- Department of STEM Education and Professional Studies (STEMPS), Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, United States

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is associated with adaptable, critical, lifelong thinking skills. Teachers are essential to promoting SRL in learners, yet infrequently teach these learning strategies in classrooms. We addressed three research questions: (1) How do K–5 teachers implement SRL in their teaching?, (2) How is the use of SRL strategies linked to their self-efficacy or confidence in teaching?, and (3) How do teachers differ in their use of SRL depending on school type (public vs. private)? Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 12 primary in-service teachers, sampled equally from one public and one private school, to explore their SRL practices. They frequently utilized SRL in implicit ways. Further themes included setting goals based on student needs, monitoring student progress, and thereby adapting instruction. Teachers were largely confident about incorporating SRL into their instruction. Public school participants relied on time management and tracked student progress in more summative ways than their private school counterparts.

Introduction

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is defined as an “individuals’ self-generated cognitions, affects, and behaviors that are systematically oriented toward attainment of their goals” (Schunk and Mullen, 2013, p. 363). Positive learning outcomes associated with SRL include improved academic performance and motivation (e.g., Zimmerman and Bandura, 1994; Cazan, 2013) as well as lifelong learning (e.g., Dent and Koenka, 2016; van Beek et al., 2014). Because SRL is based on a socio-cognitive theoretical framework (Bandura, 2001; Zimmerman, 2013), it has also been shown to have social and behavioral benefits, especially when present in a community of learners engaging in co-regulated or shared-regulation (Hadwin et al., 2017; Quackenbush and Bol, 2020).

The literature supports the effectiveness of metacognitive strategies and SRL. For example, Elhusseini et al. (2022) conducted a quantitative systematic review of the effects of SRL interventions on primary and secondary students’ academic achievement. These authors reported positive effects of SRL strategies on reading, writing, and math achievement among primary and secondary students. Dent and Koenka (2016) further revealed small but statistically significant correlations among metacognitive and cognitive processes for children and adolescents. Overall, these metanalytic results varied in strength depending on the grade level, subject area, measures, and particular strategies but were nonetheless significant, pointing to positive results for self-regulatory and metacognitive strategies on academic and social outcomes.

Researchers also tell us that metacognition and self-regulation occur at an early age and can be improved (Roebers et al., 2009; van Loon et al., 2021). In yet another meta-analysis, SRL, metacognitive, and motivational strategies were shown to be effective among primary school students (Dignath et al., 2008). Based on Muir et al.’s (2023) systematic review, this seems to be true even for preschool children with regards to executive functioning. These results suggest that young children can develop self-regulation and metacognitive skills, although some of this depends on whether the context facilitates SRL application.

One such contextual variable is prior achievement. In an early study, Zimmerman and Pons (1986) demonstrated distinct patterns for the frequency and consistency of SRL strategy use by student achievement level. Higher achieving students were more likely to engage in monitoring, help-seeking, organizing, transforming, and delivering self-consequences when compared to their lower achieving counterparts. More recently, Cleary et al. (2020) reported similar findings. Middle school students reporting strong SRL skills had higher mathematic achievement levels than those reporting poor SRL skills.

Instruction represents another contextual variable influencing students’ use of SRL strategies. Teachers play a critical role in supporting student SRL growth (e.g., Kramarski and Michalsky, 2009). Teacher practices of SRL are influenced by their beliefs, attitudes, and prior knowledge of SRL strategies (Karlen et al., 2020). Teachers generally hold positive feelings toward SRL practices, but they do not consistently cultivate and apply these learning strategies (Dignath-van Ewijk and Van der Werf, 2012). Additionally, while teachers find SRL strategies to be valuable in theory, some teachers believe their students are incapable of these skills (Spruce and Bol, 2015). Teachers would benefit from competently self-regulating their own learning before teaching SRL to others (e.g., Hattie and Yates, 2014). Using Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning theory (Zimmerman, 2008) and Kramarski and Heaysman’s (2021) “triple SRL–SRT processes” as a framework, we identify the ways primary teachers implement SRL, explore their self-efficacy beliefs in teaching SRL, and investigate differences in SRL use between public and private school teachers.

SRL theoretical frameworks

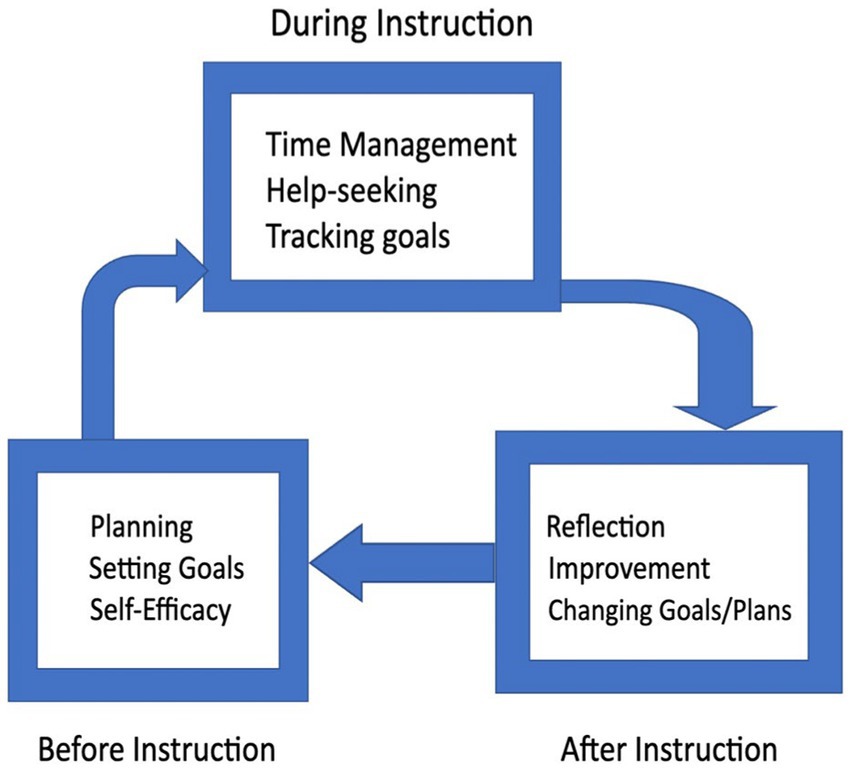

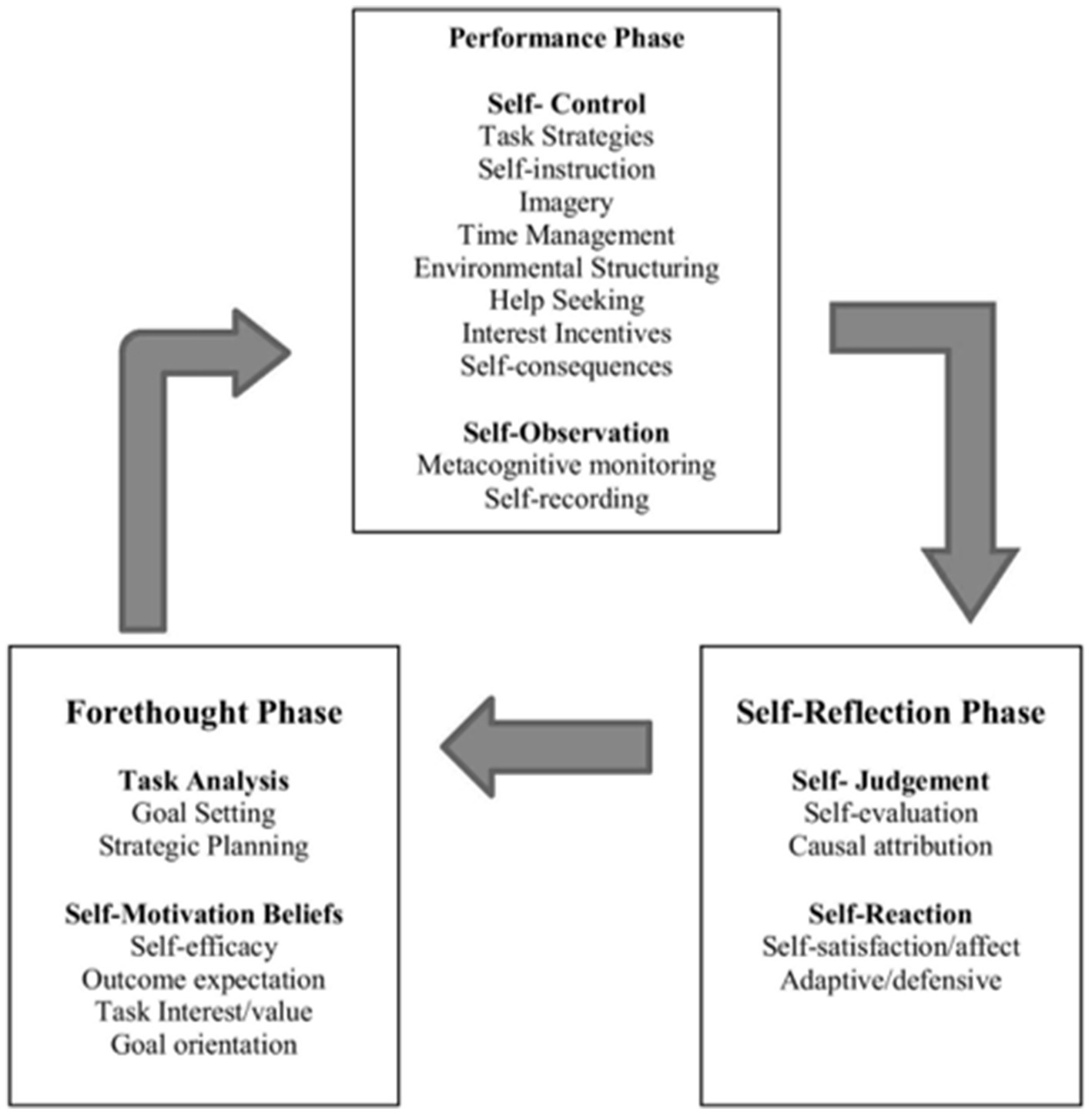

SRL is comprised of “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and cyclically adapted to the attainment of personal goals” (Zimmerman, 2000, p. 14). SRL is set in a socio-cognitive framework, as it requires internal beliefs, cognitions, and metacognitions as well as external influences including feedback and teacher support (Zimmerman, 1989). Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) cyclical model of SRL recognizes learning strategies that occur pre-performance, during performance, and post-performance of an academic task in a teaching context (see Figure 1). In the forethought phase, learners establish their objectives, evaluate their motivation and capabilities to accomplish the tasks, and devise plans to actively participate in the task at hand. During the performance phase, learners actively participate in the tasks, implementing strategies such as time management, help-seeking, and environmental structuring, monitoring their progress throughout. It is in the last phase, the self-reflection phase, wherein learners critically analyze their performance of a task through self-evaluation, fostering a deeper understanding of their own abilities and areas for improvement.

Figure 1. Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model of self-regulated learning.

Kramarski and Heaysman (2021) created a pragmatic framework that aims to connect theory, practice, and research on teachers’ SRL. Refining already existing frameworks that distinguish between teacher personal SRL use and SRL instruction for learners, the “triple SRL–SRT processes” was designed, wherein three self-regulation categories are offered: “(1) teachers self-regulate their own learning as learners (SRL); (2) teachers self-regulate their practice as self-regulated teachers (teacher-focused SRT); (3) teachers activate students’ SRL as teachers of SRL (student-focused SRT)” (Kramarski and Heaysman, 2021, p. 298). Teachers’ beliefs, knowledge, and practices seem intertwined and could affect all three categories of the Triple SRL-SRT framework.

Teachers and SRL

Teacher beliefs and knowledge of SRL influence how teachers integrate SRL in their teaching (Calderhead, 1991; Hoy et al., 2006). Teacher beliefs and knowledge are closely related concepts, often difficult to isolate as they are interwoven (Hoy et al., 2006; Pajares, 1992). Teacher understanding of SRL can be categorized in the following ways: the beliefs and knowledge teachers carry about practicing SRL instruction and their beliefs and knowledge of how to construct an environment conducive to supporting SRL development (Dignath-van Ewijk and Van der Werf, 2012).

