- Business & Economics School, Lisbon, Portugal

In the current educational context, transformations are continuous, and the ethical dimension of leadership has become one of the main concerns of school cluster directors, given its direct influence on teachers’ motivation. This study, conducted with a sample of 204 teachers from public schools in Portugal, aimed to investigate the relationship between ethical leadership, motivation, and commitment. The results revealed that ethical leadership is positively correlated with intrinsic motivation and organizational commitment (OC). On the other hand, despotic leadership exhibits a negative correlation with OC and intrinsic motivation. Furthermore, it was found that commitment plays a mediating role in the effect of ethical leadership on teachers’ intrinsic motivation. These findings underscore the importance of promoting ethical leadership in schools, not only to foster teachers’ motivation but also to strengthen their commitment to the institution. Conversely, the need to avoid despotic practices is emphasized, as they can adversely affect not only teachers’ motivation but also their commitment to the educational organization. These conclusions further highlight, as future research avenues, the importance of promoting ethical leadership in educational institutions to ensure a healthy and productive work environment for teachers.

1 Introduction

The role of the teacher is influenced by the historical, cultural, and political context, being a concept in constant evolution (Carvalho, 2016). This evolution is affected by factors such as bureaucracy, greater accountability, and public scrutiny (Carvalho, 2016; Flores, 2016). In this context, the leader (i.e., the school director) has a particularly important role in that he can articulate, encourage, and mobilize his followers—teachers, specialized technicians, and educational assistants—to achieve the goals related to the construction of quality education, the improvement of the skills acquired, and the academic results obtained by students. Over the past few years, the topic of leadership in educational institutions has been addressed as one of the key variables for the development of teachers and schools (Flores, 2016). Several studies stand out in terms of the historical evolution of the theme, such as that of Bass and Bass (2008) or Yukl et al. (2002), that of Blackmore (2004) in Australia, the comparative study between Portugal and England by Day et al. (2007), the meta-analysis on educational leadership in Portugal by Costa and Figueiredo (2013), the systematic literature review by Castanheira and Costa (2011) and Jacobs et al. (2016) in the USA, and Frost (2012) and Muijs and Harris (2006) in the United Kingdom.

Considering the perspective of Ryan and Deci (2022) on motivation and the principles that circumscribe the theory of self-determination, school leaders assume particular relevance in promoting contexts with a low level of control that encourage autonomy, where each individual can pursue their own choices, as well as internalizing and integrating norms and values. In other words, school leaders have the responsibility to promote the creation of organizational climates that increase the satisfaction of teachers’ autonomy and relationship needs (Esteves et al., 2016; Gil and Machado, 2016).

Leadership styles can thus contribute positively to a teacher’s affective commitment to the school (Mahmoud et al., 2023), in particular, through the support provided to teachers and the development of a positive school climate (i.e., Day et al., 2007). In addition to the leadership of school principals, other factors have been identified as catalysts or inhibitors of teachers’ commitment (Flores, 2016; Getahun et al., 2016) such as, for example, those relating to national education policies, support administrative, student behavior, and parental demands (Xiao and Wilkins, 2015).

Through this route, school leaders can contribute to increasing teachers’ intrinsic motivation, promoting full internalization of extrinsic motivation, and affective commitment to the school. Finally, school leaders can contribute to job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing perceived by teachers, and with this, bring consequent positive attitudes toward work on the part of teachers at school (Franco and Silva, 2022).

1.1 Leadership and ethics in an educational context

Ethical and moral leadership in the educational context has been a growing concern, with significant effects on relationships and organizational activity (Cumlat et al., 2023; Yukl et al., 2002). Furthermore, the impact on the psychosocial health of everyone involved in the educational process is significant (Yukl et al., 2002; Leithwood, 2022). Educational leadership, also faces challenges, including isolation, the management of ambiguity, and the adoption of ethical principles in conduct, among others (Graça da Costa et al., 2024).

The most developed leadership model in schools has been the transformational leadership model (Leithwood, 2022), which conceptualizes leadership in the following seven dimensions: 1. building a vision for the school; 2. establishing objectives for the school; 3. stimulating intellectually; 4. offering individual support; 5. modeling good practices and important organizational values; 6. demonstrating high-performance expectations and creating a productive school culture; and 7. developing structures that facilitate participation in school decisions. From this perspective, transformational leaders can produce organizational change and contribute to job satisfaction and performance at the individual, group, and educational context levels (York-Barr and Duke, 2022). This, both at the level of individual teachers, the teaching class, and the school as an organizational structure, must stimulate higher levels of intrinsic motivation, organizational trust, and commitment (Leithwood, 2022).

These perceptions of leadership, judgments, and representations constructed about leaders and leadership can be affected by several variables, such as age group and training, and by other conditions, such as length of service in the profession (Araşkal and Kilinç, 2019; Getahun et al., 2016).

Some authors, such as Rego and Braga (2017), defend the transformational leadership model as it integrates the concepts of values and ethics into leadership. Therefore, despite the positive effects arising from transformational leadership, the principle that the ethical and moral assessment of leadership cannot end in analyzing the consequences of leadership itself must be taken into account. It is, therefore, necessary to differentiate the moral character of the leader and the ethical legitimacy of the values embedded in the vision and their respective articulation of the morality of the processes of choice and action that leaders and followers embrace and pursue.

Conceptualizations of leadership have therefore emerged with the aim of narrowing the focus on ethical and moral issues, seeking to substantiate and develop conceptually and operationally the construct of ethical and moral leadership and to understand the impact of the ethical and moral dimension of leadership (Cumlat et al., 2023).

Regarding the ethical and moral issues of leadership, Bass and Avolio (1993) recognize that the ethical dimension of transformational leadership is in itself morally neutral, that is, without differentiation of the moral values underlying its behavior. Ultimately, two leaders can adopt identical transformational behaviors and even have similar consequences. However, it is the underlying values that allow an individual to identify the ethical and moral dimensions of their behavior. Howell and Avolio (1992) add that transformational leaders can act both ethically and unethically, depending on the values they incorporate in their vision and strategic guidance. To give greater appreciation to the ethical dimension in leadership and promote understanding of the impact of ethical leaders on their followers, the concept of ethical leadership and the models associated with this construct emerge (Cumlat et al., 2023).

