its relationship with organizational commitment among the employees working at Saudi industrial development fund. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 8, 25–39. doi: 10.5430/ijba.v8n2p25

Allen, N. J., and Meyer, J. P. (1996). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: an examination of construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 49, 252–276. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1996.0043

Almutairi, Y. M. N. (2020). Leadership self-efficacy and organizational commitment of faculty members: higher education. Admin. Sci. 10:66. doi: 10.3390/admsci10030066

Alsaeedi, F., and Male, T. (2013). Transformational leadership and globalization: attitudes of school principals in Kuwait. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadership 41, 640–657. doi: 10.1177/1741143213488588

Alsiewi, A. M. (2016). Normative commitment in the educational sector: the Libyan perspective. J. Res. Mech. Eng. 2, 7–16.

Alsubaie, T. (2021). The Influence of Participative Leadership on Employee Performance: A Case of the Public Sector in Saudi Arabia (Order No. 28317906). Available at: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/influence-participative-leadership-on-employee/docview/2494880327/se-2

Amtu, O., Souisa, S. L., Joseph, L. S., and Lumamuly, P. C. (2021). Contribution of leadership, organizational commitment and organizational culture to improve the quality of higher education. Int. J. Innov. 9, 131–157. doi: 10.5585/iji.v9i1.18582

Avolio, B. J., Jung, D. I., Murry, W., and Sivasbramaniam, N. (1996). Building highly developed teams: Focusing on shared leadership process, efficacy, trust, and performance. in Advances in interdisciplinary studies of work teams: team leadership. eds. M. M. Beyerlein, D. A. Johnson, and S. T. Beyerlein, vol. 3 (Elsevier Science/JAI Press), 173–209.

Avolio, B. J., Reichard, R. J., Hannah, S. T., Walumbwa, F. O., and Chan, A. (2009). A meta-analytic review of leadership impact research: experimental and quasi-experimental studies. Leadersh. Q. 20, 764–784. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.06.006

Babalola, S. S. (2016). The effect of leadership style, job satisfaction and employee-supervisor relationship on job performance and organizational commitment. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 32, 935–946. doi: 10.19030/jabr.v32i3.9667

Baker-Shelley, A., van Zeijl-Rozema, A., and Martens, P. (2017). A conceptual synthesis of organisational transformation: how to diagnose, and navigate, pathways for sustainability at universities? J. Clean. Prod. 145, 262–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.026

Balthazard, P., Waldman, D., Howell, J., and Atwater, L. (2004). Shared leadership and group interaction styles in problem-solving virtual teams. In Proceedings of the 37th annual Hawaii international conference on system sciences, 2004 10. IEEE.

Bergman, J. Z., Rentsch, J. R., Small, E. E., Davenport, S. W., and Bergman, S. M. (2012). The shared leadership process in decision-making teams. J. Soc. Psychol. 152, 17–42. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2010.538763

Bohórquez, N. B. (2014). Organizational commitment and leadership in higher education institutions. Revista Civilizar De Empresa Y Economía 5, 7–19. doi: 10.22518/2462909X.263

Bolden, R., and Petrov, G. (2014). Hybrid configurations of leadership in higher education employer engagement. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 36, 408–417. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2014.916465

Bolden, R., Petrov, G., and Gosling, J. (2009). Distributed leadership in higher education: rhetoric and reality. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadership 37, 257–277. doi: 10.1177/1741143208100301

Breitsohl, H., and Ruhle, S. (2013). Residual affective commitment to organizations: concept, causes and consequences. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 23, 161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.07.008

Carson, J. B., Tesluk, P. E., and Marrone, J. A. (2007). Shared leadership in teams: an investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 1217–1234. doi: 10.2307/20159921

Choi, E. H., Kim, E. K., and Kim, P. B. (2018). Effects of the educational leadership of nursing unit managers on team effectiveness: mediating effects of organizational communication. Asian Nurs. Res. 12, 99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2018.03.001

Claudet, J. (2012). Redesigning staff development as organizational case learning: tapping into school stakeholders’ collaborative potential for critical reflection and transformative leadership action. Open J. Leadership 1, 22–36. doi: 10.4236/ojl.2012.14005

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., and Dorfman, P. W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? J. Manag. 26, 5–30. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600106

