- 1Siemens Ltd., China, Beijing, China

- 2School of Education and Professional Studies, Faculty of Arts, Education and Law, Griffith University, Southport, QLD, Australia

Introduction: Understanding the motivations and challenges experienced by academic expatriates on international branch campuses is critical for enhancing their support and management. By analyzing the motivations and challenges, the study aims to provide more understanding on management strategies of branch campuses to support expatriates in their career development and improve institutional practices.

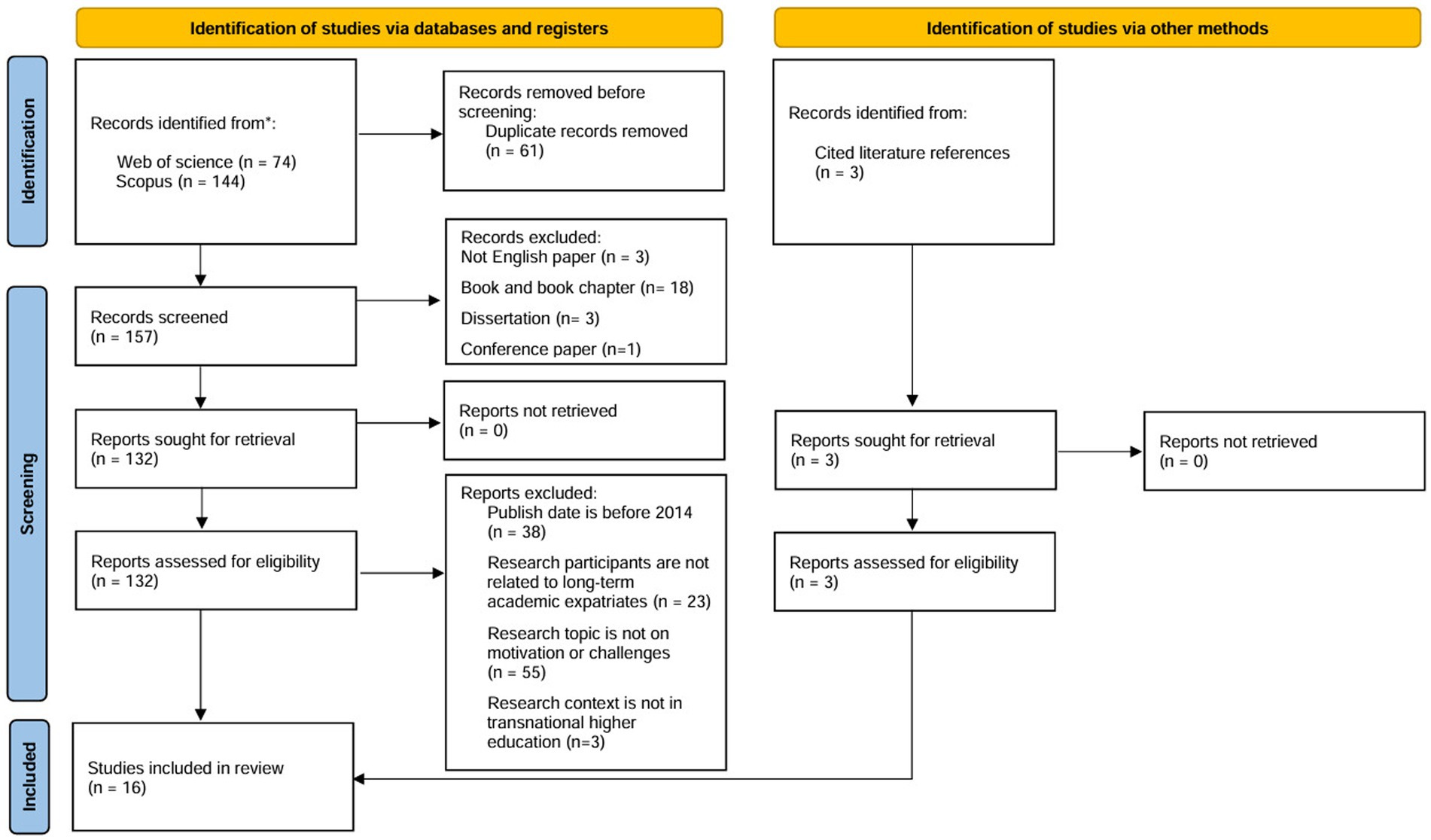

Methods: A systematic literature review was conducted, analyzing 16 studies published from 2014 onwards, using PRISMA guidelines to categorize expatriate motivations and challenges.

