- 1Department of Community and Social Studies, Tokai University, Kumamoto, Japan

- 2Sojo International Learning Center, Sojo University, Kumamoto, Japan

Introduction: This large-scale, mixed-methods study aimed to uncover sources of learner anxiety when interacting in small groups in the language classroom. A secondary aim of the study was to examine relationships between these sources and learners’ levels of small-group anxiety.

Methods: Data was gathered from 1,344 learners enrolled in English classes at four universities in western Japan. Qualitative content analysis was employed to identify anxiety-inducing situations described in learner’ responses, and categorize these situations based on the underlying source of anxiety.

Results: The analysis revealed two primary sources of small-group anxiety: interacting with other learners and L2 communication. The most prominent interaction-related situations were interacting with new people, expressing opinions, and uncomfortable silence, while those related to L2 communication were competence and proficiency, conveying meaning and understanding others. Levels of small-group anxiety were significantly related to the source of anxiety. Learners with a high level of anxiety were twice as likely to cite interaction as the source of their anxiety than learners with a low level of anxiety.

Discussion: The results suggest that interaction anxiety may be more salient than foreign language anxiety when language learners work in small groups, and that the impact of this form of social anxiety needs to be taken into consideration for learners to fully receive the benefits of group work.

1 Introduction

Anxiety in language learning has long been seen as a multifaceted concept, with both debilitating (e.g., Horwitz et al., 1986; Young, 1990, 1991), as well as facilitating aspects (e.g., Kleinmann, 1977; Ohata, 2005), and this emotion has also been noted as a key factor in individual learning outcomes (Dörnyei and Ryan, 2015). The primary focus of research into the impact of anxiety in the language learning classroom has been on foreign language anxiety (FLA; e.g., Dewaele, 2007; Horwitz et al., 1986: Horwitz, 2010; MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012; Matsuda and Gobel, 2004; Yashima et al., 2009), with work focused principally on anxiety’s debilitating aspects and as a factor that inhibits rather than facilitates language learning. Recent work by King and colleagues among others (King, 2013, 2014; King and Smith, 2017; Maher and King, 2020; Maher and King, 2022; Yashima et al., 2016a; Zhou, 2016) has explored the interpersonal and social dimensions of FLA by emphasizing the influence of social anxiety on learners’ experience of FLA. However, studies by Yashima et al. (2016b), Miura (2019) and King et al. (2020) have indicated that in addition to FLA, interaction between learners can itself become a source of anxiety in the language classroom. Moreover, while studies have investigated the role of social anxiety in foreign language learning in the broader context of the language classroom (e.g., King, 2013; Zhou, 2016), they have not examined the impact of this negative emotion in a more specific and common context for language learning activities, that of pair- and group-work. The investigation of anxiety in this context is important as pair- and group-work are central to both communicative and task-based approaches to language teaching (Leeming, 2011), and moreover because these activities are often suggested as countermeasures to the anxiety generated by whole-class activities, such as answering questions or speaking in front of the class (Dörnyei and Murphey, 2004; King and Smith, 2017). King and others have raised awareness of the issue of social anxiety in the language classroom, however, many of these studies have been observational studies (e.g., King, 2013; Maher and King, 2020) and have not investigated the extent of social anxiety quantitatively. Furthermore, while these studies have begun to explore the causes of learners’ anxiety (e.g., Maher and King, 2022), they have done so mainly through interviews of learners, limiting the scale of the investigation. This study represents an attempt to extend the knowledge base in this area by exploring social anxiety in the language classroom from a wider viewpoint. It aims to describe the phenomenon from learner perspectives and uncover those factors, i.e., concrete situations, that engender learners’ feelings of unease when working in small groups.

1.1 Anxiety and language learning

The pride of success, the enjoyment that comes from working with classmates, the frustration of failing to reach a goal, the anxiety of making mistakes, and ever the boredom of repetition—the classroom is indeed an emotion filled environment (Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014), and affect is, without a doubt, an important factor in language learning (Swain, 2013; White, 2018). Positive emotions can open learners up to the language input around them (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014), while conversely, negative emotions can shut learning down (Arnold, 2011; Fredrickson, 2001). One of the most commonly experienced of these negative emotions is anxiety (MacIntyre, 2017; Dörnyei and Ryan, 2015). Williams and Andrade (2008) reported that almost 50% of the learners in their study experienced feelings of anxiety in the language classroom. Horwitz et al. (1986), in their seminal study on anxiety and language learning, found that around one-third of learners were more tense in their language classes than in other classes, were anxious about keeping up with the pace of the class, and felt less competent than other learners, while almost two-thirds expressed worries about making mistakes.

In addition to its ubiquity in the classroom, anxiety is “quite possibly the affective factor that most pervasively obstructs the learning process” (Dörnyei and Ryan, 2015, citing Arnold and Brown, 1999, p. 8), impacting language learners academically, cognitively, and socially (MacIntyre, 2017). Anxiety can have a negative impact on L2 achievement generally, as well as scores in all four areas of language competency, speaking, listening, writing, and reading (Botes et al., 2020). Cognitively, anxiety affects language processing at all three of the stages of input, processing and output (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2000; MacIntyre and Gardner, 1994), and negatively affects L2 acquisition (Zhou, 2016). In the social sphere, anxious learners volunteer answers less often (Horwitz et al., 1986), are less likely to participate (MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012) and are less willing to work in groups (Fushino, 2010a). In addition, anxiety has been linked to lower levels of motivation (Yashima et al., 2009) and willingness to communicate (Liu and Jackson, 2008). Because of its prevalence and impact on learning, anxiety has been one of the most studied negative emotions and is considered to be a “key factor in both the learning and use of an L2” (Dörnyei and Ryan, 2015, p. 32).

Horwitz et al. (1986) were the first to take the broad notion of anxiety and re-conceptualize it into a more situation specific form particular to the language learning context, termed foreign language anxiety (FLA). FLA can be characterized as the “worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (MacIntyre, 1999, p. 27), and is seen to be analogous to, but not composed of, three other forms of anxiety, communication apprehension, fear of negative evaluation, and test anxiety (See Horwitz, 2017 for a discussion on the dimensionality of FLA). Initially, much of the research examined FLA as it manifests in speaking (e.g., Aida, 1994; Horwitz et al., 1986; Young, 1990) and speaking anxiety has remained one of the primary areas of emphasis (e.g., Gregersen and Horwitz, 2002; Liu and Jackson, 2008; King, 2013; Yashima et al., 2016a). However, the range of studies investigating FLA has broadened as well, with a focus on FLA as it is experienced in relation to the other language competencies, reading (e.g., Saito et al., 1999), writing (e.g., Cheng et al., 1999), and listening (e.g., Bekleyen, 2009).

More recently, the scope of research on FLA has been broadened even further. Up to now, most studies on the influence of affect have focused on intrapersonal, or individual, dimensions, rather than interpersonal, or social, ones (Imai, 2010). However, research by King (2013, 2014), King et al. (2020), Maher and King (2022), Yashima et al. (2016b), Zhou (2016) have expanded the investigation of anxiety in the language learning classroom to the interpersonal by examining the influence of the social dimension on speaking anxiety.

1.2 Speaking anxiety and social anxiety

This line of research with began King (2013) investigation of the phenomenon of silence in Japanese L2 classrooms. Using an original observational scheme to collect 48 h of data incorporating over 900 learners in 30 different classrooms from 9 universities, King found that learners remained, “profoundly silent” and “orally inactive” during class (p. 334), with learner-initiated speaking activities taking up less than 1% of class time. King’s extensive observations uncovered a range of factors underlying this dearth of L2 production: lack of opportunity to speak due to the persistence of teacher-centered methodologies; learners’ lack of ability or sense of competence; and their reluctance to speak. Keying in on this third factor, King pointed to the fact that, “Many learners are simply unwilling to engage in the potentially embarrassing behavior of active oral participation for fear of being negatively judged by their peers” (p. 339) and noted that these feelings of hypersensitivity come not only from inside the learners themselves, but also from the social environment of the classroom.

Following up on this, King (2014) undertook an in-depth interview study employing Clark and Wells (1995) model of social anxiety as a framework to further understand the experience of learners who avoid speaking in the language learning classroom due to such fears. Social anxiety can be characterized as feelings of unease or discomfort that “arise from the prospect or presence of interpersonal evaluation in real or imagined social settings” (Leary and Kowalski, 1995), and is a broad term that covers a number of more familiar manifestations of anxiety, such as stage fright, reticence, shyness, communication apprehension and unwillingness to communicate (Leary, 1983a), with these forms differentiated by the situation or context which triggers the feelings of unease. King (2014) found that learners’ silence—their avoidance of L2 oral production—arose from three sources, all of which shared a common element: a concern with being evaluated by others. The first of these was learners’ beliefs, such as the need to speak perfect English, or that mistakes would lead to negative evaluations and even possible rejection by peers. These beliefs helped to create a negative image of the “classroom self” (p. 238), which fed into to the second source of silence, a focus of attention on the self and an excessive concern with how others were perceiving them. The third source of silence was the behaviors learners adopted to avoid situations where they might have to speak English, such as sitting at the back of the class, not initiating discourse, or giving only short responses, in order to escape the feared evaluations of their classmates. These findings led King to conclude that “one of the most salient conceptions of silence for these students is the silence of social anxiety” (p. 244).

