- 1Department of Educational Work, University of Borås, Borås, Sweden

- 2Department of Educational Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

- 3Institute for Teaching and Learning Innovation, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

This configurative review explores how nurturing and enacting a community-oriented praxis (COP) in teacher education can enhance teacher candidates’ preparedness for teaching roles whilst addressing some broader educational and societal concerns. Here, CoP is defined as practices that consider, connect with, and draw on local community strengths, needs, and aspirations for the good of individuals, communities, and society more broadly. We review 31 cases in 37 articles on explicitly community-oriented teacher education (COTE) initiatives from nine country contexts where teacher educators, school-based mentors, and members of local communities collaboratively facilitate the learning experiences of participants in teacher education (i.e., teacher candidates). An analysis of the motivations, processes, and outcomes of the initiatives in the COTE cases highlights benefits such as developing teacher candidates’ pedagogical content knowledge and research competence; fostering social justice consciousness and critical action; and facilitating the sustainable recruitment and retention of teachers especially in marginalised contexts. Implications and possible directions for teacher education are discussed.

1 Introduction

Initial and in-service teacher education as well as continuous professional development (henceforth collectively referred to as teacher education) help develop teachers’ attributes (knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions) for doing their work in schools and society (Zeichner and Flessner, 2009). Because schools (for which teachers are prepared) are situated in local communities, what happens in the schools and the communities is mutually impacting (Ladberg, 1994). Therefore, teacher education arguably has a responsibility to nurture among teacher candidates the attributes needed to effectively engage with the conditions and possibilities in local contexts in which they (will) work and where their (future) students live and develop.

In another logic, however, there is an overly increasing push for teaching to meet standards externally set by national and international actors (Darji and Lang-Wojtasik, 2014), with little, or at the expense of, attention to the local (Paine and Zeichner, 2012). Levinsson and Foran (2020) argue, and we agree, that in this neoliberal turn,

“Teacher education and public-school teaching have shifted from building a practice on relational encounters with pupils in order to help them grow—and in hope of forming a better world—to that of being a manager directing narrow and decontextualized learning services, largely controlled by others, to produce measurable outcomes that are high currency at the competitive school market” (p. 2).

Such decontextualization of learning and usurpation of teachers’ professional autonomy to judge and attend to the conditions before them has detrimental effects for teaching and teacher education (Levinsson et al., 2020). The decontextualization potentially deprives teachers of an adequate understanding of and opportunities for engaging in the life of the local communities in which their students live, grow, and develop, making them less equipped to adequately facilitate students’ learning and, in some cases, contribute meaningfully to broader societal development (Smith and Sobel, 2010). The usurpation of teachers’ professional autonomy renders them largely “cogs in a wheel” to meet standardised goals which are often irrelevant or do not address the most pressing needs of their students, schools, and local communities (Bedamatta, 2014).

Focusing on the unique set up and conditions of local communities “draws our attention to something fundamental, namely the quality of people’s lives as they are lived” (Giddens and Sutton, 2014, p. 238, emphasis in the original). It enables us to see how societal structures, social relations, and other such phenomena are experienced by and affect those involved and implicated. For students, for example, identity aspects such as religion, race, socioeconomic background – and the social system and perspectives around them within their school and community – shape the learning and development needed and possible in the contexts they inhabit (Hallinger and Leithwood, 1998; Peele-Eady and Moje, 2020). Over time, research has demonstrated the benefit of experiential learning (Dewey, 1997; Kolb, 2014), and the richness of one’s immediate environment (including people places, and ecosystems) as a resource for and source of learning. Simultaneously, a student’s individual attributes and community affiliations—identity and belonging—shape how they experience learning and development phenomena in school and local communities (Arthur and Bailey, 2000).

For teachers, “school culture, community demographics, the support systems available… and many others” (Harris et al., 2019, p. 1) constitute and shape their daily experiences of the profession (Rosenholtz and Simpson, 1990; Borrelli et al., 2014). These have a strong bearing on whether teachers want to remain in the teaching profession (Stinebrickner, 1998; McCreight, 2000; Feng, 2005), or in their current workplace (Kelly, 2004; Feng, 2014; Djonko-Moore, 2016). Teacher mobility decisions based on the area of placement disproportionately disadvantage “territorially stigmatised areas” (Beach, 2018) such as highly cosmopolitan urban schools (Freedman and Appleman, 2008; Papay et al., 2017) and very rural and remote settings (Malloy and Allen, 2007; Kaden et al., 2016). Experience (Towers and Maguire, 2017) and research (Papay et al., 2017) have demonstrated that “in urban areas, the cost of living and increased job opportunities mean that teaching may be less desirable, and rural areas struggle to attract teachers because of location and lack of resources” (Thompson, 2021, p. 6). That World Teachers Day 2023 was themed, the teachers we want for the education we need: the global imperatives to reverse the teacher shortage (UNESCO, 2023), is testimony to both the shortage and turnover of teachers today. As local conditions have been cited among the most influential factors for teacher attrition (Thompson, 2021), preparing teacher candidates for the local conditions in and around their (prospective) schools and local communities could address the challenge (Roberts, 2004), at least in part.

The involvement of local communities can also shape how well education institutions are run (Foskett, 1992). Engagement with stakeholders as individuals, groups, and institutions strengthens democratic participation (Hanford, 1992). Attention to socioeconomic and political issues existent in the local context affords space for mutual understanding and for addressing matters of concern (Baquedano-López et al., 2013). This can be a basis for addressing the needs, challenges, and aspirations of individuals and groups based on how they experience educational and social phenomena.

Even with today’s overbearing standardisation demands (Arum, 2000), therefore, there is value in taking seriously the local community conditions in education. Teacher education has a strong role to play in preparing teacher candidates in line with these considerations (Tabachnick and Zeichner, 1993; Ukpokodu, 2007; Yuan, 2018). Indeed, there are examples of teacher education arrangements aimed at fulfilling this role. But because these arrangements are diverse and context-specific, an overview of their contributions and lessons for teacher education more broadly is warranted. This paper examines the aims, processes, and outcomes of exemplar cases from nine country contexts, and draws conclusions and implications for teacher education.

2 Orienting teacher education in local communities: a debate and some exemplar approaches

Orienting teacher education towards local community conditions, needs, and aspirations has been advocated, implemented and studied by educational scholars such as Burgess et al. (2022a, 2022b), Popielarz and Galliher (2023), Harfitt and Chow (2020), Walimbwa et al. (2022), Zygmunt et al. (2018), and Zeichner (2016, 2017), among others. These scholars suggest a transformative teacher education approach which prepares

“Community teachers who:

1. See students as members of families and cultural communities;

2. Work to connect their classrooms to community knowledge, community leaders and community organisations;

3. Recognise that schools are political institutions with a multitude of stakeholders;

4. Are able to work with colleagues, families, communities, and culturally responsive classrooms and school environments; and

5. See their role as teachers as part of the broader constellation of work in communities” (Guillen and Zeichner, 2018, p. 142).

The approach “centres the strengths and needs of local people, places, and ecosystems” (Popielarz, 2022, p. 1) in preparing teachers.

This approach, which we refer to as community-oriented teacher education (COTE), is suggested to replace “traditional” and “alternative” pathways into the teaching career (Zeichner and Conklin, 2008), also, respectively, referred to as Teacher Preparation 1.0 and 2.0 in the US context (see Kretchmar and Zeichner, 2016). These two each have a different purpose and knowledge implications for teaching and teacher education, shortcomings of which could be addressed by embarking on a community-oriented, transformative approach dubbed Teacher preparation 3.0 (Kretchmar and Zeichner, 2016).

According to Zeichner (2016), Teacher Prep 1.0 is the “traditional” approach conducted through higher education courses and school-based practicums. It prioritises enhancing teacher candidates’ knowledge of subject content and teaching skills. The approach has been criticised as too theoretical with too limited classroom practice to enable teacher candidates to facilitate student achievement on curricula demands, and too decontextualised to support societal development. On the other hand, Teacher Prep 2.0 typically takes a “training” approach by employing individuals with subject-based (not professional teacher) qualifications directly in school classrooms while, in many cases, they simultaneously study pedagogical courses towards legitimation as teachers. Teacher Prep 2.0 is criticised for insufficiently engaging teacher candidates in educational theory that would, beforehand, introduce them to the “why” of a teacher identity (Windsor, 2014) and pedagogical actions (Evans, 2010; Harfitt, 2018), such as working for social justice in education (Beach and Bagley, 2012; Bagley and Beach, 2015). This approach is also blamed for perpetuating socioeconomic segregation and injustices in education by intentionally employing inadequately prepared teachers in marginalised schools and communities, often labelled “problem communities” (Zeichner, 2017), despite implementers of this approach seeing it as recruiting to salvage schools in “high-need” communities (Teach for Sweden, 2023) that are suffering from the lack of teachers.