Results: Motivations were classified into five types: explorer, refugee, mercenary, architect, and family-oriented. Key challenges identified were rooted in balancing global integration with local responsiveness, concerning professional work, campus interactions, and career development.

Discussion: The findings highlight the need for targeted management strategies to improve the recruitment, integration, and retention of academic expatriates. The study also underscores the importance of longitudinal research to understand the long-term impacts of expatriation on individuals and institutions, contributing to the broader discourse on transnational higher education.

1 Introduction

In the past two decades, there has been a rapid growth in international branch campuses worldwide (Paniagua et al., 2022; Wilkins, 2020). Due to the potential lack of qualified recruits in branch locations, the unique pattern of higher education integration typically involves the international movement of academics from the home campus to other parts of the world (Hickey and Davies, 2022; Healey, 2015). These academics are defined as academic expatriates, referring to individuals in the higher education sector who relocate from their home country to a different nation to undertake long-term, time-bound, and legal employment in teaching or research roles (Trembath, 2016; Przytula, 2023). The international move brings significant challenges both to expatriates themselves and to successful institution management (Neri and Wilkins, 2018). The expatriates may need more institutional support both in work and life to increase their job security during the integration process (Van Niekerk and Mhlanga, 2024).

Attracting and retaining high-quality academic staff is crucial for the successful management of international branch campuses, since high-quality lecture materials cannot be automatically transferred to students (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021). However, staffing issues in international branch campuses present a strategic paradox, requiring the balance of both “global integration” and “local responsiveness” (Shams and Huisman, 2011, p.115; Hickey and Davies, 2022) or the balance between allegiance to the host context and loyalty to the home institution (Dobos, 2011; Al-Tamimi and Abdullateef, 2023). Facing the complex demands to satisfy home and host stakeholders, branch campus management is not yet developed enough to respond to changing circumstances. Current campus management often struggles to meet diverse stakeholder requirements, balance academic integration with local needs, retain talent, and secure sustainable financial support (Hickey and Davies, 2022). Wood and Salt (2017) noted that this expanding higher education integration, akin to multinational enterprises, often lacks a robust leadership infrastructure to respond to contingencies and provide clear human resource support for staff. This exacerbates work conflicts and uncertainties for academic expatriates, thus leading to ambiguous prospects for their career development.

The operation of international branch campuses is a risky decision to both host and home contexts due to significant investments in labor and coordination efforts (Hickey and Davies, 2022). However, relatively few studies have investigated the motivations and challenges facing academic expatriates in the context of international branch campuses, despite these being notable areas worthy of exploration. The existing studies normally focus on a single region or a single institution (Harry et al., 2019; Cai and Hall, 2015; Tahir, 2023; Kurek-Ochmańska and Luczaj, 2021; Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022). The challenges and motivations can differ greatly due to different contexts according to academic, institutional and economic differences (Jepsen et al., 2014; Przytula, 2023). In light of these concerns, this study aims to gather as many studies conducted in as many regions as possible to answer these questions from a broad and critical perspective. This study is guided by the following two research questions:

i. What are the motivations for academic expatriates choosing to develop their careers at international branch campuses?

ii. What challenges do expatriates face when working in international branch schools?

By answering the two questions, the study hopes to contribute knowledge to expatriate management in transnational higher education. It emphasizes the need for comprehensive support and tailored strategies to enhance recruitment, integration, and retention. The study also underscores the importance of future longitudinal research to understand the long-term impacts of expatriation on academic careers and institutional development.

The remainder of this study is divided into two sections. The first section references Richardson and McKenna’s (2002) well-established findings on the four main types of academic expatriates, which are widely accepted for analyzing expatriate motivations (Selmer and Lauring, 2012; Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Despotovic et al., 2022; Al-Tamimi and Abdullateef, 2023). Building on these findings, the study conducts a systematic review of motivations and introduces an additional “family type” to expand upon the existing findings. The second section summarizes the challenges faced by academic expatriates, primarily resulting from the conflicted context of international branch campuses. These findings will hopefully encourage more interest and discussion among researchers on the work experiences of academic expatriates and institutional support required by this group.

2 Method

2.1 Search strategy

The process of article selection followed the Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (Page et al., 2021). The final results can be seen in Figure 1. An initial search on the motivations and challenges faced by academic expatriates working in the context of international branch campuses returned limited results. Considering that the motivations and challenges can vary in different contexts (as stated in the previous section), the scope was extended to include transnational education to capture more findings from various contexts and generalize commonalities that may occur. To remain consistent with the study’s aim, three frequently cited references on the management complexity and organizational challenges in international branch campuses were also manually added to identify the primary causes at the organizational level.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources.