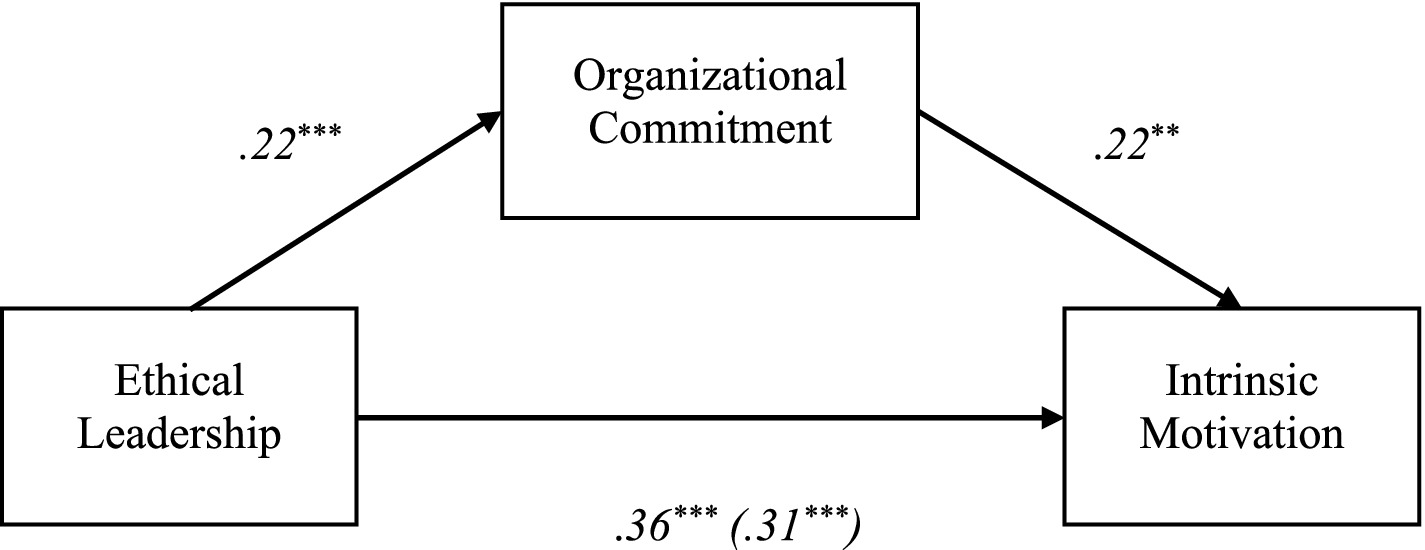

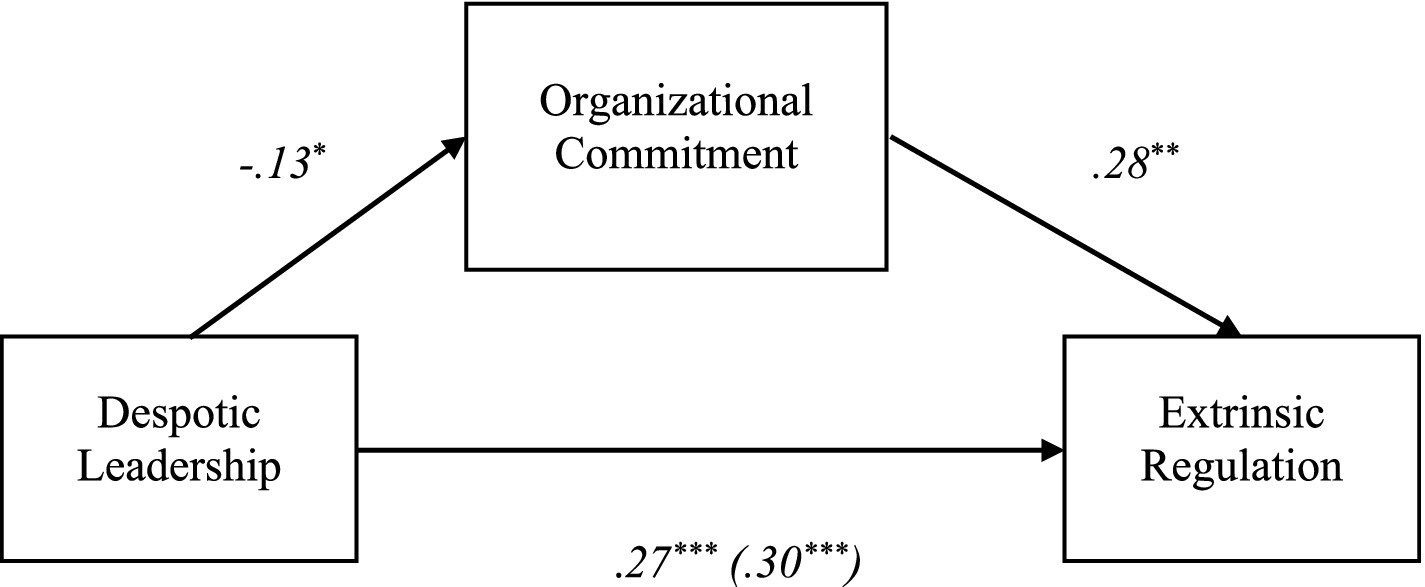

From this perspective, ethical leadership is defined as the “demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct to be carried out through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al., 2005, p. 120). Ethical leadership is a construct that can be measured through four dimensions: morality and justice, power-sharing, role clarification, and despotic leadership (Hoogh et al., 2008). In this multidimensional approach to ethical leadership, there is an antagonistic relationship between the notions of ethical leadership and despotic leadership. Ethical leadership reflects behaviors that meet the interests of followers, and despotic leadership, on the contrary, reflects authoritarian behavior, which serves the leader’s own interests. Thus, they constitute independent constructs, negatively correlated and measured by the aforementioned dimensions: morality and justice, power-sharing, role clarification, and despotic leadership (Hoogh et al., 2008) (see Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between ethical leadership and intrinsic motivation mediated by organizational commitment. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2. Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation mediated by organizational commitment. *p <0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

1.2 Motivation in an educational context

Work motivation is defined as “a set of energetic forces that originate both within as well as beyond an individual’s being, to initiate work-related behavior, and to determine its form direction intensity and duration” (Latham and Pinder, 2005, p.486).