Teacher SRL beliefs

Teacher beliefs have been found to have the strongest impact on teacher SRL behavior, due to their affective nature that takes prominence when cognitive reasoning is not successful (Pajares, 1992). Teachers largely believe that SRL strategies should be developed in their students (Perry et al., 2008). However, while teachers find SRL strategies to be valuable in theory, some teachers believe that these skills are not transferable to their own students, due to their perceptions of student capability and other factors (Spruce and Bol, 2015).

Dignath (2016) identified three types of teacher beliefs related to SRL: epistemological beliefs, beliefs on SRL promotion, and self-efficacy beliefs. Epistemological beliefs include beliefs on knowledge, such as learning theories and systems (Schommer-Aikins, 2004; Perry, 1970). Beliefs on SRL promotion include the perceptions of instructional SRL-related pedagogy (Lombaerts et al., 2009). Self-efficacy beliefs regarding teacher SRL are the beliefs a teacher holds on their capability and effectiveness for providing SRL-related instruction (Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2001).

Teacher self-efficacy beliefs

Self-efficacy is a prominent component of Bandura’s (2001) socio-cognitive theory that describes an individual’s belief in their ability to reach a learning goal. Situated in the forethought phase of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model, self-efficacy is categorized as a self-motivational learning factor that occurs prior to a task or experience. One’s self-efficacy beliefs can influence their utilization of SRL in the performance and self-reflection phases, including their monitoring and evaluation skills (Pajares and Usher, 2008).

Teacher self-efficacy is defined as a “teachers’ individual beliefs about their own abilities to successfully perform specific teaching and learning tasks within the context of their own classrooms” (Dellinger et al., 2008, p. 751). SRL self-efficacy is one factor that determines the degree of SRL facilitation by teachers, as it directly influences their likelihood for promoting these learning skills in their practice (Dignath, 2016). Teacher perceptions of SRL influence their self-efficacy to apply these learning strategies (Hoy et al., 2006). Unfortunately, while many instructors hold positive beliefs regarding the benefits of SRL, they lack the confidence to pursue SRL-related instruction in the classroom (Perry et al., 2008).

Teacher SRL knowledge

Teachers’ beliefs in the usefulness of SRL are widely positive, but their actual working knowledge of these strategies is generally low (Spruce and Bol, 2015). Teacher SRL knowledge is particularly weak in the forethought phase of planning and the self-reflection phase of evaluation (Spruce and Bol, 2015). Novice teachers in particular lack knowledge of how students learn (Askell-Williams et al., 2012) and are less likely to facilitate SRL as a result (Butler and Cartier, 2004). Teachers who have comparable knowledge of SRL may exhibit differing instructional behaviors that vary in effectiveness (Dignath-van Ewijk and Van der Werf, 2012). Teacher knowledge and beliefs about SRL and its effectiveness should logically affect their SRL practices.

Teacher SRL practices

Although educators have many opportunities to develop student SRL strategies in the classroom (de Boer et al., 2018; Azevedo et al., 2008), they infrequently implement these fundamental learning skills (Dignath and Büttner, 2018). There is a misalignment between teacher SRL beliefs, knowledge, and practice (Spruce and Bol, 2015). Teachers often lack the skills to integrate SRL into their practices (Dignath and Büttner, 2018) and fail to consistently cultivate and apply these learning strategies as a result (Dignath-van Ewijk and Van der Werf, 2012). While SRL encompasses cognition, metacognition, affect, motivation, and behavioral processes (Zimmerman, 1990; Schunk and Green, 2018), teachers most commonly promote cognitive learning strategies and rarely incorporate other SRL-related competency development in their instruction (Dignath and Veenman, 2021). When SRL is incorporated into instruction, it tends to be more implicit rather than explicit in nature.

Implicit versus explicit SRL instruction

As noted, SRL is primarily taught implicitly (Kramarski and Michalsky, 2015; Spruce and Bol, 2015) despite the research that students benefit the most from explicit SRL instruction (Kistner et al., 2010; Dignath and Büttner, 2018). Throughout daily classroom instruction, there are myriad opportunities for the explicit teaching of SRL strategies (Azevedo et al., 2008). Explicit teaching of SRL is the direct instruction and modeling of what specifically these strategies are, why they are beneficial, and how and when to utilize them in a learning context (Zimmerman, 2008; Dignath and Veenman, 2021). Explicit instruction of SRL components differs based on their associated SRL phase (Michalsky, 2021). Teachers more often explicitly teach metacognitive monitoring skills and less frequently focus on strategic planning and evaluation (Quackenbush and Bol, 2020), despite evidence on the effectiveness of less frequently taught SRL components such as task analysis and self-evaluation on academic achievement (Michalsky, 2020). Reflection is the most common SRL strategy used by novice teachers to improve upon their explicit SRL practices (Kohen and Kramarski, 2012; Kramarski and Michalsky, 2010). Some of these SRL practices may be influenced by the type of school in which a teacher is employed. SRL practices may differ in terms of the flexibility or latitude teachers have in their schools. One potentially important difference relates to whether the teachers are employed in private versus public school.

SRL and school type

School climate is a strong indicator of the degree and quality of SRL promotion and application in the classroom (De Smul et al., 2019). Some facets of school climate differ between public and private school types (Lubienski et al., 2008). Private schools generally allow for greater teacher autonomy and flexibility in curriculum, for instance (Miron and Nelson, 2002). A study by Fidan and Öztürk (2015) concluded that attributes such as creativity and intrinsic motivation have been found to be more prevalent in private school teachers. They additionally discovered that private schools are more supportive of innovation and have greater access to resources that enhance innovation. As researchers consider SRL an “innovative practice” (Lombaerts et al., 2009), and given the curricular flexibility and autonomy experienced by private school teachers, it would be interesting to understand the differing ways in which SRL concepts are promoted in private versus public schools.

Overall, when a school’s educators share knowledge and perspectives of SRL and are guided by the same framework of SRL and its strategies, they are more likely to implement SRL in their practice (Vandevelde et al., 2012; Peeters et al., 2016). While no previous research has compared SRL development amongst public and private elementary schools, overall, studies have found that private schools receive more administrative support than public schools (Lubienski et al., 2008). When people in leadership positions such as district administrators and principals advocate for SRL use in teacher practice, a school climate is cultivated that supports the utilization of SRL strategies (James and McCormick, 2009). Given these findings, private school teachers are better positioned due to the autonomy and supports they receive to develop SRL skills and strategies. This research study addresses the ways in which SRL is implemented in public and private school environments.

Overview and rationale for present study

Based on Kramarski and Heaysman’s (2021) typology of teacher SRL, we focused mostly on how teachers self-regulate their practice as self-regulated teachers. However, we regard the three types of teachers’ SRL as intertwined. That is, we would expect that teachers who self-regulate their own learning and instruction would be better equipped to promote SRL among their students. Although we emphasized teachers’ practice of SRL, we also explored their knowledge and familiarity as well as their self-efficacy for SRL. The most studied components of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) SRL model and those most familiar to teachers were chosen for our study (Spruce and Bol, 2015). From the forethought phase, the variables of emphasis were goal setting and strategic planning, subcomponents of task analysis. From the performance phase, time management was a subcomponent of interest, as were metacognitive monitoring and self-recording, subcomponents of self-observation. The self-reflection phase was represented with causal attribution and adaptive reaction, subcomponents of self-judgment and self-reaction, respectively. Several components incorporated into the present research were further selected due to the explicit nature of these strategies, such as help-seeking, which could be recognized through social interactions, and time management, which may be more salient due to measuring tools such as clocks and timers. Metacognitive monitoring is another SRL strategy that teachers can understand via feedback, gradebooks, and other student progress evaluation techniques (Halpern, 1998). Teacher self-efficacy for promoting explicit and implicit SRL strategies in classrooms was an additional area of interest. It is important when considering teacher SRL perspectives to understand their confidence in teaching these skills and making connections with teacher knowledge and beliefs of SRL.

Pre-service teachers are often the focus of studies on the effectiveness of SRL interventions (e.g., Glogger-Frey et al., 2018). Professional development at the pre-service level brings awareness of SRL strategies and demonstrates their relevance to instruction and student learning before a teacher enters the workforce, reinforcing the importance of these skills (Vosniadou, 2019). Some researchers specifically select pre-service teacher participants to understand the effectiveness of SRL professional development on novice educators at the beginning of their training (Panadero, 2017). However, pre-service teachers are selected largely because they are a more easily accessible population (Cebesoy, 2013). We address this gap in the literature by exploring the SRL-related teaching practices of in-service teachers. It may be the case that professional development and intervention studies be designed differently for pre-versus in-service teachers. Exploring the practices of in-service teachers via interviews may be an initial step in tailoring professional development.

Aligning with recommendations to enhance teachers’ SRL, self-efficacy for teaching, and instructional effectiveness (Spruce and Bol, 2015; Panadero et al., 2017), the present study investigates in-service teachers’ use of SRL strategies in K–5 contexts and how it is linked to teaching self-efficacy and instructional effectiveness. The study further seeks to make comparisons between SRL practices of public and private school teachers. Exploring teacher SRL practice and efficacy beliefs will help us construct a picture of how SRL is being utilized in varied educational settings. The following research questions guide this study:

1. How do K–5 teachers implement SRL in their teaching?

2. How is the use of SRL strategies linked to their self-efficacy or confidence in teaching?

3. How do teachers differ in their use of SRL depending on school type (public vs. private)?

Understanding teacher perceptions and SRL practices can be useful in finding ways to utilize effective SRL strategies in the classroom and promote self-efficacy around SRL instruction. The present study contributes to existing literature by targeting in-service teachers and making connections between their beliefs, knowledge, and self-efficacy regarding SRL to their own SRL practices. Additionally, this study is the first we know of to compare SRL practices between public and private school settings.

Method

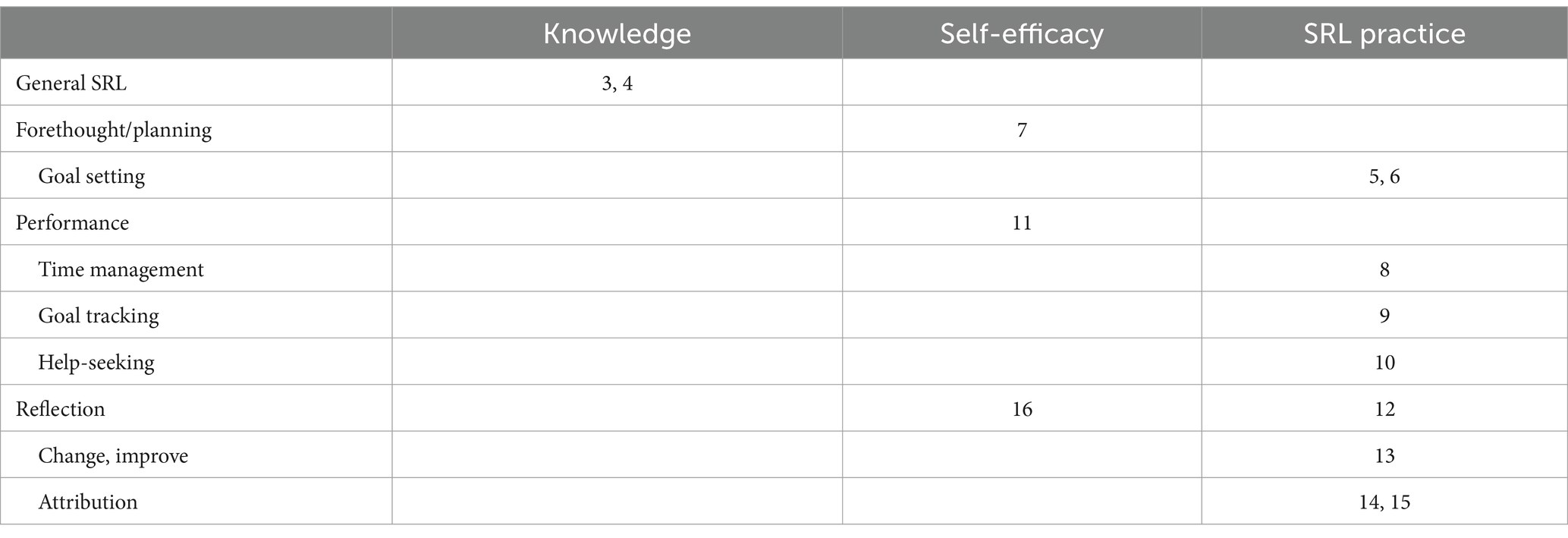

A qualitative interview study was designed to examine teachers’ use of SRL strategies in K–5 contexts. A consultation of qualitative methods texts (e.g., Muljana and Luo, 2023; Katsantonis and McLellan, 2023) and other published studies in the area of SRL (e.g., Brady et al., 2024; Russell et al., 2022) point to the legitimacy of using just one qualitative data collection technique, like interviews, in qualitative research. One-on-one structured interviews were conducted with primary school teachers to understand their knowledge and practice of SRL strategies. The interview protocol was drafted to incorporate all phases and selected subcomponents of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model of SRL. The selected components from the broader framework were described earlier and are presented in Figure 2.

