- 1Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families Over the Life Course, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Brain and Mind Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Uniting NSW.ACT, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 5Science of Learning Research Centre, Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Background: There is scant research examining evidence-based processes and practices that delineate how to include the voices of children in service design and delivery in school age care environments such as Outside of School Hours Care (OSHC). A possible structure to support children to share leadership in design of their OSHC program and have a meaningful voice in decision-making is co-production, whereby children and their OSHC communities have the opportunity to co-plan, co-design, co-deliver, and co-evaluate OSHC program activities. The Connect Promote and Protect Program (CP3), a social connection and wellbeing program that provides a structured method of co-producing with children, educators, and their OSHC communities, is examined.

Objectives: This study aimed to explore the response to a co-production approach in OSHC settings as part of participation in the CP3.

Methods: Qualitative interviews and focus groups were conducted with 12 OSHC staff (educators, coordinators, managers, and volunteers) and 12 children attending OSHC as part of a wider mixed-methods implementation-effectiveness stepped-wedge trial of CP3 in 12 OSHC services located in urban and regional areas of New South Wales, Australia. Participants undertook semi-structured interviews/focus groups via multiple communication platforms (face-to-face, phone, and video-conferencing platforms). A representative research team (including researchers, OSHC educators/coordinators, OSHC administrators, clinicians, and parents of children in OSHC) used an inductive thematic analysis process. Two researchers undertook iterative coding using NVivo12 software, with themes developed and refined in ongoing team discussion.

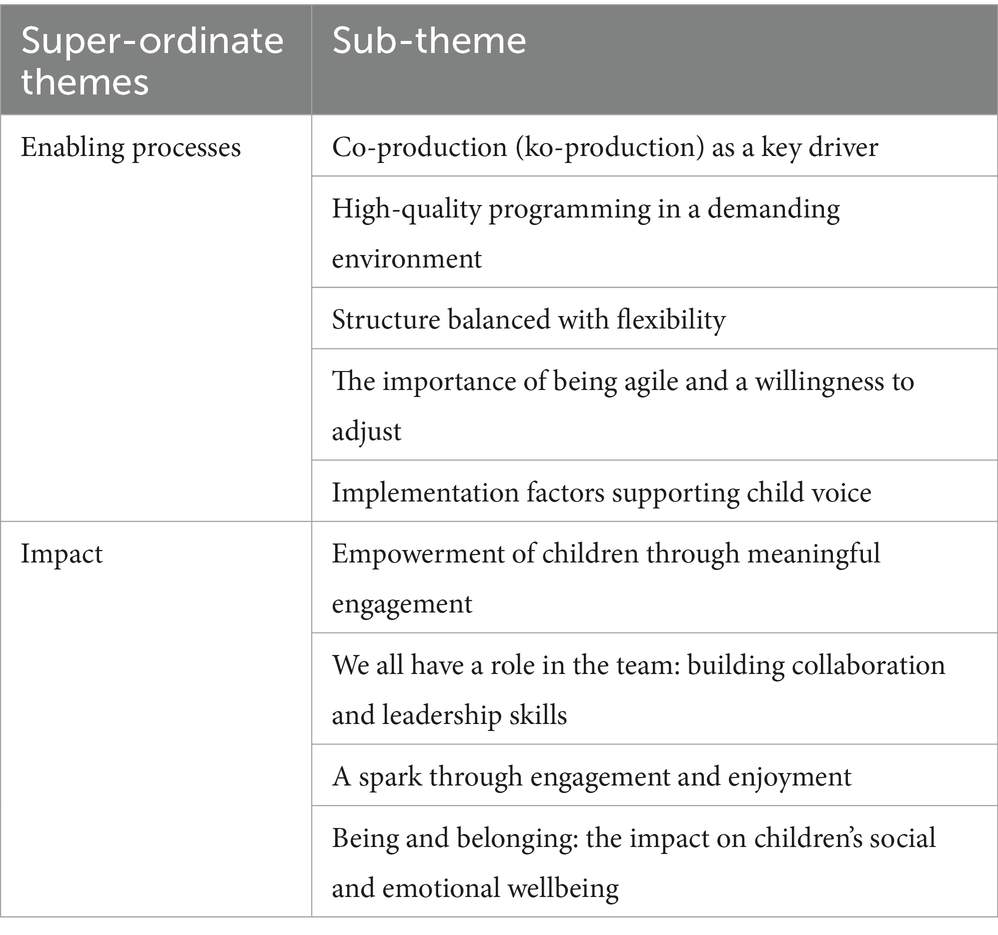

Results: The analysis identified nine sub-themes that related to child co-production and voice in CP3, which were organised into two super-ordinate themes: (1) processes that enable child agency and voice and (2) the impact of child agency and voice. Process related sub-themes included the following: co-production (ko-production) as a key driver; high-quality programming practice in a demanding environment; structure balanced with flexibility; the importance of being agile and having a willingness to adjust; and implementation factors supporting child voice. The impact related sub-themes included the following: empowerment of children through meaningful engagement; we all have a role in the team (a space for growing leadership skills); a spark through engagement and enjoyment; and being and belonging (the impact on children’s social and emotional wellbeing).

Conclusion: This is the first known qualitative study to examine the use and impact of co-production processes in OSHC—where children not only co-design but also co-plan, co-deliver, and co-evaluate the activity programming alongside OSHC educators and their communities. The findings indicate that the co-production process provides a structured, yet flexible, way of supporting children’s voice and leadership even when delivered in diverse types of OSHC settings.

Background

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989) advocates for the fundamental rights of children to be consulted and to express their views on matters that affect them. This emphasis on child-centred practice, which enables children’s voice and agency (Australian Government Department of Education, 2022), is echoed in Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority’s (ACECQA) National Quality Framework and National Quality Standard (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, 2018), which regulates Australia’s School Aged Care (SAC) system. Despite this, there is scant research looking at formal evidence-based processes and practices that include the voices of children in service delivery in school age care, such as Outside of School Hours Care (OSHC).

OSHC can often be referred to as out of school hours (OOSH) services, after school care, or before and after school care. SAC such as OSHC services offer a secure and supervised environment for primary school aged children, who are typically aged 4–12 years. Care is provided before and after school typically for 2–3 h a day during the school term, and some services offer vacation care in school holidays (Milton et al., 2023). In 2020, Australia’s Productivity Commission reported 5,000 OSHCs supporting 460,000 Australian children, and it is now the fastest growing childhood education and care sector in Australia (Cartmel and Hurst, 2021). Despite this, staff turnover is high (Cartmel and Hayes, 2016) which may be attributed to low pay, insecure working conditions, and limited career/training advancements (Simoncini and Lasen, 2012). Further, educators are not required to hold qualifications or formal training in child development, wellbeing, or mental health in Australia (Murray et al., 2024).

Although the field is growing, there is limited qualitative literature from SAC and OSHC settings, and still fewer examples of studies providing children’s voices (Cartmel and Hayes, 2016; Simoncini et al., 2015). Research suggests listening to children’s needs and perspectives delivers responsive policies and practices and improved child experiences (Flückiger et al., 2018; Moir and Brunker, 2021). The global literature suggests that when asked children in SAC settings say they value play, freedom, choice in activities, being with friends, having private spaces and the availability of supportive non-intrusive adults (Simoncini et al., 2015; Horgan et al., 2018; Lehto and Eskelinen, 2020; Elvstrand and Närvänen, 2016) and want to be treated appropriately for their age (Horgan et al., 2018; Hurst, 2017). Furthermore, over-structuring and too many rules decided on by adults is often viewed negatively by children (Horgan et al., 2018; Elvstrand and Närvänen, 2016). This feedback from children highlights a clear need for meaningful participation in SAC and that the voices of children need to be listened to and incorporated into programming decisions.