The self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2022) proposes a multidimensional view of motivation and distinguishes how different types of motivation can be promoted or discouraged. From this perspective, there are three possible types of motivation: amotivation, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation. Amotivation is defined as the lack of motivation for an activity (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2022). Intrinsic motivation is the ability to do an activity for its own sake, that is, because it is interesting and enjoyable (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2022). In contrast, extrinsic motivation refers to the commitment to activities for instrumental reasons (receiving rewards, being approved, avoiding punishments and/or disapproval, increasing self-esteem, or reaching a personally valued goal) (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2022).

The first form of extrinsic motivation, which is not completely internalized, is an external regulation that envisages carrying out an activity to obtain rewards (Bizarria et al., 2018). Introjected regulation is defined as the regulation of behavior through the internal pressure of ego forces, namely shame and guilt, which is known as ego involvement. This form of internalization is experienced as internal control (Bizarria et al., 2018). Finally, identified regulation presupposes that an activity is carried out because it identifies in a volatile way with its value or meaning, which is accepted as one’s own. Identified regulation differs from intrinsic motivation in activities in which it is not carried out for internal satisfaction, but for the instrumental value it represents (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2022). In contrast, internally controlled motivation has been the explanation for most desirable behavioral, attitudinal, and affective outcomes (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2022).

From the perspective of SDT (Ryan and Deci, 2017), it is emphasized that school leaders must promote contexts that encourage autonomy, in which people can exercise their own choices and internalize/integrate norms—a low level of control. In this way, the chance arises of participating in decisions and promoting understanding in the face of possible negative feelings, when it is necessary to carry out a difficult task, as well as the development of a meaning for the activities to be carried out.

Leadership in an educational context can thus constitute an agent of motivation and reinforcement of intrinsic motivation for teachers to motivate themselves, implying that the principal is accessible, fair, and firm with parents and students (Jacobs et al., 2016). Principals can also be essential agents in developing teachers’ support and motivation, justice and trust, as well as being concerned about their personal and professional growth and development (Frost, 2012; Jacobs et al., 2016).

1.3 Teacher commitment

According to Mowday et al. (1982), the concept of commitment was characterized by a strong belief in the acceptance of goals and values, the willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization, and a strong desire to maintain participation in it. Organizational commitment (OC) has been studied both as a contextual variable and a mediating variable of leadership (Cunha et al., 2021) and has been identified as one of the most important factors for the success of education (Getahun et al., 2016; Xiao and Wilkins, 2015).

OC has been defined as a predictor of teachers’ performance at school, contributing to the prevention of teacher burnout (Day, 2001). Teachers’ OC also has an important influence on students’ cognitive, social, behavioral, and affective results (Day, 2001). This is a concept that is assumed to be a part of the teacher’s professional life and can be increased or decreased by factors that have already been mentioned previously, such as the leadership of principals, student behavior, administrative support, the demands of parents as well as national education policies (Day, 2001). Teachers who are committed have the lasting belief that they can make a difference in students’ lives and learning paths (effectiveness and efficiency) through who they are (their identity), what they know (knowledge, strategies, and skills), and how they teach (i.e., their beliefs, attitudes, personal, and professional values incorporated into their behaviors) (Franco and Silva, 2022; Gagné et al., 2014).

In the model of commitment as a factor in the effectiveness of teacher performance (Meyer et al., 1993), OC is conceptualized as being divided into three components that can coexist with each other: affective, normative, and calculative (continuity). Affective OC can be defined as an emotional identification with the organization; the normative is the perceived obligation (ethical or moral) to remain in the organization. Finally, the calculation is defined as the perceived cost of leaving the organization (such as loss of seniority or lower wages).

OC has been referred to as having a mediating effect on variables such as satisfaction, organizational climate, and work motivation (Choi et al., 2015; Demirtas and Akdogan, 2014; Lyndon and Rawat, 2015).

In short, improving the perception of the level of teacher training, that is, the way in which teachers feel capable of responding to the challenges that the school poses to them, contributes to feelings of commitment to the school on the part of the teacher and to their commitment to students (Franco and Silva, 2022).

In this way, school leaders will be able to enhance teachers’ motivation, commitment to school, effective performance, satisfaction, and positive attitudes toward work and psychological wellbeing (e.g., Franco and Silva, 2022).

Considering that there may be ethical or less ethical (despotic) behaviors on the part of the educational leader toward teachers and that commitment may constitute a mediating variable of leadership, and that leadership may have a positive impact on motivation, this study aims to verify, in an educational context, what is the relationship established between ethical leadership, OC, and teacher motivation.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

The sample for this study consists of 204 teachers from 30 school groups in the north (Oporto district) and center of the country (Aveiro district). Of these participants, 156 (76.5%) were female and the remaining 48 (23.5%) were male. Regarding age, 26 (12.7%) participants are between 20 and 40 years old, 87 (42.6%) are between 40 and 50 years old and 91 (44.6%) are between 50 and 60 years old. Regarding years of experience, 18 (8.8%) participants have up to 15 years of experience, 43 (21.1%) participants have between 15 and 20 years of experience, 45 (22.1%) have between 20 and 25 years of experience, and 98 (48.0%) have more than 25 years of professional experience.