Participants

Participants included 12 in-service primary school teachers (K–5). Six participants were employed at a public charter school, and six participants taught at a private school, both located in Southern California. Of the sample, three teachers were male and nine were female. The number of participants in our sample seemed appropriate to achieve in-depth exploration of the phenomenon via a qualitative design (Moustakas, 1994; Clandinin, 2006).

Years of teaching experience amongst participants ranged from 3 years to 16 years. Our selection criteria required that participants are in-service teachers with at least 3 years of teaching experience at their current school. In the interest of addressing gaps in the research, in-service teachers were the study focus. Similarly, K–5 educators were our sample of interest as elementary level educators are infrequently the population utilized for research in this context (Xu et al., 2022). Participants were recruited in equal numbers from one private and one public school in southern California, resulting in a homogonous sample.

Purposive sampling was implemented to select participants based on our specific criteria. Purposive sampling is a nonprobability sampling technique commonly used when research does not aim to generalize results (Etikan et al., 2016). Qualitative research benefits from purposive sampling due to the rich information collected from individuals targeted based on their experience with the phenomenon of focus (Patton, 2002; Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011).

Interview protocol

A semi-structured interview protocol (see Appendix A) was designed by a team of four educational psychology specialists to explore teacher perceptions and knowledge of SRL as it applied to their practice. This constituted expert review and enhanced the content validity of the interview instrument. The protocol design was informed by comprehensive systematic reviews of current literature on SRL that suggest all phases be incorporated into SRL study designs (Dunlosky and Rawson, 2019; Heikkinen et al., 2023). For the present study, components from the forethought, performance, and self-reflection phases of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model were selected so that each phase was represented in the interviews. A blueprint was designed to guide the development of the interview questions and to further strengthen content validity (see Table 1). Several rounds of revisions were made as a team and questions deleted to create a parsimonious protocol that featured SRL components relevant to the research questions and commonly understood by teachers. Response burden was also a consideration in drafting the final list of questions. From a total of 15 open-ended interview questions, three questions were associated with the forethought phase, four questions represented the performance phase, and five questions explored self-reflection. Two general questions were additionally included to understand teacher perspectives of SRL as a broader construct and were posed at the beginning of the interview before the description of the SRL model. The interview was piloted with two teachers prior to study commencement, as an additional method for strengthening the trustworthiness of findings. Few changes were incorporated based on responses to the pilot interviews and resulted in minor rewording and estimations of interview length.

Procedure

Upon receiving university IRB and school approval, teachers were informed of the study and asked to participate. Over the course of 8 weeks, 12 teachers were individually interviewed over one session either in person on their school campus or via video conference. Participants were informed that they would be recorded and provided their consent prior to interview commencement. The length of each interview session was approximately 30–40 min in duration. All interviews were recorded using Zoom video conference for future reference and to facilitate transcription.

Data analyses

Data was initially analyzed through a first-cycle a priori coding process that took a deductive approach by using pre-defined codes based on the subcomponent SRL targets (Saldaña and Omasta, 2016). Deductive coding uses an existing theory or framework, (in this case SRL theory), to determine the set of codes that will guide the data analysis (Bingham and Witkowsky, 2021) (See Appendix B, C for codebook samples). Following the first round of coding, we interpreted the data by adding new codes, utilizing an inductive coding approach to apply meaning to the data, and identifying broad emerging themes and categories (Saldana, 2013; Bingham and Witkowsky, 2021). An iterative process was used to switch between deductive and inductive coding to capture a comprehensive picture of the phenomenon. Iterative coding “involves moving back and forth between concrete bits of data and abstract concepts, between inductive and deductive reasoning, and between description and interpretation” (Merriam, 1998, p. 178). A second-cycle thematic coding process was conducted by grouping topics into categories and labeling a new code to each grouping that illustrated thematic patterns found in the data (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Thematic analysis of data highlights the salient themes present within a phenomenon (Daly et al., 1997). We further examined themes that emerged across categories that informed our interpretation of findings.

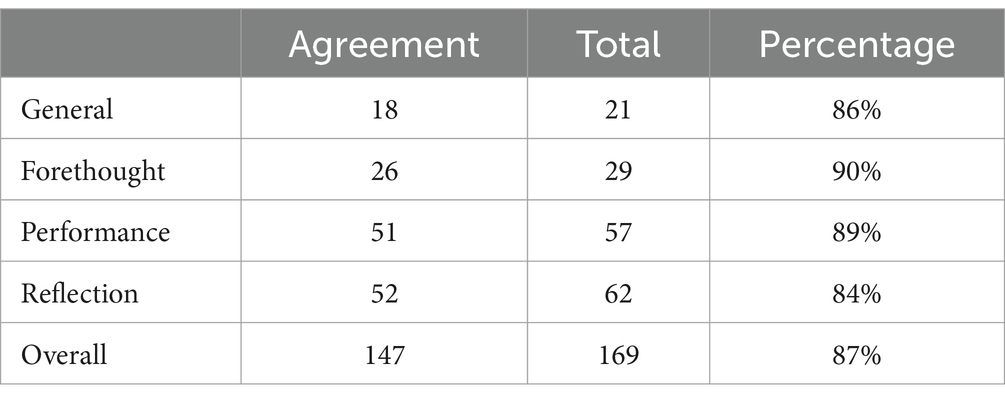

The unit of analysis was the topic or idea conveyed and not the number of teachers. For example, a teacher could have described two distinct ideas in response to one question and it would be coded into two categories. Two researchers coded the interview responses independently, using random selection with replacement to check reliability. During this process, two coded transcripts from each school (n = 4) were randomly chosen per interview question to confirm the accuracy of their themed codes throughout. The researchers addressed inconsistencies in their interrater agreement levels by consulting one another and offering clarification until a consensus was reached, followed by another round of recoding and another reliability check. Agreement on the number of topics or ideas were included in the calculations. The results of the reliability check were an overall inter-rater reliability score of 0.87 (Table 2). We calculated separate reliabilities by phase that ranged from 0.84 for Reflection to 0.90 for Forethought.

Results

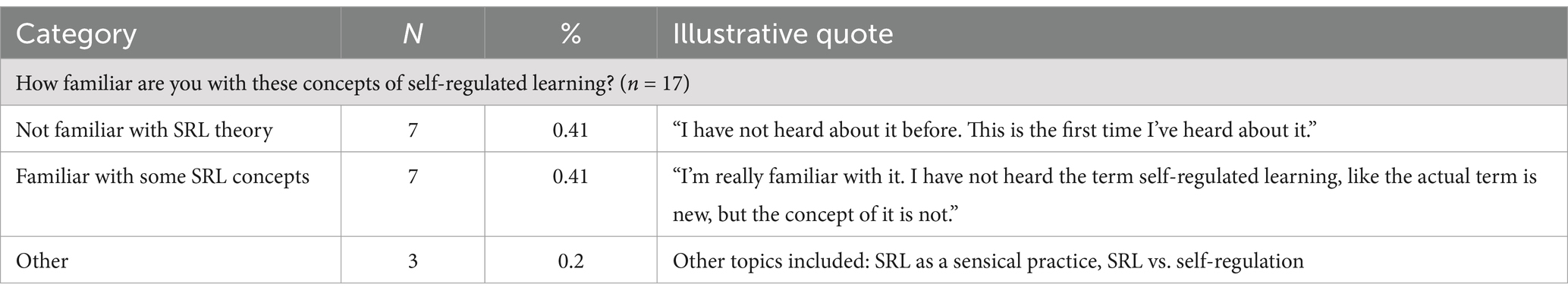

Our results are organized around the research questions. We begin with teacher SRL practices, move to our findings related to self-efficacy, and then discuss some patterns observed when comparing private versus public school teachers. As previously noted, to understand the degree of awareness each teacher had on the phases and components of SRL, an interview visual (see Figure 2) was shown to each participant prior to the first question. The opening questions were posed in conjunction with the Figure as an advance organizer and way to familiarize participants with language to be used in interviews. In correspondence with the interview visual that outlined salient aspects of SRL, participants were asked about their familiarity with self-regulated learning (Table 3). Many responses reflected teachers’ unfamiliarity with SRL (41%). One educator stated that she is “not super familiar on specifically self-regulated learning.” Another teacher said, “This is the first time I have heard about it.” In contrast, others asserted they had heard of the term and were familiar with SRL or at least some of its more common components, such as time management, reflection, and goal setting (41%). “I have not heard the term self-regulated learning, like the actual term is new but the concept of it is not.” A few responses were categorized as “other” because teachers said they were more familiar with self-regulation as a strategy for controlling one’s own behavior, or they thought that SRL was simply common sense. These findings are in line with prior research that suggests teacher SRL knowledge is limited, particularly prior to SRL training (e.g., Spruce and Bol, 2015).

Teacher SRL practices

Our first research question investigated teacher SRL practices. As an SRL theoretical framework was used to guide the study and design the interview protocol, it seemed appropriate to present the findings as they relate to each of Zimmerman’s (2002) phases. We begin with forethought, or how teachers plan their instruction, especially as it relates to goal-setting (Zimmerman, 2012).