Given these considerations, a broad search was conducted using Web of Science and Scopus data on April 30, 2024. The selection of the two databases is based on their authority and comprehensive coverage in academic research (Pranckutė, 2021). Both databases are widely recognized for indexing high-quality, peer-reviewed journals across various disciplines (Zhu and Liu, 2020). Boolean operators (“OR” and “AND”) were applied to refine the search. To ensure comprehensive coverage of various aspects of “academic expatriates,” “international branch campuses,” and related terms in “transnational education,” a series of reviews were consulted to identify keyword variants for capturing appropriate citations within the searches (Przytula, 2023; Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022; Trembath, 2016). The search focused on full-time academic expatriates holding teaching or research positions at a cross-border level, with the intention to pursue a long-term career in higher education. The search keywords and the search results can be found in Supplementary materials 1, 2, respectively. The final search included 13 studies published from 2014 onwards and 3 studies identified from cited references (Cai and Hall, 2015; Wilkins, 2020). Due to the limited research on academic expatriates in international branch campuses, a reference of 10 years was chosen to ensure a comprehensive review of relevant studies. All search results remain valuable due to their relevance in this field, providing theoretical or practical information for the research on this topic. This broader range aimed to capture key developments and fill gaps in this area.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if their participants were not academic expatriates (e.g., domestic faculty or students) or were short-term expatriates. Additionally, studies were excluded if their topics were too specific and not related to motivations or challenges, or if they did not belong to the transnational higher education context. Articles that were thesis, book chapters, preprints, editorials, and opinion pieces were also excluded from the search. Full-text versions of all selected articles were obtained, reviewed, and confirmed as appropriate.

Considering the limitations on contextual research, as mentioned in the previous section, this study also includes research on staff management issues in the context of international branch campuses as well as systematic reviews on the work lives of academic expatriates in transnational higher education contexts (Escriva-Beltran et al., 2019; Shams and Huisman, 2011; Wood and Salt, 2017). Recent research has also built its analysis on findings of previous work (Duffy, 2024; Dai et al., 2023; Zhan and Marginson, 2023). Therefore, the former criterion enables this study to examine the challenges and motivations from an organizational management perspective, while the latter criterion includes general issues faced by this group.

3 Results: what are the motivations for academic expatriates choosing to develop their careers at international branch campuses?

Many additional factors beyond career choice can motivate academic expatriates to work abroad, such as wage advantage, family happiness, unfavorable environments in the home country, or personal interests and pursuits. Current research tends to follow the assertion of four main types of expatriates, proposed by Richardson and McKenna (2002), when analyzing their motivations to work (Selmer and Lauring, 2010, 2012; Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Lauring et al., 2014; Przytula, 2023; Cai and Hall, 2015). These four types are explorers, who desire to see more of the world; refugees, who are driven by the need to escape unfavorable situations; mercenaries, who are motivated by financial gains; and architects, who seek to enhance their career progression.

Following the studies of previous literature, this section also uses the four types to categorize the motivations of academic expatriates and additionally add the family type for further explanation.

3.1 Explorer type

Explorer-type expatriates are primarily motivated by personal desires to travel (Richardson and McKenna, 2002). These individuals often possess adventurous spirits, are attracted to different cultures, and are willing to travel for work. Previous literature has examined the geographical and demographic characteristics of this type. Geographically, there is a trend of movement from Western countries to Asian countries, as Asia is seen as mysterious and attractive and worthy of exploration (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Cai and Hall, 2015). Demographically, the explorer type is generally younger and unmarried (Lauring et al., 2014).

As the explorer spirts can drive expatriates to explore unfamiliar places, the spirits are assumed to empower them in working (Wilkins and Neri, 2018). However, Richardson and McKenna’s (2002) study on explorer types focuses more on the exploration of new places. This may overlook the contributions to work that arise from adventurous spirits. Specifically, the novelty of a new context often comes with a sense of academic freedom, allowing expatriates to demonstrate their capabilities (Tahir, 2023). For example, the novel context can inspire some expatriates to develop new ideas or pursue their ambitions to excel in a new campus and gain global experiences in different settings (Cai and Hall, 2015). As this type’s contributions to work overlap with those of the architect type discussed in the following section, it is undeniable that the architect spirit partly stems from exploratory spirits.