Research into the overlap between social anxiety, FLA and the phenomenon of silence have gained prominence following King (2013, 2014) studies, with additional studies extending King’s findings and further examining the social and interpersonal aspects of speaking anxiety (e.g., Maher and King, 2022; King and Smith, 2017; Yashima et al., 2016a,2016b). In one such study, Maher and King (2020) investigated the forms that silence can take in the L2 classroom and the links between these forms and speaking anxiety. Observations of L2 speaking activities highlighted learners’ use of short responses or speaking less than expected, their use of L1—either in place of L2 use or in off-task conversation—and their avoidance of talk or interaction altogether as prominent expressions of silence. Subsequent interviews with participants highlighted the social dimensions underlying these behaviors, such as the influence of a partners’ silence or their use of L1, a dependence on the teacher to push learners to speak, and, as with King (2014), fears of being negatively evaluated by their partner or group members.

Other studies have investigated means of limiting or mitigating the influence of social anxiety on speaking anxiety. Yashima et al. (2016b) aimed to encourage learner-initiated communication and move learners away from the attractor state of silence. Their means of doing this, implemented in a series of 12 classes over one term, was a 20-min class discussion with limited teacher intervention, preceded by discussion of the topic in smaller groups. As a result of this repeated activity, the ratios of silence and learner-initiated talk inverted, with learners speaking for an average of 46% of the time during the discussion (ranging from a low of 19% to a high of 66%), while silence took up only 36% of the time. After each discussion learners were asked to reflect on the factors that encouraged them to speak as well as those that kept them silent. While the topic of the discussion, its difficulty, and its interest to the learners, had the greatest influence on student-initiated discourse, feelings of anxiety were the second most cited factor keeping learners silent, and were mentioned more than twice as often as concerns over language knowledge or competency. This led Yashima et al. (2016b) to conclude that some learners had difficulty in overcoming their feelings of unease even when they were able to express their thoughts and opinions in the L2, and that for such learners, “the issue was more of affect than of English knowledge” (p. 123). This implies that sources of anxiety other than those directly related to the L2 can be powerful factors in the language classroom.

Rather than directly providing learners with more opportunities for oral participation, King et al. (2020) focused on improving classroom atmosphere and interpersonal relationships between learners. It was presumed that creating a social environment where learners felt comfortable enough to speak in the L2 would reduce learners’ silence by helping to ease their feelings of inhibition, social anxiety and concerns with others’ evaluations. To this end, learners first reflected on past language learning experiences, and then discussed situations they felt were likely to trigger anxiety, as well as strategies to handle these negative emotions. Learners were next tasked with organizing an out-of-class activity which allowed them to interact and build relationships in a more relaxed social setting. Pre- and postintervention classroom observations showed that the occurrence of silence decreased significantly, from 9% to less than 1% of class time. Intriguingly, there was a nearly equivalent increase (from 2 to 8%) in what the researchers termed off-class melee—learners interacting in their L1 during tasks—but no significant increase in the amount of L2 oral production. King et al. (2020) interpreted their results as the effect of an enhanced classroom atmosphere where learners became more comfortable with each other, facilitating interaction, which suggests that, rather than reducing learners’ FLA-related speaking anxiety, the intervention was effective in easing learners’ concerns over interacting with their classmates. This finding also strongly suggests that that in addition to learners’ concerns with using the L2 and the possibility of being negative evaluated by their peers, there is another influential source of negative emotion in the language classroom: feelings of anxiety that manifest themselves in social interaction with classmates.

King and others have opened new perspectives on the influence of anxiety in the classroom, with a shift in emphasis from concerns about language to concerns over the social aspects of language use. The primary focus of these studies has been on the phenomenon of silence, or the lack of L2 oral production, emphasizing the social dynamics inherent in speaking anxiety and examining the reasons underlying silence in the classroom. Given this emphasis, these researchers have not been able to fully account for the social dynamics that occur between learners in the classroom, and thus may have overlooked another likely cause of learner anxiety, that is, social interaction itself. This study is thus not framed by a focus on silence and the anxiety that comes with using the L2, but on a broader examination of learners’ experience of social anxiety in the classroom. Therefore, the objective of this study is the investigation of learners’ experience of anxiety when interacting with other learners and the description of this phenomenon from learners’ perspectives. More specifically, this study aims to uncover and describe those factors that learners perceive as engendering feelings of unease when they interact with others in the context of learning a language.

1.3 Interaction and anxiety in the language classroom

The complex nature of anxiety in the language classroom has long been acknowledged, and this multifaceted nature of anxiety as it operates when learners interact in the language classroom forms the conceptual framework of this study. While acknowledging that for some learners, small amounts of anxiety can serve to facilitate performance in the classroom, this study is primarily focused on uncovering those aspects of group work in the language classroom that give rise to other learners’ experience of debilitating anxiety, and in particular their experience of the two forms of anxiety considered below.

In their book on group dynamics, Dörnyei and Murphey (2004) list a number of negative emotions that learners may experience when working with classmates (p. 15): anxieties over using the L2 and their own competence; uncertainty about knowing what to do; lack of confidence and a feeling of awkwardness; and worries over being accepted. The first two in this list are clearly related to what Maher and King (2020) have termed “linguistic knowledge and language competence” (p. 117), and thus are related to speaking anxiety and concerns over language. In contrast, the other emotions in the list are more clearly related to the social context of the classroom, and more general concerns that come from the nature of social interaction itself, which Leary (1983a) terms interaction anxiety. This study thus hypothesizes that concerns over both language use and social interaction will inform learners’ feelings of anxiety when interacting with classmates in the L2 classroom.

First characterized by Leary (1983a), interaction anxiety is a situationally embedded form of social anxiety that manifests in specific types of social interactions, such as a conversation, or small group discussion. The common feature of these forms of interaction is that they are contingent, i.e., they involve situations where an individuals’ actions and reactions are guided by the actions and reactions of the other(s) they are interacting with. Schenkler and Leary (1982) theory of self-presentation provides a theoretical basis for this form of social anxiety. According to this theory, concerns with others’ evaluation and worries over one’s ability to make a desired, usually positive, impression on others underlie all forms of social anxiety. More specifically, these concerns arise from two factors, an individual’s motivation to make a positive impression, and their impression efficacy, the degree of confidence they have in their ability to make the desired impression (Catalino et al., 2012). Either an increase in motivation or a decrease in efficacy can cause a greater degree of anxiety and fear of negative evaluation, and thereby engender feelings of social anxiety.

Leary and Kowalski (1995) outline several situation-specific factors which can heighten an individual’s motivation or lower their sense of efficacy in contingent social interactions. Uncertainty, concerning the proper way to act in a particular social context or situation, creates a sense of doubt and thereby lowers an individual’s sense of efficacy, and is a fundamental factor behind feelings of anxiety in contingent social interactions. An individual’s sense of uncertainty can be amplified in situations that are ambiguous, where the rules guiding behavior are not clear, or novel, where the rules guiding behavior may be unknown. Situations involving strangers not only increase the degree of uncertainty, but also increase the motivation to make a positive impression. Finding oneself the center of attention is another situation which increases motivation, as this increases an individual’s awareness of how others might be perceiving them. These situational factors—uncertainty, ambiguity, novelty, interacting with strangers and becoming the center of attention—are quite similar to the negative emotions described by Dörnyei and Murphey (2004) above, and are also apt for common situations of social interaction of in the classroom, e.g., taking part in new activities with unfamiliar procedures or working with unfamiliar classmates, and thus taking the situational factors underlying interaction anxiety into consideration will help to investigate learners’ perspectives on the experience of anxiety when working with others.

