- School of Natural and Environmental Science, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, North East England, United Kingdom

Most live broadcast work in education operates with an expert to novice delivery mode, and in indoor settings such as surgical teaching environments. Those few examples of live broadcasts from outdoor locations have heavy resource requirements, limiting their uptake within Higher Education. Working with undergraduates in a students as partners approach, this research aims to test the feasibility of a low-cost and low-tech solution to co-produce a live fieldwork broadcast within the biosciences. The co-production partnership successfully produced a live broadcast from conception to delivery in 2022–2023 with three placement students and in 2023–2024 with two placement students and three mentors. The students were involved in all aspects of design, development, and delivery of the live fieldwork broadcast. A pocket wireless modem creates an outdoor wireless network with a mobile device and wireless microphones used to deliver the broadcast. Semi-structured interviews, student self-assessments, and a reflective researcher diary explored the impact of this approach to co-produce a live fieldwork broadcast. Enjoyable aspects of the placement identified were the opportunity for new experiences and a sense of achievement. The live fieldwork broadcast placement enabled the placement students to develop 28 skills, with 73% of skills identified by at least two of the placement students. Most skills developed were transferable (54% of student identified skills), including teamwork and project planning. The simple and low-cost technology used provides a solution to address the barriers of technology integration within fieldwork and offers insight into the experience of working in partnership during a live fieldwork broadcast.

1 Introduction

Live broadcasting or livestreaming or live video streaming involves a real-time transmission of information over the internet. It is intended for consumption by the public and often accessed via social media (e.g., YouTube Live, Facebook Live; Rogers, 2023). Mechanisms of interaction within live streaming is under researched (Wang and Li, 2020), although there is some research to suggest that interaction between presenter and audience is key to engagement (Lv et al., 2022). Live streaming in higher education (HE) institutions is well-documented with implementation in surgical teaching (Williams et al., 2011; Brandt, 2020; Fang et al., 2022), dental teaching (Iwaki et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021), development of English-speaking skills (Shen et al., 2008; ChanLin, 2020), film studies (Robert and Lenz, 2009), and nutrition education programs (Adedokun et al., 2020). Justification for the use and benefits of live broadcasting include access to broader audiences (Walker-Cook, 2019; Obenson, 2021), enhanced views via multiple camera feeds (Iwaki et al., 2013; Brandt, 2020), providing a comfortable clinical teaching environment (Fang et al., 2022), and as a solution for remote teaching during COVID-19 pandemic (Yu et al., 2021; Stagg et al., 2022).

The majority of these education live broadcasts involve indoor spaces with wireless internet, and specialist recording technologies (Williams et al., 2011; Iwaki et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2022). Although broadcasting indoors is not without challenges, e.g., requirement to sterilize audio-visual equipment in surgical settings (Brandt, 2020); live broadcasting outdoors has its own unique set of challenges including the need for portable equipment (Robert and Lenz, 2009) that can withstand environmental conditions and the ability to set up a wireless network (Cassady et al., 2008). Whilst this can be addressed via the use of (Wireless) Local Area Network [(W)LAN] in a field setting (Whitmeyer et al., 2020) or the use of satellite systems (Robert and Lenz, 2009), many of these adaptations require a digital technology field expert and/or specialist outdoor recording equipment (Marshall et al., 2022), meaning cost, skills, and capacity to invest the time in this, can present a barrier for wider adoption (Fletcher et al., 2007; Thomas and Munge, 2017; Clark et al., 2020), at present the feasibility of a low-cost and low-tech solution for live broadcasts in the outdoors has not been tested within the literature.

Live fieldwork broadcasts have become a regular occurrence for the Open University's fieldwork teaching to its online student population (FieldCasts; Open University, 2023; Brown et al., 2023) yet their use in a more typical university biosciences fieldwork setting without specialist technology support is limited. In-field mobile technologies have been used to support inclusion and access to field courses for students who might traditionally be excluded from participating (Atchison et al., 2019; Marshall et al., 2022). They were also implemented as a response to restrictions to fieldwork and the outdoors during the COVID-19 pandemic (Stagg et al., 2022). Where the large audience (almost 400,000 registered) of the geography and science #FieldworkLive program from Field Studies Council (FSC) suggests an appetite for live broadcast delivery modes across education sectors to access fieldwork learning (Stagg et al., 2022). Although the context of restrictions to outdoor spaces and UK school/university closures during this time likely influenced this high audience uptake. Post-pandemic studies of live fieldwork broadcasts are missing from the literature and are required to develop an understanding of the value and experience of adopting live streaming technologies to deliver fieldwork content without COVID restrictions limiting access to fieldwork environments. Although the specific functions and affordances of live broadcast in education are documented (Williams et al., 2011; Iwaki et al., 2013; Walker-Cook, 2019; Brandt, 2020; Obenson, 2021; Fang et al., 2022), the research of live broadcast in fieldwork education is more limited (Stagg et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2023) with the future role of live fieldwork broadcast in outdoor fieldwork settings currently undocumented. This research will seek to fill this gap by presenting a proof-of-concept study of using live fieldwork broadcasts post-COVID-19 and present a view of a range of fieldwork applications for live broadcasting.

The advancements in low-cost recording and broadcast technologies offer potential for creative and interesting user-generated video content (Laaser and Toloza, 2017), with the unique role that a student facilitator can play in promoting peer discussion during live broadcasting (ChanLin, 2020). However, much of the content of live broadcast within education can be defined as “explainer” style videos (Kulgemeyer, 2020) with expert delivery to a novice audience (Williams et al., 2011; Iwaki et al., 2013; Brandt, 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2022; Stagg et al., 2022). The Open University's FieldCasts actively encourage participation and promote student decision-making (Open University, 2023). During the live broadcasts presenters adopt a range of roles that support students throughout the fieldwork enquiries by guiding their thoughts, promoting engagement, encouraging participation, and developing a sense of belonging (Brown et al., 2023). Yet despite guiding the fieldwork decision-making process, the students are still in an audience role rather than as a co-creator of knowledge. This research seeks to add to the literature on the roles that students adopt during live fieldwork broadcasts by presenting a method of working with students to co-produce live fieldwork broadcasts within the biosciences.

Recognizing that bioscience students' employability skills are developed during placement opportunities (Hejmadi et al., 2012) and inspired by the practice and methodology of a youth-led live broadcast “Nattering with the NHS” where students identified employability options with the NHS (Reeves et al., 2022), this research will evaluate the impact on students of participating in the creation and delivery of a live fieldwork broadcast via an employability placement. It will test the feasibility of a low-cost solution to network and broadcast from a field environment that does not require expert knowledge, or specialist skills to operate.

Building on the Students as Partners (SaP) framework (Healey et al., 2014) and addressing the need for future research to explore both the varying experiences and perceptions of partnership among students (Healey et al., 2014), as well as the challenges, opportunities, and benefits of creating partnership learning communities (Healey et al., 2016), this study examines the concept of partnership within the context of co-producing a live biosciences fieldwork broadcast with undergraduate students. It investigates the emotions and attitudes of those engaged in partnership during the broadcast, highlights the skills developed throughout the process, and reflects on the future potential of live broadcasting in fieldwork education.

2 Context and placement brief

Every second-year undergraduate student pursuing a marine science degree at the authors' HE institution engages in a 35 h work placement as a component of their Research and Employability Skills module.

Placement students undertake a task or project relating to research, development, or communication in marine science on behalf of their placement provider, to enhance their employability upon graduation. In total, 24 different placement providers offered a number of placements to students in 2022–2023 with 23 placement providers in 2023–2024. All students were provided with short placement briefs written by the providers.

Three live fieldwork broadcast placements were offered in both 2022–2023 and 2023–2024, with the placement brief provided to all students alongside participant information about the research project. Participation in the research project was not a pre-requisite for undertaking the live fieldwork broadcast placement.

The live fieldwork broadcast 35 h placement ran over nine weeks within an academic semester. In 2022–2023, three students accepted the live fieldwork broadcast placement. In 2023–2024, two students accepted the live fieldwork broadcast placement. During 2023–2024, the placement students from 2022 to 2023 were offered a paid mentoring role within the partnership. All three 2022–2023 placement students accepted and were employed in a peer-mentor role for 8–10 h each.

Participation in the research was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent in line with the ethical approval granted by the School of Natural and Environmental Sciences at the researchers' university (Ref: 26538/2022).

In 2022–2023, the majority of sessions were held in-person, with all placement students in attendance. There were three sessions where placement students had the opportunity to work independently during asynchronous remote sessions, with support from the placement facilitator available in-person or via Microsoft Teams. Two out of the three students scheduled in-person time with the placement facilitator.

In 2023–2024, alongside the scheduled in-person and asynchronous remote sessions, several synchronous remote sessions were scheduled. This offered a more realistic model of a hybrid work environment for the placement students. A full placement schedule for 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 live fieldwork broadcasts can be found in the Supplementary material.

Placement students named the live fieldwork broadcast #NclLive during session one in 2022–2023. For consistency this name remained for 2023–2024.

Eight potential areas of development within the placement were identified and shared with students; (1) Communication and liaison, (2) Creative thinking and design, (3) Developing educational content to meet a project brief, (4) Public engagement and science communication, (5) Digital skills, (6) Problem solving, (7) Teamwork and collaboration, and (8) Project management.

3 Methods

This research is underpinned by a pragmatic epistemological basis. In particular, a Deweyan pragmatism shared in Hammond (2013) whereby both our experiences form our sense of reality and acknowledge the role that a researcher plays in that. This collaboration between myself as both postgraduate researcher and placement provider/facilitator, and the students themselves works to ensure that outputs from this research are grounded in the experience of the placement. In attempting to report on the impact of partnership work for students in the under-explored area of curriculum design (Healey et al., 2014), this research will adopt interview methods to delve into student responses, to the partnership and their role in co-producing a live fieldwork broadcast.