There remains scant information in the academic literature outlining how to listen and respond to children’s voices in SAC settings such as OSHC for program planning, program design, program delivery, and program evaluation purposes. Indeed, understanding how to apply the voices of children in programming once they have been articulated and understanding the impact of this process on children and their SAC services would be a clear benefit to the field. A significant Australian Report on OSHC, “More than convenient care,” emphasised the need for cross-collaborative initiatives in partnership with children in design of OSHC programs. At the same time, research is increasingly seeking to adopt a participatory methodology, typically known as co-design, to enable children to actively contribute to intervention development and decisions that relate to them (Milton et al., 2023; Milton et al., 2021).

Co-design and co-production

Co-design, also known as participatory design, places stakeholders at the centre of the design process (Sjöberg and Timpka, 1998; Ospina-Pinillos et al., 2018) and involves a process of collective creativity applied across the entire design process (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). Co-design represents a paradigm shift in practice from top-down design towards collaborative bottom-up engagement, whereby stakeholders jointly explore and create solutions to program design and service delivery (Milton et al., 2021). Co-design involves more than participants simply voicing what they want from interventions or services or are engaged in jointly exploring and articulating needs and collaboratively exploring and creating solutions (Sanders, 2002). Emerging research in other settings such as mental health also extends participatory processes to co-production (Milton et al., 2024; Kealy et al., 2024). Co-production includes end-users having a role in co-planning, co-design, co-delivery, and co-evaluation of interventions. In OSHC settings, this means that children themselves, not just the service administrators and educators, are key contributors and drivers of these participatory processes. Noting through our program, the Connect Promote and Protect Program (CP3), this has been coined ‘ko-production’ for kids in co-production.