Given the context of the L2 classroom, it is expected that FLA, a domain-specific anxiety concerned with language knowledge and competence as well as with concerns over social performance in the language classroom, will be an important factor underlying learners’ feeling of unease when interacting with others, as well. Sensitivity to evaluations by others is a significant factor behind FLA (King, 2014), particularly in relation to L2 use (Kitano, 2001; Horwitz et al., 1986). Situational factors linked to L2-related evaluative anxiety include worries over troubling classmates (King, 2014), saying something irrelevant or uninteresting (King and Smith, 2017), and making others wait for a response (Maher and King, 2022). Additional situational factors of speaking-related FLA reported in the literature are more closely related to concerns over self-perceived proficiency and competence, and a self-perceived lack of language knowledge. Of those related to concerns over competence, worries over one’s L2 level or ability vis-à-vis classmates is a prominently noted factor (Horwitz et al., 1986; Williams and Andrade, 2008; Young, 1990), as are worries over more general L2 proficiency (Maher and King, 2022), such as using simple or broken L2 (Williams and Andrade, 2008), or not being able to respond quickly (Williams and Andrade, 2008). Concerns over whether others understand what you are saying (Williams and Andrade, 2008), as well as being able to understand one’s classmates (Horwitz et al., 1986; Williams and Andrade, 2008) have been noted as well. Learners’ fears over making mistakes, is well-known and widely reported (e.g., Horwitz et al., 1986; King and Smith, 2017; Young, 1990) and these concerns would seem to be a mix of worries over competence, e.g., saying the wrong thing (Young, 1990), and knowledge, e.g., grammatical errors (Williams and Andrade, 2008). Other knowledge related concerns include insufficient vocabulary (Maher and King, 2020) and concerns over pronunciation (King and Smith, 2017; Williams and Andrade, 2008; Young, 1990). Applying the factors outlined in the literature should further aid in identifying situations that contribute to learners’ experience of anxiety when interacting in the language classroom.

1.4 Interaction anxiety and groupwork

Learner interaction in pairs or small groups is one of the most common situations for social interaction in the language classroom. With the wide-spread use of teaching methodologies that are based on interaction, such as communicative and task-based language teaching (Leeming, 2011), and the emphasis on developing competence (Fushino, 2010a), there has been a significant shift in the social dynamic of the classroom toward a student-centered one where pair- and group-work plays a significant part. Using the L2 productively in pairs and groups encourages language development (Swain et al., 2002), exposes learners to a range of input and provides opportunities for varied output (Zhou, 2016), and aids in the development of communicative competence (Fushino, 2010a).

In addition, working in small groups is often suggested as an antidote to FLA (e.g., Dörnyei and Murphey, 2004; King and Smith, 2017). It has long been accepted that learners prefer working small groups over whole-class activities (e.g., Young, 1990) and more recently the use of group activities have been found to correlate with lower levels of FLA (e.g., Osboe et al., 2007). Working in pairs or small groups allows a degree of trust and acceptance to develop between learners (Dörnyei and Murphey, 2004), encourages more active engagement in the learning process, and creates an atmosphere where learners can notice common interests (Ito et al., 2022), all of which help to ease learners’ feelings of anxiety.

Working in pairs and small groups can facilitate language development and help to lessen feelings of unease for many learners. However, for other learners, this is not the case. For some learners, pair and group work can be a source of anxiety (Maher and King, 2022; Miura, 2019), and the resultant anxiety can hinder their learning (Zhou, 2016). Working in small groups in a student-centered learning environment introduces a more complex social dynamic into the classroom than in a more traditional teacher-centered one. Learners are often asked to take part in new activities, with unfamiliar procedures where the best course of action can be ambiguous, or work with classmates they do not know. When placed in such situations, learners face challenges in communicating with others (Cowden, 2010) and regulating their own emotions (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2011). As Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. (2011) have pointed out, “group processes create unique challenges for leaners” (p. 13) since the social elements of instruction can not only engender strong emotions, but these emotions can function differently in situations where extensive social interaction is necessary, such as in small groups. Collaborating with others demands “relatively high-level communication skills and the ability to engage in spontaneous interaction” (Fushino, 2010a, p. 702). Such situations can be difficult for many learners when working in their L1 (e.g., Archbell and Coplan, 2022; Topham et al., 2016), let alone when attempting to express ideas and opinions, or negotiate meaning and group procedures in the L2, where they have less control over the language (Kȩbłowska, 2012).

For these reasons, this study examines the operation of social anxiety in the context of small group work (hereafter to include both learners working in a pair or in a group of between 3 and 6 learners) in the language learning classroom. There is a sizable literature on the impact of social anxiety on learners in their L1 (e.g., Russell and Shaw, 2009; Russell and Topham, 2012; Topham et al., 2016), as well as the interplay between anxiety and group work (e.g., Cantwell and Andrews, 2002), but very little research has examined the extent of this phenomenon with learners working in small groups in the language learning classroom (see Zhou, 2016; Miura, 2019 for two exceptions). Furthermore, language learners’ experience of social anxiety when interacting in small group work has yet to be examined in depth, and in particular the factors (e.g., situations, antecedents or triggers) that underlie learners’ experience of anxiety in this context remain under-studied. As much of the research into anxiety in the language classroom has “tapped into general/overall attitudes/feelings rather than concrete/specific reactions to actual L2 interactions” (Tóth, 2017, p. 159), this study seeks to uncover learner perspectives on the concrete situational triggers and antecedents underlying the experience of social anxiety in the context of small group work in the language classroom.

1.5 Present study

While research into the effects of social anxiety in language learning has begun, it has focused primarily on speaking anxiety and the phenomenon of silence. The purpose of this paper is to add to the understanding of the complex phenomenon of social anxiety as it operates in the language classroom by focusing on the learners’ experience of interaction anxiety while engaged in small group work. The objective is to investigate the extent of the phenomenon and describe its nature from learners’ perspectives. More specifically, this study aims to uncover and describe those factors and situations that learners perceive as engendering feelings of debilitating anxiety when they work with others in the context of learning a language. This study is therefore framed by the following two research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What are the perceived factors and situational antecedents or triggers that underlie learners’ experience of anxiety when placed in social situations in the language classroom?

RQ2: What is the relationship between social anxiety and these perceived factors?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Design

This study adopted a convergent mixed methods design (Creswell and Creswell, 2018), more specifically, a fully-mixed, qualitative dominant (i.e., analysis of the qualitative data was primary) design (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2009) using an identical convenience sample. The rationale for adopting a mixed methods design was that of significance enhancement (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2010), where the two forms of data are employed to maximize the interpretation of the data. In this study, the use of mixed methods provided complementarity, the elaboration or clarification the results from one method by those from the other method, and triangulation, the corroboration of findings from different methods employed to investigate the same phenomenon.