3.1 Logistics of the live broadcast

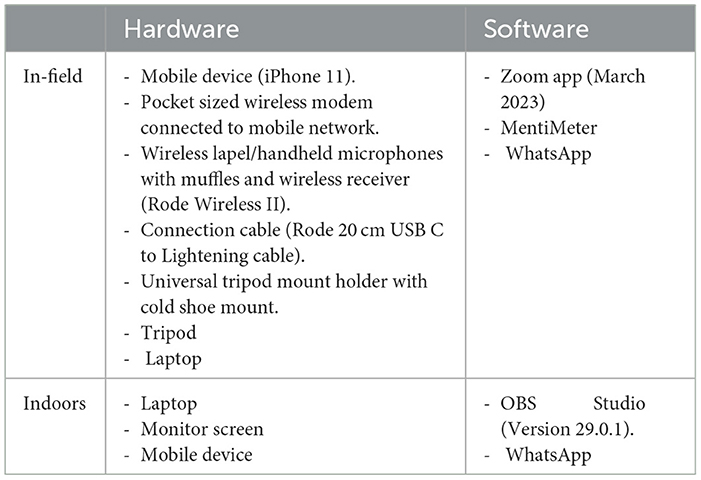

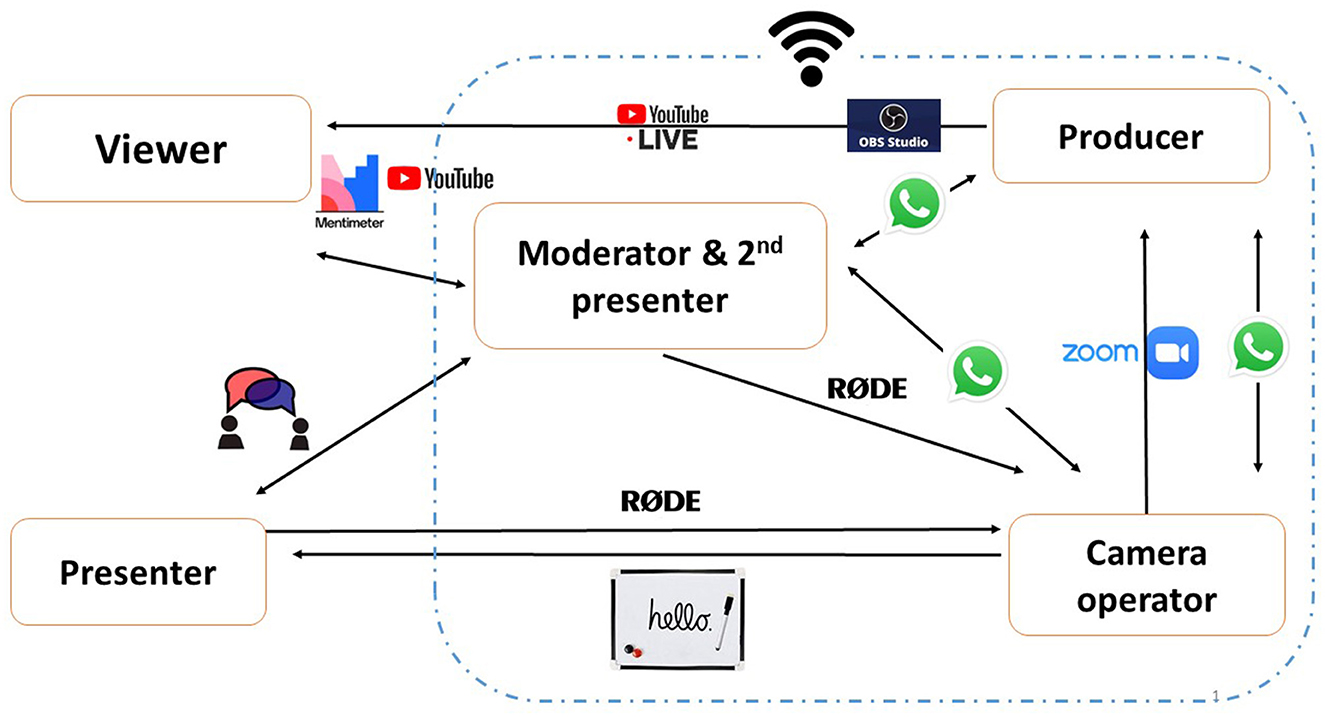

Inspired by previous live fieldwork broadcasts (Stagg et al., 2022; Open University, 2023) in delivering a live broadcast from an outdoor fieldwork location, five roles were identified: (1) The main presenter whose role was to deliver the majority of the broadcast live to camera; (2) An additional presenter delivered sections of the broadcast live to camera and moderated digital synchronous communication with viewers; (3) A camera operator based in the field location captured the live broadcast; (4) A producer located indoors, remote from the field location received the audio and video feeds, and live produced the broadcast, sharing it with (5) the viewers.

A pair of wireless lapel microphones captured the audio from the two presenters, with the microphone receiver attached to a mobile device. The mobile device was connected in a Zoom meeting using the Zoom mobile app. The producer was also connected to that same Zoom meeting, with the live Zoom meeting fed into OBS studio. OBS studio enabled the live producer to add production elements such as transitions, pre-recorded videos, and overlay images onto the broadcast. The broadcast was streamed live via YouTube Live. Interaction with viewers was made possible through YouTube comments and via embedded MentiMeter activities during the broadcast (2022–2023 only).

An outdoor wireless network was created using a pocket-sized wireless modem that generated a wireless hotspot. This opened up the possibilities for interesting bioscience locations for the broadcast, with the team able to broadcast from any location without an electricity hook-up, providing there was sufficient mobile signal for the wireless modem. The wireless hotspot powered the Zoom meeting on the mobile device and a laptop/tablet device to monitor YouTube comments and MentiMeter outputs (2022–2023 only). Off camera communication between presenters and the camera operator was possible during pre-recorded video segments, with the camera operator using pre-determined hand signals and a whiteboard to communicate with presenters during live segments of the broadcast. WhatsApp was used for the producer to communicate a pre-determined message to signify when the broadcast was live, this meant that the presenters knew when they were live on the broadcast. Figure 1 illustrates the networked fieldwork environment, detailing lines and modes of communication. Table 1 lists the in-field and indoor hardware and software required for the live broadcast.

Figure 1. Networking the field environment for a live broadcast with lines and modes of communication described.

3.2 Semi-structured interviews

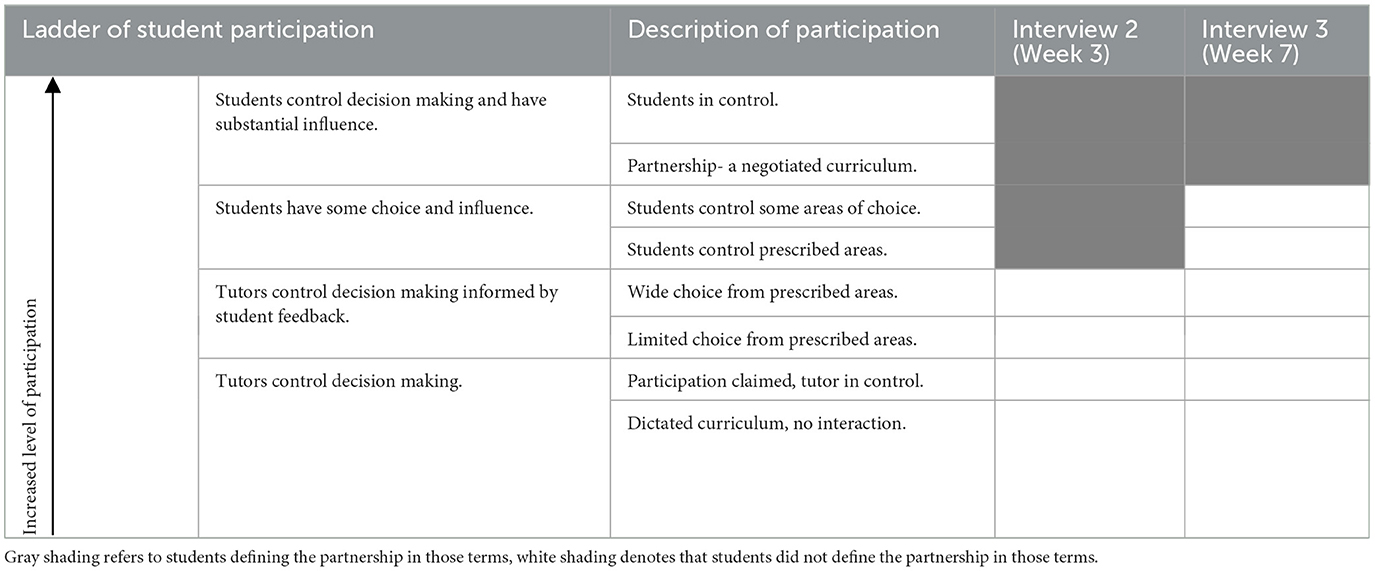

Four interviews were conducted with each of the five placement students. Table 2 summarizes the timing and focus of each of the four interviews. Interview one offered a chance for students to find out more about the placement offer and share some of their initial ideas of live broadcast, it offered opportunities for the students to share how their existing skills and experiences could be utilized within the placement and what they hoped to achieve and develop during the placement. Interviews two and three provided placement students with the opportunity to share their experience of the placement and discuss their progression. With discussions focused to capture feedback to inform ongoing partnership work within the placement, students were also asked to define the level of partnership during the live fieldwork broadcast placement using a ladder of student participation in curriculum design (Bovill and Bulley, 2011). Interview four offered a reflection of the placement, as well as offering space for students to share their thoughts and ideas about the future role of live broadcast in education. During 2023–2024, interviews were conducted with each mentor to capture their experience of this mentorship role in the co-production partnership.