In the advocated Teacher Prep 3.0, herein expressed as COTE, teacher candidates take courses in higher education institutions, undergo school-based practicums, and learn from first-hand experience engagements with local community people, groups, places, and institutions. Proponents of this approach recognise that “learning is a social and cultural process” (Harfitt, 2018, p. 1), and that teachers should support the achievement of the aspirations of students, schools and local communities (Butcher et al., 2003). This implies that teachers’ work involves multiple stakeholders who should all play a role and have a say in the preparation of current and prospective teachers: the teachers themselves, students, school leaders, parents, and other individuals and institutions in the local community within which the educational institutions are situated (Zeichner, 2017). Beyond human actors, some COTE advocates consider community-based resources such as landscapes and ecosystems necessary and integral to teachers’ (and other humans’) wellbeing and experience (McIntyre, 2019; Strom and Martin, 2022), and for experiential learning (Dubel and Sobel, 2014). The call for attention to non-humans is not only for what they can offer humans but also an invitation for humans to take responsibility for planetary wellbeing and justice (Heikkinen et al., 2024). This post-anthropocentric worldview is central to many Indigenous communities’ epistemologies, and offers a valuable perspective for teacher education.

The central concern in this paper is to understand what COTE makes possible to do and achieve in teacher education, and we draw on the concept of affordances to frame the possibilities. We draw on Gibson’s (1979) seminal conceptualisation of an “affordance” as to imply “complementarity” (p. 127) in creating “possibility for action” (Ma and Green, 2021, p. 893) when different actors and factors interact. Here, we relate the notions of “complementarity” and “possibility for action” to the mutual influence and benefit among schools, teacher education institutions, and local community people, places and institutions, and of course practising and aspiring teachers. By the affordances of COTE, therefore, we mean how engaging with local communities enables possibilities for enhancing teacher preparedness to enact pedagogy that is both reflective of and responds to local realities and aspirations.

To delimit the affordances of COTE, we examine the motivations, approaches, and outcomes of exemplar cases. We are cognisant that COTE is inherently context-specific, so there is a wide diversity of designs, practicalities, and possibilities. In a particular context in Hong Kong, for example, Chow and Harfitt (2019) highlight enhanced opportunities for teacher candidates’ academic learning, awareness of societal phenomena, and community connectedness in “community-based experiential learning.” Walimbwa et al. (2022) in Uganda highlight opportunities for practically addressing societal challenges through teacher candidates’ community-oriented projects. Such opportunities and projects include addressing sanitation and hygiene by digging a rubbish disposal pit, addressing period poverty and menstrual health by sewing reusable sanitary pads, and fostering sexual and reproductive health by advocating against female genital mutilation in the Sebei region. There are many more examples from specific contexts, as will be further explicated from the reviewed cases.

While the literature on individual cases illuminates the context-specific initiatives, successes, and lessons, the field of teacher education could benefit from a broader overview across contexts. The current study presents this broader overview by drawing out some common threads from cases from nine country contexts. In examining cases from such a diversity of contexts, we bring together, in a unique way, pedagogical experiences and highlight some key considerations that, we think, will be of interest to educators, researchers, and policymakers. It is hoped that findings inspire further research, practice, and policy initiatives for stronger and more widespread attention to local community conditions in education and teacher education, in an era burdened with national and international standardisation.

3 Theoretical lens: community-oriented praxis

Our theoretical lens is anchored in concerns about how both individuals and collectives are involved in and affected by educational processes. To our agreement, Kemmis (2012) posits that the process (and purpose) of education is to initiate its participants into “forms of understanding, modes of action and ways of relating to one another and the world that foster individual and collective self-expression, individual and collective self-development, and individual and collective self-determination. Education, in these senses, is oriented towards the good for each person and the good for humankind” (p. 84; see also Kemmis et al., 2014, p. 26). We understand, however, that “the good for each person and the good for humankind” can be understood and approached differently in different educational contexts.

The notion of praxis offers a way of theoretically understanding why, how, and with what implications different forms of understanding, modes of action, and ways of relating are or could be developed through teacher education across contexts. Kemmis and Smith (2008) offer an etymology of the concept of praxis that is useful for the current study. They draw on the works of Aristotle (Ethics and Politics), and on critical theory especially the works of Jürgen Habermas. From Aristotle, praxis is presented as one of three kinds of action along with related aims (telos) and dispositions. Theoria, the action of contemplative reasoning aims at seeking “the truth” about the nature of things, and aligns with the disposition of epistemē. This, in contemporary teacher education, could relate to developing an understanding of the epistemological and theoretical bases of certain aspects of education. Poiēsis, the action of making or producing something, entails employing craft knowledges and rules to a task, and aligns with the disposition of technē. This could relate to performing technical skills, for example, of delivering a lesson in a particular subject. Praxis, acting wisely and prudently, aims at doing the most right thing possible in the prevailing circumstances, and is guided by the moral disposition of phronēsis. The moral aspect here concerns thinking about and acting in pursuit of the good for everyone involved and affected by educational phenomena.

There is a distinct contribution of critical theorists such as Habermas to this formulation. Praxis in critical theory invokes transforming prevailing circumstances if they are considered oppressive or they do not permit the desired wise action to happen. At this transformative level, praxis is “critical-emancipatory” action that involves interrogating and acting upon the social, cultural, and economic arrangements that relate to a practice (Kemmis and Grootenboer, 2008, after Habermas, 1972, 1974) or other phenomenon of interest. Enacting such praxis entails being purposefully “informed, reflective, self-consciously moral and political, and oriented towards making positive educational and societal change” (Mahon et al., 2020, p. 15) for individuals and collectives in their particular contexts and situations.

In the current study, we enquire into what intended good inspires orienting teacher education in local communities, how this good is pursued, and what outcomes and implications such pursuits pose for those involved and affected, and for the profession and society generally. We use the term “local community/ies” to mean social systems, including individuals, groups, places, and institutions, situated in a particular context of time and space (Giddens and Sutton, 2014; Lee and Newby, 2012). Community members often have a common interest in a phenomenon (Bradshaw, 2008), and here we focus on education and teacher education.

Drawing on these understandings of praxis and local community, we use the term “community-oriented praxis” (CoP) to refer to practices that consider, connect with, and draw on local community strengths, needs, and aspirations for the good of individuals, communities, and society more broadly; either within or by changing the prevailing conditions. We apply this lens to the cases under review.

This praxis-oriented view of teacher education and its relation to local communities, in combination with an interest in advancing understandings of community-oriented teacher education, have informed the following research questions which guided our review of the selected cases:

1. Why are community-oriented teacher education approaches employed? (motivations)

2. What do community-oriented teacher education approaches entail? (approaches)

3. What outcomes do community-oriented teacher education approaches yield in contexts where they are enacted? (outcomes)

4 Research approach: qualitative configurative review

This study is a qualitative configurative review. Gough et al. (2012) define “configurative” reviews by contrasting them with “aggregative” reviews. A similarity is that both synthesise primary research. But while aggregative reviews are conducted by “adding up (aggregating) and averaging empirical observations to make empirical statements” (p. 3), configurative reviews focus on “interpreting and arranging (configuring) information” (p. 3) to provide new insights into a phenomenon. Further, aggregative reviews aspire to identify and examine exhaustive, representative, and largely homogenous cases of a phenomenon, while configurative reviews aim to draw insights from a diversity of cases (Levinsson and Prøitz, 2017).

Because of the context-specific nature of COTE, we conducted a configurative review in order to draw insights from a wide geographical and sociocultural variation. Our study examines 31 cases reported in 37 peer-reviewed articles reporting on explicitly COTE approaches and practices from nine countries across five continents: Australia, Canada, Colombia, Peru, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, United States of America, and Vietnam.