2.2 Participants and data collections

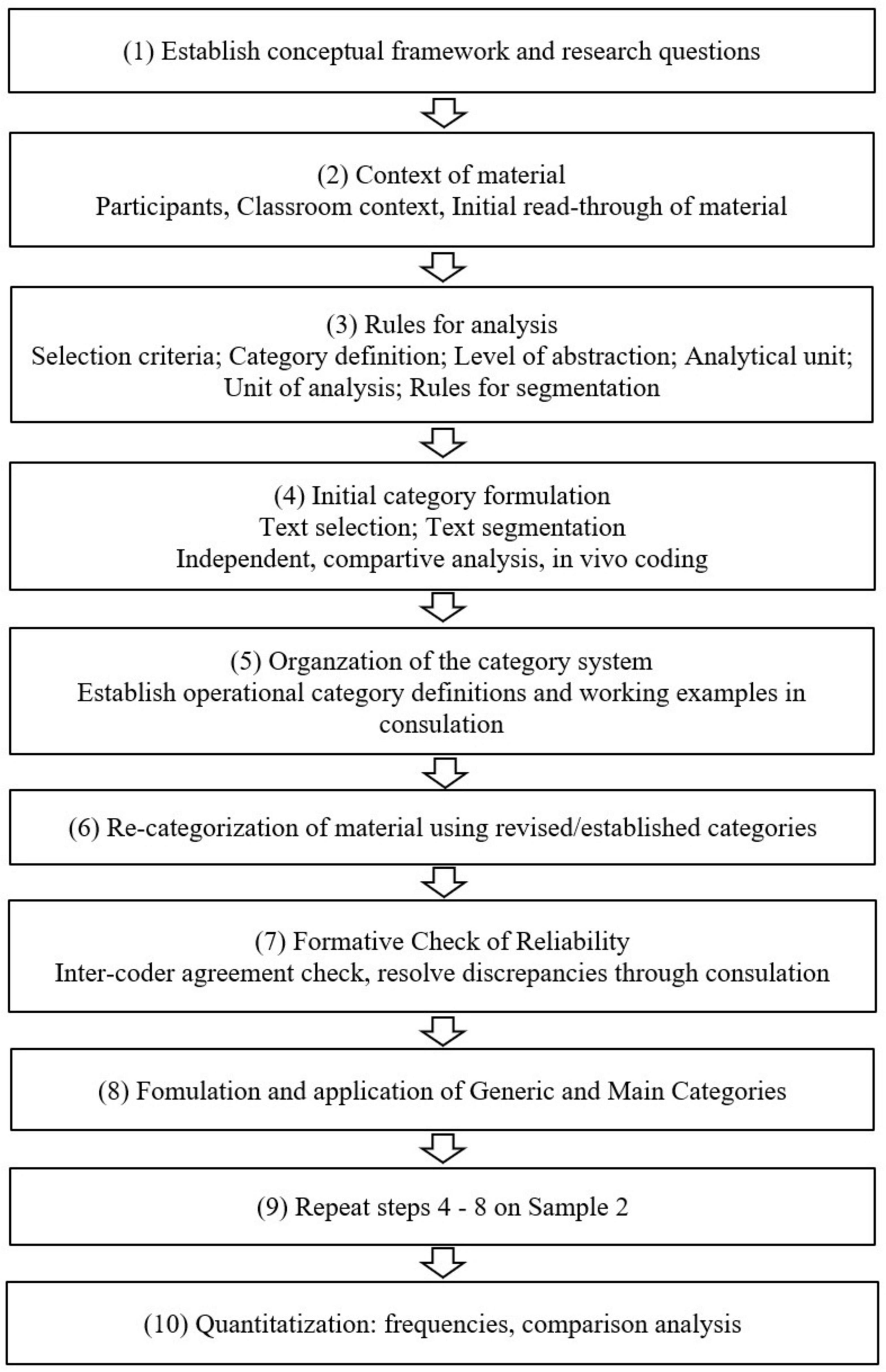

A total of 1,344 Japanese students from four universities, three private and one public, in western Japan took part in this study. Data was gathered in two samples. The first sample (n = 1,124) was collected from late May and early June of 2022. There were 686 male participants (61.0%), 430 female (38.3%), four (0.4%) respondents who considered themselves other, and four (0.4%) who did not disclose their gender in this sample, with an average age of 18.8 years. The second sample (n = 220) was gathered during October of 2022, with 158 male participants (71.8%), 59 female (26.8%), one (0.5%) respondent who considered themselves other, and two (0.2%) who did not disclose their gender in this sample, with an average age of 19.1 years. All participants were enrolled in English communication classes focusing on English as a foreign language and all classes employed pair- or group work. Data was gathered from two samples (see Figure 1), to enhance the credibility and transferability of the qualitative analysis. Qualitative data gathered from the first sample was analyzed and the data gathered from the second sample was used to confirm the results of the analysis. Quantitative data from the two samples was mixed for analysis. The survey was administered using Google Forms, and included a consent form clearly stating that students could decline to participate simply by not submitting the survey, and that non-participation would not have any effect on their course grade. The design of the study and the content of the survey was approved by ethics committees at the authors’ respective institutions.

Figure 1. Qualitative content analysis procedures (Mayring, 2014; Schilling, 2006).

2.3 Instrument

Due to the fact that there is no measure of interaction anxiety as it operates in group work, and that commonly-used measures of more general interaction anxiety, such as the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (Mattick and Clarke, 1998) and the Interaction Anxiousness Scale (Leary, 1983a), include items which describe non-classroom situations, the measure of social anxiety employed in this study was adapted from two scales used by Fushino (2006, 2010a). These scales were developed for use as part of a larger instrument employed to examine relationships between communication apprehension, communication competence, beliefs about group work, and willingness to communicate. The items were developed in reference to studies on the Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (McCroskey and Richmond, 1992; McCroskey et al., 1985a) and its use in Japan (McCroskey et al., 1985b), and focus on a range situations and emotions related to feelings of unease when working in a group in the language classroom. The two scales displayed good reliability, with an item reliability of 0.97 (Fushino, 2006) and Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.88 (Fushino, 2010a), respectively. The scale in this study comprised 14 items, with items rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not at all characteristic of me; 6 = very characteristic of me). In addition to these 14 items, participants were also asked to provide their age and gender.

Finally, participants were asked to answer an open-ended question (based on similar questions used in other studies of learners emotional experience in the classroom, e.g., Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014) to uncover learners’ perspectives on their experiences in small group work: “In as much detail as you can, write about an anxious learning experience you had in group- or pair-work, and how you felt about it.” Response to this question was optional, and participants were encouraged to respond in Japanese in order to ensure they were able to fully express their perceptions. All items and questions on the survey form were presented in Japanese.

2.4 Data analysis

2.4.1 Qualitative analysis

The technique of qualitative content analysis (QCA) was employed for analyzing the qualitative data gathered from Sample 1 and Sample 2. QCA is a systematic, procedural model of analysis that takes the category as its central instrument of analysis and aims to reduce a textual corpus to its core contents or aspects (Mayring, 2014). The model of analysis is based on a set of procedures and rules determined in advance, and in accordance with the goals and purpose of the analysis being carried out. Each step of the analysis as well as the content of the analytic units (i.e., what will be considered a category) and selection criteria are also stipulated in advance. The systematic and pre-defined nature of the analysis allows for transparency in the analysis and also allows for repetition of the analysis (Schilling, 2006). The use of QCA in this study was determined by two factors. First, the qualitative data comprised a large set of responses (n = 603) to an open-ended question on a survey, and furthermore, these responses were overwhelmingly comprised of a single sentence or phrase, rather than longer, more involved responses that would be more amenable to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Second, as one of the aims of QCA is to quantify the results of the qualitative analysis, e.g., the frequency of the categories occurring in the corpus, the authors determined that this would provide insight into the more prominent situational factors that engendered feelings of anxiety in small group work. The procedures and rules underlying the process of analysis are described in detail below to enhance the transparency and dependability of the study.

The analysis initially took an inductive approach, employing the procedures of inductive category formation to categorize learners’ perceptions of anxiety-inducing factors. The data from Sample 1 was analyzed inductively, i.e., the coding and categorization were data-driven and emerged from the data. Following this, the data from Sample 2 was analyzed taking a deductive approach, where the codes and categories from the initial analysis were applied to the data in order to verify the comprehensiveness of the analysis. As the first step (Figure 1), the entire body of responses from Sample 1 were read by all three authors to familiarize themselves with the context of the data set. After reading the text, the selection criteria for the text to be categorized was determined as those responses, or portions of responses which described concrete situational factors underlying anxiety. Responses which did not address this were removed from the analysis. The level of abstraction was set as concrete factors connected with the experience of anxiety by the learner, and not a more general description of a feeling of anxiety, nor a description of anxious situations for other learners. A category was pre-defined as a student-perceived situational factor which learners perceive as engendering feelings of unease when working in pairs or groups. The coding unit was a sentence or phrase noting one concrete factor. The context unit was each individual response, with the recording unit set as all the relevant responses from the total corpus of responses. The basis for segmenting the text was a sentence or phrase which explicitly mentioned a factor, and responses with multiple sentences or which clearly mentioned more than one factor were split into separate segments. A small number of responses (n = 8) contained more complex thoughts and thus were double coded without being split into smaller segments. The coding unit, context unit, recording unit and segmenting rule were also applied to Sample 2.

After deciding on the procedures, all responses were analyzed by each author independently, using in-vivo, open coding following a process of constant comparison (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2010). After this step was completed, the three authors agreed upon a common set of categories to be applied to the corpus through a process of consultation, where each category was defined and examples chosen (Mayring, 2014). The data was then re-analyzed by all three authors using this category scheme, with discrepancies and disagreements resolved through consultation (Schilling, 2006). The categories themselves were then analyzed and classified into generic categories and main categories through a process of reduction (Mayring, 2014).

A similar process was followed for Sample 2, where the entire text was read, relevant responses selected based on the criteria, and segmented following the rule for segmentation. However, rather than an inductive process, responses were coded deductively using the categories developed in the analysis of Sample 1. Each of the authors categorized the data independently and discrepancies and disagreements were resolved through consultation. No new categories were developed from the data in Sample 2.