The connect promote and protect program

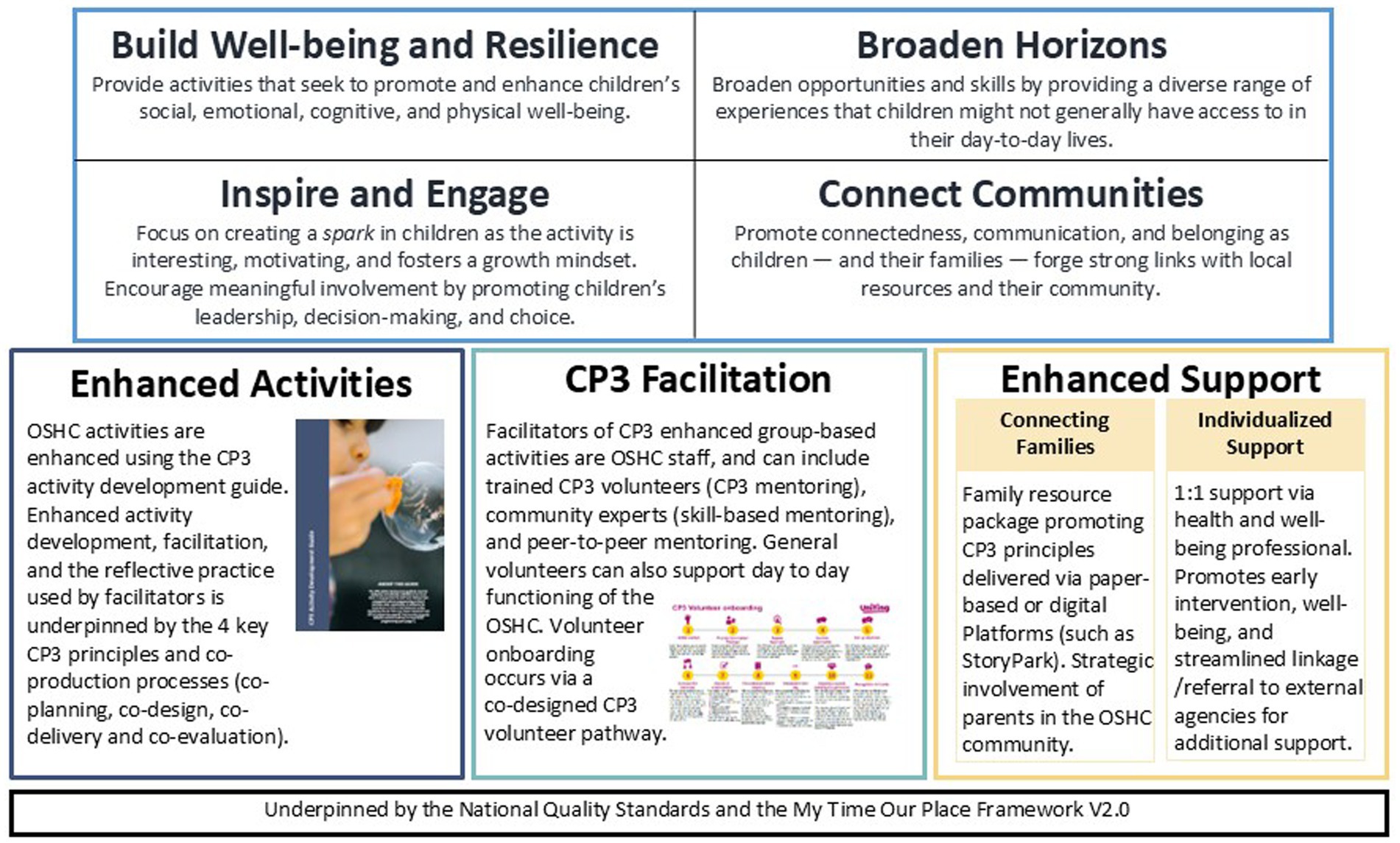

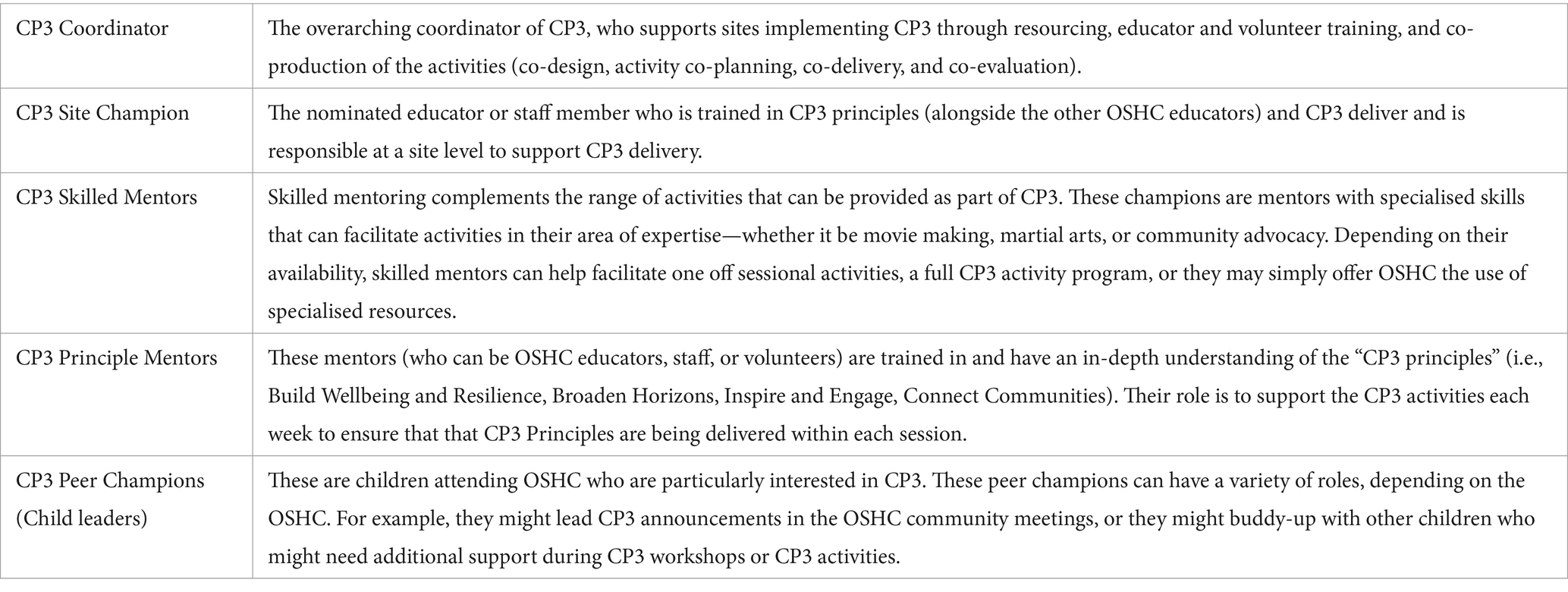

In Australia, CP3 is the first and only known co-designed evidence-based social connection and wellbeing-focussed program delivered in OSHC (Milton et al., 2021). CP3 provides a structured method of co-producing with children, educators, and their OSHC communities utilising unique activities through co-planning, co-design, co-delivery, and co-evaluation processes. CP3 activities are unique and tailored to each participating OSHC but have the same overarching aim of providing opportunities for social connection, child leadership, and engagement, through the delivery of activities that broaden children’s experiences, opportunities, and wellbeing. As shown in the CP3 Model (Figure 1) and discussed in past formative co-design (Milton et al., 2021) and evaluative research (Milton et al., 2023), CP3 has four guiding programming principles (CP3 Principles): (1) Build Wellbeing and Resilience; (2) Broaden Horizons; (3) Inspire and Engage; and (4) Connect Communities. As defined in a study by Milton et al. (2023), there are multiple CP3 personnel who are trained and support the implementation of CP3 in OSHC settings (Table 1); importantly, one of these roles—‘CP3 peer champions’—includes children at OSHC having an opportunity to engage in leadership roles as part of the program delivery.

In line with documented co-design practices with children (Thabrew et al., 2018), in CP3, there are creative techniques to engage children. The manualised program follows a structured engagement process (Stage 1: consult and create; Stage 2: test and refine; Stage 3: implement and evaluate; see Milton et al., 2023). This includes initial co-design workshops that use visual materials, storytelling, fun and playful activities, and the physical creation of ideas with the use of whiteboards, butchers paper, storyboards, inspiration cards, stickering activities, and modelling tools such as Play-Doh and Lego. Children prototype various activities and co-plan their delivery. After this, the children try these activities through a “taste test,” so they can co-evaluate to improve or extend the activities before they are rolled out into the full CP3 activity delivered at their OSHC. As highlighted above, children are able to co-deliver these activities through their CP3 peer champion roles.

Outside of utilising a co-production model (Milton et al., 2024; Kealy et al., 2024), CP3 draws on Hart’s ‘ladder of participation’ (Hart, 2013), with a focus on ensuring genuine participation of children which ranges from ‘adult-initiated, shared decisions with children’ to ‘child-initiated, shared decisions with adults’ as the CP3 delivery progresses over time. In line with Ludy’s seminal study (Lundy, 2007), meaningful child participation in CP3 ensures that there is sufficient ‘Space’ provided to children so they can express their views in a child-friendly way; their ‘Voice’ is facilitated in various forms, and children are provided multiple opportunities to participate in decision-making, and children’s ideas are taken seriously (i.e., have ‘Influence’) as those that have the power (i.e., the ‘Audience’) such as the SAC service coordinators and educators listen and act upon the ideas generated by children accordingly.

The current study

As part of a large, mixed-methods, randomised stepped-wedge trial of CP3 in 12 Australian OSHC sites, qualitative implementation-effectiveness data from adults engaged in program delivery and children who participated in CP3 were collected. This was a sub-study from this larger trial in which main objectives were to explore how co-production facilitated and impacted children’s leadership, voice, and decision-making as part of the Connect, Promote and Protect Program (CP3) in Outside of School Hours Care Services (OSHC).

Methods

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol Number: 2022/254).

Study design

This qualitative sub-study is part of a larger stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial evaluating CP3’s implementation and effectiveness. The CP3 model was developed with local stakeholders in 2017 using participatory co-design (Milton et al., 2021) and has been refined further in a formative and process evaluation (Milton et al., 2023). The overarching CP3 research is based on the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for developing complex interventions (Skivington et al., 2021) which uses an iterative research design cycle of ongoing development, feasibility, evaluation, and implementation. A critical realist orientation was applied to the research (Archer et al., 2013). We made use of the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ checklist, Tong et al., 2007; Supplementary File 1).

Participants and setting

Participants comprised two stakeholder groups: (1) children attending OSHC aged between 4 and 12 years and (2) OSHC educators, coordinators, managers, or volunteers. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) identified as one of the stakeholder groups; (ii) able to participate in English; and (iii) provide written informed consent to participate. For a child to participate in the research, both parental/guardian and child written consent were obtained. Participants were recruited from 12 OSHC services in urban and regional areas of New South Wales, Australia. A priori sample size estimate was guided by research (Hagaman and Wutich, 2017; Hennink and Kaiser, 2022; Milton et al., 2022), suggesting 20–40 participants would be required for data saturation as the research involved recruiting a non-homogenous participants (i.e., both children and OSHC personnel). Data were collected after the CP3 had been delivered at these sites.

Recruitment and procedures

Electronic and paper-based advertising materials were used to notify potential participants (and children’s parents or guardians) of the study. Recruitment was passive so that participants (or their parents/guardians) initially volunteered by signing up on a contact form or contacting researchers directly to participate. Upon receipt of parental consent, children went through a consent and a subsequent assent process immediately before the activity. All participants were reassured of the voluntary nature of participation and that they could stop at any time. Participants did not receive any compensation or reward for taking part.

Data collection and analysis

A qualitative semi-structured interview/focus group guides was developed by the evaluation research team who had diverse stakeholder backgrounds, including academic researchers, OSHC personnel, parents of children in OSHC, and child health and mental health clinicians. This diversity in background of qualitative research team is now encouraged as best-practice in qualitative research (Milton et al., 2024; Milton et al., 2022; Klinner et al., 2023; Powell et al., 2024). Input from children was gathered on the child-focussed questions to ensure clarity before they were used. The semi-structured interview and focus group guides can be found in Supplementary File 2. After informed consent, audio-recorded interviews and focus groups were conducted face to face at the OSHC, or via telephone or a digital communications platform between October 2023 and May 2024. Interviews were conducted by either a research psychologist with extensive experience in OSHC services and child mental health (AM) or a paediatric nurse (YH and HN). The OSHC provided photo prompts of activities to support the discussion with children. The average interview duration was 38 min for adults and 25 min for children’s focus groups. A one page lay summary of the findings was returned to participants.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed, anonymised, and checked for accuracy. Qualitative data were analysed using a six-step qualitative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021): (1) data familiarisation; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes and sub-themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) refining, defining, and naming themes; and (6) report writing. This step-wise process provides a flexible and accessible way of analysing qualitative data and enables iterative exploration of patterns and relationships between different themes whilst ensuring research rigour. Qualitative data from the focus groups and interviews were reviewed by three members of the researcher team (AM, HN, and KB) noting relevant points and key concepts across all participants to develop an initial coding framework and checked by a fourth (a manager of OSHC services) to triangulate interpretation. Notes were then coded in NVivo (version 12) software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2016) by one researchers per transcript (AM or HN) and reviewed by the wider qualitative team. The coding followed an iterative process of reading, coding, and discussing the pattern and content of coded data.