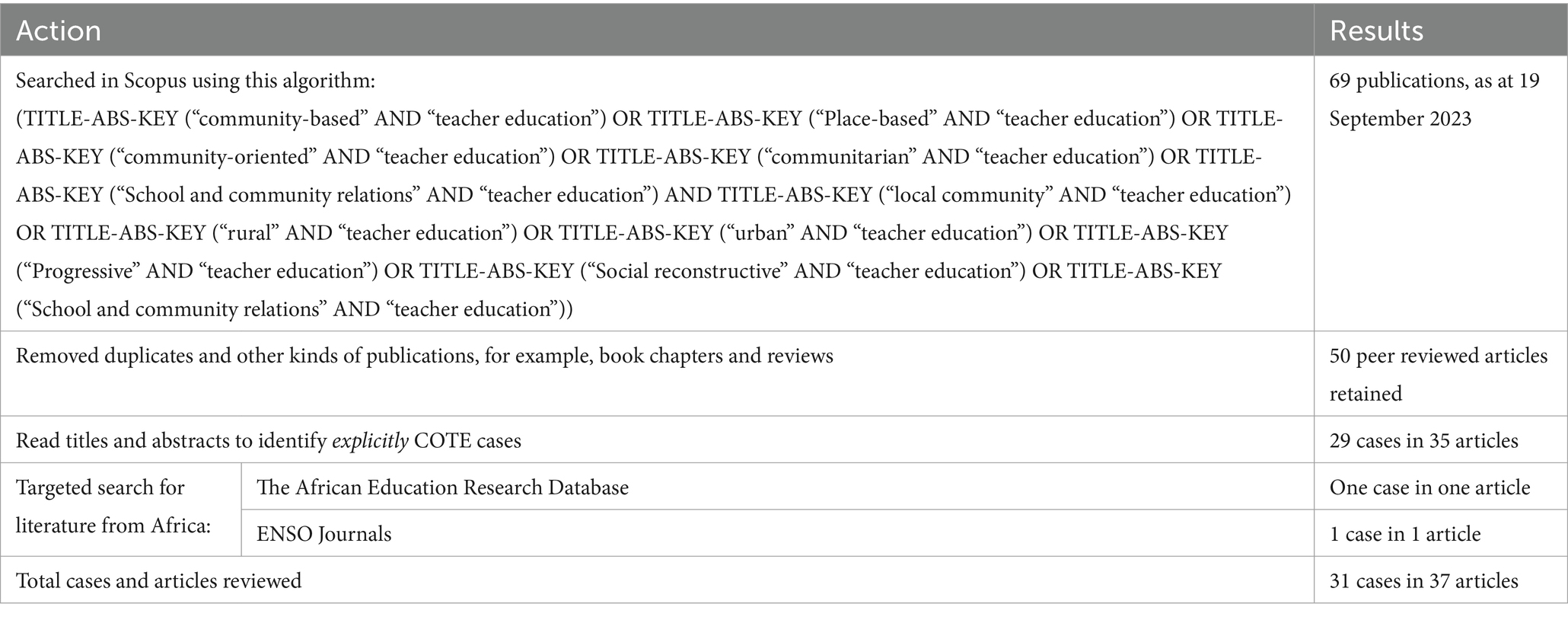

Thirty-five of the 37 articles were identified through a search in Scopus using the algorithm in Table 1. The search returned 69 publications. After removing duplicates and other kinds of publications such as book chapters and reviews, 50 peer-reviewed articles were retained. The abstracts for the 50 articles were then reviewed to identify publications on teacher education approaches that explicitly draw on and/or involve local communities, retaining 35 articles based on 29 cases (because some reported on the same case). However, none of these studies was from an African context, and because the ambition was to vary contexts with at least two studies from each continent, a further search was conducted in the African Education Research Database,1 revealing one Tanzanian case (Kalungwizi et al., 2020); and in ENSO Journals (East African Nature and Science Organisation),2 revealing one Ugandan case (Walimbwa et al., 2022). Therefore, our study includes 31 cases reported in 37 studies.

The cases span initial and in-service teacher education (for teacher candidates) as well as continuous professional development (for practising teachers). Based on an understanding of “teacher learning as an ongoing activity that happens across the career span” (Sharkey et al., 2016, p. 307), all the cases of initial, in-service, and professional development offer valuable insights in the study.

The selected studies were first closely read and thematically analysed by AK using a combination of annotations on each of the articles and targeted notetaking in a matrix with headings aligned with our theoretical lens and reflecting the research questions. The tabulated notes and annotations were then re-examined to identify patterns across the cases and articles, and iteratively revisited and refined in discussion with KM.

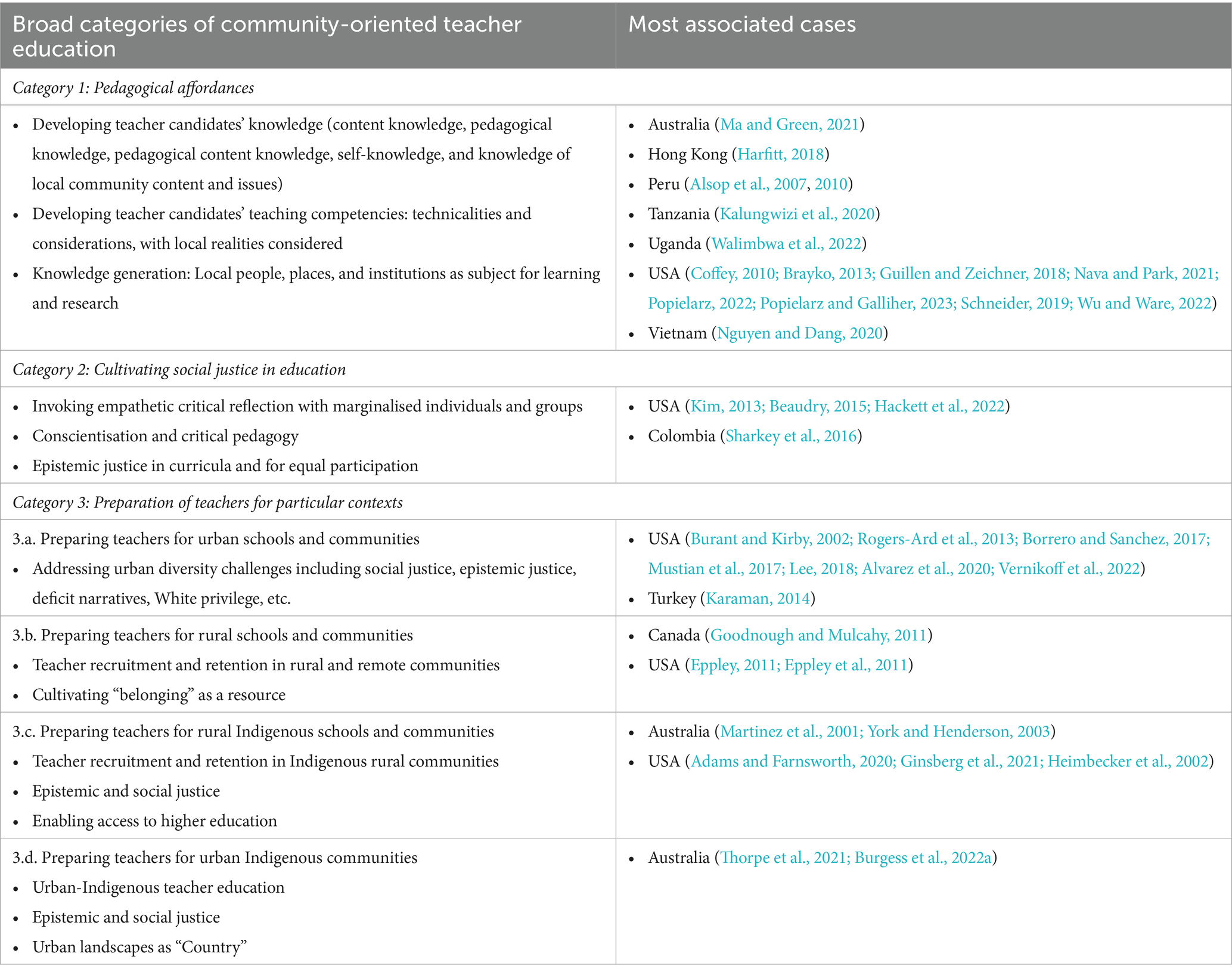

Across the cases, the analysis revealed a wide range of motivations, approaches, and outcomes – affordances, which we reconfigured into three overlapping categories:

(1) pedagogical affordances;

(2) cultivating social justice in education; and

(3) preparing teachers for particular school and community contexts.