Forethought

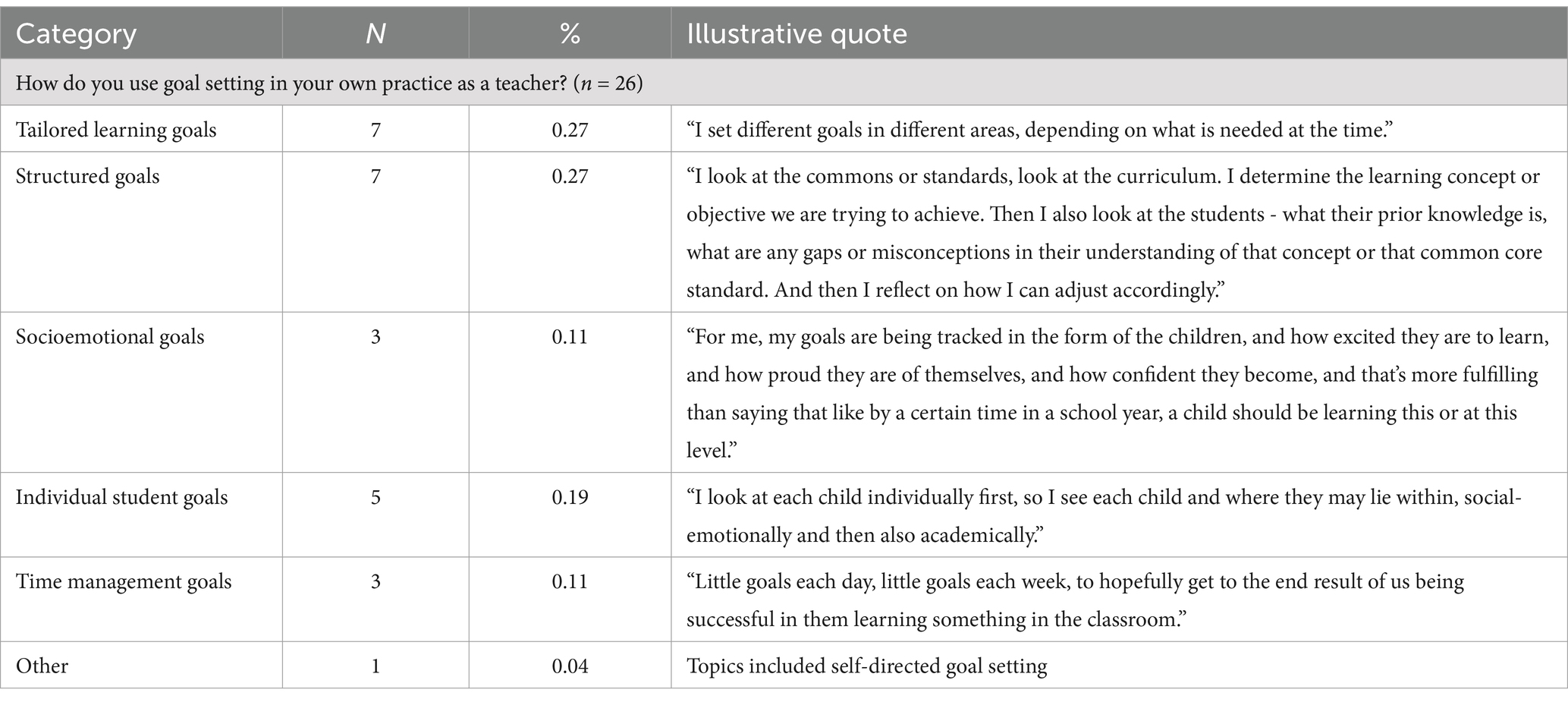

Teachers were asked to respond to questions related to task analysis in the forethought phase, such as goal setting and planning (see Table 4). Teacher goals often include learning outcomes and milestones used for self-evaluation, “a criterion against which to assess, monitor, and guide cognition” (Pintrich, 2000, p. 457). Teachers generally believe that goal setting is valuable and that it can improve their teaching (Camp, 2017), a belief our teacher participants shared across the board. A study by Hagger and Malmberg (2011) identified the following teacher professional goal categories: personal goals, teaching tasks, goals for students, and impact. When inquiring about how our teachers use goal setting in their practice, salient themes generally fell into the “goals for students” or “teaching tasks” categories, and included structured goals, classroom management goals, time management goals, socioemotional goals, individual student goals, and whole group learning goals. These goals were mostly formulated in the forethought phase, before a learning task begins, although several goals (such as goals centered around improving instruction) were a product of reflection and resulted in adaptations to their practice. One teacher commented, “If something really, truly did not work in that class, I adapt it for the next class, and if it does not work over a couple of classes, I just scrap it completely.”

Of Hagger and Malmberg (2011)‘s professionally-related teacher goal areas, we found that our participants largely focused on student goals and goals regarding the impact their own behaviors and practices had on student academic and socioemotional performance. Most of the participants (27%) stressed the importance of tailoring learning goals to meet the needs of the students. Some of these goals were directed at individual students and others were more collective and broader. One educator stated she used common core standards, expressing, “I determine the learning concept or objective we are trying to achieve.” Another 27 percent relied on structured goals supported by student assessment data and being “more reflective of my own learning goals.” One teacher referenced socioemotional goals, stating that “my goal is also mainly for my students to feel good about themselves as learners.” Regarding relationships with students and their families, a teacher mentioned, “Another goal is to make sure that my families feel that I am supporting them and feel that they are getting an education that is top notch…I want them to like feel like they are getting the best service that they can.”

Widely, our teacher participants focused on student-centered goals, a finding corroborated by Hagger and Malmberg (2011) who found that student performance is a primary goal of teachers. However, several goals focusing on teacher wellness or teaching position were noted. Regarding personal goals cited by Hagger and Malmberg (2011), one teacher mentioned a goal to strike a work-life balance, commenting,

It’s gotten to the point where my kids will be like, can you please close your laptop and come play with us?… If I close my computer at 4 0’ clock, the only person who will suffer is me and my students, because then the teaching’s not intentional.

Another teacher mentioned administration-mandated goals that teachers were required to work toward and would be assessed upon.

According to Zimmerman (2012), this planning and goal setting is adaptive and sets the stage for instruction. However, the findings regarding the various types of goals raise the question of whether and how goals align with different purposes. For example, teachers would develop a goal to target individual learning needs and another to enhance socio-emotional development. It may be that goal setting be based on assessments of students in different areas.

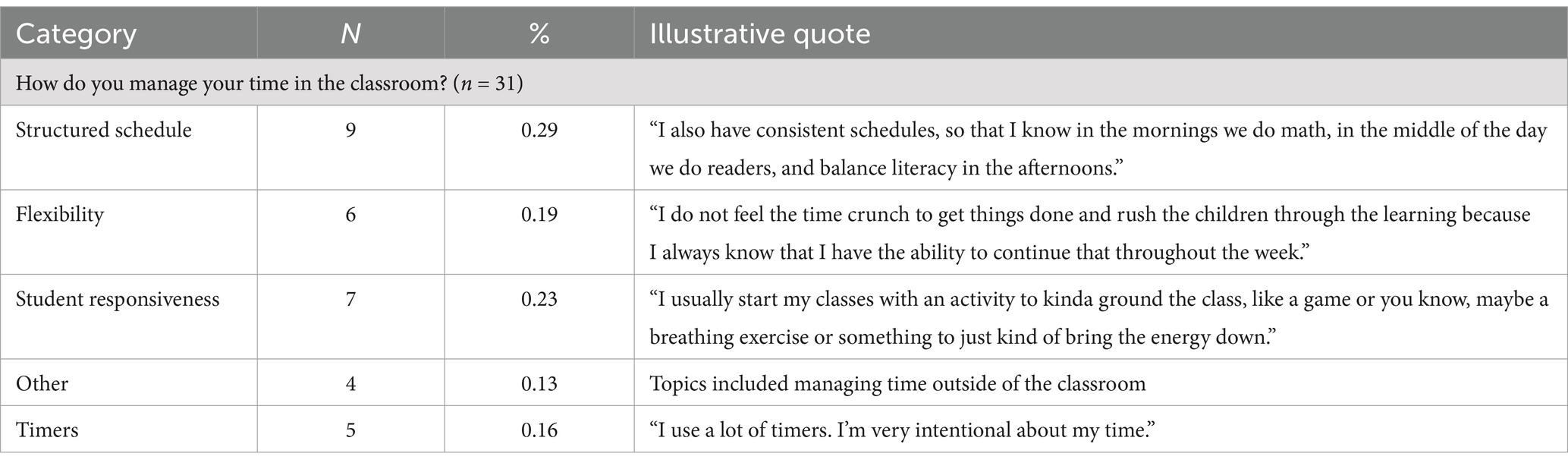

Performance

The next questions were grounded in the performance phase of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model, focusing on learning strategies that occur during instruction. We began by asking teachers how they managed their time during instruction (see Table 5). Emerging time management themes included structured schedules, flexibility, and use of timers. Most participants agreed that the key to time management was consistency in the form of daily schedules and time blocks per subject (29%). Other responses reflected use of an advance organizer or some other activity to keep the students on track and manage the classroom (23%). “I usually start my classes with an activity to kind of ground the class.” Some participants mentioned the need for flexibility in their schedules to adjust lessons based on student needs (19%). These findings align with a study by Khan et al. (2016) who discovered a positive relationship between teacher time management and classroom performance. One teacher stated, “I approach [instruction] with a certain amount of flexibility. So, I have my ideal [schedule], but I’m very open to, if this is not working, how do I shift?” Actual timers were also used to monitor time during instruction (16%). Overall, teachers had a positive view on time management and utilized time management strategies in their practice.

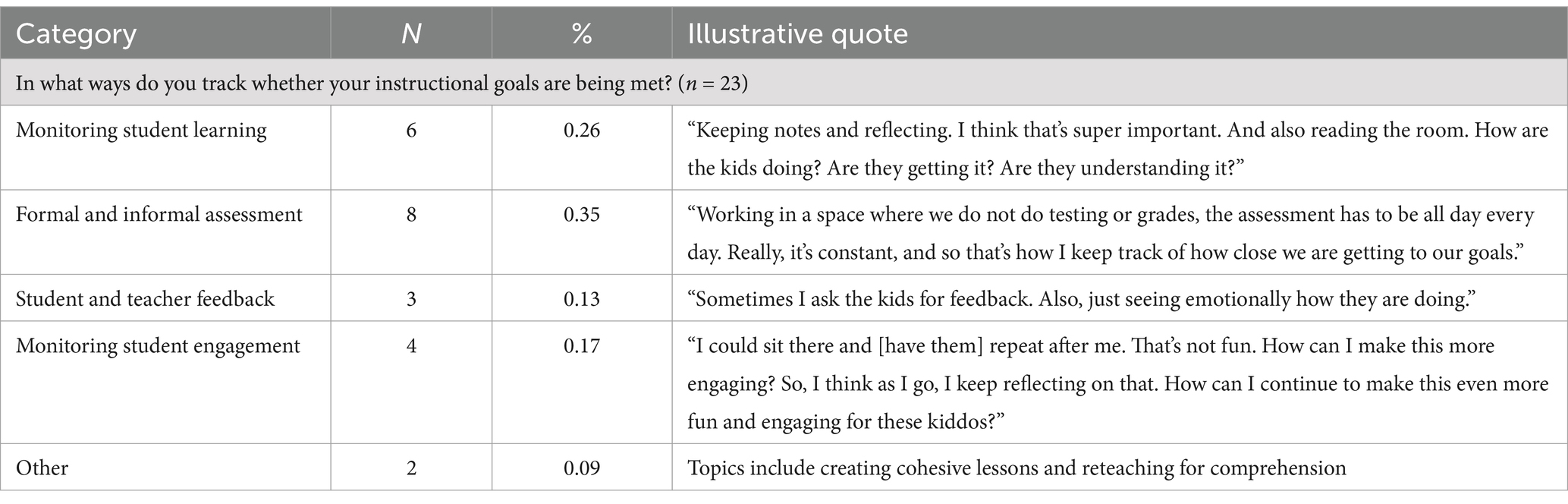

When asked how they track whether their instructional goals are being met, teachers offered a wide array of responses (Table 6), such as through formal and informal assessments (35%), by monitoring student learning (26%) and their engagement (17%) during instruction. The following overarching themes were identified: monitoring learning, monitoring engagement, teacher reflection, feedback, and assessment. Regarding assessments, one teacher in the private school group explained they do not do formal student testing, but assessment was “constant and so that is how I keep track of how close we are getting to our goals.” Another relied on feedback, particularly from their students (13%). One participant noted, “I find that the feedback from the children is the best way in [tracking instructional goals]. How they are understanding material, how they are working with the material, how they respond to the material.”

Simultaneously, student SRL can be developed through teacher feedback, particularly scaffolding feedback that promotes metacognitive strategies, promotes motivation to learn, and enhances self-efficacy for SRL use (Guo and Wei, 2019). Teacher feedback influences how learners monitor, evaluate, and adapt their learning performances (Zheng, 2022). Several teachers spoke about the goals they set for providing student feedback. One teacher said that they “give them that on-demand, on-the-spot feedback and send them back. They’ll do it and come back, ideally. Realistically, it does not always happen.” She explained that giving immediate feedback was often a challenge due to the constant flood of distractions or classroom happenings that have to take priority. Another teacher commented,

My own personal teaching goals for my own practice have been related to student assessment and providing student feedback in a much more regular and predictable way to my students, because I feel like that’s another way that I can really work with that gap is by providing them feedback much more immediately, and deciding on how to intervene sooner than what I think I’ve done in the past.