Results

Participation

In total, 12 adults participated in qualitative interviews comprising 3 OSHC educators, 8 OSHC coordinators, and 1 volunteer. Four focus groups with 12 children in total were conducted.

Main findings

As presented in Table 2, nine key sub-themes were identified in the data that related to child leadership and voice in CP3, which we organised into two key super-ordinate themes: (1) process considerations that enable child agency and voice and (2) the impact of child agency and voice being enabled in OSHC.

Structured processes enabling child agency and voice

Co-production (ko-production) as a key driver

The process of co-production, and specifically kids in co-production (ko-production), was identified by participants as an important driver of child agency and voice. Personnel in OSHC services identified that they often lacked the confidence and processes to capture the voices and interest of children in creative and meaningful ways—they reflected that the inclusion of formal co-design workshops as part of CP3 delivery was a key avenue for addressing this need and building their skill set. Specifically, as child-centred co-design workshop and ongoing co-planning and co-evaluation processes were embedded from the outset of the program through a structured engagement process (Stage 1: consult and create; Stage 2: test and refine; Stage 3: implement and evaluate), the sites were better equipped to allow a welcoming space for children’s voices to be encouraged and heard, that is, the program provided them with this clear pathway for children to contribute ideas. From the program outset, children were empowered to design and choose the activities that promoted the CP3 key principles through co-design. They were engaged in co-planning how they would run the activities at their service. Children in different focus groups noted that this process of co-design was easier and better way of choosing activities:

“It’s like a bit more easier rather than just asking all children to put their hands up.” (Children’s Focus Group, OSHC 3)

Further to this, there was a child-led co-delivery component of the program that was also evident throughout the interviews. Multiple participants reflected that older children were given leadership roles in delivering the program, helping younger ones, and taking on responsibilities. This was seen as important as the opportunity to mix age groups is not typical in schooling environments. Finally, being a part of the co-evaluation of the activities, including identifying what worked and what should change, meant that the program was run on the children’s terms.

“Yeah, well, I think it kind of showed the kids that they are in control, you know, this our service does not work without having kids. And their voices are everything to us, we are very child driven at this service. So what they say goes with reason, essentially. So I think for them to be a part of that initial planning process same for the staff. It just made them care about it more, it invested them. They were so much more invested into the whole experience.” (Coordinator, OSHC2)

High-quality programming in a demanding environment

Participants relayed that multiple micro, meso, and macro factors exist that influence their ability to implement high-quality programming in OSHC. These factors can promote or be a barrier to children’s voice and agency being a part of programming. This included individual factors at a micro level including insufficient confidence, knowledge, skills, and time for OSHC personnel to engage with children and in reflective practice. At a meso level, there were issues such as stretched organisational resources, administrative burden, staff churn, and being in small or pack-up pack down service. At a macro level, there were factors such as regionality and government funding. It was noted that having the additional training, funds, data insights, and personnel provided through CP3 helped alleviate some of this burden to facilitate more meaningful engagement of children in programming.

“And plus we are a very small service, so we only have three educators. Um, like now we have four on the floor, but two are casual and then it’s like two permanent staff. So it does limit some things what we can do (…) I think it [CP3] brings an opportunity that it’s hard to replicate by ourselves, in after school care, especially since we are a small service … it does give it’s an instant opportunity for the children to learn something more and have that more personalised attention.” (Educator, OSHC1)

This was a positive cycle that promoted a sense of achievement for children and also the educators. This sense of achievement enhanced positive staff morale and, in turn, boosted the team’s focus on providing holistic engagement and development of the children in the service.

“I think it’s really I think it’s kind of changed the way we look at programming as well. Like I said, we used to program small things and ever since the CP3 that was kind of a long project. And I think that’s what we are getting more involved now because we have noticed the children are more interested in longer projects to get that like end result.” (Coordinator, OSHC7)

Structure balanced with flexibility

CP3 was seen as balancing the need for structure with a need for flexibility based on the individual service’s situation. This was seen as critical to service and program delivery as OSHC sites were not homogenous, noting the above-mentioned micro, meso, and macro factors that influenced service delivery and the fact that educators and children from different services (and within services) have different needs, wants, ideas, skills, and motivations. Despite this wide service variation, the structured bottom-up approach to CP3 (enabled through activity co-production with children and personnel at each site) was sufficiently flexible to enable child-centred engagement, voice in decision-making, and equal contributions on a joint collaborative activity that they were interested in.

“It can be tricky to find activities that all kids collaborate in, which is obviously our goal because we do not want to have, you know, five different activities on an afternoon for the different kids to have. I want them all to know that they are all equal and can collaborate as one.” (Coordinator, OSHC2)

“There was those couple of kids who were not super interested in it. Some activities had more kids interested than others. Yeah, it’s really dependent on the interests of the children.” (Coordinator, OSHC5)

In one service, some children did not initially wish to participate in CP3 preferring other activities, and an educator explained how they continued to enable choice which fostered a sense of ownership, which in turn increased participation.

“Okay, this program is for you guys. You can come and join. Just have a look if you are interested… Yeah, like if they do not want to participate, we cannot force them. ‘Okay. You can go and do other activities’. So yeah, but we find out they like it now so at the end [of CP3 activities] all children were over there. No one was outside.” (Educator, OSHC 3)

This was surprising for the educator as such high participation was unusual in general OSHC settings:

“I’m in this industry [SAC service provider] – I can say I think more than five years. But not a single program, like hundred percent children over there. At least you have 1 or 2 children they do not want to do that. But yeah, 98, 95%. Yes. But two or three, definitely they do not want to. But we were surprised at the end, all children over there, we want to join this one.” (Educator, OSHC 3)

The program structure enabled multiple flexible pathways for engagement through avenues of participation that accommodate these differences in preferences and the different ways in which children engage with the world.

“If a child wasn’t interested in planning the calm down area, they were interested once it was done. So it was like I think there was something for everyone. And that’s the same with the chickens [project] as well. There was something in the whole project for everyone. There was kids that absolutely were not interested in the incubation side as soon as they hatched that they hold the chickens every single day. So I just think it’s like it’s just really helped our children as a as a whole.” (Coordinator, OSHC 7)

This flexibility in engagement was seen as very important as children do not all engage in the same way.

“It’s great because you can get a number of different children’s perspectives at a similar time. It’s tricky because half the kids do not want to be sat down for a group discussion. They do not want to have that chat. They want to go and play.”(Coordinator, OSHC 5)

The importance of being agile and the willingness to adjust

Participants reflected the need to be open to the unexpected nature of meaningfully engaging children in decision-making, with a willingness to adapt to children’s interests being paramount. Being responsive to children’s needs when programming meant that the OSHC personnel had to be open to change and diversify their activities. Participants reflected that they genuinely valued this feedback and input from children and reflected that enabling the children’s autonomy to choose and also change direction when required created a supportive and inclusive environment.

“When you see how happy the kids are. And like I said, you know, it’s extended on to something that, we keep doing here. So and that’s how I, well I can speak for the other educators as well, you know, its just seeing how much it’s opened up for them to do different things.” (Coordinator, OSHC 10)

Many services commented that extended on their CP3 activities after the program had ended in responsiveness to the high level of engagement from children.