Each of the cases falls predominantly (i.e., not exclusively) into one of the three categories in relation to their motivations, what the approaches entailed, and the outcomes highlighted. This is shown in Table 2, where we also summarise the central points that emerged in relation to each category.

Table 2. Three categories of community-oriented teacher education affordances in terms of motivations, approaches, and outcomes.

5 Findings: affordances of COP in teacher education

In the sections that follow, we elaborate the findings based on the three categories outlined above, discussing illustrative cases for each category to exemplify the COTE affordances – motivations, processes, and outcomes.

5.1 Pedagogical affordances of community-oriented approaches

The affordances of community-oriented approaches most evident across the cases relate to the enhancement of teacher candidate learning, especially with respect to developing teacher candidates’ subject and pedagogical knowledge; teaching capabilities and dispositions relevant to their future and ongoing work as teachers; as well as to generating knowledge that is beneficial for teaching, teacher education, and the communities with which they engage.

5.1.1 Developing teacher candidates’ subject and pedagogical knowledge

Many of the cases were grounded in the belief that drawing on local community people, places, and institutions provides opportunities for teacher candidates to engage meaningfully in concrete, authentic experiences (Harfitt and Chow, 2020) that enhance teacher candidates’ knowledge. This includes content or subject knowledge, such as of concepts and processes in mathematics and science (for example, “erosion” and “adaptation” in Ma and Green, 2021); pedagogical knowledge, which entails the ways of facilitating learning (for example, by gaining an understanding of why and how adults might learn English as a second language in Nguyen and Dang, 2020); and “pedagogical content knowledge,” which “represents the blending of content and pedagogy into an understanding of how particular topics, problems, or issues are organised, represented, and adapted to the diverse interests and abilities of learners, and presented for instruction” (Shulman, 2006, p. 127). The cases take as their point of departure an assumption that connections to real life experiences and/or natural environments can forge a stronger connection between teacher candidates’ classroom-based experience and the larger context of the schools and their neighbouring communities (Burant and Kirby, 2002). In keeping with this assumption, the approaches typically include an introduction to the topics in focus, but learning is largely experiential in nature with first-hand and sensory experiences in and/or with local communities.

One example is the place-based pedagogy case reported in Ma and Green (2021). The authors describe a course in which teacher candidates learn and teach science in two environments: a wetland and a school ground. The course starts with an introductory lecture on Margaret J. Somerville’s place pedagogy framework which posits that, “our relationship to place is constituted in stories and other representation; place is embodied and local; and deep place learning occurs within a contact zone of multiple contested stories” (Somerville, 2010, p. 326; Ma and Green, 2021, p. 894). This is followed by a presentation on inquiry-based learning (IBL) by teachers from the school sites that the teacher candidates will later visit. The candidates would later use IBL with school pupils when they visit the school sites and local wetland. Before engaging with pupils in actual lessons, the teacher candidates, along with teacher educators and in-service teachers, conduct reconnaissance visits to the wetland and playground. This supports enhancement of their subject knowledge [for example, science concepts such as “adaptation” in the wetlands and “push and pull, gravity, erosion, bugs and insects” (p. 895)], and informs their lesson planning. The sessions with pupils provide opportunities for them to reflect on the pedagogical implications of place-based learning processes, and place-related storylines, and cultural contact zones and embodiments (such as what students “become” and how they behave in playgrounds and swamps with which they are familiar and associate).

This case, like several others reviewed, highlights how local places and communities can become both a resource and authentic context for teacher candidate learning, and how engaging with such places and people can expand the candidates’ ways of understanding social and educational phenomena, thereby expanding their epistemic horizons.

5.1.2 Developing teacher candidates’ teaching capabilities and particular dispositions

Some of the cases reflect a motivation to ensure that teacher candidates develop certain skills and dispositions. Skills apparently deemed important include planning and implementing learning activities (for example, Kalungwizi et al., 2020; Nava and Park, 2021), collaborating with stakeholders including the community (Chow and Harfitt, 2019), and dispositions and skills needed for the smooth running of school and community systems (such as enabling parent participation in meetings by taking care of their children, in Burant and Kirby, 2002). Among the nurtured dispositions are adaptability, reflectivity in relation to one’s own practice, criticality, respectfulness, and agency (Chow and Harfitt, 2019). Again, experiential approaches seem to be commonly employed in the cases to nurture such skills and dispositions.

The Tanzanian case expounded by Kalungwizi et al. (2020) is a relevant example. The case involves a community-oriented approach to environmental education. The approach is motivated by a desire to address what is perceived by the authors to be insufficient preparation of teacher candidates to teach environmental education (EE) topics in both their practice (or practicum) schools and in their future jobs as teachers. Rejecting teacher education approaches oriented “towards lecturing and learning by memorising” (p. 96), they facilitate collaboration between teacher candidates, primary school teachers, and community actors—a local gardener and a local (agricultural) extension officer. What starts as a tree planting project expands to broader environmental education and climate action activities such as tree planting, tree care, and ocean cleaning; involving more members of local communities and addressing the needs in their respective contexts. This collaboration is viewed as important for fostering teacher candidate preparedness because it triggers them to reflect on the particular contexts of their work, such as teaching about and rallying community action for ocean cleaning to curb cholera in Zanzibar. Their new approach reportedly leads to the transformation of teacher candidate competencies regarding the ability to “(analyse) the local environment of the college and the surrounding local communities” and “plan and implement experiential teaching lessons” (p. 103), as well as facilitate problem solving in initiatives based on diverse school and local community experiences.

This case demonstrates that connecting with local communities has the potential to nurture a range of skills and dispositions in ways that might not be possible away from the concrete realities of teacher candidates’ professional or soon-to-be professional contexts. Concrete experiences in community (with real students, real parents, and real principals and teachers, etc.) allow the candidates to test ideas, practise skills, and act on learnings, and more importantly, receive immediate feedback and reflect on that feedback as their practice unfolds in real time and space, especially during collaborations and reflective activities. The complexities of situations and consequences of their judgements and actions are so much more apparent than in a university classroom.

5.1.3 Generating knowledge

Through their community-oriented approach, some of the reviewed cases aimed to simultaneously enhance teacher candidates’ understanding of community contexts and generate knowledge of value to education, local communities, and society more broadly. These cases typically involve inquiry-based learning with a service learning component (for example, through action research projects) where teacher candidates draw on community resources to (a) understand and generate knowledge about phenomena relating to their work, such as students’ backgrounds (Delvin et al., 2012), and (b) contribute to addressing the educational implications of those phenomena (Alsop et al., 2007).

An illustrative case is a second language teacher education (SLTE) course in Nguyen and Dang (2020), Vietnam. Motivated to overcome the limitations of overly focusing on cognitive aspects in language teaching, the authors explore a sociocultural approach that anchors SLTE in the needs of local community members. One societal condition that shapes the direction of course activities is the difficulty for teachers to gain employment in mainstream government schools, necessitating teaching private learners or in private institutions. Thus, the authors challenged their student teachers to imagine their career prospects after graduation, and what their future students’ needs will possibly be. Given the aspiration for adults in Central City (pseudonym) to learn English in order to position themselves for jobs, the teacher candidates move around their city in groups of 5 or 6 to “investigate the needs of learning English in local communities” (p. 411). They meet with nine groups of workers with diverse reasons for learning the English language. “Cyclo riders” learning English for communicating with international visitors/passengers; and “hotel staff” for job promotions are just two examples of the nine groups. The activity both generates knowledge about the English language needs in their local community and prepares the teacher candidates to practically address the needs through second language teaching. An additional benefit was that the insights generated in the activity also pointed the teacher educators involved to some practical ways in which community-oriented learning could work in their university-based SLTE course.