2.2 Instruments

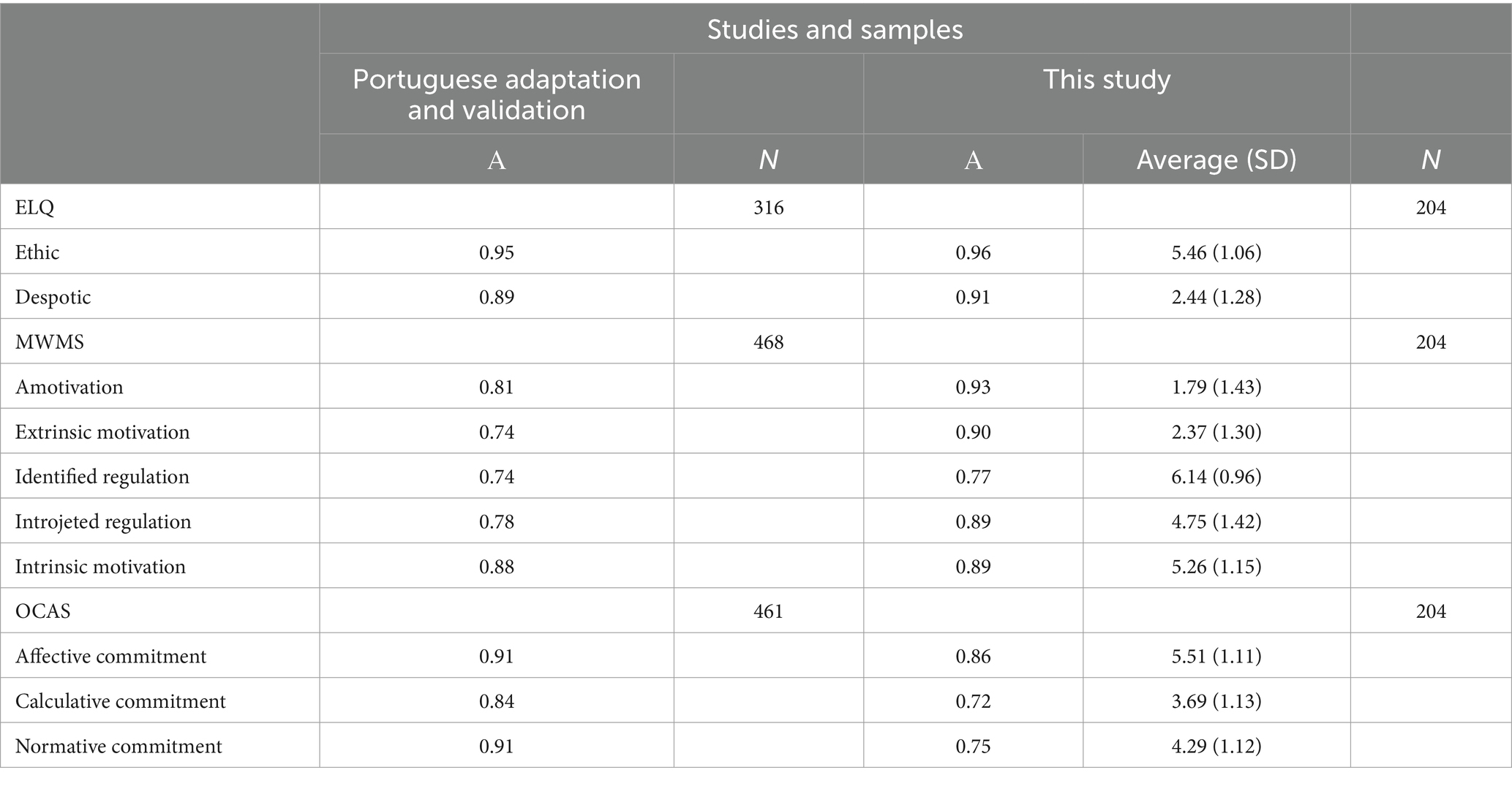

The assessment protocol was composed of the sociodemographic questionnaire constructed for the present study, the Ethical Leadership Questionnaire (ELQ; Hoogh et al., 2008; Portuguese version of Neves et al., 2016), the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (MWMS; Gagné et al., 2014; Portuguese version of Escala Multi-Factorial de Motivação no Trabalho; Coimbra in press) and the OC Assessment Scale (Meyer et al., 1993; Portuguese version of Nascimento et al., 2008).

The sociodemographic questionnaire allowed the collection of information on age and gender, and years of professional experience.

The ELQ (Hoogh et al., 2008; Portuguese version by Neves et al., 2016) constitutes an adaptation and validation for the Portuguese population of the Ethical Leadership Scale, consisting of 23 items, rated on a typical 7-point Likert scale. It allows evaluating ethical leadership in two dimensions: (1) ethical leadership—considers the way in which leaders should behave ethically and morally (α = 0.96); (2) despotic leadership—reflects authoritarian behavior that serves the leader’s own interests (α = 0.91).

The MWMS (Gagné et al., 2014; Portuguese version of Neves, 2018) is a multidimensional scale consisting of 19 items, with the objective of assessing motivation for work. This encompasses 5 dimensions: (1) amotivation (α = 0.93); (2) external regulation (α = 0.90); (3) identified regulation (α = 0.77); (4) introjected regulation (α = 0.89); and (5) intrinsic motivation (α = 0.89). These dimensions assess the different levels of motivation for work, from the absence of motivation (amotivation) to the optimal level of motivation (intrinsic motivation). Items in each dimension are evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale.

The OCAS (Meyer and Allen, 1991; Meyer et al., 1993; Portuguese version by Nascimento et al., 2008) is a multidimensional questionnaire consisting of 19 items, which assesses the level of worker commitment to the organization. It encompasses the three components that constitute OC: affective (α = 0.86), calculative (α = 0.72), and normative (α = 0.75). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale.