The 23 semi-structured interviews followed an interview schedule as a guide but were flexible in that students could manage the direction of discussion and ask questions back to the interviewee. Ten interviews were held in person and 13 online via Zoom. This was determined by student availability and preference, with each interview audio recorded and subsequently transcribed. A copy of the individual interview guides are included within the Supplementary material.

3.3 Student self-assessment

All five placement students completed two self-assessments at the start and end of the placement. At the end of the placement students were also asked to explain their response with their responses captured within the semi-structured interviews.

Competency statements were written at a basic, proficient, and advanced level for each of the eight skill areas identified as development opportunities within the placement. Most of these skill areas are transferable outside of the biosciences, e.g., “Teamwork and collaboration” and “Project Management.” Two skill areas “Development of education content” and “Public engagement and science communication” require the use of students' biosciences knowledge. Students defined their competency level using these basic, proficient, and advanced level descriptors. Drawing upon the graduate framework at the placement students' university (Figure 2). Students scored their capabilities of these graduate attributes on a scale of 0–10, where 0 was not developed yet and 10 was well-developed.

Figure 2. Graduate framework at the placement students' university detailing the 12 attributes of a graduate. Students scored their capabilities of these attributes on a scale of 0–10, where 0 was not developed yet and 10 was well developed (Newcastle University, 2024).

Information on these skill areas and the competency statements can be found in the Supplementary material where a copy of both of the student self-assessments can be found.

3.4 Reflective researcher diary

In acknowledgment of the range of emotions that are experienced during SaP projects (Healey and France, 2022), the placement facilitator kept a reflective researcher diary throughout the placement, with individual entries completed within 24 h of each placement session. A template was used to guide the reflective entries (Supplementary material) with headings to record a description of the session (Wright and Hodge, 2012), feelings identified during the session (Healey and France, 2022), opportunity to evaluate the success of the session, identify key conclusions from the reflection (Trehan and Rigg, 2012), and determine any actions to be implemented (Harrison et al., 2003).

3.5 Data analysis

Each interview was transcribed and analyzed using the six-stage analytical guidance applied to reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019, 2020) whereby the researcher was actively involved in producing themes from the data. A predominantly inductive approach was adopted with theories identified from the data rather than being imposed beforehand. This means that the themes presented within this research represent what participants have communicated within the research, but it is acknowledged the role that the author as the researcher and placement facilitator plays in constructing those themes during the data analysis process. Additionally, two frameworks were applied to the data to support deductive analysis related to specific research aims. Firstly, values that supported the development of a partnership (Healey et al., 2014) were used to identify aspects of the live broadcast placement that promoted a sense of partnership. Secondly, a skills framework (Peasland et al., 2019) was used to define skills identified and developed within the placement.

All students' self-assessed skill competencies were totaled across the basic, proficient and advanced categories for the pre and post self-assessment. Total self-assessment levels for each graduate attribute were compared pre and post to determine cumulative change in the graduate attribute for all students combined.

4 Findings

4.1 Feasibility of a low-cost and low-tech solution to live broadcasting

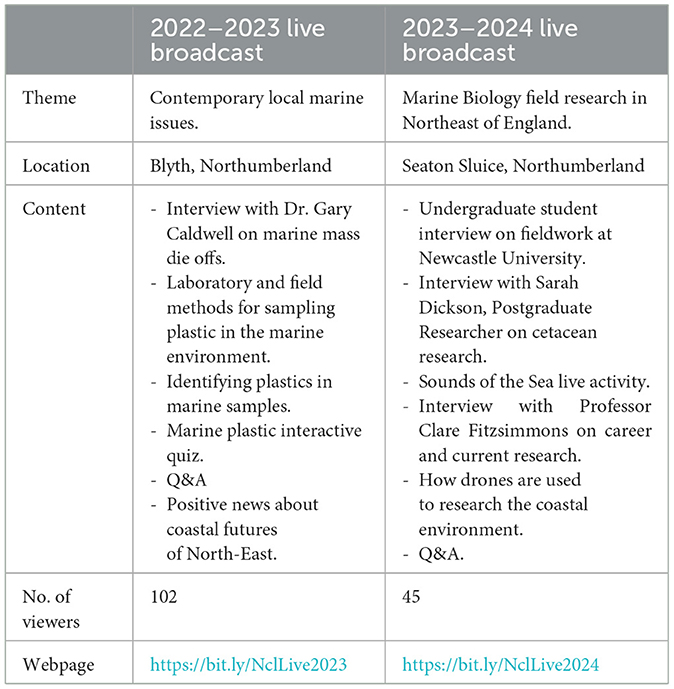

Placement students successfully co-designed, co-developed and co-delivered a live fieldwork broadcast in both years (Table 3). Key aspects included engaging with bioscience experts at various career stages, sharing local and topical marine or coastal research, and offering opportunities for live interaction with the audience (Table 3).

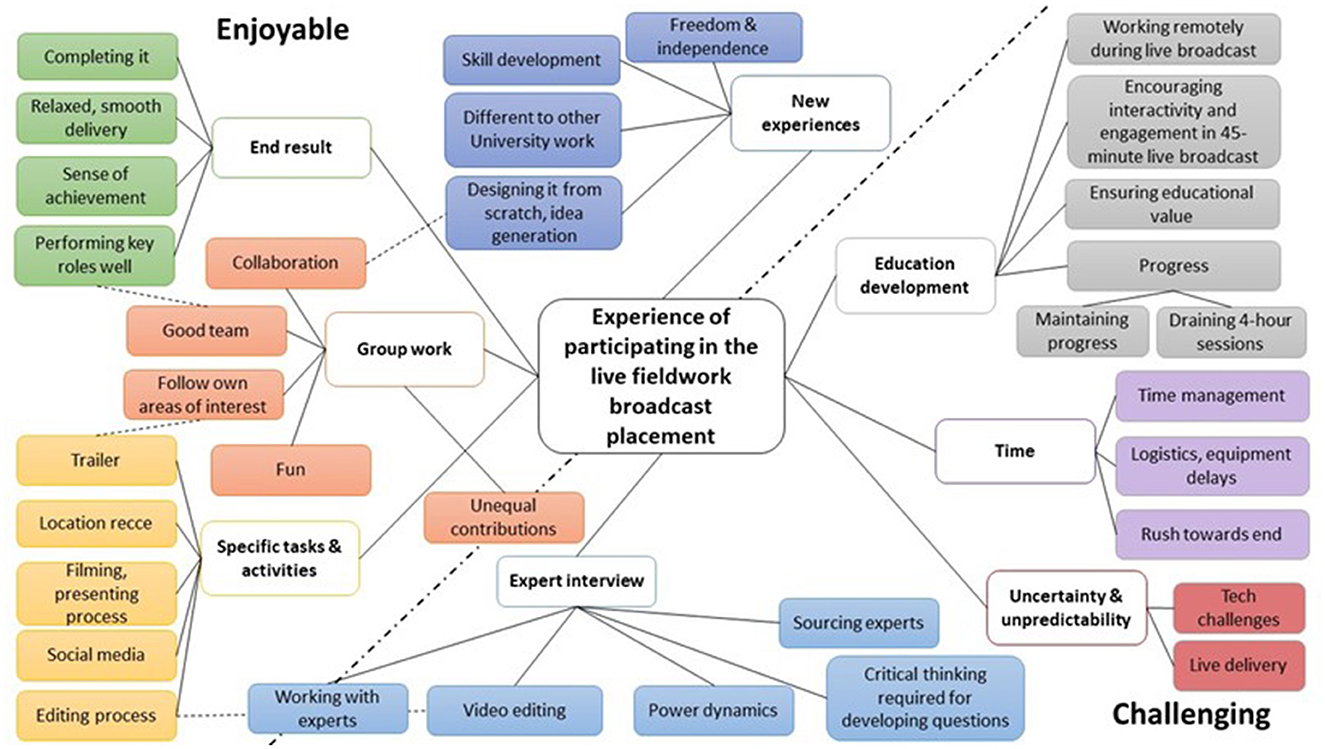

4.2 Emotions and attitudes

A summary concept map of the themes identified within the reflexive thematic analysis of the interview data presented four challenges and four main areas of enjoyment shared by placement students when reflecting on the live fieldwork broadcast placement (Figure 3). It summarizes the findings from all 15 semi-structured interviews conducted with the five placement students involved in the co-production of the live fieldwork broadcasts. The challenges and enjoyable aspects identified by the students provide valuable student voice and insight into their experience, which this research considers to be the first student co-produced live fieldwork broadcast in the biosciences.

Figure 3. Concept map summarizing the results of the reflective thematic analysis on placement students' experience of participating in the live fieldwork broadcast placement. Dashed lines between themes indicate links between themes.

One of the areas of challenge was the development of the pre-recorded expert interview segment of the broadcast. Preparing suitable interview questions that enabled the academics interviewed to share their bioscience research in an accessible manner required critical thinking and the use of decision-making skills to make editorial decisions when editing the footage into the interview segment. Interestingly a specific area of challenge related to the expert interview was working with and interviewing one of the placement student's lecturers;

“He is my lecturer... He does decide my grades…don't want to annoy him in any way…that was one of the big challenges for me.” Placement student 2

This highlighted an issue around identified power dynamics of a student interviewing one of their lecturers.

