95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ. , 13 November 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1473967

The perception of political bias in higher education persists even in the face of scarce evidence that liberal professors penalize conservative students or favor liberal ones. We investigated the degree to which college professors used student appearance to ascertain political orientation, and whether liberal-looking students were rated more favorably. Ninety-eight (98) professors rated a student on logic, likeability, and political leaning. The hypothetical student’s dress (bohemian vs. business casual) and hairstyle (brown hair vs. pink hair) were manipulated to cue political orientation. Results indicated that professors used student appearance to ascertain liberal political leaning but did not rate the students significantly different on logic and likeability. These results suggest that while professors use appearance cues, they do not favor students who appear liberal leaning or punish those who look less liberal.

College campuses are conceptualized as hotbeds of liberal bias where students are indoctrinated by professors (Horowitz and Laksin, 2009; Gross, 2013; PEW Research Center, 2017). While it is true that the professoriate leans liberal, little evidence suggests that professors silence or indoctrinate students, or otherwise penalize them when grading (Burmila, 2021; Musgrave and Rom, 2015). The mismatch between perceived bias and actual bias may lead to false polarization, or the belief that liberal professors are more biased than they actually are (Levendusky and Malhotra, 2016). The current research examines whether American professors use appearance cues related to hairstyle and clothing to ascertain student political orientation. In addition, the current research explores the degree to which professor political orientation impacts ratings of student logic and likeability based on appearance cues that may signal student political leaning. Because professors rarely are directly given information regarding the political group to which students belong, the current research seeks to establish a paradigm of manipulating appearance as a proxy for student political orientation.

Some have argued that college professors are disproportionately liberal, and as a result, silence conservative students and push their own, more left-leaning beliefs on students (Hebel, 2004). Many believe liberal bias in undergraduate settings hinders conservative students from being able to take the classes they want, find an advisor whose views align with theirs, and pursue graduate studies (Horowitz and Lehrer, 2020). Right-wing scholar and activist David Horowitz has created the Academic Bill of Rights, the goal of which is to “inspire college officials to enforce the rules that were meant to ensure the fairness and objectivity of the college classroom” by protecting students from one-sided liberal propaganda (Mariani and Hewitt, 2008, p. 773). Further, in February 2017, then U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos publicly stated “The faculty, from adjunct professors to deans, tell you what to do, what to say, and more ominously, what to think” (Strauss, 2017).

With few exceptions, research does show that liberal, left-leaning professors outnumber conservative, right-leaning professors in academia (Zipp and Fenwick, 2006). However, the idea that liberal professors are indoctrinating conservative students is not well supported. Mariani and Hewitt (2008) found that professor ideology had very little association with any change in students’ political ideological orientation. That is, despite there being a large number of liberal faculty in academia, the ideological changes of students from freshman year to post-graduation were indicative of ideological change trends of the general population and did not reflect any liberal “brainwashing” of students. Further, changes in student party identification before and after an academic semester were found to be unrelated to professor partisanship (Burmila, 2021; Woessner and Kelly-Woessner, 2009).

Most research on political grading bias has been done in the context of affinity bias; the idea that professors favor students who agree with their own partisan beliefs. Studies examining political affinity bias on grading have generally found that liberal instructors do not assign lower grades to conservative students or higher grades to liberal students (Musgrave and Rom, 2015; Bar and Zussman, 2012; Woessner et al., 2019). Indicative of the discrepancies between perception and actual concurrence of political bias in education, little evidence has been uncovered suggesting that conservative students are penalized for their political orientation (Burmila, 2021; Mariani and Hewitt, 2008; Kemmelmeier et al., 2005).