Teacher feedback is essential for student learning, reducing the gap between what students understand and what they seek to achieve (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). Ultimately, our teacher participants set explicit student feedback goals and believed in giving immediate feedback but recognized that there were limitations and challenges in doing so.

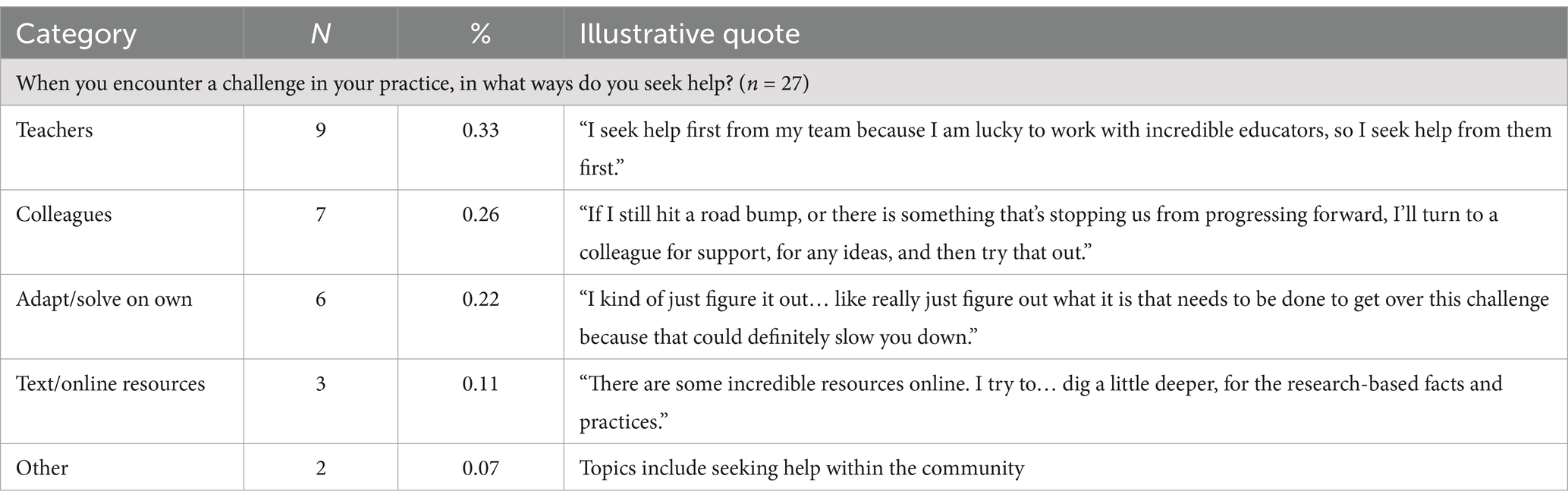

In addressing our question on help-seeking, the teachers described where they go for support when encountering a challenge (see Table 7). Emerging themes for teacher help-seeking sources included teacher colleagues, administration, field experts, content resources, and adapt/solve on own. Largely, our participants sought help from other teachers (33%), a finding corroborated by similar research studies on teacher help-seeking (e.g., Tatar, 2009). Our participants also sought help from other colleagues like administrative team members and support staff (26%). “I seek help first from my team because I am lucky to work with incredible educators.” Others explained that they prefer to troubleshoot problems on their own and adapt accordingly before seeking the help of others (22%). A smaller percentage of responses focused on using text or on-line resources (11%). “There are some incredible sources on-line. I try to … dig a little deeper for the research-based facts and practices.”

Again, help-seeking is an adaptive learning strategy that promotes goal-oriented behaviors (Ryan et al., 2005). While there is a gap in the research on in-service teacher help-seeking behaviors (e.g., Butler, 2007), we offer a definition of teacher help-seeking based on Ryan and Pintrich’s (1998) interpretation, contextually set in educational environments. Teacher help-seeking is a problem-solving behavior through which a teacher seeks external knowledge or support from a competent individual, group, or other resource when faced with an obstacle or challenge. Butler (2007) discovered that teachers hold positive beliefs about the benefits of teacher help-seeking behavior. She further found that teacher perceived help-seeking is positively associated with mastery goal orientation for teaching. Examining teacher help-seeking behavior from Kramarski and Heaysman’s (2021) triple SRL–SRT model, we found that our teacher participants seek help to improve their own learning and teaching but did not purposefully model help-seeking behaviors to their students. This may be due to the lack of knowledge teachers hold on SRL strategies and their benefits on student learning growth (e.g., Spruce and Bol, 2015). It is notable most teachers did not express reluctance to seek help in contrast to students who may be reluctant. Some studies show that students avoid help-seeking to conceal their weaknesses or are disengaged from content and lack motivation to seek help (Marchand and Skinner, 2007). As students are generally unfamiliar with SRL strategies such as help-seeking and are unable to properly utilize them without implicit or explicit teaching (Peverly et al., 2003), it may be beneficial for teachers to actively model help-seeking behaviors in their classrooms (Bandura, 1972).

Self-reflection

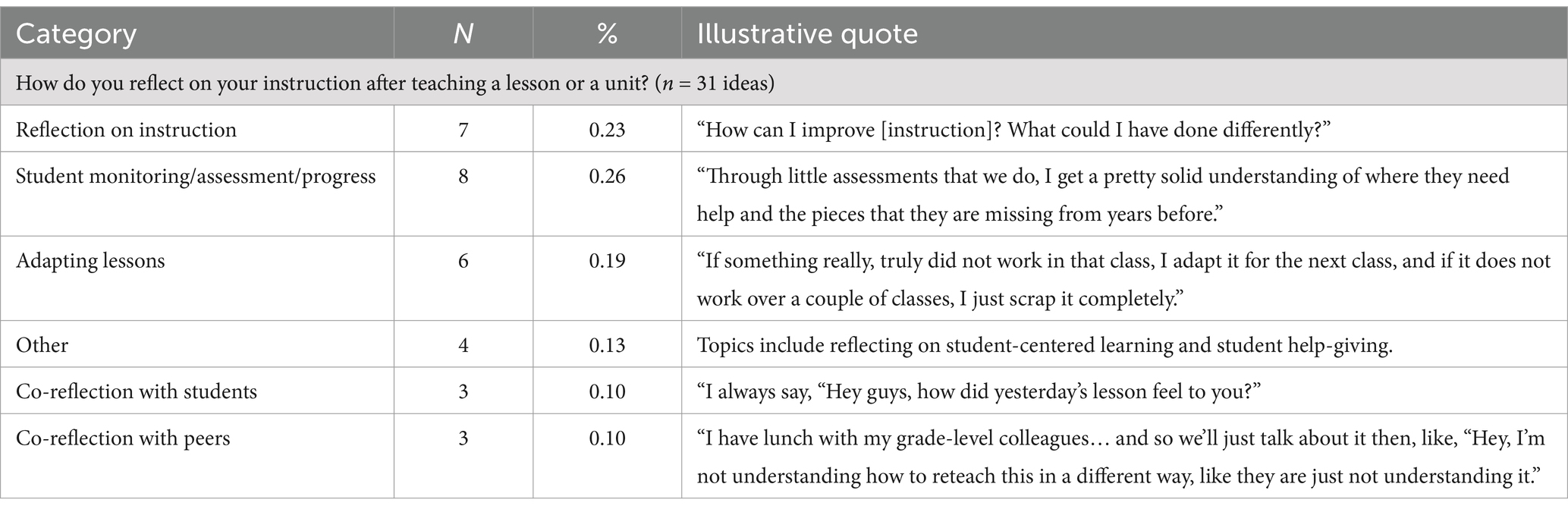

When asked about self-reflection as it relates to their practice, the teacher participants responded that they frequently used this SRL strategy to improve upon their instruction (see Table 8). Teachers self-reflect by collecting data on their practices and evaluating whether their practices coincide with their beliefs (Farrell, 2007). Upon coding the self-reflection items, the following thematic categories were formulated: reflection on instruction, co-reflection, reflection on student progress, and adapting lessons based on reflection. One participant elaborated on the ways she uses reflection after daily instruction.

I like to go through a checklist of things I did to prepare before the lesson, [and reflect on] how the actual lesson went… and then how the children received that information, and just to see if they enjoyed themselves, if they learned the material, if it was an engaging experience.

They acknowledged their reliance on reflection to adapt future lessons and meet the individual and collective needs of students. In addition to reflecting on their own, teachers co-reflect with their students and peers (15%) to understand how lessons are being received and their improvement. “Once I have reflected on a lesson, I’ll go back and make a change, then I also introduce that discussion with my students so they can also have that understanding as well.” Teacher participants typically self-reflected naturally through their cognitions. Among the interviews, there was no mention of explicit reflection-generating activity use, such as journaling or recording analysis of their lessons, which have been found to be effective reflection strategies (Jaeger, 2013).

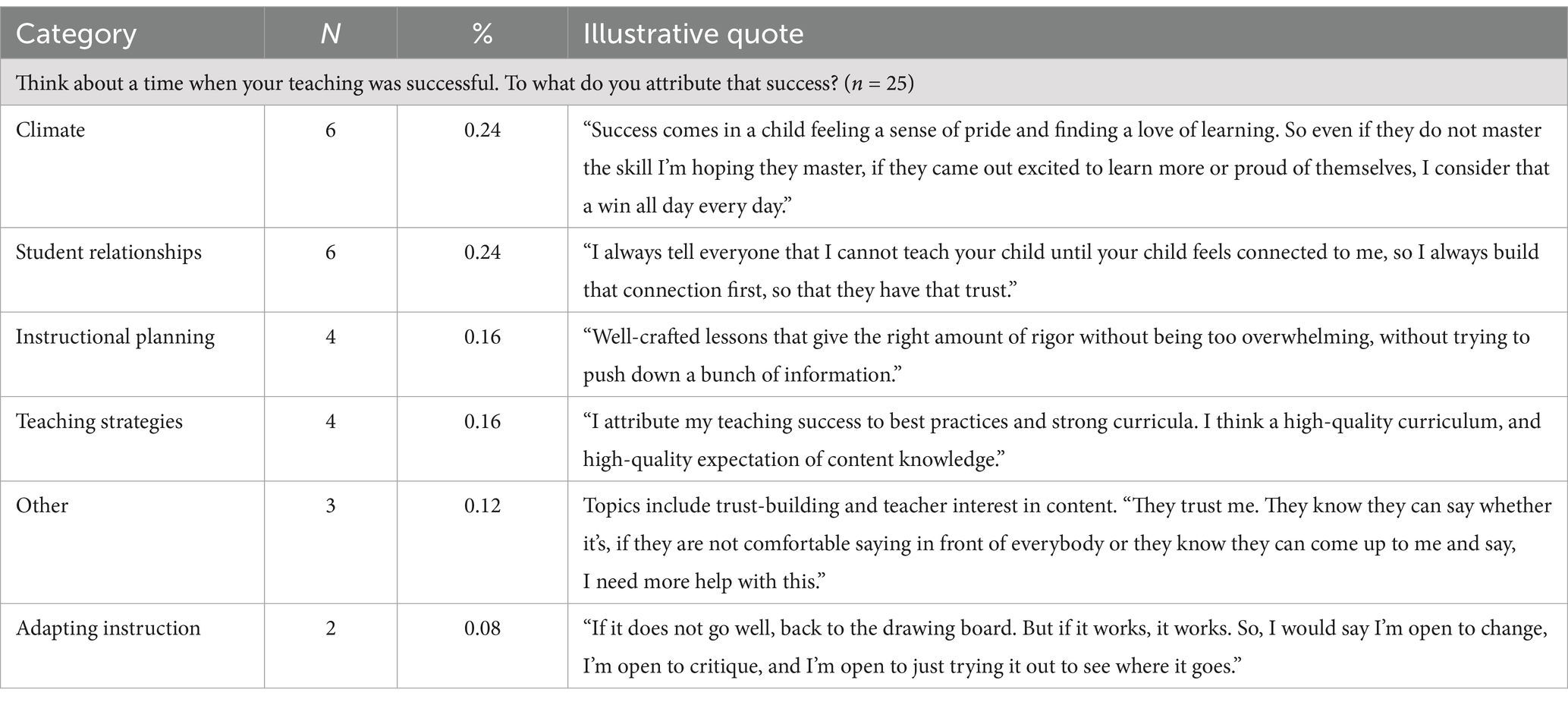

We further delved into reflection by asking teachers to think about a time when their teaching was successful and to what they attributed that success (see Table 9). Two inter-related categories emerged. The first was the attribution of success to careful instructional planning and competence by implementing effective teaching strategies. Others responded that their success could be attributed to climate in a broad sense (24%). One teacher described a climate of student pride and confidence in learning. Other teachers described the import of relationships with her students (24%). “I always tell everyone that I cannot teach your child until your child feels connected to me, so I always have that connection first, so they have that trust.” A sense of belonging enhances academic performance and cultivates student wellbeing and engagement (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2006; Dweck, 1999). However, teachers often feel constrained by structured schedules and other job-related pressures that impede their ability to strengthen their relationships with students (Allen et al., 2021).