Time was a theme that emerged as a challenge for the placement students during analysis. There were some aspects of the placement that were out of control of the team and impacted upon the timing of the project. Equipment delays resulted in logistical challenges. Although it was challenging, students demonstrated problem-solving skills to address the logistical delays;

“If the equipment isn't there for like the actual demo (of the) method itself, I could very easily just describe that. I think the most important bit is actually making sure we've got some plastic, in a dish, in a microscope.” Placement student 1

The fixed live broadcast deadline caused some anxiety to placement students, especially with their other commitments;

“I would say that towards the end. I thought we were sort of in a rush to get things done, which was a bit stressful.” Placement student 1

“So, I would say it's getting a bit more hectic with the placement we've got a lot more stuff to do. Unfortunately, that is matching with I'm now having a lot more assignments due. I have three assignments on the same day, the day right before we film the broadcast. So, it's a bit stressful having to plan all of that, but I am managing.” Placement student 4

The development of educational content was something that was new to all of the placement students. Unsurprisingly, this was an area of challenge. Specific challenging aspects of this were related to ensuring educational value in what they were delivering and maintaining interactivity with viewers during the broadcast;

“So, making educational content and then making sure in the creative process, it's like in a digestible manner, and that you keep the attention.” Placement student 1

During the placement, students had a training session with the FSC who have delivered multiple live broadcasts. This provided an opportunity to seek advice and confirmation about some of their education development ideas. Despite this training, the nature of the partnership, where students co-create the content and the novel delivery mode of broadcast, aspects of the placement still remained unpredictable, which led to feelings of uncertainty with the placement students tackling unprecedented challenges;

“Unpredictable… as in anything could happen. It could get to the day, we can only plan so much. So, it really does just depend on the day.” Placement student 2

“…big one was the Monday before the broadcast and the video wasn't working, and we had to like troubleshoot and try and find a different solution, and we were trying a lot of different methods to try and fix it.” Placement student 5

One of the enjoyable aspects of the placement was the end-result of the live broadcast, with placement students reflecting on the sense of achievement felt after delivering it;

“I had a great time actually delivering the final broadcast, I think like, watching what we created, and then being able to actually do a good job.” Placement student 1

“I think it was just interesting the sort of ideas that we wanted to pursue about like research in the northeast, like I think, that was quite interesting….I think it was like nice to sort of see that you can do things that feel like a bigger part, like feel like bigger thing, but also I think I just enjoy the entire process and just seeing what is actually involved with...creating like a project like this.” Placement student 5

Individual students had their own areas of responsibility during the placement, with these personal projects being aspects that were particularly enjoyable;

“I really liked when we talked about a trailer and I thought like oh my goodness that's like right up my street.” Placement student 2

The placement provided new experiences for the students, and these were found to be enjoyable, different from their existing experiences at university and offered opportunities to do new things with new people;

“And it was, it was fun learning, like different skills and working like collaboratively with different people.” Placement student 4

“Not the same as going to lectures and doing essays. So, from my perspective I think it's really quite refreshing.” Placement student 3

The students enjoyed the group work associated with the placement, with the experience of working within the team on the live broadcast changing their outlook toward group work and offering the chance to liaise and work with expert researchers in the biosciences;

“I really really loved collaborating with everybody, with our core team and our experts, and then with our sort of mentors from last year. That was really useful... And then just getting to work with everybody on all of that was just really nice.” Placement student 4

“I think this is one of the best, if not the best team environment that I've been in.” Placement student 2

“It's definitely changed my opinion of group work, because normally…I don't really enjoy doing group work. It was actually nice to work in a group where everyone like wanted to be there and everyone enjoyed what they were doing.” Placement student 3

Although one student had some concerns about their role within the team environment;

“…worried that I would be seen as not contributing that much as XX is very vocal with their ideas, whereas I am less confident, and their ideas have all been good.” Placement student 5

4.3 Defining the co-production partnership for the live fieldwork broadcast placement

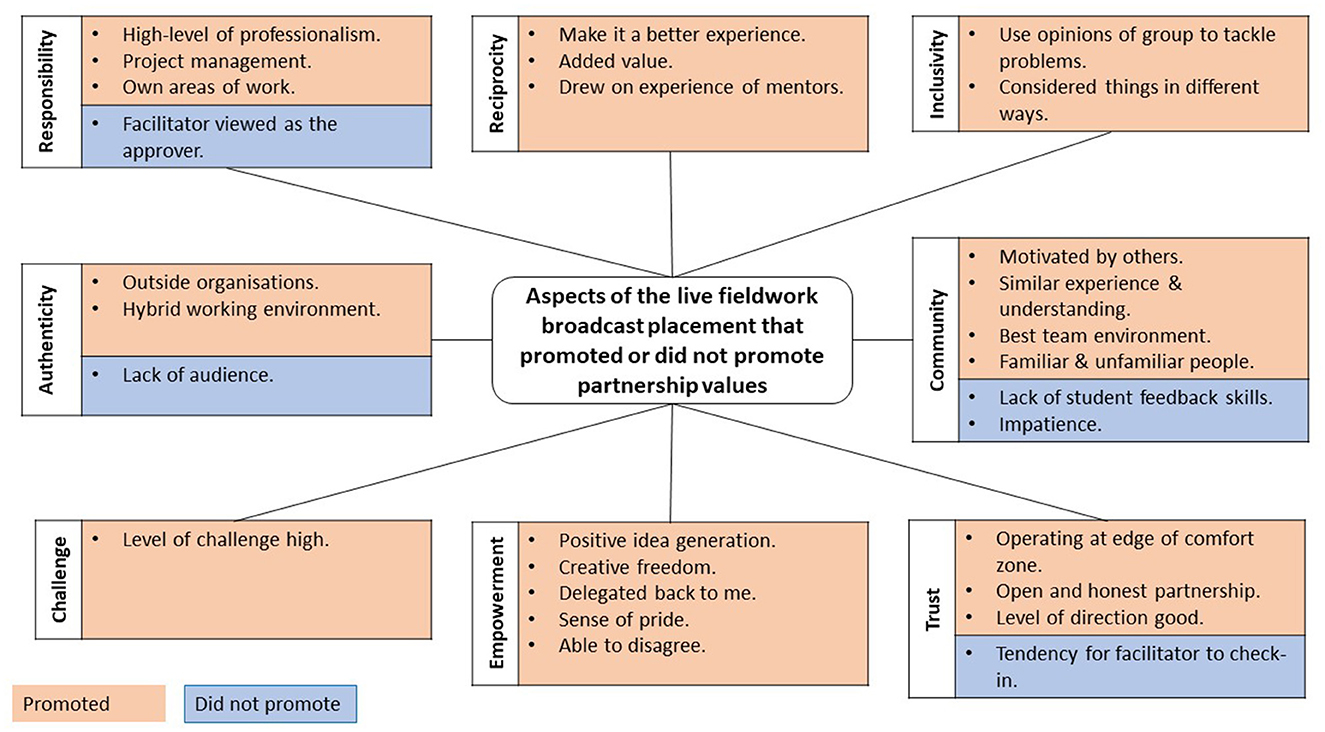

Using values that are defined as integral to a SaP approach (Healey et al., 2016), aspects of the live broadcast placement that promoted a sense of partnership were identified (Figure 4). All eight aspects can be evidenced from student interview data and researcher reflections.

Figure 4. Aspects of the live fieldwork broadcast placement that promoted or did not promote the eight partnership values as identified as integral to a Students as Partners (SaP) approach (Healey et al., 2016).

Empowerment was a partnership value that was strongly evidenced in the data, the idea generation task to determine the theme (Week 1) and storyboarding (Week 2) provided placement students with the ability to the determine the direction of the live broadcast and make decisions on content within it;

“I was shocked that we were able to come up with that many ideas, like all of us, like everyone was included in it…I think it was good because we were all confident enough to share what we were thinking.” Placement student 3

This empowerment was also identified in the researcher reflections where placement students delegated tasks back to the placement facilitator to be completed between sessions, as well as recognizing times when the group were able to disagree and offer alternative suggestions.

Community was an aspect of the live broadcast placement that students drew upon extensively within their interviews, and the positive team environment was identified as a particular area of enjoyment from the project;

“I think we worked, you know, brilliantly together. I think you know the freedom that we had…I think it was (a) perfect level.” Placement student 1

Students reflected that working with other students who had similar levels of experience and understanding was a positive in the partnership and offered opportunities to identify strengths in others and act as a motivator;

“It's quite nice to see a different part of someone who is on the same course as you.” Placement student 2

“They're very productive, so that will then make me more productive.” Placement student 1

There were times within the researcher reflections where it could be identified that the placement facilitator, operated at the edge of their comfort zone; for example, with the use of OBS studio to live produce. The student and facilitator learned together, using outside sources of support, with the student ultimately becoming the expert in that area and teaching aspects of their role back to the placement facilitator;

“Direction is actually quite good, because you let us do our own thing. You let us go ahead…but I know I can come to you if I have any questions…” Placement student 5

During the placement, students each worked on their own areas of responsibility, and effectively managed that aspect of the project. The team showcased a sense of responsibility in the partnership, with students commenting that these project management skills would be useful elsewhere;

“…just sort of seeing how (Trello) would work for future projects.” Placement student 2

And supported them to tackle one of their specific areas of development for the placement (planning and organization):

“…having the sort of independent role on the day…I have to make sure that everything is planned out and organized as much as possible, because no one else can take over for me. So, it is sort of like knowing that it is all on me. Sort of made me make sure that …everything that was possible (is) in place.” Placement student 3

From conception of the project, the co-production of a live fieldwork broadcast in 35 h with novices was identified as a challenge. Ensuring the correct level of challenge within the placement was something that remained present throughout the project;

“It was difficult at the start…it was quite daunting the thought of it.” Placement student 2

It required a strong partnership with good communication and regular check-ins, which asked students to evaluate the current level of direction and suggest changes to meet their needs;

“I think that further down the line, we may want less guidance, but at the moment we are still learning and trying to understand the process, and therefore we should maintain the current level of dependency. However, once we have the hang of it, we may feel comfortable enough to undertake certain tasks by ourselves.” Placement student 4

Although not identified within the student interviews there were three themes from the researcher reflections that did not promote specific partnership values. Firstly, there were times when the placement facilitator was approached by the placement students as the “approver.” This improved over time but did not promote the value of trust within the earlier stages of the project. Secondly although the broadcast was streamed live via YouTube to its audience, the uptake for viewing #NclLive in both years was low (2022–2023–102 views; 2023–2024–45 views). This was disappointing and prevented the partnership from maintaining authenticity as a key value. Finally, there were several times when the placement facilitator felt the need to check-in with the progress of development on several aspects, although these were not all acted on. Upon reflection this stemmed from comparisons of pace and style of working between the placement facilitator and that of the placement students. This was able to be addressed as the partnership developed and the communication tools and styles adapted to suit the needs of the group.