D'Innocenzo, L., Kukenberger, M., Farro, A. C., and Griffith, J. A. (2021). Shared leadership performance relationship trajectories as a function of team interventions and members' collective personalities. Leadersh. Q. 32:101499. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101499

Drescher, M. A., Korsgaard, M. A., Welpe, I. M., Picot, A., and Wigand, R. T. (2014). The dynamics of shared leadership: building trust and enhancing performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 99:771. doi: 10.1037/a0036474

Ensley, M. D., Hmieleski, K. M., and Pearce, C. L. (2006). The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: implications for the performance of startups. Leadersh. Q. 17, 217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.002

Fausing, M. S., Joensson, T. S., Lewandowski, J., and Bligh, M. (2015). Antecedents of shared leadership: empowering leadership and interdependence. Leadership Organ. Dev. J. 36, 271–291. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-06-2013-0075

Graham, K. C. (1996). Running ahead enhancing teacher commitment. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 67, 45–47. doi: 10.1080/07303084.1996.10607182

Han, Z., Guo, K., Xie, L., and Lin, Z. (2018). Integrated relative localization and leader–follower formation control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 64, 20–34. doi: 10.1109/TAC.2018.2800790

Hiller, N. J., Day, D. V., and Vance, R. J. (2006). Collective enactment of leadership roles and team effectiveness: a field study. Leadersh. Q. 17, 387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.004

Hoch, J. E. (2013). Shared leadership and innovation: the role of vertical leadership and employee integrity. J. Bus. Psychol. 28, 159–174. doi: 10.1007/s10869-012-9273-6

Hoch, J. E., and Kozlowski, S. W. (2014). Leading virtual teams: hierarchical leadership, structural supports, and shared team leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 99:390. doi: 10.1037/a0030264

Hulpia, H., and Devos, G. (2010). How distributed leadership can make a difference in teachers' organizational commitment? A qualitative study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.08.006

Hussein, M. F., and da Costa, J. L. (2008). Organizational commitment and its relationship to perceived leadership style in an Islamic school in a large urban Centre in Canada: teachers’ perspectives. J. Contemp. Iss. Educ. 3. doi: 10.20355/C5X59T

Kalkan, Ü., Altınay Aksal, F., Altınay Gazi, Z., Atasoy, R., and Dağlı, G. (2020). The relationship between school administrators’ leadership styles, school culture, and organizational image. SAGE Open 10:2158244020902081. doi: 10.1177/2158244020902081

Khan, A. J., Bashir, F., Nasim, I., and Ahmad, R. (2021). Understanding affective, normative & continuance commitment through the lens of training & development. iRASD J. Manag. 3, 105–113. doi: 10.52131/jom.2021.0302.0030

Koeslag-Kreunen, M., Van den Bossche, P., Van der Klink, M. R., and Gijselaers, W. H. (2020). Vertical or shared? When leadership supports team learning for educational change. High. Educ. 82, 19–37. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00620-4

Koeslag-Kreunen, M. G., Van der Klink, M. R., Van den Bossche, P., and Gijselaers, W. H. (2018). Leadership for team learning: the case of university teacher teams. High. Educ. 75, 191–207. doi: 10.1007/s10734-017-0126-0

Kok, S. K., and McDonald, C. (2017). Underpinning excellence in higher education–an investigation into the leadership, governance and management behaviours of high-performing academic departments. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 210–231. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1036849

Lo, M. C., Ramayah, T., Min, H. W., and Songan, P. (2010). The relationship between leadership styles and organizational commitment in Malaysia: role of leader–member exchange. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 16, 79–103. doi: 10.1080/13602380903355676

Mehra, A., Smith, B. R., Dixon, A. L., and Robertson, B. (2006). Distributed leadership in teams: the network of leadership perceptions and team performance. Leadersh. Q. 17, 232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.003

Meyer, J. P., and Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1, 61–89. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Morin, A. J., and Vandenberghe, C. (2015). Dual commitment to organization and supervisor: a person-centered approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 88, 56–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.02.001

Mihalache, O. R., Jansen, J. J., Van den Bosch, F. A., and Volberda, H. W. (2014). Top management team shared leadership and organizational ambidexterity: a moderated mediation framework. Strateg. Entrep. J. 8, 128–148. doi: 10.1002/sej.1168

Millward, P., and Timperley, H. (2010). Organizational learning facilitated by instructional leadership, tight coupling and boundary spanning practices. J. Educ. Chang. 11, 139–155. doi: 10.1007/s10833-009-9120-3