The capacity to research, learn from, and improve their own practice is considered a key teacher attribute (Babkie and Provost, 2004). The cases where teacher candidates enquire into phenomena in their local contexts demonstrate the potential for generating knowledge that can be a basis for enabling praxis, namely by triggering action against untoward experiences and changing the conditions shaping them where necessary. One point to note, however, is that in the inquiry-based learning cases, for example, Nguyen and Dang (2020) and Alsop et al. (2010), teacher candidates’ project reports are not published. Rather we learn about the teacher candidates’ work through the research conducted by the teacher educators. This limits the richness of insights shared. Having a publication platform for the community-based inquiry projects—even those led by teacher candidates—could offer valuable insights for diverse education stakeholders, not least educators, policymakers, and researchers.

To summarise this sub-section, the cases demonstrate that expanding the horizon of teacher education beyond the confines of the university classrooms and school-based practicums enables teacher candidates to experientially explore new and diverse perspectives regarding what knowledge is and can be, both for their own learning and in order to be able to teach. Conducting inquiries also keeps alive teachers’ attention to important influences of local communities on classrooms, schools and student experiences.

5.2 Cultivating social justice in education

Several of the reviewed cases aimed at, and were reportedly effective in cultivating, social justice. By this we mean raising teacher candidates’ awareness about and igniting their willingness and ability to act against untoward conditions that compromise the wellbeing, life opportunities, and progress of some individuals and groups in society. In other words, raising critical consciousness (or conscientisation) and fostering a capacity for critical action.

5.2.1 Conscientisation

Some of the reviewed cases sought to raise the awareness among teacher candidates of histories, conditions, and practices that propagated or perpetuated social injustice that has a bearing on education. A common approach across the cases was exposing teacher candidates to first-hand manifestations of injustices and encouraging the scrutiny of conditions shaping and arising from those injustices through structured reflection.

This outcome is illustrated in the case presented by Hackett et al. (2022) involving a project dubbed Atlanta Schools Critical Education Network for Distinction (ASCEND). The motivation was to raise teachers’ awareness about the education-related sociohistorical dynamics of the US city of Atlanta. Although the city has a majority of people of colour, it also has a long history of politically-sanctioned racial oppression which reduces their opportunities for education and career progression. In ASCEND, teacher educators collaborated with social justice-oriented community-based organisations and local schools to run a series of workshops and community asset mapping excursions to deepen urban teachers’ awareness and attention to the resources and challenges in their community. Concerning the awareness raised, the study reports that,

“The walk was enlightening on multiple levels. On one hand, members identified new community assets, and on the other hand, the walk revealed several racially threatening and violent Confederate symbols. Being near the symbols had a visible impact on our bodies as many participants became emotional as we encountered them and discussed their historical purposes… For years City MS educators passed by these symbols, some unaware of their messaging, but there was a new collective learning as we huddled together to make sense of their placement and purpose” (pp. 16, 17).

The authors comment that teachers who participated in this conscientisation process exhibited a willingness and growing ability to identify and address the marginalisation that people of colour face even in places where they are a majority.

From a praxis perspective, this case demonstrates conscientisation about untoward conditions that can be a springboard for addressing them. Rooted in Freire’s (2000) critical literacy and pedagogy, conscientisation entails questioning the “habits and knowledge that so far were neither questioned, nor even thought about, because they were considered as the way certain things are” (Montero, 2014, p. 297). From such questioning arises increased consciousness about the state of things, which lays the ground for acting upon them, as we discuss next.

5.2.2 Critical action

In some of the cases, firsthand experiences contributed to teacher candidate recognition of marginalised people’s strengths and commitment to using their role as teachers to address identified needs.

The case presented by Kim (2013) demonstrates how exposing teacher candidates to the conditions of the marginalised could trigger social action. In the program described by Kim, early childhood teacher candidates undertook their internship at a learning centre with homeless children. There, the teacher candidates learned about the living conditions of children and their parents, mostly mothers. Initially, many of the teacher candidates stereotypically thought of homeless children as

“‘misbehaved and unfocused’ … ‘dressed poorly’, very behind in their development, lonely, scared, and shy’ … “troubled, misbehaved” (p. 165).

Later, the teacher candidates reported eye-opening moments:

“All of us quickly realised that the children were no different than other children we had met … It became apparent that if we were not playing with these children in the playroom we would not have known they came from poor backgrounds with troubled mothers. They played like other children” (p. 165).

The experience fostered critical action, willingness, and abilities among some teacher candidates. One student, Audra, after realising that some homeless children attend local schools and that there are stereotypes and difficulties that limit their educational experience and prospects, asked her mentor at a local school if the mentor had any homeless children in her class. The mentor, an experienced teacher, was not aware of any, but inquired anyway, discovering two in her class. According to the authors, “these conversations prompted Audra to begin to raise questions about how homeless children have access to school, and how school can support them” (p. 166).

This case illustrates that exposing teacher candidates to the out-of-school conditions in which their students grow up is of great importance regarding what teacher candidates can do in their future work to support students’ learning and development. Programmatically, local community experiences can be a worthwhile practical part of

“Critical social foundations of education that activates civic citizenship of all students, keeps students awake, and encourages them to be active participants in the fight for social change and social justice through social activism such as volunteering, doing charity work, civic missions, political participation, engagement in community affairs, advocacy, debating national policies, and civic values” (Bassey, 2022, p. 101).

5.2.3 Tensions in conscientisation and critical action

While some local community engagements registered positive conscientisation and social action experiences and prospects, others highlighted risks for triggering further marginalisation of the oppressed. In some cases, the experiences were either non-transformational or risked stimulating racial supremacy tendencies.

Guillen and Zeichner (2018) in the US provide an interesting case in point. In a “Community-Teaching Strand” of their teacher education programme, community mentors from nonprofit organisations facilitated some learning sessions on social justice. The mentors largely felt that their knowledge and contributions were respected by the teacher candidates, but in some cases, there were major tensions. For example, after taking a cohort of preservice teachers (76% White and 24% people of colour) through a white privilege reflection activity, mentors Shelly and Jovonna felt that many of the participants remained indifferently uncritical of their White privilege and positionality in relation to their clearly disadvantaged counterparts of colour. This could mean that, if at all, the teacher candidates might not have learned enough from the activity and were likely to reproduce the asymmetrical racial relations that perpetuated sociocultural injustices when they eventually became teachers. However, the study only provides the perspectives of the community mentors. So, it is difficult to discern why the transformation anticipated by the community mentors had not occurred, whether the transformation occurred in a different form than anticipated, or if the teacher candidates’ expressions were interpreted inaccurately. In any case, however, the tensions warrant reflection in similar initiatives.

Despite the tensions, the cases demonstrated that local community engagements afforded teacher candidates at least an opportunity to develop social justice sensitivities and a capacity for critical action. Taking the social justice agenda further, the next section addresses the question of preparing teacher candidates for particular schools and communities, especially those that are “territorially stigmatised” (Beach, 2018).

5.3 Preparing teachers for particular school and community contexts

Several of the reviewed cases recognised that inadequate preparation for the sociocultural conditions of certain contexts undermines the recruitment and retention of teachers in these contexts. Therefore, they aimed to prepare and attract teacher candidates towards working in these contexts. Examples of noteworthy contexts are schools and communities with highly cosmopolitan urban areas, rural and remote places, and places predominantly inhabited by Indigenous peoples. While Indigenous peoples are normatively thought to occupy rural areas, some studies recognised their presence in urban areas and focused on preparing teacher candidates to address the worldviews, needs, and aspirations of urban-based Indigenous peoples.

To prepare teacher candidates for these contexts, some of the community-oriented activities were incorporated into existing programmes and courses while other interventions were specially designed for the purpose, often adopting labels such as “urban teacher education,” Indigenous teacher education’ and “rural teacher education.”

5.3.1 Preparing teachers for urban schools and communities

Our reference to “urban” schools and communities draws on Lee’s (2018) distinction between urban and suburban contexts. In this frame, suburban schools are largely (but not always) high socioeconomical status with typically monocultural populations. In contrast, urban schools are cosmopolitan, with people from diverse ethnic, national, and socioeconomic backgrounds and identities.

The cases aimed at preparing teacher candidates were motivated by an understanding that urban schools often struggle to recruit and retain qualified teachers. Many teachers become overwhelmed by the diversity of worldviews and student behaviour in these contexts, leading to stigmatising labels like “high need” or “problem” schools and/or communities. The cases, therefore, took the approach of bringing teacher candidates in close contact with urban community people, places, and institutions to familiarise them with the conditions and resources in these contexts. The cases demonstrate that such contact debunks some of the deficit stereotypes held by people outside of these communities; and, to the members of the urban communities, brings a sense of self-affirmation that transforms educational experiences.