During interviews two and three, placement students were asked to define the level of partnership using a ladder of student participation in curriculum design (Bovill and Bulley, 2011). Students found it challenging to define it absolutely using the categories given, often commenting that their understanding of the partnership was across two descriptors. Table 4 summarizes how students described the project at two stages of the placement. The students did not perceive that it was the “placement facilitator” in charge of their decision-making as their responses aligned to the student control element of the ladder (Table 4).

Table 4. Defining the partnership of the live fieldwork broadcast placement using a ladder of student participation in the curriculum design (Bovill and Bulley, 2011).

During interview two (Week 3) there was a broader definition of partnership from students having control of prescribed areas to students in control. By interview three (Week 7) of the placement, the partnership definition became more tightly defined between “partnership- a negotiated curriculum” and “students in control.” In Week 3, one student commented;

“…obviously we have a massive say in what happens and like what direction it goes in, but obviously you do as well. And you with the PowerPoints and everything you know what you want to happen in the session and we try and get it done. But I think… we've been given us a lot of freedom as well.” Placement student 2

In Week 7, one student described how the partnership was working;

“So I quite like how it's sort of been, it's just sort of like we have to sort of, we work things out for ourselves.” Placement student 3

One student reflected on the collaboration between students and the facilitator within the partnership;

“I would say a partnership as you have pushed us to think about things and come up with our own ideas and solutions, instead of just telling us. However, you have stepped in when we have struggled to think further. You have given us a framework to work in, but it is our choice what we do within that framework. I would say that within the given framework we have worked collaboratively to negotiate the development of the aspects within that.” Placement student 5

4.4 Impact of participating in the live broadcast

Student self-assessment of skill competency of the identified placement skill areas pre- and post-placement gave an indication of the impact of participating in the live fieldwork broadcasts. Figure 5 summarizes the change (pre and post) in the number of competency statements categorized as basic, proficient, and advanced totaled across all placement students' competencies.

Figure 5. Number of competency statements and their level of competency (basic, proficient, advanced) identified pre- and post-placement by the placement students.

Post-placement, there were fewer overall assessments of competency as students commented that some skill areas were not relevant to the objectives that they set for their placement and as such did not rate their competency post-placement in this area. Across all students the number of proficient competency statements remained stable (Figure 5). There was a decrease in basic competency levels and an increase in advanced competency levels (Figure 5), demonstrating the placement had an impact on student reported competencies of skill areas. Post-placement at least one student reported advanced competency level for each skill area (Figure 5), highlighting the value of the individual objectives, with students working on their own areas of development via specific roles and responsibilities during the placement.

Student quotes from the interviews indicated progress against students' own objectives, and the identified development areas of the project. For example regarding the “Communication and liaison” development area one student commented;

“Another objective I had was speaking to experts. So being able to like create (a) sort of a network, and then how to reach out to this network. It did definitely help that you had emailed our experts beforehand saying I was going to contact them… So, I'll have to bear that in mind, for in the future, when I contact people to collaborate with them.” Placement student 4

One student comment indicates progress toward the “Creative thinking and design” development area;

“Initially, I wanted to have like sort of something completely like if it was just my own something like completely novel. But as I sort of went on, I reflected, that that's not, you know. That's not entirely feasible, like in practice. So, I think when I reflected on that, it was then just sort of adding my own elements to that part, instead of creating something that you know (is) entirely new.” Placement student 1

In identifying progress toward “Developing education content to meet a project brief” one student commented;

“In terms of education content. I would say that we are advanced in that because we did think very, you know, thoroughly on what would be the best sort of content to educate people, but also keep them interested. Which was our brief, so I thought what we designed was quite high quality, and we did support the learners during the broadcast.” Placement student 5

Students also made progress in “Digital skills” with one student sharing their experience of video editing and live production;

“I wanted to edit the footage in sort of like an educational way, in like a professional way. And then gain confidence in using the live production software, and obviously meeting those goals, I did a long practice with OBS before the actual broadcast. And videos I'd say we're good. They were clean, and they had all the information they needed to have in them.” Placement student 5

The placement students shared their “Teamwork and collaboration” development;

“I think I surprised myself with like directive on that one, because like it's weird because we're in this dynamic where we're all like seen as equals to each other. It was kind of like I had to step forward, and like kind of take charge.” Placement student 2

One student shared the development of “Project management” skills;

“…like having the sort of independent role on the day it was like. I have to make sure that everything is planned out and organised as much as possible… made me make sure that, like everything like that was possible in place….throughout the placement as well, just little things like when we when we were like making the list of everything we need to do, and then, like sort of sorting it out into like urgency order…so like that helped as well with like prioritizing and organizing things.” Placement student 3

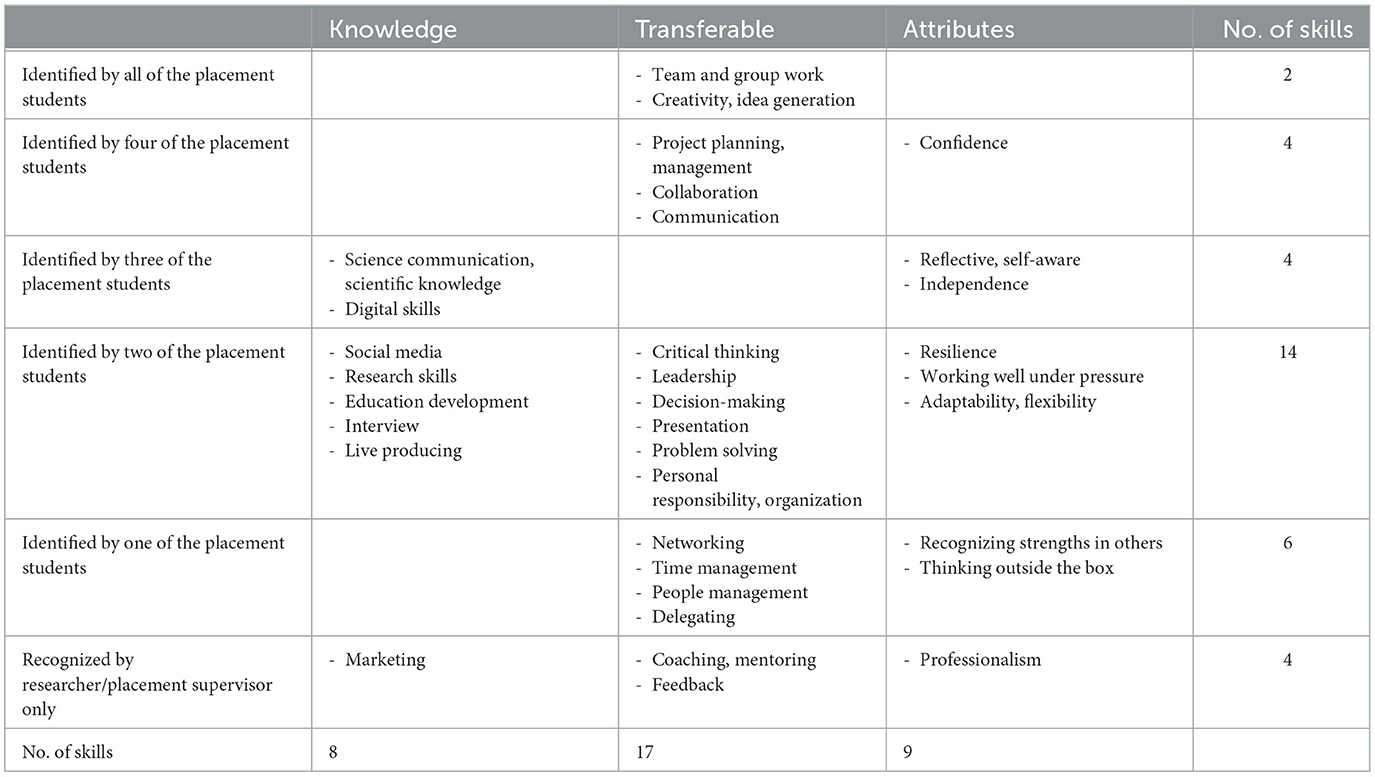

The placement provided students with the opportunity to develop knowledge-based skills, transferable skills, and personal attributes. Table 5 summarizes the skills that students and the placement facilitator identified were developed during the placement. In total, 34 skills were identified. The placement students identified 28 skills, with 73% of skills identified by at least two of the placement students. Most skills developed were transferable, 54% of student identified skills were classified as transferable.