There are relevant methodological concerns when studying political grading bias in higher education. First, it should be noted that many studies examining professor political bias have focused on grading in political science courses (Burmila, 2021; Musgrave and Rom, 2015). Political science courses make up only a small percentage of courses offered in university settings. Second, teachers may be practiced in consciously working to minimize their expressions of implicit and explicit biases during experimental studies that examine bias (Evers and Kneyber, 2016; Frankenberg, 2010). A possible explanation for the lack of evidence for political bias in grading may be that the student’s political leanings are made suspiciously explicit, and professors are pressured by social desirability to rate students fairly in experimental studies. Political bias has been measured by asking instructors to rate student responses to political essay prompts in strong support of either the Republican or Democratic Party by a student who was described as Democrat or Republican (Musgrave and Rom, 2015). With more subtle manipulation of the student political orientation, professors may be less guarded while grading. For example, without explicit identification of student political orientation, professors may default to other cues, such as physical appearance, to make judgments regarding their students’ political orientation.

People communicate information about themselves through their physical appearance and may use this information to categorize and make judgements about others (Quinn et al., 2009). Appearance stereotypes are often studied in the contexts of race, status, and physical attraction, yet appearance serves as a vehicle for even more varied forms of judgement (Rohner and Rasmussen, 2011; Wilkins et al., 2011; Malloy et al., 2021; Griffin and Langlois, 2006). For example, physical appearance has been found to cue political orientation (Olivola et al., 2012). Carpinella and Johnson (2013) found that judgements of political party affiliation were related to sex-typicality of facial cues differently for Republicans and Democrats. Rule and Ambady (2010) found people can accurately categorize faces as Democrat or Republican. These assumptions were based on stereotyping Republicans as looking powerful, and Democrats as looking warm (Rule and Ambady, 2010).

Clothing can also activate schemas and potentially alter perceptions (Livingston and Gurung, 2019). For example, the stereotypes associated with clothing in an Active Shooter Simulator video game led to either higher or lower rates of prejudicial racial bias (Kahn and Davies, 2017). Research has not yet examined how clothing and a variety of other appearance cues impact political bias. Professors may draw on beliefs of liberals being more expressive (Block and Block, 2006) and preferring color and abstraction (Furnham and Avison, 1997). They may also fall into common stereotypes of conservatives being concerned with wealth (Ahler and Sood, 2018) and preferring simplicity and unambiguousness (Furnham and Avison, 1997). It is likely that these beliefs regarding student partisanship are based, at least in part, by student dress and hairstyle.

We seek to fill a gap in the research surrounding assumptions about partisan identity based on appearance and political bias in grading. The current study examines the degree to which college professors make assumptions regarding student political orientation based on student clothing and hairstyle. We expect that a student with pink hair and colorful clothing will be rated as more liberal than the same student with brown hair wearing business casual clothing. We also examine the degree to which both liberal and conservative professors rate a student who appears liberal or more conservative on measures of likability and logic. Based on past empirical research, we did not expect logic or likeability ratings to differ for liberal versus less liberal appearing students.

116 undergraduate professors were recruited from a number of four-year universities through email. We intentionally recruited participants from some traditionally conservative colleges so that our sample might be more politically balanced. Data from 18 participants were discarded because of premature exiting from the survey (16) or because participants omitted their political orientation (2). After exclusions, data from 98 participants was analyzed. 46% of participants identified as men, 50% as women, and 4% preferred not to say. 74.5% of participants reported they were liberal and 25.5% identified as conservative. Although the majority of professors in our sample identified as leaning liberal, our conservative sample was relatively larger than expected given the ratio of liberal to conservative professors in academia.

We created two student biographies that were the same except for the photograph of the student, Olivia O’Connor. The bios contained a headshot of a female college student, her year in college, major and minor, favorite courses, and extracurricular activities. The headshots represented the only difference between the two bios. In the less liberal-appearing headshot, the student was wearing business casual clothing, pearl jewelry, and wore her light brown hair in a bun. In the more liberal-appearing headshot, the student was dressed in a colorful crocheted top, wore a nose ring, and had pink streaks in her hair (see Appendix A).

Participants read the student’s written response to the prompt “Should university dining halls be open 24-h a day or during traditional mealtimes.” This response described the student’s desire for 24-h dining and was created by the authors to be an argument that was somewhat logical, but that could easily be critiqued. The structure of the Student Written Response was modeled after the Racial Arguments Scale (Saucier and Miller, 2003) which is based on the assumption that biased assimilation of information occurs when people evaluate information related to social groups.