Implementation factors supporting child voice

Participants highlighted key implementation considerations that are essential for OSHC services to effectively engage children in the co-production process of building their own local wellbeing programs using CP3 Principles, as well as delivering the program. These implementation factors centred around the need for ongoing staff training, sufficient time and resources, and clear communication.

Regarding training, service co-coordinators consistently emphasised that finding time for staff training is a challenge in OSHC, but when time was allocated for CP3, it proved to be highly beneficial.

“It’s difficult to sit them (educators) down and do a whole training course with them. So, it was really good that, [Name, CP3 Coordinator] can sit with them for two hours and they actually leave understanding CP3.” (Coordinator, OSHC 5)

Due to time constraints, coordinators and staff preferred shorter, face-to-face training sessions followed by ongoing support through regular updates, meetings, and catch-up calls. Face-to-face sessions with a facilitator enabling staff to ask questions tailor CP3 to their specific service needs and helped them to feel more prepared and connected to the program’s goals. In the future, staff recommended that short refresher top-up training modules on CP3 components, including theoretical insights, processes, principles, and interactive content such as videos, would be beneficial, which could be delivered digitally. This may also be useful for staff who needed “a refresher on how to do it” and for new staff who lacked knowledge of CP3, considering the high turnover typical in OSHC settings.

“But I think we have been through it [CP3] a few times. I think we know the process and how it’s going to happen. Yeah. So I think maybe for the new educators, some sort of training online will be good. So they have an insight into it.” (Coordinator, OSHC 10)

However, this would need human involvement, navigation, and support:

“I think having an online module would be great as long as there’s someone somewhere that you can ask questions to and have a person answer.” (Coordinator, OSHC 5)

One site identified that continuous communication and engagement with the broader OSHC team, including casual staff, was seen as vital and would generate greater program impact.

“If we are not really, involved, involved, it’s kind of easy to kind of forget and not really understand the program as well as we could”. (Educator, OSHC 1)

The additional support of a CP3 coordinator onsite and a budget provided through the program was highly valued, but without this resourcing CP3 may not have been easily implemented and child engagement may have been lower.

“It was [Name, CP3 coordinator] physically coming here, meeting the kids, the kids getting to meet with her and interact with her. …CP3 pretty much just came here, which was really good, and I think that was a huge part of it.” (Coordinator, OSHC 7)

Impact of agency and voice on children

At each OSHC site, there were several impacts relayed by participants that stemmed from enabling children’s agency and voice through the embedded CP3 activity co-production process. This included greater sense of empowerment, leadership skills, engagement and enjoyment in the activities, and enhanced social and emotional skills and wellbeing.

Empowerment of children through meaningful engagement

Enabling children’s voice in decision-making and autonomy over program design was viewed as enhancing their sense of empowerment. As one participant noted:

“It made them feel empowered. It was empowering that they get to choose what to do. They get to choose what they want to do at the [OSHC] centre… participate in those activities. Make them feel empowered and giving them the right or the power for them to be able to choose their own activities and path or programs that they wanted to do.” (Coordinator, OSHC 2)

Children reflected that this process was straight forward and was highly rewarding to see their ideas actioned via the activities.

“It’s easier for us to, like, pick and choose which one we want to do. And get to do what we wanted to do.” (Child Focus Group, OSHC 6)

These feelings of ownership generated within children fostered a more positive experience for them at OSHC.

“I think the program itself, um, encourages the children to kind of be in charge of their own experience. I think offering them, having the collaboration with them of building the program is great. I think it gives them a sense of ownership over the experience that they have and in turn will turn into a more positive experience for them.” (Coordinator, OSHC 5)

We all have a role in the team: a space for growing leadership skills

CP3 was seen as providing a supportive structure and space for all children to take responsibility for planning, designing, and delivering a program and building skills to do this through the co-production approach. OSHC personnel also reported that the co-delivery element developed children’s leadership skills and sense of responsibility. This was particularly the case for the older children that supported and guided younger children to engage in the activities through buddy systems and other leadership roles.

“It definitely promoted leadership roles for older kids as well… it was definitely promoted more leadership responsibility roles for our older kids to help with the younger kids and everything like that. So that was really nice to see.” (Coordinator, OSHC 2).

This was seen to benefit both age groups, especially as this multi-age connection and mentoring is not always enabled in school environments, and mixing of age groups is a unique and important part of how OSHCs are structured.

“I absolutely think it is so beneficial for things to engage with each other in different age groups because they just learn so much. You know, they are developing their language skills and developing their social skills indirectly that help them with their emotional regulate.” (Coordinator, OSHC 2)

It was also noted that certain children taking up leadership roles at OSHC could inspire other children to want to do take on responsibility.

“And I’m sure as a big child if you notice that ‘oh today my friend was leader, why I cannot be?’ So definitely, maybe next time, or maybe next week they say, ‘Oh, I’m doing well so I can be a leader now’. So it’s helps children in their development.” (Educator, OSHC 2)

This leadership opportunity provided through CP3 could also build children’s confidence and help them consider other ways they could lead and engage in OSHC.

“But the more quiet kids that you would not expect to want a leadership role in and they have done that. And then now six weeks later, a completely different child because they have had that sense of achievement and leadership (…) I think those some kids have definitely found their niche and just that little bit more stability at OSHC because, yeah, they have had that confidence of that leadership role before. It’s obviously encouraged them to kind of spread their wings and expand out to do other opportunities at OSHC.” (Coordinator, OSHC 2)

A spark through engagement and enjoyment

It was reported that through children having a voice, they became highly engaged and reported high levels of enjoyment of the activities with terms such as “fun,” “super-duper fun,” “good,” “exciting,” and “very happy” often being relayed. One focus group also highlighted that the activities challenged them in an engaging way, stating it was: “It was fun but equally as hard.” Educators reflected this high level of enthusiasm for the program was evident because CP3 offered something different to regular program delivery and personnel.

“You could tell how happy and excited they were coming in to the experience because it’s something new (…) I feel like when it’s not us running the activity, the kids will engage more. They want to listen and they want to learn about it.” (Coordinator, OSHC 9)

“It’s way different to the activities here because they are not everyday arts and crafts, they are might be a bit of drawing or a bit of paper mâché, but these ones were different.” (Child Focus Group, OSHC 6)

Children also expressed enjoying the activity and wanting to it again both at OSHC and outside of OSHC.

“We tried it, It’s a great opportunity. And next time you are bored, you could just do this activity with a bunch of family and friends. Let us say you are bored in the school holidays or the weekend, and you can do what OSHC taught. Yeah, you can do that.” (Child Focus Group, OSHC 2)

One coordinator reflected that this process of enabling children to have a voice in decision-making positively influenced the way children thought and felt.

“It was them who come up with the idea and they were independent, and they had the choice and they had the say. So it changes the way that they view things as well and how they feel.” (Coordinator, OSHC 7)

A child highlighted that a key to children’s engagement was that the program is not static and can change positively as the activity unfolds and iterates. This meant that the activity design and development could cater to a diverse range of children’s expectations and preferences.

“You might feel excited. Some people will be like, this activity is going to be boring. I know for sure they could be bored. But when the presentations is on and we do like other stuff the person decides to join in because everything is starting to become fun.” (Child Focus Group, OSHC 1)

Although children’s engagement could fluctuate overtime, with novelty compared to usual programming being a key part to fostering excitement.

“And it’s interesting as well because you could have someone be really, really excited about it one day and then the next week they are like nope I do not want to do that. But for the most part, like I said, they were so excited. It’s something new and different from the norm, which is always going to kind of excite them, I think.” (Coordinator, OSHC 5)

Interestingly, because the program co-production process was supported by external personnel and the usual OSHC staff, there was an element of excitement and increased engagement that was felt by the children.