2.3 Research hypotheses

The present study is focused on the following research hypotheses:

1. The perception of ethical leadership is positively correlated with OC and intrinsic motivation;

2. The perception of despotic leadership is negatively correlated with OC and intrinsic motivation;

3. The perception of ethical leadership may be a predictor of intrinsic motivation mediated by OC;

4. The perception of despotic leadership may be a predictor of extrinsic regulation mediated by OC.

2.4 Procedures

Face-to-face contact was made with the directors of 30 secondary schools and groups of public schools in the north and center of the country, to whom the objectives were explained, and participation in the present study was requested. Following the acceptance of participation by the directors, the link was requested to be sent by email to all teachers. Additionally, the director placed the link to fill out the questionnaires on the online portal of each group. Teachers were also asked to forward the link to all colleagues under the same conditions. In the evaluation protocol sent, participants were informed about the objectives, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the confidentiality of the data collected.

Data collection took place between the months of August and November 2023, including the sociodemographic questionnaire, which requested the age, gender, and years of profession of the participants. A total of 204 valid questionnaires were collected. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0).

The statistical tests used in data analysis depended on the type of variable analyzed and/or the length of the assumptions for the use of parametric tests. When these assumptions were not verified, non-parametric tests were applied (Marôco, 2021).

3 Results

3.1 Reliability and validity of the scales

The Cronbach’s alpha values allowed us to verify the internal consistency of each instrument, reflecting the reliability and stability of the measurements. The Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70 (α > 0.70) indicate that the items within each scale consistently measure the same construct (Field, 2013). Observing Table 1, all constructs demonstrated acceptable reliability, except for certain dimensions of commitment, which exhibited lower alpha values compared to adaptation studies. These deviations suggest possible contextual differences in how commitment is experienced and reported in this population.

To strengthen the validation process, further analyses beyond Cronbach’s alpha were conducted, such as average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). AVE, a measure of convergent validity, was calculated for each construct, yielding an average value of 0.644, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981a,b). This indicates that, on average, the constructs explain more than 50% of the variance in their observed variables, confirming that the items are highly correlated with their respective latent constructs.

The CR score of 0.90 further confirms that the constructs demonstrate strong internal consistency. CR values above 0.70 signify that the scale is reliable and that the indicators used to measure the latent variables are performing consistently across the sample. The high CR values across constructs underscore the robustness of the measurement model in capturing the intended psychological constructs.

3.1.1 Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

As shown in Table 2, the constructs related to ethical leadership, identified regulation and affective commitment presented the highest mean scores, suggesting that these aspects are more pronounced in the participants’ experiences. In contrast, amotivation and despotic leadership displayed the lowest levels, indicating their lesser prevalence in this context.

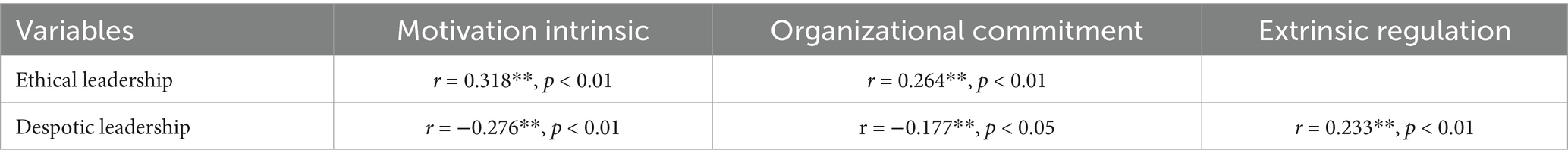

The correlational analysis revealed significant relationships between the core variables of the study. Specifically, ethical leadership was positively correlated with both intrinsic motivation (r = 0.318; p < 0.01) and OC (r = 0.264; p < 0.01). These moderate correlations suggest that higher perceptions of ethical leadership are associated with increased levels of intrinsic motivation and OC. According to Cohen’s criteria (Cohen, 1988), the correlation between ethical leadership and intrinsic motivation represents a moderate effect, indicating that ethical leadership plays a meaningful role in enhancing motivation driven by internal satisfaction and interest.

The negative correlations between despotic leadership and both OC (r = −0.177; p < 0.05) and intrinsic motivation (r = −0.276; p < 0.01) further support the second hypothesis. Although these relationships are weaker, according to Cohen’s guidelines, the significant results indicate that despotic leadership undermines both commitment and motivation, likely due to its coercive and controlling nature. These findings align with previous studies that emphasize the detrimental impact of despotic leadership styles on employee wellbeing and engagement (Hoogh et al., 2008).

The positive correlation between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation (r = 0.233; p < 0.01) reflects that while despotic leadership may reduce intrinsic motivation, it can increase extrinsic motivation. This aligns with SDT, which posits that controlling leadership strategies may foster behaviors motivated by external rewards or avoidance of punishment (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

3.1.2 Regression analysis: ethical leadership as a predictor of motivation and commitment

In order to more rigorously test the hypothesized relationships, multiple regression analyses were conducted. The third hypothesis, which posited that ethical leadership is a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation and OC, was supported by the data, and the results revealed the following:

Ethical leadership was found to be a significant predictor of OC (β = 0.22, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), indicating that leaders perceived as ethical foster stronger emotional attachment and loyalty toward the organization.

Commitment was also a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation (β = 0.22, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01), suggesting that committed individuals are more likely to be intrinsically motivated, driven by personal interest and satisfaction, rather than external rewards.

Directly, ethical leadership was a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation (β = 0.36, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), supporting the idea that ethical leadership can enhance motivation by fostering an environment where employees feel valued, respected, and empowered.

The mediation model showed that, after controlling for OC as a mediator, the effect of ethical leadership on intrinsic motivation decreased from β = 0.36 to β = 0.31 (SE = 0.08, p < 0.001), consistent with partial mediation. This indicates that while ethical leadership has a direct impact on intrinsic motivation, part of its effect is channeled through the influence of OC.