Morrow, P. C. (2011). Managing organizational commitment: insights from longitudinal research. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 18–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.008

Ndlovu, W., Ngirande, H., Setati, S. T., and Zhuwao, S. (2018). Transformational leadership and employee organisational commitment in a rural-based higher education institution in South Africa. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 16, 1–7. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.984

Nguyen, L. G. T., and Pham, H. T. (2020). Factors affecting employee engagement at not-for-profit organizations: a case in Vietnam. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 7, 495–507. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no8.495

Pahi, M. H., Ahmed, U., Sheikh, A. Z., Dakhan, S. A., Khuwaja, F. M., and Ramayah, T. (2020). Leadership and commitment to service quality in Pakistani hospitals: the contingent role of role clarity. SAGE Open 10:2158244020963642. doi: 10.1177/2158244020963642

Pearce, C. L., and Conger, J. A. (2002). Shared leadership: reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Sage Publications.

Pearce, C. L., and Herbik, P. A. (2004). Citizenship behavior at the team level of analysis: the effects of team leadership, team commitment, perceived team support, and team size. J. Soc. Psychol. 144, 293–310. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.144.3.293-310

Pearce, C. L., and Sims, H. P. Jr. (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: an examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 6:172. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.6.2.172

Pudjowati, J., Cakranegara, P. A., Pesik, I. M., Yusuf, M., and Sutaguna, I. N. T. (2022). The influence of employee competence and leadership on the organizational commitment of Perumda Pasar Juara employees. Jurnal Darma Agung 30, 606–613. doi: 10.46930/ojsuda.v30i2.2279

Trivellas, P., and Santouridis, I. (2016). Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between service quality and organisational commitment in higher education. An empirical study of faculty and administration staff. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 27, 169–183. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2014.969595

Uluöz, T., and Yağci, E. (2018). Opinions of education administrators regarding the impact of their leadership features on the mobbing and organisational commitment of teachers. Amaz. Invest. 7, 101–110. Available at: https://www.amazoniainvestiga.info/index.php/amazonia/article/view/382

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., and Panaccio, A. (2017). Affective commitment to organizations and supervisors and turnover: a role theory perspective. J. Manag. 43, 2090–2117. doi: 10.1177/0149206314559779

Wahlstrom, K. L., and Louis, K. S. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: the roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educ. Adm. Q. 44, 458–495. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08321502

Wang, Z., Ren, S., Chadee, D., Liu, M., and Cai, S. (2021). Team reflexivity and employee innovative behavior: the mediating role of knowledge sharing and moderating role of leadership. J. Knowl. Manag. 25, 1619–1639. doi: 10.1108/JKM-09-2020-0683

Wang, D., Waldman, D. A., and Zhang, Z. (2014). A meta-analysis of shared leadership and team effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 99:181. doi: 10.1037/a0034531

Wasserman, S., and Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wayoi, D. S., Margana, M., Prasojo, L. D., and Habibi, A. (2021). Dataset on Islamic school teachers’ organizational commitment as factors affecting job satisfaction and job performance. Data Brief 37, 107–181. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2021.107181

Wu, C. M., and Chen, T. J. (2018). Collective psychological capital: linking shared leadership, organizational commitment, and creativity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 74, 75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.02.003

Yahaya, R., and Ebrahim, F. (2016). Leadership styles and organizational commitment: literature review. J. Manag. Dev. 35, 190–216. doi: 10.1108/JMD-01-2015-0004

Zhu, J., Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., and Johnson, R. E. (2018). Shared leadership: a state-of-the-art review and future research agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 834–852. doi: 10.1002/job.2296

Appendix A: Questionnaire

Keywords: shared leadership, organizational commitment, higher education, educational leadership, leadership development, mentoring, faculty engagement, institutional performance

Citation: Alghamdi AA (2024) Enhancing organizational commitment through shared leadership: insights from Saudi higher education. Front. Educ. 9:1476709. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1476709

Edited by:

Francis Thaise A. Cimene, University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, PhilippinesReviewed by:

Karolina Eszter Kovács, University of Debrecen, HungaryAan Komariah, Indonesia University of Education, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Alghamdi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Atiyah A. Alghamdi, YWFsYXRpYUBrc3UuZWR1LnNh

Atiyah A. Alghamdi

Atiyah A. Alghamdi