As an illustrative case, Mustian et al. (2017) at the Illinois State University partnered with community organisers and school-based mentors in territorially marginalised areas of the South Side of Chicago, USA. They aimed to address the dearth of teachers adequately prepared to address urban diversity and epistemic justice issues especially affecting students, teachers, and communities of colour. Thus, they focused on nurturing culturally responsive pedagogy among teacher candidates through service learning and cultural immersion activities, including dialogues with students, teachers, parents, faith leaders, and restorative justice scholars in the community. Their flagship service-learning activity was a Slam Poetry Mentorship project dubbed Revolution of Young Artists as Leaders (ROYAL). The teacher candidates worked with teachers and high school students to mentor elementary and middle school children in poetry that voices the conditions and experiences of living in their urban community, and the poems were later performed at a public event. The motivation for a slum poetry project was that it would serve two purposes simultaneously: expose teacher candidates to the experiences of urban youth; and facilitate socio-emotional wellbeing for the youth as they voiced their experiences, in line with studies by Maddalena (2009) and Ruchti et al. (2016). The project gave the teacher candidates insights into the urban community:

“Poem topics included the urban school system’s lack of regard for what students need; police abuse of authority and power in Black neighborhoods; what it is like to be raised by a single mother; and the effects of bullying on students. After the performances, ROYAL participants (i.e., mentors and mentees) formed a student panel to reflect on their experiences participating in ROYAL and to field questions from university teacher candidates” (p. 472).

The outcomes of the service learning and dialogues were reportedly positive. The authors report that based on pre- and post-surveys,

“Teacher candidates participating in the redesigned course and ROYAL were significantly more prepared to teach students who have culturally different backgrounds from their own, effectively communicate with students, participate in the professional community of the school, and actively engage students in learning. Furthermore, at the end of the course, teacher candidates reported an increased desire to teach in a high-need urban school” (p. 477).

This case demonstrates that familiarisation with urban context resources and conditions can help prepare and raise the willingness of teacher candidates to work in these communities, and to enact culturally-responsive pedagogy that humanises urban populations. Although urban conditions can be challenging even for long-serving teachers (Towers and Maguire, 2017), graduating without adequate preparation poses a high risk of being overwhelmed and quitting too quickly (Lee, 2018). Helping teacher candidates recognise possible resources to draw on can increase their chances of staying longer and more effectively supporting the learning and development of urban students, schools, and local communities.

5.3.2 Preparing teachers for rural schools and communities

In sharp contrast with urban areas, rural and remote schools and populations are typically small and often monocultural, with tight-knit relationships. Not many teacher education institutions are located in rural areas, which means that teacher candidates from urban backgrounds lack familiarity with the conditions and possibilities of living and working in rural areas. This poses recruitment and retention challenges for rural schools. Even for teacher education institutions with a largely rural-dweller teacher candidate population, the uniquely rural dimensions of a teacher’s work come into play, which necessitates deliberately pointing out the resourcefulness of their rural areas, as the case in Eppley et al. (2011) and Eppley et al. (2011) demonstrates. We summarise here a case, Goodnough and Mulcahy (2011), where urban teacher candidates are placed in rural schools.

Goodnough and Mulcahy (2011) from the Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada, examine how rural internships were experienced by teacher candidates who came from urban areas, influenced their teacher identities, and the possibility that they would affect their willingness to teach in rural schools and communities. Their course engages teacher candidates in a 6-week internship, 4 of which they spend teaching in rural and remote schools, in Newfoundland and Labrador, with 32–145 pupils, often in multi-grade classrooms. Three of the 12 schools can only be reached by boat. Working in the schools involves collaborating with members of local communities, whose populations range between 70 and 800 people. Through this experience, the teacher candidates reported getting to know their students and the students’ living conditions more closely than in an earlier urban internship. The candidates commented that their teacher identity and “possible selves” were enriched by, for example, teaching several subjects in multigrade classrooms, and that they gained a stronger sense of purpose when they realised that there were teacher shortages in rural areas. Most teacher candidates, according to the authors, expressed a willingness to consider working in rural areas, with an understanding of both the possibilities and challenges of working in a community where “everyone knows everyone else,” which offers “an authentic sense of community with people working and playing together” (p. 201) on the one hand, but with limited personal privacy on the other.

Exposing teacher candidates to such nuances of rural life could be beneficial in preparing them for working there, but in some cases could deter them too early in their career. As the teacher educators in this case demonstrate, embedding reflections on the experiences can be useful for raising the teacher candidates’ interest.

Both the above sets of cases on urban and rural teacher education raise a salient question about the relational dimension of teacher identity: what it could entail, and how it can be nurtured and enacted in different contexts, in this case rural versus urban. The cases emphasise the need to familiarise teacher candidates with social and resource dynamics that they will likely encounter in their future working contexts.

5.3.3 Responsiveness to rural indigenous community conditions and epistemologies

The cases concerned with the education of Indigenous communities, particularly in rural and remote areas, focused on a twofold challenge: fostering the staffing of schools with qualified, culturally-responsive teachers, and mainstreaming Indigenous knowledge and cultural heritage into curricula. To address these, the cases implemented both structural and pedagogical interventions, often in the same programme. In close collaboration with local communities, targeted programmes and infrastructural adjustments were made to enable Indigenous peoples to participate without moving to urban-based universities. Either special higher education institutions were established (such as the Stone Child College in Montana, USA, in Ginsberg et al., 2021), or satellite instructional centres affiliated to urban-based institutions [such as James Cook University’ Remote Area Teacher Education Programme (RATEP)] in Australia (York and Henderson, 2003) and the Northern Arizona University’s RAISE (Reaching American Indian Special/Elementary Educators) programme in the US (Heimbecker et al., 2002). The pedagogical interventions included engaging with Indigenous representatives (elders, leaders, and other duty-bearers) in experiential learning excursions at cultural heritage sites, and designing programmes targeted at rural Indigenous students who may not be able or wish to attend urban-based institutions, typically because of other commitments and responsibilities in their local communities.

As an illustrative case, RATEP was established in 1990 “to increase the numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers through a teacher education pathway supported by a partnership between TAFE Queensland, James Cook University, and the Queensland Department of Education” (James Cook University, 2023, webpage). Epistemically, the programme “respects the culture and knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and values the contribution they can make to the education of all young Australians” (TAFE Queensland, 2023, webpage). The programme runs multiple instructional centres serving rural and remote communities, including through distance learning. The programme seems to yield good outcomes. Already in 2003, York and Henderson (2003) that 85% of RATEP graduates were still teaching in classrooms, some in specialist roles such as Advisory Teachers to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous teachers. Three graduates had been promoted to Principal and two were School Administrative Officers. Since the programme is still running, one can expect that further progress has been made.

These cases indicate the potential that mainstreaming Indigenous people’s conditions, experiences and epistemologies in teacher education curricula and administrative arrangements could foster both epistemic justice (Austin and Hickey, 2011) and teacher retention in rural Indigenous schools and communities (Hall, 2012).

5.3.4 Working with indigenous communities in urban contexts

Another issue highlighted by the cases is that Indigenous peoples situated in urban contexts are often faced with a sense of invisibility because Indigeneity is normatively associated with rural and remote areas while, in reality, the peoples are not territorially confined (Conrad, 2022). Rather, urban spaces can be conceptualised as “Country” in which Indigenous communities also have a stake and custodianship, and from and in which they can learn (Thorpe et al., 2021). As such, we highlight below an Australian case whose central concern is to equip teachers in urban schools with the cultural sensitivity and pedagogical competence to recognise, respect, and sustain Indigenous cultures and knowledges.