The overall model explained 12% of the variance in intrinsic motivation (AdjR2 = 0.12, F(2, 201) = 14.45, p < 0.001). Although this may seem modest, it represents a meaningful portion of the variance, as intrinsic motivation is a complex construct influenced by multiple factors. According to Cohen et al.’s (2003) effect size guidelines, this can be considered a moderate effect, providing strong evidence that ethical leadership plays a key role in enhancing intrinsic motivation through its impact on OC.

A post-hoc power analysis further confirmed the adequacy of the sample size, with a power level of 0.95. This indicates that the study had a 95% chance of detecting the effects of ethical leadership on intrinsic motivation, providing strong confidence in the robustness of the results.

3.1.3 Testing for mediation: despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation

To test the fourth hypothesis, which explored whether OC mediates the relationship between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation, another set of regression analyses was conducted. Although despotic leadership was found to be a significant predictor of OC (β = −0.13, SE = 0.05, p < 0.05), commitment did not fully mediate the relationship between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation.

Despotic leadership remained a significant predictor of extrinsic regulation even after controlling for OC (β = 0.30, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001). This suggests that while despotic leadership weakens OC, it directly encourages behavior motivated by external rewards or avoidance of punishment, consistent with SDT’s conceptualization of extrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

The model explained 8% of the variance in extrinsic regulation (AdjR2 = 0.08, F(2,201) = 9.88, p < 0.001), with the effect size considered small according to Cohen’s guidelines (Cohen et al., 2003). This small effect reflects the complexity of extrinsic regulation, which may be influenced by a variety of factors beyond leadership style.

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study aims to explore the relationships between ethical leadership, OC, and intrinsic motivation within an educational context. The findings suggest that ethical leadership significantly enhances both intrinsic motivation and OC among educational staff, highlighting the importance of ethical practices in fostering positive outcomes in schools. This aligns with the existing literature on the role of ethical leadership (Hartog et al., 2009; Yukl et al., 2011), indicating that ethical leadership not only promotes a supportive environment but also contributes to teachers’ emotional investment in their roles.

4.1 Reliability and validity of the scales

The Cronbach’s alpha values confirmed the internal consistency of each instrument, reflecting the reliability and stability of the measurements. Values above 0.70 (α > 0.70) indicate that the items within each scale consistently measure the same construct (Field, 2013). In observing the results, all constructs demonstrated acceptable reliability, except for certain dimensions of commitment, which exhibited lower alpha values than adaptation studies. These deviations suggest contextual differences in how commitment is experienced and reported within this population.

Additional analyses, such as AVE and CR, were performed to validate the scales further. The AVE for the constructs was calculated to be 0.644, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981a,b), indicating that the constructs explain more than 50% of the variance in their observed variables. The CR score of 0.90 confirms that the constructs demonstrate strong internal consistency, highlighting the robustness of the measurement model in capturing the intended psychological constructs.

4.2 Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

As shown in the descriptive statistics, the constructs related to ethical leadership, identified regulation, and affective commitment presented the highest mean scores, suggesting that these aspects are more pronounced in the participants’ experiences. In contrast, amotivation and despotic leadership displayed the lowest levels, indicating their lesser prevalence in this context.

The correlational analysis revealed significant relationships between the core variables of the study. Ethical leadership was positively correlated with both intrinsic motivation (r = 0.318; p < 0.01) and OC (r = 0.264; p < 0.01), indicating that higher perceptions of ethical leadership are associated with increased levels of intrinsic motivation and OC. According to Cohen’s criteria (Cohen, 1988), these correlations reflect meaningful effects, emphasizing the role of ethical leadership in enhancing motivation driven by internal satisfaction and interest.

Conversely, the negative correlations between despotic leadership and both OC (r = −0.177; p < 0.05) and intrinsic motivation (r = −0.276; p < 0.01) support the hypothesis that despotic leadership undermines commitment and motivation. These findings align with existing literature highlighting the detrimental impact of despotic leadership styles on employee wellbeing and engagement (Hoogh et al., 2008). Additionally, the positive correlation between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation (r = 0.233; p < 0.01) suggests that while it may reduce intrinsic motivation, it can simultaneously increase behaviors motivated by external rewards.

4.3 Regression analysis: ethical leadership as a predictor of motivation and commitment

To rigorously test the hypothesized relationships, multiple regression analyses were conducted. The third hypothesis posited that ethical leadership is a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation and OC. The results confirmed this, with ethical leadership emerging as a significant predictor of OC (β = 0.22, SE = 0.06; p < 0.001) and intrinsic motivation (β = 0.36, SE = 0.07; p < 0.001). Additionally, commitment was identified as a significant predictor of intrinsic motivation (β = 0.22, SE = 0.09; p < 0.01). The mediation model indicated that the effect of ethical leadership on intrinsic motivation decreased from β = 0.36 to β = 0.31 when controlling for OC, reflecting partial mediation.

The overall model explained 12% of the variance in intrinsic motivation (AdjR2 = 0.12, F(2, 201) = 14.45, p < 0.001). Although this may seem modest, it represents a meaningful portion of the variance, highlighting the complexity of intrinsic motivation. A post-hoc power analysis confirmed the adequacy of the sample size, revealing a power level of 0.95, indicating strong confidence in the robustness of the results.

4.4 Testing for mediation: despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation

The fourth hypothesis examined whether OC mediates the relationship between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation. The analyses indicated that despotic leadership is a significant predictor of OC (β = −0.13, SE = 0.05; p < 0.05) but did not fully mediate the relationship between despotic leadership and extrinsic regulation. Despotic leadership remained a significant predictor of extrinsic regulation even after controlling for OC (β = 0.30, SE = 0.08; p < 0.001). This suggests that while despotic leadership weakens OC, it directly encourages behaviors motivated by external rewards, consistent with SDT (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

The model explained 8% of the variance in extrinsic regulation (AdjR2 = 0.08, F(2, 201) = 9.88, p < 0.001), reflecting the complexity of extrinsic regulation, which may be influenced by various factors beyond leadership style.