Participants were asked to rate the logic of the student’s written assignment using three items, “The argument supports the conclusions offered by the student,” “The evidence presented is logical,” and “The argument is coherent/persuasive.” Answer options were presented in multiple choice format containing a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Adapted from Reysen’s likability scale (Reysen, 2005), participants were asked to rate the student on the following six attributes: friendliness, likability, warmth, expression of power, approachableness, and knowledge. Answer options were presented in multiple choice format using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the six items was good at 0.81.

One question targeted the estimated political orientation of the target student. Participants were asked to estimate the political leaning of the student on a 6-point scale where 1 = extremely liberal, 2 = liberal, 3 = slightly liberal, 4 = slightly conservative, 5 = conservative, and 6 = extremely conservative.

Participants received an email from the researchers asking if they would be willing to participate in a study about professor evaluation of students’ logical reasoning. After opening the Qualtrics link from the email and giving consent, participants were told that they would be viewing information and written work of one student and making ratings about it. Participants were randomly assigned to view either the pink-hair or brown-bun student bio (please refer to Appendix A). Next, the prompt for the student written assignment and response was displayed and participants were instructed to carefully read the materials. After a minute of reading the Student Written Response, participants completed the Logic and Likeability Ratings. Then they were asked to estimate the Political Leaning of the student and answer two attention check questions concerning the student and their written response Last participants indicated their political orientation, were debriefed, and thanked for their participation. All materials are available at https://osf.io/det57/?view_only=5812d7bf7893429b99fb8db53c5952f6 (Study 2).

We were interested in the degree to which professors used student appearance to make assumptions regarding the student’s political orientation. We were also interested in whether professor political orientation impacted those judgements. We computed a 2 (student appearance: pink hair, bun) by 2 (professor political leaning: liberal, conservative) between groups ANOVA on the estimate of the student’s political orientation. Professors, regardless of their own political orientation, estimated that the pink-haired student was more liberal (M = 2.63, SD = 0.89) than the brown-bun student (M = 3.23, SD = 0.87), F (1, 94) = 7.50, p = 0.007, d = 0.68. Neither the main effect of professor political orientation nor the interaction were significant, p’s > 0.10. Note that the average rating for the pink-haired student was between liberal and slightly liberal, which indicates that professors perceived the pink-haired student as more liberal than conservative. However, the brown bun student’s average rating was between slightly liberal and slightly conservative, indicating that professors perceived this student as more middle-of-the-road politically (not conservative).