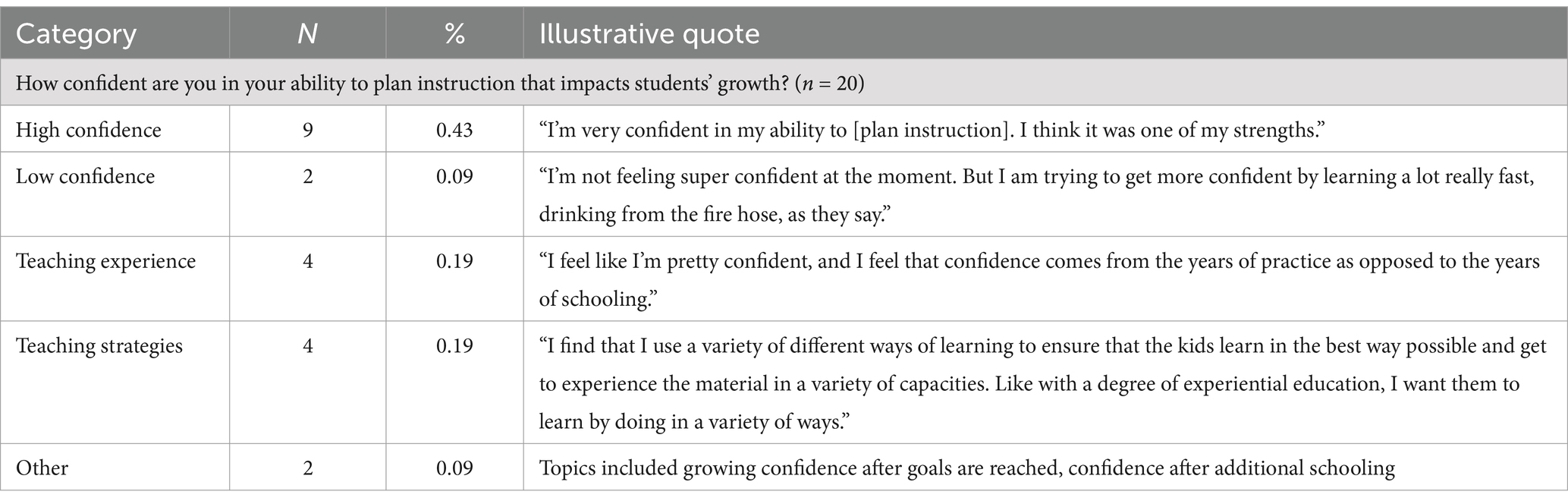

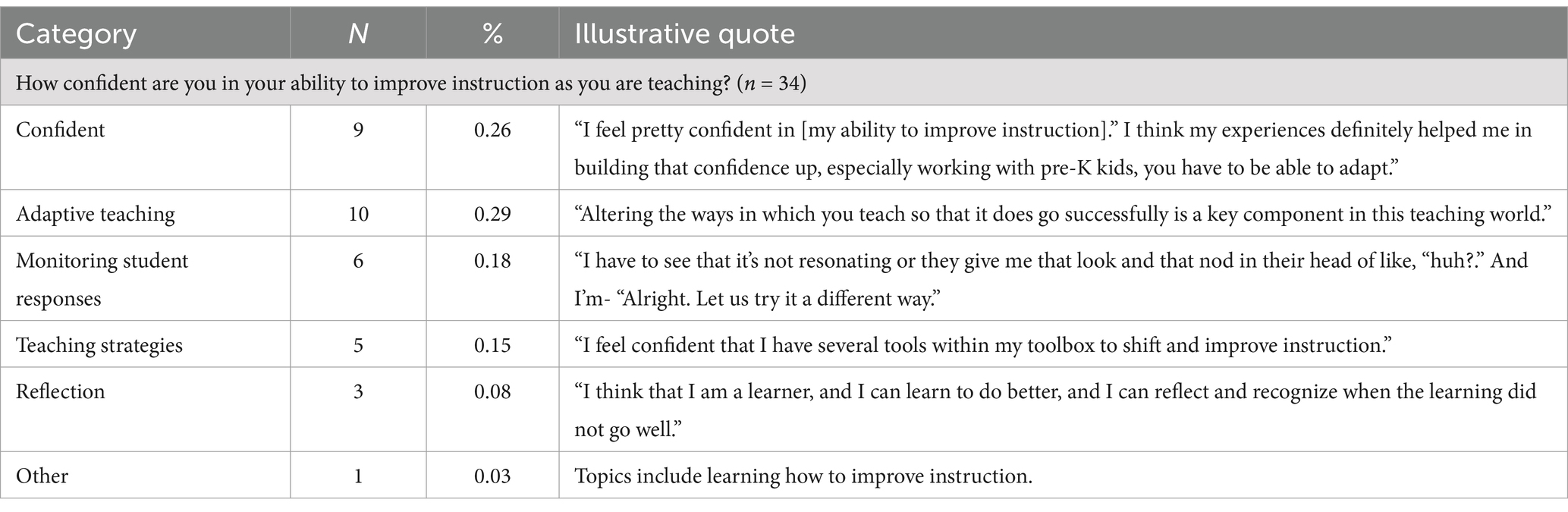

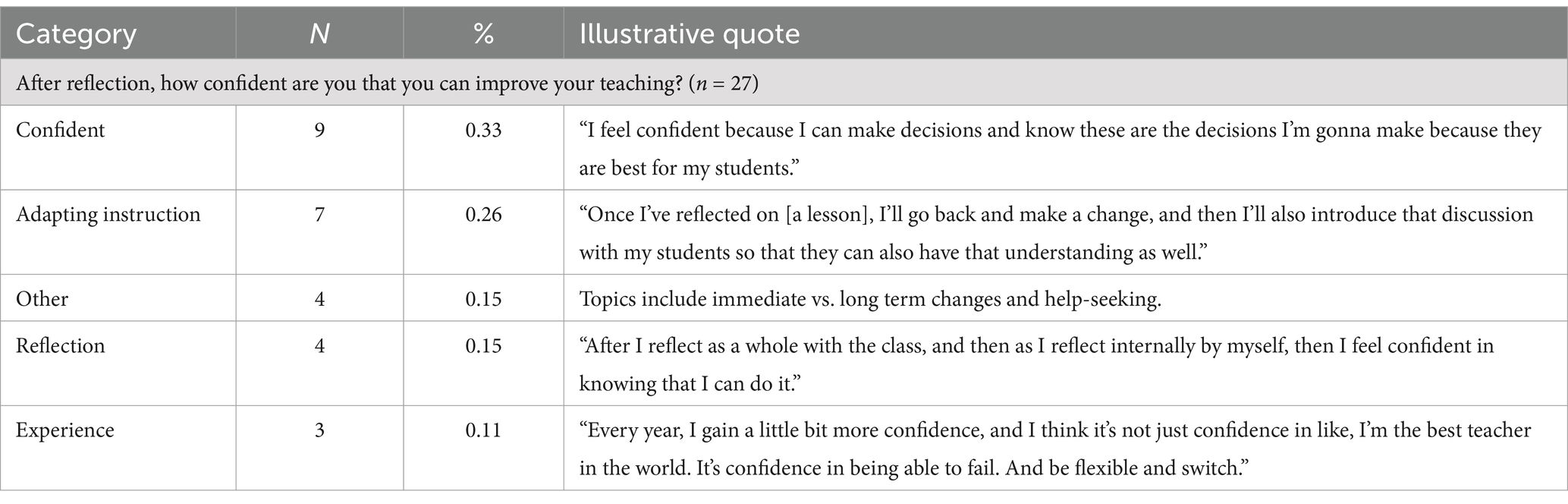

Teacher self-efficacy

Our second research question explored teacher self-efficacy for SRL strategy use (Table 10). Teacher self-efficacy positively relates to effective instructional practices in the classroom (Klassen and Tze, 2014; Zee and Koomen, 2016). We use Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy’s (2001) teacher self-efficacy model to organize the analysis for a richer understanding of the findings. Their Teacher Sense of Self-Efficacy Scale (TSES) categorizes teacher self-efficacy into three area: efficacy for student engagement, efficacy for classroom management, and efficacy for instructional strategies. Regarding efficacy for instructional practices, teachers generally expressed high confidence for planning quality instruction that promotes student growth (43%). One teacher claimed it was one of her “strengths.” Overall, the teachers felt confident in their ability to improve their instruction as it was occurring during the performance phase (26%) (see Table 11). “Altering the ways in which you teach so that it does go successfully is a key component in this teaching world.” They largely attribute that confidence to successfully monitoring student progress (18%) and adapting their lessons during instruction (29%). Teachers expressed confidence in adapting instruction to better meet student needs (26%). They described ways they develop their confidence, which included expanding their knowledge on a topic, learning new teaching strategies, and recognizing areas in their practice that could be improved. As was the case with teacher efficacy in planning and performance phases, teachers were largely confident that their instruction improves due to reflection (33%) (see Table 12).

Regarding efficacy for student engagement as viewed through an SRL lens, teachers spoke on their efficacy for monitoring student response and interaction with the material (11%). One teacher said,

I find that when you see that the children aren’t understanding it, or when they are going haywire, or when they need a break… altering the ways in which you teach so that it does go successfully is a key component. I think I’m pretty good at it.

Another teacher spoke on their perceived ability to create engaging content and promote student self-efficacy. “My goals are being tracked in the form of the children, and how excited they are to learn, and how proud they are of themselves, and how confident they become.”

While efficacy for classroom management was less frequently spoken upon as it related to SRL practices, several teachers did address confidence in their management styles. One participant elaborated on goals they set for themselves, explaining, “my goal, especially last year, was finding better classroom management, and I felt like I got pretty good at that.” Overall, few connections were made between classroom management and our target SRL components.

Facets of teacher self-efficacy outside the scope of the Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale included confidence related to years of experience and use of a variety of active instructional strategies. “Like with a degree of experiential education, I want them to learn by doing in a variety of ways.” Two teachers admitted to periodic lack of confidence because they were learning as they went. “But I am trying to get more confident by learning a lot really fast.” One of these participants was relatively new to teaching and expected to gain more confidence with experience. Finally, one teacher described growing confidence each year concurrently with their flexibility and adaptation.