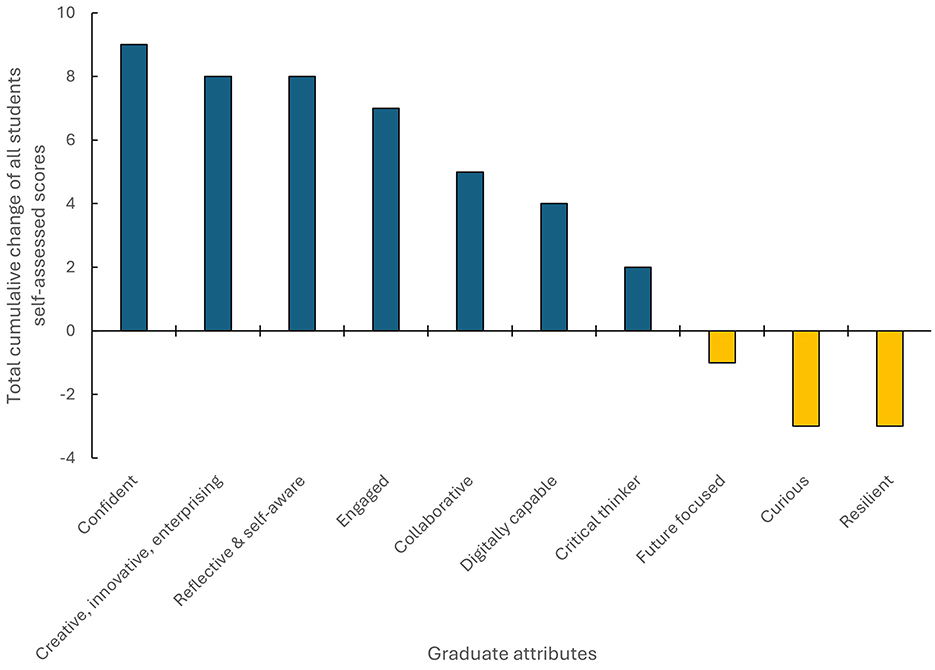

At the start of the placement students scored their capabilities of some graduate attributes on a scale of 0–10. At the end of the placement, students revisited these. Figure 6 shows the cumulative change of all five placement students' self-assessment of these graduate attributes.

Figure 6. Cumulative change in self-assessment scores of graduate attributes. Graduate attributes in blue indicate an increase in the self-assessment scores and those in orange indicate a decrease in the self-assessment scores.

“Confident” was the graduate attribute that had the largest increase in cumulative self-assessed scores (Figure 6);

“I just feel like trying these new skills. And so of as part of working as a team, I feel like I've definitely become more confident and like felt I can make sure I have my own ideas there.” Placement student 5

“I'd say that my confidence is a quite high level. Because of all of the presenting, all of the interviewing the live stuff.” Placement student 4

“Creative, innovative, enterprising” and “Reflective and self-aware” were two graduate attribute areas that also had a large increase in cumulative self-assessed scores;

“I feel like we use some really cool concepts to like use inside the broadcast.” Placement student 5

“I feel like I've learned to sort of check in more and think about, like, oh, maybe this isn't going so well. But we've also got this, and this was good. And so I've been able to like sort of be honest with reflection and also like look at good things, even if they if it isn't going to plan.” Placement student 4

Interestingly despite the live fieldwork broadcast placement adopting digital technologies throughout, placement students did not identify much increase in their self-assessed score for “digitally capable.” This is perhaps a reflection on the distinct roles that students performed during the live broadcast.

Despite two students identifying resilience as a skill they had developed during the broadcast, there was a decrease in the self-assessed scores of the “Resilient” graduate attribute.

4.5 Future role of live broadcasts in fieldwork education

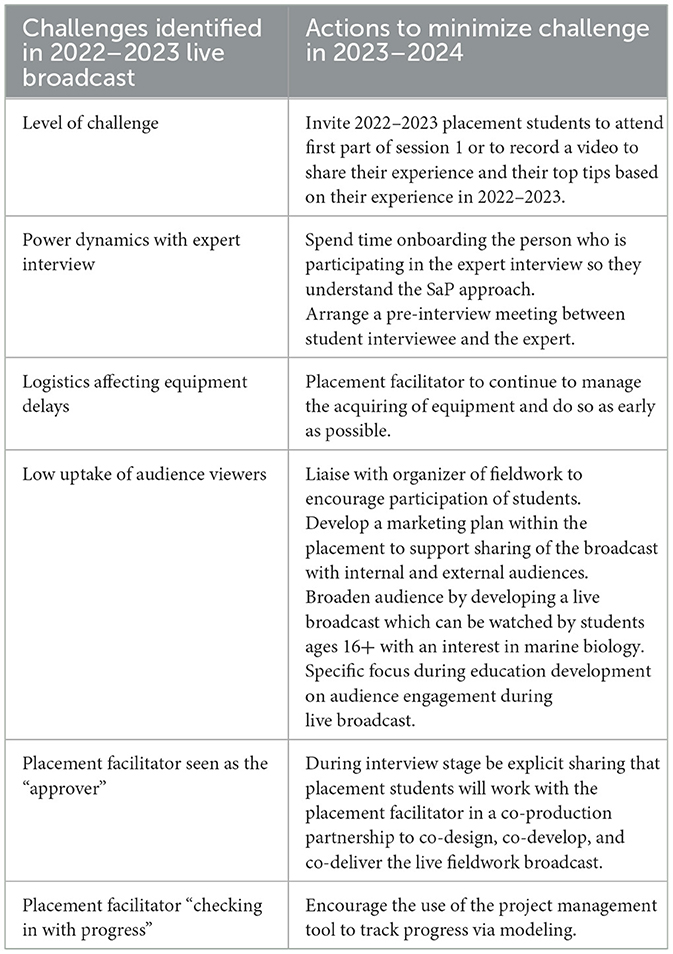

As live broadcast is a novel delivery mechanism in fieldwork, the learnings from the 2022 to 2023 co-production partnership informed the development of the 2023–2024 co-production partnership for the live broadcast (Table 6). The perceived power-dynamics with expert interviewee in 2022–2023, were addressed by more thorough onboarding of those academic staff being interviewed in 2023–2024 with meetings scheduled between placement students and academic staff prior to the interviews taking place. Although the level of challenge was likely to remain the same between years, having the 2022–2023 placement students as mentors to share their experiences and top tips for success would hopefully minimize associated issues with the level of challenge, by supporting the 2023–2024 students that the end-goal of the live fieldwork broadcast was achievable. To avoid the placement facilitator needing to “check-in” with placement students to keep abreast of progress, modeling of effective use of the project management tools to encourage use was undertaken.

Table 6. Iterative development actions based on challenges of 2022–2023 to inform 2023–2024 live broadcast.

Post-placement, students were asked to reflect on future possibilities of live broadcast within biosciences fieldwork and the impact that these might have on learning within HE. One student recognized the value of live broadcast to promote inclusive and accessible bioscience fieldwork opportunities;

“If people aren't comfortable coming into university or if they're in a different country, or they've broken a leg, or just had surgery. They like can't come into the lectures, I think having a live broadcast that you can log into which will make you feel more involved, and you're actually almost like with them and seeing it. Good to increase interconnectedness. Make it more accessible, more engaging.” Placement student 2

Other students saw value in live broadcast enhancing existing learning within their bioscience degree including as an authentic assessment opportunity;

“I think lab work. Because you sort of have lab videos. But they're edited like if it was a dissection or something. I feel like having that live so you could see like exactly how it's the whole process.” Placement student 1

“It could be used as an assessment in a way…I feel like assigning a group and saying, Oh, you've got to create this short like, even if it was just like a 5, 10 min sort of fieldwork task. I feel like a lot of skills are involved in delivering. It's not just doing the field task and how well they did it…it involves everything else behind the scenes as well.” Placement student 5

“…next year the first years wanted to do like a fieldwork. They could speak to one of us, you know, second or third years live in field on how to carry out this field work, and it would be the student carrying out this demonstration. And then, maybe during lectures it could be a student speaking live about what they know about whatever the lectures discussing.” Placement student 4

Reflecting on student suggestions and researcher reflections Figure 7 summarizes some of the future possibilities of live broadcast in bioscience fieldwork and suggests the potential impact of some of these possibilities. These suggestions included the potential to form partnerships with international organizations and research institutions, allowing local experts to deliver live fieldwork broadcasts directly to HE learners, regardless of location and without the need for travel. Additionally, early-career researchers, such as postgraduate and post-doctoral researchers, could broadcast from the field during data collection phases of their research, connecting undergraduate students with the research occurring in their institutions. Finally, equality of access could be improved by offering peer-to-peer broadcasts during overseas fieldwork, helping to minimize barriers to participation.

5 Discussion

The purpose of this research was to identify the feasibility of co-producing a low-cost and low-tech live fieldwork broadcast with undergraduate students via a student placement. The impact of participating in the live broadcast placement is identified with students offering their definitions of the co-production partnership. The future of live fieldwork broadcasting is also discussed.

The low-cost, low-tech solution was effective in networking the fieldwork environment to produce a live fieldwork broadcast. While resource implication (Fletcher et al., 2007; Welsh et al., 2013) and anxiety over the technologies (Welsh et al., 2013) have been identified as barriers to adoption of digital technologies in fieldwork, the use of simple, easy to use technologies have been identified as a way of overcoming these barriers (Maskall et al., 2007). This current research provides evidence to support the view of simple and easy to use technologies supporting integration. Working in partnership, undergraduate students acquired the knowledge and skills to use this simple and easy to use technology to produce a live fieldwork broadcast during the 35 h placement. The schematic shared in this research documenting the flows of information and layers of communication used in a networked environment (Figure 1) is something that has not been presented in other research on live broadcasts in either indoor (Williams et al., 2011; Iwaki et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2022) or outdoor education settings (Cassady et al., 2008; Robert and Lenz, 2009; Fang et al., 2022). Such a model can easily be replicated for other live fieldwork broadcasts both within biosciences and other disciplines with minimal additional costs and/or equipment.

Although live broadcast as a method of educational delivery is well-documented within HE surgical education (Williams et al., 2011; Iwaki et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2022), its use within a Geography, Earth and Environmental Science or bioscience HE fieldwork setting is limited to institutions with remote student populations (Open University, 2023) and specific programs such as GEOspace, which have focused on access and inclusion with Geoscience fieldwork (Marshall et al., 2022), both with heavy resource requirements (staff and technology). Broadening to all educational settings, much of the live broadcast educational delivery involves a delivery model of expert to novice (Cassady et al., 2008; Stagg et al., 2022), and although participation through decision-making during the broadcast can be in-built, there are limited examples of students driving the content of these live fieldwork broadcasts. Utilizing the well-documented benefits of a placement within the biosciences with opportunities to develop business skills (Goddard et al., 2023), improve academic performance (Gomez et al., 2004), and enhance employability (Hejmadi et al., 2012). This research presents a novel application of using a SaP approach to develop a student led peer-peer live fieldwork broadcast within the biosciences.