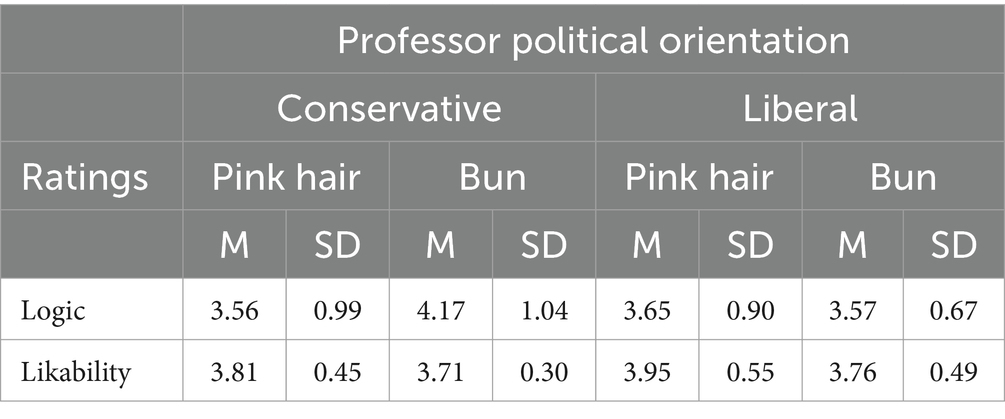

Across all conditions, logic (M = 3.67, SD = 0.86) and likeability (M = 3.84, SD = 0.50) ratings were in the middle of the scale and were not highly correlated (r = 0.26). Further, perceived student political leaning was not correlated with professor ratings of student logic, r (96) = −0.16, p = 0.12, or likeability, r (96) = −0.11, p = 0.28. Two 2 (student appearance: pink hair, bun) by 2 (professor political leaning: liberal, conservative) between groups ANOVAs were computed on logic and likeability ratings. Neither student appearance nor professor political orientation significantly impacted the logic rating given to the student’s written response, p’s > 0.10. However, a marginally significant interaction was found, F(1, 94) = 2.94, p = 0.09. Conservative professors rated the student response as marginally more logical when they viewed the brown bun student (M = 4.17, SD = 1.04) compared to the pink-haired student (M = 3.56, SD = 0.99), t (23) = 1.49, p = 0.075, d = 0.60. Liberal professors did not rate the logic of the written student response differently based on student appearance. Likeability ratings were not dependent upon student appearance, professor political orientation, or the interaction between the two variables, p’s > 0.20 (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations).

Table 1. Logic and likeability ratings by appearance condition and political orientation of professor.

The finding that professors assumed a student wearing a colorful shirt with pink hair and a nose ring was more liberal than a student wearing business attire and a tight bun is congruent with research illustrating the categorization of people into groups based on appearance characteristics (Quinn et al., 2009). Expanding on past research showing facial features communicate political party membership (Rule and Ambady, 2010), results show stereotypical clothing and hairstyles can also cue political affiliations in a classroom. Results indicate that professors -regardless of political leaning—use student appearance to make assumptions about student political orientation. Importantly, the pink-haired student wearing a nose ring and a crocheted vest was judged to be liberal, but the student wearing a bun, pearls, and business casual clothing was not judged to be particularly conservative. This may be due to professors using known base rates regarding student political orientation—individuals attending college tend to be more liberal than those who do not go to college (Edelmann and Vaisey, 2023).

The lack of significant results concerning the logic and likeability ratings tell us that even though professors may use appearance cues to ascertain political leaning of their students, they are not rewarding students who they perceive to be liberal. Although we found no evidence of liberal bias, we did find that conservative professors rated the more liberal-appearing student slightly lower on logic than the less liberal-appearing student. This result must be interpreted with caution, however, given the small number of conservative professors that completed the study. Future research could examine whether conservative professors sense a threat to their group’s status, and if perceived threat is associated with higher grades assigned to more conservative-appearing students. The lack of pro-liberal grading bias might also be explained because liberal professors (who are in the majority) do not feel threatened and therefore aren’t inclined to favor those in agreement with them.

The current study is relevant in today’s sociopolitical environment because perceptions of political bias may lead to negative consequences, even if bias does not actually exist. Perhaps the most damaging result of perceived liberal bias is the questioning of the legitimacy of higher education in America. A survey found that 58% of U.S. respondents identifying as Republican reported that higher education has a negative effect on the country (Turnage, 2020). The negative impact of the liberal bias narrative also affects individual students in classrooms. Students may react to perceptions of bias by self-censoring their political views and not fully engaging in the classroom (Kashti, 2009; Linvill and Havice, 2011) which could lead to a diminished educational experience.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this set of studies. First, we relied on research regarding characteristics of liberals and conservatives to create the student appearance manipulation (Carney et al., 2008). Based on this research, it was expected that a student with pink-hair, a nose-ring, and a colorful crocheted top would be rated as politically liberal and that a student with her hair in a bun, pearls, and business casual-wear would be seen as more politically conservative. The manipulation was effective for the liberal-appearing student, but less so for the conservative target. Future studies should implement appearance cues that more clearly denote affiliation with conservatism, such as a “Make America Great Again” baseball cap or t-shirt.