Overall, this research indicates that school leaders can increase teachers’ motivation and commitment by adopting ethical leadership practices and fostering a positive organizational climate. As a result, this study serves as a significant contribution to the literature on leadership in educational contexts, particularly regarding the ethical dimensions of leadership. It highlights the need for future research that examines the relationships between ethical leadership, commitment, and motivation in diverse educational settings, especially in the Portuguese context, where empirical studies on these variables remain limited. Investigating differences in perceptions between principals and non-principal teachers could also yield valuable insights into the dynamics of ethical leadership in schools.

Ultimately, this study represents an important contribution to the discourse on leadership within educational settings, particularly concerning the ethical dimension of leadership. It emphasizes the need for future research that explores the relationships between ethical leadership, commitment, and motivation in various educational contexts, particularly in Portugal, where empirical studies on these variables remain limited. Investigating the differences in perceptions between principals and non-principal teachers could provide deeper insights into the complexities of ethical leadership and its impact on educational dynamics, revealing distinct challenges and opportunities for school leaders.

4.5 Limitations

This study is limited by its focus on a specific educational context, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other settings, particularly outside of Portugal. Additionally, while it emphasizes the ethical dimension of leadership, it does not fully account for other influencing factors, such as cultural, socioeconomic, or political variables, that might also shape leadership behaviors and perceptions in schools. The reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias, as participants could be influenced by social desirability or personal experiences when responding to questions regarding leadership practices.

5 Future research directions

Future research should expand the investigation into the relationship between ethical leadership, commitment, and motivation across different educational contexts and cultures. Specifically, exploring these variables in diverse geographic regions within and outside of Portugal could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how ethical leadership functions in varying educational environments. Moreover, comparing the perceptions of ethical leadership between principals and non-principal teachers, as well as other stakeholders, such as students and parents, could uncover nuanced insights into how leadership is experienced across different levels of the educational system. Additionally, longitudinal studies could be conducted to observe how ethical leadership evolves over time and how it influences school outcomes in the long term.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the contribution of Joaquim Luis Coimbra from the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Oporto.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

SDT, Self-Determination Theory; TC, Teacher Commitment; OC, Organizational Commitment; ELQ, Ethical Leadership Questionnaire; MWMS, Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale; OCAS, Organizational Commitment Assessment Scale; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

References

Araşkal, S., and Kilinç, A. Ç. (2019). Investigating the factors affecting teacher leadership: a qualitative study. Educ. Adm. 25, 419–468.

Bass, B., and Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Adm. Quart. 17, 112–121.

Bass, B. M., and Bass, R. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: theory, research & managerial applications. 4th Edn. New York: Free Press, 1536 isbn:978-0743215527.

Bizarria, F. P., Barbosa, F. L. S., Moreira, M. Z., and Neto, A. R. (2018). Análise estrutural de relações entre Motivação, Satisfação e Sugestões Criativas. Base Revista de Administração e Contabilidade da Unisinos 15. doi: 10.4013/base.2018.152.01

Blackmore, J. (2004). Restructuring educational leadership in changing contexts: a local/global account of restructuring in Australia. J. Educ. Change 5, 267–288. doi: 10.1023/B:JEDU.0000041044.62626.99

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., and Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Proc. 97, 117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Carvalho, L. M. (2016). “Políticas educativas e governação das escolas” in Professores e escola: conhecimento, formação e ação. eds. J. Machado and J. M. Alves (Porto: Universidade Católica Editora Porto), 8–30.

Castanheira, P., and Costa, J. A. (2011). In search of transformational leadership: a (Meta) analysis focused on the Portuguese reality. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 15, 2012–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.045

Choi, S., Tran, T. B. H., and Park, B. I. (2015). Inclusive leadership and work engagement: mediating roles of affective organizational commitment and creativity. Soc. Behav. Personal. 43, 931–943. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.6.931

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J., et al. (2003). E-book (536 p.)). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Costa, J. A., Figueiredo, S., and Castanheira, P. (2013). Liderança educacional em Portugal: Meta-análise sobre produção científica. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Educacional.

Cumlat, J., Galat, M., Julian, F. P., and Abun, D. (2023). Developing employees’ Trust in Management through ethical leadership. Divine Word Int. J. Manag. Human. 2, 552–565. doi: 10.62025/dwijmh.v2i4.45

Cunha, K. F., Ribeiro, C., and Ribeiro, P. (2021). Comprometimento organizacional: perspetivas atuais e tendências futuras. Gestão e Desenvolvimento, Viseu 29, 223–244.

Day, D. V. (2001). Leadership development: A review in context. The Leadership Quarterly, 11, 581–613. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00061-8

Day, C., Flores, M., Viana, I., and Viana, I. (2007). Effects of national policies on teachers' sense of professionalism: findings from an empirical study in Portugal and in England. Europ. J. Teach. Educ. 30, 249–265. doi: 10.1080/02619760701486092

Demirtas, O., and Akdogan, A. A. (2014). The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 130, 59–67. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2196-6

Esteves, Z., Formosinho, J., and Machado, J. (2016). “Os coordenadores de ano como gestores pedagógicos” in Professores e escola: conhecimento, formação e ação. eds. J. Machado and J. M. Alves (Porto: Universidade Católica Editora Porto), 171–178.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using Ibm Spss statistics. London: Sage, 916 isbn:9781526445780.

Flores, M. A. (2016). “Políticas educativas e governação das escolas” in Professores e escola: conhecimento, formação e ação. eds. J. Machado and J. M. Alves (Porto: Universidade Católica Editora Porto), 31–54.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F., (1981a). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res. 18, 382. doi: 10.2307/3150980

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F., (1981b). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 18, 39. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Franco, J., Sousa, P., and Sá, S. (2022). “Liderança e inovação educativa” in Revista Multidisciplinar Humanidades e Tecnologias, vol. 38 (Paracatu, MG: Finom), 108–135.