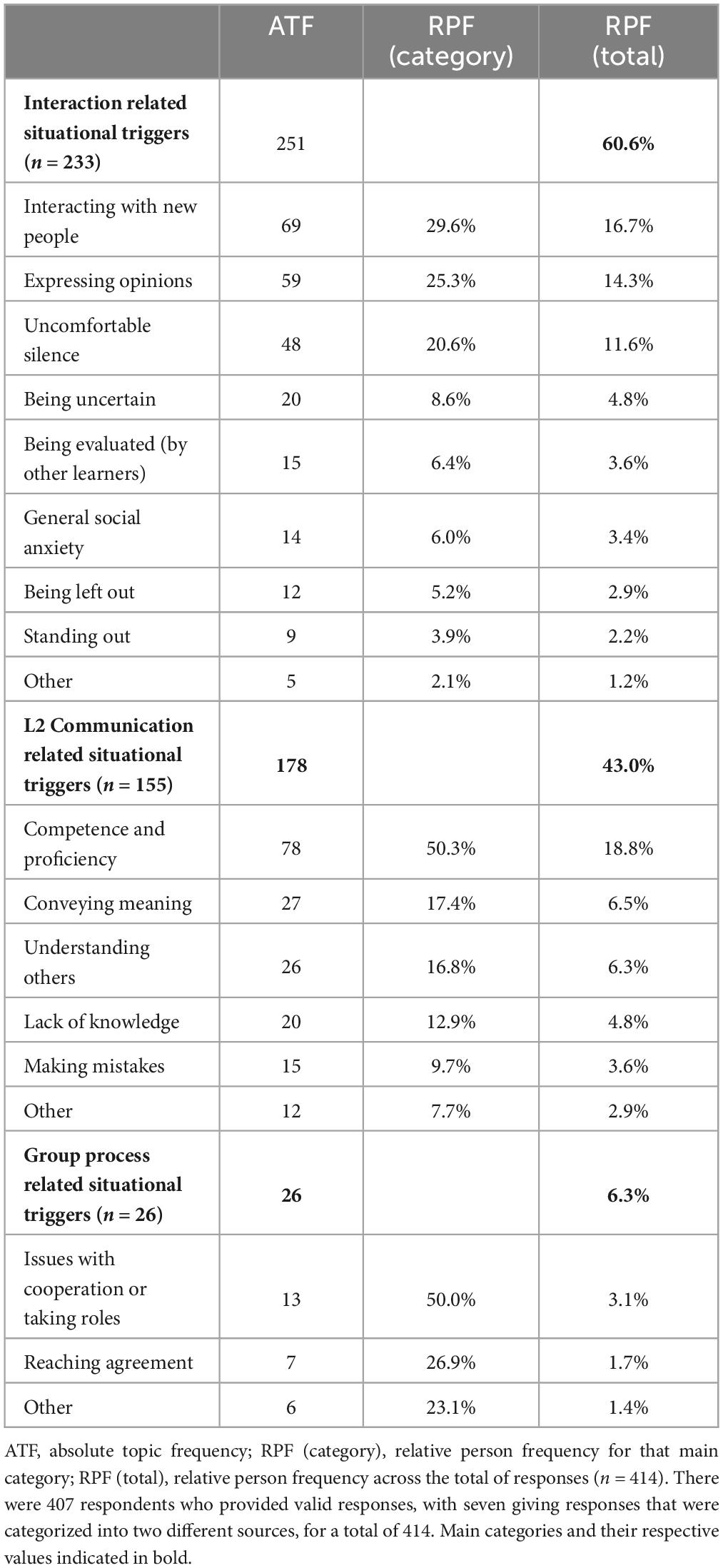

After the qualitative analysis, the results were quantitized (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998) and absolute topic frequencies, that is the number of times each category occurred in the corpus, as well as relative person frequencies (the percentage of respondents who mentioned a particular category) were calculated (Table 1). In addition, the quantitized data was employed in the comparative analyses described below.

2.4.2 Quantitative analysis

For the quantitative analysis, the data from each sample was screened for the presence of univariate and multivariate outliers, and the normality and linearity were checked. Descriptive statistics for the demographic information (age, gender) and each Likert-scale item were calculated using SPSS (v.28). As the instrument used to measure anxiety in this study combined items from two different versions of the instrument (Fushino, 2006, 2010a), and has never been used as a stand-alone instrument for measuring communication apprehension in group work, the validity and reliability of the instrument were determined through a process of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (described in detail in the Supplementary file). The resulting instrument was used to calculate subscale scores and average scores on each subscale to facilitate comparison between scores on the subscales, as each had a differing number of items. The distribution on both subscales was found to be non-normal and thus non-parametric statistics were employed. Spearman’s rho was employed to determine the degree of correlation between the two subscales. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine differences between learners on the subscale scores. Differences in scores based on gender were examined using the Mann-Whitney u-test.

At this point in the analysis, the two data sets were combined and employed in a comparative analysis. First, learners were organized into two groups based on the main category of the anxiety-inducing situation they cited, and scores on each subscale were compared for learners in each group using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Following this, learners were grouped into high and low groups, based on their subscale scores, with learners in the 1st quartile placed in the low group and those in the 4th quartile in the high group. Differences in the prevalence of anxiety-inducing factors between learners in the high and low groups were compared using the chi-square. Finally, the chi-square test was also used to investigate differences in the prevalence of anxiety-inducing factors based on gender.

3 Results

3.1 Qualitative analysis

A total of 603 learners (44.8%) provided responses to the open-ended question. In Sample 1, there were 511 responses, of which 147 (28.8%) stated they felt no particular anxiety in small group work, while 14 (2.7%) were not relevant or commented on positive aspects of small group work. These were removed from the analysis, leaving 350 (68.5%) responses to be analyzed. In Sample 2 there were 92 responses, with 35 (38.1%) who felt no anxiety, and none non-relevant or positive, leaving 57 (61.9%) responses to be analyzed. The total of 407 responses had an average length of 29.3 Japanese characters per response. Most of the responses (360 or 88.5%) were relatively short and described only one situational factor. These responses were coded as single segments. Forty responses described more than one situational factor, and so were split into two or more segments. Seven additional responses described more complex situations and so were double coded without being split. As a result, the 407 valid responses were divided into 455 coded segments to develop the category system. This comprised 18 generic categories organized into three main categories as shown in Table 1 along with the absolute topic frequencies and relative person frequencies. The findings presented below focus on interaction related situations due to the focus of the study and the lack of research into these situational triggers of anxiety, in contrast to the more extensive research on the sources of FLA (e.g., Maher and King, 2022; Williams and Andrade, 2008; Young, 1990).

Consistent with the conceptual framework of the study, learners reported a range of interaction related situations as sources of anxiety when doing small group work. Included in this main category were nine categories of situations that triggered feelings of unease when interacting with classmates. The three most prominent of these from learners’ perspectives were interacting with new people, expressing opinions, and uncomfortable silence.

The first category was operationally defined as situations where learners indicated speaking and/or working with unknown or unfamiliar partners or group members as the source of their anxiety. These included situations where they were interacting with classmates who were complete strangers to them or those whose names they merely did not know. When faced with these situations learners reported that they were unsure of what to talk about, became reticent, and wanted to do as little as possible, as seen as in this response, (numbers in parentheses are the ID number given to each learner’s response) “I get very nervous when I ask questions to people I have never talked to before, or conversely, when I am asked questions, and I become strangely reserved.” (1243). The underlying source of these emotions and the resultant actions was a feeling of distance from the unfamiliar partner and not knowing what kind of person they were, as a result making it difficult to facilitate a conversation, to know where to start, or to find a topic to talk about, e.g., “When you are in the same group with someone you don’t know at all, especially at first contact, you get very nervous. Once you get used to it, you get to know the person’s personality and your nervousness dissolves, but until then, you will be nervous!” (2199).

Situations where learners described feelings of unease arising from having to express opinions were the next most salient category. In addition to more general concerns over giving one’s opinion, anxiousness over differing opinions predominated this category. Whether it was that their own opinion differed or others’ differed, both were seen as anxiety inducing, though one’s own opinion differing was mentioned more often. More specifically, learners described situations where they felt they had made a mistake, or where they felt others could not relate to their opinion. The possibility or actuality of others’ evaluation in such situations was also indicated as a strong factor. Learners noted the silence that occurred after giving an opinion deemed to be “off the mark” (e.g., 181, 1192, 1304), as well as feeling the “eyes of the others upon you” (1362), and more generally, the atmosphere of disapproval that came with an opinion being rejected by the others in the group. In addition, the pressure of having to come up with an opinion and situations where others have expressed better opinions than one’s own were cited.

The category uncomfortable silence was defined as situations portraying the occurrence of a break in interaction and the ensuing silence that arose from a sense of not knowing what to do next. This included several types of situations. First, periods of awkward silence that occurred when the conversation came to a halt, e.g., “When you finish early and stop talking” (129), or when learners felt that they had run out things to say, e.g., “When the conversation become a bit stagnant” (168). In addition, learners frequently mentioned feeling uneasy over difficulties in initiating interaction and the silence that resulted, e.g., “When no one says anything, I feel awkward because I have to either start the conversation or remain silent” (115). A more threating form of silence was situations where partners did not respond to what was said, as in these examples, “If the other person doesn’t respond when I’m talking to them, I don’t get a sense of their intentions and I feel uneasy” (257), “I get worried when the other person doesn’t talk to me, and if the other person isn’t motivated, I feel less motivated too.” (1355), or did not actively participate in the group activity, “I felt uneasy when one of the group members rarely spoke and did not participate in the conversation” (1332).

Learners mentioned a range of other less prominent situations that engendered feelings of unease. The first of these was being uncertain over what to do, where learners found themselves in situations where the best course of action was unclear, such as when to join in a discussion, as in this example “When other members were having a lively discussion, I felt anxious because I didn’t know if it was okay to express my opinion” (1214). Learners also highlighted situations where they felt they were being evaluated by others, for instance, “I worry if they don’t like me” (127), “I am not sure what people think of me when I speak, and I feel insecure” (1161), and “I’m afraid that when I say something, they will react like, ‘What?’, I’m afraid of getting a reaction like ‘What?’” (252). Perhaps relatedly, a number of learners reported feeling anxious when they felt they were being ignored or excluded from the group in some way, e.g., “When I was the only one in a group with no friends and everyone else was close.” (209) and “Some people would ignore me.” (240), or when they became the center of attention or felt they were standing out from others, such as in this example, “I was speechless and felt very embarrassed in front of everyone.” (221). Finally, situations precipitating more general social anxieties, such as interacting with other genders, partners of different ages or a more general feeling of unease over interacting with others were noted as well.