3.2 Refugee type

Previous literature has studied refugee-type expatriates by examining push factors, which primarily focus on competitive career opportunities and poor market conditions (Kurek-Ochmańska and Luczaj, 2021; Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022; Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Tahir, 2023), as well as smaller amounts on uncomfortable living environments (Cai and Hall, 2015; Harry et al., 2019). A possible explanation for the competitive working environment is the competitive labor market in developed countries, meaning academics in these areas are more likely to miss out on research opportunities (Cai and Hall, 2015). As a result, some expatriates may choose to migrate to less competitive contexts to continue their research or seek desired positions and opportunities for promotion (Kurek-Ochmańska and Luczaj, 2021).

When the host context is closely aligned with the expatriates’ research field, it becomes an advantage that drives them to “escape from” their unfavorable contexts (Jepsen et al., 2014). Typical examples can be found in academic peripheries, which are regarded as a final option for research-orientated expatriates to develop their careers as researchers (Kurek-Ochmańska and Luczaj, 2021; Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022). Although the rewards and work conditions might be less satisfactory, the research opportunity and international experience are precious enough for migration.

3.3 Mercenary type

Most countries can offer extra remuneration packages or research allowances to academic expatriates, but the benefits vary significantly due to local government policies, tax regulations, and economic wealth (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Cai and Hall, 2015; Tahir, 2023; Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022). For example, many institutions in the United Arab Emirates are able to offer competitive salaries and living allowances that are often superior to those at the home campus and provide advantageous benefits on tax (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Wilkins and Neri, 2018). In contrast, some academic expatriates in South Africa earn less than local staff despite being more qualified due to limitations from contracts (Harry et al., 2019).

It is worth mentioning that most host campuses are in developing countries (as illustrated in the previous section), which usually cannot offer the same benefit packages as Western campuses due to the lower cost of living and uncompetitive labor market (Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Lauring et al., 2014; Jepsen et al., 2014). Apart from few a wealthy regions such as the United Arab Emirates, most branch campus can only afford higher salaries compared to local universities in the host country. Therefore, finance is less likely to be a primary reason driving expatriates to move to lower-income regions than opportunity-seeking.

3.4 Architect type

Architect-type expatriates focus more on the contributions they could make at the institutional level or on the benefits gained by sharing their experiences. Therefore, this type is mostly comprised of older expatriates who are experienced in teaching or management and believe they play an important role in shaping a campus (Cai and Hall, 2015; Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Tahir, 2023).

The architect type shows different career objectives across age groups: younger expatriates are more focused on “promotion,” but older expatriates prioritize “contribution” to the university (Cai and Hall, 2015, p. 213). Younger academics tend to view working at a branch campus as a stepping stone for promotion or further career opportunities since more responsibilities can be offered at branch campuses.

3.5 Family type

In addition to the four types, family factor is another motivation that falls outside Richardson and McKenna’s (2002) scope but is worth mentioning. This type of expatriate seeks to migrate closer to family members who already reside in the host country or to seek better life opportunities for their children (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Jepsen et al., 2014; Schartner et al., 2022; Kurek-Ochmańska and Luczaj, 2021; Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022). In some fast-growing countries like China, expatriates see working there as a chance to enhance their children’s future opportunities (Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Cai and Hall, 2015). This type of expatriation is driven by personal demands and relationships, with little connection to the host context.

4 Results: what challenges do expatriates face when working in international branch schools?

Transferring jobs is a stressful event, especially in an international context where unfamiliar expectations are placed by a new institution and work environment. This study systematically reviews the challenges faced by academic expatriates in their work, which are rooted in the contextual dilemma between local adaptation and global integration.

4.1 Challenges from complex campus context and management

The review of the selected literature found that the challenges faced by expatriates are mostly rooted in the conflicting context and insufficient support offered by management, eventually leading to academic staff having to navigate contradictory requirements. In discussing the context of branch campuses, Shams and Huisman (2011, p.114) highlight “the dilemma of standardization versus local adaption” by adopting the “global integration” and “local responsiveness” dichotomy in business management literature. Specifically, this dilemma can be found in curriculum delivery, staffing management, and quality assurance. For example. with resource adaption, one side attempts to maintain the same standards and reputation as that of the home campus, while another stresses conformity with local regulations and demands.