A central idea behind the case discussed in Thorpe et al. (2021) and Burgess et al. (2022a) was that working with Indigenous communities in urban, cosmopolitan contexts could enable teacher education to combat “assimilationist education practices, … misrepresentation and deficit discourses” (Thorpe et al., 2021, p. 57) about Indigenous peoples. Burgess et al. (2022b) were concerned about practices which pay superficial and decontextualised attention to issues of “epistemological and ontological dissonance” as Indigenous teacher education programmes and courses employ “short ‘typical’ lecture/tutorial style teaching often taught by non-Aboriginal lecturers” (p. 927) in their bid to meet the Australian teacher standards. One requirement is to “demonstrate that graduate teachers have developed strategies for teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students (AITSL1 standard 1.4) and understand and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to promote reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (AITSL standard 2.4)” (p. 925). To address this with culturally sustaining pedagogies, a conceptual framework for country-centred teaching and learning was proposed (Burgess et al., 2022b), and a related “Learning from Country in the City” pedagogical project implemented. The framework hinges on four interconnected processes: country-centred relationships, relating[s], critical engagement and mobilising. Engaging in these processes would potentially enable teacher candidates to “[show] ‘respect through deep listening to community voice’; ‘connect to country through truth-telling and nurture belonging’; ‘reflect on country-centred relationships to develop critical consciousness and share knowledge’; and ‘direct through culturally sustaining and nourishing practices’” (Burgess et al., 2022a, p. 156; Burgess et al., 2022b, p. 931).

In the “Learning from Country in the City” project, teacher candidates at an urban university were engaged in Aboriginal community-led learning sessions and excursions (Burgess et al., 2022a). Pre- and post-surveys indicated a high increase in teacher candidates’ knowledge at least on four parameters: “‘understanding Aboriginal cultures, history and communities”; “Impacts of colonisation, the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples’; ‘Confidence/skills to engage with Aboriginal families/communities’; and ‘Culturally responsive curriculum and pedagogy’” (Thorpe et al., 2021, p. 64). The findings suggest that engaging with urban Indigenous peoples in this way sheds light on their presence and resources that can encourage more respectful, responsive and relational engagement with Indigenous peoples in these contexts and beyond.

To summarise, a number of cases illustrate how COTE could help teacher candidates more effectively prepare for the conditions prevalent in marginalised contexts. Fostering an understanding of particular communities could help teacher candidates to both navigate “different worlds” and enact culturally responsive pedagogy. Culturally responsive pedagogy is arguably important for ensuring that all stakeholders feel understood and respected.

6 Discussion

This study is premised on an understanding of teacher education as a praxis-enacting and praxis-nurturing undertaking that initiates teacher candidates into “forms of understanding, modes of action, and ways of relating to one another and the world” (Kemmis et al.’s, 2014, p. 26) geared towards promoting the “good” for those involved in and/or affected by educational processes and outcomes. However, the study also recognises that, across contexts and teacher education arrangements, the kinds of “good” addressed are contentious, and so are the approaches to pursuing them. Therefore, the study started by differentiating three teacher education approaches: “traditional,” “alternative pathways” and “community-oriented.” A “community-oriented praxis in teacher education” seeks to nurture among teacher candidates not only the theory and technical competence for teaching but also the awareness, dispositions, and abilities for addressing contextual factors of education, capitalising on the strengths of and addressing the gaps in “traditional” and “alternative” approaches.

Our application of a praxis lens to 31 cases from nine country contexts revealed motivations to bring about a positive outcome primarily for teacher candidates, their (prospective) students, and the communities. The initiatives were geared towards addressing identified challenges or observed injustices, and towards transforming practices and the conditions shaping them.

The pedagogical concerns addressed in the cases seem to have been triggered by some version of the overarching question, “What do teachers need to learn in order to help all students achieve their potential?” (Grant, 2008, p. 697). Singer et al. (2010) suggest that part of teacher preparation entails learning “to transfer what [and how] they [teacher candidates] learned from their teacher preparation program into becoming a teacher” (p. 120). The cases demonstrate that teachers learned both for themselves and for their prospective teaching (i.e., “pedagogical content knowledge”) (Shulman, 2006) and learning “to be adaptive and reflective to [sic] their own teaching practice and at the same time learn to work with others including the community” (Chow and Harfitt, 2019, p. 2). The people, places, and institutions with which teacher candidates engaged were also a resource for developing their knowledge generation skills.

In regard to social justice, an overarching motivation was to raise among teacher candidates the awareness about, and to ignite the willingness and ability to act against, untoward conditions that compromise the wellbeing, life opportunities, and progress of some individuals and groups in society. The concerns were largely informed by ideas from critical theory that challenge power dynamics and social stratification in education and society. Through a range of community-based activities that would awaken their “civic citizenship” (Bassey, 2022), the teacher candidates were initiated into a tradition of questioning their and others’ conditions and positionality. According to Freire (2000), addressing dehumanisation invites the oppressed to liberate both themselves and their oppressors. This, in the cases, triggered tensions. Although, according to Freire, the burden of liberating oneself and the other is on the oppressed, it would be unbecoming for teacher education to set student groups against one another; in fact, it could be further marginalising of the oppressed. In the cases, an effort was made to bring students in both oppressed and dominant groups to learn together and reflect on their respective conditions and positionality.

A recognition that geographical and demographic characteristics have strong implications for the education and other life prospects proved to be a motivation for focussing on particular contexts – that is, preparing teachers for rural, urban, and Indigenous schools and communities. They drew on research that shows how challenging it is to recruit and retain staff in schools that are multicultural and urban (Freedman and Appleman, 2008; Papay et al., 2017), rural and remote (Roberts, 2004; Green and Nolan, 2011), or largely inhabited by Indigenous peoples (Heimbecker et al., 2002; Hall, 2012). A further impetus was a desire to challenge the normative association of Indigenous peoples with rural areas (for example, Thorpe et al., 2021).

The approaches taken across the cases varied. Despite the variations, the centrality of experience and explicitly buying into the affordances of experiential learning in/with community (Sobel et al., 2011) was a striking feature. However, even the forms of the experience varied widely. They ranged from inquiry-based projects (Alsop et al., 2010; Walimbwa et al., 2022); service learning (Karaman, 2014); experiences in natural environments like swamps and playgrounds (Ma and Green, 2021); excursions led by Indigenous peoples (Burgess et al., 2022a); and placements in rural (Goodnough and Mulcahy, 2011) or urban (Vernikoff et al., 2022) contexts, among others. This diversity of experiences attests to the myriad of possibilities and flexibility that COTE offers, but suggests the need for a holistic frame for understanding what the variety might mean for the different purposes of teacher education. This is a possible direction for further research.

The degree and nature of community engagement also differed, especially regarding the positioning and role of local community actors in the educational activities. Zeichner et al. (2016) suggest a typology for understanding how and with what implications communities can be engaged in education processes. It includes three aspects: community involvement, community engagement, and working in solidarity with community. Involvement is largely teacher-dominated, where “school staff … share their knowledge and expertise with families and community…” (p. 278). Engagement is where teachers and teacher candidates listen to family and community members. Note that both involvement and engagement are one way traffic, respectively leading in either direction between community actors and educators. Working in solidarity with communities entails collaboratively designing and pursuing mutual interests, bringing together the worldviews, needs, and aspirations of all involved. It appears, based on the cases like the RAISE programme in the US (Heimbecker et al., 2002) and RATEP in Australia (York and Henderson, 2003), that working in solidarity with local communities potentially provides the most benefit as it allows for equitable and iterative reflexivity (Zeichner et al., 2016).

We note, however, that although in most of the cases local communities, schools, and teacher education were considered mutually complementing entities, the agenda in the cases were largely initiated by teacher educators. None of the cases explicitly reported on approaches/projects initiated by members of local communities, schools, or teacher candidates. This suggests a need for teacher educators to reflect on, firstly, the balance of power among the stakeholders and, secondly, their own responsiveness to community ideas and concerns. To increase the possibility for the latter, teacher education institutions could proactively create opportunities for community-initiated innovations.

Worth noting, our use of the central term, affordances, originates from a seminal work that looked at what natural environments make possible in the act and process of seeing (Gibson, 1979). The agency of non-humans is hardly discussed in the cases.3 Only one case, Thorpe et al. (2021), centres the concept of “Country” and its meaning to Indigenous peoples; and explicitly discusses the agency of non-humans. This pattern invites teacher education to cast its net more widely in considering multiple funds of knowledge.