A range of situational triggers related to communication in the L2 in small group work were also reported, in line with the conceptual framework. The most prominent were situations related to proficiency and competence, where learners described not having the language skills to fully express their ideas or respond to others, i.e., situations where their self-perceived language competency created difficulties in communication. An inability to express oneself in English was most often noted, as in these responses, “I couldn’t carry on a conversation and didn’t know what to say” (1216) and “I feel bad for the silence when I am thinking about what I want to say, because I can’t put what I want to say into English” (1212). Feeling as if one was unable to answer quickly to a partner was also highlighted frequently, e.g., “I’m in a hurry because I can’t find the words. That’s what makes me a little uneasy” (152). Less prevalently, learners mentioned a more general feeling of being less proficient than their others in their group, “I’m not very good at English, so when I see people around me speaking in a relaxed manner, I get worried that I’m not good enough and causing trouble” (1182). Situations where learners expressed concerns over conveying meaning were also frequently cited as sources of unease, with learners anxious about whether or not the language they used was understood by others, for example, “I don’t know if I am communicating exactly what I want to say to the other person” (1214). Conversely, unease over understanding others was also salient, e.g., “When you don’t understand English and you feel overwhelmed” (274). Other less prominent situations included those where learners felt their lack of knowledge, e.g., “I felt uneasy in situations where I did not know the meaning or pronunciation of a word when asking a question to the other person” (110), or a fear of making mistakes, “I’m worried that I might cause trouble if I make a mistake” (149) created difficulties. Concerns over pronunciation and a fear of causing trouble for others were also noted by a few learners.

Finally, a small number of learners mentioned situations involving process related aspects of small group work as sources of their anxiety. Principal among these were issues with cooperation or taking roles, with worries related to difficulties in reaching agreement also cited.

3.2 Quantitative analysis

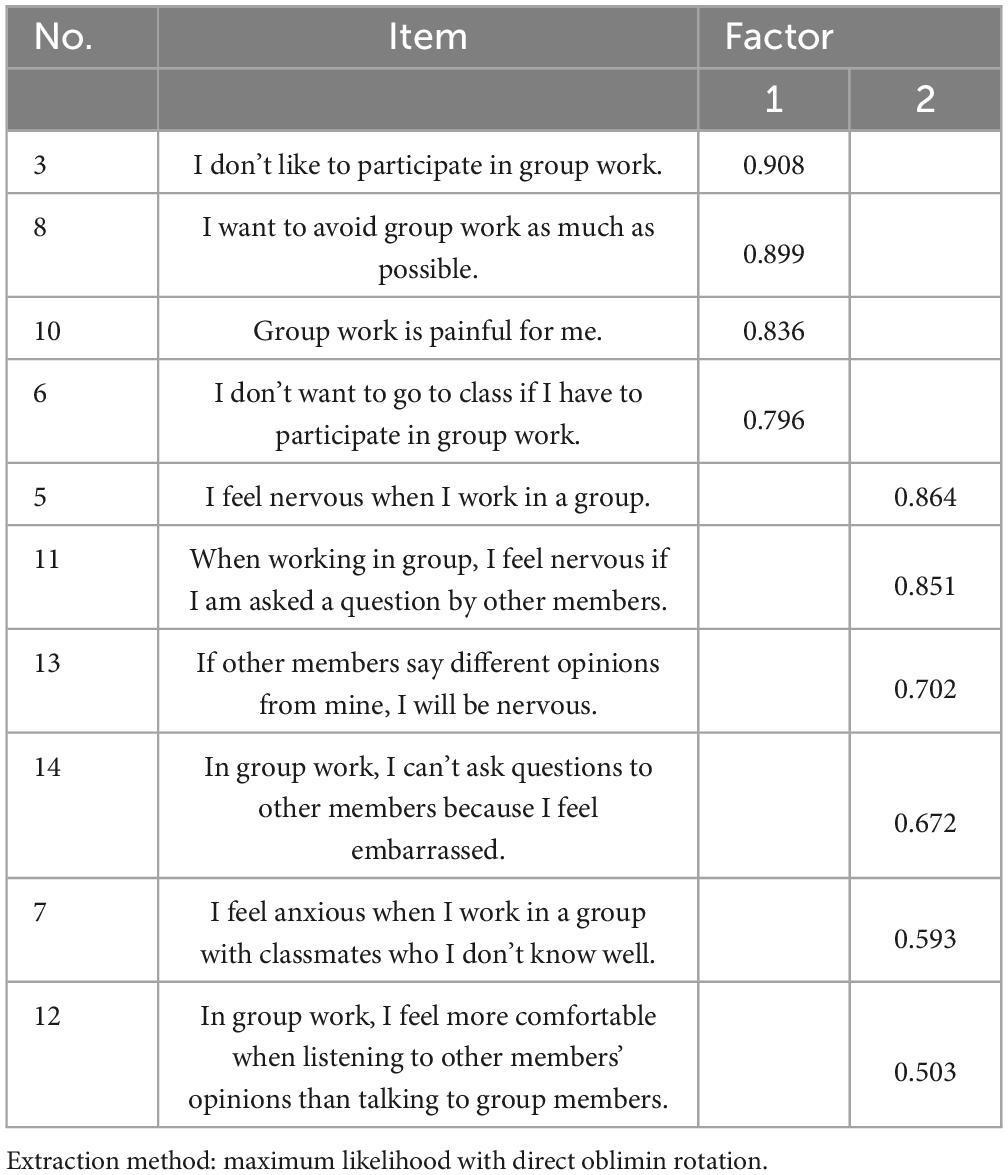

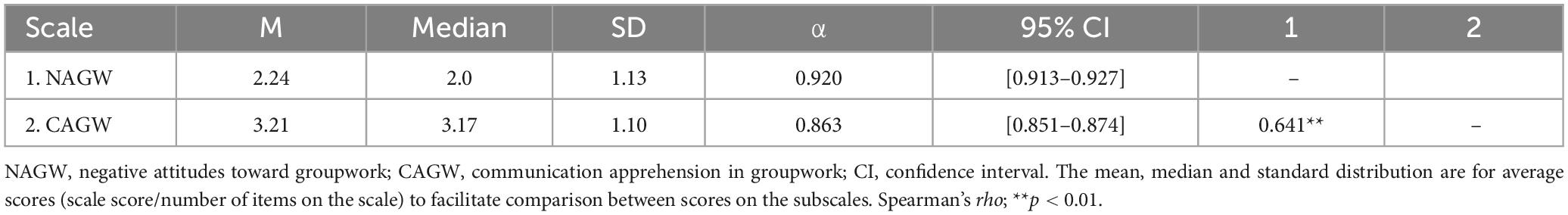

A process of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (described in detail in the Supplementary file) resulted in a two-factor scale with acceptable fit [χ2 (34) = 75.3, p < 0.001; TLI = 0.976; CFI = 0.966; RMSEA 0.075; SRMR = 0.047], whose items are shown in Table 2. Those loading on the first factor comprised items concerning a more generalized dislike of group-work, such as wanting to avoid group work or feeling it is rather difficult, and thus the factor was named Negative Attitudes Toward Group-work (NAGW). Items on the second factor concerned feelings of unease in situations related to interpersonal communication, such as asking an answering questions, or expressing opinions, and thus the factor was termed Communication Apprehension in Group-work (CAGW). The Cronbach’s alpha for the NAGW subscale was 0.920, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.913 to 0.927, while that for the CAGW subscale was 0.863 (95% CI = 0.851–0.874), and so both were considered to possess a sufficient degree of reliability (Table 3).

Average scores (scale score/number of items on the scale) were calculated to facilitate comparison between scores on each factor, as well as means, standard deviations and medians for these scores. The distribution of these scores was found to be non-normal on the basis of One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Tests together with inspection of the Q-Q plots, and therefore, Spearman’s rho was used to investigate the relationship between NAGW and CAGW. The two subscales were found to be significantly positively correlated [r(1,332) = 0.641, p < 0.001], sharing 41% of variance, which indicates a substantial relationship between the two (Plonsky and Oswald, 2014).

The Wilcoxon Signed-rank test was used to compare learners’ scores on the two scales. The results (z = −27.45, p < 0.001) showed that learners reported significantly higher CAGW (Md = 3.17) than NAGW (Md = 2.00), with a medium to large effect size (r = 0.54) using Plonsky and Oswald (2014) revised values for effect sizes (small = 0.25; medium = 0.40; large = 0.60), which suggests that these learners do not have a strong dislike for group work, but do possess a degree of unease when communicating with others in a group. Furthermore, 362 learners (27.01%) had CAGW scores > 4, and 98 (7.3%) had scores > 5, suggesting that a considerable number of learners (34%) experience feelings of anxiety when placed in group work situations. Conversely, only about one-third this number (132, or 9.5%) reported NAGW scores > 4.