Apart from the context dilemma between local adaptation and global integration, branch campus management also need to balance different motivations from the home and host sides. For the home campus, the main motivation is to expand revenue streams and global presence, while for the host side, enhancing local educational capacity to foster social-economic development is the primary needs (Hickey and Davies, 2022; Escriva-Beltran et al., 2019; Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Healey, 2015; Shams and Huisman, 2011; Wilkins and Annabi, 2021). Therefore, a leadership board with international vision and management experiences is necessary. Furthermore, the leadership board should include the voices of both the home and host institution to coordinate benefits and regulations. Feng (2012) highlighted the importance of leadership boards with vision and management expertise through the successful governance models of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) and the University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC). It was found that balanced leadership and international management offer valuable insights into the effective governance of these institutions (Scott, 2021; Zhan and Marginson, 2023). While UNNC’s board has equal representation from China and the UK, ensuring balanced decision-making, XJTLU’s board also enables strategic alignment with a Chinese majority and Liverpool’s input. Both campuses have a balanced board structure, which allows them to maintain political and economic support from partners on both sides, while also facilitating smooth operations and ensuring compliance with local regulations (Hickey and Davies, 2022).

While some institutions are able to provide institutional support and present a clear mission, for small-scale and newer institutions, resources and experience are more limited. Wood and Salt (2017) analyzed the management challenges of UK branch campuses compared with multinational enterprises, noting differences in infrastructure, career progression, and unsustainable staffing systems. International branch campuses often partner with local organizations to provide resources like facilities and staff (Wilkins, 2020). Many academic staff are employed by the local partner, not the foreign university, with contracts that differ significantly from those at the home campus (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021). Compared with multinational enterprises, international branch campuses often lack competent human resource departments to secure the career and research benefits of expatriates. This should be planned and organized beforehand to ensure quality and good coordination among parties as the institution expands.

4.2 Challenges from teaching

As key recourses for transferring advanced skills from the home campus, academic expatriates are expected to deliver the same high-quality content. Lamers-Reeuwijk et al. (2019) highlighted that quality assurance extends beyond lecture outcomes and includes requirements such as critical thinking and practical abilities. Although the curricula and teaching materials are provided by the home campus, almost all selected studies mentioned the challenges faced when adapting home campus materials to new contexts while still maintaining quality (Schartner et al., 2022; Wood and Salt, 2017; Harry et al., 2019; Jepsen et al., 2014; Cai and Hall, 2015; Escriva-Beltran et al., 2019; Wilkins and Neri, 2018).

Previous studies discuss teaching adaptions, such as matching students’ learning styles through extensive guidance and transforming teaching styles (Schartner et al., 2022; Cai and Hall, 2015), tailoring lecture content to local workplace demands and education system needs (Escriva-Beltran et al., 2019; Wood and Salt, 2017), and advocating home campus values and maintaining quality (Lamers-Reeuwijk et al., 2019). However, most expatriates view the branch campus as a micro-replication of the home campus that provides high quality Western-style education before starting expatriation (Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Wilkins and Annabi, 2021). After perceiving the inconsistence, they may struggle with cultural and structural differences inherent in the host institution. What’s even worse is effective induction processes are often lacking due to management issues as discussed previously. This balancing act can create stress and confusion among staff as they attempt to satisfy both sets of expectations without clear guidelines.

Apart from the burden of meeting expectations at both the host and home campuses, excessive workloads are another common issue at most branch campuses. Because many branch campuses are self-funding and rely heavily on tuition revenue, they may need to maintain quality teaching through smaller class sizes and extensive support to attract and retain students (Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Cai and Hall, 2015; Escriva-Beltran et al., 2019). The teaching loads also vary from different contexts and impacted by campus hierarchy and seniority (Jepsen et al., 2014). In some teaching-intensive countries with strong heirarchies, China, for example, lower position staff may face more pressure in work and have to teach the same or more modules than they would at the home campus.

4.3 Challenges from research

Expatriates at branch campuses may lack research support including research network, home campus support and fair opportunities in host campus (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Cai and Hall, 2015; Tahir, 2023). Unlike when at home institutions, academics at branch campuses may have limited abilities to attract funds or research opportunities due to their being treated as an outsider (Harry et al., 2019). However, in some research-intensive branch campuses, they expect expatriates to produce the same quality and quantity research as in home campus, but the workloads are not explicitly allocated in their contract (Cai and Hall, 2015; Schartner et al., 2022; Luczaj, 2020). Therefore, it is difficult for expatriates to focus on research with limited resources and time.

Academic freedom is a prominent issue in politically sensitive countries, where foreign expatriates are viewed as a threat to the local culture. Expatriates must avoid discussing inappropriate subjects and may feel as if they are being monitored in some politically sensitive countries, ex. China (Cai and Hall, 2015). Political issues may also limit career promotion due to strict restrictions on national identity and political membership, preventing expatriates from obtaining research funds or joining local research committees (Tahir, 2023; Harry et al., 2019). In Mexico, promotion is influenced by international relations with the home country (Luczaj and Holy-Luczaj, 2022). As most expatriates view research opportunities and career growth as vital reasons for expatriation, identity prejudice presents challenges to obtaining the same resources and qualifications as local colleagues.