“Because what I’ve learnt being a coordinator is I can say something 100 times and they get sick of hearing my voice and they just kind tune out. Whereas when someone external comes in, and it’s a fresh face and has a completely different perspective on it. They’re more likely to engage.” (Coordinator, OSHC 2)

This was also a factor to increase staff motivation.

“I think as well, having [name, CP3 coordinator] here in person, her being a new face as well, got all the kids very, very excited that something new and exciting was happening. And the educators also got into it as well, just because they I think everyone always responds better to face to face stuff.” (Coordinator, OSHC 4)

OSHC personnel also reflected that having the time and space to build a program alongside children at their service resulted in feeling enthused and inspired themselves.

“But I do think it is a nice and inspiring part of being able to do those programs and have the ability to have those experiences with the kids and allow that for the kids is inspiring. And I think people do get excited about it. Yeah. But again, it all comes back to having the time to then successfully program for it, successfully make it happen.” (Coordinator, OSHC 5)

Being and belonging: the impact on children’s social and emotional wellbeing

OSHC personnel noted that collaboration amongst children flourished during the program, because of the children being so engaged via the co-production process. Interactions during the program were described as enhancing children’s social and emotional skills, where prosocial behaviours, kindness, and teamwork fostered.

“They helped each other, so it was really good to see them communicate in that way. And all the teamwork, you know, involved because of the program.” (Educator, OSHC 1)

“It just brings people together. You might be enemies with somebody else like just not friendships with them. And then you do something together and you are suddenly good friends.” (Child focus group, OSHC 3)

Importantly, this made children feel included and a part of the OSHC community:

“Like included. Yeah, not left out, not like the odd one out. We did not have to do the activities that we did not want to do.” (Child focus group, OSHC 3)

Feeling included made children feel positive. For example, one child in a focus group commented that being included made them feel: “Really good. Yeah, it made us feel happy. Not like, sad because you are like the odd one out and no one wants to play with you.” (Child focus group, OSHC 3). Children feeling included and valued through the program’s engagement processes positively impacted their social and emotional wellbeing. This sense of inclusion and belonging made them feel more comfortable and happy in the OSHC environment.

‘You’ll feel a bit more confident and happy and safe’. (Child Focus Group, OSHC 1)

“I think it just gave them a different sense of like being and belonging and another way to make OSHC home.” (Coordinator, OSHC 7)

It was observed how the program provided alternative ways to be involved in decision-making which also fostered a sense of inclusion, “We have a lot of kids that are here five days a week, and it was just another activity that made them feel more comfortable and gave them a say” (Coordinator, OSHC 7).

Discussion

Principal findings

Research concerning the delivery and impact of co-design programs with children is still in its infancy. Indeed, this is the first known qualitative study where children not only co-design but also co-plan, co-deliver, and co-evaluate the program alongside educators and their OSHC communities. The qualitative accounts of children and staff presented here explore how the co-production process impacts child engagement in OSHC programming. The findings suggest that the co-production process embedded within CP3 provides a structured, yet flexible, way of supporting children’s voice, agency, and opportunity for leadership even when delivered in diverse types of OSHC settings.

Co-design as a flexible solution to supporting children’s voice

Research highlights the importance of listening to children’s voices as part of best-practice service delivery in OSHCs (Cartmel and Hayes, 2016; Simoncini et al., 2015). Echoing calls for child agency, Australian qualitative research has found that children emphasise the importance of choice of the activities they do at OSHC (Moir and Brunker, 2021). Indeed, the governing National Quality Standards (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, 2018) and the My Time Our Place Framework (Australian Government Department of Education, 2022) in Australia emphasise the need for embedding play-base approaches that routinely offer consultation with children. The is prerequisite, however, for developing policies and practices that directly respond to children’s needs and perspectives (Flückiger et al., 2018; Moir and Brunker, 2021). Yet, to date, an evidence-based strategy to support engagement of children across the diversity of OSHC settings has been lacking. The data we provide in this study suggest that the use of co-design may be a powerful method of enabling meaningful child engagement in OSHC program design. Indeed, co-design, as part of a wider co-production process, was seen by participants as providing each OSHC with a supportive and structured approach to engaging children in decision-making, program design, and delivery. In line with other co-design programs with children documented in the academic literature (Wake, 2015), child participation was enabled by centring design and participation and that encouraged active citizenship. This process may enable ‘democratic practices’ which has been seen as valuable to children in the academic literature in SAC settings (Lehto and Eskelinen, 2020).

Importantly, the qualitative findings in this study highlight that there is a positive flow on effect to children when they are enabled to make active decisions about the service where they play, learn, and grow. This impact particularly centred around children sense of empowerment, inclusion, enjoyment and engagement, and leadership in decision-making. Interestingly, these outcomes described by participants that stem from CP3 participation are frequently used to define ‘meaningful participation’: with core elements including children being empowered (Henderson-Dekort et al., 2023), included and listened to, enabled to make decisions about how they can participate, and what is meaningful for them (Willis et al., 2017), whilst having access to participation opportunities (Sinclair, 2004).

Co-production as a pathway to agency, engagement, and leadership

Hart’s ‘ladder of participation’ is a well-established model describing children’s participation in decision-making (Hart, 2013). The bottom three rungs of the ladder (1. manipulation, 2. decoration, 3. tokenism) are viewed as ‘non-participation’, and the top five rungs are all varying degrees of ‘genuine participation’ (4. assigned but informed, 5. consulted and informed, 6. adult-initiated, shared decisions with children, 7. child-initiated and directed, 8. child-initiated, shared decisions with adults). The current program moves back and forth from rungs 6–8 of this model. Although the CP3 is initiated by adults with shared decisions with children (i.e., rung 6), its iterative design process moves towards the child-initiated, shared decisions with adults (i.e., rung 8) as the program progresses. The co-production process extends beyond co-design, as children in the program co-planned activities, co-evaluated their experiences to inform future activities, and importantly co-delivered the program through leadership roles—coined ‘ko-production’ (kids in co-production).

Interestingly, these leadership roles were often filled by older children. This is in line with post-doctoral research with older children in Australian SAC settings, which has found that they want programming strategies that recognise them as older and provide separate roles from younger children (Hurst, 2017). In our study, older children that were asked did value leadership roles, although it is acknowledged that these types of roles may not always be desired by all older children, with literature suggesting some may simply want to play in ways that are separate to their younger peers (Hurst, 2024). Furthermore, some research has reported that children have specific ideas about the roles of staff in SAC and reports not wanting them to be constantly involved in the children’s activities (Ackesjö, 2011) cited in Pálsdóttir, (2019); this process of involvement through co-production that promotes and enables children’s decision-making is a key feature that ensures children’s acceptability of the program (CP3); that is, as the program does not place too much power in the staff hands, but rather places decision in the children’s control, there is a greater sense of satisfaction when participating.

Staff skills and morale

As part of this research, it was emphasised that the wider OSHC community benefited from enabling children’s voice in decision-making through co-production processes. Research highlights that for educators, they themselves having a voice in service delivery is critical in addressing workforce issues that have arisen over recent years (Thorpe et al., 2020; Thorpe et al., in press). Furthermore, the compounding effect of seeing children take on leadership roles, and in turn have positive experiences and develop social and emotional skills through the process, was viewed as boosting staff morale. It is possible that enabling meaningful participation of children through providing time, resources, and reflective practice to OSHC personnel through CP3 may be a key ingredient to boosting staff morale. Such a possibility should be explored further in ongoing research.