Gender differences in scores on the two scales were examined using the Mann-Whitney U-test. For the NAGW females (Md = 2.25) had significantly higher scores (U = 179,903, z = −3.78, p < 0.001) than males (Md = 2.00), but with a very small effect size, r = 0.10 (Plonsky and Oswald, 2014). Similarly, females (Md = 3.50) reported significantly higher scores (U = 159,427, z = −6.79, p < 0.001) than males (Md = 3.00), with a slightly larger effect size, r = 0.19. The small effect sizes in both cases suggest that, while there is a difference, and that females experience more anxiety when working in groups, the difference is not great.

3.3 Qualitative-quantitative combined analysis

The quantitized results from the qualitative analysis were combined with learners’ scores on the two scales to conduct a series of comparative analyses. First, learners were divided into two groups based on the main category of their response, i.e., Interaction (n = 228) or Communication (n = 149), and their scores on the two scales were compared. Mann-Whitney U-tests showed no significant differences on either the NAGW (U = 15,741, z = −1.21, p = 0.227) or CAGW (U = 14,358, z = −2.55, p = 0.011) subscales, with very small effect sizes, r = 0.06 and r = 0.13, respectively. This suggests that learners’ attitude toward group is not affected by the source of their anxiety, and also that the CAGW subscale, the items for which were developed with the aim of measuring communication apprehension as it operates in small group work, is not able to discriminate between the two broad sources anxiety very well.

Next, the chi-square was used to compare differences in the main category of anxiety mentioned by learners with high (4th quartile; n = 97) and low (1st quartile; n = 93) scores on the CAGW subscale. There was a significant association between learners CAGW scores and the main category of anxiety they cited [χ2(1) = 5.399, p = 0.02], indicating that learners with high scores were significantly more likely to cite interaction related sources of anxiety than those with low scores. More specifically, the odds ratio showed that learners with high scores were twice as likely to cite interaction sources, and conversely that learners with low scores were twice as likely to cite communication related sources. Differences in category mentioned by gender were examined as well. A significant association was found between gender (M or F) and the source of anxiety cited [χ2(1) = 8.354, p = 0.004], with female respondents were more likely to cite interaction related sources of anxiety than males. Females were almost twice (1.88) as likely to cite such sources, while males scores were almost twice as likely to cite communication related sources according to the odds ratio.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to contribute to the understanding of the complex, multifaceted nature of social anxiety in the language classroom by employing a mixed-method design to investigate the phenomenon and describe its nature from learners’ perspectives. It has extended recent research on the nature of anxiety and its impact on learner engagement in the language classroom (e.g., King et al., 2020; Miura, 2019; Yashima et al., 2016b; Zhou, 2016) by taking social anxiety and particularly, interaction anxiety, into greater consideration, and focusing on learners’ experience of anxiety while engaged in small group work to uncover concrete situational triggers of learners’ anxiety in this context. The relationship between these situational triggers and learner self-reported levels of small-group communication anxiety was also examined. For this purpose, the study combined a conceptual framework centered on interaction anxiety and FLA to categorize learners’ descriptions of anxiety-inducing situations using QCA with a quantitative measure of communication apprehension in group work.

As a result of the qualitative analysis, three data-driven and theoretically grounded categories of situations contributing to learner anxiety in small group work were identified. The most frequently mentioned category comprised situations involving interaction with other learners. Situations involving the use of the L2 in communication were less-frequently cited, and the third category, situations involving concerns with group processes, mentioned by only a small number of learners. Anxiety coming from interaction with other learners represents an under-recognized source of anxiety in small group work, as well as language learning more generally (Zhou, 2016). Previous research on the sources of anxiety in the language learning classroom (e.g., Maher and King, 2022; Williams and Andrade, 2008; Young, 1990) have focused more on the antecedents of foreign language anxiety, rather than anxiety engendered by interaction with other learners. The fact that situations involving interaction with others were the most commonly cited situational triggers of anxiety in small group work—accounting for 60% of coded responses by relative person frequency— indicates that this is an important factor in learners’ perceptions of anxiety when working in small groups.

Analysis of the quantitative data corroborated and complemented the qualitive results. While learners reported a relatively positive attitude toward small group work (i.e., they had low scores on a measure of negative attitudes toward group work), they also reported considerable unease at the prospect of interacting with others in this context, with 34% of learners reporting that experiencing feelings of unease when working in small groups were characteristic or very characteristic of them. This finding is in accordance with research examining the impact of social anxiety in the L1 classroom, where 25.5% of learners reported that working in groups was associated with frequent social anxiety (Russell and Topham, 2012), and 33.1% of learners avoid participating in small groups at least occasionally (Russell and Shaw, 2009). Furthermore, a connection between scores on the measure of small-group communication apprehension and learner’s self-reported situational trigger of anxiety was found when the results of the qualitative analysis were quantitized and combined with the qualitative data. Two groups of learners were compared on the basis of their scores, and learners with scores in the highest quartile were found to be twice as likely to cite interaction-related situational-triggers, while those in the lowest quartile were twice as likely to cite communication-related situational triggers. This triangulation and corroboration of quantitative and qualitative results not only adds to the credibility and trustworthiness of the qualitative findings, but also underlines the salience of interaction related situations as triggers of learner anxiety, and the need for further research in this area.

Below, the findings are discussed in relation to the conceptual framework of the study, with the primary focus on interaction related situations due to their prominence and the lack of research in this area, as opposed to research examining the sources of FLA (e.g., Maher and King, 2022; Williams and Andrade, 2008). Taking the theory of self-presentation (Schenkler and Leary, 1982) as the primary theoretical framework underlying interaction anxiety, the findings are considered in terms of the situation-specific factors—interacting with strangers, becoming the center of attention, uncertainty, ambiguity or novelty—that underlie feelings of anxiety in contingent social interactions. As discussed above, contingent interactions are those where learners’ actions and reactions are based on the actions and reactions of the other learners they are interacting with, such as in small group work. According to the self-presentation theory of social anxiety, concerns with others’ evaluation underlie feelings of social anxiety, and anxiety is experienced when the motivation to make a desired impression increases, or the sense of efficacy to make the desired impression decreases. Situational factors such as those above can heighten motivation or lower the sense of efficacy and give rise to feelings of anxiety.

Consistent with self-presentation theory, interacting with new people was a particularly salient trigger of learner anxiety (e.g., Catalino et al., 2012; Leary, 1983b; Leary and Kowalski, 1995), and the most frequently cited category. Working or speaking with unfamiliar classmates, whose actions and reactions are therefore difficult to predict, gives rise to situations ripe with the potential for learners to experience a sense of unease. These situations are doubly dangerous as they both raise the degree of uncertainty and heighten motivation to make a desired impression on the unfamiliar other. Moreover, such situations frequently occur when learners engage in small group work, and thus the prominence of this situational trigger further emphasizes the importance of taking time to develop relationships between learners before placing them in small groups (Dörnyei and Murphey, 2004; King et al., 2020), as for example through the sharing of information in low-risk self-disclosure activities (King and Smith, 2017). In addition, providing structure for initial interactions between learners, such as through the use of conversation scaffolds (Xethakis, 2023), can help to reduce uncertainty in these situations.

The categories expressing opinions, standing out, and being left out correspond to the situational factor becoming the center of attention. Individuals who experience anxiety in social situations are often concerned about sounding inarticulate or unintelligent, boring others, not knowing how to respond, and being ignored (Mattick and Clarke, 1998). Actions that draw others’ attention to oneself, such as expressing a differing opinion or one that is not as good as another’s, speaking out in a group, or even having to answer a question, involve such concerns and raise the motivation to make the desired impression on others, thereby creating the potential for anxiety. While it may be difficult to completely remove some sense of anxiousness when the attention of the other members of the group is on them, building a sense of psychological safety between learners (Kȩbłowska, 2012) is important to counteract this, as learners often will not share ideas and opinions until they feel sure that the teacher or their peers won’t reject them (King and Smith, 2017). Creating an atmosphere where learners feel comfortable to share can help to ease the impact of these situational triggers. One means of doing this is a pyramid discussion (Jordan, 1990), where learners first work with a single partner, then this pair combines with another pair to form a group of four, and so, slowly building larger groups to encourage interaction and reduce the consequences of speaking by slowly acclimatizing learners to interacting with larger groups.

Uncertainty, ambiguity and novelty are situational factors of interaction anxiety that pertain to the categories of uncomfortable silence and being uncertain. Situations where an awkward silence comes about, or learners run out things to say inevitably bring with them a sense of unease about what to do next, as do predicaments learners may face over turn-taking, such as when to add something to a conversation or when to ask a question, all of which can act to decrease one’s sense of impression efficacy. The impact on one’s sense of efficacy is all the greater when there is lack of response or active participation from other learners. The presence of these categories again underlines the importance of providing structure for learner interactions to reduce uncertainty and encourage interaction, as for example by providing them with practice using language needed for discussions (Fushino, 2010b) or using conversation strategies (Barrington, 2021).