The placement experience was overall, positive for all participants. With particularly enjoyable aspects relating to the team environment, providing new experiences, and seeing the results of the design process. More challenging aspects of the placement such as uncertainty and unpredictability of live broadcast, education development, and logistics were not insurmountable and did not distract from the overall value of the placement. These challenges were addressed, with placement students identifying a range of knowledge-based skills, transferable skills, and personal attributes throughout the placement. More transferable skills were identified by students during the live fieldwork broadcast placement than knowledge based or personal attributes, this is in line with the work of Peasland et al. (2019), who found that the increased autonomy of student-centered fieldwork resulted in more transferable skills than staff-led fieldwork. Several of the skills developed and identified by students during the placement, e.g., project management and communication, are identified as priority skills from employers to address the skills gaps in STEM and ecological careers (Wakeham Review of STEM Degree Provision and Graduate Employability, 2016; Bartlett and Gomez-Martin, 2017).

Additionally, more explicit links to graduate attributes and how courses of study can contribute to transferable skill development are recommended (Wong et al., 2022) to help embed graduate attributes into specific programs of study (Jones, 2012). This placement provided that authentic opportunity with students developing transferable competencies in leadership and project management (CIEEM's Competency Framework, 2021), although it should be noted that much of these skills or attribute were self-reported by the placement students within this research.

The design of the placement promoted partnership values (Healey et al., 2016), which could be recognized in the student interviews. Although students have been involved in live broadcast work within HE (ChanLin, 2020; Reeves et al., 2022) it is limited; and to the authors knowledge; none have used a SaP approach, with the student experience of this partnership work in live broadcast unexplored. Exploring partnership working is vital to create new spaces for collaboration and dialogue about teaching and learning (Healey et al., 2016). This current research provides rich, detailed information about the student experience of working in partnership to co-produce a live fieldwork broadcast. It uncovers useful information on the value of doing so, and ways of working that promote partnership values. Digital fieldwork approaches have been identified as lacking in learner engagement (Barton, 2020) with them being less learner centered than their fieldwork alternatives (Stagg et al., 2022). The co-design process utilized in the production of the live fieldwork broadcast presents a way of actively involving learners in the co-creation of digital fieldwork content, with the partnership offering authentic peer-peer interaction and co-construction of knowledge as students co-designed, co-developed, and co-delivered the live fieldwork broadcast. Partnership with students in curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy is not well-developed (Healey et al., 2016), in evaluating #NclLive against UCL's Connected Curriculum framework (Fung, 2016), the live fieldwork broadcast placement provided opportunities for students to connect with staff and their research, connect academic learning with work place learning, connect students to each other and create student produced outputs.

Learners defined their participation within the live fieldwork broadcast placement as “students in control” and “partnership—a negotiated curriculum” highlighting a shared responsibility between the placement students and the researcher/placement facilitator, this is identified as a key aspect of improving collaboration between teachers and learners (Könings et al., 2021). The SaP approach within this current research can be conceptualized as both values based practice and counter-narrative (Matthews et al., 2018) with the live fieldwork broadcast placement providing a mutually beneficial learning partnership and reducing power imbalances which have enabled new ways of engaging. However, existing power relationships outside of the immediate partnership of the live fieldwork broadcast were still present within student reflections on this placement, with power imbalances an ongoing area of challenge to continue to address in SaP work (Könings et al., 2021).

The placement students acknowledged the potential of live broadcasting and were able to propose future applications of this approach in fieldwork education, as well as in broader practical science. As a relatively new delivery method with limited coverage in existing literature (Stagg et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2023; Open University, 2023), these proposed roles are valuable for other institutions to explore and adapt for integrating live fieldwork broadcasts in various contexts. The peer-peer live fieldwork broadcast model of working as presented within this research can be used to address some of the identified challenges of fieldwork (Cooke et al., 2020). Firstly, partnerships with overseas institutions could enable fieldwork collaboration between countries tackling the cost, carbon and ethical issues of overseas fieldwork for undergraduate students across disciplines (Smith, 2004; North et al., 2020; Tooth and Viles, 2020). Secondly, live fieldwork broadcasts between early-career researchers and undergraduate students, could provide a cost-effective model of providing research-based fieldwork to enhance the teaching-research nexus, enhance teaching and learning as a whole (Fuller et al., 2014), and provide engagement with the whole life cycle of research (Nicholson, 2011). This link between research and teaching is viewed favorably by both students and academic staff, and can address issues of quality, diversity, and inclusions challenges within HE (The British Academy, 2022).

To the best of the authors' knowledge this research presents the first student co-produced live fieldwork broadcast in Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences (GEES) or biosciences disciplines. It extends the work of the FieldCast team at the Open University (2023; Brown et al., 2023), by presenting a low-cost, low-tech alternative to live broadcasting, offering a replicable model for other institutions. The co-production partnership used to develop the live broadcasts presents a more enhanced approach to involving students in the design of digital tools, with the impact of this co-production partnership shared within this research. Although the communication strategies adopted within live fieldwork broadcasts have been researched elsewhere (Brown et al., 2023), this current research presents information on the student experience and impact of the partnership essential to the successful co-production of the live fieldwork broadcast.

Yet this research presents only a proof of concept, documenting the experiences of just five undergraduate placement students, limited to a single UK HE institution with low audience numbers. However, it presents a model of working which can be replicated to produce a student-centered live fieldwork broadcast. Future research should use the schematics shared within this research to network the field environment, combining this with the logistics of running a student placement to replicate this study in other academic settings, which will add to the small evidence base on the use of live fieldwork broadcasting within the literature (Stagg et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2023; Open University, 2023). This replication should involve rigorous pre-and post-testing of skills, rather than relying on self-reported skill development as in this current research. This research outlines several other potential applications of live fieldwork broadcasts that remain untested. Future live fieldwork broadcasts should aim to test the feasibility and impact of these including; connecting overseas research institutions with HE institutions, linking postgraduate researchers in the field with undergraduates and facilitating connections between students conducting fieldwork in multiple locations.

However, before further developing these live fieldwork broadcasts, future research should focus on methods to increase viewer numbers and engagement. Due to the novelty of live broadcasting in fieldwork, this may require looking toward other applications of live streaming/broadcasting and live interactive polling for inspiration on appropriate approaches (Wang and Li, 2020; Lv et al., 2022) and investigating the suitability of these methods within the live fieldwork broadcast content. This would help to better understand the viewer experience and identify ways to improve the live broadcasts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by School of Natural and Environmental Sciences Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LC: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EF: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CT: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RB: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1463338/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Data Sheet 1 | Placement schedule for 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 live fieldwork broadcast placement, Structure for 1–1s/post-project interviews, competency statements of the eight skills areas of the live broadcast placement and Graduate framework identifying the twelve graduate attributes that students self-assessed their level at the start and end of the placement.

References

Adedokun, O. A., Aull, M., Plonski, P., Rennekamp, D., Shoultz, K., and West, M. (2020). Using Facebook Live to enhance the reach of nutrition education programs. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 52, 1073–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2020.08.005

Atchison, C. L., Marshall, A. M., and Collins, T. D. (2019). A multiple case study of inclusive learning communities enabling active participation in geoscience field courses for students with physical disabilities. J. Geosci. Educ. 67, 472–486. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2019.1600962

Bartlett, D., and Gomez-Martin, E. (2017). “CIEEM skills gap project,” in Practice, 45–47. Available at: https://cieem.net/resource/in-practice-student-articles-cieem-skills-gap-project/ (accessed November 24, 2024).

Barton, D. C. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on field instruction and remote teaching alternatives: results from a survey of instructors. Ecol. Evol. 10, 12499–12507. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6628

Bovill, C., and Bulley, C. J. (2011). “A model of active student participation in curriculum design: exploring desirability and possibility,” in Improving Student Learning (ISL) 18: Global Theories and Local Practices: Institutional, Disciplinary and Cultural Variations. Series: Improving Student Learning (18), ed. C. Rust (Oxford: Oxford Brookes University; Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development), 176–188.

Brandt, H. (2020). A room with a view—using a live surgical procedure as a teaching tool. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 51, 57–59. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20200115-02

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Brown, V., Collins, T., and Braithwaite, N. S. J. (2023). Teaching roles and communication strategies in interactive web broadcasts for practical lab and field work at a distance. Front. Educ. 8:1198169. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1198169

Cassady, J. C., Kozlowski, A. G., and Kommann, M. A. (2008). Electronic field trips as interactive learning events: promoting student learning at a distance. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 19, 439–454.

ChanLin, L.-J. (2020). Engaging university students in an ESL live broadcast. Electr. Lib. 38, 28–43. doi: 10.1108/EL-08-2019-0186

CIEEM's Competency Framework (2021). Available at: https://cieem.net/resource/competency-framework (accessed September 26, 2023).