4.4 Challenges from connection with home campus and local colleagues

Expatriates at branch campuses often have limited connections with their home campus. At the institutional level, home campuses do not view branch operations as integrated and typically have weak understandings of branch context issues (Cai and Hall, 2015; Wood and Salt, 2017). Consequently, they cannot respond appropriately and in a timely fashion to the needs of branch campuses. At the individual level, attitudes from home campus staff are often described as unsupportive and arrogant. Cross-campus collaborations are perceived as unfair since branch campuses usually have little say in lecture content (Cai and Hall, 2015; Lamers-Reeuwijk et al., 2019). For expatriates, they need to actively build connections with the home campus and remain visible if they expect to obtain more career opportunities.

On many campuses, academic staff are recruited internationally, while administration and support staff are locally recruited, sometimes leading to conflict due to differences in administrative structure. Organizational structures can be heavily influenced by cultures, with individualist or collectivist cultures having starkly different structures (Jepsen et al., 2014). The structure difference can influence work relationships with mangers and colleagues.

Academic expatriates face challenges in daily work and interactions in countries where English is not the primary language. Language barriers significantly hinder full participation in internal meetings or training sessions when sufficient translation is lacking, and communication with locally recruited administrative staff can also be a challenge (Kurek-Ochmańska and Luczaj, 2021; Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Schartner et al., 2022; Cai and Hall, 2015). These challenges negatively impact expatriates’ adaptation to the work environment, their ability to excel in their roles, and can lead to feelings of isolation.

4.5 Challenges from career development and promotion opportunities

Most studies reported that work visas add insecurity to expatriate careers, as countries typically allow only short-term work visas (usually 3 years), which must be renewed for individuals seeking longer careers at branch campuses (Wilkins and Annabi, 2021; Tahir, 2023; Wilkins and Neri, 2018; Schartner et al., 2022). Due to visa conditions, academic expatriates can only be offered short-term job contracts, which are shorter than those for local employees. This makes it difficult for expatriates to make continuous career progression within a short period.

Multinational corporations can provide career development support to expatriates whether they remain in the host country or return home (Wood and Salt, 2017). However, academic expatriates in branch campus should decide clearly on their career path beforehand due to the conflict in campus management (Shams and Huisman, 2011). Therefore, before expatriating, it is better for expatriates to be clear on their motivations and how they expect the expatriation to benefit their career. It is also important to remain visible to the home institution and obtain opportunities in future research and career development.

5 Conclusion

This literature review has examined the motivations and challenges faced by academic expatriates at international branch campuses, shedding light on a topic of increasing interest in the global academic landscape. The findings reveal that motivations for expatriation are multifaceted, encompassing various archetypes: explorer, refugee, mercenary, architect, and family. Each factor is driven by differing personal reasons, such as career or escaping an unfavorable external environment. Among the motivations, self-fulfillment seems to be a strong factor. By analyzing the initial impetus for moving, institution managers could have a better overall understanding when recruiting expatriates on how to increase their job satisfaction when integrated in the host country.

The literature search uses only two databases, which may result in excluding relevant studies published in other sources—a limitation of this study. Additionally, the study uses secondary data that may limit deeper insights into the practical experiences of academic expatriates. Despite these limitations, the study adheres strictly to the PRISMA guidelines, which ensures transparency and rigor in the review process. The search terms, inclusion criteria, and selection process are openly reported in the study. Furthermore, the review identifies key challenges in the field and provides valuable insights for future research and practice.

The challenges identified in this review underscore the complex reality faced by academic expatriates. These challenges are rooted in systematic issues, spanning from career progression to the balance between maintaining global academic standards and adapting to local contexts. The challenges encountered are exacerbated by the insufficient support structures and unclear policies at host institutions. As a result, expatriate academics may experience job dissatisfaction that can hinder effective integration into the host academic community.

The insights gained from this review are invaluable for university administrators and policymakers. There is a clear need for developing comprehensive management strategies that facilitate the recruitment and integration of academic expatriates and support their long-term retention and career development. Such strategies should be tailored to address the specific motivations and challenges of each expatriate type to ensure that each individual feels valued and supported throughout their tenure at their international branch campus.