The range of immediate and anticipated outcomes of the initiatives is wide, and largely positive and optimistic. The immediate and context-based outcomes for the interventions have been highlighted in terms of the pedagogical affordances, the potential for addressing social justice concerns, and preparing teachers for stigmatised contexts. One point to note, however, is that the cases were reported on by the teacher educators involved in implementing the initiatives. Although there is significant value in educators studying and improving their own practice, the largely happy stories reported in the cases could be related to their interests in projecting a positive impression of a developing and somewhat marginalised practice, as well as their familiarity with the rationale and processes. Thus, they may have limited their critical angle regarding the affordances and nuances of COTE. Also noteworthy is that, for some of the articles, it was difficult to distinguish between the desired and realised outcomes. Only Eppley et al. (2011) explicitly articulated that their hope that rural teacher candidates were aware of the resourcefulness of their rural areas is not what they saw in their interactions with rural children and classroom reflections. However, they also attributed this to external influences (such as media and travel) and planned to repeat their approach in the future. This reflects their deep-rooted conviction and confidence in the approach.

7 Concluding reflections

The affordances reported in the reviewed articles provide some measure of confidence in ICOTE approaches, which we have conceptualised as a form of community-oriented praxis, at least in the short term. The cases reflecting such praxis indicate that answering to the aforementioned question on what teachers need to learn in order to help students achieve their potential (Grant, 2008) concerns not only enabling teacher candidates to learn for themselves and to learn how to teach, but also to act for social justice and to attend to some of the most pressing challenges facing the teaching profession, such as sustainable recruitment and retention. By experientially exposing teacher candidates to social (in)justice concerns in local communities, COTE makes it possible for teacher candidates to position themselves to address these challenges. This includes through nurturing a willingness to work in territorially marginalised schools and communities. With increasing practice in this direction, there is potential for enabling all students, irrespective of their geographical and socioeconomic conditions, to learn and develop the necessary knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

However, longitudinal studies are needed to ascertain the impact and sustainability of COTE and the diverse initiatives therein, and this presents a challenge. While some cases such as RATEP have evidently been sustained for decades and some societal impact realised (York and Henderson, 2003), only anecdotal evidence is available. Working with local community actors takes time and effort (Harfitt and Chow, 2020), and educators typically work in resource constrained environments with competing internal and external demands. Negotiating and navigating these requires more concerted attention than any one practitioner or institution may afford.

While, at face value, attention to local contexts might seem at odds with a logic where teachers are expected to meet externally set goals, the affordances identified in this study suggest that these two logics are mutually benefiting, and that attention to local conditions enables equitable participation in education. When the ground is levelled for people from different identity groups, geographical settings and socioeconomic situations to influence and participate in education, the national and international goals can be more easily reached with less disparity among participants’ achievement levels. Without attention to local conditions, the disparities are bound to remain; and it is in the interest of teaching and teacher education to address this for the benefit of society.

A way forward for addressing sustainability concerns and tensions between local conditions and standardisation agendas (or attempts) could be conceptual and systemic interventions. The conceptual interventions might entail re-considering the very definition and role of a teacher, and reimagining how teachers can be prepared to legitimately fulfil this role. McNaught and Gravett (2021) advocate that teacher education programmes be “transformational in terms of enabling teachers to see their role as not merely teaching conventional discipline content but rather as facilitating the growth of an informed citizenry who can consider the wellbeing of their communities (locally, nationally and globally) as being a natural attribute of an educated person” (p. xvi). Practically, as demonstrated in the cases, COTE points to the value of tripartite collaborations among higher education institutions, schools, and local communities. The needed systemic interventions might entail both popularising and adopting the COTE approach in a wide enough spectrum of educational contexts.

With such reconceptualisation and enactment of systemic interventions, and as the community-oriented approach gains ground across contexts, we imagine that engaging with local communities in a non-hierarchical, responsive manner will no longer be considered profession-threatening and peculiar “teaching against the grain” (Cochran-Smith, 2001, 2010), but comfortably integral to teaching and teacher education praxis. To enable this, it is important that experiences, approaches, and outcomes from COTE practices are regularly examined and widely shared among practitioners, policy makers and research communities, which is why studies such as the current one and the longitudinal ones we hope to report on in future publications might be helpful.

Author contributions

AK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper is part of the AK’s doctoral studies funded through employment by the University of Borås, Sweden.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Petra Angervall and Anders Sonesson (the AK’s other doctoral supervisors) for their comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, and Magnus Levinsson for comments on the analytical approach and a later version of the manuscript. They would also like to acknowledge the various comments from members of the Studies in Professional Education and Training for Society (SPETS)4 network, and colleagues at the Department of Educational Work, University of Borås.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^African Education Research Database: https://essa-africa.org/AERD

2. ^East African Nature and Science Organisation (ENSO) Journals: https://journals.eanso.org/

3. ^Zeichner et al.’s (2016) typology for understanding how and with what implications communities can be engaged in education processes is also overly anthropocentric, and does not account for non-human elements such as natural environments. There is therefore space for further development of the typology in future work on COTE (see Strom and Martin, 2022; Heikkinen et al., 2024 for relevant discussions).

4. ^SPETS is an academic consortium in Sweden aimed at research and doctoral training on professional education and professional development. It currently includes four universities in Sweden: Lund University, University of Borås, Chalmers University of Technology, and Malmö University. Details here: https://www.ahu.lu.se/en/research/about-spets/

References

Adams, R., and Farnsworth, M. (2020). Culturally responsive teacher education for rural and native communities. Multicult. Perspect. 22, 84–90. doi: 10.1080/15210960.2020.1741367

Alsop, S., Ames, P., Arroyo, G. C., and Dippo, D. (2010). Programa de fortalecimiento de capacidades: reflections on a case study of community-based teacher education set in rural northern Peru. Int. Rev. Educ. 56, 633–649. doi: 10.1007/s11159-010-9178-4

Alsop, S., Dippo, D., and Zandvliet, D. B. (2007). Teacher education as or for social and ecological transformation: place-based reflections on local and global participatory methods and collaborative practices. J. Educ. Teach. 33, 207–223. doi: 10.1080/02607470701259499

Alvarez, A., Farinde-Wu, A., Delale-O’Connor, L., and Murray, I. E. (2020). Aspiring teachers and urban education programs. Urban Rev. 52, 880–903. doi: 10.1007/s11256-020-00550-6

Arthur, J., and Bailey, R. (2000). Schools and community: The communitarian agenda in education. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

Arum, R. (2000). Schools and communities: ecological and institutional dimensions. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 395–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.395

Austin, J., and Hickey, A. (2011). Incorporating indigenous knowledge into the curriculum: responses of science teacher educators. Int. J. Sci. Soc. 2, 139–152. doi: 10.18848/1836-6236/CGP/v02i04/51284

Babkie, A. M., and Provost, M. C. (2004). Teachers as researchers. Interv. Sch. Clin. 39, 260–268. doi: 10.1177/10534512040390050201

Bagley, C., and Beach, D. (2015). The marginalisation of social justice as a form of knowledge in teacher education in England. Policy Fut. Educ. 13, 424–438. doi: 10.1177/1478210315571220

Baquedano-López, P., Alexander, R. A., and Hernandez, S. J. (2013). Equity issues in parental and community involvement in schools: what teacher educators need to know. Rev. Res. Educ. 37, 149–182. doi: 10.3102/0091732X12459718

Bassey, M. O. (2022). “Critical social foundations of education: advancing human rights and transformative justice education in teacher preparation” in The Palgrave handbook on critical theories of education. eds. A. A. Abdi and G. W. Misiaszek (Cham: springer International Publishing), 97–111.

Beach, D. (2018). “A Meta-ethnography of research on education justice and inclusion in Sweden with a focus on territorially stigmatised areas” in Structural injustices in Swedish education: Academic selection and educational inequalities (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 197–233.

Beach, D., and Bagley, C. (2012). The weakening role of education studies and the re-traditionalisation of Swedish teacher education. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 38, 287–303. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2012.692054

Beaudry, C. (2015). Community connections: integrating community-based field experiences to support teacher education for diversity. Educ. Consider. 43:1033. doi: 10.4148/0146-9282.1033

Bedamatta, U. (2014). The MLE teacher: an agent of change or a cog in the wheel? Austr. J. Indig. Educ. 43, 195–207. doi: 10.1017/jie.2014.25

Borrelli, I., Benevene, P., Fiorilli, C., D’Amelio, F., and Pozzi, G. (2014). Working conditions and mental health in teachers: a preliminary study. Occup. Med. 64, 530–532. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu108

Borrero, N., and Sanchez, G. (2017). Enacting culturally relevant pedagogy: asset mapping in urban classrooms. Teach. Educ. 28, 279–295. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2017.1296827