Clark, K., Welsh, K., Mauchline, A., France, D., Whalley, B., and Park, J. (2020). Do educators realise the value of Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) in fieldwork learning? J. Geogr. High. Educ. 45, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2020.1808880

Cooke, J., Araya, Y., Bacon, K. L., Bagniewska, J. M., Batty, L., Bishop, T. R., et al. (2020). Teaching and learning in ecology: a horizon scan of emerging challenges and solutions. Oikos 130, 15–28. doi: 10.1111/oik.07847

Fang, S., Li, M., Zhang, C., Cheng, H., Zhang, K., Bao, P., et al. (2022). Application of distant live broadcast in clinical anesthesiology teaching. Am. J. Transl. Res. 14, 2073–2080. doi: 10.1155/2021/3098374

Fletcher, S., France, D., Moore, K., and Robinson, G. (2007). Practitioner perspectives on the use of technology in fieldwork teaching. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 31, 19–330. doi: 10.1080/03098260601063719

Fuller, I., Mellor, A., and Entwistle, J. (2014). Combining research-based student fieldwork with staff research to reinforce teaching and learning. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 38, 383–400. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2014.933403

Fung, D. (2016). Engaging students with research through a connected curriculum: an innovative institutional approach. Council Undergrad. Res. Q. 37, 30–35. doi: 10.18833/curq/37/2/4

Goddard, A., Greenhill, S., Rothnie, A., Heritage, J., Holder, L., and Gough, J. (2023). “Embedding business skills through the bioscience placement year,” in Business Teaching Beyond Silos, eds. L. Traczykowski, A. D. Goddard, G. Knight, and E. Vettraino (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 37–48.

Gomez, S., Lush, D., and Clements, M. (2004). Work placements enhance the academic performance of bioscience undergraduates. J. Voc. Educ. Train. 56, 373–385. doi: 10.1080/13636820400200260

Hammond, M. (2013). The contribution of pragmatism to understanding educational action research: value and consequences. Educ. Act. Res. 21, 603–618. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2013.832632

Harrison, M., Short, C., and Roberts, C. (2003). Reflecting on reflective learning: the case of geography, earth and environmental sciences. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 27, 133–152. doi: 10.1080/03098260305678

Healey, M., Flint, A., and Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement Through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. Higher Education Academy. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/engagement-through-partnership-students-partners-learning-and-teaching-higher (accessed October 25, 2023).

Healey, M., Flint, A., and Harrington, K. (2016). Students as partners: reflections on a conceptual model. Teach. Learn. Inquiry 4, 8–20. doi: 10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.2.3

Healey, R. L., and France, D. (2022). ‘Every partnership [… is] an emotional experience': towards a model of partnership support for addressing the emotional challenges of student–staff partnerships. Teach. High. Educ. 8, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.2021391

Hejmadi, M. V., Bullock, K., Gould, V., and Lock, G. D. (2012). Is choosing to go on placement a gamble? Perspectives from bioscience undergraduates. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 37, 605–618. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2011.557714

Iwaki, M., Kanazawa, M., Sunaga, M., Kinoshita, A., and Minakuchi, S. (2013). Live broadcast lectures on complete denture prosthodontics at Tokyo Medical and Dental University: comparison of two years. J. Dent. Educ. 77, 323–330. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.3.tb05473.x

Jones, A. (2012). There is nothing generic about graduate attributes: unpacking the scope of context. J. Further High. Educ. 37, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2011.645466

Könings, K. D., Mordang, S., Smeenk, F., Stassen, L., and Ramani, S. (2021). Learner involvement in the co-creation of teaching and learning: AMEE Guide No. 138. Med. Teach. 43, 924–936. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1838464

Kulgemeyer, C. (2020). A framework of effective science explanation videos informed by criteria for instructional explanations. Res. Sci. Educ. 50, 2441–2462. doi: 10.1007/s11165-018-9787-7

Laaser, W., and Toloza, E. A. (2017). The changing role of the educational video in higher distance education. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 18, 264–276. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i2.3067

Lv, J., Cao, C., Xu, Q., Ni, L., Shao, X., and Shi, Y. (2022). How live streaming interactions and their visual stimuli affect users' sustained engagement behaviour—a comparative experiment using live and virtual live streaming. Sustainability 14:8907. doi: 10.3390/su14148907

Marshall, A. M., Piatek, J. L., Williams, D. A., Gallant, E., Thatcher, S., Elardo, S., et al. (2022). Flexible fieldwork. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3:811. doi: 10.1038/s43017-022-00375-9

Maskall, J., Stokes, A., Truscott, J. B., Bridge, A., Magnier, K., and Calderbank, V. (2007). Supporting fieldwork using information technology. Planet 18, 18–21. doi: 10.11120/plan.2007.00180018

Matthews, K., Dwyer, A., Hine, L., and Turner, J. (2018). Conceptions of students as partners. High. Educ. 76, 957–971. doi: 10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y

Newcastle University (2024). Graduate Framework. Available at: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/careers/skills-and-experience/graduate-framework/ (accessed December 20, 2024).

Nicholson, D. (2011). Embedding research in a field-based module through peer review and assessment for learning. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 35, 529–549. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2011.552104

North, M. A., Hastie, W. W., and Hoyer, L. (2020). Out of Africa: the underrepresentation of African authors in high-impact geoscience literature. Earth Sci. Rev. 208:103262. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103262

Obenson, K. (2021). Increasing engagement of forensic pathologists with the public on social media: could there be room for live broadcasts? Forensic Sci. Int. Synergy 3:100128. doi: 10.1016/j.fsisyn.2020.11.002

Open University (2023). Assessing the ‘Open Field Lab': Evaluating Interactive Fieldcasts for Enhancing Access to Fieldwork. Available at: https://www5.open.ac.uk/scholarship-and-innovation/esteem/projects/themes/technologies-stem-learning/assessing-the-%e2%80%98open-field-lab%e2%80%99-evaluating-interactive (accessed October 23, 2023).

Peasland, E. L., Henri, D. C., Morrell, L. J., and Scott, G. W. (2019). The influence of fieldwork design on student perceptions of skill development during field courses. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 41, 2369–2388. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1679906

Reeves, T., Davidson, N., Ball, J., Courtney, J., and Ella, M. (2022). 191 How do you get work experience during a national lockdown? Arch. Dis. Childh. 107(Suppl. 2), A512–A513. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2022-rcpch.824

Robert, K., and Lenz, A. (2009). Cowboys with cameras: an interactive expedition. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 40, 119–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00807.x

Rogers, K. (2023). Livestreaming. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/technology/livestreaming (accessed September 24, 2023).

Shen, R., Wang, M., and Pan, X. (2008). Increasing interactivity in blended classrooms through a cutting-edge mobile learning system. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 39, 1073–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00778.x

Smith, D. (2004). Issues and trends in higher education biology fieldwork. J. Biol. Educ. 39, 6–10. doi: 10.1080/00219266.2004.9655946

Stagg, B. C, Dillon, J., and Maddison, J. (2022). Expanding the field: using digital to diversify learning in outdoor science. Discip. Interdiscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s43031-022-00047-0

The British Academy (2022). The Teaching-Research Nexus Project Summary. London: The British Academy.

Thomas, G. J., and Munge, B. (2017). Innovative outdoor fieldwork pedagogies in the higher education sector: optimising the use of technology. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 20, 7–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03400998

Tooth, S., and Viles, H. A. (2020). Equality, diversity, inclusion: ensuring a resilient future for geomorphology. Earth Surf. Proc. Landforms 46, 5–11. doi: 10.1002/esp.5026

Trehan, K., and Rigg, C. (2012). Critical reflection – opportunities for action learning. Act. Learn. Res. Pract. 9, 107–109. doi: 10.1080/14767333.2012.687912

Wakeham Review of STEM Degree Provision and Graduate Employability (2016). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a819e68e5274a2e8ab54f6d/ind-16-6-wakeham-review-stem-graduate-employability.pdf (accessed October 25, 2023).

Walker-Cook, A. (2019). Shakespeare and the ‘live' theatre broadcast experience ed. by Aebischer, P., Greenhalgh, S., and Osborne, L. (review). Theatre J. 71, 526–527. doi: 10.1353/tj.2019.0099

Wang, K., Zhang, L., and Ye, L. (2021). A nationwide survey of online teaching strategies in dental education in China. J. Dent. Educ. 85, 28–134. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12413

Wang, M., and Li, D. (2020). What motivates audience comments on live streaming platforms? PLoS ONE 15:e0231255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231255

Welsh, K. E., Mauchline, A. L., Park, J. R., Whalley, W. B., and France, D. (2013). Enhancing fieldwork learning with technology: practitioner's perspectives. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 37, 399–415. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2013.792042

Whitmeyer, S., Atchison, C., and Collins, T. (2020). Using mobile technologies to enhance accessibility and inclusion in field-based learning. GSA Today 30, 4–10. doi: 10.1130/GSATG462A.1

Williams, J. B. M. D., Mathews, R. M. D., and D'Amico, T. A. M. D. (2011). “Reality Surgery” — a research ethics perspective on the live broadcast of surgical procedures. J. Surg. Educ. 68, 58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.08.009

Wong, B., Chiu, Y.-L. T., Copsey-Blake, M., and Nikolopoulou, M. (2022). A mapping of graduate attributes: what can we expect from UK university students? High. Educ. Res. Dev. 41, 1340–1355. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1882405

Wright, S., and Hodge, P. (2012). To be transformed: emotions in cross-cultural, field-based learning in northern australia. J. Geogr. Higher Educ. 36, 355–368. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2011.638708

Keywords: fieldwork, live broadcasting, student placement, students as partners, biosciences

Citation: Maddison J, Constantinou LA, Fletcher E, Turner C, Bevan R and Marsham S (2025) Co-producing a live fieldwork broadcast in the biosciences. Front. Educ. 9:1463338. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1463338

Received: 11 July 2024; Accepted: 10 December 2024;

Published: 13 January 2025.

Edited by:

P. G. Schrader, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United StatesReviewed by:

Emmanuel O. C. Mkpojiogu, Veritas University, NigeriaDerek France, University of Chester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Maddison, Constantinou, Fletcher, Turner, Bevan and Marsham. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Janine Maddison, ai5sLm1hZGRpc29uMkBuZXdjYXN0bGUuYWMudWs=

Janine Maddison

Janine Maddison Leah Ada Constantinou

Leah Ada Constantinou Ellen Fletcher

Ellen Fletcher Callum Turner

Callum Turner Richard Bevan

Richard Bevan Sara Marsham

Sara Marsham