Further, one stimulus student, a white women, was employed in this research. Our findings should be interpreted within this limited scope. Research indicates that Black Americans, for example, who reference politics have lower response rates from college admissions than do those who do not mention politics (Druckman and Shafranek, 2020). The intersection of other identifying variables, such as gender and race, might meaningfully interact with political orientation to affect how professors evaluate their students. Future research should fully explore these intersections. In addition, each professor only rated one student on a short, fabricated writing assignment. This design does not accurately replicate the complex dynamics of grading many students on various assignments over an academic term. Actual grading occurs in more nuanced contexts where professors compare students, and where differences in student appearance might lead to grading bias. Future research could incorporate more realistic grading practices, perhaps by implementing classroom observations that incorporate student appearance and assigned grades. Further, future research should attempt to recruit a larger sample with an equal number of professors who identify as liberal and conservative so that results can be more reliably generalized.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: Open Science Framework (OSF) Study 2, https://osf.io/rzpek/?view_only=99f1cdabd6114e0e9317e404315a528f.

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at Washington and Lee University (Chair: Bryan Price). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

JW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahler, D. J., and Sood, G. (2018). The parties in our heads: misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. J. Polit. 80, 964–981. doi: 10.1086/697253

Bar, T., and Zussman, A. (2012). Partisan grading. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 4, 30–48. doi: 10.1257/app.4.1.30

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Block, J., and Block, J. H. (2006). Nursery school personality and political orientation two decades later. J. Res. Pers. 40, 734–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.09.005

Burmila, E. (2021). Liberal bias in the college classroom: a review of the evidence (or lack thereof). Polit. Sci. Polit. 54, 598–602. doi: 10.1017/S1049096521000354

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., and Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Polit. Psychol. 29, 807–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00668.x

Carpinella, C. M., and Johnson, K. L. (2013). Appearance-based politics: sex-typed facial cues communicate political party affiliation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.009

Druckman, J. N., and Shafranek, R. M. (2020). The intersection of racial and partisan discrimination: evidence from a correspondence study of four-year colleges. J. Polit. 82, 1602–1606. doi: 10.1086/708776

Edelmann, A., and Vaisey, S. (2023). Gender differential effect of college on political orientation over the last 40 years in the U.S.—a propensity score weighting approach. PLoS One 18:e0279273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279273

Evers, J., and Kneyber, R. (2016). Flip the system: Changing education from the ground up. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

Frankenberg, E. (2010). Exploring teachers' racial attitudes in a racially transitioning society. Educ. Urban Soc. 44, 448–476. doi: 10.1177/0013124510392780

Furnham, A., and Avison, M. (1997). Personality and preference for surreal paintings. Personal. Individ. Differ. 23, 923–935. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00131-1

Griffin, A. M., and Langlois, J. H. (2006). Stereotype directionality and attractiveness stereotyping: is beauty good or is ugly bad? Soc. Cogn. 24, 187–206. doi: 10.1521/soco.2006.24.2.187

Gross, N. (2013). Why are professors liberal and why do conservatives care? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Horowitz, D., and Laksin, J. (2009). One party classroom: How radical professors at America's top colleges indoctrinate students and undermine democracy. New York, New York: Crown Forum.

Horowitz, D., and Lehrer, E. (2020). Political bias in the administrations and faculties of 32 elite colleges and universities. Students for Academic Freedom. Available at: https://studentsforacademicfreedom.org/reports/political-bias-in-the-administrations-and-faculties-of-32-elite-colleges-and-universities/ (Accessed March 16, 2022).

Kahn, K., and Davies, P. (2017). What influences shooter bias? The effects of suspect race,neighborhood, and clothing on decisions to shoot. J. Soc. Issues 73, 723–743. doi: 10.1111/josi.12245

Kashti, O. (2009). Tel Aviv students afraid to challenge leftist professors, November 9. Available at: http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/tel-aviv-students-afraid-to-challenge-leftist-professors-1.4537 (Accessed April 2, 2014).