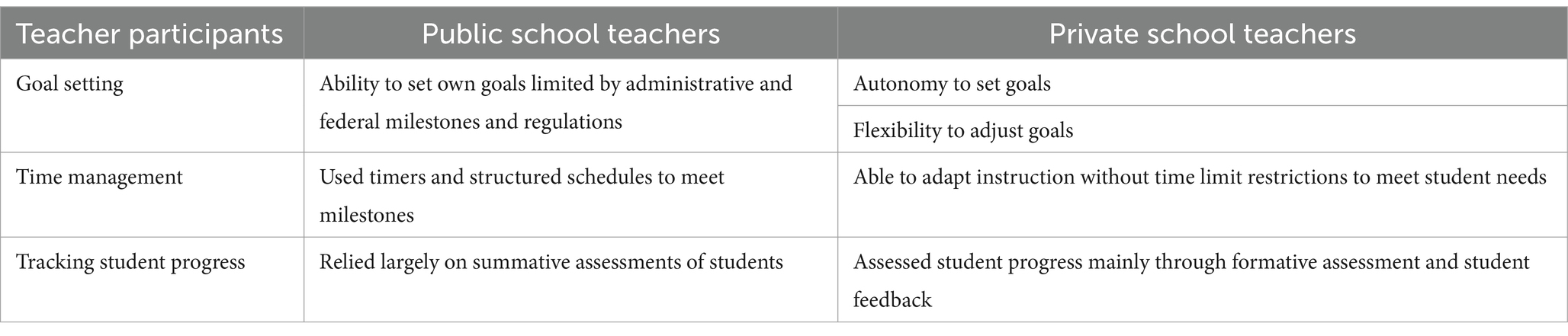

School type

Our third research question assessed the differences in SRL use between public and private school type. Although several SRL components were universally used by public school participants and their private school counterparts, there were areas where their SRL teaching strategies differed notably (see Table 13). The latter group attributed their instructional success to the flexibility and autonomy they are granted to set and adjust goals. One teacher reflected on the fluidity of their daily school schedule, commenting,

We set a daily schedule at the beginning of the day, and… I approach it with a certain amount of flexibility. So, I have my ideal one, but I’m very open to, if this is not working, how do I shift?

Another teacher shared a similar autonomy-based strategy for planning their school year, stating,

I will look at my grade level milestones, and I track it out for the year. I sit and track it in ways that make sense for me knowing that I’m going to need some flexibility for when [the students] get things quicker than I thought, or when it’s taking a little longer than I thought. So, I guess I start in a very macro sense and then week to week I make adjustments from there.

One participant detailed a time when a learning game they planned was not engaging the students and how they had the flexibility to shift to an entirely different activity that was more effective in retaining the attention of the students. The private school participants largely spoke on the ease of adapting instruction without time restrictions to meet student needs. These results align with research finding that private school teachers have greater autonomy in their instruction than their public-school counterparts (e.g., Miron and Nelson, 2002). Conversely, the public-school teachers were more limited by structures set in place by their administration, district, and federal government. They expressed feeling restricted or constrained by schedules and goals that were set for them. One public school teacher outlined their rigid ELA program structure, lamenting that time constraints mean that they do not always have the latitude to adapt or strengthen a lesson. As a result, they relied on time management more to meet milestones.

Largely, the private school teacher participants more frequently regarded relationship-building as critical to student success. Given that private schools generally offer more autonomy in their schedules and curriculum (Miron and Nelson, 2002), it makes sense that they would have a greater opportunity for relationship-building without some of the external pressures that exist in public schools. As relationship-building between students and their teachers lead to positive goal outcomes, particularly due to the increased opportunity to understand and meet individualized needs of students (Nordengren, 2019), teachers may consider reflecting upon strategies for strengthening relatedness among their students.

An area of greater divergence between school types concerned student feedback. While public school participants tracked student progress in more summative ways, private school teachers were more likely to assess their students using formative assessment methods. Studies have found that while both assessment types are effective, formative assessments were more highly associated with motivation to learn and SRL skills (Ismail et al., 2022). When asked about how they monitor student progress, a private school participant detailed their formative assessment process:

I find that the feedback from the children is the best way. How they are understanding material, how they are working with the material, how they respond to the material. And then I guess also, I do not want to say tests because we do not really believe in tests, but ways in which you can strategically test them to understand the material and asking them questions and seeing their answers.

Discussion

Research suggests that teacher prior knowledge about SRL influence teachers’ instruction (Spruce and Bol, 2015; Dignath-van Ewijk and Van der Werf, 2012). As such, our initial interview questions sought to gauge these teachers’ knowledge or familiarity with SRL. We considered their familiarity important for understanding their classroom practices relates to SRL and their beliefs about SRL in terms of their self-efficacy or confidence. We found just less than half of teachers stated they were not familiar with SRL theory, and the same percentage of respondents expressed some familiarity with the concepts if not the terminology. Teachers appeared to possess more practical than theoretical knowledge of SRL. Even though they were not able to well-articulate tenets of SRL theory, they were able to provide examples in the context of instructional practice that would suggest some implicit knowledge that guided their practices. The lack of explicit knowledge has been well-documented in the literature (Spruce and Bol, 2015) and would be logically linked to their more implicit rather than explicit SRL practices described during the interviews. These results are supported by observational studies that also show a lack of explicit instruction by teachers (Quackenbush and Bol, 2020; Spruce and Bol, 2015).

The remainder of the interview was devoted to how they implemented their implicit understanding of SRL in practices and their confidence in the effectiveness of these practices. Our continued discussion of our results is organized around our three research questions. We then move to a description of our limitations that lead to implications for research and practice.

Teacher implementation of SRL

Our first research question addressed how K–5 teachers implement SRL in their teaching. The present results offer some insight into how teachers plan their instruction. More specifically, we better understand the myriad goals they employ to plan their instruction. Tailoring and structuring goals were common, suggesting that goal setting may be somewhat formal and differentiated depending on student needs. This kind of goal setting has been recommended by other educators and researchers because they recognize individual differences and assessment in a more formative sense (Tomlinson and Moon, 2014).

Our results also inform how they improve their instruction. They largely turn to their fellow teachers, other colleagues, or text-based resources; however, a smaller number attempt to solve problems on their own. Some of these avenues are similar to student help-seeking behaviors, including a reluctance to ask others for help (Karabenick, 2012). The more adaptive help-seeking behaviors could be explicitly modeled by teachers for their students.

While we know a good deal about time management (Manso-Vázquez et al., 2016), we understand less about how teachers manage their time. Teachers in the present study were concerned about managing their time and even used physical timers. They carefully structured their schedules to cover different subjects at particular times during the day. Others were more flexible in their time management and were responsive to students’ needs when considering the pace and readiness for instruction.

There were some patterns detected across phases and components, sometimes blurring the lines between phases. The first was self-regulation interpreted as regulation of emotion or affect. One teacher participant explained that her understanding of SRL is that it is “tied to social emotional learning, to develop self-regulation skills in terms of coping with big emotions.” When initially asked about SRL, some teachers thought we meant self-regulation more generally as it pertained to socioemotional as well as academic characteristics. Again, this could be due the primary grade levels taught by these teachers (K–5). They mentioned this aspect of regulation in the context of goal setting, tracking goal accomplishment, and reflection phases. They wanted their students to be excited and confident in their learning, viewing it as more or equally important as academic goals. “Success comes in a child feeling a sense of pride and finding a love of learning. So even if they do not master the skill I’m hoping they master, if they came out excited to learn more or proud of themselves, I consider that a win all day every day.” Other patterns noted across phases pertained to monitoring and adjusting instruction to meet the needs of students collectively and individually. Teachers would informally or formally assess their students to set goals and to determine whether instructional goals were realized. Monitoring with adaptations were commonly described for the performance and reflection phases of instruction as well. In the reflection phase, adjustments for improving lessons could occur in collaborative ways with students and peers. Monitoring and adjusting instruction based on formative assessment is a critical metacognitive strategy that could be transferred to students during their own learning (Andrade, 2010; Panadero et al., 2018).

Teacher self-efficacy

Our second research question examined teacher self-efficacy as it related to SRL strategy use. Teachers were confident in their ability to plan for, implement, and reflect on their instruction, and largely attribute that confidence to their cumulative teaching experiences. Salient experiences include adopting an array of effective teaching strategies, monitoring and adapting their instruction, managing their time efficiently, getting feedback from students and colleagues, and reflecting on how their instruction may be improved. This confidence may be both positive and negative. Confidence suggests high self-efficacy in teaching, and teacher perceptions of SRL influence their self-efficacy and quality of SRL instruction (Hoy et al., 2006). However, confidence or self-efficacy does not always equate with competence.

There is a large literature on over-confidence in meta-analytic judgments. Calibration is one such judgment and represents the correspondence between individuals’ perceptions of their task performance and actual performance. We have repeatedly found that lower-achieving students are grossly inaccurate and overconfident; whereas higher achieving students are much more accurate and even a bit underconfident (Bol et al., 2016; Foster et al., 2017; Hacker et al., 2000). It may be these teachers are a bit overconfident in their ability to self-regulate their teaching. There has not been much research on teachers’ competence, confidence, and SRL, but Dignath (2021) found an interaction between teachers’ competence and the success of SRL professional development. Those teachers who had more competent instructional profiles profited more from the professional development than did their less competent counterparts. Whether their confidence also systematically varied awaits empirical confirmation.

While teacher self-efficacy for practicing SRL was high among our participants, explicit instruction of these components embedded within the SRL framework was rather low. One explanation could be that teachers generally are not familiar with SRL concepts, but naturally incorporate aspects of them into their implicit teaching. Some teacher participants were candid in admitting they had not heard of the term SRL but considered aspects of the framework as part of effective instruction. These results point to more implicit rather than explicit use of SRL and how it is communicated to students. Other researchers have observed a similar trend (Michalsky, 2020; Quackenbush and Bol, 2020; Spruce and Bol, 2015). Even though explicit instruction is shown to be more effective in promoting students’ SRL (Kistner et al., 2010), implicit instruction is more common. As noted earlier, teacher efficacy beliefs about SRL may influence to what extent they explicitly implement SRL in their instruction. Because these teachers taught at primary grade levels, they may not think their students capable of understanding SRL explicitly and opted for what they believed was a more developmentally appropriate way to implicitly convey these concepts. However, the literature supports early development of SRL (Dignath et al., 2008; Roebers et al., 2009; van Loon et al., 2021) and students may be more capable of understanding and using these strategies than teachers believe.

SRL and school type

Our third research question compared teacher SRL practices in differing school types. As in similar studies exploring differences between public and private schools, we also discovered a few themes that distinguished responses between teachers from each school type (Lubienski et al., 2008). Private school teachers had more of their autonomy or flexibility in goal setting. These findings support previous research that private schools generally have greater autonomy in shaping their curriculum (Miron and Nelson, 2002). Additionally, private school teachers were able to adjust their instruction to better meet student needs and used more formative assessment as well as student feedback in measuring progress. In contrast, public school teachers were held to administrative or federal standards in goal setting, were more formal in their time management strategies, and relied heavily on summative assessments of their students. These differences could be not only linked to administrative demands but perhaps the kinds of students enrolled in these courses. Another possible explanation for these differences may be school climate as an indicator of the degree and quality of SRL instructional practices (De Smul et al., 2019). In private schools, teachers also have more flexibility to incorporate SRL in their practice without the pressure of pacing and high-stakes testing (Madaus et al., 2009; Miron and Nelson, 2002).

Limitations

The current study is not without limitations. The first is the rather narrow focus of our interview questions both in terms of SRL components and the type of teachers SRL examined. As described by Kramarski and Heaysman (2021), there are three types of teacher SRL: (1) teachers self-regulate their own learning as learners, (2) teachers self-regulate their practice as self-regulated teachers, and (3) teachers activate students’ SRL as teachers of SRL. We primarily focused on the second type-how SRL influenced their teaching practices. However, we also had items about teachers’ familiarity with SRL and their confidence or self-efficacy in its effectiveness. The three types of SRL are interwoven. A second limitation is related to social desirability inherent in any self-report measure. Because the interviews were confidential, teachers may have been more candid. Based on our own observations during the interviews, the teachers seemed comfortable and willing to admit what they did and did not know. They also bolstered their responses with examples that would be difficult to fabricate. A third limitation was our reliance on self-selected volunteers, and that their responses may not be generalizable to other teachers. We did purposefully select from a group of volunteers, but nonetheless, they were self-selected into the sampling frame. Another limitation is that we relied on one data collection method, in-depth interviews. There is precedence for using one data collection technique like qualitative interviews (e.g., Muljana and Luo, 2023; Brady et al., 2024), yet it would be informative to conduct a more ethnographic type of design where we collected data from several sources longitudinally. This was not possible in the schools recruited due to resources and permissions. Although the purpose of qualitative studies typically is not to generalize (e.g., Polit and Beck, 2010; Niaz, 2007), external validity was constrained by having only twelve teachers, six from each type of school in primary grade levels. Even for a qualitative study, it may have been informative to have more teachers from each type of school.