Franco, N., and Silva, R. (2022). The impact of leadership styles on employee performance and job satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 2345–2356. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.234567

Frost, D. (2012). From professional development to system change: teacher leadership and innovation. Prof. Dev. Educ. 38, 205–227. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2012.657861

Gagné, M., Forest, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Crevier-Braud, L., van den Broeck, A., Aspeli, A. K., et al. (2014). The multidimensional work motivation scale: validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. Europ. J. Work Org. Psychol. 24, 178–196. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892

Getahun, T., Tefera, B., Ferede,, and Burichew, A. H. (2016). Teacher’s job satisfaction and its relationship with organizational commitment in ethiopian primary schools: focus on primary schools of Bonga town. Europ. Sci. J. 12:380. doi: 10.19044/esj.2016.v12n13p380

Gil, P., and Machado, J. (2016). “Ousar ensaiar: O que acontece quando se associam diretores de turma” in Professores e escola: conhecimento, formação e ação. eds. J. Machado and J. M. Alves (Porto: Universidade Católica Editora Porto), 157–170.

Graça da Costa, M., Sachionga, S. M., Canganjo, L. H., and Enoque, F. Z. (2024). Fatores que infuenciam o bem-estar e o mal-estar dos alunos e professores: um olhar para seu impacto no processo de ensino e aprendizagem. Recima21 Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 5:e514832. doi: 10.47820/recima21.v5i1.4832

Hartog, D., Deanne, N., Hoogh, D., and Annebel, H. B. (2009). Empowering behaviour and leader fairness and integrity: studying perceptions of ethical leader behaviour from a levels-of-analysis perspective. Europ. J. Work Org. Psych. 18, 199–230. doi: 10.1080/13594320802362688

Hoogh, D., Annebel, H. B., Hartog, D., and Deanne, N. (2008). Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader's social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates' optimism: a multi-method study. Leaders. Quart. 19, 297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.03.002

Howell, J. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1992). The ethics of charismatic leadership: Submission or liberation? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 6, 43–54. doi: 10.5465/ame.1992.4274395

Jacobs, J., Gordon, S. P., and Solis, R. (2016). Critical issues in teacher leadership. J. School Leader. 26, 374–406. doi: 10.1177/105268461602600301

Latham, G. P., and Pinder, C. C. (2005). Work motivation theory and research at the Dawn of the twenty-first century. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 56, 485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142105

Leithwood, K. (2022). “Building productive relationships with families and communities: a priority for leaders to improve equity in their schools” in Relational aspects of parental involvement to support educational outcomes: Parental communication, expectations, and participation for student success. ed. W. Jeynes (New York, NY: Routledge), 244–263.

Lyndon, S., and Rawat, P. S. (2015). Effect of leadership on organizational commitment. Indian J. Indust. Relat. 51, 97–108.

Mahmoud, E., Belbase, S., and Alsheikh, N. (2023). Academic chairs’ leaderships styles and teachers’ job satisfaction in higher education institutions in Uae. Europ. J. Educ. Manag 6-2023, 119–134. doi: 10.12973/eujem.6.2.119

Marôco, J. (2021). Análise Estatística com o Spss statistics. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo, 1022 isbn:9789899676374.

Meyer, J. P. , and Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev, 1, 61–89. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., and Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York: Academic Press, 253 p.

Muijs, D., and Harris, A. (2006). Teacher led school improvement: teacher leadership in the UK. Teach. Teach. Educ. 22, 961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.010

Nascimento, J., Luís,, Lopes, A., and Salgueiro, M. D. F. (2008). Estudo sobre a validação do “Modelo de Comportamento Organizacional” de Meyer e Allen para o contexto português. Comportamento organizacional e gestão 14, 115–133.

Neves, L. Escala multidimensional de motivação no trabalho, versão portuguesa: Estudo de validação em contexto educativo. Revista Paidéia, v.28, (2018).

Neves, P. (2018). Validação da escala de motivação no trabalho MWMS. Paideia (Ribeirão Preto), 28, e2832. doi: 10.1590/1982-4327e2832

Neves, M. D. L. G., Jordão, F., Pina, M., Vieira, D. A., and Coimbra, J. L. (2016). Estudo de adaptação e validação de uma escala de perceção de liderança ética para líderes portugueses. Análise Psicológica 34, 165–176. doi: 10.14417/ap.1028

Rego, A., and Braga, J. (2017). Ética para Engenheiros. 4th Edn. Lisboa: Lidel, 272 isbn:978-989-752-263-5.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. . Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, Richard M., and Deci, Edward L. Self-determination theory. In: Richard M Ryan . (ed.). Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Edward L. Deci . New York, NY: Guilford Press, (2017). p. 3–25. Isbn 9781462538966.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2022). “Self-determination theory” in Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. ed. F. Maggino (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–7. isbn:9783319699097

Xiao, J., and Wilkins, S. (2015). The effects of lecturer commitment on student perceptions of teaching quality and student satisfaction in chinese higher education. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 37, 98–110. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2014.992092

York-Barr, J., and Duke, K. (2022). Leadership in education: insights from recent research. Rev. Educ. Res. 92, 122–185.

Yukl, G., Gordon, A., and Taber, T. (2002). A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: integrating a half century of behavior research. J. Leader. Org. Stud. 9, 15–32. doi: 10.1177/107179190200900102

Keywords: leadership, commitment, motivation, teachers, ethical

Citation: Neves MLG (2025) The relationship between ethical leadership, teacher motivation, and commitment in public schools in Portugal. Front. Educ. 9:1456685. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1456685

Edited by:

José Matias Alves, Faculdade de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, PortugalReviewed by:

María Teresa De La Garza Carranza, Tecnológico Nacional de México, MexicoCristina Corina Bentea, Dunarea de Jos University, Romania

Teresa Sarmento, University of Minho, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Neves. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria de Lurdes Gomes Neves, bWFyaWEubmV2ZXNAaXNnLnB0

Maria de Lurdes Gomes Neves

Maria de Lurdes Gomes Neves