Kemmelmeier, M., Danielson, C., and Basten, J. (2005). What's in a grade? Academic success and political orientation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 1386–1399. doi: 10.1177/0146167205276085

Levendusky, M. S., and Malhotra, N. (2016). (Mis)perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opin. Q. 80, 378–391. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfv045

Linvill, D. L., and Havice, P. A. (2011). Political bias on campus: understanding the student experience. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 52, 487–496. doi: 10.1353/csd.2011.0056

Livingston, N., and Gurung, R. (2019). Trumping racism: the interactions of stereotype incongruent clothing, political racial rhetoric, and prejudice toward African Americans. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 24, 52–60. doi: 10.24839/2325-7342.JN24.1.52

Malloy, T. E., Dipietro, C., Desimone, B., Curley, C., Chau, S., and Silva, C. (2021). Facial attractiveness, social status, and face recognition. Vis. Cogn. 29, 158–179. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2021.1884630

Mariani, M., and Hewitt, G. (2008). Indoctrination U.? Faculty ideology and changes in student political orientation. PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 41, 773–783. doi: 10.1017/S1049096508081031

Musgrave, P., and Rom, M. (2015). Fair and balanced? Experimental evidence on partisan bias in grading. Am. Politics Res. 43, 536–554. doi: 10.1177/1532673X14561655

Olivola, C. Y., Sussman, A. B., Tsetsos, K., Kang, O. E., and Todorov, A. (2012). Republicans prefer republican-looking leaders: political facial stereotypes predict candidate electoral success among right-leaning voters. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 3, 605–613. doi: 10.1177/1948550611432770

PEW Research Center (2017). Sharp partisan divisions in views of National Institutions. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/07/10/sharp-partisan-divisions-in-views-of-national-institutions/ (Accessed October 15, 2022).

Quinn, K., Mason, M., and Macrae, C. (2009). Familiarity and person construal: individuating knowledge moderates the automaticity of category activation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 852–861. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.596

Reysen, S. (2005). Construction of a new scale: the Reysen likability scale. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 33, 201–208. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2005.33.2.201

Rohner, J.-C., and Rasmussen, A. (2011). Physical attractiveness stereotype and memory. Scand. J. Psychol. 52, 309–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00873.x

Rule, N. O., and Ambady, N. (2010). Democrats and republicans can be differentiated from their faces. PLoS One 5:e8733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008733

Saucier, D. A., and Miller, C. T. (2003). The persuasiveness of racial arguments as a subtle measure of racism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 29, 1303–1315. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254612

Strauss, V. (2017). DeVos: colleges tell students “what to do, what to say and, more ominously, what to think.” The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/02/23/devos-colleges-tellstudents-what-to-do-what-to-say-and-more-ominously-what-to-think/

Turnage, C. (2020). Most republicans think colleges are bad for the country. Why? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/most-republicans-think-colleges-are-bad-for-thecountry-why/ (Accessed October 15, 2022).

Wilkins, C. L., Chan, J. F., and Kaiser, C. R. (2011). Racial stereotypes and interracial attraction: phenotypic prototypicality and perceived attractiveness of Asians. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 17, 427–431. doi: 10.1037/a0024733

Woessner, M., and Kelly-Woessner, A. (2009). I think my professor is a democrat: considering whether students recognize and react to faculty politics. PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 42, 343–352. doi: 10.1017/S1049096509090453

Woessner, M., Maranto, R., and Thompson, A. (2019). Is collegiate political correctness fake news? Relationships between grades and ideology. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Zipp, J. F., and Fenwick, R. (2006). Is the academy a liberal hegemony?: The political orientations and educational values of professors. Public Opin. Q. 70, 304–326. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfj009

Keywords: liberal bias, political bias, grading bias, professors, higher education

Citation: Woodzicka JA, Boudreau GH and Hayne SL (2024) Do professors favor liberal students? Examining political orientation appearance cues and professor bias. Front. Educ. 9:1473967. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1473967

Received: 31 July 2024; Accepted: 30 October 2024;

Published: 13 November 2024.

Edited by:

Enrique H. Riquelme, Temuco Catholic University, ChileReviewed by:

Ashraf Alam, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, IndiaCopyright © 2024 Woodzicka, Boudreau and Hayne. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julie A. Woodzicka, d29vZHppY2thakB3bHUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.