Training educators in co-design and co-production approaches to support activity programming, such as those that are used in CP3, may provide an opportunity for professional development. This may be particularly beneficial given that OSHC staff have the highest rate of under-qualification in the Australian care and education sector (Cartmel and Brannelly, 2016). It is acknowledged, however, that services dedicating the time and resources are paramount in supporting such skill development in educators is required. For example, Cartmel and Brannely have found that services can be reluctant to invest in educator professional development—which is a particularly pronounced reluctance for investing in developing short-term workers’ skills (Cartmel et al., 2020). This is despite initiatives such as the Core Knowledge and Competency Framework, which is designed to build the skills and knowledge of the OSHC workforce in Australia having clear benefits—such as a reduction in staff turnover, an increased capacity, and competence of educators (Cartmel and Brannelly, 2016).

Strengths and limitations of the research

The overall sample size of participants was 24 (50% being children), and this is typically viewed in the research literature as sufficient to gain saturation and meaningful insights with non-homogeneous groups (such as children and adults) (Hagaman and Wutich, 2017; Hennink and Kaiser, 2022; Milton et al., 2022). The inclusion of children views is paramount, not only proving triangulation of viewpoints with other stakeholders but also directly aligned with the CP3 co-production approach. Two staff involved in the program delivery resigned from their jobs before being interviewed which may lead to some participation bias, especially noting there were very few negative comments provided by those that were interviewed. We note that this is an 18% attrition rate of staff who were involved in the delivery of CP3, which is lower than expected given the general workforce turnover in Australia amongst early childhood education and care employees each year is estimated to be more than 30% (McDonald et al., 2018). Like most qualitative studies, the interviews relied on participant recollection, where challenges with recall may impact findings. To enhance recall, we used photo prompts of activities to support the discussion with children. We note that we only spoke to children who had parental consent and were available and willing to participate in the qualitative interviews (12/21; 57%). It would be important in the future to consider the voices of children who did not participate in the program directly, so as to understand how they might be included as part of decision-making at OSHC in general.

Criticisms of CP3 were relatively rare, with every participant reflecting that the experience of CP3 was highly positive, and the co-production structure provided a comprehensive way of enabling children voice in programming. This positivity, however, was caveated by implementation factors. Importantly, coordinators felt time poor in their highly demanding day-to-day roles. High demands in SAC are noted elsewhere in the literature, with this being attributed to increased administrative and regulatory burden (Cartmel and Hayes, 2016). Therefore, the additional resources that CP3 provided (including dedicated staffing, time allowances for training, and a supplementary budget) were viewed as vital for ensure program feasibility—which is echoed in past research (Milton et al., 2023). Furthermore, in line with recommendations from a recent systematic review of mental health and wellbeing programs in OSHC, our next steps for CP3 research will be to consider educators’ knowledge of, capability, and confidence to support not only children’s mental health and wellbeing (Murray et al., 2024) but also the processes that enable children’s voice to be heard in programming. This will enable us to further develop the top-up and ongoing training that OSHC educators and services coordinators strongly desired.

Where to next

This type of meaningful engagement through co-production with children and their communities is not well established. Despite increasing acknowledgement that including the active input of children is crucial to conducting insightful and impactful research and interventions, there is currently no best-practice guidance on how to do this. Not only is it recommended that such guidance should be established through participatory consensus processes, programs such as CP3 may help directly inform how these interventions can be co-produced in other areas working with children such as educational and healthcare settings in the future.

Conclusion

This is the first known qualitative study to examine the use and impact of co-production processes in OSHC—where children not only co-design but also co-plan, co-deliver, and co-evaluate the activity programming alongside OSHC educators and their communities. The findings indicate that the co-production process provides a structured, yet flexible, way of supporting children’s voice and agency even when delivered in diverse types of OSHCs settings. OSHC services may wish to draw on these evidence-based process to support them to effectively listen and respond to children’s voices and provide children with opportunities to be leaders in their OSHC. These structured, yet flexible, processes may be critical as providing high-quality OSHC programming is an investment in children’s future given OSHC is the fastest growing childhood education and care sector in Australia (Cartmel and Hurst, 2021).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Qualitative data will be anonymised and provided per ethical requirements and only in written form.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin if under 18, and by all participants.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KB: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TM: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by a Partnership Grant from the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre and Uniting’s Future Horizon’s Award for Social Impact. In addition, Dr. Milton, Professors Thorpe, and Glozier were supported partially by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (Project ID CE200100025). IBH is supported by a NHMRC L3 Investigator Grant (GNT2016346).

Acknowledgments

CP3 is a partnership between the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre (an Australian multi-discipline research institute focussing on conditions that affect child development, youth mental health, and brain ageing) and Uniting (formally Uniting Care NSW.ACT, who are a large provider of children’s services including before and after school care, vacation care, occasional care, long day care, and preschool in New South Wales (NSW) Australia). We acknowledge all the Uniting NSW.ACT Out of School Hours Care Community, including children, families, educators, and volunteers who participated in and supported this research. In particular, we would like to thank especially Madonna Lee, Kim Freckleton, and Amy McPake.

Conflict of interest

IBH is the Co-Director, Health and Policy at the Brain and Mind Centre (BMC) University of Sydney. The BMC operates an early-intervention youth services at Camperdown under contract to headspace. He is the Chief Scientific Advisor to, and a 3.2% equity shareholder in, InnoWell Pty Ltd. which aims to transform mental health services through the use of innovative technologies. CP3 has an executed IP Agreement between the University of Sydney (AM and IH) and Uniting.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1457286/full#supplementary-material

References

Ackesjö, H. (2011). Collaborators and supervisors: the images of children of the roles of recreation personnel. In: AKaB Haglund, editor. Recreation pedagogy: theory and practice in the leisure-time centre. Stockholm: Liber. p. 182–203.

Archer, M., Bhaskar, R., Collier, A., Lawson, T., and Norrie, A. (2013). Critical realism: essential readings. Digital Printing: Routledge.

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. (2018). National quality standards. Australian Government Department of Education.

Australian Government Department of Education. (2022). My Time our Place: Framework for School Age Care in Australia (V2.0). In: Council AGDoEftM, editor. Department of Education.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 8, 3–26.

Cartmel, J., and Brannelly, K. (2016). A framework for developing the knowledge and competencies of the outside school hours services workforce. Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 4, 17–33. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v4i2.25779

Cartmel, J., Brannelly, K., Phillips, A., and Hurst, B. (2020). Professional standards for after school hours care in Australia. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 119:105610. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105610

Cartmel, J., and Hayes, A. (2016). Before and after school: literature review about Australian school age child care. Child. Aust. 41, 201–207. doi: 10.1017/cha.2016.17

Cartmel, J, and Hurst, B. (2021). More than ‘just convenient care’: what the research tells us about equitable access to outside school hours care. New South Wales Department of Education.

Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989). Treaty no. 27531. United Nations Treaty Series, 1577.

Elvstrand, H., and Närvänen, A.-L. (2016). Children’s own perspectives on participation in leisure-time centers in Sweden. Am. J. Educ. Res. 4, 496–503.

Flückiger, B., Dunn, J., and Stinson, M. (2018). What supports and limits learning in the early years? Listening to the voices of 200 children. Aust. J. Educ. 62, 94–107. doi: 10.1177/0004944118779467

Hagaman, A. K., and Wutich, A. (2017). How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on guest, bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods 29, 23–41. doi: 10.1177/1525822X16640447

Hart, R. A. (2013). Children’s participation: the theory and practice of involving young citizens in community development and environmental care. London: Routledge.