This review highlights a gap in the literature concerning the long-term impacts of expatriation on both the individuals involved and their host institutions. However, there still exists questions on how these challenges and motivations change over time as expatriates settle into their roles and become more integrated (or not) in the host institution. Future research should address this gap by conducting longitudinal studies that provide deeper insights into the long-term outcomes of academic expatriation. Such research could include the impact on personal and professional development (Al-Tamimi and Abdullateef, 2023), contributions to the host institution (Maharjan et al., 2021), and the eventual reintegration into the home country or further international moves (Wilkins et al., 2017; James and Azungah, 2021).

Author contributions

YY: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Project administration, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank ZY of School of Education and Professional Studies, Griffith University for his support on topic discussion and academic data access in this study. My sincere thanks also go to editors and reviewers for all the efforts and time.

Conflict of interest

YY was employed by Siemens Ltd., China in Beijing, China.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1457278/full#supplementary-material

References

Al-Tamimi, N. N., and Abdullateef, S. T. (2023). Towards smooth transition: enhancing participation of expatriates in academic context. Cogent Soc. Sci. 9. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2023.2185986

Cai, L., and Hall, C. (2015). Motivations, expectations, and experiences of expatriate academic staff on an international branch campus in China. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 20, 207–222. doi: 10.1177/1028315315623055

Dai, K., Wilkins, S., and Zhang, X. (2023). Understanding contextual factors influencing Chinese students to study at a Hong Kong institution’s intra-country branch campus. J. Stud. Int. Educ. doi: 10.1177/10283153231205079

Despotovic, W. V., Hutchings, K., and McPhail, R. (2022). Business, pleasure or both?: motivations and changing motivation of self-initiated expatriates. J. Manag. Organ. 1–26, 1–26. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2022.38

Dobos, K. (2011). “Serving two masters” – academics’ perspectives on working at an offshore campus in Malaysia. Educ. Rev. 63, 19–35. doi: 10.1080/00131911003748035

Duffy, L. P. (2024). “Navigating pandemic challenges” in Advances in educational marketing, administration, and leadership book series, 150–175.

Escriva-Beltran, M., Muñoz-De-Prat, J., and Villó, C. (2019). Insights into international branch campuses: mapping trends through a systematic review. J. Bus. Res. 101, 507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.049

Feng, Y. (2012). University of Nottingham Ningbo China and Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University: globalization of higher education in China. High. Educ. 65, 471–485. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9558-8

Harry, T. T., Dodd, N., and Chinyamurindi, W. (2019). Telling tales. J. Global Mobil. 7, 64–87. doi: 10.1108/jgm-05-2018-0024

Healey, N. M. (2015). The challenges of leading an international branch campus. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 20, 61–78. doi: 10.1177/1028315315602928

Hickey, R., and Davies, D. (2022). The common factors underlying successful international branch campuses: towards a conceptual decision-making framework. Glob. Soc. Educ. 22, 364–378. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2022.2037072

James, R., and Azungah, T. (2021). Repatriation of academics: re-socialisation and adjustment. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 25:178. doi: 10.1504/ijbex.2021.119454

Jepsen, D. M., Sun, J. J., Budhwar, P. S., Klehe, U., Krausert, A., Raghuram, S., et al. (2014). International academic careers: personal reflections. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 25, 1309–1326. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.870307

Kurek-Ochmańska, O., and Luczaj, K. (2021). ‘Are you crazy? Why are you going to Poland?’ Migration of Western scholars to academic peripheries. Geoforum 119, 102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.12.001

Lamers-Reeuwijk, A. M., Admiraal, W. F., and Van Der Rijst, R. M. (2019). Expatriate academics and transnational teaching: the need for quality assurance and quality enhancement to go hand in hand. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 39, 733–747. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1693516

Lauring, J., Selmer, J., and Jacobsen, J. K. S. (2014). Business or pleasure? Blurring relocation categories and motivation patterns among expatriates. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 14, 170–186. doi: 10.1080/15022250.2014.900286

Luczaj, K. (2020). Overworked and underpaid: why foreign-born academics in Central Europe cannot focus on innovative research and quality teaching. High Educ. Pol. 35, 42–62. doi: 10.1057/s41307-020-00191-0

Luczaj, K., and Holy-Luczaj, M. (2022). International academics in the peripheries. A qualitative meta-analysis across fifteen countries. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 32, 1126–1151. doi: 10.1080/09620214.2021.2023322

Maharjan, M. P., Stoermer, S., and Froese, F. J. (2021). Research productivity of self-initiated expatriate academics: influences of job demands, resources and cross-cultural adjustment. Eur. Manag. Rev. 19, 285–298. doi: 10.1111/emre.12470