In regard to the communication related categories coming out of the analysis, the most frequently mentioned were competence and proficiency, conveying meaning and understanding others. Surprisingly, situations where learners felt negatively evaluated by others or made mistakes in L2 usage were less salient. This is noteworthy because being negatively evaluated and fears over making mistakes have been pointed out in previous studies as prominent factors underlying learner anxiety (e.g., King, 2014; Horwitz et al., 1986, Williams and Andrade, 2008). One possible reason for this divergence is the context of the study. It may be the case that when learners work in small groups, worries over evaluation, being monitored by the teacher, or making mistakes in front of the whole class diminish, as there may be less risk to their social standing. In turn, because of the more direct contact between group members, there is a shift to concerns over expressing oneself clearly to help build relationships with other group members. While the results of this study cannot directly address this supposition, it does suggest the need for research to further examine differences in the situational triggers of FLA in small groups as opposed to whole class contexts.

This study has provided evidence that FLA and interaction anxiety as they operate in the context of small group work are distinct, and more importantly, that from learners’ perspectives, the situational triggers of each form of anxiety are distinct as well. The recognition of this distinction is important for a number of reasons. First, neglecting the distinction and subsuming all forms of anxiety that occur in the language learning classroom under the umbrella of FLA would not only confound investigation into the nature of anxiety in language learning and the means to limit its impact, but would also negatively affect classroom practice, making it more difficult to differentiate between learners whose anxiety is grounded in FLA and those who are experiencing interaction anxiety. Second, while much is known about the sources of FLA, examination of the causes and impact of forms of social anxiety on language learning has begun only recently (e.g., Miura, 2019; Zhou, 2016). As the underlying sources of these two forms of anxiety differ (i.e., concerns over language use in a social setting versus interacting with others), the means of helping learners cope with each form of anxiety differ as well. In order to do this properly, teachers need to be provided with methods and measures for dealing with both forms of anxiety. This requires a knowledge of the concrete situational triggers behind the experience of anxiety as it manifests when working in small groups, which in turn necessitates further research into the nature of interaction anxiety in the classroom, as well as into the efficacy of pedagogical interventions aimed at reducing learners’ unease when working in small groups. As shown by the work of King et al. (2020) and Yashima et al. (2016b) such interventions may also help to improve classroom atmosphere and learner engagement in communicative tasks. Paying attention to the emotional states of our learners can make our teaching more effective (Arnold, 2011), and this is even more the case when looking to limit the impact of negative emotions such as the many forms of anxiety.

Furthermore, and possibly more importantly, the possibility exists that social anxiety and interaction anxiety are more fundamental forms of classroom anxiety than FLA. As outlined above, King et al. (2020) were able to improve the social atmosphere of the classroom and as a result learners interacted more freely, but did not increase their amount of L2 use. Conversely, Yashima et al. (2016b) created conditions encouraging L2 use but found that other forms of anxiety limited speaking among some learners who felt they were proficient enough to take part in a discussion. The two studies, together with the prominence of interaction related situational triggers found in this study, suggest the need to engage with and reduce learners’ feelings of social anxiety prior to grappling with their sense of FLA. This possibility underscores the need for more research on the impact of interaction anxiety in the language learning classroom.

5 Limitations and future directions

One concern with qualitative analysis is the subjectivity and biases of the researcher (Morse, 2015). The primary findings of this study came from the analysis of short responses, limiting contextual information in the data, and opening the analysis process to the subjective interpretation of the authors. However, it was felt that the use of QCA, a transparent, systematic, and rule-based method of qualitative analysis, together with the inclusion of a quantitative measure of communication apprehension and the combined analysis of the qualitative and quantitative results has helped to limit the influence of subjective interpretation, and address issues related to the confirmability, credibility and trustworthiness of the study (Guba and Lincoln, 1989). Another concern with qualitative analysis is whether the phenomenon under investigation has been fully described (Morse, 2015). While it may seem that the brevity of the responses limits the thickness and richness of the description, the large sample size serves to offset this concern (Morse, 2015), while also addressing issues of credibility. A second sample was also included in the study as one means of addressing this issue, as well as that of dependability (Morse, 2015). Nonetheless, future research into the nature of anxiety in group work should take a more in-depth approach using interview or focus group techniques to characterize learners’ experience of anxiety and verify the descriptions of the situational triggers from this study. In addition, research examining learners’ physiological reactions when engaging in group work could provide valuable, and perhaps, differing perspective on the manifestation of this emotion. The use of such various techniques could help to overcome the limitations of self-report methods, e.g., the effects of social desirability and cultural norms on response patterns, and possible limited awareness of the characteristic being measured on the part of respondents (Heppner et al., 2008), the primary method of data-collection employed in this study. Finally, the degree to which the qualitative and quantitative results could be combined was limited by the lack of a measure of FLA. While not the primary focus of the study, the surprising findings in regard to the situational triggers of FLA uncovered in this study suggest the need to more fully investigate the nature of FLA as it manifests in small group work.

This paper has suggested several interventions to help reduce learners experience of anxiety when working in small groups. Future studies on interaction anxiety and FLA could investigate the efficacy of interventions such as those mentioned above in reducing the negative impact of anxiety. In order for this research to be carried out, it may be necessary to develop instruments to more accurately measure learners’ emotions in small group work, as the most commonly-used measures of FLA, social anxiety, and interaction anxiety are not specific to the small group context—a context in which emotions can function differently, as both the findings of Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. (2011) and of this study indicate.

6 Conclusion

This study provides a novel perspective on the phenomenon of anxiety in the language classroom by exploring sources of this negative emotion in small group work. Employing a mixed-methods research design to investigate learners’ perspectives on situational triggers of anxiety in small group work, it extends research begun by King (2013, 2014) to examine the impact of social anxiety on language learning and aims to contribute to the literature by broadening the conception of anxiety and its influence in the language classroom and in small group work. The results of the study strongly suggest that FLA and interaction anxiety are distinct constructs in the context of small group work and clearly indicate that interaction related situational triggers of anxiety play an important role when learners work in small groups. Qualitative analysis found that these triggers were of significantly greater importance for learners than language related ones, while analysis of learners’ scores on a measure of communication apprehension in group work revealed that one-third of learners reported considerable unease when interacting in small groups. This triangulation of results indicates that social anxiety, in the form of interaction anxiety, may be a more important, and possibly more fundamental, concern than FLA for many learners working in small groups in the language classroom. The results of this study will hopefully not only enrich the existing literature on anxiety in language learning, but also suggest new directions of research such as further elaborating the nature of interaction anxiety through more in-depth analysis of learners’ experience and investigating means of reducing the impact of social anxiety in language learning.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Tokai University Ethical Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LX: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Supervision. MR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists, Grant Number JP22K13172.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all of the teachers who assisted in collecting data for this study, and of course, the learners who took the time to respond to the survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1461747/full#supplementary-material

References

Aida, Y. (1994). Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: The case of students of Japanese. Modern Lang. J. 78, 155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02026.x

Archbell, K. A., and Coplan, R. J. (2022). Too anxious to talk: Social anxiety, academic communication, and students’ experiences in higher education. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 30, 273–286. doi: 10.1177/10634266211060079

Arnold, J., and Brown, H. D. (1999). “A map of the terrain,” in Affect in language learning, ed. J. Arnold (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–24.

Barrington, R. (2021). Including conversation strategies in an English communication course. SILC J. 1, 65–69.

Bekleyen, N. (2009). Helping teachers become better English students: Causes, effects, and coping strategies for foreign language listening anxiety. System 37, 664–675. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2009.09.010

Botes, E., Dewaele, J. M., and Greiff, S. (2020). The foreign language classroom anxiety scale and academic achievement: An overview of the prevailing literature and a meta-analysis. J. Psychol. Lang. Learn. 2, 26–56.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cantwell, R. H., and Andrews, B. (2002). Cognitive and psychological factors underlying secondary school students’ feelings towards group work. Educ. Psychol. 22, 75–91. doi: 10.1080/01443410120101260

Catalino, L. I., Furr, R. M., and Bellis, F. A. (2012). A multilevel analysis of the self-presentation theory of social anxiety: Contextualized, dispositional, and interactive perspectives. J. Res. Pers. 46, 361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.02.006

Cheng, Y. S., Horwitz, E. K., and Schallert, D. L. (1999). Language writing anxiety: Differentiating writing and speaking components. Lang. Learn. 49, 417–446. doi: 10.1111/0023-8333.00095

Clark, D. M., and Wells, A. (1995). “A cognitive model of social phobia,” in Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment, eds R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, and F. R. Schneier (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 69–93.