Implications

Our findings have implications for theory, research, and practice. In terms of theoretical and practical implications, different components of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model may be more important given the context for instruction. For example, teachers who have more flexibility may find it more useful to focus on particular types of goals like those that rely on formative assessment results (Traga and MacArthur, 2023). Teachers constrained by district and state guidelines may rely on more summative types of assessments to develop goals. Time management may be more essential when meeting scope and sequence objectives in public schools. There may be more options for help-seeking in larger public schools. Moreover, the theory may emphasize different components within phases depending on the type of teacher self-regulated learning addressed. For example, if the goal is to develop the teachers’ own sense of SRL as a learner, the motivational components like self-efficacy and attribution theory may be more important. If the goal is to instill SRL among students, more tangible aspects of the model like goal setting, help-seeking, monitoring and time management might be more readily and obviously applied to teaching practices as a place to begin. Some researchers (Quackenbush and Bol, 2020; Spruce and Bol, 2015) have shown that teachers do tend to use more components in the performance phase of Zimmerman and Moylan’s (2009) model.

Implications for practice include professional development on SRL for in-service teachers (Perels et al., 2009; Gillies and Khan, 2009). Much of the literature relies on understanding and providing professional development for pre-service and not in-service teachers (e.g., Kramarski, 2017; Michalsky, 2014; Perry et al., 2008). We assert that professional development in SRL be on-going and not restricted to preservice teachers. The likelihood of teachers applying SRL in their teaching increases as administrators encourage this practice and reward teachers in their evaluations. The focus of professional development might be on how to explicitly incorporate SRL in teaching practices. One form of explicit instruction could be teachers modeling for the students how to engage in SRL strategies (Bandura, 1972). Another might be teachers developing goals with their students, reflecting on whether these goals were realized, and adjusting goals as they return to the planning phase. The later example reinforces the cyclical nature of the model for teachers and students alike.

There are myriad directions for future research. One direction would be to include data such as classroom observations and artifacts from teachers and students to understand how teacher beliefs and knowledge of SRL align with their classroom practices and their skills of activating SRL among their students. As the present study compares teacher SRL in schools serving communities of two distinct populations, professional development may be tailored depending on school type (public versus private). Exploring the effectiveness of classroom coaching of SRL would be informative, and explicit versus implicit teacher training practices may be another fruitful direction for study. A comparison of teachers’ understanding, beliefs, and practices by SRL type would also be informative. Examining these three strands of SRL may enable us to link them to their implicit and explicit SRL practices and hopefully illuminate avenues for making SRL more explicit. While research has been conducted on teacher knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors regarding student SRL, the present study contributes to the literature on teacher perceptions of SRL as it relates to their own practices in primary grades levels.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board Old Dominion University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because we recorded it before each interview.

Author contributions

SG-M: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CH: Project administration, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1464350/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, K. A., Slaten, C. D., Arslan, G., Roffey, S., Craig, H., and Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2021). “School belonging: the importance of student and teacher relationships” in The Palgrave handbook of positive education (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 525–550.

Andrade, H. L. (2010). “Students as the definitive source of formative assessment: academic self-assessment and the self-regulation of learning” in Handbook of formative assessment (New York: Routledge), 90–105.

Askell-Williams, H., Lawson, M. J., and Skrzypiec, G. (2012). Scaffolding cognitive and metacognitive strategy instruction in regular class lessons. Instr. Sci. 40, 413–443. doi: 10.1007/s11251-011-9182-5

Azevedo, R., Moos, D. C., Greene, J. A., Winters, F. I., and Cromley, J. G. (2008). Why is externally-facilitated regulated learning more effective than self-regulated learning with hypermedia? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 56, 45–72. doi: 10.1007/s11423-007-9067-0

Bandura, A. (1972). “Modeling theory: some traditions, trends, and disputes 11 the research reported in this paper was supported by research Gant M-5162 for the National Institute of Mental Health, United States Public Health Services” in Recent trends in social learning theory (New York: Elsevier), 35–61.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bingham, A. J., and Witkowsky, P. (2021). Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. Anal. Interpret. Qual. Data After Interv. 1, 133–146.

Bol, L., Campbell, K. D., Perez, T., and Yen, C. J. (2016). The effects of self-regulated learning training on community college students’ metacognition and achievement in developmental math courses. Commun. College J. Res. Pract. 40, 480–495. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2015.1068718

Brady, A. C., Wolters, C. A., Pasque, P. A., Yu, S. L., and Lin, T. J. (2024). Beyond goal setting and planning: an examination of college students’ self-regulated learning forethought processes. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 1, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/14697874241270490

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Butler, R. (2007). Teachers' achievement goal orientations and associations with teachers' help seeking: examination of a novel approach to teacher motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 241–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.241

Butler, D. L., and Cartier, S. C. (2004). Promoting effective task interpretation as an important work habit: a key to successful teaching and learning. Teach. Coll. Rec. 106, 1729–1758. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00403.x

Calderhead, J. (1991). The nature and growth of knowledge in student teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 7, 531–535. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(91)90047-S

Camp, H. (2017). Goal setting as teacher development practice. Int. J. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 29, 61–72.

Cazan, A. M. (2013). Teaching self-regulated learning strategies for psychology students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 78, 743–747. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.04.387

Cebesoy, U. B. (2013). Pre-service science teachers' perceptions of self-regulated learning in physics. Turk. J. Educ. 2, 4–18.

Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry: a methodology for studying lived experience. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 27, 44–54. doi: 10.1177/1321103X060270010301

Cleary, T. J., Slemp, J., and Pawlo, E. R. (2020). Linking student self-regulated learning profiles to achievement and engagement in mathematics. Psychol. Sch. 58, 443–457. doi: 10.1002/pits.22456

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed method research. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Daly, J., Kellehear, A., and Gliksman, M. (1997). The public health researcher: a methodological approach. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

De Boer, H., Donker, A. S., Kostons, D. D., and Van der Werf, G. P. (2018). Long-term effects of metacognitive strategy instruction on student academic performance: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 24, 98–115. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.03.002

De Smul, M., Heirweg, S., Devos, G., and Van Keer, H. (2019). School and teacher determinants underlying teachers’ implementation of self-regulated learning in primary education. Res. Pap. Educ. 34, 701–724. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2018.1536888

Dellinger, A. B., Bobbett, J. J., Olivier, D. F., and Ellett, C. D. (2008). Measuring teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: development and use of the TEBS-self. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 751–766. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2007.02.010

Dent, A. L., and Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 425–474. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Dignath, C. (2016). What determines whether teachers enhance self-regulated learning? Predicting teachers’ reported promotion of self-regulated learning by teacher beliefs, knowledge, and self-efficacy. Frontline Learn. Res. 4, 83–105. doi: 10.14786/flr.v4i5.247

Dignath, C. (2021). For unto every one that hath shall be given: teachers’ competence profiles regarding the promotion of self-regulated learning moderate the effectiveness of short-term teacher training. Metacogn. Learn. 16, 555–594. doi: 10.1007/s11409-021-09271-x

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2018). Teachers’ direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes–insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacogn. Learn. 13, 127–157. doi: 10.1007/s11409-018-9181-x

Dignath, C., Büttner, G., and Langfeldt, H. P. (2008). How can primary school students learn self-regulated learning strategies most effectively? A meta-analysis on self-regulation training programmes. Educ. Res. Rev. 3, 101–129. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2008.02.003

Dignath, C., and Veenman, M. V. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—evidence from classroom observation studies. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 489–533. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09534-0

Dignath-van Ewijk, C., and Van der Werf, G. (2012). What teachers think about self-regulated learning: investigating teacher beliefs and teacher behavior of enhancing students’ self-regulation. Educ. Res. Int. 2012, 1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/741713

Dunlosky, J., and Rawson, K. (2019). “Calibration and self-regulated learning” in The Cambridge handbook of cognition and education. eds. J. Dunlosky and K. Rawson (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 647–677.

Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: their role in motivation, personality and development. New York: Psychology Press.

Elhusseini, S. A., Tischner, C. M., Aspiranti, K. B., and Fedewa, A. L. (2022). A quantitative review of the effects of self-regulation interventions on primary and secondary student academic achievement. Metacogn. Learn. 17, 1117–1139. doi: 10.1007/s11409-022-09311-0

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., and Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 5, 1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Farrell, T. S. C. (2007). Reflective language teaching: from research to practice. London, UK: Continuum.

Fidan, T., and Öztürk, İ. (2015). Perspectives and expectations of union member and non-union member teachers on teacher unions. J. Educ. Sci. Res. 5, 191–220. doi: 10.12973/jesr.2015.52.10

Foster, N. L., Was, C. A., Dunlosky, J., and Isaacson, R. M. (2017). Even after thirteen class exams, students are still overconfident: the role of memory for past exam performance in student predictions. Metacogn. Learn. 12, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11409-016-9158-6

Gillies, R. M., and Khan, A. (2009). Promoting reasoned argumentation, problem-solving and learning during small-group work. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 7–27. doi: 10.1080/03057640802701945

Glogger-Frey, I., Deutscher, M., and Renkl, A. (2018). Student teachers' prior knowledge as prerequisite to learn how to assess pupils' learning strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 76, 227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.01.012

Guo, W., and Wei, J. (2019). Teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning in mathematics: a study of Chinese secondary students. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 28, 265–275. doi: 10.1007/s40299-019-00434-8

Hacker, D. J., Bol, L., Horgan, D. D., and Rakow, E. A. (2000). Test prediction and performance in a classroom context. J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 160–170. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.160

Hadwin, A., Järvelä, S., and Miller, M. (2017). “Self-regulation, co-regulation, and shared regulation in collaborative learning environments” in Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (New York: Routledge), 83–106.

Hagger, H., and Malmberg, L. E. (2011). Pre-service teachers' goals and future-time extension, concerns, and well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 598–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.014

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: disposition, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. Am. Psychol. 53, 449–455. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.4.449

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Hattie, J. A. C., and Yates, G. (2014). Visible learning and the science of how we learn. London: Routledge.

Heikkinen, S., Saqr, M., Malmberg, J., and Tedre, M. (2023). Supporting self-regulated learning with learning analytics interventions–a systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 3059–3088. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11281-4

Hoy, A. W., Davis, H., and Pape, S. J. (2006). “Teacher knowledge and beliefs” in Handbook of educational psychology. eds. P. A. Alexander and P. H. Winne (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 715–737.

Ismail, S. M., Rahul, D. R., Patra, I., and Rezvani, E. (2022). Formative vs. summative assessment: impacts on academic motivation, attitude toward learning, test anxiety, and self-regulation skill. Lang. Test. Asia 12:40. doi: 10.1186/s40468-022-00191-4

Jaeger, E. L. (2013). Teacher reflection: supports, barriers, and results. Iss. Teach. Educ. 22, 89–104.

James, M., and McCormick, R. (2009). Teachers learning how to learn. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.023

Karabenick, S. A. (2012). “Help seeking as a strategic resource” in Strategic help seeking (New York: Routledge), 1–11.

Karlen, Y., Hertel, S., and Hirt, C. N. (2020). Teachers’ professional competences in self-regulated learning: an approach to integrate teachers’ competences as self-regulated learners and as agents of self-regulated learning in a holistic manner. Front. Educ. 5:159. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00159

Katsantonis, I., and McLellan, R. (2023). Students’ voices: a qualitative study on contextual, motivational, and self-regulatory factors underpinning language achievement. Educ. Sci. 13:804. doi: 10.3390/educsci13080804

Khan, H. M. A., Farooqi, M. T. K., Khalil, A., and Faisal, I. (2016). Exploring relationship of time management with teachers’ performance. Bull. Educ. Res. 38, 249–263.