Neri, S., and Wilkins, S. (2018). Talent management in transnational higher education: strategies for managing academic staff at international branch campuses. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 41, 52–69. doi: 10.1080/1360080x.2018.1522713

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). Web of science (WOS) and Scopus: the titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publica 9:12. doi: 10.3390/publications9010012

Paniagua, J., Villó, C., and Escrivà-Beltran, M. (2022). Cross-border higher education: the expansion of international branch campuses. Res. High. Educ. 63, 1037–1057. doi: 10.1007/s11162-022-09674-y

Pranckutė, R. (2021). Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus: the titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications, 9, 12. doi: 10.3390/publications9010012

Przytula, S. (2023). Expatriate academics: what have we known for four decades? A systematic literature review. J. Global Mobil. 12, 31–56. doi: 10.1108/jgm-03-2023-0024

Richardson, J., and McKenna, S. (2002). Leaving and experiencing: why academics expatriate and how they experience expatriation. Career Dev. Int. 7, 67–78. doi: 10.1108/13620430210421614

Schartner, A., Young, T. J., and Snodin, N. (2022). Intercultural adjustment of internationally mobile academics working in Thailand. High. Educ. 85, 483–502. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00846-4

Scott, T. (2021). UK IBCs’ adaptability in mainland China: programs, practices, and policies. Int. J. Educ. Organ. Leader. 29, 13–23. doi: 10.18848/2329-1656/cgp/v29i01/13-23

Selmer, J., and Lauring, J. (2010).Self‐initiated academic expatriates: Inherent demographics and reasons to expatriate. European Management Review, 7, 169–179. doi: 10.1057/emr.2010.15

Selmer, J., and Lauring, J. (2012). Reasons to expatriate and work outcomes of self-initiated expatriates. Pers. Rev. 41, 665–684. doi: 10.1108/00483481211249166

Shams, F., and Huisman, J. (2011). Managing offshore branch campuses. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 16, 106–127. doi: 10.1177/1028315311413470

Tahir, R. (2023). Expatriate academics: an exploratory study of western academics in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 16, 641–657. doi: 10.1504/ijmp.2023.133218

Trembath, J. (2016). The professional lives of expatriate academics. J. Global Mobil. 4, 112–130. doi: 10.1108/jgm-04-2015-0012

Van Niekerk, A., and Mhlanga, M. (2024). Expatriate academics’ adjustment experience at a higher education institution in South Africa. Acta Commercii 24. doi: 10.4102/ac.v24i1.1210

Wilkins, S. (2020). Two decades of international branch campus development, 2000–2020: a review. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 35, 311–326. doi: 10.1108/ijem-08-2020-0409

Wilkins, S., and Annabi, C. A. (2021). Academic careers in transnational higher education: the rewards and challenges of teaching at international branch campuses. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 27, 219–239. doi: 10.1177/10283153211052782

Wilkins, S., Butt, M. M., and Annabi, C. A. (2017). The effects of employee commitment in transnational higher education: the case of international branch campuses. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 21, 295–314. doi: 10.1177/1028315316687013

Wilkins, S., and Neri, S. (2018). Managing faculty in transnational higher education: expatriate academics at international branch campuses. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 23, 451–472. doi: 10.1177/1028315318814200

Wood, P., and Salt, J. (2017). Staffing UK universities at international campuses. High Educ. Pol. 31, 181–199. doi: 10.1057/s41307-017-0049-5

Zhan, T., and Marginson, S. (2023). Institutional dual identity in research capacity building in IBCs: the case of NYU Shanghai. High. Educ. 87, 471–490. doi: 10.1007/s10734-023-01017-9

Keywords: expatriates motivations, work integration challenges, academic expatriates, international branch campuses, transnational higher education, expatriate challenges

Citation: Yao Y and Yang Z (2024) The motivations and challenges for academic expatriates in international branch campuses. Front. Educ. 9:1457278. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1457278

Edited by:

Aziza Mahomed, University of Birmingham, United KingdomReviewed by:

Carol Nash, University of Toronto, CanadaBarbara Jones, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Sylvia Rozza, Jakarta State Polytechnic, Indonesia

Gareth Morris, The University of Nottingham Ningbo China, China

Copyright © 2024 Yao and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhi Yang, emhpLnlhbmcyQGdyaWZmaXRodW5pLmVkdS5hdQ==

Yao Yao

Yao Yao Zhi Yang

Zhi Yang