Henderson-Dekort, E., van Bakel, H., Smits, V., and Van Regenmortel, T. (2023). “In accordance with age and maturity”: Children’s perspectives, conceptions and insights regarding their capacities and meaningful participation. Action Res. 21, 30–61. doi: 10.1177/14767503221143877

Hennink, M., and Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Horgan, D., O’Riordan, J., Martin, S., and O’Sullivan, J. (2018). Children’s views on school-age care: child’s play or childcare? Child Youth Serv. Rev. 91, 338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.05.035

Hurst, B. (2017). Eat, play, go, repeat: researching with older primary-age children to re-theorise school age care. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne.

Hurst, B. (2024). Programming for older children in school age care: adult and child engagement with developmental pedagogies. Global Stud. Childhood. 14, 140–155. doi: 10.1177/20436106231156467

Kealy, C., Potts, C., Mulvenna, M., O’Neill, S., Donohoe, G., McNulty, J., et al. (2024). Exploring co-production of accessible digital mental health tools in collaboration with young people from marginalised backgrounds: a scoping review. Int. Soc. Res. Internet Interventions 14:e082247. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-082247

Klinner, C., Glozier, N., Yeung, M., Conn, K., and Milton, A. (2023). A qualitative exploration of young people’s mental health needs in rural and regional Australia: engagement, empowerment and integration. BMC Psychiatry 23:745. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05209-6

Lehto, S., and Eskelinen, K. (2020). ‘Playing makes it fun’in out-of-school activities: Children’s organised leisure. Childhood 27, 545–561. doi: 10.1177/0907568220923142

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’is not enough: conceptualising article 12 of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 927–942. doi: 10.1080/01411920701657033

McDonald, P., Thorpe, K., and Irvine, S. (2018). Low pay but still we stay: retention in early childhood education and care. J. Ind. Relat. 60, 647–668. doi: 10.1177/0022185618800351

Milton, A. C., Mengesha, Z., Ballesteros, K., McClean, T., Hartog, S., Bray-Rudkin, L., et al. (2023). Supporting children’s social connection and well-being in school-age care: mixed methods evaluation of the connect, promote, and protect program. JMIR Pediatrics Parenting 6:e44928. doi: 10.2196/44928

Milton, A., Ozols, A. M. I., Cassidy, T., Jordan, D., Brown, E., Arnautovska, U., et al. (2024). Co-production of a flexibly delivered relapse prevention tool to support the self-Management of Long-Term Mental Health Conditions: co-design and user testing study. JMIR Formative Res. 8:e49110. doi: 10.2196/49110

Milton, A., Powell, T., Conn, K., Einboden, R., Buus, N., and Glozier, N. (2022). Experiences of service transitions in Australian early intervention psychosis services: a qualitative study with young people and their supporters. BMC Psychiatry 22:788. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04413-0

Milton, A. C., Stewart, E., Ospina-Pinillos, L., Davenport, T., and Hickie, I. B. (2021). Participatory Design of an Activities-Based Collective Mentoring Program in after-school care settings: connect, promote, and protect program. JMIR Pediatrics Parenting 4:e22822. doi: 10.2196/22822

Moir, P., and Brunker, N. (2021). ‘We actually get to go out and play’: looking through children’s views on out of school hours care to children’s experience of school. Int. J. Play 10, 302–315. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2021.1959226

Murray, S., March, S., Pillay, Y., and Senyard, E.-L. (2024). A systematic literature review of strategies implemented in extended education settings to address Children’s mental health and wellbeing. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 27, 863–877.

Ospina-Pinillos, L., Davenport, T. A., Ricci, C. S., Milton, A. C., Scott, E. M., and Hickie, I. B. (2018). Developing a mental health eClinic to improve access to and quality of mental health care for young people: using participatory design as research methodologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 20:e188. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9716

Pálsdóttir, K. Þ. (2019). Connecting school and leisure-time centre: children as brokers. Listening to Children’s advice about starting school and school age care. (London: Routledge), 99–115.

Powell, T., Glozier, N., Conn, K., Einboden, R., Buus, N., Caldwell, P., et al. (2024). The impact of early intervention psychosis services on hospitalisation experiences: a qualitative study with young people and their carers. BMC Psychiatry 24:350. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05758-4

QSR International Pty Ltd (2016). NVivo for Windows: NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. 11th Edn.

Sanders, E. B.-N. (2002). From user-centered to participatory design approaches. Design and the social sciences. (London: CRC Press), 18–25.

Sanders, E. B.-N., and Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 4, 5–18. doi: 10.1080/15710880701875068

Simoncini, K., Cartmel, J., and Young, A. (2015). Children’s voices in Australian school age care: what do they think about afterschool care? Int. J. Res. Extended Educ. 3, 114–131. doi: 10.3224/ijree.v3i1.19584

Simoncini, K., and Lasen, M. (2012). Support for quality delivery of outside school hours care: a case study. Australas. J. Early Childhood 37, 82–94. doi: 10.1177/183693911203700212

Sinclair, R. (2004). Participation in practice: making it meaningful, effective and sustainable. Child. Soc. 18, 106–118. doi: 10.1002/chi.817

Sjöberg, C., and Timpka, T. (1998). Participatory design of information systems in health care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 5, 177–183. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1998.0050177

Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., et al. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ :374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061

Thabrew, H., Fleming, T., Hetrick, S., and Merry, S. (2018). Co-design of eHealth interventions with children and young people. Front. Psych. 9:366698. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00481

Thorpe, K., Jansen, E., Sullivan, V., Irvine, S., and McDonald, P. (2020). Identifying predictors of retention and professional wellbeing of the early childhood education workforce in a time of change. J. Educ. Chang. 21, 623–647. doi: 10.1007/s10833-020-09382-3

Thorpe, K, Panthi, N, Houen, S, Horwood, M, and Staton, S. (in press). Support to stay and thrive: Mapping challenges faced by Australia’s early years educators to the national workforce strategy 2022-2031. The Australian Educational Researcher. 51, 321–345.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Keywords: participatory design, co-design, co-production, children, after school care, program development, child leadership, decision-making

Citation: Milton AC, Ballesteros K, Hernandez H, Hwang Y, Glozier N, McClean T, LaMonica HM, Thorpe K and Hickie IB (2025) Amplifying children’s leadership roles and voice in decision-making through co-production in outside of school hours care: qualitative findings from the connect promote and protect program. Front. Educ. 9:1457286. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1457286

Edited by:

Jennifer Cartmel, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Karin Lager, University of Gothenburg, SwedenBruce Hurst, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Milton, Ballesteros, Hernandez, Hwang, Glozier, McClean, LaMonica, Thorpe and Hickie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alyssa C. Milton, YWx5c3NhLm1pbHRvbkBzeWRuZXkuZWR1LmF1

†ORCID: Alyssa C. Milton, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4326-0123

Kristin Ballesteros, https://orcid.org/0009-0004-7605-5603

Helen Hernandez, https://orcid.org/0009-0004-8141-0411

Yenni Hwang, https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6731-4133

Nick Glozier, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0476-9146

Tom McClean, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6359-0592

Haley M. LaMonica, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6563-5467

Karen Thorpe, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8927-4064

Ian B. Hickie, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8832-9895

Alyssa C. Milton

Alyssa C. Milton Kristin Ballesteros

Kristin Ballesteros Helen Hernandez1†

Helen Hernandez1† Yenni Hwang

Yenni Hwang Haley M. LaMonica

Haley M. LaMonica Karen Thorpe

Karen Thorpe Ian B. Hickie

Ian B. Hickie